Abstract

The latent heat, L, is central to melting, but its atomic origin remains elusive. It is proportional to the entropy of fusion, ΔSfus = L/Tm (Tm is the melting temperature), which depends on changes of atom configurations, atom vibrations, and thermal electron excitations. Here, we combine inelastic neutron scattering and machine-learned molecular dynamics to separate ΔSfus into these components for Ge, Si, Bi, Sn, Pb, and Li. When the vibrational entropy of melting, ΔSvib, is zero, ΔSfus ≃ 1.2 kB per atom. This result provides a baseline for ΔSconfig and nearly coincides with “Richard’s Rule” of melting. The ΔSfus deviates from this value for most elements, however, and we show that this deviation originates with extra ΔSvib and extra ΔSconfig. These two components are correlated for positive and negative deviations from Richard’s rule – the extra ΔSconfig is consistently ~ 80% of ΔSvib. Our results, interpreted with potential energy landscape theory, imply a correlation between the change in the number of basins and the change in the inverse of their curvature for the melting of pure elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Melting is the iconic first-order phase transition where a material changes from a solid to a liquid at the melting temperature, Tm. In equilibrium, this occurs when the Gibbs free energy,

of the solid equals that of the liquid. The energy absorbed at Tm, the latent heat, is defined as L = TmΔSfus, where ΔSfus is the entropy of fusion. The definition of L corresponds to the condition ΔG = Gl − Gs = 0, and ΔSfus results from the inequality of ∂G/∂T for the solid and liquid at Tm.

Estimating Tm is central to many investigations1,2,3,4. A well-known predictor is the Lindemann criterion, which states that melting occurs when the square root of the mean-squared atom displacement reaches approximately 10% of the interatomic distance5. While it has had some success, its conceptual basis includes only the solid phase. An effort to include the thermodynamics of the liquid in this criterion led to mixed results6. More recently, advances in computational methods7,8 have allowed for increasingly accurate melting temperature predictions for various materials9,10,11.

Despite the improvements in predicting melting temperatures, work remains to codify the thermodynamics of melting. To date, a common “rule” for the entropy of fusion is the empirical Richard’s rule, which states ΔSfus ≈ 1.1 kB per atom for monatomic systems12. Elements with much larger entropies of fusion are considered to melt anomalously (see Fig. 1)13. Some efforts to explain these anomalies consider a separation of the entropy of fusion into components from changes in atomic vibrations, configurations, and electronic excitations14,15,16

Experimentally quantifying these atomic components of the entropy of fusion is a challenge. However, methods that measure the dynamic response function, such as neutron or x-ray scattering, show promise for identifying and analyzing vibrational motion in liquids17,18,19,20. For solids, using vibrational spectra for assessing the vibrational entropy is well-established for scattering techniques21,22,23. Extending these analyses to the liquid state is difficult owing to the quasielastic scattering from diffusion, which widens the intense elastic peak to cover the vibrational spectra at low energies. In fact, most neutron studies on liquid dynamics focus on diffusion.

a Entropies of fusion for elements up to uranium, plotted versus atomic number. The elements chosen for this study are indicated by a vertical line and are annotated with the value of their entropy of fusion. Circles (crosses) designate experimentally (computationally) studied elements. b Distribution of ΔSfus for the first 92 elements. The dashed lines in (a) and (b) show Richard’s rule of 1.1 kB per atom.

Here, advances in experimental and computational methods were used to quantify the thermodynamic contributions to the entropy of fusion in pure elements. Simulations used molecular dynamics with machine-learning interatomic potentials for Ge, Si, Pb, and Li. Time-of-flight (TOF) inelastic neutron scattering (INS) experiments were performed on Ge, Bi, Sn, and Pb to obtain the vibrational entropy across the melt. To our knowledge, this is the first experimental quantification of the vibrational contribution to melting. Vibrational entropy accounts for most, but not all, of the anomalous deviation from Richard’s rule.

Results and Discussion

Liquid spectra analyses

Accessing a sufficient range of momentum transfer, Q, to capture the structure and dynamics in liquids using time-of-flight (TOF) neutron scattering presents a challenge due to the balance between energy resolution and the kinematic energy cutoff in reciprocal space. An incident energy of 50 meV provided sufficient energy resolution (approximately 2 meV at the elastic peak) and allowed Q-cuts from 0.5–8 Å−1. An advantage of the TOF method is that it allows simultaneous data acquisition with high statistical quality over a wide range of Q, and the selection of Q for analysis can be done post-measurement.

After subtracting the signal from the empty sample holder, the scattering intensities were separated into diffusive and vibrational components. These intensities were symmetrized using the condition of detailed balance and normalized to the total intensity of the static structure factor, S(Q), yielding S(Qn, ε)/S(Q), where Qn is a selected value of Q and ε is the energy. The quasielastic peak for each Qn was then fit to the well-established incoherent response function,

where A is a scaling factor, Γ is the peak width, and ∗R(Q, ε) denotes a convolution with the resolution function. Within the hydrodynamic regime (where Q < Q0/2 and Q0 is the location of the first peak in S(Q)24), these fits agree with previously reported self-diffusion coefficients, D, from the relationship Γ = DQ2 25,26,27,28.

Each fit was then subtracted from the observed intensity to remove effects from diffusion (diffusive processes do not describe atomic vibrations29, and, as discussed later, diffusion does not contribute substantially to the latent heat). Due to the increasing intensity of quasielastic scattering near the structure factor maximum (typically ~ 2.5 Å−1, as seen in the liquid spectra of Fig. 2), a clear distinction between the diffusive and vibrational motion was not possible for all values of Q. Vibrational intensities were discernible below Q = 1.65 Å−1 (Ge), Q = 1.55 Å−1 (Bi, Sn, and Pb) and between Q = 3.15 − 3.55 Å−1 (Bi and Sn) and Q = 2.85 −3.25 Å−1 (Pb). The positive energy transfer sides of spectra at these values of Q were selected for further analysis.

Total S(Q, ε) in the crystalline solid (top left) and liquid (bottom left) phases after background subtraction, with selected S(Qn, ε) (right) normalized to S(Q) for (a) Ge and (b) Pb near their respective melting temperatures. The S(Q, ε) intensity bars for the solid and liquid phases of each element are the same and are on a log scale. The dashed lines under the constant Q cuts are quasielastic fits to the data that include a convolution with the Q and ε-dependent instrument resolution function. Standard errors (grey bars) are generally smaller than the symbol size.

To analyze the range of Q-cuts with distinct vibrational dynamics, a S(Qn, ε) specific density of states (DOS) algorithm was developed (see Methods). DOS curves from individual Qn for the liquid were summed and normalized to obtain a total vibrational density of states, g(ε). This workflow was repeated on the solid for the same Qn. The entropy difference between them was calculated using Sl,vib − Ss,vib where

a relationship that has been tested with success for solids with large anharmonicity at high temperatures and was used (in the classical limit) to develop the vibrational-transit theory of liquids12,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

The low Q-range, where vibrational motion is most distinguishable from diffusive motion, causes some challenges. As always, the lower-energy vibrational modes are partially covered by the resolution-broadened elastic peak, and at larger Q, there is a tail from quasielastic scattering that must be removed. The intensity of phonon scattering by an atom l moving in a phonon mode j scales with the factor \(| \overrightarrow{Q}\cdot {\overrightarrow{e}}_{j,l}{| }^{2}\), where \({\overrightarrow{e}}_{j,l}\) is the direction of atom displacement in the mode. Since this means that different modes have different scattering efficiencies37,38, the DOSs generated from the sampled Q-cuts do not fully represent the thermodynamic g(ε). Two scaling procedures (see Figs. 3 and 4) were performed on these DOSs to demonstrate that the calculated differences in vibrational entropies between the liquid and solid phases of each element are reliable for obtaining thermodynamic trends. Differences in ΔSvib between these two scalings were used as error bars in Fig. 5.

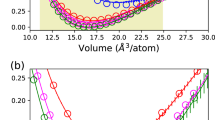

a Vibrational (light gray), and extra (dark gray) contributions to the entropies of fusion in Ge, Bi, Sn, and Pb determined from Q-weighted densities of states. Error bars were estimated from the two scalings of the neutron-weighted density of states (see details in Methods: Density of States Analysis). b Vibrational (light gray), configurational (dark gray), and electronic (black) contributions to the entropies of fusion in Ge, Si, Pb, and Li from computations. The horizontal dashed line is the total entropy of fusion, ΔSfus = 1.1 kB per atom, according to Richard’s rule.

Vibrational densities of states

The left columns of Fig. 2a, b show background-corrected inelastic neutron scattering spectra for polycrystalline and liquid Ge and Pb near their melting temperatures, Tm,Ge = 1211 K and Tm,Pb = 601 K. Intensities for each element are on the same scale so a direct comparison of features between the solid and liquid phases is possible. Selected constant-Q slices for liquid Ge and Pb are shown in the right column of Fig. 2a, b. Gray error bars show the excellent statistical quality of the data – the error bars are often smaller than the marker size. Dashed lines illustrate the resolution-convoluted quasielastic fits of Eqn. (3). Each matches well the expected Lorentzian shape and intensities26,39,40,41.

In agreement with previous studies42,43,44, Fig. 2 shows non-diffusive contributions to the scattering intensities. Similar intensities are also found for Bi and Sn (see Fig. 6). After corrections to remove intensities from quasielastic, multiple scattering (MS), and multiphonon (MP) scattering (see Methods), the vibrational spectra remain. These are used to obtain the Q-weighted densities of states (DOSs) in Fig. 7 for Pb, Sn, Bi, and Ge. Crystalline solid DOSs obtained from the same Q values are plotted for comparison.

Total S(Q, ε) in the crystalline solid (top left) and liquid (bottom left) phases and selected S(Qn, ε) (right) normalized to S(Q) for (a) Sn and (b) Bi near their respective melting temperatures. The S(Q, ε) intensity bars for the solid and liquid phases of each element are the same and are on a log scale. The dashed lines under the constant Q cuts are quasielastic fits to the data that include a convolution with the Q and ε-dependent instrument resolution function. Standard errors (grey bars) are generally smaller than the symbol size.

The upper vibrational modes in liquid Pb extend to energies higher than those of solid Pb, showing a stiffening from approximately 10 to 12 meV. This is unexpected since most materials exhibit the opposite behavior with increasing temperature. Results for Sn are more typical, showing a small softening of the vibrational spectrum upon melting. Nevertheless, the average energies of both solid and liquid DOS curves for Pb and Sn are similar. The elements Bi and Ge, which show large deviations from Richard’s rule, exhibit significant differences between their vibrational DOSs for crystalline and liquid phases. The highest vibrational peak in Bi softens from 11.4 to 8 meV. Ge shows an even greater decrease in energy between its solid and liquid states (32.8 to 17.2 meV). Computed DOSs (Fig. 8) corroborate these results.

Figure 5a shows the vibrational contributions to the entropy of fusion of Ge, Bi, Sn, and Pb from the inelastic neutron scattering measurements. The difference between the total and vibrational entropies of fusion, denoted ΔSextra, for each element is also shown. Computational results for Ge, Si, Pb, and Li are presented in Fig. 5b. For Ge and Pb, there is excellent agreement between the vibrational entropies from simulations and experiments (see Table 1). The dashed horizontal line in Fig. 5 depicts the total entropy according to Richard’s rule.

Vibrational entropy and configurational entropy

Changes in the DOSs of Fig. 7 give differences in the vibrational entropy of melting in Fig. 5a. In Ge, which has the greatest softening between solid and liquid, the vibrational entropy of melting accounts for 41% of the total entropy of fusion. Bi, with a smaller change in its DOS across melting, shows a smaller but still substantial vibrational contribution to ΔSfus. In Sn, where the DOS shows minor changes, the contribution of vibrations to the entropy of fusion is small. Interestingly, Pb, generally considered to obey Richard’s rule, exhibits a minimal but negative change in vibrational entropy upon melting (its DOS shows a slight stiffening in Fig. 7). Within error bars, these results show that the vibrational contributions to the melting of each element scale with the total entropy of fusion, as plotted in Fig. 9.

The simulations of Ge show a vibrational component nearly identical to that from measurements. These computations also confirm the small negative value for ΔSfus,vib in Pb (see Table 1). Excellent agreement between experimental and computational results for Ge and Pb encouraged additional simulations of Si and Li, which were not measured. The values of ΔSfus,vib from simulations of Ge, Pb, Li, and Si were added to the plot of Fig. 9, and are consistent with the emerging correlation between ΔSfus and ΔSfus,vib.

Simulations of the melt also gave insight into the non-vibrational entropic contributions, defined as the “extra” entropy in the experimental results of Fig. 5a. From Eqn. (2),

Results from these calculations (see Table 1) show that, as expected, transforming from an ordered crystalline solid to a disordered liquid raises the configurational entropy. For Ge and Si, this ΔSfus,config exceeds the full ΔSfus from Richard’s rule. In contrast, our computations showed that the electronic entropy of fusion is nearly negligible for the elements calculated (see Fig. 10).

Richard’s rule and anomalous melting

Figure 1 shows numerous deviations from Richard’s rule, with values of ΔSfus that span an order of magnitude. A step beyond Richard’s rule has been to classify melting as normal or anomalous based on whether materials follow or deviate from ΔSfus = 1.1 kB per atom. However, Fig. 1b shows that this binary classification lacks nuance.

Figure 9 shows a trend for all our results. The best fit line shows that ΔSfus,vib is zero for ΔSfus ≈ 1.2 kB per atom, which is close to the value used for Richard’s rule. If Richard’s rule were representative of all elements, ΔSfus − 1.2 ≈ 0 (all units in kB per atom), deviations can be represented as

where δ denotes the “extra” entropy. The linear relationship of Fig. 9 is

Equating Eqns. (6) and (7), the extra configurational entropy is proportional to the extra vibrational entropy

This proportionality of δSconfig and δSvib indicates that structural changes, which increase the number of accessible configurations also decrease the vibrational frequencies. The balance between configurational and vibrational entropies may affect the atomic structures of liquid alloys, surfaces, and interfaces45.

Features of the potential energy landscape

Potential energy landscape (PEL) theory offers a convenient statistical thermodynamics framework to assess the relationship between the configurational, vibrational, and electronic components of entropy across the melt46,47,48. The PEL for a liquid has a large number, Ωl,b of basins, or local minima. (Vibration-transit (V-T) theory associates these basins with intersecting valleys in the PEL31,32). Atoms in the liquid make transitions between these basins, allowing the liquid to explore many configurations. During the time spent in a basin, the N atoms undergo thermal vibrations. (There is evidence that these vibrations are approximately harmonic32, but this is not needed in the present discussion). These vibrational dynamics explore a volume in the phase space of momentum, \(\vec{p}\), and position, \(\vec{q}\), where the vector notation indicates that there are 3N independent coordinates of each. The number of vibrational states, \({\Omega }_{{{\rm{l}}},\vec{p}}\,{\Omega }_{{{\rm{l}}},\vec{q}}\), available to the liquid is proportional to this 6N-dimensional volume. Metallic liquids also have a number Ωl,el of states accessible to thermally-excited electrons. Using these components, the total number of states available to the liquid, Ωl, is

Thermally accessible states for the crystal are enumerated similarly, with the essential difference being Ωs,b = 1 because there is only one equilibrium structure for atoms in the crystal. The total number of states accessible to the crystalline solid at Tm is then

The kinetic energy of the atoms in both phases is the thermal energy, 3N kBT/2.

Using this formalism and the Boltzmann entropy, \(S={k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\ln \Omega\), the relationship between these microstates and the entropy of fusion can be developed as \(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{fus}}}}={S}_{{{\rm{l}}}}({T}_{{{\rm{m}}}})-{S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}({T}_{{{\rm{m}}}})={k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\ln ({\Omega }_{{{\rm{l}}}}/{\Omega }_{{{\rm{s}}}})\). The ratio becomes

where the degrees of freedom associated with momentum cancel because the atom masses are the same in both the solid and liquid, so the ranges explored in momentum space are equal.

The complete set of vibrational modes accounts for the simultaneous vibrations of all N atoms, whether considered from a local or non-local perspective. A linear transformation from atom coordinates, \(\vec{q}\), to normal modes of vibration preserves the number of 3N independent modes. A normal mode j with lower frequency ωj has a larger vibration amplitude for a fixed energy. When atoms execute thermal vibrations as harmonic oscillators, at high temperatures the range explored in \(\vec{q}\)-space is proportional to \({\prod }_{j}^{3N}(1/{\omega }_{j})\)12, so

Then,

where the entropy from the number of basins in the liquid is relabeled as a configurational entropy, \({S}_{{{\rm{l}}},{{\rm{config}}}}/{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}=\ln {\Omega }_{{{\rm{l}}},{{\rm{b}}}}\) (again, configurational entropy is unimportant for a crystal of a pure element). This is possible because diffusional processes move the liquid structure between basins in the PEL, allowing the equilibrium value of Sl,config to be obtained from Ωl,b. However, in an ensemble average, the time spent transitioning between basins is expected to be minimal, so the transit makes little contribution to time or ensemble averages of thermodynamic quantities. There is a long history of work to extract an Sl,config from the pair distribution function (PDF) of a liquid31, but the PDF is a one-dimensional quantity that cannot fully account for three-dimensional structures.

For the vibrational entropy component, Eqn. (4) was used instead of its classical limit (the product function \(\mathop{\prod }_{j}^{3N}1/{\omega }_{j}\) in Eq. (13)). Our analysis of inelastic neutron scattering data was designed to evaluate changes in vibrational entropy across melting from vibrational mode energies above approximately ℏω = 3 meV. This accounts for most of the vibrational modes in the material, but there could be errors from vibrational modes at lower energy (a concern regarding the differences in scattering efficiencies was mentioned in the Liquid Spectra Analyses section). Our computational work obtained ΔSfus,config as

The ΔSfus,config for melting is always positive, as expected because Ωl,b ≫ Ωs,b ≃ 1. There is some variation in the magnitude of ΔSfus,config – approximately a factor of two for the elements studied here. Nevertheless, the change in vibrational entropy can be comparably large or even negative. (The negative values of ΔSfus,vib are bounded because ΔSfus must be positive.) Following suggestions that elements with large ΔSfus (e.g., Si and Ge) undergo large changes in local structure upon melting13, we might expect a correlation between ΔSfus and the change in coordination number Δz of Table 2. However, this correlation is not very compelling since the chemical potential also depends on bond distances and angles.

Since a larger vibrational entropy corresponds to lower frequencies from potential wells with lower curvatures, Eqn. (8) makes an unexpected statement about the PEL. Upon melting, the number of basins accessible to the liquid, Ωl,b, is inversely proportional to the change in curvature of the basins (with respect to the solid). Further work to corroborate this trend would be appropriate.

Conclusions

Methods of inelastic neutron scattering (INS) were developed for measuring vibrational spectra of materials across melting transitions. Quasielastic scattering from diffusional processes confined the data analysis to lower values of momentum transfer or those slightly above the maximum intensity of the static structure factor. Accounting for quasielastic scattering, multiple scattering, and multiphonon scattering allowed for the isolation of the vibrational spectra above 3 meV. Approximate vibrational density of states curves were obtained for both the liquid and the solid phases of Ge, Bi, Sn, and Pb using the same procedures, giving the change in vibrational entropy across melting.

The computational methods to model melting required large numbers of atoms and employed classical molecular dynamics with machine-learned interatomic potentials. These potentials were trained with ab initio molecular dynamics calculations on smaller systems. Computational results gave changes in vibrational entropies upon melting that were in excellent agreement with the INS results for Ge and Pb. These simulations also reproduced the total latent heat with good accuracy.

There is an emerging correlation between the latent heat of melting and the difference in vibrational entropies of the solid and liquid phases. To a good approximation, Richard’s rule corresponds to melting with zero change in vibrational entropy, which occurs when ΔSfus ≈ 1.2 kB per atom. Deviations from Richard’s rule are proportional to the change in vibrational entropy upon melting. However, these deviations also include an extra ΔSconfig equal to 80% of ΔSvib. A positive departure from Richard’s rule indicates that the liquid PEL surface has more basins, but these basins have smaller curvatures than basins in the crystal.

Methods

Inelastic neutron scattering

Inelastic neutron scattering experiments were performed on high-purity polycrystalline granules of Ge (99.999%), Bi (99.997%), Sn (99.99%), and Pb (99.99%) encapsulated in vacuum-sealed quartz tubes. Depending on the neutron cross-section of each element, the inner diameter of the quartz tubes varied from 3 to 4 mm. Ampules of each material were arranged in parallel and enclosed in a vanadium sachet to provide optimal flux on a large, relatively flat volume. The high-temperature furnace MICAS was used to heat the samples to approximately 200 K above their melting temperatures, allowing data collection in the solid and liquid phases49. Spectra from empty ampules in a vanadium sachet were also collected for background subtraction at the temperatures of interest.

All measurements were taken on the time-of-flight direct geometry wide-angular range chopper spectrometer (ARCS) at the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory50. Instrument parameters for each dataset are reported in Table 3. At the SNS, the number of neutrons emitted from the moderator of beamline 18 (ARCS) is directly proportional to the number of protons incident on the target. Therefore, to accommodate variations in accelerator power, spectra were acquired by counting to a chosen number of protons incident on the target, i.e., a specific proton charge in Coulombs. Two Coulombs of proton charge were used to obtain the excellent statistical quality in the data reported here. Single phonon scattering and vibrational densities of states (DOS) for the crystalline solids were obtained using the Mantid and multiphonon packages, and multiple scattering corrections were calculated with MCViNE51,52,53. These details and intermediate states of analysis are described below.

Multiple scattering corrections

The concern about multiple scattering (MS) arises because inelastic scattering from phonons increases rapidly with Q. This means that it is possible for an initial scattering at a high angle to be followed by a second scattering back to a low angle. Therefore, a spectrum acquired at low angles, or low Q, could be contaminated by double-scattering events with large energy transfers.

The MCViNE (Monte-Carlo VIrtual Neutron Experiment) software is a neutron ray-tracing simulation package that tracks the paths of neutrons through the interaction with instrument optical components, scattering from the sample, interception by the detectors, and reduction to an experimentally equivalent format53. MCViNE was used to simulate MS effects from polycrystalline lead measured on the wide Angular-Range Chopper Spectrometer (ARCS) near its melting temperature. Lead was chosen because its single (and therefore its multiple) scattering cross section was the largest of the elements studied.

The MCViNE simulation was initialized with a beam with 109 neutron packets emitted by the moderator. These neutrons passed through the simulated instrument with the chopper settings of the actual measurements. Packets that reached 15 cm upstream from the sample position were saved and reused in later simulations of neutron scattering from the sample. All samples were modeled with dimensions and orientations matching the respective experimental setup. The incoherent approximation using the total neutron cross-section was assumed, allowing for a polycrystalline average without explicit knowledge of the vibrational dispersions. The resulting event-mode NeXus files were reduced using the same reduction tools as the experimental data51.

These simulations allow contributions from multiple scattering to be turned on or off, making it straightforward to identify the intensity from MS in the dynamic scattering function, S(Q, ε). For each Q-cut of interest, results showed that MS is non-negligible but predominately affects elastic scattering, which is benign. Additional MS effects on the inelastic spectra resemble those of multiphonon spectra in the incoherent approximation, and can be practically removed by using an iterative approach22,54 (more details in Section “Density of States Analysis”). Alternatively, the broad nature of these MS spectral contributions allows them to be treated as part of a constant background that can be subtracted from each Q-cut before further corrections for multiphonon scattering. Differences between the latter approach and a full MS calculation with MCViNE were small, and a comparison is shown in Fig. 11. For polycrystalline solids, the excellent agreement between the densities of states (DOS) from Q-cuts and previous experimental DOS55,56,57 supports this choice of MS subtraction in the solid. Similarly, the excellent agreement between the experimental and computational results in the liquid phase shows that this correction method works well for liquid scattering. The Lorentzian form of the quasielastic scattering at low Q also followed expectations from the diffusion constants, as described next.

Quasielastic fitting

An incident energy of 50 meV provides scattering from Q = 0.5 − 8 Å−1 with a resolution of 0.1 Å−1. After data reduction and subtraction of the signal from the sample holder, candidates for where quasielastic and inelastic scattering might be distinct were identified by finding regions of reciprocal space with intensity away from ε = 0 meV. These were below Q = 1.65 Å−1 (Ge) or Q = 1.55 Å−1 (Bi, Sn, and Pb) and between Q = 3.15 − 3.55 Å−1 (Bi and Sn) or Q = 2.85 − 3.25 Å−1 (Pb). For these values of Q, quasielastic scattering takes the shape of a Lorentzian, and the spectra can be fit to the incoherent response function,

where A is a scaling factor, Γ describes the peak width, and ∗R(Q, ε) denotes convolution with the resolution function. All spectra fit to this expression were normalized to the static structure factor, S(Q) and corrected for detailed balance,

The objective of fitting quasielastic neutron scattering (QENS) peaks was to subtract them from each Qn spectrum and extract the vibrational spectra (where n indicates the selected value of Q). Since vibrational dynamics have some contributions to the intensity under the quasielastic peak, using the hydrodynamic limit (where Q < Q0/2 and Q0 corresponds to the location of the first intensity peak in S(Q)) and known diffusion coefficients to build the initial fitting model using Γ = DQ2 was essential. First, a spectral cut at Q ≈ 0.5 Å−1 for each element was normalized to S(Q) and symmetrized with detailed balance (see Eqn. (16)). Then, using Q = 0.5 Å−1 and previously reported liquid diffusion coefficients, D, near the melting temperature25,26,27,28, Γ was calculated. From Γ, Eqn. (15) was evaluated for varying intensity offsets. This offset served as a first-order approximation to capture only quasielastic contributions. The value that gave the smallest root mean squared error fit to the data was chosen as the starting offset for higher Q spectra. Aside from this starting model, all spectra were fit to Eqn. (15) with Γ and A as free parameters. The diffusion coefficients from higher Q-cuts (but still below Q0/2) were consistent with diffusion coefficients previously reported (see Table 4). These results lend confidence to the fits performed outside the hydrodynamic limit. Fitting with this procedure (i.e., only looking at the central peak) avoided any assumptions regarding the spectrum from vibrational dynamics away from ε ≈ 0 meV. The resulting quasielastic fits from each Q of interest were subtracted from the inelastic neutron spectra and further analyzed using the density of states algorithm described below.

Density of States Analysis

To obtain vibrational spectra from the different Q-cuts, a S(Qn, ε) specific density of states (DOS) algorithm was developed. Owing to poor instrument resolution on the negative energy transfer side of the elastic line, this side of the spectrum was discarded. For each Qn, a multiple scattering correction was performed, informed by Monte Carlo ray tracing (see above). Then, an initial guess of the vibrational density of states with a chosen energy maximum was input to calculate multiphonon contributions for the specific temperature, T, and Qn. Using the calculated scattering (including multiphonon), the experimental intensity was scaled to match the computed. The simulated multiphonon contribution was subtracted from the experimental S(Qn, ε), and the remaining (single scattering) was used to generate an experimental density of states from

where A1 is the vibrational spectrum from single scattering and

is calculated from the previous DOS iteration. This process is continued until the difference between the previous and current iterations of the DOS is minimal, as outlined by Sears et al. and others22,54. Varying the energy range of the initial DOS by ± 1 meV showed little change in the final DOS. Once converged, the Q-cut DOSs were summed together and renormalized. This workflow was repeated for the solid phase using the same Q-cuts.

As outlined in the main text, a concern of this process is the limited Q-range where vibrational and diffusive motion are separable. Since coherent scattering dominates the measurements in this study, this limitation in Q means the DOSs generated from the sampled Q-cuts may not fully represent the true g(ε) needed for thermodynamics. Two scalings were performed to demonstrate that although the Q-cut derived DOSs may not fully describe vibrational thermodynamics, the difference in entropy of the liquid and solid is reliable.

Both scaling methods begin with the thermodynamic polycrystalline DOS calculated using the well-established neutron multiphonon package58. The solid Q-cut weighted DOS is then calculated using the same {Qn} used for the liquid. Here the transverse modes in the solid and liquid may make a weaker contribution than the longitudinal modes in the Q-weighted g(ε) because of the tendency for \(\overrightarrow{Q}\) to be misaligned along the directions \(\overrightarrow{e}\) of atom displacements in transverse vibrational modes37,38. However, the true g(ε) of the crystal is known and was checked with our experimental spectra over a wide range of Q. A multiplicative factor for each element was calculated to bring the Q-weighted DOS into agreement with the thermodynamic DOS.

The first scaling algorithm applies this multiplicative factor to the solid and liquid Q-weighted DOS up to the energy of the first transverse peak. After renormalization, the lower region of the liquid DOS is in better agreement with the computational (thermodynamic) vibrational g(ε), as seen in Fig. 3. For the scaling in the second algorithm, the multiplicative factor is applied to the entire energy range of the solid and liquid DOS from {Qn}. The resulting (renormalized) liquid DOSs for each element are shown in Fig. 4. After each scaling, the sound velocity of the solid and liquid was used to confirm that the behavior of the low-energy regime (less than 2 meV) was correct59. In bismuth, the low energy scaled g(ε) required an additional correction (the step in the liquid DOS of Fig. 3).

Entropy differences between solid and liquid were calculated using the DOSs from each of these scaling methods and compared to the ΔSfus,vibe from the non-scaled DOSs. Minor variations between these values were used to generate error bars for the reported vibrational entropy of fusion. The general agreement of the final change in entropy is consistent with vibrational thermodynamics.

Thermodynamic integration with MTP

To reproduce dynamics across the melting transition, machine-learned moment tensor potentials (MTP)60 for Ge, Si, Pb, and Li were trained on DFT data following61. For each element, the MTP potentials were actively trained on the fly by running MD simulations for a grid of volumes and temperatures near melting conditions. The interatomic potentials from this procedure were used to calculate the total change in entropy between the solid and liquid phases of each element with Bayesian learning thermodynamic integration62. The vibrational entropy contribution of each phase was calculated from the vibrational density of states (PDOS) obtained from velocity autocorrelation function analyses63. The quasielastic peak was subtracted from the total PDOS for the liquid phase. Additional details on MLIP construction and computational data analyses are given below.

Moment tensor potential training

Large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed with the use of Moment Tensor Potentials (MTPs)60,64 as implemented in the MLIP software package61. A total of four MTPs were fit to quantum mechanical data.

Moment tensor potentials for each element were trained to reproduce both the solid and liquid phases and their lattice dynamics near and across the melt. Training for each followed the procedure described in61 for calculating the melting point. In the pretraining stage, a level-16 MTP with a cutoff radius of 5 Å, and a mindist parameter of 1.4 Å was trained with 20 configurations sampled from ab initio molecular dynamics. Next, on-the-fly training was performed using classical molecular dynamics for the solid and liquid phases near the melting point. The temperature and lattice constant grids for the active selection runs for each material are shown in Table 5. Configurations selected from this training were processed with low-fidelity DFT to reduce computational cost. The final training set, generated from a subset of these configurations, was run with high-accuracy DFT calculations using VASP65,66,67. Another round of active learning was also performed in this step.

A summary of the fitting procedure parameters is shown in Table 6, where Nconf is the number of configurations in the training set and ΔE is the mean potential energy difference per atom between the MTP and the ab initio model. Frel and Srel are the relative energy and stress difference per atom and are computed using

where ΔA is the difference in force or stress between the ab initio model and the moment tensor potential, and \(\overline{\Delta A}\) is its mean value.

Thermodynamic Integration using Bayesian learning

Thermodynamic data was generated from molecular dynamics calculations using LAMMPS68 with Moment Tensor Potentials (see section above for how to generate these). Simulations of 4800 ps were run on a grid of volumes and temperatures near the melting point for each element in their solid and liquid phase. The average of the pressure and potential energy of each grid point was taken over 480 values (one value per 10 ps of the calculation) to ensure the statistical independence of the samples. Each simulation was performed with a randomly chosen number of atoms to include information about the finite size dependence of the computed thermodynamic data. The melting point for each element was predicted from a coexistence calculation following the procedure in69 for uncertainty estimation. The confidence interval for the computational values of the melting point presented in the main text is less than 2 K for all elements.

A Bayesian learning Thermodynamic Integration workflow62 was constructed using the thermodynamic data from MD. This method allowed the calculation of the temperature and volume-dependent free energy while avoiding errors from finite system size. In particular, the pressure and potential energies were reformulated as free energy derivatives, and the melting point served as an “anchor” for the free energy difference between solid and liquid phases. The anchor guaranteed the uniqueness of the system since, without it, any constant shift of the free energy curve would be a solution. Data generated from this step were fed into a Gaussian Process regression with a physically informed kernel function. This process provided a flexible, nonparametric, analytical, functional form, which allowed a reconstruction of the free energy and its derivatives with an estimation of the confidence interval. The resulting statistical error of the computed entropy differences was less than 0.1 %.

Autocorrelation function analyses

As is shown in63,70 an accurate method for calculating the vibrational density of states, g(ε), is taking the Fourier transform of the velocity autocorrelation function Φ(t).

In theory, autocorrelation methods include anharmonic effects up to infinite order. However, a convergence of the autocorrelation function is only reached at long time scales, and a large supercell is required to resolve a sufficient number of points in the Brillouin zone. Thus, due to computational cost, ab initio molecular dynamics can only be used for very approximate calculations71. On the other hand, classical force fields scale well with time and supercell size but may provide dynamics that are less quantitative72. We use machine learning interatomic potentials trained on ab initio data to perform large-scale simulations, preserving the quantum-mechanical level of accuracy with reasonable computational time.

The Moment Tensor Potentials obtained with the procedure described in the previous section were used to perform large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with the LAMMPS code68. The supercell size was 20 × 20 × 20 of the conventional unit cell of the corresponding solid phase. The calculations were performed in two subsequent steps. In the first step, the system was equilibrated near melting. For the solid phase, this corresponded to a molecular dynamics run at zero pressure at the melting temperature for 40 ps. The procedure for liquids included an additional pre-equilibrium melting stage in which the system was kept at a high temperature (four times the melting temperature) for 40 ps. In the second step, the equilibrated phases were run in the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble for 10 ps. The autocorrelation function was then computed using outputs from this step.

The Fourier transform of the autocorrelation function was used to obtain the anharmonic vibrational density of states. For the liquid phase, the contributions from diffusive processes were removed by subtracting a Lorentzian fit (similar to Eqn. (15)) from the density of states. The computational densities of states for different elements are shown in Fig. 8. Finally, the vibrational contribution to the entropy was calculated from both phases using Eqn. (4).

Data availability

Experimental data to reproduce the figures in this study can be found at73.

Code availability

Codes to process the experimental and computational results herein are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Morris, J. R., Wang, C. Z., Ho, K. M. & Chan, C. T. Melting line of aluminum from simulations of coexisting phases. Phys. Rev. B 49, 3109–3115 (1994).

Karthikeyan, M., Glen, R. C. & Bender, A. General Melting Point Prediction Based on a Diverse Compound Data Set and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 45, 581–590 (2005).

Hong, Q.-J. & van de Walle, A. Solid-liquid coexistence in small systems: A statistical method to calculate melting temperatures. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 094114 (2013).

Hong, Q.-J., Ushakov, S. V., van de Walle, A. & Navrotsky, A. Melting temperature prediction using a graph neural network model: From ancient minerals to new materials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2209630119 (2022).

Lindemann, F. Über die berechnung molekularer eigenfrequenzen. Phys. Z. 11, 609–612 (1910).

Wallace, D. C. Melting of elements. Proc. R. soc. Lond. Ser. A 433, 631–661 (1997).

Ding, J. et al. Universal nature of the saddle states of structural excitations in metallic glasses. Mater. Today Phys. 17, 100359 (2021).

An, Q., Johnson, W. L., Samwer, K., Corona, S. L. & Goddard, W. A. The first order L-G phase transition in liquid Ag and Ag-Cu alloys is driven by deviatoric strain. Scr. Mater. 194, 113695 (2021).

Guan, P.-W. & Viswanathan, V. MeltNet: Predicting alloy melting temperature by machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.14048 http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.14048 (2020).

Bejagam, K. K., Lalonde, J., Iverson, C. N., Marrone, B. L. & Pilania, G. Machine Learning for Melting Temperature Predictions and Design in Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Biopolymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 126, 934–945 (2022).

Jung, J. H., Srinivasan, P., Forslund, A. & Grabowski, B. High-accuracy thermodynamic properties to the melting point from ab initio calculations aided by machine-learning potentials. Npj Comput. Mater. 9, 3 (2023).

Fultz, B. Phase Transitions in Materials (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2020), 2nd edn.

Grimvall, G. On anomalous entropies of fusion. Liquid Metals 1976 90–94 (1977).

Wallace, D. C. Statistical mechanical theory of liquid entropy. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 52, 425–435 (1994).

Schulze, R. K., Wallace, D. C. & Lashley, J. C. Density of states features in some anomalous melting elements. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 465107 (2013).

Das, C. K. Anomaly in the Behavior of Silicon from Free Energy Analysis: A Computational Study. In Suma, V., Fernando, X., Du, K.-L. & Wang, H. (eds.) Evolutionary Computing and Mobile Sustainable Networks, Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, 575–592 (Singapore, 2022).

Sears, V. Slow-neutron multiple scattering. Advances in Physics 24, 1–45 (1975).

Brockhouse, B. N. Lattice Vibrations in Silicon and Germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2, 256–258 (1959).

Sinha, S. K. Theory of inelastic x-ray scattering from condensed matter. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13, 7511 (2001).

Linker, T. M. et al. Neutron scattering and neural-network quantum molecular dynamics investigation of the vibrations of ammonia along the solid-to-liquid transition. Nat. Commun. 15, 3911 (2024).

Bogdanoff, P. D., Fultz, B., Robertson, J. L. & Crow, L. Temperature dependence of the phonon entropy of vanadium. Phys. Rev. B 65, 014303 (2001).

Kresch, M., Delaire, O., Stevens, R., Lin, J. Y. Y. & Fultz, B. Neutron scattering measurements of phonons in nickel at elevated temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 75, 104301 (2007).

Smith, H. L. et al. Separating the configurational and vibrational entropy contributions in metallic glasses. Nat. Phys. 13, 900–905 (2017).

Boothroyd, A. Principles of neutron scattering from condensed matter (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020).

Chathoth, S. M., Damaschke, B., Unruh, T. & Samwer, K. Influence of structural changes on diffusion in liquid germanium. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 221906 (2009).

Meyer, A. The measurement of self-diffusion coefficients in liquid metals with quasielastic neutron scattering. EPJ Web Conf. 83, 01002 (2015).

Balucani, U. & Zoppi, M. Dynamics of the liquid state (Clarendon Press, 1994).

Brockhouse, B. N. & Pope, N. K. Time-Dependent Pair Correlations in Liquid Lead. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 259–262 (1959).

Hansen, J.-P. & McDonald, I. R. Theory of simple liquids: with applications of soft matter (Elsevier/AP, Amstersdam, 2013), 4th edn.

Wallace, D. Thermodynamics of Crystals. Dover Books on Physics (Dover Publications, 1998).

Wallace, D. Statistical Physics of Crystals and Liquids (World Scientific, 2002).

Wallace, D. C., Rudin, S., De Lorenzi-Venneri, G. & Sjostrom, T. Vibrational theory for monatomic liquids. Phys. Rev. B 99, 104204 (2019).

Palumbo, M. et al. Thermodynamic modelling of crystalline unary phases. Phys. Status Solidi B 251, 14–32 (2014).

Shen, Y., Li, C. W., Tang, X., Smith, H. L. & Fultz, B. Phonon anharmonicity and components of the entropy in palladium and platinum. Phys. Rev. B 93, 214303 (2016).

Kim, D. S. et al. Phonon anharmonicity in silicon from 100 to 1500 K. Phys. Rev. B 91, 014307 (2015).

Bernal-Choban, C. M. et al. Nonharmonic contributions to the high-temperature phonon thermodynamics of Cr. Phys. Rev. B 107, 054312 (2023).

De Wette, F. W. & Rahman, A. Inelastic Scattering of Neutrons by Polycrystals. Phys. Rev. 176, 784–790 (1968).

Manley, M., McQueeney, R., Robertson, J., Fultz, B. & Neumann, D. Phonon densities of states of gamma-cerium and delta-cerium measured by time-of-flight inelastic neutron scattering. Philos. Mag. Lett. 80, 591–596 (2000).

Schneider, T., Brout, R., Thomas, H. & Feder, J. Dynamics of the Liquid-Solid Transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 25, 1423–1426 (1970).

Bosio, L., Schedler, E. & Windsor, C. Quasi-elastic neutron scattering from liquid gallium over the temperature range 163 to 333 K. J. Phys. 37, 747–753 (1976).

Springer, T. Quasielastic neutron scattering for the investigation of diffuse motions in solids and liquids. No. 64 in Springer tracts in modern physics (Springer, Berlin, 1992).

Copley, J. R. D. & Lovesey, S. W. The dynamic properties of monatomic liquids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 38, 461–563 (1975).

Soderstrom, O., Copley, J. R. D., Suck, J.-B. & Dorner, B. Collective excitations in liquid lead. J. Phys. F: Met. Phys. 10, L151 (1980).

Hugouvieux, V. A complete simulation of neutron scattering experiments: From model systems to liquid germanium. Theses, Université Montpellier II - Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc (2004).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Daeneke, T. & Tang, J. The atomic intelligence of liquid metals. Science 385, 372–373 (2024).

Stillinger, F. H. & Weber, T. A. Hidden structure in liquids. Phys. Rev. A 25, 978–989 (1982).

Stillinger, F. H. A Topographic View of Supercooled Liquids and Glass Formation. Science 267, 1935–1939 (1995).

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Niedziela, J. L. et al. Design and operating characteristic of a vacuum furnace for time-of-flight inelastic neutron scattering measurements. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 105116 (2017).

Abernathy, D. L. et al. Design and operation of the wide angular-range chopper spectrometer ARCS at the Spallation Neutron Source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 015114 (2012).

Arnold, O. et al. Mantid—Data analysis and visualization package for neutron scattering and μ SR experiments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res. A 764, 156–166 (2014).

Akeroyd, F. et al. Mantid: Manipulation and Analysis Toolkit for Instrument Data. 10.5286/SOFTWARE/MANTID https://doi.org/10.5286/SOFTWARE/MANTID (2013).

Lin, J. Y. Y. et al. MCViNE - An object oriented Monte Carlo neutron ray tracing simulation package. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res. A 810, 86 – 99 (2016).

Sears, V. F., Svensson, E. C. & Powell, B. M. Phonon density of states in vanadium. Can. J. Phys. 73, 726–734 (1995).

Cowley, E. R. A Born-von Karman model for lead. Solid State Commun. 14, 587–589 (1974).

Zdetsis, A. D. & Wang, C. S. Lattice dynamics of Ge and Si using the Born-von Karman model. Phys. Rev. B 19, 2999–3003 (1979).

Barla, A. et al. Direct determination of the phonon density of states in β − Sn. Phys. Rev. B 61, R14881–R14884 (2000).

Lin, J. Y. Y., Islam, F. & Kresch, M. Multiphonon: Phonon density of states tools for inelastic neutron scattering powder data. JOSS 3, 440 (2018).

Hu, M. Y. et al. Measuring velocity of sound with nuclear resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 67, 094304 (2002).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: A class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. MMS 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Novikov, I. S., Gubaev, K., Podryabinkin, E. V. & Shapeev, A. V. The MLIP package: moment tensor potentials with MPI and active learning. MLST 2, 025002 (2020).

Ladygin, V., Beniya, I., Makarov, E. & Shapeev, A. Bayesian learning of thermodynamic integration and numerical convergence for accurate phase diagrams. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104102 (2021).

Dickey, J. & Paskin, A. Computer simulation of the lattice dynamics of solids. Phys. Rev. 188, 1407 (1969).

Gubaev, K., Podryabinkin, E. V., Hart, G. L. & Shapeev, A. V. Accelerating high-throughput searches for new alloys with active learning of interatomic potentials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 156, 148–156 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comp. Phys. Comm. 271, 108171 (2022).

Klimanova, O., Miryashkin, T. & Shapeev, A. Accurate melting point prediction through autonomous physics-informed learning. Phys. Rev. B. 108, 184103 (2023).

Korotaev, P., Belov, M. & Yanilkin, A. Reproducibility of vibrational free energy by different methods. Comput. Mater. Sci. 150, 47–53 (2018).

Minakov, D., Levashov, P. & Fokin, V. Vibrational spectrum and entropy in simulation of melting. Comput. Mater. Sci. 127, 42–47 (2017).

Novoselov, I., Yanilkin, A., Shapeev, A. & Podryabinkin, E. Moment tensor potentials as a promising tool to study diffusion processes. Comput. Mater. Sci. 164, 46–56 (2019).

Bernal-Choban, C. Dataset for “components of entropy in the latent heat of melting” https://doi.org/10.22002/qdyyx-q6063 (2024).

Glazov, V. M. & Shchelikov, O. D. Volume changes during melting and heating of silicon and germanium melts. High Temp. 38, 405–412 (2000).

Isherwood, S. P., Orton, B. R. & Mǎnǎilǎ, R. Structure of liquid germanium. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 8–10, 691–695 (1972).

Krishnan, S. & Price, D. L. X-ray diffraction from levitated liquids. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, R145 (2000).

Cahill, J. A. & Kirshenbaum, A. D. The density of liquid bismuth from its melting point to its normal boiling point and an estimate of its critical constants. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 25, 501–506 (1963).

Waseda, Y. The structure of non-crystalline materials : liquids and amorphous solids (McGraw-Hill International Book Co. New York, 1980).

Xu, L. et al. Folded network and structural transition in molten tin. Nat. Commun. 13, 126 (2022).

Been, S. A., Edwards, H. S., Teeter Jr., C. E. & Calkins, V. P. The densities of liquids at elevated temperatures. I. the densities of lead, bismuth, lead-bismuth eutectic, and lithium in the range melting point to 1000∘C (1832∘F). NEPA Report 1585 https://www.osti.gov/biblio/12732258 (1950).

Waseda, Y. & Suzuki, K. Structure factor and atomic distribution in liquid metals by X-ray diffraction. Phys. Status Solidi B 49, 339–347 (1972).

Salmon, P. S. et al. Structure of liquid lithium. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, 195 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S. Mudide for assisting in sample preparation, R. Mills for their input on sample containment, and H. L. Smith for conversations on quasielastic fitting. Research at Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) was sponsored by the Scientific User Facilities Division, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Department of Energy (DOE). This work used resources from the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science, BES, under Contract DE-FG02-03ER46055.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M.B.-C. and B.F. designed research and conceptualized the hypothesis; C.M.B.-C., V.L., C.N.S, S.L., G.E.G., D.L.A., and performed experiments; V.L. performed MLIP computations; G.E.G. and J.YY.L. ran multiple scattering simulations; C.M.B.-C. and V.L. analyzed data and C.M.B-C. and B.F. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jack Evans and Jet-Sing Lee. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernal-Choban, C.M., Ladygin, V., Granroth, G.E. et al. Atomistic origin of the entropy of melting from inelastic neutron scattering and machine learned molecular dynamics. Commun Mater 5, 271 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00695-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00695-x