Abstract

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful method for probing electronic and vibrational properties of materials, particularly nanomaterials such as single-wall carbon nanotubes. Typically, Raman spectroscopy is conducted at a single, or few, excitation wavelengths, but that provides limited information about excitation resonance structure, and their dynamical evolution. Here, we extend a sensitive full-spectrum technique to rapidly obtain two-dimensional Raman excitation maps both statically and dynamically for chirality-pure single-wall carbon nanotube films. We demonstrate sensitive evaluation of structured resonance profiles even from weak vibrational modes, and sub-second time resolution of the dynamics of photo-driven defect production. Findings include the direct observation of bands and their profiles – including bands which could be missed in conventional Raman spectroscopy - and demonstration of differences for odd vs. even defect band combinations. This opens up possibilities to investigate the coupling of electronic states with vibrational modes in nanomaterials and track their dynamical evolution subject to intentional modulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are a foundational material system for nanotechnology. In general, sp2 carbons are ideal for Raman scattering (RS) spectroscopy; due to quantum confinement, SWCNTs have electronic/excitonic resonances which are structure-dependent and occur in the visible (vis) and near-infrared (NIR)1,2. A cornerstone of SWCNT science is the Kataura plot2,3: the optical resonance versus the RS mode frequency of the Radial Breathing Mode (RBM). The RBM is resonant, and so lights up for laser wavelengths close to an excitonic optical transition, enabling structure identification and quantification3. The also prominent G band (≈1590 cm−1) has a greater resonance energy width (≈200 meV) and is practically useful for metallicity determination2,4,5. More broadly, any molecule has many vibrational bands, with every mode having its own different resonance structure. So rather than think of one RS mode in isolation for a given molecule we can consider them all together. The map of all the RS modes and their excitation wavelength dependence is a Raman Excitation Map (REM).

Obtaining an REM experimentally is becoming much more practical. We have developed a method to get broadband Raman excitation maps quickly which we call full spectrum REM (FS-REM)6,7. As will be shown below, this method has sufficient time resolution to track REMs at a rate faster than photodegradation thus enabling pristine material characterization and the tracking of evolution over time. We emphasize that while fixed wavelength RS is an established tool for SWCNTs, even for in situ dynamics8,9 there is potentially much more information in a broadband REM, but dynamic REMs in the past were challenging to obtain practically.

By definition, SWCNTs consist of a single cylindrical wall of carbon atoms in a hexagonal lattice. Ensembles of as-produced SWCNTs are comprised of a mixture of many species, often termed chiralities. Different chiralities are specified using (n,m) indices, which denote the roll up vector of a graphene lattice that would form that specific SWCNT structure; simple expressions also relate these indices to the physical parameters of the nanotube such as its diameter and crystalline lattice angle relative to the tube axis10. Importantly, each (n,m) species has its own electronic and vibrational structure. For mixtures of (n,m)s REMs can thus become complicated superpositions. Here we instead investigate sorted SWCNT populations each highly pure in one particular (n,m), specifically, highly pure (7,6) SWCNTs sorted by aqueous two phase extraction (ATPE)11,12 and (6,5) SWCNTs sorted by conjugated polymer extraction (CPE, see Methods). Impurity levels of non-majority SWCNT contaminant species are at the level of a few percent. (Details are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Here, SWCNTs are not intentionally aligned and are expected to have random orientations on the surface, though locally, microscopically, they could become aligned due to deposition and drying.

Due to the complexity of the SWCNT electronic and phonon band structures we observe many RS bands including both well-documented bands and several not listed in popular tables13. One unlisted peak appears in the D-band region for the (7,6) SWCNT. Follow-up fixed wavelength RS shows other typically untabulated peaks. In dynamic experiments, we show how exposure to light alters REMs systematically. We show the connection between RS and photoluminescence (PL) features and show that excitons in SWCNTs interact with their surroundings in a defect-dependent way.

Results and discussion

Features in maps

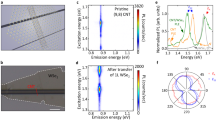

Briefly, our FS-REM system projects a linear color gradient (which we describe as a rainbow line) of excitation illumination (Fig. 1a). Using a flat homogenous sample, and dispersing scattered light perpendicularly enables almost instantaneous measurement of the excitation dependent RS, i.e., an REM6. In this work, the very high signal-to-noise ratios obtained mean that the measurement time is short relative to illumination induced damage or many other feasible manners of modulation, thus time-dependent evolution of even weak REM features in response to stimulus can be tracked. Triggering such evolution using illumination is represented schematically in Fig. 1b. Resulting representative REM maps are shown for dropcast (7,6) SWCNTs taken with no prior exposure to light (Fig. 1c), and after extended exposure to an intense rainbow line (Fig. 1d). (See Methods) Note that many time points can be, and are, measured at intermediate timepoints (vide infra). The color scale in Fig. 1c and Fig. 1d is saturated to bring out weaker features - an unsaturated map is presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. A difference map between the initial and final REMs is shown in Fig. 1e. In the REMs, RS bands appear as diagonal lines of slope near 1. Bands attributable to well-known SWCNT Raman modes are auto labeled with names from tables13. In the typical order of energy these are: Rayleigh scattering line (Ry), radial breathing mode (RBM) denoted here RB, transverse acoustic (TA), longitudinal acoustic (LA), intermediate frequency modes (IFM) denoted as I± and oTO, D, G, M± = M− and M+ - two separate bands here unresolved and suggested14 to really be a single band, iT=short for iTOLA, G*, 2D - also called G’, G + D, and 2G. Also, some additional combination modes can also be assigned: G + M±, G+iT, 3D, 2D + G. Although we use these names, for some bands the physical origin is not settled, and significant (n,m)-dependent deviations in energy (cm-1 shift) from general SWCNT values for some bands can be expected for our samples due to their small diameter.

a Schematic of broadband illumination and light collection. Angularly dispersed supercontinuum light creates a rainbow line on the sample which is analyzed. b Schematic sample evolution. Comparatively pristine SWCNTs are damaged by illumination. c REM of a (7,6) sample at the beginning of the measurements. RS from different phonon modes are visible as diagonal lines of signal intensity. Bands are labeled according to their tabulated names (see main text). d REM of the same (7,6) film after intense light exposure. e Difference plot highlighting the changes between the initial and final REM scattering intensities where red indicates an increase and blue indicates a decrease (noise is on the order of 30 counts). The dotted lines mark the expected position of the (7,6) E22 exciton optical absorption resonance based on ref. 1 from a surfactant-water dispersion. For all panels the color scale is in counts. Color scales are saturated and chosen to best reveal weak features - see Supplementary Fig. 3 for unsaturated versions. There is little change in RS for excitation <1.95 eV due to the illumination intensity profile and necessary filters. Videos of this evolution are shown in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Movies 1, 2 and 5).

Because of the high (n,m) purity of our samples, other bands of weaker intensity that would be unobservable in mixed samples are also detected. These less well understood or not commonly studied other bands we label a, b, c, and d. The band labeled b is of particular interest, since it is in the D band region. Band a may be a combination mode. Structure-dependent tables for larger diameter nanotubes15 suggest c and d are actually I− bands. For this band a value of 640 cm−1 is predicted for (7,6),15 however there are a number of peaks in a Raman shift range that are typically described as an IFM peak (the range of shifts in the hundreds of cm−1). For example, a peak at 475 cm−1 for (7,6) is classified as an IFM16, and a similar peak described elsewhere would extrapolate to below 400 cm−1 for the (7,6) structure17. Other tables use the name LA for a band expected at ≈356 cm−1 with an IFM- expected at ≈850 cm−1 for 633 nm excitation13. Another name (ZA) and physics has been proposed for this band14, and for the M and G* bands as well (TOZO, and TOLA)18. Actually, the very basis of the calculation of scattering cross-sections in nanocarbons has been critiqued19, and could lead to other name changes.

The intensity of any band as a function of excitation energy is its Resonant Raman Excitation Profile (REP). Compared to RS, REPs are relatively less studied, mainly because of the challenge of obtaining them, however, in principle they represent complementary information. However, with REMs, the REP comes for free. For non-resonant RS, scattering increases nearly proportional to the excitation energy to the fourth power; the resulting non-resonant profiles are monotonic and simple. Resonance completely overwhelms such profiles. In the simplest model, for a resonant RS band due to single phonon mode that is resonant with a single real electronic (/excitonic) state, two resonances will appear on its REM as plotted in Fig. 1. One resonance along the vertical line corresponding to emission resonance, and one along the horizontal line corresponding to excitation resonance (vertical and horizontal dotted yellow lines in Fig. 1, respectively)20. Resonances are added before squaring matrix elements to get the scattering probability, so they interfere coherently and a lifetime sets the width of each part separately (See Supplementary Note 1)7,21,22. The structure of the REP in this simplest picture7,20 would be a band in the top left quadrant of these two lines, most intense on the lines. Constructive or destructive interference could modulate the intensity.

These experimental REMs are not corrected for the intensity variation of the incident light, nor the sensitivity of the detection system, as these calibrations are non-trivial, however, this does not present difficulties for intercomparison as the effects are smooth. The net response of the instrument can be determined by comparison to a non-resonant RS signal, e.g., using a highly order pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) sample (Supplementary Fig. 4). The measured (uncorrected) RS from such a sample is peaked around 2.1 eV and drops off smoothly over hundreds of meV on either side. This reflects that the supercontinuum illumination is weak above 2.4 eV and increases in intensity as the excitation energy decreases, and that the detection efficiency is highest in the visible (≈2.2 eV) and drops off gradually as the energy decreases until a cutoff at ≈1.6 eV. All data in this contribution will reflect these effects, but any other features are attributable to intrinsic SWCNT sample photophysics. The HOPG reference is also useful to calibrate absolute intensities. Using the same illumination and collection conditions the G band maximum for HOPG was ≈ 2k counts·pixel−1min−1or (33 counts·pixel−1s−1) while for a (7,6) sample the G band was ≈ 40 kcounts·pixel−1s−1 (40k kcounts·pixel−1s−1), ≈ 1200× greater than HOPG. The enhancement is even greater using integrated intensity rather than peak values as the HOPG band has a somewhat narrower linewidth.

Without attempting to exhaustively describe each band and its behavior, the REMs show many interesting features. The G, M± and iT bands show a peak along the (vertical) emission resonance and a tail extending to the (horizontal) excitation resonance. The M± and iT bands show an extra resonance partway between these two bands.

Evolution of maps

We demonstrate the monitoring of the evolution of bands within REMs by exposing the sample to strong illumination. With such exposure to light many systematic changes occur in the REM; increasing the laser power speeds these changes (See Methods). Figure 1d is an REM measured after twenty minutes of intense illumination (see Methods). A video of the time evolution of the REM is shown in Supplementary Movie 1. Most bands have decreased in intensity, but the D band is stronger as are some other bands. These changes are easier to see in a difference plot (Fig. 1e) in which negative (decreased) intensity bands are colored blue and increased bands are colored red. A video of the difference map is shown in the Supplementary Movie 2. Most bands decrease (e.g., G, M±, iT and 2D).

The changes in signal are helpful for understanding the source of the different band features and their physics. The D band is known to be activated by defects, so if other bands evolve in the same way, we can conclude that they are also defect-activated. Notably, the peak labeled b decreases, so it is not related to scattering off defects (or at least not those being induced by illumination), and so, although it is in the D band area, it is unlike the normal D band. This band is also differentiated by a sharper REP concentrated at a lower energy than the primary D band.

Separately and strikingly, an even/odd rule emerges for bands related to the D band: for composite modes with an odd number of D phonons the intensity increases (D, G + D, 3D), for even numbers combinations of D the intensity decreases (2D, 2D + G). This highlights the special physics of the 2D band, and also indicates that if the band labeled a is a multi-phonon mode it is unlikely one of those phonons is a D band phonon.

Other bands, because they increase, can also be linked definitively to the presence of crystalline defects. One is matched to the tabulated LA mode13 (termed ‘IFM’ in refs. 16,17, and the band labeled d, which would be the I- band based on ref. 15. The IFM of refs. 16,17 has been previously reported to increase along with the D band in photo-damage RS measurements16,17, and theory has predicted several defect-activated peaks in this region23. Interestingly, ion irradiation also causes several peaks to grow in this region24. Multiple peaks have been also observed for highly ion irradiated semiconducting SWCNTs for 632.8 nm RS25. Comparable maps of the REMs to Fig. 1 for (6,5) SWCNTs are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6. These similarly show for the (6,5) species that the D band and two intermediate frequency bands (LA, I−) increase with the applied illumination and defect generation, indicating it is not a peculiarity of one species.

To improve the wavenumber resolution, increase spectral resolution, and so improve mode assignments, we also measured fixed wavelength RS for these SWCNTs and their dispersants with a 632.8 nm laser (Fig. 2). Excellent correspondence was obtained between RS measured using the fixed wavelength (632.8 nm) laser and the RS extracted from the corresponding slice of the REM, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. In Fig. 2, the (7,6) sample RS is shown in black, and although the (7,6) SWCNTs are coated with surfactant (sodium deoxycholate, DOC) as dropcast on CaF2 substrates for the measurement, none of the observed peaks for the sample correspond to DOC peaks (Methods). This is clear by comparison to the RS from a DOC-only control film (gray line). Although a strong double peak around 2900 cm−1 and some other weak RS features are observed, none of these peaks are seen in the SWCNT spectra. Many of the SWCNT RS peak positions match expectations from tabulated values (black labels and arrows), but somewhat shifted values (10’s of cm−1) are common. Deviations from those tables are expected as the tables are not (n,m) chirality specific and are derived mainly from larger diameter SWNCTs. Some bands (e.g., 2D) are easily matched. The bands at 1056 cm−1 and 1925 cm−1 are far from tabulated values but are strong and might still be identified as I+ and iT modes. Again, band a has no match. The cluster of three peaks 612 cm−1, 672 cm−1 and 706 cm−1 might possibly be related to the I− band. The band b, which could be considered a false D band, is at 1224 cm−1, lower than the true, very weak D band at 1303 cm−1. A weak peak at 1860 cm−1 may be a G + RBM satellite.

The Raman spectra measured with 632.8 nm laser excitation of the (7,6) SWCNTs (black) and their DOC surfactant alone (gray). The intensity of the black curve has been divided by 5 for easier comparison to other curves. The DOC has been multiplied by 25× to reveal DOC related peaks on this same scale. Above this, shifted up by a 6k count offset is the Raman spectra of the (6,5) SWCNTs (red) and their PFO-BPy polymer dispersant alone (light red). The intensity of the polymer RS has been multiplied by 2× to facilitate matching peaks in the (6,5) SWCNT material. Bands are labeled at their tabulated Raman shifts [10]. Experimental peak positions are labeled by their peak positions with gray arrows. The dotted blue lines identify possible assignments for bands that do not match very closely with tables [10]. The pink arrows with alphabetical labels (a–d) point to the Raman shifts of the extra Raman bands visible in the Raman Excitation Maps of Fig. 1.

Figure 2 also similarly reports RS for a CPE-separated (6,5) SWCNT film (red solid line) and a matching polymer only sample (pink). Most peaks in the (6,5) film come from the SWCNTs, however a number of clearly visible RS peaks in the 1000 cm−1 to 1500 cm−1 range are attributable to the polymer. Although far from resonance, the (6,5) RBM is visible at 306 cm−1. The peak at 417 cm−1 may be the LA mode13 (or IFM16,17, or ZA14). Other, ‘extra,’ peaks in the RBM region likely come from minority species in strong electronic resonance at 632.8 nm while the (6,5) is off resonance. RBM peaks at 281 cm−1 and 255 cm−1 are most likely due to a minority presence of the (7,5) and (10,3) species, respectively, that have excited state optical transitions (called E22 transitions) at ≈645 nm and ≈632 nm1. The (6,5) SWCNT E22 resonance in contrast is at ≈566 nm (2.19 eV), quite far from the 632.8 nm (1.96 eV) excitation wavelength. Minority species become comparatively more prominent, out of proportion to their numbers, when excitation is close to an electronic/excitonic resonance for the minor species, especially for modes with small resonance windows such as the RBM ( ≈ 35 meV). This has less effect for broadly resonant bands such as the G band (≈197 meV). Some of the peaks in the range 1700 cm−1 to 2000 cm−1 may be G + RBM modes.

Time evolution of bands and profiles

For the time-dependent changes presented in Fig. 1 due to strong illumination, the total illumination time was 20 min, while very high signal to noise (S/N) ratio single observations are acquirable in <<1 s (Methods, vide infra). Movies, including those shown in the Supplementary Information, were analyzed to determine integrated band intensities for selected prominent RS bands. Extracted band intensities for (7,6) SWCNTs are shown in Fig. 3a; labels are as in Fig. 1. The high time resolution makes clear that the evolution is not linear with illumination time for these samples. Most bands (G, RB, iT,2D, M±) decrease more quickly at first and then gradually. In contrast, the D band begins with a very low intensity, but after a short incubation period increases rapidly; it then slows asymptotically as time goes on. The I− and LA bands exhibit basically similar behavior, but are weaker in intensity, and the data is noisy at first. The intensity ratio of the integrated D to integrated G RS (D/G ratio) is plotted in Fig. 3b since it is a commonly used measurand for crystallinity in sp2 carbons26, (although care should be used for typical mixed-species SWCNT samples as the ratio is strongly affected by resonance effects7.) In this case, the ratio’s time evolution is qualitatively similar to, and dominated by, the D band’s evolution on its own. The starting D/G ratio of ≈1/100 indicates very high sp2 crystallinity before illumination, but after 20 min of light exposure is ≈1/10, indicating relatively poor crystallinity.

a The evolution of the integrated peak intensities for some prominent Raman scattering bands as a function of time for the (7,6) SWCNT sample. Some bands are divided or multiplied by a constant, shown in the label, to bring them onto the same scale (G, iT, 2D, M ± , I−). The I−, LA and RBM bands are noisier because they are partially cut off by the filters, but have been scaled as though the same range was sampled. b The ratio of D to G band integrated intensities as a function of time. c The time rate of change of the D/G intensity ratio in the near-linear increase phase. d The timescale associated with the change of D/G ratio at a given power. Error bars in c and d are standard errors (See Methods). e The signal-to-noise ratio for the G band integrated intensity as determined from a 100 meV excitation band as a function of integration time for several decades in laser power: full power (black solid line, black squares, ≈100 mW, No ND), 10× lower power (red dashed line, red circles, ND10), 100× lower power (blue dot dash line, blue diamonds, ND20), 1000× lower power (green dotted line, green triangles, ND30).

The rate of defect generation is important both to explore its fundamental mechanism, but also because it sets a practical timescale for conducting any other dynamic measurements. Therefore, we measured the rate of change of the D/G ratio for a series of different illumination powers spanning an order of magnitude. (See Methods) The rate of change of the D/G ratio is plotted versus power in Fig. 3c. The inverse, a characteristic time is plotted in Fig. 3d. The error bars in 3c and 3d are standard errors from a linear fit to obtain the rate. (See Methods). This timescale can be viewed as the time for SWCNTs to go from nearly perfectly crystalline, to highly defective, with a D/G ratio that extrapolates to 1. An order of magnitude increase in power led to approximately two orders of magnitude faster defect generation. Extrapolating this trend down to solar illumination levels suggests direct sunlight exposure would degrade pristine SWCNTs to being completely defective (D/G = 1) on 100-year timescales.

We checked to see if ambient air (e.g., oxygen) was rate limiting for the band evolution by repeating the experiments with a nitrogen flooded, and so oxygen starved, environment. (See Supplementary Fig. 8). REM evolution was similar overall over long times. This suggests either potential atmospheric contributors, i.e., O2, are not important for generating our illumination driven changes, or alternatively that more than this simple gas purge is needed to isolate their effects in these samples.

In a practical manner, Fig. 3d can also be used to determine a power at which the defect production rate is low enough that it does not interfere with any other dynamic process of interest. To determine this practical timescale and its power dependence, in Fig. 3e we plot the signal-to-noise ratio for the G band as a function of exposure time for four orders of magnitude in illumination. (The band was integrated over a 100 meV excitation range, see Methods) This shows that high quality data can be obtained with short integration times. At the highest illumination level (≈100 mW, no neutral density (ND) filter in line) the shortest integration time (1 ms) provides very high S/N (>100). Actually, the detector saturates which is why this curve is flat, and why the others flatten at long timescales. These curves would continue up if we took multiple short integrations and added them instead of using one long exposure. At lower illumination levels excellent S/N ratios, ≥100, are still obtained: in ms at 10× lower (ND10) illumination, 10’s of ms for 100× lower levels (ND20), and in ≈1 s for 1000× lower levels (ND30). This validates the capability to obtain high quality data in short timescales for measuring dynamic processes.

Measuring such changes is of course possible in single laser line RS alone16,17, however, REPs provide independent information about electronic energy levels and electronic timescales, so they can be of significant interest. Figure 4 shows REPs of four different bands (in rows, top to bottom, G, M±, iT and D) before (solid black lines) and after exposure to light (dotted red lines) with the integrated REP intensity plotted in the left column (panels a,c,e and g), and with the REPs normalized to their peaks in the right column (panels b,d,f and h). (Recall that these are modulated by the instrument to fall off smoothly on either side of a peak around 2.15 eV.) Here the illumination was done with a ≈1.95 eV short pass filter in line. The G band shows a broad resonance RS all the way from E22 (dashed gray line) to past E22 + G (gray dot-dashed line). On the normalized plots the REP peak shows only a slight broadening. This could, in principle, be RS process lifetime broadening – defects can act to reduce the possible dwell time in the excited states, which would lessen the scattering intensity and broaden the REPs. However, such an interpretation is complicated by the strong variation in SWCNT absorbance with wavelength (as well as the wavelength dependence of the illumination). The absorption being strongest near E22 would suggest the effect would be strongest near E22; so this seems more consistent with the data.

Raman excitation profiles (REPs) extracted from the REMs for the (7,6) SWCNT for four prominent bands (G, M, iT, D) showing their integrated intensities (panels a, c, e, g - left column) centered on the Raman band, and as scaled by their maxima (panels b, d, f, h - right column). Solid black lines are the initial REPs, dotted red lines are the final REPs. The expected position of the E22 resonance and the outgoing resonance (E22 + phonon mode energy) are labeled by the vertical dashed and dot-dashed lines respectively. The illumination is cutoff below 1.95 eV excitation. There are two gaps in the data for the D band coming from the optical filters in the setup.

Two of the bands (M± and iT) are interesting because their REPs show resonance-derived structure not just at the outgoing resonance (gray dot-dashed line) but also between it and the ingoing resonance (E22, gray dashed line). Some structure is expected for any band due to quantum coherence between ingoing and outgoing resonances20,21,22,27, however, the M and iT bands each result from RS processes involving two phonons. Literature identifies them as combinations of two TO phonons for the M± bands, and one TO and one LA phonon for the iT band13 (alternate origins have also been proposed18). Since two phonons are involved, there is the possibility of resonance on states not just at the ingoing and outgoing resonances of the mode, but also at energies originating from their single phonon components. This should result in resonances between the two points: one point in the middle if the mode is a combination of two phonons of equal energy, as expected for the M± band, or two separate points if the phonons are different. Such an REP structure is also predicted for the 2D band28. This is likely the origin of the intermediate resonance here.

As seen in the normalized plots (Fig. 4, panels b, d, f, h - right column), other than the decrease in intensity across the REP, there is very little change in REP shape. While the three bands discussed above show a significant loss in intensity, and a very slight increase in REP feature width, after illumination, in contrast, the D band intensity increases and the REP appears to narrow. A caveat is that the initial D band intensity is very weak, such that the shape at early times is poorly resolved and may be distorted by the other background because it is so weak. That said, if one band narrows while the others widen, it indicates the E22 exciton lifetime alone is insufficient to explain the changes.

Connections between scattering and luminescence

Photoluminescence (PL) is physically very different from Raman scattering. PL emission occurs when there is radiative recombination, and so is disrupted by any non-radiative recombination pathways. An additional ability of the FS-REM technique and one of the SWCNT samples we have chosen is that both the REMs due to RS and fluorescence (PL) emission from the direct bandgap can be monitored simultaneously. This is of particular interest as the fluorescence of SWCNTs is known to weaken under laser illumination, particularly with the generation of defects17,29,30. Laser illumination can also introduce deep energy levels and causes blinking and bandgap shifts29,30. (Sub-bandgap bound exciton states in SWCNTs (E11*) can be well controlled through specified functionalization, and are now called ‘color centers’31).

Unfortunately, for this contribution, both the intrinsic and sub-bandgap fluorescence from the (7,6) species are beyond the silicon detector’s range. This limits simultaneous real time tracking of the REM and PL emission here to the (6,5) SWCNT sample. This evolution, shown in Fig. 5, is striking. Figure 5a shows an initial (t = 0) map with RS bands presenting as diagonal lines on the right side of the REM. PL emission appears as vertical stripes close to the left-side axis. Raman bands are labeled as before, and the position1 of E11 fluorescence is labeled by the vertical dotted line. The sensitivity of the detector is poor here, causing the uncorrected intensity to be effectively less than the RS, but the (6,5) E11 PL peak is clearly visible; note that any fluorescence from significantly shifted E11* states are not captured with this detector.

a Raman excitation map at the beginning of the measurements also showing PL emission from (6,5) SWCNTs at E11 (vertical band labeled by dotted line at 1.267 eV). The apparent slopes of the RS features are steeper than prior plots due to the much narrower excitation range and broad emission range tailored to allow observation of SWCNT PL. b Map after 300 s of light exposure (see Methods). c Difference plot of the final (t = 300 s) minus initial observed emission in which red indicates an increase and blue indicates a decrease. A large new emission feature apparently resulting from illumination induced defects in the wrapping polymer is observed. In all plots bands are labeled according to their tabulated names (see main text). The horizontal dashed line marks the E22 exciton optical absorption resonance from tables derived from surfactant wrapped SWCNTs [1]. The color scale is in counts. d Time evolution of the photoluminescence (PL) emission from the E11 band of the (6,5) SWCNT (black solid line, labeled as E11), from the PFO-BPy polymer (red dashed line), the Raman D band multiplied by a factor of 5 (green dotted line) and the Raman G band (blue dot-dashed line). Videos showing the changes in the maps are in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Movies 3 and 4). Photoluminescence intensity is calculated by integrating over a 75 meV excitation window (2.150 eV to 2.225 eV), in a width of 10 meV (80 cm−1) in the middle of the luminescence peak. Raman peak intensity was determined over the same excitation window with the same 10 meV width centered on the Raman band. For the RS peaks, a background was subtracted as calculated from the average local intensities adjacent to but not comprising the feature. For PL bands the nearly emission-free region at 1.5 eV emission energy was used for background subtraction.

Figure 5b shows the same excitation - emission range for the (6,5) film after 300 s of exposure to the rainbow line. (For video, see Supplementary Movie 3). The most prominent change is the emergence of a new broad PLE peak emitting at ≈1.8 eV, but centered at an excitation wavelength matching the peak E22 absorbance of the (6,5) nanotube. Other changes are more subtle and show up better in the difference plot in Fig. 5c. (For the video version, see Supplementary Movie 4) Notably the (6,5) E11 fluorescence drops as the new fluorescence peak increases. It is also clear that the D band increases while the G band decreases slightly. The evolution of most other bands is weaker and difficult to evaluate due to the superimposition of the large emission at 1.8 eV. By comparison to a control sample comprised of PFO-BPy only (Supplementary Fig. 9) we identify the new peak as emission from the polymer. So, as defects are created, the E11 fluorescence of the SWCNT decreases, and the PL emission from the polymer increases. Exciton recombination at the infrared bandgap is falling off and recombination is taking place instead in the polymer in the visible red to infrared range.

While surprising, this peak can be understood in the context of earlier work. The PFO-BPy polymer is in close contact with the (6,5) SWCNTs. Excitons in the polymer can recombine via energy transfer to SWCNTs32. Transfer of photoexcitations from (6,5) SWCNTs to surrounding wide-gap polymer has also been reported33. In this instance, the excitons generated via absorbance into the SWCNT E22, initially (fractionally) recombining to emit bandgap PL at E11, are, post-illumination, transferring to the polymer in which they are recombining to emit vis-NIR PL. SWCNTs are known for their strong NIR emission, so it is intriguing that this defective SWCNT-polymer blend instead shows visible light emission, though it is weak.

This can all be tracked quantitatively, and the time evolution of the D and G bands, SWCNT E11 PL, and the polymer PL(Ep), are plotted in Fig. 5d. The SWCNT E11 fluorescence intensity drops monotonically; the G band drops similarly, although more quickly at first. The D band increases at quickly first, followed by slower growth, while the polymer PL emission continues to increase nearly linearly. This suggests that defect production continues unaffected, but that the D band becomes less sensitive to the continued increase.

We interpret these observations as the illumination creating crystalline defects that cause PL efficiency to fall as non-radiative recombination (or radiative recombination in long wavelength emitting defect E11* states) increases. Excitons created in excited states of the SWCNT (e.g., E22) instead of radiative combination are transferred to the surrounding PFO-BPy polymer environment in which some recombine and emit at the Ep feature. The G band intensity drop can be explained by a decrease in lifetime in the excited states caused by an increasing number of photo-induced defects. The saturating behavior of the D band can be rationalized when the density becomes greater than the scattering length of an individual defect in a previously crystalline stretch of the tube, i.e., the defects overlap and decrease the summed contribution. The nanotube continues to absorb efficiently at E22, but excitons that would have relaxed to E11 and recombined radiatively instead leak out and recombine in the surrounding polymer.

The findings above on a test experimental system of illumination driven evolution in SWCNT films show both the potential of the FS-REM method for detailed investigations of modulation in such materials and insight into potential limitations. The rapidity of collecting an REM enables the exploration RS and REPs statically on pristine materials. Tracking of the time evolution as material is changed is demonstrated. We explored changes on the minute time scale here, but the signal-to-noise plots prove that millisecond time scales - or shorter - are accessible. Timescales for photodamage were estimated, indicating that if very low defect densities are needed, exposure to intense light should be avoided. It is seen that RS band evolution due to defect generation is complex and modes can be divided into bands that strengthen and those that weaken. REPs revealed band-dependent structure due to ingoing, outgoing, and likely (for multiple phonon modes) intermediate resonances but changed only slightly if at all with photodamage. These dynamic studies highlight how SWCNTs are intimately linked to their surrounding environment, capturing photons to create excitons which recombine in surrounding polymer and emitting visible light.

Important takeaway messages from this work are that REMs can be obtained quickly enough that dynamical experiments are possible. If bands are observed to evolve in a similar way, that suggests a common underlying mechanism. Here, several bands were linked to crystallinity, and one other band near the D band unlinked. Light exposure causes large changes to RS intensities with smaller or possibly negligible changes to REPs. As always, SWCNTs are intimately connected with their environment, particularly neighboring polymer, and here we saw that crystallinity is a factor. Defective SWCNT-polymer mixtures can even become visible light emitters, although weak.

Conclusions

Full spectrum REM has been used to investigate the initial state and time-dependent evolution of many vibrational (RS) and electronic (REP) features of highly pure separated (7,6) and (6,5) SWCNTs species populations. REM and RS show many previously identified and tabulated bands as well as some normally untabulated bands that may be visible due to the (n,m) purification. REPs show significant structure for several bands (G, iT, M±). As a test method for driving material evolution, intense illumination is found to cause rapid generation of photo-defects, substantially affecting RS intensities along with subtle REP changes that are readily tracked. For most bands the RS was found to decrease slightly with induced SWCNT defectiveness while other bands such as the D, LA, and I- increased, with an even-odd rule for D band related combinations directly observed. Dynamic data shows the evolution of various RS and PL bands also aiding in identification; an example is for the untabulated false D-band at 1224 cm−1 in the (7,6) SWCNT, which is observed to have its own excitation resonance. Evaluation of matrix, environmental, effects was also demonstrated. For CPE separated SWCNTs in a film of surrounding polymer it was observed that, as the defectiveness was increases with strong illumination, excitons would transfer from the SWCNTs into the surrounding polymer leading to decreased SWCNT bandgap fluorescence and emission via visible and infrared luminescence from the polymer. These results provide insights into the optical properties of SWCNTs, and suggest the future is promising for rapid dynamic REM measurement.

Methods

Certain equipment, instruments, software, or materials, commercial or non-commercial, are identified in this paper in order to specify the experimental procedure adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement of any product or service by NIST or National Research Council Canada, nor is it intended to imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Sample preparation - (7,6) SWCNT

The (7,6)-rich SWCNT population used in this work was prepared via aqueous dispersion, centrifugation-based purification, and ATPE separation11,12. In brief, a tip sonication-based dispersion of SWCNTs synthesized via the cobalt-molybdenum-catalyst (CoMoCat) synthesis method (CG400, Chasm Nanotechnologies, USA) was purified by simple centrifugation retaining the supernatant followed by rate-zonal centrifugation and ATPE separation as previously described. This results in a highly purified dispersion of straight, rodlike, SWCNTs without attached catalyst particles. This nanotube source also results in the nanotubes being filled by water in their endohedral volume. Stirred ultrafiltration cells (Millipore) were used to iteratively remove solution components (e.g., iodixanol, ATPE polymers) and to concentrate and exchange via back dilution the SWCNT populations into set surfactant solution concentrations such as to 10.0 g/L (1.0 % mass/volume) sodium deoxycholate (DOC) in water.

Sample preparation - (6,5) SWCNT

The (6,5)-rich SWCNT population used in this work was prepared via organic dispersion, tip-sonication and centrifugation-based enrichment using conjugated polymers6,7,34. In brief, a tip sonication-based dispersion of SWCNTs synthesized via the cobalt-molybdenum-catalyst (CoMoCat) synthesis method (SG65i, Sigma-Aldrich Catalogue# 773735) was purified using poly[(9,9-dioctylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl)-alt-co-(6,6’-{2,2’-bipyridine})] (PFO-BPy) in toluene. This results in a highly enriched dispersion of (6,5) SWCNTs. The enrichment was repeated for multiple cycles to maximize the yield, and the cycles were named pre, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and so on. The 3rd cycle enriched (6,5) was used to prepare film for the Raman analysis.

Substrate preparation

Films of the (7,6) SWCNTs, PFO-BPy polymer, and DOC surfactant were produced by a liquid dropcasting method. A pipette dispensed 10 µL of liquid dispersion on a 15 mm diameter 1 mm thick polished disk CaF2 Raman grade substrate (Crystan) and dried in air to form a film. This process was repeated with a second drop if it was thought necessary to have enough material.

For the (6,5) SWCNT, filtration was used instead7,34. The (6,5) SWCNT – PFO-BPy in toluene suspension was filtered through a PTFE membrane (pore size 0.2 μm) by gravity (without vacuum), and the films were rinsed with plenty of toluene to remove excess polymer. This made an optically thick, purple-colored, film on the membrane. The membrane was affixed with tape on a glass slide for measurements.

Raman excitation mapping

The general optical configuration of the FS-REM instrument is as detailed in ref. 6. Briefly, a supercontinuum white light laser (NKT Photonics EXR-15) was the light source. A filter stage blocks unwanted infrared light (>785 nm). To obtain high quality RS data not compromised by excessive Rayleigh scattering five sets of filter pairs were used, each consisting of an excitation filter and emission filter. Excitation-side filters were short wave pass filters, and the emission filters were long wave pass filters. Each pair had a different cutoff (nominally (564, 600, 633, 700, and 750) nm). A 300 lines/mm (lpmm) transmission excitation grating (ExG) dispersed the white light spectrally along one axis. A 10× infinity-corrected long working distance objective tilted at 60 degrees from the sample normal was used to focus the illumination into a “rainbow line” on the sample. The entire rainbow line (with no filters) was ≈0.8 mm long by ≈10 µm wide on the sample, dispersing wavelengths from ≈500 nm to ≈785 nm (i.e., a 285 nm range) spatially on the substrate. A neutral density filter was used for the static measurements; the total power of illumination was 100 mW according to a silicon photodiode (corresponding to a mean surface power density of 12 µW/µm2). For the photodamage experiments, a neutral density filter was removed and the total illumination power was 240 mW (30 µW/µm2)

Scattered light was collected by a second 10× infinity-corrected long working distance objective on axis with the substrate. This was filtered with the long wave pass filter and dispersed by a 300 lpmm transmission grating. A 75 mm tube lens was used to focus the light on a cooled sCMOS camera (Andor Neo). The wavelengths of emission and excitation were calibrated with band-pass filters. Raman excitation maps were made by calibrating camera pixels to the wavelength and then converting the wavelength to energy. The intensities were not changed to compensate for sampling in terms of energy as opposed to wavelength. Plots of REMs are generated by the python package matplotlib.pcolormesh. Raman excitation profiles were made from the REMs by summing over a 12-pixel width centered on that band.

Fixed wavelength Raman spectroscopy

For fixed wavelength RS, an unpolarized 632.8 nm HeNe laser (Thorlabs) was used at ≈1 mW incident power. The laser reflected off a 45° dichroic mirror appropriate to the wavelength (Semrock) and focused on samples by a 50×, 0.65 numerical aperture, microscope objective (Mitutoyo) onto the sample. The scattered light was collected by the same objective, passed back through the dichroic mirror and the remaining Rayleigh scattering was blocked by an appropriate edge filter (Semrock). This collimated light was focused by a 10 cm focal length achromatic lens onto an 8 µm wide slit on a 0.3 m spectrometer (Andor Kymera) with a 300 line/mm grating blazed at 1 µm and focused onto a 256 × 2000 pixel charged coupled device (CCD) array (Andor iDus416) multitracked into 7 evenly spaced 32-pixel high tracks, with the data taken from the central track. Collection time was 1 s. Raman shifts were calibrated by comparison to acetamidophenol RS using peaks from standard tables35.

Signal-to-noise

The signal-to-noise was estimated by taking 5 successive single integration scans for each set of conditions (laser power and integration time). A background field using the same integration time was subtracted from all five. A window 20 pixels wide (≈12 meV wide) centered on the G band peak, and ranging from 2.00 to 2.100 eV in excitation (100 meV high), was defined. The signal-to-noise was defined as the mean of those five measurements divided by the population standard deviation.

Time evolution

For the photo-evolution of the (7,6) SWCNT, a lower power (ND filter in place) map was made over the entire range using all 5 filters. Then the ND filter was removed to increase the power, with the allowed illumination wavelength range controlled by use of only the 632.8 (1.95 eV) filter set. This means that illumination at energies below 1.95 eV was blocked. The sample was exposed to illumination for 20 min, with a 250 msec exposure taken every 20 s to get the dynamical evolution. Then the power was reduced back down to the original (lesser) power level and REMs taken using the full complement of filter sets. For the (6,5) SWCNT and polymer film sample, the high-power illumination was applied using a 583 nm shortpass and 600 nm longpass filter.

Defect generation rate

Integrated intensities for the D and G band were taken by summing over a 10 pixel by 10 pixel square, slightly wider than the G band width. A background was taken from midway between the D and G band. The resulting integrated D/G ratio was measured at even time intervals ranging from 2 s to 10 s depending on the power level, which was measured with a silicon photodiode and varied over an order of magnitude. The D/G from frame 10 to frame 40 appeared nearly linear. This linear slope was fit to obtain d(E22/IG)/dt – the rate of change of the D/G ratio. The fit was performed by the python module lmfit36 using the linear module. The error bars are automated estimates of the standard errors in the slope as reported by the lmfit module. The inverse of this rate is the characteristic time for the D/G ratio to change (i.e. to go from 0 to 1).

Simultaneous Raman and fluorescence

RS features and fluorescence features are widely separated in wavelength, with RS features typically shifted <100 nm in absolute wavelength from their excitation (visible) laser line, while fluorescence features are located on average at ≈1.7× the laser wavelength37 in the short-wavelength infrared. For the REM measurements alone, optical system was optimized for the REM range, but as a result PL was dispersed outside the detector’s acceptance angle. To detect RS and PL simultaneously, the angle of the detection beam leg with respect to the emission grating was increased. This exact instrumental configuration is a compromise to enable simultaneous measurement and decreases the signal to noise ratio in the Raman region, i.e., close the laser line. The exact wavelength-dependent emission-side response function is therefore also somewhat different than for the other experiments. For the time evolution of PL and RS (Fig. 5), equal areas in energy (excitation energy range × emission energy range) are tracked for each feature.

Gas atmosphere

All data shown in the main text were gathered in an ambient air atmosphere. To check if the RS and PL evolution behavior was sensitive to the presence of the typical O2 concentration in air, a separate set of experiments isolating the sample and objectives in a controlled environment were conducted. For these, the sample was contained within a 2.7 L volume box of 3/16” thick plastic-coated foam core cardboard (Thorlabs TB4) sealed with glue and tape, and the box was purged with pure nitrogen gas collected from the boil-off of a liquid nitrogen tank for >20 min at a gas flow rate of 1 standard L per min (sLm). Some data from nitrogen purged experiments is reported in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Weisman, R. B. & Bachilo, S. M. Dependence of optical transition energies on structure for single-walled carbon nanotubes in aqueous suspension: an empirical Kataura plot. Nano Lett. 3, 1235–1238 (2003).

Kataura, H. et al. Optical properties of single-wall carbon nanotubes. Synth. Met. 103, 2555–2558 (1999).

Jorio, A. & Saito, R. Raman spectroscopy for carbon nanotube applications. Appl. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 021102-01–021102-27 (2021).

Finnie, P., Ding, J., Li, Z. & Kingston, C. T. Assessment of the metallicity of single-wall carbon nanotube ensembles at high purities. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 30127–30138 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Raman microscopy mapping for the purity assessment of chirality enriched carbon nanotube networks in thin-film transistors. Nano Res. 8, 2179–2187 (2015).

Finnie, P., Ouyang, J. & Lefebvre, J. Full spectrum Raman excitation mapping spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 10, 9172 (2020).

Finnie, P., Ouyang, J. & Fagan, J. A. Broadband full-spectrum Raman excitation mapping reveals intricate optoelectronic–vibrational resonance structure of chirality-pure single-walled carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano. 17, 7285–7295 (2023).

Li-Pook-Than, A., Lefebvre, J. & Finnie, P. Phases of carbon nanotube growth and population evolution from in situ Raman spectroscopy during chemical vapor deposition. Phys. Chem. C. 114, 11018–11025 (2010).

Li-Pook-Than, A., Lefebvre, J. & Finnie, P. Type- and species-selective air etching of single-walled carbon nanotubes tracked with in situ Raman spectroscopy. ACS Nano 7, 6507–6521 (2013).

Saito, R., Dresselhaus, G., & Dresselhaus, M. Physical Properties of Carbon Nanotubes (World Scientific, 1998) Chapter 3, pp. 35–58

Fagan, J. et al. Isolation of specific small diameter single-wall carbon nanotube species via aqueous two-phase extraction. Adv. Mater. 26, 2800–2804 (2014).

Fagan, J. Aqueous Two-polymer phase extraction of single-wall carbon nanotubes using surfactants. Nanoscale Adv. 1, 3307–3324 (2019).

Jorio, A., Saito, R., Dresselhaus, G., & Dresselhaus, M. Raman Spectroscopy in Graphene Related Systems (Wiley-VCH, 2011) Table 14.1 p 329

Vierck, A., Gannott, F., Schweiger, M., Zaumseil, J. & Maultzsch, J. ZA-derived phonons in the Raman spectra of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 117, 360–366 (2017).

Wang, J., Yang, J. & Li, Y. Structure dependence of the intermediate-frequency Raman modes in isolated single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 23826–23832 (2012).

Soltani, N., Zheng, Y., Bachilo, S. M. & Weisman, R. B. Structure-resolved monitoring of single-wall carbon nanotube functionalization from Raman intermediate frequency modes. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 7960–7966 (2023).

Inaba, T., Tanaka, Y., Konabe, S. & Homma, Y. Effects of chirality and defect density on the intermediate frequency Raman modes of individually suspended single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 9184–9190 (2018).

Tyborski, C., Vierck, A., Narula, R., Popov, V. N. & Maultzsch, J. Double-resonant Raman scattering with optical and acoustic phonons in carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214306 (2018).

Heller, E. J. et al. Theory of graphene Raman scattering. ACS Nano 10, 2803–2818 (2016).

Duque, J. G. et al. Violation of the Condon approximation in semiconducting carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 5, 5233–5241 (2011).

Duque, J. G. et al. Quantum interference between the third and fourth exciton states in semiconducting carbon nanotubes using resonance Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 117404 (2012).

Tran, H. N. et al. Excitonic optical transitions characterized by Raman excitation profiles in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 94, 075430 (2016).

Weight, B. M., Zheng, M. & Tretiak, S. Signatures of chemical dopants in simulated resonance Raman Spectroscopy of Carbon Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 1182–1191 (2023).

Skákalová, V., Maultzsch, J., Osváth, Z., Biró, L. P. & Roth, S. Intermediate frequency modes in Raman spectra of Ar + -irradiated single-wall carbon nanotubes. physica status solidi (RRL) – Rapid Res. Lett 1, 138–140 (2007).

Kalbacova, J. et al. Defect evolution of ion-exposed single-wall carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 2496–2505 (2019).

Tuinstra, F. & Koenig, J. L. Raman Spectrum of Graphite. J. Chem. Phys. 53, 1126–1130 (1970).

Moura, L. G. et al. Raman excitation profile of the G band in single-chirality carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035402 (2014).

Popov, V. Two-phonon Raman bands of single-walled carbon nanotubes: a case study. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085413 (2018).

Georgi, C. et al. Photoinduced luminescence blinking and bleaching in individual single-walled carbon nanotubes. ChemPhysChem 9, 1460–1464 (2008).

Finnie, P. & Lefebvre, J. Photoinduced band gap shift and deep levels in luminescent carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 6, 1702–1714 (2012).

Brozena, A. H., Kim, M., Powell, L. R. & Wang, Y. Controlling the optical properties of carbon nanotubes with organic colour-centre quantum defects. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 375–392 (2019).

Eckstein, A. et al. Excitation quenching in polyfluorene polymers bound to (6,5) single-wall carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. 467, 1–5 (2016).

Kuang, Z. et al. Charge transfer from photoexcited semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes to wide-bandgap wrapping polymer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 25, 8125–8136 (2021).

Ouyang, J. et al. The impact of conjugated polymer characteristics on the enrichment of single chirality single walled carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4, 6239–6254 (2022).

E1840-96 Standard Guide for Raman Shift Standards for Spectrometer Calibration (ASTM International, 2014) 6.

Newville, M., Stensitzki, T., Allen, D. B., Ingargiola, A. LMFIT: Non-linear least-square minimization and curve-fitting for python. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11813 (2014).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Ratio problem in single carbon nanotube fluorescence spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 207401 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.F. made the measurements and processed the data. P.F. analyzed the data with J.F. J.F. made (7,6) samples, J.O. made (6,5) samples. P.F. drafted the manuscript. P.F. and J.F. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the data and corrected the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Vishal Govind Rao and Jet-Sing Lee. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Finnie, P., Ouyang, J. & Fagan, J.A. Static and dynamic Raman excitation mapping of chirality-pure carbon nanotube films. Commun Mater 6, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00727-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00727-6