Abstract

While reducing current collector thickness improves battery energy density, further thinning commercial collectors compromises mechanical integrity and increases manufacturing costs. Here, we overcome these limitations by developing a lightweight (1.23 mg·cm-2), cost-effective cellulose composite membrane (CCM) via solution casting from an alkali/urea solvent. This CCM, composed of modified carbon nanotubes and natural cellulose, exhibits high electrochemical stability and flexibility, serving as both cathode and anode current collectors. CCM-containing batteries show 99.40% capacity retention after 500 cycles at 3 C. Replacing commercial collectors with CCM reduced their battery proportion to 6.23% and increased gravimetric energy density by 41.32%, while also reducing current collector costs by 50.36%. The CCM, produced through regenerated cellulose technology, is suitable for industrial-scale production, offering a strategy to enhance battery energy density with lightweight, low-cost current collectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite three decades of development pushing lithium-ion battery energy density to 150–210 Wh·kg−1 (approaching theoretical limits)1, increasing energy demands require alternative solutions2. Reducing commercial current collector weight, representing 8–15% of total battery mass3,4, is a key strategy. While aluminum and copper collector thicknesses have been reduced to 6 µm and 10 µm, respectively5, further thinning compromises mechanical integrity, increasing wrinkling and cracking during coating6. Additionally, thinning processes and record-high aluminum and copper prices drive up manufacturing costs, hindering LIBs development7. Therefore, lightweight, low-cost current collector materials are crucial alternatives to commercial metal foils7.

Cellulose, an abundant and renewable resource, offers advantages such as low cost, lightweight nature, and good chemical/electrochemical stability, weldability, and mechanical strength8,9. While cellulose-conductive carbon nanocomposite membranes have been explored as current collectors10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, their production using cellulose nanomaterials often results in nanoscale mixing, leading to uneven conductive carbon dispersion and reduced conductivity. This necessitates a high mass proportion of conductive carbon to achieve adequate conductivity. Current cellulose nanomaterial preparation methods are difficult to scale industrially, due to immature technology19. Additionally, these methods are energy-intensive and generate significant wastewater, posing environmental sustainability challenges20. Consequently, the economic and social sustainability of cellulose nanomaterials is compromised.

This study developed a lightweight, low-cost cellulose composite membrane (CCM, Table 1) for simultaneous use as both cathode and anode current collectors, aiming to enhance LIBs gravimetric energy density. Fabricated via a simple solution casting method utilizing regenerated cellulose technology from an alkali/urea solvent, CCM features molecular-scale mixing of modified carbon nanotubes and natural cellulose. Its lightweight nature (1.23 mg·cm−2) allowed for a reduction in current collector proportion within the battery to 6.23%, resulting in a 41.32% improvement in overall gravimetric energy density. Furthermore, CCM reduced current collector costs by approximately 50.36%. Leveraging regenerated cellulose technology, CCM is suitable for industrial-scale production.

Results and discussion

Fabrication and structure of CCM

Regenerated cellulose technology, refined over a century, is now industrially mature19. In this study, CCM was prepared via a simple solution casting method using this technology in an alkali/urea solvent system (Fig. 1a). This process rapidly dissolved cellulose with pre-dispersed carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs, Table 1), achieving molecular-scale mixing. During regeneration, cellulose chains, bonded via hydrogen bonding, coated the MWCNTs skeletons, ensuring close contact and facilitating rapid electron transport (Fig. 1b).

A techno-economic analysis (Supplementary Table 1) indicated a CCM cost of 12252.2 USD per ton. Replacing aluminum and copper foils with CCM as cathode and anode current collectors reduced costs by 50.36% (Supplementary Discussion 1). Laboratory pilot production demonstrated a CCM production efficiency of 0.95 m2·h−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Discussion 2, Supplementary Movie 1, and Supplementary Movie 2).

Characterizations of CCM

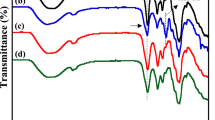

Figure 2a shows the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of MWCNTs, CM (cellulose membrane, Table 1), and CCM (Supplementary Data 1). In the MWCNTs spectra, the peak at 1714 cm−1 corresponds to the C = O absorbance in carboxyl groups21, while absorption peaks at 1448–1666 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibration of the MWCNTs backbone C = C22. For CM, the FTIR spectra exhibit the characteristic absorbance of cellulose II23, with peaks at 3452 cm−1, 2902 cm−1, and 1116 cm−1 corresponding to the stretching vibrations of O-H in hydroxyl groups, C-H in methylene (-CH2) groups, and C-O-C in β-1,4 glycosidic bonds24. In the CCM spectra, the O-H absorption peak, initially at 3453 cm−1, shifted to 3428 cm−1, indicating MWCNTs incorporation into the cellulose membrane via hydrogen bonding. This intermolecular hydrogen bonding facilitated MWCNTs dispersion within cellulose, preventing agglomeration (Fig. 2c, e, Supplementary Fig. 2). Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) analyzed the detailed pore structure of CCM (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Data 5). Due to its ultra-high porosity of 90.23%, CCM exhibits a lightweight areal mass density of 1.23 mg·cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Notably, the entangled MWCNTs formation in CCM resulted in increased surface roughness compared to CM (Fig. 2d, f). This higher roughness significantly reduces the contact resistance between the current collector and the electrode25.

Cellulose molecular chains covered and tightly connected the MWCNTs. Consequently, CCM, based on the entangled structure of MWCNTs and cellulose molecular chains, demonstrated improved mechanical properties (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 1, Supplementary Table 3). Tensile stresses and Young’s moduli were measured at 39.82 MPa and 2329.31 MPa for CCM, and 13.54 MPa and 736.52 MPa for CM, respectively. The improved tensile strength of CCM enabled it to better withstand the mechanical load of the electrode coating process26. CCM exhibited high flexibility under various physical deformations, including bending, folding, and twisting (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Its flexibility was primarily attributed to its full fiber structure and the hydrogen bonding between MWCNTs and cellulose molecular chains14. The tightly connected MWCNTs allowed CCM with a 1:1 weight ratio to achieve a conductivity of 8.24 S·cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 4c, Supplementary Data 5c). Conductivity was low below this ratio due to higher contact resistance from the cellulose cover. When the ratio was exceeded, excess MWCNTs compromised mechanical properties, making preparation difficult.

Characterizations of CCM-Based Electrodes

CCM’s lightweight nature, excellent mechanical properties, and favorable surface roughness make it suitable for replacing metal foils in lithium battery manufacturing. CCM demonstrated good stability within a wide electrochemical window (0–5.0 V), making it well-suited for both cathode and anode current collectors (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Data 5). Field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of CCM-LFP (Table 1, CCM-based LiFePO4 cathode) cross-sections revealed dense contact between the electrode and current collector, facilitated by CCM’s favorable surface roughness, which reduced interfacial contact resistance (Fig. 3a). Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) maps confirmed the distribution of P and Fe in the electrodes, highlighting this dense contact in CCM-LFP (Fig. 3c, d). Furthermore, stress during the drying process compacted the CCM, increasing MWCNTs density. Consequently, CCM-LFP exhibited a conductivity of 4.12 S·cm−1, significantly higher than AL-LFP’s (Table 1, aluminum foil-based LiFePO4 cathode) 0.87 S·cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Data 5).

a SEM images of the cross-section of CCM-LFP. b SEM images of the cross-section of CCM in CCM-LFP. c Energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) maps of CCM-LFP. d Elemental mapping images of C, P and Fe in the electrode components in CCM-LFP. e, f Galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) curves of CCM-LFP | |Li (mass loading of 1.35 mg·cm−2) and Al-LFP | |Li (mass loading of 0.68 mg·cm−2) at different current rates from 0.1 C to 5 C. Over potential-current density (g) and Capacity retention-current density plots (h) of CCM-LFP | |Li and Al-LFP | |Li.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of CCM-LFP and Al-LFP were shown in Supplementary Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7b (Supplementary Data 5). The potential differences at various sweep rates were notably lower for CCM-LFP than Al-LFP, primarily due to reduced cathode-CCM contact resistance. The densified CCM retained some pore structure (Fig. 3b), and the abundant hydroxyl groups on its inner surface exhibited high electrolyte affinity (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Data 5)27, allowing electrolyte retention for promoting lithium ion transport.

CCM-LFP | |Gr-NP-CCM (Table 1) showed inferior rate performance compared to CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM (Table 1, CCM-Gr: CCM-based graphite anode; NP-CCM: nonporous CCM) (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Data 5), confirming that CCM’s pore structure facilitates electrochemical reactions by electrolyte absorption. The Li-ion diffusion coefficient for CCM-LFP was 3.47×10−10 cm2·s−1, an order of magnitude higher than Al-LFP’s 1.12×10−10 cm2·s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). This reduced contact resistance and increased Li-ion diffusion coefficient enabled faster Li-ion transport, significantly enhancing battery rate performance. CCM-LFP | |Li exhibited superior rate performance due to reduced interfacial resistance. The discharge capacity of CCM-LFP | |Li reached 152.90, 147.88, 139.68, 130.70, 118.58, 109.88, 103.03, and 97.27 mAh·g−1 at current rates from 0.1 to 5 C (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Data 2). In contrast, Al-LFP | |Li (Table 1) demonstrated inferior rate capability (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Data 5), with significant capacity fading at 5 C and retaining only 65.19 mAh·g−1 (capacity retention: 44.31%) at 5 C (Fig. 3f, h, Supplementary Data 2). CCM-LFP | |Li also exhibited lower overpotential than Al-LFP | |Li, indicating improved current collector-electrode interfacial contact resistance (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Data 2). Given graphite’s significantly higher conductivity compared to LFP28,29, negligible rate performance differences were observed between CCM-Gr | |Li (Table 1, CCM-based graphite cathode) and Cu-Gr | |Li (Table 1, copper foil-based graphite anode) (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Data 5). The first charge and discharge galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) curves showed initial Coulombic efficiencies of 95.00% and 93.53% for CCM-LFP | |Li and Al-LFP | |Li, respectively, and 92.54% and 91.30% for CCM-Gr | |Li and Cu-Gr | |Li, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Data 5). CCM’s porous structure did not affect the battery’s initial coulombic efficiency30,31.

The structural stability of the electrodes was examined, with detailed FTIR spectra of CCM, poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF), and CCM-LFP elucidating the interaction between the electrodes and CCM (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Data 3). In the PVDF spectra, characteristic absorption peaks at 1402 cm−1, 1187 cm−1, and 879 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of -CH2, -CF2, and C-C, respectively32. Absorption peaks at 792 cm−1 and 760 cm−1 were exclusive to the α-phase, while peaks at 841 cm−1 and 1270 cm−1 were exclusive to the β-phase32. In the CCM-LFP spectra, absorption peaks at 900–1200 cm−1 and 460–650 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibrations of P-O and the asymmetric and symmetric modes of O-P-O in LiFePO433. While characteristic peaks of both α- and β-phases appeared in the CCM-LFP sample, -CF2 absorption peaks were not detected, likely due to the high infrared absorption intensity of LiFePO4 masking them (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Data 5). These FTIR results indicated stable bonding between the electrode and CCM, with no evidence of chemical reactions.

a Detailed FTIR spectra of CCM, PVDF, and CCM-LFP at 1650–460 cm−1 region. b XRD and c DSC spectra of PVDF, CCM and CCM-PVDF. d Cycling performance of CCM-LFP | |Li (mass loading of 1.5 mg·cm−2) and Al-LFP | |Li (mass loading of 0.97 mg·cm−2) at 3 C. e Capacity fade versus current rate for various LFP-based cathodes42,43,44,45,46,47,48. f AC impedance spectra of CCM-LFP | |Li and Al-LFP | |Li. g Photographs exhibit the disassembled cells after the 500 charge-discharge cycles at 3 C. Photos of CCM-LFP and Al-LFP before (h) and after (i) 10 s of sonication.

The molecular bonding of CCM-LFP at the current collector and electrode interface was further investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Compared to the XRD patterns of CCM and PVDF, the XRD pattern of CCM-PVDF (CCM coated with a 1 wt% PVDF solution) exhibited the characteristic diffraction peaks of CM at 12.2°, 20.3°, and 21.5°, and those of MWCNTs at 26.1° and 43.3° (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Data 3)34,35. However, the characteristic diffraction peaks of PVDF at 18.4°, 20.1°, 26.6°, and 38.6°, observed in the PVDF XRD pattern, were absent in the CCM-PVDF pattern36. The absence of PVDF crystallization at the interface was confirmed by DSC (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Data 3). The melting peak of PVDF at 163 °C, present in the PVDF DSC curve, was absent in the CCM-PVDF DSC curve, indicating no PVDF crystallization at the cathode coating layer/CCM interface. This eliminated stress generated by partial PVDF crystallization at the electrode/current collector interface during drying, facilitating good electrode-current collector contac37.

Benefiting from its strong interaction with the electrode, CCM exhibited remarkable cycling stability. Charge-discharge tests of CCM-LFP | |Li and Al-LFP | |Li over 500 cycles were performed at 3 C. The initial discharge capacity of CCM-LFP | |Li (103.46 mAh·g−1) was higher than that of Al-LFP | |Li (70.56 mAh·g−1) (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Data 3). Notably, CCM-LFP | |Li retained a higher discharge capacity of 102.84 mAh·g−1 (capacity retention: 99.40%) after 500 cycles, while Al-LFP | |Li delivered only 3.57 mAh·g−1. These findings demonstrated the excellent cyclability of CCM-LFP, outperforming previously reported LFP-based cathodes (Fig. 4e). After 500 cycles, the impedance of CCM-LFP | |Li increased from 129 Ω to 312 Ω, whereas the impedance of Al-LFP | |Li increased from 380 Ω to 1364 Ω (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Data 3). Post-mortem analysis revealed no electrode material shedding on the CCM-LFP surface, while severe shedding was observed on the Al-LFP surface (Fig. 4g). Additionally, no significant changes were noted in the C1s spectra of CCM-LFP before and after cycling, indicating CCM’s maintained structural stability after 500 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 14, Supplementary Data 5). Ultrasonic stripping experiments further demonstrated stronger adhesion between CCM and the electrode. After 10 sec of sonication, the electrode completely detached from the Al current collector but remained tightly adhered to CCM (Fig. 4h, i, Supplementary Movie 3). This was attributed to enhanced mechanical interlocking between the rough CCM surface and the electrode, providing firmer adhesion38.

Full-Cell Performance

CCM’s lightweight (1.23 mg·cm−2) and low-cost nature offer significant advantages for constructing high energy density LIBs. Commonly used commercial Cu and Al foils weigh 7.50 mg·cm−2 and 4.20 mg·cm−2, respectively, accounting for approximately 23.51% of the total battery mass (based on a full battery with an areal capacity of about 2 mAh·cm−2)39. Replacing aluminum and copper foils with CCM reduces the current collector mass ratio in the battery to 6.12% (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, CCM-based full batteries exhibited higher charge capacities due to reduced interfacial resistance (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Data 4).

a Schematic illustration of weight comparisons of CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM and Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu. Rate performance (b) and GCD curves (c) at 0.1 C of CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM and Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu (The mass loading of LFP is 16.80 mg·cm−2 and 16.78 mg·cm−2, respectively). d Cycling performance of CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM and Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu at 1 C.

These improvements increased the battery’s gravimetric energy density (CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM) to 171 Wh·kg−1, a 41.32% increase compared to the Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu (Table 1) configuration at 121 Wh·kg−1 (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Data). Additionally, the CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM battery demonstrated superior cycle stability, achieving a discharge capacity of 98.97 mAh·g−1 and a capacity retention rate of 92.91% after 100 cycles at 1 C (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Data 4). Under the same conditions, the Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu battery exhibited a discharge capacity of only 77.63 mAh·g−1 after 100 cycles, representing approximately 72.07% of its initial discharge capacity.

Moreover, a techno-economic analysis of CCM (Supplementary Table 1) revealed a cost of 12252.2 USD per ton. Replacing aluminum and copper foils with CCM as cathode and anode current collectors reduces current collector costs by 50.36% (Supplementary Discussion 1). SEM cross-sectional images of CCM-LFP (Supplementary Fig. 15) indicated an actual CCM thickness of only 13.60 µm. Although slightly thicker than commercial current collectors, the weight reduction achieved by using CCM outweighs the minor volume increase.

Conclusions

In summary, CCM was developed to replace commercial current collectors, serving simultaneously as both cathode and anode materials, to enhance LIBs gravimetric energy density. By replacing commercial collectors with lightweight (1.23 mg·cm−2) and cost-effective CCM, the battery’s current collector proportion is reduced to 6.23%. This replacement results in a 41.32% increase in overall gravimetric energy density and an approximate 50.36% reduction in current collector costs. The alkali/urea solvent system employed is a “green” cellulose solvent, known for its relative non-toxicity, low cost, and energy efficiency. Industrial production technologies for cellulose products using regenerated cellulose technology are well-established. Consequently, CCM, derived from regenerated cellulose technology in an alkali/urea solvent system, is suitable for industrial-scale current collector production.

Experimental section

Materials

Carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs, >90% purity, 1.6% -COOH content) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cotton linter pulp (>95% α-cellulose purity) was provided by Hubei Chemical Fiber Co., Ltd. (Hubei, China). Sodium lignosulfonate (SL, 45-50% content), LiFePO4 (>98% purity), and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF, average Mw~534,000, powder) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carbon black (CB) and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other chemical reagents, of analytical grade, were also purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

Preparation of CCM and nonporous CCM (NP-CCM)

A mass ratio of sodium lignosulfonate (SL):MWCNTs:NaOH:urea:H2O of 1:2.5:7:12:81 was used to dissolve cellulose23. The mixed solution was pre-cooled to −12.7 °C, and cotton linter pulp was then added and vigorously stirred for 10 min to facilitate dissolution. During this process, the cellulose chains formed a stable urea hydrate inclusion complex, enhancing cellulose dispersibility40. After standing for 15 min, the mixed solution, containing 2.5 wt% cellulose, was poured onto a glass plate using a glass rod wrapped with copper wires at both ends. Once evenly spread, the glass plate was immediately immersed in a 5 wt% H2SO4 aqueous solution until the gel automatically detached. The resulting gel was thoroughly washed with deionized water, and CCM was produced via freeze-drying.

To obtain a nonporous CCM (NP-CCM), the cleaned gel was spread flat on an acrylic plate, air-dried, and then oven-dried at 70 °C for 24 h.

Preparation of CCM-LFP, Al-LFP and CCM-Gr, Cu-Gr

The LFP-based cathode slurry was prepared by mixing LFP, CB, and PVDF in an NMP solution at a mass ratio of 8:1:1. This slurry was then applied to both CCM and commercial aluminum foil. Similarly, a graphite slurry (graphite:CB:PVDF = 8:1:1) was applied to CCM and commercial copper foil. The coated materials were dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h. After drying, the materials were shaped into circular sheets with an 8 mm diameter and labeled CCM-LFP, Al-LFP, CCM-Gr, and Cu-Gr.

Characterization

Observations of the morphology and structure of the cellulose membrane (CM) and CCM were conducted using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, GeminiSEM 300, ZEISS), accompanied by element concentration analysis through EDS mapping. Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP, MicroActive AutoPore V 9600, ASTM D4404-18) was employed to analyze the detailed gradient pore size structures of CCM. Analyses of the chemical structure and surface chemical state of the samples were performed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB XI + ).

To investigate the interaction between CCM and PVDF, the melting and recrystallization patterns of CCM, PVDF, and their compounds were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Smart LAB-SE with Cu Kα radiation) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The mechanical properties of both CCM and CM were measured with a universal tensile tester (XQ-1, Shanghai Textile University, China). The electrolyte uptake and porosity of the electrodes were calculated as follows:41:

w0 was the pristine weight of electrodes. After being immersed in the electrolyte for 1 h, the electrodes were extracted and weighed (w1) again.

Electrochemical characterization

Half cells (CCM-LFP | |Li, Al-LFP | |Li, and CCM-Gr | |Li) were assembled in CR 2032 cells to evaluate their electrochemical performance. In these cells, CCM-LFP, Al-LFP, and CCM-Gr were used as cathodes, with lithium foil and Celgard 2500 serving as anodes and separators, respectively. Full cells (CCM-LFP | |Gr-CCM and Al-LFP | |Gr-Cu) were also assembled in CR 2032 cells to assess their electrochemical performance. Each cell contained an electrolyte of 2.00 mg·mAh−1 comprising 1 M LiPF6 in a 50% (by volume) EC/50% (by volume) DEC solvent solution. The cells were cycled at 25 °C across various charge/discharge current densities within a voltage range of 2.5–4.0 V, using a Coin Cell All-in-One Testing System (MIHW-200-160CH, NEWARE, China). Cyclic Voltammetry (CV, scanning rates from 0.05 to 1 mV·s−1) and electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS, frequency range from 106 Hz to 0.01 Hz, amplitude of 5 mV) were performed on an electrochemical station (CHI660, Chenhua, China).

The electrical conductivity was measured using an LCR meter TH2830/ST2742B (China) and a standard four-probe tester ST2742B (China). The galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) was employed to calculate the Li-ion diffusion coefficients in cathode materials using the following equation:

Where mB and MB indicated the mass and molar mass of the active material, respectively. VM was the molar volume of the electrode materials, S was the geometric area of the electrode and \(\tau\) was the time duration of the pulse.

Data availability

All source data generated and analyzed during the study are included within the submitted article and its supplementary information. Source Data are provided with this paper.

References

Tarascon, J. M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Mauler, L., Duffner, F., Zeier, W. G. & Leker, J. Battery cost forecasting: a review of methods and results with an outlook to 2050. Energ. Environ. Sci. 14, 4712–4739 (2021).

Ye, Y. et al. Ultralight and fire-extinguishing current collectors for high-energy and high-safety lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 786–793 (2020).

Feng, Y. et al. Metalized Polymer Current Collector for High-Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries with Extreme Fast-Charging Capability. Energ. Environ. Mater. 2025, n/a (n/a), e12878.

Choudhury, R., Wild, J. & Yang, Y. Engineering current collectors for batteries with high specific energy. Joule 5, 1301–1305 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Song, Y., Zhang, B., Wang, L. & He, X. Metallized Plastic Foils: A Promising Solution for High-Energy Lithium-Ion Battery Current Collectors. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2370146 (2023).

Woo, S.-G. et al. Galvanically Replaced, Single-Bodied Lithium-Ion Battery Fabric Electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908633 (2020).

Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose: a new ageless bionanomaterial. Mater. Today 16, 220–227 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Why Cellulose-Based Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices? Adv. Mater. 33, 2000892 (2021).

Kuang, Y. et al. Conductive Cellulose Nanofiber Enabled Thick Electrode for Compact and Flexible Energy Storage Devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802398 (2018).

Qian, J. et al. Toward stretchable batteries: 3D-printed deformable electrodes and separator enabled by nanocellulose. Mater. Today 54, 18–26 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Nanocellulose Structured Paper-Based Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 4341–4350 (2018).

He, H. et al. 3D printing of fast kinetics reconciled ultra-thick cathodes for high areal energy density aqueous Li-Zn hybrid battery. Sci. Bull. 67, 1253–1263 (2022).

Luo, W. et al. Highly Conductive, Light Weight, Robust, Corrosion-Resistant, Scalable, All-Fiber Based Current Collectors for Aqueous Acidic Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702615 (2018).

Park, S. et al. 3D current collector based on cellulose-carbon nanotube nanocomposites for all-solid-state batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 25530–25544 (2024).

Skogberg, A. et al. Self-assembled cellulose nanofiber-carbon nanotube nanocomposite films with anisotropic conductivity. Nanoscale 14, 448–463 (2022).

Yu, M. et al. Freestanding and Sandwich-Structured Electrode Material with High Areal Mass Loading for Long-Life Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602347 (2017).

Yamakawa, A. et al. Nanostructure and physical properties of cellulose nanofiber-carbon nanotube composite films. Carbohyd Polym. 171, 129–135 (2017).

Tu, H., Zhu, M., Duan, B. & Zhang, L. Recent Progress in High-Strength and Robust Regenerated Cellulose Materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2000682 (2021).

Kargarzadeh, H. et al. Advances in cellulose nanomaterials. Cellulose 25, 2151–2189 (2018).

He, X., Xu, X., Bo, G. & Yan, Y. Studies on the effects of different multiwalled carbon nanotube functionalization techniques on the properties of bio-based hybrid non-isocyanate polyurethane. Rsc Adv. 10, 2180–2190 (2020).

Ling, X.-L., Wei, Y.-Z., Zou, L.-M. & Xu, S. Preparation and characterization of hydroxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochemical Eng. Asp. 421, 9–15 (2013).

Luo, X. et al. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Water by Magnetic Cellulose-Based Beads with Embedded Chemically Modified Magnetite Nanoparticles and Activated Carbon. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 4, 3960–3969 (2016).

Gao, J., Wang, J., Xu, Q., Wu, S. & Chen, Y. Regenerated cellulose strongly adhered by a supramolecular adhesive onto the PVDF membrane for a highly efficient oil/water separation. Green. Chem. 23, 5633–5646 (2021).

Choi, S., Kim, J., Eom, M., Meng, X. & Shin, D. Application of a carbon nanotube (CNT) sheet as a current collector for all-solid-state lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 299, 70–75 (2015).

Sharma, J. et al. Aligned carbon fibers-carbon nanotube-polymer-based composite as lithium-ion battery current collector. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 318, 118015 (2023).

Fang, Y., Zhang, Z., Liu, S., Pei, Y. & Luo, X. Polydopamine-modified cellulose-based composite separator for inhibiting dendritic growth of lithium metal batteries. Electrochim. Acta 475, 143661 (2024).

Cermak, M., Perez, N., Collins, M. & Bahrami, M. Material properties and structure of natural graphite sheet. Sci. Rep. 10, 18672 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Graphite-Embedded Lithium Iron Phosphate for High-Power-Energy Cathodes. Nano Lett. 21, 2572–2579 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Direct regeneration of spent graphite anode material via a simple thermal treatment method. Sustain. Energy Fuels 8, 1438–1447 (2024).

Cao, M. et al. Feasibility of Prelithiation in LiFePO4. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2210032 (2023).

Aqeel, S. M. et al. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/polyacrylonitrile (PAN)/carbon nanotube nanocomposites for energy storage and conversion. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 1, 185–192 (2018).

Sundarayya, Y., Vijeth, H., Nagaraju, D., Kumara Swamy, K. C. & Sunandana, C. S. Isovalent substitution of vanadium in LiFePO4: Evolution of monoclinic α-Li3Fe2(PO4)3 phase. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 150, 110530 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Hydrophilic PVDF membrane with versatile surface functions fabricated via cellulose molecular coating. J. Membr. Sci. 640, 119817 (2021).

Culica, M. E. et al. Cellulose surface modification for improved attachment of carbon nanotubes. Cellulose 29, 6057–6076 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Flexible cellulose/PVDF composite films with improved breakdown strength and energy density for dielectric capacitors. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 164, 107325 (2023).

Zheng, M., Wang, Y., Reeve, J., Souzandeh, H. & Zhong, W.-H. A Polymer-Alloy Binder for Structures-Properties Control of Battery Electrodes. Energy Storage Mater. 14, 149–158 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Significance of Current Collectors for High Performance Conventional Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305515 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Lithium Dendrite Deflection at Mixed Ionic–Electronic Conducting Interlayers in Solid Electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2403179 (2025).

Luo, X. & Zhang, L. New solvents and functional materials prepared from cellulose solutions in alkali/urea aqueous system. Food Res Int 52, 387–400 (2013).

Jiang, Y., Ding, Y., Zhang, P., Li, F. & Yang, Z. Temperature-dependent on/off PVP@TiO2 separator for safe Li-storage. J. Membr. Sci. 565, 33–41 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Polymer Molecular Engineering Enables Rapid Electron/Ion Transport in Ultra-Thick Electrode for High-Energy-Density Flexible Lithium-Ion Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100434 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. 3D-Printed All-Fiber Li-Ion Battery toward Wearable Energy Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1703140 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Spider Silk-Inspired Binder Design for Flexible Lithium-Ion Battery with High Durability. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303165 (2023).

Bao, Y., Liu, Y., Kuang, Y., Fang, D. & Li, T. 3D-printed highly deformable electrodes for flexible lithium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 33, 55–61 (2020).

Meng, Q. et al. DNA Helix Structure Inspired Flexible Lithium-Ion Batteries with High Spiral Deformability and Long-Lived Cyclic Stability. Nano Lett. 22, 5553–5560 (2022).

Nam, D. et al. Aluminum textile-based binder-free nanostructured battery cathodes using a layer-by-layer assembly of metal/metal oxide nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 011405 (2021).

Ren, H. et al. Manufacturing Water-Based Low-Tortuosity Electrodes for Fast-Charge through Pattern Integrated Stamping. Energy Environ. Mater. 6, e12584 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51773159) and the Key Research and Development Project of Hubei Province (2024BAB109, 2024BEB002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chenchen Li: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft. Zhenwei Yang: investigation, validation, writing—review and editing. Xiaogang Luo: funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Yang, Z. & Luo, X. Cellulose composite membranes induced by multiple hydrogen bonds as lightweight current collectors for high-performance batteries. Commun Mater 6, 79 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00802-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00802-6