Abstract

High ionic conductivity at reduced temperatures may allow electrochemical cell applications to be efficiently scaled up. Herein, we introduce an approach that exploits electrode-electrode synergy and in situ structural transformation to increase the ionic conductivity of an electrolyte within the electrochemical cell. This transformation is based on the formation of a Li2TiO3-Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte via the combination of a TiO2 semiconductor precursor, polystyrene spheres as the soft skeleton, and the lithium-based electrode LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2. The unique surface and interface of the heterostructure electrolyte enable the formation of long-range ion transport channels that lower electrode impedance, resulting in a superior ionic conductivity of 0.23 S cm−1 at 550 °C and a high-power density of 1239 mW cm−2. Our general method to form superionic electrolytes shows potential in fuel cell technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Both climate change mitigation and energy security increasingly rely on the use of clean fuels and solid-state electrochemical cells owing to their high energy conversion efficiency1,2. The efficiency of energy storage and conversion in an electrochemical cell is strongly influenced by its ionic conductivity. However, the commercial application of such cells is limited by the required high operating temperature conditions (>700 °C), high cost, slow startup and shutdown cycles, and technical complexity of conventional electrolytes. Similarly, ion migration is typically inhibited at low temperatures (<400 °C), resulting in poor device performance. Achieving high ionic conductivity at moderate temperatures (400–700 °C) is therefore crucial to improving the energy density and practical application of electrochemical devices3. Concurrently, the componentry of the cell must be based on environmentally sustainable and readily available materials to facilitate the widespread commercialization of electrochemical cells4.

TiO2-based electrolytes have attracted attention owing to their earth abundance (>700 million metric tons in reserves) and structural flexibility (polymorphic transitions enabling defect engineering); however, their practical implementation is limited by their poor ion transport at medium temperatures. The crystal structure of TiO2-based electrolytes impedes the migration of oxygen ions, resulting in poor oxygen ion conductivity that fails to satisfy the ion transport requirements of fuel cells5.

Lithium-based electrodes have high redox catalytic efficiency and play an important role in electrochemical cell performance <600 °C; however, LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (LNCA) electrodes typically decompose during fuel cell operation. The by-products of this degradation solidify within the porous electrode and at the electrode/electrolyte interface6, thereby inhibiting fuel gas diffusion/dissociation in the porous electrode and hindering ion transport from the electrode to the electrolyte, ultimately reducing fuel cell performance7,8.

Herein, we introduce a innovative synergistic optimization strategy that employs controlled interfacial reactions to repurpose electrode degradation by-products as electrolyte modifiers. The optimization of the porous structure aligns with our dual-functional design approach that enhances ionic conductivity and reduces electrode impedance by reducing the blockage at triple-phase boundaries. The electrode-electrolyte chemical interplay between the electrode and electrolyte transforms the porous membrane structure into a heterostructure electrolyte in situ. Such a transformation is unprecedented in TiO2-based electrolyte systems9,10.

The basis of this method lies in establishing long-range ion transport channels using unique interfaces and surfaces, thereby improving ionic conductivity. The introduction of Li+ ions from the LNCA electrode into the porous TiO2 semiconductor membranes formed Li2TiO3, which is then encapsulated by carbonate generated in situ, thereby forming a self-assembled Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte. Assessment of the resulting electrochemical cell reveals that the incorporation of this heterostructure electrolyte exhibits an exceptional power density of 1239 mW cm−2 at 550 °C, owing to the exceptional superionic conduction of the electrolyte. Accordingly, we herein introduce a Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte that enables superionic conduction through electrode-electrolyte synergy and in situ structural transformation of electrochemical cells.

Results and discussion

Structure design and characterization of porous membranes

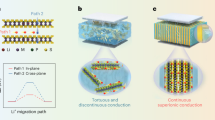

An electrochemical cell incorporating a porous membrane and an LNCA electrode was assembled. The porous structure uses polystyrene spheres (PSs) as the soft skeleton and is formed from a TiO2 precursor by combustion at the test temperature (Fig. 1a). Characterization of the morphologies of PS and TiO2 reveals homogeneously dispersed, uniformly sized nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. 1). Because different concentrations of PS exhibit varying pore numbers and volumes, which significantly affect electrode-electrolyte synergy and oxygen vacancy concentration, we focused on the regulation and control of the PS ratio to determine the optimal porous structure.

a Schematic showing the general fabrication of the porous membrane, electrochemical cell, and in situ structural transformation from a porous TiO2 membrane to the Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte; b XRD patterns of porous membranes obtained via combustion of various TiO2-X% (PS) precursors at 550 °C for 0.5 h in an electrothermal furnace; c TG curves of various TiO2-X% (PS) precursors; d Raman spectra of porous membranes with various TiO2-X% (PS) precursor ratios.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the TiO2-X% (PS) (X = 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) porous membranes revealed the presence of the same anatase phase regardless of the PS ratio (Fig. 1b). Based on Scheller estimates, the (101) peak corresponds to an average particle size of 20 nm. The thermogravimetry (TG) curves of the TiO2-X% (PS) precursors exhibited similar trends, including a two-stage mass loss during the combustion process (Fig. 1c). An initial mass loss between 25 and 300 °C was attributed to the elimination of physically adsorbed water on the surface of the precursors and dehydration of hydrated TiO2. Further mass loss in the composite precursors occurred between 300 and 500 °C owing to the combustion of the PS. These results indicate that the PS can completely combust and that, regardless of the PS ratio, porous membranes are formed at 550 °C (as was the case for the test temperature for the electrochemical cell). Moreover, the Raman spectra of the TiO2-X% (PS) porous membranes show prominent peaks at 144 cm−1 (Eg), likely indicative of the O-Ti-O bending mode, whereas the other peaks were characteristic of anatase-type TiO2 crystals (Fig. 1d)11,12. The porous membrane was characterized by Raman spectroscopy after the thermal decomposition/combustion of the PS template at 550 °C; thus, the absence of a carbon peak in the Raman spectrum further confirms the complete removal of PS.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) demonstrated that porous membranes were formed by the in situ stacking of nano-TiO2 following removal of the PS template (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig 2). The porous TiO2–6% PS membrane exhibited the most homogeneous pore distribution among all membranes, avoiding both insufficient porosity (low surface area) and localized structural collapse (instability). This optimized structure aligns with our dual-functional design strategy, with a uniform structure that facilitates the efficient transport of electrochemical by-products from the electrode to the electrolyte, thereby reducing interfacial resistance (electrode-electrolyte synergy). Additionally, the porous architecture improves ionic conductivity by promoting the in situ formation of electrochemical heterointerfaces.

The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) Ti 2p and O 1 s fine spectra of the porous TiO2-X% (PS) membranes are shown in Supplementary Fig 3. Results reveal the partial reduction of Ti4+ to Ti3+ species during the in situ formation. The presence of Ti3+ introduces electronic conductivity in the electrolyte layer through Ti3+-O-Ti4+ bridging configurations, enabling small polaron hopping between adjacent Ti3+ and Ti4+ sites. Oxygen vacancies are critical for ensuring efficient ion migration and transport and improving electrochemical performance. Among the various membranes fabricated in this study, the TiO2–6% (PS) porous membrane exhibits the highest oxygen vacancy concentration, as evidenced by the high relative area of the peak corresponding to oxygen vacancies. This superior defect engineering originates from synergistic factors during the thermal decomposition process. The SEM images show that the porous TiO2–6% (PS) membrane exhibits an optimal specific surface area owing to its uniform and stable porous structure, which provides abundant active sites for the generation of oxygen vacancies. Similarly, moderate decomposition of the PS template is known to generate residual carbon, creating a localized weakly reductive atmosphere that promotes oxygen desorption from TiO2 surfaces, thereby significantly increasing the density of oxygen vacancies13,14. Comprehensive analysis confirmed that the porous TiO2–6% (PS) membrane exhibits the optimal composition for electrochemical characterizations, with the dense, non-porous TiO2–0% PS membrane serving as the control.

The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) image of the porous TiO2–6% (PS) membrane shows a well-defined interplanar distance (Fig. 2c). Lattice fringes corresponding to the (200), (004), and (101) lattice planes of the porous TiO2–6% (PS) membrane were observed at 0.187, 0.231, and 0.358 nm, respectively. These values are very similar to those of the porous TiO2–0% (PS) membrane (Fig. 2d), the (200), (004), and (101) planes of which show lattice fringes at 0.189, 0.236, and 0.353 nm, respectively. The selected area electron diffraction patterns of the porous TiO2–6% (PS) and TiO2–0% (PS) membranes obtained from calibrated polycrystalline TiO2 show an approximately circular diffraction spot (Fig. 2e, f)15. These crystal planes are consistent with the fast Fourier transform (FFT), inverse FFT (IFFT), and IFFT line profile of the three crystal planes (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), indicating that the porous structure of the membrane does not affect the structural properties of TiO2.

The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms exhibit type IV behavior (Fig. 2g, h) and were similar to the H4 hysteresis curves of both samples. The maximum quantities adsorbed by the porous TiO2–6% (PS) and TiO2–0% (PS) membranes were 181.3 cm3 g−1 and 125.7 cm3 g−1, respectively, and the corresponding Brunauer-Emmett-Teller-specific surface areas were 67.31 m2 g−1 and 55.41 m2 g−1, respectively. These values illustrate the influence of the precursor ratio on the distinctive porous structure of the membranes. The precursor ratios also influence the pore volume (Fig. 2i, j) and surface area (Fig. 2k, l) of the porous membranes, with those of TiO2–6% (PS) being higher than those of TiO2–0% (PS) precursor ratios at pore widths of 50–100 nm. This provided further evidence of a porous membrane with a pore width of 100 nm (Fig. 2a, b), which was formed by stacking TiO2 particles with an average particle size of ~20 nm (Fig. 2a, b inset).

Electrochemical performance of TiO2-X% (PS) electrochemical cells

The polarization (I–V) and power density (I–P) curves of the various electrochemical cells measured at 550 °C are shown in Fig. 3a. All porous structures with various PS ratios exhibited high electrochemical performance (850–1239 mW cm−2) (Fig. 3b) superior to that of the TiO2–0% (PS) electrochemical cell (575 mW cm−2). The optimal porous structure of TiO2–6% (PS) afforded the highest performing electrochemical cell with a power density of 1239 mW cm−2. These electrochemical performances significantly surpass those of reported electrochemical cells under identical conditions, including TiO2-based cells derived from a dense TiO2 thin film and TiO2-SrTiO3@TiO2, which have power densities of 364 mW cm−2 and 799.7 mW cm−2, respectively9,10.

a I–V–P curves of the electrochemical cells at 550 °C; b maximum power density; c open-circuit voltage; d EIS curves of the electrochemical cells at 550 °C; e I–V–P curves of the TiO2-6% (PS) electrochemical cells at various temperatures; f Nyquist plots and fitted EIS curves of the electrochemical cells at various temperatures; g conductivities estimated from the EIS and I–V curves of the TiO2-6% (PS) electrochemical cell; h conductivities estimated from the EIS and I–V curves of the TiO2-0% (PS) electrochemical cell; i Ea as a function of 1000/T obtained from the conductivity curve at 475–550 °C.

The open-circuit voltages (OCVs) for all of the electrochemical cells exceeded 1 V (Fig. 3c), indicating that no electronic or gas leakage occurred in any of the electrochemical cells16,17. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of the electrochemical cells operated at 550 °C (Fig. 3d) via a standard equivalent circuit showed similar trends regardless of the PS ratio18. The TiO2–6% (PS) electrochemical cell exhibited both the highest power density and lowest resistance at 550 °C.

As can be seen in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig 6a–e, all of the electrochemical cells exhibited good electrochemical performance with decreasing operating temperatures. The TiO2–6% (PS) electrochemical cell achieved power densities of 1058, 880, and 725 mW cm−2 at 525, 500, and 475 °C, respectively, far superior to those of the other electrochemical cells at the same temperatures (Supplementary Table 1). This further confirms the key role of structural design, including electrode-electrolyte synergy and in situ structural transformation, in ensuring the performance of electrochemical cells. The cell performance was improved by lower electrode impedance and higher ionic conductivity; thus, we further characterized this cell using Nyquist plots and fitted EIS values (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig 6f–j). The resistance increased with decreasing temperature, with a corresponding decline in cell performance. These results demonstrate that lower temperatures inhibit both ion transport within the electrolyte and the catalytic activity of the electrode.

The TiO2–6% (PS) and TiO2–0% (PS) electrochemical cells were further analyzed to investigate ionic transport at the surface and interfaces of the Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte. The total electrical conductivities (σt) and ionic conductivities (σi) shown in Fig. 3g, h were calculated from the I–V and EIS curves, respectively19. The σt and σi values of the TiO2–6% (PS) electrochemical cell (0.369 S cm−1 and 0.233 S cm−1, respectively), which were higher than those of the TiO2–0% (PS) electrochemical cell (0.198 S cm−1 and 0.131 S cm−1, respectively) at 550 °C, indicating that superionic conduction promoted the formation of ion and electron transport pathways in the heterostructure. The activation energy (Ea) of the ionic transport was calculated from the slopes of the Arrhenius plots20. The Ea of the TiO2–6% (PS) electrochemical cell (~0.47 eV) was significantly lower than that of the TiO2–0% (PS) electrochemical cell (1.05 eV) (Fig. 3i), demonstrating that in situ structural transformation reduces the energy barrier for charge transfer between the electrolyte and electrode, thereby significantly reducing the activation energy.

Ion transport of Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte

High-angle annular dark-field images of the TiO2–6% (PS) heterostructure electrolyte Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 obtained from a random region of the sample after testing the cell revealed a lattice-disordered layer in the electrolyte with a thickness of ~25 nm at the edges (yellow dashed lines in Fig. 4a). TEM images with element mapping revealed a core layer consisting of Ti and O (Fig. 4b) encapsulated in a shell layer consisting of C (Fig. 4c). EDS maps confirmed the distribution of these elements (Supplementary Fig. 7). SEM images of the Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte suggested that the particle size increased from 20 nm to 55 nm during testing (Fig. 4d). These findings further confirm the core-shell structure and phase composition of the heterostructure electrolyte, providing evidence for its successful fabrication. The heterostructure and phase composition of the electrolyte were further confirmed by the XRD patterns of the TiO2–6% (PS) electrochemical cell acquired after testing for various periods. After testing for 1 h, TiO2 (PDF# 21–1272), Li2TiO3 (PDF# 75–1602), Li2CO3 (PDF# 83–1454), and Ni (PDF# 04–0850) phases were observed (Fig. 4e). After testing for 2 h, Li2TiO3 and Li2CO3 were detected (Fig. 4f). After further testing, Li2TiO3 and Ni phases were observed (Fig. 4g). These results further confirm the in situ structural transformation from a TiO2–6% (PS) porous membrane to a Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte during electrochemical testing.

a–c TEM images and corresponding EDS maps of the Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte (inset: corresponding line scan); d SEM image showing the particle size of the electrolyte; e–g XRD patterns showing structural phase transformation after various testing periods; h Schematic of superionic conduction in Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte in the electrochemical cell.

A schematic of superionic conduction via in situ structural transformation of the heterostructure electrolyte electrochemical cell is provided in Fig. 4h, in which the bonds between the nanoparticles (Li2TiO3) and the surface carbonate (Li2CO3) differ from those in traditional fuel cells. The diffusion of Li+ ions from the LNCA electrode within the porous membranes along the pore wall, where they encounter stacked TiO2. The migrating Li+ ions then react with TiO2, resulting in the in situ formation of Li2TiO3. The surface of the Li2TiO3 phase is encapsulated by a carbonate Li2CO3 layer generated in situ, thereby forming the heterostructure electrolyte Li2TiO3–Li2CO3. The ratio of Ti to O detected in the line scan (Fig. 4b) deviated from the theoretically expected value of 2:1, demonstrating that the interfacial heterojunction layer between the Li2TiO3 and Li2CO3 electrolytes contained defective oxygen (oxygen vacancies). These oxygen vacancies provide additional ionic transport pathways and significantly reduce the resistance arising from grain boundary gaps within the electrolyte. The increased rate of ion migration in the anode and cathode improves the conductivity of the fuel cell.

The advantages of introducing a porous structure are improved ionic conductivity and reduced electrode impedance. In this way, dynamic Li2TiO3/Li2CO3 heterointerfaces establish long-range ion transport pathways, with the high oxygen vacancy concentrations enhancing ionic conduction capabilities. Concurrently, the rapid dissipation of reaction by-products alleviates interfacial blockage and improves electrode-electrolyte kinetics. These coupled effects collectively balance interfacial charge transfer kinetics and ion mobility, ultimately elevating the electrochemical performance.

In addition, metallic Ni was formed via the reduction of H2 on the electrode side of LNCA, which is similar to a previously reported phenomenon21,22. A well-defined Schottky contact is formed between the metallic Ni and the semiconductor heterostructure electrolyte (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3), inducing significant band bending at the interface owing to the work function mismatch, resulting in an internal electric field with a Schottky barrier (Fig. 4h). The resulting Schottky barrier effectively prevents electron migration across the electrode/electrolyte interface23,24.

Raman spectroscopy confirmed the formation of a molten carbonate salt (Li2CO3) in the heterostructure electrolyte (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3). The Raman spectrum of the heterostructure electrolyte (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3) after testing was similar to that obtained before testing (Fig. 5a), including the primary peaks at 144 cm−1 (Eg), 397 cm−1 (B1g), 515 cm−1 (A1g + B1g), and 640 cm−1 (Eg). After testing, all of the peaks broadened or disappeared in the wavelength range of 300–700 cm−1, primarily owing to the cleavage of the Ti-O bond. The peak at 1089.2 cm−1, corresponding to CO32− 25,26, is indicative of the introduction of Li salts into the porous electrolyte membrane from the LNCA electrodes. The Li2TiO3 formed by Li+ ions embedded in TiO2 further verified that the heterostructure electrolyte Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 is composed of Li2TiO3 and Li2CO3.

The precursor composition of the designed electrolyte was TiO2–6% (PS) before testing of cell performance and was in situ transformed into the heterostructure (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3) electrolyte following testing. a Raman spectra; b XPS full-spectrum; c Ti 2p; d O 1 s; e Li 1 s; (fine spectra for before and after testing the cell performance). f The electronic features of VB maximums and band gaps for the heterostructure electrolyte.

The full XPS spectrum of the heterostructure electrolyte exhibited the Li 1 s peak at 54.8 eV after testing (Fig. 5b), indicating that Li+ ions were embedded in the TiO2 crystal lattice. The changes in valence states and orbitals were semi-quantitatively obtained from the relative peak area of the fitted curves. In the Ti 2p fine spectrum, the ratio of Ti3+/Ti4+ for the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals increased from 0.914 to 1.229 and from 0.941 to 1.112, respectively (Fig. 5c) (Supplementary Table 2). Alterations in the relative peak area ratio were attributed to the embedding of Li+ ions in the crystal lattice of TiO2 to form Li2TiO3, which instigated a redistribution of the electronic configuration upon occupation of certain Ti sites.

The relative peak area ratios (\({{\mbox{V}}}_{O}\,={{\mbox{O}}}_{\beta }/{{\mbox{O}}}_{\alpha }\)) of lattice oxygen (\({{\mbox{O}}}_{\alpha }\)) and defective oxygen (\({{\mbox{O}}}_{\beta }\)) in the O 1 s fine spectrum changed significantly during the evaluation of cell performance (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Table 3). The change in \({{\mbox{V}}}_{O}\) from 0.183 to 0.756 indicated that the amount of \({{\mbox{O}}}_{\beta }\) at the surface and interface increased with the formation of the heterostructure electrolyte, most likely because the surrounding O atoms were readily displaced from their positions in the TiO2 lattice to maintain the charge balance following the embedding of Li+ ions with small ionic radii.

Peaks corresponding to Li2TiO3 (54.8 eV) and Li2CO3 (55.5 eV) were observed in the fine spectra of the Li 1 s orbitals after testing (Fig. 5e), illustrating that lithium salts are continuously produced by reactions in the testing atmosphere of the fuel cells. Notably, the surface of Li2TiO3 is encapsulated by a continuous Li2CO3 layer, which physically isolates adjacent Li2TiO3 grains. Although partial reduction of Ti3+ may result in electronic conduction, the molten Li2CO3 exhibits negligible electronic conductivity in the electrolyte layer, thereby disrupting any potential electronic percolation pathways and effectively suppressing electronic leakage.

The changes in the electronic features of the electrolyte that occur during the evaluation of cell performance were further examined using ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 8). The bandgap decreased from 3.18 eV to 2.84 eV during electrochemical testing owing to the alteration of the electronic distribution (Fig. 5f). The conduction band of the heterostructure electrolyte (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3) electrolyte was −4.25 eV after testing; thus, the heterostructure acted as an electron barrier because its energy level was higher than that of the H2/H+ redox potential (−4.5 eV, relative to vacuum energy), thereby inhibiting electron transfer into the electrolyte. Application of this method ensured the excellent electrochemical performance of the cell, including a high OCV.

OCV stability is essential to the efficiency and long-term reliability of electrochemical cells. The OCV stability of the optimized electrochemical cells was therefore evaluated in a fuel atmosphere to achieve more efficient and stable electrochemical energy conversion (Supplementary Fig. 9). The OCV of the TiO2-6% (PS) electrochemical cell declined from 1.10 V to 0.95 V within 88 min and to 0.90 V within 396 min. The instability data is primarily governed by the dynamic interfacial interactions between the porous TiO2 membrane electrolyte and lithium-based LNCA electrodes, among other interdependent factors. In particular, the LNCA electrode gradually decomposes during operation, thereby degrading the redox kinetics. Additionally, the heterogeneous reactions in the electrolytes accelerate interface delamination and cause localized fluctuations in electrochemical performance.

The durability of the cell was enhanced by adding a buffer layer (80% LNCA and 20% TiO2), resulting in a reduction in the OCV from 1.14 V to 0.80 V in 1261 min. A second type of electrochemical cell was prepared for comparison by compounding TiO2 with Na2CO3, resulting in a reduction in OCV from 1.12 V to 0.93 V in 431 min. Structural optimization via the addition of the buffer layer, therefore, significantly improved the initial OCV level and stability relative to that of the TiO2-6% (PS) electrochemical cell, which is expected to advance fuel cell technology. This study resolved fundamental challenges in the design of electrolyte materials. Future work will aim to achieve co-optimization of the electrolyte and its corresponding electrodes, systematically addressing the interrelationships among materials, interfaces, and the overall system to provide a more comprehensive theoretical understanding that will enable innovative and technical pathways for enhancing electrochemical cell stability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a high-performance electrochemical cell was developed using a strategy involving electrode-electrolyte synergy and an in situ structural transformation strategy. This innovative electrochemical cell incorporates TiO2 semiconductors with PS as a soft skeleton and a lithium-based LNCA electrode. The migration of Li+ ions from the electrode to the electrolyte and their subsequent reaction with TiO2 forms Li2TiO3, the surface of which is simultaneously encapsulated by amorphous lithium carbonate, thereby forming a heterostructure electrolyte (Li2TiO3–Li2CO3) by in situ structural transformation. The heterostructure ensures that the electrochemical cell is gas-tight, with an OCV of 1.20 V at 550 °C, and forms exceptional surface and interface layers that imbue the cell with a superionic conductivity exceeding that of existing cells. This design provides an electrochemical cell with an extremely high-power density of 1239 mW cm−2. This general method overcomes many of the technical challenges that currently limit electrochemical cell production and is expected to facilitate the development of cells with exceptional performance at moderate temperatures.

Methods

Construction of TiO2 nanoparticles

TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized using a modified hydrothermal procedure. Glacial acetic acid (99%, Aladdin), titanium butoxide (99%, Aladdin), and deionized water were then added, following which a white precipitate immediately formed. The solution was continuously heated and stirred to generate TiO2 precursor colloids before being transferred to a hydrothermal reactor, which was maintained at 220 °C for 12 h to yield anatase TiO2 nanoparticle powder.

Electrode fabrication and electrolyte preparation

Commercial LNCA powder (Tianjin B&M Science Technology Co., Ltd.) and terpineol (95%, Aladdin) were mixed until the desired viscosity was attained. The mixture was then uniformly coated onto one side of a porous Ni-foam and heated at 80 °C for 20 h in an air-dry oven to form the Ni-LNCA electrode.

The TiO2 and PS powders were mixed at various PS ratios (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10%) to afford the TiO2-X%PS precursor. The precursor was combusted in an electrothermal furnace at 550 °C for 0.5 h to form the porous membrane and heterostructure electrolyte, which were analyzed using XRD, TG, Raman spectroscopy, TEM, SEM, XPS, UV, and UPS.

Construction of the electrochemical cell

Sandwich electrochemical cells with a Ni-LNCA/TiO2-X%PS/LNCA-Ni configuration, diameter of ~13 mm, and active area of 0.64 cm2 were constructed using Ni-LNCA as the electrode and TiO2-X%PS as the electrolyte precursor under a load of 250 MPa. Increasing the testing temperature from ambient levels to 550 °C induced a structural transformation of the TiO2-X%PS precursor, forming a Li2TiO3–Li2CO3 heterostructure electrolyte in the presence of H2/air.

Materials characterization

Phase structures were determined using XRD (MDI D/Max 2200, Japan). Mass loss of the designed TiO2-X%PS electrolyte precursor was measured via thermogravimetric analysis (TG, STA 449F5, USA), while morphology structure was determined using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, ZEISS G500, Germany) and HR-TEM (Thermo Fisher Talos F200X, USA). N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were established using a physicochemical adsorption instrument (QUADRASORB SI, USA) to analyze the maximum quantity adsorbed, surface area, and total pore volume. Raman spectra (LabRAM HR Evolution, France) were analyzed for characteristic peaks analysis of the constituent elements. Surface valence distribution was using XPS (Thermo ESCALAB 250XI, USA), with valence band level maxima ascertained through UPS (PHI5000 Versa Probe III, UK) measurements employing an unfiltered HeI (21.22 eV) gas discharge lamp with a total instrumental energy resolution of 100 meV. UV-vis absorption spectra of the bandgap electrons were obtained using a UV 3600 spectrometer (UV-vis, UV-3600i Plus, Japan).

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical cell performance was evaluated using an electronic load instrument (ITECH8511, 120 V/30 A/150 W, China) to record the current, voltage, and power. EIS was performed using an electrochemical workstation (Reference 3000AE, S/N 41150, USA). This analysis was conducted under OCV conditions, with a frequency range of 106–0.1 Hz and a DC signal amplitude of 10 mV.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Jiao, K. et al. Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 595, 361–369 (2021).

Papac, M., Stevanović, V., Zakutayev, A. & O’Hayre, R. Triple ionic-electronic conducting oxides for next-generation electrochemical devices. Nat. Mater. 20, 301–313 (2021).

Bisht, R. S. & Ramanathan, S. Cool proton conductors. Nat. Energy 7, 1124–1125 (2022).

Keller, A. A., Ehrens, A., Zheng, Y. & Nowack, B. Developing trends in nanomaterials and their environmental implications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 834–837 (2023).

Li, D., Wang, X., Mo, X., Tse, E. C. M. & Cui, X. Electronic gap characterization at mesoscopic scale via scanning probe microscopy under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 13, 4648 (2022).

Zhu, B. et al. Semiconductor electrochemistry for clean energy conversion and storage. Electrochem. Energy R. 4, 757–792 (2021).

Lee, C. et al. Grooved electrodes for high-power-density fuel cells. Nat. Energy 8, 685–694 (2023).

Zahiri, B. et al. Revealing the role of the cathode-electrolyte interface on solid-state batteries. Nat. Mater. 20, 1392–1400 (2021).

Dong, W. et al. Semiconductor TiO2 thin film as an electrolyte for fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 16728–16734 (2019).

Du, M., Ji, S., Zhang, P., Tang, Y. & Liu, Y. Enriching nano‐heterointerfaces in proton conducting TiO2‐SrTiO3@TiO2 yolk-shell electrolyte for low‐temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Sci. 11, 2401008 (2024).

Zhang, T. et al. Simultaneously activating molecular oxygen and surface lattice oxygen on Pt/TiO2 for low-temperature CO oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6827 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. High quantum efficiency of hydrogen production from methanol aqueous solution with PtCu-TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 22, 619–626 (2023).

Qin, L., Rui, R., Mao, J., Meng, Q. & Zhang, G. Assembly of MOFs/polymer hydrogel derived Fe3O4-CuO@hollow carbon spheres for photochemical oxidation: Freezing replacement for structural adjustment. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 269, 118754 (2020).

Yao, W. et al. Nitrogen‐doped carbon composites with ordered macropores and hollow walls. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 23922–23927 (2021).

Hao, Z. et al. Oxygen‐deficient blue TiO2 for ultrastable and fast lithium storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903107 (2020).

Chen, D. et al. Constructing a pathway for mixed ion and electron transfer reactions for O2 incorporation in Pr0.1Ce0.9O2-x. Nat. Catal. 3, 116–124 (2020).

Luo, Z. et al. Critical role of acceptor dopants in designing highly stable and compatible proton-conducting electrolytes for reversible solid oxide cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2992–3003 (2022).

Su, Y., Zhong, Z. & Jiao, Z. A novel multi-physics coupled heterogeneous single-cell numerical model for solid oxide fuel cell based on 3D microstructure reconstructions. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2410–2424 (2022).

Xia, C. et al. Shaping triple-conducting semiconductor BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ into an electrolyte for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 1707 (2019).

Yashima, M. et al. High oxide-ion conductivity through the interstitial oxygen site in Ba7Nb4MoO20-based hexagonal perovskite related oxides. Nat. Commun. 12, 556 (2021).

Luo, P. et al. TiO2-induced conversion reaction eliminating Li2CO3 and pores/voids inside garnet electrolyte for lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302299 (2023).

Lee, D. H. et al. Engineering titanium dioxide nanostructures for enhanced lithium-ion storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16676–16684 (2018).

Shen, P. et al. Ultralow contact resistance between semimetal and monolayer semiconductors. Nature 593, 211–217 (2021).

Meng, Y. S., Srinivasan, V. & Xu, K. Designing better electrolytes. Science 378, 1065 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Reconstructed anti-poisoning surface for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction on Cu-incorporated ZnO. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 330, 122665 (2023).

Meng, H. et al. A strong bimetal-support interaction in ethanol steam reforming. Nat. Commun. 14, 3189 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Instrumental Analysis Center at Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology for their help in inspecting test specimens; PhD student Jingjing Yang for insightful discussions throughout the experimental design. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFB1502900); National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants no. 51672208 and 51772080); International Science and Technology Cooperation Projects of Shaanxi Province (2019KWZ-03); Key Program for Nature Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2019JZ−20); Key Science and Technology Innovation Team of Shaanxi Province (2022TD-34).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. and R.W. conceived the project, designed the methodical procedure, and wrote the manuscript together. R.W. synthesized the electrolyte materials, and performed the electrochemical experiments. R.W., B.Z., and S.Y. analyzed the data. R.W., G.Y. and T.Y. characterized the electrolyte materials, and contributed to the preparation of the figures. S.Y. and B.Z. supervised the project, and provided supervisory guidance on the electrochemical cell experiments, data interpretation, and manuscript refinement. Y.L. and S.Y. contributed the laboratory apparatus and experiment sites. B.Z., R.R., and P.D.L. provided comments on the manuscript. R.W., Y.L., R.R., B.Z., P.D.L., and S.Y. revised the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to the discussion, revision, and completion of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Kazuaki Kisu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Yang, G., Yang, T. et al. Superionic conduction electrolyte through in situ structural transformation in electrochemical cell. Commun Mater 6, 233 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00811-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00811-5