Abstract

The energy loss in inductor core is a significant limitation in high-frequency power electronics. For evaluating and optimizing soft magnets, simultaneous imaging of both amplitude and phase of AC stray fields beyond 10 kHz is crucial. Here, we develop an imaging technique for analyzing AC magnetization response using diamond quantum sensors. For frequencies up to 200 kHz, we propose a measurement protocol, Qubit Frequency Track (Qurack), where microwave frequency modulation tracks qubit frequency oscillations. For higher frequencies above MHz, quantum heterodyne (Qdyne) imaging is employed. The soft magnetic CoFeB–SiO2 thin films, developed for high-frequency inductors, exhibit near-zero phase delay up to 2.3 MHz, indicating negligible energy loss. Moreover, the energy loss depends on the anisotropy: when the magnetization is driven along the easy axis, phase delay increases with frequency, signifying higher energy dissipation. These results suggest potential applications in analyzing soft magnets and improving the performance of power electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Improving the energy conversion efficiency of power electronics is essential for realizing a sustainable society1. Wide-bandgap power semiconductor devices, such as GaN and SiC, are instrumental in reducing energy losses and enabling the miniaturization of power electronics systems owing to their large breakdown electric field and capacity for high-frequency operation exceeding 10 kHz. However, at high frequencies, the large energy loss in passive components, such as inductors and cores of magnetic materials, restricts the reduction of the power loss and the miniaturization of power electronics systems. Therefore, it is vital to develop soft magnetic materials with high energy conversion efficiency in the high-frequency range. For that, evaluating the energy loss, understanding the energy loss mechanism, and providing feedback on the findings to material development are critical. The energy loss originates from the hysteresis of the magnet and is measured from the area enclosed by the magnetic flux density–magnetic field (B–H) or magnetization-magnetic field (M–H) characteristics. Therefore, the B–H and M–H characteristics serve as crucial metrics for evaluating soft magnetic materials. Especially, imaging B–H or M–H characteristics allows us to link local nonuniformities and magnetic domains to the hysteresis loss. Magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE) imaging, which is sensitive to surface magnetization, is widely used for imaging M–H characteristics2,3,4. MOKE is used to observe magnetic domain shapes, such as domain-wall motion or the number of domain walls. Here, the energy losses are measured using another method, such as measurement of B using a pick-up coil. To develop high-performance soft magnets, the direct imaging of the energy loss over a wide frequency range from 100 Hz to beyond MHz is critical.

This study focused on the simultaneous imaging of the amplitude and phase of an AC stray field, a promising approach for analyzing energy loss. The amplitude and phase data of the stray field can be translated into to M–H characteristics, where the enclosed area signifies the hysteresis loss. The stray field reflects not only surface magnetization but also the magnetization inside the magnetic material. Moreover, AC imaging at the operating frequencies of power electronics devices is essential because the energy loss in soft magnets is typically frequency dependent5,6,7,8.

In this study, we developed a diamond quantum imager using nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers9,10,11,12,13,14,15 to simultaneously image the amplitude and phase of an AC magnetic field over a wide frequency range from 100 Hz to beyond MHz. We proposed a measurement protocol, qubit frequency track (Qurack), to image the kHz AC field. In this protocol, the oscillation of the qubit frequency is tracked by microwave (MW) frequency modulation. A Qurack can fill the kilohertz frequency range, which has been blank for widefield imaging using NV centers. A quantum heterodyne16,17,18,19,20 protocol with a wide frequency range was applied for the simultaneous imaging of the amplitude and phase of AC magnetic fields in the MHz frequency range.

Utilizing an AC magnetic field imaging system with Qurack and Qdyne, we performed imaging of the AC magnetization response of soft magnetic CoFeB–SiO2 thin films, which have been developed for high-frequency inductors. The CoFeB–SiO2 thin films exhibit strong in-plane uniaxial magnetic anisotropy and excellent AC magnetic properties as an inductor up to GHz frequencies. The hysteresis loss is expected to be low because of their small coercivity along the hard axis, and the eddy current loss is small because of their low electrical conductivity21. When the thin films were subjected to excitation along the hard axis, the AC stray field imaging consistently displayed similar trends across the frequency range from 100 Hz to 2.3 MHz. The amplitude of the AC stray field was concentrated at the edge, which indicated that thin films were magnetically uniform within the field of view (FOV). The phase delay was negligible up to 2.3 MHz, which implied that the energy loss was negligible. When the thin film was driven along the easy axis, the phase delay increased as the frequency increased, indicating an increase in the loss. These findings highlight the effectiveness of diamond quantum sensors for the evaluation of magnetic materials and design of power electronics devices.

Results

Simultaneous imaging of amplitude and phase of AC magnetic field up to the MHz frequency

Simple expansion of DC magnetic field imaging techniques, such as continuous-wave optically detected magnetic resonance (CW-ODMR) and Ramsey, is limited by the camera’s frame rate (see Supplementary Fig. 12 for comparison with expansion of Ramsey). The maximum frame rate of typical quantum optics cameras is a few hundred frames per second, with guaranteed high sensitivity and wide FOV. Thus, we used an alternate protocol that can perform frequency down-conversion, which benefited from quantum mechanics. We developed a AC magnetic field imaging system that can simultaneously image the amplitude and phase over a wide frequency range from 100 Hz to beyond MHz using two protocols for different frequency ranges (Fig. 1a). In this study, we devised a protocol “qubit frequency track (Qurack)” for imaging over a frequency range of up to 200 kHz. For AC magnetic field imaging from several 100 kHz to beyond MHz, the quantum heterodyne (Qdyne) method16 has been demonstrated to be effective. The lower and upper measurable frequency is limited by the spin coherence time T2 and Rabi oscillation, respectively.

a Illustration of the measurement principle and frequency range coverage. Qurack protocol was employed up to 200 kHz, utilizing microwave (MW) frequency modulation. The amplitude and phase of frequency modulation were varied to explore the matching condition. In the MHz range, Qdyne protocol was utilized, where the AC magnetic field was undersampled by MW pulses synchronized to the AC field, allowing camera frame rates to capture the oscillations. The undersampled waveform facilitated the determination of the original waveform’s amplitude and phase. The operational frequency limits for Qdyne are defined by the 1/T2 decay and the speed of Rabi oscillations. b Raw data from a 10-kHz Qurack measurement. The vertical and horizontal axes show the amplitude and phase of the MW frequency modulation, respectively. The color map represents the photoluminescence (PL) accumulated over 10 ms. A dip in PL indicates the matching condition. c Raw data from a 2.3 MHz Qdyne measurement. Here, the 2.3 MHz AC magnetic field is undersampled to a 2.1 Hz waveform.

Qurack is based on that the AC magnetic field detunes the MW Rabi driving of NV spins from resonance, but the frequency modulation with the same amplitude and phase as the AC magnetic field retains the MW Rabi driving resonant, resulting in low photoluminescence (PL). In the Qurack experiment, the amplitude (so-called deviation) and phase of frequency modulation are swept, while the green laser and MW are continuously irradiated. The amplitude and phase of the AC magnetic field are derived by exploring the matching condition (Fig. 1b): when the AC magnetic field and frequency modulation have the same amplitude and phase, the NV center’s PL intensity is low because the dip in the ODMR, where the intensity of the PL is low, is tracked. However, in the case of a mismatch and loss of tracking, PL intensity increased. Assuming that the ODMR line shape is a Lorentzian function with the offset of \({I}_{0}\), the contrast of \(C\), and the linewidth of \(\sigma\), the PL count \(N\) during the exposure time \(T\) (integer multiple of the period of the target AC field \(2\pi /\omega\)) is expressed as follows:

Here, \({\vec{B}}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\) and \(\vec{\Delta F}\) indicate vectors in a phasor plot whose norm (angle) corresponds to the amplitude (phase) of the AC magnetic field and the frequency modulation. The matching condition (\({\vec{B}}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}=\vec{\Delta F}\), both the amplitude and phase match) exhibits the lowest PL count, whereas others do not (see Methods for more details).

Figure 1b shows an example of measuring a 10 kHz AC magnetic field. The vertical and horizontal axes represent the amplitude and phase of frequency modulation, respectively. The color map represents the integrated PL count for 10 ms. The dip in the PL indicates the matching condition. To extract the minima in the amplitude and phase axis, we fit the primary data with a model whose variables are amplitude, phase, linewidth, contrast, and offset. The amplitude of the AC magnetic field was calculated to be 709 µT, and the phase was 316°.

Qdyne is based on the heterodyne undersampling of the AC field. The AC magnetic field is measured by a sequence train, including MW pulses (a dynamic decoupling sequence XY8 was used in this study) and laser readout. The MW pulses are synchronized with the period of the target magnetic field. During MW pulses, a Larmor precession in response of the AC magnetic field is accumulated. A laser pulse is used to read out the accumulated signal. Each measurement sequence, sectioned by dashed lines in Fig. 1a, measurs different initial phases; therefore, AC magnetic field is undersampled. The amplitude and phase of the undersampled waveform are the same as those of the original AC magnetic field. Figure 1c shows an example of measuring a 2.3-MHz AC magnetic field. In this case, a 2.3-MHz AC magnetic field was down-converted to 2.1 Hz, which was sufficiently slow and could be captured by the charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. (See Supplementary Figs. 1–7 for the details of principle, configurations, and sequence).

Demonstration of AC magnetic field imaging over a wide frequency range

Before imaging the soft magnet, we performed imaging of the AC Ampere magnetic field from a coil as a proof-of-principle experiment for wide-frequency-range magnetic field imaging (Fig. 2a). An AC current \({I}_{{\rm{AC}}}\) was applied to a coil with N = 50 turns. The frequency was swept from 100 Hz to 200 kHz for Qurack, and from 237 kHz to 2.34 MHz for Qdyne. At the same time, the amplitude and phase of the magnetic flux were monitored using a reference coil with \(N=1\) turn. The Ampere magnetic field was imaged by the NV centers placed nearby the reference coil. The magnetic field was expected to be uniform within the laser spot because the diameter of the laser spot (Φ130 µm) was considerably smaller than the size of the coil (several centimeters). A CCD camera was used to image the red PL against a 532-nm-green laser irradiation. The spatial resolution of magnetic field imaging, estimated from the NV layer thickness, was 2 µm for the results in Figs. 2 and 3, and 5 µm for those in Fig. 4. The spatial resolution can be reduced to ~400 nm, which is restricted by optical diffraction22. The laser and MW, which are required to initialize, manipulate, and read the quantum state, were applied uniformly within the FOV (See Supplementary Figs. 1, 8 for the details of configurations of optics and MW antenna, respectively). The laser power was 500 mW. Two types of MWs, frequency-modulated or gated, were irradiated for Qurack (kHz) and Qdyne (MHz) measurements, respectively. The Rabi frequency in Qurack (Qdyne) measurement was 200 kHz (3.6 MHz) (see Supplementary Fig. 8). It took ~5 min for one Qurack image and ~10 min for one Qdyne image. Here, one image denotes “simultaneous mapping of amplitude and phase for one frequency condition.”

a Experimental setup. The red PL against a 532-nm green laser was imaged. Two types of MW pulses, either frequency-modulated or gated, were used for kHz (Qurack) or MHz (Qdyne) measurements, respectively. NV centers image an Ampere magnetic field induced by an AC current in a coil, with a reference coil measuring the magnetic field’s amplitude and phase. b Amplitude and phase mapping at 100 Hz measured by Qurack and at 2.34 MHz measured by Qdyne. The scale bars are 50 µm. c Amplitude and phase as functions of frequency. Red and blue plots represent data from Qurack and Qdyne imaging, respectively, showing almost constant amplitude and phase across the measured frequencies.

a Experimental setup. Magnetizations in soft magnetic CoFeB–SiO2 thin film were driven by magnetic field HAC // y-axis produced by AC current running through the drive coil. The direction of HAC was parallel to the hard axis. Simultaneous imaging of the amplitude and phase of the AC stray field from thin film was performed using NV centers. The detection axis of the magnetic field is parallel to the z-axis. Sense coil monitored IAC to keep the amplitude constant and determine the timing of the zero phase. b Side view of the experimental setup along the yz-plane. The AC drive field HAC drives magnetization, the N and S poles appear alternately at the edge, and the AC stray field was outpoured from the edge. c Optical image of the FOV in the xy-plane. The scale bar was 50 µm. d, e Amplitude and phase of the stray field at 200 Hz, 1 kHz, and 10 kHz were imaged by Qurack, and 329 kHz, 693 kHz, and 2.34 MHz were imaged by Qdyne. Almost the same trend was observed from 200 Hz to 2.3 MHz: the amplitude was concentrated at the edge, which implies the single domain structure, and the phase delay was almost zero. Notice that the error in the phase is large where the amplitude is small. The scale bars are 20 µm. f Amplitude and phase versus frequency. Here, kHz (~MHz) range data are measured by Qurack (Qdyne). The selected locations are indicated as crosshairs in (d, e). The amplitude is normalized to compare the results for various frequency ranges, referring to the sense coil. The lack of the plot is due to elimination of the data with ill-fitting (\({r}^{2}\) score <0.15). The phase was not delayed up to the MHz frequency range, which implied that the energy loss was almost zero. g Energy loss and phase delay. Energy loss corresponds to the closed area of the M–H loop. Zero-phase delay indicates that the M–H loop is linear and the energy loss is zero.

a Optical image of the FOV. The scale bar is 50 µm. b Amplitude and phase when the external field is applied parallel to the easy axis. The gray pixels indicate the overflows of the amplitude. The scale bars are 20 µm. c Amplitude and phase versus frequency. The selected locations are marked with crosshairs in (b). The lack of the plot is due to elimination of the data with ill-fitting (\({r}^{2}\) score <0.15) or amplitude overflow. The purple plot is the same as the purple plot in Fig. 3f. The amplitude was larger compared with when H//hard axis. The phase is delayed by −30° at 100 Hz, and the phase delay increases as the frequency increases, which implied increased energy loss. d Energy loss and phase delay. The increase in the phase delay denotes that the M–H characteristic becomes broad, and the energy loss increases.

The uniform amplitude and phase of the magnetic field were mapped. Figure 2b shows the mapping of the phase and amplitude at 100 Hz measured by Qurack and at 2.34 MHz measured by Qdyne. The average and standard deviation of the amplitude obtained by Qurack and Qdyne were 753 ± 18 µT and 1317 ± 85 nT, respectively. The phase represents the difference between the phase of the magnetic field measured by the NV center and the phase monitored by the reference coil. Qurack and Qdyne obtained average and standard deviations of the phase of 1.3 ± 1.1° and 0.5 ± 1.1°, respectively. The difference in the amplitude between the Qurack and Qdyne results is due to the variation in amplitude of \( {I}_{{\rm{AC}}}\), considering the maximum measurable amplitude of the magnetic field for each protocol. The maximum quantifiable amplitude of Qurack was restricted by the maximum amplitude of the frequency modulation of the signal generator. We used Keysight N5172B with a maximum deviation of ±40 MHz, corresponding to ~1429 µT in terms of the magnetic field. In Qdyne measurement, the sensor’s reading-magnetic field amplitude characteristics were determined by the amount of phase accumulation of the quantum superposition in response to the magnetic field. The characteristic is a sine function with a \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}/2\) fold-back. The fold-back amplitude was inversely proportional to the frequency and 2.2 µT at 1 MHz, where an XY8 pulse with N = 1 repetition was used. The amplitude of the AC magnetic field was decreased to avoid the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}/2\) fold-back.

The estimated amplitude and phase were considered as functions of the frequency. Figure 2c shows the frequency dependence of the amplitude and phase. The horizontal axis represents the frequency. The vertical axis represents the average amplitude and phase within the laser spot. The error bars represent 95% intervals within the laser spot. The amplitude was normalized by magnetic flux \(\varPhi\) measured by the sense coil to compare the results of Qurack and Qdyne: the amplitude \({I}_{{\rm{AC}}}\) was varied considering the maximum measurable amplitude of the magnetic field for each protocol. Our results show that the normalized amplitude was constant, and the phase was always 0° as expected for a lossless coil. This phenomenon confirms the validity of our measurement protocols for both Qurack and Qdyne.

AC magnetic response imaging

We performed simultaneous imaging of the amplitude and phase of the AC stray magnetic field from a soft magnetic CoFeB–SiO2 thin films using the widefield AC magnetic field imaging system (Fig. 3a). The CoFeB–SiO2 thin film with a thickness of 150 nm was deposited on a thermally oxidized silicon substrates by facing-target sputtering. The detailed deposition process is explained in ref. 21. For imaging DC M–H characteristics of the same thin film, see ref. 23, whose results reveal that the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film exhibits strong in-plane uniaxial magnetic anisotropy, and the M–H characteristics imaged by the NV center are consistent with those observed by MOKE imaging. A DC bias field of 4 mT was applied along the z-direction to resolve the degeneracy of the NV centers, whose effect on the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film is negligible. An AC magnetic field HAC was applied to the thin film using an AC current IAC flowing through a drive coil with N = 80 turns. The direction of HAC was parallel to the hard axis. Sense coil monitors IAC to ensure constant amplitude and determines the time of the zero phase. Imaging of the AC stray field was performed using [111]-oriented NV centers, deposited on an Ib (111) diamond substrate through chemical vapor deposition (CVD, see “Methods”)24,25,26. The detection axis of the magnetic field was in the z-direction.

A stray field is generated from where the magnetization is discontinuous, such as the edges or magnetic domain walls. Figure 3b shows a schematic of stray field measurements for a uniform magnetic thin film. An external AC magnetic field HAC parallel to the y-axis drives magnetization. The N and S magnetic poles appear alternately at the edge. These magnetic poles generate stray fields. The z-component of the stray field was detected using NV centers. The FOV of the AC stray field imaging included the edges of the thin film (indicated by arrows in Fig. 3c–e) because the stray field is strong around the edges. The lower (upper) part of the FOV was on (off) the magnetic film. The FOV size was Φ67 µm.

The kHz AC stray field was imaged using Qurack. The peak-to-peak amplitude of the current IAC was \(\pm\) 1 A. In terms of the magnetic field, this corresponds to \(H=\pm\) 100 A m−1, one-hundredth of H required for magnetization saturation. Figure 3d shows the amplitude and phase mappings of the stray AC field at 200 Hz, 1 kHz, and 10 kHz (see Methods for the post-process). The amplitude was concentrated at the edge, and the amplitude inside the film did not differ from that outside the film. This stray field concentration indicates that the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film is magnetically uniform within the FOV. The amplitude was slightly inhomogeneous comparing those at various locations within the edge. For example, the amplitude at the red crosshair in Fig. 3d was higher than that at the blue crosshair. This inhomogeneity within the edge is attributed to irregularities such as unevenness. Such concentration and slight inhomogeneity had been observed in the DC frequency23. For phase mapping, significant distribution was not observed, which was almost 0°. Please note that the phase error was large when the amplitude was small.

The MHz AC stray field was imaged using Qdyne. The peak-to-peak amplitude of current IAC was \(\pm\) 28 mA. As explained, the amplitude was lowered to avoid the fold-back. Figure 3e shows the mappings of the amplitude and phase of the AC stray field at frequencies of 329 kHz, 693 kHz, and 2.3 MHz. Even in the MHz range, the trend was similar to that in the kHz range; the magnetic field was strong at the edges, and the phase delay was almost 0°.

The frequency dependence of the amplitude and phase of the stray magnetic field is discussed in Fig. 3f, showing the amplitude and phase–frequency dependences at several locations on the edges. The selected locations are shown as crosshairs in Fig. 3d, e. To compare the results obtained by Qurack and Qdyne, the amplitude was normalized by referring to the sense coil that monitored the \({I}_{{\rm{AC}}}\) amplitude. The amplitude did not exhibit significant changes and the phase was not delayed up to the MHz range.

The observed zero-phase delay implies that the M–H characteristic is linear, and the energy loss is almost zero. Figure 3g shows an illustration of the relationship between phase delay and energy loss. The hysteresis loss corresponds to the area enclosed by the B–H or M–H loop. Here, B and M are related by eq. \(B={\mu }_{0}H+M\), where the difference is only linear component \({\mu }_{0}H\) (\({\mu }_{0}\) is vacuum permeability). The area of the loop is the same regardless of whether B–H or M–H is considered. In this study, the stray field reflects magnetization M because during the offset subtraction process, linear component \({\mu }_{0}H\) is subtracted. The zero-phase delay indicates phase difference does not exist between H and M oscillations. Then, the M–H characteristic is linear, and the energy loss is zero. These results indicate that the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film is suitable for application in thin-film inductors up to 2.3 MHz.

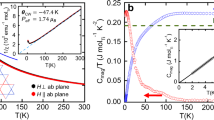

In addition to the condition with constant amplitude and phase, we observed a dependence on magnetic anisotropy, where the magnetization response along the easy axis differed from that of the hard axis (Fig. 4). At the DC frequency, the magnetization process differed when the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film was driven along the easy axis23: the M–H characteristics exhibited hysteresis, and the slope of the M–H characteristics was larger. Domain-wall motion was the dominant magnetic response mechanism.

Measurements and analyzes similar to the H // hard axis condition were conducted for the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film driven along the easy axis. The amplitude of the peak-to-peak current IAC was \(\pm\) 0.6 A. This current corresponded to \(H=\pm\)60 A m−1 in terms of magnetic field H, approximately one-fourth of the coercive field. The FOV included the edges of the thin films (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows the amplitude and phase of the AC stray field at 100 Hz, 1 kHz, 10 kHz, 20 kHz, and 50 kHz. Some pixels exhibited amplitude overflow (gray pixels in Fig. 4b), where the PL did not exhibit any apparent dip as a function of the amplitude of frequency modulation. However, clear minima were observed in the phase axis, and the estimated phase is reliable even when the amplitude overflowed. The observed amplitude around the edge was stronger than that along the \(H\)// hard axis by approximately one order of magnitude (100 µT of order for the \(H\) // hard axis and 1000 µT of order for the \(H\) // easy axis at 100 Hz, for example). The amplitude mapping revealed that the amplitude at the edges was stronger than that in other parts. This amplitude concentration denotes that magnetic poles are concentrated around the edge, which is reasonable. Inside the film, the amplitude tended to be larger than that outside the film, indicating that magnetic domains generating magnetic fluxes were formed. Such magnetic domain formation is observed in DC23, and the similar phenomenon could occur in the AC range.

Furthermore, the phase delay mapping exhibited distinct characteristics compared with the results for the \(H\) // hard axis (Fig. 4b). At 100 Hz, the phase was delayed by ~−30°, whereas the phase delay was ~0° when \(H\) // hard axis. Moreover, the phase delay increased up to −60° as the frequency increased. The phase delay did not exhibit any apparent spatial distribution.

Figure 4c shows the amplitude and phase–frequency dependencies at the edge, nearby edge, and on the magnet. The amplitude exhibited the peak around 10 kHz. A possible origin of this peak is domain-wall refinement, which was reported for other material systems4. The decrease in the amplitude at higher frequency range could be attributed to the domain-wall motion not catching up with the high-frequency drive and the fixed magnetization. The phase was delayed by ~−30°, even at the lowest frequency of 100 Hz. This phase delay indicates that the M–H characteristics exhibit hysteresis, and an energy loss occurrs. Furthermore, the phase delay increased with the increase in the frequency, which implies that the energy loss increases.

To facilitate the understanding that the observed increase in the phase delay implies that the M–H characteristics become broad, and the energy loss increases, Fig. 4d illustrates the relationship between the phase delay, broadening of M-H characteristics, and energy loss. The presence of a phase delay between the oscillations of M and H indicates that the M–H characteristics exhibit hysteresis (solid lines in Fig. 4d). In this case, the area enclosed by the M–H loop is not zero, indicating energy loss. An increase in the phase delay of M implies that the M–H characteristics become broad, the area enclosed by the M–H loop increases, and consequently, the energy loss increases (dashed lines in Fig. 4d). The phase delay dependent on the frequency could be attributed to magnetic domain-wall movement suppression. Such phenomenon can occur because when the \(H\) // easy axis, the dominant mechanism of magnetization change is domain-wall motion, and the mobility of magnetic domain walls is frequency dependent. Revealing the domain-wall motion will be a future work, e.g., nanoscale imaging with an NV-based scanning probe27 and frame-by-frame imaging of domain-wall motion.

Discussion

Qurack and Qdyne approaches used in this study could be improved using engineering approaches. First, we discuss the improvements of Qurack, where the amplitude overflow can occur (Fig. 4). The maximum measurable amplitude of the magnetic field depends on the maximum deviation (±40 MHz for Keysight N5172B) of the signal generator. Introducing high-performance signal generators will increase the maximum quantifiable amplitude.

Next, we discuss improvements of Qdyne. The frequency targeted by Qdyne is represented by \(f=1/(4\tau +2{t}_{{{{\rm{\pi }}}}})\), where \({t}_{{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}\) is the time of a \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\) pulse and 2τ is the time between \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\) pulses. Expanding the frequency lower limit should be realized by extending the spin coherence time T2 because we should employ longer τ to measure the lower frequency signal, otherwise during such a long interrogation, quantum coherence could be lost. In this experiment, the limit was ~300 kHz. The lower limit could be expanded by extending the coherence time through material engineering or magnetic noise reduction, such as spin-bath driving. Expanding the frequency upper limit should be realized by increasing the speed of spin manipulation, that is, the Rabi frequency. In our experiment, the limit was ~2.3 MHz. When Rabi oscillation becomes faster and \({t}_{\pi }\) becomes shorter, \(f\) could be increased. This phenomenon could be achieved through strong MW irradiation by innovations in MW antenna design. However, irradiating strong MW results in heating. Therefore, heat dissipation design is essential.

Simultaneous imaging of the amplitude and phase of AC magnetic fields across a broad frequency range offers numerous potential applications. So far, stroboscopic MOKE imaging has been pivotal in observing magnetizations under AC excitation2,4,28. However, imaging with NV centers presents several advantages. First, stray field imaging using NV centers is sensitive to magnetic textures within the material, providing a more comprehensive view than MOKE imaging, which primarily detects surface magnetic textures with a typical penetration depth of several tens of nanometers29. This capability allows for the observation of magnetization in deeper layers and in magnetic materials that are coated30. Second, the output from NV centers includes both amplitude and phase, which are more directly correlated with energy loss, in contrast to MOKE’s primary function of determining the shape of magnetic domains. Third, NV-based methods can be extended to vector magnetic field imaging, offering a more detailed representation than MOKE, which is sensitive only to the projection of magnetization along a specific axis. These features of NV centers are particularly valuable for evaluating soft magnets in power electronics. Finally, while MOKE measures magnetization, NV centers measure the magnetic field, making NV-based techniques more applicable in scenarios where the magnetic field is a more critical metric than magnetization, such as in electromagnets and magnetic recording technologies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed a diamond quantum imager using NV centers that can simultaneously perform amplitude and phase imaging of a magnetic field over a wide frequency range, up to MHz, with the Qurack and Qdyne protocols. Soft magnetic CoFeB–SiO2 thin films exhibited an negligible phase delay up to 2.3 MHz, which implied that the energy loss in the CoFeB–SiO2 thin film was negligible. Moreover, we observed a dependence on the anisotropy of the thin film. When the thin film was driven along the easy axis, the phase was delayed as the frequency increased, which implied that the loss increased. Appropriate engineering approaches can be used to expand the frequency band of stray field imaging. The results imply diamond quantum sensors can be used to analyze soft magnets and improve the performance of power electronics.

Methods

Post-processing in AC magnetic response imaging

The magnetic field sensed by the NV center included both the stray magnetic field from the magnetic thin film and the offset field directly delivered from the drive coil. The stray magnetic field from the magnetic material was calculated by subtracting the offset field from the total magnetic field. The offset field was assumed to be uniform within the FOV and was the average value of the AC magnetic field measured in the absence of a magnetic film. When subtracting the offset field, the \({\mu }_{0}H\) component was also subtracted from total magnetic field \(B={\mu }_{0}H+M\). Therefore, the results reflected the magnetization \(M\) of the soft magnetic thin film, not magnetic flux density \(B\). Moreover, the artifacts related to the laser intensity distribution were corrected.

Relationship among PL intensity, AC magnetic field, and frequency modulation in Qurack measurement

Let the resonant frequency of the NV center \({F}_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}\left(t\right)\) and the MW frequency \({F}_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\left(t\right)\) be

Here, \({f}_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}\) and \({f}_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\) are the DC components (around 3 GHz). \(\gamma {B}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\) and \(\Delta F\) are the amplitude (40 MHz at most) \(\gamma\) is the gyromagnetic ratio. \(\Delta F\) is a deviation, in other words. \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\) is the phase (0– 360°). \(\omega\) is the oscillation frequency of the AC magnetic field (100 Hz to 200 kHz). Assuming \({f}_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}={f}_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\) (no static detuning), the detuning between the resonant frequency and the MW frequency is

Here, \({\vec{B}}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\) and \(\overrightarrow{{\Delta} {F}}\) indicate vectors in a phasor plot, that is, \({\vec{B}}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}=(\gamma {B}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\cos {\phi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}},\gamma {B}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\sin {\phi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}})\) and \(\overrightarrow{{\Delta} {F}}=({\Delta} {F}\cos {\phi }_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}},\Delta F\sin {\phi }_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}})\). Here \(\phi\) is a phase depending on \(\gamma {B}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}\), \(\Delta F\), \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\). The PL rate versus time \(I(t)\) when the ODMR line shape is a Lorentzian function with the offset of \(I_{0}\), the contrast of \(C\), and the linewidth of \(\sigma \), is expressed as follows:

The PL count \(N\) during the exposure time \(T\) (integer multiple of the period \(2\pi /\omega\)) is expressed as follows:

Using the following formula:

Equation (5) is calculated as follows:

The matching condition (\({\vec{B}}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}=\vec{\Delta F}\leftrightarrow\) \(\gamma {B}_{{{{\rm{NV}}}}}=\Delta F\) and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}={\phi }_{{{{\rm{MW}}}}}\)) exhibits the lowest PL count, whereas others do not (see Supplementary Figs. 9–11 for the Qurack signal when the ODMR line shape is not a Lorentzian function. Also, see Supplementary Fig. 12 for the comparison between Qurack and Ramsey Lock-In31).

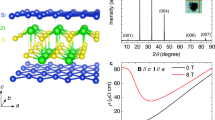

Formation of NV centers and specification

NV centers are formed by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition (MPCVD) on type Ib (111) diamond single crystal24,25,26. During the MPCVD, N2 gas was introduced as a source to form NV centers. See sample C in ref. 25 for details of deposition conditions. NV centers are perfectly aligned along the [111] direction, reducing the chance of peak degeneracy and simplifying signal analysis. The thickness was 5 µm (2 µm) for the easy (hard) axis measurement. NV density was 4 × 1017 (4 × 1016) cm−3. T2* estimated by ODMR linewidth was >47 (43) ns. T2 under XY8 (N = 1) was 3.6 (5.8) µs.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Silveyra, J. M., Ferrara, E., Huber, D. L. & Monson, T. C. Soft magnetic materials for a sustainable and electrified world. Science 362, eaao0195 (2018).

Flohrer, S. et al. Dynamic magnetization process of nanocrystalline tape wound cores with transverse field-induced anisotropy. Acta Mater. 54, 4693–4698 (2006).

Han, L. et al. A mechanically strong and ductile soft magnet with extremely low coercivity. Nature 608, 310–316 (2022).

Flohrer, S. et al. Magnetization loss and domain refinement in nanocrystalline tape wound cores. Acta Mater. 54, 3253–3259 (2006).

Magni, A. et al. Domain wall processes, rotations, and high-frequency losses in thin laminations. IEEE Trans. Magn. 48, 3796–3799 (2012).

Bertotti, G. Physical interpretation of eddy current losses in ferromagnetic materials. I. Theoretical considerations. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 2110–2117 (1985).

Bertotti, G. General properties of power losses in soft ferromagnetic materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 24, 621–630 (1988).

Fiorillo, F., Ferrara, E., Coïsson, M., Beatrice, C. & Banu, N. Magnetic properties of soft ferrites and amorphous ribbons up to radiofrequencies. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 322, 1497–1504 (2010).

Jelezko, F., Gaebel, T., Popa, I., Gruber, A., & Wrachtrup, J. Observation of coherent oscillations in a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 076401 (2004).

Neumann, P. et al. Single-shot readout of a single nuclear spin. Science 329, 542–544 (2010).

Maze, J. R. et al. Nanoscale magnetic sensing with an individual electronic spin in diamond. Nature 455, 644–647 (2008).

Taylor, J. M. et al. High-sensitivity diamond magnetometer with nanoscale resolution. Nat. Phys. 4, 810–816 (2008).

Le Sage, D. et al. Optical magnetic imaging of living cells. Nature 496, 486–489 (2013).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Kitagawa, R. et al. Pressure sensor using a hybrid structure of a magnetostrictive layer and nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 044089 (2023).

Mizuno, K., Ishiwata, H., Masuyama, Y., Iwasaki, T. & Hatano, M. Simultaneous wide-field imaging of phase and magnitude of AC magnetic signal using diamond quantum magnetometry. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Smits, J. et al. Two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with a microfluidic diamond quantum sensor. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw7895 (2019).

Schmitt, S. et al. Submillihertz magnetic spectroscopy performed with a nanoscale quantum sensor. Science 356, 832–837 (2017).

Boss, J. M., Cujia, K. S., Zopes, J. & Degen, C. L. Quantum sensing with arbitrary frequency resolution. Science 356, 837–840 (2017).

Mizuno, K. et al. Wide-field diamond magnetometry with millihertz frequency resolution and nanotesla sensitivity. AIP Adv. 8, 125316 (2018).

Takamura, Y. et al. Fabrication of CoFeB–SiO 2 films with large uniaxial anisotropy by facing target sputtering and its application to high-frequency planar-type spiral inductors. IEEE Trans. Magn. 59, 2801204 (2023).

Scholten, S. C. et al. Widefield quantum microscopy with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: Strengths, limitations, and prospects. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 150902 (2021).

Kitagawa, R. et al. Wide-field imaging of the magnetization process in soft magnetic-thin film using diamond quantum sensors. Appl. Phys. Express 17, 017002 (2024).

Tahara, K., Ozawa, H., Iwasaki, T., Mizuochi, N. & Hatano, M. Quantifying selective alignment of ensemble nitrogen-vacancy centers in (111) diamond. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 193110 (2015).

Ozawa, H., Tahara, K., Ishiwata, H., Hatano, M. & Iwasaki, T. Formation of perfectly aligned nitrogen-vacancy-center ensembles in chemical-vapor-deposition-grown diamond (111). Appl. Phys. Express 10, 045501 (2017).

Tsuji, T., Ishiwata, H., Sekiguchi, T., Iwasaki, T. & Hatano, M. High growth rate synthesis of diamond film containing perfectly aligned nitrogen-vacancy centers by high-power density plasma CVD. Diam. Relat. Mater. 123, 108840 (2022).

Casola, F., van der Sar, T. & Yacoby, A. Probing condensed matter physics with magnetometry based on nitrogen-vacancy centres in diamond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17088 (2018).

Ogawa, K. et al. Ultrafast stroboscopic time-resolved magneto-optical imaging of domain wall motion in Pt/GdFeCo wires induced by a current pulse. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 033151 (2023).

Qiu, Z. Q. & Bader, S. D. Surface magneto-optic Kerr effect. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 71, 1243–1255 (2000).

Zhukov, A. Design of the magnetic properties of Fe-rich, glass-coated microwires for technical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 16, 675–680 (2006).

Qiu, Z., Hamo, A., Vool, U., Zhou, T. X. & Yacoby, A. Nanoscale electric field imaging with an ambient scanning quantum sensor microscope. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 107 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Takayuki Shibata for the microwave antenna design and fabrication. This study was supported by the MEXT Quantum Leap Flagship Program (MEXT Q-LEAP) grant number JPMXS0118067395 and JST SPRING grant number JPMJSP2106. A.Y. is partly supported by the Quantum Science Center (QSC), a National Quantum Information Science Research Center of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through Grant GBMF 9468, and the U.S. Army Research Office (ARO) under Grant numbers W911NF-22-1-0248.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K. and T.K. conceived the idea. M.H., A.Y., T.I. and S.N. supervised the project. R.K. and A.N. designed and conducted the experiment. R.K. analyzed the data with support from T.K. and Y.T. T.T. prepared the NV sample. H.N. prepared the CoFeB-SiO2 sample. A.Y. provided the idea of the Qurack imaging. R.K. built the Qurack imaging system. K.M. built the Qdyne imaging system. R.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Vladimir V. Soshenko, Amit Finkler and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aldo Isidori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kitagawa, R., Nakatsuka, A., Kohashi, T. et al. Imaging AC magnetization response of soft magnetic thin films using diamond quantum sensors. Commun Mater 6, 104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00812-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00812-4