Abstract

Organic polar small molecules exhibit spontaneous orientation polarization (SOP) in vacuum-deposited amorphous films. This phenomenon arises because of the asymmetric molecular interactions at the interface between the film surface and vacuum during the deposition process. Here, we investigate the impact of functional groups on the SOP of bent-shaped polar molecules. The results demonstrate that the differences in polarizability between the head and tail functional groups in polar molecules drive the orientation polarization in the films. Enhancing the SOP involves the introduction of two functional groups with distinct polarizabilities in the head and tail groups to promote asymmetric interactions. The developed polar molecule, incorporating bulky alkyl and sulfonyl groups, exhibits a high surface potential growth rate of +321 mV nm−1 in the SOP film. These findings enable the precise control of the molecular orientation in amorphous films and the development of highly polarized electret materials without charging processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spontaneous molecular orientation is an important factor affecting the physical properties of organic thin films. In particular, the precise control of molecular orientation in amorphous thin films has been studied to functionalize amorphous films, originating from the formation of anisotropic structures. Polar molecules such as tris(8-quinolinolato)aluminum (Alq3) spontaneously orient their permanent dipole moments (PDMs) in the film growth direction during vacuum deposition, forming spontaneous orientation polarization (SOP)1. Electrically polarized amorphous thin films, such as a vacuum-deposited Alq3 film, can be applied as self-assembled electrets (SAEs) for vibration power generation2,3. Conventional electrets can be formed by polarizing insulating polymers, such as CYTOP and related polymers4,5,6,7, which stabilize the polarization state and have been reported to be highly durable electrets. The maximum power output of a vibrational power generation device is proportional to the square of the surface charge density of the electrets. The surface charge density of CYTOP7 electrets is 2.0–3.0 mC m−2, while vacuum-deposited films of SOP molecules, such as Alq3 and 1,3,5-tris(1-phenyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)benzene (TPBi), exhibit a surface charge density of 1.4–1.7 mC m−2; thus, strong polarization of SAEs can be formed without any charging process8,9. However, the orientation degree of the PDMs of polar molecules remains limited8,9,10, leaving room for further improvement in the surface charge density and SOP magnitude.

The SOP magnitude and polarity depend on the chemical structures of polar molecules8,11,12 and film-formation process parameters, such as deposition rates and substrate temperatures (Tss)9,13. Controlling the deposition rates and Tss during deposition directly affects the diffusivity of polar molecules on the substrate or thin-film surface during deposition, and either promotes or inhibits the orientation of polar molecules. The basic trend is that at a low deposition rate or high Ts, the SOP magnitude decreases owing to excessive molecular diffusion, which suppresses the formation of orientation polarization, and vice versa. This suggests that orientation polarization occurs during the diffusion and reorientation of molecules at the interface between the vacuum and film surface during the deposition process, similar to the orientation of the transition dipole moments (TDMs) of amorphous emitting molecules used in organic light-emitting diodes14. Additionally, these trends in the formation process of vapor-deposited glassy films, such as Alq3 and other glassy molecules, have been well explained by the surface equilibration mechanism, that is, the molecular orientations in the films originate from the structure of the supercooled liquid formed on the film surface during deposition15,16,17. This mechanism explicitly indicates that controlling the molecular alignment on the growing film surface is essential for the formation of anisotropic structures in films16,18. In a typical solid film, the dipole-dipole interactions between polar molecules cancel out the polarization of neighboring molecules19,20,21; however, in an SOP thin film, the preferential head-to-tail orientation of polar molecules results in strong orientation polarization and giant surface potentials (GSPs) at the film surface. Therefore, a driving force is required for the SOP to form vertical head-to-tail orientations without polarization cancellation by dipole-dipole interactions in vacuum-deposited films.

Previous research using Monte Carlo simulations has identified that the formation of orientation polarization, that is, vertical head-to-tail orientation on the film surface during deposition, originates from short-range van der Waals (vdW) interactions between molecules and surfaces during deposition22. Cakaj et al. reported that the SOP of bis-4-(N-carbazolyl)phenyl)phenylphosphine oxide (BCPO) originates from hydrogen bonding and/or inductive forces between the surface mobile molecules and deposited underlayer molecules or substrates9. The relatively strong interactions originating from the phosphine oxide (PO) groups induced the orientation toward the growing film, resulting in a PDM orientation in the film thickness direction. In contrast, molecular orientation can be achieved by weakening the intermolecular interactions of fluoroalkyl-based functional groups, such as trifluoromethyl (CF3) and hexafluoropropane (6F) units8,12. Our previous studies revealed that the introduction of CF3 units into polar molecules efficiently formed a molecular orientation by introducing a CF3 group with a low polarizability, which weakened the interaction with the thin-film surface during the deposition process, causing the CF3 group to orient toward the vacuum side. Thus, one of the driving forces for SOP formation is introducing asymmetric vdW interactions in a polar molecule using functional groups with distinct properties8,9,23,24,25,26.

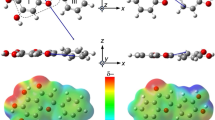

In this study, we investigated the impact of functional groups, such as head (X) and tail (R) groups, on the SOP formation of bent-shaped polar molecules (Fig. 1a). The proposed bent-shaped molecules possess the PDMs along the head-to-tail direction of the molecules, indicating that the polarity of the GSP growth rate relative to the film thickness (GSP slope) suggests which orientation direction is dominant, that is, Λ- or V-type orientations (Fig. 1b, c). We introduced some functional groups as the X and R parts to tune the polarizabilities, thereby affecting the vdW interactions. The experimental results of the film polarization indicated that functional groups with low or high polarizabilities critically induced their orientations toward the film growth direction; in particular, alkyl and sulfonyl (SO) groups tended to orient themselves toward the vacuum and substrate sides on the film surface during deposition. Finally, we developed an SOP molecule using bulky alkyl and polar SO units exhibiting a GSP slope of +321 mV nm−1, which is higher than that of conventional SAEs, such as Alq3 and fluoroalkyl-based polar molecules. Furthermore, we calculated the atomic polarizability of polar molecules based on density functional theory (DFT) and successfully demonstrated a moderate correlation between the SOP properties and the polarizabilities of the functional groups. Our findings, such as the established molecular design strategies, will help improve the out-of-plane molecular orientation and GSP slopes.

Results and discussion

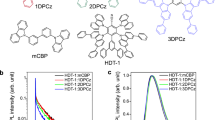

To investigate the impact of functional groups on the SOP formation of bent-shaped molecules, non-fluorinated polar molecules (Fig. 1a) with various head groups, such as fluorenyl (FL-2PI), isopropyl (6H-2PI), cyclohexyl (CH-2PI), and sulfonyl (SO-2PI), were designed based on 6F-2PI which consists of a 6F backbone and phthalimide (PI)12. The calculated PDM directions and electrostatic potential (ESP) mappings are shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1, respectively, and the PDM magnitudes (p) of each compound are summarized in Table 1. The surface potentials of vacuum-deposited thin films on indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass substrates were measured using the Kelvin probe (KP) method. Figure 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2 show the thickness dependence of the surface potential of the vacuum-deposited thin films of bent-shaped PI-based molecules. The polar molecules exhibited surface potential growth that increased in proportion to the film thickness, indicating that the PDMs of each polar molecule spontaneously formed orientational polarization in their films. The GSP slopes are listed in Table 1. The polarities of the GSP slopes of molecules other than SO-2PI were negative, indicating that the head groups, such as 6F, FL, 6H, and CH, faced the film surface side in the deposited films on average, that is, the Λ-type orientation (Fig. 1b). The degree of orientation of the PDMs (<cosθ>) was calculated using the GSP slope value (m) and the equation, <cosθ > = mε0εr/pn, where θ, n, ε0, and εr are the tilt angle of PDM with respect to the surface normal, molecular number density, dielectric constant of vacuum, and relative permittivity, respectively. The value of εr was assumed to be 3.0, which is typical of organic materials. The n value was estimated using X-ray reflectivity (XRR) measurements. XRR patterns of the vacuum-deposited thin films on a sapphire substrate were measured, and the fitting of their profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3) was performed to obtain the film density (ρ). The obtained ρ values for these films were 1.26–1.44 g cm−3 (Supplementary Table 1). The number density, n, was calculated as n = ρNA/M, where NA and M are Avogadro’s number and molecular weight, respectively. Additionally, we confirmed that the deposited films were amorphous using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Supplementary Fig. 4), and the XRD results showed broad amorphous halo patterns. However, the halo structures were different for the films; therefore, further detailed analysis is necessary to understand the full structure of the films in the future. The calculated <cosθ> values for polar molecules exhibiting negative GSPs ranged from −0.079 to −0.18, depending on the functional groups. As in previous studies8, 6F-2PI exhibited a high |<cosθ>|; however, the non-fluorine backbone, such as the bulky cyclohexyl-based polar molecule, CH-2PI, also exhibited a high |<cosθ>|. We note that the reason for the small GSP slope of CH-2PI, despite the high |<cosθ>|, is the small p of the molecule (2.70 Debye). It has been reported that <cosθ> correlates with the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the molecules. This is because the degree of molecular diffusion during the deposition process correlates with the ratio of the substrate temperature (Ts) to the Tg8,12,25,27,28,29. We examined the Ts/Tg dependence of the <cosθ> values of the developed molecules and confirmed that the differences in <cosθ > s were not attributed to the Tgs of the developed molecules (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Hence, the comparable <cosθ> values of 6F-2PI and CH-2PI suggest that bulky alkyl groups, such as the CH group, also facilitate the molecular orientation in the film thickness direction, similar to the 6F groups. This can be attributed to the asymmetric interactions in the molecules owing to the difference in polarizability between the head and tail groups. The polarizabilities affect the strength of intermolecular interactions, such as induction and dispersion forces30. In general, the polarizabilities of alkyl hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon groups are lower than those of aromatic groups such as PI31,32, which can induce highly asymmetric interactions in polar molecules such as 6F-2PI and CH-2PI, exhibiting relatively high |<cosθ>| values. In contrast, for FL-2PI, both the head and tail of the molecule consist of aromatic groups, such as fluorene and PI, leading to a small asymmetry in the interactions and a low |<cosθ>|.

The vacuum-deposited SO-2PI film exhibited a positive GSP slope (+25.3 mV nm−1). This indicates that, on average, the SO units of the bent-shaped molecules are oriented toward the substrate side (V-type orientation shown in Fig. 1c), suggesting that the SO group tends to orient preferentially toward the substrate side owing to its high polarizability. While the low polarizability of fluoroalkyl groups keeps them away from the substrate side, the high polarizability of the SO group, originating from the relatively high atomic polarizabilities of S and O atoms, induces strong interactions with the substrate or underlayer molecules. The small value of |<cosθ>| could be attributed to the small asymmetry of the polarizabilities of the SO and PI units, indicating that both the head (SO) and tail (PI) tend to orient toward the substrate surface. Namely, the small asymmetry of their polarizabilities results in competitive orientation formation, lowering the |<cosθ>| in the films.

To further clarify the orientation-inducing effect of bulky alkyl groups, we examined the SOP of 6F-2PI derivatives with PIs decorated with alkyl groups (methyl (Me) and tertiary butyl (tBu) groups), such as 6F-2PIMe and 6F-2PItBu (Supplementary Fig. 8). Although the PDM directions of these molecules are similar to those of 6F-2PI, alkyl-decollation of the PI group can lower the polarizability of the tail group compared to that of pristine PI. The thickness dependence of the surface potential is shown in Fig. 3. The GSP slopes of 6F-2PIMe and 6F-2PItBu were −124 and +21.7 mV nm−1, respectively (Table 2). These results indicate that the Me-substitution decreased |<cosθ>|, and the tBu-substitution induced an SOP polarity change compared to 6F-2PI. The decrease in |<cosθ>| of 6F-2PIMe is attributed to the low polarizability of the tail group of Me-decorated PI, which leads to reduced polarizability asymmetry in the molecule. The polarity change in the SOP of the 6F-2PItBu film indicates that the introduction of the tBu group strongly facilitates the orientation of the PItBu units toward the film surface (V-type orientation) owing to the lowered tail polarizability, even though the 6F unit also possesses a similar orientation-inducing effect because of its low polarizability.

We revealed that bulky alkyl and SO groups can induce spontaneous molecular orientation in the film growth direction. The small |<cosθ>| values of 6F-2PItBu and SO-2PI were attributed to the low asymmetry of the polarizabilities of the head and tail groups. To improve <cosθ> by tuning the difference in polarizabilities, we designed a polar molecule, SO-2PItBu (Supplementary Fig. 9), with a combination of an SO unit and bulky tBu groups as the head and tail structures, respectively. To further clarify the validity of the proposed molecular design, another SO-based polar molecule, SODI-2CH, was also developed, which possesses sulfonyldiphthalimide (SODI) and CH units (shown in the inset of Fig. 4). The head (SO) side of both molecules was negatively polarized because of the strong polarization of the SO unit, which was in the same direction as that of 6F-2PI. Figure 4 shows the thickness dependence of the surface potentials of the deposited SODI-2CH and SO-2PItBu films. The deposited films exhibited positive GSP with the slopes of +162 and +321 mV nm−1 for SODI-2CH and SO-2PItBu, respectively. The positive GSPs corresponded to V-type molecular orientations in the deposited films, indicating that both the head and tail groups effectively facilitated the formation of a preferential orientation. The calculated <cosθ> values were approximately 0.20–0.24, which were higher than those of SO-2PI and 6F-2PItBu owing to the tuned polarizability asymmetry of the developed molecules. The smaller GSP slope of SODI-2CH was attributed to its smaller PDM than that of SO-2PItBu because of the inverted connection of the PI units in SODI-2CH. The <cosθ> value of SO-2PItBu was clearly improved by a factor of 15 compared to that of SO-2PI (Tables 1 and 2), indicating that the simple method, that is, the introduction of tBu groups, assisted the orientation polarization. Previous studies have shown that strong dipole-dipole interactions between polar molecules with a large PDM cause a severe decrease in the |<cosθ>| values because of the cancellation of molecular dipoles in the deposited films19,20. However, SO-2PItBu maintained high <cosθ> and GSP slope values despite its large PDM of 10.5 Debye. This is attributed to the well-designed asymmetry of the polarizability of the molecule, which facilitates ordered molecular orientation to build a large SOP without fluoroalkyl groups.

Here, we compared the polarizability (aij) of the head and tail groups in the tested polar molecules to investigate the relationship between their orientation properties and functional groups31,32. The atomic polarizabilities were calculated using the following equation: aijFj = µi(Fj), where Fj and µi(Fj) are the static electric field applied along the j-axis direction and i-axis component of the induced dipole moment under Fj, respectively. Static fields were applied along the x-, y-, and z-axes in both the positive and negative directions (Supplementary Fig. 10). We confirmed a linear relationship between the applied field and the induced dipole moment magnitude in the range of −0.005 to +0.005 atomic units of the field (Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, we used the values of the induced dipole moment at ±0.005 atomic units to calculate the aij tensors. The isotropic polarizability (aiso(A)) of atom (A) was calculated as the average of the diagonal components of the tensor (aiso = Tr(aij)/3). The anisotropy of tensor (Δa) was calculated as Δa ={0.5[3Tr(aij2) – (Traij)2]}0.5. The molecular models and atomic polarizabilities (aiso and Δa) of each molecule are summarized in Supplementary Figs. 10, 12–19 and Supplementary Tables 2–10, respectively. Based on these calculation results, we found (1) low aiso values for H and F atoms, (2) high aiso values for N, O, and S atoms, and (3) higher aiso values for aromatic C atoms than those of aliphatic C atoms. To investigate the relationship between polarizabilities and orientation degrees, we further calculated the mean polarizabilities (āh and āt) of the atoms composing the head (Ah) and tail (At) parts in each molecule using the following equations:

where Nh and Nt are the numbers of atoms of Ah and At, respectively. The selected Ah and At atoms are summarized in Supplementary Table 11. For these calculations, atoms up to the second atom from the outside of the molecule were selected as Ah and At. This is because the outer atoms would be important for intermolecular vdW interactions33. For example, in the case of 6F-2PI, (CF3)2 in the 6 F part and (CH)4 in the PI groups were used for Ah and At, respectively, whereas for SO-2PItBu, (SO2) and (CH)2(CH3)6 were used (Fig. 5a). The Ah and At components of the other molecules are shown in Supplementary Figs. 11–18. The calculated āh and āt values are listed in Supplementary Table 11. The āh values were higher for the aromatic hydrocarbon (FL) and SO groups than for the aliphatic hydrocarbon (6H and CH) groups. A similar trend was observed for At, indicating that the alky modification of the PI group resulted in a reduction in āt.

a Head (Ah) and tail (At) groups of 6F-2PI and SO-2PItBu. b Relationship between orientation degrees and the difference of polarizabilities (āh−āt) of polar molecules developed in this study. The broken red line indicates the linear fitting result. The error bars represent the standard deviation of mean orientation degrees.

Polarizabilities affect the intensity of the induction and dispersion forces, and the dispersion force between molecules is a more important component in organic solid films34,35,36. Assuming that the main origin of SOP is the dispersion force interactions between a polar molecule and the film surface during vacuum deposition, the asymmetry of the interactions between the head/tail group and the film surface, that is, \({w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{hs}}}}}-{w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ts}}}}}\), would directly influences the mean orientation degree of polar molecules (Supplementary Note 2). The \({w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{hs}}}}}\) and \({w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ts}}}}}\) are the dispersion force free energies between the head/tail group and the surface, respectively. Furthermore, \({w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{hs}}}}}-{w}_{{{{\rm{disp}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ts}}}}}\) can be estimated to be proportional to āh−āt. The relationship between āh−āt and the degree of PDM orientation for each polar molecule, as shown in Fig. 5b, demonstrates a positive correlation. When āh is small, the head side is oriented toward the vacuum side on the surface during the deposition process, resulting in a Λ-type orientation. Conversely, when āt is small, the bent-shaped molecules exhibit a V-type orientation. The linear correlation coefficient in Fig. 5b was 0.87. The moderate linear correlation indicates that the SOP properties of the bent-shaped molecules are governed by the asymmetry of the dispersion interaction between a molecule and the surface, which can be tuned by the polarizabilities of Ah and At. One contributing factor for further improvement of the correlation is that the carbonyl groups in the polar molecules also possess high polarizability, which influences molecular interactions. Additionally, āh and āt represent the simple averages of the polarizabilities of Ah and At, respectively. More precisely, they need to be weighted based on correction factors, such as the number of electrons of atoms or the atomic radius. Supplementary Table 11 summarizes ā*h and ā*t calculated by weighted averaging using the number of electrons in each atom (see Supplementary Note 3 for details). In the relationship between ā*h−ā*t and the PDM orientation degree shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, the correlation coefficient was also moderate (0.83). Although we suggest that a better indicator than that shown above should be proposed, the average polarizability of the intramolecular head and tail sites is an important indicator for predicting the SOP of bent-shaped polar molecules.

Wang et al. recently reported that the alkyl substitution of TPBi enhances the <cosθ> and GSP slope values compared to TPBi. This enhancement occurred because alkyl substitution restricted the molecular conformations with unfavorable PDM directions to establish SOP10. However, the molecular conformations of the molecules in this study were essentially identical. Therefore, we estimated that the bulky alkyl substitution in this study potentially induced an anisotropic orientation, similar to that of the fluoroalkyl units. Furthermore, controlling the transition dipole moment (TDM) of emitter molecules in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) is essential for improving the light out-coupling efficiency. Rod- or disk-shaped molecules with high aspect ratios have been proposed to achieve a highly horizontal TDM orientation to the substrate plane and improve the light out-coupling efficiency of OLEDs28,37,38,39,40. However, the proposed strategies for controlling the molecular orientation in this study, that is, introducing bulky alkyl groups, aimed at a vertical molecular orientation to align the PDMs in the direction of the film thickness. Therefore, careful molecular design is necessary for emitter molecules decorated with bulky alkyl groups to achieve horizontal TDM orientation. Recently, Sahay et al. reported that controlling the balance of molecular properties, such as Tg, molecular size, molecular aspect ratio, and ESP distribution, is essential for improving the degree of TDM orientation of indolocarbazole-based emitter molecules with symmetrically attached tBu groups41. The authors estimate that symmetrical decorations of bulky alkyl groups along the molecular long axis would result in horizontal molecular orientation. However, the asymmetrical introduction in this study successfully induced the vertical orientation of the molecular planes, boosting the PDM orientation and SOP.

The estimated surface charge density, given by m×ε0εr, of the SO-2PItBu deposited film was 8.6 mC m−2, which is significantly higher than that of F-based SAEs and polymer electrets such as CYTOP (2–3 mC m−2)7. The proposed precise tuning of the molecular asymmetry can provide a dipolar electret film with a high surface charge density. We demonstrate the operation of electret films for vibration power generation. The vibration-based current profiles generated via probe (stainless steel) vibration in a Kelvin probe system were collected using an oscilloscope and voltage/current amplifier2. Figure 6a shows the induced current profiles generated via probe vibration above the vacuum-deposited films of 6F-2PI and SO-2PItBu on ITO-coated substrates in a vacuum chamber. The probe vibrated vertically above the SAEs at a frequency of 59.2 Hz; for example, the probe approached the SAEs in the time range of 23–32 ms and left them in the time range of 32–40 ms. The electrode vibration generated an alternating induced current, and the polarities of the induced current were different for the 6F-2PI and SO-2PItBu films. This was attributed to the different polarities of the surface polarization charges, that is, the negative and positive surface charges on the 6F-2PI and SO-2PItBu films, respectively (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the maximum value of the absolute current density for the SO-2PItBu electret was approximately 1.7-times higher than that for the 6F-2PI electret. Previous studies establishing operation models of SAE-based vibration power generators revealed that vibration-based generated current densities are proportional to the surface potential of electrets3. The surface potentials of the tested electret films of 6F-2PI (thickness: 113 nm) and SO-2PItBu (thickness: 116 nm) were +18.8 and −33.9 V, respectively, indicating that the 1.8-times higher surface potential of the SO-2PItBu film resulted in an enhancement of the induced current density in the operation of the electret films.

The photostability of GSP is governed by the light absorption of the deposited films. The photo-generated excitons are dissociated to charge carriers by internal electric field in SOP films, which compensate the polarization charges at the interfaces1,2,42. Therefore, polar molecules with wide band gaps are good candidates for stable SAEs43. Supplementary Fig. 21 shows the absorption spectra of the vacuum-deposited films of the developed polar molecules. They exhibited no clear absorption in the visible-light wavelength range, suggesting that the GSPs were stable under visible-light irradiation. Supplementary Fig. 22 shows the time-dependent surface potential changes of the SO-2PItBu film under light irradiation. Although strong UV irradiation with shorter wavelengths, such as 340 and 365 nm, quickly degraded the surface potential, the decrease in surface potential was suppressed under irradiation with 405 nm wavelength because of the limited absorption of the film at 405 nm. Furthermore, thermal stability is an issue for electret performance5. Supplementary Fig. 23a–c show the annealing temperature dependence of the surface potential of the deposited films of 6F-2PI, SO-2PItBu, and FL-2PI (thickness~100 nm). The surface potential of the films decreased upon annealing at high temperatures. The surface potentials of the 6F-2PI and SO-2PItBu films decreased dramatically at annealing temperatures of 70–80 °C; however, that of the FL-2PI film was maintained, even at high annealing temperatures of approximately 100 °C. We estimated that the high thermal stability of the film polarization of FL-2PI originated from its high Tg value. The high Tg of over 160 °C can suppress thermally induced crystallization, leading to the cancellation of the polarization (Supplementary Fig. 23d and e). Furthermore, we found that the surface potentials of the three SOP films with different orientation degrees vanished when the difference between the annealing temperature and Tg (annealing temperature − Tg) was approximately −50 to −40 °C. This suggests that developing a high-Tg backbone, such as the FL unit, is essential for realizing a highly stable SAE.

Conclusion

We investigated the impact of functional groups on the SOP formation of bent-shaped polar molecules and revealed that bulky alkyl and SO groups induced spontaneous molecular orientation during deposition. This can be attributed to the polarizability of the functional groups. On the top surface during deposition, the introduced alkyl groups weakened the intermolecular interactions, inducing orientation toward the vacuum side. In contrast, the SO group is oriented toward the substrate side because of its high polarizability. Based on these results, we developed a bent-shaped polar molecule exhibiting a high GSP slope of +321 mV nm−1 for SO-2PItBu, using SO and tBu groups to control the polarizabilities of the head and tail groups. The findings of this study provide a basic understanding of the molecular orientation of organic amorphous films and universal strategies for designing SAE materials with high surface potentials.

Methods

Materials and general methods

All synthesis reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. All the synthesized compounds were purified by column chromatography. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained using a JNM-ECX400 NMR spectrometer (JEOL) at room temperature (Supplementary Figs. 24–41). The glass transition temperature was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a DSC7000X instrument (Hitachi). The absorption spectra of the organic films on a quartz glass substrate were measured using UV-2550 (Shimadzu). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained using micrOTOF-Q III (BRUKER).

Film preparation and surface potential measurements

Organic films of varying thicknesses for surface potential measurements were deposited directly on pre-cleaned 100-nm-thick ITO-coated glass substrates using physical vapor deposition. Vacuum deposition was performed under high vacuum at pressure levels <3.0 × 10−4 Pa at a monitored deposition rate using an in-house evaporation machine directly connected to the chamber mounted with a Kelvin probe. The deposition rate was controlled at 0.1 nm s−1. The surface potential was measured using the Kelvin probe method under vacuum and dark conditions (UHVKP020, K.P. Technology). For the basic measurement of the surface potentials to estimate the GSP slopes, the samples were transferred between the vacuum chamber and the measurement chamber without air exposure, and the film thickness was increased by vacuum deposition on top of the sample. Another vacuum chamber with a Ts control system was used to test the dependence of the GSP slope on Ts. After the film was prepared on an ITO substrate, the film samples were carried out of the deposition chamber to ambient air and immediately transferred to the chamber with a Kelvin probe to measure the surface potential. For this experiment, we prepared film samples of different thicknesses to estimate the GSP slope. To test the photostability of the SOP films, light irradiation of organic films deposited on an ITO substrate was performed through a quartz glass window mounted on a vacuum chamber. After the irradiation, the samples were transferred to the measurement chamber without exposure to air. For the thermal stability test, ITO substrates coated with an insulating layer based on a cross-linked benzocyclobutene (BCB) film were used to suppress charge injection into the organic films from the ITO electrode during stability tests. BCB (TCI) solution in toluene (5 wt%) was spin-coated on an ITO substrate at 3000 rpm for 50 s in an N2-filled glove box. The coated substrates were immediately annealed at 150 °C for 10 min, and subsequently at 250 °C for 3 h on a hot plate in a glove box. After cooling, the BCB-coated substrates were immediately transferred to a deposition chamber without exposure to air for vacuum deposition. After the deposition, the processed substrates were transferred to the glove box again and annealed at various temperatures for 15 min on a hot plate to test the thermal stability of the GSPs. The substrates were rapidly cooled after the annealing, and carried out of the glove box to ambient air to transfer to the chamber with a Kelvin probe. We confirmed that the GSP slopes of the films deposited on the BCB-coated substrate were comparable to those deposited on a bare ITO substrate. The thickness of the deposited film was estimated using a thickness meter (FR-ES, ThetaMetrisis). To measure the vibration-based generated current, a probe with a diameter of 4 mm of a KP measurement system was placed above a deposited organic film on an ITO substrate with a gap of ~1 mm, and the probe vibrated at a frequency of 59.2 Hz. The generated current was collected using an oscilloscope (EDUX1052A, Keysight) and a current/voltage amplifier (CA5351, NF).

X-ray analysis

XRR measurements were performed using a SmartLab (Rigaku) with Cu Kα radiation at 45 kV and 200 mA. Organic film samples were deposited on sapphire substrates for XRR measurements. The X-ray incident angle was scanned from 0.2° to 5.0° in steps of 0.002°, at a scan rate of 0.2° min−1. Out-of-plane XRD measurements were performed using a SmartLab. The X-ray incident angle was fixed at 0.15°, and the detector angle was scanned from 3° to 30°. Organic film samples (thickness: 100 nm) were deposited on ITO substrates for XRD measurements.

Calculation

The optimized molecular structures and permanent dipoles of the ground-state molecules were calculated at the B3LYP/6-31 G (d) level using the Gaussian 16 program package. For the calculation of atomic polarizabilities, after structural optimization using the B3LYP/6-311 G(3 d, 3p) level calculation, additional calculations were performed to generate the wavefunctions of the molecules under zero and static fields. Using the wavefunction files, the atomic dipole moments under the fields were calculated using the AIMAll software44. The polarizabilities were then calculated based on the change in the induced dipole moments with the applied fields.

Synthesis

6F-2PI

Phthalic anhydride (550 mg), 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)dianiline (561 mg), benzoic acid (410 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (6 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 20 min and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform-ethyl acetate) to afford 6F-2PI as a white solid in 75% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.99 (dd, J = 3.2, 5.5 Hz, 4H), 7.82 (dd, J = 3.2, 5.5 Hz, 4H), 7.57 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.01, 134.74, 132.73, 132.57, 131.65, 131.11, 125.93, 124.03, 122.69, 64.41.

FL-2PI

Phthalic anhydride (829 mg), 9,9-bis(4-aminophenyl)fluorene (946 mg), benzoic acid (683 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (10 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 20 min and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 10 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform-ethyl acetate) to afford FL-2PI as a white solid in 75% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.94 (m, 4H), 7.80 (s, 2H), 7.78 (m, 4H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H) 7.36 (m, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.37, 150.48, 145.53, 140.27, 134.51, 131.80, 130.41, 129.01, 128.08, 127.95, 126.50, 126.33, 123.87, 120.41, 65.13. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C41H25N2O4 609.1809; found 609.1813.

6H-2PI

Phthalic anhydride (626 mg), 4,4′-(propane-2,2-diyl)dianiline (316 mg), benzoic acid (520 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for an hour and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform-ethyl acetate) to afford 6H-2PI as a white solid in 83% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.95 (m, 4H), 7.78 (m, 4H), 7.38 (dd, J = 18.7, 9.1 Hz, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.48, 150.12, 134.48, 131.86, 129.44, 127.78, 126.13, 123.84, 43.11, 30.92. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C31H23N2O4 487.1652; found 487.1663.

CH-2PI

Phthalic anhydride (829 mg), 1,1-bis(4-aminophenyl)cyclohexane (746 mg), benzoic acid (683 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (10 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 20 min and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 10 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (hexane-ethyl acetate) to afford CH-2PI as a white solid in 79% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.95 (m, 4H), 7.78 (m, 4H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.7 Hz), 2.34 (br, 4H), 1.62 (br, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.44, 148.00, 134.44, 131.86, 129.21, 128.10, 126.17, 123.82, 46.29, 37.27, 26.36, 22.89. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C34H27N2O4 527.1965; found 527.1985.

SO-2PI

Phthalic anhydride (623 mg), bis(4-aminophenyl) sulfone (347 mg), benzoic acid (514 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 20 min and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform-ethyl acetate) to afford SO-2PI as a white solid in 40% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.30 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 4H), 7.98 (m, 4H), 7.82 (m, 4H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 166.68, 139.84, 136.86, 135.23, 131.57, 128.49, 128.20, 123.91. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C28H17N2O6S 509.0802; found 509.0817.

6F-2PIMe

4-Methylphthalic anhydride (675 mg), 4,4’-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)dianiline (468 mg), benzoic acid (514 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for an hour and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform) to afford 6F-2PIMe as a white solid in 76% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.86 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (s, 2H), 7.57 (m, 10H), 2.57 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.08, 166.95, 146.06, 135.20, 132.70, 132.33, 131.90, 130.94, 128.93, 125.76, 124.38, 123.82, 64.00, 22.05. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C33H21F6N2O4 623.1400; found 623.1405.

6F-2PItBu

4-tert-Butylphthalic anhydride (858 mg), 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene)dianiline (468 mg), benzoic acid (513 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for an hour and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform) to afford 6F-2PItBu as a white solid in 87% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.10 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H), 7.99 (s, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.83 (dd, J = 1.8, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 4H), 1.40 (s, 18H). 13 C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.01, 134.74, 132.73, 132.57, 131.65, 131.11, 125.93, 124.03, 122.69, 64.41. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C39H33F6N2O4 707.2339; found 707.2350.

SODI-2CH

Cyclohexylamine (277 mg), 5,5′-sulfonylbis(isobenzofuran-1,3-dione) (501 mg), benzoic acid (341 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 5 h and subsequently stirred at 100 °C for 10 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform) to afford SODI-2CH as a white solid in 88% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.36 (s, 2H), 8.34 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (t, 2H), 2.16 (q, J = 12 Hz, 4H), 1.87 (d, J = 13 Hz, 4H), 1.70 (d, J = 13 Hz, 6H), 1.31 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.45, 166.28, 146.05, 136.25, 133.56, 133.36, 124.43, 122.81, 51.70, 29.79, 25.96, 25.04. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C28H29N2O6S 521.1741; found 521.1736.

SO-2PItBu

4-tert-Butylphthalic anhydride (855 mg), bis(4-aminophenyl) sulfone (348 mg), benzoic acid (515 mg), and molecular sieve were added to 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (5 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for an hour and subsequently stirred at 150 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was washed with water. The precipitate was dried under vacuum, and purified by chromatography on silica gel (chloroform-ethyl acetate) to afford SO-2PItBu as a white solid in 80% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.10 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.99 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.83 (dd, J = 1.8, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.04, 159.85, 139.97, 136.66, 132.06, 131.67, 128.79, 126.61, 124.04, 131.35, 36.01, 31.23. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd. for C36H33N2O6S 621.2054; found 621.2050.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ito, E. et al. Spontaneous buildup of giant surface potential by vacuum deposition of Alq3 and its removal by visible light irradiation. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 7306–7310 (2002).

Tanaka, Y., Matsuura, N. & Ishii, H. Self-assembled electret for vibration-based power generator. Sci. Rep. 10, 6648 (2020).

Tanaka, Y., Matsuura, N. & Ishii, H. Current generation mechanism in self-assembled electret-based vibrational energy generators. Sens. Mater. 34, 1859 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Effect of end group of amorphous perfluoro-polymer electrets on electron trapping. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 19, 486–494 (2018).

Kim, S., Suzuki, K. & Suzuki, Y. Development of a high-performance amorphous fluorinated polymer electret based on quantum chemical analysis. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1407, 012031 (2019).

Kim, S., Melnyk, A., Andrienko, D. & Suzuki, Y. Solid-state electron affinity analysis of amorphous fluorinated polymer electret. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 10507–10513 (2020).

Suzuki, Y. Recent progress in MEMS electret generator for energy harvesting. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 6, 101–111 (2011).

Tanaka, M., Auffray, M., Nakanotani, H. & Adachi, C. Spontaneous formation of metastable orientation with well-organized permanent dipole moment in organic glassy films. Nat. Mater. 21, 819–825 (2022).

Cakaj, A., Schmid, M., Hofmann, A. & Brütting, W. Controlling spontaneous orientation polarization in organic semiconductors—the case of phosphine oxides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 54721–54731 (2023).

Wang, W.-C., Nakano, K., Hashizume, D., Hsu, C.-S. & Tajima, K. Tuning molecular conformations to enhance spontaneous orientation polarization in organic thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 18773–18781 (2022).

Isoshima, T. et al. Negative giant surface potential of vacuum-evaporated tris(7-propyl-8-hydroxyquinolinolato) aluminum(III) [Al(7-Prq)3] film. Org. Electron. 14, 1988–1991 (2013).

Tanaka, M. Boosting spontaneous orientation polarization of polar molecules based on fluoroalkyl and phthalimide units. Nat. Commun. 15, 9297 (2024).

He, S., Pakhomenko, E. & Holmes, R. J. Process engineered spontaneous orientation polarization in organic light-emitting devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 1652–1660 (2023).

Yokoyama, D., Setoguchi, Y., Sakaguchi, A., Suzuki, M. & Adachi, C. Orientation control of linear‐shaped molecules in vacuum‐deposited organic amorphous films and its effect on carrier mobilities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 386–391 (2010).

Bagchi, K., Gujral, A., Toney, M. F. & Ediger, M. D. Generic packing motifs in vapor-deposited glasses of organic semiconductors. Soft Matter 15, 7590–7595 (2019).

Bagchi, K. et al. Origin of anisotropic molecular packing in vapor-deposited Alq3 glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 164–170 (2019).

Fiori, M. E., Bagchi, K., Toney, M. F. & Ediger, M. D. Surface equilibration mechanism controls the molecular packing of glassy molecular semiconductors at organic interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2111988118 (2021).

Bishop, C. et al. Vapor deposition of a nonmesogen prepares highly structured organic glasses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 21421–21426 (2019).

Osada, K. et al. Observation of spontaneous orientation polarization in evaporated films of organic light-emitting diode materials. Org. Electron. 58, 313–317 (2018).

Jäger, L., Schmidt, T. D. & Brütting, W. Manipulation and control of the interfacial polarization in organic light-emitting diodes by dipolar doping. AIP Adv 6, 095220 (2016).

Cassidy, A., McCoustra, M. R. S. & Field, D. A spontaneously electrical state of matter. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 1909–1919 (2023).

Friederich, P., Rodin, V., von Wrochem, F. & Wenzel, W. Built-in potentials induced by molecular order in amorphous organic thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 1881–1887 (2018).

Ueda, Y., Tanaka, M., Nakanotani, H. & Adachi, C. A polar transition of spontaneous orientation polarization in organic amorphous thin films. Chem. Phys. Lett. 833, 140915 (2023).

Tanaka, M., Noda, H., Nakanotani, H. & Adachi, C. Molecular orientation of disk-shaped small molecules exhibiting thermally activated delayed fluorescence in host–guest films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 023302 (2020).

Tanaka, M., Chan, C.-Y., Nakanotani, H. & Adachi, C. Simultaneous control of carrier transport and film polarization of emission layers aimed at high-performance OLEDs. Nat. Commun. 15, 5950 (2024).

Schmid, M. et al. Optical and electrical measurements reveal the orientation mechanism of homoleptic Iridium-Carbene complexes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 51709–51718 (2020).

Dalal, S. S., Walters, D. M., Lyubimov, I., de Pablo, J. J. & Ediger, M. D. Tunable molecular orientation and elevated thermal stability of vapor-deposited organic semiconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 4227–4232 (2015).

Komino, T., Tanaka, H. & Adachi, C. Selectively controlled orientational order in linear-shaped thermally activated delayed fluorescent dopants. Chem. Mater. 26, 3665–3671 (2014).

Komino, T., Nomura, H., Koyanagi, T. & Adachi, C. Suppression of efficiency roll-off characteristics in thermally activated delayed fluorescence based organic light-emitting diodes using randomly oriented host molecules. Chem. Mater. 25, 3038–3047 (2013).

Margenau, H. Van der waals forces. Rev. Mod. Phys. 11, 1–35 (1939).

Miller, K. J. Additivity methods in molecular polarizability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 8533–8542 (1990).

Ligorio, R. F., Rodrigues, J. L., Zuev, A., Santos, L. H. R. D. & Krawczuk, A. Benchmark of a functional-group database for distributed polarizability and dipole moment in biomolecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 29495–29504 (2022).

Noguchi, Y., Tanaka, Y., Ishii, H. & Brütting, W. Understanding spontaneous orientation polarization of amorphous organic semiconducting films and its application to devices. Synth. Met. 288, 117101 (2022).

Ma, Z., Geng, H., Wang, D. & Shuai, Z. Influence of alkyl side-chain length on the carrier mobility in organic semiconductors: herringbone vs. pi–pi stacking. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 4546–4555 (2016).

Moon, C.-K., Kim, K.-H. & Kim, J.-J. Unraveling the orientation of phosphors doped in organic semiconducting layers. Nat. Commun. 8, 791 (2017).

Schmidt, W. G. et al. Organic molecule adsorption on solid surfaces: chemical bonding, mutual polarisation and dispersion interaction. Appl. Phys. A 85, 387–397 (2006).

Yokoyama, D., Sakaguchi, A., Suzuki, M. & Adachi, C. Horizontal orientation of linear-shaped organic molecules having bulky substituents in neat and doped vacuum-deposited amorphous films. Org. Electron. 10, 127–137 (2009).

Frischeisen, J., Yokoyama, D., Endo, A., Adachi, C. & Brütting, W. Increased light outcoupling efficiency in dye-doped small molecule organic light-emitting diodes with horizontally oriented emitters. Org. Electron. 12, 809–817 (2011).

Yokoyama, D. Molecular orientation in small-molecule organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 19187–19202 (2011).

Chan, C.-Y. et al. Stable pure-blue hyperfluorescence organic light-emitting diodes with high-efficiency and narrow emission. Nat. Photonics 15, 203–207 (2021).

Sahay, P. et al. Effect of tert -butyl substitution on controlling the orientation of TADF emitters in guest–host systems. J. Mater. Chem. C 12, 11041–11050 (2024).

Noguchi, Y., Sato, N., Miyazaki, Y. & Ishii, H. Light- and ion-gauge-induced space charges in tris-(8-hydroxyquinolate) aluminum-based organic light-emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 143305 (2010).

Wang, W.-C. et al. Stable spontaneous orientation polarization by widening the optical band gap with 1,3,5,7-tetrakis(1-phenyl-1 H -benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)adamantane. J. Mater. Chem. C 11, 13039–13046 (2023).

AIMAll (Version 19.10.12), Todd A. Keith, TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park KS, USA, 2019 (aim.tkgristmill.com).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by JST FOREST Program (JPMJFR223S), JSPS KAKENHI (23K13716), Mazda Foundation, Inamori Foundation, and Asahi Glass Foundation. The authors thank Prof. Takahiro Ichikawa of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology for experimental assistance. The XRD, NMR, and HRMS measurements were performed at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology for the Research Center for Science and Technology. We thank Prof. Keiichi Noguchi and the members of the Research Center for Science and Technology of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology for their technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. conceived and designed this project. M.T. and R.S. prepared the materials and films and evaluated their properties. M.T. performed the DFT calculations. M.T., R.S., and N.N. contributed to writing the manuscript and critically commented on the project. M.T. and R.S. contributed equally to this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Kouki Akaike and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, M., Sugimoto, R. & Nakamura, N. Spontaneous orientation polarization driven by designing molecular asymmetry. Commun Mater 6, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00815-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00815-1