Abstract

Cement production contributes to >6% of global greenhouse gas emissions, driven by clinker’s energy-intensive production and limestone calcination. Replacing clinker with alternative substitutes is an effective decarbonization strategy. However, typical clinker substitutes—coal fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag—face current and future supply constraints. Here we systematically map reactivity variations and expand the repertoire of secondary and natural cementitious precursors. Large language models extract chemical compositions and material types of 14,000 materials from 88,000 academic papers. A multi-headed neural network predicts three reactivity metrics—heat release, Ca(OH)2 consumption, and bound water—based on chemical composition, median particle size, specific gravity, and amorphous/crystalline phase content, providing a unified assessment of cementitious reactivity and pozzolanicity. Subject to performance constraints, current supply allows for substituting half of global cement production with construction and demolition wastes and municipal solid waste incineration ash, reducing the global greenhouse gas emissions by 3%, equivalent to removing 260 million vehicles from the roads in the United States. Nearly 5–25% of 20 rock types, including ignimbrite, silicic tuff, pumice, shale, and rhyolite, are found to be reactive with heat release >200 J/g. The identified natural precursors, available worldwide in seismic and rift zones, show promise as clinker substitutes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is the world’s most widely used building material, with an average annual per capita consumption of three tonnes. Cement and additives bind aggregates and sand through a hydration process, transforming the mixture into hardened concrete. Over the past seven decades, cement production has increased tenfold1, driven by infrastructure demands and population growth, and is projected to rise another 20% by 20502,3. Cement production alone accounts for over 6% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)3,4,5, primarily due to cement clinker production, which involves high temperatures (above 950 ∘C) and the calcination reaction of limestone (CaCO3 → CaO + CO2)3,6.

Clinker substitution and binder replacement are priority strategies among a suite of approaches to reduce the GHG intensity of cement and concrete systems. The most common binder, ordinary portland cement, contains over 90% clinker by mass3. Clinker substitutes are cementitious precursors—materials that undergo chemical reactions with water and produce cement-like hydration products. Typical clinker substitutes, fly ash from coal combustion and ground granulated blast furnace slag from steel production, can replace up to 50% of clinker mass, while maintaining mechanical performance, potentially reducing GHG intensity by 50%7,8,9. It is technically feasible to replace up to 80% of clinker by mass with ground granulated blast furnace slag, achieving 28-day compressive strengths over 40 MPa10,11 and surpassing the minimum strength requirement for general construction12.

Currently, supply limitations and variations in the reactivity of substitute materials hinder the effectiveness of clinker substitution strategies. The availability of traditional clinker substitutes has decreased by 37% over the past two decades, dropping from 25% to 17% of total cement production13. This decline is driven partially by the decline of coal-based energy production and increased steel recycling13. Regional variations in the generation and distribution of these materials further limit clinker substitution14,15. Secondary substitutes (e.g., biomass ashes, coal bottom ash, milled waste glass powder, and municipal solid waste incineration ash) vary in material characteristics and reactivity based on how they were generated16,17,18,19, and their supply experiences seasonal and regional fluctuations20. Natural volcanic (e.g., pumice, zeolite) and sedimentary (e.g., clays, shales) clinker substitutes also exhibit spatial variability in chemical compositions16,21,22,23 and the degree of reactivity16. Beyond these general challenges, individual emerging substitutes face their own limitations. For instance, producing calcined clay from abundant kaolinitic clays requires calcination at 700–850 ∘C24. The GHG emissions reduction potential is limited to 20–30% when replacing 30% of clinker by mass with calcined clays24,25.

Cement and Concrete Industry’s roadmap to net-zero aims to reduce the global clinker-to-cement mass ratio from 76% to 52% by 205026,27. Achieving this goal hinges on broadening access to clinker substitutes by controlling reactivity of heterogeneous cementitious precursors and establishing a flexible supply of these constituents. Variations in intrinsic physicochemical factors—such as fineness and mineralogy—and extrinsic factors—such as temperature, pore solution alkalinity, and water content—affect reactivity28,29,30. Currently, reactivity assessments rely on time-intensive and resource-intensive experimental tests31,32. While experimental validation remains essential, computational models can streamline the initial screening of substitute materials and assess reactivity variations, thereby enabling a flexible supply chain. Thermodynamic, kinetic, and hydration simulation models can predict cement reactivity but may be computationally demanding or data-dependent and recalibration may be required for new cements or markedly different mix proportions of paste33,34. Molecular modeling of constituent behavior focuses on resulting structural properties rather than reaction kinetics. Previous machine learning approaches are limited to a subset of possible substitute materials, as detailed in Supplementary Information A. Consequently, achieving a comprehensive understanding of reactivity variations and the systematic identification of cementitious materials remains of interest.

We present a data-driven, machine learning method to predict the reactivity of cementitious precursors, providing insights into reactivity variations across different materials. We systematically map the reactivity variations of materials used in concrete from the literature and uncover regional potential for clinker substitution by expanding the pool of secondary and natural cementitious precursors. Fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) extract chemical compositions from over 14,000 previously used cement and concrete materials and classify them into 19 predefined types. Subsequently, a multi-task representation learning model, trained on data from 318 materials, simulates the rapid, relevant, and reliable (R3)35,36,37 test, a standard experimental assessment of chemical reactivity based on chemical composition, median particle size, specific gravity, mix proportions, and amorphous/crystalline phase content. This multi-headed neural network predicts reactivity and pozzolanicity without physical lab tests within 19 pre-defined material types.

By applying our model to both the literature-derived dataset and an extensive dataset of over one million rock samples, we characterize the reactivity variations and propose potential alternative secondary and natural precursors. Our study identifies potential clinker substitutes, including landfilled fly ashes, non-ferrous metallurgical slags, various biomass ashes (rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, wood, tree bark, palm oil fuel ash), construction and demolition wastes (ceramics, bricks, concrete), waste glass, municipal solid waste incineration ashes, and mine tailings (iron ore, copper, zinc). Among natural rock samples, 25 igneous rock types are identified to be potentially reactive with heat release exceeding 500 J/g. The widespread distribution of these precursors in tectonically active regions like the Andes, Great rift valley, and Appalachian mountains underscores their global accessibility. Incorporating these locally available, raw resources into cement and cement-based products solely through grinding can significantly reduce the GHG intensity by eliminating thermal activation.

Results

LLM-based literature mining and potential precursors

We mined the literature to identify and extract 14,434 materials, along with their chemical compositions and types, from 4312 journal papers on cement and concrete. Relevant papers were selected using keyword filtering on ~5.7 million journal publications collected through a streamlined extraction pipeline38. Chemical compositions were extracted using a fine-tuned LLM from XML tables, as detailed in “Table extraction of chemical compositions”. An additional fine-tuned LLM then classified these materials into 19 predefined types (e.g., mine tailings) and subtypes based on the journal data, as described in “Hierarchical classification of material types”. The CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 ternary diagram, where the sum of these three components exceeds 80 wt%, is shown in Fig. 1a. Most materials, except mine tailings and some cements, exhibit low Al2O3, high CaO, and lower SiO2, with a concentration along the CaO-SiO2 axis. Notably, 56% of samples contain 15–70 wt% CaO, 73% have 15–70 wt% SiO2, and 70.51% contain less than 15 wt% Al2O3. Nearly all samples (94.52%) have 0–15 wt% Fe2O3, and over 95% contain less than 10 wt% MgO. Our study builds on previous work39 by classifying 12,898 materials into 19 types, compared to 7490 materials into 11 types previously. We now include 2028 fly ash and 1346 slag samples, compared to 725 fly ash and 828 slag samples in earlier studies, and emerging types, like natural pozzolans, biomass ashes, and mine tailings are considered in the extracted data. The use of LLMs also allowed for the extraction of both material types (e.g., mine tailings) and subtypes (e.g., copper), enabling more detailed analyses.

a CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 ternary diagram of the extracted materials (CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 > 80%wt) in the present work, colored by material types. Below/beside each category label, the numbers represent the ratio of samples to unique papers, indicated as samples/papers. Yellow markers indicate materials with an unspecified category. b t-SNE plot of the extracted potentially cementitious precursors (CaO + Al2O3 + SiO2 > 80%wt) in this study, colored by material types. c Box-and-whisker plot of oxide compositions of material types; upper and lower whiskers represent the 95% range, while the boxes indicate the interquartile range (IQR), with the mean and median shown as straight and dashed lines; metakaolin, clays and calcined clay, while types of natural pozzolan, were represented separately in the plots. C& D, construction and demolition.

While chemical composition can partially indicate material types, its direct relationship with reactivity is unclear. To explore the compositional variation of cementitious precursors, we visualize dimensionality reduction through t-SNE analysis on materials with a combined CaO, Al2O3, and SiO2 content greater than 80 wt%, (Fig. 1b). The results show distinct clusters for many materials, except mine tailings, biomass ashes, and glasses. Cements also do not separate distinctly from inert lime species. This suggests the limits of using chemical composition alone to predict reactivity, as both reactive and inert materials can appear similar. To improve reactivity prediction, factors like particle size and amorphous content have been considered40,41,42.

Predicting reactivity through machine learning

Machine learning techniques have shown great potential in material discovery to predict properties of previously unseen materials43,44. In the context of cementitious precursors, the immense number of potential candidates—over 13,000 secondary materials with unique chemical compositions and more than 6000 naturally occurring mineral types with diverse physicochemical properties45—renders traditional experimental testing impractical due to the considerable time and resources required. To overcome this, a machine learning model was developed to evaluate the reactivity of investigated materials.

Three reactivity metrics derived from the R3 test35,36,37 were predicted: (1) Heat release: Measures the extent of chemical reactivity during the hydration of the material in a calcium-alkali-sulfate/carbonate mixture at specific time and temperature conditions using isothermal calorimetry. (2) Ca(OH)2 consumption: Quantifies pozzolanicity by assessing the amount of Ca(OH)2 consumed during hydration. In a pozzolanic reaction, amorphous SiO2 and Al2O3 chemically react with (Ca(OH)2) and water to form calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H) and calcium aluminate hydrates (C-A-H)46. Therefore, the consumption of (Ca(OH)2) indicates the degree of pozzolanicity. (3) Bound water: Evaluates the water chemically combined within solid phases or physically adsorbed on surfaces, serving as an alternative measure of reactivity similar to heat release. Since not all laboratories have access to isothermal calorimeters, bound water provides a possible proxy for assessing reactivity. A linear relationship between heat release and bound water was found (Supplementary Information B). This enables the conversion of bound water predictions into heat release estimates, thereby triangulating reactivity assessments for more accurate evaluations.

Chemical composition, median particle size, amorphous content, and specific gravity were used as material descriptors for reactivity prediction. Due to limited reactivity data, experimental results from the R3 test35,36 and its modified version37 were combined to create a comprehensive training dataset. This required devising descriptors to capture variations in paste ingredients, alkaline solutions, and curing conditions, such as Ca(OH)2, CaCO3, water, K2SO4, KOH, curing temperature, and age. The dataset includes 318 materials and 1850 data points: 1330 for heat release, 208 for Ca(OH)2 consumption, and 292 for bound water.

To enhance prediction accuracy despite data scarcity, a multi-headed neural network with a customized weighted loss function was developed. An imputation method using light gradient-boosting machine (LightGBM)47 was also used to handle missing data and employed a mask alongside input descriptors to indicate whether a descriptor had been imputed. The multi-headed architecture leveraged cross-task transfer learning, allowing hidden layers to represent shared descriptors across different reactivity metrics. This imputation aware, multi-task representation learning model provided a proxy for the R3 test. Compared to other machine learning models such as support vector machine48, random forest49, XGBoost50, and single-headed neural networks51, the presenting model achieved lower root mean square errors and prediction intervals for all three prediction targets: 28.20 J/g and 3.88 J/g for heat release, 12.17 g/100 g and 4.25 g/100 g for Ca(OH)2 consumption, and 1.47 g/100 g and 0.45 g/100 g for bound water (refer to Supplementary Information C). Correlations between observed and predicted values exceeded 0.85 R2 values for the presenting model (Fig. 2a–c).

a–c Prediction vs. actual values of the three reactivity metrics: heat release, Ca(OH)2 consumption, and bound water. Magenta and gray lines represent the trend of test and train data points, respectively. d–f top ten contributing descriptors (descriptors), with gray bars representing chemical properties, yellow bars representing environmental descriptors, light blue bars representing physical properties, and magenta bars representing mix proportions of additional materials in the paste mix. g–i SHAP values of the top ten contributing material descriptors, where blue and red dots indicate low and high values; R2 represent Coefficient of determination indicating the goodness of fit; top contributing descriptors are identified from the permutation descriptor importance.

Permutation importance measures the increase in a model’s prediction error when the values of a descriptor—a physical or chemical input feature—are randomly shuffled, thus assessing the model’s dependency on that specific descriptor52. The top contributing reactivity predictors identified through permutation for all three output targets include major oxides (CaO, Al2O3, SiO2, Fe2O3, and MgO), microstructural property of amorphous content, and the bulk physical property of specific gravity (Fig. 2d–f). Al2O3 and CaCO3 contents are the most impactful descriptors in predicting both heat release and bound water, both of which determine the degree of reactivity.

The model’s predictions and descriptor effects were interpreted and validated through SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis of the top contributing descriptors. SHAP, a game-theoretic method using Shapley values, allocates credit among descriptors, providing local explanations by quantifying each descriptor’s contribution to the prediction53. As shown in Fig. 2g–i, the degree of reactivity increases with extended sample age, reflecting ongoing hydration and exothermic heat release from hydration product formation29,54,55. Higher amorphous content enhances reactivity due to the lack of long-range atomic order, while crystalline phases are more chemically stable39,41,56,57,58. Additionally, increasing Al2O3 content boosts all three reactivity metrics, aligning with domain knowledge that higher Al2O3 accelerates more exothermic hydration, forming calcium aluminate hydrates, and promoting early strength development58,59. Materials with higher Al2O3 than other major oxides are typically highly reactive pozzolanic materials, as detailed in Supplementary Information D. SHAP analysis also indicates that increasing CaCO3 may increase both heat release and bound water. Higher CaCO3 levels increase heat release and the degree of reactivity due to the exothermic formation of additional carboaluminates and ettringite60. In addition, bound water increases as CaCO3, which is essentially anhydrous, transforms into hydrated phases, resulting in more water being bound60. Higher CaO content accelerates reaction rates and hydrate production61,62,63,64. Figure 2h shows that higher CaO reduces Ca(OH)2 consumption, indicating decreased pozzolanicity. The added CaO provides a readily available source of calcium ions, which directly react with silica and alumina to form calcium-bearing hydration products such as C-S-H. This direct reaction pathway significantly reduces the consumption of existing Ca(OH)2, as the added CaO fulfills much of the calcium needed for hydration product formation64,65. Lower specific gravity can increase the Ca(OH)2 consumption. The porous structure of low-density materials offers more nucleation and growth sites during the initial stages of hydration40. Furthermore, SHAP results reveal a relationship between heat release and bound water, with both exhibiting similar SHAP value trends across top contributing descriptors such as chemical compositions (Al2O3, SiO2), temporal variable (sample age), additional materials (CaCO3), and physical properties (specific gravity). This suggests that these descriptors similarly influence both heat release and bound water in cementitious systems.

Reactivity variation and upcycling potential of secondary materials

The predictive framework was applied to map the reactivity of secondary materials and assess their upcycling potential for clinker substitution. The chemical compositions of the extracted materials, as detailed in “LLM-based literature mining and potential precursors”, formed the basis for predicting their reactivity. The model described in “Predicting reactivity through machine learning” also requires additional descriptors, such as amorphous content and specific gravity. These parameters were permuted as described in “Imputation method”. Additionally, for each material type, the median particle size was set by averaging the median particle sizes from the dataset used to train and test the reactivity model. Figure 3a shows the materials in reactivity space (heat release, Ca(OH)2 consumption), while Fig. 3b displays reactivity variations separated by material type. Pozzolanic materials are generally observed to consume over 50 g/100 g of Ca(OH)2. In addition, inert materials tend to release less than 100 J/g heat37. Slags typically exhibit hydraulic behavior, resulting in low Ca(OH)2 consumption, while fly ashes demonstrate pozzolanic behavior with high Ca(OH)2 consumption. Natural pozzolans, silica fume, and some clays, glasses, and mine tailings are also found to be reactive. Conversely, calcium species are classified as inert, exhibiting minimal heat release. Biomass ashes, construction waste, and bottom ashes show potential for pozzolanic reactivity. The results align with previous studies37,66,67.

a Heat release versus Ca(OH)2 consumption for the pre-defined material types b reactivity variation in the reactivity space of 18 various material types. Colorscale with saturation of 1 as 100% and white as no frequency, and contour showing the density of frequency. Gray horizontal and vertical lines indicate the thresholds distinguishing inert from reactive materials based on heat release (120 j/g), and identifying pozzolanic or hydraulic behavior based on Ca(OH)2 consumption (50 g/100 g). c–h variations further in subtypes of materials: coal fly ashes, slags, biomass ashes, construction and demolition wastes and waste glass, other ashes, and mine tailings + refinery residue (bauxite residue). In (a), annotations of each color for material types are given in Fig. 1. In (c–g), KDE density of each subtype are plotted on the axes. MSWI, municipal solid waste incineration.

While the previous section provided a broad overview of reactivity trends across material types, a more detailed investigation into specific subtypes is essential to fully assess their suitability for clinker substitution. To gain deeper insights into material reactivity and identify viable clinker substitutes, we categorized the materials within each type into subtypes based on their source or processing methods and evaluated the distinct reactivity profiles of these subtypes. Figure 3c–h shows the reactivity distribution of fly ashes, slags, biomass ashes, construction waste, non-coal ashes, and mine tailings categorized by their subtypes using LLMs. Class F fly ash shows more pozzolanic behavior than Class C, while slags and biomass ashes display varying reactivity. Among construction and demolition wastes, recycled ceramics, bricks, and concrete exhibit pozzolanic and hydraulic behavior, with waste ceramics showing heat releases up to 450 J/g. Mine tailings, such as copper and zinc, show diverse reactivity with heat releases up to 400 J/g. Limited studies on waste glasses68, harvested ashes69, and mine tailings70 highlight their potential as cementitious precursors.

Our supply analysis indicates that construction and demolition wastes and municipal solid waste can significantly substitute clinker in most investigated countries. A recent study showed that coal fly and bottom ashes, granulated blast furnace slag, and biomass, agricultural, and forestry ashes could collectively replace 53% of global cement production (19%, 12%, and 22%, respectively)13. This study further highlights that construction and demolition wastes and municipal solid waste could also contribute. Annually, 4 billion tons of construction and demolition wastes71, 600 million tons of municipal solid waste71 are generated, with the potential to replace part of the 4 billion tons of portland cement produced globally72. It was assumed that one ton of waste concrete, bricks, or tiles can produce up to 1 ton of binder. Electric arc furnace processing method73 can be used to reclinker hydrated cement paste in the recycled concrete. Under slow pyrolysis, one ton of waste wood can yield up to 800 kg of biochar74. Although this direct conversion produces a high mass yield, the resulting biochar often exhibits low intrinsic reactivity. However, when wood wastes are co-pyrolyzed with inorganic and green wastes, the resulting biochar can be transformed into a moderately reactive pozzolanic material, as indicated by Ca(OH)2 consumption and bound water values of ~17 g/100 g and ~60 g/100 g, respectively75. Construction and demolition wastes and municipal solid waste could replace 68% of global cement production (55% and 13%, respectively). While not all of these materials may be reactive, they can be activated through a variety of scalable, material-specific activation methods. Detailed data and assumptions regarding supply analysis are available in Supplementary Information E.

Discovery of natural cementitious precursors

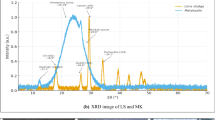

We hypothesize that potential cementitious rock types can be identified using the global whole-rock geochemical database76, which comprises 1,000,000 rock samples with chemical compositions and geospatial data. Based on reactivity predictions, rocks were classified into three levels: inert (120 J/g), low reactivity (120–200 J/g), and moderate-to-high reactivity (>200 J/g)66. The database lacks direct measurements of amorphous content—a key factor in reactivity—which must be imputed. The R3 dataset is predominantly composed of reactive materials with high amorphous content, while many rock types exhibit a broader range of amorphous contents and reactivity. To address this, we performed imputation across all features and compiled a literature dataset of ~160 rock samples with measured amorphous contents (ranging from 1.8% to 80%) to refine our approach. Using the method described in “Imputation method”, we imputed amorphous content and other input descriptors from R3 dataset augmented by the collected rock chemical composition-amorphous content dataset, resulting in 3.0% average error for the imputed amorphous content and a 5% average error in the degree of reactivity predictions. More details on the missingness rate of input descriptors and imputation performance are provided in Supplementary Information H.

Adopting mechanically activated natural cementitious precursors as substitutes for clinker offers a promising strategy for decarbonizing cement and concrete systems. Prediction models were applied to assess rock reactivity assuming a median particle size of 10 μm. From this analysis, we identified 50,569 natural precursors from over 1200 rock types with heat release exceeding 200 J/g, of which 25 rock types contain more than 5% reactive precursors. Figure 4a and b illustrate the abundance of samples with moderate-to-high reactivity and the reactive-to-total sample ratio of the rock types. Among these, anorthosite, an igneous rock, and ignimbrite, a pumice-dominated pyroclastic flow deposit, exhibit the highest reactive-to-total sample ratio (~25%). This is followed by porphyry (~22%), a rock type characterized by large volcanic crystals embedded in a finer-grained or glassy groundmass; clastic rocks (~21%), represent a broad category of sedimentary rocks formed by the cementation and lithification of mechanically weathered fragments (clasts); and silicic tuff (~21%), a widely known silica-rich natural pozzolan formed from consolidated volcanic ash. Although rhyolite, andesite, and dacite—extrusive volcanic rocks—display lower reactive-to-total ratios (<12%), they are more abundant across the globe, as evidenced by the higher number of reactive samples. Figure 4c shows the reactivity variations among the top five rock types with the highest reactive-to-total sample ratios or the largest number of reactive samples. Most of the identified reactive samples fall within the pozzolanic range, with Ca(OH)2 consumption greater than 50 g/100 g. In total, ~46,700 samples were classified as pozzolanic and ~ 3800 as hydraulic. The figure also highlights that the potential for high reactivity varies across rock types. For example, individual samples of anorthosite and rhyolite exhibit heat release values exceeding 500 J/g, whereas well-known natural pozzolans such as silicic tuff and pumice show upper bounds of about 400 J/g and 250 J/g, respectively.

a Reactive-to-total sample ratio for the 38 rock types exceeding a 5% threshold. b number of moderate-to-high reactivity samples for each rock type. c reactivity variations of selected rock types, chosen based on highest abundance or reactive-to-total ratio, colored by rock types. Below each label, the numbers represent the ratio of moderate-to-high reactive materials to the total number of rock samples of that type, indicated as reactive samples/total samples. Each arrow points to the sample with the highest degree of reactivity. Yellow markers denote rock samples whose rock types were not selected. Geospatial distribution of identified reactive rocks within the globe with pozzolanic (d) and hydraulic (e) behavior. The number preceding each country indicates the number of unique locations with cementitious precursors, and the number in parentheses represents the percentage relative to the total identified locations. Geospatial distribution of discovered reactive rocks within the Northern America with pozzolanic (f) and hydraulic (g) behavior.

Identified natural precursors are distributed globally and concentrated in seismic, orogenic, and rift zones. Moderate and highly reactive can serve as raw substitutes for clinker supporting alternative cement production in regions with limited access to secondary precursors (Fig. 4d, e). Although most of the identified precursor locations are in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Japan, this likely reflects more extensive research and data availability in these regions rather than an exclusive distribution. In fact, these precursors occur worldwide. Volcanic precursors cluster in northern and central Europe (Baltic shield, Scafell pike), Asia (Japan, Taurus and Zagros mountains, Indian cratons, and Tibetan plateau), Africa (Great rift valley), Oceania (Great dividing range and Ancient cratons), and South America (Andes). Figure 4f, g further shows that, in North America, moderate and highly reactive precursors are primarily located in the Appalachian, Rocky mountains, Yellowstone, the East continent rift, and the Canadian shield.

Discussion

By mapping the reactivity of potential cementitious precursors, we identified material types that can broaden the pool of clinker substitutes across by-products and natural materials. Our analysis reveals distinct behaviors among material subtypes, driven by chemical composition. For instance, rice husk ash and sugarcane bagasse ash, two types of biomass ashes, act as pozzolanic precursors, while tree bark ash may function as a hydraulic precursor. Other reactive materials include municipal solid waste ashes, mine tailings, waste glass, and construction and demolition wastes, including recycled concrete and ceramics. Globally, the cement industry contributes over 2.5 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions annually26. Substituting half of global cement with construction and demolition waste and incinerator ash could save 1.2 billion metric tons of GHG emissions—equivalent to removing nearly 260 million vehicles from the roads in the United States77. For any material intended as a clinker substitute, critical properties including fresh-state workability, hardened-state performance, long-term durability, and environmental impacts (such as contaminant leaching) must be assessed.

Among 25 identified natural rock types, explicit literature indicates that eight exhibit reactive behavior upon mechanical activation. Ancient Roman builders harnessed naturally altered, alkali-rich ignimbrite in combination with quicklime to produce mortars for constructing landmarks such as the Forum and Markets of Trajan78. Frattini tests confirm that ignimbrites participate in pozzolanic reactions by consuming Ca(OH)2 and forming cementitious products even without thermal activation79. Ancient Romans also used tuffs and quicklime to construct bridges and brickwork80. Pumice is widely recognized as a natural pozzolan, exhibiting a heat release of ~ 200–250 J/g and consuming over 70 g of Ca(OH)2/100 g67. Global Cement and Concrete Association recognizes rhyolite as a natural pozzolan81. Opaline shales, an uncommon silica-rich sedimentary rock formed from microscopic siliceous organisms, contain a high proportion of amorphous or poorly crystalline silica (opal). Shales with high amount of opaline silica are recognized as raw natural pozzolans under ASTM C618 standard32. Andesite exhibited pozzolanic behavior as demonstrated by the Frattini test82, while trachyte, when used to replace 25% of cement, can achieve a strength activity index of ~ 90%—a performance comparable to that of granulated blast furnace slag83. Pyroclastic rocks, formed during explosive volcanic eruptions and composed primarily of volcanic ash, pumice, tuffs, are widely recognized as natural pozzolans. The documented reactivity of these materials, demonstrated through standardized tests or historical usage, provides directional evidence supporting the reliability of our method for identifying reactive, mechanically activated natural precursors in their raw form.

Crystalline rocks can develop cementitious reactivity through amorphization. For instance, anorthosite, a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock composed of more than 90% plagioclase feldspar (calcium/sodium aluminosilicates)84, could potentially serve as a promising cementitious material if rendered amorphous, possibly through vitrification85. Grinding may disrupt the crystalline lattice of plagioclase, leading to the broadening or disappearance of its sharp X-ray diffraction peaks, indicating the formation of an amorphous structure86. Clastic rocks are typically dominated by stable crystalline minerals (e.g., quartz, feldspars, clay); the apparent reactivity within this broad category likely reflects those samples containing silica-rich or volcaniclastic fragments with elevated amorphous content.

Identified natural precursors are found to be widely available in seismic regions and rift zones globally, addressing regional disparities in the availability of secondary substitutes and promoting more equitable access to sustainable construction materials. Successful industry adoption of clinker substitutes requires a thorough assessment of their reactivity performance, dynamic supply, and economic viability.

Experimental validations remain essential to confirm our data-driven predictions, ensuring reliability and fostering trust in the model’s capabilities. Future improvements could include as follows: Incorporating additional training data as it becomes available can significantly enhance the model’s generalizability. Integrating domain-specific knowledge, such as hydration kinetics, into future models can provide deeper insights, making the model more interpretable and useful for practical applications. This study advances reactivity-based prediction of concrete properties at paste, mortar, and concrete levels. Future iterations could be designed to model calcination, or vitrification activation pathways for natural materials, thereby providing a more comprehensive tool for optimizing material-specific activation strategies.

Methods

Table extraction of chemical compositions

We analyzed a corpus of 5.7 million journal papers, refining our focus to around 88,000 relevant papers on cement and concrete through keyword filtering. From these, we developed two vector databases—one for sentences and another for tables—storing data as high-dimensional vectors generated through embeddings. These vectors, representing around 3 million sentences and 104,000 XML tables, capture semantic relationships, enabling efficient and precise retrieval. Large language model (LLM) agents utilized a retrieval-augmented generation approach, combining embedding-based retrieval with language model generation to extract chemical compositions and material names. The embedding-based retrieval of tables utilized two general-purpose transformer models, all-mpnet-base-v287,88 and all-MiniLM-L6-v289,90, as well as a domain-specific embedding, MatSciBERT91. Based on the investigation detailed in Supplementary Information F, all-MiniLM-L6-v2 proved superior for embedding-based table retrieval and was subsequently employed for this purpose. Next, we used pre-trained closed-source models (GPT-3.592, GPT-493), open-source model, Mistral 7b94, and fine-tuned LLMs, GPT-3.5 and Mistral, and sequential LLM agents, to perform extraction from the retrieved tables. For fine-tuning, we manually created a ground-truth dataset from 200 randomly selected tables. Our comparative study showed that GPT-3.5 fine-tuned was optimal for the final generation step due to its good performance in terms of end-to-end time, detecting relevant tables for extraction, detecting materials in the table, and extracting numerical chemical compositions, as detailed in Supplementary Information G. Therefore, GPT-3.5 was used for the table extraction of chemical compositions.

Hierarchical classification of material types

To address the issue of non-descriptive material names and potential abbreviations in the extracted data, we implemented a two-step approach using our sentence vector database and metadata filtering to enhance the semantic understanding of materials. First, we utilized our sentence vector database to perform semantic searches, retrieving ten sentences that describe each material, previously identified by name from the tables. In the first step, we used the pre-trained Mistral 7b model to generate descriptive summaries for each material based on the retrieved sentences. In the second step, these summaries were input into a fine-tuned GPT-3.592 model to classify the materials into one of 19 pre-defined categories: cements, clinkers, fly ashes, slags, silica fume, calcium species (quicklime, limestone, chalk, and gypsum), bottom ashes, biomass ashes, glasses, natural pozzolans, clays, calcined clays, metakaolin, mine tailings, construction and demolition wastes, granite, other by-products/wastes, and other ashes. Although metakaolin is a type of calcined clay, and clays and calcined clays are natural pozzolans, we have chosen to categorize them separately to facilitate a more detailed investigation. The fine-tuned model generates specific subtypes to best describe the material. For fine-tuning the GPT-3.5 model, we manually created a ground-truth dataset from 200 randomly selected materials, which had previously been extracted by another fine-tuned LLM responsible for extracting chemical compositions and material names. Manual validation of the fine-tuned language model’s responses confirmed a classification accuracy of 97%, indicating the model’s effectiveness.

Imputation-aware multi-task neural network

To address the challenge of handling missing values while predicting multiple reactivity metrics simultaneously, we devised an imputation-aware multi-task neural network. This network employs two distinct approaches for managing missing values in inputs and outputs. For outputs, custom loss functions were designed to account only for non-missing entries, ensuring that the loss calculation is based solely on valid data. For inputs, we developed a dual approach: imputing missing values and creating masks via concatenation to indicate the presence of imputed data, thereby allowing the network to differentiate between original and imputed values during training, as discussed in “Imputation method”. The model architecture integrates these input descriptors and their corresponding masks through concatenation, enabling the network to recognize and appropriately handle imputed values. The optimized neural network structure consists of four dense layers with ReLU activations, interspersed with a dropout layer to mitigate overfitting and batch normalization layers to improve training stability. The loss weights for the different outputs are inversely proportional to the number of available data points for each metric, ensuring balanced contributions from each metric during training. For hyperparameter tuning, we utilized Keras Tuner95 to optimize parameters such as the choice of optimizer, learning rate, number of layers, and units per layer, ensuring the best-performing model configuration for our dataset. Early stopping was employed during training to avoid overfitting, monitoring the validation loss and restoring the best model weights accordingly.

Imputation method

A robust imputation approach based on multiple imputation by chained equations96 was implemented using scikit-learn’s IterativeImputer97 in combination with a custom-wrapped LightGBM model47. This method iteratively estimates and replaces missing values by leveraging the complex relationships among descriptors. Specifically, a dedicated LightGBM model was trained for each descriptor with missing values, using the other descriptors as predictors, and then used to impute missing data based on the learned relationships. Grid search was used to fine-tune the hyperparameters of each imputation model, and 5-fold cross-validation was conducted during hyperparameter tuning to ensure robustness and avoid overfitting. We combined the three datasets—derived from literature mining, reactivity metrics prediction, and the amorphous content of natural rocks—for imputation. Missingness rates and imputation error obtained for this method are provided in Supplementary Information H.

Machine learning software tools

Machine learning regression models were implemented using Python v3.8.8 with the following packages: Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, LightGBM, Pandas, and NumPy.

LLM software tools

LLMs were implemented using Python v3.8.8 with the aid of the following packages: OpenAI, PyTorch, Ludwig, LangChain, SentenceTransformers, and PyMongo.

Code availability

All code used in this study are publicly available at the GitHub repository: https://github.com/olivettigroup/Cementitious-reactivity-prediction-and-discovery.

References

United Nations Environment Programme, Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction (UNEP, 2022).

Cheng, D. et al. Projecting future carbon emissions from cement production in developing countries. Nat. Commun. 14, 8213 (2023).

International Energy Agency. Technology roadmap: Low-carbon transition in the cement industry (2018).

Summerbell, D. L., Barlow, C. Y. & Cullen, J. M. Potential reduction of carbon emissions by performance improvement: a cement industry case study. J. Clean. Prod. 135, 1327–1339 (2016).

Korczak, K., Kochański, M. & Skoczkowski, T. Mitigation options for decarbonization of the non-metallic minerals industry and their impacts on costs, energy consumption and ghg emissions in the eu-systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 358, 132006 (2022).

Cavalett, O., Watanabe, M. D., Voldsund, M., Roussanaly, S. & Cherubini, F. Paving the way for sustainable decarbonization of the european cement industry. Nat. Sustain. 1–13 (2024).

Güneyisi, E. & Gesoğlu, M. A study on durability properties of high-performance concretes incorporating high replacement levels of slag. Mater. Struct. 41, 479–493 (2008).

Berryman, C., Zhu, J., Jensen, W. & Tadros, M. High-percentage replacement of cement with fly ash for reinforced concrete pipe. Cem. Concr. Res. 35, 1088–1091 (2005).

Orozco, C., Babel, S., Tangtermsirikul, S. & Sugiyama, T. Comparison of environmental impacts of fly ash and slag as cement replacement materials for mass concrete and the impact of transportation. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 39, e00796 (2024).

Sethy, K. P., Pasla, D. & Sahoo, U. C. Utilization of high volume of industrial slag in self compacting concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 581–587 (2016).

Wainwright, P. & Rey, N. The influence of ground granulated blastfurnace slag (ggbs) additions and time delay on the bleeding of concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 22, 253–257 (2000).

American Concrete Institute. ACI CODE-318-19(22): Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary, 19th edn. (American Concrete Institute, 2022).

Shah, I. H., Miller, S. A., Jiang, D. & Myers, R. J. Cement substitution with secondary materials can reduce annual global co2 emissions by up to 1.3 gigatons. Nat. Commun. 13, 5758 (2022).

Habert, G. et al. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 559–573 (2020).

Abt, H. J. S. & Tisera, G. D. Supply chain network optimization for global distribution of cementitious materials (2018).

Juenger, M. C., Snellings, R. & Bernal, S. A. Supplementary cementitious materials: new sources, characterization, and performance insights. Cem. Concr. Res. 122, 257–273 (2019).

Kumar, V. & Garg, N. The chemical and physical origin of incineration ash reactivity in cementitious systems. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 177, 106009 (2022).

Cunningham, P. R., Wang, L., Thy, P., Jenkins, B. M. & Miller, S. A. Effects of leaching method and ashing temperature of rice residues for energy production and construction materials. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 3677–3687 (2021).

Snellings, R., Suraneni, P. & Skibsted, J. Future and emerging supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 171, 107199 (2023).

Schmidt, W. et al. Sustainable circular value chains: From rural waste to feasible urban construction materials solutions. Dev. Built Environ. 6, 100047 (2021).

Hamada, H. M., Abed, F., Beddu, S., Humada, A. & Majdi, A. Effect of volcanic ash and natural pozzolana on mechanical properties of sustainable cement concrete: a comprehensive review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02425 (2023).

Labbaci, Y., Abdelaziz, Y., Mekkaoui, A., Alouani, A. & Labbaci, B. The use of the volcanic powders as supplementary cementitious materials for environmental-friendly durable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 133, 468–481 (2017).

Lemougna, P. N. et al. Review on the use of volcanic ashes for engineering applications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 137, 177–190 (2018).

Scrivener, K., Martirena, F., Bishnoi, S. & Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (lc3). Cem. Concr. Res. 114, 49–56 (2018).

Cao, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Ma, Y. & Wang, H. Recent progress of utilization of activated kaolinitic clay in cementitious construction materials. Compos. Part B: Eng. 211, 108636 (2021).

Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). The GCCA 2050 cement and concrete industry roadmap for net zero concrete (2021).

Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA). Cement industry net zero progress report 2024/25 (2024).

Wang, T. & Ishida, T. Multiphase pozzolanic reaction model of low-calcium fly ash in cement systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 122, 274–287 (2019).

Blotevogel, S. et al. Ability of the r3 test to evaluate differences in early age reactivity of 16 industrial ground granulated blast furnace slags (GGBS). Cem. Concr. Res. 130, 105998 (2020).

Snellings, R. Refining kinetic models for scm reactivity in blended cements. In Proc. International RILEM Conference on Synergising Expertise Towards Sustainability and Robustness of CBMs and Concrete Structures, 34–42 (Springer, 2023).

ASTM International. Standard test methods for sampling and testing fly ash or natural pozzolans for use in portland-cement concrete, https://www.astm.org/Standards/C311.htm (2022).

ASTM International. Standard specification for coal fly ash and raw or calcined natural pozzolan for use in concrete https://www.astm.org/c0618-23e01.html (2023).

Thomas, J. J. et al. Modeling and simulation of cement hydration kinetics and microstructure development. Cem. Concr. Res. 41, 1257–1278 (2011).

Joseph, S. Experimental and Numerical Analysis on the Hydration of c3s/c3a Systems (Ph.D. Dissertation) (KU Leuven, 2018).

Avet, F., Snellings, R., Diaz, A. A., Haha, M. B. & Scrivener, K. Development of a new rapid, relevant and reliable (r3) test method to evaluate the pozzolanic reactivity of calcined kaolinitic clays. Cem. Concr. Res. 85, 1–11 (2016).

Londono-Zuluaga, D. et al. Report of rilem tc 267-trm phase 3: validation of the R3 reactivity test across a wide range of materials. Mater. Struct. 55, 142 (2022).

Suraneni, P. & Weiss, J. Examining the pozzolanicity of supplementary cementitious materials using isothermal calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis. Cem. Concr. Compos. 83, 273–278 (2017).

Kim, E. et al. Materials synthesis insights from scientific literature via text extraction and machine learning. Chem. Mater. 29, 9436–9444 (2017).

Uvegi, H. et al. Literature mining for alternative cementitious precursors and dissolution rate modeling of glassy phases. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 104, 3042–3057 (2021).

Skibsted, J. & Snellings, R. Reactivity of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMS) in cement blends. Cem. Concr. Res. 124, 105799 (2019).

Hertel, T., Van den Bulck, A., Blanpain, B. & Pontikes, Y. Correlating the amorphous phase structure of vitrified bauxite residue (red mud) to the initial reactivity in binder systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 127, 104410 (2022).

Kasaniya, M., Thomas, M. D. & Moffatt, E. G. Pozzolanic reactivity of natural pozzolans, ground glasses and coal bottom ashes and implication of their incorporation on the chloride permeability of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 139, 106259 (2021).

Raccuglia, P. et al. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 533, 73–76 (2016).

Wang, T. et al. Machine-learning-assisted material discovery of oxygen-rich highly porous carbon active materials for aqueous supercapacitors. Nat. Commun. 14, 4607 (2023).

Pushcharovsky, D. Y. Mineralogical crystallography: I. discovery, systematics, and evolution of minerals. Crystallogr. Rep. 68, S3–S17 (2023).

Neville, A. M. & Brooks, J. J. Concrete Technology 438 (Longman Scientific & Technical England, 1987).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Hearst, M. A., Dumais, S. T., Osuna, E., Platt, J. & Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 13, 18–28 (1998).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115–133 (1943).

Permutation feature importance. https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/permutation_importance.html

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Reactivity of unconventional fly ashes, scms, and fillers: effects of sulfates, carbonates, and temperature. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 11, 639–657 (2022).

Kupwade-Patil, K., Tyagi, M., Brown, C. M. & Büyüköztürk, O. Water dynamics in cement paste at early age prepared with pozzolanic volcanic ash and ordinary portland cement using quasielastic neutron scattering. Cem. Concr. Res. 86, 55–62 (2016).

Rimstidt, J. D. & Barnes, H. The kinetics of silica-water reactions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 44, 1683–1699 (1980).

Snellings, R. Assessing, understanding and unlocking supplementary cementitious materials. RILEM Tech. Lett. 1, 50–55 (2016).

Cristelo, N., Tavares, P., Lucas, E., Miranda, T. & Oliveira, D. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of the amorphous phase of a class F fly ash dissolved during alkali activation reactions–effect of mechanical activation, solution concentration and temperature. Compos. Part B Eng. 103, 1–14 (2016).

Kucharczyk, S., Deja, J. & Zajac, M. Effect of slag reactivity influenced by alumina content on hydration of composite cements. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 14, 535–547 (2016).

Matschei, T., Lothenbach, B. & Glasser, F. P. The role of calcium carbonate in cement hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 37, 551–558 (2007).

Mounanga, P., Khelidj, A., Loukili, A. & Baroghel-Bouny, V. Predicting ca(oh)2 content and chemical shrinkage of hydrating cement pastes using analytical approach. Cem. Concr. Res. 34, 255–265 (2004).

Moorehead, D. Cementation by the carbonation of hydrated lime. Cem. Concr. Res. 16, 700–708 (1986).

Wang, Y., Burris, L., Hooton, R. D., Shearer, C. R. & Suraneni, P. Effects of unconventional fly ashes on cementitious paste properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 125, 104291 (2022).

Kucharczyk, S. et al. Structure and reactivity of synthetic Cao-Al2O3-Sio2 glasses. Cem. Concr. Res. 120, 77–91 (2019).

Escalante-Garcia, J. Nonevaporable water from neat opc and replacement materials in composite cements hydrated at different temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 33, 1883–1888 (2003).

Suraneni, P., Hajibabaee, A., Ramanathan, S., Wang, Y. & Weiss, J. New insights from reactivity testing of supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 103, 331–338 (2019).

Ramanathan, S., Kasaniya, M., Tuen, M., Thomas, M. D. & Suraneni, P. Linking reactivity test outputs to properties of cementitious pastes made with supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 114, 103742 (2020).

Moradllo, M. K. et al. Use of borosilicate glass powder in cementitious materials: pozzolanic reactivity and neutron shielding properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 112, 103640 (2020).

Shakouri, M. et al. Enhancing physiochemical properties and reactivity of landfilled fly ash through thermo-mechanical beneficiation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 144, 105310 (2023).

Ramanathan, S., Perumal, P., Illikainen, M. & Suraneni, P. Mechanically activated mine tailings for use as supplementary cementitious materials. RILEM Tech. Lett. 6, 61–69 (2021).

World Bank. What a waste global database https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0039597/What-a-Waste-Global-Database (2024).

United States Geological Survey. Cement Statistics and Information https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/cement-statistics-and-information (2024).

Dunant, C. F., Joseph, S., Prajapati, R. & Allwood, J. M. Electric recycling of portland cement at scale. Nature 1–7 (2024).

Safarian, S. Performance analysis of sustainable technologies for biochar production: a comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 9, 4574–4593 (2023).

Mayer, M., Ukrainczyk, N. & Koenders, E. R3 reactivity test on biochar from pyrolyzed green waste, wood waste, and screen overflow. In Kioumarsi, M. & Shafei, B. (eds.) The 1st International Conference on Net-Zero Built Environment, 563–573 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2025).

Gard, M., Hasterok, D. & Halpin, J. A. Global whole-rock geochemical database compilation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1553–1566 (2019).

United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Transportation and Air Quality. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle (2018).

Jackson, M., Deocampo, D., Marra, F. & Scheetz, B. Mid-pleistocene pozzolanic volcanic ash in ancient roman concretes. Geoarchaeol. Int. J. 25, 36–74 (2010).

Martín, D. A. et al. Ignimbrites related to neogene volcanism in the southeast of the iberian peninsula: An experimental study to establish their pozzolanic character. Materials 16 https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/16/4/1546 (2023).

Dedeloudis, C. et al. Natural Pozzolans (pp. 181–231. Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Global Cement and Concrete Association. Natural pozzolans. https://gccassociation.org/cement-and-concrete-innovation/clinker-substitutes/natural-pozzolans/. Accessed: 20 Mar 2025.

Hamidi, M., Kacimi, L., Cyr, M. & Clastres, P. Evaluation and improvement of pozzolanic activity of andesite for its use in eco-efficient cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 47, 1268–1277 (2013).

Baki, V. A., Nayır, S., Erdoğdu, Ş. & Ustabaş, İ. Determination of the pozzolanic activities of trachyte and rhyolite and comparison of the test methods implemented. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 18, 1053–1066 (2020).

Streckeisen, A. To each plutonic rock its proper name. Earth-Sci. Rev. 12, 1–33 (1976).

Lake, D. J. In-flight vitrification of granitic aggregate: characterization and performance of a scalable supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 409, 133980 (2023).

Kalinkin, A., Kalinkina, E., Politov, A., Makarov, V. & Boldyrev, V. Mechanochemical interaction of ca silicate and aluminosilicate minerals with carbon dioxide. J. Mater. Sci. 39, 5393–5398 (2004).

Song, K., Tan, X., Qin, T., Lu, J. & Liu, T.-Y. Mpnet: Masked and permuted pre-training for language understanding. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 16857–16867 (2020).

all-mpnet-base-v2 https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2 (2020).

Wang, W., Bao, H., Huang, S., Dong, L. & Wei, F. Minilmv2: multi-head self-attention relation distillation for compressing pretrained transformers. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:2012.15828 (2020).

all-minilm-l6-v2 https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 (2020).

Gupta, T., Zaki, M., Krishnan, N. A. & Mausam Matscibert: a materials domain language model for text mining and information extraction. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 102 (2022).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Achiam, J. et al. GPT-4 technical report. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

Jiang, A. Q. et al. Mistral 7b. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:2310.06825 (2023).

O’Malley, T. et al. Kerastuner https://github.com/keras-team/keras-tuner (2019).

White, I. R., Royston, P. & Wood, A. M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 30, 377–399 (2011).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of the Concrete Sustainability Hub at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which is supported by the Concrete Advancement Foundation. This work also received partial funding from the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.R.O., S.M., H.A., and R.R.K. conceived the research idea. S.M. and V.V. designed the literature mining pipeline. S.M. developed the machine learning models, carried out the investigation, and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. I.B.M. and S.M. conducted the supply analysis. E.R.O., H.A., and R.R.K. supervised the project. E.R.O. and S.M. contributed to the discussion and revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Byungju Lee, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jack Evans and Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahjoubi, S., Venugopal, V., Manav, I.B. et al. Data-driven material screening of secondary and natural cementitious precursors. Commun Mater 6, 99 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00820-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00820-4

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in low-carbon ultra-high-performance concrete: materials, mechanisms, and sustainability perspectives

npj Materials Sustainability (2026)

-

Net zero needs AI — five actions to realize its promise

Nature (2025)

-

Municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash in concrete : A systematic review and meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Towards net zero by data-driven discovery of sustainable cement alternatives

Communications Chemistry (2025)