Abstract

Entanglement in fibrous materials strongly affects their mechanical performance, yet quantitative experimental characterisation of entanglement has proved elusive. The widely used hook-drop test is known to be inadequate to evaluate entanglement. Here, we directly demonstrate its shortcomings using a combination of micro-tomography and high-speed photography. These observations motivated us to propose a simpler and more reliable method—a pin insertion test, which directly relates entanglement to its mechanical effects. Application of the basic principles of fracture mechanics to this test allows a direct quantification of the length scale of entanglement. Our ideas not only improve the assessment of entanglements in fibre composites, but also open pathways for investigating and quantifying entanglement in a large class of fibrous materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entangled fibres are ubiquitous in many systems across length scales ranging from biological systems such as worm collectives1, proteins2, entangled intermediate filaments in cells3 and birds’ nests4 to disordered fibrous materials, such as carbon fibres5, entangled polymers6 and intertwined yarns in ropes and fabrics7. This entanglement determines the robustness and behaviour of the fibrous matter. The complexity of visualising and characterising entanglement has, however, meant that most studies are restricted to numerical modelling8,9,10 with the pervasive theme being the topological characterisation through the Gauss linking number1,11,12,13 and/or the mathematical theory of knots14,15,16,17.

While large levels of entanglement in many applications are considered beneficial in terms of endowing the system with mechanical robustness, minimising entanglement is critical in some applications. Carbon fibres manufactured by pyrolysis18, started finding widespread applications in lightweighting and aerospace applications in the 1980s, but their mechanical performance within composites has always lagged significantly behind their theoretical capability. There are multiple reasons for this reduction19 but an important and largely overlooked reason is entanglement of fibres within the non-woven tows (bundles) of fibres (Fig. 1a). This entanglement manifests itself as fibre misorientation within the tow and is a consequence of the manufacturing process of the tow. This entanglement then persists in the resin-impregnated fibre composite- the fibre misalignment and waviness associated with entanglement result in a significant knockdown of the compressive strength of the composite20.

a XCT reconstruction of a ~2 mm length of the pristine carbon fibre tow A. This is extensively used in aerospace applications and comprises ~3000 fibres. The insets show zoom-ins of regions with entangled and parallel fibres. The coordinate system \({X}_{i}\) is shown with the \({X}_{3}-\) direction aligned with the tow axis. The polar angle \(\varphi\) is measured with respect to this axis as indicated. b Distributions of \(|\varphi |\) within the 2 mm tow length shown in (a). c Probability density of \(|\varphi |\) over a 200 mm length of the pristine tow A. The corresponding probability density of \(|\varphi |\) in a 2 mm region below the arrested hook in the hook-drop test, and 2 mm immediately ahead of the crack tip in a \(d=1.4\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) pin insertion tests are also included. Both cases utilised tow A.

In this work, we critically evaluate the widely used hook-drop test used for quantifying entanglement in carbon fibre tows with low levels of entanglement. Through high-speed photography and X-ray computed tomography (XCT), we demonstrate that the hook-drop test significantly alters the fibre arrangement, resulting in an unreliable measure of the pristine tow’s entanglement. To address this, we propose a simpler method, the pin insertion test, which applies the basic principles of fracture mechanics to relate mechanical deformation directly to the degree of fibre entanglement. This test enables the measurement of entanglement in the pristine tow that was earlier missing in the literature. Moreover, unlike previous methods that rely on complex topological measures, the pin insertion test offers a straightforward means of quantifying entanglement using only optical observations, avoiding complex microstructural observations via electron or X-ray microscopy.

Results and discussions

Visualisation of entanglement

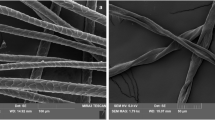

Fibre entanglement in these non-woven (unidirectional) fibre tows is particularly difficult to characterise and hence poorly defined in the literature. Here, via visual observations, we illustrate and define entanglement in the context of a fibre tow. The relatively low entanglement implies a large separation of length scales: while fibre diameters are on the order of a few microns, entanglement or criss-crossing of fibres occurs on the length scale of many millimetres21. To illustrate this entanglement in a practical unidirectional fibre tow, we performed a multi-scale XCT analysis on a tow denoted tow A (to ensure supplier anonymity) comprising ~3000 fibres. The carbon fibres in the tow had diameters of ~5 μm (Supplementary Table 1), and XCT imaging was performed with a spatial resolution of ~1 μm. This high resolution implied that only a 2 mm length of the tow could be imaged in a single XCT scan. We therefore performed 100 such scans along the tow and obtained a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of a 200 mm length of the tow by stitching these 3D images together (Methods). A 3D image of a 2 mm length of the tow from a single XCT scan is shown in Fig. 1a, where fibre misorientation with respect to the overall tow direction is clearly visible (also see magnified views in insets). To quantify this misorientation, we first extracted the local fibre orientations using the gradient structure tensor22 of the 3D XCT image in terms of the polar angle φ and the azimuthal angle where the zenith axis is taken to be the tow axis X3 (Fig. 1a). The distribution of |φ| within the tow is included in Fig. 1b and the associated probability density |φ| of over the 200 mm length of the tow plotted in Fig. 1c (labelled pristine tow). We now interpret these measurements. A highly peaked distribution with the probability p → ∞ at φ = 0 is the limiting case of no entanglement, with a uniform distribution with \(p=1/{90}^{{{{\rm{o}}}}}\,\forall {|}\varphi |\) is the case of a randomly entangled tow. Tow A in Fig. 1 has a highly peaked distribution near φ = 0, indicating the relatively low fibre misorientation in the pristine tow. Nevertheless, there exists a non-zero probability of fibres with a misorientation |φ| ≤ 20°. The existence of these misoriented fibres indicates the possibility of criss-crossing fibres, which is directly related to fibre entanglement, although a direct metric to quantify the length scale of entanglement is difficult to extract even from these detailed observations.

The Hook-drop test

The large separation of length scales between fibre diameter (~5 μm) and length over which entanglement occurs (~3 mm) implies that imaging of entanglement is very laborious, as explained above. The extreme difficulty in characterising entanglement by direct imaging has driven industrial users to develop techniques to indirectly characterise entanglement. Specifically, Toray Industries (Tokyo, Japan), one of the largest manufacturers of carbon fibre tows, has developed a simple apparatus and method, known as the hook-drop test23. We performed hook-drop tests (Methods) on unidirectional carbon fibre tows that were obtained from two leading manufacturers (denoted tow A and tow B) both comprising ~3000 fibres. The test was performed as follows. A tow of length L = 1.5 m was tensioned by a P0 = N weight to keep it taut and straight (Fig. 2a). A hook was then threaded through the tow and weight W = 0.1 N suspended from the hook a distance H0 below the clamp (Fig. 2a). This weighted hook was then allowed to drop through the tow and the drop height ΔH at which it was recorded. The test was repeated 60 times using nominally identical fresh tows with drop ΔH taken to represent a measure of the level of entanglement of the fibres within the tows. A larger ΔH is taken to represent a lower level of entanglement, as, of course, in the absence of entanglement, we would anticipate the hook to drop through the entire length of the tow. The measurements from the 60 separate tests on tows A and B are summarised in Fig. 2b via box and whisker plots. Large scatter from the measurements for both tows A and B is evident, and this casts considerable doubt on the utility of the test as a measure of entanglement within the tow.

a Sketch to show the hook-drop test, including the high-speed camera used to image the fibre. The camera is focused at a distance \(Z=10\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}\) below the initial hook position. b Summary of the measurements of the drop height \(\Delta H\) for tow types A and B. The 60 hook-drop measurements conducted for each tow are summarised via box and whisker plots (the boxes show the quartiles of the data while the whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum values of the drop distances). c Montage of high-speed images of a hook-drop test on tow A. Each image is time-stamped with time \(t=0\) the instant when the hook was released. d XCT reconstruction of the dense or knotted region ~2 mm below the arrested hook in the hook-drop test utilising tow A. The distribution of \(|\varphi |\) is overlaid on the fibres in this reconstruction.

To understand this very high level of scatter, we performed high-speed photography of the hook-drop test on tow A. The high-speed camera (Phantom V12) was focused Z = 10 cm below the stationary hook with the camera recording 1000 frames per second (Fig. 2a). The following key observations can be drawn from the montage of high-speed images shown in Fig. 2c where t = 0 is the instant the hook is released (also see Supplementary Movie 1):

-

(i)

Prior to the hook coming into the view of observation (t ≤ 0.05 s), we observe slackening and oscillatory motion of the fibres, indicating the dynamic nature of the test.

-

(ii)

The slackening of the fibres is suggestive that fibres are breaking as the hook drops. This is further supported by the images when the hook comes into view (t ≥ 0.1 s), which show broken fibres around the hook.

When the hook finally comes to a halt, we observed a dense bunch of fibres concentrated around the hook. XCT images (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2) of this dense or knotted region ~2 mm below the arrested hook provide further insights into the mechanisms involved in the hook-drop test. In the pristine tow, the fibres are nearly straight and parallel to the tow axis (Fig. 1c, d). By contrast, ahead of the arrested hook, many fibres are looped in a braid-like U-formation. Clearly, the hook-drop test has fundamentally changed the geometry and structure of the fibres within the tow. This is better quantified by performing the structure tensor analysis on the 2 mm knotted region. The distribution of |φ| in the knotted region below the arrested hook is included in Fig. 2d, and the corresponding probability density distribution is added to Fig. 1c. The distribution is much wider compared to the pristine tow, i.e. the hook-drop test has fundamentally changed the fibre entanglement from the pristine tow. These observations suggest that the hook-drop test provides little information about entanglement in the pristine tow. This, combined with the large scatter in ΔH (Fig. 2b), implies that the hook-drop test is of questionable value in terms of providing a measure of fibre entanglement in the pristine tow.

Griffith’s characterisation of entanglement

Given that the aim is to measure entanglement in the pristine tow, we need to develop a test that minimally disturbs the fibre arrangement during the process of measurement. The XCT images of the pristine tow (Fig. 1a) provide the first insight into the mechanisms of entanglement. The fibres criss-cross (entangle) over some yet unknown length scale, and this entanglement opposes the separation of the fibres within the tow. But the entanglement also results in fibre deformation (bending) that is opposed by elastic forces that tend to reduce deformation. Such a balance of forces is the basis of the classical Griffith fracture mechanics analysis24, which specifies that incipient crack growth occurs when the loss of potential energy of the system equals the gain in surface energy. Motivated by this Griffith idea, we consider analysing entanglement by a balance of forces wherein entanglement holds the tow together, with elastic deformation opposing these interactions. This idea also critically allows us to devise a simple test to provide an accurate metric of fibre entanglement.

Consider a long tow of width 2b and depth B into the plane paper (Fig. 3a). Insertion of a pin of diameter d to split the tow into two equal halves results in a development of a crack of length 2a as sketched in the inset of Fig. 3a and shown in the optical micrograph in Fig. 3b where a pin of diameter d = 1.4 mm was inserted into tow A. The longitudinal stiffness of the tow is set by the Young’s modulus of the fibres, while the shear stiffness is set by the interactions between fibres that include adhesion (due to sizing of the tow) and entanglement. Consequently, the longitudinal stiffness is much greater than the shear stiffness, and the deformation of the tow over the crack flank is shear dominated. Therefore, as seen in the optical micrograph (Fig. 3b), the crack flanks are straight. XCT reconstructions of the regions around the open crack flank and regions near the crack tip with bridging fibres are included in Fig. 3c, d, respectively. A bridging zone of length λ ~ 2.7 mm is visible in Fig. 3d where the tow is attempting to split apart but held together by the criss-crossing fibres (entangled fibres); see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the method to quantitatively infer λ from the tomographic measurements and Supplementary Fig. 4 for the fibre structure around the crack tip. The entangled fibres form the bridging zone, which imparts toughness to the tow. Consequently, the length λ of the bridging zone directly reflects the degree of fibre entanglement. Thus, λ → 0 implies no entanglement and no toughness, so that insertion of a pin will split the entire tow apart. We can now use notions of fracture mechanics to relate the crack length 2a and the pin diameter d to λ to get a simple way to extract the entanglement length without the need for difficult tomographic observations.

a Sketch of the pin insertion test in a tow of width \(2b\). Insertion of a pin of diameter \(d\) results in a crack of length \(2a\) forming in the tow. The inset shows a sketch of a magnified view of the crack along with the shear deformation mode of the crack. b Optical image of the tow A with an inserted pin of diameter \(d=1.4\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\). c XCT images of a region within the crack with negligible bridging and d near the crack tip region to show the bridging zone. In (d), we include images for the bridging zone created by two different pin diameters, \(d\). In both cases, \(\lambda \sim 2.7\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\). d The distribution of \(|\varphi |\) is overlaid on the XCT reconstruction for the region ~2 mm ahead of the crack tip. All results here are for tow A.

The tow comprises ~3000 fibres, and so when split equally, each half contains ~1500 fibres. These large number of fibres implies that each half of the tow can be well-approximated as a continuum solid with the ratio of the half-width b of the tow to the microstructural length scale (tow diameter in this case) ~1500: typically, continuum mechanics is known to be an excellent approximation for ratios >2025. Recall that deformation of the tow over the crack flanks is primarily in shear. However, the high interactions between the fibres over the bridging length λ imply that deformation is restricted to occur over a length 2(a−λ) rather than the full crack length 2a. With μ denoting the effective shear modulus of the tow, the elastic stored energy within the tow is given by

Note that in this pin insertion test (unlike the Hook-drop test), there is no movement of the inserted pin within the tow. Then, assuming that the entanglement length λ is independent of a, the energy release rate \({G}_{{{{\rm{I}}}}}\) for mode-I propagation of the crack then follows as

At incipient crack propagation, the energy release rate equals the toughness \({G}_{c}\) and therefore, setting \({G}_{{{{\rm{I}}}}}={G}_{c}\) in (2), we obtain a relation between the half-crack length \(a\) and pin diameter as

This relation can give a direct and simple method to extract the entanglement wavelength \(\lambda\) without complex imaging. We emphasise that (3) is valid for large \(a\) where the bridging zone of length \(\lambda\) attains a steady state that is independent of \(a\). This steady state \(\lambda\) is a measure of entanglement in the pristine tow as it is a material parameter that is independent of the loading that generates the crack. The validity of this continuum analysis in capturing the response to a pin insertion will now be confirmed via measurements and observations.

To confirm this hypothesis, pin insertion tests were conducted by employing tows of length \(L=1\,{{{\rm{m}}}}\) under a fixed tension \({P}_{0}=1\,{{{\rm{N}}}}\) and conical tip steel pins (spray coated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) to reduce friction) of diameter \(0.6\,{{{\rm{mm}}}} < d < 1.5\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) inserted at-least 100 mm away from either end (Fig. 3a). The conical tips and PTFE coating implied that the pin insertion was accomplished with minimal disturbance of the pristine tow. Insertion of the pin generated the crack as seen in Fig. 3b: here we chose to insert a pin so that the tow split approximately into equal halves to be consistent with the model developed above. Additional measurements (not shown here for the sake of brevity) confirmed that these results are insensitive to \({P}_{0}\) over the range 1–10 N. The measured half-crack lengths \(a\) as a function of \(d\) are included in Fig. 4: for each pin diameter, 60 repeat measurements were conducted by inserting in different locations for both tow types A and B. These measurements were obtained from direct optical observations of the type shown in Fig. 3b where a clear crack tip is visible that makes determination of the crack length clear. The error bars in Fig. 4 indicate the variation over the 60 measurements, with the marker showing the mean over the measurements. Minimal scatter (compared to the hook-drop test) firstly allows for statistically significant inferences and suggests that this test is insensitive to the details of the microstructures and captures the overall entanglement at the tow level, which is of primary interest here. Further, the data confirms that in line with the continuum prediction (3), the variation of \(a\) with \(d\) is linear for both tows and with a finite positive intercept on the y-axis, i.e. for the range of \(d\) values investigated here, the assumption that \(\lambda\) is independent of \(a\) is valid. The best fits to the data are indicated in Fig. 4. Given the detailed imaging that we have conducted on tow A, we now examine the pin insertion data for tow A more closely. The pin insertion data for tow A is well-described by the equation \(a=5.1d+2.74\) where \(a\) and \(d\) are in millimetre (Fig. 4). It then follows from (3) that \(0.5 \sqrt{(\mu t) / \left.{G}_{c}\right)} = 5.1\) and \(\lambda \sim 2.8\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\), i.e. \(\lambda\) can directly be inferred from the intercept on the y-axis from the data (Fig. 4) of the pin insertion test without need for complex tomographic measurements. Moreover, \(\lambda\) inferred in this manner is in remarkable agreement with the XCT data of Fig. 3d where we inferred \(\lambda \approx 2.7\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) for two pin diameters: the fact that \(\lambda\) from direct observations is independent of the pin diameter provides further evidence of our view that the bridging zone length is a material metric that characterises entanglement. We thus suggest that two unique metrics that characterise entanglement emerge from this simple high-fidelity test that requires no XCT or Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) observations: (i) the length scale \(\lambda\) over which entanglement occurs and (ii) the parameter \(\sqrt{(\mu t)/\left. {G}_{c}\right)}\) that characterises the strength of the fibre interactions which might be associated with both inter-fibre adhesion and knots. We note that independent measurement of \(\mu\) (which can be difficult for a tow) is not required for the analysis of the pin insertion test. Using the same analysis, we infer that \(\lambda =1.74\,{{{\rm{mm}}}}\) for tow B, i.e. entanglement occurs over a shorter wavelength and therefore tow A is more entangled.

Measurements of the half-crack length \(a\) versus pin diameter \(d\) for tows A and B. The error bars show the range (and mean indicated by the markers) of the 70 measurements conducted for each pin diameter. For both tows we include a best linear fit to the data of the form \(a=\alpha d+\lambda\) where \(a\), \(d\) and \(\lambda\) are in millimetre and \(\alpha \equiv 0.5\sqrt{\mu t/{G}_{c}}\,\) is dimensionless.

We have set out to develop a simple test to measure entanglement in the pristine tow as opposed to the hook-drop test that fundamentally changes the tow topology. An XCT reconstruction of the state of tow A over a length of 2 mm immediately ahead of the crack tip in Fig. 3b is included in Fig. 3e (also see Supplementary Fig. 4). The fibres in Fig. 3e are shaded to show the local orientation \(|\varphi |\) inferred from the structure tensor analysis (Methods). The XCT images in Fig. 3d show the fibre criss-crossing or entanglements that provide the force to prevent fibre separation (i.e. toughness). However, unlike the hook-drop test, the state of the tow ahead of the crack strongly resembles the pristine tow. To quantify this, we include in Fig. 1c the probability density of \(|\varphi |\) from the XCT image in Fig. 3e. The close resemblance of this distribution with that of the pristine tow supports our assertion that the pin insertion test only minimally disturbs the fibre arrangement in the pristine tow, i.e. the pin insertion test measures a property of the pristine tow as opposed to the hook-drop test.

Conclusions

Rigorous investigations of fibrous entanglement have largely been restricted to the topological concepts related to the Gauss linking number. This metric was particularly difficult to quantify in non-periodic and minimally entangled fibrous systems, such as the carbon fibre tows are investigated here. In this context of fibrous systems, we have circumvented this topological problem by directly characterising entanglement via a mechanical metric, viz., a crack bridging length. In fact, the pin insertion test that we have developed characterises entanglement in the pristine tow without the need for complex tomographic or SEM observations, but only relatively simple optical observations of the crack length created by pin insertion. We anticipate that this test is suitable for systems with low levels of entanglement without significant hierarchy, where an insertion of a pin results in the formation of a crack. However, in highly entangled fibrous systems (e.g. woven materials), it is likely that no such crack will form, and the pin insertion test is unsuitable in such scenarios.

Entanglement or knotting is thought to primarily affect mechanical properties20 and the proposed test metric directly relates entanglement and its mechanical consequences. In fact, while multi-scale microstructure level modelling of composites and associated virtual testing are now ubiquitous in many applications26, fibre entanglement has been largely ignored due to a lack of data. This has reduced the fidelity of such models. The pin insertion test introduced here could help improve the predictive capability of these multi-scale models and thereby the design of composite structures.

Methods

X-ray computed tomography

X-ray tomography scans were performed on a Zeiss Versa 520 system. The fibre tows were fixed between soft polystyrene foam to prevent movement during the scan. Using an optical magnification of 4×, around 2000 projections were captured, each with a 7.5 s exposure time to achieve an effective scan resolution of \(\sim 1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). Each scan visualised ~2 mm of the tow length, so a stacked scan protocol was employed, with the scans vertically stitched together to cover a total tow length of about 200 mm. The reconstructed scans were exported as image stacks into VGStudio Max 2022.4 for 3D analysis. To delineate individual fibres from the background, a region-growing approach was employed, leveraging grey value tolerances to accurately delineate/segment fibres from air and polystyrene. The fibre diameters were measured to confirm the accuracy of the segmentation, and the Fibre Analysis module within VGStudio Max 2022.4 was then used to extract fibre orientations \(\varphi\) using the gradient structure tensor method21. All images provided in the text were directly obtained from the scans without any post-processing using external image software.

Multi-scale X-ray computed tomography

Tomography was performed at different resolutions, referred to here as multi-scale XCT for the data in Fig. 1. About 100 scans were conducted on a tow of ~1 m in length at various locations, covering a total scan length of 200 mm. This is the same tow that was subsequently used for the hook-drop test. The tow was held taut using a thin Perspex rod, and a small piece of polystyrene foam was placed around the scan area to prevent movement during scanning. Additionally, a stacked scan protocol was employed, whereby scans were continuously taken over a span of ~200 mm and vertically stitched together. The orientation distribution obtained from both measurement approaches, continuous over 200 mm and at 100 discrete locations (covering a total length of 200 mm) along the 1 m tow showed negligible differences. The various parameters used for the acquisition are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

For the high-resolution imaging (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 2–4), the specimens were held in position, and a full rotation of the specimen was used. The specimen was also moved much closer for a larger geometrical magnification, and the parameters used for the scans are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Measurement of fibre orientation

The voxel-based gradient structure tensor method22 is widely employed to determine local fibre orientations. This technique involves calculating the structure tensor from local image gradients, allowing for the estimation of fibre directions within a tow. The Fibre Composite Material Analysis Module within VGStudio Max 2022.4 calculates the local gradients in voxel intensity values, which form a gradient structure tensor for each voxel. Consider the tow in Fig. 1 where the X3-axis is aligned with the axial direction of the unidirectional fibre tow. The gradient structure tensor at a spatial location \({x}_{i}\) is then defined as

where \({g}_{1}\), \({g}_{2}\) and \({g}_{3}\) are the local grey value intensity gradients along the \({X}_{1},{X}_{2}\) and \({X}_{3}-\) axes, respectively, while \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle\) denotes averaging over a small local volume around \({X}_{i}\). In our analysis, this local averaging was performed over a side of four voxels. The principal fibre direction at each voxel is obtained by solving the eigenvalue problem \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}\,{v}_{i}^{(I)}\,={\lambda }^{(I)}\,{v}_{i}^{(I)}\). The eigenvector \({v}_{i}^{(I)}\) associated with the smallest eigenvalue \({\lambda }^{(I)}\,\) indicates the dominant fibre direction. After extracting local orientation vectors, the polar angle \(\varphi\) is extracted with respect to the coordinate system \(({X}_{1},{X}_{2},{X}_{3})\) shown in Fig. 1a.

Hook-drop test protocol

For the hook-drop test, a 1.5 m length of carbon fibre tow was cut from a spool using scissors. A 1 N mass was securely tied to one end of the tow, while the other end was attached to an extended bar, allowing the tow to hang vertically under tension (Fig. 1a). A light hook, weighted with a 0.1 N mass, was then inserted into the centre of the tow at a marked height. Upon release, the hook dropped freely, falling a short distance before being arrested due to the formation of knots within the tow. Once the system had settled, the vertical distance from the initial drop point to the top of the hook at its resting position was measured. This procedure was repeated 60 times to collect a sufficient dataset. For high-speed visual analysis, a Phantom high-speed camera was mounted on a tripod and connected to a laptop, positioned 25 cm from the expected stopping point based on the previous trials. A white background was placed behind the tow for contrast, and the camera was focused on the tow. As the hook was released, the recording was triggered at 2000 frames per second, capturing both the fall and the stopping motion, including moments prior to the trigger via the camera’s pre-buffer function. Several recordings were made to capture instances of the hook stopping within, above, and below the camera frame.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Patil, V. P. et al. Ultrafast reversible self-assembly of living tangled matter. Science 380, 392–398 (2023).

Dabrowski-Tumanski, P. et al. KnotProt 2.0: a database of proteins with knots and other entangled structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D367–D375 (2019).

Pensalfini, M., Golde, T., Trepat, X. & Arroyo, M. Nonaffine mechanics of entangled networks inspired by intermediate filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 058101 (2023).

Bhosale, Y. et al. Micromechanical origin of plasticity and hysteresis in nestlike packings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 198003 (2022).

Chatti, F., Poquillon, D., Bouvet, C. & Michon, G. Numerical modelling of entangled carbon fibre material under compression. Comput. Mater. Sci. 151, 14–24 (2018).

Kim, J., Zhang, G., Shi, M. & Suo, Z. Fracture, fatigue, and friction of polymers in which entanglements greatly outnumber cross-links. Science 374, 212–216 (2021).

Warren, P. B., Ball, R. C. & Goldstein, R. E. Why clothes don’t fall apart: tension transmission in staple yarns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 158001 (2018).

Rodney, D., Fivel, M. & Dendievel, R. Discrete modeling of the mechanics of entangled materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 108004 (2005).

Jung, Y., Plumb-Reyes, T., Lin, H. Y. G. & Mahadevan, L. Entanglement transition in random rod packings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122, e2401868122 (2025).

Weiner, N., Bhosale, Y., Gazzola, M., & King, H. Mechanics of randomly packed filaments—the “bird nest” as meta-material. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 050902 (2020).

Ricca, R. L. & Nipoti, B. Gauss Linking number revisited. J. Knot Theory Ramif. 20, 1325–1343 (2011).

Deblais, A. et al. Worm blobs as entangled living polymers: from topological active matter to flexible soft robot collectives. Soft Matter 19, 7057–7069 (2023).

Ricca, R. L., & Nipoti, B. Derivation and Interpretation of the Gauss Linking Number. In Introductory Lectures on Knot Theory: Selected Lectures Presented at the Advanced School and Conference on Knot Theory and Its Applications to Physics and Biology 482–501 (World Scientific, 2012).

Plumb-Reyes, T. B., Charles, N. & Mahadevan, L. Combing a double helix. Soft Matter 18, 2767–2775 (2022).

Grishanov, S., Meshkov, V. & Omelchenko, A. A topological study of textile structures. Part II: topological invariants in application to textile structures. Text. Res. J. 79, 822–836 (2009).

Grishanov, S., Tausif, M. & Russell, S. J. Characterisation of fibre entanglement in nonwoven fabrics based on knot theory. Compos. Sci. Technol. 72, 1331–1337 (2012).

Patil, V. P., Sandt, J. D., Kolle, M. & Dunkel, J. Topological mechanics of knots and tangles. Science 367, 71–75 (2020).

Roger, Bacon. Filamentary graphite and method for producing the same. U.S. Patent No. 2,957,756. 25 Oct. 1960.

Fu, Y. & Yao, X. A review on manufacturing defects and their detection of fiber reinforced resin matrix composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 8, 100276 (2022).

Wisnom, M. R. The effect of fibre misalignment on the compressive strength of unidirectional carbon fibre/epoxy. Composites 21, 403–407 (1990).

Fast, T., Scott, A. E., Bale, H. A. & Cox, B. N. Topological and Euclidean metrics reveal spatially nonuniform structure in the entanglement of stochastic fiber bundles. J. Mater. Sci. 50, 2370–2398 (2015).

Miletić, M. et al. Gradient-based fibre detection method on 3D micro-CT tomographic image for defining fibre orientation bias in ultra-high-performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 129, 105962 (2020).

Toray Industries, Inc. Carbon fiber prepeg and method of production thereof. US patent 4,719,576 (1988).

Griffith, A. A. VI. The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 221, 163–198 (1921).

Pelissou, C., Baccou, J., Monerie, Y. & Perales, F. Determination of the size of the representative volume element for random quasi-brittle composites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46, 2842–2855 (2009).

LLorca, J. et al. Multiscale modeling of composite materials: a roadmap towards virtual testing. Adv. Mater. 23, 5130–5147 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the UKRI Frontier Research grant ‘Graph-based Learning and design of Advanced Mechanical Metamaterials’ with award number EP/X02394X/1 and Hexcel Composites. A.J.D.S. acknowledges funding from the Ashby Postdoctoral Fellowship, Department of Engineering, Cambridge University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.S.D. conceived and designed the research. B.W. performed the experiments and analysis. A.J.D.S. designed and performed the X-ray measurements. B.R. and S.D. provided theoretical inputs into the study and guided the data analysis. V.S.D. and A.J.D.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in revising the manuscript, the discussion, and the interpretation of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wardell, B., Russell, B., Das, S. et al. Fracture mechanics characterises fibre entanglement. Commun Mater 6, 132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00824-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00824-0