Abstract

Al-ion batteries (AIBs) have emerged as a promising energy storage technology due to their high theoretical capacity, cost-effectiveness, and superior safety. However, the lack of stable and efficient cathode materials capable of reversible Al-complex ion (e.g., [AlCl4]−) insertion/extraction remains a critical challenge. In this work, we developed TiNbCTx MXene as a high-performance cathode material for AIBs, achieving remarkable capacity and cycling stability. Unlike symmetric-structured Ti2CTx, the TiNbCTx cathode leverages synergistic Ti–Nb bimetallic effects to enhance the electronic conductivity and electrochemical activity. Here we show, TiNbCTx delivers a high reversible capacity of 194 mAh·g−1 at 0.2 A·g−1 with 800-cycle stability. Through combined experimental characterization and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we elucidate the kinetic mechanisms of energy storage, offering fundamental insights for the rational design of advanced cathode materials in AIBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing large-scale energy storage systems is strongly required to ensure effective power dispatch and load management of renewable energy sources such as wind, hydro, and solar power due to their intermittency and volatility1,2,3. Al-ion batteries (AIBs), as an emerging large-scale energy storage technology, have recently gained significant attention due to their high energy density, low cost, and exceptional safety profile4,5,6,7. The development of durable, high-capacity cathode materials for efficient and stable intercalation of Al-complex ions remains a priority. Transition metal oxides/sulfides, such as V2O5, Mo6S8, and CuS, suffer from rapid capacity decay and structural degradation under extended cycling8,9,10. Structural modifications have shown limited success in improving cycle life and capacity retention of above mentioned cathode materials. Carbon-based materials with layered structures have shown promise for accommodating Al-complex ions while improving cycle stability, but suffered from low specific capacity11. Studies on two dimensional V2CTx and Nb2CTx MXenes in AIBs indicate that MXenes can maintain stable capacities over hundreds of cycles due to their unique layered structure and tunable interlayer spacing, providing new avenues for cathode optimization in AIBs12,13. Continued exploration of MXene materials, along with structural modifications, could pave the way to more reliable and efficient AIBs suitable for large-scale energy storage solutions. MAX phases are layered ternary carbides/nitrides that serve as precursors for MXenes, which are produced by selectively etching the “A” layer (typically Al or Si) from the MAX phase to yield two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides. Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) have a formula of Mn+1XnTx (n = 1–4)14,15, where M is an early transition metal, X is carbon and/or nitrogen, and Tx represents the surface termination groups, such as –OH, –O, and –F. MXenes offer an unusual combination of metallic conductivity and hydrophilicity, exhibiting attractive electrochemical properties16,17,18,19. In addition, their ability of intercalating ions and small organic molecules led to promising performance in energy storage applications20,21,22,23. However, almost all the studies have been on as-synthesized mono-transition metal MXenes, such as Ti3C2Tx, V2CTx, and Nb2CTx24,25,26.

In this study, we fabricated dual-transition metal TiNbCTx MXene as a cathode material in AIBs by selectively removing Al atomic layers from the TiNbAlC MAX phase through HF acid etching and followed delamination (see “Methods” section for details). The synthesized TiNbCTx MXene incorporated with surface terminations (–OH, –O, and –F) exhibited effective ion storage and high specific capacity. The Nb incorporation in TiNbCTx architecture facilitated the [AlCl4]−/Al3+ adsorption compared with the mono-elemental Ti2CTx MXene. The rechargeable AIB featured with TiNbCTx MXene as the cathode, Al foil as the anode, and [EMIm]Cl/AlCl3 as the electrolyte, demonstrated a high specific capacity of 194 mAh g−1 at a current density of 200 mA g−1 after 800 cycles. The energy storage mechanisms of the TiNbCTx MXene cathode were investigated by ex-situ characterizations alongside complementary density functional theory calculations.

Results and discussion

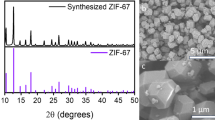

Figure 1a schematically illustrates the synthesizing process of TiNbCTx MXene from the TiNbAlC precursor through hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching. Bulk TiNbCTx MXene with an accordion-like structure (Fig. 1b) was obtained after selectively removal of Al layers in the TiNbAlC MAX phase (Figs. S1, S2a–c). Figure 1c shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of TiNbCTx MXene flakes after Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAOH) delamination. A high resolution TEM image of as synthesized TiNbCTx MXene (Fig. 1d) indicates the hexagonal symmetry of the Ti and Nb atoms. Figure S2d–f reveal the morphology of monolayer TiNbCTx MXene, indicating a high degree of exfoliation. Figure S3 shows the EDX mapping of TiNbCTx MXene flake, presenting a uniform elemental distribution of Ti, Nb, and C. Ti2CTx MXene was fabricated to be a control group through a reported method27. Figure 1e–g presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the synthesized TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx MXenes and their precursors TiNbAlC and Ti2AlC MAX phases. After the selective etching and delamination, the (002) characteristic diffraction peak of TiNbAlC shifted from 2θ = 12.66° to 2θ = 6.82°, while that of Ti2AlC shifted from 2θ = 13.02° to 2θ = 7.47°, indicating an enlarged c-axis lattice constant and interlayer spacing due to the removal of Al atomic layers from the MAX precursors28,29,30. The enlarged interlayer spacing of MXenes facilitates the transport of Al-complex ions during the charge/discharge process in AIBs, thereby improving their electrochemical performance. Figure S4a presents the atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of few-layer TiNbCTx MXene flakes, while Fig. S4b shows the height profile along the trace line in Fig. S4a. The profile indicates that the prepared TiNbCTx MXene flakes have a thickness of ~4.8 nm, which corresponds to three molecular layers (with a monolayer thickness of ~1.6 nm). Figure 1i shows the wide-range X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of as-synthesized TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx MXene, indicating the existence of −F and −O terminations. Figure S5 displays the high-resolution XPS spectra of TiNbCTx, where the C1s high-resolution XPS spectrum shows two strong peaks at 284.38 eV and 284.88 eV, corresponding to C-Ti/C-Nb and C-C bonds in TiNbCTx MXene, respectively28. Additionally, three weak peaks at 285.98 eV, 286.98 eV, and 290.28 eV correspond to C-O, O = C-O, and C-F bonds, indicating the presence of surface functional groups such as −O, −F, and −OH on the TiNbCTx MXene successfully prepared by HF acid etching30.

a Schematically illustration of the synthesizing process of TiNbCTx MXene from the TiNbAlC precursor through hydrofluoric acid (HF) etching. b SEM image of bulk TiNbCTx MXene, and c) delaminated TiNbCTx MXene flake. d High-resolution TEM image of TiNbCTx MXene. e XRD patterns of Ti2AlC MAX, TiNbAlC MAX, Ti2CTx MXene, and TiNbCTx MXene. f Localized zoom around (002) characteristic peak of the XRD pattern of delaminated Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene. g Wide-range X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of as-synthesized TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx MXene.

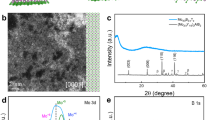

Using a combination of X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), we systematically investigated the structural evolution and electrochemical behavior of the TiNbCTx cathode material during charge/discharge cycles. Figure 3a presents the ex-situ XRD spectra of the TiNbCTx cathode before and after cycling. In the initial state, the (002) characteristic peak of d-TiNbCTx appears at 7.52°, while after full charging, this peak shifts to a lower angle at 5.82°, directly confirming the successful insertion of the [AlCl4]− and the resulting increase in interlayer spacing. After fully discharging, the (002) peak shifts back towards a higher angle, approaching its original position (around 7.4°), indicating that most of the Al-complex ions have been extracted from the interlayer, although some remain chemically adsorbed on the MXene surface. This finding is consistent with the material’s reversible charge/discharge behavior. Figure 3b shows the incremental changes in the Raman spectra of d-TiNbCTx during the charge/discharge process, further revealing changes in the electronic structure of the d-TiNbCTx cathode. During charging, the D peak (1355 cm−1) shifts to a lower frequency, while the G peak (1580 cm−1) shifts to a higher frequency. Both weakened peaks lead to a decrease in the ID/IG ratio from 0.837 to 0.821. This change is attributed to the electronic band structure adjustment caused by the insertion of the [AlCl4]−, which occupies empty states and reduces the generation of defect-induced electron-hole pairs31. During discharge, both the D and G peaks return to their original positions, and their intensities increase, further confirming the highly reversible nature of the charge/discharge process. Figure 3c presents the XPS spectra of the Ti 2p core levels before and after cycling. After fully charging, the binding energy of the Ti-C-Tx component shifts from 460.38 to 460.88 eV, with a notable increase in peak intensity30. This indicates a strong chemical adsorption interaction between the TiNbCTx MXene surface and the inserted Al-complex ions. The chemical adsorption of these Al-complex ions leads to electron release, further increasing the effective positive charge in the MXene cathode. Figure 2d, e show the XPS spectra of Al 2p and Cl 2p core levels before and after charge/discharge. In the initial state, no signals for Al 2p or Cl 2p were detected in the TiNbCTx cathode. However, after charging to 2.3 V, the XPS peaks for Al 2p and Cl 2p are significantly enhanced due to the insertion of [AlCl4]− anions. After discharging to 0.01 V, although the Al 2p and Cl 2p signals are still present, they are much weaker, suggesting that the extraction of the [AlCl4]− is not complete. This is consistent with the chemical adsorption interaction between the MXene and the inserted ions, as well as the XRD results. These findings, supported by XRD and Raman spectroscopy data, collectively reveal that the specific capacity of the TiNbCTx MXene electrode primarily arises from the insertion/extraction of interlayer Al-complex ions and the chemical adsorption effects associated with this process.

a XRD pattern of TiNbCTx MXene before the test and after fully (dis)-charging. b Raman spectra of TiNbCTx MXene measured during the (dis)-charge process. c Ti 2p core level XPS spectra of TiNbCTx MXene before the test and after fully (dis)-charging. d Al 2p, and (e) Cl 2p core level XPS spectra of TiNbCTx MXene before the test and after fully (dis)-charging.

To investigate the energy storage properties of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx cathode materials in AIBs, we recorded cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves at different scan rates (Fig. 3a, b). Figure 3a shows the CV curves of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx cathodes in the voltage range of 0.1 V to 2.3 V at a scan rate of 1 mV·s−1. Compared to the Ti2CTx cathode, the TiNbCTx electrode exhibits more prominent oxidation and reduction peaks, as well as a larger integrated curve area. This indicates more active ion insertion and extraction during the charge/discharge process, reflecting more significant redox reactions. This high electrochemical activity grants the TiNbCTx electrode higher efficiency in charge storage and release, resulting in superior electrochemical performance. Further, Fig. 3b shows the CV curves of the TiNbCTx electrode during the second to fifth cycles at a scan rate of 0.5 mV·s−1. In the second cycle, two distinct oxidation peaks are observed at 1.27 V and 2.21 V, along with reduction peaks at 0.967 V and 1.949 V. These characteristic peaks directly confirm the occurrence of ion insertion and extraction (i.e., redox reactions). Notably, the subsequent scans exhibit excellent reproducibility, confirming both the reversibility of the redox reactions in the TiNbCTx electrode and its high stability during electrochemical cycling. Next, constant current charge/discharge tests were conducted on both Ti2CTx and TiNbCTx electrodes. Figure 3c displays the voltage-specific capacity curves of both electrodes at a current density of 0.1 A g−1. The results show that, during the first and fifth cycles, TiNbCTx exhibited specific capacities of 678 mAh g−1 and 571 mAh g−1, respectively, which are significantly higher than the 347 mAh g−1 and 176 mAh g−1 observed for Ti2CTx. The observed reduction in initial cycle capacity from 678 mAh g−¹ to 571 mAh g−¹ is primarily attributed to electrolyte decomposition and interfacial side reactions. Even after 100 and 200 cycles, TiNbCTx maintained a specific capacity of over 200 mAh g−1, far surpassing 118 mAh g−1 of Ti2CTx. Figure 3d presents the cycling stability of the TiNbCTx electrode at a higher current density of 0.2 A g−1. Due to electrode activation, TiNbCTx achieved a specific capacity of 194 mAh g−1 after 800 cycles, demonstrating excellent cycling stability. Figure 3e shows the capacity retention rates of Ti2CTx and TiNbCTx after cycling at different current densities. The TiNbCTx electrode demonstrated a capacity retention rate of 34.76%, which is superior to 28.97% of Ti2CTx. Rate performance tests further confirm the advantages of TiNbCTx as a cathode material. Figure 3g shows the rate performance of TiNbCTx at different current densities. At current densities of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 0.1 A g−1, the TiNbCTx electrode provided reversible capacities of 189, 127, 83, 61, and 269 mAh g−1, respectively, which are significantly higher than the 62, 40, 26, 20, and 43 mAh g−1 provided by the Ti2CTx electrode. The limitations in high-rate performance are predominantly governed by the restricted diffusion kinetics of aluminum ions. Notably, after 20 cycles, the TiNbCTx electrode showed an increase in specific capacity at 0.1 A g−1 compared to the first five cycles, consistent with the earlier described electrode activation phenomenon. Figure 3h demonstrates the cycling performance of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx at a current density of 0.1 A g−1. The TiNbCTx electrode consistently exhibited significantly higher specific capacity throughout the entire test cycle compared to Ti2CTx. These excellent electrochemical performances are attributed to the unique Janus structure of TiNbCTx, which greatly facilitates ion and electron transport within the electrode, thereby imparting superior rate capability. The Nyquist plot in Fig. 3f reveals the redox reaction kinetics and charge transfer resistance of the TiNbCTx cathode. The TiNbCTx cathode shows much lower charge transfer resistance (Rct = 29 Ω) in the mid-to-high-frequency region, indicating outstanding performance in redox reaction kinetics and electronic conductivity. In the low-frequency region, the diffusion response curves of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx are shown in Figure S6, illustrating the relationship between impedance and phase angle (θ). The Warburg factor (θ2) of TiNbCTx is much smaller than that of Ti2CTx (θ1), which corresponds to a higher diffusion coefficient of [AlCl4]− in the TiNbCTx electrode. This explains its superior rate performance, further supporting the earlier conclusions.

a CV curves of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene at a scan rate of 1.0 mV s−1. b The 2nd to 5th CV curves of TiNbCTx MXene at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1. c (Dis)-charge profiles of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene at a current density of 0.1 A g−1. d Selected (dis)-charge profiles of TiNbCTx MXene at a current density of 0.2 A g−1. e Capacity retention of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene at different current densities. f EIS spectra of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene. g Rate performance of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene. h Cyclic performance of Ti2CTx MXene and TiNbCTx MXene at a current density of 0.1 A g−1. The active mass loading of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx electrodes was standardized at 1.2 mg cm−2 with an error margin of ±0.1 mg cm−2.

To gain a deeper understanding of the reaction kinetics and mechanisms of TiNbCTx and Ti2CTx, we recorded CV curves at different scan rates (Fig. 4a, d). The results show that, at the same scan rate, TiNbCTx exhibits sharper and more distinct oxidation and reduction peaks, indicating more significant ion insertion and extraction processes. To better quantify the contribution of capacitive behavior, we calculated the b values for the TiNbCTx MXene electrode at various scan rates. These values were determined based on the relationship between the peak current and scan rate from the CV curves. For the oxidation and reduction peaks, the b values were 0.83 and 0.66, respectively (Fig. S7). These values are close to 1, suggesting that pseudocapacitance is the dominant contributor to the overall capacitance of the TiNbCTx electrode. Figure 4b, e illustrate how the contribution of capacitive behavior changes as the scan rate increases. Compared to Ti2CTx, TiNbCTx shows a higher contribution from non-capacitive behavior, indicating more pronounced battery-type characteristics. Typically, intercalation-based materials provide higher specific capacity and energy density because they utilize the entire volume of the material for energy storage. Moreover, as the scan rate increases from 0.3 to 10 mV s−1, the pseudocapacitive contribution of TiNbCTx gradually increases. At a scan rate of 10 mV s−1, the capacitive contribution reaches 84%, demonstrating clear pseudocapacitive behavior and contributing to superior cycling stability. Figure S8 provides a visual representation of the ratio of capacitive behavior during the rapid diffusion of Al ions at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1, showing the typical voltage distribution of capacitive current relative to the total current. At this rate, the intercalation mechanism contributes 46%, while the adsorption mechanism accounts for 54%. Figure 4c, f, respectively, show the self-discharge curves of the Ti2CTx and TiNbCTx MXene cathode at a charge rate of 200 mA g−1, indicative of a more stable discharging plateau of the TiNbCTx compared to the Ti2CTx cathode.

a CV curves of Ti2CTx MXene at different scan rates from 0.3 to 5 mV s−1. b Contribution of capacitive behavior changes as the scan rate increases. c Self-discharge curve of the Ti2CTx MXene cathode at a charge rate of 200 mA g−1. d CV curves of TiNbCTx MXene at different scan rates from 0.3 to 10 mV s−1. e Contribution of capacitive behavior changes as the scan rate increases. f Self-discharge curve of the TiNbCTx MXene cathode at a charge rate of 200 mA g−1.

First-principles calculations are used to comprehend the impact of Nb incorporation on the electrochemical performance of Ti2CO2. The optimized structure of the Ti2CO2 monolayer is shown in Fig. 5a. As our experiments suggest that Nb forms a solid solution with Ti2CO2, so we study a TiNbCO2 monolayer in which the Nb and Ti are distributed evenly, as shown in Fig. 5b. The obtained band structures in Fig. 1a, b show that the Nb incorporation results in a transition from semiconducting to metallic behavior, which benefits fast electron transport during charging and discharging. As our experiments suggest that [AlCl4]− and Al3+ ions participate in the charging and discharging processes, we study the interaction of AlCl4 and Al with the Ti2CO2 and TiNbCO2 monolayers. The adsorption energy is calculated as ETi2CO2/TiNbCO2+AlCl4/Al – ETi2CO2/TiNbCO2 – EAlCl4/Al, where the three terms are the total energies of the Ti2CO2/TiNbCO2 monolayer with one adsorbed AlCl4/Al, the pristine Ti2CO2/TiNbCO2 monolayer, and AlCl4/Al, respectively. A more negative adsorption energy indicates stronger adsorption. We find for both the Ti2CO2 and TiNbCO2 monolayers that AlCl4 (Fig. 5c, d) and Al (Fig. 5e, f) absorb preferentially on top of a C atom, with adsorption energies of −1.35 and −1.54 eV in the case of AlCl4 and −3.98 and −4.44 eV in the case of Al, respectively. Therefore, the Nb incorporation enhances the adsorption of AlCl4 and Al.

a Top and side views of the Ti2CO2 monolayer and the corresponding band structure. b Top and side views of the TiNbCO2 monolayer and the corresponding band structure. Top and side views of AlCl4 adsorbed on the (c) Ti2CO2 and (d) TiNbCO2 monolayers. Top and side views of Al adsorbed on the (e) Ti2CO2 and (f) TiNbCO2 monolayers. Blue spheres = Ti, green spheres = Nb, gray spheres = C, red spheres = O, pink spheres = Al, and yellow spheres = Cl.

Conclusions

In this study, we synthesized TiNbCTx MXene, a dual-transition-metal material, as a high-performance cathode for aluminum-ion batteries (AIBs). The asymmetric Ti–Nb configuration optimizes electronic properties, reduces ion migration barriers, and enhances conductivity and electrochemical activity—yielding more active sites than single-metal Ti2CTx MXene. TiNbCTx exhibits exceptional electrochemical performance, delivering an initial discharge capacity of 678 mAh g−1 at 0.1 A g−1 and retaining a stable capacity of ~200 mAh g−1 after 800 cycles at 0.2 A g−1. Cyclic voltammetry confirms highly reversible redox reactions and substantial [AlCl4]− intercalation/extraction. Combined XRD, XPS, and Raman spectroscopy analyses reveal that the synergistic interplay between [AlCl4]− intercalation and surface adsorption governs the performance. Notably, Nb incorporation expands the interlayer spacing while preserving the crystal structure, facilitating rapid ion transport. At low scan rates, TiNbCTx operates as a battery-type material, achieving high capacity and energy density, whereas capacitive behavior dominates at higher rates, ensuring remarkable cycling stability. This work not only advances a promising cathode for AIBs but also provides fundamental insights into the rational design of MXene-based materials for energy storage.

Methods

Materials and characterization

Preparation of MAX

Ti (99.7 wt% pure, 300 mesh), Nb powder (99.7 wt% pure, 300 mesh), Al powder (99.7 wt% pure, 300 mesh), C powder (99.7 wt% pure, 300 mesh), C4H13NO·5H2O (99.7 wt% pure), and HF acid were purchased from Aladdin. In this study, the raw materials were accurately weighed according to a molar ratio of Ti:Nb:Al:C = 1:1:1.2:1. The weighed powders were mechanically ground in an agate mortar until a uniform mixture with fine particle size was achieved. The mixed powder was pre-pressed into pellets (13 mm diameter, 2 cm thickness) under 10 MPa uniaxial pressure for 5 min. This processing step enhances the precursor density, thereby facilitating homogeneous reactions during subsequent high-temperature sintering. The pellets were transferred into a crucible and subjected to calcination in a tube furnace under an argon atmosphere. The heating program was set to increase the temperature at a rate of 10 °C/min to 1000 °C, then at a rate of 5 °C/min to 1600 °C, where it was held for 1 h. After calcination, the controlled cooling rate under Ar atmosphere to 600 °C was implemented to mitigate potential thermal shock-induced damage to the tubular furnace. Furthermore, the sintered TiNbAlC MAX phase underwent mechanical fragmentation and ball-milling, yielding particles with an approximate size of 200 mesh.

Preparation of MXenes

The synthesized TiNbAlC MAX phase powder was gradually and repeatedly added to a mixed solution of 48% HF acid and 12 M concentrated hydrochloric acid in a 6:1 ratio. The mixture was then placed in a hydrothermal reactor and subjected to a 48 h etching process at 80 °C. After the etching, the resulting mixture was washed by repeated centrifugation (5000 rpm, 5 min) with deionized water to remove residual HF acid and impurities, until the pH of the supernatant reached approximately 6. The material was then treated using freeze-vacuum drying to obtain TiNbCTx MXene bulk material with an accordion-like structure. To achieve delamination, 1 g of the exfoliated multilayer TiNbCTx was mixed with 20 ml of 1 M TMAOH solution. After 15 h of intercalation, a water suspension of single- or few-layer MXene was successfully prepared. The suspension was then washed several times with deionized water and centrifuged to collect the single- or few-layer TiNbCTx MXene flakes. Finally, after freeze-vacuum drying, pure single- or few-layer TiNbCTx MXene powder was obtained.

Materials characterization

For TiNbAlC MAX, TiNbCTx MXene, and the cathode materials, we employed X-ray diffraction (XRD) to analyze their crystal structures. The microstructure and morphology of the materials were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were further utilized to investigate the chemical composition in detail. To accurately measure the thickness of the films, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used. Finally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to observe the fine morphology of the materials, and its electron diffraction capabilities were used to analyze the internal structure.

Assembly of Al−ion batteries and electrochemical measurements

The preparation of the cathode material for the AIB involves mixing TiNbCTx MXene, carbon black powder, and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder in a 7:2:1 mass ratio, using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, 99%, Alfa Aesar) as the solvent. The resulting slurry is then drop-cast directly onto a molybdenum foil current collector to form the cathode material, ensuring that the effective active material loading for each cell is 1.0–1.5 mg·cm−2. The chloroaluminate ionic liquid electrolyte is prepared by mixing 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([EMIm]Cl, 99.9%) and anhydrous high-purity aluminum chloride (AlCl3, 99.99%) in a 1:1.3 molar ratio. Finally, the MXene cathode, aluminum (Al) anode, AlCl3/[EMIm]Cl electrolyte, and Whatman GF/C microporous membrane separator are assembled together to complete the Swagelok-type Al battery in a glove box under an inert atmosphere. Constant current charge/discharge curves were recorded using a Neware battery cycler. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were performed in a voltage range of 0.1 to 2.3 V using an EC-Lab system (Biologic VMP-3) electrochemical workstation, at various scan rates (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 10 mV s−1). Additionally, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted over a frequency range from 1 MHz to 0.01 Hz.

Ex situ characterization of the MXene cathode

The cathode was disassembled from the Swagelok–type cells and placed in an Ar-filled glovebox, and washed with tetrahydrofuran, sonicated in dimethoxyethane for 1 h, and then dried in vacuum for 12 h. The dried cathode was then characterized via ex-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and FTIR spectroscopy. For the AIB cathode materials during charge/discharge cycling, XRD, XPS, and Raman spectroscopy were used to reveal key information regarding the structural changes, chemical state variations, ion transport mechanisms, and electronic conduction mechanisms of TiNbCTx MXene throughout the cycling process.

Computational method

Computational method: First-principles calculations based on density functional theory are performed by the Vienna ab-initio simulation package32, using the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof for the exchange-correlation functional. The van der Waals interaction is taken into account by means of the DFT-D3 method33. The plane wave cutoff energy is set to 500 eV, the total energy convergence threshold is set to 10−5 eV, the atomic force threshold is set to 0.01 eV/Å, and a Monkhorst-Pack k-sampling with 0.018 Å−1 spacing is used. The thickness of the vacuum layer in the slab models exceeds 15 Å to avoid unphysical interaction.

References

Larcher, D. & Tarascon, J.-M. Towards greener and more sustainable batteries for electrical energy storage. Nat. Chem. 7, 19–29 (2015).

Huggins, R., Advanced batteries: materials science aspects. Springer Science & Business Media. (2008).

Kittner, N., Lill, F. & Kammen, D. M. Energy storage deployment and innovation for the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 2, 1–6 (2017).

Meng, P., et al. A low-cost and air-stable rechargeable aluminum-ion battery. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106511 (2022).

Wang, G., Yu, M. & Feng, X. Carbon materials for ion-intercalation involved rechargeable battery technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 2388–2443 (2021).

Ng, K. L., Amrithraj, B. & Azimi, G. Nonaqueous rechargeable aluminum batteries. Joule 6, 134–170 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. The rechargeable aluminum battery: opportunities and challenges. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11978–11996 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Open-structured V2O5· nH2O nanoflakes as highly reversible cathode material for monovalent and multivalent intercalation batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602720 (2017).

Wu, C. et al. Electrochemically activated spinel manganese oxide for rechargeable aqueous aluminum battery. Nat. Commun. 10, 73 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. A novel aluminum-ion battery: Al/AlCl3-[EMIm] Cl/Ni3S2@ graphene. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600137 (2016).

Lin, M.-C. et al. An ultrafast rechargeable aluminium-ion battery. Nature 520, 324–328 (2015).

Mohammadi, A. V., Hadjikhani, A., Shahbazmohamadi, S. & Beidaghi, M. Two-dimensional vanadium carbide (MXene) as a high-capacity cathode material for rechargeable aluminum batteries. ACS Nano 11, 11135–11144 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Nb2CTx MXene cathode for high-capacity rechargeable aluminum batteries with prolonged cycle lifetime. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 40, 45254–45262 (2022).

Naguib, M. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 37, 4248–4253 (2011).

Deysher, G. et al. Synthesis of Mo4 VAlC4 MAX phase and two-dimensional Mo4VC4 MXene with five atomiclayers of transition metals. ACS Nano 14, 204–217 (2020).

Li, X. et al. MXene chemistry, electrochemistry and energy storage applications. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 389–404 (2022).

Barman, S. C. et al. Antibody-functionalized MXene-based electrochemical biosensor for point-of-care detection of vitamin D deficiency. Commun. Mater. 6, 31 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. MXene-assisted NiFe sulfides for high-performance anion exchange membrane seawater electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 16, 1319 (2025).

Ge, K., Shao, H., Lin, Z., Taberna, P.-L. & Simon, P. Advanced characterization of confined electrochemical interfaces in electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 196–208 (2025).

Anasori, B., Lukatskaya, M. R. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017).

Pang, J., Chang, B., Liu, H. & Zhou, W. Potential of MXene-based heterostructures for energy conversion and storage. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 78–96 (2022).

Pan, X. et al. 2D MXenes polar catalysts for multi-renewable energy harvesting applications. Nat. Commun. 14, 4183 (2023).

Pomerantseva, E. & Gogotsi, Y. Two-dimensional heterostructures for energy storage. Nat. Energy 2, 17089 (2017).

Zhao, D. et al. MXene (Ti3C2) vacancy-confined single-atom catalyst for efficient functionalization of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4086–4093 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Dual-functional V2C MXene assembly in facilitating sulfur evolution kinetics and Li-Ion Sieving toward Practical Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Mater. 26, 2300771 (2023).

Gao, L. et al. Applications of few-layer Nb2C MXene: narrow-band photodetectors and femtosecond mode-locked fiber lasers. ACS Nano 15, 954–965 (2021).

Wojciechowski, T. et al. Ti2C MXene modified with ceramic oxide and noble metal nanoparticles: synthesis, morphostructural properties, and high photocatalytic activity. Inorg. Chem. 58, 7602–7614 (2019).

Cao, Z. et al. Low-tortuous MXene (TiNbC) accordion arrays enabled fast ion diffusion and charge transfer in dendrite-free lithium metal anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 30, 2201189 (2022).

Ma, Q. et al. In-situ synthesis of niobium-doped TiO2 nanosheet arrays on double transition metal MXene (TiNbCTx) as stable anode material for lithium ion batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 617, 147–155 (2022).

Mashtalir, O. et al. Intercalation and delamination of layered carbides and carbonitrides. Nat. Commun. 4, 1716 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Pseudocapacitive heteroatom-doped carbon cathode for aluminum-ion batteries with ultrahigh reversible stability. Energy Environ. Mater. 5, e12733 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Acknowledgements

S.T. acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52203092) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, China (Grant No. 20232BAB204026). We thank for the resources from KAUST.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., X.L. and X.Z. conceived and supervised the project. S.T., Q.L., Y.J., G.S. and J.W. performed the experiments and characterizations. J.J. and U.S. performed the density functional theory calculations. S.T., Q.L. and J.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Kaitlyn Prenger and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Christopher Shuck and John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Q., Jin, J., Jiang, Y. et al. TiNbC MXene cathode for high-performance aluminum-ion batteries. Commun Mater 6, 113 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00829-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00829-9