Abstract

Understanding how renormalized quasiparticles emerge in strongly correlated electron materials provides a challenge for both experiment and theory. It has been predicted that distinctive spin and orbital screening mechanisms drive this process in multiorbital materials with strong Coulomb and Hund’s interactions. Here, we provide the experimental evidence of both mechanisms from angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy on RbFe2As2. We observe that the emergence of low-energy Fe 3dxy quasiparticles below 90K coincides with spin screening. A second process changes the spectral weight at high energies up to room temperature. Supported by theoretical calculations we attribute it to orbital screening of Fe 3d atomic excitations. These two cascading screening processes drive the temperature evolution from a bad metal to a correlated Fermi liquid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metals with strong electronic correlations are characterized by renormalized quasiparticles with large effective masses. At high temperatures, coherent quasiparticle excitations at low energies are absent. Instead, high-energy atomic excitations materialize as Hubbard bands and dominate the spectral function. Dispersive bands of coherent quasiparticles can emerge upon lowering the temperature due to the screening of the atomic degrees of freedom.

Describing these screening processes in hallmark strongly correlated multi-orbital d electron materials, such as iron-based superconductors (FeSCs) and ruthenates, remains challenging1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In these systems, the local Coulomb interaction U and a sizable Hund’s rule coupling J give rise to a multitude of unique correlation effects8,9,10,11,12,13. The notable sensitivity of their electronic properties on the Hund’s coupling J has led to their classification as so-called Hund’s metals10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Starting from high temperatures, Hund’s metals are predicted to separately screen the first orbital and then the spin degrees of freedom. They become Fermi liquids once both screening processes are complete23,24,25,26,27. Here, we experimentally demonstrate that two distinct screening processes drive the emergence of long-lived, heavy quasiparticles in the spectral function of FeSCs.

We investigate RbFe2As2, a hole-doped variant of the 122 parent compound BaFe2As2. It is one of the most strongly correlated representatives of the Hund’s metal FeSCs. Strong correlations were observed in low temperature thermodynamic and transport measurements, which found a large Sommerfeld coefficient of 127 mJ/molK2 and large effective masses up to 24me28,29,30. Nominally, 5.5 electrons occupy the five Fe 3d orbitals, which exhibit orbitally-differentiated correlation effects. The Fe 3dxy orbital is the most correlated, followed by the degenerate dxz and dyz orbitals. RbFe2As2 is a bad metal at high temperatures and displays an incoherent-coherent crossover when the temperature is lowered31,32,33. Fermi liquid behavior sets in below 45 K32. Evidence for spin screening was obtained from magnetic susceptibility measurements that show signatures of local moments at high temperatures and of a Pauli spin susceptibility below 90 K28,31.

We use angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) to follow the complete evolution of the Hund’s metal spectral function in RbFe2As2 across high and low energies and from high to low temperatures. We observe the sudden emergence of the dxy quasiparticle below 90 K. It coincides with the peak in the magnetic susceptibility28,31 that is related to spin screening. We identify an additional screening process that smoothly changes the dxz quasiparticle intensity as well as the intensity at high energies up to 6 eV. Based on a combination of a simple 5-orbital atomic model and density functional theory + dynamical mean-field theory (DFT + DMFT), we connect the high-energy intensity changes to atomic multiplet excitations. We propose that orbital screening is responsible and extends beyond room temperature. Orbitals are screened at higher temperatures and spins at lower temperatures, creating a cascade of successive screening processes.

Results and discussion

Low energies–quasiparticles

We first discuss the orbital-dependent evolution of the quasiparticle spectral weight as a function of temperature at low energies around the Fermi energy EF between (−0.08, 0.02) eV. Figure 1a–d presents ARPES spectra for selected temperatures. Surface bands were suppressed by temperature cycling (Methods, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S234). Data on a second, pristine sample show the same temperature dependence of the quasiparticle spectral weight34.

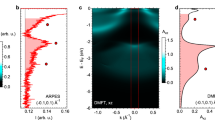

a–d ARPES spectra on sample 1 for selected temperatures. The green line in the inset sketches the momentum cut through the Brillouin zones. The dot indicates normal emission geometry. The spectra are divided by a Fermi–Dirac distribution, and the intensity scale is the same for all spectra. The red and blue squares in a–d indicate the momentum integration range for the EDC analysis shown in Fig. 2. e, f Spectral function calculated by DFT + DMFT at 96 K and projected onto the dxz and dxy orbitals, respectively. The momentum direction and range are the same as for ARPES.

kx and ky are equivalent momentum directions in the tetragonal crystal structure of RbFe2As2. For ease of readability, we label the measured momentum direction as kx throughout this manuscript. Orbital degeneracy implies that our results for the dxz orbital also apply to the dyz orbital.

Photoemission matrix elements for the experimental geometry favor emission from dxz, dxy, and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals (Supplementary Fig. S5)35,36,37. We focus here on the two-hole bands around the Brillouin center, which we identify as predominantly dxz and dxy character using DFT + DMFT calculations (Fig. 1e, f). This assignment is in agreement with previous ARPES studies on the sister compounds CsFe2As2 and KFe2As238,39,40. DMFT also captures the experimentally observed dispersion renormalization of the hole bands at EF in RbFe2As241. We present an analysis of the bands at the Brillouin zone corner in the Supplementary Fig. S334.

The spectra in Fig. 1 indicate that the quasiparticle bands broaden substantially and the dxy band vanishes at high temperatures. We quantify this behavior with a detailed analysis of energy and momentum distribution curves (EDCs and MDCs) in Fig. 2. Both the dxz and dxy quasiparticle peaks are well developed in the MDCs at low temperatures (Fig. 2a). Their intensity decreases with increasing temperature, and the dxy quasiparticle peak vanishes completely around 90 K (Fig. 2b). A clear dxz peak can be observed up 300 K.

a MDCs integrated within ±5 meV around EF. The dashed line shows a quadratic approximation of the high-temperature background within (−0.15, 0.6) Å−1. Temperature values (dark to bright) are labeled in (e). b Change of the spectral weight obtained from integrating the MDCs in a within the momentum range marked by the shaded areas. ΔI = I − IBkg is normalized to the value at 22 K. c EDCs at kF of the dxy hole band integrated within (0.44, 0.49) Å−1 as indicated by the blue box above the spectra in Fig. 1. d Spectral weight obtained from the EDCs in c by integration within the energy window marked by the shaded area. ΔI = I − I265K is normalized to the value at 22 K. The dxy spectral weight response is compared to the magnetic susceptibility from ref. 28. e Same as in c but at kF of the dxz hole band and integrated within (0.21, 0.26) Å−1. f FWHM of the dxz band obtained from fits to the MDCs in (a). The plotted values are the average FWHM within (−55 ± 15) meV and (0 ± 9) meV. Error bars represent the standard deviation. The raw MDCs and EDCs for sample 2 are shown in Supplementary Fig. S234.

A complementary EDC analysis at kF confirms this finding. The integrated area below the dxy peak vanishes around 90 K, beyond which the EDCs become temperature independent (Fig. 2c, d). The peak intensity of the dxz orbital continues to decrease at high temperatures (Fig. 2e). The integrated dxz peak area cannot be extracted for all temperatures since the peak broadens beyond the accessible energy range above EF. This broadening mimics recent ARPES results on Sr2RuO442. The dxz width in the EDCs sharpens below 85 K. The comparison of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) between EF and −55 meV in Fig. 2f illustrates the effect. Above 90 K, the FWHM at both energies is almost identical. Below that temperature, the FWHM at −55 meV saturates while it decreases more rapidly at EF (see also ref. 41). The qualitatively different behavior of the dxz and dxy orbitals is a consequence of orbital differentiation in FeSCs. The dxy orbital is the most correlated one in RbFe2As2 and in FeSCs in general9,10,17,19,30,43.

The appearance of the dxy quasiparticle at low temperatures was also observed in other FeSCs12,13,44,45. In addition, we compare here the dxy ARPES intensity with magnetic susceptibility measurements (Fig. 2d). The peak in χm coincides with the appearance of the dxy orbital. The temperature dependence of χm in RbFe2As2 was interpreted as a crossover from large fluctuating moments with a Curie behavior at high temperatures to screened moments with an enhanced susceptibility and Pauli behavior at low temperatures31,46. The scaling between the magnetic susceptibility and the Knight shift deviates at the same crossover temperature31. It is reminiscent of the ubiquitous Knight shift anomaly in heavy fermion materials that is caused by spin screening47. Spin screening in RbFe2As2 coincides with the coherence-incoherence crossover observed in resistivity31 as well as signatures in the Hall effect32 and elastoresistance33. The crossover temperature scales along the (K, Rb, Cs)Fe2As2 series and the signatures are in line with theoretical predictions of spin screening in FeSC in general14,17. To our knowledge, there is so far no microscopic theory that can account for this correlation.

The dxy quasiparticle spectral weight and the lifetime of the dxz orbital increase throughout the spin screening crossover in RbFe2As2. They signify the emergence of long-lived quasiparticles. The Fermi surface in the bad metal regime at high temperatures is dominated by short-lived dxz excitations.

High energies—atomic excitations

Spectral weight conservation dictates that the spectral function decreases at large positive or negative energies when it increases around EF. We therefore present temperature-dependent ARPES up to 8.5 eV in Fig. 3 to probe the occupied states at large binding energies.

a ARPES spectrum at 22 K and up to 8.5 eV. b EDCs integrated over the whole momentum range at 22 K and 175 K, respectively. c Intensity difference between spectra at 22 K and 175 K. e–h Same as a–d but with a zoom into the intermediate energy region up to 0.6 eV. All spectra are divided by a Fermi–Dirac distribution and are along the same momentum cut as in Fig. 1, as indicated by the sketch of the Brillouin zones at the bottom. i Temperature dependence of the intensity for three different energy windows as defined in (d, h). The intensity at 175 K is taken as reference. Error bars are determined on the basis of the standard deviation of the EDCs in (b).

The spectra show diffuse spectral weight beyond 0.3 eV in contrast to the sharp quasiparticle bands around the Fermi level (Fig. 3a, e). The intensity changes with temperature in an energy and momentum dependent fashion, which is highlighted in difference plots between the spectra at 22 K and 175 K in Fig. 3e, g. EDCs of the difference spectra (Fig. 3d, h) indicate three distinct energy regions ΔE1 = (6.1, 1.8) eV, ΔE2 = (1.8, 0.24) eV and ΔE3 = (0.24, 0) eV. The intensity increases with temperature in ΔE1, and it decreases in ΔE2 and ΔE3 (Fig. 3i). The intensity is temperature independent beyond 6.1 eV.

The integrated spectral weight within ΔE3 is predominantly due to photoemisison from the dxz orbital (Supplementary Fig. S534. The intensity is almost constant below 50 K and it decreases at higher temperatures. We have discussed the changes of the quasiparticle bands close to EF in detail above.

To identify the origin of the temperature dependence at high binding energies, we compare our experimental results with DFT calculations in Fig. 4a. The As 4p bands are located within ΔE1, while the Fe 3d bands lie within ΔE2. As expected, DFT reveals p–d orbital mixing. A change in orbital mixing due to thermal expansion is therefore an obvious interpretation of the different temperature evolution in ΔE1 and ΔE2. However, the following arguments render this scenario unlikely.

a DFT band structure of RbFe2As2. Dispersions are overall scaled by a factor of 1.15 to match the 4p band dispersion observed in ARPES (see Supplementary Fig. S434). The color indicates the contribution from Fe 3d and As 4p orbitals. DFT is plotted on top of the difference in ARPES intensity ΔI between 22 K and 175 K reproduced from Fig. 3c. Dashed circles mark areas of small and large response in ΔI as discussed in the main text. b EDC for the difference spectrum in (a). c, d Spectral function calculated by DFT + DMFT and projected onto the dxy and dxz orbitals, respectively. e EDC from d integrated over the momentum range indicated by the box in (e). f ARPES spectrum of RbFe2As2 taken in the first Brillouin zone. g EDC from f in the same momentum integration window as for the EDC in (e).

(1) When the lattice expands, then electrons overlap and hence 4p–3d mixing decreases. As a consequence, 3d (4p) spectral weight decreases (increases) in ΔE1 and increases (decreases) in ΔE2 (See Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. S634). The sign of the intensity change can therefore only be observed in case we predominantly photoemit from As 4p bands. The precise photon-energy dependence of the photoemission cross section is rather complex. However, 60 eV photons used here generally emphasize 3d spectral weight over 4p48,49,50,51.

2) The in-plane length change between 22 K and 175 K is ΔL/L = 5 × 10−333. DFT predicts that the relative orbital contribution changes by the same amount (see Supplementary Fig. S6)34. But the ARPES intensity change ΔI/I ≤ 2.5 × 10−2 is a factor of 5 larger.

3) The intensity changes most strongly away from the As 4p bands and very little where p–d overlap is largest (see dashed circles in Fig. 4a).

In the following, we show that our temperature-dependent ARPES data can be interpreted as screening of atomic multiplet excitations. The simplified atomic model calculation in Fig. 5 illustrates the excitation spectrum of an atomic site with five degenerate, interacting orbitals. They are occupied on average by Navg = 6 electrons. If isolated, the ground state of the atom is the high-spin configuration with S = 2 and N = 6. We expect three electron removal states and one addition state within an energy range on the order of the Coulomb interaction U and the Hund’s rule coupling J (main peaks in Fig. 5b).

a Probability of different occupation numbers for a coupling t = 0.03 to the bath. We used a Kanamori interaction with U = 5 and J = 0.6, which are typical values of Coulomb interaction and Hund’s coupling in Fe-based superconductors. b Corresponding spectral function. c–f Same as (a) and (b) but for different coupling t. g Spectral function for different values of the Coulomb interaction U and at J = 0.6. h Spectral function for different values of the Hund’s rule coupling J and at U = 5. Both g and h are calculated at t = 0.3. We mark electron removal states that depend on U and J with a light background and those that only depend on J with dark background.

We can model screening by coupling the atomic site to a discretized bath with five states through the hybridization amplitude t. The larger t, the more the electron number fluctuates due to charge exchange with the bath. We plot the probability of different occupation numbers for selected t in Fig. 5a, c, e. The corresponding spectral functions are shown in Fig. 5b, d, f.

Peaks emerge in the spectral function at the Fermi level, and their intensity increases with t. The peaks correspond to the renormalized quasiparticle peaks in the full DMFT model. This effect may be associated with the increase of the ARPES intensity close to the Fermi level within ΔE3.

At high energies (shaded regions), several peaks appear in the atomic spectrum as a function of t and all shift in energy. The complexity is a consequence of the multi-orbital nature and various aspects of it have been studied previously23,26,52,53,54. We can identify two groups of excitations from a detailed analysis of their U and J dependence (Fig. 5g, h). The energy of states in the light shaded region (−8 eV to −4 eV) depends on both U and J as is typical for Hubbard bands. Their overall intensity decreases with t. The states in the dark shaded region (−3 eV to −1 eV) only depend on J and were previously termed Hund bands54. In contrast to the Hubbard bands, their intensity varies non-monotonically with t.

We can identify atomic excitations both in the DFT + DMFT and ARPES spectral function of RbFe2As2. Dispersionless bands appear at approximately 0.3 eV and 1 eV in DFT + DMFT projected onto the dxy orbital (Fig. 4c). All other orbitals possess similar weakly dispersing bands (Fig. 4d). They are separated from the As 4p bands and do not appear in DFT calculations. Therefore, we interpret them as multiplet atomic excitations, not captured within a DFT-only approach. Our ARPES spectra show a corresponding peak (Fig. 4f), which is most obvious as a shoulder at 1 eV in the EDC at Γ (Fig. 4g). The EDC from DMFT (Fig. 4e) matches the ARPES measurement. Local interactions are therefore well suited to describe RbFe2As2. The dispersionless bands are reminiscent of Hubbard bands in FeSe49,50,51. From the size of U and J, we expect the multiplet to extend several eV below EF41. However, it is challenging to identify atomic excitations at larger energies due to the overlap with the As 4p bands.

A comparison between the ARPES data and the atomic model from Fig. 5 suggests that states within ΔE1 correspond to the Hubbard bands of the atomic model (light shaded region). Similarly, states within ΔE2 correspond to the Hund bands (dark shaded region). This distinction and their different temperature dependence is a consequence of the multi-orbital nature of RbFe2As2. Understanding this complexity allows us to identify screening as the basic underlying mechanism that drives the temperature evolution of the high-energy ARPES intensity.

Recent temperature-dependent DMFT calculations of a three-orbital Hund–Hubbard model with sizable J confirm this interpretation26. The spectral function has the opposite temperature dependence around the low-energy atomic excitation than around those at high energies. The sign agrees with our experimental observation.

Discussion—spin and orbital screening

The temperature dependence of the high-energy spectral weight (Fig. 3i) does not change significantly across the spin screening temperature of 90 K that we identified from the magnetic susceptibility. Simultaneously, the low-energy dxz quasiparticle peak height (Fig. 2b) continuously and smoothly decreases with temperature. Therefore, a second screening mechanism apart from spin screening is active in RbFe2As2 up to at least 300 K.

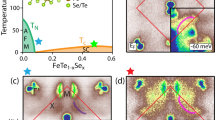

Several theoretical studies identify a separation of spin and orbital screening as a defining feature of Hund’s metals (see Fig. 6)23,24,25,26. Orbital screening leads to the formation of an orbital singlet and is predicted to set in far above room temperature. The wide crossover regime is characterized by a bad metallic behavior of incoherent quasiparticles. At low temperatures, additional spin screening of local moments favors a spin singlet state and leads to the appearance of long-lived quasiparticles.

A comparison of the resistivity R (from ref. 33), the magnetic susceptibility χm (from ref. 28) and the quasiparticle spectral weight change ΔI of the dxy and dxz orbitals (from Figs. 2d and 3i). Top: Sketches illustrate orbital and spin screening in the example of three atomic orbitals (circular segments) occupied by two electrons (adapted from ref. 71). Right: Hund’s rule coupling favors a parallel spin alignment of both electrons in the atomic orbitals. Center: Orbital screening (second circle) of the atomic configuration leads to an orbital singlet. Hund’s rule coupling favors the large spin state. Left: Spin screening (third circle) of the large moment then leads to the formation of a spin singlet. The Fermi liquid regime has a constant χm and a T2 dependence of R. Spin screening is identified as the crossover between Pauli and Curie behavior in χm. It coincides with a crossover in the resistivity (slope change). The dxy quasiparticle emerges once spin screening sets in. Orbital screening leads to a spectral weight transfer from the Hubbard bands to the dxz quasiparticle peak. Its intensity increases over the whole screening temperature range.

The characteristic spectral weight changes both at low and at high energies observed in our work provide direct experimental evidence for spin-orbit separation in RbFe2As2. The sudden appearance of the dxy quasiparticle at 90 K in RbFe2As2 coincides with spin screening. We propose that the continuous changes of the ARPES intensity at low and high energies are in turn the result of orbital screening. This combined action drives the formation of long-lived, renormalized quasiparticles at the Fermi surface and turns a bad metal into a heavy Fermi liquid. We summarize this behavior in Fig. 6. The spin screening regime is identified by a crossover in the susceptibility, which coincides with a crossover in the resistivity towards a Fermi liquid behavior. Both transport and thermodynamics probe the behavior of the quasiparticles. The corresponding dxz and dxy quasiparticle intensities signify the spectral changes in the two distinct regimes of spin and orbital screening.

Our study serves as a benchmark for theoretical descriptions of Hund’s metals. Besides separate spin and orbital screening, we observe strong orbital differentiation. Models that include both effects are desirable to obtain a comprehensive picture of correlated multi-orbital systems.

Methods

ARPES experiments

We synthesized single crystals of RbFe2As2 using growth methods described earlier55. The samples were prepared and glued onto sample holders for ARPES experiments inside an argon glovebox to minimize air exposure. ARPES experiments were performed at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source at beamline 5-2. All samples were cleaved in situ below 30 K. The pressure during cleaving and measurements was below 3 × 10−11 torr. RbFe2As2 is known to develop a \(\sqrt{2}\times \sqrt{2}\) surface reconstruction, which is common in 122 FeSC38,56,57. To remove spectral signatures from the surface bands, we cycled the temperature up to 300 K and spectra were acquired during cooling (sample 1). Additional analysis was performed on spectra during warm-up (sample 2, Supplementary Figs. S1 and S234). We used a photon energy of 60 eV with linear vertical polarization.

Quantitative spectral weight measurements as a function of temperature are challenging. On one hand, the soft nature of RbFe2As2 crystals leads to uneven sample surfaces after cleaving, with only small areas of homogeneous, flat surfaces. Therefore, we use a small beam spot of approximately 50 μm diameter and map the photoemission signal on the whole sample surface. This optimization procedure is repeated after each temperature change to correct for thermal expansion of the sample manipulator and ensure that we probe the same sample spot each time. On the other hand, drifts of the photon flux lead to overall changes in the photoemission intensity. Therefore, we obtain spectra down to 8.5 eV binding energy, which is beyond the As 4p bands and Fe 3d atomic excitations. No temperature-induced changes are expected in this energy range. Our careful alignment procedures lead to an overall variation of intensity in this region of only 4%. We normalize all our spectra to the intensity between 7 eV and 8 eV. Afterwards, the data fall on top of each other between 6.5 eV and 8.5 eV. All intensities are corrected for detector non-linearities.

DFT + DMFT calculations

For the DFT + DMFT calculations, we performed fully charge self-consistent calculations based on Wien2K v23.258,59 in the Generalized-gradient approximation60 and a projection on the subspace of the correlated Fe 3d orbitals61,62 in the window [−6, 13.6]eV (As p, Fe d and higher energy unoccupied states). For solving the impurity model we used continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo method in the hybridization expansion, using the segment picture63,64,65. We used interaction parameters of Uavg = 4 eV, Javg = 0.8 eV, representative for the iron-based pnictides66, in the definition of Slater integrals67, and the nominal double counting correction68,69 with N = 5.5 nominal filling. The DMFT calculations were done at a temperature of T = 96 K, unless indicated otherwise. Stochastic analytical continuation70 was used to obtain real frequency data.

Atomic model

For the simplified impurity model, we calculated the spectral function using exact diagonalization of a degenerate five-orbital atom system, with each orbital coupled to one non-interacting bath site, and the same form of the local Coulomb interaction as for the DMFT calculation (see above). The hopping parameter t corresponds to the hybridization amplitude to the bath of each orbital (identical for all orbitals). The impurity local chemical potential (energy shift between impurity and bath sites) was adjusted for N = 6 electron average impurity filling.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The custom codes implementing the calculations of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Dai, P. Antiferromagnetic order and spin dynamics in iron-based superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 855–896 (2015).

Dagotto, E. Colloquium: The unexpected properties of alkali metal iron selenide superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 849–867 (2013).

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Electronic correlations in the iron pnictides. Nat. Phys. 5, 647–650 (2009).

Hayes, I. M. et al. Scaling between magnetic field and temperature in the high-temperature superconductor \({{{\rm{BaFe}}}}_{2}{({{{\rm{As}}}}_{1-x}{{{\rm{P}}}}_{x})}_{2}\). Nat. Phys. 12, 916–919 (2016).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Orbital physics in transition-metal oxides. Science 288, 462–468 (2000).

Schaffer, R., Lee, E. K.-H., Yang, B.-J. & Kim, Y. B. Recent progress on correlated electron systems with strong spin-orbit coupling. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 094504 (2016).

Mackenzie, A. P., Scaffidi, T., Hicks, C. W. & Maeno, Y. Even odder after twenty-three years: the superconducting order parameter puzzle of Sr2RuO4. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 40 (2017).

Neupane, M. et al. Observation of a novel orbital selective Mott transition in Ca1.8Sr0.2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 097001 (2009).

Yi, M., Zhang, Y., Shen, Z.-X. & Lu, D. Role of the orbital degree of freedom in iron-based superconductors. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 57 (2017).

de’ Medici, L., Giovannetti, G. & Capone, M. Selective mott physics as a key to iron superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 177001 (2014).

Kugler, F. B., Lee, S.-S. B., Weichselbaum, A., Kotliar, G. & von Delft, J. Orbital differentiation in Hund metals. Phys. Rev. B 100, 115159 (2019).

Yi, M. et al. Observation of universal strong orbital-dependent correlation effects in iron chalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 6, 7777 (2015).

Huang, J. et al. Correlation-driven electronic reconstruction in FeTe1−xSex. Commun. Phys. 5, 29 (2022).

Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Coherence-incoherence crossover in the normal state of iron oxypnictides and importance of Hund’s rule coupling. N. J. Phys. 11, 25021 (2009).

de’ Medici, L. Hund’s coupling and its key role in tuning multiorbital correlations. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205112 (2011).

de’Medici, L., Mravlje, J. & Georges, A. Janus-faced influence of Hund’s rule coupling in strongly correlated materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 256401 (2011).

Yin, Z. P., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Kinetic frustration and the nature of the magnetic and paramagnetic states in iron pnictides and iron chalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 10, 932–935 (2011).

Georges, A., Medici, L. D. & Mravlje, J. Strong correlations from Hund’s coupling. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 137–178 (2013).

Backes, S., Jeschke, H. O. & Valentí, R. Microscopic nature of correlations in multiorbital AFe2As2 (A = K,Rb,Cs): Hund’s coupling versus Coulomb repulsion. Phys. Rev. B 92, 195128 (2015).

Stadler, K., Kotliar, G., Weichselbaum, A. & von Delft, J. Hundness versus mottness in a three-band Hubbard-Hund model: on the origin of strong correlations in Hund metals. Ann. Phys. 405, 365–409 (2019).

Villar Arribi, P. & de’ Medici, L. Hund’s metal crossover and superconductivity in the 111 family of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 104, 125130 (2021).

Crispino, M. et al. Paradigm for finding d-electron heavy Fermions: the case of Cr-doped CsFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 076504 (2025).

Stadler, K. M., Kotliar, G., Weichselbaum, A. & von Delft, J. Hundness versus Mottness in a three-band Hubbard-Hund model: on the origin of strong correlations in Hund metals. Ann. Phys. 405, 365–409 (2019).

Deng, X. et al. Signatures of mottness and hundness in archetypal correlated metals. Nat. Commun. 10, 2721 (2019).

Horvat, A., Zitko, R. & Mravlje, J. Non-Fermi-liquid fixed point in multi-orbital Kondo impurity model relevant for hund’s metals. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1907.07100 (2019).

Stadler, K. M., Kotliar, G., Lee, S.-S. B., Weichselbaum, A. & von Delft, J. Differentiating Hund from Mott physics in a three-band Hubbard-Hund model: temperature dependence of spectral, transport, and thermodynamic properties. Phys. Rev. B 104, 115107 (2021).

Suzuki, H. et al. Distinct spin and orbital dynamics in Sr2RuO4. Nat. Commun. 14, 7042 (2023).

Khim, S. et al. A calorimetric investigation of RbFe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 254, 1600208 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Heat transport in RbFe2As2 single crystals: evidence for nodal superconducting gap. Phys. Rev. B 91, 024502 (2015).

Eilers, F. et al. Strain-driven approach to quantum criticality in AFe2As2 with A = K, Rb, and Cs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 237003 (2016).

Wu, Y. P. et al. Emergent Kondo lattice behavior in iron-based superconductors AFe2As2 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 147001 (2016).

Xiang, Z. J. et al. Incoherence-coherence crossover and low-temperature Fermi-liquid-like behavior in AFe2As2 (A = K, Rb, Cs): evidence from electrical transport properties. J. Phys. 28, 425702 (2016).

Wiecki, P. et al. Emerging symmetric strain response and weakening nematic fluctuations in strongly hole-doped iron-based superconductors. Nat. Commun. 12, 4824 (2021).

Supplementary material.

Yi, M. et al. Nematic energy scale and the missing electron pocket in FeSe. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041049 (2019).

Pfau, H. et al. Detailed band structure of twinned and detwinned BaFe2As2 studied with angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 99, 035118 (2019).

Li, Y.-F. et al. Orbital ingredients and persistent Dirac surface state for the topological band structure in FeTe0.55Se0.45. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021043 (2024).

Richard, P. et al. Van Hove singularities, chemical pressure and phonons: an angle-resolved photoemission study of KFe2As2 and CsFe2As2. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.00193 (2018).

Yoshida, T. et al. Orbital character and electron correlation effects on two- and three-dimensional Fermi surfaces in KFe2As2 revealed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Front. Phys. 2, 17 (2014).

Fang, D. et al. Observation of a Van Hove singularity and implication for strong-coupling induced Cooper pairing in KFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 92, 144513 (2015).

Chang, M.-H. et al. Dispersion kinks from electronic correlations in an unconventional iron-based superconductor. Nat. Commun. 15, 9958 (2024).

Hunter, A. et al. Fate of quasiparticles at high temperature in the correlated metal Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 236502 (2023).

Diehl, J., Backes, S., Guterding, D., Jeschke, H. O. & Valentí, R. Correlation effects in the tetragonal and collapsed-tetragonal phase of CaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 90, 085110 (2014).

Yi, M. et al. Observation of temperature-induced crossover to an orbital-selective Mott phase in AxFe2−ySe2 (A = K, Rb) superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 67003 (2013).

Pu, Y. J. et al. Temperature-induced orbital selective localization and coherent-incoherent crossover in single-layer FeSe/Nb:BaTiO3/KTaO3. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115146 (2016).

Hardy, F. et al. Evidence of strong correlations and coherence-incoherence crossover in the iron pnictide superconductor KFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 27002 (2013).

Jiang, M., Curro, N. J. & Scalettar, R. T. Universal knight shift anomaly in the periodic anderson model. Phys. Rev. B 90, 241109 (2014).

Yeh, J. & Lindau, I. Atomic subshell photoionization cross sections and asymmetry parameters: 1 ⩽ z ⩽ 103. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 32, 1–155 (1985).

Evtushinsky, D. V. et al. Direct observation of dispersive lower Hubbard band in iron-based superconductor FeSe. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1612.02313 (2016).

Watson, M. D. et al. Formation of Hubbard-like bands as a fingerprint of strong electron-electron interactions in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 95, 81106 (2017).

Pfau, H. et al. Quasiparticle coherence in the nematic state of FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 104, L241101 (2021).

Huang, L., Wehling, T. O. & Werner, P. Electronic excitation spectra of the five-orbital Anderson impurity model: from the atomic limit to itinerant atomic magnetism. Phys. Rev. B 89, 245104 (2014).

Aucar Boidi, N., Fernández García, H., Núñez Fernández, Y. & Hallberg, K. In-gap band in the one-dimensional two-orbital Kanamori-Hubbard model with interorbital Coulomb interaction. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043213 (2021).

Środa, M., Mravlje, J., Alvarez, G., Dagotto, E. & Herbrych, J. Hund bands in spectra of multiorbital systems. Phys. Rev. B 108, L081102 (2023).

Chu, J.-H., Analytis, J. G., Kucharczyk, C. & Fisher, I. R. Determination of the phase diagram of the electron-doped superconductor \(\,{\mbox{Ba}}{({{\mbox{Fe}}}_{1-x}{{\mbox{Co}}}_{x})}_{2}{{\mbox{as}}}_{2}\). Phys. Rev. B 79, 014506 (2009).

Hoffman, J. E. Spectroscopic scanning tunneling microscopy insights into Fe-based superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124513 (2011).

Pfau, H. et al. Low work function in the 122-family of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 034801 (2020).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k, An Augmented Plane Wave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties. (Karlheinz Schwarz, Techn. Universität Wien, Austria), ISBN 3-9501031-1-2 (2018).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k: an APW+lo program for calculating the properties of solids. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 074101 (2020).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Aichhorn, M. et al. Dynamical mean-field theory within an augmented plane-wave framework: assessing electronic correlations in the iron pnictide LaFeAsO. Phys. Rev. B 80, 085101 (2009).

Ferber, J., Foyevtsova, K., Jeschke, H. O. & Valentí, R. Unveiling the microscopic nature of correlated organic conductors: the case of κ-(ET)2Cu[N(CN)2]BrxCl1−x. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205106 (2014).

Werner, P., Comanac, A., de’ Medici, L., Troyer, M. & Millis, A. J. Continuous-time solver for quantum impurity models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 076405 (2006).

Wallerberger, M. et al. Updated core libraries of the Alps project. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1811.08331 (2018).

Bauer, B. et al. The Alps project release 2.0: open source software for strongly correlated systems. J. Stat. Mech. 2011, P05001 (2011).

van Roekeghem, A., Vaugier, L., Jiang, H. & Biermann, S. Hubbard interactions in iron-based pnictides and chalcogenides: Slater parametrization, screening channels, and frequency dependence. Phys. Rev. B 94, 125147 (2016).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: orbital ordering in Mott-Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52, R5467–R5470 (1995).

Haule, K., Birol, T. & Kotliar, G. Covalency in transition-metal oxides within all-electron dynamical mean-field theory. Phys. Rev. B 90, 075136 (2014).

Haule, K. Exact double counting in combining the dynamical mean field theory and the density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 196403 (2015).

Beach, K. S. D. Identifying the maximum entropy method as a special limit of stochastic analytic continuation. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.cond-mat/0403055 (2004).

Georges, A. & Kotliar, G. The Hund-metal path to strong electronic correlations. Phys. Today 77, 46–53 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the valuable discussions with Jan von Delft, Rudi Hackl, Yu He, Patrick Kirchmann, Seung-Sup Lee, and Brian Moritz. This work is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under Award Number DE-SC0024135. R.V. acknowledges support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—CRC 1487, “Iron, upgraded!”—project number 443703006, as well as QUAST-FOR5249—project number 449872909. M.H. and D.L. acknowledge the support of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. This research used resources of the Advanced Light Source, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.P. conceived the experiment. G.-Y.C. and H.-H.W. synthesized the bulk single crystals. H.P., N.G. and D.L. performed the ARPES measurements with assistance from M.H. M.-H.C. performed the ARPES data analysis with assistance from H.P., R.V., S.B. and H.P. conceived the theoretical analysis. S.B. performed the DFT + DMFT calculations and those for the atomic model. S.B., D.L., M.H., S.-K.M., R.V., Z.-X.S. and H.P. interpreted the results of this study. H.P., S.B. and R.V. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, MH., Backes, S., Lu, D. et al. Observation of two cascading screening processes in an iron-based superconductor. Commun Mater 6, 157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00881-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00881-5