Abstract

Metallic nanosponges are well known to exhibit distinct mechanical properties that are considered to originate from the interwoven mechanics of the nanoscale ligaments as individual units and as a network. A comprehensive understanding of the physical mechanisms behind these properties spanning over several length scales is to date lacking. Here, by employing a correlative and scale-bridging workflow combining non-destructive 3D electron and X-ray tomography, in situ mechanics and experimentally-informed real-size modelling, we reveal the atomic origins of size dependent deformation mechanisms of nanoporous gold ranging from sub-ten to hundreds of nanometers. A realistic distribution of geometries and sizes of the ligaments appears to be crucial to accurately capture the mechanical response of nanoporous gold, including deformation gradients and plasticity. Our workflow demonstrates the potential for exploring the atomistic mechanisms of material plasticity with geometrical complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoporous gold (npg) has recently received intensive attention due to its nanoscale dimensions, sponge-like open porous 3D architecture, and high surface-to-volume ratio1,2,3, featuring its potential use as an actuator4,5, catalyst6,7 or sensor8,9 material. Npg is also regarded as a model material to study size effects in small-scale mechanics1,10,11,12,13, since the characteristic length scale, the ligament size (L), can be tailored within the nm-µm range by the synthesis route or additional thermal post-annealing treatments1,14,15,16 without significantly changing the solid fraction (\(\varphi\)) of the network12,17. Npg shows a strong dependency of yielding and flow behavior on the ligament size. In experimental data from uniaxial compression1,11,12,13,18, a “smaller is stronger” trend has been confirmed down to ligament sizes of 10 nm and explained in terms of source-limited plastic deformation18. The impact of \(\varphi\) on the effective mechanical properties of porous structures can be described by the Gibson-Ashby scaling laws19. Although the applicability of the scaling laws to npg has been widely debated20,21,22,23,24,25, the studies on the size effects in strength and stiffness of npg often use these laws to make the experimental data comparable.

Several experiments26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 and atomistic simulations23,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 have been carried out to investigate the deformation mechanisms of npg. Size effects in small-scale plasticity of nanostructured metallic materials, such as nanopillars or nanocrystalline structures, are well established42. However, there is no comprehensive understanding of the size-dependent deformation mechanisms in nanoporous metals, in which the combined effects of the structural heterogeneity and high surface-to-volume ratio on the surface dislocation nucleation-controlled plasticity need to be considered. Most of the atomistic simulations were performed on idealized porous structures23,35,36,37,38,39,40, such as spinodal structures23,37,38,40 which exhibit much lower strength and stiffness compared to realistic npg networks43. In the past decade, X-ray14,44, transmission electron microscopy45 (TEM) and focused ion beam43,46,47 (FIB) based three-dimensional (3D) tomography techniques have been used for topological and morphological characterization of npg2. These studies provide 3D structural information that could in principle be used for simulations. However, to date, no direct comparison between experiments and simulations on the same sample has been reported.

In this study, we apply scale-bridging non-destructive tomography techniques to capture topological and surface morphological features of npg with a characteristic size ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers. In situ mechanical compression tests are performed on npg and combined with tomography studies before and after deformation, enabling quantitative deformation mapping using digital volume correlation (DVC). Experimentally-derived 3D microstructural data are used as input structures for cross-scale atomistic and continuum modelling. Large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are performed on the small-scale (sub-ten to tens of nanometers characteristic length scale) experimentally-informed npg to accurately capture the atomic origins of deformation mechanisms. The simulation results are correlated with high-resolution TEM observations of defect structures, providing insight into the effect of strain gradients on dislocation-based deformation mechanisms. Finite element (FE) simulations are performed on the large-scale (with a characteristic length scale of hundreds of nanometers) experimentally informed npg. By comparing the dislocation structures revealed by TEM with the deformation gradients, obtained using both DVC and FE methods, we can clearly identify different mechanisms at work for the different sizes. Based on this, different material models have to be applied and are evaluated in simulations to represent the mechanical response of realistic nanoporous network structures.

Results and discussion

Non-destructive 3D analyses & in situ mechanical testing

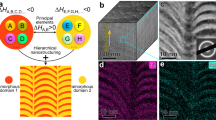

The correlative workflow combining in situ micromechanical testing with non-destructive tomographic techniques on micropillars before and after compression is illustrated in Fig. 1. Npg is synthesized by chemical dealloying12,48 of an Au-Ag solid solution featuring a mean ligament size of L ~30 nm (SI Fig. 1a–d). For scale-bridging analyses, one batch of the as-prepared material is additionally coarsened by a post-annealing treatment to achieve a mean ligament size of L ~300 nm (SI Fig. 1d–e). Details about the synthesis route can be found in the experimental description. A ligament size distribution is obtained on both length scales, which is broadened upon annealing by a factor of about two (SI Fig. 1f). Regarding the dependency of yield strength on the ligament size, nanoscale sponges are obtained featuring an intrinsic distribution of mechanical strength by its differently sized interconnected nano-struts. Upon mechanical loading (see the section below), complex stress fields are additionally superimposed, as triggered by the 3D mesoscale sponge topology and surface morphology. Npg pillar samples are site-specifically fabricated (from a single grain in npg) by advanced FIB lift-out techniques on top of tomography tips on both respective length scales (SI Fig. 2, SI Fig. 3). To analyze the crystal structure and pillar orientation after FIB preparation, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) is performed in case of the small-scale sample, while electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) is employed for the large-scale sample. Both diffraction techniques demonstrate the single crystalline nature of each pillar on its respective length-scale. Only a small defect-enriched layer is identified by SAED in the outer shell of the small-scale sample as a result of FIB damage (SI Fig. 4). Furthermore, residual Ag content of ~6 at.-% is still present in the samples, which is concentrated in the as-dealloyed material in local Ag-rich clusters with a size of about 20 nm and up to 25 at.-% Ag as shown in the chemical mapping derived from energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) in TEM (SI Fig. 5). This agrees well with earlier observations of residual Ag content in npg of ~6 at.-%49. Both obtained pillar samples, as well as the respective 3D network structures derived from non-destructive tomography methods, are presented in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. The corresponding tomographic tilt-series and animations of the 3D reconstructions are shown in Supplementary Movies 1–4. On the small length-scale, a pillar with a ligament size of L ~30 nm, a pillar diameter of Ø ~400 nm and a pillar orientation along <137> is prepared, while on the larger scale a pillar with a ligament size of L ~300 nm, a pillar diameter of Ø ~4 µm and a pillar orientation along <013> is obtained. The derived 3D structural information is used to evaluate the comparability of both network geometries, by 3D analyses of topology and surface morphology, i.e., local thickness distribution of ligaments, relative density, scaled genus density and interface shape distribution function (ISD). The following results are hereby obtained: During annealing the average local thickness of the ligaments increases from ~28 nm in the small-scale sample to ~260 nm in the large-scale sample (SI Fig. 6a, b). The calculated relative density of the large-scale sample (~39%) is slightly higher compared to the small-scale sample (~35%), which might result from a slight densification of the sponge network upon annealing. The average connectivity of the network structure, which is indicated by the scaled genus density (defined by Eqs. 9–11) stays nearly constant, yielding 0.076 (small-scale sample) and 0.074 (large-scale sample) and is in close agreement with previous literature data on npg43 and very different from artificial networks based on e.g. spinodal or gyroid structures (c.f. SI Fig. 7). Last to mention is the observation of a shift of the ISD pattern (surface morphological characterization) along the minimal surface (\({\kappa }_{1}=-\,{\kappa }_{2} < 0\)) after annealing (SI Fig. 8), which happens since the coarsening process is driven by the minimization of surface free energy50.

The 3D network structure of FIB prepared npg pillars is obtained by (1) non-destructive tomography and used as input for (2) correlative mechanical simulations. After (3) experimental compression the 3D network is (4) visualized again by means of the tomographic techniques. The resulting experimental and simulated stress-strain response, strain fields and crystal defects are compared and evaluated. For small ligament length (L ~30 nm) 360° electron tomography (ET) is combined with in situ TEM compression testing and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while on larger length scale (L ~300 nm) nano X-ray computed tomography (nano-CT) is combined with finite element (FE) crystal plasticity simulations and in situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) compression testing.

a Npg pillar geometries (SEM micrographs) as prepared by advanced FIB techniques on top of tomography tips featuring a ligament size of L ~30 nm and a pillar diameter of Ø ~400 nm on smaller scale, and a ligament size of L ~300 nm and a pillar diameter of Ø ~4 µm on larger scale. b Non-destructive tomography: Tomographic tilt series (left) and 3D structural information (surface rendering of 3D reconstruction), obtained by the tomographic techniques (right). The tilt series (here shown: at 0° tilt angle) is acquired on the FIB-prepared pillars by means of 360°-ET in high angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode and nano-CT in high-resolution and absorption-contrast (AC) mode on the different length scales, respectively. The 3D structural information is used for precise 3D analyses of network geometry, morphology/topology as well as input for experimentally informed simulations. c In situ pillar compression in the TEM (small-scale sample) and SEM (large-scale sample). Micrographs (left) shown here in the undeformed (ε = 0%) and fully deformed state after unloading (from ε = 16%) and corresponding stress-strain plots (right).

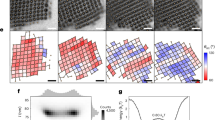

Figure 2c shows the results of in situ compression testing in TEM (Supplementary Movie 5) and SEM (Supplementary Movie 6) up to an engineering strain of 16% on both length scales. Unloading segments are performed in regular strain-intervals to calculate the sponge’s Young’s modulus, and to evaluate plasticity and densification. The mechanical behavior is described in both cases by an initial ‘elastic’-like loading of the entire network structure, characterized by a constant slope up to a strain of ~5% at which a drastic change of slope occurs. This point is defined as the global yield point. The corresponding stress describes the strength of the nanoporous network and amounts to \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}}}^{30{{{\rm{nm}}}}}=48\,\)MPa (small-scale sample) and \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}}}^{300{{{\rm{nm}}}}}=50\,\)MPa (large-scale sample). These values are used to calculate the yield strength of the solid (yield strength of ligaments) by using the macroscopic foam scaling laws derived from Gibson and Ashby19 for comparison with former literature studies1. The scaling laws are further used to re-calculate the solid Young’s modulus (Young’s modulus of ligaments) from the sponge Young’s modulus, which is \({E}^{30{{{\rm{nm}}}}}=1.7\,\)GPa and \({E}^{300{{{\rm{nm}}}}}=3.4\,\)GPa. Please refer to the Supplementary information on pages 10-12 (SI, Fig. 9 and SI note 1) for further details on the applicability of the Gibson and Ashby scaling equations. Furthermore, all mechanical properties of npg samples under in situ compression tests are summarized in Table S1 in the Supplementary information.

After the global yield point the stress increases, which is attributed to strain hardening (and slight densification effects, i.e., vanishing pore space/touching ligaments, since the sponge elastic modulus is slightly increasing). However, severe plasticity takes place nearly immediately after loading (before the global yield point), which is indicated by the remanent plastic strain in early unloading segments (before ~5% strain). This early plasticity concentrates at local weak spots of the network structure and can be visualized by applying digital image correlation analysis (DIC) to in situ compression series in the SEM (SI, Fig. 10). The DIC further reveals that plasticity occurs very inhomogeneously and localized in npg, which leads to the evolution of local strain gradients during deformation (SI, Fig. 10, Supplementary Movie 7). Therefore, weak spots in the network structure can easily affect the overall network stability and trigger, e.g., buckling of the struts during micropillar compression (SI, Figs. 10–11, Supplementary Movies 8–9). In the large-scale sample, early plasticity and inhomogeneous deformation occur primarily in the upper part of the pillar (see SI, Fig. 12, Fig. 5b), while plasticity in the small-scale sample evolves in a slightly more homogeneous manner (Supplementary Movies 5–6, Fig. 2c). This difference influences the subsequent densification behavior. In the large-scale sponge, densification begins in a highly localized manner near the indenter contact in the upper pillar region at a strain of 0.09. At this point, some ligaments start to come in contact with each other (see white arrow in SI Fig. 12). This contributes to hardening and is also evident in the stress-strain plot in Fig. 5, where a steeper stress increase occurs after the 6th loading cycle (strain of 0.09). However, due to its localized nature and the limited compression applied in this study (strain of 0.16), the overall impact of densification remains relatively minor. For higher compression levels beyond a strain of 0.16, its influence is expected to be significantly more pronounced. For the small-scale sponge, densification does not play a role up to the maximum experimental strain of 0.16, as plastic deformation is more uniformly distributed. Please also refer to the Supplementary information on pages 15−18 (SI note 2) for a more detailed discussion on what triggers strain localization, inhomogeneous deformation, and the role of local densification in the mechanical response of the small-scale and large-scale sample.

Correlative computational modelling

An experimental 3D structure derived from the small ligament size (L ~30 nm) npg using 360°-ET is used as an input for reconstructing atomistic configurations for large-scale atomistic simulations (Fig. 1). This experimentally informed (ExIn) approach allows a one-to-one comparison of experimental and simulated mechanical response. The correlation of local stress fields and associated crystal defects provides the explanation of the fundamental defect mechanisms observed in the experiment. To investigate the topology-dependent deformation behavior of npg at the atomic scale, analogous simulations are performed on a geometrically constructed (GeCo) npg sample (gyroid structure) with an average L and \(\varphi\) close to the ExIn sample. The configurations of undeformed and deformed (at 0.27 strain) simulated npg samples and the corresponding engineering stress-strain response (engineering stress, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{eng}}}}}\), as defined in Eq. 7) are shown in Fig. 3a-c. The GeCo sample shows roughly two times higher Young’s modulus (fitted in the elastic regime of engineering stress-strain curves, \({E}_{{{{\rm{eng}}}}}^{{{{\rm{GeCo}}}}}\) = 14.0 GPa) and engineering compressive strength (defined as \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{eng}}}}}\) at the global yield point, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{eng}}}}}^{{{{\rm{GeCo}}}}}\) = 153 MPa) than the ExIn sample (\({E}_{{{{\rm{eng}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ExIn}}}}}\) = 7.6 GPa, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{eng}}}}}^{{{{\rm{ExIn}}}}}\) = 72 MPa). The effective Young’s modulus of the ExIn sample unloaded at 0.16 strain calculated from the unloading curve amounts to 9.2 GPa, which is 4.2 times higher than the value of the experimental small-scale sample (\({E}^{{{{\rm{unload}}}}}\) = 2.2 GPa). The deviation in experimentally measured modulus from the simulation value arises primarily from differences in sampled volume, due to computational constraints affecting structural representativeness, and from the lack of rigid substrate support in experiments, which introduces additional compliance not accounted for in simulations. Both the simulated ExIn and experimental small-scale samples show strain hardening behavior during the compression, as evidenced by the steady increase in sessile dislocation density resulting from dislocation interactions (see SI, Fig. 13). The simulated ExIn sample shows densification behavior after 0.20 strain as indicated by the reduction of surface area (SI, Fig. 13), and neighboring ligaments are in contact at a strain of 0.27 as shown in Fig. 3a. However, no densification is observed in the simulated GeCo sample at the same strain level. The mechanical responses of atomic samples agree well with previous FE simulations on realistic npg structures obtained from FIB tomography and the GeCo gyroid structure where npg shows topology-dependent mechanical properties43. The topology and surface morphology of simulated samples are characterized via average local thickness, nodal connectivity, scaled genus density and ISD, see SI Figs. 6–8. The ExIn and GeCo samples show distinct topologies and surface morphologies. Interestingly, the ExIn sample shows a similar flow behavior compared to the in situ mechanical testing on the small-scale sample. In particular, the strain at yielding and the flow stress are comparable in the experiment and the simulation.

a real-size (L = 30 nm) experimentally informed npg sample (ExIn) derived from 360°-ET and (b) geometrically constructed npg sample (GeCo) with gyroid structure, before and after (at 0.27 strain) compression. c Engineering stress-strain curves of in situ compression tests on npg (L = 30 nm) and MD simulations on ExIn and GeCo samples (L = 30 nm). d True stress (square dot) and percentage of HCP atoms (line) as function of strain of MD simulations on ExIn and GeCo samples (L = 30 nm). Dashed lines indicate the initiation of plasticity.

True stress (\({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{zz}}}}}\), as defined in Equation 8) measures the average internal material interaction without the sudden jump of stress in \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{eng}}}}}\) caused the virtual indenters to partially lose contact with the ligaments. The evolution of \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{zz}}}}}\) and percentage of HCP (hexagonally closed packed) atoms of simulated npg samples during the simulated compression tests are studied (Fig. 3d). The rise of HCP atoms correlates with the initiation of plasticity since atoms within an HCP environment are considered to represent planar faults of the FCC (face centered cubic) lattice, e.g. stacking faults and twin boundaries, which occur when partial dislocations are present. Similar to the experimental observations (see SI, Fig. 10), the ExIn sample exhibits an early yielding before it reaches the true compressive strength (\({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{zz}}}}}\) = 190 MPa, defined as the true stress at the global yield point) due to the localized stress concentration originating from the realistic network connectivity and inhomogeneous distribution of ligament size (see SI Fig. 6 and SI Fig. 7). In contrast, the GeCo sample reaches the true compressive strength \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{zz}}}}}\) = 423 MPa right after the initiation of plasticity since the stress state and activation criteria of nucleation sites in each unit cell of a periodic gyroid structure are identical (SI, Fig. 14). Furthermore, the first stress drop of the ExIn sample is less abrupt than the one for the GeCo sample, see Fig. 3c, d. The stress is released by the nucleation and propagation of dislocations. The higher rate of the increase of HCP atoms in the GeCo sample indicates that more dislocations are simultaneously activated after the initiation of plasticity. An abrupt transition in the increase of HCP atoms is observed in the GeCo sample after the pronounced stress drop. The mechanical properties of the simulated npg samples are summarized in Table S2 in the Supplementary information.

The size-dependent deformation behavior of npg below L = 30 nm is investigated by comparison of MD compression tests on real-size (L = 30 nm) and scaled-down (L = 5, 7.5 and 10 nm) samples (Fig. 4). The true stress-strain response of atomistic simulated npg with different ligament sizes is shown in Fig. 4a and SI, Fig. 15a. The stresses at first plastic event (\({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{zz}}}}}^{* }\), defined as the true stress at the onset of plasticity) of simulated npg samples with different ligament sizes are normalized by the values of samples with L = 30 nm, see Fig. 4b. In both simulated npg samples, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{zz}}}}}^{* }\) decreases with decreasing ligament size. A similar trend is observed with the deformation of gold nanowires with their axis along the [137] crystallographic orientation, identical to the compression axis of the npg samples, see Fig. 4b. This abnormal “smaller is weaker” trend can be explained by the effect of surface-induced stress on surface dislocation nucleation51. SI, Fig. 15c shows the resolved shear stress state along the Burgers vector \(A\beta\) on the slip plane (b) in a representative junction in the GeCo samples with different ligament sizes before compression. The partial dislocation \(A\beta\) is first activated in the further compression tests, therefore the stress state before mechanical loading reflects the effect of surface-induced stress on the dislocation activation. The stress level is significantly higher in the smaller samples, since the effect of surface-induced stress is more pronounced in the samples with a higher surface-to-volume ratio37,38. Surface-induced stress assists surface dislocation nucleation by reducing the applied stress needed to overcome the activation barrier for nucleation. After yielding, a stress drop is only observed in the real-size samples (see Fig. 4a and SI, Fig. 15a). This is caused by the nucleation of many dislocations and can be explained by the much larger number of surface dislocation nucleation sites than are present in the scaled-down samples.

a True stress and (c) normalized dislocation density (normalized by mean ligament size) as function of strain of ExIn samples with different ligament sizes. b Normalized yield strength (normalized by the stress at first plastic event of samples with L = 30 nm) as function of ligament size in ExIn and GeCo samples and [137]-oriented gold nanowires (NW) under compression. d Schematic of geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) in ligaments for different characteristic lengths with the same strain gradient.

In the simulations as well as in the corresponding experiment the strain rate \(\dot{\gamma }\) is constant. For the present case where dislocations are nucleated and then move successively very quickly over a distance \(\lambda\) before being annihilated at the surface or immobilized, the Orowan equation can be written as52:

with \(\rho\) being the dislocation density. To understand the size-dependence of the true flow stress (see Fig. 4a and SI, Fig. 15a) \(\rho\) can be determined from the simulations, see Fig. 4d and SI, Fig. 15b. There, \(\rho\) is normalized by multiplying it with the mean ligament size \(L\). The rationale is that in order to maintain the same plastic strain gradient, the number of geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) NGND, needs to scale in proportion to \(L\), see Fig. 4d. From Fig. 4c one can see that the large-scale sample has more dislocations than would be required to maintain the same strain gradient than in the smaller samples. Given a constant \(\dot{\gamma }\) and \(L\), the (initially) larger \(\dot{\rho }\) for the large-scale sample compared to the small-scale samples, it immediately follows from Eq. 1 that \({\lambda }_{{large}}/{L}_{{large}} < \,\,{\lambda }_{{small}}/{L}_{{small}}\), with the later term probably being \(\approx 1\), i.e., in the large-scale sample the dislocations glide not so far compared to the ligament size than in the small-scale samples, where many can just escape via the surface. Only after longer deformation and at larger strains, also in the small-scale samples the dislocations accumulate inside the ligaments at the same rate as in the large-scale sample. Assuming similar deformation and strain gradients independent of size, the additional dislocation density in the large-scale sample is not geometrically necessary but rather statistically stored, and as such can contribute to the deformation, requiring less stress for the same strain increment than the small-scale sample with fewer dislocations. Our observations show that in the real-size npg (L = 30 nm), dislocation-dislocation interactions are common (SI, Fig. 16). In the simulated npg with ligament sizes ranging from 5 nm to 10 nm, plasticity is governed by the dislocation nucleation, where dislocations can easily nucleate and annihilate at the free surfaces without interacting and forming immobile dislocations. Their flow stress is therefore mostly dominated by the nucleation stress to generate dislocations at the surface.

The deformation behavior of npg on larger length scale (\(L\) = 300 nm) is studied via experimentally informed FE simulations using the meshed reconstruction from nano X-ray computed tomography (nano-CT) (see Fig. 2a). The FE simulations with the von Mises model are parameterized with small-scale data from compression experiments on gold nanopillars with a comparable characteristic length (\(L\) = 400 nm)53 and bulk gold data54. The stress-strain response obtained from the FE simulation using small-scale data fits well to the in situ compression experiment on the correlative npg (\(L\) = 300 nm), see Fig. 5b and Table S1 and S2. In contrast, the stress level of the FE simulation using bulk-scale data deviates far from the experiment. Regarding the elastic properties, the sponge’s Young’s modulus from experiments and simulations are in very good agreement, as shown in Table S1 and S2 in the Supplementary information. Since the macroscopic modulus in the related crystal orientation is used in the modelling, no anomalous low compliance of npg is reported here. Furthermore, the modelling results highlight the good representation of the network geometry by nano-CT and demonstrate the size effect in mechanical strength independent of the Gibson and Ashby scaling law. As reported by the MD simulations on the small-scale npg (\(L\) = 30 nm) in Fig. 3d, early yielding is also observed in the FE simulations on the large-scale npg (\(L\) = 300 nm). Here, the simulated nodes reach the plastic limit at the early stage of the deformation process before global yielding (c.f. Fig. 5a, b). Although the applied von Mises model is a macro-scale material model, by parameterizing with small-scale data it represents well the elastic and plastic behavior of the complex nanosponge structure.

a Engineering stress-strain curves of in situ compression tests on the large-scale npg sample (\(L\)=300 nm) and correlative FE simulations using small-scale (black dot) and bulk-scale (blue dot) input data. Percentage of plastically deformed nodes (PEEQ > 0.015) as function of strain during the compression test. b Evolution of plastically deformed nodes (equivalent plastic strain PEEQ > 0.015) during the simulated compression test. Surface mesh is half-transparent and the plastically deformed nodes are colored red.

3D analysis after deformation & size-dependent deformation mechanisms

After deformation, the small- and large-scale samples are studied again by means of non-destructive tomography (Supplementary Movies 10–11, Supplementary Movies 3–4) to identify 3D regions of interest (ROIs) at which plasticity localizes. From such a region, a FIB-lift out sample is prepared in <110> orientation (in lamella normal determined by correlative SAED analysis) and investigated by TEM to analyze the corresponding crystal defects. Figure 6 summarizes the results on the small-scale sample analyzed by means of 360°-ET and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM). Figure 6a shows the high-quality 3D reconstructions (without missing-wedge artefacts) of the undeformed and deformed network in the same outer view and in the middle section of the FIB lift-out. The defects are analyzed at the regions where the strain is localized in single ligaments and ligament junctions (Fig. 6b) and are identified as dominantly micro-twins, stacking fault tetrahedra (SFTs) and small-angle grain boundaries (SAGB). As an example, one ligament is shown in Fig. 6 (marked by black arrow), which is located at the outer rim of the pillar, initially parallel to the loading direction (<137>) and exhibiting a size of ~30 nm. Upon compression, this specific ligament is dominantly deformed by bending/buckling in its middle section, which is enabled on the atomic scale by GNDs forming a SAGB. SAGBs are also observed in larger ligaments enabling the geometric adaption of the network structure (by lattice rotations of up to ~10°). In specific cases, also extended SAGB networks are observed in between neighboring larger ligaments (SI, Fig. 17). Contrarily, no SAGBs but stacking faults/micro-twins are observed in smaller ligaments (SI, Fig. 18). Specifically, a higher dislocation density is often present at ligament junctions, with full and partial dislocations, dislocation locks or complex fault structures, e.g. SFTs (Fig. 6, SI, Fig. 18). This effect can be attributed to local stress concentrations at ligament junctions (as shown in Fig. 6b) causing dislocation nucleation, but may also result from statistical storage of dislocations, whereby dislocations from different ligaments meet and interact with each other. In many cases, micro-twins are identified accompanying plastic deformation, while only a few are identified in the undeformed material (SI, Fig. 19). In general, more defects and structural disorder evolve with increasing local strain leading to the steady formation of new sub-grains and a polycrystalline nature within npg (SI, Fig. 19). As mentioned before, weak spots can easily trigger local plastic deformation. Npg exhibits locally intrinsic flaws, which can be caused by inhomogeneous dealloying along grain boundaries or inside of grains. These defects can trigger strain localization but are often not directly visible by a pure 2D analysis. SI, Fig. 20 and Supplementary Movie 12 illustrate this case and emphasize the importance of 3D analysis for understanding the local deformation in npg.

a 3D reconstructions derived from 360°-ET before and after deformation in surface-rendered view showing the cross-section from which a TEM lamella is prepared. b Magnified image of dotted ROI marked in (a) revealing ‘hot spots’ of local deformation and related crystal defects as identified by TEM analysis: Micro-twins, SFTs and SAGBs (here the related Burgers circuits are shown revealing full a/2 < 110 > - type dislocations).

Since the ExIn simulations are performed on the geometric network structure derived from the experiment, the topology-dependent deformation behavior of npg can be analyzed in a correlative manner by comparison of defect distributions in an identical ROI from experiment and simulation. As shown in the TEM image of the deformed small-scale sample in Fig. 7a, defects are mainly localized near the junctions of the network structures. The defect distribution of the deformed ExIn sample (\(L\) = 30 nm) from MD simulations in Fig. 7b correlates well with the identical area as observed by TEM. Furthermore, the characteristic defects in the deformed small-scale sample, e.g. micro-twins, SAGBs and SFTs, are also widely observed in the simulated npg sample (\(L\) = 30 nm) after unloading from 0.16 strain.

a TEM image of deformed small-scale sample (L = 30 nm) showing defect distribution. b Defect distribution of the corresponding area as shown in a of deformed ExIn sample (L = 30 nm) from MD simulations. Here only defect atoms are highlighted and atoms which belong to the free surface are shown in half-transparent. c Defects in deformed ExIn sample (L = 30 nm) from MD simulations. Only dislocation lines, surface mesh and atoms belonging to defect structures are shown here. Characteristic defects in deformed ExIn sample (L = 30 nm): (d) SAGB, (e) SFT and cross-slip and (f) Micro-twin.

The formation of SFT and SAGB shows a strong size dependency in MD simulations within the studied size range (\(L\) = 5−30 nm). SFT and SAGB are characteristic defects in the deformed real-size npg samples (\(L\) = 30 nm), but very few of those defects are observed in the deformed scaled-down samples (\(L\) < 10 nm), see SI, Fig. 16. SI, Fig. 21 and 22 show the mechanism of formation of deformation-induced SFT and SAGB in the ExIn sample (\(L\) = 30 nm) during the compression test. A complex local stress state (see SI, Fig. 23) combined with interaction and cross-slip of full dislocations is necessary for the formation of SFT. This is different to the mechanism of vacancy-induced SFT reported in a previous study of npg36. The formation of SAGB is due to the interaction between an array of full dislocations and partial dislocations, which leads to the formation of extended dislocation nodes. A more detailed description of the formation of SFT and SAGB can be found in the SI. A simple line-tension-based model with the incorporation of the crystallographic orientation dependency by including the Schmid factors for the full and leading partial dislocations55 estimates the critical size \({D}_{c}\) for nucleation of full dislocation and partial dislocation:

where \(\alpha = \;\)0.5 and \(\alpha = \;\)1.5 for edge and screw dislocations, respectively. \(\mu\) is the shear modulus, and \(\gamma\) is the stacking fault energy. \({b}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}\) and \({b}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) are the magnitudes of Burgers vectors of the full and the partial dislocations, respectively. \({M}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}\) and \({M}_{{{{\rm{lp}}}}}\) are the largest Schmid factors of the full and the leading partial dislocations. Here, taking \(\alpha = \;\)1, \({M}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}= \;\)0.498 (for the \({AD}(b)\) slip system, see Table S3), \({M}_{{{{\rm{lp}}}}}= \;\)0.431 (for the \(A\beta (b)\) or \(D\beta (b)\) slip system), and other parameters calculated using the used interatomic potential, \({D}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) is around 24 nm. The resolved shear stresses of leading partial dislocations in the simulated npg samples showed anisotropic plasticity that correlated well with the Schmid factors (see SI, Fig. 24), which agree well with a previous crystal plasticity study on single-crystalline stochastic honeycombs56. Therefore, the crystallographic orientation of the single-crystalline npg was taken into account in the estimation. The critical size \({D}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) with this orientation information is 24 nm which is about 2/3 of the one without considering the orientation dependency (i.e., when \(\frac{{M}_{{{{\rm{lp}}}}}}{{M}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}}\) = 1, \({D}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\approx\) 35 nm). The mean ligament size of the real-size simulated samples is around 30 nm, which is higher than the estimated \({D}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\). Therefore, the nucleation of full dislocations is expected to occur mainly in the real-size sample and less in the scaled-down samples. For the simulated real-size ExIn sample (\(L\) = 30 nm) with a normalized dislocation density \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{dislocation}}}}}\cdot L\) = 0.062 nm-1 after global yielding (3.3% strain), 132 (~42%) full dislocations were detected out of 315 dislocations. For the corresponding scaled-down ExIn sample (\(L\)= 10 nm) at a similar level of normalized dislocation density (~0.082 nm-1), only 46 (~29%) full dislocations were found out of 161 dislocations. Except for the size-dependent preference of dislocation nucleation, dislocations in the smaller samples have a greater probability of escaping at the free surfaces than of interacting with one another as shown in the evolution of normalized dislocation density in Fig. 4c. The size-dependent dislocation nucleation and interaction explain the formations of SFT and SAGB observed in the real-size npg samples.

The observed agreement in flow stress between MD simulations and experiments on the npg samples (\(L\) = 30 nm), despite the orders-of-magnitude difference in strain rates, requires consideration beyond surface dislocation nucleation. Structural heterogeneity and surface conditions must be taken into account. The activation volume associated with surface dislocation nucleation typically falls within the range of 1–10b3, leading to a strong dependence of nucleation stress on both strain rate and temperature57,58. In npg, structural heterogeneity and variations in surface conditions give rise to a broad distribution of nucleation stresses, contributing to the pronounced stochastic nature of surface dislocation nucleation similar to thermal activation processes. This heterogeneity can mitigate strain rate effects by enabling localized plasticity initiation at lower applied stresses. Experimental investigations on nanoporous gold (L = 55 nm) using strain rate jump compression tests (strain rate ranging from 10-5 to 10-3/s) have demonstrated exceptionally low strain rate sensitivity in the early stages of plastic deformation (below 0.2 strain), where dislocation nucleation governs plasticity13. A similar conclusion was drawn from in situ TEM tensile experiments on Pd nanowires (30 to 100 nm diameters), which exhibited weak strain rate dependence over a comparable experimental strain rate range (10-5 to 10-3/s) but a pronounced sensitivity to temperature59. Furthermore, MD simulations of nanoporous gold (L = 6.4 nm) at 300 K, performed over strain rates ranging from 106 to 109/s, demonstrated that strain rate effects on flow stress were minor below ~108/s60. These findings suggest that the apparent consistency in flow stress between MD simulations and experiments may arise from compensating effects between strain rate sensitivity and local stress heterogeneities. Additionally, differences in experimental and simulation conditions, such as the presence of Ag solutes and pre-existing defects in experimental samples, as well as the limited system size in simulations, must be taken into account.

Figure 8 shows the 3D analysis of the large-scale sample after deformation and the deformation microstructure. For local 3D strain analysis, the 3D reconstructions of the undeformed and deformed network obtained by high-resolution nano-CT (without missing-wedge artefacts) are correlated. Figure 8a shows the reconstructions in the same external view and middle section. The high-quality 3D data of the network structure before and after deformation allows the calculation of the local displacement field in 3D evolving upon compression by methods of digital volume correlation (DVC), shown in Fig. 8d. This method gives the unique possibility to compare the experimentally derived displacement field (Fig. 8d) with the one observed in the experimentally informed FE simulation (Fig. 8e), performed on the same structure. A qualitatively good agreement between both displacement fields and therefore both methods is found, which corroborates the parameterization using the small-scale data used in the FE simulation. For the analysis of crystal defects, a TEM lamella is prepared along a <100> orientation by performing a FIB lift-out from the central region of the deformed large-scale sample, but slightly angled with respect to the pillar axis. The targeted crystal orientation with respect to the npg network is identified by correlative EBSD and 3D analyses of the reconstruction (in the deformed state). Figure 8b shows the as-prepared lamella in the TEM and reveals a bulk-like deformation microstructure in locally yield regions, with extended networks of full dislocations and dislocation walls. This observation is in strong contrast to the observed defects in the small-scale study but is consistent with the change in deformation mechanisms predicted by above line-tension-based model, i.e. the occurrence of full dislocations at larger length scale and partial dislocations at smaller length scale. By analyzing the equivalent plastic strain (PEEQ) in the corresponding experimentally informed FE simulation (Fig. 8c) ‘hot spots’ are identified, i.e., ROIs at which strain localizes. The strain localization often occurs at ligament junctions, which act as plastic hinges that experience high bending moments. By correlating both, TEM defect and FE strain analysis, a good agreement between the local occurrence of high dislocation densities and plastic strain concentrations is observed.

a 3D reconstructions (surface rendering) derived from nano-CT before and after deformation in the same external view and cross-sectional slice through the center. b Left: TEM overview image of the lamella prepared from the central cross-sectional area but 28° inclined with respect to the pillar axis (as indicated by the dashed line on the 3D reconstructions in (c−e)). The colored rectangles in (b) indicate exemplary ROIs at which a high local dislocations density is observed. b Right: Magnified TEM images revealing bulk-type deformation behavior with dislocation networks (green ROI) and dislocation walls (orange ROI) (c) Analysis of the equivalent plastic strain (PEEQ) in the experimentally informed FE simulation. c Left: The PEEQ is plotted on the 3D reconstruction (deformed state). Right: For comparison with the defect arrangement the same slice as the lamella in (b) is extracted from the 3D reconstruction (as indicated by the dashed line) and the corresponding ROIs from (b) are marked revealing ‘hot spots’ of plastic strain concentration. d, e Analysis of the local displacement field, derived (d) experimentally from DVC (cf. experimental description in the SI) and e from the experimentally informed FE simulation. In both cases, the displacement field is plotted on the 3D reconstruction (undeformed state), shown on the left side, respectively. On the right side the extracted slices from the 3D reconstruction, corresponding to the TEM lamella in (b) are shown.

By the comprehensive linkage of correlated microscopy techniques and simulation methods, a scale-bridging deformation mechanism landscape is derived (SI, Fig. 25), showcasing size effects on dislocation nucleation and interaction in complex nanosponges, as exemplarily shown for npg. In the smallest size regime with a characteristic ligament size of around ten nanometers, corresponding to the scaled-down samples studied by MD simulations in the present work and typical for most atomistic studies23,35,37,41, the influence of surface-induced stress on surface dislocation nucleation is very pronounced. The surface-induced stress can either assist or hinder the surface dislocation nucleation depending on the relative orientation between applied strain and crystallography51. The nucleation of partial dislocations is strongly preferred at this length scale, as well as the formation of deformation twins results from continuous nucleation of leading partial dislocations on adjacent slip planes55. Dislocations are unable to be stored in such small dimensions. Therefore, the effect of dislocation-interaction-related hardening mechanisms is limited. In the intermediate size regime with a characteristic length of a few tens of nanometers, represented by the small-scale experimental sample (L ~30 nm) in the present work and studied by in situ nanomechanics in TEM, 360°-ET, HRTEM and MD simulations, the nucleation of full dislocation is preferred. Furthermore, the ligament size is large enough for dislocation interactions to take place. Therefore, the dislocation density multiplied by L is higher at that scale than for smaller systems. Furthermore, the formation of SAGB, SFT and other defects resulting from the interactions of full dislocations are the expected mechanisms on this length scale. In the size regime of hundreds of nanometers, represented by the large-scale experimental sample (L ~300 nm) in the present work and studied by in situ micromechanics in SEM, nano-CT, (HR)TEM and FE simulations, the deformation is governed by dislocation-dislocation interactions and classical dislocation sources inside the ligaments. This leads to a bulk-type deformation behavior, which can be successfully modeled by von Mises type isotropic plasticity model. The size dependence of the yield and flow stress needs, however, to be taken into account. The underlying reason for this size dependence is most probably the truncation of dislocation sources42.

Conclusions

Within this study, a correlative workflow is successfully established which combines tomographic 3D analyses by 360°-ET and nano-CT, in situ mechanical testing in SEM and TEM, defect characterization by conventional/high-resolution TEM and experimentally informed cross-scale atomistic and FE simulations to unravel the microscopic deformation mechanisms that govern plastic deformation of metal nanosponges at different characteristic length scales demonstrated for npg. Non-destructive tomographic and correlative microscopy techniques are employed to analyze the real npg network structures concerning geometry, chemistry and crystallography before and after deformation. This allows for the analysis of localized and early plasticity occurring in npg, specifically the linkage between local strain concentration in single ligaments or junctions, and related crystal defects. The experimental observations, i.e., defect types and overall stress-strain response, coincide well with correlated experimentally informed simulations on the derived tomographic reconstructions, in contrast to geometrically constructed or scaled-down atomistic models and bulk-scale continuum material models. The unique combination of experimental and modelling techniques used in this study provides valuable and comprehensive insights into the real deformation mechanisms of npg and highlights the importance of realistic geometry and size on nanoscale plasticity. In addition, a deformation mechanism landscape is derived describing the effect of ligament size on plasticity from the surface stress dominated regime at very small sizes over the domain at which nucleation and annihilation of partial dislocations at surfaces controls plasticity to the predominance of full dislocation activity and the effect of statistically stored dislocations and finally the source truncation controlled regime, which can be described by including size dependence in bulk plasticity models. This study thus explores and validates the applicability of the correlative and scale-bridging experiments and simulations to reveal the atomistic mechanisms of fcc metal plasticity with geometrical complexity.

Methods

Npg synthesis

To produce npg, firstly, an initial master alloy with a nominal composition of 23 at.-% Au and 77 at.-% Ag was cast. The selected composition is well within the range of the parting limit61,62 (allowing for an homogeneous evolution of nanoporosity), while providing a high degree of porosity. To achieve the desired composition 0.86 g of Au and 1.21 g of Ag were flame melted under argon atmosphere and casted into a borax-lined crucible. After solidification, the nugget was cleaned in sulfuric acid. The nominal composition of the resulting solid solution was confirmed by SEM-EDXS to be 23 at.-% Au and 77 at.-% Ag. Secondly, metallographic techniques were applied to obtain suitable samples, which were free of preparational artefacts, for the dealloying procedure. Therefore, cuboids with dimensions of 1 × 1 × 0.5 mm were cut out from the Au-Ag master alloy with a wire saw and polished down to a roughness of 1 µm. The samples were annealed after mechanical preparation at 800 °C for 24 h under argon atmosphere in order to remove any residual polycrystalline damage-layer, which is typically present after mechanical preparation. Thirdly, the nanoporous structure with a mean ligament size L = 30 nm was created by dealloying the samples by free corrosion for 24 h in 40% nitric acid. Afterwards the samples were cleaned with distilled water and acetone to remove any residual acid from the pore space. To obtain an approximately ten times bigger ligament size (L ~300 nm) one sample batch was annealed for 0.3 h at 450 °C under air atmosphere. The entire synthesis routine is depicted in SI Fig. 1.

Site-specific sample preparation

To enable both non-destructive tomography and in situ mechanical testing on the same sample, a pillar was prepared in a site-specific manner on top of a tailored tip by advanced FIB preparation techniques using a DualBeam SEM-FIB FEI Helios NanoLab 660 instrument at CENEM. Therefore, a cuboid of several µm was lifted out from a single npg grain and transferred to the tip. From the cuboid, the pillar was prepared for the respective length scale using Ga+-ions at 30 kV acceleration voltage. Prior to the transfer, a plateau was prepared on top of the tip by FIB milling with a size matching the size of the cuboid.

Small-scale sample (L = 30 nm)

On the small scale, a pillar with a diameter of ~400 nm and a height of ~750 nm was prepared. The final milling was performed in a single pass using using Ga+-ions at 1 pA beam current at 30 kV acceleration voltage. Upon FIB preparation specific care was taken to avoid any direct exposure of the sample to the ion beam. This procedure helps to minimize FIB damage as much as possible. The detailed preparation procedure is depicted in SI Fig. 2. Since the tip was mounted onto both 360°-ET as well as an in situ mechanical testing holder in the TEM, some modifications to the standard sample mounts were required to fulfill the geometric requirement of both holders, respectively. Therefore, a conventional brass tomography tip (as available from E.A. Fischione Instruments, Inc.) with a standard diameter of 1 mm and a length of 1 cm was cut down to a length of 4 mm in advance of the FIB preparation. A standard bulk sample mount, as available for the Hysitron PI 95 TEM Picoindenter®, was adapted by milling a nut with a diameter of 1 mm into the mounting plate. A copper cylinder with an outer diameter of 2 mm and an inner hole of 1 mm was fabricated by electrical discharge machining (EDM). For the 3D investigation by means of 360°-ET, the tip was fixed into the inner hole of the metal cylinder by press fit, while for in situ mechanical testing the tip was inserted into the nut of the sample mount. In both cases, the sample was additionally fixed with a small amount of conductive Ag paste.

Large-scale sample (L = 300 nm)

On the large scale, a pillar with a diameter of ~4 µm and a height of ~4 µm (aspect ratio~1) was prepared on the pre-tailored plateau of a tungsten pin (diameter ~0.5 mm, length ~17 mm) suitable for nano-CT experiments. The milling was performed with Ga+-beam in a single pass using 0.23 nA beam current at 30 kV acceleration voltage. In the last milling step, the pillar height was adjusted by cutting the pillar in side view to the desired aspect ratio. In this way, a solid support ensuring mechanical stability during compression is granted (this approach could not be realized on the small-scale sample due to its small sample size). In this case, a pillar with a diameter of 3 µm and an aspect ratio of 1 was prepared. The complete preparation procedure is depicted in SI Fig. 3. The pillar diameter was chosen to be at most twice the attenuation length of npg (with a relative density of ~35%) for X-rays (nano-CT) at the applied X-ray energy (5.4 keV) to allow for sufficient absorption contrast (according to the Beer-Lambert law)63. The relative density of the sample was assumed at this time to be ~35% as determined from the reconstruction for the small-size pillar in the 360°-ET experiment. At the respective X-ray energy of 5.4 keV, the attenuation length yields 2.6 µm, as determined via Ref. 64.

Structural and mechanical analysis

SEM analyses, micropillar preparation, in situ mechanical testing on the large-scale sample and TEM lamella preparation was performed using the DualBeam SEM-FIB FEI Helios NanoLab 660 at CENEM. The instrument is equipped with an FEI easy lift micromanipulator for TEM lift-out preparations and a large-area EDXS detector (Oxford X-Max 150 mm²) for chemical analysis. For the in situ mechanical testing, the sample was mounted on a spring table (STFMA, Kleindiek Nanotechnik GmbH) and a flexible micromanipulator (MM3A, Kleindiek Nanotechnik GmbH) was used to compress the sample. Thereby, the manipulator was equipped with a diamond flat punch indenter at the front end and a 360° rotational axis controllable plug-in tool (ROTIP-EM, Kleindiek Nanotechnik GmbH), which facilitates the accurate alignment between flat punch and sample. The displacement was monitored via DIC techniques, while the corresponding force was calculated by the deflection of the spring table, knowing its spring constant.

TEM analyses, including in situ mechanical testing on the small-scale sample and 360°-ET, were performed using a double-corrected (probe and image side) FEI Titan³ Themis 60−300 (FEI Company, Netherlands) at CENEM operated at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV, equipped with a Super-X detector for chemical analysis. In situ micropillar compression testing was performed using a Hysitron PI 95 TEM Picoindenter® (Hysitron, Inc., USA), equipped with a diamond flat punch under displacement control (2 nm/s). 360°-ET was performed using a Fischione Model 2050 On-Axis Rotation Tomography holder (E.A. Fischione Instruments, Inc.). 360°-ET was performed in micro-probe STEM mode while lowering the semi-convergence angle to 1.7 mrad. The low convergence angle allows an increased depth of field (DOF) of about 510 nm, which is high enough to image the complete pillar sample (diameter ~400 nm) in focus throughout the entire tilt series acquisition procedure. The resulting diffraction-limited resolution at the respective convergence angle yields about 0.71 nm. The camera length was decreased to 46 mm in order to obtain dominant mass-thickness contrast conditions and minimize non-linear contrast contributions (resulting from Bragg diffraction). The tilt series was acquired with FEI Tomography 4.0 software in a tilt-angle range of 180° applying 1° tilt increments, continuous and linear tilting scheme and auto focus and tracking before acquisition. The alignment of the tilt series was performed using the FEI Inspect 3D software via cross-correlation technique for the undeformed sample, while a feature tracking based algorithm was applied in case of the deformed sample. To reconstruct the tilt series, the single iterative reconstruction technique (SIRT)65 algorithm with 50 iterations was applied by using the FEI Inspect 3D software. The reconstructions were corrected for the cupping artefact, which occurs in HAADF-STEM mode by the thickness-dependent, non-linear damping of projected intensities66. The correction was done by taking into account the zero intensity of the STEM signal, as described by Van den Broek et al.66. The corrected reconstructions were visualized and segmented (into pore space and solid material) by applying a global threshold using VSG Avizo 8.1.

Nano-CT analysis was performed using a Zeiss Xradia Ultra 810 nano computed tomography (CT) instrument, equipped with a Cr X-ray source, which offers X-ray energies of 5.4 keV. All tomographic measurements were performed in high-resolution mode (with optical resolution of ~(50 nm)³) within a field-of-view of (16 µm * 16 µm) and absorption contrast mode. The tilt series were acquired using the Zeiss ‘Scout and Scan’ user interface and applying a full tilt-angle range of 180° with a tilt increment of 0.5° (resulting in 361 projections), a dwell time of 90 s and a camera binning of 2. In summary, this results in a voxel size of 32 nm. A reference scan was performed before and after the actual tomographic series to reduce background noise. To minimize thermal drift effects a warm up scan (0.5 – 4 h) was also performed before the measurement and an automatic motion correction (AMC) was applied afterwards. The nano-CT tilt series were reconstructed by applying the filtered back projection (FBP) algorithm, which was implemented in the Zeiss ‘Reconstructor’ software. Tilt-axis alignment was performed by minimizing reconstruction artefacts in ‘fast-calculated’ reconstructions. The visualization and segmentation of the final reconstructions was performed in VSG Avizo 8 by applying a global threshold.

DIC/DVC techniques

DIC analysis was performed on images taken during in situ SEM compression series by using Bézier surface fitting techniques67. DVC was applied to analyze the 3D local displacement field in the large-scale sample by correlating the compressed and uncompressed reconstruction using Vic-3D (Correlated Solutions, Inc.). DVC analysis was performed on the reconstruction of the large-scale sample. In the calculation, a step size of about three times the pixel size of 32 nm and a filter size of seven was applied in order to remove artefacts from the reconstruction and reduce noise. In this way, the sampling rate of the analysis (step size * voxel size) yields ~100 nm.

Scaling laws

For calculation of ligament yield strength and elastic modulus and in particular for comparison with related literature data, the foam scaling laws from Gibson and Ashby19 which describe the mechanical behavior of open porous cellular materials with respect to their bulk counterparts were used. The Young’s modulus, \(E\), as well as the yield strength, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}}}\), of an open-cell foam can be calculated via Eq. 4 and Eq. 5 by taking into account the relative density, \(\varphi\), derived from the material density of the foam, \(\rho\), and the solid, \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) (Eq. 3)19.

Here, \({E}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}},{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) represent the Young’s modulus and the yield strength of the solid, respectively. \({C}_{E}\) and \({C}_{\sigma }\) are non-dimensional pre-factors, which describe the geometry of the foam. Specifically, they are a function of the shape, anisotropy, size distribution of the cells and the ligament morphology. These non-dimensional pre-factors can be within a range of \({C}_{E}=0.1-4.0\) and \({C}_{\sigma }=0.1-1.0\) 68. Typical values for a wide range of foams with a low density are \({C}_{E}=1.0\) and \({C}_{\sigma }=0.3\) 1.

Setup of atomistic simulations

MD simulations were performed on the experimentally informed npg volume (in the following denoted as ExIn) and a geometrically constructed model (denoted as GeCo). The experimentally informed sample was prepared by cropping out ~21% of the actual pillar volume from the extracted surface of the 360°-ET reconstruction in the middle of the pillar. NanoSCULPT69 was used to reconstruct the atomistic structure of the experimentally informed sample, which exhibits a pillar diameter of ~425 nm, a ligament diameter of ~30 nm, a relative density of ~35.5% and a crystal orientation of [137] along the pillar axis. The geometrically constructed model (representing a gyroid structure with similar feature sizes and an identical relative density) was constructed by using the constant-mean-curvature surface analytical formula70:

where X, Y and Z are atomic coordinates normalized by a unit length. φ is the relative density of the structure. The structures contain roughly 470 Mio atoms and feature the identical crystallographic orientation as the npg pillar in the experiment (pillar axis along [137] crystal orientation).

The atomic interaction was modeled by the embedded atom model (EAM) potential for Au71. Static and dynamic simulations were carried out with the MD software packages IMD72 and LAMMPS73, respectively. After the relaxation (using the FIRE algorithm74,75), the samples were brought in equilibrium at 300 K within the NVE and NVT (Nosé–Hoover thermostat76) thermodynamic ensemble. Compression tests were performed at 300 K (Nosé–Hoover thermostat) under a constant strain rate of 1 × 108 s-1 with a time step of 1 fs. The samples were compressed by a virtual indenter, which applied a force according to a harmonic spring potential with a spring constant of 1 eV/Å2 on all atoms within a cutoff of 0.25 nm. The direction of the force was parallel to the axis of compression. The engineering stress was calculated as:

where \(F\) is the force of the virtual indenter and \({A}_{0}\) is the initial cross-sectional area of the pillar. During the simulations, on-the-fly structural analyses and calculation of auxiliary properties (coordination number, common neighbor analysis, virial stress tensor, etc.) were carried out. After the simulations, further post-processing analyses, which include dislocation extraction algorithm (DXA)77 and resolved shear stress calculation were carried out. The virial stress tensor was calculated for each atom by considering the volume of the corresponding Voronoi cell. The true stress along the uniaxial compression direction was determined:

where \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{zz}}}}}^{i}\) and \({V}^{i}\) are the zz component of virial stress and the atomic volume of atom \(i\), respectively. For visualization, the virial stress tensor was homogenized by averaging each component over the local neighborhood. The Thompson tetrahedron notation78 was invoked to describe the dislocation interactions. Visualization of the simulation snapshots were performed by using the atomistic visualization software OVITO79.

Setup of FE simulations

FEM simulations were performed on the large-scale sample geometry derived from nano-CT with a pillar diameter of ~4 µm, a ligament diameter of ~300 nm and a relative density of ~40 %. To obtain a suitable mesh for the FEM simulations, firstly a surface mesh was generated from the respective 3D reconstruction via Avizo. The surface mesh was transformed into a volumetric mesh (consisting of 800 000 tetrahedra and 400 000 voxels) by using Hypermesh. Uniaxial compression testing was simulated on the derived volumetric mesh by mimicking two rigid plates using Abaqus FEA. A general contact algorithm was applied to model the contact between the plates and npg, and also between the ligaments among each other. A standard Von Mises model was assumed to simulate plasticity. To evaluate size effects, a flow curve obtained by Greer et al.53 from compression experiments on single crystalline Au nanopillars (with a diameter of 400 nm and <100> orientation along the loading axis) was used as input data for plastic model. The curve was parameterized and the true plastic strain was extracted by fitting the unloading slope (52.2 GPa) to each data point. It should be noted here that the yield stress for this data shows a size effect and is much higher ( ~ 400-600 MPa) compared to the typical yield strength of bulk Au (estimated as 30 MPa at 0.2 % strain54). The data from Greer et al.53 was chosen since the pillar diameter is close to the mean ligament diameter of npg, and the crystal orientation in the experiment is close to a <100> orientation (real orientation in experiment <013>, 16° off from <100> axis). Volkert et al.18 discussed the equivalence between the pillar diameter and the ligament diameter by referring to them as one characteristic dimension causing the same size effect, and thus determining yield strength in npg. The engineering stress was calculated from the force of the contact plates and the initial cross-sectional area of the pillar similar to Eq. 7.

Topological and morphological analyses

Topology

The local topology properties, like local thickness and nodal connectivity were obtained from the skeletonization of the bicontinuous structures using Auto Skeleton module implemented in Amira. The algorithm extracts the centerline of the porous structures from 3D image data and then converts to a spatial graph consisting of nodes and segments. The nodes are the branching points and endpoints, and the segments are the curved lines connecting these nodes. The local thickness was determined by measuring the closest distance from a given point of the segments to the surface boundary. The nodal connectivity was obtained by calculating the number of segments connected at a node.

The local thickness and nodal connectivity are both local topological parameters. In order to quantitatively measure the global connectivity, the scaled genus density (\(\bar{g}\)) 43 was used:

where \(g\) is the genus which describes the number of continuous loops in the connected structure, \(V\) is the foam volume and \({S}_{{{{\rm{vf}}}}}^{-3}\) is the characteristic volume in which \({S}_{{{{\rm{vf}}}}}\) is the surface area per unit foam volume. The genus was calculated from the Euler characteristic (\(\chi\)) of the triangulated surface mesh80:

where \({N}_{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\), \({N}_{{{{\rm{E}}}}}\) and \({N}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) are the number of vertices, edges and faces of the surface mesh, respectively.

Morphology

Interfacial shape distribution (ISD) is a morphological parameter which gives the probability of finding a patch of interface with a given pair of minimum (\({\kappa }_{1}\)) and maximum (\({\kappa }_{2}\)) principal curvatures. The principal curvatures were calculated at each node of the triangulated surface mesh. The principal curvatures were normalized by the inverse characteristic length \({S}_{{{{\rm{v}}}}}\) which is the surface area per unit solid volume, which enable to directly compare the morphologies of bicontinuous structures in different length scales. The relations between principal curvatures and representative geometrical patches are reported in Table 1.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw image files that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Raw data and additional source data can be accessed on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15837560).

References

Mameka, N., Wang, K., Markmann, J., Lilleodden, E. T. & Weissmüller, J. Nanoporous gold—testing macro-scale samples to probe small-scale mechanical behavior. Mater. Res. Lett. 4, 27–36 (2016).

Lilleodden, E. T. & Voorhees, P. W. On the topological, morphological, and microstructural characterization of nanoporous metals. MRS Bull. 43, 20–26 (2018).

Shi, S., Li, Y., Ngo-Dinh, B.-N., Markmann, J. & Weissmüller, J. Scaling behavior of stiffness and strength of hierarchical network nanomaterials. Science 371, 1026–1033 (2021).

Kramer, D., Viswanath, R. N. & Weissmüller, J. Surface-stress induced macroscopic bending of nanoporous gold cantilevers. Nano Lett. 4, 793–796 (2004).

Biener, J. et al. Surface-chemistry-driven actuation in nanoporous gold. Nat. Mater. 8, 47 (2008).

Ding, Y., Chen, M. & Erlebacher, J. Metallic mesoporous nanocomposites for electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6876–6877 (2004).

Wittstock, A. et al. Nanoporous Au: an unsupported pure gold catalyst? J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 5593–5600 (2009).

Lang, X. Y., Chen, L. Y., Guan, P. F., Fujita, T. & Chen, M. W. Geometric effect on surface enhanced Raman scattering of nanoporous gold: improving Raman scattering by tailoring ligament and nanopore ratios. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 213109 (2009).

Hu, K., Lan, D., Li, X. & Zhang, S. Nanoporous gold—testing macro-scelectrochemical DNA biosensor based on nanoporous gold electrode and multifunctional encoded DNA−Au bio bar codesale samples to probe small-scale mechanical behavior. Anal. Chem. 80, 9124–9130 (2008).

Mathur, A. & Erlebacher, J. Size dependence of effective Young’s modulus of nanoporous gold. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 2005–2008 (2007).

Briot, N. J., Kennerknecht, T., Eberl, C. & Balk, T. J. Mechanical properties of bulk single crystalline nanoporous gold investigated by millimetre-scale tension and compression testing. Philos. Mag. 94, 847–866 (2014).

Biener, J. et al. Size effects on the mechanical behavior of nanoporous Au. Nano Lett 6, 5–8 (2006).

Jin, H. J. et al. Deforming nanoporous metal: Role of lattice coherency. Acta Mater 57, 2665–2672 (2009).

Chen-Wiegart, Y. C. K. et al. Structural evolution of nanoporous gold during thermal coarsening. Acta Mater 60, 4972–4981 (2012).

Wang, K. et al. Nanoporous-gold-based composites: toward tensile ductility. NPG Asia Mater 7, e187 (2015).

Bapari, S., Lührs, L. & Weissmüller, J. Metrics for the characteristic length scale in the random bicontinuous microstructure of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 260, 119333 (2023).

Seker, E., Reed, M. L. & Begley, M. R. Nanoporous gold: fabrication, characterization, and applications. Materials ((Basel)) 2, 2188–2215 (2009).

Volkert, C. A., Lilleodden, E. T., Kramer, D. & Weissmüller, J. Approaching the theoretical strength in nanoporous Au. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 10–13 (2006).

Gibson, L. J. & Ashby, M. F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties 2nd edn, Vol. 532 (Cambridge university press, 1999).

Hodge, A. M. et al. Scaling equation for yield strength of nanoporous open-cell foams. Acta Mater. 55, 1343–1349 (2007).

Huber, N. et al. Scaling laws of nanoporous metals under uniaxial compression. Acta Mater. 67, 252–265 (2014).

Roschning, B. & Huber, N. Scaling laws of nanoporous gold under uniaxial compression: effects of structural disorder on the solid fraction, elastic poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus and yield strength. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 92, 55–71 (2016).

Sun, X.-Y. Y., Xu, G.-K. K., Li, X., Feng, X.-Q. Q. & Gao, H. Mechanical properties and scaling laws of nanoporous gold. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 023505 (2013).

Saffarini, M. H., Voyiadjis, G. Z. & Ruestes, C. J. Scaling laws for nanoporous metals under uniaxial loading. J. Mater. Res. 36, 2729–2741 (2021).

Sohn, S., Richert, C., Shi, S., Weissmüller, J. & Huber, N. Scaling between elasticity and topological genus for random network nanomaterials. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 68, 102147 (2024).

Dou, R. & Derby, B. Deformation mechanisms in gold nanowires and nanoporous gold. Philos. Mag. 91, 1070–1083 (2011).

Liu, P. et al. Time-resolved atomic-scale observations of deformation and fracture of nanoporous gold under tension. Acta Mater. 165, 99–108 (2019).

Liu, M. & Weissmüller, J. Imaging the deformation-induced accumulation of defects in nanoporous gold. Mater. Res. Lett. 9, 359–365 (2021).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Mechanical properties of unidirectional nanoporous gold under compression. Acta Mater. 235, 118078 (2022).

Liu, L. Z., Zhang, Y. Y., Xie, H. & Jin, H. J. Transition from homogeneous to localized deformation in nanoporous gold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 95501 (2021).

Zandersons, B., Lührs, L., Li, Y. & Weissmüller, J. On factors defining the mechanical behavior of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 215, 116979 (2021).

Liu, L. Z., Zhang, Y. Y. & Jin, H. J. On correlation between the hardness-to-strength ratio and the plastic Poisson’s ratio of nanoporous gold. Mater. Res. Lett. 11, 454–461 (2023).

Wu, Y., Markmann, J. & Lilleodden, E. T. On the consequences of intrinsic and extrinsic size effects on the mechanical response of nanoporous Au. Mater. Des. 232, 112175 (2023).

Jeon, H., Markmann, J. & Shi, S. Effects of structural hierarchy and size on mechanical behavior of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 273, 119954 (2024).

Crowson, D. A., Farkas, D. & Corcoran, S. G. Mechanical stability of nanoporous metals with small ligament sizes. Scr. Mater. 61, 497–499 (2009).

Rodriguez-Nieva, J. F., Ruestes, C. J., Tang, Y. & Bringa, E. M. Atomistic simulation of the mechanical properties of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 80, 67–76 (2014).

Ngô, B. N. D. et al. Anomalous compliance and early yielding of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 93, 144–155 (2015).

Beets, N., Farkas, D. & Corcoran, S. Deformation mechanisms and scaling relations in the mechanical response of nano-porous Au. Acta Mater. 165, 626–637 (2019).

Klomp, A. J., Stukowski, A., Müller, R., Albe, K. & Diewald, F. Influence of surface stress on the mechanical response of nanoporous metals studied by an atomistically informed continuum model. Acta Mater. 221, 117373 (2021).

Farkas, D., Caro, A., Bringa, E. & Crowson, D. Mechanical response of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 61, 3249–3256 (2013).

Mathesan, S. & Mordehai, D. Size-dependent elastic modulus of nanoporous Au nanopillars. Acta Mater. 185, 441–452 (2020).

Greer, J. R. et al. Plasticity in small-sized metallic systems: Intrinsic versus extrinsic size effect. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 654–724 (2011).

Mangipudi, K. R., Epler, E. & Volkert, C. A. Topology-dependent scaling laws for the stiffness and strength of nanoporous gold. Acta Mater. 119, 115–122 (2016).

Chen, Y. C. K. et al. Morphological and topological analysis of coarsened nanoporous gold by x-ray nanotomography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 213–215 (2010).

Rösner, H., Parida, S., Kramer, D., Volkert, C. A. & Weissmüller, J. Reconstructing a nanoporous metal in three dimensions: an electron tomography study of dealloyed gold leaf. Adv. Eng. Mater. 9, 535–541 (2007).

Mangipudi, K. R., Radisch, V., Holzer, L. & Volkert, C. A. A FIB-nanotomography method for accurate 3D reconstruction of open nanoporous structures. Ultramicroscopy 163, 38–47 (2016).

Hu, K., Ziehmer, M., Wang, K. & Lilleodden, E. T. Nanoporous gold: 3D structural analyses of representative volumes and their implications on scaling relations of mechanical behaviour. Philos. Mag. 96, 3322–3335 (2016).

Erlebacher, J., Aziz, M. J., Karma, A., Dimitrov, N. & Sieradzki, K. Evolution of nanoporosity in dealloying. Nature 410, 450–453 (2001).

Krekeler, T. et al. Silver-rich clusters in nanoporous gold. Mater. Res. Lett. 5, 314–321 (2017).

Fife, J. L. & Voorhees, P. W. The morphological evolution of equiaxed dendritic microstructures during coarsening. Acta Mater. 57, 2418–2428 (2009).

Li, Q.-J. & Ma, E. When ‘smaller is stronger’ no longer holds. Mater. Res. Lett. 6, 283–292 (2018).

Messerschmidt, U. Dislocation Dynamics During Plastic Deformation 1st edn, Vol. 503 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Greer, J. R., Oliver, W. C. & Nix, W. D. Corrigendum to “Size dependence in mechanical properties of gold at the micron scale in the absence of strain gradients” [Acta Mater 53 (6) (2005) 1821–1830]. Acta Mater. 54, 1705 (2006).

Savitskii, E. & Prince, A. Handbook of Precious Metals, Vol. 600 (Hemi- sphere Publishing Company, 1969).

Sedlmayr, A. et al. Existence of two twinning-mediated plastic deformation modes in Au nanowhiskers. Acta Mater. 60, 3985–3993 (2012).

Ma, D. et al. Crystal plasticity study of monocrystalline stochastic honeycombs under in-plane compression. Acta Mater. 103, 796–808 (2016).

Zhu, T., Li, J., Samanta, A., Leach, A. & Gall, K. Temperature and strain-rate dependence of surface dislocation nucleation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 25502 (2008).

Jennings, A. T., Li, J. & Greer, J. R. Emergence of strain-rate sensitivity in Cu nanopillars: transition from dislocation multiplication to dislocation nucleation. Acta Mater. 59, 5627–5637 (2011).

Chen, L. Y., He, M., Shin, J., Richter, G. & Gianola, D. S. Measuring surface dislocation nucleation in defect-scarce nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 14, 707–713 (2015).

Voyiadjis, G. Z., Saffarini, M. H. & Ruestes, C. J. Characterization of the strain rate effect under uniaxial loading for nanoporous gold. Comput. Mater. Sci. 194, 110425 (2021).

Artymowicz, D. M., Erlebacher, J. & Newman, R. C. Relationship between the parting limit for de-alloying and a particular geometric high-density site percolation threshold. Philos. Mag. 89, 1663–1693 (2009).

McCue, I., Benn, E., Gaskey, B. & Erlebacher, J. Dealloying and dealloyed materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 46, 263–286 (2016).

Swinehart, D. F. The beer-lambert law. J. Chem. Educ. 39, 333 (1962).

Henke, B. L., Gullikson, E. M. & Davis, J. C. X-ray interactions: photoabsorption, scattering, transmission, and reflection at E = 50-30000 eV, Z = 1-92. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 54, 181–342 (1993).

Gilbert, P. Iterative methods for the three-dimensional reconstruction of an object from projections. J. Theor. Biol. 36, 105–117 (1972).

den Broek et al. Correction of non-linear thickness effects in HAADF STEM electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy 116, 8–12 (2012).

Gálvez, A., Iglesias, A., Cobo, A., Puig-Pey, J. & Espinola, J. Bézier curve and surface fitting of 3D point clouds through genetic algorithms, functional networks and least-squares approximation. In Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2007: International Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, August 26−29, 2007. Proceedings, Part II (eds. Gervasi, O. & Gavrilova, M. L.) 680–693 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007).

Ashby, M. F. et al. Metal Foams: A Design Guide. (Butterworth Heinemann, 2000).

Prakash, A., Hummel, M., Schmauder, S. & Bitzek, E. Nanosculpt: A methodology for generating complex realistic configurations for atomistic simulations. MethodsX 3, 219–230 (2016).

Michielsen, K. & Kole, J. S. Photonic band gaps in materials with triply periodic surfaces and related tubular structures. Phys. Rev. B 68, 115107 (2003).

Park, H. S. & Zimmerman, J. A. Modeling inelasticity and failure in gold nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 72, 54106 (2005).

GitHub. The ITAP Molecular Dynamics Program. https://github.com/itapmd/imd (2025).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short – range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Bitzek, E. et al. Structural relaxation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170201 (2006).