Abstract

The mid-infrared (MIR) photonics market is rapidly expanding, driven by advancements in fiber-based MIR devices, particularly fiber lasers. However, the lack of robust MIR optical fibers remains a critical barrier to further technological progress. In this work, we present the fabrication of gallate glasses containing tantalum oxide, as it stands, the most robust mid-infrared glasses capable of being easily shaped into large bulk components, fibers or tapers. By introducing up to 20 mol% of tantalum oxide in a gallate glass, we achieve a two-order-of-magnitude improvement in water corrosion resistance, while the nonlinear refractive index increases tenfold compared to silica. Optimal thermal stability is attained at 10 mol% of tantalum oxide, enabling the fabrication of tens-of-meter-long optical fibers. Crucially, the addition of tantalum oxide enhances the gallate glass properties without compromising thermomechanical performance. The potential of these tantalo-gallate glasses is further demonstrated through supercontinuum generation in a laser-inscribed waveguide and a tapered fiber, spanning from the visible to 4.5 μm. This work establishes our developed tantalo-gallate glasses as a compelling alternative for photonic applications seeking robust mid-infrared materials, with the potential to overcome the critical barriers currently limiting the advancement of fiber-based MIR technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mid-infrared (MIR) photonics market, historically dominated by military applications, is now expanding rapidly due to increasing demand in biomedical and environmental fields. Covering wavelengths from 2.5 µm to 20 µm1, the MIR spectral range enables the detection of molecular vibrations in biological and organic compounds, allowing for applications such as selective thermal ablation of tissues2, including tumors3, and precise monitoring of air and water pollutants4,5. This growing interest has driven the need for advanced MIR-compatible materials and components, among which glass fibers play a crucial role. These fibers serve both passive (e.g., light delivery) and active (e.g., supercontinuum generation, amplification) functions6,7,8 and can be integrated into diverse photonic systems. However, only a few classes of inorganic non-metallic glasses are suitable for MIR applications. Indeed, their performance is dictated by their optical transparency and low phonon energy9,10, which are intrinsically governed by their chemical bonding, as described by the Szigeti relation11. Currently, three primary glass families, heavy-metal oxide, fluoride, and chalcogenide, are employed in fiber-based MIR photonic devices10.

Fluoride fibers represent the most technologically advanced MIR fiber platform, offering a broad variety of compositions and geometries with ultra-low optical losses (down to 1 dB km−1) up to 4.5 µm12. Their capability to incorporate rare-earth elements within a low-phonon-energy matrix enables the development of high-power MIR fiber lasers13,14. Since the early 2000s, significant efforts have also been dedicated to developing low-loss heavy-metal oxide fibers, particularly germanate- and tellurite-based systems, known for their stability and strong optical nonlinearity15,16,17. These advances have led to high-power fiber lasers and broadband MIR supercontinuum sources18,19. Meanwhile, chalcogenide glasses, composed of heavy chalcogen elements, exhibit the broadest MIR bulk transmission range, extending up to 25 µm. These materials have been widely explored for CO2 laser delivery and supercontinuum generation20,21. Their inherently low phonon energy also makes them, at least in principle, highly suitable for rare-earth doping, offering potential breakthroughs in MIR fiber lasers operation beyond 4 μm22,23.

Despite their advantages, the previous MIR glass families suffer from poor thermomechanical properties and/or moisture sensitivity, which hinder unjacketed fiber handling, post-processing, and resilience to thermal damage. As a result, their implementation in practical systems is often dictated by necessity rather than choice. The MIR photonics industry urgently requires materials that combine broad optical transparency with mechanical durability, akin to silica in the visible and near-infrared domains.

Gallium-based heavy-metal oxide glasses, known as gallates, emerged in the early 1990s as promising alternatives, exhibiting superior optical and thermomechanical properties compared to other heavy-metal oxide glasses24,25. Initially, gallium oxide was not expected to form stable glass networks due to the weak single-bond strength in its octahedral coordination26. However, through charge compensation mechanisms, provided by appropriate glass modifiers (e.g., Ba2+) it can establish a stable tetrahedral network, allowing it to function as a primary glass former. This discovery enabled the synthesis of gallate glasses via conventional melt-quenching techniques, without requiring extreme cooling rates such as those used in levitation-based methods27. Despite these advances, gallate glasses have historically faced devitrification challenges during fiber drawing using the preform-to-fiber technique.

The preform-to-fiber technique, which takes advantage of the viscosity-temperature behavior of glasses, has been widely employed for drawing not only coreless preforms but also more complex structures, such as core–cladding designs (fabricated via built-in casting, rod-in-tube, etc.) and microstructured preforms (e.g., hollow-core, suspended-core, and photonic crystal fibers)10. However, this technique carries a risk of glass devitrification, as it involves heating the preform to temperatures near its softening point, which are also close to the glass crystallization temperature. To overcome this limitation in gallate glasses, our research has focused on integrating germanium oxide into gallate matrices to enhance glass stability while maintaining a gallium-rich composition28. This approach has enabled the fabrication of low-loss fibers29, laser-grade bulk materials30, and waveguide structures via laser inscription31,32. However, a crucial milestone remained unachieved: demonstrating nonlinear applications such as supercontinuum generation in gallate glasses.

In this work, we present for the first time and to the best of our knowledge supercontinuum generation in gallate glasses, covering a broad Vis-MIR spectral range from 0.6 up to 4.5 μm. We first optimize the glass composition by partially replacing germanium oxide with tantalum oxide. This substitution enhances the nonlinear optical response (i.e., nonlinearity) while preserving thermomechanical stability. A detailed characterization of the optical, structural, and thermal properties is performed. It includes chemical durability, thermal stability, hardness, Raman response, optical transmission, and both linear and nonlinear refractive indices. Finally, we demonstrate supercontinuum generation in these tailored tantalo-gallate glasses using both laser-inscribed waveguides and tapered fibers, supported by numerical simulations.

Results and Discussion

Investigation of the glass structure-property relationship

Enhancing a glass nonlinearity primarily involves increasing its nonlinear refractive index33. From a chemical standpoint, this can be achieved by incorporating specific cations with particular electronic configurations, ranked in order of ability to increase the glass nonlinearity: alkali or alkaline-earth (e.g., K+, Ba2+), d10 (e.g., Ga3+, Ge4+ and In3+), d0 (e.g., Nb5+, Ti4+, Ta5+) and ns2 ions (e.g., Te4+ and Pb2+)33. However, to preserve the high thermomechanical stability of gallate glasses, only a subset of these ions can be selected. While ns2 ions would be ideal for maximizing nonlinearity, their incorporation significantly compromises the glass thermomechanical properties25. In contrast, d0 ions provide the optimal balance between increasing nonlinearity and maintaining the elevated thermomechanical properties of gallate glasses. Therefore, we have chosen tantalum oxide as a key element. Its +V oxidation state is chemically stable, and it has already been successfully incorporated in significant amounts into lanthano-gallate systems34. Here, the influence of the germanium oxide substitution for tantalum oxide has been investigated from 0 up to 25 mol% of TaO5/2. A summary of the glass nominal compositions and their properties is presented in Table 1. Note that up to 20 mol% of TaO5/2, glasses did not lead to devitrification during casting. The EPMA chemical analyses did not reveal any variation of more than 1 mol% from the nominal compositions, consistent with a homogeneous glass synthesis without noticeable evaporation.

Bulk optical transmission spectra of all vitrified samples are shown in Fig. 1a. The transmission window spans from the UV up to the mid-infrared. Correlated with the photographs inserted in Fig. 1a, as the tantalum content increases, a new weak absorption band (<1 cm−1) appears around 450 nm giving a yellowish color to the glass. This results from the inadvertent incorporation of platinum ions from the platinum crucible35,36. Meanwhile, as the tantalum content increases, the mid-infrared optical window shifts to longer wavelength, in agreement with theoretical expectations. Indeed, the substitution of Ge4+ for Ta5+ ions with both a weaker single bond strength (102 kcal and 72 kcal for Ge-O and Ta-O, respectively) and heavier mass (73 g mol−1 and 181 g mol−1 for germanium and tantalum, respectively) allows for minimizing the multiphonon absorption contributions of Ge-O bonds observed near 6 μm. Additionally, all glasses have an absorption band located at 3000 nm and 4300 nm, due to the presence of hydroxyl groups as the samples were synthetized in ambient air37.

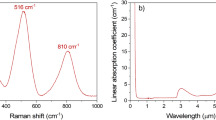

The glass structure has been investigated via Raman spectroscopy for the five glasses. All Raman spectra were normalized by their area, allowing for a good relative comparison of their Raman contributions (Fig. 1b). In gallate and germanate glass systems, three regions can be observed in the high (600–1000 cm−1), mid (400–600 cm−1) and low (200–400 cm−1) frequencies. The high frequency domain is attributed to symmetric and antisymmetric stretching modes of gallium and germanium tetrahedral units [TO4]28,38. The mid-frequency domain is characteristic of vibrational contributions of T-O-T bending with in-the-plane oxygen motions38,39. Lastly, the low frequency contributions are assigned to network-modifying cations vibrating in large interstitial sites and T-O-T bending with out-of-plane oxygen motions38,39. For glasses containing tantalum oxide, a single distinctive contribution appears at about 700 cm−1, characteristic of tantalate structural units in six-fold coordination ([TaO6])40,41. All Raman assignments are summarized in Table 2.

Raman signature of the tantalum-free composition presents two main bands peaking at 510 and 810 cm−1 with a barely visible shoulder at 450 cm−1. Since the gallium content is 1.5 times larger than that of germanium, the alternation of gallium and germanium tetrahedral units within the glass network is expected to follow a similar trend. Consequently, the formation of two directly linked [GeO4] units is likely rare, which explains the minimal band contribution at 450 cm−1, typically associated with Ge–O–Ge bridges. In contrast, the dominant response at 510 cm−1 strongly aligns with a glass structure rich in [GaO4]− units39. In the meantime, the amount of positive-charge compensators provided by Ba2+ ions exceeds what is needed to stabilize the [GaO4]− units. As a result, the excess Ba2+ ions, accounting for approximately one-third of the total barium content, contribute to the depolymerization of the glass network, leading to the formation of Ge∅3O− entities. These entities correspond to GeO4 tetrahedral units with three bridging oxygens (∅) and one non-bridging oxygen (O−). The second most intense spectral contribution, peaking at 810 cm−1, is attributed to the presence of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) within these Ge∅3O− units39. With the increase of tantalum oxide at the expense of germanium oxide in our glasses, the contributions at 450 and 500 cm−1 progressively decrease to give rise to strong bands at 650 and 710 cm−1. The tantalum cations are incorporated into the glass network predominantly in their preferred octahedral configuration as the 710 cm−1 band increases linearly. The replacement of Ge4+ ions for Ta5+ ions suppresses progressively the last Ge–O–Ge bridges while keeping almost unaffected the Ge∅3O− units at 810 cm−1. In the meantime, the gallate tetrahedral units are impacted as the 650 cm−1 band is indicative of non-bridging oxygens on [GaO4]− structural units42,43. Indeed, the excess of Ba2+ ions that were compensating the Ge∅3O− entities when the content of germanium was higher are now depolymerizing the gallate network by forming non-bridging oxygens on [GaO4]− structural units.

The Vickers hardnesses are reported in Fig. 1c. From 0 up to 20 mol% of TaO5/2, the glass hardness is significantly increased by 25% reaching 6.0 GPa, but this increase is not linear with the tantalum content. Typically, glass hardness is primarily influenced by two factors: free volume and bond strength44. As observed in the Raman spectra, germanium cations predominantly form tetrahedral units, while tantalum cations adopt an octahedral configuration. The substitution of germanium with tantalum reduces the glass free volume, as confirmed by the evolution of oxygen packing density (Supplementary Fig. 1), which aligns with the overall increase in glass hardness. However, since the Ta–O single bond is weaker than the Ge–O bond, it partially counteracts the hardness improvement induced by the free volume reduction. Additionally, the gallate glass network becomes more depolymerized due to the formation of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) on gallate structural units, which could also minimize the hardness improvement. These competing effects contribute to the nonlinear increase in glass hardness. As a comparison, the Vickers hardness of tellurite (<3 GPa), lead-germanate (<3 GPa), and fluoride glasses (<2 GPa) remains significantly lower than the 5-6 GPa range shown for our tantalo-gallate glasses16,45,46, particularly when considering compositions suitable for fiber drawing.

Chemical durability of gallate glasses immersed in deionized water is reported in Fig. 1d. Thanks to the addition of tantalum oxide in the gallate glasses, a clear improvement of the chemical durability is observed. Indeed, even after being exposed for one week, the 20Ta sample is still completely undamaged on the surface, while the composition free of tantalum became slightly opaque. This difference of chemical sensibility is demonstrated by the huge change in terms of corrosion rate, evaluated at 0.126 mg cm−2 h−1 and 0.003 mg cm−2 h−1, for the glass without and with 20 mol% of TaO5/2, respectively. Additionally, to push even further the experiment on our glass compositions, both samples with 15 and 20 mol% of tantalum oxide, were immersed in deionized water now heated at 50 °C for several days. While the 15Ta sample presents a low corrosion rate of 0.017 mg cm−2 h−1, the glass with the highest amount of tantalum still degrades extremely slowly at a rate of 0.004 mg cm−2 h−1. Already studied in barium gallo-germanate and indium-containing germanate glasses, both the decrease of germanium content and the addition of octahedral structural units have been reported to increase the glass durability by decreasing the free volume47,48. Replacing the germanium ions with highly coordinated Ta5+ cations thus noticeably increases the gallate glass durability.

The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analyses were carried out on the gallate glasses on powder (Fig. 2a) and bulk (Fig. 2b) forms. Glass transition temperatures (Tg), onsets of crystallization (Tx) and glass stabilities (ΔT), calculated from the difference between Tx and Tg for the powder were extracted from Fig. 2a and plotted in Fig. 2c. Through the introduction of tantalum ions in the glass compositions, the Tg increases nonlinearly from 710 to 780 °C which is consistent with the decrease of free volume and increase of cross-linking brought by the tantalum ion in octahedral configuration. In the meantime, the Tx firstly drops with the introduction of 5 mol% of TaO5/2 from 905 to 865 °C, then slightly increases up to 15 mol% of TaO5/2, to finally re-decreasing down to 880 °C. The ΔT is maintained above 100 °C except for the 20Ta glass composition. As a general rule of thumb, an ideal ΔT above 100 °C is preferred to consider fiber drawing from the preform-to-fiber technique. By monitoring the difference of maximal crystallization temperature (ΔTc) extracted from the DSC performed on bulk and powder forms, the main type of crystallization can be determined. Indeed, with a large surface area, DSC performed on glass powder favors surface crystallization, while DSC performed on glass bulk favors volume crystallization.

Effect of germanium oxide substitution for tantalum oxide on the differential scanning calorimetry analyses performed on a powder and b bulk forms. Extracted values of c glass transition temperatures, onsets of crystallization, glass stabilities for powder and d differences between bulk and powder crystallization temperatures. For c and d lines are drawn as a guide to the eye and the error bars are confounded with data points.

In Fig. 2d ΔTc is plotted over the concentration of tantalum oxide. At low concentration of tantalum oxide, the glass preferentially crystallizes from the surface, while above 15 mol%, the glass devitrifies preferentially from its volume. This change in crystallization behavior is consistent with a strong restructuration in the glass network induced via the incorporation of tantalum oxide. In the meantime, it is observed that from 15 mol% of TaO5/2 in Fig. 2b, the bulk crystallization peak is intense and sharp, indicative of aggressive crystallization. Hence, considering the overall glass thermal stability in terms of ΔT and crystallization behavior, the fiber drawing of our tantalum-containing gallate glasses is expected to be feasible up to at least 10 mol% of TaO5/2 from the preform-to-fiber technique. As a first demonstration of fiber drawing viability in this glass system, we report the drawing of a 50 m-long 250 μm-diameter coreless fiber of the glass composition containing 10 mol% of TaO5/2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Cut-back loss measurement were performed and presented in Fig. 6e. No devitrification was observed either at the fiber surface or in its volume. Additionally, various robust fiber tapers with a 1:10 ratio were shaped by means of the common heat-and-stretch technique (Vytran GPX3800), thus demonstrating the ease of thermal post-processing of such glass fibers (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The linear and nonlinear refractive indices were measured on all five glasses. In Fig. 3a, the linear refractive index is strongly increasing with the increase of tantalum content, with Δn in excess of 0.1 from 0 up to 20 mol% of TaO5/2. The linear optical susceptibility χ(1) is plotted in inset and shows a clear linear evolution. Here, due to the high electron density of the Ta5+ ions, there is no doubt that these ions are mainly driving the linear increase of the refractive index, as reported in similar lanthano-gallate glass systems34.

Determined from Z-scan measurements, the nonlinear refractive indices at 1030 nm, normalized to the measured n2 value of an F300 silica sample (2.8 × 10−20 m2 W−1), are presented in Fig. 3b. In the absence of tantalum oxide, the glass exhibits an n2 value more than five times higher than that of silica glass. As the tantalum content increases, n2 follows a linear trend, ultimately exceeding an order of magnitude compared to silica glass, similar to some commercial tellurite and lead silicate glass compositions49.

Supercontinuum generations in tantalum-containing gallate glasses

As presented in the Introduction, heavy-metal oxide glasses based on ns2 elements, such as tellurites and lead-germanates, exhibit high nonlinear refractive indices (up to 100 times the n2 value of silica) and broad mid-infrared bulk transmission (up to 6 μm). However, these advantages are offset by low glass transition temperatures (<400 °C) and poor mechanical strength (Vickers hardness below 3 GPa), intrinsic to the presence of ns2 lone-pair electrons. A similar trade-off is observed in chalcogenide glasses, where the heavy chalcogen anions responsible for high n2 (up to 1000 times the n2 value of silica) and extended MIR bulk transparency (up to 25 μm) also significantly reduce Tg (often below 200 °C), limiting mechanical property (Vickers hardness below 2 GPa). Fluorine-based glasses, such as fluoroindate, offer excellent MIR bulk transparency (up to 9 μm) and high rare-earth solubility due to their unique combination of heavy-metal cations and fluorine. Nevertheless, the inherently weak ionic bonding in fluoride glasses results in low thermomechanical performance, with Tg and hardness typically below 300 °C and 2.2 GPa, respectively, and pronounced sensitivity to moisture. Across all these MIR glass families, a persistent limitation has been their poor ability to produce robust, easy-to-handle optical fibers, particularly in unjacketed configurations. In this context, the development of tantalo-gallate glasses represents a significant advancement, offering a compelling balance of extended MIR bulk transparency (> 5.8 μm), high nonlinearity (one order of magnitude higher than silica), and superior thermomechanical properties (Tg at 750 °C with Vickers hardness of 5.6 GPa) conducive to the fabrication of durable and practical MIR fiber devices. Key properties of main MIR glass fiber systems are summarized in Table 3.

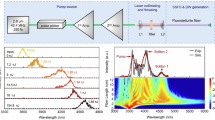

Here, we present two demonstrations of supercontinuum generation (SCG) using our glasses: one in a laser-inscribed waveguide and another in a tapered fiber. To summarize the key experimental parameters for the supercontinuum generation in both demonstrations, the latter are denoted in Table 4.

The first demonstration employed a laser-inscribed waveguide embedded in a 4 cm-long bulk sample of gallate glass containing 17.5 mol% of TaO5/2 (the reader is referred to the Experimental section for details on the laser irradiation conditions). This tantalum concentration was selected because it yields an n2 value roughly one order of magnitude higher than that of silica, still allowing fabrication in a long bulk form. A similar demonstration could likely have been achieved using the 20 mol% TaO5/2 composition. Yet, it was not explored in this work. In the second demonstration, a tapered gallate glass coreless fiber containing 10 mol% of TaO5/2 was used. This composition was chosen to enable the drawing of crystal-free fibers via the preform-to-fiber technique while maintaining high n2. It was preferred over higher tantalum concentrations (e.g., 15Ta and 20Ta), which exhibit lower glass stability. However, it is worth noting that no fiber drawing attempts were reported for these richer compositions. Also, the coreless fiber was preferred over conventional core–clad designs due to its ease of fiber fabrication while providing the strong light confinement suitable for the SCG50. The SCG setup is presented in Fig. 4 and detailed in the Experimental section.

Supercontinuum generations in laser-inscribed waveguide

Owing to the nonlinear nature of its absorption, ultrafast lasers are now widely recognized as a reliable tool for microscale processing of complex three-dimensional structures within the bulk of materials. This capability enables the fabrication of three-dimensional waveguides and compact integrated photonic devices51,52. In this work, a usual one-dimensional waveguide was inscribed in a 4 cm-long 17.5Ta glass sample (Fig. 5a) and optimized to achieve a near-circular transverse profile with a refractive index change Δn of the order of 1 × 10−3. As for the waveguide diameter, it was established as a trade-off between easing pump coupling and reducing the number of transverse modes. Accordingly, the following laser inscription parameters were selected: scanning speed of 5 mm s−1, pulse energy of 190 nJ, and a repetition rate of 5 MHz. The resulting laser-inscribed waveguide cross-section, shown in Fig. 5b, exhibits a cross-section with an aspect ratio of 1:1.4 and a diameter of 30 μm. The refractive index change, inferred from phase contrast imaging (Fig. 5c), is slightly above 1 × 10−3, enabling the propagation of 5 transverse modes near 1.9 μm. The resulting experimental SCG spectra are presented in Fig. 5d.

Photographs of a an 8 cm-long gallate bulk glass containing 17.5 mol% of TaO5/2 and its laser-inscribed SC waveguide: b waveguide cross-section and c top view obtained by optical and phase contrast imaging, respectively. SC spectra obtained d experimentally in the laser-inscribed waveguide for distinct input peak powers at 1755 nm and e corresponding numerical results. f Numerical SC evolution along propagation length with a 500-kW peak power. In b and c, the laser incident direction is featured with a white symbol on the top right corner.

Considering both material and waveguide contributions, we estimated the properties of the fundamental guided mode LP01 of the inscribed waveguide through numerical solutions of the dispersion equation for cylindrical step-index geometries53. The calculation employed fitted refractive index curves for both the core and cladding, incorporating a refractive index contrast of the order of 1 × 10−3. At a pump wavelength of 1755 nm, the waveguide exhibits normal dispersion (β2~0.025 ps2 m−1), with a zero-dispersion wavelength (ZDW) around 1.94 µm. Due to the low laser repetition rate (1 kHz), the average output power from the waveguide remains low, on the order of tens of µW. Consequently, the peak power values used in simulations align with experimentally measured average power levels, assuming free-space to fiber coupling losses exceeding 10 dB in agreement with estimated experimental coupling losses. Figure 5e presents simulated spectra for different peak powers. At lower power levels, spectral broadening is primarily driven by self-phase modulation (SPM) and optical wave breaking, resulting in a nearly symmetric spectrum centered around the pump wavelength (1.6-2.0 µm)54. At the highest peak power (P0 = 500 kW), symmetry breaks upon reaching the ZDW, leading to an SC spectrum spanning 1.4–2.3 µm at −20 dB. In fact, as the pump wavelength approaches the ZDW, some energy is transferred into the anomalous dispersion regime. As a result, both normal dispersion and soliton-related dynamics coexist, leading to an asymmetric spectral broadening55. A good agreement is observed between the numerical and experimental results, particularly in spectral shape at high peak power and in the ZDW crossing near 1.9 µm. To further illustrate SCG dynamics, Fig. 5f shows the spectral evolution along the waveguide at 500 kW peak power. Most of the broadening occurs within the first few centimeters of propagation, consistent with previous laser-inscribed SCG waveguides in tellurite and chalcogenide glasses, where comparable pulse energies yielded spectra spanning several hundred nanometers55,56. The combination of high peak power, a pump wavelength near the ZDW, and the high nonlinearity of the glass promotes substantial spectral broadening. Even broader SC spectra could be achieved by pumping in the anomalous dispersion regime (i.e., above 2 µm), where higher-order soliton fission, dispersive wave emission, and Raman-induced soliton self-frequency shift (SSFS) can further extend the spectrum57. Additionally, optimizing the waveguide diameter and increasing the refractive index contrast would further enhance SCG dynamics58.

Supercontinuum generations in tapered fiber

In a final set of experiments, we investigated supercontinuum generation in a tapered gallate coreless fiber. Initial SCG results were obtained in non-dehydrated tapered fibers (Supplementary Fig. 3), however, due to the high hydroxyl (OH−) content in the glass, the SC spectra were limited to below 2.7 μm (Supplementary Fig. 3). To overcome this limitation, we synthesized the same 10 mol%-TaO5/2 gallate glass composition (Fig. 6), ensuring rigorous dehydration following the optimized protocol reported in a previous work29. The dehydrated 10 mol%-TaO5/2 gallate glass exhibits even better thermal stability with a ΔT of 180 °C (Fig. 6d), leading to crystal-free fibers (Supplementary Fig. 3). The fiber had an initial diameter of 125 µm, tapering down to a waist diameter of 15 µm. The taper transition lengths were both 12.5 mm long, separated by a waist length of 20 mm (Fig. 7a). Fiber propagation losses were measured to be below 5 dB m−1 in the 1-3.6 μm region, with a minimum below 1 dB m−1 around 2 μm (Fig. 6e). For a 5 cm-long taper, such losses are actually negligible. Similarly to the inscribed waveguide, we investigated the properties of the fundamental guided mode LP01. We consider the taper to have a step-index profile with an infinite air cladding (n = 1). We made use of the fitted curve of the refractive index shown in Fig. 3 for the 10Ta as the core composition. For a pump wavelength of 1900 nm, the fiber exhibits normal dispersion (β2~0.006 ps2 m−1) at a diameter of 125 µm, and anomalous dispersion (β2~−0.01 ps2 m−1) in the 15 μm-waist section. The coupled peak powers were estimated from the average output power measured at the fiber exit. The maximum average power reached approximately 200 µW, corresponding to a peak power of ~ 3 MW. Assuming equivalent coupling conditions, we applied attenuation ratios based on the filter optical densities, leading to estimated peak powers of 300 kW and 30 kW.

a Scheme and photographs of a 4.5 cm-long fiber taper fabricated from the dehydrated 10Ta glass fiber. SC spectra obtained b experimentally in the laser-inscribed waveguide for distinct input peak powers at 1900 nm and c corresponding numerical results. d Numerical SCG evolution along propagation length with a 3-MW peak power.

Experimental results and corresponding numerical simulations of the SC spectra under these conditions are shown in Fig. 7b, c. At the lowest peak power, the SCG remains limited, with broadening primarily driven by self-phase modulation (SPM). However, at the highest peak power, the tapered fiber produces a broad supercontinuum spanning from 0.6 µm up to the CO2 absorption band at 4.3 µm, with a 40 dB dynamic range. This result can be attributed not only to the high peak power injection but also to the strong optical confinement and enhanced nonlinearity in the waist region compared to the initial 125-µm diameter section50. As illustrated in Fig. 7d, the most pronounced spectral broadening occurs within the first 15 mm of propagation, particularly near the transition between the down-taper and the fiber waist. In this region, soliton fission takes place, leading to the formation of multiple soliton-like pulses that undergo soliton self-frequency shift (SSFS), while short-wavelength components may originate from dispersive wave emission. Considering the simulation of the fundamental mode only, the soliton order N (\({N}^{2}=\gamma {{P}_{0}T}_{0}^{2}/|{\beta }_{2}|\)) for a peak power of 3 MW, is approximately 9 for a diameter of 125 µm, and 55 for a diameter of 15 µm53. This underlines the strong nonlinear regime achieved in the waist region, where complex soliton dynamics, including fission and Raman-induced self-frequency shifts, are expected to play a dominant role.

Experimental and numerical results show a good agreement in terms of spectral bandwidth across all peak powers. However, differences in spectral shape can be attributed to the highly multimode nature of the tapered fiber and initial coupling conditions, as evidenced by the residual pump energy in the experimental spectrum, whereas in simulations, all pump energy is redistributed across new wavelengths. The numerical SC simulations were based on the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation (GNLSE) model, which only considers the fundamental mode propagation50. However, in practice, the high refractive index contrast between the coreless fiber and the air-cladding makes the fiber highly multimode. For short pulses (<10 ps), fundamental-mode-only simulations generally provide a good approximation of SCG dynamics and spectral bandwidth, as higher-order modes contribute less to spectral broadening59. This experimental demonstration, achieving SCG from the visible to 4.5 µm, is the first of its kind in gallate glass. While this spectral range does not extend as far as 5 µm, as achieved in some fluoride-based compositions60, it remains comparable to tellurite fiber-based SC sources19. This result underscores the strong potential of tantalo-gallate glass fibers. Moreover, given their excellent thermomechanical properties, further dispersion engineering (e.g., step-index or W-type fiber designs) could enable high-power SCG (tens of watts or more) across the 1-5 µm range, comparable to what is achievable in ZBLAN or fluorotellurite fibers61,62.

Conclusion

In this study, we have developed, to the best of our knowledge, the most robust mid-infrared glasses capable of being easily shaped into large bulk components, fibers, or tapers without requiring extraordinary precautions. By replacing germanium oxide with tantalum oxide, we have significantly enhanced the glass nonlinearity, reaching an order of magnitude higher than SiO2. At the same time, this substitution has improved the glass chemical durability and thermomechanical resilience. Our comprehensive investigation demonstrates that these tailored glass compositions provide an optimal balance between low water corrosion rates, high glass transition temperatures, superior hardness, and extended mid-infrared transparency. Additionally, we have achieved nonlinear optical applications (e.g., supercontinuum generation) of gallate glasses over almost the entire transparency window, from the visible to the mid-infrared. This was demonstrated in a laser-inscribed waveguide (1.3-2.3 μm) and a fiber taper (0.6-4.5 μm). In summary, our tantalo-gallate glasses present a compelling alternative for photonic applications seeking robust mid-infrared materials that can be shaped into bulk and fiber components. These glasses hold the potential to overcome critical barriers currently limiting the advancement of fiber-based MIR technologies.

Method

Glass synthesis

Gallate glass system 42 GaO3/2−30 BaO–(28-x) GeO2–x TaO5/2 (with x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25) was investigated. For each composition, 30 g of glasses was fabricated by melting 4 N (99.99%) commercial oxide precursors into a platinum crucible in a conventional heating furnace between 1500 °C and 1650 °C in ambient air. Each glass bulk was then quenched by casting the molten materials onto a metallic plate. The glass bulk is finally annealed at its glass transition temperature minus 30 °C before any further sample preparation. The long glass bulk used for the demonstration of the supercontinuum generation in a laser-inscribed waveguide was fabricated via the same method. A heavier mass of glass was fabricated in order to cast an 8 cm-long glass slide, reaching around 70 g.

The dehydrated glass preform was fabricated under a controlled atmosphere during both the melting and casting steps. Glass melting was carried out under a dry nitrogen gas flow, with a small amount of ammonium bifluoride added to the melt as a dehydrating agent. The casting process was then performed inside a glove box filled with dry nitrogen to further prevent moisture contamination. A similar purification method was employed in reference29.

Preform fiber drawing

Both dehydrated and not dehydrated glass preforms were inserted inside a furnace under an argon atmosphere. Between 900 and 1000 °C, the fiber drawing is initiated, then the glass fiber is carefully wound manually on a capstan.

Fiber loss measurement

Propagation losses of the fibers were measured by the cut-back method. Measurements were performed using supercontinuum sources (Targazh SYSTEMS SC01 and NKT SuperK compact) and optical spectrum analyzers. All fiber cleaves were made using a Vytran LDC401A cleaving system and methodically inspected with a microscope objective.

Glass characterizations

The UV–visible–near-IR transmission spectra (200−1100 nm) were measured using a Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrometer (Agilent) with a 1 nm step size, while the near-IR to mid-IR transmission spectra (1−7 μm) were acquired using a Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer, averaging 50 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The optical transmission measurements were performed on 2-mm-thick optically-polished samples, then converted in linear absorption coefficient.

Raman spectra were acquired at room temperature on optically-polished sample over the range of 200−1100 cm−1 using a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope equipped with a 50X objective and a continuous-wave 633 nm laser.

The chemical durability was measured by immersing flat glass samples in 18 MΩ cm−1 deionized water at room temperature. The samples were immersed in fresh water after each weighing. For 15Ta and 20Ta glass samples, the glass slides were immersed in the same quality water but at 50 °C to accelerate the ageing process and assess more precisely the weight loss.

Glass hardness was measured on optically-polished samples via Vickers micro-indentation technique conducted at 200 gf. Three measurements were carried out on each sample then averaged.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were carried out with a DSC 404 F3 Pegasus calorimeter at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 on both single glass chunk and glass powder.

Chemical analyses were conducted by electron-probed microanalysis (EPMA) on a CAMECA-SX100 apparatus. Wavelength Dispersive Spectroscopy (WDS) was acquired to measure the cationic elements, with an average value based on 8 acquisitions.

The refractive indices were measured at five different wavelengths (532 nm, 632.8 nm, 972.4 nm, 1308.2 nm, and 1537.7 nm) with a prism coupler refractometer (Metricon, 2010/M).

The nonlinear refractive indices n2 were measured by the Z-scan method63. The output of a 1030 nm femtosecond laser (Clark-MXR Impulse) was passed through a spatial filter to clean-up the beam and improve its quality before being focused through a thin sample using a 150 mm focal length lens. The sample was mounted on a linear stage and was translated across the focal spot. The transmitted power was recorded using a photodetector (Newport 818-SL) with an aperture of variable size. Open and closed-aperture scans were performed to retrieve the magnitude of the nonlinear refractive indices.

Direct laser writing setup

an 8 cm-long optically-polished glass slide was irradiated by a frequency-doubled femtosecond laser (Clark-MXR Impulse) at 515 nm with a pulse duration of 300 fs. A λ/4 waveplate was inserted in the beam path to induce circular polarization. The glass slide was mounted on a computer-controlled 3D motorized stage (Aerotech PlanarDL-200 and ANT130) so that it could be translated with respect to the position of the laser beam. The pulses were focused approximately 250 μm below the surface of the samples using a 100×/0.85 NA microscope objective equipped with a correction collar for spherical aberration (Olympus LCPLN100XIR). A preliminary investigation of the direct laser writing of the glass slide was performed at various writing depths and objective correction to assess the required aberration and non-linear propagation compensation to achieve a circular waveguide cross-section64. The laser-induced waveguide was inscribed at a scanning speed of 5 mm s−1, with a pulse energy of 190 nJ and repetition rate of 5 MHz. The refractive index change was assessed by phase contrast imaging using a commercial SID4Bio Phasics camera, more specifically detailed in ref. 65.

Supercontinuum experiments

A tunable optical parametric amplifier (Topas Prime) pumped by an 800 nm Ti:Sapphire regenerative amplifier (Spectra Spitfire Ace) was used as the pulse pump laser (~65 fs) for supercontinuum generation. Light was coupled into the laser-inscribed waveguide and single-index fiber with 50- and 100-mm focal length lenses, respectively, resulting in beam sizes of 21 μm and 46 μm. The careful selection of the coupling lens was required to favor preferential excitation of the fundamental guided mode50. The laser power was modulated using various neutral density filters inserted in the beam path before the lens. Light was collected at the end of the waveguide and fiber using a large-core InF3 fiber butted against the sample and conveyed into an optical spectrum analyzer to monitor the output spectrum. Additionally, since the supercontinuum simulation (presented below) showed no significant spectral broadening beyond 4 cm of propagation, the glass sample was cut to this length prior to the SCG experiment.

Supercontinuum simulations

Numerical simulations were carried out using the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation (GNLSE)57. Simulations were based on the full dispersion curve of the fundamental guided mode, along with the instantaneous Kerr and delayed Raman nonlinear responses and the nonlinearity dispersion, which includes the frequency dependence of the effective mode area. The nonlinear Kerr refractive index n2 is taken to be 2.8 × 10−19 m2 W−1 and 2.2 × 10−19 m2 W−1 for the laser-inscribed waveguide and gallate fiber, respectively. For the Raman response function, we employed an intermediate broadening model that combines Lorentzian and Gaussian convolutions66, adapted from the spontaneous Raman scattering spectra presented in Fig. 1.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The simulations code used in this manuscript is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jackson, S., Pawliszewska, M. & Vallée, R. (Eds.) Mid-Infrared Fiber Photonics: Glass Materials, Fiber Fabrication and Processing, Laser and Nonlinear Sources. (Woodhead Publishing, 2022).

Bernstein, E. et al. The 2910-nm Fiber Laser Is Safe and Effective for Improving Acne Scarring. Lasers Surg. Med. 56, lsm.23845 (2024).

Larson, E. et al. Mid-infrared absorption by soft tissue sarcoma and cell ablation utilizing a mid-infrared interband cascade laser. J. Biomed. Opt. 26, 043012 (2021).

Sonnenfroh, D. M. et al. Pollutant emission monitoring using QC laser-based mid-IR sensors. In Pollutant emission monitoring using QC laser-based mid-IR sensors (eds. Vo-Dinh, T. & Spellicy, R. L.) 86 (Boston, MA, 2001).

Baudet, E. et al. Development of an evanescent optical integrated sensor in the mid-infrared for detection of pollution in groundwater or seawater. Adv. Device Mater. 3, 23–29 (2017).

Séguin, A., Becerra-Deana, R. I., Virally, S., Boudoux, C. & Godbout, N. Fabrication and characterization of indium fluoride multimode fused fiber couplers for the mid-infrared. Opt. Express 31, 33670 (2023).

Nilsson, J. & Payne, D. N. High-power fiber lasers. Science 332, 921–922 (2011).

Petersen, C. R. et al. Mid-infrared supercontinuum covering the 1.4–13.3 μm molecular fingerprint region using ultra-high NA chalcogenide step-index fibre. Nat. Photonics 8, 830–834 (2014).

Jackson, S. D. Mid-infrared fiber laser research: Tasks completed and the tasks ahead. APL Photonics 9, 070904 (2024).

Tao, G. et al. Infrared fibers. Adv. Opt. Photonics 7, 379 (2015).

Varshneya, A. K. & Mauro, J. C. Fundamentals of Inorganic Glasses. (Elsevier, Amsterdam Oxford, Cambridge, MA, 2019).

Poulain, M., Cozic, S. & Adam, J. L. Fluoride glass and optical fiber fabrication. In Mid-Infrared Fiber Photonics 47–109 (Elsevier, 2022).

Duval, S. et al. Femtosecond fiber lasers reach the mid-infrared. Optica 2, 623 (2015).

Aydin, Y. O., Fortin, V., Vallée, R. & Bernier, M. Towards power scaling of 2.8 μm fiber lasers. Opt. Lett. 43, 4542 (2018).

Dorofeev, V. V. et al. High-purity TeO2–WO3–(La2O3,Bi2O3) glasses for fiber-optics. Opt. Mater. 33, 1911–1915 (2011).

Maldonado, A. et al. TeO2-ZnO-La2O3 tellurite glass system investigation for mid-infrared robust optical fibers manufacturing. J. Alloy. Compd. 867, 159042 (2021).

Kim, S., Yoko, T. & Sakka, S. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of TeO2 glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 76, 2486–2490 (1993).

Wu, J., Yao, Z., Zong, J. & Jiang, S. Highly efficient high-power thulium-doped germanate glass fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 32, 638 (2007).

Thapa, R. et al. Mid-IR supercontinuum generation in ultra-low loss, dispersion-zero shifted tellurite glass fiber with extended coverage beyond 4.5 μm. In (eds. Titterton, D. H., Richardson, M. A., Grasso, R. J., Ackermann, H. & Bohn, W. L.) 889808 (Dresden, Germany, 2013).

Nishii, J. et al. Chalcogenide glass fibers for power delivery of CO2 laser. In (eds. Harrington, J. A. & Katzir, A.) 224 (Los Angeles, CA, 1990).

Lemière, A. et al. 1.7–18 µm mid-infrared supercontinuum generation in a dispersion-engineered step-index chalcogenide fiber. Results Phys. 26, 104397 (2021).

Seddon, A. B., Tang, Z., Furniss, D., Sujecki, S. & Benson, T. M. Progress in rare-earth-doped mid-infrared fiber lasers. Opt. Express 18, 26704 (2010).

Schweizer, T., Samson, B. N., Moore, R. C., Hewak, D. W. & Payne, D. N. Rare-earth doped chalcogenide glass fibre laser. Electron. Lett. 33, 414–416 (1997).

Dumbaugh, W. H. Infrared transmitting glasses. Opt. Eng. 24, 242257 (1985).

Lapp, J. C. & Dumbaugh, W. H. Gallium oxide glasses. Key Eng. Mater. 94–95, 257–278 (1994).

Sun, K.-H. Fundamental condition of glass forming. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 30, 277–281 (1947).

Yoshimoto, K., Ezura, Y., Ueda, M., Masuno, A. & Inoue, H. 2.7 µm mid-infrared emission in highly erbium-doped lanthanum gallate glasses prepared via an aerodynamic levitation technique. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1701283 (2018).

Guérineau, T. et al. Extended germano-gallate fiber drawing domain: from germanates to gallates optical fibers. Opt. Mater. Express 9, 2437 (2019).

Guérineau, T. et al. Toward low-loss mid-infrared Ga2O3–BaO–GeO2 optical fibers. Sci. Rep. 13, 3697 (2023).

Leonov, S., Guerineau, T., Bernier, M., Messaddeq, Y. & Vallee, R. Demonstration of a 0.8 W continuous wave bulk laser around 2 μm in a Tm3+:Ga-rich BGG glass. Opt. Mater. Express 14, 1690–1698 (2024).

Guérineau, T., Dupont, A., Lapointe, J., Vallee, R. & Messaddeq, Y. Investigation of the Ga2O3-BaO-GeO2 glasses for ultrafast laser inscription. Opt. Mater. Express 13, 2036–2052 (2023).

Dupont, A. et al. Lasing in a femtosecond-laser-written single-scan waveguide fabricated in Tm-doped BGG glass. Opt. Lett. 50, 666 (2025).

Dussauze, M. & Cardinal, T. Nonlinear optical properties of glass. In Springer Handbook of Glass (eds. Musgraves, J. D., Hu, J. & Calvez, L.) 193–225 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Yoshimoto, K. et al. Thermal and optical properties of La2O3 - Ga2O3 - (Nb2O5 or Ta2O5) ternary glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 101, 3328–3336 (2018).

Guérineau, T., Fargues, A., Petit, Y., Fargin, E. & Cardinal, T. The influence of potassium substitution for barium on the structure and property of silver-doped germano-gallate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 566, 120889 (2021).

Bevilacqua, J. M. & Eisenberg, R. Synthesis and characterization of luminescent square-planar Platinum(II) complexes containing Dithiolate or Dithiocarbamate Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 33, 2913–2923 (1994).

Jewell, J. M. & Aggarwal, I. D. Structural influences on the hydroxyl spectra of barium gallogermanate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 181, 189–199 (1995).

Skopak, T. et al. Structure and properties of Gallium-Rich Sodium Germano-Gallate Glasses. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 1370–1378 (2019).

McKeown, D. A. & Merzbacher, C. I. Raman spectroscopic studies of BaO-Ga2O3-GeO2 glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 183, 61–72 (1995).

Kokubo, T., Inaka, Y. & Sakka, S. Glass formation and optical properties of glasses in the systems (R2O or R’O)-Ta2O5-Ga2O3. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 80, 518–526 (1986).

Joseph, C., Bourson, P. & Fontana, M. D. Amorphous to crystalline transformation in Ta2O5 studied by Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 1146–1150 (2012).

Fukumi, K. & Sakka, S. Raman spectroscopic study of the structural role of alkaline earth ions in alkaline earth gallate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 94, 251–260 (1987).

Calzavara, F. et al. Glass forming regions, structure and properties of lanthanum barium germanate and gallate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 571, 121064 (2021).

Rouxel, T. Some strange things about the mechanical properties of glass. Comptes Rendus Phys. 24, 99–112 (2024).

Mansour, E., El-Damrawi, G., Fetoh, R. E. & Doweidar, H. Structure-properties changes in ZnO-PbO-GeO2 glasses. Eur. Phys. J. B 83, 133–141 (2011).

Delben, A., Messaddeq, Y., Caridade, M. D., Aegerter, M. A. & Eiras, J. A. Mechanical properties of ZBLAN glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 161, 165–168 (1993).

Higby, P. L. & Aggarwal, I. D. Properties of barium gallium germanate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 163, 303–308 (1993).

Bayya, S. S., Harbison, B. B., Sanghera, J. S. & Aggarwal, I. D. BaO-Ga2O3-GeO2 glasses with enhanced properties. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 212, 198–207 (1997).

Adair, R., Chase, L. L. & Payne, S. A. Nonlinear refractive-index measurements of glasses using three-wave frequency mixing. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 4, 875 (1987).

Serrano, E. et al. Towards high-power and ultra-broadband mid-infrared supercontinuum generation using tapered multimode glass rods. Photonics Res. 13, 1106–1115 (2025).

Lapointe, J. et al. Nonlinear increase, invisibility, and sign inversion of a localized fs-laser-induced refractive index change in crystals and glasses. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 1–12 (2020).

Gattass, R. R. & Mazur, E. Femtosecond laser micromachining in transparent materials. Nat. Photonics 2, 219–225 (2008).

Agrawal, G. Nonlinear Fiber Optics. (Elsevier, 2013).

Finot, C., Kibler, B., Provost, L. & Wabnitz, S. Beneficial impact of wave-breaking for coherent continuum formation in normally dispersive nonlinear fibers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 25, 1938 (2008).

Psaila, N. D. et al. Supercontinuum generation in an ultrafast laser inscribed chalcogenide glass waveguide. Opt. Express 15, 15776 (2007).

Okhrimchuk, A. G. et al. Direct Laser Written Waveguide in Tellurite Glass for Supercontinuum Generation in 2 μm Spectral Range. J. Light. Technol. 38, 1492–1500 (2020).

Dudley, J. M., Genty, G. & Coen, S. Supercontinuum generation in photonic crystal fiber. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 1135–1184 (2006).

Mackenzie, M. D. et al. GLS and GLSSe ultrafast laser inscribed waveguides for mid-IR supercontinuum generation. Opt. Mater. Express 9, 643 (2019).

Kubat, I. & Bang, O. Multimode supercontinuum generation in chalcogenide glass fibres. Opt. Express 24, 2513 (2016).

Théberge, F. et al. Watt-level and spectrally flat mid-infrared supercontinuum in fluoroindate fibers. Photonics Res. 6, 609 (2018).

Jiao, Y. et al. Over 50 W all-fiber mid-infrared supercontinuum laser. Opt. Express 31, 31082 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. 30-W supercontinuum generation based on ZBLAN fiber in an all-fiber configuration. Photonics Res. 7, 1061 (2019).

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T.-H., Hagan, D. J. & Van Stryland, E. W. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 760–769 (1990).

Lapointe, J. et al. Optimization of fs-laser-induced voxels in nonlinear materials via over-correction of spherical aberration. Opt. Lett. 49, 7048 (2024).

Bélanger, E., Bérubé, J.-P., De Dorlodot, B., Marquet, P. & Vallée, R. Comparative study of quantitative phase imaging techniques for refractometry of optical waveguides. Opt. Express 26, 17498 (2018).

Hollenbeck, D. & Cantrell, C. D. Multiple-vibrational-mode model for fiber-optic Raman gain spectrum and response function. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19, 2886 (2002).

Tsuchihashi, S. & Kawamoto, Y. Properties and structure of glasses in the system As-S. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 5, 286–305 (1971).

Saad, M. et al. Indium Fluoride Glass Fibers for Mid-Infrared applications. In Workshop on Specialty Optical Fibers and Their Applications WW4A.3 (OSA, Hong Kong, 2015).

Evrard, M. et al. TeO 2 -ZnO-La 2 O 3 tellurite glass purification for mid-infrared optical fibers manufacturing. Opt. Mater. Express 12, 136 (2022).

Jiang, X., Lousteau, J., Richards, B. & Jha, A. Investigation on germanium oxide-based glasses for infrared optical fibre development. Opt. Mater. 31, 1701–1706 (2009).

Price, J. H. V. et al. Mid-IR Supercontinuum Generation From Nonsilica Microstructured Optical Fibers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 13, 738–749 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (IRCPJ 469414-18, ALLRP 588222-23); Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Nature et Technologies (CO25665); Canada Foundation for Innovation (5180).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed and led by T.G., and supervised by R.V. and Y.M. The glass fabrications were carried out by T.G. The glass properties were measured by T.G., A.D., E.S., and M.B., and supervised by E.F. and T.C. The fibers were drawn by S.M. and P.L. The direct laser writing was performed by A.D., and supervised by T.G., J.L., and R.V. The supercontinuum experiments were conducted by A.D., E.S., and J.L., and supervised by B.K., J.L., F.S., and R.V. The supercontinuum simulations were conducted by E.S. and supervised by B.K., F.S., and R.V. The manuscript was written by T.G., A.D., and E.S. and reviewed by all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guérineau, T., Dupont, A., Serrano, E. et al. Tantalo-gallate glass as robust nonlinear medium for mid-infrared photonics. Commun Mater 6, 199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00930-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00930-z