Abstract

Halide perovskite nanocrystals are highly attractive luminescent materials for next-generation displays due to their outstanding properties, including high photoluminescence quantum yield, excellent color purity, tunable emission wavelengths, and cost-effective solution processability. Their exceptional color purity enables full coverage of the ultra-wide color gamut required for vivid visual experiences in modern display technologies. Light-emitting diodes based on perovskite nanocrystal films have demonstrated external quantum efficiencies exceeding 25%. However, significant performance degradation arises during the pixelation process, a critical step in fabricating high-resolution display devices. Here, we review recent progress and ongoing challenges in advancing perovskite nanocrystal light-emitting diodes for high-resolution applications. We highlight state-of-the-art patterning techniques, stability enhancement strategies, and fundamental causes of efficiency loss, together with progress in integrating devices with thin-film transistor circuits for active-matrix displays. Finally, we discuss future perspectives and key challenges for advancing perovskite nanocrystal light-emitting diodes towards next-generation high-resolution display technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal halide perovskites have emerged as a highly promising class of optoelectronic materials, owing to their exceptional properties such as high absorption coefficients, long carrier diffusion lengths, and tunable bandgaps, enabling diverse applications in photovoltaics, photodetectors, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs)1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In particular, perovskite LEDs with narrow emission bandwidths and high color purity are regarded as ideal candidates for next-generation high-resolution displays1,8,9,10,11. Recent advances in bulk perovskite thin-film LEDs have led to significant improvements in efficiency and operational stability12,13,14. However, pixelation of bulk perovskite emissive layers remains a critical challenge due to the limited patterning compatibility of these labile ionic materials. Although pixel definition can be achieved through device architecture (such as pixelated electrodes or isolation layers), crosstalk between neighboring pixels becomes increasingly severe at high resolutions, undermining color uniformity and device performance15. As an alternative, colloidal perovskite nanocrystals (PeNCs) offer unique advantages, including higher exciton binding energy and near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY)16,17. Their surface-capping ligands provide excellent colloidal stability and solution processability, enabling a wide range of pixelation strategies such as inkjet printing18, photolithography19, photopatterning20, transfer printing21, and laser printing22. These features make PeNCs particularly attractive for patternable emissive layers in ultra-high-resolution display technologies.

In recent years, PeNC-based electroluminescent LEDs have achieved remarkable progress, with external quantum efficiency (EQE) exceeding 25% for green (G) and red (R) monochromatic emissions, and reaching 20% for blue (B) emissions23,24,25,26. These efficiency levels are comparable to those of organic LEDs (OLEDs) and colloidal CdSe or InP quantum dot LEDs (QLEDs). Building on these performance advantages and their compatibility with thin-film transistor (TFT) backplanes in active-matrix (AM) configurations, PeNCs have become a central focus in the development of high-resolution, pixelated display systems1,27. The ability to support independent pixel-level control makes them particularly suitable for energy-efficient, next-generation display applications such as near-eye augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) devices28,29,30,31,32. To contextualize their strengths and limitations, we introduce a comparative hexagonal radar chart (Fig. 1a) that benchmarks pixelated PeNC LEDs against QLEDs and OLEDs across six key metrics: EQE, operational stability, resolution (PPI), color purity, source material cost, and patterning compatibility. Compared with QLEDs or OLEDs, pixelated PeNC LEDs demonstrate superior color purity (full width at half maximum (FWHM) < 25 nm), along with competitive EQE performance compared with QLEDs and OLEDs, and PeNC LEDs benefit from low source material cost and scalable patterning routes. The excellent color purity and cost-effective solution processability position PeNCs as a compelling alternative for next-generation, highly vivid and cost-efficient displays. However, their operational stability still lags behind mature OLED technologies. While these attributes make PeNCs attractive for high-resolution display applications, realizing their full potential requires overcoming several intrinsic material and device-level limitations.

a Comparative radar chart benchmarking pixelated PeNC LEDs, QLEDs, and OLEDs across six key performance metrics relevant to high-resolution display applications: patterning compatibility, external quantum efficiency (EQE), operational stability, resolution, color purity, and source material cost. Data are sourced from references22,59,106,107,108,109,110,111. b Schematic diagram of the self-emissive display LED device structure. c Illustrative diagram of four methods for preparing PeNC arrays. d Schematic diagram addressing the efficiency drop caused by active layer pixelation and improving device stability. e Device structure diagram of Active-Matrix technology integrated with PeNC LEDs.

Among these, a critical challenge lies in achieving high-resolution PeNC LED arrays, as reducing pixel sizes demands exceptional fabrication precision and material robustness29,33,34. The ionic nature of PeNCs makes both their lattice structure and the binding of surface ligands intrinsically labile, making them highly sensitive to processing conditions. Conventional patterning techniques can induce structural defects, surface degradation, and ligand loss, all of which diminish luminescence efficiency. In addition, pixelation increases sidewall exposure, introducing new interfaces that serve as trap sites and contribute to non-radiative recombination. The discontinuous architecture of pixelated arrays also hampers photon recycling and reduces light extraction efficiency, resulting in lower EQEs compared to unpatterned thin-film counterparts. To address these challenges, it is essential to develop patterning and post-processing strategies that minimize structural damage and maintain high optoelectronic quality at pixel-level resolution28,35,36.

In this review, we provide a comprehensive overview of recent progress and key challenges associated with high-resolution PeNC-based LEDs for advanced display applications (Fig. 1b). We begin by examining five key fabrication methods for PeNC arrays: inkjet printing, transfer printing, photolithography, direct photopatterning, and laser printing, emphasizing their capabilities, limitations, and compatibility with PeNC materials (Fig. 1c)27,37,38. The discussion then addresses strategies to improve PeNC stability through nanocrystal engineering and to mitigate pixelation-induced efficiency losses (Fig. 1d). We compare the EQE of pixelated and unpatterned thin-film PeNC LEDs across RGB classifications, providing insight into the performance gap and its origins. Finally, we highlight recent efforts to integrate PeNC LEDs with AM thin-film transistor backplanes (Fig. 1e), offering a forward-looking perspective on their potential in next-generation near-eye and high-resolution displays.

Patterning techniques toward pixelated PeNC LEDs

The display industry encompasses a wide range of applications, from large-screen televisions to compact devices such as smartphones and wearable technologies. As viewing distances decrease from far-field to near-eye levels, achieving high resolution becomes essential for maintaining image clarity and mitigating pixelation effects33,34. Resolution is typically quantified in PPI, though commercial display devices often specify it in terms of horizontal and vertical pixel counts (e.g., 7680 × 4320 for 8 K or 3840 × 2160 for 4 K displays). The relationship between PPI and pixel dimensions can be expressed by the following formula:

where Wp and Hp represent the numbers of pixels along the width and height of the display, and W and H denote the physical width and height of the display(in inches)35. This metric reflects the pixel density, which varies depending on display size and viewing distance, thereby directly affecting image clarity. Higher resolution not only yield sharper and more vivid images by increasing pixel density but also substantially enhances the overall visual experience, particularly in applications requiring close-up viewing39. The development of precise and scalable patterning techniques for PeNC LEDs is therefore essential to fully realize their potential in high-resolution display technologies.

Inkjet printing

Inkjet printing is a non-contact, scalable, and cost-effective technique for large-area, mask-free fabrication of display devices39,40,41. Its precise material deposition makes it particularly advantageous for patterning high-resolution pixel arrays in RGB PeNC LEDs42,43,44. The process involves three steps: (1) synthesizing high-quality inks with excellent dispersibility, stability, and rheological properties; (2) optimizing printing parameters and nozzle design to ensure precision and uniformity; and (3) Refining pixel structures through techniques such as plasma etching to improve morphology and optoelectronic performance18,45,46,47.

In the first step, early studies showed that stabilizing PeNC inks by introducing additional oleylamine (OAm) ligands during purification improved ink PLQY from 13.3% to 63.2%. By optimizing the octane-to-dodecane solvent ratio to achieve suitable viscosity, FA₀.₃Cs₀.₃PbBr₃ NC LEDs were fabricated with a pixel density of 120 PPI48. Further advancements introduced alkynoic acid ligands in combination with an activation agent. The high viscosity of the activation agent reduced ligand desorption, while UV-triggered alkyne–alkyne crosslinking generated carbonyl radicals that tightly bridged to the PeNC surface, enabling 1 μm dot-patterned green and white PeNC LEDs with excellent stability and performance49. In addition to ink formulation, optimizing printing parameters and pixel structures is essential for achieving high-resolution, uniform PeNC LED arrays50. Critical parameters, such as droplet volume, jetting frequency, substrate temperature, and nozzle–substrate distance, affect droplet morphology, deposition accuracy, and pixel resolution27,51. Careful tuning of these factors suppresses satellite droplet formation, controls spreading behavior, and ensures pattern fidelity. Substrate engineering, including pre-patterned hydrophobic barriers or localized plasma or UV–ozone treatments, helps confine inks within designated areas, thereby reducing interpixel crosstalk52. Post-printing treatments like plasma etching further refine pixel edges and remove excess organics, leading to improved charge transfer and minimized nonradiative losses.

Another major issue in inkjet printing is the coffee-ring effect, a drying-induced phenomenon where solutes accumulate at the droplet edges, resulting in ring-like deposition and reduced uniformity46. The final morphology of the dried droplet is governed by the interplay between surface tension and evaporative flux46,53. Increasing substrate hydrophobicity raises the contact angle, reduces spreading, and promotes a near-spherical droplet shape. This geometry favors internal Marangoni flow, which counteracts capillary-driven outward flow and reduces nanocrystal accumulation at the edges (Fig. 2a)54,55. For example, introducing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) increased the contact angle from 5.9° to 41°, thereby lowering surface tension and enabling more uniform deposition46. This strategy enabled the fabrication of RGB PeNC LED arrays with pixel sizes as small as 45 μm (Fig. 2b)45.

a–c Inkjet printing. a Schematic diagram of the effects of surface tension and evaporation flux on droplet shape and the coffee-ring effect. b Comparison of PeNC arrays printed on the hole transport layer versus PeNC arrays printed after surface modification with SDS45. Adapted from ref. 45. with permission. Copyright (2022) Wiley-VCH. c Schematic illustrations of capillary flow and Maragoni flow effect (top) and comparison of the uniformity of self-assembled PeNC thin films in ternary and binary solvent systems (bottom)18. The abbreviation b.p. stands for boiling point. The bottom figure was reproduced wtih permission from ref. 18. Copyright (2022) Wiley-VCH. d–e Transfer printing. d Schematic of the transfer printing process. e Fluorescence microscopic images of the pixelated RGB PeNC patterns deposited by transfer printing21. Reproduced with permission from ref. 21. Copyright (2022) The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. f–g Photolithography. f Schematic diagram of the photolithography process after PEI modification19. Adapted from ref. 19. with permission. Copyright (2023) Wiley-VCH. g Schematics of the addition of an insulating layer inside the device to promote electron-hole recombination in the active layer and reduce internal leakage currents processes. h The fluorescence microscopy images of PeNC patterns and the Current density–Luminance–Voltage curves of the LED devices19. Reproduced with perimission from ref. 19. Copyright (2023) Wiley-VCH.

Solvent engineering offers an effective route to suppress evaporation-induced non-uniformities. Rapid edge evaporation typically induces outward capillary flow, which can be counteracted by introducing a small amount of high-boiling-point solvent with higher surface tension to generate inward Marangoni flow54. Additionally, incorporating a lower-boiling-point component helps balance the evaporation rate and flow dynamics. Therefore, the use of mixed high- and low-boiling-point solvents is an effective strategy for suppressing the coffee-ring effect (Fig. 2c, top panel)29,48,54,55, for instance, a ternary solvent mixture of low-boiling n-nonane with high-boiling n-tridecane and naphthene facilitated PeNC self-assembly into uniform films (Fig. 2c, lower panel), resulting in printed PeNC LEDs with a peak EQE of 8.54% and an operational T50 (time for 50% efficiency drops) of 63.84 min18.

Inkjet printing continues to evolve as a promising technique for pixelated PeNC LEDs. Its potential for high resolution, precision control, and compatibility with large-area, low-cost processing makes it a compelling pathway toward next-generation display technologies.

Transfer printing

Transfer printing is a high-resolution technique capable of creating defect-free PeNC LED patterns. The process involves lifting uniform PeNC films from a sacrificial substrate using a viscoelastic stamp, followed by precise alignment and transfer onto the target substrate under controlled pressure (Fig. 2d)21,56,57. Despite its advantages, the application of transfer printing to PeNCs remains limited due to specific challenges. The weak interaction energy between PeNCs in thin films often leads to internal cracking or detachment during the transfer process, significantly compromising pixel quality58. Furthermore, achieving high-resolution, multicolor PeNC displays requires sub-micron alignment and precise control to avoid interlayer mixing of different-colored PeNC layers during sequential transfers. Such mixing can cause current leakage and deteriorate device performance, posing critical challenges for the reliable patterning of PeNC LEDs52.

To overcome these issues, an innovative double-layer transfer printing approach has been developed. This method incorporates an electron transport material 2,2’,2”-(1,3,5-Benzinetriyl)-tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi) layer to facilitate the efficient transfer of PeNC/TPBi stacks using a viscoelastic Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp. The low adhesion energy between the TPBi layer and the PDMS stamp ensures easy delamination, while the TPBi layer uniformly distributes stress across the PeNC layer, preventing internal cracking. This approach enables precise PeNC patterning onto various charge transport layers critical for PeLED fabrication without causing physical or chemical damage to the PeNC layer. Using this technique, high-resolution green, red, and blue PeNC LEDs with a resolution of 2550 PPI were successfully fabricated (Fig. 2e). Additionally, ultrathin, skin-attachable PeNC LEDs with a total thickness of 1.3 μm were demonstrated21.

In addition, the introduction of a honeycomb-insulating poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) film has been proven effective in further enhancing the transfer process. The PMMA layer acts as an insulating barrier, preventing direct contact between the electron and hole transport layers (HTLs). This reduces internal leakage currents and enables the fabrication of high-resolution patterned PeNC LEDs with a resolution of 9072 PPI, among the highest reported to date59.

While transfer printing holds significant promise for high-resolution PeNC LED fabrication, overcoming intrinsic material limitations and ensuring reliable multicolor alignment remain critical to unlocking its full potential for next-generation full-color displays.

Photolithography of PeNCs via photoresist

Photolithography is a mature, high-throughput patterning technique capable of defining nanometer-scale features with exceptional resolution and scalability35,60,61, making it attractive for display applications based on PeNCs. In a typical photolithography process, PeNC films are first spin-coated to form uniform layers, followed by the application of a photoresist (PR) layer. The PR layer is exposed to UV light through a patterned mask, followed by development and etching to define the desired pattern. However, the ionic nature and surface sensitivity of PeNCs present challenges when using standard PRs and solvents. These processes often degrade PeNCs35,42, causing significant losses in PLQY and structural integrity. Additionally, the solvents used during development and lift-off steps can dissolve or destabilize ionic perovskite layers, limiting the applicability of conventional photolithography for PeNC patterning35,37.

To address these limitations, modified photolithography processes have been developed, focusing on orthogonal solvents compatible with PeNC films. These solvents do not dissolve PeNCs or alter their surface composition and photophysical properties, ensuring the integrity of the nanocrystals during patterning35,42. A novel approach combining photolithography with electrostatic force-induced deposition (EF-ID) has also been proven effective in fabricating PeNC patterns. In this method, self-assembly is used to deposit a hydrophobic and insulating layer of perfluoro-octyl trichlorosilane on PR-patterned substrates. This fluorosilane layer serves as a template for further nanocrystal assembly. The PR is then replaced with hydrophilic polyethylenimine (PEI), which interacts electrostatically with negatively charged CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals. This process enables the formation of precise PeNC patterns while preventing nanocrystal degradation associated with traditional photolithography (Fig. 2f)19. The fluorosilane layer between patterned pixels acts as an insulating barrier, allowing electrons and holes to recombine within the PeNC layer, thereby reducing internal leakage currents (Fig. 2g). This technique has enabled the fabrication of high-resolution PeNC devices with pixel densities reaching 3031 PPI and brightness of 2943 cd m−2 (Fig. 2h)19.

Photolithography, with these advancements, provides a robust pathway for achieving high-resolution patterning of PeNCs. Its potential for scalability and precision, combined with modifications that enhance compatibility with PeNC materials, positions it as a vital tool in the development of next-generation display technologies. However, the use of PR and the associated development processes can still induce defects in PeNCs, compromising their structural and optoelectronic properties. To address this issue, the incorporation of a dense ZnO electron transport layer (ETL) via atomic layer deposition (ALD) has emerged as a promising approach62. This ZnO layer not only protects the underlying PeNCs from damage during the PR and development processes but also functions as an effective ETL in LED device fabrication. Such a strategy enhances the compatibility of photolithography with PeNC materials and holds significant potential for enabling the development of stable and high-resolution PeNC-based LEDs.

Direct photopatterning

Direct photopatterning is an emerging technique that simplifies the patterning process by eliminating the need for PR. Instead, it employs photo-crosslinker or photosensitive ligands that interact directly with the surface of PeNCs20,63. Depending on the ligand chemistry, light-induced crosslinking or decomposition reduces the dispersibility of PeNCs, thereby enabling spatial patterning. The unexposed regions are subsequently removed using mother solvents, avoiding the damage commonly caused by polar solvents in conventional photolithography. This improved solvent-resistant approach has gained significant attention for its ability to maintain the structural and optoelectronic integrity of PeNCs21,63,64. Here, we classify direct photopatterning strategies into three categories: photocleavable-ligand patterning, self-crosslinking-ligand patterning, and crosslinker-assisted photopatterning.

In a representative example of photocleavable-ligand patterning, a photosensitive oxime sulfonate ester (–C = N–OSO2–) was designed to undergo light-induced cleavage, forming sulfonate-anchored PeNC surfaces to prevent re-dispersion. The ligand decomposition process introduces a large number of defects on the PeNC surface, thereby reducing the luminescence efficiency. Surface treatment with PbBr2/ octanoic acid/butylammonium introduced short butylammonium octanoate ligands, enhancing surface passivation and film morphology (Fig. 3a). The resulting PeNC films exhibited a PLQY of 79%63.

a Schematic illustration of the mechanism of direct photolithography process on the CsPbX3 NCs surface with photosensitive oxime sulfonate ester63. Adapted with permission from ref. 63. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society. b Schematic diagram of the self-crosslinking mechanism of organic molecular ligands containing azide groups and C = C bonds under UV irradiation65,66,67. c Structural schematic illustration of the photopolymerization mechanisms for DOPPLCER methods, utilizing bisFPA molecules as photoactivators, the carbene-modified version of DOPPLCER, and ODT/DDT respectively20,68,69. The functional groups highlighted with red circles are those involved in the photo-crosslinking reaction. Adapted from ref. 20 with permission. Copyright (2024) American Chemical Society. d Schematic illustration of the mechanism of laser printing process22. e Comparison of five kinds of patterning techniques for high-resolution PeNC LEDs in terms of edge definition, PeNC compatibility, resolution, EQE, and scalability.

In self-crosslinking strategies, azide ligands containing carboxyl and azide groups serve dual roles as surface stabilizers and photo-crosslinkers. Upon UV exposure, these ligands form covalent networks, improving solvent resistance and surface passivation (Fig. 3b)65. Similarly, C = C-containing molecules such as 9-decenoic acid66 and 7,7′-(1,4-phenylene)bis(6-(acryloyloxy)heptanoic acid) (PBAD)67 undergo self-polymerization, facilitating robust pattern formation.

Crosslinker-assisted strategies, such as DOPPLCER (direct optical patterning via photo-ligand crosslinking and exchange reaction), employ bis(fluorophenyl azide) (bisFPA) ligands that decompose under UV light to generate nitrene radicals. These radicals undergo C–H insertion into native ligands, forming stable C–N bonds and establishing a crosslinked PeNC network (Fig. 3c)68. Post-treatment with PbBr2 improved PLQY from 38% to 76% and enabled pixelated LEDs with EQE up to 6.8% and brightness of 20,000 cd/m2. Building on this concept, a carbene-based crosslinker was introduced to overcome the limited selectivity and potential lattice damage associated with nitrene chemistry. The carbene-mediated reaction proceeds more gently and with higher specificity, thereby preserving the intrinsic PLQY of PeNCs while providing stronger and more controllable crosslinking. This advancement enabled high-resolution patterning (~4000 PPI)20 and markedly improved device performance, achieving a high EQE of 16% and brightness of 64,726 cd/m2. Moreover, this approach supports multicolor patterning through repeated cycles of film deposition, UV crosslinking, and development, and is compatible with flexible substrates—an important step toward full-color PeNC displays.

Despite these advances, direct photopatterning may degrade PeNCs through UV-induced defect formation and charge-blocking from insulating long-chain ligands or crosslinker. To mitigate the detrimental effects of UV-induced defects and insulating long-chain ligands, Maeng et al. developed a dual-strategy direct photocatalytic patterning method that combines low-dose thiol–ene crosslinking with post-patterning film-state ligand exchange (FLE)69. In this process, linear dithiols such as 1,8-octanedithiol (ODT) and 1,10-decanedithiol (DDT) serve as photocrosslinkers (Fig. 3c). Upon UV irradiation, these dithiols undergo thiol–ene click reactions with alkene-containing surface ligands (e.g., oleyl groups), forming C–S covalent bonds that interconnect neighboring ligands and establish a mechanically robust crosslinked network on the PeNC surface. Following crosslinking, a FLE step is conducted by treating the patterned PeNC films with short-chain ammonium halides such as butylammonium bromide (BABr) in solution. This post-patterning ligand exchange replaces insulating long-chain ligands with compact, ionic ones, which reduces steric hindrance and enhances charge injection and transport. Notably, this sequential strategy improves photoluminescence, facilitates efficient charge conduction, and enables RGB patterning at resolutions exceeding 10,000 PPI. The resulting PeNC LEDs achieved EQEs of 14.7% (green) and 13.1% (red)—among the highest values reported for direct photopatterned devices. Future progress will rely on further improving nanocrystal stability through core–shell designs and UV-resistant ligand systems70,71,72. Moreover, reducing the use or improving the conductivity of photocrosslinkers can suppress surface traps and enhance carrier mobility73. Continued innovation in these directions will enable the fabrication of high-resolution, stable, and efficient PeNC patterns, establishing direct photopatterning as a powerful strategy for next-generation AR/VR and microdisplay technologies.

Laser printing

Laser printing has emerged as a promising mask-free and solvent-free direct patterning approach for pixelating PeNC films, offering notable advantages over conventional photolithographic techniques22,37. Unlike photoresist-based photolithography, which involves multiple wet-processing steps and often compromises material integrity, this approach employs a focused laser to locally modify PeNC films through photothermal decomposition. Upon irradiation, the laser triggers ligand detachment and lattice collapse of the perovskite in the exposed regions, leading to emission quenching and the in situ formation of CsOx and PbOx-rich insulating domains (Fig. 3d). These oxide barriers act as interpixel spacers that effectively confine charge transport to the emissive areas and suppress lateral leakage currents. In previous patterning schemes (e.g. inkjet printing, transfer printing, photolithography and direct photopatterning), PeNC pixels are spatially defined with physical gaps between adjacent emissive domains, necessitating additional deposition of insulating PR or dielectric materials to prevent direct contact between charge transport layers and the underlying substrate, which would otherwise cause undesired leakage or parasitic emission. In contrast, the laser-induced approach intrinsically forms insulating boundaries during the pixelation step, thereby eliminating the need for secondary photopatterning or additional insulation steps, simplifying processing and enhancing device integrity.

Recent work by Ma et al. demonstrated this principle using cesium-based inorganic PeNCs22. By modulating laser power, scanning speed, and focal depth, they achieved in situ patterned red, green, and blue pixel arrays with pixel densities up to 5000 PPI, reporting record-high EQEs of 17.2%, 21.0%, and 6.6%, respectively, for R/G/B devices. The oxide layers not only function as robust insulating boundaries, but also enhance device performance by reducing leakage currents and improving carrier confinement.

Despite above advantages, laser printing currently faces fundamental limitations in achieving full-color RGB integration within a single substrate. In typical RGB display architectures, different emissive materials must be sequentially deposited and patterned into spatially separated subpixels. However, in the laser printing process, the entire substrate is first uniformly coated with one PeNC composition before pixelation. Laser exposure renders the irradiated regions electrically inactive and physically insulated. As a result, these regions are no longer accessible for subsequent deposition of different color PeNCs, since the insulating oxide formed blocks charge injection from transport layers. Consequently, this method is inherently incompatible with sequential multicolor pixelation, a critical requirement for full-color microdisplay applications. To address the incompatibility of laser-induced patterning with in-plane RGB integration, full-color display architectures can instead adopt vertically stacked monochromatic PeNC LEDs, each fabricated on separate substrates and later integrated through optical-layer engineering—including transparent electrodes, dielectric spacers, and color filters—to enable efficient light extraction and color mixing without lateral patterning conflicts74. This modular stacking approach is fully compatible with laser-defined single-color pixelation, offering a scalable path toward high-resolution full-color PeNC microdisplays.

Comparison of patterning techniques

Each patterning technique achieves a distinct trade-off among edge definition, PeNC compatibility, resolution, device performance, and scalability (Fig. 3e), which collectively determine its suitability for high-resolution PeNC LED fabrication. Inkjet printing offers high scalability and good material compatibility, owing to its low-cost digital control and ligand-friendly processing conditions. However, its resolution and edge fidelity are limited by fluidic instabilities, such as the coffee-ring effect. For ultrahigh-resolution applications, electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing can be employed, but its requirement for high electric fields and polar solvents poses compatibility challenges for PeNCs. Transfer printing enables ultrahigh resolution and excellent edge sharpness (up to 9072 PPI), and its PeNC compatibility can be improved using buffer layers. Nonetheless, its low scalability, stemming from complex multistep alignment processes, limits its scalable deployment. Photolithography leverages mature semiconductor fabrication workflows to provide the best resolution and edge precision. However, the use of polar solvents and photoresists during the process often undermines the ionic stability of PeNCs. Direct photopatterning achieves a strong balance across all key metrics by employing crosslinking agents or photosensitive ligands, delivering high PeNC compatibility, simplified fabrication, and excellent device performance (EQE up to 16%). Laser printing offers the highest resolution and edge confinement by forming in situ insulating oxide boundaries during photothermal pixelation, enabling record-high EQEs exceeding 21%. Nevertheless, its current limitation to single-material processing hinders planar RGB integration. Although no single method fully satisfies all performance criteria, their complementary advantages offer a versatile toolbox for the scalable fabrication of high-resolution, multicolor PeNC displays. Among them, direct photopatterning stands out for its well-balanced performance across resolution, material compatibility, and device efficiency, making it particularly promising for scalable fabrication of multicolor PeNC microdisplays.

Strategies to enhance stability of PeNC LEDs

Intrinsic material instabilities, including a soft ionic lattice and weakly bound ligands, lead to ligand detachment, ionic migration, and defect formation. Combined with external stressors such as moisture, oxygen, light, and thermal fluctuations, these factors contribute to the rapid degradation of efficiency and operational lifetime in PeNC LEDs (Fig. 4a). Additionally, poor stability exacerbates pixelation-induced defects in PeNC arrays, significantly limiting the key performance parameters such as EQE and luminance. Therefore, stability remains one of the most critical challenges in advancing PeNC LEDs for commercial applications. To address these issues, researchers have developed three primary strategies: surface treatment13,23,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83, ion doping16,84,85, and core/shell structure engineering86,87. These strategies collectively tackle the fundamental causes of instability, offering a complementary approach to improving the stability and efficiency of PeNC LEDs.

a Instabilities arise from ligand detachment, surface defects, ion migration, and environmental stress (light, moisture, oxygen, and heat), leading to degradation. b–d Mitigation strategies include surface treatment with strong binding ligands to improve passivation (b)13, ion doping to stabilize the lattice structure (c)16, and core/shell engineering (d) for enhanced surface protection. Adapted from ref. 13. and ref. 16. with permission. Copyright (2021, 2022) Springer Nature.

Surface treatment

Surface treatment is a critical strategy for stabilizing PeNC LEDs by mitigating surface defects and enhancing resistance to environmental stressors such as moisture, oxygen, and ion migration88. Due to the ionic nature of PeNCs, ligand binding is inherently weak, resulting in rapid desorption under polar processing or operating conditions and the subsequent formation of surface traps, non-radiative recombination centers, and overall device instability. Traditional long-chain ligands, such as oleic acid (OA) and OAm, provide initial colloidal stability but rely on weak van der Waals interactions with the nanocrystal surface, making them ineffective under operational conditions.

To address these limitations, researchers have explored surface ion treatment as a method to stabilize PeNCs by modifying surface chemistry and passivating defects. Gao et al. introduced a tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate (TBABF4) treatment, which effectively passivated halide vacancies in perovskite nanocrystals by replacing weakly bound ligands and reinforcing the crystal lattice77. Compared to untreated devices, PeNC LEDs with TBABF4-treated films exhibited significantly reduced ion migration and improved charge transport, leading to enhanced operational stability and more uniform electroluminescence performance.

In addition, ligand engineering has been employed to further stabilize PeNC surfaces89,90,91,92,93,94. Kim et al. developed an in situ passivation strategy using benzylphosphonic acid (BPA), which forms a robust core/shell structure around PeNCs13. BPA binds covalently to undercoordinated Pb²⁺ sites, reducing defect densities and suppressing non-radiative recombination. This BPA passivation not only improves luminescence efficiency but also enhances charge carrier confinement, leading to a T50 lifetime of 520 h at 1000 cd/m2. Extrapolated to 100 cd/m2, the devices achieved an estimated T50 exceeding 30,000 h, marking a substantial breakthrough in PeLED longevity (Fig. 4b). Also, Hassan et al. demonstrated that ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), a multidentate ligand, could effectively mitigate surface defects and suppress halide segregation in mixed-halide perovskites75. This method resulted in significantly extended operational lifetimes by stabilizing the bandgap and minimizing recombination pathways.

Moreover, surface treatment has also been reported to induce long-range ordering in PeNC films, enhancing both structural stability and optoelectronic properties in PeNC LEDs. For instance, a chemically reactive agent, bromotrimethylsilane, generates a strong acid in situ, selectively dissolving smaller PeNCs to regulate size while effectively removing less conductive ligands. This process results in compact, uniform, and defect-free films. The long-range-ordered CsPb(Br/I)₃ PeNC film significantly suppresses defect formation and halide migration, leading to improved thermal stability in the device81. This structured arrangement facilitates efficient charge transport, enabling PeNC LEDs to achieve a T90 lifetime of 780 h at 100 cd/m2. These results highlight how the integration of surface ion treatment, ligand engineering, and structural ordering provides a strong foundation for enhancing the intrinsic stability and reliability of PeNC LEDs under demanding operational conditions.

Ion doping

Because the instability of PeNCs originates from their soft ionic lattice, ionic doping strategies offer a powerful approach to stabilizing PeNC by enhancing their lattice and electronic properties. These techniques target intrinsic instabilities and enhance the structural, optical, and electronic characteristics of PeNCs, significantly improving their performance and operational lifetimes95.

Guanidinium (GA) doping has proven effective in stabilizing surface defects by enhancing hydrogen bonding with halide ions, which suppresses non-radiative recombination and improves lattice symmetry (Fig. 4c)16. These interactions improve defect passivation and optical stability while enhancing charge carrier confinement. Devices incorporating GA-doped PeNCs demonstrated remarkable operational lifetimes, achieving an eightfold increase in stability compared to untreated counterparts under continuous operation. Metal ion doping has also shown significant potential in addressing lattice strain and defect density. For instance, the incorporation of trace cadmium ions (Cd²⁺) has been shown to improve both the stability and efficiency of PeNCs84. Cd²⁺ doping introduces subtle lattice distortions that increase exciton binding energy and stabilize the perovskite crystal structure. These structural enhancements translated into significant improvements in device lifetimes, with Cd²⁺-doped LEDs exhibiting more than a threefold increase in half-lifetime compared to undoped devices under identical conditions. Similarly, zirconium ion (Zr⁴⁺) doping combined with in-situ potassium thiocyanate (KSCN) passivation provides a complementary perspective on doping strategies85. Zr⁴⁺ ions increase the formation energy of CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals, effectively mitigating halide migration and enhancing structural stability. Concurrently, KSCN passivation addresses surface trap states, improving thermal and environmental stability. This dual approach yielded devices with operational half-lifetimes exceeding 6 h at 1000 cd/m², more than doubling the stability compared to conventional designs. By tailoring the lattice and electronic properties of PeNCs, doping strategies provide a versatile and effective means of enhancing both the stability and performance of LEDs. These advancements highlight the potential of doping as a key enabler for the commercialization of next-generation PeNC LED technologies.

Core/shell structure

Core/shell structure engineering has recently gained attention as an effective method for enhancing the stability and efficiency of PeNC LEDs (Fig. 4d). By encapsulating PeNCs within a robust shell material, this strategy addresses surface defects, suppresses ion migration, and improves environmental resistance, all critical factors for achieving long-term device stability.

Zhang et al. demonstrated a significant advancement by capping CsPbI3 nanocrystals with PbS to form a coherent core/shell structure86. The PbS shell provided a robust barrier against environmental degradation while effectively passivating surface defects. This encapsulation strategy significantly improved the operational stability of PeNC LEDs by mitigating ion migration and preventing phase transitions, both of which are critical failure mechanisms under continuous operation. As a result, PbS-capped PeNC LEDs exhibited remarkable operational stability, maintaining 90% of their initial electroluminescence intensity after 90 min of operation. In contrast, unencapsulated devices showed a rapid decline, retaining only 48% of their initial luminance after 10 min, highlighting the substantial stability improvement enabled by the PbS shell.

In another study, Hong et al. developed deep-blue-emitting PeNC LEDs by hermetically sealing CsPb(Br/Cl)3 nanocrystals with epitaxial ZnS shells87. The ZnS shell acted as both a physical barrier and an electronic passivation layer, protecting the perovskite core from environmental factors and suppressing interparticle ion migration. The epitaxial growth of the ZnS shell minimized lattice mismatch and maintained the structural integrity of the perovskite core, ensuring efficient charge injection and transport. This core/shell structure significantly reduced non-radiative recombination and improved charge carrier confinement, leading to enhanced device performance. Remarkably, even in an unencapsulated state, the devices maintained a T50 operational lifetime of 1192 s in air, significantly outperforming conventional PeNC LEDs, which rapidly degrade due to ion migration and phase instability. This resilience against environmental degradation suggests that core/shell structures can facilitate high-resolution patterning techniques by improving material robustness against processing-induced damage.

The development of surface treatment, ionic doping, and core/shell structures collectively provides a robust foundation for addressing the stability challenges of PeNC LEDs. By leveraging these strategies, researchers have demonstrated significant improvements in operational lifetimes, photostability, and device efficiency. Enhanced stability minimizes material degradation during patterning processes, ensuring uniformity and reproducibility, which are critical for achieving precise and reliable high-resolution pixelated PeNC LED displays. Future research should explore the synergistic integration of these strategies to further enhance device reliability, scalability, and compatibility with industrial patterning techniques. Such efforts will play a pivotal role in advancing PeNC LEDs toward commercialization and next-generation display technologies.

In addition, the effect of miniaturization on device stability should be taken into consideration. A recent study on bulk perovskite LEDs showed that reducing the pixel size can actually enhance operational stability under constant current density15, primarily due to three synergistic mechanisms. First, the use of a localized contact architecture, where a SiO2 insulating layer defines the active area and separates the electrodes from rough pixel edges, effectively suppresses edge-induced non-radiative recombination and electric field inhomogeneity, thereby mitigating thermal stress and material degradation at the boundaries. Second, downsizing the pixel area facilitates the growth of perovskite films with larger grain sizes and improved crystallinity, resulting in fewer grain boundaries, lower defect density, and more efficient charge transport and radiative recombination. Third, under constant current density, smaller pixels inherently carry less total current and consume less power, reducing Joule heating and slowing heat-induced material deterioration and electrode aging. The first two mechanisms are particularly relevant to bulk perovskite materials, while the third is generally applicable to all types of miniaturized LEDs. In contrast, PeNCs benefit more from surface passivation, but still gain thermal advantages from miniaturization. Future integration of miniaturization strategies with chemical and structural stabilization methods will be key to unlocking robust, high-resolution PeNC LED displays.

Efficiency gap between pixelated LEDs and thin-film LEDs

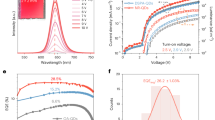

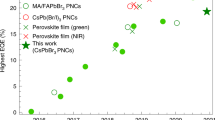

In recent years, PeNC LEDs have made significant advancements in device efficiency across the red, green, and blue spectral regions. EQEs have surpassed 20%, with reported peak values reaching 28.5% for red23, 30.2% for green24, and 26.4% for blue emission25 (Fig. 5a). These developments have brought PeNC LED performance closer to that of commercial OLEDs and inorganic QLEDs26. However, a substantial efficiency gap remains between pixelated PeNC LEDs and their continuous thin-film counterparts. The performance and resolution parameters of pixelated PeNC LED devices are listed in Table 1. The most recent maximum EQE for pixelated PeNC LEDs is ~16%20, a value comparable to the EQE of thin-film PeNC LEDs reported 6 years ago96. As shown in Fig. 5a, the progress of pixelated PeNC LEDs has been significantly slower than that of non-patterned devices, and the EQEs tend to decline as PPI increases for RGB pixelated devices (Fig. 5b).

a Statistical diagram comparing the EQE over time for Pixelated PeNC LEDs and PeNC thin-film LEDs with red, green, and blue emissions. b EQE vs resolution in pixelated PeNC LEDs. c Plot illustrating the relationship between PPI and the fold increase in total sidewall area (SSA) in pixelated PeNC LEDs. As resolution increases, the SSA grows proportionally.

This efficiency disparity arises from three primary factors: First, patterning induces structural instability in PeNCs, leading to the degradation of their optoelectronic properties; second, pixelation disrupts photon transport and reduces light extraction efficiency; third, pixelation introduces leakage current pathways. The patterning process inherently affects PeNCs due to their sensitivity to surface and interfacial modifications, as discussed in Chapter 2. Techniques such as photolithography or direct-photo-patterning often lead to ligand detachment and introduce surface defects, which act as non-radiative recombination centers. The removal or degradation of surface ligands results in increased trap density, reducing charge transport efficiency and accelerated exciton quenching. Moreover, pixelation increases surface roughness, exacerbating nonradiative recombination losses. These effects collectively deteriorate device efficiency and contribute to the performance gap between pixelated and thin-film PeNC LEDs. Addressing these issues requires optimizing patterning techniques and introducing post-processing treatments that repair surface defects and smooth pixel boundaries. Recent advancements in nondestructive optical patterning using carbene-based ligand crosslinkers have demonstrated potential in mitigating patterning-induced damage and preserving PeNC stability20. Apart from the optoelectronic degradation caused by the patterning process, the structural effects of pixelation further exacerbate efficiency losses. Unlike continuous PeNC thin films, where photons propagate freely within the emission layer, pixelation introduces spatial discontinuities that impede photon recycling and increase optical losses. As shown in Fig. 5c, the total sidewall area increases significantly with PPI, increasing by factors of 100, 1000, and 10,000 as PPI increases from 1 to 100, 1000, and 10,000, respectively. This substantial increase in total sidewall area intensifies photon scattering at the pixel boundaries, leading to unwanted optical losses. In continuous thin films, light transport is facilitated through an uninterrupted medium, allowing for enhanced photon recycling, which contributes to increased light extraction. By contrast, in pixelated PeNC LEDs, each emission pixel is surrounded by boundaries such as interpixel gaps and sidewalls. These boundaries act as scattering sites, redirecting photons away from the desired emission path, which reduces light extraction efficiency. Some scattered photons become trapped in waveguide modes, while others are lost to the substrate or adjacent pixels, diminishing the effective output of the device. Additional optical losses arise from the need to suppress interpixel crosstalk in high-density pixelated arrays. To achieve this, black matrix materials or optically isolating barriers are often introduced between pixels, preventing light leakage to neighboring units. However, these materials also absorb scattered light, further reducing the total extracted emission.

Another detrimental effect of pixelation is the increase in leakage current pathways. In continuous PeNC films, charge transport occurs through a homogeneous emission layer, minimizing leakage between the HTL and the ETL. In pixelated devices, however, patterning introduces spatial discontinuities that can facilitate the formation of electrical shunt paths. Aggregation of PeNCs during deposition can lead to percolative charge transport, forming unintended conductive channels that bypass the emission layer. Patterning further exacerbates this issue by creating additional leakage pathways at pixel edges48. While some studies have addressed leakage current suppression by introducing insulating polymer structures, such as PMMA honeycomb frameworks59,97, optimizing the structural design of pixelated LEDs remains critical for minimizing non-radiative recombination losses and improving device performance.

As a result, pixelated PeNC LEDs exhibit a systematic decline in EQE as PPI increases, as evidenced in Fig. 5b. This trend is not unique to PeNC LEDs but is observed across various LED technologies. Similar pixelation-induced efficiency losses are also observed in QLEDs and OLEDs. Pixelated QLEDs exhibit degradation mechanisms closely resembling those of PeNC LEDs, owing to their common use of surface-ligand-stabilized colloidal nanocrystals, which are susceptible to processing-induced structural and optical disruptions. In contrast, pixelated OLEDs—typically fabricated via thermal evaporation, largely avoid such structural damage during pixelation. Their performance degradation is primarily attributed to optical factors, including sidewall scattering and interpixel light absorption, rather than material instability. As a result, the efficiency gap between pixelated and unpatterned OLEDs tends to be less pronounced than in colloidal LED systems. In applications such as near-eye AR/VR displays, achieving ultra-high-resolution LED arrays necessitates minimizing pixel size and interpixel spacing, which makes it increasingly challenging to maintain high EQE at these resolutions. To mitigate the optical and electrical challenges associated with pixelation, several strategies can be employed. Reducing sidewall scattering and reflections through the introduction of passivation layers or the smoothing of pixel boundaries can minimize optical losses. Optimizing the spacing and thickness of pixels can improve optical uniformity, while incorporating high-refractive-index encapsulation materials can mitigate total internal reflection and waveguide effects, thereby enhancing light extraction. Electrically, minimizing leakage current pathways through the use of improved insulating interpixel barriers and optimized charge transport layer configurations can further enhance efficiency. Additionally, improving PeNC stability through ligand engineering and developing defect-free patterning techniques are crucial steps toward fabricating high-performance, high-resolution LED arrays. By stabilizing edge structures, minimizing defect formation, and refining patterning strategies, the efficiency gap between pixelated and thin-film PeNC LEDs can be further narrowed—paving the way for commercially viable, ultra-high-resolution PeNC displays.

Active-emission PeNC LED display

Active-matrix (AM) PeNC LED displays are self-emissive systems that utilize thin-film transistors (TFTs) for precise pixel control, enabling fast response times and high-resolution display performance. This architecture is particularly suited for microdisplays and near-eye AR/VR applications, where independent pixel addressing and compact form factors are critical (Fig. 6a)98,99. TFTs serve as switching devices for individual pixels, avoiding crosstalk and ensuring independent activation. This configuration is essential for modern applications such as AR/VR and micro-LED displays. However, integrating TFTs with PeNC LEDs poses several challenges in terms of material compatibility, process complexity, and operational stability100.

a Device structure diagram of active-matrix technology integrated with PeNC LEDs. b Detailed schematic diagram of the device structure for PeNC LEDs integrated into TFTs circuit after surface reconstruction. c Digital photographs of the active-matrix PeNC LEDs with all the pixels working23, reproduced with permission from ref. 23. Copyright (2024) Springer Nature. d Digital photographs of the RGB emissive AM PeLEDs with BF4- ion passivation77. Reproduced with permission from ref. 77. Copyright (2024) Springer Nature.

TFTs, the backbone of AM displays, control pixel activation by regulating charge carrier flow through a semiconductor channel. As illustrated in Fig. 6b, the structure of a TFT includes a substrate (e.g., glass, silicon, or flexible polymer), a gate electrode, a gate dielectric layer for insulation, and a semiconductor layer. Source and drain electrodes facilitate charge injection and collection, while a passivation layer protects the device against environmental contaminants77,99,100,101. Although TFT technology offers high carrier mobility and operational stability, achieving individual pixel control requires a dedicated TFT for each subpixel. This increases circuit complexity, wiring density, and overall manufacturing cost. To mitigate this, advanced AM addressing schemes have been developed, enabling multi-line control while maintaining precise pixel modulation and compact layouts. These strategies enable high-resolution displays with pixel sizes below 50 µm, enhancing display precision and compactness34.

Among various TFT technologies, low-temperature polycrystalline silicon (LTPS) TFTs and indium gallium zinc oxide (IGZO) TFTs are widely adopted for AM displays. LTPS TFTs provide high mobility (>100 cm²/V·s) and stability, making them suitable for small-to-medium displays like smartphones and AR/VR devices. However, their high fabrication costs are a drawback. In contrast, IGZO TFTs offer moderate mobility (>10 cm2/V·s) but exhibit superior uniformity, transparency, and low-temperature processability99,100,101,102. These advantages make IGZO suitable for large-area, flexible, or high-resolution displays. When integrated with PeNC LEDs, both LTPS and IGZO platforms enable energy-efficient driving and enhance operational reliability under active addressing77,103.

Despite these advancements, PeNC materials continue to face challenges such as ion migration and surface defects, which adversely affect stability and electroluminescence efficiency. To address these stability concerns, chemical surface treatments such as hydroiodic acid and organic acids have been employed to passivate deep-level defects and suppress ion migration. These strategies significantly improve red PeNC LED performance and enable the fabrication of large-area AM-driven arrays (Fig. 6c)23. In addition, replacing conventional ligands such as DDAB with BF4⁻ increases the ionic transport barrier and stabilizes nanocrystals. This strategy promotes the in situ formation of defect-passivated emissive layers with high PLQY, improving the EQE of AM PeNC LEDs to over 20% at 90 PPI, while reducing response times from milliseconds to microseconds (Fig. 6d)77.

Another notable example is the integration of AM-TFT technology with blue PeNC LEDs. Researchers developed a pixel circuit in which the source electrode of an n-channel IGZO TFT is connected to the PeNC LEDs, enabling precise pixel-level current control and light modulation. By combining ligand exchange, anti-solvent treatments, and additive engineering, they achieved a PLQY of 76%, an EQE of 9.81%, and stable emission. This integration demonstrates the feasibility of high-resolution, energy-efficient PeNC displays for flexible electronics, underscoring the feasibility of AM-TFT-driven PeNC displays for next-generation applications64.

The monolithic integration of AM-TFT technology with PeNC LEDs offers a scalable route toward next-generation displays. Continued progress in material passivation, emissive layer engineering, and circuit optimization will be essential to unlocking robust, energy-efficient, and ultra-high-resolution PeNC microdisplays.

Outlook

This review highlights the recent advancements and persistent challenges in pixelated PeNC LEDs, with a focus on material design, patterning techniques, stability strategies, and their integration with active-matrix (AM) addressing technology. Over the past decade, thin-film PeNC LEDs have achieved EQEs exceeding 20% across the RGB spectrum, nearing commercial OLED and QLED performance. However, pixelated counterparts still suffer from efficiency loss and instability, mainly due to patterning-induced defects. Recent innovations in low-damage patterning, ligand chemistry, and hierarchical encapsulation have improved device metrics, while successful TFT integration highlights their feasibility for active-matrix displays.

Looking ahead, the commercialization of pixelated PeNC LEDs requires meeting several stringent performance benchmarks, including high EQE, long-term operational stability, superior color purity, and ultrahigh pixel resolution. While green PeNC LEDs have already demonstrated EQEs exceeding 20%, red and blue counterparts still lag behind, with typical values below 15% and 10%, respectively. Achieving color-balanced, high-efficiency RGB emission with EQE > 20% remains a primary challenge. However, the T95 lifetime (>1000 h) at 1000 cd/m2—a commonly accepted commercial benchmark—still falls short by nearly three orders of magnitude for most PeNC LEDs. On the other hand, PeNCs inherently exhibit narrowband emission (FWHM < 20 nm), making them well suited for wide-gamut display standards such as Rec. 2020. In terms of resolution, active-matrix PeNC LED arrays have reached ~300 PPI, sufficient for tablets, monitors, and televisions. However, near-eye applications such as AR/VR demand far higher pixel densities (≥3000 PPI), with long-term targets exceeding 6000 PPI for retinal-level fidelity.

Compared to III-V Micro-LED, OLEDs and emerging QD-OLEDs technologies, PeNC LEDs offer compelling advantages, including spectral tunability, low-temperature solution processability, and flexible patterning compatibility. Nevertheless, critical challenges remain, particularly in blue and red emission efficiency, long-term operational stability, and scalable manufacturing. Continued progress in material chemistry, device engineering, and system-level integration will be essential to unlock the full potential of pixelated PeNC LEDs as viable candidates for next-generation display technologies.

-

i)

Stability enhancement: Ensuring long-term operational stability under continuous electroluminescence remains a major challenge for PeNC LEDs. Compositional engineering, advanced surface passivation, and robust encapsulation strategies for improving PeNCs are critical for mitigating ion migration and environmental degradation. Core/shell architectures represent a promising solution; however, the epitaxial growth of well-defined covalent-crystal shells remains challenging due to the structurally soft and chemically labile nature of perovskite materials. Unlike traditional CdSe/ZnS quantum dots, where well-established epitaxy requires temperatures exceeding 240 °C for several hours, PeNCs exhibit highly dynamic ligand binding and are prone to crystal fusion and defect formation at such elevated temperature. Recent approaches involving low-temperature metal chalcogenide shell growth have demonstrated enhanced stability, yet challenges such as uncontrolled shell thickness and PeNC fusion persist71,104. Future efforts should focus on low-temperature lattice-matched shelling strategies, rational ligand design to prevent fusion and phase separation, and advanced in situ characterization to elucidate degradation pathways105.

-

ii)

Advanced patterning techniques: The development of high-resolution, damage-free, and multicolor patterning techniques is essential for PeNC LED displays. Traditional methods like photolithography and inkjet printing strike a balance between resolution and scalability but often degrade material properties. Non-destructive optical patterning, including ligand crosslinking and laser-assisted writing, offers high-fidelity structuring while preserving PeNC integrity. Transfer printing and nanoimprint lithography enable sub-micron resolution with minimal damage. Hybrid approaches, such as inkjet printing for large-area deposition combined with laser or photolithographic refinement, offer scalable solutions. Halide exchange techniques enable in situ multicolor patterning without additional material deposition. Future research should focus on self-assembled nanostructures, interfacial engineering, and scalable printing to enhance uniformity and stability while minimizing efficiency losses. Refining these methodologies will bridge the gap between research and commercialization, propelling PeNC LEDs toward next-generation AR/VR and ultra-high-resolution displays.

-

iii)

Optimized optical management: Pixelation-induced optical losses remain a key bottleneck in PeNC LED efficiency. The waveguiding effect within the device stack and scattering at pixel boundaries lead to reduced light extraction and color crosstalk. Strategies such as employing high-refractive-index encapsulation layers, optimizing pixel geometries, and introducing passivation layers have shown potential in mitigating these losses. Additionally, simulation-guided optical designs—including FDTD (Finite-difference time-domain) and RCWA (Rigorous coupled-wave analysis) approaches—can help optimize pixel layout, reduce waveguiding, and boost extraction efficiency. Combining these approaches with advanced material engineering will be crucial for maximizing the brightness and uniformity of pixelated PeNC displays.

-

iv)

High-resolution full-color active-matrix displays: The demand for ultra-high-resolution displays (>3000 PPI) in AR/VR applications necessitates precise material engineering and device integration strategies. The combination of PeNC emissive layers with high-mobility TFTs, such as IGZO and flexible transistor technologies, can enable accurate pixel current control and high refresh rates. However, achieving stable and efficient full-color emission at these resolutions remains challenging due to ion migration, efficiency losses in pixelated structures, and the complexities of RGB integration. Currently, most AM PeNC-based displays operate in single-color modes, and full-color realization faces additional obstacles. The precise patterning of red, green, and blue PeNCs without cross-contamination remains difficult, as conventional methods like inkjet printing and photolithography struggle to achieve the required resolution and uniformity. Furthermore, mixed-halide perovskites, commonly used for blue and red emission, suffer from phase separation and spectral instability under operating conditions. Future research should focus on compositionally stable RGB PeNCs, advanced patterning techniques for high-resolution color integration, and optimized charge transport layers to improve efficiency and longevity. Addressing these challenges will be key to enabling high-performance PeNC AM displays for next-generation AR/VR applications.

-

v)

Sustainability and scalability: As PeNC LEDs advance toward commercialization, ensuring environmentally sustainable and scalable manufacturing is paramount. Despite lead content concerns, lifecycle assessments suggest PeNCs may offer a lower environmental footprint than conventional display technologies, owing to ultrathin active layers and low-temperature processing105. The color-conversion application of PeNC emitters in blue LED and OLED backlit displays requires less energy compared with conventional inorganic quantum dots due to their higher PLQY and extinction coefficient. This advantage offers a more energy-efficient alternative to the existing display technologies. Further advancements in eco-friendly solvents, metal electrode recycling, and solvent-free deposition methods will enhance the sustainability of PeNC-based displays. Additionally, transitioning large-scale fabrication processes to renewable energy sources will further reduce their environmental impact.

By addressing these key challenges through interdisciplinary innovation, PeNC LEDs are poised to redefine the landscape of display technologies. Their exceptional optoelectronic properties—combined with advancements in stability, patterning, and active-matrix integration—will accelerate the transition from laboratory research to commercial deployment. Continued innovation in material chemistry, optoelectronic engineering, and scalable manufacturing is expected to unlock the full potential of pixelated PeNC LEDs, enabling ultrahigh-resolution, energy-efficient, and full-color displays across AR/VR, mobile, and large-area platforms. As performance continues to improve, PeNC LEDs are well positioned to meet the demanding requirements of next-generation consumer electronics, solid-state lighting, and immersive visual systems.

References

Kovalenko, M. V., Protesescu, L. & Bodnarchuk, M. I. Properties and potential optoelectronic applications of lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Science 358, 745–750 (2017).

Kim, Y. H., Cho, H. & Lee, T. W. Metal halide perovskite light emitters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11694–11702 (2016).

Sutherland, B. R. & Sargent, E. H. Perovskite photonic sources. Nat. Photon. 10, 295–302 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Perovskite nanocrystals: synthesis, stability, and optoelectronic applications. Small Struct. 2, 2000124 (2021).

Pacchioni, G. Highly efficient perovskite LEDs. Nat. Rev. Materials 6, 108–108 (2021).

Ma, D. et al. Distribution control enables efficient reduced-dimensional perovskite LEDs. Nature 599, 594–598 (2021).

Fakharuddin, A. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Electron. 5, 203–216 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. All-inorganic lead halide perovskite nanocrystals applied in advanced display devices. Mater Horiz 10, 1969–1989 (2023).

Yan, F. & Demir, H. V. LEDs using halide perovskite nanocrystal emitters. Nanoscale 11, 11402–11412 (2019).

Lin, K. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 per cent. Nature 562, 245–248 (2018).

SNDISPLAY. SNDISPLAY Produces Next-Generation Display Materials. https://www.sndisplay.com/ (2024).

Guo, B. et al. Ultrastable near-infrared perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 16, 637–643 (2022).

Kim, J. S. et al. Ultra-bright, efficient and stable perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nature 611, 688–694 (2022).

Peng, C. et al. Weakly space-confined all-inorganic perovskites for light-emitting diodes. Nature 643, 96–103 (2025).

Lian, Y. et al. Downscaling micro- and nano-perovskite LEDs. Nature 640, 62–68 (2025).

Kim, Y.-H. et al. Comprehensive defect suppression in perovskite nanocrystals for high-efficiency light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 15, 148–155 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Brightly luminescent and color-tunable colloidal CH3NH3PbX3 (X = Br, I, Cl) quantum dots: potential alternatives for display technology. ACS Nano 9, 4533–4542 (2015).

Wei, C. et al. A universal ternary-solvent-ink strategy toward efficient inkjet-printed perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 34, e2107798 (2022).

Luo, C. et al. High-resolution, highly transparent, and efficient quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater 35, e2303329 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. Nondestructive direct optical patterning of perovskite nanocrystals with carbene-based ligand cross-linkers. ACS Nano 18, 6896–6907 (2024).

Kwon, J. I. et al. Ultrahigh-resolution full-color perovskite nanocrystal patterning for ultrathin skin-attachable displays. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd0697 (2022).

Ma, T. et al. One-step, mask-free, rapid laser writing fabrication of electroluminescent perovskite@oxide pixels for ultra-high ppi, efficient Micro-QLEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2413811 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Nanosurface-reconstructed perovskite for highly efficient and stable active-matrix light-emitting diode display. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 638–645 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Matched electron-transport materials enabling efficient and stable perovskite quantum-dot-based light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202410689 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Highly efficient blue light-emitting diodes based on mixed-halide perovskites with reduced chlorine defects. Sci. Adv. 10, eado5645 (2024).

Jeon, Y., Ryu, H. & Lee, H. Recent progress on blue quantum dot light-emitting diodes from materials to device engineering. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 41, 3483–3500 (2024).

Lee, G. H., Kim, K., Kim, Y., Yang, J. & Choi, M. K. Recent advances in patterning strategies for full-color perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nanomicro. Lett. 16, 45 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Micro-light-emitting diodes with quantum dots in display technology. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 83 (2020).

Park, S. J. et al. Progress and prospects of nanoscale emitter technology for AR/VR displays. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201070 (2022).

Shan, Q. et al. Perovskite quantum dots for the next-generation displays: progress and prospect. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401284 (2024).

Kim, J. I. et al. Strategies to extend the lifetime of perovskite downconversion films for display applications. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209784 (2023).

Ni, T. et al. IEEE VR 2025: the 32nd IEEE conference on virtual reality and 3D user interfaces. In IEEE Virtual Reality Conference (VR 2006). 223−236 (IEEE, 2025).

Young, B. OLED displays and the immersive experience. Inform. Display 34, 16–36 (2018).

Hsiang, E.-L. et al. AR/VR light engines: perspectives and challenges. Adv. Opt. Photon. 14, 783−861 (2022).

Park, S. Y., Lee, S., Yang, J. & Kang, M. S. Patterning quantum dots via photolithography: a review. Adv. Mater. 35, e2300546 (2023).

Lee, J. W. & Kang, S. M. Patterning of metal halide perovskite thin films and functional layers for optoelectronic applications. Nanomicro. Lett. 15, 184 (2023).

Liu, Y., Li, F. & Huang, W. Perovskite micro-/nanoarchitecture for photonic applications. Matter 6, 3165–3219 (2023).

Liang, L. et al. Patterning technologies for metal halide perovskites: a review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200419 (2022).

Eisenfeld, T. & Karsenty, A. Design and modeling of light emitting nano-pixel structure (LENS) for high resolution display (HRD) in a visible range. Nanomaterials (Basel) 10, 214 (2020).

Ando, B. et al. Low-cost inkjet printing technology for the rapid prototyping of transducers. Sensors (Basel) 17, 748 (2017).

Rehmani, M. A. A. & Arif, K. M. High resolution electrohydrodynamic printing of conductive ink with an aligned aperture coaxial printhead. Int. J. Adv. Manufact. Technol. 115, 2785–2800 (2021).

Jeong, B., Han, H. & Park, C. Micro- and nanopatterning of halide perovskites where crystal engineering for emerging photoelectronics meets integrated device array technology. Adv. Mater. 32, e2000597 (2020).

Yang, J., Yoo, J., Yu, W. S. & Choi, M. K. Polymer-assisted high-resolution printing techniques for colloidal quantum dots. Macromol.r Res. 29, 391–401 (2021).

Park, J. U. et al. High-resolution electrohydrodynamic jet printing. Nat. Mater. 6, 782–789 (2007).

Bai, W. et al. Microscale perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes (Micro-PeLEDs) for full-color displays. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200087 (2022).

Mampallil, D. & Eral, H. B. A review on suppression and utilization of the coffee-ring effect. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 252, 38–54 (2018).

Palma, A. L. et al. Laser-patterning engineering for perovskite solar modules with 95% aperture ratio. IEEE J. Photovoltaics 7, 1674–1680 (2017).

Li, D. et al. Inkjet printing matrix perovskite quantum dot light-emitting devices. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000099 (2020).

Lee, H., Jeong, J. W., So, M. G., Jung, G. Y. & Lee, C. L. Design of chemically stable organic perovskite quantum dots for micropatterned light-emitting diodes through kinetic control of a cross-linkable ligand system. Adv. Mater. 33, e2007855 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Progress on inkjet printing technique for perovskite films and their optoelectronic and optical applications. ACS Photon, 10, 3435–3450 (2023).

Liu, Y.-F., Tsai, M.-H., Pai, Y.-F. & Hwang, W.-S. Control of droplet formation by operating waveform for inks with various viscosities in piezoelectric inkjet printing. Appl. Phys. A 111, 509–516 (2013).

Sun, C., Jiang, Y., Wei, K. & Yuan, M. Perovskite light-emitting diodes toward commercial full-colour displays: progress and key technical obstacles. Light Adv. Manuf. 4, 26 (2023).

Hertaeg, M. J., Rees-Zimmerman, C., Tabor, R. F., Routh, A. F. & Garnier, G. Predicting coffee ring formation upon drying in droplets of particle suspensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 591, 52–57 (2021).

Du, Z., Zhou, H., Yu, X. & Han, Y. Controlling the polarity and viscosity of small molecule ink to suppress the contact line receding and coffee ring effect during inkjet printing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 602, 125111 (2020).

Gao, A. et al. Printable CsPbBr(3) perovskite quantum dot ink for coffee ring-free fluorescent microarrays using inkjet printing. Nanoscale 12, 2569–2577 (2020).

Han, J. W., Hwang, S. H., Seol, M. J. & Kim, S. Y. Recent patterning methods for halide perovskite nanoparticles. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200534 (2022).

Meitl, M. A. et al. Transfer printing by kinetic control of adhesion to an elastomeric stamp. Nat. Mater. 5, 33–38 (2005).

An, H. J., Kim, M. S. & Myoung, J.-M. Strategy for the fabrication of perovskite-based green micro LED for ultra high-resolution displays by micro-molding process and surface passivation. Chem. Eng. J. 453, 139927 (2023).

Mao, C. et al. Ultra-high-resolution perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2202058 (2022).

Hah, J. H. et al. Converging lithography by combination of electrostatic layer-by-layer self-assembly and 193nm photolithography: Top-down meets bottom-up. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 24, 2209–2213 (2006).

Manouras, T. & Argitis, P. High sensitivity resists for EUV lithography: a review of material design strategies and performance results. Nanomaterials (Basel) 10, 1593 (2020).

Kim, G. H. et al. High-resolution colloidal quantum dot film photolithography via atomic layer deposition of ZnO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 43075–43084 (2021).

Pan, J. A., Ondry, J. C. & Talapin, D. V. Direct optical lithography of CsPbX(3) nanocrystals via photoinduced ligand cleavage with postpatterning chemical modification and electronic coupling. Nano Lett. 21, 7609–7616 (2021).

Palazon, F., Prato, M. & Manna, L. Writing on nanocrystals: patterning colloidal inorganic nanocrystal films through irradiation-induced chemical transformations of surface ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13250–13259 (2017).

Oh, B. M. et al. Simple one-pot synthesis and high-resolution patterning of perovskite quantum dots using a photocurable ligand. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 57, 12824–12827 (2021).

Shin, S. et al. Light-induced crosslinking of perovskite nanocrystals for all-solution-processed electroluminescent devices. Appl. Surf. Sci. 608, 155016 (2023).

Ong, W. Y. E., Tan, Y. Z. D., Lim, L. J., Hoang, T. G. & Tan, Z. K. Crosslinkable ligands for high-density photo-patterning of perovskite nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 37, e2409564 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. Direct optical patterning of perovskite nanocrystals with ligand cross-linkers. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8433 (2022).

Maeng, S. et al. Dual-strategy direct photocatalytic patterning for efficient perovskite nanocrystal LED display. Adv Mater. 31, e08217 (2025).

Huang, H., Bodnarchuk, M. I., Kershaw, S. V., Kovalenko, M. V. & Rogach, A. L. Lead halide perovskite nanocrystals in the research spotlight: stability and defect tolerance. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2071–2083 (2017).

Zhang, X., Yin, W., Zheng, W. & Rogach, A. L. Perovskite quantum dots with atomic crystal shells for light-emitting diodes with low efficiency roll-off. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2927–2934 (2020).

Das Adhikari, S. et al. Impact of core-shell perovskite nanocrystals for LED applications: successes, challenges, and prospects. Chem. Sci. 14, 8984–8999 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. All-in-one process for color tuning and patterning of perovskite quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 9, e2200073 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Transfer-printed, tandem microscale light-emitting diodes for full-color displays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2023436118 (2021).

Hassan, Y. et al. Ligand-engineered bandgap stability in mixed-halide perovskite LEDs. Nature 591, 72–77 (2021).

Zeng, Q. et al. Surface stabilization of colloidal perovskite nanocrystals via multi-amine chelating ligands. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1963–1970 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Microsecond-response perovskite light-emitting diodes for active-matrix displays. Nat. Electron. 7, 487–496 (2024).

Lyu, B. et al. Side-chain-promoted polymer architecture enabling stable mixed-halide perovskite light-emitting diodes. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 2118–2127 (2024).

Feng, Y. et al. Nucleophilic reaction-enabled chloride modification on CsPbI(3) quantum dots for pure red light-emitting diodes with efficiency exceeding 26. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202318777 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Thermal management towards ultra-bright and stable perovskite nanocrystal-based pure red light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 15, 6561 (2024).

Wang, Y. K. et al. Long-range order enabled stability in quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nature 629, 586–591 (2024).