Abstract

Luffa sponge features a naturally optimized three-dimensional fibrous network, forming a lightweight and highly deformable bio-structure with high energy absorption capacity. Here we show that it can serve as a sustainable reinforcement to improve the impact resistance of cementitious composites. When embedded in cement paste, the luffa sponge forms a synergistic interface that enhances structural integrity and allows the composite to endure repeated impacts with minimal fragmentation. The composite maintains stable performance across a wide temperature range from –196 °C to 200 °C, showing low thermal sensitivity. Microscopic imaging and simulations reveal a gradual interfacial transition zone where hydrogen bonding leads to strength variation across the interface. This transition improves load transfer and contributes to overall durability. These findings highlight the potential of using bio-derived, architectured materials like luffa sponge to develop resilient and sustainable cement-based composites for structural applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Impact-resistant materials are crucial for applications where materials must absorb and dissipate energy effectively without significant deforming or failing under sudden impacts1. These materials, such as metals2, rubbers3, ceramics4, and polymers5, are selected based on specific application needs. Impact-resistant cementitious composite materials have received increased interest due to their advantages6. Notably, cementitious composites offer superior durability and longevity compared to metals and rubbers, making them ideal for infrastructure projects that demand low maintenance over long periods. Furthermore, when compared to advanced polymers and ceramics, cementitious composites are more economically viable due to their wide availability and lower cost of cement. For context, the global consumption of cement in 2023 was 4.2 billion tons, exceeding the production volumes of many staple crops, such as wheat7. This vast scale of production underlines the accessibility and cost-effectiveness of cement as a raw material. Given these benefits, impact-resistant cementitious composites are extensively used in protective structures, especially in various strategically important infrastructures. For example, they are employed in the construction of nuclear power plants, particularly in containment structures designed to withstand extreme events8,9. Additionally, these materials are increasingly utilized in water treatment plants10, sewer systems11, and other facilities requiring durable materials capable of withstanding harsh, corrosive environments.

Despite the inherent quasi-brittle nature of cement, which exhibits brittle fractures under tensile and shear stresses, advancements in material science have led to significant improvements in its impact resistance. This is primarily achieved through the even dispersion of various fibers in a matrix, such as steel, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and polypropylene fibers, enhancing the toughness, strength, and ductility of cementitious composites12. These innovations have paved the way for the development of fiber-reinforced cementitious composites, such as Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) with ultra-high ductility and Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) noted for its exceptional strength13,14,15. Fibers enhance the impact resistance of cementitious composite by creating a fiber bridging effect that distributes stress across the matrix16. However, often these fibers act independently (as they are distributed evenly in the matrix) without forming a unified network, and thus limit the potential for comprehensive impact resistance improvement17,18. Moreover, traditional fiber-reinforced cementitious composites also exhibit cold brittleness, which is similar to metals and ceramics. As the temperature decreases, their toughness and energy dissipation capacity gradually decline, making them unsuitable for applications in extremely low-temperature environments19.

Building upon the technological advancements in cementitious composites, nature itself provides inspiration for impact-resistant materials through the example of the dried fibrous core of the luffa, a plant from the gourd family. The luffa’s fibrous structure is naturally equipped for impact resistance due to its three-dimensional, interlaced fiber network20,21. This arrangement not only enhances the mechanical integrity and shock absorption capabilities but also aligns with the fundamental characteristics required for impact-resistant materials22. In addition, luffa is an abundantly cultivated plant in many tropical and subtropical regions, with significant annual production globally, particularly in Asia, Africa, and South America. Moreover, synthetic or bioengineered analogues of luffa sponge structures can be developed using biodegradable polymers, offering scalable alternatives that retain the desired fibrous morphology. These aspects enhance the material’s potential as a sustainable and industrially feasible reinforcement in cementitious composites. Such bio-inspired designs highlight potential avenues for developing advanced materials that mimic these natural structures, offering improved performance and sustainability. Shen et al.23,24 investigated the basic mechanical properties of luffa sponge and concluded that the luffa sponge was ideal for energy absorption applications as an ultra-light cellular material. The structure of the luffa sponge, characterized by a significant contact area due to its spatially chaotic fiber arrangement, has found successful applications in energy and environmental sectors in recent years25,26. Actually, previous studies have already revealed its potential in cementitious composites, demonstrating improvements in energy absorption, tensile strength, and ductility27,28,29. The morphology and mechanical characteristics of the luffa sponge, as shown in Fig. 1, reveal various three-dimensional energy-absorbing structural units, e.g., tubular units, fibrous units, and cellular units (see Fig. 1a). More importantly, the core area of the luffa sponge, which contains coarser fibers, provides a complete support system for the fibers in the outer wall region, thereby enhancing the overall structural integrity under axial load (see Fig. 1b). Given these characteristics, the impact performance of the luffa sponge stands out within the realm of natural plants, making it an ideal, naturally topology-optimized green energy-absorbing material (see Fig. 1c).

This paper aims to systematically investigate bioinspired impact-resistant cementitious composite materials based on luffa sponge. Unlike the independent toughening mechanism of conventional short-cut fibers in cementitious composites, it is expected that the spatial network structure of luffa sponge fibers can form an integrated toughening system within the cementitious matrix. While the effectiveness of luffa sponge in improving impact performance has been well documented in polymer-based composites, its application in cementitious composites, particularly under extreme temperature conditions, remains largely unexplored. This study incorporated the natural three-dimensional fiber system of luffa sponge into the cement matrix to enhance its toughness and evaluates the performance improvements through impact tests. Building on this, the study first investigates the impact resistance of luffa sponge-reinforced cementitious composites (LSRCC) under ambient conditions, confirming the enhancement in impact resistance provided by the luffa sponge within the cementitious paste. Subsequently, addressing the cold brittleness commonly observed in existing impact-resistant materials, the study is the first to explore the impact performance of LSRCC across a wide temperature range (from −196 to 200 °C), validating its feasibility as an impact-resistant material for extreme environments. Moreover, utilizing a combination of Focused Ion Beam (FIB) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), the interface transition zone between the luffa sponge and the cementitious paste is characterized at the nanoscale, providing insights into the morphological and physicochemical features contributing to their synergistic behavior. Finally, based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), the interface between cement and the cellulose of luffa sponge was analyzed. The simulation modeled the distribution characteristics of water molecules at the cement-cellulose composite interface, verifying that the hydrogen bonding within the cellulose matrix contributes to the gradual variation in water-to-cement ratio across the interfacial region, thereby leading to a gradual transition in interfacial strength.

Results

Mechanical characterization of materials

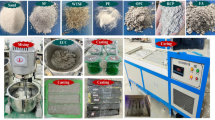

The basic mechanical and physicochemical properties of cement and luffa sponge are presented in Fig. 2. The cement used in this study was ordinary Portland cement (42.5 R), with a fixed water-to-cement ratio of 0.3. This ratio was selected because it is one of the most widely used ratios in the design of high-performance cementitious composites. The luffa sponge was derived from the vascular bundles of the mature fruit of the annual herbaceous plant Luffa (from the Cucurbitaceae family), commonly used as cleaning tools or seat cushions. The mechanical and physicochemical characteristics of cement are illustrated in Figs. 2a through 2d. Under uniaxial compressive loading, the cement specimens exhibited typical brittle failure, which is why cement or concrete alone is generally unsuitable as impact-resistant materials. The uniaxial compressive behavior of the luffa sponge, as shown in Fig. 2e, demonstrated notable force plateau and secondary stiffening characteristics. However, its compressive load capacity remained below 1 kN due to the abundant voids within the fiber bundles of the luffa sponge, exhibiting significant deformation with a normal strain exceeding 0.6 (see Fig. 2f). The microscopic porosity of the luffa sponge, shown in the right side of Fig. 2f, further indicated that it is not suitable for bearing loads independently.

a Load-deformation behavior of cement paste under quasi-static compression. b Particle size distribution of cement powder. c, d X-ray diffraction (XRD) of raw cement before and after hydration. e Load-deformation behavior of luffa sponge under quasi-static compression. f Deformation characteristics of luffa sponge under quasi-static compression. The longitudinal straight dashed lines buckled after compression, indicating significant folding of the luffa sponge. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image exhibited the multi-tubular microstructure of the luffa sponge fiber. g Preparation of LSRCC specimens. h Load-deformation behavior of LSRCC under quasi-static compression. i Damage and deformation of LSRCC at four typical stages, i.e., elastic (Ⅰ), cover cement spalling (Ⅱ), significant compression and damage (Ⅲ), and densely compressed (Ⅳ), corresponding to (h).

This study explored the combination of cement paste and luffa sponge, utilizing the luffa sponge to enhance the toughness of the cement paste. The production process of LSRCC is illustrated in Fig. 2g. First, cement was mixed with water to form a paste, after which the luffa sponge was fully immersed in the cement paste. It should be noted that the luffa sponge was kept in an absolutely dry state prior to immersion in the cement paste to ensure optimal pore infiltration and interfacial bonding. The composite was then cured for 28 days under standard curing conditions. Upon completion of the preparation and curing process, uniaxial compressive tests were conducted on the LSRCC specimens, as shown in Fig. 2h. The test results revealed a significant enhancement in both stiffness and strength in the LSRCC specimens, with a peak force reaching 320 kN, exceeding the simple linear addition of the compressive strengths of cement and luffa sponge alone. This confirms the outstanding synergistic effect of cement matrix and luffa sponge in LSRCC. The failure process under axial compression is depicted in Fig. 2i, where the fiber toughening effect of the luffa sponge significantly improved the brittle nature of the cement paste, resulting in a clear ductile failure mode.

Impact resistance characterization

Following the completion of the axial compressive mechanical performance tests on LSRCC, the impact resistance under ambient temperature was investigated. The test setup is detailed in Fig. 3a, b and the Methods section. Briefly, the impact loading was achieved by using a drop-weight impact test machine with the input energies of 300 J, 500 J, and 700 J. All test data were recorded by the test machine, meanwhile, the corresponding failure process was captured by a high-speed camera (Supplementary Movies 1, 2, and 3). In addition to varying the input energy, the study also examined the effects of multiple impacts on the cumulative damage evolution of LSRCC. This involved repeated impacts at a constant height, until the specimen was completely damaged, to simulate repeating impact loads that might be induced by mechanical transmission systems on the composite materials. When the impact energy was set to 300 J (drop height of 2820 mm), the failure process of the LSRCC specimen under repeated impacts was captured by the high-speed camera, as shown in Fig. 3c. These snaps illustrate the failure characteristics of the specimen at the 1st, 5th, and 9th impacts. From these snapshots, it is evident that although the outer cement paste “protective layer” exhibited early delamination, the core luffa sponge and the encased cement paste maintained perfect synergy. Even after the 9th impact, the overall integrity of the specimen was preserved, demonstrating significant impact ductility. This result correlates well with the axial compressive test findings shown in Fig. 2h, i. The progressive failure modes of the LSRCC specimens after the 1st to 9th impact loads are depicted in Fig. 3d, clearly illustrating the damage evolution process. Despite noticeable outer layer delamination and crushing, the luffa sponge and cement paste continued to work in unison, confirming the effectiveness of the luffa sponge’s spatially entangled fibers in reinforcing the cement paste.

a, b Setup of drop-weight impact test. c High-speed photographs showing the damage processes of LSRCC subjected to repeated drop-weight impacts with the input energy of 300 J. d Initial and residual states of LSRCC after repeated impacts. e Force-displacement curves and energy absorption of LSRCC under repeated impacts. The error bars represent the variability observed across three replicate tests.

Figure 3e presents the force-displacement curves and energy dissipation of the LSRCC specimens under different impact energies and impact counts. Overall, with increasing input impact energy, the peak force and absorbed energy of the LSRCC specimens showed an upward trend. In particular, the peak forces under the first impacts of 300 J, 500 J, and 700 J were 130.80 kN, 174.04 kN, and 180.45 kN, respectively, with the corresponding absorbed energies being 8.61 J, 27.84 J, and 120.23 J. For a fixed input impact energy, the increase in the number of impacts caused a gradual reduction in peak force, yet the energy dissipation per impact increased progressively. Observing the force-displacement curves, it is apparent that with the increasing number of impacts, the “plateau stage” of the curve became wider. It is inferred that the luffa sponge fibers experience more pronounced delamination and fracture under repeated impact loads, and this “plateau stage” corresponds to the fiber delamination process within the cement paste. Naturally, the delamination and debonding of the fibers contribute to energy dissipation. The impact tests conducted at ambient temperature demonstrated that, thanks to the reinforcing effect of the luffa sponge on the cement paste, the LSRCC specimens exhibited excellent impact resistance. Notably, under repeated impact loads, there was a remarkable increase in the energy dissipation per impact, indicating that LSRCC specimens are highly suitable for applications involving multiple impact loads.

Environmental temperature effects

Following the investigation of the impact resistance of LSRCC specimens under ambient temperature conditions, further research was conducted to examine the effect of environmental temperature on their impact resistance. During service, impact-resistant materials inevitably experience temperature fluctuations, and conventional materials often exhibit significant “temperature sensitivity”30,31. For both cementitious and metallic materials, it is generally observed that as the temperature decreases, strength and stiffness increase, while ductility significantly decreases32,33. In this study, the variation of environmental temperature was achieved by using a heating chamber and a cryogenic container for high- and low-temperature scenarios respectively, which is detailed in the Method section. Impact tests considering temperature effects were conducted at −196 °C, −78.5 °C, 25 °C, 100 °C, and 200 °C, under repeated impacts at energy levels of 300 J, 500 J, and 700 J. Throughout these tests, high-speed imaging (Supplementary Movies 4, 5, and 6) and the sensors embedded in the drop-weight hammer were used to record the impact process.

All the energy dissipated by the specimen during each impact and the corresponding peak force recorded by the drop hammer are presented in Fig. 4a, with additional data extracted from this figure for comparison. As shown, the number of repeated impacts decreases as the temperature increases or decreases for all three energy levels, with the most pronounced reduction observed at 300 J, where the impact count dropped from 9 at 25 °C to 3 at both 200 °C and −196 °C. In terms of peak force during the first impact, no significant temperature sensitivity was observed for all three energy levels (Fig. 4b). Similarly, when the energy dissipated in the first impact was normalized by the input energy of the hammer, the energy dissipation also showed no significant temperature sensitivity across the three energy levels (Fig. 4c). It is known that plain cement, as a cement-based material with ceramic-like properties, exhibits strong temperature sensitivity in terms of impact resistance18,34. However, LSRCC maintains stable impact performance across a wide temperature range, especially when compared to the known behavior of plain cement. Considering the disintegration of the core matrix as the termination condition, the cumulative energy dissipation of the specimens subjected to repeated impacts at different temperatures and energy levels is shown in Fig. 4d. At 25 °C, the number of impacts and cumulative energy dissipation reached their maximum for all three energy levels. However, both the number of impacts and the cumulative energy dissipation decreased as the temperature increased or decreased. Interestingly, under 700 J impacts, the cumulative energy dissipation after the second impact at 200 °C and −196 °C exceeded that of 100 °C and −78.5 °C. This phenomenon can be attributed to the thermal decomposition of luffa fibers at 200 °C and the crystallization of water at −196 °C, which caused the LSRCC to exceed the termination condition of core concrete disintegration during the second impact at these temperatures, leading to more severe specimen failure compared to the other three temperatures (Fig. 4e). High-speed imaging of the 300 J impact at −196 °C (Fig. 4f) revealed a significant reduction in the constraint provided by the luffa fibers to the cement matrix, with the specimen displaying blocky failure in contrast to the high-speed images taken at 25 °C (Fig. 3c). This study demonstrates that, although the energy dissipation capacity of LSRCC specimens showed varying degrees of reduction in ultra-low-temperature environments, the overall failure morphology remained relatively intact, indicating the suitability of LSRCC as an impact-resistant material for ultra-low-temperature conditions.

a Peak force and energy dissipation of all LSRCC specimens at various temperature conditions. b, c Peak force and energy dissipation of LSRCC specimens under the first impact. d The cumulative energy dissipation of the LSRCC specimens subjected to repeated impacts at different temperatures. e Side panorama view of the damage of the LSRCC specimens under the first impact at various temperatures with input energy of 300 J. f High-speed photographs show the damage evolution of LSRCC subjected to repeated impacts with the temperature at −196 °C and input energy of 300 J.

Interface characterization

Following the completion of impact performance tests at both ambient, elevated, and ultra-low temperatures, this study proceeded with a mechanism-level analysis of the interface between the luffa sponge and the cement paste in LSRCC specimens using FIB combined with TEM, namely the FIB-TEM technique. FIB enables the precise cutting of sample material, preparing samples with a thickness on the order of tens of nanometers, making them suitable for TEM imaging. The samples prepared by FIB allow high-resolution imaging in the TEM, facilitating the observation of nanoscopic features such as crystal structures, defects, and dislocations. Figure. 5a shows the cross-sectional slices obtained via FIB sample preparation. From these, five regions were selected for further analysis: P1 and P2 located across the luffa sponge fiber-cement paste interface; C, located within the cement matrix; and L, within the fiber itself, as well as the broader Area M. The dark field (HADDF) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping for Areas M (with Ca in yellow, Si in green, C in red, and K in orange) are shown in Fig. 5b, with the interface marked in orange. Further magnification and EDS mapping of Area P2 is presented in Fig. 5c, followed by a line scan along the indicated path, as shown in Fig. 5d. In Fig. 5e, region P1 is further divided into P1-1 (cement matrix), P1-2 (interface region containing both luffa fiber and cement), and P1-3 (within the luffa fiber). Enlargements of P1-1 and C, followed by Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis, are shown in Fig. 5f. Similarly, enlargements and FFT of P1-3 and L are presented in Fig. 5g. The interface region P1-2 are magnified in Fig. 5h, with the three lattice structures R1, R2, and R3 highlighted. The FFT and corresponding inverse FFT (IFFT) analyses of this interface region are also shown in Fig. 5h, where the FFT of R1, R2, and R3 in FFT align along distinct rings, with the corresponding IFFT lattice fringes and spacings of 0.28 nm, 0.24 nm, and 0.17 nm.

a The overall morphology of the target area obtained through FIB. b, c The HAADF micrograph and main element mappings of Ca, Si, C, and K covering Areas M and P2, respectively. d The linescan profile of the four elements along the blue dashed line indicated in Area P2. e Magnified image of Area P1, indicating the ITZ between cement and luffa sponge. f Comparison of the zoomed-in images and FFT between Areas P1-1 and C. g Comparison of the zoomed-in images and FFT between Areas P1-3 and L. h Zoomed-in image of the Area P1-2, and the FFT and IFFT of the phases corresponding to R1, R2, and R3, respectively. i Water adsorbed on CaAl₂O₄; j on CaSiO₃; k on cellulose, where water forms three hydrogen bonds with the cellulose backbone. l–n RDG scatter plots for (i–k), highlighting weak interactions in the sign(λ₂)ρ range of −0.035 to 0.02a.u.; cellulose (n) exhibits the strongest weak interactions. o Adsorption energies: cellulose (−2.51 eV), CaAl₂O₄ (−1.24 eV), and CaSiO₃ (−1.79 eV), indicating cellulose’s higher affinity for water. p Electrostatic potential surface of cellulose, showing predominantly positive potential, which facilitates water molecule adsorption.

Based on the FIB-TEM analysis, it is evident that a distinct Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) exists between the luffa sponge fiber and the cement matrix. In this study, the ITZ refers to a transitional interphase with synergistic behavior, rather than a mechanically inferior zone in the conventional sense. This indicates that the connection between the two is not merely mechanical but exhibits certain synergistic effects. A possible explanation is that luffa sponge fibers, being hydrophilic, contain numerous hydroxyl groups (–OH) in their cellulose molecules, which can readily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. This likely alters the water-to-cement ratio in the transition zone, creating a gradient in strength from the luffa sponge to the cement paste. This may explain the “1 + 1 > 2” effect observed under both static compressive and impact loads, where impact forces are efficiently transferred across the ITZ, leading to a more unified load-bearing performance in the LSRCC as opposed to localized failure. The failure modes observed in LSRCC specimens under compressive and impact loading further support this hypothesis.

Building on the nanoscale experimental foundation, this study further conducted simulation analyses of the cement-cellulose interface using DFT. The primary objective was to model the distribution characteristics of water molecules at the cement-cellulose composite interface. To facilitate the DFT computational modeling of cement systems, we considered CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃ as the primary approximate constituents of cement. Fig. 5i, j illustrate the adsorption of water molecules on CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃ surfaces, respectively, while Fig. 5k depicts water molecule adsorption on cellulose. Analysis of the adsorption structures reveals that the water molecules adsorbed on cellulose form three hydrogen bonds with the cellulose matrix, indicating a robust interaction facilitated by the hydroxyl groups inherent to cellulose. The adsorption energies presented in Fig. 5o further substantiate the superior affinity of cellulose for water molecules compared to CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃. Specifically, the adsorption energy of water molecules on cellulose is calculated to be −2.51 eV, markedly higher than that on CaAl₂O₄ (−1.24 eV) and CaSiO₃ (−1.79 eV). This significant difference suggests that cellulose has a heightened propensity for water adsorption, likely due to its abundant hydrogen-bonding sites, which enhance its interaction with water molecules. Fig. 5l, n display the reduced density gradient (RDG) scatter plots used for weak interaction analysis. The RDG isosurfaces are colored within a sign(λ₂)ρ range of −0.035 to 0.02 atomic units (a.u.), corresponding to weak interaction regions, utilizing the default blue-green-red color scale. Notably, Fig. 5n, representing cellulose with adsorbed water molecules, exhibits the most pronounced weak interactions among the samples studied. The increased intensity and distribution of the RDG isosurfaces in this figure indicate stronger van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding in the cellulose-water system, highlighting the significant role of weak interactions in the adsorption process on cellulose. Fig. 5p illustrates the electrostatic potential (ESP) surface of cellulose, revealing regions of both positive and negative potential, with a predominance of positive electrostatic potential. This positively charged surface is conducive to the adsorption of water molecules, as the electronegative oxygen atoms of water can interact favorably with these regions. The predominance of positive ESP regions on cellulose enhances its ability to attract and retain water molecules, further explaining the higher adsorption energy observed.

Discussion

Our findings establish luffa sponge as a highly effective bio-based reinforcement for cementitious composites, yet several limitations of this exploratory study merit acknowledgment. In the atomistic simulations, we simplified the cement hydrate chemistry by using crystalline CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃ phases and thus omitted the amorphous calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) that dominates real hydrated cement. This approximation enabled a tractable modeling of interfacial water interactions but may overlook nuanced effects of C–S–H, leaving some cement–fiber interaction mechanisms to be clarified in future work. Likewise, although distinct failure modes at −196 °C (notably a blocky fracture pattern with diminished fiber constraint) suggest a weakening of the interface at extreme cold, we did not directly characterize the microstructural interface under varying temperature conditions. Advanced in situ experiments (for instance, cryogenic microscopy or temperature-controlled nano-indentation) are needed to confirm how thermal extremes influence interfacial bonding. Furthermore, while our FIB-TEM and DFT analyses revealed a diffuse, graded ITZ unique to the luffa–cement interface, we have yet to quantitatively benchmark this ITZ against those in conventional fiber-reinforced composites (e.g., PVA or steel fibers). Most existing literature reports on ITZ properties are based on parameters such as porosity distribution, hydration degree, or interface thickness. These features may however not directly correspond to the highly porous, bio-based nature of the luffa sponge interface, which forms a more synergistic and diffuse interphase rather than a distinct boundary. In our work, we focused on characterizing the crystallographic differences (via FFT/IFFT), elemental gradients (via EDS), and interfacial water affinity (via DFT), which together demonstrate a functional transition zone. Nevertheless, future measurements on quantitative benchmarks—such as ITZ thickness, hardness gradient, or interfacial mechanical strength—would further support this comparison.

From a practical perspective, the durability and scalability of LSRCC require further evaluation. The long-term stability of natural luffa fibers within the alkaline cement matrix—susceptible to moisture swelling, biodegradation, or alkali attack over time—remains unaddressed in this work. Similarly, the feasibility of integrating luffa sponge reinforcements into large-scale concrete production has not been demonstrated. Aspects such as moisture stability, scalability in concrete production, and the potential for hybridization with mineral fibers are important considerations for practical application. It however should be noted that the luffa sponge was not used in the form of chopped short fibers (as with PVA or steel fibers), but rather as a naturally structured, topologically optimized reinforcement. Its role and function differ fundamentally from conventional fiber-reinforced composites such as UHPC and ECC, and their impact performances merit further comparative investigation. These considerations, while beyond our current scope, are critical for translating LSRCC from laboratory demonstrations to real-world infrastructure.

In sum, our study showcases the promise of luffa sponge as a sustainable reinforcement that imparts outstanding impact resistance across extreme temperatures, and it opens new avenues for developing sustainable cementitious composites—tempered by the need for further materials optimization and durability validation to fully realize their potential.

Conclusions

The development of low-cost, high-performance impact-resistant materials has been a focus in materials science. This study presents LSRCC, utilizing the natural topology-optimized fibers of luffa sponge to toughen cement paste despite its low intrinsic strength. Key findings are as follows:

-

1.

The uniaxial compressive tests reveal a strong synergistic effect between the cement matrix and the luffa sponge, resulting in improved stiffness, strength, and a transition from brittle to ductile failure modes. This confirms the potential of LSRCC as a high-performance impact-resistant material, with the luffa sponge effectively mitigating the inherent brittleness of the cement paste.

-

2.

The impact tests at ambient temperature demonstrated that LSRCC specimens exhibit excellent impact resistance, attributed to the reinforcing effect of the luffa sponge on the cement paste. Under repeated impact loads, the impact force decreased with increasing impact count; however, the specimens retained structural integrity and exhibited ductile failure modes with notable energy dissipation.

-

3.

The progressive damage evolution observed during repeated impacts revealed that the luffa sponge’s spatially entangled fibers effectively mitigate the brittle nature of the cement paste. The increase in energy dissipation per impact, along with the broadening of the plateau stage in force-displacement curves, highlights the suitability of LSRCC for applications involving multiple impact loads.

-

4.

The impact tests across various temperatures demonstrated that LSRCC exhibits excellent adaptability to extreme thermal conditions, maintaining overall structural integrity despite reduced cumulative energy dissipation at high and ultra-low temperatures. At 200 °C and −196 °C, the thermal decomposition of luffa fibers and water crystallization, respectively, led to higher energy dissipation during repeated impacts. These results confirm that the luffa sponge’s reinforcing effect effectively mitigates brittle failure, making LSRCC a reliable and impact-resistant material for extreme environments.

-

5.

The FIB-TEM analysis revealed the existence of a distinct ITZ between the luffa sponge fibers and the cement matrix, characterized by gradual structural and chemical transitions rather than a mechanically inferior zone in the classical sense. Indirect evidence from EDS and DFT suggests enhanced water affinity and hydrogen bonding at the cellulose–cement interface, which promotes synergistic load transfer and contributes to the observed “1 + 1 > 2” effect. Further nano-scale examinations are needed to verify the gradient properties and their temperature dependence.

-

6.

The DFT simulations further confirmed that cellulose exhibits a significantly higher affinity for water molecules compared to the primary cement constituents CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃, due to abundant hydrogen-bonding sites. This strong interaction enhances the ITZ’s performance by creating a gradual strength transition, facilitating efficient load transfer and energy dissipation in LSRCC. The pronounced van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding in the cellulose-water system further highlight the critical role of weak interactions in reinforcing the cement-cellulose interface.

Methods

Materials

In this study, the luffa sponge involves several processing steps. The luffa sponge is sourced from Hunan, China. Initially, mature luffa gourds are harvested at peak ripeness and subjected to natural sun-drying for several days under warm, dry conditions to ensure optimal fiber preservation. Subsequently, the outer epidermal layer is carefully removed to reveal the internal fibrous matrix. The exposed fibers are then thoroughly washed to eliminate residual seeds and impurities, employing a mild alkaline solution to enhance the cleaning efficacy and ensure uniformity of the fibers. Bleaching is not performed to maintain the natural properties of the fibers. After cleaning, the luffa sponge undergoes a secondary mechanical drying phase to inhibit microbial growth, prevent mold formation, and promote optimal pore infiltration and interfacial bonding. Finally, the luffa sponge is cut into cylindrical sections with a height of 35 mm for following testing or processing (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To prepare the LSRCC specimens, ordinary Portland cement (42.5 R) is first mixed with water with a fixed water-to-cement ratio of 0.3 to form a paste, after which the luffa sponge is fully immersed in the cement paste. The LSRCC specimens are casted using cylindrical molds with the dimensions of 75 mm × 35 mm (diameter × height). The composites are then cured for 28 days under standard curing conditions (temperature 20 ± 2 °C and humidity not less than 95%).

Quasi-static uniaxial compression tests

Quasi-static uniaxial compression tests were conducted using an Instron 3367 universal testing machine (Instron Co., Ltd, United States). The cement paste and LSRCC specimens had a diameter of 75 mm and a height of 35 mm, while the dimensions of the luffa sponges varied due to their bio-based nature. The distribution of the luffa sponge dimensions is provided in the Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2. All specimens were clamped between the upper and lower platens of the testing machine and compressed at a constant rate of 1 mm min–1 (strain rate of 4.76 × 10-4) until either the cement was fully crushed or the luffa sponge was fully compacted. Axial force and deformation were continuously recorded. Three replicate specimens were tested under each condition to account for specimen variability.

Drop-weight impact tests

The CEAST-9350 drop-weight impact tester (Instron Co., Ltd, United States) was employed for conducting the impact tests (Supplementary Fig. 3). A high-speed camera Nova S9 made by Photron (resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels, frame rate of 9000 frames per second) was utilized to capture the failure process of the specimens. The test setup is shown in Fig. 3a, b. The drop weight mass was set at 10.8 kg, and three input energy levels (300 J, 500 J and 700 J) were achieved by varying the drop height. For each energy level, three replicate specimens were tested, and repeated impacts were applied at a constant height until specimen disintegration. Force, displacement and energy histories were recorded by embedded sensors in the drop hammer.

Temperature control

For the high-temperature impact tests, the chamber was set to 100 °C and 200 °C, and the specimens were placed inside the heating chamber. Once the chamber reached the target temperature, it was maintained for 2 h before the specimens were removed for impact testing. After each impact, the specimen was returned to the chamber and reheated to the set temperature before the next impact. For the low-temperature tests, the specimens were placed in a dry ice container, ensuring the dry ice fully covered the specimens with a layer of at least 5 cm on both the top and bottom. When the temperature, as measured by the environmental thermometer, reached −78.5 ± 1 °C, the specimens were kept in the container for 5 h before undergoing impact testing. After each impact, the specimens were returned to the container to cool down to −78.5 °C, and immediately after cooling, another impact was conducted. Furthermore, for ultra-low-temperature tests, the specimens were immersed in liquid nitrogen. When the environmental thermometer indicated a temperature of −196 ± 1 °C, the specimens were held for 2 h before being subjected to impact testing. Similar to the previous procedure, the specimens were re-cooled after each impact before the next round of testing.

FIB-TEM characterization

The ITZ specimen was prepared using a FIB technique for TEM analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4). First, an ITZ region of interest was selected and coated with a platinum layer to protect the surface. The surrounding matrix on both sides of the platinum-coated area was then carefully cut using a Ga⁺ ion beam. After the cuts were completed, the slice beneath the platinum layer was extracted from the matrix and transferred to a copper support. The mounted slice was further thinned using focused Ga⁺ ions until its thickness reached approximately 100 nm. The final specimen was then ready for TEM observation. It should be noted that the FIB-TEM analysis was conducted at ambient temperature, as the sample preparation and imaging techniques are not feasible under ultra-low temperature conditions. However, the specimen had already undergone impact loading under ultra-low temperature conditions (–196 °C) prior to FIB-TEM sampling. Since the damage induced by ultra-low temperatures is permanent and not reversible upon returning to room temperature, it is believed that the microstructural features observed through FIB-TEM remain representative of the post-impact state under cryogenic conditions.

DFT simulation details

DFT calculations for periodic material systems were performed with the Vienna Ab initio simulation package (VASP)35 using the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method36. The exchange–correlation function was handled using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) formulated by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)37. The van der Waals (vdW) interactions are described with the DFT-D3 method in Grimme’s scheme38,39. The interaction between the atomic core and electrons was described by the projector augmented wave method. The plane-wave basis energy cutoff was set to 500 eV40,41. The Brillouin zone was sampled with a 3 × 3 × 1 grid centered at the gamma (Γ) point for geometry relaxation. All the slabbed models possessed a vacuum spacing of ≈15 Å sampled, ensuring negligible lateral interaction of adsorbates42. The bottom layers about half of the structure were kept frozen at the lattice position43. All structures were fully relaxed to optimize without any restriction until their total energies converged to <1 × 10-6 eV44,45, and the average residual forces were <0.02 eV/Å46,47. This study adopts CaAl₂O₄ and CaSiO₃ as simplified cement phase models, while omitting C–S–H due to its complex amorphous, non-stoichiometric structure, which makes it challenging to model accurately in first-principles simulations.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Please contact Jingming Cai (jingmingcai@seu.edu.cn) or Zhouhong Zong (zongzh@seu.edu.cn) for further information.

References

Behera, R. P. & Le Ferrand, H. Impact-resistant materials inspired by the mantis shrimp’s dactyl club. Matter 4, 2831–2849 (2021).

Tetsui, T. Identifying low-cost, machinable, impact-resistant TiAl alloys suitable for last-stage turbine blades of jet engines. Intermetallics 168, 108263 (2024).

Zhao C. & Tong, B. Impact dynamic analysis and rubber impact-resistant design of a launcher. Shock Vib. 2023, 1115125 (2023).

Huang, C. Y. & Chen, Y. L. Design and impact resistant analysis of functionally graded Al2O3–ZrO2 ceramic composite. Mater. Des. 91, 294–305 (2016).

Kajita, T., Noro, A., Oda, R. & Hashimoto, S. Highly impact-resistant block polymer-based thermoplastic elastomers with an ionically functionalized rubber phase. ACS Omega 7, 2821–2830 (2021).

Yoo, D. Y. & Banthia, N. Impact resistance of fiber-reinforced concrete–A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 104, 103389 (2019).

Ige, O. E., Von Kallon, D. V. & Desai, D. Carbon emissions mitigation methods for cement industry using a systems dynamics model. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 26, 579–597 (2024).

Rasheed, P. A., Nayar, S. K. & AlFantazi, A. Concrete corrosion in nuclear power plants and other nuclear installations and its mitigation techniques: a review. Corros. Rev. 42, 57–73 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Experimental and numerical study on mechanical behavior of RC shear walls with precast steel-concrete composite module in nuclear power plant. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 56, 2352–2366 (2024).

Possan, E., Ramirez, K. G., de Oliveira Andrade, J. J. & Sandoval, G. F. B. Concrete with wet and calcined water treatment plant waste: macro and micro scale analysis. Waste Biomass Valorization 15, 2611–2623 (2024).

Grengg, C. et al. Advances in concrete materials for sewer systems affected by microbial induced concrete corrosion: a review. Water Res. 134, 341–352 (2018).

Shah, S. P. & Ouyang, C. Mechanical behavior of fiber-reinforced cement-based composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 74, 2727–2953 (1991).

Li, V. C. On engineered cementitious composites (ECC) a review of the material and its applications. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 1, 215–230 (2003).

Lepech, M. D. & Li, V. C. Large-scale processing of engineered cementitious composites. ACI Mater. J. 105, 358 (2008).

De Larrard, F. & Sedran, T. Optimization of ultra-high-performance concrete by the use of a packing model. Cem. Concr. Res. 24, 997–1009 (1994).

Soe, K. T., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, L. Impact resistance of hybrid-fiber engineered cementitious composite panels. Compos. Struct. 104, 320–330 (2013).

Wei, J., Li, J., Wu, C., Liu, Z. & Fang, J. Impact resistance of ultra-high performance concrete strengthened reinforced concrete beams. Int. J. Impact Eng. 158, 104023 (2021).

Cai, J. et al. Effect of temperature on the low-velocity impact behaviors of engineered cementitious composite. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35, 04023167 (2023).

Zaki, R. A., AbdelAleem, B. H., Hassan, A. A. & Colbourne, B. Impact resistance of steel fiber reinforced concrete in cold temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 122, 104116 (2021).

Li, S., Liu, D., Li, W. & Sui, G. Strong and heat-resistant SiC-coated carbonized natural loofah sponge for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 435–444 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. High efficiency solar interfacial evaporator for seawater desalination based on high porosity loofah sponge biochar. Sol. Energy 238, 305–314 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Additively manufactured materials and structures: a state-of-the-art review on their mechanical characteristics and energy absorption. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 246, 108102 (2023).

Shen, J., Xie, Y. M., Huang, X., Zhou, S. & Ruan, D. Mechanical properties of luffa sponge. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 15, 141–152 (2012).

Shen, J., Xie, Y. M., Huang, X., Zhou, S. & Ruan, D. Behaviour of luffa sponge material under dynamic loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 57, 17–26 (2013).

Alvarado-Gómez, E., Tapia, J. I. & Encinas, A. A sustainable hydrophobic luffa sponge for efficient removal of oils from water. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 28, e00273 (2021).

Weng, B. et al. Study on physicochemical properties and potential applications of chemically treated luffa sponge fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 19, 13300–13310 (2022).

Akinyemi, B. A. & Dai, C. Luffa cylindrical fibre as a natural reinforcement for cement composites: a review. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 11, 297–307 (2022).

Querido, V. A., d’Almeida, J. R. M. & Silva, F. A. Development and analysis of sponge gourd (luffa cylindrica L.) fiber-reinforced cement composites. BioResources 14, 9981–9993 (2019).

Han, Y. et al. Application of porous luffa fiber as a natural internal curing material in high-strength mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 455, 139169 (2024).

Menzemer, C. C., Srivatsan, T. S., Ortiz, R., Al-Hajri, M. & Petraroli, M. Influence of temperature on impact fracture behavior of an alloy steel. Mater. Des. 22, 659–667 (2001).

Kang, K. W. & Kim, J. L. Effect of shape memory alloy on impact damage behavior and residual properties of glass/epoxy laminates under low temperature. Compos. Struct. 88, 455–460 (2009).

Banthia, N., Yan, C. & Sakai, K. Impact resistance of fiber reinforced concrete at subnorma temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 20, 393–404 (1998).

Chen, L., Fang, Q., Jiang, X., Ruan, Z. & Hong, J. Combined effects of high temperature and high strain rate on normal weight concrete. Int. J. Impact Eng. 86, 40–56 (2015).

Qiao, Y., Wang, H., Cai, L., Zhang, W. & Yang, B. Influence of low temperature on dynamic behavior of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 115, 214–220 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of Ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Ernzerhof, M. & Scuseria, G. E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 5029–5036 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying a Universal activity descriptor and a unifying mechanism concept on perovskite oxides for green hydrogen production. Adv. Mater. 35, 2305074 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Tuning electron delocalization of hydrogen-bonded organic framework cathode for high-performance zinc-organic batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 5235 (2023).

Cheng, C. et al. Interfacial electron interactions governed photoactivity and selectivity evolution of carbon dioxide photoreduction with spinel cobalt oxide based hollow hetero-nanocubes. Appl. Catal. B 345, 123705 (2024).

Xiao, W., Yoo, K., Kim, J. H. & Xu, H. Breaking barriers to high-practical Li-S batteries with isotropic binary sulfiphilic electrocatalyst: creating a virtuous cycle for favorable polysulfides redox environments. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303916 (2023).

Xiao, W., Kiran, G. K., Yoo, K., Kim, J. H. & Xu, H. The dual-site adsorption and high redox activity enabled by hybrid organic-inorganic vanadyl ethylene glycolate for high-rate and long-durability lithium–sulfur batteries. Small 19, 2206750 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Theoretical design of core–shell 3d-metal nanoclusters for efficient hydrogen-evolving reaction. Energy Fuels 37, 16781–16789 (2023).

Zheng, Q. et al. Cobalt single-atom reverse hydrogen spillover for efficient electrochemical water dissociation and dechlorination. Angew. Chem. 63, e202401386 (2024).

Xu, H. & Guan, D. Exceptional anisotropic noncovalent interactions in ultrathin nanorods: the terminal σ-Hole. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 51190–51199 (2022).

Xu, H., Guan, D. & Ma, L. The bio-inspired heterogeneous single-cluster catalyst Ni100–Fe4S4 for enhanced electrochemical CO2 reduction to CH4. Nanoscale 15, 2756–2766 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2242022k30030 and No. 2242022k30031). The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Mr. Yingfan Wang and Ms. Yujin Yuan for their valuable contributions to the experiments and insightful discussions during the preparation of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and C.Y. conceived the study, designed the experiments, and conducted materials preparation and impact testing. Z.P. assisted with composite fabrication, data curation, and microstructural analysis. H.X. performed the DFT simulations and interfacial mechanism analysis. Yu Zhang and J.M. contributed to experimental work, data processing, and manuscript revision. N.U., Yixia Zhang, E.K., W.X., and A.W. provided guidance on methodology and participated in data interpretation. Z.Z. and J.C. jointly supervised the project, secured funding, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Yang, C., Pei, Z. et al. Luffa sponge as a sustainable reinforcement for impact-resistant cementitious composites. Commun Mater 6, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00985-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00985-y