Abstract

Compositionally-graded amorphous rare earth:transition metal ferrimagnetic thin films offer exciting potential for enabling field-free spin-orbit torque (SOT) switching in spintronic devices. Vertical compositional gradients have previously been developed to enhance SOT efficiency via a proposed transition from out-of-plane (OOP) to in-plane (IP) magnetization to induce Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction that breaks inversion symmetry within the layer. Here, we directly mapped the magnetization orientations within compositionally-graded GdCoFe layers by probing the depth-dependent local effective Gd-magnetization or the local net magnetization using X-ray and neutron reflectivity (PNR), respectively. These methods showed contrast between IP and OOP magnetization zones through the film thicknesses and PNR showed the magnetization compensation point within a graded GdCoFe layer. Transitions from IP to OOP magnetization depended on the local composition, and it was observed that some of these changes do not agree with expectations from the study of films with uniform composition. These results give the spatial distribution of magnetization and hence the anisotropy, essential for understanding and optimising field-free SOT switching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferrimagnetic (FIM) materials, characterized by two magnetic sublattices with opposing magnetizations, have long generated significant interest for fundamental research and applications due to their distinctive magnetic properties1,2,3,4 and more recently for their emerging potential in spintronics5,6,7. Unlike ferromagnets, which exhibit large magnetization resulting in stray fields, and antiferromagnets that have undetectable net magnetization, FIMs maintain a small, yet measurable net magnetization, which in spintronics enables efficient electrical readout8,9,10. The rapid advancement of spin-orbit torque (SOT) research has further driven interest in FIMs, particularly due to their ultrafast switching behavior8,11,12, arising from exchange-dominated high-frequency magnetization dynamics similar to those found in antiferromagnets.

Among FIM systems, rare earth-transition metal (RE:TM) alloys have been a key focus for their compositionally tunable magnetic behavior. These alloys exhibit antiferromagnetic coupling between the RE and TM magnetic sublattices, which each have different temperature dependencies that results in compensation points—specific temperatures and, at a fixed temperature, specific compositions at which the net magnetization or angular momentum vanishes1,5. Near compensation, enhancements in SOT efficiency13 and Gilbert damping14 have been observed, enabling effective control of domain wall dynamics15. Notably, perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) has been reported within specific RE concentration ranges near the compensation point, further advancing the potential of RE:TM alloys for high-density data storage applications16,17,18.

Recent studies have shown that nominally uniform RE:TM ferrimagnetic alloys can exhibit naturally occurring compositional gradients through the film thickness, strongly influencing their magnetic and spintronic properties19,20,21,22,23,24, as well as their amorphicity23,25. One remarkable effect arising from such gradients is the gradient-driven Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (g-DMI), observed in naturally graded GdCoFe26 and GdCo alloys27, as well as in intentionally graded ferromagnet-nonmagnet alloys28. DMI breaks inversion symmetry and stabilizes chiral spin textures such as domain walls and skyrmions29,30,31,32. Combined with SOT, DMI has demonstrated potential for enabling field-free deterministic SOT switching33,34,35,36.

Building on these observations, recent experiments have investigated SOT switching in RE:TM systems with deliberately controlled vertical composition gradients37,38,39,40,41, demonstrating field-free SOT switching in systems such as CoTb37 and GdCoFe41. In these studies, it was inferred that a vertical compositional gradient approaching the compensation point in RE:TM ferrimagnetic thin films induced a transition from in-plane (IP) to out-of-plane (OOP) magnetization - or even a canted configuration - thereby promoting the formation of bulk g-DMI. Zheng et al.37 also indicated that bulk g-DMI shares the same symmetry as interfacial DMI in nonmagnetic/ferromagnetic (NM/FM) bilayers, while theoretical work42 has proposed domain wall (DW) nucleation, aided by edge spin canting, as the mechanism through which g-DMI enables field-free SOT switching, mirroring interfacial-DMI-driven processes33,35,43. However, direct experimental verification of the proposed spatial distributions of IP and OOP magnetized regions within such compositionally-graded RE:TM films remains an open challenge.

In this study, the anisotropy of the magnetization was mapped through the thickness of compositionally-graded GdCoFe alloy thin films using X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity (XRMR) and polarized neutron reflectivity (PNR). XRMR measurements at the Gd L3 edge reveal a complex depth-dependent variation in the magnetization orientation of the RE sublattice, suggesting the presence of non-collinear magnetic configurations within the RE layer. Reversing the Gd gradient reversed the magnetization profile and highlighted the influence of adjacent layers, particularly the Pt interface, which may enhance canting via DMI. PNR analysis identified the compensation point within the graded layer separating the RE-rich and TM-rich regions as well as showing sharp transitions of IP to OOP magnetizations dependent on Gd concentration gradients. Using these techniques on a series of specifically designed samples demonstrated the mapping of the magnetic depth profiles of either the RE sublattice or the net magnetization, enabling the exploration of the regions within compositionally-graded RE:TM alloys thin-films with IP and OOP magnetic anisotropies and locating the region of magnetic compensation within a single graded layer.

Results and Discussion

Gd concentration dependence of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in uniform films

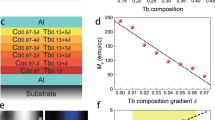

First, to provide a basis for later analysis, a series of nominally uniform RE:TM thin-films were grown by sputtering (see Methods) with different Gd concentrations to determine the range over which PMA occurs. Magnetic measurements were undertaken using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) (see Methods). Figure 1a, b show room-temperature VSM hysteresis loops of \({{\rm{Pt}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{30}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{70})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(40\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\) and \({{\rm{Al}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{10}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{90})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(10\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\) stacks (x is the Gd atomic percentage), respectively, measured with the applied field IP and OOP. Easy axis behavior is identified by a sharp, high remanence, square-shaped loop, whereas hard axis measurements exhibit largely anhysteretic, S-shaped loops saturating at a higher field. Representative loops for both multilayered systems shows the onset of PMA-dominated behavior in each case, where the easy axis is observed in OOP field measurements. The saturation magnetization, Ms, extracted from these loops is plotted as a function of Gd concentration in Fig. 1c, d. The PMA-dominated regions, indicated by the shaded background, are estimated to lie between 23 and 24 at.% Gd for the Pt-seeded 40 nm films, and between 23 at.% and 26 at.% Gd for the Al-seeded 10 nm films, which are in the vicinity of the expected compensation point16,17.

a Room-temperature vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) hysteresis loops for Pt(5 nm)/GdCoFe(40 nm)/Al(7 nm) films with Gd concentrations of 19 at.% and 23 at.% and (b) for Al(5 nm)/GdCoFe(10 nm)/Al(7 nm) films with Gd concentrations of 20 at.%, 26 at.% and 30 at.%. In both panels, the upper plots show full loops up to saturation fields, while the lower plots present zoomed-in loops between -0.1 T and 0.1 T. c Saturation magnetization (Ms) versus Gd concentration extracted from the unnormalized loops in a, and d, corresponding data extracted from b.

Identifying the PMA-dominated compositions of uniform films provides a critical foundation for interpreting the results from compositionally-graded GdCoFe systems. This allows the graded samples—where the Gd concentration varies continuously through the film thickness—to be compared against known magnetic behavior in uniform films. In particular, the compositions around the compensation points and regions of OOP anisotropy observed in XRMR and PNR measurements can be directly correlated with the PMA windows identified here. This correlation enables a layer-resolved interpretation of the graded films, offering insight into how spatial variation in Gd concentration tunes the local magnetic anisotropy and net magnetization.

Spatial variation of Gd moments in compositionally-graded GdCoFe films

Two compositionally-graded systems were grown on a Pt underlayer by sputtering with a Gd concentration range spanning 19−24 at.% for both positive ( ∇ Gd > 0) and negative ( ∇ Gd < 0) gradient directions. The ∇ Gd > 0 sample has a Gd concentration of 19 at.% at the bottom interface, which gradually increases to 24 at.% at the top interface with the Al capping layer, as shown schematically in Fig. 2a. These samples were specifically designed for XRMR measurements, with the material selection and thicknesses of the under and capping layers, and the thickness of the magnetic layer, carefully optimized in advance using GenX simulations. This design ensures that the magnetic asymmetry ratio fringes appear in the low scattering vector Q range, where the signal-to-noise ratio is maximised. The elemental distribution within the GdCoFe layer is confirmed by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) (see Methods) and shown for ∇ Gd > 0 in Fig. 2b. The Gd concentration gradually increases through the thickness, while Co and Fe exhibit gradients in the opposite direction. The ∇ Gd < 0 sample was grown with the same structure, but the Gd gradient was reversed. The SIMS profile for the ∇ Gd < 0 sample is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1b. Figure 2c shows the room-temperature magnetic hysteresis loops of the ∇ Gd > 0 sample, where the loops measured with OOP and IP fields are similar; while the observation of hysteretic behavior with IP and OOP fields confirms the presence of both in-plane and PMA components. The hysteresis loop for the ∇ Gd < 0 sample, shown in Supplementary Fig. 1c, exhibits more pronounced PMA behavior.

a Schematic of the ∇ Gd > 0 sample grown with the nominal structure \({{\rm{Pt}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{30}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{70})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(40\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\). The gradient color block in the GdCoFe layer serves as a guide to the eye, indicating a Gd concentration gradient from 19−24 at.%, increasing from the bottom to the top interface. b Secondary ion mass spectrometry profile of the ∇ Gd > 0 sample showing the elemental distribution through the GdCoFe layer. The Gd profile, shown as blue squares, confirms a positive gradient of Gd concentration through the layer, while Co and Fe, shown as green circles and black triangles respectively, exhibit an opposite gradient. c VSM magnetic hysteresis loop of the ∇ Gd > 0 sample measured at room temperature under IP and OOP magnetic fields. The inset displays the full measurement range showing saturation.

Quasi-static macroscopic magnetometry techniques, such VSM, provide an average magnetization response across the entire sample. For uniform systems, this average can indicate the predominant magnetization direction. However, in compositionally-graded systems, where both local magnetization and anisotropy vary with alloy concentration, interpreting VSM results becomes speculative. XRMR enables simultaneously resolving of the structural and magnetic depth profiles. By tuning circularly polarized X-rays to the Gd L3 edge, analysis of XRMR enables depth-resolved and Gd-specific magnetic sensitivity in terms of scattering length densities (SLDs)23. The XRMR measurements (see Methods) were conducted under a 0.1 T IP applied field, where only the IP magnetized regions of the layer are expected to be saturated along the field direction, while the PMA regions would be canted by the IP field or remain essentially oriented OOP. Since the absorption of the X-ray beam is sensitive only to the magnetization component parallel to the beam polarization (i.e. the IP component), the measurement provides magnetization contrast between the IP and OOP regions of magnetization through the layer thickness.

The XRMR data for the ∇ Gd > 0 sample are shown in Fig. 3a and b, along with the best-fit simulations. The specular reflectivity in Fig. 3a contains structural information, while the asymmetry ratio (AR) data provides magnetic sensitivity. Both datasets were fitted simultaneously using the GenX code44. Multiple simulations were carried out for different initial parameter values to generate uncertainties in the resulting scattering length density (SLD) profiles. The structural SLD is plotted in Fig. 3b as a function of depth and compared with the Gd composition profile obtained from SIMS. The structural SLD reveals the electron density profile, with distinct Pt and Al layers on either side of the GdCoFe film. The Al capping layer exhibits signs of oxidation, resulting in a less well-defined SLD profile. While the SIMS data clearly show a Gd concentration gradient across the layer, the structural SLD does not exhibit such a large variation, as the overall density of GdCoFe remains nearly constant as the Gd concentration changes from 19−24 at.%, due to the similar mass densities of the constituent elements. The XRMR data and structural SLD for the ∇ Gd < 0 sample show similar behavior and are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

a XRMR specular reflectivity and b asymmetry ratio (AR) data measured at the Gd L3-edge for the ∇ Gd > 0 sample, where solid black lines represent the best-fitting model. c Structural scattering length densities (SLD) (red dots) obtained from the best-fitting simulation, plotted alongside the Gd composition profile (blue squares) from SIMS as a function of layer thickness.

Figure 4a shows the Gd magnetization profile through the layer in the ∇ Gd > 0 sample, presented as a magnetic SLD obtained from repeated fitting simulations using GenX, where the error bars indicate the variability in the best fitting solution. The elemental SIMS profile of Gd, plotted with the magnetic SLD, reveals a linear increase in Gd concentration, while the in-plane Gd magnetization rises non-linearly, peaking at around 22 atomic %. Beyond this point, the in-plane Gd magnetization signal decreases rapidly, approaching zero toward the interface with the Al capping layer in the region of 22−24 at.% Gd located between 30 and 40 nm in depth. Despite the increasing Gd concentration, the in-plane Gd magnetization decreases, likely due to moments rotating perpendicular to the beam polarisation (and applied field), indicating regions with different anisotropies. The expected PMA-dominated region confirmed between 23-24 at.% Gd shown in Fig. 1c agreed with magnetic SLD profile shown in Fig. 4a.

a, c Magnetic scattering length densities (SLD) (red dots) obtained from the best-fitting simulations of XRMR data measured at the Gd L3-edge for the ∇ Gd > 0 and ∇ Gd < 0 samples, respectively, plotted alongside the Gd composition profile (blue squares) from SIMS as a function of layer thickness. The magnetic SLDs were extracted from repeated simulations, with the variation among profiles providing the error bars shown. b Calculated Gd moment angle with respect to the applied field as a function of depth and Gd composition within the GdCoFe layer. The stacks of red arrows alongside the angle graphs visually indicate the Gd moment directions through the layer, assuming no in-plane orthogonal components. The different colored background of the blocks serves as a visual guide to the Gd concentration gradient through the layer.

The Gd magnetization is expected to be proportional to the local atomic fraction of Gd throughout the GdCoFe layer. Since XRMR is only sensitive to the moments along the x-ray axis, the measured magnitude of the Gd magnetic SLD represents the cosine projection of this moment along the measurement axis (and the applied field). By comparing the expected total Gd magnetization (using the elemental SIMS Gd profile as a proxy) with the resulting Gd magnetic SLD, the angle of Gd magnetization was determined. The resulting angle is plotted as a function of magnetic layer depth in Fig. 4b, left panel. The schematic arrows along the side of the plot approximate the Gd magnetization directions throughout the layer, showing in the region from 23 at.% to 24 at.% that the magnetization is orthogonal to the IP field, indicating PMA. Surprisingly, in the 19−22 at.% Gd region, where IP alignment is expected, the moments are not fully aligned with the applied field. In this region, the observed angle might not indicate canting toward the OOP direction but could suggest canting in the IP orthogonal plane, although distinguishing between these cases is non-trivial and may also involve some non-colllinearity or sperimagnetism45,46,47 of the Gd moments.

The Gd magnetization profile for the ∇ Gd < 0 sample is shown in Fig. 4c, with the corresponding Gd moment angle, calculated in the same manner as for the ∇ Gd > 0 sample, displayed in the right panel of Fig. 4b. Overall, the Gd magnetization variation and the orientation angles relative to the applied field exhibit a reversed trend through the thickness, as expected for the reversed Gd profile. Both samples show a transition region where the magnetization changes from in-plane to out-of-plane over ~12 nm thickness within the RE:TM layer, with a compositional change from 22 at.%−24 at.% of Gd. However, different behavior is observed in the IP region. In the ∇ Gd > 0 sample, the IP region is located near the Pt interface, while in the ∇ Gd < 0 sample, it is closer to the Al interface. This difference may result in distinct canting angles of the Gd moments, as the Pt interface can induce interfacial DMI48,49,50, leading to increased canting and more complex spin textures near the Pt interface compared to the Al interface. This final point highlights the relevance of the adjacent layers on the magnetization orientation.

The schematic diagrams with arrows in Fig. 4b are provided as visual guides, illustrating the estimated average magnetization orientation at various positions through the sample thickness. These diagrams do not imply any knowledge or assumption of chirality.

Depth-resolved magnetization profiles from polarized neutron reflectivity in GdCoFe graded films

While XRMR provides the magnetic profile specific to a single sublattice, in this case Gd, it is also relevant to investigate the net magnetization profile through such compositionally-graded layers. Here, this was achieved using the PNR technique (see Methods). A key advantage of neutrons is that they possess intrinsic spin, which interacts with local magnetic induction within materials, allowing PNR to locally probe the magnetization. Both ∇ Gd > 0 and ∇ Gd < 0 XRMR samples have Gd concentration ranging from 19−24 at.%, but in opposite gradient directions. Based on the uniform reference samples shown in fig.1(a) and (c), the net saturation magnetization decreases as the Gd concentration approaches the magnetization compensation point around 24 at.% of Gd. This would introduces challenges in PNR analysis, as any reduction in the magnetic profile could be interpreted either as a result of OOP magnetization alignment or simply due to the intrinsic decrease in magnetization caused by increasing Gd concentration. To address this potential ambiguity, a further set of samples was prepared with the structure \({{\rm{Al}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{10}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{90})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(10\,{{\rm{nm}}}) \setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\), optimized for PNR. Figure 5 shows a schematic of the sample structure and IP and OOP magnetic hysteresis measurements. These samples featured a broader range of Gd concentrations compared to those used in the XRMR study, targeting the anisotropy regions below, around, and beyond the compensation point. As shown in Fig. 1d, the expected PMA-dominated region lies between 23 and 26 at.% Gd. To cover this range, two gradient samples were grown: ∇1Gd > 0, with Gd varying from 16−40 at.%, as shown in Fig. 5a, and ∇2Gd > 0, with Gd ranging from 16−50 at.%.

a Schematic of the ∇1Gd > 0 sample with a structure of \({{\rm{Al}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{10}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{90})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(10\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\), where the Gd concentration spans from 16−40 at.%. b, c Magnetic hysteresis loops of the ∇1Gd > 0 and ∇2Gd > 0 samples, respectively, measured by VSM at room temperature. The ∇2Gd > 0 sample was grown with the same structure as ∇1Gd > 0, but with a Gd concentration gradient from 16−50 at.%, both with positive gradients. Insets show full-range loops demonstrating saturation.

The PNR data for the ∇1Gd > 0 sample are shown in Fig. 6a, b, displaying both spin-up and spin-down channels, measured at two different IP magnetic fields, 0.2 T and 3 T, respectively. The spin asymmetry ratios obtained from the experimental and simulated reflectivity curves for both fields are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The PNR data and corresponding spin asymmetry ratio for the ∇2Gd > 0 sample are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4. Measurements at low and high fields provide magnetic contrast between in-plane and out-of-plane components, as the magnetization is fully in-plane at 3 T. Simultaneous refinement of both datasets, constrained by the structural profile, improves the robustness of the fit. The data were fitted using a slab model in the Refl1D code51,52, across three different wavelength bands to account for the varying Gd absorption. To model the graded concentrations within the GdCoFe layer, the fitting procedure employed multiple sublayers of GdCoFe, each with different initial atomic concentrations for the constituent elements. The evolution of the figure of merit for different numbers of sublayers used in the fitting is presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The resulting structural SLD profiles are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6. The real part of the structural SLD exhibits a decreasing trend along the film thickness, as expected. Although CoFe and Gd have similar mass densities, neutron scattering is nucleus-specific and does not scale with atomic number (Z), unlike X-rays53. Therefore, the neutron SLD contrast between CoFe and Gd is more pronounced, making the structural gradient much clearer (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Notably, the Gd concentration gradient in these PNR samples is broader than that in the XRMR samples. The real and imaginary parts of the structural SLD of the PNR analysis for the ∇1Gd > 0 sample are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6a, b, respectively. The real part is dominated by contributions from Co and Fe as their values are significantly higher than that of Gd. Consequently, the real part of the structural SLD follows the gradient of Co and Fe, which agrees very well with Co and Fe elemental profile from SIMS in Supplementary Fig. 6a, while the imaginary part is dominated by neutron absorption by Gd and thus effectively reflects the Gd gradient within the RE:TM layer. This is also in good agreement with the elemental distribution of Gd measured by SIMS shown in Supplementary Fig. 7a.

Figure 7a presents the depth-resolved net magnetization profile of the ∇1Gd > 0 sample, obtained from fitting the PNR data using Refl1D. The yellow squares represent the magnetic SLD at 3 T, corresponding to full alignment of the magnetization with the applied field. From the lower Al interface, the magnetization rises rapidly as the RE:TM layer is established and then falls as the increasing Gd opposes the antiferromagnetically aligned TM dominated magnetization, which continues to a minimum at the magnetic compensation point, where the contributions from the rare-earth and transition-metal sublattices approximately cancel out. With further increases of the Gd, the net magnetization increases as the Gd sublattice dominates the magnetization and this continues until the interface with the upper Al layer at which magnetization falls rapidly. This saturated state behavior shows clearly the compositional variation and compensation point behavior of the magnetization through the film thickness.

a, c Magnetic scattering length densities obtained from the best-fitting Refl1D simulations of PNR data for the ∇1Gd > 0 and ∇2Gd > 0 samples, respectively. The magnetic SLDs represent net magnetization profiles at both saturation field (3 T, shown as yellow squares) and lower field (0.2 T and 0.8 T, shown as green circles for ∇1Gd > 0 and ∇2Gd > 0, respectively), plotted alongside the Gd composition profile (blue triangles) from SIMS as a function of layer thickness. b Calculated net magnetization angle with respect to the applied field as a function of depth and Gd composition within the GdCoFe layer. The stacks of red arrows alongside the angle graphs visually indicate the net magnetization orientation through the layer, assuming no in-plane orthogonal components. The colored background blocks serve as a visual guide to the Gd concentration gradient across the layer.

With a small applied field, the neutron reflectivity reveals the intrinsic distribution of the magnetization orientations through the compositionally-graded alloy layer. The green circles show the magnetic SLD measured in 0.2 T, reflecting only the IP components aligned with the neutron polarisation, as PNR is sensitive solely to this component and cannot distinguish OOP magnetization from IP components orthogonal to the neutron spin polarisation vector. However, the magnetic hysteresis loops in Fig. 1b indicate regions within the Gd concentration gradient where OOP magnetization is likely, consistent with the features observed in the magnetic depth profiles. From the lower Al interface up to a total multilayer thickness around 10 nm the magnetic SLD is zero, indicating OOP magnetization in this region. At higher Gd concentrations the magnetization is IP and follows the saturated data. This reveals a spatial variation in magnetic anisotropy from OOP to IP. Within the film thickness, the upper Gd concentration of the OOP magnetized region occurs around the compensation point.

The angle of the net magnetization through the layer thickness was estimated by comparing the data in the 0.2 T and 3 T profiles, see Fig. 7b, left panel. The red arrows on the side of the graph indicate the approximate magnetization directions through the layer at low field, highlighting that in the region between 16 and 26 at.% Gd, the magnetization is oriented orthogonal to the in-plane applied field, indicating the presence of PMA. This is followed by the transition from OOP to IP magnetization between 26−30 at.% over 1.8 nm of thickness. This observation contrasts with Fig. 1d, where uniform samples with 20 at.% to 22 at.% Gd in the same structure exhibits IP magnetization. Based solely on the behavior of uniform samples, the region of 16 to 22 at.% Gd would typically be associated with IP magnetization. The extended PMA-dominated region downs to 16 at.% Gd in the graded film suggests a strong interfacial influence from the Al layer on the GdCoFe, enhancing perpendicular anisotropy. Supporting evidence comes from another gradient sample grown with a Gd concentration range of 16 to 30 at.% (denoted as ∇0Gd > 0), which exhibited pronounced PMA in OOP VSM hysteresis loops (see Supplementary Fig. 8), confirming the dominant PMA within this composition range. This discrepancy highlights that the magnetization behavior in graded systems cannot be directly inferred from uniform samples, due to the influence of compositional gradients and interfacial effects.

Comparable plots and analysis for the ∇2Gd > 0 sample of the magnetic SLD and net magnetization angles are shown in Fig. 7c and in the right panel of Fig. 7b, respectively. As expected, the net magnetization profile is broader due to the extended Gd concentration range (16−50 at.%), which is also reflected in the increased scale of the magnetic SLD compared to the ∇1Gd > 0 sample. Notably, the compensation point and OOP regions are shifted lower in the layer, because the same film thickness was used with a larger Gd range. This shift is clearly visualized in Fig. 7b, where the OOP region for the ∇2Gd > 0 sample appears ~1.2 nm deeper than in the ∇1Gd > 0 sample. It is also evident that the transition between IP to OOP magnetization regions is much sharper (<1 nm) and occurs at higher Gd concentrations for the ∇2Gd > 0 sample compared to ∇1Gd > 0, both of which may be important for exchange-spring behavior and field-free SOT switching. The sharp IP to OOP transition observed in both ∇1Gd > 0 and ∇2Gd > 0 samples is surprising considering the linear compositional gradients. The transition zone is consistent with the narrow compositional region around the compensation point16,17, but the fact that OOP magnetization is supported in Gd compositions down to 16 at.% is unexpected. This finding constitutes one of the significant outcomes of this study, as such magnetization behavior is not observed in uniform composition samples, see Fig. 1b and d.

Compared to the ∇ Gd > 0 and ∇ Gd < 0 samples measured using XRMR, the PNR-measured ∇1Gd > 0 and ∇2Gd > 0 samples exhibit significantly sharper transition regions between IP and OOP magnetization. This observation is consistent with the fact that the PNR samples have a reduced thickness, approximately one-quarter that of the XRMR samples, and were grown with a much wider range of Gd concentration gradients. As a result, the magnetization transitions are much narrower in the PNR samples, while those observed via XRMR are comparatively broader.

These results provide, to the best of our knowledge, the first direct, depth-resolved experimental insight into the spatial distribution of in-plane and out-of-plane magnetization across compositionally-graded GdCoFe films. By correlating XRMR- and PNR-derived magnetic profiles with compositional gradients, this work provides insights for the g-DMI formation in RE:TM ferrimagnets, which has been suggested to facilitate the field-free SOT switching37,41. These findings bridge the gap between theoretical predictions42 and experimental evidence, offering a clearer path toward engineering vertical gradients and tailored magnetic anisotropy for spintronic devices.

Conclusions

In conclusion, using XRMR and PNR measurements, the magnetization profiles of the local Gd magnetization and the local net magnetization through the thickness of compositionally-graded GdCoFe alloy films were mapped, respectively. XRMR measurements of 40 nm thick GdCoFe films with Gd concentrations varying from 19−24 at.% showed variations from IP to OOP magnetization orientations and more complex angular variations that may indicate sperimagnetism. When the Gd concentration gradient was reversed, the Gd-magnetization profile was reversed overall, but also showed distinct differences that indicate the significance of the different layers above and below the GdCoFe film. PNR measurements of samples composed of 10 nm thick GdCoFe layers with Gd concentrations ranging from 16−40 at.% and 16−50 at.% showed the variations of the local magnetization through the thickness. Measurements at magnetic saturation showed a clear magnetic compensation point within the films, and low-field measurements showed a clear transition from IP to OOP magnetization as a function of Gd concentration through the film thickness. Analysis also showed that the transition for IP to OOP magnetized regions was sharp and depended on the Gd concentration gradient.

Methods

Sample growth and characterizations

A series of uniform RE:TM samples were fabricated by magnetron co-sputtering onto oxidized Si substrates, with the structure \({{\rm{Pt}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{30}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{70})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(40\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\), where x = 19, 22, 23, and 24 at.%. The base pressure was maintained at 10−7 Torr, using high-purity Ar as the sputtering gas at a working pressure of 3 × 10−3 Torr. The average composition of the RE:TM layers was confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). Different structures of \({{\rm{Al}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{10}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{90})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(10\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\) were also grown with the same precodures where x = 20, 26, 28, and 30 at.%. These samples were used to identify the concentration range in which PMA is observed, as determined by VSM.

A graded GdCoFe layer was also prepared using a similar structure to the uniform samples. The 40 nm GdCoFe layer was divided into ten sublayers, each with a different Gd concentration ranging from 19 to 24 atomic %. The gradient was achieved by fixing the CoFe deposition rate while progressively increasing the Gd rate across the sublayers (each ~4 nm thick). SIMS confirmed the composition gradient, revealing a bottom sublayer composition of \({{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{19}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{30}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{70})}_{81}\) and a top sublayer composition of \({{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{24}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{30}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{70})}_{76}\). This graded sample was labeled as ∇ Gd > 0, the reversed gradient sample, ∇ Gd < 0 which has been confirmed with SIMS as well.

Set of graded samples was fabricated using the same gradient method but with a different structure: \({{\rm{Al}}}(5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\setminus {{{\rm{Gd}}}}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{({{{\rm{Co}}}}_{10}{{{\rm{Fe}}}}_{90})}_{1-{{\rm{x}}}}(10\,{{\rm{nm}}}) \setminus {{\rm{Al}}}(7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\), where x = 16 at.% in the bottom sublayer and 40 at.% in the top, labeled ∇1Gd > 0. Another sample with identical structure but Gd concentration spanning from 16 to 50 at.% and 16 to 30 at.%, labeled as ∇2Gd > 0, ∇0Gd > 0, respectively. The composition gradient of these samples was also confirmed by SIMS.

All depositions were performed at room temperature, with no post-deposition annealing.

Quasi-static magnetometry

Vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) measurements were performed at room temperature using a Lake Shore VSM at the School of Physics, Engineering and Technology, University of York, with a maximum applied field of ~1.5 T. The IP and OOP hysteresis loops were obtained by rotating the sample holder to align either parallel or perpendicular to the applied magnetic field direction.

International facility measurements and data analysis

XRMR measurements were conducted at room temperature on the XMaS beamline at the ESRF54, using circularly polarized X-rays tuned to the Gd L3-edge (7.24 keV) in a θ − 2θ scattering geometry. An avalanche photodiode detector recorded the scattered intensity under an applied in-plane magnetic field of 0.1 T, alternated between parallel and antiparallel orientations relative to the incident beam. The average specular reflectivity, I = (I+ + I−)/2, provided structural information, while the magnetic asymmetry ratio, ΔI = (I+ − I−)/(I+ + I−), was sensitive to the Gd magnetic moments. Data were analysed using the magnetic reflectivity module in GenX44, which incorporates a recursion matrix algorithm55 and accounts for the polarisation-dependent refractive indices, enabling simultaneous fitting of structural and magnetic scattering length density (SLD) profiles.

PNR measurements were carried out on the POLREF beamline at the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source56 to obtain the net magnetization depth profiles. Measurements were performed under applied fields of 3 T and lower fields (0.2 T for ∇1Gd > 0 and 0.8 T for ∇2Gd > 0) for both neutron spin polarisations. The nuclear SLD (structural) and magnetic profiles were extracted by fitting the reflectivity data using the Refl1D software package51,52, with simultaneous fitting across three wavelength ranges to account for Gd’s strong energy-dependent neutron absorption. Different fitting models were employed by varying the number of magnetic sublayers, with the optimal model selected based on the minimum figure of merit. Further details on the fitting model evolution and comparison of figures of merit can be found in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Data availability

The supporting data for this paper are openly available from the Durham University data archive (https://doi.org/10.15128/r2tb09j5732).

References

Tao, L., Gambino, R., Kirkpatrick, S., Cuomo, J. & Lilienthal, H. Magnetic properties of amorphous GdCo films. AIP Conf. Proc. 18, 641–645 (1974).

Mimura, Y., Imamura, N. & Kushiro, Y. Hall effect in rare-earth–transition-metal amorphous alloy films. J. of Appl. Phys. 47, 3371–3373 (1976).

Kryder, M. H. Magneto-optic recording technology. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 3913–3918 (1985).

Harris, V., Aylesworth, K., Das, B., Elam, W. & Koon, N. Structural origins of magnetic anisotropy in sputtered amorphous Tb-Fe films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 1939 (1992).

Finley, J. & Liu, L. Spintronics with compensated ferrimagnets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 110501 (2020).

Kim, S. K. et al. Ferrimagnetic spintronics. Nat. Mater. 21, 24–34 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ferrimagnets for spintronic devices: from materials to applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 011301 (2023).

Kim, K.-J. et al. Fast domain wall motion in the vicinity of the angular momentum compensation temperature of ferrimagnets. Nat. Mater.16, 1187–1192 (2017).

Zheng, Z. et al. Enhanced spin-orbit torque and multilevel current-induced switching in W/Co-Tb/Pt heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044032 (2019).

Finley, J. & Liu, L. Spin-orbit-torque efficiency in compensated ferrimagnetic cobalt-terbium alloys. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 054001 (2016).

Cai, K. et al. Ultrafast and energy-efficient spin–orbit torque switching in compensated ferrimagnets. Nat. Electron. 3, 37–42 (2020).

Siddiqui, S. A., Han, J., Finley, J. T., Ross, C. A. & Liu, L. Current-induced domain wall motion in a compensated ferrimagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 057701 (2018).

Seung Ham, W. et al. Temperature dependence of spin-orbit effective fields in Pt/GdFeCo bilayers. Appl. Phys. Let. 110, 242405 (2017).

Stanciu, C. et al. Ultrafast spin dynamics across compensation points in ferrimagnetic GdFeCo: the role of angular momentum compensation. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 73, 220402 (2006).

Okuno, T. Spin-transfer torques for domain wall motion in antiferromagnetically-coupled ferrimagnets. In Magnetic Dynamics in Antiferromagnetically-Coupled Ferrimagnets: The Role of Angular Momentum, (ed. Okuno, T.) 75 (Springer, 2020).

Taylor, R. & Gangulee, A. Magnetization and magnetic anisotropy in evaporated GdCo amorphous films. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 4666–4668 (1976).

Ishibashi, M. et al. Ferrimagnetic compensation and its thickness dependence in TbFeCo alloy thin films, Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 022405 (2022).

Ishibashi, M. et al. Decoding the magnetic bit positioning error in a ferrimagnetic racetrack. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq0898 (2024).

Bergeard, N., Mougin, A., Izquierdo, M., Fonda, E. & Sirotti, F. Correlation between structure, electronic properties, and magnetism in CoxGd1−x thin amorphous films. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064418 (2017).

Kudin, S. R., Rozouvan, S. & Staschuk, V. Surface structure of Gd20Co80 alloy. Semicond. Phys. Quant. Electron. Optoelectron 24, 56–63 (2021).

Chanda, A., Shoup, J., Schulz, N., Arena, D. & Srikanth, H. Tunable competing magnetic anisotropies and spin reconfigurations in ferrimagnetic Fe100−xGdx alloy films. Phys. Rev. B 104, 094404 (2021).

Sala, G. et al. Asynchronous current-induced switching of rare-earth and transition-metal sublattices in ferrimagnetic alloys. Nat. Mater. 21, 640–646 (2022).

Inyang, O. et al. Non-uniform gd distribution and magnetization profiles within GdCoFe alloy thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 122403 (2023).

Kirk, E. et al. Anisotropy-induced spin reorientation in chemically modulated amorphous ferrimagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 074403 (2020).

Inyang, O., Rafiq, A., Swindells, C., Ali, S. & Atkinson, D. The role of low Gd concentrations on magnetisation behaviour in rare earth: transition metal alloy films. Sci. Rep. 10, 9767 (2020).

Kim, D.-H. et al. Bulk Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in amorphous ferrimagnetic alloys. Nat. Mater. 18, 685–690 (2019).

Ko, S. et al. Chiral coupling of two orthogonal magnetizations in a single ferrimagnetic GdCo layer. APL Mater. 11, 081119 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Quantifying the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction induced by the bulk magnetic asymmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 167202 (2022).

Dzialoshinskii, I. Thermodynamic theory of weak ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic substances. Soviet Phys. Jetp-Ussr 5, 1259–1272 (1957).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Je, S.-G. et al. Asymmetric magnetic domain-wall motion by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214401 (2013).

Roessler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Chen, B., Lourembam, J., Goolaup, S. & Lim, S. T. Field-free spin-orbit torque switching of a perpendicular ferromagnet with Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 022401 (2019).

Wu, K., Su, D., Saha, R. & Wang, J.-P. Deterministic field-free switching of a perpendicularly magnetized ferromagnetic layer via the joint effects of the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction and damping-and field-like spin–orbit torques: an appraisal. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 205002 (2020).

Dai, M. & Hu, J.-M. Field-free spin–orbit torque perpendicular magnetization switching in ultrathin nanostructures. NPJ Comput. Mate. 6, 78 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Interface effect on the out-of-plane spin-orbit torque in the ferromagnetic CoPt single layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401018 (2024).

Zheng, Z. et al. Field-free spin-orbit torque-induced switching of perpendicular magnetization in a ferrimagnetic layer with a vertical composition gradient. Nat. Commun. 12, 4555 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. Controllable conical magnetic structure and spin-orbit-torque switching in symmetry-broken ferrimagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 014045 (2024).

Bhatt, R. C., Ye, L.-X., Lin, J.-H. & Wu, T.-h Temperature-dependence of anomalous hall effect in Ta-(GdFeCo) δ-Ta films with vertical composition gradients. J. Magnet. Magnetic Mater. 589, 171575 (2024).

Zeng, G. et al. Field-free SOT-switching based on a vertical composition gradient of ferrimagnetic alloys. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 4168–4173 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Chiral symmetry breaking for deterministic switching of perpendicular magnetization by spin–orbit torque. Nano lett. 21, 515–521 (2020).

Liang, J., Chshiev, M., Fert, A. & Yang, H. Gradient-Induced Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya Interaction. Nano Lett. 22, 10128–10133 (2022).

Mikuszeit, N. et al. Spin-orbit torque driven chiral magnetization reversal in ultrathin nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 92, 144424 (2015).

Björck, M. & Andersson, G. Genx: an extensible x-ray reflectivity refinement program utilizing differential evolution. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 1174–1178 (2007).

Coey, J. M. D., Chappert, J., Rebouillat, J. & Wang, T. Magnetic structure of an amorphous rare-earth transition-metal alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 36, 1061 (1976).

Chen, D. et al. Noncollinear spin state and unusual magnetoresistance in ferrimagnet Co-Gd. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 014402 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Unconventional magnetoresistance induced by sperimagnetism in GdFeCo. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014421 (2021).

Freimuth, F., Blügel, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Berry phase theory of Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction and spin–orbit torques. J. phys. Condens. Matter 26, 104202 (2014).

Ryu, K.-S., Thomas, L., Yang, S.-H. & Parkin, S. Chiral spin torque at magnetic domain walls. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 527–533 (2013).

Suzuki, D. H., Lee, B. H. & Beach, G. S. Compositional dependence of spintronic properties in Pt/GdCo films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 122401 (2023).

Kienzle, P. et al. Reflectometry Software. https://www.nist.gov/ncnr/reflectometry-software (2017).

Kienzle, P., Krycka, J., Patel, N. & Sahin, I. Bumps 0.0.1.post63+g6318826 Documentation. https://bumps.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (2011).

Sivia, D. S. Elementary Scattering Theory: for X-Ray and Neutron Users Illustrated edition, Vol. 216 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Bikondoa, O. et al. Xmas @ the ESRF. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 377, 20180237 (2019).

Stepanov, S. & Sinha, S. X-ray resonant reflection from magnetic multilayers: recursion matrix algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 61, 15302 (2000).

Science and Technology Facilities Council. Polref Beamline. https://www.isis.stfc.ac.uk/Pages/polref.aspx (2020).

Atkinson, D., Hodgkiss, A., Rianto, D., Hase, T. & Kinane, C. Controlling chiral spin texture in RE:TM ferrimagnetic alloys thin-films by engineering the vertical compositional distribution. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 014045 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Funding is acknowledged from EPSRC for studentships for D.R. and A.W.H. (No. EP/W524426/1), Durham University for B.N. (DU-IAA), and for an Industry Fellowship from the Royal Society for D.A. IF170030. We are grateful to EPSRC for X-ray beam time A28-1-1395 on XMaS, the UK CRG Beamline at the ESRF, and ISIS neutron source for the provision of beamtime RB242002057,58. We also thank Gonzalo Vallejo Fernandez and William Frost for access and support using the VSM at the School of Physics, Engineering and Technology, University of York.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A. initiated the research. DA and TPAH supervised the work. D.A. and D.R. conceptualised the research and methodology under discussion with TPAH. The metallic alloy samples were grown by D.R. V.S.M. characterization was done by D.R. P.P.M. performed the SIMS measurements. D.R., B.N., T.P.A.H., and D.A. undertook the X-ray beamtime, working with L.B. to performed XRMR measurements and data curation. D.R., A.W.H., T.P.A.H. and D.A. were involved in neutron beamtime working with A.J.C. and C.J.K. to performed PNR measurement and data curation. D.R. performed XRMR analysis with guidance from T.P.A.H. and input from D.A. D.R. and AWH performed PNR fitting under guidance of A.J.C. and C.J.K. D.R. and D.A. drafted the original manuscript. All authors were involved in editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Hao Wu and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rianto, D., Nicholson, B., Hodgkiss, A.W. et al. Mapping magnetization orientation within compositionally graded rare-earth transition-metal alloy thin films for spintronics. Commun Mater 6, 264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00987-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00987-w