Abstract

Electrochemical detection of heavy metals in complex matrices, such as biofluids, food, and water, using bismuth-based composites allows for point-of-care diagnostics in healthcare, food safety, and environmental monitoring. However, challenges remain in commercialization, particularly due to electrode fouling and sensitivity loss. This study introduces a robust antifouling coating consisting of a 3D porous cross-linked bovine serum albumin (BSA) matrix and 2D g-C3N4, supported by conductive bismuth tungstate. This composite effectively prevents nonspecific interactions, enhances electron transfer, and maintains 90% of the signal after one month in untreated human plasma, serum, and wastewater. It enables sensitive and multiplexed detection of heavy metals in plasma, serum, and water, providing a simple, stable, and efficient solution for the development of electrochemical sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical sensors based on deposition-stripping analysis are used for economical, highly sensitive, and high-throughput detection of heavy metals, such as the widely commercialized dropping mercury electrode. However, due to the toxicity of mercury, many new analytical materials have been used as replacements, such as bismuth metal1,2,3,4 and bismuth alloys5,6, which have become prominent in this field. These sensors are particularly valuable for multi-point detection in complex matrices like food, blood, and tissue fluids7. To enhance heavy metal detection performance (sensitivity and selectivity), three key strategies have emerged: (1) increasing chelation of target ions on the electrode surface8; (2) improving fixation efficiency of reduced heavy metal atoms via alloy formation9; and (3) mitigating interference from environmental substances (e.g., organic compounds)10. Consequently, research has focused on elucidating chelation mechanisms, optimizing electrodeposited metal fixation, and enhancing electrode antifouling properties11.

Functional material modification is critical for boosting ion chelation and capture12. Conductive materials doped with elements (e.g., sulfur13 and nitrogen14) bearing lone electron pairs are effective: their Coulombic interactions with electro-deficient heavy metals enhance chelation15, enriching ions at the electrode surface for pre-deposition16. Additionally, such materials improve adhesion of electrodeposited metals17, strengthening fixation and overall detection performance18.

Another effective strategy is to use functional materials that can form alloys with heavy metal elements after electrodeposition and reduction19,20,21,22. Bismuth metal exhibits a wide potential window, low background current, and alloy-forming ability comparable to mercury23. However, bismuth films are prone to hydrolysis under alkaline conditions, limiting practical use. This has driven the adoption of bismuth compounds (such as Bi2O324, Bi2WO625, BiVO426, BiFeO327, Bi2CuO428, etc.), whose stable crystal structures balance electrochemical activity and reusability.

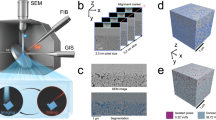

The successful use of bismuth-based surface-modified electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection has been reported in numerous scientific studies29. However, the commercialization of this technology has been limited due to its inability to maintain stable sensing performance in complex media environments. Unlike optical sensing, the challenge in electrochemical heavy metal sensing lies in the electrode configuration and the closed electrical and ionic circuits formed between the instrument and the sample, which are coupled to the interrogation and reading process. As a result, any material that nonspecifically binds to the electrode in a complex sample will reduce both the current and sensitivity. To address the challenge of high-sensitivity, high-throughput detection and analysis of multiple heavy metals in complex samples, we developed a three-dimensional (3D) nanocomposite. This structure integrates BSA crosslinked with conductive two-dimensional nanomaterials to form ion transport channels for heavy metals30. The selected conductive material, 2D g-C3N4 (Fig. 1b), enhances electron transfer to the electrode, improves analytical performance, reduces nonspecific binding, and facilitates the efficient capture of heavy metal ions. We encapsulated the bismuth-based composite within this 3D structure to enhance the fixation and complexation of the target metal ions after electroreduction deposition.

Results

Design and preparation of conductive polymer film electrodes

The preliminary experiments began with the study of conductive cross-linked membranes with antifouling properties (Fig. 1a). Bovine serum albumin and g-C3N4 were used as the main functional monomers, glutaraldehyde served as the cross-linker for polymerization, and flower-like bismuth tungstate was added as a heavy metal co-deposition anchor to the pre-polymerization solution. The above pre-polymerized solution is uniformly dispersed by mixing and ultrasonic treatment, and then immediately dropped onto the electrode surface to form a coating. The performance of the constructed electrochemical sensor was evaluated using cyclic voltammetry, and the electrode was cyclically scanned between oxidation and reduction potentials in a standard potassium ferrocyanide-potassium ferrocyanide redox system. The potential difference (ΔEp) and the corresponding current density of the redox process peak were analyzed to evaluate the electron transfer kinetics at the electrode-solution interface, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of the state of the electrode solid–liquid interface.

a Schematic diagram of a constructed three-electrode electrochemical device, wherein the working electrode of gold is functionally modified with a conductive polymer membrane formed by BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA, with ion transport channels within the polymeric membrane. b Typical cyclic voltammograms showing oxidation and reduction curves of 5 mM ferroc/ferricyanide equimolar solutions for coated electrodes modified with various complexes (left) as well as polymeric film coated electrodes after crosslinking with 5% GA (right). c The electrochemical performance of electrodes with different coatings was evaluated. The bar chart illustrates the average current density of different nanocomposite-coated electrodes before (orange) and after (green) being exposed to 10 mg/mL HSA for 1 day. The line graph represents the final average peak-to-peak distance, based on measurements from five independent electrodes (n = 5). d Cyclic voltammograms of the gold working electrode without any modification (left) and the BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coated electrode (right) in 5 mM equimolar ferric/ferrocyanide solution, with the scan rate set in the range of 0.01–0.1 V s−1. e Oxidation/reduction peak currents (ip) were extracted from the cyclic voltammograms in (d), and the values obtained from five independent electrode experiments were averaged (blocks). These values were then plotted against the square root of the scan rate. The error bars in all figures represent the standard deviation of the mean.

While BSA coating resulted in complete passivation, BSA/Bi2WO6, BSA/g-C3N4, BSA/NH2-rGO, BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4, and BSA/Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO coatings retained 42%, 53%, 49%, 75%, and 68% of the current density, respectively (Fig. 1b, c), partly due to the electron transfer mediated by Bi2WO6, NH2-rGO, and g-C3N4 particles. To evaluate the antifouling properties of these coatings, we measured their performance before and after 1 day of incubation in a 10 mg/mL human serum albumin (HSA) solution. The electrochemical performance of all coatings showed similar decreases, except for BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4 and BSA/Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO. The BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C₃N₄ composite maintained a high current and a low ΔEp, while the BSA/ Bi2WO6 coating exhibited a much larger ΔEp of up to 0.38 V. This indicates that fouling, particularly the blockage of Bi2WO6 pores, restricted the diffusion of iron/ferrocyanide to the electrode surface. The addition of NH2-rGO and g-C3N4 two-dimensional layered materials can slightly alleviate the effect of electrode blockage by biomass, but still cannot eliminate the risk of fouling (Fig. 1c). To address this limitation, glutaraldehyde (GA) was introduced to crosslink BSA and g-C₃N₄ molecules, forming a 3D polymer matrix embedded with conductive nanomaterials. After cross-linking, the composite matrix of this polymer film significantly improved the electrochemical performance of the sensor, indicating that the cross-linking effect enhances the functionality and stability of the material. To explore the anti-fouling research of the electrode in clinical analysis, we considered that after incubating the prepared electrodes in 10 mg/mL HSA for 1 day, the BSA/NH2-rGO/GA, BSA/ Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO/GA, BSA/g-C3N4/GA and BSA/ Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coatings retained 92% and 86%, 94% and 91% of the current density, respectively, and the ΔEp was 218 mV, 229 mV, 128 mV and 190 mV, respectively. To evaluate the mass transfer of ferricyanide/potassium ferrocyanide on the prepared BSA/g-C3N4/GA and BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coating electrodes, voltammograms were measured at different scan rates. The experimental results show that the collected voltammograms are almost consistent with those observed on the bare gold electrode (Fig. 1d). The final experimental results show that the redox current is linearly positively correlated with the square root of the scan rate, which indicates that the electrode surface presents a diffusion-limited process (Fig. 1e).

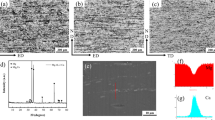

To gain a deeper insight into the mechanism behind the improved electrochemical performance of the polymerized film, the morphology of the coating and its polymerization mechanism were characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The polymer film is formed by using BSA and g-C3N4 as polymerization monomers and GA as a cross-linking agent. The results show that when the GA content in the polymer precursor is low, powdery and dispersed dimers, oligomers, and even a large amount of polymer monomers with incomplete polymerization will be formed under low cross-linking conditions. These particles and molecules are adsorbed on the grooves and pores on the flower-like Bi2WO6 surface through physical interactions such as electrostatic forces (Fig. 2A). After cross-linking of the above-mentioned monomers with an appropriate ratio of GA, a thick porous sponge-like conductive polymer matrix was generated (Fig. 2B), which is similar to the aggregates observed in the previously reported BSA/GA protein antifouling matrix. The BSA/g-C3N4/Bi2WO6/GA coating, formed by introducing polymers to the surface of porous bismuth tungstate, exhibited the most significant microporosity. Notably, the simultaneous enhancement of antifouling performance and electrochemical activity stems from the synergistic effect of its porous structure and the incorporation of bismuth-based materials. Even with a film thickness exceeding 1 μm (Supplementary Fig. 1), the polymer coating retains efficient ion transport and electroreduction capabilities (Supplementary Fig. 2). These macroporosities were mainly contributed by the porous nature of the flower-like bismuth tungstate itself, in which the polymer with ion channels was tightly attached to the bismuth tungstate surface. Unfortunately, the pores of ion migration scale formed by the polymer could not be directly observed.

A Scanning electron micrograph at different scales and elemental mapping of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coated electrodes at low crosslinking degree between BSA and g-C3N4. Two sets of prepared samples were analyzed. B Scanning electron micrographs of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coated electrodes at appropriate cross-linking degrees at different scales and elemental mapping. Two sets of prepared samples were analyzed. C XPS graphs of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA at different crosslinking degrees.

Considering the excellent electrochemical performances exhibited by BSA/NH2-rGO/Bi2WO6/GA and BSA/g-C3N4/Bi2WO6/GA coated electrodes, we hypothesize that the prepared polymer coatings exhibit an extremely small electrode ensemble with ion size-restricted passage, and each ion channel acts as a working electrode for the ion migration scale. Similar behavior was also observed in the previously reported BSA-GA cross-linked protein polymer-coated electrodes31. The coated electrodes showed different cyclic voltammograms according to the size and morphology of the pores in the surface polymer film coating, which was mainly caused by the transmission of electroactive substances on the electrode interface in the polymer film pore channel or pore diffusion. Among them, the performance of macroscopic electrochemistry must take into account the size of the nanoelectrode formed by each pore in the polymer coating, the pore morphology, the distance between pores, the diffusion coefficient of the electroactive substances in the solution, and the scan rate of the electrochemical test30. Generally speaking, at a faster electrochemical scan rate, the diffusion of the electroactive substances in each hole in the polymer membrane is often independent and dominant, so the electrochemical behavior of the electrode scan presents a planar diffusion curve; at a slower scan rate, the behavior of the electroactive substances at the electrode interface is dominated by diffusion, and this diffusion layer will extend beyond the pores of the polymer, so the cyclic voltammogram of the electrode presents an S shape, and its response curve shows a semi-infinite radial diffusion model, which is due to the comprehensive superposition of the S-shaped voltammograms of all pore electrodes on the total current. At very slow scan rates, the diffusion-dominant effect caused, or the distance between the pores of the polymer membrane is small enough, the diffusion layer of each micro-nanopore channel electrode will overlap with the adjacent diffusion layer, which may produce a semi-infinite linear diffusion curve, and the cyclic voltammogram of the final electrode measurement presents a typical transient voltammogram, which is a comprehensive manifestation of the polymer membrane pore electrode. In the cyclic voltammetry test experiment of the constructed BSA/g-C3N4/Bi2WO6/GA polymer film, we observed that under a series of high-speed scans, the electrode showed a transient voltammogram. According to the above hypothesis, the results inferred can show that this is due to the short distance between the pores in the coating, which leads to the overlap of the diffusion curves. By setting a simple model that only considers the diffusion effect of the electroactive substance and the distance between the pores, combined with the model constructed by Guo and Lindner32, the measured results are consistent with the predicted overlap of the pore diffusion curve, indicating that the size and distance of the pores in the polymer film we constructed are smaller than the distance of diffusion of the electroactive substance.

Although the BSA/Bi2WO6 coated electrode showed some redox current in the test, the BSA in the BSA/Bi2WO6/GA polymer coating produced dense pores due to GA cross-linking, which also increased the transmission efficiency of electroactive ions in the electrode. The electrochemical performance of the pure BSA bio-based polymer film modified electrode is also inferior to that of the electrode with the addition of a two-dimensional layered conductive material polymer coating, because the latter produces a larger current and a narrower potential difference. In order to gain a deeper understanding of this behavior, we propose a hypothesis for further research: BSA molecules at a given concentration are dispersed and adsorbed on the surface of Bi2WO6 loaded on the electrode. The BSA adsorption layer formed by this behavior almost eliminates the transfer of electrons to the electrode surface. The introduction of other conductive materials cannot solve this inert behavior. Even the introduction of a certain amount of GA, in materials with low polymerization degrees, also produces a situation of blocking the effective pore structure of Bi2WO6 particles, but when the polymer forms a film layer with a continuous shape, these Bi2WO6 particles are exposed and located at the far end of the thin organic coating. The charge transfer between the electroactive substance in the solution and the electrode can occur on the Bi2WO6 surface through the electron transfer mediated by the Bi2WO6 particles, as tested and observed by the electrochemical behavior. Unlike pure BSA protein cross-linked polymers that rely only on polymer pores as channels for electron transmission, the introduction of conductive two-dimensional sheet g-C3N4 materials can not only enhance the conductivity of the overall polymer matrix, but also the g-C3N4 materials rich in primary and secondary amines can serve as effective sites for urea-formaldehyde condensation reactions, and can act as effective cross-linkers for 3D polymer skeletons33. At the same time, the dense pores formed by the polymerized materials also become ion transmission channels. Therefore, although some of the polymerized materials cover and fill the significant pores of Bi2WO6, the close fit between the conductive polymer matrix and the Bi2WO6 particles will not affect the electron transmission function, nor will it passivate the electrode.

It can be found that the polymer film formed by the mixture of g-C3N4 or NH2-rGO and BSA under glutaraldehyde crosslinking also shows similar electron transfer kinetics to the BSA protein polymer, indicating that the introduction of two-dimensional conductive materials can construct ion channels and enhance the ability of the modified electrode on the flower-like Bi2WO6 surface to transport ions. Considering the anti-fouling ability of the polymer matrix and the detection ability of its modified electrode to heavy metal ions, it can be found that the two-dimensional material g-C3N4 doped with BSA polymer matrix coated Bi2WO6 modified electrode has stronger detection and analysis ability for heavy metal ions than graphene polymer. By comparing the formation mode of the polymer film, we speculate that it may be because g-C3N4 may rely on some N atoms to participate in the polymerization process during the crosslinking polymerization process, and the remaining N atoms with lone pairs of electrons can serve as the action sites for the chelation and pairing of heavy metal ions34. This effect is due to the two-dimensional network of g-C3N4 composed of the N-rich melamine molecular structure. As can be seen from Fig. 2, with the increase in the degree of polymerization of BSA and g-C3N4, the proportion of Bi2WO6 active sites exposed increases, and the modified electrode has a stronger response ability to the electroactive substances.

Antifouling mechanism of cross-linked polymer conductive membrane

The antifouling ability of BSA cross-linked polymer coatings for macromolecules such as biological proteins is due to the fine porosity of the cross-linked polymer matrix, which can effectively prevent large biomacromolecules from diffusing through the pores. In order to further prevent the nanoscale pores from being blocked and contaminated by small molecule compounds, and at the same time, realize the migration and analysis of heavy metal ions in the pores, we developed BSA/g-C3N4/GA and BSA/NH2-rGO/GA coatings. These coatings are specifically designed to match the pore size of the polymer membrane, allowing ion migration while blocking these species from reaching the electrode surface. Previous literature reports indicate that the pore diameter on the coating surface is smaller than the typical effective size of HSA protein under physiological conditions, measured at 2.74 ± 0.35 nm35. The introduction of a smaller molecular weight cross-linking monomer g-C3N4 can more effectively regulate and generate smaller pores. In the detection of heavy metals in body fluids (blood, tears, urine, sweat, etc.) and environmental water sample (drinking water, agricultural irrigation water, groundwater, etc.), through this mode of action, due to size exclusion, the nonspecific adsorption of soluble albumin molecules (albumin accounts for about 60% of total plasma proteins) present in body fluid detection and dissolved organic matter (DOM) in water samples is prevented (Supplementary Fig. 3), so we used this abundant protein to examine the antifouling effect, which is usually the main cause of clinical POCT sensor contamination. To further explore this, we conducted a control study to determine whether proteins in human tissue fluid may be adsorbed to the coating through forces such as electrostatics and block the pores for ion transfer. 10 mg/mL HSA was incubated on BSA/Bi2WO6, BSA/NH2-rGO, BSA/g-C3N4, BSA/NH2-rGO/GA, BSA/Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO/GA, BSA/g-C3N4/GA and BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA modified electrodes to investigate the state of electron transfer kinetics before and after incubation. It can be observed that after a long period of HSA incubation, a strong current and low ΔEp were maintained on the BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA electrode.

By fixing the g-C3N4 content and adjusting the ratio of BSA to GA, the effects of polymer films formed at different cross-linking degrees on sensor analysis and anti-fouling performance were explored. Since g-C3N4 and Bi2WO6 are functional materials with photoelectric generation effects, the combined factors of the amount of g-C3N4 cross-linking in the polymer film and the amount of Bi2WO6 light exposure determine the photocurrent intensity. In addition, another factor that enhances the photocurrent is the Z-type heterojunction formed between Bi2WO6 and g-C3N4 molecules36. This structure can enable the composite material to generate photogenerated electrons with higher efficiency in visible light absorption, and the photogenerated electrons have excellent transmission properties in the formed 3D conductive matrix37. When the cross-linked polymer matrix of g-C3N4 and BSA is densely coated on Bi2WO6, it can not only promote the generation of photogenerated electrons, but also accelerate the conduction of electrons to the electrode surface and reduce the energy consumption during electron transfer (Fig. 3a). When the coatings with different polymerization degrees are contaminated by HSA biomacromolecules, the low densites or excessively high degrees of crosslinked polymer coating electrode cannot play a good anti-fouling effect, causing the generation of photogenerated electrons and the transfer effect to the electrode to deteriorate. At the same time, after incubation with HSA, its electrochemical behavior also shows different effects with the change of polymerization degree.

a Optimization and characterization of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coatings with varied formulations (n = 5). White bars indicate the average current density of fresh coatings, gray bars indicate 1 day incubation in 10 mg/mL HSA, and the error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of the measurements. b Average BSA binding per coating was calculated for BSA (0.1–1 mg/mL) and GA (0.1–10%). Dashed lines (2–50) indicate the optimal range for forming 3D BSA/g-C3N4 matrices without excess GA. c Comparison of the deposition performance of polymer-coated electrodes with different ratios for heavy metal ions (Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, Zn2+). d Investigation of the optimal deposition time of the coated electrodes produced under the optimal polymer ratio conditions for heavy metal ions (Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, Zn2+).

Previous studies have shown that BSA crosslinked with GA relies on residual functional groups, including amines, phenols, thiols, and imidazoles, present in various internal amino acids31. Crosslinking reactions primarily involve the exposed lysine residues. Under the condition that the polymer monomer is rich in primary amines, the five-carbon GA aldehyde group will react with it quickly to form a polymer with a pyridine ring structure, which can be used as a cross-linking structural adhesive. This rapid cross-linking mechanism of dehydration condensation can form a 3D polymer molecular network and retain the native conformation of the protein polymer monomer31. The formation of pyridine polymers requires at least five GA molecules to produce effective crosslinks between two amine functional groups. Glutaraldehyde can effectively connect g-C3N4 to BSA molecules; since the proportion of g-C3N4 in the prepolymer is fixed, the calculation of the average cross-link number of BSA molecules can predict and evaluate the morphology of the final polymer cross-linking product. Since the BSA polymer backbone plays a major antifouling role, we mainly consider the effect of different degrees of BSA crosslinking on the performance of the polymer film under different BSA and glutaraldehyde ratios with a constant proportion of g-C3N4 in the prepolymer. Complexes with fewer than two intra- or inter-molecular linkages between g-C3N4 and BSA tend to form linear polymer chains, dimers, or other oligomeric species. In contrast, when the average number of linkages meets or exceeds the number of reactive amino acids available within the BSA molecule, the complexes form highly cross-linked and dense polymers. This cross-linking process, however, leaves an excess of unreacted aldehyde groups on the surface. There are still too many unreacted glutaraldehyde groups remaining on these highly cross-linked polymer coatings. These very active functional groups will also react with non-target detection proteins, active organic compounds, etc., in the sample to be tested, which may cause blockage and contamination of the polymer pores, resulting in poor anti-fouling ability of the polymer membrane. To optimize electrode performance, we tested several formulas with varying degrees of cross-linking. Quantitative analysis of the average number of connections per BSA molecule revealed that polymers formed by formulas such as 1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/1 GA, 0.5 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/0.1 GA, 0.5 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/0.5 GA, 0.1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/0.5 GA, and 0.1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/0.1 GA were predominantly composed of monomers and dimers. In contrast, formulas like 1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/10 GA and 0.5 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/5 GA produced highly cross-linked coatings (Fig. 3b). Specifically, based on the stoichiometric calculation of reactive groups (-NH₂ in BSA/g-C₃N₄ and -CHO in GA) assuming a 1:1 reaction ratio for Schiff base formation, the 1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/5 GA and 0.1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/1 GA coatings are theoretically estimated to form an average of 17 and 41 cross-links between BSA and g-C3N4 molecules, respectively.

In this case, BSA and the conductive two-dimensional layered g-C3N4 molecules together form a 3D protein polymer matrix. Although this coating shows the best antifouling performance, it is not the same as the single BSA protein polymer matrix; this may be due to the effect of g-C3N4 on the change of the conductivity of the polymer membrane interface and pores. In this case, the polymerization participation and the effect of the introduced g-C3N4 need to be considered. In general, when a certain amount of g-C3N4 is introduced, the polymer has a better antifouling effect when it is in a 3D cross-linked state. In addition, a good 3D conductive coating is expected to be uniformly cross-linked, with well-defined pore sizes and a controlled number of connections between polymerized monomer molecules. We use the photocurrent density generation efficiency to further investigate the synergistic antifouling of g-C3N4 and BSA and its conductive efficiency. Due to the excellent electron generation efficiency of Bi2WO6 under visible light excitation, we can closely link the density of dense ion channels formed by BSA and g-C3N4 polymer films on the surface of Bi2WO6 and the degree of cross-linking participation of g-C3N4 with the photoelectron generation efficiency. 80% of the BSA protein molecules in the 0.1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/1 GA complex bind to 5–10 proteins or g-C3N4. In contrast, the 1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/5 GA coating has a higher average number of bonds per BSA, resulting in a more uniform and denser coating with smaller pores. This also explains why the 1 BSA/0.2 g-C3N4/5 GA coating has stronger anti-fouling ability and higher photocurrent density. The four toxic heavy metals of focus, mercury, lead, cadmium, and zinc, were used to further investigate the analytical performance of the above-mentioned developed electrodes (Fig. 3c). In summary, the optimal BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA containing 0.2 mg/mL g-C3N4, 1 mg/ml BSA, 5% GA and ≥1 mg/mL Bi2WO6 was used for further research and use, which took into account the highest current density, photocurrent generation efficiency, deposition effect of heavy metals and the lowest performance degradation after incubation in 10 mg/mL HSA for 1 d. It can be found that on this densely porous conductive polymer film, the four heavy metals can achieve the optimal deposition effect in a short time of 90 s (Fig. 3d).

Application of heavy metal detection analysis in complex matrices

Understanding the performance of sensors in complex media is critical for the field of sensing analysis for environmental monitoring and clinical diagnostics. Therefore, we conducted tolerance tests on the electrodes modified with the optimized BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA composites. The electrodes were exposed to 10 mg/mL HSA, untreated human serum or plasma, and wastewater for various time periods to evaluate their stability. Remarkably, after one month of exposure to various complex samples, the electrochemical sensor modified with the BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coating demonstrates excellent antifouling performance, with a sensitivity loss of only ~8.5% (as shown in Fig. 4a). While the BSA/Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO/GA-coated electrode retained up to 70% of its current density after soaking in 10 mg/mL HSA for 1 h, its sensitivity declined significantly with extended exposure. In contrast, the BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA-coated electrode maintained a high current density even after one month of immersion in complex fluids, comparable to that of pristine, unmodified gold electrodes (Fig. 4a).

a Comparison of the average current density recorded for BSA/Bi2WO6/NH2-rGO/GA in human serum or human plasma stored at 4 °C for >30 days and BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coated electrodes stored in human serum, human plasma or wastewater at 4 °C for >30 days. The data represent (n = 5) independent electrodes, with error bars showing the mean ± SD). b Changes in electrochemical impedance of the sensor fabricated using the optimal BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA ratio after deposition of different types of heavy metal ions (measured in PBS). c Impedance change graph extracted from the electrical impedance fitting in (b). d The sensor with the optimal BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA ratio was used to measure changes in the electrode’s photoelectric properties after deposition of heavy metal ions (Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, Zn2+).

Using the optimized BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA-coated electrode, the deposition mechanism of heavy metals on the electrode surface involves a synergistic process of ion transport, electrochemical reduction, and alloy formation, which can be tracked through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and photocurrent measurements (Fig. 4b–d). EIS characterizes changes in charge transfer resistance (Rct) induced by surface property alterations of Bi2WO6 exposed in the nanoscale ion channels after electroreduction, while photocurrent measurements reflect the shielding effect caused by heavy metal deposition passivating the active sites of Bi2WO6.

Stripping voltammetry is a well-established analytical method for the electrochemical detection of heavy metals, where deposition potential and solution pH are key factors influencing detection performance. By selecting a wide range of pH values and different deposition potentials, we investigated the analytical performance of the developed and optimized sensor for these four heavy metal ions. pH variation regulates the solubility of metal ions and the surface charge of Bi2WO6 materials, indirectly influencing deposition efficiency. The deposition potential directly controls the completeness of metal reduction and alloy formation. Collectively, these factors determine the content of electrochemically strippable metal species. The results show that the electrode exhibits the best analytical performance for these metals at pH 8.0 and a deposition potential of −1.6 V (Fig. 5a, b). At the same time, we also observed a linear relationship between concentration and response for these four heavy metal ions when mixed in equal proportions at varying concentrations (Fig. 5d, e) and when the concentration of a single ion changed. The experimental results show that there is an excellent linear relationship between concentration and response. When we use a mixed solution of four heavy metal concentrations at a specific concentration for detection and analysis, its performance remains excellent under long-term (n = 30 day) repeated (n = 5) detection. Batch-to-batch variability in electrode fabrication was evaluated by comparing the analytical performance of sensors prepared in six independent batches. All batches demonstrated consistent detection performance for the four target ions, with <5% variation in sensitivity (RSD, n = 5 measurements per batch) (Fig. 5c, f). When the concentration of Hg2+ is changed, the response of Cd2+ and Pb2+ will change slightly. The possible reason is that the high concentration of Hg2+ deposition will promote the co-deposition of Cd2+ to a limited extent and will slightly weaken the co-deposition effect of Pb2+ (as shown in Fig. 6). This situation can be ignored when detecting low concentration ions. Based on Eq. (3), the detection limits of the constructed sensor for the four ions Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+ were 0.09 μg/L, 0.019 μg/L, 0.03 μg/L, and 0.045 μg/L, respectively. Although the BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA coated electrode maintains good analytical performance, the sensor’s shelf life may be limited by the composite film’s resistance to fouling under prolonged exposure to biological contaminants and use. To validate sensor performance in real samples, two authentic water samples (river water and lake water) were analyzed. Following 10 min sedimentation, supernatant aliquots were spiked with target heavy metal ions (Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺, Zn²⁺) for comparative analysis. Measurements from the fabricated electrochemical sensor showed strong agreement with ICP–MS reference data (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, we will apply it to various real samples such as water bodies and blood (Supplementary Fig. 4). Supplementary Table 2 benchmarks state-of-the-art electrochemical platforms for heavy metal ion (HMI) quantification employing functionalized electrodes. The engineered BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA sensing interface demonstrates dual advantages versus literature systems: (i) enhanced sensitivity and (ii) exceptional fouling resistance in complex matrices. This synergistic performance enables direct field deployment of HMI monitoring without preprocessing.

a SWV response spectra of the BSA/Bi2OW6/g-C3N4/GA coating electrode with the best ratio optimization to four heavy metal concentrations of 10 μg/L under different pH conditions. b SWV response spectra of the BSA/Bi2OW6/g-C3N4/GA coating electrode with the best ratio optimization at different deposition potentials to four heavy metal concentrations of 10 μg/L. c Performance stability of the same electrode for four heavy metal ions at fixed concentrations of 5 μg/L each under long-term use conditions. d The concentrations of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺, and Zn²⁺ were systematically and synchronously varied from 0.05 to 10 μg/L. e The figure shows the current response extracted from d and the corresponding data of the four heavy metal concentration changes and the linear fit. Five experiments were averaged using five independent electrodes. The dots represent the mean of the current, and the error bars are the standard deviation of the mean. f Stability performance test of different electrodes via multiple current responses to four heavy metal ions, tested five times at a fixed concentration of 5 μg/L.

a The concentrations of Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺, and Zn²⁺ were fixed at 10 μg/L, while the Cd²⁺ concentration was varied systematically from 0.05 to 10 μg/L. The inset shows a linear correlation between the current response and Cd²⁺ concentration within this range. b The concentrations of Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺, and Zn²⁺ were consistently fixed at 10 μg/L, while the Pb²⁺ concentration was adjusted across a range of 0.05 to 10 μg/L. The inset illustrates a clear linear relationship between the current response and Pb²⁺ concentration over the investigated range. c The concentrations of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Zn²⁺ were maintained at 10 μg/L, while the Hg²⁺ concentration was varied from 0.05 to 10 μg/L. The inset shows the relationship between current response and Hg²⁺ concentration, with changes in Hg²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cd²⁺ concentrations influencing the responses. The data were fitted to an isothermal adsorption curve. d The concentrations of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Hg²⁺ were fixed at 10 μg/L, while the Zn²⁺ concentration was systematically varied from 0.05 to 10 μg/L. The inset highlights a linear correlation between the current response and Zn²⁺ concentration within the tested range.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a binary condensation conductive bio-based polymer membrane that demonstrates excellent antifouling and conductive properties on the surface of the working electrode. When combined with bismuth-based materials with a high specific surface area, the composite coating further enhances the electrochemical sensor’s performance in heavy metal analysis. The preparation of the polymer membrane is based on the antifouling properties of BSA molecules for various large-sized biomolecules, the introduction of highly conductive and N-rich two-dimensional g-C3N4, and the effective regulation of the cross-linking degree of 3D biomolecules and conductive two-dimensional layered materials on the size of ion migration channels through the urea-formaldehyde condensation reaction. This composite coating successfully alleviates the challenge of electrode material fouling, even under complex biological fluids, thereby improving the diagnostic performance of electrochemical sensors and facilitating their long-term reuse on the same chip. Due to the construction of smaller-scale ion channels within the pores achieved by cross-linking the conductive two-dimensional layered material g-C3N4 with BSA, the diffusion of ions and electrons is enhanced, thereby promoting the correct signal transmission on the working electrode. A key aspect of our fabrication approach lies in the one-pot in situ polymerization process. Compared with the layer-by-layer assembly method, this in-situ modification process can not only reduce the differences between chip sensor preparations, but also be continuously batched, low-cost and time-effective. This is essential for future commercialization at scale. By employing this method, we constructed 300 electrochemical sensors within 25.5 h. These sensors are capable of simultaneously detecting trace toxic heavy metal ions Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+ with high sensitivity and selectivity (shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The outstanding antifouling properties of the composite material prevent signal attenuation caused by non-specific species in plasma, serum, and water samples. This advantage has the potential to simplify the sample pretreatment steps in field detection and analysis applications. The developed high-precision sensing (Supplementary Table 5) and analytical technology enable the rapid collection of large-scale field data through simple detection methods. This allows for a deeper understanding of the sources of heavy metal pollution and the correlations between different pollution sources. Moreover, it holds the potential for targeted, personalized detection and analysis of potential pollution sources, thereby improving detection measures and personalized pollution control strategies to meet the urgent demands of rapid emergency response to heavy metal emissions.

This composite coating modification technology holds great potential for applications in the field of electrochemical sensors. The polymer thin film coating, with its excellent antifouling properties, can effectively prevent signal interference and attenuation caused by non-target substances in the test solution under complex environmental conditions. As a result, it simplifies the sample preparation steps in field detection applications, streamlines the overall testing process, and reduces the generation of false signals. In addition, the continuous introduction of a variety of active functional polymer monomer materials into the functional construction system of porous composite materials can allow the expansion of the analytical application range of various ions and organic pollutants to be tested. This comprehensive diagnostic capability is essential for managing future heavy metal exposure diseases and tracing environmental heavy metal pollution, because rapid and accurate diagnosis is essential. Large amounts of test data can be collected efficiently and cost-effectively in a simplified manner, and this strategy should enhance our understanding of the correlation between human heavy metal exposure levels and the living environment. This will not only help improve diagnostic accuracy and monitor environmental heavy metal exposure levels, but also help us understand the extent of heavy metal pollution and customize patient management strategies for removing heavy metals from the body. Ultimately, the establishment of a robust nonspecific adsorption barrier also presents opportunities for the design of other types of sensor interfaces, including implanted devices and medical diagnostic equipment. By reducing undesirable interactions with nonspecific molecules, this technology has the potential to improve the analytical performance and lifespan of sensors, while possibly alleviating rejection reactions with the analytical receptors, thereby improving their reliability.

Methods

Synthesis of g-C3N4, NH2-rGO, and flower-like Bi2WO6

The preparation method of g-C3N4 mainly involves the thermal condensation of melamine with thiourea. Similar to previous literature reports38, we made a slight modification. Briefly, a solution containing melamine (4.6 g/L) and thiourea (1.25 g/L) was thoroughly mixed and sealed in a ceramic crucible. The crucible was placed in a muffle furnace, heated at a rate of 5 °C/min to 580 °C, and maintained at this temperature for 1 h. After natural cooling, yellowish g-C3N4 lumps were collected from the bottom of the crucible, dried at 100 °C, and ground into a fine powder for further use. The as-obtained g-C3N4 powder was ultrasonically dispersed in a certain amount of ultrapure water for 2 h, and the suspension was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm to obtain ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets.

The single-layer rGO was purchased through Jiangsu Xianfeng Nanotechnology Co., Ltd. NH2-rGO preparation: We followed the method reported in previous literature and made slight modifications to the method. Add 0.12 g of single-layer rGO to 40 mL of ethylene glycol and disperse under ultrasonic treatment. Further add 1 mL of ammonia water, transfer the dark brown solution to a high-pressure vessel lined with Teflon, and place it at 180 °C for solvent thermal reaction for 10 h. After the reaction is complete, filter the reactants. Leave the precipitate behind, wash it repeatedly with distilled water, and place it in a 60 °C drying oven for 24 h. After drying, further use. Unless further mentioned, the samples used in the following electrochemical measurements were prepared under these conditions.

We modified the method reported in the literature39 and synthesized flower-like Bi2WO6 via coprecipitation. Bismuth nitrate (Bi(NO3)3) and sodium tungstate (Na2WO4) were used as precursors. Specifically, 0.919 g Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and 0.833 g Na2WO4 were dissolved in 40 mL of distilled water, stirred at room temperature for 3 h, and ultrasonicated for 5 min every hour. The mixture was then transferred to a sealed 50 mL Teflon-lined crucible and heated at 150 °C for 20 h. Finally, the resulting precipitate was collected, thoroughly washed alternately with ultrapure water and anhydrous ethanol, and dried at 75 °C for 7 h.

Preparation of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA cross-linked complex conductive polymer film

The g-C3N4 nanosheets, flower-shaped Bi2WO6, BSA and glutaraldehyde solution prepared above were mixed in a certain proportion. Specifically, 2.95 mL of g-C3N4/Bi2WO6 (with varying proportions, where the concentration of g-C3N4 and Bi2WO6 was ≥1 mg/mL) was mixed with 5–500 μL 70% GA. The mixture was shaken for 10 min and then ultrasonicated for 1 min, yielding a cross-linked prepolymer of BSA, g-C3N4 and glutaraldehyde wrapped with flower-shaped Bi2WO6 encapsulated within.

Fabrication of BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA/SPE sensor

After each grinding of the working electrode, clean the electrode with ethanol and ultrapure water under ultrasound. Prepare the composite solution according to the optimized formulation (1 mg/mL BSA/0.2 mg/mL g-C3N4/5 mg/mL GA) and mix thoroughly using a vortex mixer. Subsequently, rapidly pipette 70 µL of the pre-polymerized solution onto the surface of the working electrode and allow it to dry. Then place the electrode in a water-moistened box, and incubate the box in a constant-temperature shaker at 25 °C for 24 h to ensure sufficient polymerization. Upon reaction completion, the electrodes were dried in an oven at 40 °C for 60 min. Finally, it was rinsed with ultrapure water and ethanol to remove unreacted compounds, reactive monomers and oligomers. The prepared electrode sensor was used for the next experimental steps.

Electrochemical characterization of polymer coating modified electrodes

The planar microfabricated chip used in the electrochemical experiments contains a gold working electrode (approximately 1.5 mm2), a gold reference electrode, and a gold counter electrode. The sensor was connected to an IGS6030 electrochemical workstation (Guangzhou Ingsens sensor technology, China) via a homemade connection box and controlled by IGS4030CN software for data acquisition. During the coating preparation process, the percentage of GA, the concentration of g-C3N4 and BSA were optimized: the content of g-C3N4 was fixed at 0.2 mg/mL, the concentration range of BSA was 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL, and the range of GA was 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 10% (v/v). The coating time was optimized as follows: the pre-polymer mixture was drop-coat onto the working electrode surface and incubated at 25 °C for 1 day; afterward, the electrode chip was flushed with PBS buffer using a syringe (injection needle hole specification: 0.5 mm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min for 5 min, with the distance between the chip and the needle being 1 cm. The coating was electrochemically characterized before and after incubation in 10 mg/mL HSA for 1 day. Nanocomposite coatings were characterized by cyclic voltammetry (scan rate of 100 mV/s, potential range: −0.5 and 0.5 V vs. open circuit potential) and EIS (frequency range: 0.1 Hz to 0.1 MHz, amplitude: 5 mV amplitude vs. open circuit potential, 50 logarithmic interval measurements) in an aqueous redox solution containing (5 mM K3Fe(CN)6/K4Fe(CN)6 in 1 M KCl).

Four heavy metal standard solutions (1000 mg/L) were diluted to an intermediate concentration of 1000 μg/L using analytical buffer. This intermediate solution was then serially diluted with the same buffer to generate calibration standards at target concentrations of 0.05, 0.08, 0.1, 0.2, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0 μg/L for subsequent electrochemical analysis. The solution used for method optimization was a 10 μg/L mixed solution of four heavy metals: Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+. During the determination using four different electrochemical methods, parameters such as deposition time and deposition potential were held constant. Following the single-variable principle, only the electrochemical voltammetry mode was altered for the determination. Heavy metal ions are measured using square wave voltammetry. The detection process consists of two consecutive stages: an open-circuit pre-concentration (deposition) step of the analyte solution on the electrode, followed by transfer of the electrode to the analytical buffer solution for voltammetric detection. The first step involves immersing the electrode chip into a beaker containing 20 mL of heavy metal solution at a specific concentration. After a predetermined deposition time under mild stirring, the electrode is quickly removed and rinsed with ultrapure water. The electrode is then transferred to an electrochemical cell containing the detection buffer. All experiments were repeated five times, with the data points representing the average of five repetitions.

BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA/SPE sensor fouling test

All reagents were prepared in the assay buffer, and the electrode was rinsed with 2 mL of the same buffer after each testing step. Functionalized or unfunctionalized BSA/Bi2WO6/g-C3N4/GA/ coated electrodes were incubated with HSA, human serum and plasma, or wastewater for different lengths of time, and then tested by cyclic voltammetry in an electroactive potassium ferrocyanide solution.

Determining diffusion-limited electrochemical processes by the Randles–Sevcik equation

To diagnose solution-phase diffusion control of an analyte, cyclic voltammetry responses should exhibit a linear dependence of peak current (ip) on the square root of scan rate (\(\sqrt{\nu }\)). Concurrently, consistent peak separation (ΔEp) across scan rates validates reversible behavior. This diagnostic criterion is formalized by the Randles–Sevcik equation:

where n denotes electron count per redox reaction, A (cm2) corresponds to the electrode’s geometric area, D0 (cm2 s−1) represents the analyte’s diffusion coefficient, and C0 (mol cm−3) signifies its bulk concentration.

Calibration of standard curve, LOD, and LOQ

The calibration standard curve of the sensor was constructed by measuring the oxidation current intensity of four heavy metal ions at different concentrations under mixed conditions, and fitting the data to a linear regression:

Here, y represents the current intensity, and x denotes the analytical concentration of the ion being measured. a is the slope and b is the intercept, which are the parameters obtained by fitting the linear. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) we defined are the concentration on the calibration curve corresponding to yLOD and yLOQ, respectively, where yLOD is the average current of the blank sample plus three times the standard deviation of the blank response, denoted as yLOD:

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (email: jiawenchao1988@gmail.com) on reasonable request.

References

Yildiz, C., Bayraktepe, D. E., Yazan, Z. & Önal, M. Bismuth nanoparticles decorated on Na-montmorillonite-multiwall carbon nanotube for simultaneous determination of heavy metal ions- electrochemical methods. J. Electroanal. Chem. 910, 116205 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Stripping voltammetric determination of cadmium and lead ions based on a bismuth oxide surface-decorated nanoporous bismuth electrode. Electrochem. Commun. 136, 107233 (2022).

Ai, Y. J. et al. Ultra-sensitive simultaneous electrochemical detection of Zn(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) based on the bismuth and graphdiyne film modified electrode. Microchem. J. 184, 108186 (2023).

Kim, M. et al. Detection of heavy metals in water environment using nafion-blanketed bismuth nanoplates. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 6844–6855 (2023).

Yin, H. Y. et al. Ultra-sensitive detection of multiplexed heavy metal ions by MOF-derived carbon film encapsulating BiCu alloy nanoparticles in potable electrochemical sensing system. Anal. Chim. Acta 1239, 340730 (2023).

Hui, X. et al. A nanocomposite-decorated laser-induced graphene-based multi-functional hybrid sensor for simultaneous detection of water contaminants. Anal. Chim. Acta 1209, 339872 (2022).

Sempionatto, J. R., Lasalde-Ramírez, J. A., Mahato, K., Wang, J. & Gao, W. Wearable chemical sensors for biomarker discovery in the omics era. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 899–915 (2022).

Jyoti et al. 2-(Anthracen-9-yl)benzothiazole-modified graphene oxide-nickel ferrite nanocomposite for anodic stripping voltammetric detection of heavy metal ions. Microchim. Acta 189, 186 (2022).

González-Martfnez, E., Saem, S., Beganovic, N. E. & Moran-Mirabal, J. M. Electrochemical nano-roughening of gold microstructured electrodes for enhanced sensing in biofluids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218080 (2023).

Lv, H. M. et al. Portable anti-fouling electrochemical sensor for soil heavy metal ions detection based on the screen-printed carbon electrode modified with silica isoporous membrane. J. Electroanal. Chem. 930, 117141 (2023).

Sahragard, A., Varanusupakul, P. & Miró, M. Nanomaterial decorated electrodes in flow-through electrochemical sensing of environmental pollutants: a critical review. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 39, e00208 (2023).

Tesfaye, E., Chandravanshi, B. S., Negash, N. & Tessema, M. Simultaneous electrochemical determination of cadmium(II), lead(II), and mercury(II) ions in water and food samples using N1-hydroxy-N1,N2-diphenylbenzamidine and multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified carbon paste electrode. Electroanalysis 35, e202300022 (2023).

Li, J. P. et al. Highly selective and sensitive Pb2+detection via sulfur-doped graphitic carbon nitride modified by Bi nanospheres. Microchem. J. 203, 110855 (2024).

Huang, R. H. et al. Sensitive electrochemical quantification of trace lead and cadmium of food samples based on B, N, S, and P-multiple-doped framework-based carbon aerogels. Chem. Eng. J. 471, 144651 (2023).

Yu, X. L. et al. Experimental and theoretical elucidation of the luminescence quenching mechanism in highly efficient Hg2+ and sulfadiazine sensing by Ln-MOF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202410509 (2024).

Del Rosso, T. et al. On the strong binding affinity of gold-graphene heterostructures with heavy metal ions in water: A theoretical and experimental investigation. Langmuir 40, 20204–20218 (2024).

Sun, X. C. et al. Ultrathin graphdiyne/graphene heterostructure as a robust electrochemical sensing platform. Anal. Chem. 94, 13598–13606 (2022).

Ngoensawat, U., Pisuchpen, T., Sritana-anant, Y., Rodthongkum, N. & Hoven, V. P. Conductive electrospun composite fibers based on solid-state polymerized Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for simultaneous electrochemical detection of metal ions. Talanta 241, 123253 (2022).

Sivan, V. et al. Liquid metal marbles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 144–152 (2013).

Dimovasilis, P. A. & Prodromidis, M. I. Bismuth-dispersed xerogel-based composite films for trace Pb(II) and Cd(II) voltammetric determination. Anal. Chim. Acta 769, 49–55 (2013).

Hu, X. P., Pan, D. W., Lin, M. Y., Han, H. T. & Li, F. Graphene oxide-assisted synthesis of bismuth nanosheets for catalytic stripping voltammetric determination of iron in coastal waters. Microchim. Acta 183, 855–861 (2016).

Zhao, G. & Liu, G. Synthesis of a three-dimensional (BiO)2CO3@single-walled carbon nanotube nanocomposite and its application for ultrasensitive detection of trace Pb(II) and Cd(II) by incorporating Nafion. Sens. Actuator B 288, 71–79 (2019).

Jovanovski, V., Hocevar, S. B. & Ogorevc, B. Bismuth electrodes in contemporary electroanalysis. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 3, 114–122 (2017).

Zeinu, K. M. et al. A novel hollow sphere bismuth oxide doped mesoporous carbon nanocomposite material derived from sustainable biomass for picomolar electrochemical detection of lead and cadmium. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 13967–13979 (2016).

Pal, S. et al. β-Bi2O3-Bi2WO6 nanocomposite ornated with meso-tetraphenylporphyrin: Interfacial electrochemistry and photoresponsive detection of nanomolar hexavalent Cr. Inorg. Chem. 62, 21201–21223 (2023).

Jaihindh, D. P., Thirumalraj, B., Chen, S. M., Balasubramanian, P. & Fu, Y. P. Facile synthesis of hierarchically nanostructured bismuth vanadate: An efficient photocatalyst for degradation and detection of hexavalent chromium. J. Hazard. Mater. 367, 647–657 (2019).

Yao, H. et al. A machine learning strategy-incorporated BiFeO3/Ti3C2 MXene electrochemical platform for simple, rapid detection of Pb2+ with high sensitivity. Chemosphere 340, 139728 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ultra-sensitive electrochemical sensors through self-assembled MOF composites for the simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metal ions in food samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 1289, 342155 (2024).

Svancara, I., Prior, C., Hocevar, S. B. & Wang, J. A decade with bismuth-based electrodes in electroanalysis. Electroanalysis 22, 1405–1420 (2010).

Lee, J.-C. et al. Micrometer-thick and porous nanocomposite coating for electrochemical sensors with exceptional antifouling and electroconducting properties. Nat. Commun. 15, 711 (2024).

Sabaté del Río, J., Henry, O. Y. F., Jolly, P. & Ingber, D. E. An antifouling coating that enables affinity-based electrochemical biosensing in complex biological fluids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 1143–1149 (2019).

Guo, J. & Lindner, E. Cyclic voltammograms at coplanar and shallow recessed microdisk electrode arrays: guidelines for design and experiment. Anal. Chem. 81, 130–138 (2009).

Zhang, M., He, L., Shi, T. & Zha, R. H. Neat 3D C3N4 monolithic aerogels embedded with carbon aerogels via ring-opening polymerization with high photoreactivity. Appl. Catal. B 266, 118652 (2020).

Dai, X. X. et al. Amino-functionalized MCM-41 for the simultaneous electrochemical determination of trace lead and cadmium. Electrochim. Acta 144, 161–167 (2014).

Kiselev, M. A., Gryzunov, Y. A., Dobretsov, G. E. & Komarova, M. N. The size of human serum albumin molecules in solution. Biofizika 46, 423–427 (2001).

Chen, J. et al. Daul Z-scheme heterojunction BiOBr/Bi2O2.33/g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light-driven tetracycline hydrochloride degradation. J. Alloy. Compd. 969, 172441 (2023).

Moradi, S., Isari, A. A., Hayati, F., Kalantary, R. R. & Kakavandi, B. Co-implanting of TiO2 and liquid-phase-delaminated g-C3N4 on multi-functional graphene nanobridges for enhancing photocatalytic degradation of acetaminophen. Chem. Eng. J. 414, 128618 (2021).

Cao, S. W., Low, J. X., Yu, J. G. & Jaroniec, M. Polymeric photocatalysts based on graphitic carbon nitride. Adv. Mater. 27, 2150–2176 (2015).

Zhang, Y. H., Zhang, N., Tang, Z. R. & Xu, Y. J. Identification of Bi2WO6 as a highly selective visible-light photocatalyst toward oxidation of glycerol to dihydroxyacetone in water. Chem. Sci. 4, 1820–1824 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3709702), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2022A1515110111), Guangzhou Science and technology Innovation Development Special Fund Fundamental and Applied Fundamental Research Project (Grant No. 202102020479).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., Z.X., B.Z., D.X. and W.J. conceived the research idea and proposed the experimental design. Y.W. and Z.X. and X.J. performed the characterizations and analytical tests. Y.W., Z.X., and W.J. contributed to the preparation and writing of the paper. All authors reviewed and agreed to the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks begona espina, Renato Gil and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Xu, Z., Jin, X. et al. Antifouling bismuth composite for robust electrochemical detection of heavy metals in complex matrices. Commun Mater 6, 258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00990-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00990-1