Abstract

CeRh6Ge4 is a cerium-based ferromagnetic material exhibiting a quantum critical behavior under pressure. We derive effective exchange interactions, using the framework of density functional theory combined with dynamical mean-field theory. Our results reveal that the nearest-neighbor ferromagnetic interaction along the c axis is isotropic in spin space, leading to a formation of spin chains. On the other hand, the inter-chain coupling is highly anisotropic: The in-plane moment weakly interacts ferromagnetically in the a–b plane to stabilize the ferromagnetic state, whereas the z-component couples antiferromagnetically, contributing to its destabilization. The magnetic anisotropy of the interchain interactions as well as of the local 4f wavefunctions characterizes the magnetic properties underlying the ferromagnetic transition and the quantum critical behavior in CeRh6Ge4.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerium based ferromagnets are materials of high fundamental interest. The highly localized 4f electrons of cerium can show Kondo lattice behavior where the localized spin is screened by conduction electrons and forms a Kondo singlet, leading to a correlated paramagnetic ground state1. This behavior is controlled by the strength of the hybridization between the localized moment and the conduction electrons. In the case of weak hybridization, the localized 4f electrons can interact via the Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida (RKKY) interaction which is mediated by conduction electrons. The result can be magnetically ordered states.

A particularly interesting possibility in the case of cerium magnetism is a ferromagnetic ground state which is realized in a small but growing number of compounds such as CeRuPO2, CeRu2Al2B3 and CePt4. The fact that ferromagnetic ordering temperatures TC are typically small means that there often are experimentally accessible tuning parameters like pressure that allow suppression of TC to zero temperature, providing access to a quantum phase transition instead of the usual thermal phase transition. The properties of materials near such a quantum critical point are highly nontrivial and interesting5. Ferromagnetic quantum critical points are often first order as in UGe26 or in UCoAl7. Here, we plan to study, CeRh6Ge4 which is a rare example of a Kondo lattice system with ferromagnetic order at ambient pressure and a second-order ferromagnetic quantum critical point that is accessible at elevated pressures.

CeRh6Ge4 exhibits a ferromagnetic transition at TC = 2.5 K8. This compound has attracted significant interest due to the emergence of a ferromagnetic quantum critical point (QCP) under pressure9,10. To realize a QCP associated with a ferromagnetic transition, magnetic anisotropy plays a key role10, as it helps to avoid a first-order transition. Theoretical investigations into the realization of a ferromagnetic QCP have subsequently explored the absence of inversion symmetry11, the influence of the spin-orbit coupling12, and the role of nonsymmorphic symmetry13. In this paper, we apply a recently developed first-principles method for calculating the magnetic susceptibility and derive low-energy effective interactions. We demonstrate that the exchange interactions responsible for the ferromagnetic transition are highly anisotropic, stabilizing the in-plane ferromagneitc moment of 4f electrons.

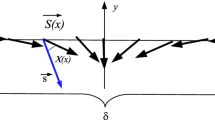

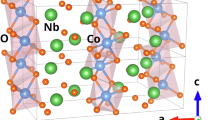

CeRh6Ge4 crystallizes in a LiCo6P4-type structure with space group \(P\bar{6}m2\) (No. 187)14 as illustrated in Fig. 1. The Ce atoms occupy the 1a site with a three-fold rotational symmetry, corresponding to the point group D3h. A clear anomaly in the specific heat indicates a phase transition at T = TC = 2.5 K8. Magnetization measurements confirm the onset of ferromagnetism, with a spontaneous moment of 0.34 μB/Ce. Neutron scattering and μSR experiments reveal that the ordered moment lies within the a-b plane as shown in Fig. 1c15. In the paramagnetic state, the magnetic susceptibility follows the Curie-Weiss law with an effective moment of 2.35 μB/Ce. The electronic and magnetic properties of CeRh6Ge4 have been further explored using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)16, quantum oscillation measurements17, chemical substitution at the Ce site18 and the Ge site19, and thermopower measurements20.

a Side view showing the coordination of Ce and Rh. b View along c showing the symmetry of the Ce site. c Spin configuration proposed in neutron scattering and μSR experiments15.

Theoretically, two contrasting approaches exist for describing 4f electron magnetism, depending on whether the 4f electrons are treated as itinerant or localized. In the case of CeRh6Ge4, quantum oscillation measurements have shown that the Fermi surface is well described by models assuming localized 4f electrons17. Consistently, ARPES measurements have also detected signatures characteristic of a localized 4f state16. These experimental findings indicate that the localized picture provides a suitable starting point for understanding the electronic and magnetic properties of CeRh6Ge4.

We employ a method based on dynamical mean field theory combined with density functional theory (DFT+DMFT). Our calculation procedure which successfully reproduced the antiferro-quadrupolar ordering in CeB621 is the following. First, we perform a DFT calculation in which the 4f electrons are treated as itinerant. Based on this electronic structure, we introduce the local Coulomb repulsion among the 4f electrons via DMFT, leading to 4f electrons with localized nature. We then calculate the momentum-dependent multipolar susceptibilities associated with the local 4f degrees of freedom. By identifying the divergence in the susceptibility, we determine the transition temperature and the corresponding order parameter. Using this approach, we will demonstrate that the ferromagnetic transition in CeRh6Ge4 can be reproduced within the localized 4f electron framework.

Results

Electronic structure

Figure 2a shows the electronic band structure calculated with fully relativistic density functional theory calculations using the full potential local orbital (FPLO) basis22 in combination with a generalized gradient approximation exchange correlation functional23. We used the crystal structure reported in ref. 14. The lattice parameters are a = 7.154 Å and c = 3.855 Å. The path along the high symmetry points of the hexagonal space group of CeRh6Ge4 is shown in Fig. 2c. Figure 2b shows the species resolved densities of states. We use projective Wannier functions within FPLO24,25 to obtain a tight-binding model with 108 orbitals (including spin degrees of freedom) consisting of Ce 4f, Ce 5d, Rh 4d, and Ge 4p. Comparison of black and blue lines in Fig. 2a indicate that the fit is excellent in a wide energy range around the Fermi level. The maximum hybridization strengths between Ce 4f and Rh 4d and between Ce 4f and Ge 4p are 0.10 eV and 0.15 eV respectively, while the direct 4f–4f hopping is at most 2.9 meV.

a Fully relativistic DFT bandstructure (blue) with a 108 band tight binding fit (black). b Corresponding density of states of CeRh6Ge4. The maximum of the very sharp Ce 4f density of states of 76.2 states/eV/f.u. is not shown. c Brillouin zone of CeRh6Ge4 with the high symmetry paths shown in (a). d Single-particle excitation spectrum A(k, ω) in DFT+DMFT calculated at T = 0.01 eV. e Corresponding k-summed spectrum A(ω).

We performed magnetic calculations within LDA and GGA. The quantization axis of the magnetic moment was chosen parallel to the a axis or the c axis. In both cases, the total energy Etot takes minimum at m = 0. This result demonstrates that the ferromagnetic state is not reproduced within LDA and GGA.

Figure 3 compares the crystalline electric field (CEF) energy levels of 4f electrons obtained from GGA calculations and experiment. The local symmetry at the Ce site is described by the point group D3h under which the j = 5/2 manifold splits into three Kramers doublets: \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\), \(\left\vert \pm 3/2\right\rangle\), and \(\left\vert \pm 5/2\right\rangle\). Experimentally, the ground state is \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\), with the first and second excited states being \(\left\vert \pm 3/2\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \pm 5/2\right\rangle\), respectively15. The excitation energies are Δ1 = 5.8 meV and Δ2 = 22.1 meV, as determined from the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility. In contrast, our DFT calculations yield the opposite level ordering. Furthermore, the energy scale of the splitting is around 100 meV, which is 5 times larger than the experimental one. The CEF levels in DFT do not reproduce the experimental magnetic anisotropy. To address this discrepancy, we incorporate the experimentally determined CEF level scheme directly into our tight-binding Hamiltonian.

a Scheme derived from experiment15. b CEF level scheme obtained by our DFT calculations.

We treat the Coulomb repulsion in the 4f orbitals within the DFT+DMFT framework (see Methods section for details)26,27,28. We exclude the total angular momentum j = 7/2 states of the 4f orbitals, which lie approximately 0.3 eV above the j = 5/2 states due to the spin-orbit coupling. The DFT+DMFT calculations are therefore applied to the remaining 100 orbitals. Figure 2d shows the single-particle excitation spectrum A(k, ω) calculated with parameters U = 6.92 eV, JH = 0.8 eV, and ϵf = −2.7 eV. These values were chosen to ensure consistency between our results for A(k, ω) and experiments. The Hund’s coupling JH is adopted from ref. 29. The 4f0 peak in A(k, ω) has been observed at ω = −Δ− with Δ− = 2.7 eV in photoemmision experiments16. The lowest excitation energy from the 4f1 to the 4f2 configurations, Δ+ = 3.1 eV, has been reported for elemental Ce30 and confirmed by BIS experiments31. We determined the values of U and ϵf to reproduce both Δ− and Δ+ in our spectrum. The resultant spectrum in Fig. 2e exhibits no 4f spectral weight at the Fermi level, meaning that the 4f electrons are fully localized. The conduction band near the Fermi level primarily consists of Rh-4d and Ge-4p states.

Magnetic properties

To investigate the phase transitions in CeRh6Ge4, we calculate the momentum-dependent static susceptibility, defined as

where m = +5/2, ⋯ , −5/2 denotes the z component of j = 5/2 orbitals, N is the number of lattice sites, the argument τ indicates the imaginary-time evolution in the Heisenberg picture, and the operator \({O}_{i,mm{\prime} }\) is given by

We evaluate \({\chi }_{{m}_{1}{m}_{2}{m}_{3}{m}_{4}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) defined in Eq. (1) using the strong-coupling-limit (SCL) formula (see Methods section for details). The momentum-dependent susceptibilities in the SCL formula are given by

where all quantities with hat are matrices indexed by the combined indices (m1m2) and (m3m4). \({\hat{\chi }}_{{{{\rm{loc}}}}}\) denotes the local susceptibility calculated from the atomic system, and \(\hat{I}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) represents the intersite exchange interactions.

Figure 4a shows the eigenvalues χλ(q) of the susceptibility matrix \(\hat{\chi }({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\). A total of 36 eigenvalues are classified into 9 groups. The number of modes in each group and the relevant CEF levels are summarized in Table 1. We determined the symmetry of the eigenmodes by analyzing the eigenvectors. The group with the largest susceptibility corresponds to fluctuations within the CEF ground-state doublet \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\). This Kramers doublet carries magnetic degrees of freedom, which are classified into \({A}_{2}^{{\prime} -}\) and E″− representations in the point group D3h. Groups with dimension 8 involve hybridization between two CEF doublets. The corresponding density operators, such as \({f}_{1/2}^{{{\dagger}} }{f}_{3/2}\), can be classified into pairs of the electric ( + ) and magnetic ( − ) multipole operators32. Groups with dimension 1 consist of the totally symmetric representation \({A}_{1}^{{\prime} +}\). Among them, the lowest fluctuation mode, which exhibits nearly zero susceptibility, corresponds to charge fluctuations. The remaining modes are higher-order electric multipoles, including quadrupole and hexadecapole.

a The eigenvalues of the susceptibility matrix, χλ(q) computed at T = 0.01 eV. b The magnetic susceptibility χξ(q) within \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\) states. c The temperature dependence of the inverse of the ferromagnetic susceptibility, 1/χξ(0) with ξ = x, y. The vertical dashed lines indicate the energy of the CEF level splitting Δ1 and Δ2 given in Fig. 3a. The solid lines show the fitting by the high-T and low-T expressions in Eqs. (9) and (11), respectively. The inset shows a zoom-up of the low-temperature region. d The temperature dependence of the inverse of the susceptibility χJ that corresponds to experiments.

We focus on the leading fluctuations, which originate from the CEF ground-state doublet \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\). The corresponding eigenvectors of the susceptibility matrix are well described by the Pauli matrices acting within the \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\) subspace. To capture the magnetic fluctuations, we introduce the magnetic dipole operator projected onto the \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\) states as

where ξ = x, y, z and the matrix \({\hat{M}}_{\xi }\) is defined by

The susceptibility corresponding to the fluctuation of Miξ can be evaluated by

Figure 4b shows χξ(q) on the q-path. These quantities closely follow the leading eigenvalues χλ(q) presented in Fig. 4a, confirming that χξ(q) effectively captures the dominant magnetic fluctuations. The strongest fluctuations appear in χx(q) and χy(q) at q = 0, corresponding to ferromagnetic fluctuations of the in-plane magnetic moment Mx and My. The difference between χx(0) and χy(0) is small (less than 1%), and we focus on the x component hereafter. Furthermore, χx(q) is significantly enhanced in the qz = 0 plane (Γ–M–K–Γ) compared to the qz = 1/2 plane (A–L–H–A). This indicates that the c axis bond favors ferromagnetic configuration.

Figure 4c shows the temperature dependence of the inverse of the ferromagnetic susceptibility, 1/χx(0). In the high-temperature region (T ≫ Δ2), the six states of j = 5/2 are effectively degenerate due to thermal fluctuations. As a result, χx(0) follows the Curie-Weiss law represented by

where the Curie constant C6 is evaluated under the assumption of no CEF splitting as

A fit to the numerical data yields the Curie-Weiss temperature of Θ = 7.5 meV. In the low-temperature region (T ≪ Δ1), on the other hand, only the lowest CEF doublet is thermally occupied. In this limit, χξ(q) can be represented by

and the Curie constant C2 is evaluated only with the \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\) states as

Fitting the low-temperature data gives a ferromagnetic transition temperature of TC = 0.28 meV ≈3.2 K. It is important to note that this first principle result for TC is very close to the experimental value of TC = 2.5 K. This overestimation by approximately 0.7 K or 30% is consistent with previous findings for CeB6, where the SCL method similarly overestimated the transition temperature of the antiferro-quadrupolar ordering21.

We note that the magnetic susceptibility χξ defined in Eq. (8) differs from the quantity measured in experiments. The experimentally measured magnetic susceptibility χJ is defined by

under the Zeeman field \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{Z}=-mH\). For a magnetic field parallel to the z axis, the magnetic moment operator m is given by m = −gJμBjz, where jz is the z-component of the total angular momentum operator with j = 5/2 and gJ is the Landé g-factor, which is given by gJ = 6/7 for the Ce3+ ion. χJ can be computed from \({\chi }_{{m}_{1}{m}_{2},{m}_{3}{m}_{4}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) as in Eq. (2). The explicit form for χJ is thus given by

The cases with the magnetic field parallel to the x- and y-axes are computed in a similar manner. Figure 4d shows the temperature dependence of 1/χJ. The overall behavior, including the anisotropy and the strong T-dependence for H∥z below T ≃ Δ1, is consistent with the experiments15.

We now turn to the intersite interactions. To isolate the effective interaction between \(\left\vert \pm 1/2\right\rangle\) states, we project the full momentum-dependent interaction \({I}_{{m}_{1}{m}_{2}{m}_{3}{m}_{4}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) onto the dipole channel using the same transformation as in Eq. (8). The resulting quantity Iξ(q) represents the exchange interaction within the ground-state doublet. Figure 5a shows Iξ(q) along the representative q-path. Its q-dependence closely follows that of χξ(q), in agreement with Eq. (3), which indicates that the q-dependence of χξ(q) originates entirely from Iξ(q). The magnitude of the ferromagnetic interaction is approximately 0.7 meV, which is comparable to the ferromagnetic transition temperature TC.

a The momentum-dependent effective interaction Iξ(q). b Linear-scale plot of the effective inter-site interaction Iξ(i, j) as a function of the distance ∣rij∣ = ∣Ri − Rj∣. c A log-log plot with the line showing Iξ(i, j) ∝ ∣rij∣−3. The vertical dashed lines show the Ce-Ce distances with the labels n1n2n3 indicating r = n1a + n2b + n3c.

To gain real-space insight into the magnetic interactions, we computed Iξ(q) over the entire Brillouin zone and performed a Fourier transform to obtain the intersite interactions Iξ(i, j). This quantity defines the effective Heisenberg Hamiltonian for the projected dipole moments Miξ, given by

Figure 5b shows Iξ(i, j) as a function of intersite distance ∣Ri − Rj∣. Explicit values of Iξ(i, j) are presented in Table 2. The strongest interaction occurs along the c axis, corresponding to the nearest-neighbor sites. This bond exhibits a sizable ferromagnetic exchange that is isotropic in spin space. The next-nearest-neighbor interactions, located in the a–b plane, exhibit pronounced spin anisotropy. Specifically, the in-plane components Mx and My are coupled ferromagnetically, while the out-of-plane component Mz shows antiferromagnetic coupling. Figure 5c presents a log-log plot of ∣Iξ(i, j)∣, revealing a power-law decay Iξ(i, j) ~ ∣Ri − Rj∣−3. This behavior is characteristic of the Ruderman–Kittel–Kasuya–Yosida (RKKY) interaction, confirming its role as the primary mechanism driving the magnetic ordering in CeRh6Ge4.

Discussion and conclusions

The magnetic structure obtained by our calculations is illustrated in Fig. 1c. The effective interaction responsible for this structure can be described as follows. By retaining interactions up to the second nearest neighbors in Eq. (15), we obtain the effective Heisenberg model of spin S = 1/2 as

where the first and the second summations represent nearest-neighbor pairs along the c axis and within the a–b plane, respectively. From the numerical results in Table. 2, we obtain Jc = 0.45 meV, Jab/Jc = 0.087, and r = 0.41 (note that J’s are twice as large as Iξ). The first term represents the strong coupling of the Ce moments along the c axis, leading to the formation of ferromagnetic chains. These chains are aligned by weaker inter-chain interactions within the a–b plane (the second term), which collectively stabilize the ferromagnetic configuration shown in Fig. 1c. Although the in-plane components of the moment are coherently aligned, the c axis component is influenced by geometrical frustration arising from the inter-chain antiferromagnetic coupling. This frustration suppresses out-of-plane magnetic order and is reflected in the momentum dependence of the interaction Iz(q), whose maximum appears at the M point of the Brillouin zone [Fig. 5a].

In ref. 10, the strange-metal behavior around the QCP is analyzed by the Heisenberg Hamiltonian, assuming XXZ-type anisotropy with weak Sz interaction. Our microscopic derivation of the effective Heisenberg model supports their starting point, which leads to a linear dispersion of the magnetic excitations. Furthermore, the weak inter-chain coupling guarantees a second-order phase transition, enabling the emergence of the QCP under pressure10.

A direct calculation of a QCP under external pressure requires substantial computational effort. As described by the Doniach phase diagram33, the ordering temperature is suppressed as a result of competition between long-range order induced by the RKKY interactions and the paramagnetic heavy-Fermion state driven by the Kondo effect. Our calculations using the atomic self-energy within the Hubbard-I approximation neglect the Kondo effect. Consequently, applying the present calculations under pressure simply leads to an increase in the Curie temperature associated with the reduction of the lattice constant. To estimate the Kondo temperature TK, we employed the continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo method34 as an impurity solver. While we observed signs of a low-energy quasiparticle peak emerging below T ≃ 1 meV, determining TK and its pressure dependence with sufficient accuracy remains challenging.

Finally, we discuss the origin of the ferromagnetic transition in CeRh6Ge4. The q-dependence of the RKKY interaction is governed by the Fermi surface of conduction electrons. Fig. 6 displays the Fermi surface evaluated from A(k, ω) at ω = 0. As shown in Figures 6a–e, the Fermi surface is isotropic in the kx–ky plane. The cut at the ky = 0 plane in Fig. 6f reveals a Fermi surface that spans the entire kz range, indicating a deformed cylindrical shape—characteristic of two-dimensional systems. These features are consistent with a quantum oscillation measurement, which showed that the observed Fermi surface is consistent with the DFT results assuming localized 4f electrons17. It is known that the two-dimensional free electrons exhibit a plateau in the static susceptibility χ0(q) for ∣q∣ < 2kF, followed by a decay for ∣q∣ > 2kF, where kF is the Fermi wavenumber. We suggest that the weakly three-dimensional cylindrical Fermi surface gives rise to the peak at the Γ point in our numerical results.

In summary, we investigated the ferromagnetism in CeRh6Ge4 using the DFT+DMFT method, treating the Ce 4f electrons as localized. The intersite exchange interactions, evaluated using the strong-coupling-limit (SCL) formula, revealed dominant ferromagnetic coupling along the c axis, forming spin chains that are isotropic in spin space. In contrast, the inter-chain coupling is anisotropic: ferromagnetic for the in-plane moment and antiferromagnetic for the out-of-plane moment. These interactions give rise to a magnetic structure in which the magnetic moment is aligned within the a–b plane.

The calculated transition temperature is in reasonable agreement with the experimental value, although the mean-field nature of the intersite interaction in DMFT tends to overestimate the transition temperature. Our results provide theoretical support for anisotropic exchange interactions between localized 4f moments, offering a foundation for understanding the anomalous metallic behavior observed near the ferromagnetic QCP under pressure.

Methods

DFT+DMFT method

The DFT+DMFT method incorporates local electronic correlations within a specific shell, building upon the DFT electronic structure26,27,28. The single-particle Green’s function matrix \(\hat{G}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}},\omega )\) is defined as

Here, all quantities with hats represent matrices in the Wannier-function basis. \(\hat{I}\) is the identity matrix, and μ is the chemical potential. \(\hat{H}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\) is the tight-binding Hamiltonian obtained from DFT, where the on-site energies of the 4f orbitals are adjusted to reproduce the experimental CEF energy level scheme. \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{{{{\rm{DC}}}}}\) is the double-counting correction that accounts for correlation effects already included in DFT. Following ref. 21, we represent it as

where \(\left\vert \, f\right\rangle \left\langle f\right\vert\) is the projection operator onto the 4f subspace. The parameter ϵf is determined along with the interaction parameters.

The local self-energy \(\hat{\Sigma }(\omega )\) is defined on the 4f orbitals. We employ the fully rotationally invariant Slater interactions, characterized by four Slater integrals Fk with k = 0, 2, 4, 6. These are converted from two intuitive parameters: the direct Coulomb interaction U and the Hund’s exchange coupling JH35. To compute \(\hat{\Sigma }(\omega )\), we solve the atomic problem within the Hubbard-I approximation, which neglects hybridization with the conduction electrons. These calculations were done using the open-source software DCore36, which is implemented with TRIQS37 and DFTTools38 libraries. The exact diagonalization of the atomic problem was solved using pomerol39. The number of k points in the DFT+DMFT calculations is 24 × 24 × 42.

SCL formula for susceptibility

We evaluate \({\chi }_{{m}_{1}{m}_{2}{m}_{3}{m}_{4}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) defined in Eq. (1) using the strong-coupling-limit (SCL) formula, which is derived from the Bethe-Salpeter (BS) equation within DMFT21,40. Unlike the full BS equation, the SCL formula does not require computation of the vertex function, significantly simplifying the calculation. When applied to CeB6, the SCL formula yields quantitative agreement with the results obtained from the full BS equation21, demonstrating its reliability in systems with localized 4f electrons.

The momentum-dependent susceptibilities in the SCL formula are given by Eq. (3). To evaluate \(\hat{I}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\), we employ the two-pole approximation (SCL3)21,40, which captures the virtual excitations around the 4f1 configuration. We use excitation energies Δ+ = 3.1 eV and Δ− = 2.7 eV, corresponding to excitations from 4f1 states to 4f2 and 4f0 configurations, respectively, in A(k, ω).

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author (JO) on reasonable request.

Code availability

The DFT code used in this study is available from https://www.fplo.de/. The DMFT calculations for the single-particle excitation spectrum are performed using DCore, which is available from https://github.com/issp-center-dev/DCore. The calculations of the susceptibility and effective interactions are performed by ChiQ, which is now open in https://github.com/issp-center-dev/ChiQ.

References

Hewson, A. C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions. (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Krellner, C. et al. CeRuPO: a rare example of a ferromagnetic Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. B 76, 104418 (2007).

Baumbach, R. E. et al. CeRu2Al2B: a local-moment 4f magnet with a complex T-H phase diagram. Phys. Rev. B 85, 094422 (2012).

Fontes, J. L. J. M. B. et al. Quantum critical behavior in a CePt ferromagnetic Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. B 72, 035129 (2005).

Brando, M., Belitz, D., Grosche, F. M. & Kirkpatrick, T. R. Metallic quantum ferromagnets. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 025006 (2016).

Huxley, A. et al. UGe2 a ferromagnetic spin-triplet superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 63, 144519 (2001).

Aoki, D. et al. Ferromagnetic quantum critical endpoint in UCoAl. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 80, 094711 (2011).

Matsuoka, E. et al. Ferromagnetic transition at 2.5 K in the hexagonal Kondo-lattice compound CeRh6Ge4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 073704 (2015).

Kotegawa, H. et al. Indication of ferromagnetic quantum critical point in Kondo lattice CeRh6Ge4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 093702 (2019).

Shen, B. et al. Strange-metal behaviour in a pure ferromagnetic Kondo lattice. Nature 579, 51 (2020).

Kirkpatrick, T. R. & Belitz, D. Ferromagnetic quantum critical point in noncentrosymmetric systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 147201 (2020).

Miserev, D., Loss, D. & Klinovaja, J. Instability of the ferromagnetic quantum critical point and symmetry of the ferromagnetic ground state in two-dimensional and three-dimensional electron gases with arbitrary spin-orbit splitting. Phys. Rev. B 106, 134417 (2022).

Shin, S., Ramires, A., Pomjakushin, V., Plokhikh, I. & Pomjakushina, E. Ferromagnetic quantum critical point protected by nonsymmorphic symmetry in a Kondo metal. Nat. Commun. 15, 8423 (2024).

Voßinkel, D., Niehaus, O., Rodewald, U. C. & Pöttgen, R. Bismuth flux growth of CeRh6Ge4 and CeRh2Ge2 single crystals. Z. Naturforsch. B 67, 1241 (2012).

Shu, J. W. et al. Magnetic order and crystalline electric field excitations of the quantum critical heavy-fermion ferromagnet CeRh6Ge4. Phys. Rev. B 104, L140411 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Anisotropic c−f hybridization in the ferromagnetic quantum critical metal CeRh6Ge4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 216406 (2021).

Wang, A. et al. Localized 4f-electrons in the quantum critical heavy fermion ferromagnet CeRh6Ge4. Science Bulletin 66, 1389 (2021).

Xu, J.-C. et al. Ce-site dilution in the ferromagnetic Kondo lattice CeRh6Ge4. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38, 087101 (2021).

Zhang, Y. J. et al. Suppression of ferromagnetism and influence of disorder in silicon-substituted CeRh6Ge4. Phys. Rev. B 106, 054409 (2022).

Thomas, S. M. et al. Probing quantum criticality in ferromagnetic CeRh6Ge4. Phys. Rev. B 109, L121105 (2024).

Otsuki, J., Yoshimi, K., Shinaoka, H. & Jeschke, H. O. Multipolar ordering from dynamical mean field theory with application to CeB6. Phys. Rev. B 110, 035104 (2024).

Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis band-structure scheme. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1743 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Eschrig, H. & Koepernik, K. Tight-binding models for the iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 104503 (2009).

Koepernik, K., Janson, O., Sun, Y. & van den Brink, J. Symmetry-conserving maximally projected Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 107, 235135 (2023).

Georges, A., Kotliar, G., Krauth, W. & Rozenberg, M. J. Dynamical mean-field theory of strongly correlated fermion systems and the limit of infinite dimensions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 13 (1996).

Held, K., McMahan, A. K. & Scalettar, R. T. Cerium volume collapse: results from the merger of dynamical mean-field theory and local density approximation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 276404 (2001).

Kotliar, G. et al. Electronic structure calculations with dynamical mean-field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 865 (2006).

Locht, I. L. M. et al. Standard model of the rare earths analyzed from the Hubbard I approximation. Phys. Rev. B 94, 085137 (2016).

Herbst, J. F., Watson, R. E. & Wilkins, J. W. Relativistic calculations of 4f excitation energies in the rare-earth metals: further results. Phys. Rev. B 17, 3089 (1978).

Lang, J. K., Baer, Y. & Cox, P. A. Study of the 4f and valence band density of states in rare-earth metals. II. Experiment and results. J. Phys. F: Met. Phys. 11, 121 (1981).

Kusunose, H., Oiwa, R. & Hayami, S. Symmetry-adapted modeling for molecules and crystals. Phys. Rev. B 107, 195118 (2023).

Doniach, S. The Kondo lattice and weak antiferromagnetism. Physica B+C 91, 231 (1977).

Gull, E. et al. Continuous-time Monte Carlo methods for quantum impurity models. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 349 (2011).

Anisimov, V. I., Aryasetiawan, F. & Lichtenstein, A. I. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: the LDA + U method. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9, 767 (1997).

Shinaoka, H., Otsuki, J., Kawamura, M., Takemori, N. & Yoshimi, K. DCore: integrated DMFT software for correlated electrons. SciPost Phys. 10, 117 (2020).

Parcollet, O. et al. TRIQS: a toolbox for research on interacting quantum systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 196, 398 (2015).

Aichhorn, M. et al. TRIQS/DFTTools: a TRIQS application for ab initio calculations of correlated materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 204, 200 (2016).

Antipov, A. E., Krivenko, I., and Iskakov, S. aeantipov/pomerol: 1.2. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.825870 (2017).

Otsuki, J., Yoshimi, K., Shinaoka, H. & Nomura, Y. Strong-coupling formula for momentum-dependent susceptibilities in dynamical mean-field theory. Phys. Rev. B 99, 165134 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants No. 21H01003, No. 21H01041, No. 23H04869, and No. 24H01668. A part of the computation in this work has been done using the facilities of the Supercomputer Center, the Institute for Solid State Physics, the University of Tokyo (2024-Bb-0043).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by J.O. S.I. performed the calculations with contributions from all authors. SI and JO analysed and discussed the results and drafted the manuscript with contributions from A.K. and H.O.J. All authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Carmine Autieri, Alexey V. Ushakov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Itokazu, S., Kirikoshi, A., Jeschke, H.O. et al. From localized 4f electrons to anisotropic exchange interactions in ferromagnetic CeRh6Ge4. Commun Mater 6, 269 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00998-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00998-7