Abstract

Niobium nitride is renowned for its exceptional mechanical, electronic, magnetic, and superconducting properties. The ideal 1:1 stoichiometric δ-NbN cubic phase, however, is known to be dynamically unstable, and repeated experimental observations have indicated that vacancies are necessary for its stabilization. In this work, we demonstrate that when the structure is fully relaxed and allowed to distort under quantum anharmonic effects, a stable cubic phase with space group \(P\bar{4}3m\) emerges — 65 meV/atom lower in free energy than the δ phase. This discovery is enabled by state-of-the-art first-principles calculations accelerated by machine-learned interatomic potentials. To evaluate the vibrational properties with quantum anharmonic effects accounted for, we use the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics spectral energy density methods. Electron-phonon coupling calculations based on the anharmonic phonon dispersion yield a superconducting transition temperature of 20 K, which aligns with experimentally reported values for near-stoichiometric NbN. These findings challenge the long-held assumption that vacancies are essential for stabilizing cubic NbN and point to the potential of synthesizing the ideal 1:1 stoichiometric phase as a route to achieving enhanced superconducting performance in this technologically significant material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal carbides and nitrides combine exceptional mechanical properties with diverse electronic, magnetic and superconducting behavior1,2,3,4,5,6. Among these materials, niobium nitride (NbN) has attracted significant attention due to its structural complexity and technological relevance. NbN exhibits a rich phase diagram due to its ability to accommodate varying nitrogen concentrations and vacancy contents. Typically, the nitrogen content is quantified by x in the formula NbNx, representing the ratio of nitrogen to niobium. With increasing x, a variety of phases has been reported: the bcc solid solution α-NbN (NbNx with x < 0.40, \(Im\bar{3}m\)), the hexagonal β-NbN (\(P\bar{6}m2\), x = 0.40-0.50), the tetragonal γ-NbN (Cmcm, x = 0.75-0.80), the hexagonal η-NbN (P63/mmc, x = 0.80-0.95), the fcc δ-NbN (\(Fm\bar{3}m\), x = 0.88-0.98 and x = 1.015-1.062), and the hexagonal ϵ-NbN (P63/mmc, x = 0.92-1.00). Additional phases such as tetragonal Nb4N5, hexagonal \(\delta {\prime}\)-NbN (P63/mmc, x = 0.93-0.98), and hexagonal \(\epsilon {\prime}\)-NbN (P63/mmc, at x = 1) have also been observed.

Although ϵ-NbN is predicted to be the ground-state structure at x = 1 from first-principle calculations, δ-NbN is the phase most commonly observed under ambient-pressure conditions. It also exhibits the highest superconducting transition temperature (Tc), reaching up to 17 K. Other superconducting phases include γ-NbN and Nb4N5, though with lower Tc values7,8,9. Despite the emergence of superconducting materials with higher Tc10,11,12,13,14, NbN remains a subject of intense study because of its high critical magnetic field, robust chemical and mechanical stability, and ease of synthesis and processing15. These attributes have led to applications in superconducting radiofrequency cavities16, hot electron photodetectors17, Josephson junctions18, qubits19, and superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors20,21.

Typically, δ-NbN is synthesized with a random distribution of nitrogen vacancies, which induce structural distortions that stabilize the δ phase. As vacancy concentration decreases, these distortions diminish, resulting in a higher Tc until reaching a critical threshold where the structure becomes unstable and transforms into the ϵ-NbN phase7. This interplay between vacancy-induced distortions, structural stability, and superconducting properties highlights the importance of precise stoichiometric control.

In silico simulation of disorder and vacancies is computationally demanding because it necessitates the use of very large supercells in addition to statistical models22,23,24, thus, theoretical research focus has been mostly on the ideal 1:1 stoichiometry, where δ-NbN is dynamically unstable within the harmonic approximation. Previous work using the Korringa-Kohn-Rostoker Coherent Potential Approximation revealed that the presence of vacancies lowers the Fermi level and increases band smearing around it25. Building on this observation, applying a large electronic smearing, which can also serve as a first-order approximation for temperature effects, has been shown to eliminate the dynamic instability26,27. Similarly, within the virtual crystal approximation, the stabilization of cubic NbN has been achieved, yielding phononic properties that compare favorably with experimental data27.

In this study, we reexamine the δ-NbN structure and uncover, to the best of our knowledge, a previously unreported stable phase at 1:1 stoichiometry. We first demonstrate that the conventional δ structure remains unstable, even when quantum anharmonic effects are taken into account — specifically, the combined influence of quantum ionic motion (such as zero-point motion, absent in classical treatments) and the non-parabolic nature of the ionic potential — using the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation (SSCHA)28,29, and considering temperatures up to 300 K. By exploring the potential energy surface beyond the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, explicitly accounting for these quantum anharmonic effects, we identify a distinctly stable, displaced structure within the simple cubic cell. Our results from two complementary computational approaches, SSCHA and molecular-dynamics spectral energy density (MD-SED) calculations30,31, show excellent agreement, and are further supported by an independent ab initio random structure search (AIRSS)32,33. The identified structure features a reduced electronic density of states at the Fermi level. Moreover, the superconducting transition temperature (Tc), calculated using the isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg (ME) formalism, closely matches experimental values for bulk NbN close to the 1:1 stoichiometry.

These findings highlight the critical role of quantum anharmonicity, i.e. quantum ionic motion, phonon-phonon interactions, and the non-parabolic shape of the ionic potential, in stabilizing a new simple cubic phase of NbN, one that is thermodynamically more favorable than the δ phase, though still higher in energy than the ϵ phase. Beyond this insight, our results point to a promising new experimental direction. Whereas previous efforts have largely focused on tuning vacancy concentrations to tailor material properties, our findings suggest that synthesizing the ideal 1:1 stoichiometric cubic phase could offer a more direct path to enhancing superconducting performance.

Results and discussion

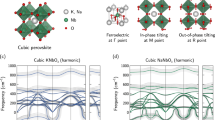

We begin our discussion by examining the phonon and electron-phonon properties of δ-NbN within the harmonic approximation. For the ideal 1:1 stoichiometry, several imaginary modes appear over large portions of the Brillouin zone, as shown in Fig. 1a. This indicates that the structure is dynamically unstable, in agreement with experimental observations that vacancies must be introduced to stabilize the δ phase. Modeling a structure that includes vacancies and the resulting disorder is extremely challenging because it requires the use of exceptionally large supercells, a task that quickly becomes computationally prohibitive due to the \({{\mathscr{O}}}({N}^{3})\)—\({{\mathscr{O}}}({N}^{4})\) scaling of current phonon and electron-phonon calculation methods based on plane-wave density-functional-theory (DFT), where N is the number of electrons in the computational cell34,35. Moreover, the prevalence of imaginary phonon frequencies throughout the Brillouin zone precludes reliable calculations of superconducting properties for the ideal structure.

Top row: (a) phonon dispersion of \(Fm\bar{3}m\) in the harmonic approximation (dotted black), (c) of \(Fm\bar{3}m\) in the harmonic approximation using a large smearing parameter (dashed green), and (e) \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure within SSCHA at 15 K (solid blue). The colored background in (e) shows the spectral density obtained with MD-SED. Bottom row: phonon DOS (dashed line, rescaled by a factor of 1/3 to enable same scales with the other quantities), and α2F (filled line) and cumulative λ (solid line) for (b) \(Fm\bar{3}m\) in the harmonic approximation, (d) \(Fm\bar{3}m\) in the harmonic approximation using a large smearing parameter, and (f) \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure within SSCHA at 15 K.

A commonly employed, computationally efficient workaround is to use an unusually large electronic smearing parameter in density-functional (perturbation) theory [DF(P)T] calculations. This approach effectively averages the Fermi surface and related properties, thereby yielding a harmonically stable phonon dispersion, as demonstrated in Fig. 1c, and showing good agreement with neutron diffraction data on NbN36. However, when the electron-phonon interaction is evaluated under this approximation and superconducting properties are subsequently calculated (see Table 1), the resulting critical temperature is significantly overestimated (27 K compared to the experimental value of about 16 K). This discrepancy leads us to conclude that the large smearing approximation does not adequately capture the true superconducting behavior of the system.

To better discern the shortcomings stemming from the harmonic approximation versus those arising from treating NbN as a perfect 1:1 crystal, we employed two complementary methods to evaluate its vibrational properties: the SSCHA and MD-SED. In the SSCHA framework, quantum ionic motion and anharmonic effects are explicitly incorporated to generate an effective harmonic description that more accurately reflects the true behavior of the system. In contrast, the MD-SED approach involves full molecular dynamics simulations to compute the spectral functions, thereby inherently capturing ionic motion and anharmonicity to all orders. More details on these methods and further references can be found in the Methods section and Supplementary Information (SI).

Because both SSCHA and MD-SED require performing hundreds of thousands of DFT calculations for full convergence, carrying out these computations solely at the DFT level is not feasible. Instead, we used DFT-calculated data to train high-fidelity machine-learned ab initio interatomic potentials that retain DFT-level accuracy in energies and forces. This approach enabled us to converge the SSCHA and MD-SED calculations with a computational speed-up of approximately 104-10537. Detailed information on the construction of these potentials and their validation benchmarks is provided in the Methods section and SI.

Employing the SSCHA on the δ-NbN phase, we still observed imaginary phonon frequencies even at temperatures up to 300 K (SSCHA calculations at 0 K reveal a lattice instability through the presence of imaginary phonon frequencies, regardless of the supercell size. At 300 K, calculations using a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of the primitive fcc unit cell yield fully positive phonon frequencies. However, larger supercells at the same temperature again show imaginary modes, suggesting that the smallest supercell size gives unconverged results.). This indicates that the ideal 1:1 stoichiometric δ phase is dynamically unstable, even when quantum ionic motion and anharmonic effects are incorporated, which is consistent with experimental findings that vacancies must be introduced to stabilize this phase.

Next, we allowed the entire structure to fully relax within the SSCHA framework, effectively permitting the system to follow the soft phonon mode displacements (Closer inspection of the structure obtained from the full SSCHA relaxation shows that its atomic arrangement can be described as a linear combination of the eigenvectors of a threefold-degenerate Γ mode with T1u symmetry in the conventional (primitive cubic) unit cell of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) structure. In the corresponding harmonic phonon calculation [Fig. 1a], this mode exhibits the largest imaginary frequency of approximately 7.4i THz at Γ.). This procedure led to the emergence of a cubic NbN phase with space group \(P\bar{4}3m\), which, based on our literature search, has not yet been reported.

Independently, extensive structure searches performed using AIRSS employing ephemeral data-derived potentials (EDDPs)38 with ‘shaken’ fcc supercells and unit cells of random structures with symmetry operations ranging from 2 to 48, identified the same \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure as one of the energetically most favorable, along with a few competitive variants exhibiting similar displacement features, but lower symmetries, such as tetragonal P42/mcm and P4/nmm (See SI Tables S2 and S3. Further analysis shows that P4/nmm and P42/mcm are dynamically unstable within both the harmonic approximation and SSCHA, further supporting \(P\bar{4}3m\) as the most physically plausible structure among those considered.). In addition, MD39, when averaged over representative snapshots, also converged to the same structure. The consistent identification of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase by three independent and conceptually distinct methods, SSCHA, MD, and AIRSS, provides compelling evidence that this structure represents the true quantum-mechanical ground state of stoichiometric cubic NbN.

The full structural details are provided in the SI, Fig. 2a provides a comparison between this simple cubic phase and the face-centered cubic δ phase, illustrating the structural distortions that result from free energy minimization when quantum ionic motion and anharmonicity are considered. Notably, the free energy of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase is 65 meV/atom lower than that of the δ phase, a significant difference. Nevertheless, the \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure remains only metastable, as the ϵ phase is still lower in free energy by 130 meV/atom. For the most relevant 1:1 stoichiometric phases, a detailed comparison of the free energies is given in Supplementary Table 1.

a Superposition of the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) (green) and \(P\bar{4}3m\) (blue) NbN crystal structures, showing all atoms of each structure in a single color. The overlay highlights how \(P\bar{4}3m\) distorts from the high-symmetry \(Fm\bar{3}m\) phase. Structures visualized with VESTA74. b Simulated XRD patterns using Cu Kα radiation75.

The anharmonic phonon dispersion of \(P\bar{4}3m\)-NbN, determined using SSCHA, is presented in Fig. 1e as solid blue lines, with the colored background showing the corresponding information obtained from MD-SED. While the overall dispersion resembles that of δ-NbN calculated within the harmonic approximation using large smearing parameters [Fig. 1(c)], several key differences are evident. The reduced structural symmetry in the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase lifts the high degeneracy observed in the δ phase, and we observe a phonon hardening for the mode around 6–8 meV as well as for the high-frequency optical branches.

We also note that harmonic phonon calculations for this structure show imaginary modes only in a narrow region of the Brillouin zone near Γ, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4. To understand the origin of this instability, we analyzed the free energy along the interpolation path from δ-NbN to \(P\bar{4}3m\), including the zero-point energy (ZPE) (see Supplementary Fig. 5). These calculations show that ZPE contributions are negligible, indicating that the stabilization of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase is primarily driven by the non-parabolic, anharmonic nature of the ionic potential.

To verify our findings and gain further insight, we performed equilibrium MD simulations and evaluated the vibrational properties using the MD-SED approach. This method fully and implicitly accounts for ionic motion and anharmonicity, making it one of the most rigorous and state-of-the-art techniques for determining vibrational properties31, second only to an exact description of quantum ions within ab initio path-integral MD40,41,42,43. Starting from the δ phase, the MD-SED analysis similarly shows that the high-symmetry structure is not maintained, with the ground state adopting a simple cubic symmetry. The phonon spectral function obtained from MD-SED, displayed as the background in Fig. 1e, agrees remarkably well with the phonon dispersion calculated via SSCHA. The convergence of results from these two complementary approaches lends strong support to the existence of the \(P\bar{4}3m\)-NbN phase.

Note: We extended our investigation to the closely related fcc phases of TiN and NbC (details are provided in the SI). For both compounds, no transition to an alternative phase was observed, in contrast to the behavior seen in NbN. In addition, we analyzed the electron localization function (ELF) for TiN, NbC, and NbN, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10.

In Fig. 3, we compare the electronic band structures and density of states (DOS) for the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) (green) and \(P\bar{4}3m\) (blue) phases. Both retain a metallic character, with states near the Fermi level (EF) predominantly derived from Nb d orbitals. However, the reduced symmetry of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase lifts several degeneracies evident in the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) band structure. In particular, at the X point, bands that cross the Fermi level in \(Fm\bar{3}m\) are split and pushed both above and below EF, effectively removing them from the Fermi surface in \(P\bar{4}3m\). Likewise, at Γ, these bands are pushed up in energy, which further lowers the DOS at EF. Indeed, as shown in the DOS panel on the right, the blue curve (corresponding to \(P\bar{4}3m\)) dips below the green curve (corresponding to \(Fm\bar{3}m\)) near EF. Such modifications of the electronic states around the Fermi level can have a direct impact on the superconducting properties of NbN.

Electronic band structures (a) and DOS (b) for the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) (green) and \(P\bar{4}3m\) (blue) phases. Fermi surfaces for \(Fm\bar{3}\) and \(P\bar{4}3m\), visualized with FermiSurfer76, are shown in (c) and (d), respectively. The color scale indicates the Nb d-orbital character, from yellow (0) to blue (1).

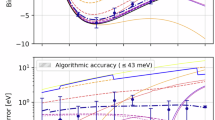

Using SSCHA phonon dispersions to compute electron-phonon coupling and GW44 to evaluate the Fermi-surface averaged screened Coulomb interaction μ, we determined the superconducting properties of \(P\bar{4}3m\)-NbN within the full-bandwidth isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg framework using ISOME45, complemented by fully anisotropic calculations with EPW46. The EPW results provide a detailed momentum-resolved map of the electron-phonon coupling strength λk, confirming that the interaction is nearly isotropic across the Fermi surface. This justifies the use of the isotropic approximation in ISOME, which we then employ to compute the superconducting gap Δ0(T) and obtain a critical temperature of Tc = 20 K, as shown in Fig. 4. This result compares much more favorably with the experimentally obtained Tc ≈ 16 K for near-stoichiometric bulk NbN than calculations that use large electronic smearing to artificially stabilize the δ phase, which yield Tc = 27 K. Considering the experimental trend of increased Tc with decreasing vacancy concentration, our results suggest that achieving stoichiometric 1:1 cubic NbN could lead to even higher superconducting transition temperatures.

Temperature dependence of the superconducting gap Δ0 from isotropic ME calculations45. Results for the P\(\bar{4}3m\) and Fm\(\bar{3}m\) phases are shown as dots and triangles, respectively. Dashed lines are guides to the eye. The inset shows the P\(\bar{4}3m\) Fermi surface, visualized with FermiSurfer76 and colored by λk from an anisotropic ME calculation46,73.

Note: To assess the importance of the electronic dispersion near the Fermi level, we computed superconducting critical temperatures employing the infinite-bandwidth-constant-DOS (cDOS) and the finite-bandwidth-energy-dependent-DOS (vDOS) approximations within the isotropic ME framework (for more details see ref. 45). As stated in Table 1, both \(Fm\bar{3}m\) and \(P\bar{4}3m\) phases yield nearly identical Tc values across the two treatments.

The fact that the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase is dynamically stable, thermodynamically more favorable, and shows superconducting properties that align well with experimental findings raises the question of whether this phase has been observed experimentally.

An extensive literature search7,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62 reveals surprisingly few reports characterizing a high-quality, low vacancy-concentration cubic phase of NbN. In the few studies that include X-ray or neutron diffraction data, the additional weak diffraction peaks associated with the \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure, as shown in Fig. 2b, are absent47,48,58. However, high-pressure measurements below 6 GPa reveal faint traces of a diffraction feature around the expected 110 reflection of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase. In contrast, no signature is observed at the 100 reflection2,63.

One plausible explanation for the elusive nature of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure is the presence of local distortions within the crystal. Random displacements of Nb and N atoms may arise due to vacancies of nitrogen atoms typically reported for δ-NbN, with stoichiometry in the range x ≈ 0.88-0.98. To date, only a single crystal study of δ-NbN has been reported, in which small static distortions of the Nb and N sublattices were observed. However, crystal structure elucidation was based exclusively on the expected diffraction peaks from the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) space group50.

In summary, our comprehensive computational investigation has revealed, to the best of our knowledge, a previously unreported, dynamically stable simple cubic phase of NbN (space group \(P\bar{4}3m\)), which is thermodynamically more favorable than the conventional δ-NbN phase. By employing both the SSCHA and MD-SED methodologies, we have shown that quantum anharmonic effects, in particular ionic potential non-parabolicity, stabilize this phase. The superconducting transition temperature (Tc = 20 K) calculated for the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase aligns much more closely with experimental observations for near-stoichiometric δ-NbN than previous estimates based on large electronic smearing approximations.

These findings challenge the conventional view that vacancies are necessary to stabilize cubic NbN and indicate that synthesizing the vacancy-free, distorted cubic 1:1 phase could offer a promising pathway to enhancing superconductivity in NbN, potentially reaching even higher critical temperatures. We encourage further experimental investigations, especially using high-resolution diffraction techniques on single NbN crystals or well-controlled powders, to validate the presence of the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase and fully assess its potential in superconducting applications. Future studies might also explore the impact of strain and chemical substitution on the phase stability and superconducting performance of NbN, as well as similarly explore the effects of quantum anharmonicity on the stability of other superconducting materials.

Methods

DFT and DFPT calculations

Electronic structure calculations are performed using density functional theory (DFT), as implemented in the Quantum ESPRESSO package64,65,66 with the PBE exchange-correlation functional67 and scalar-relativistic optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials68. A plane-wave basis set with a cutoff energy of 120 Ry was employed to expand the Kohn-Sham orbitals. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 18 × 18 × 18 k-grid. A Gaussian spreading of 0.01 Ry was applied for all structures, except for the large smearing calculations, where the smearing was set to 0.3 Ry. Structural relaxations were converged to 10−7 Ry in total energy and 10−6 Ry/a0 in forces. DFPT calculations were performed on a 4 × 4 × 4 q-grid with a self-consistency threshold of 10−14 Ry or lower.

AIRSS

We used AIRSS32,33, accelerated by EDDPs38, to search for novel NbN structures. The search was constrained to cells with 2–48 symmetry operations and 64 atoms with a 1:1 Nb:N ratio. Approximately 50,000 structures were generated and relaxed using EDDPs. The final structures were then filtered by an energy window of 100 meV per atom, and then by crystal system (removing hexagonal structures). The potential was trained on a dataset of single-point energies of approximately 12,000 structures, across a stoichiometry range of NbxNy, x,y=0-4. In addition, ‘marker’ structures of known low energy NbxNy structures were ‘shaken’ and added to the dataset, including the \(P\bar{4}3m\) structure. Single-point energy calculations were performed in CASTEP69, using the PBE exchange-correlation functional67 with on-the-fly generated C19 pseudopotentials, a plane-wave cutoff of 600 eV, and a k-point spacing of 0.04 × 2π/Å. The EDDP used a cut-off radius of 5.5 Å, a neural network of 2 hidden layers each with 20 nodes and a feature vector comprised of 16 and 4 polynomials for two- and three-body interactions respectively. We also performed relaxations of ‘shaken’ fcc cells with 2–6 formula units of NbN, directly within DFT. The best candidates from both searches were further refined using DFT calculations with CASTEP (see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). These used a slightly higher plane-wave cutoff of 800 eV, and a smaller k-point spacing of 0.02 × 2π/Å.

MTP

The potential was trained using the MLIP package70, at level 26, including eight radial basis functions and a cutoff Rcut = 5.0 Å. The training set consisted of 100 structures, including 50 layered system structures and 50 bulk structures, randomly chosen out of all individuals of the DFT SSCHA calculations for δ-NbN at 300 K. The set for the layered (bulk) system comprised 25 structures in the 2 × 2 × 1 (2 × 2 × 2) supercell and 25 structures in the 3 × 3 × 1 (3 × 3 × 3) supercell. We validated the potential on distorted structures around δ-NbN, as well as on structures near the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase, yielding an RMSE of 0.6-0.7 meV/atom for the total energy and 60-80 meV/Å for the force components. The graphical validation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

SSCHA

SSCHA calculations were carried out in constant-volume mode with structural relaxation, using the SSCHA Python package29 and following the workflow described in Refs. 37,71. Total energies, forces, and stress tensors for each ensemble configuration were computed using a purpose-trained MTP70, as described in the previous section.

We performed SSCHA simulations using 2 × 2 × 2, 3 × 3 × 3, and 4 × 4 × 4 supercells, considering both fixed and non-fixed symmetry. To reduce stochastic noise, the final ensemble for each supercell included 10,000 configurations. The ratio between the free energy gradient (with respect to the auxiliary dynamical matrix) and its stochastic error was reduced below 10−7. The Kong-Liu effective sample size was set to 0.6. Anharmonic phonon dispersions were extracted from the positional free energy Hessian, evaluated in the bubble approximation (excluding the fourth-order term). The phonon spectra obtained from the final two ensembles differ by less than 1 meV.

For the \(Fm\bar{3}m\) phase, calculations were performed on supercells of the primitive fcc unit cell, where all atoms occupy high-symmetry Wyckoff positions. Symmetry detection was enabled during the SSCHA minimization.

For the \(P\bar{4}3m\) phase, supercells were constructed from the conventional (simple cubic) unit cell. Symmetry detection was disabled both during the preparatory DFPT calculations and the SSCHA minimization, allowing all atomic positions to relax freely.

MD simulations and SED calculations

The MD-SED method allows us to obtain the phonon band structure directly from equilibrium MD simulations where anharmonic effects are fully accounted for. The method comprises applying a Fourier transform to the MD velocity field to obtain a frequency-versus-wavenumber mapping of the energy density along the wave-vector direction of interest. In this work, the SED approach used requires knowledge of only the crystal unit-cell structure and does not require any prior knowledge of the phonon mode eigenvectors. The SED expression is given by refs. 30,72

where \({\dot{u}}_{\alpha }\) is the α-component of the velocity of the bth atom in the lth unit cell at time t, μ0 = mb/(4πτ0N), τ0 is the total simulation time, and r0 is the equilibrium position vector of the lth unit cell. Our MD model is based on a cubic NbN unit cell with a side length of a = 4.482262 Å. There are n = 8 atoms per unit cell and a supercell comprising of N = Nx × Ny × Nz = 30 × 30 × 30 unit cells forming the total simulated computational domain. This corresponds to a wave-vector resolution of Δκ = 0.033 (2π/a) along each principal direction in the wavenumber space. We note that in Eq. (1), the phonon frequencies can be obtained only for the set of allowed wave vectors as determined by the crystal structure. The MD simulations are performed using the LAMMPS software39. The system is first equilibrated under the NPT ensemble at 16 K for 0.2 ns. After equilibration, the ensemble is switched to NVE, and the system is simulated for 220 time steps with a time interval of Δt = 0.5 fs. Eq. (1) is evaluated using the velocity trajectories extracted every 25 steps.

Isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg calculations

Isotropic superconducting properties were determined using IsoME45. A value of μ = 0.21 was applied, obtained via the GW approximation within SternheimerGW44. The Matsubara frequency cutoff, omega_c, was set to 7,000 meV. In variable DOS computations, the chemical potential was updated continuously. An energy cutoff (encut) of 5,000 meV was applied to all quantities, except for the energy shift and μ update calculations, where a lower cutoff (shiftcut) of 2,000 meV was used.

Anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg calculations

Anisotropic ME calculations were carried out using the EPW code46,73. The construction of maximally localized Wannier functions was initialized via the SCDM algorithm. Electron-phonon matrix elements were computed on a coarse Brillouin zone mesh of 8 × 8 × 8 k-points and 4 × 4 × 4 q-points, and subsequently interpolated onto a dense grid of 24 × 24 × 24 k-points and 12 × 12 × 12 q-points for accurate evaluation of the momentum-resolved superconducting properties.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article or its Supplementary Information. All further information is available from the corresponding author (Christoph Heil, christoph.heil@tugraz.at) upon request.

References

Chen, X.-J. et al. Electronic stiffness of a superconducting niobium nitride single crystal under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 72, 094514 (2005).

Chen, X.-J. et al. Hard superconducting nitrides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 3198–3201 (2005).

Soignard, E., Shebanova, O. & McMillan, P. F. Compressibility measurements and phonon spectra of hexagonal transition-metal nitrides at high pressure: \(\epsilon -{{\rm{TaN}}}\), δ − MoN, and Cr2N. Phys. Rev. B 75, 014104 (2007).

Williams, M., Ralls, K. & Pickus, M. Superconductivity of cubic niobium carbo-nitrides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 28, 333–341 (1967).

Kasumov, A. Y. et al. Supercurrents through single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science 284, 1508–1511 (1999).

Zou, Y. et al. Hexagonal-structured ϵ-NbN: ultra-incompressibility, high shear rigidity and a possible hard superconducting material. Sci. Rep. 5, 10811 (2015).

Oya, G. & Onodera, Y. Transition temperatures and crystal structures of single-crystal and polycrystalline NbNx films. J. Appl. Phys. 45, 1389–1397 (1974).

Aschermann, G., Friederich, E., Justi, E. & Kramer, J. SupraleitfÃhige Verbindungen mit extrem hohen Sprungtemperaturen (NbH und NbN). Physikalische Z. 42, 349–360 (1941).

Keskar, K. S., Yamashita, T. & Onodera, Y. Superconducting transition temperatures of r. f. sputtered NbN films. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 10, 370 (1971).

Shen, K. M. & Davis, J. S. Cuprate high-tc superconductors. Mater. today 11, 14–21 (2008).

Kresin, V. Z. & Wolf, S. A. Fundamentals of Superconductivity (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Hosono, H. & Kuroki, K. Iron-based superconductors: current status of materials and pairing mechanism. Phys. C: Supercond. Appl. 514, 399–422 (2015).

Boeri, L. et al. The 2021 room-temperature superconductivity roadmap. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 183002 (2022).

Wang, B. Y., Lee, K. & Goodge, B. H. Experimental progress in superconducting nickelates. Ann. Rev. Condensed Matter Phys. 15, 305–324 (2024).

Cucciniello, N. et al. Superconducting niobium nitride: a perspective from processing, microstructure, and superconducting property for single photon detectors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 374003 (2022).

Benvenuti, C., Chiggiato, P., Parrini, L. & Russo, R. Reactive diffusion produced niobium nitride films for superconducting cavity applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 336, 16–22 (1993).

Lindgren, M. et al. Picosecond response of a superconducting hot-electron NbN photodetector. Appl. Supercond. 6, 423–428 (1998).

Setzu, R., Baggetta, E. & Villégier, J. C. Study of NbN Josephson junctions with a tantalum nitride barrier tuned to the metal-insulator transition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 97, 012077 (2008).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Superconducting qubits consisting of epitaxially grown NbN/aln/NbN Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 212502 (2011).

Marsili, F. et al. Efficient single photon detection from 500 nm to 5 μm wavelength. Nano Lett. 12, 4799–4804 (2012).

Simon, A. et al. Ab initio modeling of single-photon detection in superconducting nanowires. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.13791 (2025).

Zunger, A., Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. G., Bernard, J. E. & Zunger, A. Electronic properties of random alloys: Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. B 42, 9622–9649 (1990).

Ferreira, P. et al. Ab initio modeling of superconducting alloys. Mater. Today Phys. 48, 101547 (2024).

Marksteiner, P., Weinberger, P., Neckel, A., Zeller, R. & Dederichs, P. H. Electronic structure of substoichiometric carbides and nitrides of zirconium and niobium. Phys. Rev. B 33, 6709–6717 (1986).

Ivashchenko, V. I., Turchi, P. E. A. & Olifan, E. I. Phase stability and mechanical properties of niobium nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 82, 054109 (2010).

Babu, K. R. & Guo, G.-Y. Electron-phonon coupling, superconductivity, and nontrivial band topology in NbN polytypes. Phys. Rev. B 99, 104508 (2019).

Werthamer, N. R. Self-consistent phonon formulation of anharmonic lattice dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 1, 572–581 (1970).

Monacelli, L. et al. The stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: calculating vibrational properties of materials with full quantum and anharmonic effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 363001 (2021).

Larkin, J., Turney, J., Massicotte, A., Amon, C. & McGaughey, A. Comparison and evaluation of spectral energy methods for predicting phonon properties. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 11, 249–256 (2014).

Honarvar, H. & Hussein, M. I. Spectral energy analysis of locally resonant nanophononic metamaterials by molecular simulations. Phys. Rev. B 93, 081412 (2016).

Pickard, C. J. & Needs, R. J. High-pressure phases of silane. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 045504 (2006).

Pickard, C. J. & Needs, R. J. Ab initio random structure searching. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 053201 (2011).

Giustino, F. Materials Modelling Using Density Functional Theory: Properties and Predictions (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interactions from first principles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015003 (2017).

Christensen, A., Dietrich, O., Kress, W., Teuchert, W. & Currat, R. Phonon anomalies in transition metal nitrides: δ-NbN. Solid State Commun. 31, 795–799 (1979).

Lucrezi, R. et al. Quantum lattice dynamics and their importance in ternary superhydride clathrates. Commun. Phys. 6, 298 (2023).

Pickard, C. J. Ephemeral data derived potentials for random structure search. Phys. Rev. B 106, 014102 (2022).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Marx, D. & Parrinello, M. Ab initio path integral molecular dynamics: Basic ideas. J. Chem. Phys. 104, 4077–4082 (1996).

Markland, T. E. & Ceriotti, M. Nuclear quantum effects enter the mainstream. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 0109 (2018).

Hirshberg, B., Rizzi, V. & Parrinello, M. Path integral molecular dynamics for bosons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 21445–21449 (2019).

Plé, T. et al. Routine molecular dynamics simulations including nuclear quantum effects: From force fields to machine learning potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 1432–1445 (2023).

Lambert, H. & Giustino, F. Ab initio Sternheimer-GW method for quasiparticle calculations using plane waves. Phys. Rev. B 88, 075117 (2013).

Kogler, E. et al. IsoME: Streamlining high-precision Eliashberg calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 315, 109720 (2025).

Lucrezi, R. et al. Full-bandwidth anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg theory and its application to superhydrides. Commun. Phys. 7, 1–13 (2024).

Christensen, A. N. et al. Preparation and structure of stoichiometric delta-NbN. Acta Chem. Scandinavica 31a, 77–78 (1977).

Miura, A. et al. Bonding preference of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in niobium-based rock-salt structures. Inorg. Chem. 52, 9699–9701 (2013).

Treece, R. E. et al. New phase of superconducting NbN stabilized by heteroepitaxial film growth. Phys. Rev. B 51, 9356–9359 (1995).

Heger, G. & Baumgartner, O. Crystal structure and lattice distortion of I3-NbNx and Í-NbNx. J. Phys. C 13, 5833–5841 (1980).

Yen, C. M., Toth, L. E., Shy, Y. M., Anderson, D. E. & Rosner, L. G. Superconducting hc-jc and tc measurements in the nb-ti-n, nb-hf-n, and nb-v-n ternary systems. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 2268–2271 (1967).

Duwez, P. & Odell, F. Phase relationships in the binary systems of nitrides and carbides of zirconium, columbium, titanium, and vanadium. J. Electrochem. Soc. 97, 299 (1950).

Brauer, G. & Esselborn, R. Nitridphasen des Niobs. Z. f.ü anorganische und Allg. Chem. 309, 151–170 (1961).

Brauer, G. & Kiliani, W. Darstellung und kristallstruktur von niob-tantal-nitridphasen (nb, ta)n-approximately-1. Z. f.ü anorganische und Allg. Chem. 452, 17–26 (1979).

Christensen, A. N., Josephsen, J., Schäffer, C. E., Watson, K. J. & Sandström, M. Preparation and crystal structure of beta-nb2n and gamma-NbN. Acta Chem. Scandinavica 30a, 219–224 (1976).

Christensen, A. N. et al. Preparation, composition and solid state investigations of TiN, ZrN, NbN and compounds from the pseudobinary systems NbN-nbc, NbN-tic and NbN-tin. Acta Chem. Scandinavica 31a, 861–868 (1977).

Christensen, A. N., Hazell, R. G., Lehmann, M. S., Wright, D. & Selte, K. An x-ray and neutron diffraction investigation of the crystal structure of gamma-NbN. Acta Chem. Scandinavica 35a, 111–115 (1981).

Brauer, G. & Jander, J. Die Nitride des Niobs. Z. f.ü Anorganische und Allg. Chem. 270, 160–178 (1952).

Pessall, N., Gold, R. & Johansen, H. A study of superconductivity in interstitial compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 29, 19–38 (1968).

Lengauer, W. & Ettmayer, P. Preparation and properties of compact cubic δ-NbN1-x. Monatshefte fuer Chem./Chem. Monthly 117, 275–286 (1986).

Terao, N. Structure des nitrures de niobium. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 4, 353 (1965).

Christensen, A. & Rusche, C. Crystal growth of niobium nitride and niobium carbide nitride. J. Cryst. Growth 44, 383–386 (1978).

Tan, J. et al. Stoichiometric δ-NbN: The most incompressible cubic transition metal mononitride. Phys. Status Solidi 254, 1700063 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum espresso: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (19pp) (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum Espresso. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum espresso toward the exascale. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 154105 (2020).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Hamann, D. R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. f.ür. Krist. Cryst. Mater. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Novikov, I. S., Gubaev, K., Podryabinkin, E. V. & Shapeev, A. V. The mlip package: moment tensor potentials with MPI and active learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2, 025002 (2020).

Lucrezi, R., Ferreira, P. P., Aichhorn, M. & Heil, C. Temperature and quantum anharmonic lattice effects on stability and superconductivity in lutetium trihydride. Nat. Commun. 15, 441 (2024).

Thomas, J. A., Turney, J. E., Iutzi, R. M., Amon, C. H. & McGaughey, A. J. Predicting phonon dispersion relations and lifetimes from the spectral energy density. Phys. Rev. B 81, 081411 (2010).

Lee, H. et al. Electron-phonon physics from first principles using the EPW code. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 1–26 (2023).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Kraus, W. & Nolze, G. Powdercell 2.0 for Windows. Powder Diffr. 13, 256–259 (1998).

Kawamura, M. Fermisurfer: Fermi-surface viewer providing multiple representation schemes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 239, 197–203 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Stuart A. Wolf for many interesting and insightful discussions on superconducting alloys and NbN in particular. This work was funded in part by the Defense Sciences Office (DSO) of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and Intellectual Ventures Property Holdings. Computations were performed on the lCluster at TU Graz, the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC5), and the Ohio Supercomputing Center (OSC). R.L. acknowledges the Carl Tryggers Stiftelse för Vetenskaplig Forskning (CTS 23: 2934). This work was supported by TU Graz Open Access Publishing Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.K., F.J., R.L., and C.H. performed the MTP and SSCHA calculations. E.K., R.L., and M.R.S. conducted DF(P)T computations. C.N.T. performed the MD simulations and SED calculations. P.I.C.C. and C.J.P. performed the AIRSS calculations. E.K. and C.H. calculated superconducting properties. B.K. and R.R. carried out a literature search and contributed to interpreting the results. M.N.J., R.P.P., M.I.H. and C.H. supervised the project. All authors contributed to discussions and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Yuhao Fu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kogler, E., Sahoo, M.R., Tsai, CN. et al. Vacancy-free cubic superconducting NbN enabled by quantum anharmonicity. Commun Mater 6, 283 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01004-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01004-w