Abstract

The discovery of superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelates (IL, ABO2) has opened new avenues for understanding high-temperature superconductivity. However, progress in this field is hindered by significant synthesis challenges and the scarcity of research groups capable of producing superconducting samples. Here, we demonstrate a simple route for the topotactic reduction of nickelates using an aluminum overlayer deposited by sputtering on the precursor material (ABO3), enabling the fabrication of high-quality superconducting Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films. By systematically optimizing the aluminum deposition parameters, we achieved superconducting samples via in situ or ex situ (after air exposure of the precursor ABO3 films) reduction. A comparative study of their structural and transport properties shows that in situ Al reduction improves film quality, yielding a maximum superconducting onset transition temperature of 17 K, consistent with the optimal value for this compound. This sputtering-based synthesis route, significantly more accessible than existing methods, offers enhanced control and reproducibility over the reduction process, lowering barriers to the exploration of nickelate superconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of high temperature superconductivity in cuprates in 19861 spurred the quest for analog systems that could shed light on the mechanism underlying unconventional superconductivity. Researchers then identified nickelates as a potential cuprates analogs mainly due to the isoelectronic properties of Ni1+ ion and Cu2+, both with 3d 9 electron count2,3. After three decades of intense research, it was in 2019 when superconductivity was found in infinite-layer (IL) hole-doped Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 nickelate thin films4 grown on SrTiO3 (STO) substrates. Since then, the family of superconducting (SC) IL nickelates has significantly expanded in the thin film form including Sr:PrNiO25,6,7, Ca:LaNiO28, Sr:LaNiO29,10 and Eu:NdNiO211 compounds. Very recently, superconductivity has also been observed in undoped NdNiO212 and PrNiO213 films but remains absent in bulk nickelates14,15, leading to early speculation about a possible interfacial character. This hypothesis now seems to be discarded after recent observations of superconductivity in nickelate thin films grown on an alternative substrate (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7(LSAT)16,17 as well as different interface terminations for SC IL films on STO substrates18,19,20.

Nickelates now constitute an entire new realm of research, with a number of outstanding questions needing to be addressed to clarify whether nickelates are true analogs of cuprates or a distinct family of unconventional superconductors21,22,23,24,25. However, the synthesis of these compounds faces significant challenges that currently impede further progress of this nascent field.

One of the main difficulties lies in the intricate topotactic reduction process used to selectively remove only the oxygens at the apical sites of the initial parent perovskite phase and end up with the SC IL phase. It requires pushing Ni to the thermodynamically unstable valence state Ni1+ to reach the desired 3d 9 configuration, whereas the most common stable oxidation state is Ni2+ 26. In addition, the conventional reduction method employing CaH2 as the reducing agent presents reproducibility problems between different research groups23,27,28. The superconducting samples obtained by this method also lack of crystallinity at the top surface and seem vulnerable to re-oxidation upon exposure to air for a prolonged time4,5,6,8,9,16,29,30. To address this issue, a protective STO capping layer is usually added31, which is hindering the study of the electronic structure or superconducting gap by using surface-sensitive techniques, such as angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). It is therefore crucial for the advancement of the field to develop reliable alternative reduction methods that could overcome these obstacles and provide high-quality superconducting nickelate samples.

Recently, an alternative reduction approach was demonstrated by Wei et al.11,32 In this method, the perovskite parent phase is reduced in situ by depositing an aluminum (Al) overlayer using molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Last year, two independent groups also reported the use of in situ atomic hydrogen bombardment to successfully reduce the perovskite phase into the SC infinite-layer phase33,34,35. This technique enabled the first experimental visualization of the electronic band structure of nickelates in (Sr,Ca):LaNiO236,37. However, these techniques are limited in their accessibility for many research groups, underscoring the need to find simpler ex situ or in situ methods to reduce the nickelates.

In this work, we demonstrate an effective and simpler alternative route to synthesize high quality superconducting IL Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 (PSNO2) thin films. We use a more accessible technique such as direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering to deposit a thin aluminum metal layer on top of the perovskite parent Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO3 (PSNO3) thin films. The Al overlayer selectively pumps the apical oxygen atoms from the perovskite films through an efficient redox reaction, achieving the complete transformation of the nickelates thin films into the SC IL phase. This approach is somewhat reminiscent of that used to generate two-dimensional electron gases (2DEGs) in SrTiO338,39 and KTaO340,41, but here with a stronger reduction efficiency under optimized conditions.

We describe the whole optimization process of the Al sputtering deposition conditions as well as the comparison between SC samples reduced by Al deposition either in situ or ex situ (i.e., after having exposed the precursor film to the air). By using this method, we obtain high quality SC infinite-layer PSNO2 thin films with a maximum superconductivity transition \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) of 17 K when the whole process is carried out in situ. This new approach allows better control over the chemical transformation and improve sample reproducibility and quality. It also enables in situ reduction while preserving surface cleanliness. Combined with the top-down nature of the process, this approach could, in principle, allow the use of surface-sensitive techniques provided that the Al capping layer is sufficiently thin40,42 or removed prior to measurement. This new, much more accessible method, enriches the catalog of synthetic recipes available to date for obtaining infinite-layer nickelates, and is expected to stimulate more research groups to synthesize these compounds, which could contribute to the physical understanding of the superconductivity in IL nickelates.

Results and discussion

Precursor Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO3 perovskite thin films were grown by Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD) on (001)-oriented STO substrates following previously optimized conditions described in the experimental section43. Supplementary Figs. S1–S3 of Suplementary information show a summary of the structural characterization of the as-grown perovskite thin films. In situ Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED) monitoring of the growth indicates a layer-by-layer growth of the films and a flat surface exhibiting step terraces structure. The films also exhibit clear pseudocubic perovskite 00l peaks, with no additional features, indicating a high crystalline quality and single-phase perovskite PSNO3 films. The out-of-plane lattice constant (c) is ≈ 3.76 Å, consistent with previous reports on this compound5,6,43. In addition, Reciprocal Space Map (RSM) collected around the asymmetric (\(\overline{1}\)03) peak of SrTiO3 confirms that the films are coherently strained to the substrate, which imposes 2.23% tensile strain. The subsequent reduction of the precursor perovskite films is achieved by depositing an Al layer using DC magnetron sputtering technique. The Al deposition is carried out at specified temperature and is followed by a post-deposition annealing at the same temperature. The schematic of the process is shown in Fig. 1a. During the reduction, Al removes oxygen from the parent perovskite nickelate film through a redox reaction and becomes oxidized, following the chemical reaction:

a Schematic diagram of the Al reduction process in nickelates. First, an aluminum overlayer is sputtered onto the precursor PSNO3 perovskite thin film at moderate temperatures (280−380∘C). This is followed by a post-deposition annealing at the same temperature for a specified time (60−180 min). Al deposition temperature and post-annealing time are selected depending on the thickness of the precursor perovskite film. b X-Ray Diffraction θ - 2θ symmetric scans of a 8 nm thick parent PSNO3 thin film reduced under different Al deposition temperatures ranging from 350−390∘C. The post-annealing time was fixed to 120 min in all the cases. c Resistivity as a function of temperature (ρ (T)) for the samples showed in panel (b). The inset shows the same data for temperatures below 20 K. d ρ (T) as a function of the post-annealing time for a representative series of 8 nm-thick films when Al is deposited at 380∘C. The inset shows the same data near the superconducting transition. e Evolution of the Al deposition temperature (gray circles) and post-annealing time (purple circles) as a function of the perovskite PSNO3 film thickness. The Al thickness was set at 3.5 nm. f Evolution of the c-axis lattice parameter (Å) of the thin film as a function of the aluminum deposition rate in Å/s. The deposition rate optimization was performed on a 6 nm-thick sample (10 × 10 mm2, later cut in four pieces for the experiments), using 2.5 nm Al thickness, at a fixed reduction temperature of 290∘C and a post-annealing time of 60 min.

Aluminum reduction optimization

Firstly, we focused on systematically optimizing the deposition conditions of the Al layer. In the case of DC magnetron sputtering deposition, several parameters may play a crucial role in the success of the parent phase reduction. Notably, the reduction temperature, defined as the temperature at which we deposit the aluminum layer, the deposition rate and the post-annealing time. All these parameters have been tuned to optimally reduce the parent PSNO3 film and achieve the complete transformation into the infinite-layer phase. It is also worth mentioning that we have empirically verified a negligible effect of the pre-annealing time before the Al deposition in the synthesis of the IL films.

During the optimization of the parameters mentioned above, the Al deposition was consistently performed ex situ. Thus, prior to any Al deposition, all the perovskite thin films were grown on 10 × 10 mm2 STO substrates and removed from the PLD chamber to verify their crystalline quality and transport properties. Subsequently, each film was cut into four pieces of 5 × 5 mm2 to test various Al deposition conditions. Technical details regarding the Al sputtering deposition are provided in the experimental section of this paper.

We initially optimized the Al deposition temperature (hereafter, reduction temperature) for an 8 nm-thick perovskite film. The aluminum thickness used for these initial experiments was ≈ 3.5 nm, following the findings of previous work on Al reduction by MBE32. It should be noted that the fully reduction of the films should cause a contraction of the c-axis parameter, which decreases to a nominal value of ~ 3.3 Å in Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films5,6,43, leading to a reduction in film thickness.

The optimal reduction temperature was determined by combining X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transport measurements to assess the crystalline quality and the presence or absence of a superconducting transition in the thin films. Figure 1b, c depict the diffractograms and the temperature-dependent resistivity curves of a series of 8 nm-thick perovskite films subjected to Al deposition at various temperatures. When the Al deposition is performed at 350∘C, the film partially transforms into the IL phase. Although it shows good crystalline quality, as indicated by intense (001) and (002) PSNO2 film peaks and a 2θ value of 54.8∘ (c ≈ 3.34 Å), it does not undergo a superconducting transition and instead exhibits insulating nature at low temperatures. Notably, this out-of-plane lattice parameter (c) is consistent with values reported in the literature for the stabilized SC IL PSNO2 phase5,6,43.

As reduction temperature increases to 360∘C, 370∘C and 380∘C, a complete transformation into the IL phase occurs. This is evidenced not only by minimal changes in the film’s crystalline quality (2θ = 55∘, c ≈ 3.33 Å), but, more significantly, by the observation of a superconducting transition, reaching a zero-resistance state for both temperatures. However, the resistivity of the film reduced at 370∘C exhibits a pronounced upturn at low temperatures and overall higher resistivity values, suggesting the presence of defects16. At deposition temperatures above 380∘C, the film clearly reduces beyond the optimal level, resulting in a loss of crystallinity or even decomposition, as indicated by the significant reduction in the intensity of both (001) and (002) PSNO2 film peaks27. In this over-reduced sample, insulating behavior is clearly observed at low temperatures. These results highlight the importance of complementing XRD with transport measurements to unambiguously confirm the stabilization of the superconducting phase in nickelates. Accordingly, for the 8 nm-thick film a well-defined reduction window is identified between 360∘C and 380∘C, with 380∘C yielding the highest critical temperature (≈ 9 K) and the lowest resistivity within this range.

Once Al reduction temperature was set at 380∘C for a film of 8 nm thickness, we explored the effect of the post-annealing time, defined as the period during which the sample is maintained at the deposition temperature after the completion of Al deposition. This post-annealing time controls oxygen diffusion from the film’s bottom layer, adjacent to the substrate interface, up to the top surface, where it oxidizes the aluminum layer. As demonstrated by STEM analysis conducted by Wei et al.32, the topotactic reduction driven by aluminum deposition proceeds in a top-down manner, which makes optimization of the post annealing time essential. In Fig. 1d, we present temperature-dependent resistivity measurements for a series of 8 nm-thick samples prepared with different post-annealing time, while all other parameters were kept constant. For short post-annealing times ranging from 30−90 min, the films are not fully reduced showing partial superconducting transitions without reaching zero resistance state. In contrast, for an optimal post-annealing time of 120 min, a complete superconducting transition and zero resistance state are observed. The onset transition temperature (\({T}_{c}^{onset}\)), defined from now on as the intersection of linear extrapolations from the normal state and the superconducting transition regions, is \({T}_{c}^{onset}=10\) K. Exceeding this optimal time deteriorates the superconducting properties of the film, with a significant decrease of the \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) (at 150 min), or even results in an over-reduced film (at 180 min). The latter causes a marked upturn starting at 50 K, followed by a partial superconducting transition at lower temperature, but without reaching zero resistance. In addition to the substantial resistivity changes depending on the post-annealing time, XRD measurements show a notable improvement in film crystallinity as the post-annealing time increases from 10−60 min (see Supplementary Fig. S4 of Supplementary information). For longer post-annealing times, the improvement in XRD data is minimal and the c-axis lattice parameter of the thin film varies little between 120−180 min. Therefore, superconducting IL samples can be achieved within a relatively narrow post-annealing time window of around 120 min for the 8 nm-thick film presented here. This result confirms the fundamental role of the post-annealing time in achieving a complete reduction of the entire thickness of the perovskite film.

We carried out similar optimization of reduction temperature and post-annealing time for different perovskite film thickness between 6 and 11 nm, as shown in Fig. 1e. We could not investigate films thicker than 11 nm due to the reported poorer quality of the parent perovskite films, characterized by the appearance of secondary phases4. At first glance, one notices that the two parameters are closely correlated: as film thickness increases, it is necessary to simultaneously raise both the deposition temperature and the post-annealing time to achieve complete reduction of the nickelate thin films. However, their dependence on the perovskite film thickness differs. While the post-annealing time exhibits clear linearity, the reduction temperature increases rapidly for low thicknesses (6−8 nm) and then remains constant for thicknesses between 9−11 nm.

So far we have used 3.5 nm Al thickness to reduce the samples, but it is also important to determine the appropriate Al thickness needed to completely reduce the perovskite PSNO3 into the IL PSNO2 phase, while avoiding any potential contribution from an Al metal overlayer in the transport measurements. In addition, the aluminum oxide overlayer formed during reduction efficiently protects the nickelate from re-oxidation, acting as both a reducing agent and a protective layer. Thus, we fine-tuned the Al thickness to ensure the complete oxidation of the overlayer into Al2O3. For this purpose, we in situ monitored the evolution of the X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the core level spectra of Al 2p, corresponding to the metallic Al (Al 0) and oxidized Al (Al3+) (see Supplementary Fig. S5 of Supplementary information), after each Al deposition process was completed. The Al layer thickness was then reduced until no trace of Al metal is observed. Following this optimization, the Al thickness was reduced to 2.5–2.8 nm for the subsequent experiments.

We finally focused on determining the optimal aluminum deposition rate varying it from 0.363 Å/s −2.357 Å/s. To identify the optimal growth rate, we performed complementary XRD measurements to monitor the evolution of the c-axis lattice parameter as a function of the deposition rate. As shown in Fig. 1f, the trend is clear: the lowest deposition rate enhances the reduction process, resulting in the smallest c-axis lattice parameter, ~3.37 Å in this case. Therefore, we fixed the aluminum deposition at 0.363 Å/s (or ≈ 22 Å/min) for subsequent experiments. Notably, this deposition rate is significantly higher than that typically used for Al deposition by other techniques such as MBE ( ≈ 0.5 layer/min ≈ 0.54 Å/min)32.

The optimization of sputter deposition parameters presented here provides a concrete recipe tailored to film thickness, but more importantly, it identifies general trends that govern the Al-assisted reduction process. While the specific recipe may differ across material systems/equipment, these trends offer broadly applicable guidelines for optimizing topotactic reduction in IL nickelates and, more generally, in oxide systems undergoing phase transitions.

Differences between ex situ and in situ Al reduction

After optimizing the parameters for Al reduction, we analyzed the main differences observed in samples reduced via ex situ and in situ processes. In situ experiments were performed on PSNO3 thin films grown on 5 × 5 mm2 (001) SrTiO3 substrates, which were directly transferred to the sputtering chamber for Al deposition in ultra-high vacuum without any exposure to air.

Firstly, as illustrated by the XRD measurements of Fig. 2a, minimal changes are observed in the crystallinity of the samples reduced by both methods. In situ reduced film seems to exhibit a slightly higher crystalline quality, evidenced by the tiny Laue oscillations around the (002) peak of the film (indicated by arrows in the figure). Further, the (002) peak of the in situ reduced film is shifted towards higher angles, indicating a minor decrease in its out-of-plane lattice parameter (c ≈ 3.33 Å). Both films remain fully strained to the SrTiO3 substrate after the aluminum deposition, despite the change from tensile ( ≈ 2.23%) to compressive strain ( ≈ -1.2%) when they transfom into the IL PSNO2 phase (see Supplementary Fig. S6a, b) in Supplementary information). The surface topography of both films is well-preserved and remains smooth after the Al reduction, indicating that the Al2O3 overlayer is uniform (see Supplementary Fig. S6c, d) in Supplementary Information). Additionally, the surface of in situ sample shows superior quality, featuring step terrraces with an average step height of ≈0.595 nm (one and a half times the thickness of an STO unit cell). Despite the flat surface, steps are not visible in the ex situ reduced sample.

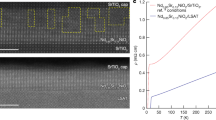

a X-Ray Diffraction θ - 2θ scans of Al reduced Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 samples, one exposed to air before aluminum deposition (ex situ, red), and another reduced without air exposure (in situ, blue). b Resistivity comparison as a function of the temperature for infinite-layer phase after ex situ aluminum reduction (red line), showing \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) = 10 K and \({T}_{c}^{zero}\) = 4 K, and after in situ aluminum reduction, showing \({T}_{c}^{onset}\)= 17 K and \({T}_{c}^{zero}\) = 14.5 K. c Enlarged view of the ρ versus T curves from panel b) in the temperature range of 2 to 25 K (around the superconducting transition). \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) is defined as the intersection of the linear extrapolations of the normal state and the superconducting transition regions. d, e Temperature-dependent resistivity of several IL superconducting samples reduced via ex situ (d) and in situ (e) Al sputtering deposition around the superconducting transition region. f Comparison of critical temperature onset (\({T}_{c}^{onset}\)) as a function of the resistivity (ρ) at 20 K for in situ (blue circles) and ex situ (red circles) samples (shown in (d, e)) with previous reports of superconducting (La, Pr or Nd)1-xSrxNiO2 thin films reduced using the conventional CaH2 method. Blue shaded area is a guide to the eye indicating the most common values for in situ reduced samples.

However, an improvement of in situ Al reduced samples compared to ex situ ones is more evident in the transport properties, as can be seen in Fig. 2b. Although both in situ and ex situ samples reach a zero-resistance state, a substantial decrease in overall resistivity as well as an enhancement of \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) can be observed in the in situ reduced film (see Fig. 2c). The absolute value of resistivity for the in situ reduced sample is ρ (20K) ≈ 0.45 mΩ.cm, which matches the reported values for SC PSNO2 films on STO substrate5,6 and represents half of the value obtained from the ex situ reduced sample ( ≈ 1 mΩ.cm). Remarkably, the resistivity of the in situ reduced film clearly exhibits a T-linear behavior with only a mild upturn in resistivity just before the SC onset, whereas the ex situ film does not show a T-linear behavior and is followed by a marked resistivity upturn at low temperatures (see linear fittings on Supplementary Fig. S7 of Supplementary information). Consistent with previous reports16, this observation suggests a notable decrease in disorder in the in situ reduced films compared to those exposed to the air during the intermediate step between PLD growth and Al sputtering deposition. The slope of the linear fitting for in situ reduced film is roughly 40 × 10−4 mΩ.cm.K−1 (with variations among samples), comparable to the values found in other SC IL nickelates grown on STO, such as (Nd,Sr)NiO216. Optimally doped NdSrNiO2 films grown on LSAT substrate have reported slopes of roughly 11 × 10−4 mΩ. cm. K−116, attributed to improved crystallinity and reduced disorder of the films owning to a favorable epitaxial mismatch for the perovskite and the infinite-layer phases on LSAT substrate compared to STO. Other families of unconventional superconductors, such as cuprates44,45, also exhibit a linear dependence of resistivity, although its origin is not clearly understood46. Furthermore, the width of the SC transition (defined as 90%-10% of the normal state at 20 K) also slightly decreases for the in situ reduced samples (ΔTc ≈ 2 − 3K) compared to the ex situ ones (ΔTc ≈ 3 − 4K), indicating an improvement in the homogeneity of the superconductivity in in situ reduced samples.

The observations described above for a representative ex situ and in situ Al reduced sample are generally applicable. In Fig. 2d, e, we present the transport properties of a series of PSNO2 samples synthesized under nominally similar conditions using ex situ and in situ Al reduction, respectively (see curves over a wider range of temperature in Supplementary Fig. S8 of Supplementary information). Figure 2f plots the Tc values as a function of resistivity (ρ) at 20 K for the samples in Fig. 2d, e. The ex situ reduced samples exhibit a wide range in the resistivity values (1–5.8 mΩ.cm), indicating limited control over the disorder in the samples, while the Tc values always remain below 13 K. In contrast, the in situ Al reduced samples display a much more reproducible ρ (20 K) value, consistently falling below 1.3 mΩ.cm. This further supports the idea of an improvement in synthesis regarding disorder for the in situ Al reduced samples. However, much more variability is observed in the Tc values of in situ reduced samples, reaching a maximum Tc of 17 K for the best samples obtained by this method. This variation in transition temperature among samples may stem from differences in the crystallinity of the parent perovskite phase or local fluctuations in oxygen stoichiometry. Recent reports on hydrogen reduction of nickelates prepared in situ reveal similar Tc variability, though the underlying cause remains unclear35. This aspect will be studied in more detail and, if possible, improved in future studies.

The successful use of aluminum sputter deposition to trigger the topotactic transformation of nickelates motivate us to compare our current results with previous reports on (La, Pr or Nd)1-xSrxNiO2 thin films reduced using the conventional CaH2 method (Fig. 2f). Our results are fully comparable to the current state of the art for all those compounds and to the best results reported in the literature for PSNO2 compound7, particularly when Al is deposited in situ. This positions Al sputter reduction as a simple and accessible alternative method, potentially allowing a broader range of research groups to synthesize high-quality SC IL nickelate thin films.

Furthermore, magnetotransport measurements were performed under out-of-plane magnetic fields up to 9 T for an ex situ (Fig. 3a) and an in situ (Fig. 3b) reduced samples. The behavior is similar for both samples, the SC transition gradually shifts to lower temperatures, and the transition width broadens with increasing magnetic field. However, the superconductivity transition still remains at the highest magnetic field we can apply (9 T), in line with same type of measurements in other SC IL nickelates systems, such as Nd1-xSrxNiO24,47, Nd1-xEuxNiO211 or La1-xSrxNiO29. Additionally, ex situ sample shows a two-step transition probably originated from inhomogeneities in the sample.

a, b Temperature-dependent resistivity measurements around the \({T}_{c}^{onset}\) for different externally applied out-of-plane magnetic fields up to 9 T in ex situ (a) and in situ (b) reduced samples. c Normal state Hall coefficient (RH) as a function of temperature for ex situ and in situ Al reduced PSNO2 thin films.

The normal state Hall coefficient RH as a function of the temperature is presented in Fig. 3c, for both samples. As observed in other nickelates compounds, RH remains negative at temperatures above Tc but increases with decreasing temperature, changing sign from negative to positive while traversing the superconducting transition irrespective of whether the sample is reduced in situ or ex situ. This suggests a complex Fermi surface with a mixed carrier contributions from both electrons and holes4,6,16,43,47,48. This change of sign observed in our 20% doped PSNO2 thin films is consistent with what is reported for the same compound when the doping level varies from 12 and 32%6, which are the superconducting compositions for PSNO2 phase.

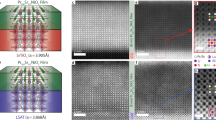

The observed superior quality and lessened disorder in in situ reduced samples, compared to ex situ ones, is likely related to the quality of the top interface region with the Al. Scanning transmission microscopy (STEM) experiments performed on ex situ (Fig. 4 top panels) and in situ (Fig. 4 bottom panels) samples—corresponding to those in Fig.2b, c—provide direct correlation between structure and transport properties. The cross section high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image of an ex situ reduced sample (Fig. 4a) shows the presence of defects and the overall low crystalline quality in the infinite-layer film, particularly near the upper interface with the amorphous AlOx layer. Geometrical phase analysis (GPA) reveals vertical Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) defects and strain inhomogenities in both out-of-plane (Fig. 4c) and in-plane (Fig. 4e) strain maps, primarily arising near the top interface. Furthermore, Fig. 4g depicts an HAADF image (left panel) of the bottom interface and its corresponding 4D-STEM divergence of center of mass (dCOM) analysis (right panel), showing that some apical oxygen remains, although the majority of the sample is clearly in the infinite-layer phase.

a, b Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image of a Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 films reduced via ex situ (a) and in situ Al sputter deposition (b). The thickness of IL films is indicated on the images. The Al thickness used to reduce the films is 2.8 nm in both cases. c−f Geometrical phase analysis of the HAADF images in panel a and b showing the out-of-plane (c, d) and in-plane (e, f) strain relative to the SrTiO3 substrate for ex situ (c, e) and in situ (d, f) Al reduced samples. Ex situ film exhibits strain inhomogenities arising from the top interface with the amorphous AlOx. g, h (left panels) Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM images from the regions near the bottom interface, marked in panel (a, b) (orange rectangles), respectively. (Right panels) Corresponding 4D-STEM dCOM images showing the absence of oxygen atoms at the apical sites (indicated by orange arrows). In both images, green circles represent Pr/Sr atom sites, orange circles represent Ni sites and red circles represent O sites. The analyzed samples are the same as those shown in Fig. 2b, c.

In contrast, similar analysis on an in situ Al reduced sample confirms a clean infinite-layer structure with high structural quality, largely free of RP-type defects throughout the thickness of the thin film. The top interface between the infinite-layer film and the thin amorphous layer of oxidized aluminum is relatively well-defined in the in situ Al-deposited sample (Fig. 4b). GPA analysis applied to that HAADF image also reveals a uniform out-of-plane strain (Fig. 4d) and uniformly in-plane constrained thin-film with STO (Fig. 4f), confirming the minimal presence of defects. The 4D-STEM dCOM analysis confirms the total absence of apical oxygen (indicated by arrows) in the proximity of the bottom interface with the STO substrate. This results in the expected structure of alternating Pr/Sr and NiO2 planes for the IL phase (see Fig. 4 h) and Supplementary Fig. S9 of Supplementary information for quantitative analysis).

In ex situ reduced samples, the surface of the perovskite film is exposed to air prior to Al deposition. XPS measurements (Supplementary Fig. S10 of Supplementary information) revealed a significant amount of adventitious carbon adhered to this surface, which is almost negligible in in situ reduced samples. Given the negligible mobility of Nd and Ni cations at the employed reduction temperature, the RP-type defects observed after ex situ reduction are unlikely to result from cation rearrangement. Instead, they can be attributed to strain inhomogeneities generated by non-uniform oxygen removal across the contaminated surface, which promote vertical faulting during the topotactic transition. In situ reduction avoids these issues by ensuring a pristine surface and more homogeneous oxygen diffusion. Developing a cleaning protocol (e.g., using oxygen or argon plasma) for ex situ reduction could similarly improve film quality and expand the accessibility of this method49. Although beyond the scope of this work, it represents a promising direction for future research to further broaden the reach of this synthesis approach within the oxide community.

There are few additional observations regarding ex situ and in situ reduction worth discussing. First, while both methods yield superconducting IL samples, in situ reduction reliably produces SC films with zero resistance, superior crystallinity, and better transport properties (e.g., T-linear behavior, higher Tc value and sharper transitions). In contrast, ex situ process presents notable sample-to-sample variation, often leading to incomplete superconducting transitions without reaching the zero-resistance state, indicating a less consistent outcome. Second, in situ reduction occurs entirely in vaccum, with no apparent hydrogen source during the process, yet we obtain high-quality superconducting IL samples. This aligns with recent studies indicating that extensive hydrogen incorporation is not a key ingredient in achieving superconductivity in IL nickelates50,51,52. Finally, even in in situ reduced superconducting samples, some inhomogeneity is observed within the 5 × 5 mm2 samples, with slight variations in Tc and resistivity depending on the direction of the transport measurements (see Supplementary Fig. S11 of Supplementary information). Additional measurements suggest that this anisotropy may be correlated with the substrate step-terrace structure, consistent with a previous report53. Such inhomogeneity could be relevant for experiments requiring uniform sample pieces and highlights the need for further optimization to achieve fully homogeneous SC samples.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated a simple and accessible method for synthesizing superconducting infinite-layer nickelate Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films using aluminum sputtering deposition, which can be carried out entirely in situ or ex situ, after air exposure of the perovskite precursor. Systematic optimization of Al sputtering deposition parameters revealed that lower deposition rates enhance the reduction process, while the reduction temperature and post-annealing time must be adjusted based on the thickness of the parent perovskite phase. Detailed characterization of the resulting superconducting samples demonstrates that in situ Al reduction reproducibly yields superconducting infinite-layer Pr0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films with improved crystallinity and superior transport properties, including T-linear resistivity, higher superconducting transition temperatures, and sharper transition compared to ex situ reduction.

Topotactic reduction of nickelates via Al sputtering deposition can be performed fully in situ while preserving an atomically flat surface and follows a top-down process, making it suitable for surface-sensitive characterizations. This method enables the synthesis of samples with quality comparable to those produced by conventional CaH2 reduction, while offering a simpler and more controllable alternative. More importantly, the accessibility of this sputtering-based method could significantly expand the number of independent research groups capable of producing high-quality superconducting infinite-layer nickelates, potentially boosting experimental efforts to unravel their physics. Beyond nickelates, this approach could be extended to other oxide systems, facilitating the synthesis of novel reduced phases with emergent properties.

Methods

SrTiO3 substrates preparation and synthesis of perovskite thin films by PLD

Prior to growth, the (001) SrTiO3 (SurfaceNet) substrates were etched in hydrofluoric acid (HF) solution and annealed at 1000∘C in an oxygen atmosphere for 3 h to obtain TiO2 surface termination. To optimize the conditions for aluminum deposition, PSNO3 thin films with thicknesses ranging from 6−11 nm were grown on 10 × 10 mm2 SrTiO3 (001) substrate by pulsed laser deposition (PLD), which were then cut in four pieces of the same size. For in situ reduction, PSNO3 thin films with a thickness of 8 nm (20−22 unit cells) were grown on 5 × 5 mm2 SrTiO3 (001) substrate.

Perovskite nickelate thin films were grown by PLD using a 248 nm KrF excimer laser. The films were deposited at a substrate temperature of 640∘C and an oxygen partial pressure of 0.33 mbar, using an energy fluence of 1.6 J/cm−2 (laser spot size 1 × 2 mm2). After the growth, the film was cooled down at a rate of 10∘C/min under the growth pressure. The growth of the films was monitored in situ by a reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED). More details on sample preparation and optimization can be found in ref. 43.

Ex situ and in situ Al reduction

When the process was carried out ex situ, the films were removed from vacuum prior to Al deposition. In contrast, in the in situ process, the films were directly transferred from the PLD chamber to the sputtering chamber without exposure to air. The deposition of the aluminum metal layer was carried out inside sputtering chamber (PLASSYS), at a pressure of 6.4 × 10−4 mbar. The argon flow was set to 5.2 sccm, the current to 15 mA, power to 5 W and voltage to 320 V. Before any aluminum metal deposition the target was pre-sputtered for 10 min to remove any potential oxidized layer. The Al deposition to reduce the thin films was performed at sample temperatures ranging from 270−380∘C in continuous mode. A post-annealing step at the deposition temperature was performed after the Al deposition in all the cases, varying the time from 30−180 min. The heating and cooling rates were set to 10∘C/min.

Structural and transport characterization

The structural quality and thickness of the thin films were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray reflectivity by using a X-ray diffractometer Empyrean (Malvern Panalytical). The thickness was determined by fitting the XRR curves using the X’Pert Reflectivity software. The reciprocal space maps were obtained by using a rotating anode high-resolution X-ray diffractometer from Smartlab-Rigaku with a Cu (Kα) = 1.5406 Å for both diffractometers. The surface topography of the samples was acquired with a Bruker Atomic Force Microscope in non-contact mode. Electrical transport measurements were performed using a Dynacool System (Quantum Design), with bondings done using gold or aluminum wires in van der Pauw geometry.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM)

The cross-sectional lamellae for Transmission Electron Microscopy were prepared using a Focused Ion Beam (FIB) technique at Centre de Nanosciences et de Nanotechnologies (C2N), University Paris-Saclay, France. Prior to FIB lamellae preparation, around 20-30 nm of amorphous carbon was deposited on top of the samples for protection. The High-angle annular darkfield (HAADF) imaging and 4D-STEM was carried out in a NION UltraSTEM 200 C3/C5-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope. The experiments were done at 200 keV with a probe current of ≈12 pA and convergence semi-angles of 30 mrad. A MerlinEM (Quantum Detectors Ltd) in a 4 × 1 configuration (1024 x 256) had been installed on a Gatan ENFINA spectrometer mounted on the microscope54. For 4D-STEM, the electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) spectrometer was set into non-energy dispersive trajectories and 6-bit detector mode that gave a diffraction pattern with a good signal to noise ratio without compromising much on the scanning speed was used. The geometrical phase analysis (GPA)55 had been done choosing the STO substrate with 3.91 Å, as a reference parameter. The lattice parameters of the PSNO2 were estimated by averaging the GPA maps over square areas of = 25 (in-plane) × 10 (out-of-plane) nm giving a strain accuracy determination better than 1%, that is, better than 0.04 Å for the lattice parameters. Such an approach has been previously employed to accurately determine the c-axis variation in an apical oxygen ordered nickelate thin-film on an STO substrate30.

Error bars

Error bars for the reduction temperature and post-annealing time were determined by considering the range of annealing conditions over which superconductivity was reproducibly observed. For each thickness, we examined samples reduced at several temperatures and post-annealing times. Superconductivity was consistently obtained over a finite temperature window, with variations in TC across that range. We therefore adopted an uncertainty of ± 10 ∘C and ± 20 min around the optimal reduction temperature and post-annealing time, respectively, as a representative error bar. This criterion was applied to all data points shown in Fig. 1e.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Onnes, H. K. Further experiments with liquid helium. c. on the change of electric resistance of pure metals at very low temperatures etc. The resistance of pure mercury at helium temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 13, 1274–1276 (1911).

Anisimov, V. I., Bukhvalov, D. & Rice, T. M. Electronic structure of possible nickelate analogs to the cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7901 (1999).

Hansmann, P. et al. Turning a nickelate Fermi surface into a cuprate like one through heterostructuring. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 016401 (2009).

Danfeng, L. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624–627 (2019).

Osada, M. et al. A superconducting praseodymium nickelate with infinite layer structure. Nano Lett. 20, 5735–5740 (2020).

Osada, M., Wang, B. Y., Lee, K., Li, D. & Hwang, H. Y. Phase diagram of infinite layer praseodymium nickelate Pr1−xSrxNiO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 121801 (2020).

Wang, N. N. et al. Pressure-induced monotonic enhancement of Tc to over 30 k in superconducting Pr0.82Sr0.18NiO2 thin films. Nat. Commun. 13, 4367 (2022).

Zeng, S. et al. Superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelate La1−xCaxNiO2 thin films. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9927 (2022).

Osada, M. et al. Nickelate superconductivity without rare-earth magnetism: (La, Sr)NiO2. Adv. Mater. 33, e2104083 (2021).

Sun, W. et al. Evidence for anisotropic superconductivity beyond Pauli limit in infinite-layer lanthanum nickelates. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303400 (2023).

Wei, W., Vu, D., Zhang, Z., Walker, F. J. & Ahn, C. H. Superconducting Nd1−xEuxNiO2 thin films using in situ synthesis. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh3327 (2023).

Parzyck, C. et al. Superconductivity in the parent infinite-layer nickelate NdNiO2. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021048 (2025).

Sahib, H. et al. Superconductivity in PrNiO2 infinite-layer nickelates. Adv. Mater. 37, 2416187 (2024).

Puphal, P. et al. Topotactic transformation of single crystals: From perovskite to infinite-layer nickelates. Sci. Adv. 7, eabl8091 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Absence of superconductivity in bulk Nd1−xSrxNiO2. Commun. Mater. 1, 16 (2020).

Lee, K. et al. Linear-in-temperature resistivity for optimally superconducting (Nd, Sr)NiO2. Nature 619, 288–292 (2023).

Ren, X. et al. Possible strain-induced enhancement of the superconducting onset transition temperature in infinite-layer nickelates. Commun. Phys. 6, 341 (2023).

Goodge, B. H. et al. Resolving the polar interface of infinite-layer nickelate thin films. Nature Materials 22, 466–473 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Thickness-dependent interface polarity in infinite-layer nickelate superlattices. Nano Letters 23, 3291–3297 (2023).

Raji, A. et al. Unraveling p-type and n-type interfaces in superconducting infinite-layer nickelate thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2409930 (2024).

Lechermann, F. Late transition metal oxides with infinite-layer structure: Nickelates versus cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 101, 081110 (2020).

Botana, A. S., Bernardini, F. & Cano, A. Nickelate superconductors: An ongoing dialog between theory and experiments. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 132, 618–627 (2021).

Chow, L. & Ariando, A. Infinite-layer nickelate superconductors: a current experimental perspective of the crystal and electronic structures. Front. Phys. 10, 834658 (2022).

Carrasco Álvarez, A. A. et al. Charge ordering as the driving mechanism for superconductivity in rare-earth nickel oxides. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 064801 (2024).

Kitatani, M., Nomura, Y., Hirayama, M. & Arita, R. Ab initio materials design of superconductivity in d9 nickelates. APL Mater. 11, 030701 (2023).

Anisimov, V., Bukhvalov, D. & Rice, T. Electronic structure of possible nickelate analogs to the cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7901 (1999).

Kyuho, L. et al. Aspects of the synthesis of thin film superconducting infinite-layer nickelates. APL Mater. 8, 041107 (2020).

Wang, B. Y., Lee, K. & Goodge, B. H. Experimental progress in superconducting nickelates. Annu. Rev. Condensed Matter Phys. 15, 305−324 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Impact of cation stoichiometry on the crystalline structure and superconductivity in nickelates. Front. Phys. 9, 719534 (2021).

Raji, A. et al. Charge distribution across capped and uncapped infinite-layer neodymium nickelate thin films. Small 19, 2304872 (2023).

Krieger, G. et al. Synthesis of infinite-layer nickelates and influence of the capping-layer on magnetotransport. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 56, 024003 (2023).

Wei, W. et al. Solid state reduction of nickelate thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 013802 (2023).

Parzyck, C. T. et al. Absence of 3a0 charge density wave order in the infinite-layer nickelate NdNiO2. Nat. Mater. 23, 486–491 (2024).

Parzyck, C. T. et al. Synthesis of thin film infinite-layer nickelates by atomic hydrogen reduction: clarifying the role of the capping layer. APL Mater. 12, 031132 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. In situ preparation of superconducting infinite-layer nickelate thin films with atomically flat surface. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401342 (2024).

Ding, X. et al. Cuprate-like electronic structures in infinite-layer nickelates with substantial hole dopings. Nat. Sci. Rev. 11, nwae194 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. Electronic structure of superconducting infinite-layer lanthanum nickelates. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr5116 (2025).

Rödel, T. C. et al. Universal fabrication of 2d electron systems in functional oxides. Adv. Mater. 28, 1976–1980 (2016).

Vicente-Arche, L. M. et al. Metal/SrTiO3 two-dimensional electron gases for spin-to-charge conversion. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 064005 (2021).

Vicente-Arche, L. M. et al. Spin–charge interconversion in KTaO3 2d electron gases. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102102 (2021).

Mallik, S. et al. Superfluid stiffness of a KTaO3-based two-dimensional electron gas. Nat. Commun. 13, 4625 (2022).

Varotto, S. et al. Direct visualization of Rashba-split bands and spin/orbital-charge interconversion at ktao3 interfaces. Nat. Commun. 13, 6165 (2022).

Gutiérrez-Llorente, A. et al. Toward reliable synthesis of superconducting infinite-layer nickelate thin films by topochemical reduction. Adv. Sci. 11, e2309092 (2024).

Cooper, R. A. et al. Anomalous criticality in the electrical resistivity of La2−xSrxCuO4. Science 323, 603–607 (2009).

Legros, A. et al. Universal T-linear resistivity and planckian dissipation in overdoped cuprates. Nat. Phys. 15, 142–147 (2019).

Bruin, J. A. N., Sakai, H., Perry, R. S. & Mackenzie, A. Similarity of scattering rates in metals showing T-linear resistivity. Science 339, 804–807 (2013).

Ding, X. et al. Stability of superconducting Nd0.8Sr0.2NiO2 thin films. Sci. China Physics, Mech. Astron. 65, 267411 (2022).

Zeng, S. et al. Phase diagram and superconducting dome of infinite-layer Nd1−xSrxNiO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 147003 (2020).

Rath, M. et al. Scanning tunneling microscopy and x-ray photoemission studies of NdNiO2 infinite-layer nickelates films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 054802 (2024).

Balakrishnan, P. P. et al. Extensive hydrogen incorporation is not necessary for superconductivity in topotactically reduced nickelates. Nat. Commun. 15, 7387 (2024).

Zeng, S. et al. Origin of a topotactic reduction effect for superconductivity in infinite-layer nickelates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 066503 (2024).

Gonzalez, M. et al. Absence of hydrogen insertion into highly crystalline superconducting infinite layer nickelates. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 084804 (2024).

Zhou, X.-R. et al. Negligible oxygen vacancies, low critical current density, electric-field modulation, in-plane anisotropic and high-field transport of a superconducting Nd0.8Sr0.8 NiO2/SrTiO3 heterostructure. Rare Metals 40, 2847–2854 (2021).

Tencé, M. et al. Electron energy-loss spectroscopy using MerlinEM - Medipix3 detector. Microsc. Microanal. 26, 1940 (2020).

Hytch, M. J., Snoeck, E. & Kilaas, R. Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from hrem micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 74, 131 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A. Gutiérrez-Llorente for her help in the initial optimization of the perovskite nickelate thin films by PLD. We also acknowledge the support by Xiaoyan Li in the STEM experiments and V. Humbert for his help with the electrical characterization in a cryostat from Cryogenic and scientific discussion. We thank L. Matera for his help in the development of the Python codes and R. Tomar for the scientific discussion on transport data. D. Z. acknowledges financial support from École Doctoral 564 Physique en Ile de France (EDPIF) and Université Paris-Saclay. This work was financed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under the project OxyNicks (ANR-24-CE09-3130-01) and by the framework of the joint ANR-RGC ImagingQM project (ANR, ANR-23-CE42-0027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. synthesized the samples (PLD growth), performed the experiments (aluminum reduction in sputtering chamber, XRD, XRR, electrical transport measurements) and analyzed the data. L.M.V.A. contributed to the development of the DC sputtering deposition process and data discussion and analysis. A.R. and A.G. performed the STEM experiments and analyzed the corresponding data. M.B discussed the data and provided the necessary equipment. L.I. conceived and supervised the project, assisted in the experimental measurements (RSM, XRD, XRR), substrates treatment, data discussion, and secured funding for the work. The manuscript was prepared by D.Z. and L.I. with input from all authors. All co-authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Raji, A., Vicente-Arche, L.M. et al. Accessible synthesis of superconducting nickelates via topotactic reduction induced by aluminum sputter deposition. Commun Mater 6, 293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01013-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01013-9