Abstract

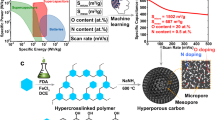

The application of alkali metal-based coordination polymers as precursors to porous materials for energy storage appears as a very promising, but yet essentially unexplored approach. Here, we provide comprehensive investigations of the alkali metal (Li, Na, K)-based coordination polymers with 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate as an organic linker, which revealed a variety of 2D and 3D coordination networks accessible in mild conditions and aqueous environment. The resulting coordination polymers were applied as self-templating precursors to porous carbon materials with hierarchical porosity, which exhibited Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas up to 1871 m2/g. Furthermore, the developed porous carbons were applied as supercapacitors and aqueous Zn-ion capacitors (AZICs), which showed promising specific capacitance, as well as high cyclic stability and rate capability. In particular, the top-performing device, prepared using the carbon material developed from the K-based coordination polymer, achieved one of the highest performances reported for AZICs, exhibiting a remarkable specific capacitance of 754.7 F g-1 at 0.1 A g-1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porous carbon materials have achieved extraordinary success in a variety of environment and energy-related applications1. The quest for efficient energy storage solutions has particularly fuelled a significant interest in these materials, renowned for their customizable pore structures, high surface areas, and exceptional electrochemical properties2,3,4,5,6,7. Among various possible synthetic strategies aimed at the preparation of porous carbon materials, the high-temperature carbonisation method appears as a promising solution due to its low cost and simplicity accompanied by the ability to produce materials with tailorable and well-defined pore structures, superior thermal stability as well as excellent scalability and reproducibility. The range of precursors used for preparation of porous carbons using the high-temperature carbonisation strategy involves a wide variety of materials such as natural and synthetic polymers8,9, biomass-derived materials10,11,12,13,14, organic salts15,16 as well as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) derived from transition metals17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The latter coordination networks are a structurally and compositionally diverse class of network solid which are amenable to crystal engineering by exploiting the interactions of metal centres (nodes) and organic ligands acting as linkers between these centres, an area whose profound impact on materials science has been acknowledged by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2025. MOFs stand out due to their various chemical compositions and well-defined crystalline structures acting as templates in the formation of precisely engineered pore architectures, enabling the production of carbon materials with uniform porosity and high surface areas. Remarkably, MOF-derived porous carbons show high application potential as supercapacitors and Zn-ion capacitors, since they can achieve high capacitance, cycling performance and rate stability25,26,27,28. The final electrochemical performance of these materials, however, is not determined by surface area alone; factors such as pore size distribution, pore connectivity, hierarchical (macro–meso–micro) porosity, degree of graphitisation, surface functionality, and structural stability all play significant roles in governing ion transport, charge transfer efficiency, and cycling stability21,29,30,31,32.

Alkali metal hydroxides, carbonates and other salts have been widely applied as activation agents in the preparation of porous carbons from organic precursors, due to the ability of alkali cations to facilitate the high-temperature chemical etching of carbon, and mediate the formation of materials with controlled porosity and morphology15,16,33,34. Direct comparisons between the use of LiOH, NaOH, or KOH as activation agents are scarce, but the available reports indicate that KOH produces carbons with the highest surface area and porosity, while NaOH and especially LiOH yield less developed pore structures35,36. Furthermore, molecular organic salts of alkali metals have been used as precursors in the self-templating strategy involving pyrolysis of the precursor followed by the removal of inorganic residues in order to achieve highly porous carbons15,16,37,38,39,40. Nevertheless, in comparison to the transition-metal based networks the alkali metal-based coordination networks remain vastly unexplored as self-templating precursors of porous carbon materials, represented by only a handful of papers41,42. This might be related to the scarcity of the s-block metal-based coordination polymers in comparison to the transition metal-based systems. Moreover, the alkali-based coordination networks are more flexible and potentially highly adaptive, but also more difficult to predesign, due to multitude of possible coordination geometries of the underlying metal centres43,44,45.

Despite their potential, systematic studies on the synthesis and properties of alkali-metal-based coordination networks remain scarce. Herein, in the course of our ongoing efforts towards development of functional 0D molecular systems46,47 as well as 1D48,49, 2D50,51,52,53, 3D54,55,56,57 coordination polymers and other hybrid organic-inorganic materials for energy-related applications58,59,60,61,62, we report on a simple and green approach to the synthesis of alkali metal-based coordination networks, showing promising potential as self-templating precursors for porous carbon materials (Fig. 1). The 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate (BTC) linker was selected for the study due to its central role in MOF chemistry, its availability and simplicity compared to more complex organic linkers as well as the relative scarcity of reports on alkali metal–BTC networks in comparison to their transition metal-based counterparts. A series of 2D and 3D Li+, Na+, K+-based coordination networks involving BTC linkers was prepared in multigram scale under mild conditions and structurally well-characterized. Then the resulting alkali-BTC coordination polymers were applied as sacrificial templates for porous carbons via thermolysis, yielding carbon materials of diverse porosity depending on the precursor type, which aims to combine the advantages of both coordination networks and alkali salts in the pyrolytic approach to formation of functional porous carbons. Moreover, the developed porous carbons with BET surface areas in the range of 961–1871 m2/g were examined as supercapacitors, showing promising specific capacitance values in the range of 163.2–213.4 F g−1 (at 0.1 A g−1). In this vein, the carbon materials were also tested as Zn-ion capacitors (AZICs), which revealed remarkable specific capacities up to 754.7 F g−1 at 0.1 A g−1 for the carbon material prepared using the potassium coordination network as a precursor. As suggested by the conducted analyzes, the electrochemical performance of the developed carbon materials was mainly governed by their internal porosity, particularly the specific−surface area and pore size distribution, arising from the rationally designed alkali–BTC coordination polymer precursors, although other structural or physicochemical factors may also contribute.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and structure of the alkali metal-based coordination polymers

A general experimental procedure of the alkali-BTC coordination network preparation involved the reaction of 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (H3BTC) with an alkali hydroxide (MOH, where M = Li, Na, K) in water, yielding an aqueous solution of the M3BTC salt, which was then used for crystallisation of alkali-BTC coordination networks upon introduction of an alcohol as an antisolvent. The structural analysis of the prepared alkali-BTC coordination networks puts a special emphasis on the secondary building units (SBUs) formed by the metal centres connected by the bridging carboxylate moieties, and dimensionality of the resulting materials.

Upon addition of isopropanol (iPrOH) to an aqueous solution of the Li3BTC salt, a white precipitate of [Li3BTC • 5H2O] (1 • 5H2O) coordination network was immediately formed, as evidenced by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The high-quality rod-shaped single crystals of (1 • 5H2O) were prepared by slow diffusion of iPrOH vapours into the Li3BTC solution in mixture of water and THF. The single crystal X-ray diffraction experiment (SCXRD) allowed for detailed structural investigation of the 1 • 5H2O (Pbca space group, details shown in Supplementary Table 1), which revealed that it forms 2D polymer layers perpendicular to the c axis. The tetrahedrally-coordinated lithium cations in 1 • 5H2O form two distinct SBU types: tetranuclear [Li4(O2CR)4 • 3H2O] cluster (Fig. 2a) and polymeric [Li(O2CR) • 2H2O]n representing 1D chain structure (Fig. 2b). The 2D coordination network layers in 1 • 5H2O are formed by connecting the SBUs using BTC linkers (Fig. 2c). Finally, the AA-type stacked 3D structure in 1 • 5H2O (Fig. 2d) is formed by supramolecular interactions between the 2D coordination networks. We note that the presented crystal structure of 1 • 5H2O appears similar to the results reported by Cheng et al.63. However, these similarities are difficult to evaluate since no crystal structure data of the corresponding material has been published. Therefore, the crystal structure of 1 • 5H2O has been presented here and deposited to the CCDC database accordingly.

A [Na3BTC • 3H2O] (2 • 3H2O) coordination network was prepared by adding ethanol (EtOH) to an aqueous Na3BTC solution, which resulted in an immediate precipitation of 2 • 3H2O as white crystalline powder, as confirmed using PXRD (Supplementary Fig. 2). High-quality single crystals of 2 • 3H2O could be prepared by slow diffusion of EtOH vapours to the aqueous Na3BTC solution, which allowed for the detailed structural investigations by SCXRD study (Supplementary Table 2). The solvate 2 • 3H2O crystallises in the P21 space group and forms a 3D coordination network structure. The Na+ cations in 2 • 3H2O are coordinated with 5 or 6 oxygen atoms forming distorted square pyramidal and octahedral motifs, respectively. The metal centres in 2 • 3H2O are linked by bridging carboxylate groups into complex SBUs: 2D layers extending in a direction perpendicular to the crystallographic b axis (Fig. 3a, b). The 2D SBUs are interconnected by the organic linkers forming the layered 3D coordination network structure (Fig. 3c).

An aqueous solution of the K3BTC salt was used to prepare a hydrated [K3BTC • 3H2O] (3 • 3H2O) coordination network, which was precipitated upon addition of iPrOH, as shown by PXRD study (Supplementary Fig. 3). Single crystals of 3 • 3H2O were prepared by exposition of the aqueous K3BTC solution to the iPrOH vapours, allowing for the detailed SCXRD study (Supplementary Table 3), which revealed that 3 • 3H2O crystallises in the P21/c space group and forms a 3D coordination polymer. The K+ cations in the 3 • 3H2O structure were coordinated by 6–8 oxygen atoms originating from carboxylate groups and water molecules. Interestingly, the SBU, defined as the collection of metal centers bridged by the carboxylate groups, extends indefinitely in all three directions in the crystal structure of 3 • 3H2O (Fig. 4).

Overall, we demonstrated a range of crystalline alkali-BTC coordination networks prepared by the simple aqueous synthetic route. The observed trends in the local coordination environment of metal cations were in agreement with the literature reports on alkali metal-based carboxylates43,44,45. Namely, lithium cation were always coordinated by four oxygen atoms in a quasi-tetrahedral geometry, while the heavier cations exhibited increasingly complex coordination geometries adopting up to 6 and 8 coordinated oxygen atoms for sodium and potassium, respectively. Moreover, the complexity of observed SBUs was also dependent on the cation type ranging from 0D and 1D SBUs for lithium-based networks to 3D SBUs for potassium.

Transformations of the alkali-BTC coordination networks to porous carbon materials

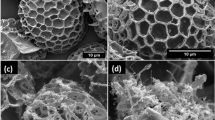

As discussed in the introduction part, a prospective application of coordination networks is their use as precursors for functional porous carbon materials, typically synthesised through pyrolysis in air-free conditions17,18,19,20. However, the application of alkali metal-based coordination networks in this area is still largely unexplored41,42, prompting our investigation into the applicability of materials 1 • 5H2O, 2 • 3H2O and 3 • 3H2O as precursors to functional porous carbon materials. In order to choose the transformation conditions, the thermal stability and decomposition pathways of the selected precursors were studied using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). As a result, it was found that upon thermal treatment all of the examined samples initially release the water molecules leading to non-hydrated M3BTC products, which were further decomposed in a pyrolytic process leading to the carbon materials (Supplementary Figs. 8–10). Additionally, variable-temperature powder X-ray diffraction (VTPXRD) experiments conducted in 25–350 °C range showed that the observed dehydration processes of 1 • 5H2O, 2 • 3H2O and 3 • 3H2O were accompanied by structural reorganisation (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). Based on the observed TGA curves, the temperature of 850 °C was selected for the pyrolytic transformations from alkali-BTC networks towards porous carbon materials. Consequently, ca. 10 g samples of materials 1 • 5H2O, 2 • 3H2O and 3 • 3H2O were pyrolysed in N2 atmosphere at 850 °C for 5 h and washed with aqueous H2SO4 (5%) in order to remove inorganic products (see experimental part for full synthetic details), yielding porous carbon materials 1C, 2C and 3C respectively. All of the developed materials were analysed using PXRD, which revealed their amorphous structure (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, SEM was used in order to study the morphology of 1C, 2C and 3C, demonstrating the highly developed surface of the studied materials (Fig. 5, and Supplementary Figs. 42–44). In particular, mesopores (2−50 nm in diameter) were observed mostly in material 1C (Fig. 5b, c) and 2C (Fig. 5e, f). Direct observation of micropores (<2 nm) was beyond the capabilities of conventional SEM, but the observed corrugated surface of studied carbon materials could suggest the presence of a highly developed underlying microporous network. The composition of the materials 1C, 2C and 3C was investigated using the elemental analysis and XPS spectroscopy (Supplementary Figs. 29–37), which revealed that they were consisting mainly of C (87.1%, 92.1% and 85.4%, respectively), O (11.5%, 7.5% and 13.9%, respectively) and small amounts of N (1.4%, 0.4% and 0.7%, respectively). All analysed samples exhibit similar spectral characteristics in the C 1s region, displaying four main components attributed to distinct carbon bonding. These include peaks corresponding to C–C bonds (284.8 eV), C–O bonds (286.1–286.3 eV), C=O and/or C–N bonds (287.5–287.8 eV), and O–C=O bonds (289.2–289.5 eV). Additionally, a distinct satellite peak associated with π–π* shake-up transitions, typical for carbon-based materials, is observed at binding energies ranging from 291.0 to 291.1 eV. Complementary features are observed in the O 1s core-level spectra. All materials show contributions from oxygen in C–O and C=O bonding, with peaks in the 532.0–532.5 eV and 533.5–533.8 eV ranges, respectively. In the case of 2C sample, a single, broader peak centered at 533.0 eV is likely the result of overlapping signals from both C–O and C=O bonds. Furthermore, weak satellite features characteristic of oxide-like species are present in the higher binding energy region of 535.0–535.5 eV. The N 1s spectra for all samples show a single peak located between 400.0 and 400.7 eV, which can be attributed to nitrogen atoms involved in C–N bonding. This consistent presence across all samples confirms the incorporation of nitrogen into the carbon at the surface, which results from the N2 atmosphere maintained during the pyrolysis process. Notably, no trace of Li, Na and K has been detected using XPS spectroscopy, which indicates complete removal of the inorganic products by the H2SO4 washing. Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy was used to investigate the structural features of the developed porous carbon materials, which revealed typical spectra for amorphous carbon in all of the 1C, 2C and 3C materials (Supplementary Fig. 38) involving two broad peaks with maxima at ca. 1344−1351 cm−1 (D-band) and 1582–1586 cm−1 (G-band). The Id/Ig ratios in the studied porous carbon materials were: 2.78, 2.40 and 2.76 for 1C, 2C and 3C, respectively, which is also common for porous carbons with amorphous structure.

Gas adsorption studies of the developed porous carbon materials

In order to evaluate the gas adsorption properties of the developed carbon materials 1C, 2C and 3C we conducted isothermal N2, H2, CO2 and CH4 adsorption studies following the initial thermal activation process (150 °C, 20 h). The N2 adsorption isotherms collected at 77 K of all of the samples 1C, 2C and 3C revealed significant gas uptakes at low pressures, characteristic to the microporous materials, which allowed for determination of the BET areas of 961, 1572 and 1871 m2/g, respectively. However, N2 adsorption isotherms of samples 1C and 2C showed further increasing gas adsorption capacity at higher pressures (p/p0 close to 1), up to 1081 and 718 cm3/g, respectively (Fig. 6a). Moreover, the N2 desorption curves for 1C and 2C show significant hysteresis at p0/p range 0.45–1.0, which is typically related to the capillary condensation in mesoporous materials. Overall, the N2 adsorption experiments indicate that while material 3C shows properties typical to microporous materials, the samples 1C and 2C involve hierarchical microporous – mesoporous structure. This conclusion is further supported by the NLDFT pore size distribution calculations (Supplementary Figs. 15–17). The H2 adsorption experiments (at 77 K) for 1C, 2C and 3C demonstrated their relatively high adsorption capacities of 150.0, 226.4 and 270.7 cm3/g, respectively (Fig. 6b). Further gas adsorption studies of materials 1C, 2C and 3C involving CO2 and CH4 revealed capacities of 78.6, 108.7 and 134.9 cm3/g (adsorption of CO2 at 0 °C); 51.6, 68.4 and 82.0 cm3/g (adsorption of CO2 at 25 °C); 33.3, 48.0 and 58.3 cm3/g (adsorption of CH4 at 0 °C); 21.9, 31.0 and 37.7 cm3/g (adsorption of CH4 at 25 °C), respectively (Supplementary Figs. 11–14). In comparison to the similar materials reported earlier, the developed porous carbon materials 1C, 2C and 3C are characterised with relatively high porosity and promising gas adsorption properties19,64. For example, application of other BTC-based MOFs including transition metal centres (Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd) as sacrificial templates in pyrolysis was reported to yield porous carbon materials with BET surface areas ranging from 86 to 1558 m2/g depending on the precursor type65. Similar materials based on K-BTC and Mg-BTC coordination networks as precursors showed hierarchical porosity and BET areas of 1192 and 370 m2/g, respectively41,66. Furthermore, various MOFs constructed from linkers other than BTC have been investigated as precursors to porous carbons. For example, pyrolysis of members of the IRMOF family led to the preparation of a series of porous carbons with surface areas ranging from 1543 to 3174 m²/g67. Similarly, pyrolysis of various ZIF materials allowed preparation of porous carbons with BET surface areas ranging from 1067 to 3405 m2/g67,68.

Electrochemical studies - symmetrical supercapacitors

The electrochemical energy storage behaviour of the fabricated carbon materials was first evaluated in symmetrical supercapacitor device architecture. The identical electrodes were assembled in Swagelok-type cells using 6.0 M aqueous KOH electrolyte and cycled in a voltage window of 0.0–0.8 V. The cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of the fabricated supercapacitors devices with 1C, 2C and 3C electrodes at a scan rate of 1.0 mV s−1 were provided in Fig. 7a. The fabricated supercapacitors exhibited a rectangular CV curve shape, reflecting the electrical double layer capacitor type behaviour. Among the fabricated supercapacitors, 3C devices showed the highest current density at same scan rates. The CV measurements were performed at different scan rates from 1.0 to 100,000 mV s−1, and the CV graphs for 3C were provided in Fig. 7b, c (please see Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19 for 1C and 2C devices, respectively). The 3C supercapacitors showed a rectangular CV curve shapes up to 2000 mV s−1 and then a slight deviation in the curve shape was observed at higher scan rates. When the CV scans were performed at high sweep rates, the devices may not have enough time for the polarisation, and it may result in the deviation in the curve shape. Therefore, it is quite natural to have a deviation in shape when the sweep rate reached 10,000 mV s−1. In Fig. 7d, the galvanostatic charge-discharge curves (GCDs) were demonstrated. At 1.0 A g−1, the fabricated devices showed highly symmetrical curves, reflecting high Coulombic efficiencies. The discharge times at 1.0 A g−1 were found as 56.0, 62.5 and 77.8 s for the 1C, 2C and 3C supercapacitors, respectively. The internal resistance drop (IRdrop) values were also calculated for the fabricated devices and the obtained values were 15.8, 1.55 and 0.72 Ω for the 1C, 2C and 3C supercapacitors, respectively. The high Coulombic efficiencies and low IRdrop values indicate that the fabricated devices have a good charge storage behaviour. The GCD measurements were repeated at various current densities from 0.1 to 80.0 A g−1 and the GCD curves for the 3C supercapacitor were provided in Fig. 7e (please see Supplementary Fig. 20 for 1C and 2C devices). The 3C supercapacitor showed a slightly low Coulombic efficiency (77%) at 0.1 A g−1 and the CE was almost 100% at higher current densities. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) measurement was performed to investigate the charge transfer properties of the fabricated supercapacitors (Fig. 7f). The EIS measurement was performed at 0.0 V DC at 20 mV AC perturbation within a frequency range of 100 kHz to 10 mHz. At the high frequency region of the EIS spectra, a semicircle formation due to the contact interface impedance among carbon particles and particles/current collector was observed for all samples. The Rct values were found as 23.76, 1.76, and 0.57 Ω for the 1C, 2C and 3C supercapacitors, respectively. The low Rct of 3C supercapacitor results in improved charge transfer property of the fabricated device. At the low frequency region, sharp slope of the EIS curves also reflect the EDLC type charge storage.

The specific capacitances of the developed supercapacitors were calculated using the GCD curves and plotted with respect to current densities (Fig. 8a). The specific capacitances of 1C, 2C, and 3C supercapacitors are 163.2, 170.5, and 213.4 F g−1, respectively, at a current density of 0.1 A g−1, which is a considerable result with respect to similar porous carbon materials prepared using coordination polymers as precursors42. The high surface area of the 3C demonstrated an EDLC-type behaviour, reflecting a dominant surface capacitive charge storage in electrochemical kinetics (Fig. 8b). In order to evaluate the service lifetime and the capacitance retention of the fabricated supercapacitors the long-term GCD measurements were conducted. As shown in the Fig. 8c, the supercapacitors prepared using the 1C and 2C materials exhibited high cycling stability for 10,000 cycles, both retaining 90.5% capacitance, respectively, and achieving nearly 100% CE. On the other hand, 3C supercapacitor exhibited 69.1% capacitance retention after 10,000 GCD cycles. The differences in the charge transfer properties of the developed porous carbon materials are directly related to their distinct structural features. In particular, it is known that various parameters, such as the particle size, crystal structure, active surface area, layer thickness, porosity, surface composition, and morphology, can be responsible for significantly altering the electrochemical properties of porous materials69,70. Furthermore, while the pore structure engineering plays a critical role in achieving high power performance of capacitors, other effects, such as irreversible chemical reactions, electrolyte degradation or structural damage upon repeated charge/discharge cycling, might limit their capacitance retention and overall performance30. In particular, the different charge transfer resistance observed for 1C, 2C and 3C could be explained by their distinct porosity, but also the fact that KOH was used as electrolyte for the conducted tests, which favours the 3C material prepared from the potassium-based precursor (3 • 3H2O) due to the well-matched pore size. However, the high porosity of the 3C material might also be the reason for its limited capacitance retention due to various factors like lower structural stability or possible irreversible chemical transformations. Moreover, while the use of Na, K and Cs salts as activators in the high-temperature carbonisation process is well studied15,16,33,34, the similar approach employing Li salts is still greatly unexplored. The surprisingly poor rate capability of supercapacitor prepared using material 1C most likely is related to the pore bottlenecks limiting their accessibility to KOH electrolyte, but more in depth investigations in this area exceed the scope of this report and will be published in due course.

a Csp of the prepared supercapacitors (lines for the visual aid), b Electrochemical kinetics of the supercapacitor fabricated using material 3C, c Cycle life measurements of the developed supercapacitors at the current density of 2.0 A g−1 (closed symbols denote capacitance retention, open symbols denote coulombic efficiency).

The immittance spectra of the systems studied (see Fig. 9) reveal two processes of significantly different timescales. First characterised with t1 = ca. 2000 to ca. 9000 s is to be attributed to the self-discharge of the system investigated, while the other (t2 = ca. 0.5 to ca. 3.5 s) should be correlated with processes of intercalation/deintercalation of ions into the structure of the porous carbon. The differences between the performance of the materials determined earlier in the course of the investigation can be, therefore, correlated with the transport properties of the porous media and with the kinetics of the electrochemical pseudo-reaction (intercalation) occurring. While the absolute values (see Supplementary Table 8) of the resistance (R2) correlated with the charge transfer processes are the highest for material 1C and the lowest for 2C their change upon cycling reveals significant (threefold) decrease in the former case a non-significant (20%) increase in the latter while material 3C related parameters remains intact. Contrastively, the correlated pseudo capacitance values (Q2) do not reveal any meaningful changes, but theirs dispersion related exponent (a2) increases meaningfully upon cycling for 1C and 2C remaining intact for their 3C counterpart. In consequence while the initial values of these parameter were similar for all materials studied (ca. 0.68) their changes upon cycling observed for materials 1C and 2C prove the presence of the ordering processes occurring in these materials within the experiments course. This proves the improvement of the charge accepting capabilities of Li templated material (1C) upon cycling, but in the case of two others such a change is not observable. A complementary set of observations can be derived from the analysis of the variability of the Ma diffusion element defining parameters. In this case diffusion resistance (Rd) values decrease of about one order of magnitude between both 1C and 2C, as well as, 2C and 3C materials proving that the increasing volume of the pre-templated cavity correlated with the ionic radii of the cations incorporated into the structure of the precursor significantly favours the mass transport processes in the potassium, based porous carbon (3C). On the other hand their changes upon cycling reveal a differing scheme of changes when compared to their R2 counterpart increasing 2.5 times for 1C and 36% for 3C and no change for 2C. On the other hand, the diffusion related time constant td is not an order of magnitude higher for 1C material when compared with 2C and 3C ones but exhibits a 3,5 times increase upon cycling. A more detailed comparison of 2C and 3C reveal not only slightly higher initial value of 3C in comparison with 2C but also proves the ca. 25% increase of this value observed upon cycling for 3C. Finally, the measure of the diffusion dispersion (ad) proves that lithium templated material (1C) is initially less uniform than its sodium and potassium based counterparts (2C and 3C) but exhibits the most profound ordering process upon cycling. Thus, it can be stipulated that the lack of the above mentioned ordering processes in material 3C differing it from its 1C and 2C counterparts can be correlated with the variability of the evolution of their performance upon cycling.

Furthermore, to exclude the influence of electrode formulation on the performance trends, it should be emphasised that 20 wt% of conductive carbon black was incorporated into all electrodes to provide comparable electrical conductivity and mechanical stability. Importantly, this constant proportion ensures that any contribution of carbon black to charge storage remains identical across samples. Although carbon black can contribute to double-layer capacitance, its intrinsic capacitance is significantly lower than that of engineered porous carbons. This is well established in the literature, where carbon black is widely described as functioning primarily as a conductive additive rather than a main active material in charge storage71,72. Moreover, studies investigating electrodes composed solely of carbon black report relatively low capacitance values and indicate that its principal contribution lies in forming efficient electron-transport pathways within composite electrodes73,74. Therefore, the differences in capacitance, rate capability, and cycling behaviour observed for the studied materials arise from the intrinsic textural and structural properties of the MOF-derived carbons, rather than from variations in the conductive additive.

Electrochemical studies - aqueous zinc-ion capacitors

The electrochemical charge storage properties of the fabricated carbon materials were also investigated in AZIC device architecture. The AZIC devices were assembled in Swagelok-type cells using the fabricated carbon electrodes (1C, 2C, or 3C) as the cathode, Zn metal foil as the anode, glass fiber membrane as a separator and 3.0 M aqueous ZnSO4 as the electrolyte. The CV curves of the fabricated AZICs were obtained in a voltage window of 0–1.8 V at a scan rate of 1.0 mV s−1. As shown in Fig. 10a, the CV curves of the fabricated devices demonstrate a quasi-rectangular curve shape representing a mixed EDLC type and pseudocapacitive-type behaviour. Metal-ion capacitors utilise both EDLC-type and battery-type electrodes and they demonstrate a combined charge storage mechanism. The observed broad peak around 0.8 V is due to the pseudocapacitive contribution of the heteroatom content of the fabricated carbon materials. Among the fabricated cathodes, 3C showed the highest current - density reflecting the high charge storage capacity. CV measurements were repeated at various scan rates from 1.0 to 2000 mV s−1 and the CV results were provided in Fig. 10b, c for 3C cathode (please see Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22 for 1C and 2C cathodes, respectively). The fabricated AZICs have similar CV curve shapes and also have quite good rate capabilities. The electrochemical kinetics of the fabricated devices were analysed using the CV curves at scan rates between 1 and 20 mV s−1. The surface capacitive and diffusion-controlled contributions were calculated using the Dunn method75. As shown in Fig. 11b and Supplementary Figs. 24–26, the diffusion-controlled contribution was dominant at low scan rates and the diffusion-controlled contribution was decreased with the increasing scan rate. The surface capacitive charge storage is dominant at all scan rates. The galvanostatic charge-discharge measurements of the fabricated AZIC devices were performed in a voltage window of 0.0–1.8 V and the GCD curves of the AZICs at 0.1 A g−1 was provided in Fig. 10d. The cathodes have almost isosceles triangular curve shapes, reflecting the high Coulombic efficiencies. The discharge times at 1.0 A g−1 were found as 386.3, 444.1, and 679.5 s for the 1C, 2C and 3C AZIC devices, respectively. The IRdrop values were also calculated for the fabricated devices and the obtained values were 21.5, 9.2, and 4.7 Ω for the 1C, 2C and 3C devices, respectively. The low IRdrop value of 3C indicates the good charge transfer at electrode-electrolyte interface and the conductive nature of the 3C material. It is also noteworthy to mention that the GCD curve slopes of the AZIC devices were decreasing at voltage region 0.0–0.3 V, which indicates the capacitance increase due to the pseudocapacitance contribution of hydrogen-involved reactions76. The GCD measurements were also performed at higher current densities up to 20 A g−1 and the GCD curves for the 3C AZIC were provided in Fig. 10e (please see Supplementary Fig. 23 for 1C and 2C devices). The 3C AZIC exhibited a high Coulombic efficiency (nearly 100%) at all current densities and good rate capability. EIS analysis was also performed to AZICs to assess the charge transfer characteristics (Fig. 10f). All AZIC devices had a serial resistance (Rs) of 2.32–2.48 Ω. In the high-frequency region of the EIS spectra, a semicircle indicative of charge transfer resistance at the electrode-electrolyte interface was observed in all samples. The Rct were determined as 5.91, 8.25, and 2.72 Ω for the 1C, 2C, and 3C devices, respectively. The notably low Rct of the 3C supercapacitor suggests enhanced charge transfer properties in the fabricated device. The specific capacitances of the developed AZIC devices were calculated using the GCD curves and plotted with respect to current densities (Fig. 11a). The specific capacitance values for AZIC devices prepared using the 1C, 2C and 3C porous carbon materials were found as 588.4, 475.5, and 754.7 F g−1, respectively, at 0.1 A g−1. When the current density was increased to 20 A g−1, the Csp was found as 168.3, 139.3, and 224.1 F g−1 for the 1C, 2C, and 3C AZICs, respectively (more details in Supplementary Tables 4–6). The AZICs showed remarkable Csp values at low current densities and then Csp values become constant at high current densities. The obtained results demonstrate that the fabricated devices have an impressive rate capability. The high rate capability of 3C is attributed to the dominant surface capacitive charge storage mechanism (Fig. 7b). The AZIC device prepared using the 3C material demonstrated one of the highest specific capacitance values ever reported for similar devices (Supplementary Table 7). The long-term GCD measurements were employed in order to evaluate the stability and lifetime of the developed AZIC devices. As a result, it was found that 95.3, 82.6, and 78.7% of the capacitance retained after 3800 cycles at 2.0 A g−1 for AZIC devices prepared using 1C, 2C and 3C materials, respectively. Finally, the energy densities and power densities of the developed supercapacitors and AZIC devices were compared to the typical values on a Ragone plot (Fig. 12). As shown, the 3C AZIC device shows a high energy density of 336.6 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 89.7 W kg−1, which maintains 74.4 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 15,460 W kg−1. The fabricated supercapacitor devices show high energy densities in comparison to the recent reports. The AZICs devices exhibit battery-level energy densities while maintaining their high power densities. The obtained results show that the fabricated devices can be used as energy and power sources for many application, which requires high electrochemical performance77. However, the reported values represent material-level performance based solely on the mass of active electrode materials, and the practical device-level values would be lower due to the contribution of inactive components.

a Csp of the prepared AZIC devices (lines for the visual aid), b Electrochemical kinetics of the AZIC device fabricated using material 3C, c Cycle life measurements of the developed AZIC devices at the current density of 2.0 A g−1 (closed symbols denote capacitance retention, open symbols denote coulombic efficiency).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated comprehensive investigations concerning the development of alkali metal-based coordination networks involving Li, Na and K ions and the tricarboxylate BTC linker and their application as well-defined precursors of carbon materials. Our approach allowed for simple and green synthesis of the alkali-BTC networks under mild, aqueous conditions. Notably, the developed procedure allowed for preparation of a range of coordination networks as single crystals, which facilitated the detailed structural investigations using diffraction techniques. Moreover, the resulting alkali-BTC networks were used as sacrificial self-templating precursors to porous carbon materials via the pyrolysis process. Interestingly, the surface area and gas adsorption capabilities of the resulting carbon materials were highly dependent on the type of precursor used. Finally, the developed porous carbon materials were investigated in terms of their applicability as supercapacitors and aqueous Zn-ion capacitors, which revealed very promising electrochemical performances. In particular, the AZIC device manufactured using the carbon material derived from K-based coordination polymer displayed an impressive specific capacitance: 754.7 F g−1, which is one of the highest values ever reported for this type of devices. The observed differences in electrochemical performance among the developed porous carbon materials could be attributed to the various porosity demonstrated by the gas adsorption study. Overall, we demonstrated an extensive study of alkali metal carboxylate networks, offering valuable insights into this relatively unexplored area of research. While a direct correlation between the structure of the linker or the precursor coordination network and the final carbon characteristics cannot yet be established with full scientific rigor, as systematic comparisons involving alkali metal–based coordination networks employing other organic linkers are essentially lacking, we believe that the reported work provides an essential step toward understanding structure–property relationships in s-block MOF-derived carbons and highlights the potential of alkali–BTC coordination networks as versatile and rationally designable precursors. Further insights into the rational development of porous carbons for electrochemical applications based on design of the alkali metal-based coordination network precursors could be achieved by detailed investigation of systems involving other organic linkers, which are currently in progress.

Methods

General considerations

All chemicals were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Spectroscopic grade ethanol (EtOH) and isopropyl alcohol (iPrOH) as well as deionised water were used.

Synthesis of Li3BTC • 5 H2O (1 • 5 H2O)

LiOH • H2O (3 g, 72 mmol) was dissolved in 5 ml of water. Next, H3BTC was added (5.0 g, 24 mmol). The mixture was heated to 50 °C and shaken until the observed pH (analysed using standard indicator paper) was close to neutral. Afterwards the mixture was filtered and 50 ml of iPrOH was added, which resulted in deposition of white precipitate of 1 • 5 H2O. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with iPrOH and dried at room temperature. Yield: 7.4 g (97%). Elemental analysis (%) found: C 34.06, H 4.08; cacld for the formula [C9H3O6Li3 • 5 H2O]: C 33.99, H 4.12. Grain size of the 1 • 5 H2O crystals precipitated directly was in the range 1–15 µm (Supplementary Fig. 37). Single crystals of 1 • H2O could be prepared by slow diffusion of iPrOH vapours into the Li3BTC solution in water and THF.

Synthesis of Na3BTC • 3 H2O (2 • 3 H2O)

Preparation of 2 • 3 H2O was conducted following the same procedure as for 1 • 5H2O, but using NaOH (2.85 g, 72 mmol) instead of LiOH and EtOH instead of iPrOH. Yield: 7.5 g (95%). Elemental analysis (%) found: C 32.69, H 2.80; cacld for the formula [C9H3O6Na3 • 3 H2O]: C 32.74, H 2.75. Grain size of the 2 • 3 H2O crystals precipitated directly was in the range 0.5–5 µm (Supplementary Fig. 38). Single crystals of 2 • 3 H2O were obtained by slow diffusion of EtOH vapours into the Na3BTC solution in water.

Synthesis of K3BTC • 3 H2O (3 • 3 H2O)

Preparation of 3 • 3 H2O was conducted following the same procedure as for 1 • 5H2O, but using KOH (2.85 g, 72 mmol) instead of LiOH. Yield: 8.8 g (97%). Elemental analysis (%) found: C 38.65, H 2.33; cacld for the formula [C9H3O6K3 • 3 H2O]: C 28.56, H 2.40. Grain size of the 3 • 3 H2O crystals precipitated directly was in the range 0.5–10 µm (Supplementary Fig. 39). Single crystals of 3 • 3H2O were obtained by slow diffusion of iPrOH vapours into the K3BTC solution in water.

Synthesis of porous carbon materials 1C, 2C and 3C

All of the porous carbon materials (1C, 2C and 3C) were prepared using the same procedure, but different starting materials, i.e., 1 • 5H2O, 2 • 3H2O and 3 • 3H2O, for 1C, 2C and 3C, respectively. The starting material (10 g) was placed in the alumina crucible, which was inserted into the tube furnace equipped with N2 supply. Prior to the reaction the tube furnace was flushed with dry N2 for 2 h. The pyrolysis reaction was conducted for 5 h at 850 °C and the furnace was cooled to room temperature afterwards. The products were removed from the furnace and washed with deionised water (caution: The crude pyrolysis products might spontaneously ignite upon exposure to fresh air. This is most likely initiated by the reaction of metal oxides with CO2). Next, the products were washed with 5% aqueous H2SO4 in order to remove all of the inorganic residues. Afterwards the products were washed several times with deionised water until the pH of the liquid was neutral. Finally the products were washed with MeOH twice and dried at 80 °C for 24 h. Depending on the starting material used this procedure yields 1,04 g of 1C, 0.98 g of 2C or 0,93 g of 3C.

Materials characterization

Elemental analyses were carried out with an UNICUBE Elementar Analyser (Elementar GmbH). SEM imaging was performed using FEI Nova NanoSEM 450 system equipped with a field emission electron gun operating at 2 kV. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out with the TA Instruments Q600 analyser (25–1000 °C temperature range) in argon flow (100 mL min−1) in open alumina crucibles. XPS spectra were recorded using a Microlab 350 (Thermo Electron, East Grinstead, UK) spectrometer. For this purpose, non-monochromatic AlKα (hν = 1486.6 eV, power 300 W) radiation was used as the X-ray excitation source, with a lateral resolution of about 0.2 cm2. The high-resolution XPS spectra were recorded using the following parameters: pass energy 40 eV, energy step size 0.1 eV. Shirley function of background subtraction was used to obtain the XPS signal intensity. All the collected XPS peaks were fitted using an asymmetric Gaussian/Lorentzian mixed function. The measured binding energies were corrected in reference to the energy of C 1s at 284.8 eV. CasaXPS data system software was used to process the data. Raman spectra were recorded at room temperature using samples sealed inside 4 cm3 glass vials with the Nicolet Almega spectrometer equipped with diode laser (532 nm excitation wavelength). The spectra deconvolution was performed by Lorentzian fitting.

Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) data were collected on the Empyrean diffractometer (PANalytical) employed with Ni-filtered Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 40 mA) using Bragg-Brentano geometry and Si zero-background holder. The Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD) data for the reported complexes were collected at 100(2)K on a SuperNova Agilent diffractometer and using CuKa radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). Variable-Temperature Powder X-Ray Diffraction (VTPXRD) data were collected using the Aton-Paar TTK-450 temperature control camera.

Gas sorption studies were undertaken using a Micromeritics Instrument Corporation (Norcross, Georgia, USA) ASAP 2020 system. Approximately 100–150 mg of the corresponding solid product was transferred to a pre-weighed sample tube and evacuated under vacuum at 100 °C on the gas adsorption apparatus until the outgas rate was <5 μmHg. All gases used were of 99.999% purity. Helium was used for the free space determination after sorption analysis. Adsorption isotherms of N2 and H2 were measured at 77 K in a liquid nitrogen bath. Adsorption isotherms of CO2 and CH4 were measured at 273 K and 298 K in methanol bath controlled by circulating refrigerated medium. Pore size distributions were calculated using the NLDFT model implemented in the ASAP 2020 software.

X-ray structure determination of alkali metal-based coordination compounds

The Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD) data for the reported complexes were collected at 100(2)K on a SuperNova Agilent diffractometer and using CuKa radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). The single crystals of 1•5H2O, 2•3H2O and 3•3H2O were selected under Paratone-N oil, mounted on the nylon loops and positioned in the cold stream on the diffractometer. The SCXRD data were processed with CrysAlisPro, Data Collection and Processing Software for Agilent X-ray Diffractometers78. The structures 1 • 5 H2O, 2 • 3 H2O and 3 • 3 H2O were solved by direct methods using the SHELXT program and were refined by full matrix least–squares on F2 using the program SHELXL79. implemented in the OLEX280 or WinGX81 suite. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. H atoms on C atoms were added to the structure model at geometrically idealized coordinates and refined as riding atoms. H atoms of H2O molecules were located from a Fourier map (Supplementary Tables 1–3). Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structure reported in this paper have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as a supplementary publication. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21EZ, UK (fax: (+44)1223-336-033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk). CCDC: 2359247 (1 • 5 H2O), 2359249 (2 • 3H2O), 2359251 (3 • 3H2O).

Electrochemical studies

The porous carbon (1C, 2C, or 3C) electrodes were prepared by mixing the carbon material with polymeric binder polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and the conductive additive carbon black (Super P) to form a homogeneous slurry in ethanol with a weight percentage of 70/10/20. When the ethanol was evaporated, the slurry became a dough and it was cut into small disks (diameter: 8-mm). The electrode disks were dried in a vacuum oven for 12 h at 80 °C. The active material loading is around 1.0–2.2 mg/cm2. The reported specific capacitances (F/g) were calculated using the active mass in the electrode. For AZICs, the electrochemical measurements were carried out in a voltage window of 0–1.8 V using a multichannel Bio-Logic VMP3e potentiostat/galvanostat system (Biologic, Seyssinet-Pariset, France).

The electrochemical measurements were done using two-electrode configurations for the symmetrical supercapacitors. The supercapacitors were prepared by sandwiching two electrodes with Whatman (GF/A) glassy fiber membrane which was wetted by 6.0 M aqueous KOH electrolyte. Aqueous Zn-ion capacitors (AZIC devices) were also assembled using the Swagelok type cells and the fabricated electrodes were used as cathodes, Zn metal foil (250 µm thick, Alfa Aeasar) as anode, 3.0 M aqueous ZnSO4 solution as the electrolyte and the glassy fiber membrane as a separator. The Swagelok cells were sealed at ambient conditions and the electrochemical measurements were also done under the same conditions. For symmetrical supercapacitors, electrochemical measurements were carried out in a voltage window of 0–0.8 V. For AZICs, the electrochemical measurements were carried out in a voltage window of 0–1.8 V using a multichannel Bio-Logic VMP3e potentiostat/galvanostat system. A LANDT-CT3002A battery-cycler instrument was used for the galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) measurements. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed at DC 0.0 V using an AC perturbation signal of 20 mV, and the frequency ranged from 100 kHz to 100 mHz. Energy (E, Wh kg−1) and power densities (P, W kg−1) of the fabricated AZIC devices were determined using the following equations82:

Where C (F/g) is the capacitance, V (V) is the voltage window, and t (s) is the discharge time. For each measurements 5 cycles were performed, and the value recorded in the 5th cycle was reported. The standard deviation of capacitance values is less than 1%.

The EIS data gathered (doubled and averaged measurements performed prior and after the system cycling) were later transferred to RelaxIS analytic software and fitted to equivalent circuits depicted in Supplementary Fig. 27 (symmetrical supercapacitors) and 28 (zinc-ion capacitors). The Ma open circuited transmission line-based element used for the description of the diffusion processes in the porous carbons were defined according to works of Diard et al.83 and Bisquert et al.84. In the case of ZIC’s the immittance image of the zinc electrode was built upon previously repoted models85,86 further modified with the use of non-ideal inductance (La) element87 and subsequently verified by an independent EIS experiment utilizing symmetrical Zn||Zn cell filled with the same electrolyte.

Data availability

Data for this article are available at Repository for Open Data (RepOD) at https://doi.org/10.18150/ET8JPX88 Crystallographic data for 1 • 5H2O, 2 • 3H2O and 3 • 3H2O has been deposited at the CCDC database under 2359247, 2359249 and 2359251 and can be obtained free of charge on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21EZ, UK (fax: (+44)1223-336-033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

References

Tian, W. et al. Porous carbons: structure-oriented design and versatile applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909265 (2020).

Sun, Z., Chu, S., Jiao, X., Li, Z. & Jiang, L. Research progress of carbon cathode materials for zinc-ion capacitors. J. Energy Storage 75, 109571 (2024).

N., R. Y., Sharma, K. & Shafi, P. M. An overview, methods of synthesis and modification of carbon-based electrodes for supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage 55, 105727 (2022).

Kothandam, G. et al. Recent advances in carbon-based electrodes for energy storage and conversion. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301045 (2023).

Sheoran, K. aramveer, Thakur, V. K. & Siwal, S. S. Synthesis and overview of carbon-based materials for high performance energy storage application: a review. Mater. Today Proc. 56, 9–17 (2022).

Yin, J., Zhang, W., Alhebshi, N. A., Salah, N. & Alshareef, H. N. Synthesis strategies of porous carbon for supercapacitor applications. Small Methods 4, 1900853 (2020).

Zhong, M., Zhang, M. & Li, X. Carbon nanomaterials and their composites for supercapacitors. Carbon Energy 4, 950–985 (2022).

Vinodh, R. et al. A review on porous carbon electrode material derived from hypercross-linked polymers for supercapacitor applications. J. Energy Storage 32, 101831 (2020).

Xu, F., Wu, D., Fu, R. & Wei, B. Design and preparation of porous carbons from conjugated polymer precursors. Mater. Today 20, 629–656 (2017).

Yuksel, R. & Karakehya, N. High energy density biomass-derived activated carbon materials for sustainable energy storage. Carbon 221, 118934 (2024).

Chakraborty, R. K. V., Pradhan, M. & Nayak, A. K. Recent advancement of biomass-derived porous carbon based materials for energy and environmental remediation applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 6965–7005 (2022).

Priya, D. S., Kennedy, L. J. & Anand, G. T. Emerging trends in biomass-derived porous carbon materials for energy storage application: a critical review. Mater. Today Sustain. 21, 100320 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Biomass derived carbon for energy storage devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 2411–2428 (2017).

Yan, B. et al. High performance supercapacitors based on wood-derived thick carbon electrodes synthesized via green activation process. Inorg. Chem. Front. 9, 6108–6123 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Progress in the use of organic potassium salts for the synthesis of porous carbon nanomaterials: microstructure engineering for advanced supercapacitors. Nanoscale 14, 8216–8244 (2022).

Sevilla, M., Díez, N. & Fuertes, A. B. More sustainable chemical activation strategies for the production of porous carbons. ChemSusChem 14, 94–117 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. Multidimensional MOF-derived carbon nanomaterials for multifunctional applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 9721–9747 (2023).

Chen, D., Wei, L., Li, J. & Wu, Q. Nanoporous materials derived from metal-organic framework for supercapacitor application. J. Energy Storage 30, 101525 (2020).

Liu, D. et al. Recent advances in MOF-derived carbon-based nanomaterials for environmental applications in adsorption and catalytic degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 131503 (2022).

Ren, J. et al. Recent progress on MOF-derived carbon materials for energy storage. Carbon Energy 2, 176–202 (2020).

Chu, X., Meng, F., Deng, T. & Zhang, W. Metal organic framework derived porous carbon materials excel as an excellent platform for high-performance packaged supercapacitors. Nanoscale 13, 5570–5593 (2021).

Kim, M. et al. MOF-derived nanoporous carbons with diverse tunable nanoarchitectures. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2990–3027 (2022).

Dang, S., Zhu, Q.-L. & Xu, Q. Nanomaterials derived from metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17075 (2017).

Zhang, G., Li, X., Liu, Y., Du, G. & Pang, H. Metal–organic framework derived micro-/nano-materials: precise synthesis and clean energy applications. Inorg. Chem. Front. 11, 6275–6306 (2024).

Li, H. et al. A zinc ion hybrid capacitor based on sharpened pencil-like hierarchically porous carbon derived from metal–organic framework. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 131071 (2022).

Wei, Y. et al. Achieving high-performance aqueous Zn-ion hybrid supercapacitors by utilizing zinc-based MOF-derived N-doped carbon. Ionics 28, 3477–3488 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. A UiO-66-NH2 MOF derived N doped porous carbon and ZrO2 composite cathode for zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 10, 2115–2124 (2023).

Xiong, T., Shen, Y., Lee, W. S. V. & Xue, J. Metal Organic framework derived carbon for ultrahigh power and long cyclic life aqueous Zn ion capacitor. Nano Mater. Sci. 2, 159–163 (2020).

Song, J. et al. Research progress on metal organic framework derived porous carbon though interfacial engineering and synergistic effect. J. Power Sources 604, 234471 (2024).

Supiyeva, Z., Pan, X. & Abbas, Q. The critical role of nanostructured carbon pores in supercapacitors. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 39, 101249 (2023).

Mishra, S. et al. The impact of physicochemical features of carbon electrodes on the capacitive performance of supercapacitors: a machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 13, 6494 (2023).

Lobato-Peralta, D. R., Okoye, P. U. & Alegre, C. A review on carbon materials for electrochemical energy storage applications: state of the art, implementation, and synergy with metallic compounds for supercapacitor and battery electrodes. J. Power Sources 617, 235140 (2024).

Pampel, J. & Fellinger, T. Opening of bottleneck pores for the improvement of nitrogen doped carbon electrocatalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502389 (2016).

Sevilla, M., Ferrero, G. A. & Fuertes, A. B. Beyond KOH activation for the synthesis of superactivated carbons from hydrochar. Carbon 114, 50–58 (2017).

Mora, E., Blanco, C., Pajares, J. A., Santamaría, R. & Menéndez, R. Chemical activation of carbon mesophase pitches. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 298, 341–347 (2006).

Sangtong, N. et al. Ultrahigh-surface-area activated biocarbon based on biomass residue as a supercapacitor electrode material: tuning pore structure using alkalis with different atom sizes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 326, 111383 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Self-templated synthesis of interconnected porous carbon nanosheets with controllable pore size: Mechanism and electrochemical capacitor application. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 261, 119–125 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Beyond conventional carbon activation: Creating porosity without etching using cesium effect. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311655 (2024).

Li, J. et al. When high-temperature cesium chemistry meets self-templating: metal acetates as building blocks of unusual highly porous carbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217808 (2023).

Zhang, W., Li, W. & Li, S. Self-template activated carbons for aqueous supercapacitors. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 36, e00582 (2023).

Jayaramulu, K. et al. Ultrathin hierarchical porous carbon nanosheets for high-performance supercapacitors and redox electrolyte energy storage. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705789 (2018).

Dubal, D. P. et al. Metal–organic framework (MOF) derived electrodes with robust and fast lithium storage for Li-ion hybrid capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900532 (2019).

Fromm, K. M. Coordination polymer networks with s-block metal ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 856–885 (2008).

Banerjee, D. & Parise, J. B. Recent advances in s-block metal carboxylate networks. Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 4704–4720 (2011).

Alnaqbi, M. A. et al. Chemistry and applications of s-block metal–organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 3828–3854 (2021).

Nedelko, N. et al. Supramolecular control over molecular magnetic materials: γ-cyclodextrin-templated grid of cobalt(II) single-ion magnets. Inorg. Chem. 53, 12870–12876 (2014).

Terlecki, M., Justyniak, I., Leszczyński, M. K. & Lewiński, J. Effect of the proximal secondary sphere on the self-assembly of tetrahedral zinc-oxo clusters. Commun. Chem. 4, 133 (2021).

Prochowicz, D. et al. Construction of a porous homochiral coordination polymer with two types of CunIn alternating units linked by quinine: a solvothermal and a mechanochemical approach. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7367–7371 (2012).

Justyniak, I. et al. Toward coordination polymers based on fine-tunable group 13 organometallic phthalates. Inorg. Chem. 53, 7270–7275 (2014).

Lewiński, J. et al. From discrete linear Zn t bu 2 molecules to 1D coordination polymers and 2D fabrics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 3096–3098 (2007).

Leszczyński, M. K., Justyniak, I., Gontarczyk, K. & Lewiński, J. Solvent templating and structural dynamics of fluorinated 2D Cu-carboxylate MOFs derived from the diffusion-controlled process. Inorg. Chem. 59, 4389–4396 (2020).

Leszczyński, M. K. et al. Straightforward synthesis of single-crystalline and redox-active cr(II)-carboxylate MOFs. Inorg. Chem. 57, 4803–4806 (2018).

Leszczyński, M. K., Niepiekło, K., Terlecki, M., Justyniak, I. & Lewiński, J. Chromium(II)-isophthalate 2D MOF with redox-tailorable gas adsorption selectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 45100–45106 (2024).

Nawrocki, J. et al. Development of an SBU-based mechanochemical approach for drug-loaded MOFs. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 796–800 (2020).

Prochowicz, D., Nawrocki, J., Terlecki, M., Marynowski, W. & Lewiński, J. Facile mechanosynthesis of the archetypal zn-based metal–organic frameworks. Inorg. Chem. 57, 13437–13442 (2018).

Prochowicz, D. et al. A mechanochemical strategy for IRMOF assembly based on pre-designed oxo-zinc precursors. Chem. Commun. 51, 4032–4035 (2015).

Leszczyński, M. K., Justyniak, I. & Lewinski, J. Mechanochemistry Unlocking Stoichiometric Control in Alkali Metal Carboxylate Coordination Polymers. Dalton Trans. 10.1039.D5DT01954K https://doi.org/10.1039/D5DT01954K (2025).

Prochowicz, D., Saski, M., Yadav, P., Grätzel, M. & Lewiński, J. Mechanoperovskites for photovoltaic applications: preparation, characterization, and device fabrication. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 3233–3243 (2019).

Chavan, R. D. et al. Organic ligand-free ZnO quantum dots for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205909 (2022).

Runjhun, R. et al. High-performance perovskite solar cells with zwitterion-capped-ZnO quantum dots as electron transport layer and NH4 X (X = F, Cl, Br) assisted interfacial engineering. Energy Environ. Mater. e12720 https://doi.org/10.1002/eem2.12720.(2024).

Buyukcakir, O. et al. Ultralong-life quinone-based porous organic polymer cathode for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 7672–7680 (2023).

Rybarczyk, M. K., Cysewska, K., Yuksel, R. & Lieder, M. Microporous N-doped carbon obtained from salt melt pyrolysis of chitosan toward supercapacitor and oxygen reduction catalysts. Nanomaterials 12, 1162 (2022).

Cheng, P.-C. et al. Synthesis, structures and electrochemical properties of lithium 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate complexes. Polymers 11, 126 (2019).

Senthil, R. A., Osman, S., Pan, J., Liu, X. & Wu, Y. Recent progress on porous carbon derived from Zn and Al based metal-organic frameworks as advanced materials for supercapacitor applications. J. Energy Storage 44, 103263 (2021).

Yue, M. et al. Six isomorphous window-beam MOFs: Explore the effects of metal ions on MOF-derived carbon for supercapacitors. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 16160–16169 (2018).

Li, T., Ma, S., Yang, H. & Xu, Z. Preparation of carbonized MOF/MgCl2 hybrid products as dye adsorbent and supercapacitor: Morphology evolution and Mg salt effect. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 1601–1612 (2019).

Shahzadi, S., Akhtar, M., Arshad, M., Ijaz, M. H. & Janjua, M. R. S. A. A review on synthesis of MOF-derived carbon composites: innovations in electrochemical, environmental and electrocatalytic technologies. RSC Adv. 14, 27575–27607 (2024).

Wang, J., Wang, Y., Hu, H., Yang, Q. & Cai, J. From metal–organic frameworks to porous carbon materials: recent progress and prospects from energy and environmental perspectives. Nanoscale 12, 4238–4268 (2020).

Yang, I., Kim, S.-G., Kwon, S. H., Kim, M.-S. & Jung, J. C. Relationships between pore size and charge transfer resistance of carbon aerogels for organic electric double-layer capacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 223, 21–30 (2017).

Uke, S. J., Mardikar, S. P., Bambole, D. R., Kumar, Y. & Chaudhari, G. N. Sol-gel citrate synthesized Zn doped MgFe2O4 nanocrystals: a promising supercapacitor electrode material. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 3, 446–455 (2020).

Forouzandeh, P., Kumaravel, V. & Pillai, S. C. Electrode materials for supercapacitors: a review of recent advances. Catalysts 10, 969 (2020).

Smoliński, M. et al. From by-product of the petrol gasification to carbon black in lithium-ion batteries – Novel electron-conductive agents. Appl. Phys. A 131, 233 (2025).

Panić, V. V., Stevanović, R. M., Jovanović, V. M. & Dekanski, A. B. Electrochemical and capacitive properties of thin-layer carbon black electrodes. J. Power Sources 181, 186–192 (2008).

Nasibi, M., Golozar, M. A. & Rashed, G. Nanoporous carbon black particles as an electrode material for electrochemical double layer capacitors. Mater. Lett. 91, 323–325 (2013).

Brezesinski, T., Wang, J., Tolbert, S. H. & Dunn, B. Ordered mesoporous α-MoO3 with iso-oriented nanocrystalline walls for thin-film pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 9, 146–151 (2010).

Yin, J. et al. Electrochemical zinc ion capacitors enhanced by redox reactions of porous carbon cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001705 (2020).

Jia, X., Liu, C., Neale, Z. G., Yang, J. & Cao, G. Active materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries: synthesis, crystal structure, morphology, and electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 120, 7795–7866 (2020).

Agilent Technologies. CrysAlisPro. CrysAlisPro Version 1.171.35.21b.

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 64, 112–122 (2008).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Farrugia, L. J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: an update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 45, 849–854 (2012).

Yuksel, R. et al. Necklace-like nitrogen-doped tubular carbon 3D frameworks for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1909725 (2020).

Diard, J.-P., Le Gorrec, B. & Montella, C. Linear diffusion impedance. General expression and applications. J. Electroanal. Chem. 471, 126–131 (1999).

Bisquert, J. & Compte, A. Theory of the electrochemical impedance of anomalous diffusion. J. Electroanal. Chem. 499, 112–120 (2001).

Zhang, Z. et al. Further studies of a zinc-air cell employing a Zn-PCH (PVA chemical hydrogel) anode. J. Solid State Electrochem. 22, 3775–3783 (2018).

Giménez-Romero, D., Garcı́a-Jareño, J. J. & Vicente, F. Analysis of an impedance function of zinc anodic dissolution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 572, 235–247 (2004).

Diard, J.-P., Landaud, P., Le Gorrec, B. & Montella, C. Calculation, simulation and interpretation of electrochemical impedance. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 255, 1–20 (1988).

Leszczyński, M. et al. Functional porous carbon materials for energy storage applications engineered using novel alkali metal-based coordination network precursors. RepOD https://doi.org/10.18150/ET8JPX (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support by the ENERGYTECH-1 project granted by Warsaw University of Technology under the programme Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the National Science Centre, Poland, Grant OPUS 2021/41/B/ST5/04450, for financial support. Research was also funded by the Warsaw University of Technology within the Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB) programme based on agreement nr 1820/95/Z01/2023 of 03.04.2023. The authors would also like to thank prof. Grażyna Zofia Żukowska for her help in the Raman spectroscopy study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Michał K. Leszczyński: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Maria K. Kochaniec: Investigation, Methodology, Visualisation, Writing – review & editing; Michał Terlecki: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Iwona Justyniak: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Selay Aydın Sahin: Investigation, Busra Aydogdu: Investigation, Recep Yuksel: Investigation, Visualisation, Writing – review & editing; Maciej Siekierski: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Marcin Hołdyński: Investigation, Writing – review & editing; Władysław Wieczorek: Project administration, Resources, Supervision; Janusz Lewiński: Conceptualisation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leszczyński, M.K., Kochaniec, M.K., Terlecki, M. et al. Functional porous carbons derived from alkali metal-based coordination polymers for energy storage. Commun Mater 7, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01022-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01022-8