Abstract

Refractory ceramic materials are critical for applications in extreme high-temperature environments. Refractory high-entropy ceramics belong to this class of materials and show great potential due to their remarkable combination of properties. Traditionally, increasing compositional complexity and chemical diversity of high-entropy ceramics whilst maintaining a stable single-phase solid solution has been a primary design strategy for developing new ceramics. Here, we unveil an alternative strategy based on deviation from conventional equimolar composition towards non-equimolar composition space, enabling tuning the metastability level of the supersaturated single-phase solid solution. By employing high-temperature micromechanical testing and post-mortem microstructural characterization of refractory metal-based high-entropy nitrides, we observed the activation of an additional strengthening mechanism upon spinodal decomposition of the metastable phase into coherent cubic-phase domains exhibiting compositional modulation. This process propels the yield strength of a non-equimolar nitride at 1000 °C to a staggering 6.9 GPa, that is 43% higher than the most robust equimolar nitride.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Refractory metal-based nitrides belong to the broad family of refractory ceramic materials (a set of carbides, nitrides, and borides of the group IV and V transition metals): because of their ultra-high melting temperatures (Tm above ∼3000 °C) and phase stability they represent the only suitable class of materials available for a diverse range of mechanically loaded applications where components or tools are subjected to the most extreme of operating environments1,2. Delving into high-entropy ceramics3, the number of possibilities for exploring refractory nitrides is much greater. In such multi-component systems composed of at least five principal unary ceramic compounds, a high configurational entropy (set here by a disordered multi-cation sublattice—assuming that the anion sublattice remains intact) is expected to produce a preference for single-phase solid solutions with simple crystal structures. The presence of many chemically distinct atoms on the metal sublattice produces attractive effects, such as sluggish diffusion and considerable lattice distortion, amongst others4, leading to properties often highly surpassing those of the constituent conventional ceramic components3,5,6,7. However, although many studies focus on maximizing configurational entropy (using equimolar ratios of metal elements), indeed successfully achieving stabilization of single-phase solid solution in high-entropy oxides8, the impact of configurational entropy on the solid solution phase stability may have been overestimated in metallic alloys9,10,11 and nitrides12,13—configurational entropy may not even be a vital parameter for the design of multi-component alloys and ceramics with superior properties14,15 (Supplementary Note 1). The vast composition space of metastable non-equiatomic high-entropy ceramics instead provides even more ways for exploration of new ceramics featuring complex phase transformation sequences upon metastable phase decomposition16.

High-temperature mechanical properties are crucial for the operation of ceramics in extreme environments17, yet have been rarely studied thus far in high-entropy ceramics18. Although the unique mechanical properties of high-entropy ceramics are foremost determined by solid solution strengthening, among other beneficial mechanisms (see Supplementary Note 2), less attention has been placed on the stability of this mechanism at high temperatures, limiting the potential impact of these materials in applications. Seminal and relatively limited literature reports show that although mechanical properties of high-entropy ceramics are enhanced in comparison to conventional ceramic compounds19, they often deteriorate with increasing temperature20,21,22. This degradation is attributed to the weakening of strengthening mechanisms, which are effective primarily at low temperatures. As an alternative approach, we propose that engineering the metastability of high-entropy phases can guide the design of novel ceramic materials for high-temperature applications. Inherent metastability of multi-component nitrides12, in turn, can trigger different strengthening mechanisms upon single-phase solid solution decomposition, particularly when exposed to mechanical and thermal loads, leading to their higher strength and damage tolerance. Such a design strategy has demonstrated great success in developing high-entropy dual-phase alloys that overcome the strength–ductility trade-off23,24. The remarkable improvement of mechanical properties of conventional nitrides due to the formation of three-dimensional nanostructure25 or precipitation of two-dimensional atomic-plane-thick Guinier–Preston (GP) zones26 upon decomposition of single-phase solid solutions in conventional nitrides are proofs of the concept of metastability tuning in high-entropy nitrides.

Here, we demonstrate that tuning the metastability of high-entropy nitride ceramic thin films by deviating from equimolar metal ratios toward non-equimolar composition space allows for decreasing the stability of the solid solution, thus enabling its decomposition at elevated temperature. This entails two key benefits: coherency strain strengthening due to dual-phase isostructural nanodomains formed upon spinodal decomposition of the solid solution and retained solid solution hardening of the high-entropy nitride phase. This combination leads to good retention of high strength at elevated temperatures. At the same time, we show that maximization of configurational entropy and chemical diversity in equimolar high-entropy nitrides does not maintain high strength at elevated temperatures. Due to the relatively greater stability of all equimolar high-entropy nitrides at high temperatures, strength-inducing phase transformations are absent or insufficient to retain high yield strength in the studied temperature range.

Results

Microstructure and composition

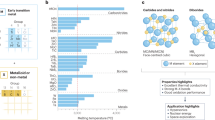

Refractory-metal-based pentanary (TiHfNbVZr)N, hexanary (TiHfNbVZrTa)N, and heptanary (TiHfNbVZrTaW)N thin films are grown by direct current magnetron sputtering (DCMS) in an industrial deposition system on (0001) single crystalline sapphire substrates; low and high additions of Al to the pentanary system are enabled by a hybrid co-sputtering process based on high-power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS) and DCMS. All as-deposited films are single-phase, B1-NaCl-structured solid solutions (Fig. 1A), as revealed by XRD analysis (Fig. 1B). The relative positions of XRD peaks vary among the samples due to composition-dependent differences in lattice constants. Using the hybrid method, we grew 6 µm-thick films exhibiting dense columnar microstructures (Fig. 1C) and mixed polycrystalline orientations (demonstrated in our previous report27) for further fabrication of micropillars using FIB (Fig. 1D). The fraction of metal elements on the cation sublattice was determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and time-of-flight elastic recoil detection analysis (ToF-ERDA): pentanary (Ti0.23Hf0.15Nb0.17V0.21Zr0.24)N, hexanary (Ti0.23Hf0.15Nb0.13V0.14Zr0.21Ta0.14)N, heptanary (Ti0.17Hf0.11Nb0.14V0.14Zr0.16Ta0.11W0.17)N, hexanary ‘Al-low’ (Ti0.21Hf0.13Nb0.14V0.18Zr0.20Al0.14)N and hexanary ‘Al-high’ (Ti0.13Hf0.07Nb0.07V0.10Zr0.12Al0.51)N, see Supplementary Table 1. Similarly, the anion sublattice is almost fully occupied with N, with a low amount of vacancies; more details about the microstructure and elemental composition of the as-deposited films are given in our previous report27. A representative energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping for hexanary ‘Al-high’ (Ti0.13Hf0.07Nb0.07V0.10Zr0.12Al0.51)N (Fig. 1E) shows a uniform elemental distribution across the thickness of the film for all elements. No signs of segregation, clustering, or phase separation are evident implying a homogeneous distribution of all elements and their random distribution on the metal lattice sites.

A Schematic representation of an ideal lattice structure of conventional B1-NaCl-structured refractory nitrides and a disordered lattice structure of a refractory-metal-based high-entropy nitride. B X-ray diffraction patterns of the as-deposited refractory-metal-based high-entropy nitride films contain only reflection from (111) and (200) planes of a NaCl-structure phase, indicating a single NaCl-structured solid-solution phase. C Cross-sectional SEM image of representative thin film showing columnar microstructure. D SEM image of a representative set of FIB-milled micro-pillars fabricated for high-temperature microcompression, viewed at 45° tilt angle, and a high-magnification SEM image of a selected pillar as an inset. E A representative EDS mapping for hexanary ‘Al-high’ (Ti0.13Hf0.07Nb0.07V0.10Zr0.12Al0.51)N demonstrating homogenous and random distribution of all elements in a large length scale. Scale bars in (C) is 1 µm; in (D) it is 10 µm (500 nm in the inset) and in (E) – 100 nm.

Phase stability and hardness evolution after annealing

Annealing in vacuum show that all nitrides with equimolar metal ratios retain the single-phase structure upon annealing up to ∼1000–1200 °C, demonstrating XRD patterns with peaks corresponding to the B1-NaCl-type phase structure, with low-intensity broad shoulders to (111) and (200) peaks developing upon annealing (Supplementary Fig. 1). Annealing at any higher temperature results in the oxidation of the thin film surface (as evident for heptanary thin films after annealing at 1200 °C), making assessing high-entropy nitride hardness by nanoindentation impossible. However, the hexanary Al-high single-phase solid solution undergoes decomposition at 900 °C already, evident as strong left- and right-hand shoulders to the (111) and (200) peaks, see Fig. 2A; this indicates the formation of additional B1-NaCl phases with a slight difference in lattice parameters compared to the original (matrix) phase. XRD patterns showing this for two critical representative compositions are shown in Fig. 2A, B, while the remainder of the cases are given in Supplementary Fig. 1. Apart from shoulder formation, a distinct shift of the main (111) and (002) peaks can be observed. While this peak shift may initially result from defect annihilation and associated stress relaxation, it is primarily driven by the continuous diffusion of Al out of the matrix phase at higher annealing temperatures. As the smallest cation leaves the matrix, lattice expansion occurs, leading to a shift of the peaks toward lower Bragg angles. This behavior contrast with that of heptanary (Ti0.17Hf0.11Nb0.14V0.14Zr0.16Ta0.11W0.17)N thin films, which exhibit greater stability with respect to cation outward diffusion, showing no detectable any peak shifts up to Ts = 1200 °C (Fig. 2B). Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations of formation energy for the pentanary system and hexanary system with different fractions of Al on the metal sublattice predicts all compositions to be metastable against decomposition to binary or ternary compounds (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the decomposition driving force increases as a function of Al fraction. All above confirms the targeted stability trend can be realized by designing a specific composition of the nitrides, which is in agreement with DFT calculations—without yet considering the kinetics of the decomposition process that can be significantly altered by Al content or upon the onset of decomposition. Evaluation of the films by nanoindentation after anneals above the deposition temperature aimed to capture changes in the resistance to room temperature crystal plasticity mechanisms resulting from eventual microstructural changes. This revealed, Fig. 2D, good retention of as-deposited hardness up to at least 1100 °C in all systems and retention of Young’s modulus (Supplementary Table 2) up to at least 1200 °C in all systems, with a minor (<10%) improvement in hardness seen in the refractory pentanary and hexanary nitrides. However, the Al-high and heptanary systems showed even greater improvement with highest hardness after annealing at 1000 °C (42.6 ± 2.3 GPa) and 1100 °C (44.6 ± 1.9 GPa), respectively. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) of the highest hardness conditions is carried out to understand the microstructural evolution generating such performance improvements—the as-deposited conditions have been previously characterized and reported in ref. 27. Whilst the pentanary nitride annealed at 1000 °C displays an unchanged columnar microstructure common to many sputter-deposited hard coatings28, Supplementary Fig. 2a, local chemical segregation across the metal sublattice is evidenced by atomic resolution high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) imaging, Fig. 3A. The heptanary nitride annealed at 1100 °C exhibits grain-scale segregation, in particular of W (Supplementary Figs. 2b, 3), a considerable density of grown-in twin boundaries, Fig. 3B, as well as atomic-scale segregation inside the grain, Fig. 3B insert, but no evidence of W-rich Guinier–Preston zones previously reported for W-doped ternary nitride (Ti,Al,W)N26. Finally, both Al-containing nitrides displayed significant nano-scale chemical segregation after annealing at 1200 °C, Fig. 3C–F and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, despite the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns showing only reflections matching the B1-NaCl structure phase (Supplementary Fig. 6). EDS mapping (Supplementary Fig. 5) and EDS line scans (Supplementary Fig. 7, Fig. 3D, F inserts) reveal the separation of all refractory metals from Al between the two contrasting isostructural domains with a modulation wavelength of the order 3.5 ± 0.4 nm for hexanary ‘Al-low’ and 12.2 ± 2.2 nm hexanary ‘Al-high’ films. Such decomposition of supersaturated solid solution into coherent cubic nanodomains via spinodal mechanism is typical for Al-containing refractory metal nitrides25. The non-equimolar solid solution decomposes at elevated temperature due to the high thermodynamic driving force to decomposition (Fig. 2C) while all equimolar solid solutions are relatively more stable (see XRD above, Fig. 2A, B, Supplementary Fig. 1).

XRD patterns for A hexanary ‘Al-high’ (Ti0.13Hf0.07Nb0.07V0.10Zr0.12Al0.51)N and B heptanary (Ti0.17Hf0.11Nb0.14V0.14Zr0.16Ta0.11W0.17)N thin films before and after annealing in vacuum at 900, 1000, 1100, 1200, 1300, 1400 °C. C Calculated Gibbs formation energies, ΔGf (x,T), of B1-NaCl structured pentanary system and hexanary system with varying Al fractions, shown as a function of temperature. ΔGf for systems with metal ratios on the cation sublattice similar to experimental samples is calculated relative to competing decomposition products taken as either binary nitrides (solid lines, full symbols) or ternary nitrides (dashed line, empty symbols). The decomposition potential, i.e., decomposition driving force, is determined as the energy difference between the Gibbs formation energies obtained with these two sets of reference phases; arrows with rotated labels give this decomposition potential for each composition in eV/atom, at 0 K. The thermodynamic decomposition driving force increases with Al content in the solid solution. This trend suggests that the solid solutions with higher Al content possess the highest driving force for the decomposition into less complex phases or solid solutions, even at high temperatures. D Nanoindentation hardness of all films performed before and after annealing in a vacuum at different temperatures of 900–1200 °C.

A Cross-sectional STEM-HAADF acquired along [110] zone axis from pentanary nitride annealed at 1000 °C and B heptanary nitride annealed at 1100 °C. Cross-sectional STEM-HAADF images taken along [110] zone axis and STEM-EDS color-coded combined maps of Ti-Al acquired from C, D the hexanary ‘Al-low’ and E, F hexanary ‘Al-high’ films after annealing at 1200 °C. Red dashed lines show the borders of the high contrast (high atomic number, Z) areas, and red dashed circles mark the local chemical segregation across the metal sublattice enlarged in the upper right insets in (A–C). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns of (A–C, E) are presented in bottom right inserts. Scale bars in (A–C, E) are 2 nm; in (D) it is 10 nm and in (F) – 20 nm.

High-temperature microcompression is carried out to capture mechanical performance and assess the effectiveness of these nitride microstructure strategies in conditions approximating extreme applications. Micro-pillars ∼1.8 μm in diameter, Supplementary Fig. 8, produced by focused ion beam (FIB) milling, where the height is less than the coating thickness, are compressed in vacuo in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at six temperatures, changing from the room temperature (∼25 °C) to 1000 °C, using a flat conductive diamond punch. The micro-pillar failure is classified as ductile or brittle. We use the yield strength or ultimate strength, determined using a 1% strain offset criterion (σy and σu, respectively), to characterize these behaviors. The failure mode is identified by inspecting the stress-strain curves and post-mortem SEM images of the pillars (Supplementary Fig. 9). Brittle failure, characterized by σu, corresponds to pillars exhibiting climb-and-crash stress-strain curves (sudden or progressive) after the initial stress maximum. In contrast, ductile failure, characterized by σy, corresponds to pillars that do not show a sudden crash in the stress-strain curves after the initial stress maximum. Compressive yield strengths and ultimate strengths determined using a 1% strain offset criterion, σy and σu, respectively, Fig. 4A, indicate initially greater room temperature strength of the pentanary and hexanary Al-high systems (σu ~ 11–12 GPa), while all other equimolar systems have σu ~ 8–9 GPa. Nevertheless, all such pillars fail by catastrophic brittle fracture; this is seen in stress-strain curves, Fig. 4B, and post-mortem SEM images, see Supplementary Fig. 9, which also include all other test temperatures. In the 500–800 °C range, all systems are softer than at 25 °C, yet broadly show strength stability across this range, with the pentanary nitride showing the most significant strength loss from 25 °C, to match the other equimolar systems in this temperature range closely. Deformability, through cohesive plasticity, over several percent strain, is now observed before eventual cracking-induced rapid strength loss. However, the hexanary Al-high system has at least 32% higher strength in this range. From 800 to 1000 °C, the best-performing system among equimolar compositions is the pentanary high-entropy nitride, whilst the heptanary and hexanary Al-low systems show the most rapid decrease of σy with temperature. Again, the non-equimolar Al-high system demonstrates 42–43% higher σy in this range than the best-performing equimolar system, with σy = 6.9 ± 0.5 GPa at 1000 °C. Deformation above 900 °C is predominantly cohesive, with local buckling of the upper sections of the pillars or shear plane formation (see TEM below).

A Yield strength σy (full symbols) at 1% strain offset and ultimate strength σu (open symbols) at 1% strain offset measured at different temperatures and B corresponding representative stress-strain curves for Al-high pillars compressed at RT, 500 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C, 900 °C, and 1000 °C. For statistical accuracy, at least 4–5 pillars are compressed for each film composition at each test temperature, but only representative stress-strain curves are shown here. To account for initially more compliant contact due to locally variable surface roughness of the real coatings, the loading curves have been shifted along the abscissa to intersect the linear elastic region with the origin for simpler strain-offset yield stress extraction.

High-temperature strength

It can be seen from the exemplary microcompression loading curves for hexanary ‘Al-high’ pillars in Fig. 4B and the complete set of material systems and test temperatures in Supplementary Fig. 10, that there is a noticeable reduction in measured elastic loading modulus, from either 800 or 900 °C depending on composition, with 1000 °C showing the lowest modulus. This could be associated with chemical reactivity between pillar and punch producing additional interface reaction phases, as well as plastic deformation of the diamond itself, as detailed in Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Figs. 11–15. Despite this, we consider the yield points of the loading curves to remain sufficiently distinctive for useful interpretation.

TEM imaging and analysis following microcompression at 1000 °C revealed the spinodally decomposed microstructure in the Al-rich hexanary nitride is retained as previously in the annealed film, Fig. 5, with a modulation wavelength ~10 nm, and preferential alignment of the Al-rich nanodomains along the film growth direction – i.e., the [001] axis, considering the predominant (002) film texture here. The bending-over of the Al-rich and refractory-metal-rich nanodomains is evident from localized plastic buckling upon compression in the upper half of the pillar (Fig. 5A–C). Yet, the pillar remains dense: no evidence of cracking or decohesion of the columnar grains at boundaries is seen. Despite the high vacuum environment, multiple oxidation layers surround the Al-high hexanary nitride pillar compressed at 1000 °C: an inner (Ti, V)Ox, an intermediate ZrOx, and finally, an outer AlOx (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17). The AlOx outer oxide layer acts as an oxygen diffusion barrier, preventing oxygen inward diffusion29, hence avoiding grain boundary oxide decoration in the pillar bulk. In stark contrast, extensive oxygen inward diffusion is observed for the W-containing heptanary nitride, see Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Figs. 18, 19.

Overview cross-sectional A BF-TEM (red dotted line serves as a guide to buckling of the columnar grains) and B Z-contrast STEM image from the hexanary ‘Al-high’ pillar after compression at 1000 °C with corresponding SAED pattern as an inset, and electron and ion-deposited Pt protective straps (e-Pt & i-Pt, respect.) indicated. C EDS color-coded maps of Al and Ti acquired from the white square in B with insets demonstrating EDS maps with a higher magnification. EDS color-coded maps of D Ti-Al, E V, F Zr, G Hf, H Nb, I Al, J Ti, and K N. Scale bar in (A) and (B) is 1 µm, in (C) it is 200 nm (20 nm in the insets), and in (D)–(K) they are 20 nm.

Discussion

Deformation at room temperature remains brittle for all high-entropy nitride systems, but with a higher σy: lacking in effective dislocation plasticity because highly directional covalent bonding, the majority constituent of such nitrides30, leads to a high lattice resistance31. The high-entropy nitrides display initially ductile plasticity from 500 °C, which is consistent with expectation that thermal activation of bending and turning of interatomic bonds and annihilation of ion-induced point defects decrease the lattice resistance (Peierls stress) and activate the motion of dislocations in the 0.1–0.3 Tm range17. All test temperatures are within the latter range, considering the melting point of the studied high-entropy nitrides can be in the 3200–3400K32 range if predicted by the rule-of-mixture. Commonly in B1-NaCl structured refractory nitrides, thermalization of electrons into less localized and less directional metallic states leads to the activation of additional slip systems, now occurring also on {111} < 110>, in addition to {110} < 110>, thereby inducing additional ductility33,34. The microcompression trends in deformability and σy observed here are consistent with previous high-temperature mechanics work35 on simpler B1-NaCl structured multi-component nitrides, where characterization was limited to 500 °C—the exact compositions, equimolar or otherwise, not being reported therein hindering fruitful comparison.

Amongst the equimolar compositions, the pentanary system (Ti0.23Hf0.15Nb0.17V0.21Zr0.24)N is the strongest in microcompression over almost the entire temperature range from 25 to 1000 °C, particularly at the extremes. Strengthening in all equimolar cases can be attributed to the lattice resistance of the solid solution—consistently improved neither by greater chemical complexity nor by the addition of higher melting point nitride formers. The sluggish diffusion characteristic of multi-principle component alloys or high-entropy metal sub-lattice nitrides12, combined with a relatively low driving force for decomposition, means equimolar systems retain their single-phase structure. Hence, σy decreases at high temperatures, which is primarily associated with the decline of the lattice resistance and absence of other obstacles for dislocation motion17. An essential feature of the annealing study is that hardness increases in all the analyzed systems upon annealing above the deposition temperature (450 °C); this is surprising, as commonly hard coatings without an additional microstructural strengthening mechanism would hence lose the strength benefit of a high density of ion-bombardment-induced crystal defects formed during synthesis36. As no modification to the 100-nm-scale columnar grain structure upon annealing is evident, a potential strengthening effect needs to be attributed to chemical segregations at the atomic-scale and/or short-range ordering observed in the metal sub-lattice, Fig. 3A, which may alter local lattice resistance.

The case of the W-containing heptanary nitride is particularly thought-provoking, as the high nanohardness performance in the annealing study is not borne out in high-temperature microcompression. The Tabor factor, that is, hardness to yield strength ratio, at room temperature of 4.6 for the heptanary nitride is indicative of brittleness-limited behavior35—compared to the pentanary and hexanary Al-high nitrides, where cohesive plasticity carries a theoretical Tabor factor of ~337. This reflects a certain degree of deformability of the latter two even at room temperature, as observed elsewhere in chemically simpler nitrides35, compared with the brittleness of this heptanary nitride. It is also important to note the considerably longer thermal holds at each test temperature experienced by the thin films during microcompression testing, lasting 4 h at least, Supplementary Fig. 13, as compared with 10 min for the annealing study, which justifies oxidation-induced strength loss. Moreover, the prolonged time for diffusion in microcompression tests may favor annihilation of the ion-bombardment-induced point defects, which results in weakening of this strengthening effect, starting from 500 °C. On the other hand, the cause of hardness improvement between annealing at 1000 and 1100 °C remains unclear—only grain-scale W segregations (Supplementary Figs. 2b, 3) and suggestions of short-range ordering, Fig. 3B, are identified here. Surprisingly, the presence of grown-in twin boundaries distinguishes the W-containing heptanary system from the other equimolar compositions; twin boundaries are uncommon for many refractory nitrides due to high stacking fault energies34 and may contribute to high hardness. Since the system contains refractory metal nitrides with both low (NbN, VN, and TaN) and high (HfN, TiN, ZrN) stacking fault energies34, the presence of twins in this heptanary high-entropy nitride may be energetically favored38,39. Such twin boundaries may be further exploitable if better understood. Moreover, any possible deviations from ideal randomness, i.e. short-range ordering or clustering, at high annealing temperature can significantly alter the Peierls stress and related strengthening40.

The greatest relative hardness increase is, however, achieved by the hexanary Al-high system (Ti0.13Hf0.07Nb0.07V0.10Zr0.12Al0.51)N, which undergoes microstructural decomposition most rapidly – consistent with the higher thermodynamic driving force (Fig. 2A, C) compared with equimolar compositions. The observed XRD peak shoulders, compositional modulation, and retention of B1-NaCl structure are consistent with spinodal-type decomposition typical for Al-rich refractory metal nitrides41. Decomposition of the Al-high solid solution into isostructural (TiHfVNbZr)N- and AlN-rich coherent nanodomains results in spatially fluctuating strain fields between the domains due to the negligible difference in their lattice parameters42. These coherency strains can also be accommodated by partial dislocations, stacking faults, and misfit dislocation depending on the stage of decomposition43,44. Hence, its here-unmatched high-temperature strength is provided by coherency strain between decomposed nano-domains45 as well as solid solution strengthening of the spinodal phase with a composition part-way between the pentanary and hexanary Al-low nitrides. Stacking faults and partial dislocations should enable good ductility, and activate different slip systems, although the results presented here indicate that the pentanary nitride itself nevertheless presents equally cohesive room temperature plasticity. Preferential alignment of the spinodal dual-skeleton of percolating phases likely leads to additional strength retention along the growth direction at high temperature46. The hexanary ‘Al-low’ system also decomposes through this mechanism after annealing at 1200 °C, but the high-temperature strength up to 1000 °C of this system is in the range of all other equimolar systems—likely due to delayed onset of decomposition of the hexanary ‘Al-low’ compared to the ‘Al-high’ system, given the lower thermodynamic decomposition driving force (Fig. 2C).

Moreover, the high-temperature strength of the Al-high system can be explained by a larger amplitude of the composition modulation45 compared to the Al-low system (Fig. 3D, F, Supplementary Fig. 7). The hexanary ‘Al-low’ system, annealed 1200 °C, shows the highest hardness (Fig. 2D), implying that the transformation of c-AlN nanodomains into thermodynamically preferred yet softer hexagonal AlN is delayed in the Al-low system in comparison to the Al-high system12,47 as evident from XRD results (hexagonal AlN phase precipitation starts at 1300 °C in ‘Al-high’ films, Fig. 2A, and at 1400 °C in ‘Al-low’ films, Supplementary Fig. 1C). Such a trend in the evolution of microstructure and phase composition of the ‘Al-low’ system may provide a more beneficial strengthening effect as compared to the ‘Al-high’ condition, at temperatures above 1100 °C, Fig. 6A. A classical summative strengthening model of the shear modulus-normalized shear strength, τ/G, plotted component-wise in Fig. 6B for ‘Al-high’ system, features theoretical contributions from the solution-strengthened lattice, dislocation arrays, grain and test-piece sizes, coherency strains due to decomposition, as well as the less-understood short-range ordering48,49, all detailed further in Supplementary Note 5. It is worth nothing that this plot does not account a potential decrease of the Hall–Petch slope (k) as temperature increases, typically leading to reduced grain boundary strengthening. However, under first approximation, we neglect this contribution because under studied conditions the spinodal domains are coherent in the films and the grain size remains unchanged in all samples. The opportunity to offset thermal softening by forming decomposed isostructural phases with higher compositional segregation at a greater spatial length scale is demonstrated in Fig. 6B, which may be achievable through a tailored composition design strategy that aims for the optimal synthesis of metastable phases highly prone to decomposition at specific application temperatures.

A The schematics of strength evolution for all systems studied as a function of annealing temperature and related relative changes in constituent elemental composition and phase fractions. The black solid line represents the behavior of all equimolar refractory metal-based high-entropy nitrides, the red solid line represents the hexanary ‘Al-low’ system, and the green line stands for the hexanary ‘Al-high’ system. In (A), areas of circles represent the elemental compositions and phase proportions, where the fcc-NaCl structured cubic phase is denoted by circles and the hexagonal AlN phase is denoted by hexagons. The dashed lines show further hypothetical evolution of the strength and phase composition after annealing at temperatures beyond 1200 °C. Contributions to total shear strength τsum depicted in (B) for the hexanary ‘Al-high’ system are: lattice resistance τ*, solid solution strengthening of the metallic sub-lattice, τSS, Taylor (dislocation) hardening, τG, pillar-size strengthening, τS, grain-size strengthening, τh-p, short-range ordering, τsr, and spinodal decomposition, τsd. Δa5λ2 controls spinodal strengthening based on the lattice parameter change Δa across the decomposed phases with spatial wavelength, λ, whereby the axis limit here is the extreme of fcc-NaCl structured pure AlN grown to λ = 15 nm. The arrow in (B) highlights a route for effective use of microstructure control by spinodal decomposition to offset the thermal softening of the lattice resistance.

The excellent high-temperature strength-deformability combination of the ‘Al-high’ hexanary system, due to a synergy of several hardening mechanisms accessible upon decomposition of the solid solution via a spinodal mechanism and sufficient to deform the diamond punch itself (Supplementary Fig. 11), reflects its serious contendership as a next-generation ultrastrong high-temperature ceramics. A simple Tabor factor of 3 predicts a hot hardness of ~20 GPa at 1000 °C. It also highlights the experimental difficulty in investigating such high-entropy ceramics—only B4C has been suggested as mechanically superior at high temperatures so far50, yet it is unlikely to resolve the chemical reactivity issues. Given that high-entropy nitrides can be synthesized in a bulk form51, ceramic materials demonstrating such high-temperature properties can find a range of applications in extreme high-temperature environments beyond the field of hard protective coating1,2,18.

Conclusions

In summary, the current findings show that rather than focusing on equimolar compositions and single-phase formation and stabilization in high-entropy ceramics, the unexplored realm of non-equimolar composition space can offer a pathway to impressively tune phase metastability and related complex phase transformation sequences upon metastable phase decomposition to achieve different strengthening mechanisms at high temperatures. We show that the inherent metastability triggers the decomposition of the high-entropy nitride studied here via a spinodal mechanism. This results in a chemically modulated microstructure that generates coherency strains, which, combined with the lattice resistance of the resulting solid solution phase, lead to an ultrahigh yield strength at 1000 °C. Future technological developments in such high-entropy nitrides may aim to optimize the refractory metal chemistry for greater strength and microstructural stability beyond 1000 °C while retaining the benefits of the early decomposing solid solution bringing spinodally-modulated microstructure and oxidation resistance here and even exploit additional mechanisms such as high twin densities and atomic-scale segregations and re-arrangements. The strategy of metastability tuning demonstrated here for high-entropy nitrides may pave a route towards tailoring high-temperature mechanical properties in other high-entropy ceramics, like carbides, oxides, and borides. We anticipate that a mesmerizing world of ultrastrong high-temperature ceramic materials can be unraveled by delving into the metamorphosis of metastable high-entropy nitride phases, employing, amongst others, spinodal decomposition.

Methods

Thin film growth

Refractory-metal-based pentanary (TiHfNbVZr)N, hexanary (TiHfNbVZrTa)N, and heptanary (TiHfNbVZrTaW)N thin films are grown by direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering in an industrial CemeCon AG CC800/9 magnetron sputtering system. The hexanary Al-low and Al-rich (TiHfNbVZrAl)N are grown by a hybrid high-power impulse and DC magnetron co-sputtering HiPIMS/DCMS. The pentanary, hexanary, and heptanary films are grown at a floating potential of ~20 V. All films are deposited at a substrate temperature of 450 °C. The films are grown using Al, W, TiHfZrNbV and TiHfZrNbVTa targets. For the growth of Al-containing films, the compound targets are powered by a DC power supply, while the Al target is powered by a HiPIMS power supply. HiPIMS pulse length is set to 100 µs and the pulsing frequency is varied from 200 to 600 Hz at different HIPIMS power. This variation is implemented to obtain different Al content in the films while maintaining the target current density in the range 0.51–0.57 A/cm2. A pulsed substrate bias of −60 V is applied synchronously with the Al-HiPIMS pulses, using a pulse length of 100 µs and an offset of 30 µs, in order to act on the metal-rich portion of the ion flux arriving at the substrate. The films are grown with 6 μm thickness on (0001) single-crystalline sapphire substrates. See previous publication for details27.

Micro-pillar fabrication

The micro-pillars are produced with the equivalent diameter of ∼1.8 μm and the final taper angle not exceeding 3° by focused ion beam (FIB) milling in a Tescan Lyra 3 instrument. The micro-pillars are milled with heights of ∼4–4.5 μm to avoid sample/pillar penetration into the substrate during compression and to avoid pillar-on-pedestal effects.

Mechanical properties

Micro-pillar compression is performed in situ in a Zeiss DSM 962 scanning electron microscope (SEM, base pressure 1.3 × 10−3 Pa) using an Alemnis SEM indenter extensively modified for operation at temperatures up to 1000 °C, with pyrolytic graphite-on-pyrolytic boron nitride heaters to achieve independent heating of both sample and indenter52. The compression is performed using a 5 μm diameter diamond flat punch manufactured for high-temperature experiments by Synton-MDP. To minimize the effect of thermal drift during compression at elevated temperatures, matching the sample temperature and indenter temperature follows the procedure described elsewhere52 to ensure thermal equilibrium at contact, considering the impact of substantial mutual radiative heating above ~600 °C53. Initial tip temperature calibration is achieved by indentation of the molybdenum holder adjacent to a spot-welded reference thermocouple. The calibration of the compliance of the loading frame is performed at test temperatures by indentation of the (0001) single crystalline sapphire substrate material using a diamond Berkovich indenter, according to the method in ref. 54. To achieve stabilization of the system at high temperatures, the heating rate is set to 5 °C/min. Prior to the test, the holding time for complete equilibration of tip/sample temperature and the rest of the loading frame and sensors is set to ∼4–5 h at each test temperature—see Supplementary Fig. S13 for an exemplary heating schedule. For statistical accuracy, at least 4–5 pillars are compressed for each film composition at each test temperature. The compression is conducted at room temperature (RT), 500 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C, 900 °C, and 1000 °C, once the isothermal conditions for the sample and punch are achieved. The micro-pillars are compressed in displacement control mode with a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 at temperatures from RT to 900 °C and with a strain rate of 1 × 10−2 s−1 at 1000 °C for practical reasons. The temperature-dependent compliance of the sapphire substrate55,56 and the pillar geometry is considered by applying Sneddon’s and Zhang’s corrections57 during yield strength calculations using the associated MicroMechanics Data Analyzer (MMDA) software.

The NanoTester Vantage Alpha by Micro Materials, Ltd. (Wrexham, Wales) equipped with a diamond Berkovich probe is used to measure nanoindentation hardness H and reduced Young’s moduli for refractory-metal-based thin film nitrides. Depth sensing indentations are acquired with a constant load of 30 mN during a dwell period of 5 s, yielding indentation depths <10% of the film thicknesses. H values are calculated following the Oliver and Pharr rule, considering the elastic unloading part of the generated load-displacement curve. The standard deviation errors are extracted from the corresponding 20 indents (each separated by 25 µm within the boundaries of square grids).

Structural characterization

Film and micro-pillar cross-sectional lift-out for scanning and transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) are performed by FIB in a FEI Helios NanoLab G3 UC Dual Beam SEM/Ga+ FIB system. TEM investigations are performed using a probe-corrected Thermo Fisher Scientific Titan Themis 200 G3 operated at 200 kV. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) is acquired with the integrated SuperX detector. The annealing is performed in a vacuum with the heating rate of 10 °C/min to the annealing temperature Ta, which is in the range 900–1200 °C, and then kept at Ta for 10 min. Following anneals, the furnace is allowed to naturally cool to room temperature. The phase composition of the films before and after annealing is determined using Bragg-Brentano X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a PANalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer. To avoid reflections from the sapphire substrate, the XRD scans are recorded using a 1° offset along ω. The composition and stoichiometry of the films are determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and time-of-flight elastic recoil detection analysis (ToF-ERDA). More details about the measurements and analyses are given in the reference27.

Computational details

The formation enthalpy ΔHf for compositions (TiHfNbVZr)1-xAlxN was calculated as

where \({E}_{{tot}}({compound})\) is a total DFT energy of the B1-NaCl-structured solid solution modeled as quasi-randomly arranged atoms58, \({E}_{{tot}}^{i}\) is the total energies of the reference parent phases (binary or ternary decomposition products59), each weighted by the corresponding atomic fraction xi. DFT calculations were performed using the same level of approximations as in refs. 60,61: plane-wave cutoff Ecut = 650 eV, Brillouin zone k-point spacing is 0.5 Å−1, electronic convergence threshold 10−4 eV, and ionic relaxation until the forces were below 10−3 eV.

To account for temperature effects arising from configurational disorder, the Gibbs formation energy was approximated as:

where

is the ideal configurational entropy, assuming all cationic sites in B1-NaCl structure are equally accessible for all atomic species.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Wyatt, B. C., Nemani, S. K., Hilmas, G. E., Opila, E. J. & Anasori, B. Ultra-high temperature ceramics for extreme environments. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 773–789 (2023).

Eswarappa Prameela, S. et al. Materials for extreme environments. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 81–88 (2023).

Oses, C., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. High-entropy ceramics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 295–309 (2020).

Akrami, S., Edalati, P., Fuji, M. & Edalati, K. High-entropy ceramics: Review of principles, production and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. 146, 100644 (2021).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-019-0121-4 (2019).

Du, C. et al. Macro-superlubricity induced by tribocatalysis of high-entropy ceramics. Adv. Mater. 2413781, e2413781 (2024).

Wen, Z. et al. Exceptional oxidation resistance of high-entropy carbides up to 3600. C. Adv. Mater. 2507254, 1–10 (2025).

Rost, C. M. et al. Entropy-stabilized oxides. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–8 (2015).

Otto, F., Yang, Y., Bei, H. & George, E. P. Relative effects of enthalpy and entropy on the phase stability of equiatomic high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 61, 2628–2638 (2013).

Otto, F. et al. Decomposition of the single-phase high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi after prolonged anneals at intermediate temperatures. Acta Mater. 112, 40–52 (2016).

Santodonato, L. J. et al. Deviation from high-entropy configurations in the atomic distributions of a multi-principal-element alloy. Nat. Commun. 6, 5964 (2015).

Kretschmer, A. et al. Strain-stabilized Al-containing high-entropy sublattice nitrides. Acta Mater. 224, 117483 (2022).

Nayak, G. K., Kretschmer, A., Mayrhofer, P. H. & Holec, D. On correlations between local chemistry, distortions and kinetics in high entropy nitrides: an ab initio study. Acta Mater. 255, 118951 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Quatermetallic Pt-based ultrathin nanowires intensified by Rh enable highly active and robust electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation. Nano Energy 71, 104623 (2020).

Hossain, M. D. et al. Entropy landscaping of high-entropy carbides. Adv. Mater. 33, 1–11 (2021).

Raabe, D., Li, Z. & Ponge, D. Metastability alloy design. MRS Bull. 44, 266–272 (2019).

Wang, J. & Vandeperre, L. J. Deformation and hardness of UHTCs as a function of temperature. In Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics: Materials for Extreme Environment Applications 9781118700, 236–266 (Wiley, 2014).

Wang, F., Monteverde, F. & Cui, B. Will high-entropy carbides and borides be enabling materials for extreme environments? Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 5, 022002 (2023).

Feng, L., Chen, W. T., Fahrenholtz, W. G. & Hilmas, G. E. Strength of single-phase high-entropy carbide ceramics up to 2300. C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 104, 419–427 (2021).

Mayrhofer, P. H., Kirnbauer, A., Ertelthaler, P. & Koller, C. M. High-entropy ceramic thin films; A case study on transition metal diborides. Scr. Mater. 149, 93–97 (2018).

Kirnbauer, A. et al. Thermal stability and mechanical properties of sputtered (Hf,Ta,V,W,Zr)-diborides. Acta Mater. 200, 559–569 (2020).

Huang, P. & Yeh, J. Inhibition of grain coarsening up to 1000 ° C in (AlCrNbSiTiV) N superhard coatings. Scr. Mater. 62, 105–108 (2010).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016).

Huang, H. et al. Phase-transformation ductilization of brittle high-entropy alloys via metastability engineering. Adv. Mater. 1701678, 1–7 (2017).

Mayrhofer, P. H. et al. Self-organized nanostructures in the Ti-Al-N system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2049–2051 (2003).

Pshyk, O. V. et al. Discovery of Guinier-Preston zone hardening in refractory nitride ceramics. Acta Mater. 255, 119105 (2023).

Pshyk, A. V. et al. High-entropy transition metal nitride thin films alloyed with Al: microstructure, phase composition and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 219, 110798 (2022).

Mayrhofer, P. H., Clemens, H. & Fischer, F. D. Materials science-based guidelines to develop robust hard thin film materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 146, 101323 (2024).

Greczynski, G., Hultman, L. & Odén, M. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of Ti1-xAlxN (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.83) high-temperature oxidation: the crucial role of Al concentration. Surf. Coat. Technol. 374, 923–934 (2019).

Comprehensive Materials Processing (Elsevier, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2.

Materials Science of Carbides, Nitrides and Borides (Springer Science+Business Media, 1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4562-6.

The Chemistry of Transition Metal Carbides and Nitrides (Blackie Academic & Professional, 1996).

Hannink, R. H. J., Kohlstedt, D. L. & Murray, M. J. Slip system determination in cubic carbides by hardness anisotropy. Proc. R. Soc. A 326, 409–420 (1972).

Yu, H., Bahadori, M., Thompson, G. B. & Weinberger, C. R. Understanding dislocation slip in stoichiometric rocksalt transition metal carbides and nitrides. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 6235–6248 (2017).

Wheeler, J. M., Raghavan, R., Chawla, V., Morstein, M. & Michler, J. Deformation of hard coatings at elevated temperatures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 254, 382–387 (2014).

Schaffer, J. P., Perry, A. J. & Brunner, J. Defects in hard coatings studied by positron annihilation spectroscopy and x-ray diffraction. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 10, 193–207 (1992).

Vandeperre, L. J., Giuliani, F. & Clegg, W. J. Effect of elastic surface deformation on the relation between hardness and yield strength. J. Mater. Res. 19, 3704–3714 (2004).

Hugosson, H. W., Jansson, U., Johansson, B. & Eriksson, O. Restricting dislocation movement in transition metal carbides by phase stability tuning. Science 293, 2434–2437 (2001).

Xu, Z. et al. Insight into the structural evolution during TiN film growth via atomic resolution TEM. J. Alloy. Compd. 754, 257–267 (2018).

Wang, Y., Csanádi, T., Zhang, H., Dusza, J. & Reece, M. J. Enhanced hardness in high-entropy carbides through atomic randomness. Adv. Theory Simul. 2000111, 1–8 (2020).

Mayrhofer, P. H., Mitterer, C. & Clemens, H. Self-organized nanostructures in hard ceramic coatings. Adv. Eng. Mater. 7, 1071–1082 (2005).

Cahn, J. Hardening by spinodal decomposition. Acta Metall. 11, 1275–1282 (1963).

Salamania, J. et al. High-resolution STEM investigation of the role of dislocations during decomposition of Ti1-xAlxNy. Scr. Mater. 229, 115366 (2023).

Rafaja, D. et al. Crystallography of phase transitions in metastable titanium aluminium nitride nanocomposites. Surf. Coat. Technol. 257, 26–37 (2014).

Kato, M., Mori, T. & Schwartz, L. H. Hardening by spinodal modulated structure. Acta Metall. 28, 285–290 (1980).

Amberger, D., Eisenlohr, P. & Göken, M. On the importance of a connected hard-phase skeleton for the creep resistance of Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 60, 2277–2289 (2012).

Mayrhofer, P. H., Hultman, L., Schneider, J. M., Staron, P. & Clemens, H. Spinodal decomposition of cubic Ti 1 – x Al x N: Comparison between experiments and modeling. Int. J. Mat. Res. 98, 1054–1059 (2007).

Seol, J. B. et al. Short-range order strengthening in boron-doped high-entropy alloys for cryogenic applications. Acta Mater. 194, 366–377 (2020).

Schön, C. G. On short-range order strengthening and its role in high-entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 196, 113754 (2021).

Wheeler, J. M. & Michler, J. Invited article: Indenter materials for high temperature nanoindentation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84, 1–11 (2013).

Dippo, O. F., Mesgarzadeh, N., Harrington, T. J., Schrader, G. D. & Vecchio, K. S. Bulk high-entropy nitrides and carbonitrides. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Wheeler, J. M. & Michler, J. Elevated temperature, nano-mechanical testing in situ in the scanning electron microscope. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84, 045103 (2013).

Edwards, T. E. J. et al. Longitudinal twinning in a TiAl alloy at high temperature by in situ microcompression. Acta Mater. 148, 202–215 (2018).

Oliver, W. C. C. & Pharr, G. M. M. Improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 7, 1564–1580 (1992).

Schmid, F. & Harris, D. C. Effects of crystal orientation and temperature on the strength of sapphire. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 81, 885–893 (1998).

Wachtman, J. B. & Lam, D. G. Young’s modulus of various refractory materials as a function of temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 42, 254–260 (1959).

Zhang, H., Schuster, B. E., Wei, Q. & Ramesh, K. T. The design of accurate micro-compression experiments. Scr. Mater. 54, 181–186 (2006).

van de Walle, A. Multicomponent multisublattice alloys, nonconfigurational entropy and other additions to the Alloy Theoretic Automated Toolkit. Calphad 33, 266–278 (2009).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metalamorphous- semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Acknowledgements

AVP acknowledges the financial support from the National Science Centre of Poland (SONATINA 2 project, UMO-2018/28/C/ ST5/00476), the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP) under START scholarship (START 72.2020), and Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the Bekker Programme (PPN/BE K/2019/1/00146/U/00001). A.V. acknowledges the financial support from the National Science Centre of Poland (SONATINA 2 project, UMO-2018/28/C/ST5/00476). B.W. is grateful to the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange for support upon the NAWA Bekker (BPN/BEK/2021/1/00366/U/00001) and the Warsaw University of Technology within the Excellence Initiative: Research University, IDUB Mobility program (1820/74/Z09/2023). T.E.J.E. acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 840222. The contributions of Prof. G. Greczynski and Dr. B. Bakhit are also gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.V.P., P.K., B.W., P.S., and T.E.J.E. performed experiments and analyzed data. O.V.P. and T.E.J.E. wrote the original draft with contributions from all authors. A.V. performed DFT calculations. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and participated in review and editing of the article and approved its final version. O.V.P., J.M. and T.E.J.E. developed the concept and managed the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Koichi Tanaka and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pshyk, O.V., Vasylenko, A., Küttel, P. et al. Unlocking ultrastrong high-temperature ceramics via non-equimolar refractory metal high-entropy nitrides. Commun Mater 7, 35 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01047-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01047-z