Abstract

Single-photon emitters are essential components of emerging quantum technologies, including secure communication and quantum computing. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) have emerged as a promising platform for quantum light sources due to their quasi-one-dimensional excitonic host structure and compatibility with telecom photonic systems. Recent advances in deterministic defect engineering—most notably the development of organic color centers (OCCs)—have enabled stable, chemically controllable, and spectrally tunable single-photon emission. OCC-based emitters have demonstrated single-photon purity exceeding 99% and, more recently, room-temperature photon indistinguishability, placing them among the few solid-state systems with quantum-grade performance under ambient conditions. This review surveys progress in the field from three complementary perspectives: chemical synthesis and quantum defect engineering, computational studies of structure-property relationships and excitonic behavior, and experimental investigations of quantum optical properties. We also discuss alternative approaches, including air-suspended SWCNTs and hybrid van der Waals heterostructures, highlighting opportunities and open challenges for scalable integration into quantum photonic platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-photon sources are fundamental building blocks for next-generation quantum technologies, including secure quantum communication and quantum computing. The first single-photon source, demonstrated in 1986, was based on atomic transitions1, which require complex and bulky setups that limit scalability and integration into compact and scalable devices. To overcome these constraints, solid-state quantum emitters have been intensively investigated2. Platforms such as quantum dots3 and color centers in diamond4 have demonstrated single-photon emission, yet challenges persist regarding room-temperature operation, electrical excitation, and emission at telecom-relevant wavelengths (1.3–1.6 µm), which are crucial for compatibility with existing fiber-optic networks.

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) provide a unique quasi-one-dimensional host for excitonic states5. In pristine SWCNTs, each carbon atom is sp2 hybridized, forming three σ-bonds with neighboring carbon atoms and contributing one p-orbital perpendicular to the tube surface6,7,8. These p-orbitals overlap to create an extended π-bond network that supports delocalized electronic states and tightly bound excitons5,9. The electronic characteristics of SWCNTs—metallic or semiconducting—are governed by their chirality, defined by the (n, m) indices of the chiral vector6,10,11,12. Several techniques exist for the selective synthesis and enrichment of semiconducting SWCNTs13, which are particularly attractive as excitonic host materials due to their well-defined excitonic transitions and narrow-band photoluminescence (PL), despite intrinsically low PL quantum yields in pristine nanotubes14,15,16,17. Metallic SWCNTs, by contrast, do not contribute to PL and can introduce additional non-radiative decay pathways when present in mixed samples. In the context of quantum light sources, the primary role of SWCNTs is to serve as a one-dimensional scaffold on which excitons can be localized and engineered through defect formation. Accordingly, throughout this review, the term SWCNT refers exclusively to semiconducting nanotubes used as host materials for defect-based quantum emitters.

SWCNTs can be transformed into quantum emitters through exciton localization. In pristine semiconducting SWCNTs, the lowest-energy optical transition (E11) corresponds to a delocalized exciton that can diffuse over tens to hundreds of nanometers along the nanotube axis18. Introducing localized potential sites, either via intrinsic structural defects or controlled chemical modifications, can spatially confine these mobile excitons, effectively converting a one-dimensional system into zero-dimensional quantum emitters capable of SPE. The first experimental demonstration of SPE from SWCNTs was reported by Högele et al., who observed photon antibunching at cryogenic temperatures arising from naturally occurring exciton localization19. While this marked an important milestone, the randomness of exciton localization hindered reproducibility and spectral stability. Subsequent studies by Ma et al. and Ishii et al. demonstrated room-temperature antibunching based on exciton–exciton annihilation (EEA), an intrinsic nonlinear process in 1D systems, though with only moderate single-photon purity20,21.

To achieve deterministic exciton localization and higher single-photon purity, chemically engineered defect states have been developed. Early efforts using oxygen-based defects22 (e.g., epoxide, ether, hydroxyl) showed promise for SPE but suffered from poor control23,24. A significant breakthrough was achieved with the introduction of organic color centers (OCCs), first demonstrated by Piao et al., which are formed by creating paired sp3 defects within the sp2 carbon lattice of semiconducting SWCNTs and proposed as SPEs25. Importantly, OCC-based emitters have demonstrated exceptional quantum optical performance at ambient conditions, exhibiting single-photon purities exceeding 99%, as first shown by He et al.26, and photon indistinguishability at room temperature, most recently demonstrated by Husel et al.27.

Unlike conventional defects that typically act as non-radiative scattering centers, OCCs effectively introduce a localized quantum emitter embedded within the band structure of the semiconductor host. Mobile E11 excitons can be funneled into this lower-energy site, giving rise to stable, redshifted PL (commonly denoted E11* or \({E}_{11}^{-}\)) that is spectrally distinct from the native E11 emission28. The resulting emission spans the shortwave-infrared and the telecom bands (> 900 nm to ~1600 nm), making OCC-functionalized SWCNTs highly compatible with silicon-based photonic platforms29. Crucially, OCC formation can be engineered through controlled chemical reactions, building on the original defect-engineering framework introduced by Piao et al.25 and subsequent developments, providing access to tunable defect configurations and chemistry that are difficult to realize in inorganic defect systems28. Together, these features position OCC-functionalized SWCNTs as a compelling platform for scalable quantum light sources compatible with integrated photonic architectures28,30.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent progress in SWCNT-based SPEs, with a focus on controlled OCC engineering. We examine the formation and behavior of localized defect emitters through three complementary perspectives: (1) chemical synthesis strategies for defect creation and control, (2) computational studies that elucidate structure-property relationships and excitonic properties, and (3) experimental investigations of quantum optical measurements. In addition, we discuss alternative approaches to SPEs, including air-suspended SWCNTs and hybrid platforms based on van der Waals heterostructures, as well as advances in photonic integration and electroluminescence. Through this multidisciplinary review, we aim to highlight both the rapid progress and the remaining challenges toward practical SWCNT-based quantum light sources.

Chemistry of organic color centers

OCCs are created on SWCNT surfaces through covalent chemical functionalization, which converts sp2 carbons into localized sp3 quantum defects. First introduced via aryl diazonium chemistry by Piao et al.25, OCCs have since emerged as robust quantum emitters, acting as deep exciton traps that produce bright PL across the near-infrared to telecom bands. Their emission wavelength, brightness, and photostability can be tuned by the functional group chemistry, the chirality of the host nanotube, and, more subtly, the specific binding configuration within the sp2 carbon lattice28. A wide variety of covalent chemistries have been developed to expand the accessible quantum defects. For a broader overview of the chemistries, the readers are referred to Brozena et al.28, Shiraki et al.31, Zaumseil32, and Janas33.

This section highlights recent advances in chemistries that enable control over defect configuration/morphology, spatial patterning, and quantum emission properties. In the subsections that follow, we examine the molecular-level chemistry that governs these configurations, the resulting spectral features, and emerging strategies for precision control of defect formation.

Spectral diversity and binding configurations

A defining characteristic of OCCs is their spectral tunability, enabled by the chemically tunable covalent defects and their specific binding configurations on the carbon lattice. However, this tunability also introduces spectral heterogeneity, as different binding geometries, even for the same functional group, can produce a broad distribution of defect-induced PL wavelengths. Understanding and controlling this diversity is essential for developing OCCs as reproducible, high-precision quantum light sources.

Origin of spectral diversity

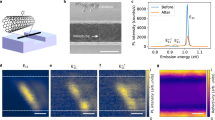

When an aryl group is covalently attached to a SWCNT, it generates a localized state that can trap excitons and induce red-shifted emission, typically labeled as the E11− or E11* transition (hereafter we use E11* as a general label for all red-shifted emissions). The position of the paired substituent—presumably a hydrogen, hydroxyl, or another aryl radical—can vary depending on which carbon atoms are involved34. Due to the hexagonal symmetry of the graphene lattice, there are six distinct divalent binding configurations within a single hexagonal ring, corresponding to ortho and para positions along different bond vectors relative to the tube axis (Fig. 1a)35,36. The computational basis for these defect configurations will be further discussed in the section “Computational studies of SWCNTs functionalized with molecular defects”.

a Schematic of main binding configurations for an OCC comprised of an aryl dopant and a pairing group. The gray circle indicates the position of the aryl functionalized carbon in the SWCNT sidewall. The blue and red markers denote the carbon bound to the pairing group for the different possible binding configurations, with the blue indicating the ortho positions (pairing group is on an adjacent carbon) and red indicates the para configurations (pairing group is across a benzene ring). The crosses mark the meta positions, which are energetically disfavored. Three ortho and para sites are further classified according to their bonding orientations, marked as L27 (square), L87 (triangle), and L− 33 (circle). As an example, a 4-bromobenzene group and a hydrogen atom bound to a (6,5) SWCNT are shown. The right plot shows oscillator strength and emission wavelength of the morphologies in (a). Dashed Gaussian curves show the inhomogeneous distribution expected for each transition. b Two-step chlorosulfonic acid-assisted creation of OCC. The SWCNTs are first dissolved in chlorosulfonic acid, along with an aniline derivative and sodium nitrite, and then added dropwise to an aqueous sodium deoxycholate solution. c UV light and strong base-mediated dual reaction pathway for configuration control. The UV light favors the creation of the higher energy E11* defect peak, while the potassium tert-butoxide favors the formation of the lower energy E11*− peak that is associated with a different binding configuration. d DNA-guided creation of highly ordered sp2 OCCs. The guanine base pair in DNA can be activated by singlet oxygen to form an sp2 defect on the SWCNT surface. By using a DNA sequence with a quinine pitch that matches its wrapping on the SWCNT surface, the defects can be patterned on the SWCNT surface in a highly ordered manner. e Laser-induced reconfiguration of OCCs. When irradiated with high-intensity light, the OCC can facilitate a shift in the relative binding configurations between the aryl group and the pairing group, allowing for the most thermally stable configuration to be achieved. Panel (a) adapted from He et al.35; Panel (b) adapted from Luo et al.38; Panel (c) adapted from Settele et al.42; Panel (d) adapted from Lin et al.48; Panel (e) adapted from Qu et al.56.

TD-DFT simulations confirm that these six configurations result in unique local potential wells with emission energies spanning more than 300 meV, and varying degrees of exciton localization and oscillator strengths35. This rich chemical diversity explains the broad and often multi-peaked PL spectra seen in ensemble samples. For example, functionalized (6,5) SWCNTs can emit across the 1000–1350 nm range, with OCC peak distributions attributed to specific ortho and para geometries35.

Host–defect decoupling and structure-property maps

Large-scale spectral studies show that while the emission energy of OCCs depends strongly on nanotube diameter, variations associated with chiral angle and mod(n-m,3) family are comparatively modest at the ensemble level. This suggests a degree of electronic decoupling between the trapped exciton and the 1D semiconductor host37. For instance, perfluorohexyl defects introduced into 14 different chiralities produced defect emissions tunable by nearly 400 meV, but with no systematic dependence on mod(n-m,3) classification when averaged across defect configurations37.

This observation suggests that OCCs behave like zero-dimensional emitters embedded in a one-dimensional scaffold, and their emission energy is determined by the electron-withdrawing strength and binding geometry of the attached moiety. Empirical fits to experimental datasets show that the energy shift (\(\Delta E\)) scales approximately with the inverse square of the nanotube diameter, while local dielectric environment and binding symmetry introduce secondary variations that contribute to spectral scatter37.

Symmetry-induced narrowing in zigzag nanotubes

Remarkably, the symmetry of SWCNTs can be exploited to suppress configurational diversity. In zigzag nanotubes (e.g., (11,0)), the high lattice symmetry renders all ortho or all para binding sites degenerate, leading to a collapse of the emission spectrum into a single dominant, narrow PL band. Saha et al. demonstrated that selective functionalization of (11,0) SWCNTs with 4-methoxybenzene produced OCC PL spanning only 25 meV across multiple tubes, nearly an order of magnitude narrower than that observed in lower-symmetry chiralities such as (6,5) or (10,3) samples36.

This symmetry-enabled narrowing highlights a promising pathway toward monochromatic, potentially indistinguishable SPEs by structurally selecting or enriching specific SWCNT chiralities with high-symmetry lattices. It also suggests that symmetry plays a key role in binding selectivity, complementing what is achievable through chemical control alone.

Synthetic access to specific binding configurations

While the rich spectral landscape of OCCs arises from multiple possible defect geometries, this diversity also poses a challenge for scalable quantum applications that require uniform emission properties. Recent advances in synthetic strategies now provide a set of tools to selectively favor specific binding configurations by controlling steric hindrance, reaction pathways, or lattice symmetry.

Steric and solvent-controlled defect pairing in superacid-mediated diazonium chemistry

A powerful strategy for controlling OCC formation involves a two-step diazonium reaction in superacids34,38. When SWCNTs are dissolved in chlorosulfonic acid, the aryl diazonium species, which are pre-formed or generated in situ from aniline and NaNO2, react with the nanotube to attach an aryl group. The system is then neutralized by the addition of water (Fig. 1b) or other solvents34,38.

Wang et al. further discovered that the pairing group is not introduced while in the superacid, but rather during the neutralization step, where it is provided by the solvent34. Unlike conventional diazonium reactions in aqueous media, which proceed via radical intermediates, this reaction is believed to follow a carbocation pathway. The carbocation forms on a carbon adjacent to the arylated site and reacts with a nucleophile from the quenching solvent to complete the OCC formation.

This mechanism allows for the deliberate tuning of the pairing group: water yields –OH; alcohols, such as methanol, ethanol, and isopropanol, yield –OCH3, –OC2H5, –OC3H7, and –i-OC3H7, respectively; and liquid ammonia yields –NH2. Each pairing group subtly modifies the electronic structure of the defect. For instance, OCCs with the –NH2 pairing group exhibit ∼20 meV less red-shift than those with oxygen-based groups, due to the electron-donating nature of amines34.

Steric control of binding configuration

The size of the aryl group and the pairing group play a critical role in determining the preferred binding configuration of an OCC. Through experimental hyperspectral PL imaging, Wang et al. showed that larger functional pairs shift the OCC spectral population to result in the dominance of defect emission (∼1240–1270 nm), which becomes the majority PL signal (~90%) in systems like 3F-SO3-Ar/i-OC3H7 (ref. 34). DFT modeling suggests that this shift is due to the para binding configurations becoming more energetically favorable than the ortho configuration for larger pairing groups, primarily because of an increase in steric repulsion. This effect has a much stronger impact on the ortho configuration compared to the para configuration. This steric control strategy not only enables spectral control across both NIR-II (900–1880 nm) and telecom (1260–1675 nm) bands but also improves uniformity in ensemble emission by reducing configurational heterogeneity.

These findings from superacid-mediated chemistry unlock a previously underexplored dimension of OCC design: independent control over the aryl and pairing group identities. The decoupling of these two steps, arylation and pairing, enables the orthogonal tuning of optical, steric, and electronic properties of OCCs.

Despite these advances, several open questions remain: Can this method be extended to less acidic or more biocompatible solvents while preserving control over binding configurations? Are additional Lewis-basic pairing groups, such as thiols or phosphines, accessible within this scheme to modulate exciton trap depths or introduce new spin-related properties? Can dual-defect architectures be created through sequential introduction of distinct aryl/pairing pairs?

Photochemical and chemically-triggered OCC creation

Alternative pathways to defect creation involve photoactivation or nucleophilic substitution, offering potentially orthogonal access to binding geometries.

Wu et al. demonstrated that UV light (335–365 nm) can drive radical formation in (6,5) SWCNTs from aryl iodides39 by photoexciting the SWCNT, which enables electron transfer to the aryl iodide. This photoinduced reduction causes the aryl iodide to dissociate into an iodide anion and an aryl radical, which subsequently reacts with the nanotube to generate OCCs. Zheng et al. extended this approach by using higher-energy UV light (280 nm) to directly excite non-halogenated aromatic systems in aqueous media, enabling defect formation from non-halogenated precursors40. Notably, when the dissolved oxygen was removed from the SWCNT solution by purging with argon prior to the UV irradiation, a strong E11*− (in this article we use E11*− as a general label for red-shifted emissions showing lower energy than E11*) emission peak emerged alongside the E11* peak typically observed under ambient air conditions, providing a means to tune the emission through atmospheric control.

An advantage of these photochemical approaches is their compatibility with air-suspended SWCNTs. Kozawa et al. showed that aryl iodides, due to their low vapor pressure, can diffuse in the gas phase and react with suspended nanotubes, enabling functionalization without liquid solvents41. The details of this novel approach will be further discussed in the section “Single photon emission from SWCNTs and OCCs-bearing SWCNTs”. By contrast, diazonium reactions generally require aqueous solvents to dissolve the diazonium salt, but water’s high surface tension disrupts the integrity of suspended SWCNTs, limiting their accessibility to solution-phase chemistry.

Beyond light activation, OCC precursors can be chemically triggered to produce reactive radicals that readily bond to the nanotubes and create OCCs. Settele et al. demonstrated that strong bases such as potassium tert-butoxide can also induce OCC formation in the absence of light42. This base-mediated pathway produces a different distribution of binding configurations than those formed by photochemistry, suggesting a dual-channel mechanism in which the chemical environment determines site selectivity. Base activation has also been explored by Kwon et al., who showed that electron-rich substrates can trigger covalent reactions on carbon lattices without the need for photoinitiation43. More recently, Piletsky et al. show that H2O2 can effectively mediate the aryl diazonium chemistry, significantly accelerating the OCC formation44. These strategies expand the chemical toolbox for OCC creation, offering new routes to functionalize nanotubes under mild or non-photochemical conditions.

Cycloaddition

Cycloaddition reactions provide a structurally constrained route to controlling OCC configurations by forming both covalent bonds in a single concerted step. He et al. reported [2 + 2] photocycloaddition between SWCNTs and various enone compounds can generate OCCs under UV activation45. More recently, Qu et al. demonstrated a thermally driven [2 + 2] cycloaddition between SWCNTs and N-methylmaleimide, which resulted in significantly reduced spectral diversity compared to diazonium-based methods46.

The key advantage of divalent chemistry, such as [2 + 2] cycloaddition, lies in its inherent geometric constraint: two adjacent carbon atoms on the SWCNT lattice react simultaneously with the enone, which serves as both the functional moiety and its own pairing group. This locks the defects into an ortho binding configuration, excluding para configurations entirely. As a result, the number of possible binding geometries is effectively reduced by half, leading to narrower and more uniform emission spectra46. These insights suggest that revisiting other divalent chemistries, such as those reported by Kwon43 and Gifford47, may uncover additional routes to geometrically constrained defect formation.

Additionally, among the three ortho isomers, Qu et al. found that the reaction temperature (80-140 °C) modulates the relative distribution of configurations46. This temperature-dependent selectivity provides a synthetic handle to further refine emission properties by controlling the OCC at the atomic level.

DNA-patterning of OCCs

While chemical and photochemical methods typically yield statistical distributions of OCC binding configurations, emerging approaches aim to position OCCs deterministically along the SWCNT lattice. Lin et al. demonstrated that DNA strands with designed periodicity can create remarkably ordered arrays of sp2 defects, with a helical spacing that matches the underlying nanotube chirality (Fig. 1e)48. This method builds on guanine chemistry initially developed by Zheng et al., who found the guanine base in DNA could be activated to react with SWCNTs by singlet oxygen49. Interestingly, the resulting covalent attachments form sp2-type defects—not sp3 quantum defects—but still act as shallow exciton traps, with spectral signatures distinct from those of deeper diazonium-derived OCCs48,50.

In contrast, Wu et al. developed a DNA-guided approach that incorporates modified bases such as 5-iodo-uracil into the DNA strand as the reactive sites51,52. Upon photoactivation, the aryl iodide moiety initiates sp3 defect formation, enabling the creation of deep exciton traps with well-defined emission features. This strategy holds the potential to allow nanometer precision in OCC placement, leveraging DNA wrapping geometry and steric effects to tune the spacing between OCCs. The ability to position multiple color centers along a single nanotube with spatial regularity provides a platform for engineering coherent multi-emitter arrays or enabling exciton coupling between adjacent OCCs.

Beyond molecular templating, physical patterning techniques may enable spatially defined patterning of OCCs directly on solid substrates. Huang et al. demonstrated a photolithographic method to “write” OCCs on SWCNT thin films using a light-driven diazoether reaction53, producing micron-scale arrays of SPEs with spectral specificity and robust near-infrared emission54. Similarly, Dou et al. employed microcontact printing with solvent-tuned diazonium chemistry to pattern OCCs on surfaces55. Together, these approaches bridge chemical and physical patterning, expanding the design space for OCC-based optoelectronic and quantum photonic devices.

Post-synthetic reconfiguration of OCCs

Even after the initial formation of an OCC, the defect configuration is not necessarily the correct one. For future quantum technologies, the ability to erase or correct improperly formed color centers will be essential. To this end, Qu et al. demonstrated that laser irradiation (e.g., at 561 nm) can reconfigure kinetically trapped OCCs into thermodynamically more stable structures56. The laser annealing narrowed the PL spectrum by eliminating higher-energy defect states, offering a post-synthetic method to transform defect configurations and refine their quantum properties.

Moving toward uniformity

The ability to synthetically select or anneal OCC configurations brings us closer to achieving reproducible single-photon sources, although several open challenges remain: (1) The reproducibility of selective ortho/para defect formation across different nanotube chiralities remains uncertain: current methods often focus on optimizing (6,5) SWCNTs, while the situation of zigzag or large-diameter nanotubes is still underexplored. (2) The extension of chemical reactivity to other moieties, such as amines, boron, or organometallics, for many non-diazotizing functionalization routes remains unclear. (3) The precision of deterministic defect control using DNA templating, and the feasibility of translating this precision to solid-state lithographic or scanning-probe techniques, also remain unknown. The ongoing development of defect placement and configuration control will be pivotal for transforming OCCs into scalable building blocks for photonic and quantum technologies.

Computational studies of SWCNTs functionalized with molecular defects

Theoretical and computational studies have played a pivotal role in elucidating how OCCs modify the intrinsic electronic and excitonic behavior of SWCNTs. By combining ab initio studies and molecular dynamics approaches, researchers have systematically explored how different chemical modifications introduce specific localized electronic states, alter exciton dynamics, and generate new radiative recombination pathways. The results indicate plausible synthetic targets with desired properties for specific applications. In fact, computational insights became crucial for the rational design of SWCNT-based devices for applications ranging from photovoltaics to quantum light sources. This section presents a brief review of the computational investigations of SWCNTs functionalized with OCCs. We discuss the evolution of theoretical approaches, major findings related to defect chemistry, excitonic behavior, dynamics, and emerging directions for future research.

Early investigations: band structure and localized states

Initial computational studies focused on understanding the basic perturbations induced by molecular defects on the electronic structure of SWCNTs. Tight-binding models and effective mass approximations were among the first approaches employed to predict how covalent functionalization disrupts p-conjugation and induces mid-gap electronic states. It was computationally established that defects introduce localized states within the bandgap, influencing both transport properties and optical absorption57. These early models, while simplified, brought forward the critical concept that covalent functionalization could serve as a tool for bandgap engineering. Subsequent first-principles density functional theory (DFT) studies refined these predictions. For instance, calculations of oxygen-containing functional groups reveal that defect sites act as electron acceptors, locally distorting the SWCNT lattice and altering the density of states near the Fermi level22,58. Together with experimental observations59, these findings provided early validation that molecular functionalization can be exploited to control electronic behavior in a predictable manner.

Excitonic effects: from band structure to optical signatures

The discovery of strong defect-induced PL in functionalized SWCNTs sparked intense computational efforts aimed at unraveling the mechanisms underpinning these new emission features from an excitonic or quasi-particle perspective. Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT)58,60 and many-body perturbation theory (GW-BSE)61 were employed to explicitly treat exciton properties and their effects on the radiative emission. These and other theoretical investigations found that defects introduce localized potential wells that can trap mobile excitons, confirming conclusions reached in experiments25. Specifically, TD-DFT simulations of finite-size SWCNTs elucidated how aryl and oxygen adducts create optically active trap states below the pristine E11 band, commonly referred to as E11* excitons (to be discussed later in this section). These localized excitonic states result in strong, redshifted emission with an increased quantum yield compared to pristine SWCNTs.

The overall trapping mechanism can be described as follows: In pristine SWCNTs, the extended network of π-orbitals results in large excitons (reaching sizes of ~5–10 nm or larger) that are highly mobile62,63. The introduction of covalent defects on the SWCNT surface results in potential wells that trap and scatter the excitons. If spatially trapped at the defect site at the E11 energy range, vibrational relaxation redistributes the excitonic population64,65,66 from the E11 energy to the E11* or E11*− energy region, effectively localizing and immobilizing the exciton to the vicinity of the defect58,67,68. The degree to which the defect emission is redshifted from the E11 is dependent on the depth of the potential energy well of the defect67. The depth of the well is governed by both the local defect morphology/binding configuration60 and the chemical identity of the defect moieties. Across reported defect chemistries and chiralities, the resulting redshifts span ~0.1 eV to nearly 0.4 eV, consistent with experimental trends37. In this way, controlling the optical properties of functionalized SWCNTs is a game of controlling both the defect chemistry and the morphologies that form28,69.

Chemistry and geometry of defect sites

The wide range of synthetic strategies available for decorating SWCNTs with covalent defects enables substantial structural diversity. Because defect structure plays a central role in determining their optical properties, significant efforts have been devoted to understanding the structure-property relationships and identifying strategies for controlling defect formation. A unique strength of atomistic modeling lies in its ability to map how specific functionalization schemes modulate the electronic structure and light-emission properties. Here, we review how computational studies have elucidated these structure-property relationships associated with covalent functionalization.

In this section, we use “defect morphology” to refer to the relative positions and bonding geometry of the sp3-functionalized carbon atoms, and “defect chemistry” to denote the chemical identity of the attached moieties.

Covalent functionalization

Covalent functionalization has emerged as a reproducible and robust approach for introducing stable chemical defects into SWCNTs28,32,70,71, converting local carbon hybridization from sp2 to sp3. Early DFT simulations58,72 elucidated that the introduction of a single functional group results in a single bond to an adjacent carbon atom that would either become charged or a radical. This condition is quite unstable, and the reactive environment enables the charged or radical carbon atom to quickly capture a second functional group, resulting in two functionalized carbon atoms in close proximity60. There are a number of plausible, unique morphologies that can result60,73. It turns out that adjacent (nearest-neighbor, “ortho”) or third-nearest neighbor carbons (“para”) provide the most experimentally comparable spectra74. Further positions exhibit reduced emission intensity74. For zigzag SWCNTs (i.e., those where n or m = 0), there are two unique directions with respect to the SWCNT axis. One of these has both functional groups positioned at carbon atoms along the SWCNT axis. The other configuration places them along the chiral vector 30° (or −30°, equivalent by symmetry) compared to the SWCNT axis. For chiral SWCNTs (i.e., where neither n nor m is equal to 0), there are three distinct morphologies. One involves functionalization of two carbon atoms along the chiral angle, and the other two lie at ±30° from the chiral axis. See Fig. 1a for a (6,5) chiral SWCNT example where the ortho and para configurations are labeled as blue and red, respectively, with all three directions labeled. The stability of each configuration is largely dictated by the hybridization of the carbon atoms in the SWCNT network. Since π-orbital overlap lends stability to the systems, those bonds with the strongest π-orbital overlap in the pristine system are also the least reactive75. About a decade ago, researchers began to discover the differences in properties between these morphologies and guide efforts targeting specificity73,76.

The relative predominance of the (6,5) SWCNT in synthetic efforts77 makes it a readily available chirality for functionalization and has been the subject of the most intense study over the past decade. The chiral angle for this tube is ~27° ≈ 30°. The morphology that involves functionalization across carbon atoms lying along the chiral angle is labeled L27 ≈ L30. The other morphologies involve functionalization of carbon atoms lying at 87° (L87) ≈ 90° (L90) and −33° (L-33) ≈ −30° (L-30) with respect to the tube axis in a left-to-right reference frame. Spectroscopic studies of functionalized (6,5) SWCNTs revealed the emergence of two distinct emission features. The exciton and resulting spectral feature of the pristine system were labeled as E11. The “11” nomenclature arises since the electronic transition can be described as a transition between the first Van Hove singularity from the occupied single-particle orbitals to the Van Hove singularity from the unoccupied single-particle orbitals. The least-redshifted and most-redshifted emission features are labeled E11* and E11*−, respectively. The most prominent emission feature in (6,5) SWCNT is E11*, which is redshifted from E11 by 0.13–0.19 eV25,43. This emission feature appears in most functionalization conditions. The appearance of a second emission feature, E11*− redshifted about 0.25 eV or more, occurs primarily for specific functionalization conditions, particularly in the presence of a high concentration of reagent and with larger functional groups34,35. This perplexing result was explored using DFT78 and TD-DFT79. Finite-length unit cells were employed. The termination of dangling bonds at the ends of the tubes is carefully chosen to avoid the introduction of superfluous edge-localized trap states into the electronic structure79. The proper capping scheme is dependent on the value of (n-m) for each tube chirality. These computational studies attribute the main E11* emission feature to the moderately redshifted L87 morphology80. The most redshifted E11*− feature is attributed to the L27 morphology. The L-33 morphology introduces an electronic transition only marginally separated from the E11 band by less than 0.1 eV and therefore appears, in experiment, only as a slightly broadened pristine-emission band60. With the main emission features attributed to specific defect morphologies81, an important synthetic question becomes how to control the formation probability of each morphology and, consequently, the dominant emission features (E11* or E11*−) of the resulting material. It is important to note, however, that morphology alone does not uniquely fix the emission energy, and that important contributions from nanotube chirality and defect chemistry further modulate the observed spectral positions37.

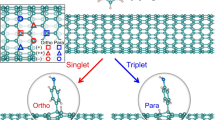

The emission energies associated with each morphology are dependent on the chirality of the SWCNT, as heavily discussed and visualized by Gifford et al.47. For example, as mentioned above, for the (6,5) SWCNT, the most redshifted ortho feature is the one that functionalizes two carbon atoms along the SWCNT’s chiral angle. However, interestingly, for the (7,5) SWCNT, the same ortho configuration results in the least redshifted spectral feature. Thus, a new notation is needed in order to directly compare the anticipated emission energies across different SWCNT chiralities, which is independent of the exact chiral angle. For this purpose, functionalization along the chiral angle is denoted L+ because it forms the smallest positive angle with respect to the tube axis in a left-to-right (L) reference frame. The morphologies that form the greatest positive angle and negative angle are labeled L + + and L-, respectively. Perhaps most notably, the ordering of redshifts of emission features for different morphologies is largely dependent on the value of mod(n-m,3) for an (n,m) chirality SWCNT47.

Using DFT, this observation can be understood by examining the nodal structure of the SWCNT’s frontier orbitals. For pristine SWCNTs, the HOMO and LUMO single-particle orbitals are oriented along non-parallel directions with respect to each other, and between SWCNTs where mod(n-m,3) = 1 (“mod1”) or mod(n-m,3) = 2 (“mod2”), the direction of the HOMO and LUMO flips47. In Fig. 2, we show an example for two zigzag SWCNTs, (10,0) [left column] and (11,0) [right column]. The like-phase parts of the HOMO in the (11,0) SWCNT (Fig. 2, right) propagate parallel to the SWCNT axis, while the LUMO propagates along the L+ direction (at an angle with respect to the SWCNT axis). The continuous pathway of in-phase orbital alignment enables electron flow, delocalization, and stabilization of the electronic state. For the mod1 (10,0) SWCNT (Fig. 2, left), the opposite is true.

Calculated electron density of the HOMO and LUMO for functionalized mod1 (red background) and mod2 SWCNTs (blue background). Green traces indicate regions of continuous electron delocalization due to the same orbital phase overlap. Yellow dashed lines indicate where a node disrupts electron delocalization. Green dots connected by a line indicate the carbon atoms that are functionalized and the bond that is converted to a single bond upon functionalization. The yellow ovals highlight the large regions of loss of electron density in that MO due to functionalization. The HOMO in the mod1 system contains nodes parallel to the SWCNT axis, allowing for electron delocalization in the axial direction. Functionalization along L+ preserves this electronic structure everywhere except on a line through the defect. Functionalization along L + + or L−, however, introduces a node into the electronic structure along the remaining lines. Electron delocalization near the defect site is thereby interrupted, resulting in the formation of spatially localized orbitals around the defect site. Reproduced from Gifford et al.47.

Functionalization of two adjacent carbon atoms perpendicular to the like-phase orbital propagation direction introduces a node [see Fig. 2, ortho(+) for the mod1 (10,0)], destabilizing the HOMO and stabilizing the LUMO, which closes the gap and introduces a strong redshift. Functionalization along the direction parallel to the like-phase direction, on the other hand, does not lead to large disruption in the orbital propagation and only provides a weak redshift [see Fig. 2, ortho(++) for mod1 (10,0)]. For mod2 SWCNTs (Fig. 2, right), the direction of like-phase orbital direction is reversed. This explains why the ordering of redshifts for the equivalent defect configurations is reversed between the mod1 (L−, L + +, L +, least-to-most redshift) and mod2 (L +, L + +, L−) SWCNTs47. Thus, this additional symmetry (beyond, e.g., the chiral angle) defined by the mod(n-m,3) value now uniquely assigns and provides the ordering of all spectral features for all ortho and para configurations in all possible semi-conducting SWCNTs47.

In addition to the emergence of the E11* feature that was observed with functionalization of (6,5) with small chemical groups, E11*− emerges when both ortho carbon atoms in the SWCNT bond to a single carbon atom in the functional group (so-called “divalent functionalization”). There is instability in these configurations, compared to those previously discussed, which bind two functional groups to two SWCNT carbons (monovalent), due to the formation of divalent ‘bridges’ that form an unstable three-membered ring between the ortho carbons of the SWCNT and the functional group. In this case, the L-33 (L-) configuration becomes quite unstable, as formation of the three-membered ring imposes substantial angle strain on the system. On the other hand, formation of the L87 (L + +) morphology results in very small perturbations to the sp2-hybridization of the carbon atoms in the SWCNT and is thus far more thermodynamically stable. Furthermore, the sp3-hybridization of the carbon atom in the bridging functional group is nearly retained. The result is the favoring of the L87 (L + +) morphology75. This demonstrates how different classes of the functional group can direct the defect morphology.

While defect-induced redshifts in functionalized SWCNTs are heavily dependent on defect morphology, the properties of the attached functional groups (i.e., the chemical makeup of the adducts) also play an important role. From a theoretical perspective, the magnitude of redshifts is governed by two main chemical factors: (i) the hybridization character of the defect bond (i.e., the degree of s-character), and (ii) the electron-withdrawing strength of the functional groups through inductive effects43,75,82. Functional groups that retain higher s-character upon bonding, such that the bonding carbon atoms remain nearly sp2-hybridized, tend to produce smaller redshifts (on the order of ~0.1 eV) compared to monovalent or divalent sp3-hybridized adducts.

In addition to bond hybridization, the electron-withdrawing ability of functional groups provides another degree of chemical tuning within a given defect morphology. For example, replacing CH3 with more strongly electron-withdrawing 3,5-(NO2)2-aryl and -CF3 substituent in (6,5) SWCNTs increases the E11* defect-induced redshifts by 60 meV and 62 meV, respectively, as experimentally demonstrated by Piao et al.25 and Kwon et al.43. This degree of chemical tunability is substantial, yet remains smaller than the larger morphology-driven energy differences that distinguish E11* and E11*−, which are typically separated by ~100 meV or more in the same (6,5) SWCNTs34,43,75,83. To further extend chemical tunability, heteroatom-based substituents (e.g., direct -F or -Cl attachment) have been explored theoretically using DFT as additional routes to modify defect energetics76.

Importantly, although theory robustly predicts the energetic ordering and optical signatures associated with defect morphologies, experimentally accessing specific configurations remains probabilistic and depends sensitively on reaction pathways and kinetics34,46,56.

Interactions between defects

Covalent functionalization of SWCNTs typically produces sparse, statistically distributed defects, with an average axial separation between adjacent OCCs of ~20 nm under reaction conditions optimized at the ensemble level for bright defect photoluminescence25. More recently, control over the axial separation between adjacent defects has been improved by pre-constructing particular strands of single-strand DNA (ssDNA)48,51,84,85,86. In these systems, the ssDNA forms covalent bonds only at the guanine base units86 or the halogenated bases51 within the ssDNA strand. This tunable separation between defects opens up a novel channel to manipulate the emission signals beyond that of single defects by inducing defect-defect interactions84,85.

Figure 3a shows the standard model for exciton interactions, often referred to as the Kasha model for interacting excitons87. Figure 3b presents the linear absorption spectra as a function of the defect-defect separation length between 1 and 4 nm. This can be modulated in an experiment by increasing the distance between adjacent guanines within the ssDNA strand84. From one to two defects, the J-aggregate-like splitting occurs, such that the lower state is optically active while the upper state is dark. As the distance increases, the splitting reduces, retaining the lower state’s bright character at all lengths explored. Figure 3c shows the extracted J-coupling values (black line) as a function of the separation length and scales nearly as 1/r (dashed black line). The coupling parameter is often approximated as classical dipole-dipole coupling \(J\sim {\mu }_{01}^{2}\,/\,{r}^{3}\,\); however, we note that exchange interactions K likely exist when the defects are closer than 1–2 nm due to large exciton–exciton overlap88, which are neglected in the model but are included in the TD-DFT simulations. Figures 3d and 3e explore the absorption spectra of an increasing number of defects, N = 1 to 5. This can be achieved in experiments by increasing the total number of guanine groups in the ssDNA strand. As the number of defects increases, the low-energy bright state decreases in energy. However, as shown in Fig. 3e, the S1-to-S2 splitting is largely unchanged due to the fixed defect-defect separation length between adjacent defects, and all states decrease in energy in parallel with increasing numbers of states. Due to the finite possible size of the bound electron-hole, the energy of the S1 state exhibits a plateau near E1 ~ 1.3 eV when extrapolating the transition energy to an infinite number of defects.

a Interacting exciton Hamiltonian. b Simulated absorption spectra at varying separation lengths of two defects along the SWCNT axis. c J-coupling and splitting asymmetry extracted from the TD-DFT simulation. d Simulated absorption spectra as a function of the number of adjacent defects. e Singlet exciton manifold as a function of the number of adjacent defects. Panels (a–c) adapted from Weight et al.85. Panels (d, e) adapted from Zheng et al.84.

Even though our theoretical understanding of the optical properties in all possible defect configurations as well as defect-defect couplings is robust, our understanding of what happens in the experiment is largely limited. Specifically, how to control the formation of specific defect configurations is lacking42. Some efforts have been made in examining the resulting structures from resonance Raman spectroscopy81. To our knowledge, the best theory that exists relies on the π-orbital mismatch in the region close to the defect47. This theory suggests that defects that form near others should result in a different configuration compared to the original defect. If functionalization conditions are such that multiple defects end up spatially close together ( < 10 nm), these directing effects play a role in the resulting morphologies and, therefore, the optical properties of the resulting system. One such condition is a high concentration of reagent for dichlorobenzene-functionalized (6,5) SWCNTs. Systems formed under these conditions are decorated with a higher density of defects than for lower concentrations of reagent. Due to this, some defects are inevitably found in the vicinity of others. For low defect densities, the main emission feature is E11*. As the concentration of the reagent increases, the E11*− peak grows in ref. 75. This demonstrates the directing effects of defects and enables increased tunability by controlling defect-defect interactions.

Strong coupling with quantized cavity modes enables increased tunability

Exciting new computational results looking at spin dynamics in functionalized SWCNTs reveal spin-polarized transport and chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS) effects mediated by molecular defects46,89. Theory enables quantum defect engineering of SWCNT systems to achieve phenomena like superradiance, multi-exciton generation61, and coherent light-matter interactions90. Strong light-matter interactions91,92, in particular, show great promise for additional control over the emission frequency and complex optical properties in SWCNTs93. Recently, various experimental explorations into SWCNTs94,95 coupled to a quantized photonic mode have realized the strong photophysical capabilities96, such as long-range energy transfer between bundles of two different pristine SWCNT chiralities (i.e., donor-acceptor process)97, photophysics of sp3-defected SWCNT exciton-polaritons98 and trion-99/biexciton100-polaritons in pristine samples.

Motivated by the experimental work of Graf et al.94, where the authors proposed using strong light-matter coupling to tune the emissive properties of SWCNTs, Fig. 4 presents theoretical work101 exploring the strong light-matter interactions between a pristine (6,5) SWCNT system and a Fabry-Pérot optical cavity. Figure 4a schematically shows the polaritonic Hamiltonian102,103, which couples the cavity and matter degrees of freedom. While all electronic transitions are coupled to the quantized photon, for SWCNT systems, the bright E11 dominates the light-matter interactions due to the strong dipole strength. The common picture of light-matter hybridization to form the so-called upper |+〉 and lower |−〉 polaritonic states is shown in Fig. 4b, where the total splitting is often referred to as the Rabi splitting ΩR. Figure 4c shows the excitonic linear spectroscopy inside the cavity at four different cavity frequencies ωc = (i) 1.0, (ii) 1.5, (iii) 2.0 (cavity-E11 resonance), and (iv) 2.5 eV. Importantly, the energy of the bright, dipole-active character can be manipulated to appear below the threshold of the well-known SWCNT dark state manifold (green vertical dashed lines). Outside of the cavity, these dark exciton states reduce the PL efficiency of the system due to non-radiative relaxation from the dark excitons to the ground state. Looking forward to mixing cavity and sp3-defected SWCNT systems95, one may be able to further tune the emission features, or other interesting photophysical phenomena, by introducing complex interplays between the bright E11 and E11* states mediated by the quantized photonic mode.

a Polariton Hamiltonian, b Schematic of light-matter hybridization between electronic and photonic degrees of freedom, forming polariton states. c Excitonic spectra of the coupled SWCNT/cavity polaritonic system for four choices of cavity frequencies ωc = (i) 1.0, (ii) 1.5, (iii) 2.0 (resonance with the bright E11 transition), and (iv) 2.5 eV, exhibiting strong optical emission below the dark state threshold (vertical green dashed lines). The SWCNT E11 transition density outside the cavity is shown in (c). Panel (c) adapted from Weight et al.101.

Electronic and nuclear dynamics: exciton relaxation, trapping, and chemical reactivity

Beyond static electronic structure calculations, recent computationally intensive efforts have focused on time-resolved simulations to capture excitonic dynamics. These simulations directly follow several key processes, including the competition between free exciton migration and defect trapping, as well as the vibronic relaxation at the defect site after trapping. Such pathways lead to radiative recombination and/or non-radiative losses as well as coherent vs. incoherent exciton dynamics induced by defect-induced energy landscapes. For example, a recent nonadiabatic molecular dynamics study using trajectory surface hopping methods has simulated exciton migration and self-trapping at defect sites, revealing ultrafast processes on sub-picosecond timescales64,104. Other joint theory-experiment studies105,106,107 demonstrated complex excitonic dynamics due to the presence of multiple, interacting defects, from the recently developed ssDNA functionalization schemes48,84,86, that lead to complex relaxation behavior, emphasizing the need for multi-defect modeling84,85 to replicate experimental conditions.

Another important contribution of these dynamical simulations is elucidating chemical reaction pathways and mechanisms for the formation of specific binding configurations. For instance, recent studies demonstrating the successful photochemical substitution of SWCNTs have been carried out108. In addition to ortho functionalization (1,2-substitution), para functionalization (1,4-substitution) is also plausible, particularly under photochemical conditions that generate longer-lived intermediates or radicals following the addition of the first functional group. The intermediate can exist in the singlet or triplet excited state, leading to distinct spin-selective photochemistries, ultimately resulting in the formation of ortho and/or para-defect morphologies, respectively108. These experimental results were supported by first-principles simulations, which mapped out various reaction pathways and identified the corresponding transition states, providing a detailed mechanistic understanding of the functionalization process. A similar theoretical framework was applied to identify the formation of three possible bonding configurations of the divalent molecular defects leading to distinct emission spectra46. By calculating transition states (Fig. 5a, b), this effort demonstrated kinetic preference of specific defect morphologies, enabling experimental control through reaction temperature (Fig. 5c). More broadly, emerging theoretical frameworks that connect π-electron topology, Clar sextet distribution, and edge-state formation offer new opportunities to rationalize defect-induced localization in carbon nanostructures and may provide additional guiding principles for future OCC design and placement109,110.

Transition state search by the CI-NEB method shows that the cycloaddition reaction pathways of the (a) three divalent OCCs on (6,5)-SWCNT are similar, with differences in barrier heights (b), suggesting kinetic control of divalent OCCs using temperature. The top panels show the calculated three transition states, whereas the bottom panel depicts the potential energy along the reaction coordinate. c Emission and relative energy of the three possible bonding configurations of OCCs generated by N-MMI. TD-DFT simulated emission wavelengths of OCCs featuring the PP( − 2/3, 1/3) (red), PP(1/3, 1/ 3) (blue), and PP(1/3, −2/3) (black) bonding configurations (oscillator strength vs simulated wavelength shown in the left and bottom axes in black), superimposed with the experimental PL spectra from (6,5)-SWCNTs-N-MMI synthesized at 80 (green) and 100 °C (yellow) (PL intensity vs experimental wavelength shown in the right and top axes in red). Panels (a)–(c) adapted from Qu et al.46.

Single photon emission from SWCNTs and OCCs-bearing SWCNTs

Quantum optical experiments using SWCNTs initially focused on probing excitonic dynamics and photon statistics under cryogenic conditions, where intrinsic disorder led to localized exciton states capable of emitting single photons19. Over the past decade, the field has witnessed a transition from studying the naturally occurring localized states in pristine nanotubes111 to deliberately engineer defects and dopants28,32. These modifications have aimed to enhance the fundamental—improving spectral stability at room-temperature operation—as well as quantum optical properties such as; purity: the emitted photons being one at a time, indistinguishability: the coherence of the individual photon where identical optical properties for subsequent emitted photons are expected in terms of wavelength, linewidth, lifetime, polarization, with zero spectral fluctuations, brightness: the rate of photon generation and detection, and integration: the ability to precisely place the quantum defects with nanoscale precision, coupled to nanophotonic structures and electronic circuits for controlling the quantum light emission paving the way for on-chip quantum photonic devices.

In the following subsections, we summarize the defect-induced exciton localization, photophysical properties, and photonic integration of SWCNTs for single-photon emission. In addition to the extensively studied covalently functionalized SWCNTs, recent progress of alternative approaches for SPE in SWCNTs and SWCNT-based materials is also reviewed in this section.

Molecular defects and their photophysical properties

Ma et al. chemically introduced isolated oxygen dopants in (6,5) SWCNTs, forming solitary oxygen-related defect sites on the nanotube surface112. Unlike the sp3 OCCs discussed above, these oxygen dopants preserve the sp2 lattice and generate qualitatively different excitonic states. The oxygen-related defects created >100 meV trap states that emitted single-photons with g2(0) around ~0.3 (corresponding to ~70% SPE purity) in the 1100–1300 nm range at room temperature. Although operating till 300 K, the authors identified 200 K as the optimum condition with >50% of the doped tubes exhibiting SPE while free from spectral fluctuations. This temperature regime is accessible using commercial thermoelectric coolers, signifying the potential of oxygen-doped SWCNTs for integrated quantum photonic applications.

He et al.26 showed that high-purity single photons can be achieved with the aryl OCCs. The SPE from these defects exhibit g2(0) values < 0.01, indicating 99% of emission events are single photons at room temperature. Moreover, as SWCNTs come in various chiralities and diameters, each with distinct E11 energies, the emission of these OCCs could be tuned across the entire telecom band simply by functionalizing different nanotube species and thereby extending the wavelength range from 1100–1550 nm. The defect-tailored (6,5) SWCNTs with a smaller diameter of 0.76 nm emitted around ~1100 nm, whereas larger-diameter (10,3) tubes of 0.94 nm emitted single photons directly in the telecom C-band at ~1550 nm. The non-polar environment of the localized defect enabled improved photostability, where the emission count rate fluctuations were closer to the shot-noise limit of detection, indicating minimal blinking or bleaching at room temperature. The reported 12% overall SPE quantum efficiency with ~100 s ps lifetime and <30 meV linewidth at room temperature is promising for quantum photonic applications. Count rates of 100 kHz were reported despite a low combined photon collection and detection efficiency at telecom wavelengths, indicating the potential for scaling to MHz rates through direct coupling to optical waveguides or cavity-enhanced architectures.

A central challenge for OCC-based SPEs is spectral inhomogeneity arising from multiple defect configurations generated during functionalization, which can broaden ensemble emission and hinder the production of identical emitters. Recent advances in chemical control, as discussed in detail in the section “Chemistry of organic color centers”, have begun to address this limitation by selectively favoring specific defect geometries. For example, symmetry-guided functionalization of zigzag SWCNTs and reaction-condition-controlled diazonium chemistry, in combination with post-synthesis annealing, have been shown to dramatically narrow emission distributions and stabilize deeper exciton traps34,36,42,46,56. These advances establish a direct link between defect chemistry and quantum optical performance, demonstrating that precise chemical control enables reproducible, spectrally stable, and tunable single-photon emitters operating into the telecom band. Such progress is essential for realizing scalable arrays of nanotube-based quantum light sources.

Ma et al. studied exciton complexes associated with oxygen dopants, identifying dark excitonic states below the neutral excitons as well as red-shifted trap-bound excitons113. For OCCs, magneto-PL studies by Kim et al. demonstrated magnetic brightening of spin-dependent exciton fine structures81. PL blinking dynamics of the defects further revealed the sensitivity of emissions around the environment of the nanotubes107. Kim et al. reported the PL intensity variations arising from the existence of a fluctuating potential barrier in the vicinity of the defect and also identified the role of dark exciton states by analyzing the temperature-dependent PL dynamics114. Hartmann et al. studied how the E11 exciton lifetime responds to varying concentrations of defects, providing additional insight into relaxation dynamics115. Solvent- and wavelength-dependent PL relaxation dynamics further illustrate the sensitivity of defect excitons to their dielectric surroundings116.

At the single defect level, cryogenic optical spectroscopy revealed even richer excitonic behavior. He et al. reported red-shifted emissions below the E11*, which are now identified as charged excitons or trions, and explored how the nanotube’s surroundings can preferentially stabilize these emissions35. Photon-correlation spectroscopy by Nutz et al. showed that individual hexyl group defects can host either neutral defect excitons or trions, but not both simultaneously, indicating mutual exclusivity of these two states117. Additionally, a metastable dark state can intermittently capture the exciton through a shelving process, introducing a brief off-period in the emission with lifetimes on the order of 10–100 ns in doped nanotubes. Finally, Kwon et al. demonstrated that trions can be efficiently generated and localized at the trapping chemical defects, exhibiting brightness enhancements of up to a factor of 16 compared to neutral nanotube excitons118.

Antibunching in air-suspended SWCNTs

As introduced in the previous sections, OCC formation on SWCNTs offers the advantages of chemically tunable optical properties through the use of varied molecular precursors that can covalently bond to the carbon lattice. Through the introduction of dopant states with different emission energies and the achievement of potential traps deeper than thermal energy, single-photon sources with the desired properties can be realized in these covalently functionalized SWCNTs. Nevertheless, functionalization processes are usually solution-based39,40, leading to undesired results that can degrade the light emission intensity of SWCNTs, such as shorter nanotube lengths and higher defect densities. Furthermore, due to the high sensitivity of SWCNTs to the external dielectric environment, the exciton properties are susceptible to environmental perturbations. For instance, exciton diffusion in SWCNTs will be hindered by dielectric disorder119, and exciton non-radiative recombination predominantly occurs at quenching sites between the SWCNT and the substrate120. To overcome the aforementioned issues and achieve stronger PL emission for quantum light emission applications, air-suspended SWCNTs are considered a promising solution. Using chemical vapor deposition (CVD), air-suspended SWCNTs can be grown on substrates to bridge across designed structures, such as pillar posts121,122,123,124, craters111, trenches21,119,125,126,127, or TEM grids128. Taking advantage of their pristine and defect-free characteristics, suspended SWCNTs boast their bright PL intensity121, narrow line width122, high quantum efficiency123, suppressed PL blinking and spectral wandering111,124, and long exciton diffusion length119,125,127. Air-suspended SWCNTs could therefore play a significant role in the progress of SWCNT-based SPEs.

In the first report on the observation of anti-bunching from air-suspended SWCNTs, Hofmann et al. found that spontaneous exciton localization also occurs in air-suspended SWCNTs at a temperature of 4.2 K111, similar to SWCNTs placed on substrates19. Furthermore, clear anti-bunching behavior with g(2)(0) values reaching 0.3 was observed through photon correlation measurements with pulsed excitation. In a follow-up work, Hofmann et al. showed that spontaneous exciton localization is a general phenomenon at low temperatures and can result from unintentional potential fluctuation due to structural or environmental disorder induced by contamination or gas adsorption128. In comparison, continuous wave excitation photon correlation measurements on ultra-clean air-suspended SWCNTs conducted by Sarpkaya et al. showed no anti-bunching behavior at 10 K, despite the observation of enhanced linewidth and prolonged PL decay time in these SWCNTs124. The inconsistent results may stem from the use of different laser operation modes, where pulsed excitation offers more advantages in observing anti-bunching than continuous wave excitation due to its better temporal resolution. Furthermore, the time jitter of detectors may also affect the photon correlation results. Following the work on low-temperature photon correlation measurements, Endo et al. investigated the temperature dependence of photon correlation from 6 to 300 K on air-suspended SWCNTs126. The anti-bunching behavior was sustained at elevated temperatures and even at room temperature, although spontaneous exciton localization is expected to become weaker128. While the observation of anti-bunching behavior at room temperature is encouraging, the g(2)(0) value of ~0.6 in this experiment is insufficient to claim single photon emission at room temperature.

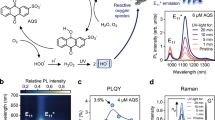

In another report on room temperature photon correlation characterization of air-suspended SWCNTs, Ishii et al. obtained a low g(2)(0) value of 0.27, resulting from EEA21. In the EEA process, an exciton can recombine nonradiatively by giving its energy to another exciton via an Auger-like process during the scattering of two excitons129,130. When multiple excitons exist, EEA causes rapid recombination until there is only one exciton remaining, leading to single-photon emission. Since the excitons in air-suspended SWCNTs exhibit long diffusion length and are confined to one dimension, efficient EEA was reported130. In the study of anti-bunching in air-suspended SWCNTs by Ishii et al., the dependence on excitation power, SWCNT chirality, and suspended tube length was compared. The g(2)(0) value was observed to increase with excitation power and eventually saturates, while the saturated g(2)(0) value and the minimum achievable g(2)(0) value vary with SWCNT chirality and tube length. Based on the simulation results, it was concluded that low exciton generation rate, long exciton diffusion length, and long nanotube length are beneficial for achieving low g(2)(0) values. Among these factors, the length of the tubes has the largest influence on obtaining low g(2)(0) values. Since the only defect sites in pristine air-suspended SWCNTs are the tube ends, the proportion of excitons being quenched is reduced for longer nanotubes. To further enhance the EEA rate in air-suspended SWCNTs, Li et al. employed a non-covalent functionalization method in which pentacene molecules were physically adsorbed onto the SWCNT surface131. The local bandgap shrinkage caused by the dielectric screening effect led to the formation of a potential trap for excitons, which would collect the free excitons into the trap, as shown in Fig. 6a. If the size of the potential trap is smaller than the exciton diffusion length, improved EEA efficiency and thereby enhanced single photon emission is expected. As shown in the photoluminescence excitation (PLE) results in Fig. 6b, a new PL emission peak with an emission energy ~15 meV lower than the free exciton peak appeared after molecular decoration, indicating the formation of a shallow potential trap and radiative exciton recombination at the decorated sites. Second-order photon correlation measurement of the new PL peak showed clearly improved anti-bunching behavior, with g(2)(0) values enhanced by up to 27%. The achievement represents a significant step toward realizing room-temperature single-photon emission utilizing only the EEA phenomenon in SWCNTs. Lower g(2)(0) values are expected if deeper potential traps can be formed using materials with higher dielectric constants.

a Schematic illustration of quantum well formation and enhanced EEA caused by pentacene decoration on SWCNT. b PLE map of a pentacene-decorated SWCNT. c Schematic of an OCC-functionalized suspended SWCNT. d PL comparison of a SWCNT before and after functionalization. e PL imaging of the PL peaks shown after functionalization in (d). f Schematic illustration of SWCNT/WSe2 heterostructure. g Band alignment between WSe2 and SWCNTs with varied SWCNT chirality. h PL spectra of heterostructures formed by WSe2 and SWCNTs with varied chirality. Additional PL peaks originating from the interface exciton appeared as the band alignment switched from type I to type II. iSecond-order photon correlation measurement result from the interface exciton emission peak of SWCNT/ WSe2 heterostructure. Panels (a) and (b) adapted from Li et al.131; Panels (c–e) adapted from Kozawa et al.41; Panels (f–i) adapted from Nang et al. (2024)133.

Advanced nanostructures for quantum emission

As discussed in the previous sections, OCCs provide significantly deeper potential traps compared to those created by physical molecular decoration, with trap depths exceeding the thermal energy scale. Enhanced anti-bunching behavior is therefore expected in air-suspended SWCNTs by forming OCCs. The conventional solution-based functionalization process, however, easily damages the air-suspended SWCNTs. To functionalize air-suspended SWCNTs, Kozawa et al. introduced a vapor-phase photochemical reaction to create OCCs41. Air-suspended SWCNTs were first sealed in a chamber filled with iodobenzene vapor. Following UV light illumination, OCCs could be formed on the SWCNT surface, resulting in the appearance of new PL emission peaks, as shown in Fig. 6c and d. The PL images in Fig. 6e clearly reveal that the additional peaks come from the same SWCNT as the E11 peak. Similar to the functionalized SWCNTs introduced in the previous section, the additional PL emission peaks resulting from defect formation in air-suspended SWCNTs also exhibited chirality dependence in PL emission energy and prolonged exciton lifetime. Although photon correlation measurements were not conducted in this study, purer single-photon emission is anticipated if the vapor-phased reaction could be finely controlled to form only one OCC on air-suspended SWCNTs.

Another recent advancement in developing quantum emitters based on air-suspended SWCNTs was achieved through the formation of type II band alignment in mixed-dimensional heterostructures. Nang et al. addressed the first report on the fabrication of air-suspended mixed-dimensional heterostructures consisting of one-dimensional SWCNT and two-dimensional tungsten diselenide (WSe2) (Fig. 6f), and examined the influence of band alignment types132,133. Due to the variable band structure of SWCNTs, which depends on chirality, the band alignment of these mixed-dimensional heterostructures can be adjusted between type I and type II band alignment, as shown in Fig. 6g. While no additional PL emission peaks could be observed in heterostructures with type I band alignment, newly emerged PL emission peaks originating from interface excitons could be clearly observed in type II band alignment heterostructures with energies falling within the telecommunication wavelength range (Fig. 6h. The SWCNT E11 and interface exciton PL emission are further compared by excitation power dependence of PL intensity, time-resolved PL, and photon correlation. The much faster saturation of PL intensity compared to E11 emission under low excitation power and the prolonged PL decay time suggest strong localization of interface excitons. This was confirmed by the anti-bunching behavior in photon correlation with g(2)(0) value reaching 0.467 (Fig. 6i). Since there are almost no defect sites on the SWCNT, the strong localization of these interface excitons was attributed to either tungsten vacancy defect sites in WSe2 or inhomogeneous local strain in WSe2. In either case, the achievement in mixed-dimensional heterostructures opens up a new direction for developing room-temperature SPEs at telecommunication wavelengths based on air-suspended SWCNTs.

Photonic and electronic device integration

The integration of quantum emitters into photonic and electronic structures is essential for quantum photonic technologies. On one hand, this integration allows for nanoscale control over the emitter’s optical properties, helping to mitigate the spectral diversity among individual quantum emitters and allowing for deterministic tuning. On the other hand, quantum emitters in free space or on bare substrates emit photons isotropically, making efficient collection and use of those photons highly challenging. Photonic integration offers a solution to enhance light-matter interaction by enabling high Purcell enhancement, which not only boosts the spontaneous emission rate to achieve higher photon count rates but also channels emission into well-defined optical modes, allowing efficient coupling into on-chip waveguides and off-chip fibers. This is critical not only for high collection efficiency but also for achieving photon indistinguishability, a prerequisite for quantum interference and entanglement-based protocols. At the same time, electronic integration enables precise control over emission characteristics, supporting electrically triggered on-demand single-photon generation without relying on optical excitation, and allowing spectral tunability and modulation through controlled exciton injection and transport. Thus, photonic and electronic integration collectively enhance emitter performance, improve photon extraction and routing, enable precise control over quantum emission, and ensure efficient interfacing with photonic circuits and external systems.

He et al. reported dephasing times (T2) at 4 K ranging from 3 to 12 ps for sp3 defects, with polymer embedding inhibiting charge noise fluctuations, which is an improvement over the ~2 ps typically observed for the band-edge neutral excitons134. These longer coherence times are attributed in part to reduced phonon coupling enabled by the deeper confinement of the localized exciton states. T1 lifetime of 1.5 ns, approaching the intrinsic radiative limit of 2 ns, indicated a high defect-state quantum yield of 50–75%. While promising, the radiative rate must be increased by two orders of magnitude to achieve photon indistinguishability (T2 = 2T1). Therefore, integrating functionalized SWCNTs into photonic structures to enhance spontaneous emission via the Purcell effect is crucial for improving the coherence properties.

Reported photonic device architectures include:

1. Dielectric nanocavities and waveguide coupling: Ishii et al. demonstrated that coupling OCC emitters to photonic crystal microcavities (see Fig. 7a for device architecture) resulted in a ~ 50-fold increase in PL intensity with emission rate about ~17 MHz and ~30% reduction in the emission lifetime confirming an increased radiative decay rate due to the cavity coupling while preserving the single-photon purity even as the excitation power was increased to the saturation level135. The work showed that doped SWCNTs can be combined with mature silicon photonics technology to achieve a brighter source with a higher photon emission rate on the order of tens of MHz while preserving antibunching without transitioning to multi-photon output—an important demonstration for on-chip integrated photon sources. Closely related nanobeam cavities featuring ultralow mode volumes have previously yielded high coupling to individual SWCNT emitters and efficient coupling to integrated waveguides, offering a clear route to on-chip routing of photons after cavity emission29.

a Dielectric cavity: OCC-SWCNTs coupled to a silicon photonic crystal cavity fabricated by e-beam lithography and reactive-ion etching, yielding ~50× PL enhancement and ~30% lifetime reduction through Purcell-enhanced coupling to the cavity mode. b Plasmonic antenna: An OCC-SWCNT positioned within the nanoscale plasmonic nanogap of an Au cavity fabricated by e-beam lithography, achieving Purcell factors up to ~415, radiative lifetime shortening to ~10 ps, and cryogenic HOM visibility up to 79%. c Fiber-coupled open Fabry-Perot cavity: A single OCC-SWCNT emitter positioned at the cavity waist formed between a laser-machined concave fiber mirror and a planar DBR, enabling direct single mode fiber coupling with Purcell factors up to ~30 and photon emission rates ~20 MHz. d Room temperature indistinguishability in fiber-coupled open cavity: A linewidth engineered open microcavity in which the cavity linewidth, rather than the emitter dephasing, defines the photon coherence time, enabling room-temperature two-photon interference with visibilities of 50–65% at telecom wavelengths without external spectral post-filtering. e Ambipolar thin film network: OCC-functionalized SWCNT networks incorporated into an ambipolar light emitting FET with lithographically defined Au contacts, demonstrating gate tunable defect state electroluminescence arising from ambipolar carrier injection. f Single nanotube field-effect transistor: A deterministically placed OCC-SWCNT contacted by graphene electrodes and controlled via electrostatic gating, enabling electrically triggered SPE. The accompanying zoom-in highlights the nanotube channel and contact region, demonstrating precise emitter placement and defect state emission from an individual nanotube. Panel (a) adapted from Ishii et al.135; Panel (b) adapted from Luo et al.136; Panel (c) adapted from Borel et al.137; Panel (d) adapted from Husel et al.27; Panel (e) adapted from Zorn et al.139; Panel (e) adapted from Li et al.140.