Abstract

The presence of offsets, appearing at intervals ranging from 10s to 100s of kilometres, is a distinct characteristic of constructive tectonic plate margins. By comparison, boundaries associated with subduction exhibit uninterrupted continuity. Here, we present global mantle convection calculations that result in a mobile lithosphere featuring dynamically derived plate boundaries exhibiting a contrasting superficial structure which distinguishes convergence and divergence. Implementing a yield-stress that governs the viscosity in the lithosphere, spreading boundaries at the top of a vigorously convecting mantle form as divergent linear segments regularly offset by similar length zones that correlate with a large degree of shear but comparatively minimal divergence. Analogous offset segments do not emerge in the boundaries associated with surface convergence. Comparing the similarity in the morphologies of the model plate margins to the Earth’s plate boundaries demonstrates that transform-like offsets are a result of stress induced weakness in the lithosphere owing to passive rupturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given its potential for insight into underlying mantle properties and dynamics, obtaining a surface velocity field that emulates the facets of plate tectonics through the modelling of convection in a momentum-free fluid remains an ongoing aspiration of geodynamic studies1,2,3,4. Motivated by the observation of relatively aseismic low horizontal strain-rate plate interiors (for example, ref. 5), a primary objective of numerous modelling studies has been to determine the requirements that result in a mantle surface layer (i.e. lithosphere) featuring a mosaic of stiff surface caps. Surface mobility in mantle convection models is enabled by implementing stress-determined deformation to obtain focussed convergent and divergent boundaries; manifested on Earth by subduction and oceanic ridge spreading, respectively. Many of the strides made towards finding the rheological requirements of continuum models that exhibit these qualities have been made using two-dimensional6,7 and regional scale three-dimensional calculations8,9,10, primarily because the presence of the thinner thermal boundary layers that depend on convective vigour (and are understood to characterize terrestrial mantle convection) are considered a necessary requirement for a relevant model. In comparison, the computational requirements and challenges inherent to three-dimensional high-resolution global calculations is especially demanding. The two-dimensional modelling of migrating and focussed plate boundaries separating broad low strain-rate expanses11,12,13,14,15 has become somewhat routine in mantle convection studies. However, remaining challenges include but are not limited to the modelling of the one-sided convergent boundaries that are the norm on Earth16,17 and the obtaining of a high-degree of toroidal power in the surface velocity field18,19,20.

In the Earth’s surface velocity field, toroidal power is largely generated by the occurrence of conservative (transform) plate boundaries21,22 and oblique subduction at convergent margins; features that require modelling with a 3D geometry. Moreover, in contrast to the oceanic trenches, the divergent boundaries that bisect the Atlantic ocean, circumscribe Antarctica and generate new ocean-floor in the south Pacific are characterized by assemblages of alternating spreading rifts and strike-slip segments (for example, ref. 23). (Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the segmentation structure of ridges in the South Pacific and South Atlantic, revealed by overlaying bathymetry and vertical gravity gradient grids24.) Oceanic ridges and transform faults, thus combine to form plate boundaries that exhibit a fundamentally different construction from the continuous arc-like segments17 that delineate convergent plate boundaries. A ubiquitous feature of plate tectonics that realistic mantle convection models must reproduce is, therefore, the presence of spreading boundaries that are distinguished from convergent boundaries by a connected-segment structure.

Previous studies of convection in momentum-free fluids confined to planetary-mantle-emulating spherical shells have shown that combining a mechanism for introducing zones of lithospheric weakness with a temperature- and depth-dependent viscosity results in surface mobility and that the number of distinct rigid regions (i.e., plates) is affected by each of the factors determining the fluid’s viscosity structure. Focussing of the surface deformation into narrow bands that comprise plate boundaries is facilitated by introducing a stress dependence for the rheology that may itself be dependent on depth25,26. The oceanic thermal lithosphere arising from mantle convection is formed from the upper thermal boundary layer of the convecting system and its thickness is inherently dependent on the convective vigour (quantitatively expressed by an effective Rayleigh number). The latter quantity imposes a length scale on the model lithosphere relative to the system depth. Accordingly, the attainment of plate boundary structures with terrestrial plate boundary length scales (including the appearance of spreading segments with offsets) may require plate thicknesses characteristic of the Earth. However, the length of ridge segments24 and transform faults in the oceans ranges from tens to hundreds of kilometres, or alternatively from fractions of the plate thickness to more than an order of magnitude greater than the mean thickness.

Implementing global dynamic models in a 3D spherical geometry, we investigate the influence of lithospheric rheology on the surface velocity field with specific attention on the form of zones of localized surface deformation. Recently, rare but transient transform motion was manifested on a boundary appearing in a 3D global mantle convection model4, suggesting that enduring networks of ridges and transform boundaries might be formed for some set of model parameters. Here, we examine the influence of yield stress magnitude and depth dependence in high-resolution vigorously convecting mantle models and find examples of a self-organization featuring significant distinction between the configuration of convergent and divergent surface features that reproduces the structure of these boundary types on the Earth. Specifically, enduring transform-like offsets appear along the divergent plate boundaries while convergent boundaries appear as smooth constructs lacking offsets. In addition, we investigate the deep interior of a system featuring transform-like offsets along divergent boundaries and explore whether active upwellings play a required role in determining the location of plate-generating boundaries, as well as examining the nature of heat flow at these boundaries.

Results and discussion

Analyzing the role of yield stress in the formation of transform-like offsets

Figure 1a shows a snapshot of the temperature field (first column) and three corresponding snapshots of the viscosity field at a depth of 12 km below the surface in a mantle convection calculation featuring a core of radius 3480 km and surface defined by a radius of 6370 km (terrestrial values). The viscosity field images are obtained by rotating a single rendering through different viewing angles (ϕ) around the arbitrarily defined north-south determined by the orientation of the panels in the column marked 0° in ϕ. The depicted temperature field has a minimum (surface) value of 270 K and super-adiabatic core-mantle boundary temperature of 2770 K. The panel shown in the first column includes a hot isosurface that captures the distribution of plume-like structures. At least two of these features span the mantle from core to surface.

Thermal field (first column) and viscosity field (remaining columns) variation in response to yield stress values. Rows a–e show snapshots from four time-dependent calculations (rows c, d are from the same calculation). In columns 2–4 different viewing angles are shown (the different columns) for the time corresponding to the first column. Rotation of the spheres in columns 3 and 4 is around the north-south axis defined by the viewing angle of the second column and is through an angle of approximately ϕ. Asterisks on specific viscosity field panels indicate that the viewing angle in that column corresponds to the position used to render the temperature field in the first column. In a the non-dimensional surface yield stress is 2 × 106 (11 MPa) and increases linearly over the top 2% of the mantle thickness to a value of 2 × 107 (110 MPa). In b the non-dimensional surface yield stress is 1.5 × 107 (85 MPa) and increases linearly over the top 2% of the mantle thickness to a value of 2 × 107 (110 MPa). In c, d the surface yield stress is uniform with depth with a value of 2 × 107 (110 MPa). Panel d is from the same calculation as row (c) but at a time 350 Myr later. In e the yield stress is uniform with depth with a value of 3 × 107 (160 MPa). The panel in the green box is the viscosity field shown in (e) viewed from over the north pole. The cyan horizontal line indicates where the sphere would be sliced in order to obtain the thermal field image in the first column of (e). The thermal isosurfaces in the first column have a non-dimensional super-adiabatic temperature of 0.85. The viscosity fields are depicted 12 km below the surface of the 2890 km deep mantle. Black and red arrows annotate features described in the text. Colour bars corresponding to the superadiabatic temperature and the viscosity fields are located at the bottom of the figure. The scale on the viscosity colour bar shows multiplicative factors for the reference viscosity 4.5 × 1019 Pa ⋅ s. The scale for the temperature fields is in fractions of the core-mantle-boundary temperature, 2500 °C.

With the 11 MPa surface yield stress value specified in this calculation (increasing to 110 MPa at a depth of 60 km), the surface viscosity field is characterized by multiple bands of focussed weakness that cut through surface regions of comparatively higher viscosity. Although the emergence of regions of broad high viscosity plate-like features is apparent in some locations, the morphology of the weak perimeters of these regions greatly differs from the structure of terrestrial oceanic ridges and high viscosity regions are not enclosed within weak boundaries in general.

In Fig. 1b the surface yield stress has been increased to 82.5 MPa while the yield stress below 60 km remains unchanged from the previous calculation. The increase in the yield stress in the outermost 60 km of the system has reduced the number of individual bands of weakness while increasing the length of most of these segments so that the majority connect to form low viscosity boundaries around stiff interiors that comprise roughly 10 model plates. Of specific note, convergent boundaries are generally characterized by arc-like surface geometries, while divergent boundaries are less curved and in some places exhibit long connecting segments characterized by high toroidal power (e.g., lower southern hemisphere of the right-most column where indicated by the red arrow).

Figure 1c presents a similar set of temperature and viscosity field snapshots to those shown in Fig. 1b but for a case where the surface yield stress has been increased to 110 MPa and is invariant with depth. The temperature field (in the first column) reveals the presence of a cold downwelling that coincides with the weak band at 9 “o’clock” (indicated by the black arrows) in the snapshot indicated by an asterisk (180∘ in ϕ) and marks a zone of surface convergence. This band can be seen to extend more than 10,000 km around the surface in the third column of the figure (90° in ϕ) and does not exhibit any discontinuities at the surface. Figure 1d depicts fields from the same calculation as Fig. 1c after the passage of 350 Myr. (Supplementary Fig. 2 presents snapshots of the viscosity field at different times to illustrate the migration of the plate boundaries that occurs between rows c and d of Fig. 1.) The increased lithospheric yield stress in this calculation has the effect of increasing the length of the continuous bands of surface weakness that encompass the (now broader) strong regions. In addition, the weak bands that correspond to margins associated with surface divergence are now interrupted by the regular appearance of right-angled discontinuities associated with high shear, such that spreading boundaries have become segmented.

In Fig. 1e corresponding temperature field and surface viscosity field is shown from a third calculation, in which the specified yield stress at all depths has been increased by 50% over the strength specified in 1c and 1d. Although weak bands in the uppermost layer of the modelled mantle have become highly focussed by the increase, the total number of distinct regions (model plates) lying between the boundaries is diminished to just four features. The lowermost frame (90° in theta) shows a view from above the relative north pole of the other panels, revealing that the weak boundaries converge to an approximate quadruple junction and that the surface weak zones are arranged in an almost meridional configuration separating four similarly sized model plates. Although the number of plate-like features is lower than on the Earth and the convergence on similar sized plates differs from the characteristics of terrestrial plates, some of the boundary dichotomy of the calculation shown in Fig. 1c, d has persisted. Namely, the convergent boundaries are unbroken, while the divergent boundaries form a chain of linked offset spreading segments.

In Supplementary Fig. 3, we plot the laterally averaged temperature and horizontal velocity magnitude as a function of depth for the four cases shown in Fig. 1 and two additional cases. (Also plotted are profiles of the corresponding yield stresses of each case.) One additional case features a uniform yield stress of 55 MPa and is characterized by a cooler interior while also exhibiting the emergence of offsets along sections of divergent plate boundary). Another case shown has a uniform yield stress of 38.5 MPa but a factor of five increase in the reference viscosity (and therefore a reduction in the Rayleigh number). The lower Rayleigh number case converges on a stagnant-lid solution. The profiles from cases in Fig. 1 show that in the calculations featuring a depth-dependent yield stress, the increase in yield stress with depth is confined to roughly the top 50% of the upper thermal boundary layers. In addition, with the exception of the lower Rayleigh number case, the profiles show that temperatures below the thermal lithospheres warm with increasing surface yield stress. This finding is consistent with the trend indicated in Fig. 1 towards a smaller number of plates and therefore reduced cooling by fewer downwellings (for example, ref. 27). All cases presented in Fig. 1 have their maximum velocities at the surface. In addition, the case with the most developed transform offsets (the cyan curve) has the least vertical shear throughout the top layer corresponding to the plates. However, vertical shear of the horizontal velocities is prominent below the plates.

The emergence of offsets on divergent plate boundaries

The left column of panels in Fig. 2 depict snapshots of the detail in the divergence of the velocity field in an isolated region from the calculation presented in Fig. 1c, d. Global field snapshots incorporating this part of the near-surface field are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. (Snapshots of the divergence and radial vorticity corresponding to all cases shown in Fig. 1 are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.) The distinctly different form of the convergent (blue) and divergent (red) plate boundaries is especially apparent in these figures. The sequence in Fig. 2 shows that perpendicular segments form along a divergent boundary that is initially much more smooth and continuous. As the boundary evolves, right-angled offsets form and divergence intensifies in sections that are approximately orthogonal to other segments where divergence diminishes by comparison.

Sequence of non-dimensional velocity field divergence snapshots (left column) and corresponding radial vorticity fields (right column). The fields shown are the regions inside the green boxes drawn on the global field snapshots presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. The negative vorticity in the example circled-location is caused by relative plate motion in the directions indicated by the white arrows.

The right column of Fig. 2 shows the magnitude of the radial component of the vorticity at the same times and at the same depth as the divergence fields in the figure. Positive vorticity corresponds to counter-clockwise rotation about a radial pointing vector. Negative vorticity denotes clockwise rotation around the associated location. Accordingly, the appearance of the green bands along the offsets connecting divergent segments are consistent with locations like that marked by the circle added to the final panel of Fig. 2 (if such points are on a boundary dividing regions moving in the directions indicated by the annotated white arrows). The complete sequence of panels in Fig. 2 illustrates that, at least in the case of an exisiting, lengthening, divergent plate boundary, the boundary propagates and then takes on a segmented form featuring transform-like offsets, rather than forming with offsets from the time of its initial appearance. Moreover, the length scale of the offsets ranges from a few tens of kilometres to distances on the order of 1000 km, in-keeping with the spectrum of transform-fault length scales observed on the oceanfloor (for example, ref. 28).

Heat flux and the symmetry of surface spreading

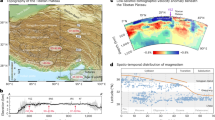

Figure 3 presents the detail 12 km below the surface in a region of divergence in the calculation depicted in Fig. 2. However, to emphasize the global distribution of the transform-like offsets, the region depicted in this figure is almost diametrically opposed from that depicted in Fig. 2, (Supplementary Fig. 4 indicates the relative location). The timing of this snapshot precedes the snapshot in Fig. 1d by 100 Myr. In Fig. 3a a radial heat flux map is contoured to illustrate the degree of symmetric motion relative to the spreading boundary and the discontinuity of high heat flux segments (red) along the boundary. The uppermost high heat flux segment terminates where it meets a horizontal trending (dark blue) arc-like feature corresponding to a surface convergent boundary. In general, the high heat flux features trend in parallel in the region depicted and are similar in length to the orthogonal offsets that separate adjacent segments. Heat flux along the offsets is far less than the heat flux from the high divergence segments.

a Non-dimensional radial heat flux at a depth of 12 km in the vicinity of a system comprised of divergent segments offset by orthogonal fractures. The snapshot shown is taken from the case depicted in parts (c) and (d) of Fig. 1, 100 Myr prior to the timing of Fig. 1d. The pink box annotated on Supplementary Fig. 4 outlines the region shown in this figure. (This region is almost diametrically opposed from that shown in Fig. 2.) Heat flux values are binned such that the interval of values spanned by each colour (from red to cyan) corresponds to an equal length time period based on a conductive heat flow model. Dimensional values, in milliWatts m−2, are obtained by multiplying the colour bar scale by 3.8. The deepest blue, corresponding to the lowest values of heat flux, delineates a convergent boundary. (Small magnitude negative values are possible in the system interior.) The white horizontal bars are of equal length and indicate the orthogonal distance to divergent boundary segments that six parcels of fluid would travel if released at the divergent boundaries at a common time. b Variation in viscosity for the region corresponding to (a). The dimensional viscosity values are obtained by multiplying the values marked on the colour bar by the reference viscosity, 4.5 × 1019 P ⋅ s. c The non-dimensional divergence of the velocity field corresponding to the region shown in (b) and the length scale applicable to all three panels. d The radial vorticity magnitude corresponding to the above panels.

The white horizontal bars included in Fig. 3a are 500 km in length. They indicate the distance on the surface that six simultaneously released, uniform velocity, markers would travel given a direction orthogonal to the divergent boundary. (It is assumed that three markers move to the right and three to the left.) The white bars to the right of the high heat emitting axial features extend well past the cyan contour in comparison to those on the left and therefore indicate that the model plate on the left is moving away from divergent segments more quickly than the plate on the right. That is, the spreading is not symmetric. The roughly constant length of the extension of the white bars beyond the cyan contour indicates that the spreading motion away from the divergent segments in the easterly direction (right plate) is effectively uniform and the almost right-angled offsets in the contour indicate that the motion is very close to being orthogonal to the strike of the divergent segments. On the left plate the departure of the angles in the cyan contour from 90∘ indicates the plate on the left is either not moving away from the heat emitting axes at right angles or has been changing the direction of its motion. Motion of the plate away from the divergent segments on a non-ninety degree bearing may also explain why the white bars appear to extend further beyond the cyan contour in a trend from top to bottom in the figure.

Figure 3b maps the viscosity on the surface corresponding to Fig. 3a and emphasizes sharp discontinuities in the low viscosity bands that correspond to the high heat flux regions of Fig. 3a and the contrast with the continuous arc-like band corresponding to the low viscosity convergent boundary. Along the spreading boundary, we find an alternating pattern in the second invariant of the stress tensor such that maxima and minima occur at offsets and divergent segments, respectively. The maxima are explained by shear associated with the adjacent motion of the model plates. The majority of the discontinuities in the high heat flux axes are coincident with weak linear bands that are strikingly aligned at 90° angles to the lower viscosity bands marking high heat flux segments. The comparatively diagonal boundary in the lower right is also comprised of alternating divergent segments and orthogonal offsets required by approximately uniform plate motion.

Figure 3c shows the divergence of the velocity field on the same surface as the viscosity field plotted in panel b. The blue arc corresponds to the focussed convergence associated with plate consumption. The linear red features correspond to axial spreading that produces the high heat flow found in panel a. Relative to the spreading axes, the divergence reduces by orders of magnitude along the discontinuities in the spreading sections. However, divergence does not vanish along orthogonal segments that connect the divergent axes.

Figure 3d illustrates the vorticity along the spreading boundary and shows how offsets in the chain of divergent segments are connected by offsets with an associated positive vorticity, as required by the adjacent plate motion, when the divergent sections trend from east-to-west in a southerly progressing direction rather than west-to-east.

Mantle plume positions in relation to the location of surface divergence

The correlation of convergent plate boundaries with the descent of tectonic plates into the Earth’s interior, in the form of cold subducted slabs, is a core tenet of the plate tectonics paradigm and is required as a corollary to the theory of mantle convection. Subducted slabs are the cold downwellings of the convecting system. However, far less evident in terms of their connection to surface features, is the role that hot mantle plumes may or may not play in determining the location of divergent plate boundaries (for example, refs. 29,30).

In Figure 4, four views are shown at the time corresponding to Fig. 1d. Panels in the left column of Fig. 4 depict the core enveloping hot isosurface of non-dimensional temperature 0.85 and cold isosurfaces of temperature 0.5. In order to view the interior of the temperature field, the top 5% of the mantle depth has been omitted from the rendering of the cold isosurface, leaving just the cold, high viscosity, downwelling slabs visible and effectively removing the plates. The hot isosurface contorts into numerous upwellings that are predominantly limited to lower mantle activity. However, some plumes (two are identified in the figure at the time shown, marked A and B) traverse the entire mantle depth to arrive at the base of the thermodynamically formed lithosphere. At a depth of 12 km we incorporate images of the linear features determined by the highest absolute values in the divergence field in order to show the locations of plate boundaries. Negative valued divergence is shown in cyan and positive is shown in bright yellow. The latter lineations correspond to the divergent spreading boundaries described in previous figures. To clarify the locations of the divergent boundaries relative to the mantle upwellings, in the right column of Fig. 4, we show the full divergence field at a depth of 12 km. The global view of the divergent (red) boundaries indicates multiple transform-like offsets in spreading boundaries that stretch for tens of thousands of kilometres, in analogue with the structure of terrestrial oceanic ridges.

Four viewing angles are shown, corresponding to the case presented in Fig. 1c, d. All panels in this figure are from the same time as Fig. 1d. The indicated rotation angles ϕ are as defined in Fig. 1. In the left column, (panels a, c, e, g, with rotation angles of 0, 90, 180 and 270 degrees) isosurfaces are depicted for non-dimensional super-adiabatic temperatures of 0.85 (red) and 0.4 (blue), rendering hot plumes rising from the core-mantle-boundary and cold slabs sinking below convergent boundaries. The top 5% of the thermal field is removed (effectively removing the model plates at the surface) in order to allow viewing into the interior. Two hot plumes that reach the base of the lithosphere are marked A and B in the left column. Arc-like cyan features are shown at a depth of 12 km and correspond to regions with a divergence less than −3 × 104. Similarly, yellow lineations show regions at 12 km depth with a divergence greater than 3 × 104. In the right column (panels b, d, f and h, with rotation angles of 0, 90, 180 and 270 degrees) the full divergence field is depicted at a depth of 12 km for viewing angles corresponding to the left column panels. The full range of values in the divergence fields is indicated in the colour bar. (Alternative viewing angles are included in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7.).

At the time depicted in Fig. 4, the boundaries associated with divergence are not underpinned by active upwellings (i.e. mantle plumes) in any of the viewing angles examined. Instead, the divergent boundaries in the calculation are passive features overlying relatively inactive regions of the modelled mantle. Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 present snapshots depicting the evolution of plumes A and B illustrating their sub-lithospheric locations relative to the positions of overlying divergent plate boundaries. Plume A, in particular, lies far from any divergent boundaries while plume B slowly migrates further away from an overlying divergent boundary as time passes.

The morphology of the divergent boundary appears to be determined by a combination of the spherical shell geometry and the stress induced on the viscous lithosphere by the cold sinking material attached to the associated plate at convergent boundaries. The sheet-like downwellings are not one-sided in nature (possibly due to the absence of a stress-free surface boundary16,17) but nevertheless emulate the structure, buoyancy distribution and viscous coupling that is the dominant driver of plate motion and they, therefore, provide the source of forcing required to investigate the effect of stress on the model lithosphere at the divergent boundaries. Over a prolonged period, we thus find a system that features a convecting mantle characterized by slab emulating cold sheet-like downwellings, a small number of intraplate located hot mantle plumes and passive spreading plate boundaries that incorporate regularly appearing transform fault-like offsets. (We also find that approximately half-a-dozen plate-like surface regions exist at most times in the case we focus on in Figs. 2–4.)

Comparison of model characteristics to the Earth

The recurring appearance of transform faults21 is a ubiquitous feature along mid-ocean spreading axes. The faults explain the existence of ocean floor fracture zones and the distribution of seismicity along and adjacent to the Earth’s divergent plate boundaries. The physical need for the presence and arrangement of the faults is not certain (for example, ref. 24) but likely exists because it reduces the net viscous dissipation in the system20,31. In the mantle convection calculations presented here, the appearance of a remarkably similar structure of transform-like offsets and linear divergent segments to those found along the Earth’s ridge axes is obtained. The emergence of this arrangement can allow for plate motion to occur on a spherical surface so that plate velocity is approximately orthogonal to the strike of bounding spreading centres. The mantle convection calculation that we highlight includes dynamically originating extremely stiff plate-like caps formed by a highly temperature-dependent viscosity, separated by very narrow and focussed weak boundaries resulting from a yield-stress dependence of the viscosity. A network of passive divergent and transform-like segments accommodates surface motion that is similar in nature to sea-floor spreading. Surficial divergence is not forced by underlying deeply originating upwellings (mantle plumes) but instead originates from the remote forcing associated with subduction such that the high viscosity model lithosphere acts as a stress guide32,33. In addition to the absence of one-sided subduction, the number of distinct plate-like regions that we obtain (about six to eight large plates at most times) is roughly half of the number currently found on Earth (for example, refs. 34,35). The number of plates formed in other studies has been shown to be sensitive to the magnitude of the yield stress36, as is indicated by the results depicted in Fig. 1. Accordingly, the numbers of plates could potentially rise with a relatively small decrease to the yield stress magnitude or a change in the depth dependence of the yield stress. The role of mantle viscosity structure, as well as Rayleigh number, may also have an influence on the total number of plates obtained in the cases described. The influence of the contrast in upper and lower mantle viscosity37 impacts the dominant wavelength of the convective planform and, therefore, the geotherm38. Accordingly, lithospheric thickness is influenced by the mantle’s viscosity profile and, by extension, so would be the dynamics of the plate boundaries. Another impact on the number of plates and boundary structure obtained could be the absence of model continent cratons, which have been shown to focus stress on their margins (for example, refs. 14,39,40,41) and may therefore increase the number of convergent boundary segments. Perhaps similarly related, we note that some plate interiors do not appear to be enclosed by tightly focussed plate boundaries at all times (see Supplementary Fig. 8). (Similar observations have been discussed previously4.) However, this finding has analogues on the Earth. For example, the division between the North and South American plates extending from the Caribbean to the mid-Atlantic ridge is not sharply defined by a boundary as distinct as those associated with transform faults, subduction or a mid-ocean ridge system. Supplementary Figure 9 shows the reduced seismicity and absence of such clear boundary types at another location, the south-east limit of the Philippine Sea Plate (PSP). There, the Ayu trough, a plate accretion site42,43, divides the PSP from the Caroline Plate44 (which itself has a disputed distinctness and a proposed eastern boundary undelineated by clear lithospheric rupture45. Other possible terrestrial examples of the weakly focussed plate boundaries in our model include the south-west boundary of the Scotia plate and the division between the African and European plates west of the Mediterranean. We also find that the model plates obtained can feature weak cross-cutting bands that can terminate in central plate interior regions or span a plate with a relative weak zone that is neither as stiff as the surroundings nor a clearly developed boundary. Such regions may be similar in nature to the Indian Ocean floor spanning the three-component Indo-Australian complex (for example, refs. 46,47) that encompasses the diffuse zone coinciding with the junction of distinct Indian, Australian and Capricorn plates in kinematic models48,49,50.

Summary

Plastic yielding in a spherical shell mantle convection model featuring a highly temperature-dependent viscosity, internal and basal heat sources representative of radiogenic mantle heating and secular cooling of the Earth’s core, respectively, and a factor of 30 increase in viscosity in the lower mantle, were found to be sufficient requirements to obtain the distinct structure of oceanic ridge systems characterized by linear spreading segments offset by transform faults. The modelling of melt was not included in our calculations (for example, ref. 36) and is, therefore, not a necessary requirement for obtaining the spreading centre structure described. Through systematically varying yield stress profiles across the model lithosphere, we find that convergent and divergent features transition from being arc-like, with a length scale comparable to mantle depth (Fig. 1a), to becoming longer, often terminating at triple junctions (Fig. 1b). Concurrently, we find that while convergent features generally remain arc-like, divergent boundaries become more linear. Upon reaching a surface yield stress of some threshold value (which in this study we found to be comparable to the interior value) divergent boundaries break into segments that tend to align normal to plate motion and linear offsets form to join these segments. The linear offsets are dominated by much stronger strike-slip motion (radial vorticity) and lower divergence than the segments that they connect (Fig. 1d). At higher yield stresses, the length spectrum of the transform features becomes more limited (Fig. 1e) and the number of distinct plates reduced. Previous studies (for example, refs. 13,25,51) have shown that stagnant-lid convection is eventually obtained for increased yield stress. Correspondingly, we find that decreasing the Rayleigh number results in stagnant-lid convection. In summary, we find that in the same way that increasing yield stress produces a systematic change in regime from mobile surface to sluggish lid to stagnant-lid, given a mobile surface starting point, a refinement of model yield stress in the upper thermal boundary layer of these spherical systems produces a surface that features staggered offsets along divergent boundaries. We find that at least some divergent boundaries form as roughly linear features and then evolve offsets to accommodate divergent segments lying more orthogonal to plate velocity (Fig. 2). Our findings support the premise that plate tectonics is a corollary of the deeper reaching influences of mantle convection (for example, refs. 1,3,4,32) while demonstrating that divergent plate boundaries are passive and not, in general, a manifestation of the upwellings of convection cells. However, we find passive divergent boundaries and deep rooted mantle plumes coexist. Thus the interaction of plumes with divergent boundaries remains a plausible scenario (for example, refs. 29,52) but is not found to be necessary to generate divergent boundary formation or growth.

Methods

Governing equations

Mantle convection is modelled in a spherical shell geometry using the finite volume code STAGYY53. The dimensionless equations for mass, momentum and energy conservation are solved in a bimodally heated infinite Prandtl number Boussinesq fluid, requiring

and

where u is velocity, η is dynamic viscosity, P is the non-hydrostatic pressure, T is temperature, t is time, H is the non-dimensional internal heating rate, and RaT is a reference Rayleigh number. The governing Eqs. (1)–(3) are non-dimensionalized with the use of a thermal diffusion time scale. In addition, the non-dimensional viscosity \(\eta =\bar{\eta }/{\eta }^{* }\), where \(\bar{\eta }\) represents the dimensional field and η* is a dimensional reference viscosity with a non-dimensional value of 1.0.

The reference Rayleigh number,

incorporates the dimensional quantities d, the thickness of the mantle, ΔT = [Tb − T0] (where Tb is the super-adiabatic temperature at the isothermal core-mantle-boundary and T0 is the surface temperature), g, the gravitational acceleration, α, the thermal expansivity and κ the thermal diffusivity. This study assumes the latter three quantities are uniform throughout the mantle. All non-dimensional length and distance measurements are multiplicative factors of the mantle depth.

A dimensional linearized equation of state

is utilized to obtain the system of partial differential Eqs. (1)–(3) so that our calculations implicitely require that ρ0 = ρ(T0) where T0 is the surface temperature.

We implement a temperature-dependent viscosity coupled with viscoplastic yielding. A non-dimensional Arrhenius-type law is used to model the temperature-dependence, where

is the non-dimensional viscosity determined by temperature and Ea is an effective non-dimensional activation energy that determines the magnitude of the thermal viscosity contrast, ΔηT (which is 3.2 × 106 in this study).

Pressure and stress are non-dimensionalized in the calculations through division by η*κd−2. The non-dimensional yield-stress, σyield, is obtained by specifing a surface yield stress, σsurf, and a sub-lithospheric constant valued yield stress, σmantle, that determines the behaviour of the mantle below a prescribed non-dimensional depth of dl (corresponding to 60 km in this study). The yield stress is either set to a constant or increases linearly with depth from the surface until reaching the depth dl. A uniform yield stress is prescribed by setting the value of σsurf equal to that of σmantle. In general, the yielding behaviour satisfies

where \({d}^{\prime}\) is the non-dimensional depth below the surface.

Yielding is incorporated in the solution of Eqs. (1)–(4) by the introduction of a yield viscosity that is obtained through the relationship:

where \(\dot{\epsilon }\) is the second invariant of the strain rate tensor,

From these definitions, a composite viscosity, ηcomp, is obtained to simultaneously account for the impact of the stress and temperature-dependent rheologies, where

An intrinsically depth-dependent viscosity is obtained by specifying a factor 30 increase in viscosity below a depth corresponding to the 660 km transition to Bridgmanite54.

Initial condition and resolution

Supplementary Figure 10 displays a snapshot slice of the three-dimensional temperature and viscosity field used for the initiation of all calculations. The initial condition features a RaT of 1 × 109, H of 30, ΔηT of 3.2 × 106 and a uniform yield stress, σyield, of 1 × 106 (5.4 MPa). The parameters chosen for the initial condition were determined from a study presented previously13. The origin of the initial condition for the calculations in that study is describe therein. The values for all of the parameters used in this study are given in Table 1 of the Supplementary material. Only the yield stress values are varied. The guiding choice for the parameters chosen for the initial condition is that they were found to result in surface mobility and focussed plate boundaries in two-dimensional spherical annulus calculations.

The initial condition, as well as all other calculations presented in this study, are obtained in a spherical shell geometry utilizing a yin-yang grid with a resolution of 96 × (768 × 256) × 2. The grid spacing is refined in the thermal boundary layers and in the vicinity of the 660 km-depth step in viscosity.

Convergence to results presented in this study

The findings presented here were determined to have reached a statistically steady state when the time averaged difference in the surface and core-mantle-boundary heat flows:

equates with the non-dimensional internal heating rate. In the preceding, F0 and Fb are the non-dimensional surface and basal heat flux values and f is the ratio of core to planetary radius. For all calculations presented f has an Earth-like value of 0.547. The snapshots presented in Figs. 1–4 were obtained once the value of (11) obtained a time averaged value that indicated there was no long term heating or cooling occurring in the systems analysed.

Data availability

All the data presented in the figures can be accessed at the University of Toronto’s Dataverse repository. https://dataverse.scholarsportal.info/privateurl.xhtml?token=384a40c4-209a-4e00-8cd1-2bb8d8732080

Code availability

The convection code StagYY is the property of P.J.T. and Eidgeniössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zürich. Researchers interested in using StagYY should contact P.J.T. (paul.tackley@erdw.ethz.ch).

References

Bercovici, D. The generation of plate tectonics from mantle convection. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 205, 107–121 (2003).

Lowman, J. P. Mantle convection models featuring plate tectonic behavior: an overview of methods and progress. Tectono 510, 1–16 (2011).

Coltice, N., Gérault, M. & Ulvrová, M. A mantle convection perspective on global tectonics. Earth-Sci. Rev. 165, 120–150 (2017).

Coltice, N., Husson, L., Faccenna, C. & Arnould, M. What drives tectonic plates? Science Adv. 5, eaax4295 (2019).

Kreemer, C., Holt, W. E. & Haines, A. J. An integrated global model of present-day plate motions and plate boundary deformation. Geophys. J. Int. 154, 8–34 (2003).

Moresi, L. & Solomatov, S. Mantle convection with a brittle lithosphere: thoughts on the global tectonic styles of the Earth and Venus. Geophys. J. Int. 133, 669–682 (1998).

Richards, M. A., Yang, W.-S., Baumgardner, J. R. & Bunge, H.-P. Role of a low-viscosity zone in stabilizing plate tectonics: implications for comparative terrestrial planetology. Geochem., Geophys., Geosyst. 2, 1026 (2001).

Trompert, R. & Hansen, U. Mantle convection simulations with rheologies that generate plate-like behaviour. Nature 395, 686–689 (1998).

Tackley, P. J. Self-consistent generation of tectonic plates in time-dependent, three-dimensional mantle convection simulations, 1: pseudoplastic yielding. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 1, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000GC000036 (2000).

Stein, C., Schmalzl, J. & Hansen, U. The effect of rheological parameters on plate behaviour in a self-consistent model of mantle convection. Phys. Earth. Planet Int. 142, 225–255 (2004).

Zhang, S. & O’Neill, C. The early geodynamic evolution of Mars-type planets. Icarus 265, 187–208 (2016).

Nakagawa, T. & Spiegelman, M. W. Global-scale water circulation in the Earth’s mantle: implications for the mantle water budget in the early Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 464, 189–199 (2017).

Langemeyer, S. M., Lowman, J. P. & Tackley, P. J. The sensitivity of core heat flux to the modeling of plate-like surface motion. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 1282–1308 (2018).

Ulvrova, M. M., Coltice, N., Williams, S. & Tackley, P. J. Where does subduction initiate and cease? A global scale perspective. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 528, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.115836 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Effects of the compositional viscosity ratio on the long-term evolution of thermochemical reservoirs in the deep mantle. Gephys. Res. Lett. 46, 9591–9601 (2019).

Crameri, F., Tackley, P. J., Meilick, I., Gerya, T. V. & Kaus, B. J. P. A free plate surface and weak oceanic crust produce single-sided subduction on Earth. Geophy. Res. Lett. 39, L03306 (2012).

Crameri, F. & Tackley, P. J. Spontaneous development of arcuate single-sided subduction in global 3-D mantle convection models with a free surface. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 5921–5942 (2014).

Minster, J. B. & Jordan, T. H. Present-day plate motions. J. Geophys. Res. 83, 5331–5354 (1978).

Hager, B. H. & O’Connell, R. J. Subduction zone dip angles and flow driven by plate motion. Tectono 50, 111–133 (1978).

Bercovici, D. On the purpose of toroidal motion in a convecting mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 3107–3110 (1995).

Wilson, J. T. A new class of faults and their bearing on continental drift. Nature 207, 343–347 (1965).

Olson, P. & Bercovici, D. On the equipartition of energy in plate tectonics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 18, 1751–1754 (1991).

Gerya, T. Origin and models of oceanic transform faults. Tectono 522-523, 34–54 (2012).

Sandwell, D. T. & Smith, W. H. F. Global marine gravity from retracked Geosat and ERS-1 altimetry: Ridge segmentation versus spreading rate. J. Geophys. Res. 114, B01411 (2009).

Van Heck, H. J. & Tackley, P. J. Planforms of self-consistently generated plates in 3D spherical geometry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035190 (2008).

Foley, B. J. & Becker, T. W. Generation of plate-like behavior and mantle heterogeneity from a spherical, viscoplastic convection model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys.10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GC002378 (2009).

Monnereau, M. & Quéré, S. Spherical shell models of mantle convection with tectonic plates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 184, 575–587 (2001).

Fowler, C. M. R. in Principles of Geologic Analysis (eds. Roberts, D. G. & Bally, A. W.) 732–818 (Elsevier, 2012).

Ito, G., Lin, J. & Graham, D. Observational and theoretical studies of the dynamics of mantle plume-mid-ocean ridge interaction. Rev. Geophys. 41, 1017–n/a (2003).

Arnould, M., Coltice, N., Flament, N. & Mallard, C. Plate tectonics and mantle controls on plume dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 547, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116439 (2020).

Gable, C. W., O’Connel, R. J. & Travis, B. J. Convection in three-dimension with surface plates: generation of toroidal flow. J. Geophys. Res. 96, 8391–8405 (1991).

Stern, R. J. The evolution of plate tectonics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170406 (2018).

Stern, R. J. & Gerya, T. Subduction initiation in nature and models: A review. Tectono 746, 173–198 (2018).

Bird, P. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys.4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000252 (2003).

Harrison, C. G. A. 2016. The present-day number of tectonic plates. Earth. Planet. Sp. 68, 37 (2016).

Mallard, C., Coltice, N., Seton, M., Mueller, R. D. & Tackley, P. J. Subduction drives the organisation of Earthas tectonic plates. Nature 535, 140–143 (2016).

Richards, M. A., Bunge, H.-P. & Baumgardner, J. R. Effect of depth-dependent viscosity on the planform of mantle convection. Nature 379, 436–438 (1996).

Lowman, J. P., King, S. D. & Gable, C. W. The influence of tectonic plates on mantle convection patterns, temperature and heat flow. Geophys. J. Int. 146, 619–636 (2001).

Rolf, T. & Tackley, P. J. Focussing of stress by continents in 3D spherical mantle convection with self-consistent plate tectonics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL048677 (2011).

Coltice, N., Rolf, T., Tackley, P. J. & Labrosse, S. Dynamic causes of the relation between area and age of the ocean floor. Science 336, 335–338 (2012).

Rolf, T., Capitanio, F. A. & Tackley, P. J. Constraints on mantle viscosity structure from continental drift histories in spherical mantle convection models. Tectono. 746, 339–351 (2018).

Fujiwara, T. et al. Morphological studies of the Ayu Trough, Philippine Sea—Caroline Plate Boundary. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 109–112 (1995).

Ribeiro, J. M. et al. Asthenospheric outflow from the shrinking Philippine Sea Plate: Evidence from Hf-Nd isotopes of southern Mariana lavas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.08.022 (2017).

Weissel, J. K. & Anderson, R. N. Is there a Caroline plate? Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 41, 143–158 (1978).

Zahirovic, S., Seton, M. & Muller, D. The Cretaceous and Cenozoic tectonic evolution of Southeast Asia. Solid Earth 5, 227–273 (2014).

Wiens, D. A. et al. A diffuse plate boundary model for Indian Ocean tectonics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 12, 429–432 (1985).

Gordon, R. G. The plate tectonic approximation: plate nonrigidity, diffuse plate boundaries, and global plate reconstructions. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 26, 615–42 (1998).

Royer, J.-Y. & Gordon, R. G. The motion and boundary between the Capricorn and Australian plates. Science 277, 1268–1274 (1997).

Conder, J. A. & Forsyth, D. W. Seafloor spreading on the Southeast Indian Ridge over the last one million years: a test of the Capricorn plate hypothesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 188, 91–105 (2001).

DeMets, C., Gordon, R. G. & Argus, D. F. Geologically current plate motions. Geophys. J. Int. 181, 1–80 (2010).

Weller, M. B. & Lenardic, A. Hysteresis in mantle convection: Plate tectonics systems. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051232 (2012).

Whittaker, J. M. et al. Long-term interaction between mid-ocean ridges and mantle plumes. Nat. GeoSci. 8, 479–483 (2015).

Tackley, P. J. Modelling compressible mantle convection with large viscosity contrasts in a three-dimensional spherical shell using the yin-yang grid. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 171, 7–18 (2008).

Hager, B. H. Subducted slabs and the geoid: constraints on mantle rheology and flow. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 6003–6015 (1984).

Acknowledgements

S.M.L. and J.P.L. are grateful for funding from the NSERC of Canada 1038 (fund: 327084-10). Calculations were performed on the Niagara cluster of the SciNet Consortium. SciNet is funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation under the auspices of Compute Canada; the Government of Ontario; Ontario Research Fund—Research Excellence; and the University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The subject of investigation was identified by discussion that included all three authors. S.M.L. initiated and supervised all calculations, produced all original figures in consultation with J.P.L. and wrote the ‘Methods’ section. The remainder of the paper was written by J.P.L. P.J.T. wrote the computational code used for the calculations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Joseph Aslin.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Langemeyer, S.M., Lowman, J.P. & Tackley, P.J. Global mantle convection models produce transform offsets along divergent plate boundaries. Commun Earth Environ 2, 69 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00139-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00139-1

This article is cited by

-

A rapid tectonic plate reorganization event driven by changes at subduction locations in a mantle convection model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Tectonic modes of mantle convection and their implications for Earth’s tectonic evolution based on three-dimensional numerical simulations

Science China Earth Sciences (2025)

-

Sluggish thermochemical basal mantle structures support their long-lived stability

Nature Communications (2024)