Abstract

Reducing terrestrial carbon emissions is a big challenge for human societies. Ecosystem restoration is predominant to reverse land degradation and carbon loss. Though active restoration of croplands is assumed to increase carbon sequestration more than natural regeneration, it still lacks the robust paired comparisons between them. Here we performed a large-scale paired comparison of active versus natural restoration effects on soil carbon sequestration across China. We found that two restoration strategies consistently enhanced soil carbon relative to croplands, however, the benefits of active restoration versus natural regeneration were highly context-dependent. Active restoration only sequestered more carbon in carbon-poor soils but less carbon in carbon-rich soils than natural regeneration. Moreover, active restoration fixed greater carbon in topsoil but less carbon in subsoil. Overall, these findings highlight landscape context-dependent application of active restoration and natural regeneration, further guiding the efficient management of limited resources to maximize the restoration benefits of carbon sequestration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecosystem restoration is a critical part of any effort to reverse land degradation and sequester excess atmospheric carbon1,2. For example, agricultural lands that are removed from production have the potential to fix significant amounts of soil carbon3, which helps to offset excess CO2 in the atmosphere. However, the strategies of reversing land degradation range from low-cost natural regeneration (natural succession without any management) to high-cost active restoration (i.e., planting species) following cropland abandonment4,5. Given the limited resources to restore degraded lands, managers and policymakers face a tradeoff between total area restored and the per area costs of restoration6. While active restoration is assumed to generally accelerate the recovery of ecosystem carbon and diverse functions7,8,9, a recent global analysis found that simply allowing lands to undergo natural regeneration leads to a faster recovery of primary productivity than active restoration in tropical forests4. This finding suggests that high investment in active restoration may not yield increased benefits of carbon sequestration relative to low-cost natural regeneration.

Currently, it is highly uncertain about how to optimize the return on ecosystem restoration investment10, because previous studies have compared active restoration and natural regeneration impacts by comparing outcomes of different treatments applied at different sites11,12, as opposed to making paired comparisons10. This approach confounds the effects of two restoration strategies with changing environment conditions, leading to large uncertainties in the results. More importantly, we still do not understand the key factors that regulate the effectiveness of active restoration versus natural regeneration for soil carbon sequestration across a range of contrasting environments10. As a result, we lack a general understanding of how to best allocate limited management resources to maximize soil carbon sequestration benefits.

The ‘Grain for Green’ project, initiated by the Chinese government, is one of the largest ecological restoration projects worldwide13. The main aim of this project is to restore cropland into semi-natural ecosystems, such as forest, shrubland or grassland14. Uniquely, many areas in this large-scale project implement both natural regeneration and active restoration at the same site12, allowing us to conduct paired comparisons between these two restoration strategies. The active restoration in this project involves planting or seeding in former croplands, while natural regeneration leaves abandoned croplands to recover on their own15.

Using a unique dataset arising from the ‘Grain for Green’ project, here we performed a large-scale paired comparison (617 observations) of active restoration versus natural regeneration effects on soil carbon sequestration. In these analyses, we assessed the importance of factors that have been found to affect the recovery of soil carbon sequestration following cropland abandonment, including restoration time, climate, ecosystem type, background soil organic carbon (SOC), and soil depth16,17,18,19. Among these factors, we further identified the conditions under which active restoration or natural regeneration yielded the larger soil carbon sequestration benefits. Specifically, we addressed the following two questions. (1) What is the difference between active restoration (i.e., direct seeding and planting) and natural regeneration in terms of soil carbon sequestration benefit? (2) What factors influence the relative benefits of active restoration versus natural regeneration?

Briefly, we found that active restoration only sequestered more carbon than natural regeneration in C-poor soils, and this carbon was stored in topsoil. In contrast, natural regeneration performed better in C-rich or deep soils in terms of soil carbon sequestration benefits. These findings run counter to the canonical view that active restoration is the preferred choice for reversing soil carbon loss, suggesting context-dependent application of active restoration and natural regeneration.

Results

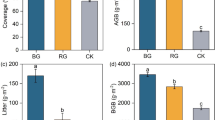

Relative to cropland, both active restoration (40.6%, 95%CI = 25.8%~57.1%) and natural regeneration (38.8%, 95%CI = 18.3–62.9%) consistently enhanced soil carbon storage across all sites in China (Fig. 1). In paired comparison with natural regeneration, active restoration showed a weaker effect (12.7%, 95%CI = 1.9–24.6%) on soil carbon sequestration, but there was a great deal of variations. Across all the studied sites, the effects of background SOC (normalized slope = −0.30) and soil depth (−0.17) were stronger than restoration duration (0.09) and aridity index (0.08) in affecting the difference between active restoration and natural regeneration (Fig. 2). Moreover, background SOC and soil depth showed consistent and significant effects among different ecosystems, but not for restoration time and aridity index (Figs. 3–5). For example, when comparing natural grassland to active forest, low values of time since restoration and site aridity were indicative of higher soil carbon sequestration in natural regeneration, while higher values of these factors resulted in a greater benefit of active restoration. However, these two factors did not affect the difference between two restoration strategies in other ecosystems. These indicated that the divergent effects of active restoration versus natural regeneration mainly depended on background SOC and soil depth.

a Distribution map of restoration studies across China (drawing review No: GS(2016)2929); b Effects of active or natural restoration relative to cropland and those of active versus natural restoration on soil carbon sequestration. The orange bar indicates the mean effects {ln (response ratio)} with their 95% confidence interval (CI). If the 95% CI does not cover zero, it means a significant effect by ecosystem restoration. The light blue one is a box graph indicative of the data outliers, upper limit, third quantile, median, first quantile, and lower limit. SOC background soil organic carbon.

The bar graph indicates the normalized slopes with their 95% confidence interval (CI), because the independent variables were standardized by (observations-mean)/SD. If the 95% CI does not cover zero, it means that the difference of active versus natural restoration changes with these factors. SD standard deviation. SOC soil organic carbon.

Across all the ecosystem types, we found that the threshold of background SOC was 5.1 g kg−1 on average, below which active restoration sequestered more carbon than natural regeneration (Figs. 3–5 and supplementary Figs. 3–4). Conversely, active restoration showed an opposite impact above this threshold. Similarly, we quantified the threshold of soil depth (31.1 cm) on average, deeper than which less carbon was sequestrated by active restoration than natural regeneration. In contrast, restoration of carbon in the topsoil (shallower than 31.1 cm) was greater in actively than naturally restored ecosystems. However, we detected some interactions between background SOC and soil depth on the difference between active restoration and natural regeneration, indicating that these thresholds of background SOC and soil depth were context-dependent (Table 1).

We further tested whether the effects of background SOC and soil depth varied with restoration time or baseline environmental conditions. The results showed no interaction of background SOC or soil depth with restoration time or aridity index on the difference of two restoration strategies (Table 1). Similarly, the effects of soil depth did not change with ecosystem type, while those of background SOC were variable among different ecosystems. These results showed that background SOC and soil depth generally mediated the difference between active restoration and natural regeneration in terms of soil carbon sequestration.

Discussion

This study presents a large-scale paired comparison of active restoration versus natural regeneration effects on soil carbon sequestration across landscapes, as opposed to the design of previous comparisons applied among different sites4,10. Moreover, these previous comparisons did not look into soil carbon sequestration, a major carbon pool due to its size and significance20. While active restoration sequestered more carbon than natural regeneration, the difference was small (12.7%) and highly context-dependent. For example, active restoration sequestered more soil carbon than natural regeneration in C-poor soil, but in C-rich soil natural regeneration provided more carbon storage. Furthermore, active restoration restored more carbon in topsoil, whereas natural regeneration performed better in terms of subsoil carbon sequestration. However, the thresholds of background SOC and soil depth were context-dependent, as indicated by the interactions between background SOC and soil depth/ecosystem type (Table 1). Taken together, these results increase our understanding of how to efficiently restore ecosystems for carbon sequestration benefits, beyond the traditional knowledge of just comparing which restoration method is generally better4,10. These findings highlight landscape context-dependent optimization of ecosystem restoration investment.

While our results partially support the common notion that active restoration results in greater carbon sequestration than natural regeneration following cropland abandonment, this occurs only in C-poor soil, as has been demonstrated by previous restoration studies16,21. For example, active afforestation substantially enhanced soil carbon storage in C-poor soil, but it reduced soil carbon storage in C-rich soil due to higher soil respiration in studies conducted across northern China and heather moorland in Scotland16,22. Furthermore, soil carbon is lower in active plantations than natural forests across global ecosystems21. Taken together, these results imply that natural regeneration may have greater soil carbon sequestration potential in C-rich soil than active restoration.

Plant community diversity may account for some of the differences between natural regeneration and active restoration. Natural regeneration starts with the colonization of abandoned croplands by opportunistic and native species, which results in a more diverse assemblage of locally adapted species than a planted community4. In contrast, active restoration usually uses a single or relatively few fast-growing dominant species4. In our meta-analysis, 90% of the active plantations used a single dominant species (66% with legume species). The more diverse communities associated with natural regeneration could also contain a large diversity of functional traits23, which may increase soil carbon storage. For example, more diverse leaf traits (i.e. specific leaf area, chlorophyll, photosynthetic capacity) could maximize the efficiency of community light capture, and a greater diversity of root traits (i.e. specific root length, root surface area, rooting depth) tends to more effectively access soil resources24,25. Furthermore, the more diverse communities in natural regenerations may create more habitats for above- and belowground organisms, leading to more-connected biotic interaction networks4,26. These diverse and more-connected communities tend to enhance the efficiency of resource capture and use during natural ecosystem succession, further increasing the efficiency and potential of carbon sequestration (less soil respiration) in C-rich soil27. In the future, there is need for a deeper exploration of the mechanisms underlying the difference between natural regeneration and active restoration along with background SOC.

The higher plant diversity associated with natural regeneration could also account for higher gains in deep soil carbon, as has been demonstrated by studies on diversity-function relationship28. These effects may emerge, in part, because diverse communities are capable of accessing deep soil resources with deep roots29,30. The more deep root could enhance subsoil carbon input.

Use of higher diversity plantings in active restoration tends to enhance ecosystem functions, such as carbon sequestration12,31. Based on the low diversity nature of the active plantings in this study, it remains unclear whether the difference between active restoration and natural regeneration would be modified by comparisons with more diverse plantations. However, there also could be some challenges in trying to increase the diversity of planted communities, including: (i) Poor seedling establishment of tree and shrub species due to abiotic stress and intense competition from neighboring plant species32; and (ii) abiotic limitation caused by water and nutrient stress33.

Differences between active restoration and natural regeneration also depended on site age, though few studies have directly quantified the relative effect of active restoration versus natural regeneration along with site age and baseline conditions4,10. Based on our dataset, actively restored forests began sequestering more soil carbon than naturally regenerating grassland after about 17 years. Care is needed in interpreting these results, which might suggest that it is disadvantageous to plant trees in areas where climate conditions would naturally support a grassland community. Unless climate change overcomes these long-term barriers to natural tree establishment and survival in these environments, the inappropriate forms of restoration may ultimately fail because trees will eventually die when extreme drought or cold events occur34,35. This could lead to the loss of any short-term gains in soil carbon sequestration arising from the initial tree planting efforts36.

Conclusions

Our work provides new insights into the benefits of active restoration versus natural regeneration in terms of soil carbon sequestration, by using the paired design control for the confounding effects that are existed in other analyses4,10. In C-rich soil, natural regeneration sequestered more soil carbon than active restoration, but in C-poor soil, active restoration is the better choice for soil carbon sequestration benefits with human interventions. However, natural regeneration performs better in subsoil carbon storage, while active restoration is superior in topsoil carbon sequestration. When considering the potentially higher stability of subsoil than topsoil carbon storage due to low temperature and less disturbance37, natural regeneration may have an even greater benefit for soil carbon sequestration over the long term. Moreover, natural regeneration is cheaper, which could allow for more extensive restorations.

In the context of the limited resources, our work suggests that managers would be better advised to invest more resources in natural regeneration than intensive active restoration for soil carbon sequestration benefits. Overall, these suggest that adaptive management of ecosystems for carbon restoration is context-dependent application of active and natural strategies. These findings can help guide the efficient management of limited restoration resources at a landscape scale, further maximizing the benefits of soil carbon sequestration under ecosystem restoration and offsetting excess CO2 in the atmosphere.

Methods

Data collection

The ‘Grain for Green’ project was designed to restore cropland to semi-natural ecosystems (i.e. grassland, shrubland, and forest), aiming to control water and soil erosion, ameliorate soil fertility, and reverse diversity loss and ecosystem degradation14. Importantly, many restored areas simultaneously performed both active restoration and natural regeneration at the same site. This provides a valuable opportunity to conduct a large-scale paired comparison of active restoration versus natural regeneration impacts on soil carbon sequestration.

We systematically searched for the papers concerning ‘Grain for Green program’ in China and soil carbon restoration during 1900–2020, via Google Scholar, Web of Science and China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (supplementary Fig. 1). The reported studies were further screened to ensure data quality based on the following criteria. First, cropland, naturally and actively restored ecosystems must have experienced similar climate, soil conditions, history, and levels of disturbance at the same site. Second, restoration studies have been conducted with a paired comparison or chronosequence design13,14. Third, paired comparisons of active restoration versus natural regeneration have started at the same time. Fourth, data on soil depth and restoration time have been clearly provided. Fifth, data on soil carbon at the cropland, naturally or actively restored sites have been reported by their mean values and sample sizes.

Tabular data were manually copied from the identified papers, while graphical data were obtained using Engauge Digitizer (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston, MA). Finally, we screened 72 studies from 67 published papers (Fig. 1 and supplementary note 1). Our dataset (617 paired observations) covered a large spectrum of climate zones, with the mean annual precipitation and temperature spanning 263–1411 mm and −1.7 to 19.2 °C, respectively (supplementary Fig. 2, data obtained from the WorldClim dataset). The average, minimum and maximum of restoration time were 19.6, 1, and 60 years, respectively. The average, minimum, and maximum of soil depth were 30.7, 2.5, and 100 cm, respectively. Active plantations were mostly dominated by single species (92%).

Grassland was the dominant ecosystem type for sites undergoing natural regeneration (95%), with the remaining fraction being shrublands (5%). At sites with active restoration, grassland (14%), shrubland (37%), and forest (49%) were all important ecosystem types. Thus, the paired comparisons at the same site included two types of cases: naturally vs. actively restored grassland (natural grassland vs. active grassland); naturally restored grassland vs. actively restored shrubland or forest (natural grassland vs. active shrubland or natural grassland vs. active forest). The case of natural vs. active grassland provides a straightforward comparison for the control group. However, in some cases of land restoration, actively restored vegetation may be mismatched with local climate and ecosystem succession. Thus, combining the cases of natural grassland vs. active shrubland or forest enables us to know if the mismatched vegetation by active restoration could sequester more or less soil carbon than naturally regenerated vegetation. Due to the data limitation, we compared naturally restored shrubland with actively restored shrubland and forest together (natural shrubland vs. active shrubland/forest, supplementary Fig. 3).

Data analysis

Soil carbon stock is mainly determined by SOC concentration and bulk density38. Many studies in our dataset (60%) only reported the data for SOC concentration. However, for the 40% of studies that reported bulk density data, there was no difference in bulk density between sites undergoing active restoration and natural regeneration (NumDF = 1, DenDF = 135.74, p = 0.11). Furthermore, we used a design of paired comparison at the same site. Taken together, these indicated that percent changes in SOC concentration could well represent SOC stock changes when comparing active restoration and natural regeneration effects at the same site. Thus, we used the SOC concentration for the following analyses.

First, we employed log response ratio (LRR) to calculate the effects of restoration on soil carbon concentration39: LRR1 = ln(Xrestored/Xcropland), where Xrestored and Xcropland are respectively the mean values of soil carbon concentration at actively/naturally restored and cropland sites. To further compare the effects of active restoration vs. natural regeneration, we analyzed the response ratio of active restoration against natural regeneration effects, LRR2 = ln[(Xactive/Xcropland)/(Xnatural/Xcropland)], equaling to ln(Xactive/Xnatural). Xactive and Xnatural are the average SOC values in actively and naturally restored plots, respectively.

Second, to handle possible auto-correlations between various observations in each study, we included studies as random intercepts and time as random slopes using the ‘lme4’ package40. Independent studies were those performed at separate sites or in different ecosystems at each site (i.e., forest, shrubland, grassland). Third, we weighted the restoration impacts of soil carbon by the sample size for each experiment41,42, Wt LRR1 = (Nactive/natural × Ncropland)/(Nactive/natural + Ncropland) or Wt LRR2 = (Nactive × Nnatural)/(Nactive + Nnatural), where Nactive, Nnatural, and Ncropland respectively indicate the number of sampling plots (replicates) for soil carbon in actively, naturally restored ecosystems and cropland at each site. The weights ranged from 1.50 to 5.32. This weighting method was better at estimating the mean effects, through giving more weight to the studies with more replicates.

Finally, we employed the following models to calculate the weighted mean impacts (LRR) of ecosystem restoration on soil carbon with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and further explore how these impacts were modified by background SOC (bSOC), soil depth, restoration time, aridity index (AI) at both overall and ecosystem levels:

where β, πtime, πstudy and ɛ are respectively coefficients, the random intercept of study (πtime-random slope, πstudy-random intercept), and sampling residual. Fixed effects included background SOC, soil depth, restoration time and aridity index. Here, aridity index (AI) was calculated by precipitation /(temperature + 10). The average values of sampling depth ranges were calculated for analysis. Furthermore, the continuous independent variables were first natural log-transformed and then scaled {(observations-mean)/SD}, in order to directly compare the relative effects of these factors (normalized slopes).

We found that the relationships between the effects of active restoration/natural regeneration (LRR2) and background SOC/soil depth were consistent among different ecosystems. To test if these relationships were dependent on changing environment and restoration time, we further used the following model:

where the factors represent restoration time, aridity index or ecosystem type, respectively. The figures indicative of our results were made by the ‘ggplot2’ package in R 4.043.

Data availability

All data on the effects of active versus natural restoration on soil carbon sequestration in this study are available at ScienceDB (DOI: 10.57760/sciencedb.07332).

References

Lu, F. et al. Effects of national ecological restoration projects on carbon sequestration in China from 2001 to 2010. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4039–4044 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2, 122–129 (2019).

Deng, L. et al. Past and future carbon sequestration benefits of China’s grain for green program. Glob. Environ. Change 47, 13–20 (2017).

Crouzeilles, R. et al. Ecological restoration success is higher for natural regeneration than for active restoration in tropical forests. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701345 (2017).

Holl, K. D. & Aide, T. M. When and where to actively restore ecosystems? For. Ecol. Manag. 261, 1558–1563 (2011).

Chazdon, R. L. et al. The intervention continuum in restoration ecology: rethinking the active–passive dichotomy. Restor. Ecol. e13535 (2021).

Miguel, M. F., Butterfield, H. S. & Lortie, C. J. A meta-analysis contrasting active versus passive restoration practices in dryland agricultural ecosystems. Peerj 8, e10428 (2020).

Roa-Fuentes, L. L., Martinez-Garza, C., Etchevers, J. & Campo, J. Recovery of soil C and N in a tropical pasture: passive and active restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 26, 201–210 (2015).

Trujillo-Miranda, A. L., Toledo-Aceves, T., Lopez-Barrera, F. & Gerez-Fernandez, P. Active versus passive restoration: recovery of cloud forest structure, diversity and soil condition in abandoned pastures. Ecol. Eng. 117, 50–61 (2018).

Reid, J. L., Fagan, M. E. & Zahawi, R. A. Positive site selection bias in meta-analyses comparing natural regeneration to active forest restoration. Sci. Adv. 4, eaas9143 (2018).

Meli, P. et al. A global review of past land use, climate, and active vs. passive restoration effects on forest recovery. PLoS One 12, e0171368 (2017).

Ren, Y., Lü, Y., Fu, B. & Zhang, K. Biodiversity and ecosystem functional enhancement by forest restoration: a meta‐analysis in China. Land Degrad. Dev. 28, 2062–2073 (2017).

Tian, D. et al. Cropland abandonment enhances soil inorganic nitrogen retention and carbon stock in China: a meta‐analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 3898–3906 (2018).

Deng, L., Liu, G. B. & Shangguan, Z. P. Land‐use conversion and changing soil carbon stocks in C hina’s ‘Grain‐for‐Green’Program: a synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 3544–3556 (2014).

Atkinson, J. & Bonser, S. P. “Active” and “passive” ecological restoration strategies in meta-analysis. Restor. Ecol. 28, 1032–1035 (2020).

Hong, S. et al. Divergent responses of soil organic carbon to afforestation. Nat. Sustain. 3, 694–700 (2020).

Hubner, R. et al. Soil carbon sequestration by agroforestry systems in China: a meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 315, 107437 (2021).

Laganiere, J., Angers, D. A. & Pare, D. Carbon accumulation in agricultural soils after afforestation: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 439–453 (2010).

Tian, D. S. et al. Ecosystem restoration and belowground multifunctionality: a network view. Ecol. Appl. 32, e2575 (2022).

Tang, X. et al. Carbon pools in China’s terrestrial ecosystems: New estimates based on an intensive field survey. Proc. Natl Ac. Sci. USA 115, 4021–4026 (2018).

Liao C., Luo Y., Fang C., Chen J., Li B. The Effects Of Plantation Practice On Soil Properties Based On The Comparison Between Natural And Planted Forests: A Meta‐analysis (Wiley Online Library, 2012).

Friggens, N. L. et al. Tree planting in organic soils does not result in net carbon sequestration on decadal timescales. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5178–5188 (2020).

Chazdon, R. L. & Guariguata, M. R. Natural regeneration as a tool for large-scale forest restoration in the tropics: prospects and challenges. Biotropica 48, 716–730 (2016).

Bardgett, R. D., Mommer, L. & De Vries, F. T. Going underground: root traits as drivers of ecosystem processes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 692–699 (2014).

Wagg, C. et al. Functional trait dissimilarity drives both species complementarity and competitive disparity. Funct. Ecol. 31, 2320–2329 (2017).

Chazdon, R. L. et al. The potential for species conservation in tropical secondary forests. Conserv. Biol. 23, 1406–1417 (2009).

Morriën, E. et al. Soil networks become more connected and take up more carbon as nature restoration progresses. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–10 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Effects of plant diversity on soil carbon in diverse ecosystems: a global meta‐analysis. Biol. Rev. 95, 167–183 (2020).

Mueller, K. E., Tilman, D., Fornara, D. A. & Hobbie, S. E. Root depth distribution and the diversity-productivity relationship in a long-term grassland experiment. Ecology 94, 787–793 (2013).

Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Benayas, J. M. R., Newton, A. C., Diaz, A. & Bullock, J. M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: a meta-analysis. Science 325, 1121–1124 (2009).

Benayas J. R. Forests Restoration In Landscapes: Beyond Planting Trees (eds. Mansourian S., Vallauri D., and Dudley N.) (Springer, 2005).

Lopez-Barrera, F., Manson, R. H., Gonzalez-Espinosa, M. & Newton, A. C. Effects of the type of montane forest edge on oak seedling establishment along forest-edge-exterior gradients. Forest Ecol. Manag. 225, 234–244 (2006).

Choat, B. et al. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 558, 531–539 (2018).

Lloret, F., Escudero, A., Iriondo, J. M., Martínez-Vilalta, J. & Valladares, F. Extreme climatic events and vegetation: the role of stabilizing processes. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 797–805 (2012).

Yu, K. et al. Field-based tree mortality constraint reduces estimates of model-projected forest carbon sinks. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Hou, Y., Chen, Y., Chen, X., He, K. & Zhu, B. Changes in soil organic matter stability with depth in two alpine ecosystems on the Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma 351, 153–162 (2019).

Yang, Y., Mohammat, A., Feng, J., Zhou, R. & Fang, J. Storage, patterns and environmental controls of soil organic carbon in China. Biogeochemistry 84, 131–141 (2007).

Hedges, L. V., Gurevitch, J. & Curtis, P. S. The meta‐analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80, 1150–1156 (1999).

Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2014).

Ma, Z. & Chen, H. Y. Effects of species diversity on fine root productivity in diverse ecosystems: a global meta‐analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 25, 1387–1396 (2016).

Wu, Z., Dijkstra, P., Koch, G. W., Peñuelas, J. & Hungate, B. A. Responses of terrestrial ecosystems to temperature and precipitation change: A meta‐analysis of experimental manipulation. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 927–942 (2011).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics For Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the scientists who contribute the valuable data to our study. This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31988102), International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (177GJHZ2022020BS), the “Kezhen-Bingwei” Young Talents (2020RC003), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association (Grant No. 2021050).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T. and S.N. designed the study; D.T. and Y.X. conducted data analysis; D.T., T.L., and J.Y. made the figures; D.T., Y.X., and H.G. collected the data, D.T., Y.X., E.S., J.W., X.J., T.L., Z.L., J.Y., H.G., and S.N. interpreted the results, and D.T., Y.X., E.S., J.W., X.J., T.L., Z.L., J.Y., H.G., and S.N. contributed to the revision of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Kate Buckeridge, Yit Arn Teh and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Erika Buscardo, Joseph Aslin and Clare Davis. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, D., Xiang, Y., Seabloom, E. et al. Soil carbon sequestration benefits of active versus natural restoration vary with initial carbon content and soil layer. Commun Earth Environ 4, 83 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00737-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00737-1