Abstract

Earthquake ruptures along a single fault or along a connected system of faults are generally assumed to progress continuously. However, our analysis of the 2023 M7.8 Türkiye earthquake, using finite-fault joint source inversion, uncovered the occurrence of discontinuous rupture jumps. The main fault area adjacent to the splay fault where the earthquake started, and the deeper portion of the northeastern main fault segment exhibited triggered slip before the main rupture front arrived. Through seismic centroid analysis and finite-fault inversion, we estimated apparent rupture speeds within these slip patches reach approximately 6.0 km s-1, exceeding local S-wave velocity. The dynamic triggering mechanism induced the jumping rupture in these areas, resulting in an apparent rupture velocity surpassing the local shear wave velocity. These findings demonstrate the importance of dynamic triggering in adjacent fault systems during large earthquakes, influencing the extent and complexity of rupture propagation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

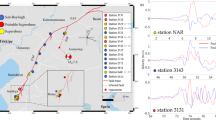

On February 6, 2023 (01:17:34 UTC), a powerful earthquake with a magnitude of Mw7.8 struck south-central Türkiye (37.226°S, 37.014°E). Just nine hours later, another event of magnitude Mw 7.6, occurred north of the initial Mw7.8 earthquake (Fig.1). Unfortunately, this subsequent earthquake resulted in tragic loss of life, with over 52,000 casualties reported in Türkiye and Syria1. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) earthquake report, the mechanism of the Mw7.8 mainshock was considered to be due to northeast to southwest strike-slip faulting. The impact of this seismic event was substantial, leading to strong ground shaking, reaching up to Mercalli intensity scale MMI XI (Extreme) southwest of the epicenter along the fault trace. Up to 2000 aftershocks with magnitudes exceeding 3.0 were recorded within a month of the mainshock2.

Red solid stars are the hypocenter of M7.8 earthquake and the epicenter of M7.5 earthquake, respectively. Red lines show the fault surface rupture trace of the M7.8 event, and the red open rectangular is the 3D fault plane. The blue circles are the M > 3.0 aftershocks from February 6 to March 31, 2023. Gray circles are the background seismicity for M > 3.0 earthquakes from January 2000 to February 2023. The purple lines are the Dead Sea Transform, and the orange lines are the surface rupture of M7.5 event. The lower right panel illustrates the study area. The map was generated by the GMT v.4.3.1 (https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/).

Türkiye is located on the collisional boundary between the Arabian Plate and the Eurasian Plate in the Eastern Mediterranean, which is one of the most active plate tectonic areas on Earth (Fig. 1). The country’s territory is almost surrounded by two large fault lines: the East Anatolian Fault (EAF), which is characterized by left-lateral fault movement, and the North Anatolian Fault, known for its right-lateral fault movement3,4. The main rupture zone of this M7.8 event was on the EAF, located at the boundary between the Arabian and Anatolian Plates in the south-central region of Türkiye. This location, lying between Kahraman Maras and Malatya, had not experienced a major earthquake in the past 500 years. The most recent large earthquakes within this region occurred in the years 1114 and 15135,6. Nalbant et al.6 proposed that this region has accumulated significant stress changes over the last two centuries due to the influence of major earthquakes in its vicinity.

One of the characteristics of this event is its long surface rupture trace, which extended up to 350 km (Fig. 1)7. The eastern extension of this surface rupture trace grew into the northeastern part of the EAF, reaching 39°E in longitude. On the western side, the surface rupture extended to the westernmost end of the EAF, where it connects with the Dead Sea Fault7,8. Additionally, the epicenter of this earthquake was located approximately 10 km away from the main trace of the EAf9. This deviation coincided with the observation of a linear trend in aftershock activity2 along this shift, indicating rupture started on a splay fault.

Various investigations have delved into unraveling the source rupture history of the Türkiye earthquake10,11,12. However, the efficacy of these published models may be limited due to various factors. Some of these models lack rupture time constraints derived from seismic waveforms7. Several inversion settings employed in these studies may not encompass sufficiently broad rupture time-space variables11,12. Therefore, the source models provided may lack the ability to elucidate the fundamental nature of this complex event, such as the debate on subshear or supershear rupture12,13,14.

In this study, we performed a joint source inversion using the teleseismic body waves, local strong motion waveforms, and local global navigation satellite system (GNSS) coseismic deformation data. The teleseismic data offer extensive azimuthal coverage of the earthquake, presenting a favorable opportunity to derive a preliminary understanding of fault rupture behavior. The GNSS coseismic deformation data constrain the overall spatial slip pattern and the final slip amount. The local strong motion waveform further offers a critical constraint, providing detailed insights into the temporal rupture process. A parallel non-negative least-square technique15 was employed in this joint source inversion with up to 45 multiple time windows, and considered a maximum rupture velocity of 6.0 km s-1 to cover sufficiently broad rupture variables. The aim was to obtain more precise source information in both space and time concerning the earthquake’s origin, especially to gain insights into the development of the long rupture associated with this earthquake. The details of the inversion method and fault model settings are provided in the Methods section. We have also included comprehensive resolution and stability tests in the supplementary text to evaluate the robustness of the inversion result.

Results

Spatial and temporal slip distribution

The joint source inversion results indicate that the spatial slip distribution of the Türkiye earthquake was complex, spanning a long 350 km ruptured zone (Fig. 2). To provide further insight, fits between observed data and synthetic data of the teleseismic waveform, local ground motion, and coseismic displacement are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 to Fig. S3. The slip mainly occurred on the EAF fault plane, and four asperities were identified. The slip originated on the splay fault with a small movement of about 0.6 m near the hypocenter. A large amount of slip occurred at the eastern boundary of the splay fault, forming a connection with the main fault to form Asperity I.

Asperity II was located close to the epicenter on the EAF fault plane, and part of its slip area was connected with Asperity I on the splay fault. This slip area has been found in other studies on the finite-fault source model10,11,12,14,16,17,18,19,20. The maximum slip exceeded 3.5 m, mainly strike-slip with rake approximately ± 10°. The deepest part of this asperity is about 30 km deep, and its shallowest part extends to the ground surface. Asperity III was located on the EAF fault plane northeast of Asperity II. This asperity was the largest in the Türkiye earthquake, extending from 37.6°E to 38.3°E and reaching a depth of approximately 40 km. Its dimensions spanned about 80 × 40 km2. The slip area extended to the shallow fault with an extremely large surface rupture of about 5.0 m. The slip was mainly strike-slip with some upward movement (rake approximately 5°) near the surface. This large slip zone has been discussed in most of the source studies10,11,12,14,16,18,19,20. Asperity IV was located in the southwestern part of the EAF fault plane. The size of this asperity was compact, about 70 × 15 km2, which concentrated between 0 km and 15 km depths with a maximum slip up to 5.0 m. The movement on this asperity was mainly strike-slip with some upward moment (rake > 10°). Several studies8,9,11,13,15,17 have also proposed similar slip patterns in this area.

In addition to the above four asperities, two smaller slip patches were observed. A slip patch (Patch A) was found between Asperity II and Asperity IV on the EAF near the hypocenter. This patch’s slip is insignificant, measuring less than approximately 2.0 m compared with other asperities. Furthermore, some small slips (Patch B) were found at the northeastern end of the EAF ruptured plane. The slip in this area was also small, less than 2.0 m. These minor slips are confined to the middle to deep crust (depths ranging from 15 km to 40 km) without extending to the ground surface.

With all these four asperities and two slip patches, the entire slip zone demonstrated a long rectangular shape that extended from southwest to northeast and exceeded 350 km. Considering a strike-slip rectangular fault with a width (\({{{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}}\)) of 30 km in a homogeneous half-space, the stress drop (\(\triangle \sigma\)) can be determined using the formula21 \(\tfrac{2}{\pi }\mu \left(\tfrac{\bar{D}}{\omega }\right)\), where \(\mu\) represents the shear modulus (3.0E + 10 N m-2), and \(\bar{D}\) is the average slip. Given that the slip area was confined to values greater than 0.1 m, the average slip (\(\bar{D}\)) measured approximately 1.2 m. Consequently, the mean stress drop observed over this extensive fault area was estimated to be 0.77 MPa.

Similar to its complex spatial slip distribution, the temporal rupture time history of the 2023 M7.8 Türkiye earthquake is also complicated (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video S1) and can be divided into four stages. In the first stage, a small slip originated on the splay fault at 0–8 s with a relatively small slip of less than 50 cm near the hypocenter. Subsequently, at approximately 10 s, slip activity started on the southwest segment of the EAF (the area marked “a” in Fig. 3). This abnormally early slip area is disconnected from the initial rupture on the splay fault. Thus, this rupture was not propagated along the splay fault, and its behavior is similar to a jumping rupture that was dynamically triggered by body waves (P or S waves). Between 14 s and 20 s, the eastern side of the splay fault kept slipping to form Asperity I.

In the second stage, the rupture started to propagate onto the junction area of the EAF and splay fault planes. After 20 s, the rupture mainly occurred on the EAF fault plane and propagated bilaterally from the junction area. It propagated near the junction in the northeastern direction between 36.9°E and 37.5°E. This area ruptured for a long period, spanning 20 s to 32 s, gradually forming Asperity II on the EAF. It is noted that, during the development of Asperity II at approximately 26 s, the deeper part (20–30 km depth) of the northeastern EAF (the area marked “d” near 38.2° E in Fig. 3) started to slip far ahead of the main rupture front. The slip in this area also behaved as a jumping rupture since it occurred before the main propagating front arrived. The slip behavior in this area continued for an extended period, from 26 s to 50 s, and eventually combined with the main subshear rupture. This merging gave rise to the largest asperity (Asperity III) observed on the EAF.

Between 50 s and 100 s, the third rupture stage mainly developed in the southwestern section of the EAF. It propagated southward and slipped for nearly 50 s between 35.7°E and 36.7°E. The rupture gradually formed slip Patch A, whose location almost overlapped the area where the earliest slip occurred (marked “a” in Fig. 3). Asperity IV was formed subsequently near the southern end of the EAF. The fourth stage developed before the rupture termination. Some slip occurred in the deep crust (between depths of 20 km and 40 km) of the easternmost part of the EAF fault plane. Over time, these small slips gradually interconnected between 100 s and 120 s, forming slip Patch B.

This complex rupture process is also presented in the moment rate function (Fig. 4), where several energy bursts can be identified. The first peak of moment release occurred between 0 s and 18 s. This is the seismic moment released from the splay fault (Asperity I) and the early triggered slip at the southwestern segment of the EAF. Asperity II and Asperity III on the EAF contributed to the second and third peaks of seismic moment between 18 s and 50 s, with some parts of the moment release overlapping. They collectively contributed a seismic moment of 4.81 × 1020 Nm, which accounts for approximately 53% of the total moment, corresponding to an Mw 7.72 earthquake. The westernmost asperity (Asperity IV) contributed to the seismic moment release at 50 s to 100 s, with several energy bursts. The seismic moment release in this period was nearly 3.60 × 1020 Nm, equivalent to magnitude Mw 7.64. Additionally, some minor moment releases were observed after 100 s, with a peak at approximately 115 s before the end of the rupture. These were caused by the easternmost rupture (slip Patch B), contributing to the seismic moment of nearly 0.33 × 1020 Nm. The overall duration of the rupture lasted approximately 120 s and resulted in a seismic moment release of 9.12 × 1020 Nm, which is equivalent to a moment magnitude of Mw 7.91.

The dark gray area shows the moment release time history. Four time periods of the seismic moment releases are marked with Stage 1 to Stage 4. The blue numbers indicate the moment releases of the four asperities. White numbers show the percentage of moment release from the total moment in each stage.

Rupture velocity on the fault plane

To evaluate the rupture speed on the fault plane, three reference rupture fronts with constant rupture velocities (Vr) of 6.0, 4.0, and 2.0 km s-1 were marked in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video S1. These reference rupture fronts propagated in the three-dimensional half-space rather than along the fault plane, which is similar to the 3D wave propagation fronts. In this case, the dynamic triggering of slip induced by the strong seismic waves can be considered and identified. As discussed in the temporal rupture process section, an abnormally early rupture was found on the southwest segment of the EAF (marked “a” in Fig. 3) at approximately 10–12 s, in which the slip occurred just after the 6.0 km s-1 reference rupture front. This implies that the rupture at this moment was faster than the local shear wave velocity (approximately 3.5–4.0 km s-122,23,24,25). The development of Asperity II had a slower rupture speed because most of the slip gradually occurred with the reference rupture front of 2.0 km s-1. Relatively, the east part of Asperity III started to slip at approximately 26 s in the deep crust just after the 6.0 km s-1 rupture front (the area marked “d” in Fig. 3). Once again, this slip exhibited characteristics of an abnormal apparent rupture speed. It is worth noting that Asperity II was still under development at this time (nearly 26 s), and its continuous subshear rupture front was slowly expanding eastward toward Asperity III. The rupture speed of Asperity IV at the westernmost side of the EAF was slow, and that rupture was between 50 s and 100 s, with a rupture speed lower than 2.0 km s-1. It is worth noting that the southwestern segment of the fault underwent repeating slips with extreme changes in rupture velocity, with apparent rupture speed close to 6.0 km s-1 at approximately 10–12 s (marked by “a” in Fig. 3) and subshear rupture between 50 s and 100 s (Patch A and Asperity IV in Fig. 3). Finally, slip Patch B in the deep part of the easternmost fault plane developed slowly with a rupture speed of approximately 2.0–3.0 km s-1 after 100 s.

We further analyzed the spatiotemporal distribution of the maximum slip rate along the fault strike to extract more rupture information (Fig. 5). Results show that the main rupture fronts on the EAF generally propagated at subshear speeds, which varied around 3.0 km s-1. Meanwhile, the occurrence times of triggered slips at areas “a” and “d” are far ahead of the main rupture front along the EAF. This implies that the triggered slips in these areas can have an abnormal apparent rupture speed caused by jumping ruptures, resulting in their apparent rupture velocity almost close to the P wave speed. Some other orange spots can be found earlier than the main rupture front (Fig. 5a). However, these spots occurred after “a” and “d”, indicating that they were subsequent ruptures following the new rupture fronts produced by triggered slips “a” and “d”. That is, triggered slips resulted in apparent supershear phenomena and produced new rupture fronts that can cause other slips to occur ahead of the main rupture front.

a Spatiotemporal distribution of maximum slip rate along strike of the fault. b The slip distribution. The maximum slip rate is derived from the maximum value of the slip rate in all depths and then projected to the strike along the fault. Black solid and open stars show the hypocenter on the splay fault and the location projected on the EAF. Blue circles indicate the areas “a” and “d” where the abnormal apparent supershear rupture occurred. Orange dotted lines show the new rupture front originating from triggered slips at “a” and “d”.

Slip Patch B occurred near the end of the rupture and was also presented as an isolated spot apart from the main rupture front. Furthermore, the southwestern segment of the EAF experienced several times of rupture, which could be due to (1) early triggered slip, (2) followed by the main rupture propagation, and (3) later stress interactions. These phenomena could correspond to a combination of some dynamic rupture scenarios under specific assumptions26. A similar rupture behavior was also found on the splay fault, in which the whole fault plane repeated slip several times during the 100 s long rupture time history. This could be the reason why the strong ground motion waveform observed at vicinity stations (2703, 2711 in Fig. S3b) has several complex wiggles compared to other near-fault stations (2712, 3143 in Fig. S3b). The stress interactions between Asperity I, II and III could play a important role in the reaction of the slip on the splay fault plane.

We made additional tests to provide compelling evidence that the source features identified in this study are robust and not artifacts, especially the triggered slips. The tests include (A) inversion with various numbers of time windows, (B) inversion with different data sets, (C) comparing the synthetic seismograms of triggered slips to the observed waveforms, and (D) realistic resolution test. The details of these results are provided in the supplementary text. The outcomes of these tests underscore the efficacy of joint source inversion in resolving both spatial and temporal slip patterns, even accounting for complex triggered slips during the rupture process. It is worth noting that in test (C), the triggered slip at area “d” significantly contributes to the teleseismic waveforms. The contribution of weak triggered slip at area “a” can also be observed in most stations, but it is not that apparent. This could be due to the small seismic energy released from the area “a” (7.89 × 1018 Nm ~ Mw6.53), only about 0.86% of the total moment (9.12 × 1020 Nm ~ Mw7.91). In other words, the large local strong ground motion dominates the main rupture characteristics on the fault plane and overshadows the contributions from relatively weak triggered slips in most of the local waveforms.

Our results are consistent with several recent investigations that have identified supershear propagation during the rupture of this event. Rosakis et al.27 provided evidence for an instantaneous supershear speed of nearly 1.55 times the Vs close to the epicenter. Delouis et al.14 identified several portions of the EAF where the rupture accelerated to supershear with a speed of approximately 4.0 km s-1. The first occurred in the southern section of EAF, about 80 km from the junction. This is like our apparent supershear founding in area “a”. The second one was located at the northern segment of EAF, about 100 km away from the junction, and this area is close to our result in area “d”.

However, our result had a different interpretation of the high rupture speed phenomenon. Delouis et al.14 indicated it as supershear, while we attribute it to apparent supershear caused by a jumping rupture. These differing explanations may arise from different foundational assumptions in the inversion. Delouis et al.14 constrained that the rupture propagated continuously, which needed to occur after it propagated to the EAF through the junction. Then, the rupture speed gradually transitions to supershear on the EAF. Our study used the Vrmax (6.0 km s-1) to estimate the earliest rupture front propagated in the three-dimensional half-space rather than along the fault plane. By doing so, the inversion can determine whether the rupture is subshear, supershear, or even a jumping rupture. According to our joint inversion result, we proposed that the high rupture speed found in areas “a” and “d” was an apparent supershear phenomenon caused by triggered slips ahead of the main rupture front. This resulted in the apparent rupture velocity being higher than the shear wave speed in the surrounding rock.

The high rupture speed phenomenon was also observed from a dynamic rupture model proposed by Wang et al.13. In their model, supershear rupture was observed in the northeastern region of the EAF, and the rupture speed along the southwestern segment of the EAF exhibited variations between supershear and subshear. It is noted that these models are based on the assumption of continuous rupture systems and may not account for discontinuous jumps, potentially leading to a misinterpretation of rupture jumps as continuous supershear ruptures.

The abnormally high apparent rupture speed of over 4.0 km s-1 occurred during the early development of slip Patch A, and the deep slip of Asperity III might be attributed to two potential factors. The first is that a new rupture (the initiation of slip Patch A, i.e. area “a” marked in Fig. 3) was dynamically triggered by a strong seismic wave propagating at P wave speed; this led to an increased apparent rupture velocity found at the initial stage (10 s) of the earthquake on the EAF. Secondly, the average Vs is approximately 4.0 km s-1 within the deeper crust (~ 30 km), which could further contribute to a heightened rupture velocity. However, when Asperity III initially formed at the deep crust (area “d” in Fig. 3), its apparent rupture velocity exceeded 4.0 km s-1, implying that dynamic triggering provides a more plausible explanation in this area. Dynamic stress triggering is a common phenomenon in which the propagating seismic waves caused by large earthquakes trigger other distant events28,29,30,31,32. However, the phenomenon of dynamic triggering, causing distant areas on the same fault system to slip before the main rupture front during the rupture process of a major earthquake, is rarely observed and challenging to identify33,34. The 2023 Türkiye earthquake may be one of those rare cases.

Centroid location versus maximum rupture speed

To verify the reliability of the abnormally high rupture speed discovered by finite-fault source inversion, a centroid moment tensor (CMT) analysis was performed through a comprehensive grid search to find the best-fit centroid position. A dense virtual point was set for the grid search of the CMT inversion (Supplementary Fig. S4). Here, the CMT analysis based on the observed teleseismic data was investigated first (Fig. S5). Then the result was compared with that of CMT inversion results derived from the synthetic waveforms according to finite-fault source inversion models with maximum rupture velocities (Vrmax) of 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 km s-1. Results show that the slip was closer to the hypocenter if the Vrmax was smaller. The larger Vrmax resulted in a wider spread of slip patterns. The slip distribution became stable when Vrmax is greater than or equal to 6.0 km s-1. Their related CMT analysis results are provided in Supplementary Figs. S6 to S11. The finite-fault inversion results with varied Vrmax are provided in Supplementary Fig. S12.

The CMT of the Türkiye earthquake shows that the focal mechanism is generally a strike-slip fault (Fig. 6), which is consistent with most of the CMT reports (Table 1). However, it contains a large part of the compensated linear vector dipole (CLVD) component, approximately 22% of the total moment. This result may be attributed to the intricate slip distribution, the curved fault geometry, and the unusually extended rupture length, all of which deviate from the assumption of a point source. The centroid is located approximately 72 km east of the epicenter and is somewhat offset from the EAF, which is approximately 20 km to the south. The moment tensor solutions determined from the finite-fault synthetic waveforms presented a similar strike-slip focal mechanism with part of CLVD component (Table 1). These CMT centroid locations show a remarkable linear trend, i.e., the larger the maximum rupture velocity set in the finite-fault inversion, the more the centroid locations were moved to the northeast (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The centroid positions determined using Vrmax values of 6.0 km s-1 and 7.0 km s-1 closely align with the position determined from the observed data. This result implies that the maximum rupture speed in the Türkiye earthquake could reach up to 6.0 km s-1, which further validates our finding of abnormally high-speed apparent supershear rupture in the finite-fault source inversion.

The red star is the M7.8 event epicenter, and the black star shows the M7.5 event epicenter. The red focal mechanisms are CMT reports by the USGS, GCMT, GFZ, and AFAD. The focal mechanisms colored by light to deep blue are the CMT inversion results based on the finite-fault source models with maximum rupture velocities of 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 km s-1, respectively. The blue focal mechanism is the CMT determined by the teleseismic observed waveforms. Circles indicate their related centroid locations. All of these centroid parameters are provided in Table 1. The map was generated by the GMT v.4.3.1 (https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/).

The finite-fault inversion result shows a moment magnitude of Mw 7.91, this is more than Mw 7.8, as the USGS and IRIS reported. It is crucial to note that the moment magnitude taken from the general earthquake report is usually derived from the CMT analysis, which considers the earthquake as a point source. However, if the rupture length of an earthquake is long, the point source assumption may not be appropriate, thus causing a bias in the seismic magnitude. This is also consistent with the previous centroid location analysis. The moment magnitude determined from the CMT inversions based on synthetic or observed data is approximately Mw7.73 to Mw7.82 (Table 1). The other potential cause of the difference in magnitude is the used frequency band. For the finite-fault source inversion, the teleseismic waveforms are bandpassed between 2 s and 100 s. The CMT inversion usually uses a lower frequency band; in our case, the waveforms are bandpassed between 100 s and 200 s. This implies that the CMT inversion might lose the high-frequency seismic energy released from small slip patches, thus underestimating the earthquake magnitude and the total seismic moment.

Discussion

Typically, fault ruptures propagate continuously. It occurs when the initial rupture on a fault transfers stress to the adjacent section of the fault, causing it to rupture. This process leads to a cascading effect where the rupture front propagates along the fault plane, triggering subsequent ruptures. However, the early slip on slip Patch A (area “a” in Fig. 3) and the deep origin of Asperity III (area “d” in Fig. 3) occurred before the main rupture front arrived. In other words, the rupture discontinuous jumps from one fault to another and secondary rupture ahead of the main rupture front, which requires a dynamic triggering mechanism.

Discontinuous jumping rupture could occur during an earthquake for various reasons. When jumping occurs, specific segments of the fault experience slip and rupture independently rather than propagating continuously. Factors such as fault heterogeneity, stress conditions, or fault interactions can affect these isolated slip segments. The dynamic triggering of strong seismic waves may be a key factor linking these characteristics to cause discontinuous jumps. Rupture can thus jump to another part on the fault plane or adjacent faults if the stress in those areas has approached the critical condition. As a result, the apparent rupture speed observed in the case of jumping slip can surpass the shear wave velocity of the surrounding rock to become an apparent supershear rupture. This interaction highlights the complex behavior of earthquakes, where the interplay between triggered slip and approaching continuous rupture front can lead to localized slip jumps and apparent rupture speeds that exceed expectations35. This may explain the early rupture of slip Patch A and the deep origin of Asperity III, in contrast to the main continuous subshear, bilateral propagated rupture fronts along the EAF.

Very few documented instances of a complex cascading rupture occurred during past earthquakes. The 1992 Landers earthquake in California entailed the rupture of numerous fault segments, including the main Landers Fault and several secondary faults36. The 2002 Denali Fault earthquake in Alaska also involved a complex rupture pattern where the earthquake ruptured several segments in a cascading manner along a multiple-fault system37. The rupture extended over a distance of approximately 340 km. The 2016 Kaikōura earthquake (M7.8) in the South Island of New Zealand was also a complex big event that ruptured at least 12 fault segments38. Its complex triggering between fault segments resulted in a cascading rupture with a slow averaged rupture speed39. In contrast, ruptures with simultaneous discontinuous jumping slip before the main rupture front and accompanying apparent supershear phenomena in a single event have rarely been identified, and the 2023 Türkiye earthquake may be the first and only example. It is noted that extreme variation of the rupture speed between subshear and apparent supershear could lead to abnormally strong ground shaking, such as repeated and enhanced rupture directivity effects. This can be the cause of extremely strong ground shaking observed in the area along the southwestern segment of the fault. A similar ground motion-enhanced phenomenon has also been discussed in a dynamic rupture process analysis proposed by Wang et al.13.

In summary, in the case of a discontinuous jumping rupture process, the strong seismic waves originating from the initial rupture can trigger a dynamic subevent ahead of the main rupture front. In this phenomenon, slip occurs on adjacent fault segments when the interface is weak or approaching critical stress conditions. Consequently, this can result in an apparent rupture speed faster than the shear wave velocity. This interaction between jumping slip and apparent supershear rupture contributes to earthquakes’ complex dynamics and behavior. Further in-depth source dynamic research into this event’s discontinuous jumps and abnormal apparent supershear rupture is essential35. It has the potential to advance our understanding of earthquake source physics substantially.

Methods

Data processing

Three data sets were employed in the joint source inversion analysis: teleseismic waveforms (body waves), local strong motion data, and GNSS coseismic displacements. The teleseismic data were acquired from the Global Seismic Network (GSN), and 72 records in vertical, east-west, and north-south directions were selected. To mitigate the complexities of the shallow Earth’s crust, the utilized stations were restricted to an epicentral distance ranging from 30° to 90°.

The teleseismic velocity seismogram, covering a period of 6000 s and starting 2400 s before the event, was subjected to a one-pass Butterworth bandpass filter with four poles. The cutoff frequencies for this filter were set at 0.01 Hz and 0.5 Hz. Subsequently, the data were integrated to calculate displacements and resampled at a rate of 5 points per second. A time window of 130 s, which included the 10 s leading up to the P wave arrival, was extracted from the filtered waveform for analysis.

The coseismic displacement data were compiled from 131 continuous GNSS stations. The raw data was obtained from the Turkish Continuously Operating Reference Station (CORS) network, which recorded coseismic displacements between the Anatolian and Arabian Plates. The data were processed and released by the Nevada Geodetic Laboratory40. The coseismic displacements was estimated from 5 min sample rate time series data derived from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory rapid orbit satellites. Data was divided into periods before, between, and after the M7.8 earthquakes to calculate displacements.

Local strong motion data can be accessed through the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority–Turkish Earthquake Data Center System, AFAD, available at https://tdvms.afad.gov.tr/. The joint inversion utilized 96 local waveforms encompassing all three components (east-west, north-south, and vertical), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The raw data underwent band-pass filtering within the frequency range of 0.03 Hz to 0.5 Hz, followed by twice integration to derive displacements. A 100 s waveform, starting at the origin time of the event, was used in the inversion, with a sampling interval of 0.2 s.

3D fault model

Based on the surface rupture data provided by the USGS9 and the seismic source location reported by both the USGS and the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS41), we assumed a 3D ruptured fault plane that runs from the northeast to the southwest along the EAF, with a noticeable bend from NE-SW orientation to the ENE-WSW direction near the earthquake epicenter (Fig. 1). There is a offset of approximately 10 km between the epicenter and the main fault surface, as determined by IRIS, USGS, the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ), and AFAD. Therefore, this study established a secondary segment, which extends from a slight splay of the main rupture line from north of the epicenter, to connect the EAF. The fault surface was divided into 600 subfaults that extend to depth along the existing fault line. These subfaults exhibit a range of strike angles varying from 10° to 70°. Referring to the geometry of the preliminary finite fault solution from USGS, west-dipping angles of the fault planes range between 85° to 87°, constraining with the focal mechanism, aftershock distribution, background seismicity, and geometric configuration. The depth range extends from 0 km to 55 km. Each subfault has an approximate dimension of 6.7 km in length and 6.7 km in width, resulting in an area of approximately 45 km2 for each subfault.

Finite-fault source inversion

The equation representing joint source inversion, which characterizes the earthquake’s rupture history, is given as Ax = b. The vector b encompasses two sets of observational data, matrix A accommodates the corresponding Green’s functions, and the solution vector x governs the determination of slip distribution. To assess the fidelity of the fit between the synthetic and observational data, a misfit function defined as (Ax − b)2/b2 was employed. A small value of the misfit function indicates a good fit to the data. A misfit value of 0 means the synthetic and observational data fit perfectly.

We employed multiple time windows in the inversion, following the methodology that Hartzell and Heaton42 proposed. To provide long enough rupture duration on each subfault in the inversion, there were 45 multiple time windows, each spanning 4 s, with a 2 s overlap. The inversion’s maximum rupture velocity (Vrmax) is set to 6.0 km s-1; that is, the rupture speed can vary between 0.0 and 6.0 km s-1. The Vrmax in this study was used to estimate the earliest rupture front propagated in the three-dimensional half-space rather than along the fault plane, which is similar to the 3D wave propagation fronts. By utilizing numerous time windows and a high maximum rupture velocity, the inversion effectively encompasses a wide range of rupture variables. Under such inversion conditions can dynamically trigger slip on the fault plane caused by strong seismic waves be considered. This inversion problem was solved using the parallelized non-negative least squares technique introduced by Lee et al.15 on a high-performance computing cluster comprising 24 nodes.

The matrix A in the joint source inversion incorporated Green’s functions of the teleseismic network, local strong motion network, and the local GNSS station. The Green’s functions for the teleseismic network were derived using the Synthetics Engine (Syngine) with the Preliminary Reference Earth Model (PREM), a one-dimensional Earth reference model provided by the IRIS Data Management Center (IRIS DMC43). The synthetic teleseismic waveforms utilized the identical filtered frequency band as the observation. The Green’s functions for the local strong motion data were calculated by using AxiSEM44 with a 1D reference velocity model provided by IRIS DMC43. Given the substantial magnitude of this earthquake, the prevailing feature in the local ground motion displacement waveforms is the dominance of low-frequency source effects, with a primary frequency over 10 s. This characteristic decreases the potential impact of detailed three-dimensional subsurface structures required for calculating synthetic waveforms for the local stations. We employed Okada’s45 analytical expressions to calculate horizontal static displacement in geodetic Green’s functions. These expressions account for surface deformation resulting from uniform slip over individual subfaults.

Centroid moment tensor inversion

The centroid moment tensor (CMT) inversion formulation also adopts a linear framework, expressed as Ax = b. In this context, matrix A represents Green’s functions between each source-station pair, vector b represents the observed waveform data, and vector x represents the solution of the 6-moment tensor elements46. The system of linear equations for the moment tensor elements was solved using the singular value decomposition technique. To assess the misfit between observed data and synthetics, a least-square misfit function was employed:

where \({O}_{i}\left(t\right)\) and \({S}_{i}\left(t\right)\) represent the observed and synthetic seismograms. This formula exhibits higher sensitivity to waveform correlation rather than absolute amplitudes, as noted by Wallace et al.47. Consequently, the need for a priori structural information is less crucial.

To explore the optimal fit solution among all virtual grid points, a misfit reduction (MR) measure was employed.

A CMT solution exhibiting a perfect fit would yield an MR value of 10048,49.

The teleseismic broadband data utilized in the CMT inversion process were also taken from the IRIS DMC. In this analysis, a total of 108 GSN stations were included, each providing three data components. The time window employed for the inversion spanned 720 s. The selected time window of 720 s proved adequate for encompassing essential seismic phases, such as the initial P arrival, S wave, W-phase, surface wave, and subsequent phases when the seismic stations are located within an epicentral distance of approximately 5000 km. To mitigate the effects of localized propagation path variations and the complexities introduced by three-dimensional Earth structures, the seismograms were subjected to bandpass filtering, specifically targeting frequencies within the 0.005–0.01 Hz range. This frequency band effectively discounts localized path details and 3D Earth structure effects, particularly pertinent for long-period signals.

A grid with random points was established within the source region to determine the optimal fitting CMT solution and precise centroid location (Supplementary Fig. S4), featuring an average grid spacing of approximately 5 km. This virtual grid encompassed a total of 94,563 points. Each grid point and seismic station pairing corresponds to six Green’s functions, representing the six moment tensor elements. The matrix A incorporates these Green’s functions, which were computed using the IRIS Synthetics Engine. The source database of Green’s functions was the same as the teleseismic Green’s functions used in finite-fault source inversion, but the applied bandpass frequency band was different, ranging from 0.005 Hz to 0.01 Hz. Subsequently, moment tensor inversion was employed, and the MR was evaluated across all grid points to explore the best fit CMT solution.

Data availability

The teleseismic data can be download from IRIS data management center. (https://ds.iris.edu/ds/nodes/dmc/). The strong motion data is available on the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority–Turkish Earthquake Data Center System, AFAD. The coseismic displacement data was processed by the Nevada Geodetic Laboratory and has been released on their website (http://geodesy.unr.edu/).

Code availability

Code to calculate the teleseismic Green’s functions is available at reference43.

References

Dal Zilio, L. & Ampuero, J. P. Earthquake doublet in Turkey and Syria. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–4 (2023).

AFAD. Disaster and emergency management authority–Turkish earthquake data center system. https://deprem.afad.gov.tr (2023).

McKenzie, D. The East Anatolian Fault: A major structure in Eastern Turkey. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 29, 189–193 (1976).

Jackson, J. & McKenzie, D. Active tectonics of the Alpine—Himalayan Belt between western Turkey and Pakistan. Geophys. J. Int. 77, 185–264 (1984).

Ambraseys, N. N. & Jackson, J. A. Faulting associated with historical and recent earthquakes in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Geophys. J. Int. 133, 390–406 (1998).

Nalbant, S. S., McCloskey, J., Steacy, S. & Barka, A. A. Stress accumulation and increased seismic risk in eastern Turkey. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 195, 291–298 (2002).

Reitman, N. G. et al. Rapid surface rupture mapping from satellite data: The 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Turkey (Türkiye), earthquake sequence. The Seismic Record 3-4, 289–298 (2023).

Emre, Ö. et al. Active fault database of Turkey. Bulletin Earthquake Eng.16-8, 3229–3275 (2018).

U.S. Geological Survey. Event page for M 7.8 - Pazarcik earthquake, Kahramanmaras earthquake sequence; https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000jllz/finite-fault (2023).

Zhao, J. J., Chen, Q., Yang, Y. H. & Xu, Q. Coseismic Faulting Model and Post-Seismic Surface Motion of the 2023 Turkey–Syria Earthquake Doublet Revealed by InSAR and GPS Measurements. Remote Sensing 15, 3327 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. The overall-subshear and multi-segment rupture of the 2023 Mw7. 8 Kahramanmaraş, Turkey earthquake in millennia supercycle. Commun. Earth Environ. 4-1, 379 (2023).

Melgar, D. et al. Sub- and super-shear ruptures during the 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6 earthquake doublet in SE Türkiye. Seismica, 2-3; https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v2i3.387 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Dynamic rupture process of the 2023 MW 7.8 Kahramanmaraş earthquake (SE Türkiye): Variable rupture speed and implications for seismic hazard. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50-15, e2023GL104787 (2023).

Delouis, B., van den Ende, M. & Ampuero, J. P. Kinematic Rupture Model of the 6 February 2023 M w 7.8 Türkiye Earthquake from a Large Set of Near‐Source Strong‐Motion Records Combined with GNSS Offsets Reveals Intermittent Supershear Rupture. Bulletin Seismological Society of Am. 114-2, 726–740 (2024).

Lee, S. J. et al. Source complexity of the 4 March 2010 Jiashian, Taiwan Earthquake determined by joint inversion of teleseismic and near field data. J. Asian Earth Sci. 64, 14–26 (2013).

Jia, Z. et al. The complex dynamics of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş, Turkey, M w 7.8-7.7 earthquake doublet. Science 381-6661, 985–990 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Geometric controls on cascading rupture of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquake doublet. Nat. Geosci. 16-11, 1054–1060 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Complex multi-fault rupture and triggering during the 2023 earthquake doublet in southeastern Türkiye. Nature. Communications 14-1, 5564 (2023).

He, L. et al. Coseismic kinematics of the 2023 Kahramanmaras, Turkey earthquake sequence from InSAR and optical data. Geophysical Res. Lett. 50-17, e2023GL104693 (2023).

Sylvain, B. et al. Slip distribution of the February 6, 2023 Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.6, Kahramanmaraş, Turkey earthquake sequence in the east Anatolian Fault Zone. Seismica 3-2, https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v2i3.502 (2023).

Kanamori, H. & Anderson, D. L. Theoretical basis of some empirical relations in seismology. Bulletin Seismological Society Am. 65-5, 1073–1095 (1975).

Warren, L. M. et al. Crustal velocity structure of Central and Eastern Turkey from ambient noise tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 194, 1941–1954 (2013).

Delph, J. R., Biryol, C. B., Beck, S. L., Zandt, G. & Ward, K. M. Shear wave velocity structure of the Anatolian Plate: anomalously slow crust in southwestern Turkey. Geophys. J. Int. 202, 261–276 (2015).

Kaviani, A. et al. Crustal and uppermost mantle shear wave velocity structure beneath the Middle East from surface wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 221, 1349–1365 (2020).

Medved, I., Polat, G. & Koulakov, I. Crustal Structure of the Eastern Anatolia Region (Turkey) Based on Seismic Tomography. Geosci. J. 11, 91 (2021).

Ding, X. et al. The sharp turn: Backward rupture branching during the 2023 Mw 7.8 Kahramanmaraş (Türkiye) earthquake. Seismica, 2-3, https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v2i3.1083 (2023).

Rosakis, A., Abdelmeguid, M. & Elbanna, A. Evidence of Early Supershear Transition in the Feb 6th 2023 Mw 7.8 Kahramanmaras, Turkey Earthquake From Near-Field Records. EarthArXiv preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.07214 (2023).

Gomberg, J., Bodin, P., Larson, K. & Dragert, H. Earthquake nucleation by transient deformations caused by the M = 7.9 Denali, Alaska, earthquake. Nature 427, 621–624 (2004).

Freed, A. M. Earthquake triggering by static, dynamic, and postseismic stress transfer. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 335–367 (2005).

Velasco, A. A., Hernandez, S., Parsons, T. & Pankow, K. Global ubiquity of dynamic earthquake triggering. Nat. Geosci. 1, 375–379 (2008).

Prejean, S., & Hill, D. Dynamic triggering of earthquakes. Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science (Ed. R. A. Meyers) 2600-2621 (Springer, 2009).

Pollitz, F. F., Stein, R. S., Sevilgen, V. & Bürgmann, R. The 11 April 2012 east Indian Ocean earthquake triggered large aftershocks worldwide. Nature 490, 250–253 (2012).

Lee, S. J. et al. Evidence of large scale repeating slip during the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L19306 (2011).

Vallée, M. et al. Self-reactivated rupture during the 2019 Mw=8 northern Peru intraslab earthquake. Earth Planetary Sci. Letters 601, 117886 (2023).

Kame, N. & Uchida, K. Seismic radiation from dynamic coalescence, and the reconstruction of dynamic source parameters on a planar fault. Geophys.J. Int. 174-2, 696–706 (2008).

Cohee, B. P. & Beroza, G. C. Slip distribution of the 1992 Landers earthquake and its implications for earthquake source mechanics. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 84, 692–712 (1994).

Eberhart-Phillips, D. et al. The 2002 Denali fault earthquake, Alaska: a large magnitude, slip-partitioned event. Science 300, 1113–1118 (2003).

Hamling, I. J. et al. Complex multifault rupture during the 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikōura earthquake, New Zealand. Science 356, eaam7194 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. The 2016 Kaikōura earthquake: Simultaneous rupture of the subduction interface and overlying faults. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 44–51 (2018).

Blewitt, G., Hammond, W. C., & Kreemer, C. Harnessing the GPS data explosion for interdisciplinary science. Eos, 99 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2018).

Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology. Moment Tensor for MW 7.8 (GCMT) TURKEY. http://ds.iris.edu/spud/momenttensor/21237897 (2023).

Hartzell, S. H. & Heaton, T. H. Inversion of strong ground motion and teleseismic waveform data for the fault rupture history of the 1979 Imperial Valley, California, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 73, 1553–1583 (1983).

IRIS DMC. Data Services Products: Synthetics Engine https://doi.org/10.17611/DP/SYNGINE.1 (2015).

Nissen-Meyer, T. et al. AxiSEM: broadband 3-D seismic wavefields in axisymmetric media. Solid Earth 5–1, 425–445 (2014).

Okada, Y. Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 75, 1135–1154 (1985).

Aki, K. & Richards, P. G. Quantitative seismology 2nd ed. Herndon, VA: University Science Books 37–59 (2002).

Wallace, T. C., Helmberger, D. V. & Mellman, G. R. A technique for the inversion of regional data in source parameter studies. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 86, 1679–1685 (1981).

Kawakatsu, H. On the Realtime Monitoring of the Long-period Seismic. Bull. Earthq. Res. Inst. Univ. Tokyo 73, 267–274 (1998).

Lee, S. J. et al. Towards real-time regional earthquake simulation I: real-time moment tensor monitoring (RMT) for regional events in Taiwan. Geophys. J. Int. 196, 432–446 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This research was funded through the Ministry of Science and Technology with Grant Number NSTC 111-2123-M-001-010-. The TEC contribution number for this article is 00190.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J. spearheads the research and writing efforts, encompassing conceptualization, methodology, software, analysis, and composition. T.Y. and T.C. provided support in data processing, formal analysis, writing, and editing. The manuscript was collectively reviewed by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Stefan Nielsen, Yijun Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SJ., Liu, TY. & Lin, TC. Abnormal apparent supershear rupture with discontinuous jumping propagation during the 2023 Türkiye M7.8 earthquake. Commun Earth Environ 5, 331 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01481-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01481-w

This article is cited by

-

The characteristics of seismicity in East Anatolian Fault Zone

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)