Abstract

To reduce uncertainties in future sea level projections, it is necessary to closely monitor the evolution of the Antarctic ice-sheet. Here, we show that seawater oxygen isotopes are an effective tool to monitor ice-sheet freshwater discharge and its contributions to sea level rise. Using the isotope-enabled Community Earth System Model with imposed estimates of future meltwater fluxes, we find that the anthropogenic ice-sheet signal in water isotopes emerges above natural variability decades earlier than salinity-based estimates. The superiority of seawater isotopes over salinity in detecting the ice-sheet melting can be attributed to the higher signal-to-noise ratio of the former and the fact that future sea ice changes only contribute little to seawater isotopes but a lot to salinity. We conclude that in particular in the Ross Sea sector, continuous seawater oxygen isotope measurements could serve as an early warning system for rapid anthropogenic Antarctic ice-sheet mass loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antarctica constitutes Earth’s largest freshwater reservoir. Future melting of Antarctic glaciers1,2,3,4,5,6 and the ice-sheet7,8 will contribute to global sea-level rise9,10. Antarctic ice-sheet freshwater discharge (IFD) into the Southern Ocean11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 has also been shown to reduce bottom-water formation20 and increase sea ice cover11,12. These changes in turn generate subsurface warming21 and surface cooling, which leads to an intensification of the atmospheric westerlies22 with subsequent effects on nutrients and marine productivity19.

Recent studies have shown that coupled climate-ice-sheet processes can potentially delay anthropogenic warming in the Southern Hemisphere23. Representing these coupled feedbacks in the next generation of earth system models will be crucial for obtaining realistic climate, sea level, and carbon cycle projections. To test and benchmark coupled ice-sheet climate models, it is necessary to obtain trustworthy observational datasets of Antarctic IFD fluxes and corresponding ice volume changes. To this end, various large-scale remote sensing-based observational campaigns (Satellite & air-borne) have been launched which in turn generated key datasets24,25. These have been complemented by more robust and direct observations of local IFD signals (e.g. δ18O of seawater, noble gases, CTD, etc.)26,27,28,29. However, the observational approaches have limitations in terms of spatial and temporal coverage, and there is currently no large-scale in-situ ocean monitoring system that could provide direct quantitative evidence for IFD changes. Moreover, it remains unclear, what the best strategy would be to identify IFD signals and differentiate those from other sources of freshwater (i.e., sea ice melting and precipitation). Here we propose that seawater isotope measurements provide important quantitative information on the Antarctic IFD.

The meridional transport of water vapor in the atmosphere and the associated Rayleigh distillation generate isotopically depleted precipitation over Antarctica relative to lower latitude, preferentially fixing lighter isotopes (16O) into the Antarctic ice-sheet30,31,32,33,34 and generating negative δ18Oice. With anthropogenic warming, Antarctic ice, which is isotopically depleted relative to seawater, can melt, either at the surface, or through sub-shelf melting or melting of icebergs in the Southern Ocean, which in turn reduces the oxygen isotope fraction in δ18O of seawater (δ18Osw). Therefore, tracking δ18Osw may provide insights into the anthropogenic IFD history11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Other sources of depleted δ18O (relative to seawater) that need to be considered in calculating mass budgets include changes in precipitation and brine water rejected during sea ice formation. Fortunately, the freezing/melting of seawater only leaves a small impact on δ18Osw35,36,37, which greatly simplifies freshwater budget calculations. This is in stark contrast to salinity, which is affected by IFD, precipitation, and sea ice changes. Here we apply projections of IFD forcing obtained from a coupled climate-ice-sheet model simulation9 to the isotope-enabled Community Earth System Model (iCESM) version 1.2.2 (see Methods) with the aim to identify the time horizons of emergence and detectability of the anthropogenic IFD signal, relative to the naturally occurring variability. We will focus in this study on the added benefits that can be obtained from monitoring δ18Osw as a proxy for IFD vis-à-vis salinity.

Results

Natural variability of salinity and δ18Osw due to ambient freshwater

The regional detectability of the forced IFD, either in terms of sea surface salinity (SSS) or δ18Osw, depends i) on how quickly the IFD signal is diluted in the Southern Ocean by other factors, ii) on the internal variability of intraseasonal to interannual timescales (Fig. 1a–d), and iii) on the amplitude of the anthropogenic IFD signal (Fig. 1e, f). To better understand why δ18Osw is superior in detecting anthropogenic IFD, compared to SSS measurements, we first focus on the four major sources of freshwater input to the Southern Ocean under present-day conditions, which influence the natural variability and modify the IFD signals in SSS and δ18Osw. The present-day unperturbed iCESM control experiment (CTR, see Methods) captures different oceanic freshwater sources, such as meteoric water (precipitation minus evaporation, hereafter referred to as PME) (Fig. 2a, e), liquid run-off (Fig. 2b, f), and sea ice freezing and melting (Fig. 2c, g). It is important to note that our unperturbed control experiments do not include IFD but represent only liquid run-off from the land (Fig. 2b, f), because iCESM lacks an interactive ice-sheet model, as described in the Methods section. Brine rejection decreases the salinity of sea ice relative to the surrounding seawater. The freezing process leads to the fractionation of water isotopes, with heavier isotopes accumulating in sea ice and lighter isotopes being released into seawater38. This results in a sea ice δ18O value of +1.4‰ as modeled in iCESM. When sea ice melts, ocean salinity decreases but δ18Osw increases. This is opposite to all other freshwater sources (e.g., IFD, liquid run-off, precipitation), which are associated with a decrease in salinity, a negative δ18Osw anomaly, and in general, much larger amplitude perturbations (−32‰, −20‰ to −14‰. respectively).

| The upper panel represents intraseasonal variability (1σ) of a SSS and b δ18Osw calculated from the monthly means spanning 2001–2100 in the control experiment. The middle panel shows interannual variability (1σ) of c SSS and d δ18Osw, derived from annual means over the same period. The bottom panel illustrates the forced responses in the annual mean of e SSS and f δ18Osw during a period of robust ice-sheet freshwater discharge forcing input (2076–2085) from FWF-SSP585-forced experiments.

| Contributions of the major sources of freshwater inputs to mixed layer δ18Osw and salinity were calculated from the unperturbed 2001–2100 control experiment (see Methods). These freshwater sources to the upper ocean δ18Osw include a Precipitation-evaporation (PME), b Liquid run-off (LROFF), and c. Sea ice (SICE). d The contribution of each freshwater source to the mixed layer δ18Osw is spatially averaged over 90°S-60°S and presented as a percentage contribution to the total freshwater effect on δ18Osw. Similarly, the contributions of these freshwater inputs to upper ocean salinity are described in e–h, in the same manner as a–d.

Using the present-day iCESM control experiment, we calculated the respective climatological contributions of these processes to the composition of mixed layer δ18Osw and salinity (see Methods). In the context of the hydrological cycle31, the typical precipitation δ18O value over the Southern Ocean attains values of −14‰ on average and −18‰ near the Antarctic coast33. The influence of PME on the patterns of mixed layer δ18Osw and salinity is qualitatively similar (Fig. 2a, e). The spatially averaged (90°S −60°S) PME contribution to mixed layer δ18Osw is comparable to that of liquid run-off (Fig. 2d), even though the latter is concentrated more near the Antarctic coast (Fig. 2b). Regarding SSS, the averaged PME contribution is similar to that of sea ice (Fig. 2h). However, the regional patterns of these factors are markedly different, with PME showing a much more spatially homogenous effect, spread out across the Southern Ocean, whereas the other factors obtain much higher values close to the Antarctic continent. Furthermore, when compared to other freshwater sources, IFD generates a much larger signature in δ18Osw due to the lower isotopic source value of −32‰ (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2) (e.g., PME δ18O within −14‰), whereas the salinity response to the different forcings is virtually the same (or similar in the case of sea ice within 6 psu38,39) – at least normalized by accumulated freshwater flux. Therefore, the impact of PME in diluting the onshore IFD signal in mixed layer δ18Osw is expected to be relatively small compared to that of mixed layer salinity. Future climate change will increase precipitation around the Southern Ocean. This could potentially dilute the IFD signal in δ18Osw. However, we expect this effect to be small near the Antarctic coast compared to the future IFD flux of δ18O which may further improve the detectability of future IFD, in terms of δ18Osw changes.

Here we introduce the term liquid run-off (because iCESM does not include solid iceberg calving). Liquid run-off is now defined as the sum of snow-liquid run-off from snow cap melting (dominant part) and the precipitation-liquid run-off part, which for Antarctica amounts to only about 10% of the total liquid portion. In our iCESM control experiment, we assume liquid run-off (which is dominated by snow cap melting) near the coast of Antarctica (Fig. 2b) to have an average δ18O of −20‰ (minimum −24‰). This suggests that this contribution may become more significant if we transitioned to an interactive ice-sheet model, which includes IFD in the hydrological budget. However, already in the control experiment, we find a significant contribution of liquid run-off to the mixed layer δ18Osw of 33% (Fig. 2b, d), as compared to only a 21% contribution to mixed layer salinity (Fig. 2f, h).

Sea ice formation near the Antarctic coast rejects brine, which increases salinity in this area (Fig. 2g). During this process sea ice attains a δ18O of +1.4‰, leaving a slightly negative anomaly in the water. As sea-ice is exported away from the coast during the cold season, it also accumulates in iCESM snowfall with a δ18O ~−18‰. Summer melting of sea-ice and of the accumulated snow generates an annual mean net negative isotopic signal (Fig. 2c). Overall, sea ice (which includes the isotopic snowfall accumulation effect in iCESM) plays a key role in mixed layer salinity (Fig. 2g, h) (39%), but less for mixed layer δ18Osw (Fig. 2c, d) (32%), These simple budget considerations described here already point to δ18Osw near Antarctica as a suitable proxy to probe ice-sheet instabilities.

The emergence of the Antarctic ice-sheet freshwater discharge

The projected late 21st-century anomaly patterns of δ18Osw (Fig. 1f) and SSS (Fig. 1e) in the IFD-forced iCESM experiments (see Methods) are similar and reflect a pronounced freshening over the Ross Sea and a weaker in the Weddell Sea and elsewhere. The pattern aligns with observational studies that indicate a larger discharge from the West Antarctic ice-sheet and the Antarctic Peninsula, with a small offset due to increased snow accumulation in Eastern Antarctica40,41. Similar patterns have also been found in climate model projections42,43,44. According to our experiments, the IFD signal in δ18Osw gets advected mainly into the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 2) via the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).

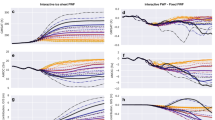

| Panels a, c show the SNR in SSS relative to unforced intraseasonal and interannual variability, respectively. While panels b, d provide the corresponding SNR values for δ18Osw. This figure offers a visual representation of the SNRs in SSS and δ18Osw attributed to ice-sheet freshwater discharge (IFD). SNRs were calculated using the forced response of SSS and δ18Osw to IFD from 2076 CE to 2085 CE (FWF-GHG585) as the signal. The noise was determined using 1σ of the monthly mean and annual mean from the control experiment. Orange stippling denotes the region where IFD force is applied.

To characterize how the amplitude of the forced IFD signal deviates from the natural variations in SSS and δ18Osw, we calculated the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) between forcing (difference of average values from 2076 to 2085 in the FWF-GHG585 IFD scenario (see Methods) and the longterm mean of control experiment) and natural variations on both intraseasonal and interannual timescales (Fig. 3). As expected from our initial discussion, the δ18Osw anomaly due to IFD is associated with a three times higher SNR (averaged from 90°S-60°S) compared to SSS, which also implies an earlier detectability (Fig. 3). More specifically, the interannual SNR in SSS anomalies shows a weak signal extending from the far-eastern basin near 60°E to the offshore region of the Amundsen Sea (Fig. 3c) and a strong signal in the Ross Sea. The latter can be attributed to the large IFD applied in the FWF-GHG585 scenario in this area (Supplementary Fig. 3c), and the corresponding freshening. The SNR for δ18Osw also shows a considerable anomaly in the western Weddell Sea (Fig. 3d). For practical purposes, however, regular measurements of δ18Osw in the Pacific sector would be most suitable for identifying the effect of anthropogenic IFD.

To further illustrate when and how quickly IFD pushes SSS and δ18Osw anomalies outside the range of the natural variability we calculated kernel density estimates from the scatter diagram of SSS and δ18Osw for ocean grid points between 90°S-70°S for different time periods (phases 1–5) (Fig. 4). The grey ellipses in Fig. 4 show the 1, 2, and 4σ range of natural variability for present-day conditions (from 100 years long control experiment). Mean SSS and δ18Osw values from the control experiment are shown as a black square (33.5 psu with 1σ = 0.4 psu and −0.7‰ with 1σ = 0.2‰, respectively). The red marks and ellipses correspond to the IFD forced responses in SSS and δ18Osw resulting from the Antarctic IFD input of fresh (0 psu) and isotopically depleted (−32‰) relative to seawater. As time progresses, we see an overall shift towards fresher SSS and more negative δ18Osw values and a steepening of the regression slope. In phase 1, the forced response in δ18Osw exceeds the 1σ natural boundary after the first five years of successive IFD input from the ice-sheet model scenario. This highlights that δ18Osw exhibits a much stronger response (−0.2‰) around 2010 compared to SSS, which shifts by −0.1 psu from the background value. In phase 5 the overlap between the kernel density and the control range has diminished further, and the slope of the regression, which is commonly used to characterize water masses27,36, has changed dramatically, indicating a clear emergence of the anthropogenic IFD signal relative to the internal variability. The δ18Osw anomalies in Phases 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 between 90°S and 70°S (−0.17, −0.24, −0.32, −0.41, and −0.97‰, respectively) correspond to 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 1.3, and 3.0% of the isotopic value of the IFD input (−32‰).

| A scatter plot of SSS and δ18Osw of ocean grid points over 90°S-70°S at the surface level is presented with ellipses providing probabilistic representations. The grey ellipses illustrate the 1 to 4σ probabilistic area of SSS and δ18Osw in the control experiment during 2001–2100 (n = 81400), centered on the black-squared mark representing the averaged values. The top and right-hand side panels show probabilistic density functions of SSS and δ18Osw, respectively. Colored ellipses present 1σ probabilistic areas for ten years (n = 8140) in each sequential 10-year interval from phase 1 to phase 5. Phases 1 through 5 are calculated at 10-year intervals, beginning in 2006 CE and continuing every decade thereafter. Consequently, phase 1 represents the period from 2006 to 2015 CE, roughly corresponding to the year 2010 CE. The phases 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 corresponds to the years 2010, 2020, 2030, 2040, and 2050 CE, respectively. Colored ellipses highlight responses from the combined climate and source effects (red, FWF-GHG585) and climate effects only (green, FWF0-GHG585). Mean SSS and δ18Osw values in the five sequential time phases are denoted by colored square marks.

To better quantify the time of emergence (ToE), we study the time evolution of SSS and δ18Osw for two grid points in the Atlantic and Pacific sectors of the Southern Ocean with contrasting interannual SNR values in δ18Osw (Supplementary Fig. 4). The low and high SNR values for SSS at these grid points in FWF-GHG585 are 1 and 9, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4a), whereas the corresponding values for δ18Osw are 4 and 43 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The time-series of simulated annual mean δ18Osw and SSS anomalies for three experiments FWF119, FWF245, and FWF-GHG585 (color) in comparison with the control experiment (gray) reveal that for low SNR in the Atlantic sector the forced SSS response still remains within the range of natural variability (Supplementary Fig. 4c). In contrast, the Atlantic sector, IFD signal in δ18Osw for the FWF-GHG585 scenario emerges from the natural noise around the year 2061 CE (Supplementary Fig. 4d). For the Pacific sector, both variables show emerging anthropogenic IFD trends in SSS and δ18Osw (Supplementary Fig. 4e, f). From the figure, we can estimate a ToE for δ18Osw anomalies (year of consecutive exceedance of 4-σ natural variability level) of around 2030 CE, for both FWF245 and FWF-GHG585 forcing scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 4f). In contrast, the ToE in the SSS anomaly in FWF-GHG585 was calculated to occur in 2066 CE, 36 years later than the equivalent ToE in δ18Osw (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

The analysis of ToE using δ18Osw and SSS anomalies at all grid points in three scenarios offers new insights into the timing of the IFD signals and their regional dependence (Fig. 5). In FWF119 the forced IFD signal in SSS remains non-emergent (Fig. 5d). For FWF245 and FWF-GHG585, the Ross Sea SSS anomalies start to emerge within the next 10–40 years, whereas elsewhere the emergence will be relatively late. This is in contrast to the ToE in the δ18Osw anomalies, which according to our experiments can already be detected for the FWF119 discharge scenario by 2010–2020 CE, despite the weak IFD forcing amplitude (Fig. 5a). The spatial pattern of ToE spreads from the Ross Sea to the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean, showing later emergence times as the distance increases from the Antarctic continent. This effect can be mostly explained by the overall dilution effect (Figs. 1f and 3b), and further intensification by the freshwater-induced shoaling of the mixed layer. Both the δ18Osw-FWF245 and δ18Osw-FWF-GHG585 exhibit an even broader region of ToE around Antarctica with values ranging from 2010 CE-2045 CE, exhibiting an earlier timing of the IFD signal near the Ross Sea (Fig. 5b, c).

| Forced response in δ18Osw and SSS from individual scenarios were used to calculate a ToE- δ18Osw (FWF119), b ToE- δ18Osw (FWF245), c ToE- δ18Osw (FWF-GHG585), d ToE-SSS (FWF119), e. ToE-SSS (FWF245), and f ToE-SSS (FWF-GHG585). ToE is defined as the final year (Common Era) in which the annual mean anomalies of surface δ18Osw (or SSS) fall below the local threshold. The bright dotted region in a–c denotes where the amplitude of the δ18Osw anomaly at the ToE exceeds the typical analytical precision (−0.1‰) of current commercial laser spectrometry.

The absence of an emergent IFD signal over the Weddell Sea in δ18Osw-FWF245 (Fig. 5b) and SSS-FWF-GHG585 (Fig. 5f) can be attributed to a combination of factors: (1) the IFD forcing pattern (Supplementary Fig. 3c), (2) higher natural variability in δ18Osw and SSS on intraseasonal to interannual timescales (Figs. 1a–d), and (3) an anomalous upper ocean circulation pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2), related to upper ocean horizontal divergence, which in turn increases the upwelling of IFD-unperturbed seawater. This leads to a dilution of the anthropogenic IFD signal in the Weddell Sea area. In contrast, the IFD signal in the Ross Sea Gyre persists longer, due to higher integrated IFD fluxes and weaker divergence.

The early emergence of the δ18Osw-FWF-GHG585 near the ACC region (60°S) (Fig. 5c) is primarily driven by intensified upper ocean stratification. Enhanced surface warming and IFD-originated freshening will increase Southern Ocean upper ocean stratification, which will in turn reduce the upwelling of Circumpolar Deep Water. Furthermore, reduced sea ice formation and brine rejection will slow down the Bottom Water Formation near Antarctica which weakens the poleward surface transport, inducing an equatorward upper ocean velocity anomaly. This process aligns with the location where IFD is applied in our model experiments and helps distribute the IFD water further into the ACC region. In the ACC region, a 2° poleward shift of the Westerlies45,46 and the corresponding equatorward Ekman transport can further amplify this effect. However, the latitudinal range of this shift is somewhat distant from the IFD source region. We expect that the poleward shift of the Westerlies will have only a minor role compared to buoyance-driven shifts in meridional velocities.

Identifying ideal sampling areas

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometers (IRMS) have been widely used47 to measure the isotopic composition of seawater in the world’s oceans with an analytical precision of about 0.03‰. Using this method, it has been possible to determine the contribution of different water mass endmembers, including contributions from ice-shelf and iceberg melting26,27,29,48. Alternatively, cavity ring-down laser spectroscopy (CRDS) can measure seawater isotopes in a continuous mode with a typical precision for δ18Osw of about 0.1‰29,49. In discrete mode, injecting water samples into a vaporizer can achieve an even higher precision of about 0.025‰50. Given the simulated δ18Osw anomaly from IFD (<−0.6‰ over the next six decades shown in Fig. 1f), the anthropogenic IFD signal should already be detectable now in some regions using laser spectroscopy, as further illustrated by the white hatching in Fig. 5a–c.

Our ToE results using δ18Osw highlight an ideal sampling area where signals are emergent early and measurable within the range of analytical precision (white hatching in Fig. 5a–c) of CRDS. The zonal averaged ToE over the Ross Sea-Amundsen Sea-Antarctic Peninsula (130°E–300°E) reveals an earlier ToE pattern in all three scenarios compared to the Weddell Sea. Although detectability in FWF119 is limited, the common trend from 80°S to 70°S in both FWF245 and FWF-GHG585 shows that the IFD signal in the Ross Sea has already emerged since 2020 CE. However, the Ross Sea gyre quickly dilutes the IFD source water, limiting the detectability to a region poleward of 70°S.

Ice-sheet freshwater discharge and other greenhouse warming effects on δ18Osw

Apart from the direct IFD (source water) effect on Southern Ocean δ18Osw, we need to consider the contribution of other indirect climate effects51 due to (1) increased future precipitation52, (2) projected reduction in sea ice35,53,54,55, and (3) surface warming. To estimate their contributions to δ18Osw, we examined four tendency terms illustrating the effects from (1) to (3). Each term represents the combined effect of the anomalous flux of precipitation (or sea ice) to the ocean and the mean δ18O value of precipitation (or sea ice meltwater) as well as the combined effect of the mean flux of precipitation (or sea ice) and anomalous δ18O value of precipitation (or sea ice meltwater). These climate responses have complex feedbacks within the climate system15,56 and can influence the water isotope composition57,58,59. For instance, in the case of enhanced precipitation with surface warming, the additional input of depleted precipitation δ18O (relative to seawater) can result in a negative anomaly in δ18Osw of about −0.05‰ year−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Conversely, surface warming can cause an anomalous enrichment of precipitation δ18O through moderate fractionation during the evaporating process32; but this effect is negligible (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Additionally, surface warming increases sea ice melting. Less sea-ice (Supplementary Fig. 5b) will be generated and less snow will accumulate on top of the sea-ice which in turn increases δ18Osw by about 0.15‰ year−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5d)35,53,54,55. Climate change may influence isotopic contributions from precipitation and sea ice, however, we expect these effects to be minor compared to the magnitude of the IFD-induced δ18Osw anomalies found in our experiments.

To demonstrate the robustness of the source contribution in δ18O, originating from the future IFD and greenhouse gas warming, we conducted additional paired transient iCESM experiments, namely FWF0-GHG585 (Supplementary Table 1). FWF0-GHG585 is forced by the same SSP585 greenhouse gas forcing and the IFD as FWF-GHG585 but uses an idealized IFD source δ18Oice = 0‰ (see Methods). Therefore we can isolate the source effect on δ18Osw (Fig. 6i–l) by calculating the difference between FWF-GHG585 (representing total climate and source effects, Fig. 6a–d) and FWF0-GHG585 (climate effect only, Fig. 6e–h). Four temporal snapshots of the mean surface δ18Osw anomaly examine the evolution of the IFD source effect and the climatic effect (Fig. 6). Stippling in Fig. 6a–h represents statistically significant areas (p < 0.01), determined using a Welch’s t-test, while shaded areas in Fig. 6i–l indicate statistically significant areas in both FWF-GHG585 and FWF0-GHG585 forced responses in δ18Osw. The relative percentage changes of source effects (Fig. 6i–l) were calculated by dividing the respective source effect by the total change (Fig. 6a–d). In Phase B (2031–2035), the total changes due to the combined effects of source and climate become significant for most of the Southern Ocean (Fig. 6b).

| Upper panels show the 5-year time slice mean of the δ18Osw anomaly induced by the FWF-GHG585 perturbation across four distinct phases: a Phase A (2001–2025), b Phase B (2031–2035), c Phase C (2051–2055), and d Phase D (2076–2080). A freshwater perturbation experiment without the source (δ18Oice = 0‰, FWF0-GHG585) was also conducted in parallel, showing climate effects during the same time slices in e–h for Phase A, B, C and D, respectively. Stippling in a–h. indicates regions where δ18Osw anomalies during the time slices are statistically significant (p-values < 0.01) based on the Welch’s t-test. The approximated source effect of IFD remained in δ18Osw is shown in i–l, emphasizing statistical significance for both total change and climate effect. The percentage contribution of the source effect relative to the total change over 90°S-60°S was calculated as: (‘FWF-GHG5’-‘FWF0-GHG5’)/(‘FWF-GHG5’-CTR), representing the source effect divided by net changes multiplied by 100. Figure m. illustrates the annual mean δ18Osw of control (grey line), FWF-GHG585 (black line), and FWF0-GHG585 (dotted line) experiments. The grey boxes indicate the time span of the four phases.

Considering only the climate effect from FWF0-GHG585, we find that the scatter in the salinity/ δ18Osw space (Fig. 4, green) remains consistent with the natural variability (black) until the mid-21st century. Although the climate effect may reduce the advantage of utilizing δ18Osw as an IFD tracer due to changes in precipitation and sea ice in the future (Supplementary Fig. 5), the IFD source signal clearly persists throughout the warming future in Phase D and separates well from the noise (Fig. 6l). Based on our paired experiments with and without the IFD source effect, we estimated that the IFD accounts for 10%, 61%, 72%, and 83% of δ18Osw in Phases A, B, C, and D, respectively (Fig. 6i–l).

Summary and Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the future Antarctic IFD signal can be easily identified using δ18Osw measurements (Fig. 7). The results, obtained with a realistic isotope-enabled earth system model with recent model-based estimates of the IFD signal for three greenhouse gas emission scenarios, show that δ18Osw outperforms salinity as an indicator of ice-sheet melting. According to our numerical experiments, the anthropogenic IFD signal in δ18Osw arises first in the Ross Sea around 2020 CE. The corresponding Ross Sea SSS signal emerges above the natural background noise three decades later. We found that towards the end of the century, δ18Osw can account for up to 83% of direct IFD source effect, outweighing other future climatic effects (e.g., due to changes in sea ice and hydrological cycle) (Fig. 6l). These findings suggest that δ18Osw can serve as a valuable tool for detecting anthropogenic IFD originating from the Antarctic ice-sheet.

| A schematic introduces the various sources influencing the seawater oxygen isotope (δ18Osw) composition of the Southern Ocean. δ18Osw in the Southern Ocean depends on the fluxes of several freshwater inputs (such as sea ice meltwater, run-off, precipitation, and land-ice meltwater), along with their respective δ18O values. In association with Rayleigh distillation, lighter isotopes are preferentially fixed into the precipitation (~−8‰) and the Antarctic ice-sheet (−32‰) at the higher latitudes30,31,32,33,34. In contrast, during the freezing process, sea ice takes heavier isotopes (+1.4‰) from seawater35,36,37, resulting in a less pronounced impact on δ18Osw (−0.7‰). In iCESM sea-ice also includes accumulated snowfall. When sea-ice melts, the snowfall contribution usually overcompensates the positive isotopic fractionation effect in sea-ice – even in the annual mean. Therefore, to monitor ice-sheet melting, only two end-members need to be considered: δ18Osw and δ18Oice.

The ice-sheet influence in δ18Osw can also be traced back to the subsurface ocean, where we find a highly emergent pattern in δ18Osw in the subducted Antarctic Intermediate water (Supplementary Fig. 6a), which can be attributed mostly to the IFD source effect (Supplementary Fig. 6b). The low salinity water from the IFD also intensifies the upper ocean stratification and weakens Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) formation20,60,61. The resulting decreased vertical transport of the surface δ18Osw within the range of 200–1000 m which is depleted relative to mean seawater, can be seen as a positive anomaly near Antarctica in the vertical profile of anomalous isotopes (Supplementary Fig. 6b). In addition to monitoring only the surface seawater isotopes, additional information on the IFD may be contained in subsurface δ18Osw data, particularly in the AAIW area. Considering the early ToE observed in the Ross Sea area, a comprehensive analysis combining various tracers (e.g. bomb 14C, CFCs, and δD) along with δ18Osw in hydrographic data could facilitate the reconstruction of IFD trends.

Our results illustrate that the climate effect on δ18Osw during the 2076–2080 CE period in the FWF0-GHG585 scenario, associated with a 1.5 °C increase in surface temperature (not SST) over 90°S-60°S, accounts for less than 17% of the net change in δ18Osw (Fig. 6h). However, we need to consider that, unlike in the original LOVECLIP simulations, which provided the IFD estimates9, our model iCESM does not include an interactive ice-sheet model. Our experiments also ignore iceberg melting effects which can further influence surface temperatures12, sea ice growth, and salinity23,62. Furthermore, our iCESM simulation does not explicitly capture the subsurface melting from sub ice-shelf cavities10. How these additional processes may alter our main results needs to be further addressed in upcoming modeling studies with the next generation of fully coupled climate-ice-sheet models. Using IFD from a fully coupled climate-ice-sheet model1 represents our first attempt to account for some of these aspects. Future studies could further address the effects of regional patterns in δ18Oice and the roles of basal and iceberg melting. Given the relatively small contribution from other climate effects (Fig. 6e–h, Supplementary Fig. 5), we expect that our main results and ToE estimates (Fig. 5) at the surface should remain robust.

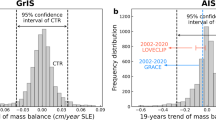

Other uncertainties that need to be considered in future work include i) the overall IFD scenario (Supplementary Fig. 3), which was obtained here from a fully coupled, albeit low-resolution climate-ice-sheet model; ii) the δ18O source value of the Antarctic IFD (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2) and iii) errors in the represented natural variability in salinity (Supplementary Fig. 7), sea ice (Supplementary Fig. 8), and δ18Osw. For ii), changing the IFD source (δ18Oice) from −38‰ to −32‰ did not yield notable effects on the ToE. To better understand the sensitivity of δ18Oice above −32‰, we calculated δ18Osw anomalies for δ18Oice values of −15‰, −20‰, and −25‰ using a linear scaling and extrapolation derived from FWF-GHG585 experiments at δ18Oice values of −38‰ and −32‰. The estimated δ18Osw anomalies resulting from the δ18Oice of below −20‰ would cause a delay in the ToE of about six decades compared to the ToE in −32‰ (Supplementary Figs. 9a, b). An IFD signal can be effectively captured with a source value below −25‰ (Supplementary Fig. 9c).

So far δ18Osw measurements from the Southern Ocean rely mostly on hydrographic sampling and subsequent laboratory analysis using an IRMS26,27. Although these analytical methods prioritize high precision in δ18Osw, they do not provide high spatial and temporal coverage47. To overcome this limitation, the underway use of portable CRDS that can measure δ18Osw on research cruises to the Southern Ocean would be an optimal way for identifying Antarctic IFD signals in the ocean29,49 and estimating IFD budgets.

Methods

Freshwater perturbation experiments in isotope-enabled Community Earth System Model

To investigate the impact of anthropogenic Antarctic IFD on surface δ18Osw, we conducted a series of freshwater perturbation experiments using the isotope-enabled Community Earth System Model (iCESM)63, based on CESM, version 1.2.2, with a resolution of 2° for the atmosphere and 1° for the ocean. The freshwater forcings (Supplementary Fig. 3) were obtained from a fully coupled ice-sheet-earth system model of intermediate complexity9 (LOVECLIP), which had been run with SSP1.1-9, SSP2.4-5, and SSP5.8-5 greenhouse gas emission scenarios, yielding to 0.33, 0.6, and 1.4 meters sea level equivalent of cumulative freshwater forcing by 2100 CE, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

First, we ran the iCESM for 1,000 years with present-day boundary conditions and without freshwater perturbation. Initialized from the final state of this control experiment (CTR), we then ran a series of forcing experiments. The first series of freshwater perturbation experiments (FWF119 and FWF245) uses the LOVECLIP low and medium greenhouse gas emission simulations, corresponding to SSP1.1-9, SSP2.4-5 from 2001 to 2100 CE (Supplementary Fig. 3a) with a characteristic pattern obtained from LOVECLIP (Supplementary Fig. 3c, more information below), and a δ18O forcing value of −32‰, (see below). These experiments were run without increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and just focused on the effect of IFD on seawater isotopes. For a higher greenhouse gas emission scenario with SSP5.8-5 forcing from 2001-2100 CE (FWF-GHG585), we applied both IFD with a source value of −32‰ and increasing greenhouse gas concentrations. Forcings in SSP5.8-5 include time-evolving changes in CO2, CH4, N2O, CFC-11, and CFC-1264, but not aerosols as well as land-use changes (Supplementary Fig. 10c). To further isolate the anthropogenic IFD signal over Antarctica from other greenhouse warming effects on sea ice and precipitation51, we ran a paired experiment (FWF0-GHG585) with equivalent forcing as FWF-GHG585 but without the source value (δ18Oice = 0‰). By comparing the results of these two experiments, we can differentiate the IFD source effect from other freshwater-driven climate effects on δ18Osw (Figs. 4 and 6). More information about the experiments and details can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

To the best of our knowledge, iCESM has not yet been coupled to a fully interactive bi-hemispheric ice-sheet, ice-shelf, iceberg model to provide more realistic IFD and isotopic forcing. We tried to mitigate this limitation by using IFD data from such a coupled model, albeit of lower resolution and reduced complexity in atmospheric dynamics1, and force iCESM with it.

Forcing masks

We determined the spatial pattern of future Antarctic IFD between 2001 and 2100 CE using the output of the fully coupled Earth System Model9 (LOVECLIP) (Supplementary Fig. 3c). LOVECLIP model categorizes IFD outputs into the basal melt, cliff melt, face melting, and iceberg calving. However, we consolidated these into net IFD forcing to simplify our model experiments. More specifically we conducted an Empirical Orthogonal Function analysis for the net IFD. The sum of Principal Components (PC)1, PC2, and PC3 accounts for 68% of the total variance in net IFD from 2001 to 2100 CE. We used this spatial pattern as a weighting factor to distribute the annual varying freshwater forcing spatially (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The forcing is applied every month, with values at individual grid points scaling with the spatial weighting factor. Unlike previous studies that relied on the simplified basin or coastal masks for freshwater perturbations11,15,65, our approach accounts for the fact that iceberg calving from the Western Antarctic ice-sheet will be the primary source of IFD in future and Eastern Antarctic contributions will be small (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Isotopic composition of the Antarctic ice-sheet freshwater discharge forcing

To determine the representative δ18O of the Antarctic IFD (δ18Oice), we analyzed ice core data from the National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov). Our analysis focused on ice cores with available δ18O data that provided a vertical representation of the ice-sheet (as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1), which allowed us to capture the melting of the bottom ice-sheet within the cavity and ice-calving. Samples that only provided single-level isotopic information were excluded. The selected ice core data include Siple Dome66, Gomez67, Byrd68, Taylor Dome69, Talos Dome70 (Supplementary Table 2). To define the source δ18O value for the Antarctic IFD, we averaged the last 200 meters of δ18O values from each ice core. The resulting δ18O values ranged from −23‰ to −40‰, depending on location (Supplementary Table 2), with the lowest value found in Byrd and Talos Dome (−40‰) and the most enriched one in Gomez (−23‰) relative to the other ice core we listed above. To account for regional differences in IFD, we calculated a weighted mean of the δ18O values, considering the reported recent regional ice-sheet mass balance from different areas41. The resulting weighted mean δ18Oice of the Antarctic IFD was determined to be −32‰.

Contributions of four main freshwater inputs to mixed layer δ18Osw and salinity

To determine the relative contribution of four major sources of freshwater inputs (precipitation, liquid run-off mostly from snow cap melting, and sea ice) to Southern Ocean δ18Osw and salinity, we employed a budget-based approach. Using monthly data from the present-day iCESM control experiment (CTR), we obtained freshwater flux, δ18O of freshwater sources, δ18Osw, and SSS values. Freshwater flux (m year−1) was normalized by the annual mean ocean mixed layer depth (m) and multiplied by monthly differences of δ18O (‰) and SSS salinity (psu) relative to the background seawater. Monthly freshwater contributions to the upper ocean layer were then averaged annually. Results indicated the spatial mean contribution averaged over 90°S-60°S for PME, liquid run-off, and sea ice to mixed layer δ18Osw of −0.05, −0.04, and −0.04‰ year−1, respectively. The freshwater contributions to mixed layer salinity were −0.1, −0.07, and −0.1 psu year−1 for PME, liquid run-off, and sea ice, respectively.

Time of emergence

To determine the Time of Emergence (ToE) of the IFD signal, we first calculated the standard deviation (1σ) of both annual mean SSS and δ18Osw from a 100-year control experiment. To set an appropriate threshold to capture the IFD signal from the forced response, we evaluated various thresholds ranging from 1 to 4σ71. We found that the 4σ-threshold provided the most reliable results (dotted red lines in Supplementary Fig. 4c–f). The ToE in a specific grid point was then defined as the final year in which the annual mean anomalies of both SSS and δ18Osw dropped below the local 4σ threshold. By applying this method, we avoided multiple ToE detections, which can occur due to decadal variability in the forcings (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Evaluation of modeled natural variability of salinity and sea ice with ORAS5

The Ocean Reanalysis System 5 (ORAS5) is a reanalysis system for ocean and sea ice data that utilizes five ensemble members to provide comprehensive coverage from 1979 to the present. We used monthly datasets of sea surface salinity (sosaline) and sea ice (ileadfra) at a resolution of 1° × 1° from 1979 to 2018 (http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/dods/public_data/Reanalysis_Data/ORAS5/1x1_grid/) to evaluate the natural variability in iCESM. While the iCESM model has a negative bias in salinity (0.5 psu) when compared to the ORAS5 climatological mean, the large-scale spatial patterns of its annual mean climatology and interannual variability are well represented (Supplementary Figs. 7, 8). Evaluating the simulated interannual variability in SSS and sea ice within the reanalysis dataset is important because the interannual standard deviation affects the signal-to-noise ratio, which is critical in determining the ToE of the IFD (Supplementary Fig. 4). Of particular importance is the natural variability in sea ice, which can increase the gap in the detectability of IFD in SSS and δ18Osw. Our modeled amplitudes of natural variability in sea ice and SSS (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Figs. 7, 8) fall within the observed range that determines the calculation of ToE, making it reasonable to interpret the results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this paper are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11236654. This dataset72 provides insights into the feasibility of monitoring Antarctic ice-sheet freshwater discharge using seawater oxygen isotopes.

Code availability

The codes73 are written in Jupyter-Notebook to analyze the dataset and generate the figures. They are available on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/11237280.

References

Davis, P. E. D. et al. Suppressed basal melting in the eastern Thwaites Glacier grounding zone. Nature 614, 479–485 (2023).

Schmidt, B. E. et al. Heterogeneous melting near the Thwaites Glacier grounding line. Nature 614, 471–478 (2023).

Alley, K. E. et al. Two decades of dynamic change and progressive destabilization on the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf. Cryosphere 15, 5187–5203 (2021).

Favier, L. et al. Retreat of Pine Island Glacier controlled by marine ice-sheet instability. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 117–121 (2014).

McMillan, M. et al. Increased ice losses from Antarctica detected by CryoSat‐2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3899–3905 (2014).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H. & Scheuchl, B. Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3502–3509 (2014).

Herraiz‐Borreguero, L. et al. Basal melt, seasonal water mass transformation, ocean current variability, and deep convection processes along the Amery Ice Shelf calving front, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 121, 4946–4965 (2016).

Warner, R. C. et al. Rapid formation of an Ice Doline on Amery Ice Shelf, East Antarctica. Geophys Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091095 (2021).

Park, J. Y. et al. Future sea-level projections with a coupled atmosphere-ocean-ice-sheet model. Nat. Commun. 14, 636 (2023).

DeConto, R. M. et al. The Paris Climate Agreement and future sea-level rise from Antarctica. Nature 593, 83–89 (2021).

Park, W. & Latif, M. Ensemble global warming simulations with idealized Antarctic meltwater input. Clim. Dyn. 52, 3223–3239 (2018).

Pauling, A. G., Smith, I. J., Langhorne, P. J. & Bitz, C. M. Time-dependent freshwater input from ice shelves: impacts on Antarctic Sea ice and the Southern Ocean in an Earth System Model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10,454–410,461 (2017).

Bintanja, R., van Oldenborgh, G. J., Drijfhout, S. S., Wouters, B. & Katsman, C. A. Important role for ocean warming and increased ice-shelf melt in Antarctic sea-ice expansion. Nat. Geosci. 6, 376–379 (2013).

Bintanja, R., Van Oldenborgh, G. & Katsman, C. The effect of increased fresh water from Antarctic ice shelves on future trends in Antarctic sea ice. Ann. Glaciol. 56, 120–126 (2015).

Bronselaer, B. et al. Change in future climate due to Antarctic meltwater. Nature 564, 53–58 (2018).

Fogwill, C. J., Phipps, S. J., Turney, C. S. M. & Golledge, N. R. Sensitivity of the Southern Ocean to enhanced regional Antarctic ice sheet meltwater input. Earth’s Future 3, 317–329 (2015).

Stouffer, R. J., Seidov, D. & Haupt, B. J. Climate response to external sources of freshwater: North Atlantic versus the Southern Ocean. J. Clim. 20, 436–448 (2007).

Oh, J. H. et al. Impact of Antarctic meltwater forcing on East Asian climate under greenhouse warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089951 (2020).

Menviel, L., Timmermann, A., Timm, O. E. & Mouchet, A. Climate and biogeochemical response to a rapid melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet during interglacials and implications for future climate. Paleoceanography 25, PA4231 (2010).

Anilkumar, N. et al. Recent freshening, warming, and contraction of the Antarctic bottom water in the Indian Sector of the Southern Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.730630 (2021).

Vizcaíno, M., Mikolajewicz, U., Jungclaus, J. & Schurgers, G. Climate modification by future ice sheet changes and consequences for ice sheet mass balance. Clim. Dyn. 34, 301–324 (2009).

Ma, H. & Wu, L. Global teleconnections in response to freshening over the Antarctic Ocean. J. Clim. 24, 1071–1088 (2011).

Schloesser, F., Friedrich, T., Timmermann, A., DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Antarctic iceberg impacts on future Southern Hemisphere climate. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 672–677 (2019).

Rignot, E. et al. Recent Antarctic ice mass loss from radar interferometry and regional climate modelling. Nat. Geosci. 1, 106–110 (2008).

Velicogna, I., Sutterley, T. C. & van den Broeke, M. R. Regional acceleration in ice mass loss from Greenland and Antarctica using GRACE time-variable gravity data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8130–8137 (2014).

Aoki, S., Kobayashi, R., Rintoul, S. R., Tamura, T. & Kusahara, K. Changes in water properties and flow regime on the continental shelf off the Adélie/George VLand coast, East Antarctica, after glacier tongue calving. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 6277–6294 (2017).

Pan, B. J., Vernet, M., Reynolds, R. A. & Mitchell, B. G. The optical and biological properties of glacial meltwater in an Antarctic fjord. PLoS One 14, e0211107 (2019).

Jia, R. et al. Freshwater components track the export of dense shelf water from Prydz Bay, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 196, 105023 (2022).

Akhoudas, C. et al. Ice Shelf Basal melt and influence on dense water outflow in the Southern Weddell Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 125 https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jc015710 (2020).

Dansgaard, W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. tellus 16, 436–468 (1964).

Craig, H. & Gordon, L. I. Deuterium and oxygen 18 variations in the ocean and the marine atmosphere. In Tongiorgi Stable Isotopes in Oceanographic Studies and Paleotemperatures, 9–130 (Laboratory di Geologia Nucleare, Pisa, Italy, 1965).

Vystavna, Y., Matiatos, I. & Wassenaar, L. I. Temperature and precipitation effects on the isotopic composition of global precipitation reveal long-term climate dynamics. Sci. Rep. 11, 18503 (2021).

Thurnherr, I. et al. Meridional and vertical variations of the water vapour isotopic composition in the marine boundary layer over the Atlantic and Southern Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 5811–5835 (2020).

Dansgaard, W. Oxygen-18 abundance in fresh water. Nature 174, 234–235 (1954).

Toyota, T. et al. Oxygen isotope fractionation during the freezing of sea water. J. Glaciol. 59, 697–710 (2017).

Benetti, M. et al. Variability of sea ice melt and meteoric water input in the surface Labrador Current off Newfoundland. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 121, 2841–2855 (2016).

Moore, K., Fayek, M., Lemes, M., Rysgaard, S. & Holländer, H. M. Fractionation of hydrogen and oxygen in artificial sea ice with corrections for salinity for determining meteorological water content in bulk ice samples. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 142, 93–99 (2017).

Toyota, T. et al. Oxygen isotope fractionation during the freezing of sea water. J. Glaciol. 59, 697–710 (2013).

Melling, H. & Moore, R. M. Modification of halocline source waters during freezing on the Beaufort Sea shelf: evidence from oxygen isotopes and dissolved nutrients. Continent. Shelf Res. 15, 89–113 (1995).

Smith, B. et al. Pervasive ice sheet mass loss reflects competing ocean and atmosphere processes. Science 368, 1239–1242 (2020).

Rignot, E. et al. Four decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1095–1103 (2019).

Naughten, K. A. et al. Future projections of Antarctic Ice shelf melting based on CMIP5 scenarios. J. Clim. 31, 5243–5261 (2018).

Seroussi, H. et al. ISMIP6 Antarctica: a multi-model ensemble of the Antarctic ice sheet evolution over the 21st century. Cryosphere 14, 3033–3070 (2020).

Siahaan, A. et al. The Antarctic contribution to 21st-century sea-level rise predicted by the UK Earth System Model with an interactive ice sheet. Cryosphere 16, 4053–4086 (2022).

Gray, W. R. et al. Poleward shift in the Southern Hemisphere westerly winds synchronous with the deglacial rise in CO2. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 38, e2023PA004666 (2023).

Menviel, L. C. et al. Enhanced Southern Ocean CO2 outgassing as a result of stronger and poleward shifted southern hemispheric westerlies. Biogeosciences 20, 4413–4431 (2023).

Reverdin, G. et al. The CISE-LOCEAN seawater isotopic database (1998–2021). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 2721–2735 (2022).

Meredith, M. P. et al. Anatomy of a glacial meltwater discharge event in an Antarctic cove. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20170163 (2018).

Bass, A. M. et al. Continuous shipboard measurements of oceanic δ18O, δD and δ13CDIC along a transect from New Zealand to Antarctica using cavity ring-down isotope spectrometry. J. Mar. Syst. 137, 21–27 (2014).

Hutchings, J. A. & Konecky, B. L. Optimization of the Picarro L2140-i cavity ring down spectrometer for routine measurement of triple oxygen isotope ratios in meteoric waters. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 2022, 1–31 (2022).

Zhu, J. et al. Investigating the direct meltwater effect in terrestrial oxygen‐isotope paleoclimate records using an isotope‐enabled earth system model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl076253 (2017).

Sadai, S., Condron, A., DeConto, R. & Pollard, D. Future climate response to Antarctic Ice Sheet melt caused by anthropogenic warming. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz1169 (2020).

Faber, A.-K., Møllesøe Vinther, B., Sjolte, J. & Anker Pedersen, R. How does sea ice influence δ18O of Arctic precipitation? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 5865–5876 (2017).

O’Neil, J. R. Hydrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation between ice and water. J. Phys. Chem. 72, 3683–3684 (1968).

Brennan, C., Meissner, K., Eby, M., Hillaire‐Marcel, C. & Weaver, A. Impact of sea ice variability on the oxygen isotope content of seawater under glacial and interglacial conditions. Paleoceanography 28, 388–400 (2013).

Noone, D. & Sturm, C. Comprehensive dynamical models of global and regional water isotope distributions. Isoscapes: Understanding movement, pattern, and process on Earth through isotope mapping, 195–219 (2010).

LeGrande, A. N. & Schmidt, G. A. Ensemble, water isotope-enabled, coupled general circulation modeling insights into the 8.2 ka event. Paleoceanography 23, PA3207 (2008).

Rohling, E. J. & Bigg, G. R. Paleosalinity and δ18O: a critical assessment. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 103, 1307–1318 (1998).

Schlosser, E. & Oerter, H. Seasonal variations of accumulation and the isotope record in ice cores: a study with surface snow samples and firn cores from Neumayer station, Antarctica. Ann. Glaciol. 35, 97–101 (2002).

Silvano, A. et al. Freshening by glacial meltwater enhances melting of ice shelves and reduces formation of Antarctic Bottom Water. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap9467 (2018).

Toggweiler, J. & Samuels, B. Effect of sea ice on the salinity of Antarctic bottom waters. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 25, 1980–1997 (1995).

Martin, T. & Adcroft, A. Parameterizing the fresh-water flux from land ice to ocean with interactive icebergs in a coupled climate model. Ocean Model. 34, 111–124 (2010).

Brady, E. et al. The connected isotopic water cycle in the Community Earth System Model version 1. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2547–2566 (2019).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim. Change 109, 213 (2011).

Friedrich, T. & Timmermann, A. Millennial-scale glacial meltwater pulses and their effect on the spatiotemporal benthic δ18O variability. Paleoceanography 27, PA3215 (2012).

Brook, E. J. et al. Timing of millennial-scale climate change at Siple Dome, West Antarctica, during the last glacial period. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1333–1343 (2005).

Thomas, E., Dennis, P., Bracegirdle, T. J. & Franzke, C. Ice core evidence for significant 100‐year regional warming on the Antarctic Peninsula. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L20704 (2009).

Pedro, J. et al. The last deglaciation: timing the bipolar seesaw. Climate 7, 671–683 (2011).

Steig, E. J. et al. Wisconsinan and Holocene climate history from an ice core at Taylor Dome, western Ross Embayment, Antarctica. Geogr. Annaler: Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 82, 213–235 (2000).

Stenni, B. et al. Expression of the bipolar see-saw in Antarctic climate records during the last deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 4, 46–49 (2011).

Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. Time of emergence of climate signals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L01702 (2012).

Kim, H. Data for Kim et al. 2024, Communication Earth and Environment. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11236654 (2024).

Kim, H. Scripts for Kim et al. 2024, Communication Earth and Environment. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11237280 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Republic of Korea under IBS-R028-D1. The model experiments were conducted on the IBS/ICCP supercomputer Aleph, 1.43 Peta flops high-performance Cray XC50-LC Skylake computing system with 18,720 processor cores, 9.59 PB storage, and 43 PB tape archive space. We also acknowledge the support of KREONET.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. initially proposed the research idea. H.K. conducted model experiments, data processing, and analysis under A.T.’s supervision. H.K. wrote the manuscript and produced all the figures. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and improving the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Andrew Hennig, William Gray and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: José Luis Iriarte Machuca and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Timmermann, A. Seawater oxygen isotopes as a tool for monitoring future meltwater from the Antarctic ice-sheet. Commun Earth Environ 5, 343 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01514-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01514-4