Abstract

The paradigm of lunar crust formation has been widely applied to other terrestrial bodies, but the nature of early crust building on the Moon remains enigmatic. Here we report non-Apollo-like highland clasts from the Chang’e-5 mission and find high-alumina melts enclosed in a noritic anorthosite. Geochemistry and phase equilibria modeling suggest that the melt is compositionally parental to lunar magnesian-suite rocks, and was sourced from a plagioclase-bearing, orthopyroxene-dominated upper mantle ( ~ 4.5 kbar and 1225°C). It was formed as a direct consequence of upper mantle melting at the onset of gravitational instability. We propose a continuous early crust formation on the Moon, started from multiple anorthositic cumulate flotations, to upper mantle melting caused by small-scale, in-situ overturn, and eventually ended up by decompression melting of lower mantle cumulates following large-scale, global overturn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding crust formation is a vital part of comprehending the evolution of planets. Our knowledge of lunar crust formation has greatly benefited from the Apollo missions, which brought back highland crustal lithologies of ferroan anorthosites (FANs) and high magnesian-suite rocks (HMS) that define distinct crystallization trends in the plot of An (molar Ca/(Ca + Na + K) × 100) of plagioclase versus Mg# (molar Mg/(Mg + Fe) × 100) of mafic minerals1. The FANs show a vertical trend with mafic minerals having Mg# < 70 at invariant An of plagioclase ( > 94), while the HMS evolve along the “normal” trend of simultaneous decrease in An and Mg# (Fig. 1a). The discovery of FANs and HMS leads to the proposal of a broad two-stage crust building event on the Moon: the first stage involved the flotation of FANs crystallized from the lunar magma ocean (LMO), forming the primitive lunar crust2,3,4; and the second was featured by melting of a likely hybridized source triggered by density-driven mantle overturn, forming melts parental to HMS5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

a Graph of anorthite component (mol%) of plagioclase versus Mg# of mafic minerals in the CE-5 highland clasts. Colored symbols are average values from ref. 26 and this study, and the gray symbol (Zeng 22) is from ref. 27. The bars represent the ranges of Mg# of mafic mineral and An of plagioclase. Compositional fields for the Apollo samples and meteoritic anorthositic clasts are from ref. 75 and ref. 5 (after ref. 17) respectively. b Average CI-normalized REE patterns of plagioclase in the CE-5 highland clasts. The REE pattern ranges of the Apollo HMS30,31, Apollo FAN76,77, Apollo MAN31, meteoritic anorthositic clasts16,78,79, and a meteoritic HMS (NWA10401; dashed)32 are shown for comparison. The CI chondritic values are from ref. 80. An: anorthosite, T.A: troctolitic anorthosite, G.A: gabbroic anorthosite, N.A: noritic anorthosite, A.N: anorthositic norite, A.T: anorthositic troctolite, Ol: olivine, Pyx: pyroxene. Data are reported in Supplementary Data 1, 2.

However, the nature of early crust building process on the Moon remains enigmatic. First, the representativeness of the Apollo-returned highland crustal lithologies for the global Moon is questionable. Remote-sensing data from the post-Apollo orbital satellites12,13 and studies of lunar meteorites14,15,16,17 recognized the presence of magnesian anorthositic lithologies which are nearly absent in the Apollo collections. Second, geochronological data and numerical modeling suggest that mantle overturn appears to be coeval with LMO solidification18,19,20, and that HMS formed near-contemporaneously with FANs21,22. It may hint for a rapid reworking of the lunar crust following the initial FAN crustal formation23, or alternatively that the so-called first-stage crust building was accomplished via multiple plagioclase flotations that may have chronologically and geodynamically extended to the Mg-suite magmatism17,24.

The Chang’e-5 (CE-5) mission returned samples from the northern Oceanus Procellarum of the Moon (51.916 °W, 43.058 °N), distant from the landing sites of the Apollo and Luna missions25. Here, we find six highland clasts in two lunar regolith breccias (CE5C0800YJYX132GP). These highland lithologies display unique mineralogical and geochemical characteristics that have not been observed in the Apollo-returned samples, shedding new light on the nature of early crust building on the Moon.

Results and discussion

The highland clasts were first identified by using a combined technique of scanning electron microscopy analysis (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information for details). Detailed mineralogy and geochemistry of the six highland clasts were further characterized by Raman spectroscopy, electron microprobe analysis (EPMA) and in-situ laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) trace-element analysis (see Methods and data in Supplementary Data 1–2).

Non-Apollo-like highland materials in the CE-5 samples

First, no FANs have been found in the CE-5 samples26,27. All anorthositic clasts are magnesian anorthosites (MANs) filling in the gap between FANs and HMS defined by the Apollo samples (Fig. 1a). Experimental studies and numerical simulations on the LMO solidification suggest that mafic minerals crystallized from the trapped liquid in plagioclase cumulates are ferrous rich with Mg# < 75 (see ref. 17). The high and variable Mg# of mafic minerals in MANs suggests that they have crystallized from compositionally distinct melts ranging from primitive to evolved ones17. Despite rarity in the Apollo-returned samples, MANs are common in lunar meteorites15,16,17 and in Luna 20- and 24-returned samples outside the continuous ejecta of Imbrium28,29. Thus, MANs may comprise an important component of the lunar crust12,13,17, but their petrogenesis remains debated, with models ranging from serial magmatism that does not necessarily invoke LMO17 to reworked products from melts that are closely related to the mantle overturn event16.

Second, the magnesian crustal lithologies (including MANs and HMS) are KREEP (an acronym for the incompatibles K, rare-earth elements (REE), and P)-poor. Plagioclases in the Apollo magnesian crustal lithologies (dominated by HMS) are KREEP-rich30,31, indicative of substantial contributions from a KREEP component ( > 15%)5 linked to the Procellarum KREEP Terrain (PKT). By contrast, plagioclases in the CE-5 magnesian crustal lithologies show REE concentrations that are an order of magnitude lower than the range defined by the Apollo samples (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Trace-element analyses of high-Ca pyroxenes also indicate a KREEP-poor signature (Supplementary Fig. 3). Magnesian crustal lithologies in lunar meteorite collections are almost exclusively KREEP-poor14,15,16,32, which has been cited as evidence for the presence of KREEP-poor early magmatism outside the PKT, and likely globally on the Moon8,32.

Overall, non-Apollo-like highland materials found in the CE-5 samples further confirm the diversity of lunar crustal components and thus the complexity of lunar crust formation, as we will discuss below.

Melt enclosed in plagioclase of a noritic anorthosite

Two high-alumina melts are identified in the plagioclase from a noritic anorthosite clast (Fig. 2a, b), and are confirmed by the Raman spectroscopy which show broad peak positions in 400–600 cm−1 and 800–1200 cm−1 spectral ranges (Fig. 2c). The larger one, approximately 15 μm, is compositionally homogeneous (Supplementary Fig. 4), and is characterized by high Al2O3 content of 20.59 wt.%, Mg# of 74.4, REE concentrations of approximately 150 times of the chondritic value, and negative Eu anomaly (Eu/Eu* = 0.22; Fig. 2d). The other one, <10 μm, has a similar major-element composition (Mg# of 75.6, and Al2O3 content of 21.98 wt.%), but is too small to obtain the trace-element compositions. The melt does not equilibrate with the host plagioclase in terms of REEs, nor does it equilibrate with any mafic minerals in terms of Mg# (equilibrated Mg# of mafic minerals around 91.7). The high REE and Mg# of the melt compared to any mineral within the clast render in-situ impact remelting of the host minerals unlikely. In addition, the melt has low abundances of siderophile elements (Ni, Co, V etc.), substantially lower than those of lunar impact melts which are thought to be contaminated by meteoritic materials through impacting33 (Fig. 2e). Therefore, the high-alumina melt may represent pristine quenched melt that has been captured and trapped in the anorthosite cumulates.

a Backscattered electron image, and b Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping of the melt-bearing noritic anorthosite (outlined by yellow contour). The two enclosed melts are highlighted in red contours. The chemical composition ranges of minerals in the matrix (Mg# for mafic minerals, Wo for pyroxene, An for plagioclase) are also shown for comparison. c Raman spectra of minerals and the enclosed melts from highland clasts in the CE5C0800YJYX132GP. d CI-normalized REE patterns of the enclosed melt, clinopyroxene, plagioclase and orthopyroxene in the noritic anorthosite. e Ni contents (ppm) versus Ni/Co of the enclosed melt compared to the Apollo impact melts from Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 (Apollo IM), and the Apollo mare basalts. Ol: olivine, LCP: low-Ca pyroxene, HCP: high-Ca pyroxene. Trace-element data are reported in Supplementary Data 2. Data sources of the Apollo impact melts are given in Supplementary Data 4 together with a complete reference list; data of mare basalts are from the database at https://www3.nd.edu/~cneal/Lunar-L/.

The melt cannot be the instantaneous residual liquid of the LMO trapped within the anorthosite cumulates. Thermodynamic simulations and experimental studies show that when plagioclase started to crystallize from the LMO, the residual liquids became depleted in Al2O3 (Al2O3 < 15 wt.%) and enriched in FeO (FeO > 10 wt.%) at a given MgO (corresponding to Mg#< 60)34,35,36,37,38, inconsistent with the high Al2O3 and Mg# nature of the melt. In addition, the melt is too enriched in REE to be the anorthosite-equilibrated residual liquid in the LMO model36.

Interestingly, the melt has a major-element composition very similar to those experimentally determined parent melts for HMS39. Crystal fractionation simulation applied to the melt successfully reproduces the HMS trend, with the crystallization sequence of troctolite, norite and gabbronorite (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, see Methods). Moreover, the olivine crystallized from the melt has low Ni and Co contents that are consistent with the olivine Ni-Co patterns observed in lunar troctolites7 (Supplementary Fig. 5c), further suggesting its genetic relationship with HMS.

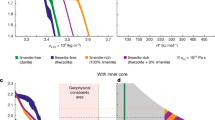

To develop a petrogenetic model for the high-alumina melt, we conducted phase equilibria modeling using the THERMOCALC program40 (see Methods). As shown in Fig. 3a, the calculated liquidi are saturated with plagioclase at low pressures and orthopyroxene (low-Ca pyroxene) at high pressures. The melt is multiply saturated with orthopyroxene and plagioclase at 4.5 kbar ( ~ 85 km) and 1225 °C, which is referred to as the multiple saturation point (MSP)41,42. The presence of clinopyroxene near the MSP reflects the involvement of small amounts of high-Ca pyroxene in the source region (Fig. 3a). The calculated MSP represents the P–T condition of high-alumina melt’s segregation from a plagioclase-bearing, orthopyroxene-dominated lunar upper mantle residue. Compared to the olivine + plagioclase melting experiments conducted at low pressure (1 atm)39, the studied melt is equilibrated at an elevated pressure ( ~ 4.5 kbar) which helps to stabilize orthopyroxene rather than olivine as the equilibrated phase of the melt43.

a Phase equilibria calculation of the enclosed melt using THERMOCALC program. The enclosed melt is multi-saturated with orthopyroxene and plagioclase at 1225 °C and 4.5 kbar. b Mg# versus Al2O3 (wt.%) of the enclosed melt (triangle) and the experiment MGSM21 from ref. 39 (star) compared with melting modeling results of hybridized mantle sources. The initial compositions of these sources are obtained by assuming different proportions of orthopyroxene, plagioclase and the enclosed melt at equilibrium, and expressed as Opxvol%Plvol%Meltvol%. The circles stand for melting degree. Data of the enclosed melts are reported in Supplementary Data 1. Modeling details are provided in the Methods. Opx: orthopyroxene,Cpx: clinopyroxene, Pl: plagioclase.

An orthopyroxene-dominated lunar upper mantle is supported by spectral and geophysical data, and is also predicted by the LMO differentiation model44. Spectral analyses on the South Pole-Aitken Basin and other lunar impact basins suggest that low-Ca pyroxene, rather than olivine, was the dominant spectral component of the upper mantle45,46,47,48,49,50. Geophysical detections are also consistent with an orthopyroxene-dominated lunar upper mantle51. Despite variability in different LMO models, laboratory experiments and numerical simulations on the LMO crystallization sequences predicted that the lunar mantle was characterized by an olivine ± orthopyroxene lower mantle transitioning into an orthopyroxene-dominated upper mantle before plagioclase started to crystallize35,36,37,52. The shallow upper mantle mineralogy following the LMO differentiation would be low-Ca pyroxene + high-Ca pyroxene + plagioclase ± oxide cumulates35,36,37,52. If the plagioclase flotation was inefficient as proposed previously 36, some plagioclases would remain trapped and stable in the lunar upper mantle condition ( ~ 100 km)35,52. The existence of the melting equilibrium pigeonite + plagioclase = liquid + augite at 6 kbar by experimental petrology 53 suggests that melting of an upper mantle assemblage of pigeonite + plagioclase + augite during mantle overturn is feasible. The resulting melt would be capable of crystallizing olivine + plagioclase and then low-Ca pyroxene under crustal pressures, a mineral assemblage akin to HMS. Therefore, we propose that this plagioclase-bearing, orthopyroxene-dominated lunar upper mantle portion could eventually serve as an important source for HMS.

One issue on forming the HMS parent melt by lunar upper mantle melting is the high Mg# of the melt. Several LMO crystallization models suggested that the crystallized phases at ~50–70 PCS are dominated by orthopyroxene ( > 90 vol.%) with high Mg# ( ~ 88–92)35,36,37,52, which could serve as the source composition of the enclosed melt (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Therefore, one likely scenario is upwelling of deep upper mantle pyroxene cumulates due to mantle overturn, mixing with the plagioclase stable at the shallower upper mantle condition, and subsequently melting to produce the high-alumina melt that was parental to HMS. This is in accord with a theoretical prediction of the arising pyroxene-bearing mid-mantle cumulates as the potential source of HMS52.

We performed partial melting model by varying proportions of ascending orthopyroxene in the orthopyroxene-plagioclase hybridized source to account for possible local enrichment of residual plagioclase (see Methods). The major-element composition of the melt is consistent with its formation by partial melting of the low-Ca pyroxene + plagioclase + minor high-Ca pyroxene at upper mantle depths (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6b,e). To be coherent with the REE concentrations of the melt, incorporation of a minor urKREEP component54 (2–4% assuming melting degree is 10%) in this mantle source is required (Supplementary Fig. 6f), which is geodynamically feasible in the context of mantle overturn. The addition of plagioclase and urKREEP to the ascending orthopyroxene-dominated cumulates can remarkably reduce the melting temperature ( < 1225 °C at 4.5 kbar; Supplementary Fig. 7a). This finding aligns with recent numerical models estimating the LMO crystallization temperature of ~1200–1250 °C at ~85 km depth23,55,56, supporting the feasibility of remelting the hybridized source without requiring additional heat sources. Partial melting of this hybridized source can produce a substantial number of liquid compositions resembling the enclosed melt observed in our samples (Supplementary Fig. 7b). The involvement of a small amount of urKREEP component not only lowered the melting temperature39, but also increased the Na and K in the melt. Thus, crystal fractionation of this melt would evolve along the trend with decreasing Mg# and An5,8.

Upper mantle melting on building lunar early crust

Gravitational instabilities in magma ocean cumulate piles may be the main driving force for the onset of mantle convection and formation of a hybridized source for HMS magmas23,52. The coexistence between noritic anorthosite and high-alumina melts found in the CE-5 samples provides direct evidence that the sinking of dense ilmenite-bearing cumulates (IBC) is parallel to the formation of the anorthositic lunar crust. The timescale, spatial scales and efficiency of the IBC downwelling remain not fully constrained44. Several studies argued that downwelling of IBC with reasonable viscosities would occur over millions to 10 s of Myr20,55, while the solidification of the LMO lasted over 10 s to 100 s of Myr20,52,56,57,58,59, implying the onset of mantle overturn before complete LMO solidification. Traditional view suggests that the overturn of IBC triggered the decompression melting of deep-seated, lower mantle dominated by olivine ± orthopyroxene ( < 50 PCS), forming the mantle end member of the HMS source region6,7,8,9,10,11. Our new findings in the CE-5 samples suggest that the shallow-seated, upper mantle cumulates (50–70 PCS) may have also served as the mantle end member for HMS petrogenesis. Upwelling of these orthopyroxene-dominated cumulates and mixing with the plagioclase either residual in the shallow upper mantle or at the crustal-mantle boundary would form a hybridized source for HMS magmas. Accordingly, we suspect that prior to the global mantle overturn, small-scale mantle reconstructing (in-situ overturn) at the onset of gravitational instability induced decompression melting of the lunar upper mantle lithologies (orthopyroxene + plagioclase ± clinopyroxene). Late accumulation of IBC packages into a thickened layer may have eventually set the stage for subsequent large-scale overturn event. The in-situ overturn event may have played an important role in generating the earliest basaltic magmatism of the Moon and contributed to early crust building. The participation of urKREEP would have increased radiogenic heat production and simultaneously lowered the melting temperature, further facilitating upper mantle melting39. Besides mantle overturn, the strong core-mantle friction at the early phase of lunar evolution is also suggested to have sustained global-scale partial melting of lunar mantle cumulates60,61,62.

Thus, early lunar crust building may be a continuous process (Fig. 4). The cumulate mantle overturn occurred near contemporaneously with primary lunar crust solidification18,19,20 (Fig. 4a). It started with small-scale sink of IBC diapirs into the underlying mantle, causing in-situ overturn. The upper mantle lithologies ascending during this process formed a hybridized source for HMS magmas. These upper mantle-derived melts intruded into and were captured by the ascending anorthositic cumulates, as is well-preserved in our CE-5 samples (Fig. 4b). Continuous down-going IBC patches mixed with underlying cumulates to form a thickened layer and eventually caused a large-scale, and possibly global mantle overturn, bringing the deep-seated, olivine ± orthopyroxene cumulates to arise and melt, further producing melts parental to HMS (Fig. 4c). This scenario is supported by the overlap in radiometric age determined for lunar anorthosites and HMS21,22. Overall, the lunar upper mantle melting induced by in-situ overturn may have played an important role in linking the lunar primitive crust building and secondary crust reworking.

a Crystallization sequence of the lunar magma ocean and the production of primitive anorthositic crust. Black: LMO residual liquid; pink: olivine; orange: low-Ca pyroxene; green: high-Ca pyroxene; gray: plagioclase/anorthositic crust. b At the onset of gravitational instabilities in magma ocean cumulate piles, small-scale sinking of IBC diapirs (yellow) into the underlying mantle led to the overturn of the orthopyroxene-dominated upper mantle (50–70 PCS). The orthopyroxene cumulates arose and mixed with plagioclase and melted during small-scale in-situ overturn, producing parent magmas of HMS. The melt was then trapped and captured by the rising anorthositic diapirs. c With ongoing gravitational restructuring, global scale mantle overturn caused the olivine-dominated lower mantle cumulates to rise and melt at shallow depths, further producing parent melt of HMS.

Methods

Scanning electron microscopy analysis and energy dispersive spectroscopy mapping

The fine backscattered electron (BSE) images of carbon-coated sections and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping analyses were performed using a Zeiss Gemini 450 field-emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an X-ray energy dispersive spectrometer and a backscattered electron (BSE) system with a six-segment multimode solid-state BSE detector. All experiments were performed at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS). The EDS mappings were performed using an acceleration voltage of 20 kV, a beam current of 5 nA, and a working distance of 8.5 mm. We selected a resolution of 4096×3072 pixels and dwell time of 8000 μs.

Electron microprobe analysis

The major-element compositions of plagioclase, pyroxene, olivine and the enclosed melts were determined using EPMA1720 electron microprobe at the EPMA Lab, China University of Geosciences, Beijing (CUGB), and JEOL JXA8100 electron probe at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS), respectively. The samples were analyzed at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV, a beam current of 10 nA, and a focused beam width of 1–2 μm at CUGB, and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, a probe current of 20 nA, and a focused beam width of 1–2 μm at IGGCAS. The peak counting time was 10–30 s for each element and the background time was 10 s. Natural minerals and synthetic materials were used as standards as follows: rhodonite (Si and Mn), apatite (Ca), rutile (Ti), FeS2 (Fe), albite (Na), sanidine (K), and MgO (Mg). All data were corrected for atomic number (Z), X-ray absorption (A), and fluorescence (F) effects. The detection limits for most elements were 0.01–0.06 wt.%. Data are reported in Supplementary Data 1.

X-ray intensity maps of characteristic elements (Ca, Fe, Al, Mg) in the enclosed melt were generated using electron microprobe at the EPMA Lab, China University of Geosciences, Beijing (CUGB). Each analytical point in the maps was acquired using a focused electron beam with a diameter of < 2 μm, an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, and an electric current of 10 nA. We selected a resolution of 600 × 520 pixels and dwell time of 120 ms.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman analyses were performed by a Witec alpha300R confocal Raman microscope and a Raman Imaging and Scanning Electron Microscopy system (RISE system consists of a Zeiss Gemini 450 SEM and a Witec alpha300R Raman) at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS). Sample for Raman measurement was not coated with carbon. The spectra were excited with 532 nm radiation from a semi-conductor laser. The laser power was 7 mW. A 600 grooves/mm grating was used. The Raman shift regions ranging from 100 to 1200 cm−1 were used for this study. The data were calibrated with a silicon peak of 520.7 cm−1. For silicate minerals, a spectral acquisition time of 5 s and total spectra with 3 accumulations were collected for each measurement. For the enclosed melts, a spectral acquisition time of 15 s and total spectra with 27 accumulations were collected for each measurement. The spectra were not baseline corrected.

In-situ trace-element analysis

Trace-element abundances were determined using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) employing an Element XR HR-ICP-MS instrument coupled to a GeolasHD 193 nm ArF excimer LA system at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS). Helium was used as the ablation gas to improve the transport efficiency of the ablated aerosols. All measurements were conducted at 3 Hz frequency. The laser energy density was approximately 3.0 J cm−2. For silicate minerals and the enclosed melt, the analyses were conducted using different laser diameters depending on the target grain size (24, 32 and 44 μm for the plagioclases; 10 and 16 μm for the pyroxenes; 10 μm for the enclosed melt). ARM-163 reference glass was used for external calibration (Si was used as a standard for data reduction). BCR-2G and NIST SRM 610 glasses were used for quality control monitoring. The data obtained during ablation runs were processed using the Iolite 3.4 software with an in-house-built data reduction scheme mode64 with the bulk normalization as 100 wt.% strategy. Data are reported in Supplementary Data 2. The analyses of reference materials BCR-2G and NIST SRM 610 using different laser spot sizes are given in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig. 8, agreeing with published data65. Their quoted uncertainties are defined as two times the standard error (2SE).

Crystal fractionation modeling

PETROLOG program66 was applied to perform crystal fractionation simulation on the enclosed melt in plagioclase of a noritic anorthosite. Our modeling was set as pure (100%) crystal fractionation at a constant pressure (1 bar). The calculation step is set as 1%. Mineral-melt equilibrium models used here are as follows: olivine67, plagioclase68, orthopyroxene69, clinopyroxene70 and pigeonite68. The fO2 was set as the iron-wüstite (IW). The crystal fractionation modeling ceased when MgO <0 wt.%. The crystallization trend of the enclosed melt in terms of Mg# of mafic minerals versus An of plagioclase is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a; the crystallized mineral assemblages are consistent with petrological characteristics of the Mg-suite rocks (troctolite, norite and gabbronorite) and shown in Supplementary Fig. 5b. The Ni/Co content (COl) of the olivine crystallized from the enclosed melt was obtained by the following equation:

where Cmelt represents Ni/Co content of the enclosed melt. The partitioning coefficients, DOl-melt of Ni and Co are from ref. 71. Calculated Ni/Co content of the olivine crystallized from the enclosed melt is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5c.

Phase equilibria modeling

To calculate source components of the enclosed melt, phase equilibria modeling was carried out using the THERMOCLAC version 3.50 program40 and the internally consistent thermodynamic dataset ds63472 (updated 19 December 2019) to infer the source materials and depths of the enclosed melt. The modeling was run in a nine-component K2O–Na2O–CaO–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–TiO2–Cr2O3 system. Activity–composition solution models are olivine, plagioclase, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene, and silicate melt40 with a reduced Darken’s Quadratic Formalism value for the sillimanite end member in the silicate melt of 0 kJ mol−1 from 7.86 kJ mol−1, due to the overestimation of Al2O3 in pyroxene on the liquidus. The enclosed melt produces plagioclase as the liquidus phase at low pressures and orthopyroxene at high pressures. The intersection of plagioclase and orthopyroxene liquidi defines the multiple saturation point42,73. The multiple saturation point is supposed to represent the P–T condition of melt segregation from its source region, and the co-saturated phases (e.g., orthopyroxene and plagioclase here) are referred to as the liquidus assemblage from which the melt was segregate41. This modeling method has been proven to successfully reproduce experimental results of multiple saturation points for lunar volcanic glasses74, supporting the validity of our work. The equilibrated compositions of the orthopyroxene and plagioclase are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Partial melting modeling

To test whether the enclosed melt can be generated by melting of the lunar upper mantle lithologies, we conducted partial melting modeling on the major and rare-earth elements of the enclosed melt.

To simulate major-element characteristics of the enclosed melt, we first obtained the major-element compositions of the mantle sources by assuming various proportions of the orthopyroxene, plagioclase in the mantle residue and the enclosed melt at equilibrium (orthopyroxene: plagioclase: the enclosed melt = 88.2: 1.8: 10; 81: 9: 10; 63: 27: 10; 63: 7: 30 and 45: 5: 50; both orthopyroxene and plagioclase are equilibrated with the enclosed melt). The bulk compositions of the mantle sources were calculated by summing those three components using the THERMOCALC program (Supplementary Table 1). Then, we used the THERMOCALC program to calculate major-element evolutions of the mantle melts. The results correspond well with the major-element composition of the enclosed melt (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6b–e). The Mg# of the mantle source should be nearly identical to Mg# of the orthopyroxene if the mantle is orthopyroxene-dominated. Our calculations are in accord with orthopyroxene crystallized from the LMO at ~50–70 PCS (Mg#~88–9235,36,37,52) (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Orthopyroxenes crystallized from the LMO at > 70 PCS generally have Mg#< 8535,36,37 and could only generate the enclosed melt when melting degree exceeds 50 vol% (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

To simulate the REE concentrations of the enclosed melt, we used non-modal batch melting model. To simplify the calculation, the melting proportion Pm for minerals involved in the melting was assumed to be the CIPW norm of the enclosed melt (clinopyroxene: orthopyroxene: plagioclase = 0.04: 0.62: 0.34). The mantle melting degree F was set as 10% for example. The ratio of orthopyroxene to plagioclase in the mantle residue when equilibrated with the melt was set as 98: 2, 90: 10 and 70: 30, respectively. For mineral m in the hybridized mantle (clinopyroxene + orthopyroxene + plagioclase), the initial mineral abundance Xmi was recalculated based on the mineral abundance XmE when equilibrated with the enclosed melt, melting degree F and melting proportion Pm, using the equation:

To obtain REE compositions of the hybridized mantle, we first calculated residual liquid compositions during the fractional crystallization of the LMO. The initial REE compositions of the LMO were cited from ref. 36; the crystallization sequence of LMO with bulk Moon composition of LPUM from ref. 35 was used. The concentration of element i in the residual liquid \({C}_{{{{\rm{l}}}}}^{{\mbox{i}}}\) was modeled by the following equation:

where \({C}_{0}^{{\mbox{i}}}\) is the concentration of element i in the LMO; \(f\) is the remaining fraction of the residual liquid; Di bulk is the bulk partitioning coefficient of the LMO cumulates, obtained by:

where \({D}_{{{{\rm{mineral}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}}\) is the partitioning coefficient, \({X}_{{{{\rm{mineral}}}}}^{{{{\rm{LMO}}}}}\) is the mineral abundance in the LMO cumulates for each mineral.

Thus, REE of minerals in the LMO cumulates could be obtained using

REE concentrations of plagioclase and clinopyroxene were assumed to be equilibrated with the LMO liquid at 85 PCS (where plagioclase is a major phase in the LMO cumulates)35, while composition of orthopyroxene was equilibrated with the LMO liquid at 65 PCS (see discussion above)35. Therefore, bulk composition and coefficient of the hybridized mantle source C0 and D0 were then given by

The REE contents of the melt by batch melting were then modeled using the following equation:

where \(P\) was defined as:

Because of the low REE contents of the LMO liquid at <90 PCS36, melting of the hybridized mantle with various trapped LMO liquid contents (1–10%) cannot produce trace elemental characteristics of the enclosed melt. Thus, a KREEP-rich component must have been added into the source in various proportions. Melting results suggest that adding ~2–4% urKREEP component54 can reasonably produce the REE pattern of the enclosed melt at 10% melting degree (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Note that the involvement of an urKREEP component in the melting simulation will not substantially change the major-elemental modeling results. The partitioning coefficients of olivine, clinopyroxene, plagioclase, orthopyroxene, pigeonite are given in Supplementary Table 2.

Data availability

All data analyzed or generated in this study are available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25801228.

Code availability

The software and data files used for phase equilibria modeling are available at https://hpxeosandthermocalc.org/. The software used for crystallization modeling is available at http://petrolog.web.ru.

References

Warner, J., Simonds, C. & Phinney, W. Genetic distinction between anorthosites and Mg-rich plutonic rocks: new data from 76255. Abstr. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 7, 915 (1976).

Smith, J., Anderson, A., Newton, R., Olsen, E. & Wyllie, P. A petrologic model for the Moon based on petrogenesis, experimental petrology, and physical properties. J. Geol. 78, 381–405 (1970).

Warren, P. H. Lunar anorthosites and the magma-ocean plagioclase-flotation hypothesis; importance of FeO enrichment in the parent magma. Am. Mineralogist 75, 46–58 (1990).

Wood, J. A., Dickey, J. S. Jr, Marvin, U. B. & Powell, B. N. Lunar anorthosites. Science 167, 602–604 (1970).

Elardo, S. M. & Astudillo Manosalva, D. F. Complexity and ambiguity in the relationships between major lunar crustal lithologies and meteoritic clasts inferred from major and trace element modeling. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 354, 13–26 (2023).

Elardo, S. M., Draper, D. S. & Shearer, C. K. Lunar Magma Ocean crystallization revisited: Bulk composition, early cumulate mineralogy, and the source regions of the highlands Mg-suite. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 75, 3024–3045 (2011).

Shearer, C. K. & Papike, J. Early crustal building processes on the moon: models for the petrogenesis of the magnesian suite. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 69, 3445–3461 (2005).

Prissel, T. C. & Gross, J. On the petrogenesis of lunar troctolites: new insights into cumulate mantle overturn & mantle exposures in impact basins. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 551, 116531 (2020).

Shearer, C. & Papike, J. Magmatic evolution of the Moon. Am. Mineralogist 84, 1469–1494 (1999).

Hess, P. C. Petrogenesis of lunar troctolites. J. Geophysic. Res.: Planets 99, 19083–19093 (1994).

Longhi, J., Durand, S. R. & Walker, D. The pattern of Ni and Co abundances in lunar olivines. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 74, 784–798 (2010).

Arai, T., Takeda, H., Yamaguchi, A. & Ohtake, M. A new model of lunar crust: asymmetry in crustal composition and evolution. Earth, Planets Space 60, 433–444 (2008).

Ohtake, M. et al. Asymmetric crustal growth on the Moon indicated by primitive farside highland materials. Nat. Geosci. 5, 384–388 (2012).

Korotev, R. L., Jolliff, B. L., Zeigler, R. A., Gillis, J. J. & Haskin, L. A. Feldspathic lunar meteorites and their implications for compositional remote sensing of the lunar surface and the composition of the lunar crust. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 67, 4895–4923 (2003).

Takeda, H. et al. Magnesian anorthosites and a deep crustal rock from the farside crust of the moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 247, 171–184 (2006).

Xu, X. et al. Formation of lunar highlands anorthosites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 536, 116138 (2020).

Gross, J., Treiman, A. H. & Mercer, C. N. Lunar feldspathic meteorites: Constraints on the geology of the lunar highlands, and the origin of the lunar crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 388, 318–328 (2014).

Hess, P. C. & Parmentier, E. A model for the thermal and chemical evolution of the Moon’s interior: Implications for the onset of mare volcanism. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 134, 501–514 (1995).

Boukaré, C.-E., Parmentier, E. & Parman, S. Timing of mantle overturn during magma ocean solidification. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 491, 216–225 (2018).

Zhao, Y., De Vries, J., van den Berg, A., Jacobs, M. & van Westrenen, W. The participation of ilmenite-bearing cumulates in lunar mantle overturn. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 511, 1–11 (2019).

Borg, L. E., Gaffney, A. M. & Shearer, C. K. A review of lunar chronology revealing a preponderance of 4.34–4.37 Ga ages. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 715–732 (2015).

Borg, L. E. & Carlson, R. W. The evolving chronology of moon formation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 51, 25–52 (2023).

Prissel, T. C., Zhang, N., Jackson, C. R. & Li, H. Rapid transition from primary to secondary crust building on the Moon explained by mantle overturn. Nature. Communications 14, 5002 (2023).

Longhi, J. & Ashwal, L. D. Two‐stage models for lunar and terrestrial anorthosites: Petrogenesis without a magma ocean. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 90, C571–C584 (1985).

Li, C. et al. Characteristics of the lunar samples returned by the Chang’E-5 mission. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab188 (2022).

Sheng, S.-Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, B., Hao, J.-H. & Wang, S.-J. First Location and Characterization of Lunar Highland Clasts in Chang’E 5 Breccias Using TIMA-SEM-EPMA. At. Spectrosc. 43, 352–363 (2022).

Zeng, X., Li, X. & Liu, J. Exotic clasts in Chang’e-5 regolith indicative of unexplored terrane on the Moon. Nature Astronomy, 1-8 (2022).

Shearer, C. K., Moriarty, D. P., Simon, S. B., Petro, N. & Papike, J. J. Where Is the Lunar Mantle and Deep Crust at Crisium? A Perspective From the Luna 20 Samples. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 128, e2022JE007409 (2023).

Bence, A. & Grove, T. L. The Luna 24 highland component. Mare Crisium: View Luna 24, 429–444 (1978).

Papike, J. J., Fowler, G. W., Shearer, C. K. & Layne, G. D. Ion microprobe investigation of plagioclase and orthopyroxene from lunar Mg-suite norites: Implications for calculating parental melt REE concentrations and for assessing postcrystallization REE redistribution. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 60, 3967–3978 (1996).

Shervais, J. W. & McGee, J. J. Ion and electron microprobe study of troctolites, norite, and anorthosites from Apollo 14: evidence for urKREEP assimilation during petrogenesis of Apollo 14 Mg-suite rocks. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 62, 3009–3023 (1998).

Gross, J. et al. Geochemistry and Petrogenesis of Northwest Africa 10401: A New Type of the Mg-Suite Rocks. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 125, e2019JE006225 (2020).

Palme, H. The meteoritic contamination of terrestrial and lunar impact melts and the problem of indigenous siderophiles in the lunar highland. : Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf., 11th 11, 481–506 (1980).

Lin, Y., Tronche, E. J., Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Experimental constraints on the solidification of a nominally dry lunar magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 471, 104–116 (2017).

Charlier, B., Grove, T. L., Namur, O. & Holtz, F. Crystallization of the lunar magma ocean and the primordial mantle-crust differentiation of the Moon. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 234, 50–69 (2018).

Snyder, G. A., Taylor, L. A. & Neal, C. R. A chemical model for generating the sources of mare basalts: Combined equilibrium and fractional crystallization of the lunar magmasphere. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 56, 3809–3823 (1992).

Rapp, J. & Draper, D. Fractional crystallization of the lunar magma ocean: Updating the dominant paradigm. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 1432–1455 (2018).

Johnson, T. E., Morrissey, L. J., Nemchin, A. A., Gardiner, N. J. & Snape, J. F. The phases of the Moon: Modelling crystallisation of the lunar magma ocean through equilibrium thermodynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 556, 116721 (2021).

Elardo, S. M., Laneuville, M., McCubbin, F. M. & Shearer, C. K. Early crust building enhanced on the Moon’s nearside by mantle melting-point depression. Nat. Geosci. 13, 339–343 (2020).

Tomlinson, E. L. & Holland, T. J. A thermodynamic model for the subsolidus evolution and melting of peridotite. J. Petrol. 62, egab012 (2021).

Asimow, P. D. & Longhi, J. The significance of multiple saturation points in the context of polybaric near-fractional melting. J. Petrol. 45, 2349–2367 (2004).

Elkins, L., Fernandes, V., Delano, J. & Grove, T. Origin of lunar ultramafic green glasses: Constraints from phase equilibrium studies. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 64, 2339–2350 (2000).

Longhi, J. Pyroxene stability and the composition of the lunar magma ocean. : Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf., 9th 9, 285–306 (1978).

Moriarty, D. P. III, Dygert, N., Valencia, S. N., Watkins, R. N. & Petro, N. E. The search for lunar mantle rocks exposed on the surface of the Moon. Nature. Communications 12, 4659 (2021).

Melosh, H. et al. South Pole–Aitken basin ejecta reveal the Moon’s upper mantle. Geology 45, 1063–1066 (2017).

Bretzfelder, J. M. et al. Identification of potential mantle rocks around the lunar Imbrium basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090334 (2020).

Moriarty, D., Pieters, C. & Isaacson, P. Compositional heterogeneity of central peaks within the South Pole‐Aitken Basin. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 118, 2310–2322 (2013).

Moriarty, D. III & Pieters, C. The character of South Pole‐Aitken Basin: Patterns of surface and subsurface composition. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 123, 729–747 (2018).

Nakamura, R. et al. Ultramafic impact melt sheet beneath the South Pole–Aitken basin on the Moon. Geophysical Research Letters 36 (2009).

Ohtake, M. et al. Geologic structure generated by large‐impact basin formation observed at the South Pole‐Aitken basin on the Moon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2738–2745 (2014).

Kuskov, O. L., Kronrod, E. V. & Kronrod, V. A. Thermo-chemical constraints on the lunar bulk composition and the structure of a three-layer mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 286, 1–12 (2019).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Burgess, S. & Yin, Q.-Z. The lunar magma ocean: Reconciling the solidification process with lunar petrology and geochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 304, 326–336 (2011).

Longhi, J. A new view of lunar ferroan anorthosites: Postmagma ocean petrogenesis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 108 (2003).

Neal, C. & Taylor, L. Definition of Pristing, Unadulterated urKREEP Composition Using the” K-FRAC/REEP-FRAC” Hypothesis. Abstr. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 20, 772 (1989).

Yu, S. et al. Overturn of ilmenite‐bearing cumulates in a rheologically weak lunar mantle. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 124, 418–436 (2019).

Maurice, M., Tosi, N., Schwinger, S., Breuer, D. & Kleine, T. A long-lived magma ocean on a young Moon. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba8949 (2020).

Borg, L. E., Connelly, J. N., Boyet, M. & Carlson, R. W. Chronological evidence that the Moon is either young or did not have a global magma ocean. Nature 477, 70–72 (2011).

Thiemens, M. M., Sprung, P., Fonseca, R. O., Leitzke, F. P. & Münker, C. Early Moon formation inferred from hafnium–tungsten systematics. Nat. Geosci. 12, 696–700 (2019).

Borg, L. E. et al. Isotopic evidence for a young lunar magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 523, 115706 (2019).

Yu, S. et al. Long-lived lunar volcanism sustained by precession-driven core-mantle friction. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwad276 (2024).

Williams, J. G., Boggs, D. H., Yoder, C. F., Ratcliff, J. T. & Dickey, J. O. Lunar rotational dissipation in solid body and molten core. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 106, 27933–27968 (2001).

Dwyer, C., Stevenson, D. & Nimmo, F. A long-lived lunar dynamo driven by continuous mechanical stirring. Nature 479, 212–214 (2011).

Wu, S. et al. The preparation and preliminary characterisation of three synthetic andesite reference glass materials (ARM‐1, ARM‐2, ARM‐3) for in situ microanalysis. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 43, 567–584 (2019).

Shi-Tou, W., Huang, C., Lie-Wen, X., Yue-Heng, Y. & Jin-Hui, Y. Iolite based bulk normalization as 100%(m/m) quantification strategy for reduction of laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry transient signal. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 46, 1628–1636 (2018).

Gao, S. et al. Determination of forty two major and trace elements in USGS and NIST SRM glasses by laser ablation‐inductively coupled plasma‐mass spectrometry. Geostand. Newsl. 26, 181–196 (2002).

Danyushevsky, L. V. & Plechov, P. Petrolog3: Integrated software for modeling crystallization processes. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 12 (2011).

Ford, C., Russell, D., Craven, J. & Fisk, M. Olivine-liquid equilibria: temperature, pressure and composition dependence of the crystal/liquid cation partition coefficients for Mg, Fe2+, Ca and Mn. J. Petrol. 24, 256–266 (1983).

Ariskin, A. A., Frenkel, M. Y., Barmina, G. S. & Nielsen, R. L. COMAGMAT: a Fortran program to model magma differentiation processes. Comput. Geosci. 19, 1155–1170 (1993).

Beattie, P. Olivine-melt and orthopyroxene-melt equilibria. Contri. Mineral. Petrol. 115, 103–111 (1993).

Danyushevsky, L. V. The effect of small amounts of H2O on crystallisation of mid-ocean ridge and backarc basin magmas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 110, 265–280 (2001).

Le Roux, V., Dasgupta, R. & Lee, C.-T. Mineralogical heterogeneities in the Earth’s mantle: Constraints from Mn, Co, Ni and Zn partitioning during partial melting. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 395–408 (2011).

Holland, T. & Powell, R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. J. Metamorphic Geol. 29, 333–383 (2011).

Grove, T. L. & Krawczynski, M. J. Lunar mare volcanism: where did the magmas come from? Elements 5, 29–34 (2009).

Su, B. et al. Fusible mantle cumulates trigger young mare volcanism on the Cooling Moon. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2103 (2022).

Lindstrom, M., Marvin, U. & Mittlefehldt, D. Apollo 15 Mg-and Fe-norites-A redefinition of the Mg-suite differentiation trend. : Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf., 19th 19, 245–254 (1989).

Floss, C., James, O. B., McGee, J. J. & Crozaz, G. Lunar ferroan anorthosite petrogenesis: Clues from trace element distributions in FAN subgroups. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 62, 1255–1283 (1998).

Papike, J., Fowler, G. & Shearer, C. Evolution of the lunar crust: SIMS study of plagioclase from ferroan anorthosites. Geochimica et. Cosmochimica Acta 61, 2343–2350 (1997).

Cahill, J. T. et al. Petrogenesis of lunar highlands meteorites: Dhofar 025, Dhofar 081, Dar al Gani 262, and Dar al Gani 400. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 39, 503–529 (2004).

Russell, S. S., Joy, K. H., Jeffries, T. E., Consolmagno, G. J. & Kearsley, A. Heterogeneity in lunar anorthosite meteorites: implications for the lunar magma ocean model. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 372, 20130241 (2014).

McDonough, W. F. & Sun, S.-S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 120, 223–253 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank the China National Space Administration for providing access to the Chang’e-5 returned sample CE5C0800YJYX132GP.We are grateful to Jinhua Hao, Di Zhang, Lihui Jia and Xiaoguang Li for their support on EPMA and Raman analysis. This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42241103, 41973010 and 42241107), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant 2652023001). The lunar sample CE5C0800YJYX132GP was provided by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) under a materials transfer agreement. The sample is now returned to CNSA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.W. conceptualized the study. S.Z.S. collected the data. S.Z.S. and B.S. performed geochemistry modeling. B.S. conducted Phase equilibria modeling. S.W. developed the methodology for trace-element analysis of the highland clasts and the enclosed melt. J.Y.Y. developed the methodology for EDS mappings of the highland clasts. Y.C., Q.L.L., H.W., H.H., and B.Z. contributed to the interpretation of the results. S.Z.S., B.S., and S.J.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Shuoran Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Renbiao Tao and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheng, SZ., Su, B., Wang, SJ. et al. Orthopyroxene-dominated upper mantle melting built the early crust of the Moon. Commun Earth Environ 5, 403 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01574-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01574-6

This article is cited by

-

Halogen abundance evidence for the formation and metasomatism of the primary lunar crust

Nature Communications (2025)