Abstract

Extreme solar energetic particle events, known as Miyake events, are rare phenomena observed by cosmogenic isotopes, with only six documented. The timing of the ca. 660 BCE Miyake event remains undefined until now. Here, we assign its occurrence to 664–663 BCE through new radiocarbon measurements in gymnosperm larch tree rings from arctic-alpine biomes (Yamal and Altai). Using a 22-box carbon cycle model and Bayesian statistics, we calculate the radiocarbon production rate during the event that is 3.2–4.8 times higher than the average solar modulation, and comparable to the 774–775 CE solar-proton event. The prolonged radiocarbon signature manifests a 12‰ rise over two years. The non-uniform signal in the tree rings is likely driven by the low rate of CO2 gas exchange between the trees and the ambient atmosphere, and the high residence time of radiocarbon in the post-event stratosphere. We caution about using the event’s pronounced signature for precise single-year-dating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiocarbon data is a powerful tool for assessing the history of solar energetic proton (SEP) events in the Holocene. A characteristic of the usual 14C dependence on solar activity, is that when the sun is more active, its geomagnetic field reduces the galactic cosmic ray flux (GCR) at the rate of ca. 0.004 times the observed sunspot number1. At the same time, solar proton events can increase 14C production. Lingenfelter and Ramaty2 were the first to estimate the role of solar proton events in increasing the 14C production in the atmosphere. They noted that SEP events during solar maxima might be sufficient to counteract the decrease in production of 10–20% during a solar cycle1. Damon et al.3 followed up on these ideas as well, presciently noting that:

“The record of solar-flare-produced 14C in tree rings provides the opportunity to search for unusually intense solar proton fluences during the last nine millennia”

Miyake et al.4,5 were the first to demonstrate the rapid excursions at 774–775 CE and 993–994 CE in 14C tree-ring content, which were consequences of energetic solar proton events or extreme solar radiation storms. Since that time, there have been numerous studies confirming these two events [e.g., 6,7,8,9] as well as identifying additional events at ca. 660 BCE10, 5259 BCE, 7176 BCE11 and 12,450 BCE12. Six of these events are clearly tied to solar cosmic-ray events, as 10Be has been independently measured at these times in ice cores13,14,15, and they have been termed “Miyake Events” (ME). Other smaller events not clearly tied to solar proton events (as they are not confirmed independently by 10Be content in ice cores) have also been reported. These include events at ca. 810 BCE, as well as at 1261–1262, 1268–1269, and 1279–1280 CE16,17,18, which may be connected to the onset of the Wolf minimum19. Small 14C excursions at 1006 CE17 and 1052–1055 CE18,20 may be related to solar or supernova events. All these diverse phenomena are manifest through rapid changes in the 14C signal observed in tree rings.

The precise positioning of a SEP in real time is extremely important for the parameterization of solar activity and forecasts. To calculate the probabilities of extreme SEP events and their distribution functions from cosmogenic isotope data, it is necessary to know how many single events with an energy fluence F (≥30 MeV) ≥ 106 cm−2 occurred outside of the instrumental period21. Notably, one of the recently confirmed SEP events does not have an exact calendar date. Multiple radionuclide evidence of an extreme SEP (or ME) event ca. 2610 BP (before 1950) more commonly referenced as ca. 660 BCE was confirmed with high-resolution 10BE records of three ice cores from Greenland in 201914. The study assessed the very hard energy spectrum and proton fluence of the SEP F (>30 MeV) 2.09 (±0.75) × 1010 cm−2 and F (>200 MeV) 6.3 (±2.28) × 109 cm−2), which is comparable to the large ME event of the 774–775 CE. However, the ca. 660 BCE ME has an unusual structure that is different from the short-term rapid increases in radionuclide production observed at 774–775 CE and 993–994 CE. One proposed explanation is the possible occurrence of consecutive SEPs over up to three years22. The spike ca. 660 BCE was originally discovered by Park et al.10 in the 14C content signature of German oak tree rings. A few years later, Sakurai et al.22 measured 14C in Choukai cedar and estimated 14C production in the atmosphere for two types of solar proton inputs: a single pulse and a double pulsed flux. Their study revealed that a rather ambiguous 14C increase occurred within 665–663.5 BCE over a variable time interval from 1 to 41 months. The magnitude of this ME event recorded by the Choukai cedar and German oak series was prominent but extended over multiple years—14.3 ± 1.5‰ over 4 years and 13.3 ± 2.1‰ over 6 years, respectively.

Other attempts to replicate the spike signal in tree rings from other locations were successful but have not resolved questions about the prolonged structure and the exact date of this event23. Here, we examine two new annual 14C series from coniferous tree rings at high-latitude and high-altitude sites ca. 660 BCE ME to resolve the controversy surrounding the onset and duration of this extreme SEP event. The new locations (Yamal and Altai) were strategically selected as close as possible to the North Pole and tropopause. The laboratory bias in measurements is minimized through meticulous selection of the time series employed in this study. Only continuous 20-year series were used in the modeling from four AMS facilities following strictly certified protocols (see Methods). To maintain consistency, the short series of Vistula oak23 was excluded from the full analysis due to gaps in the measurements from two different AMS facilities. The magnitude of the ca. 660 BCE ME was estimated via a 22-box model of the global carbon cycling applied to the spike signal of four 14C tree-ring proxies, which scales up the change in the atmospheric CO2 concentration driven by the additional solar proton flux8. For robustness of our analysis, we have applied two fitting approaches (see Methods) estimating the production rate of the event with the carbon cycle modeling24.

Results

Variation in atmospheric 14C around the ca. 660 BCE Miyake event

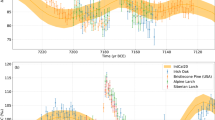

The cosmogenic isotope content of atmospheric CO2 fixed into structural cellulose by tree rings during the growing season is expressed as delta 14C (Δ14C) in annual or subannual tree-ring series. In this study, we analyzed four Δ14C series of gymnosperm larch and cedar trees from three locations in northern Eurasia and one Δ14C series of angiosperm oaks from central Europe (Supplementary Table 1). The measurement error of our data is less than 2‰. The weighted average of the Altai larch and Yamal larch Δ14C series measured at the same AMS facilities was 7.6 ± 1.7‰, and other Δ14C series measured at different laboratories had weighted averages between 6.0 ± 1.6 ‰ and 8.7 ± 1.7‰. Most Δ14C series have annual resolution. For the two series of cedar, subannual earlywood and latewood subdivisions from the same rings were measured, which approximate early-growing or late-growing season 14C content22. Figure 1 presents the radiocarbon signatures of the ca. 660 BCE spike from these tree rings, which are visually attributed to the pulse-like impact of SEP recorded in different parts of high- to mid-latitude Eurasia. The data register ca. 15 ‰ 14C change over 665–660 BCE. The Δ14C records do not show uniform variations, which is not unusual due to the many interacting factors driving the fractionation of atmospheric radiocarbon.

Variations of Δ14C concentrations measured in tree rings at ca. 660 BCE ME (a) and map showing the locations of the tree rings (b). New time series and previously published ones are color-coded. Tree-ring data locations: red-Altai Mountains and orange- Yamal Peninsula from this study; green—Japan from Sakurai et al.22; and blue—Central Europe from Park et al.10 and Rakowski et al.23. Rakowski et al. series23 shown here is excluded from the production rate modeling due to short length and missing values. The vertical line represents the 664 BCE. Although the series show some differences in Δ14C variations ca. 660 BCE ME, the spike signal is apparent as a ca. 15 ‰ increase over 2–3 years, which is sustained by high values for the next 2–3 years followed by a slow return to the average of ca. 5‰. The map was created in QGIS (3.8.0) using Google Earth imagery.

We noticed consistently higher values (ca. 5%) of Δ14C in the Altai larch series in the overlapped interval of 670–636 BCE (Fig. 1). This most likely reflects the high elevation of this site (2300 m asl), with closer proximity to the tropopause and an enhanced photosynthetic rate, which many studies have found in C3 plants at high latitude25,26,27. Within similar species, stable-carbon isotope discrimination is less at high elevations than at low elevations in similar habitats25. A similar offset was observed between the values of annual 14C measurements in low-elevation European oaks and bristlecone pine from Sheep Mountain, California, which is located near 2000 m asl28. Characterizing the global signature of 774–775 CE and 993–994 CE MEs, Büntgen et al.8 stated that the cosmogenic isotope content of tree rings predominantly reflects tropospheric conditions during wood formation rather than the radiocarbon in the stratosphere where it is mostly produced. As already noted, the 14C in the stratosphere mixes with that in the troposphere only in the springtime. It is feasible that the Altai larch Δ14C offset relates to the vertical radiocarbon pattern above the highlands of Inner Eurasia during late May-June when larch tree-ring growth starts.

The differences in the variations of Δ14C during the ca. 660 BCE ME across northern Eurasia could be summarized by two types of signatures: (1) a 2-year pulse of rapidly increasing concentrations followed by 2–4 years of continuously high values before a final pronounced 5–6-year decay, and (2) a slow 3–5-year increase in 14C concentrations followed by the same plateau then the signal decay. The impact of cosmic radiation appears to be more pronounced due to the event’s distinctive feature—a peak of high values separating the response to the initial impact and the decay—that returns 14C content to normal levels. This feature has not been observed in the other known MEs, although the global signatures of 774–775 CE and 993–994 CE also display some diversity in the event response, like more pronounced impact greater than a single-year sharp increase8. Thus, the expression of this SEP event in the Δ14C tree-ring series is different from that of other known ME events. This could be the result of special conditions of atmospheric mixing of cosmogenic isotope fluxes and/or of the tree’s ability to fractionate 14C and CO2 exchange fluxes between the ambient atmosphere and the tree. We will discuss these tree-constraint factors shortly but now address the coherence in the estimates of the 14C production rate for the analyzed 14C proxies.

Modeling the 14C production rate of the event

When cosmic radiation strikes the atmosphere, the newly produced cosmogenic radiocarbon is rapidly oxidized to 14CO, but it takes several months to be oxidized by OH free radicals to 14CO229,30,31. In contrast to 14C produced by very high energy galactic cosmic rays, where there is significant tropospheric production, the 14C resulting from less-energetic solar proton reactions is mainly produced in the stratosphere [e.g., 31, 14]. Stratospheric 14CO2 filters from the stratosphere down to the troposphere especially during the spring breakthrough (the Brewer-Dobson circulation), and subsequently enters the global carbon cycle. Fitting a 22-box-diffusion carbon model (CBM)8 with Gaussian processes and Bayesian inference24, we have reconstructed the probability distribution of the 14C production rate for the ca. 660 BCE ME for each of the studied tree-ring series using two CBM fitting approaches.

First, we apply CBM fitting via the Gaussian process [24, Eq. 2.7, InverseSolver in TickTack package] and estimate an average rate of 8 atoms cm−2 s−1 over one growing season (Fig. 2), which is ca. 4 times greater than the global average rate (1.6–2.2 atoms cm−2 s−1). The Altai larch, Yamal larch, and Choukai cedar-LW series produced the most coherent results. Two other series appear to have much weaker signals: the German oak series has only 50% of the estimated rate, and the Choukai cedar earlywood does not show any additional cosmic ray flux; rather, only the rate fluctuation of a typical 11-y solar cycle.

Estimation of the ca. 660 BCE ME production rate calculated with Matérn–3/2 Gaussian process nonparametric fitting of the CBM8 posterior samples: a Altai larch and b Yamal larch from this study; c Choukai cedar-EW22; d Choukai cedar-LW22, and e German oak10. The box plot visualizes the mean (black lines) and the standard deviation (red color) of the chain. The spike production exceeds the average radionuclide production rate over an 11-yr solar cycle in all the cases except for the Choukai cedar-EW series (c).

The parametric fitting to the production rate calculation [24, Eq. 2.4, SingleFitter in TickTack package] is done with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) generated posteriors that estimate more accurately the spike in 14C production rate. This modeling uses the reconstructed posterior probabilities of Δ14C (Fig. 3 top panel), which match the measured patterns shown in Fig. 1 with an increase between 12‰ and 15‰ at the peak and the time transgressive pattern of two signal signatures described earlier. The Yamal larch series shows the highest 14C production rate—4.8 times the global average (Fig. 4). The rates of increase in Altai larch and Choukai cedar-LW were 3.5 times greater. Despite the Altai larch fit being affected by the sharp rise in the second year of the spike pulse (663 BCE). The lowest rate (2.5×) was expressed in the German oak series. The Choukai cedar-EW series shows a surprisingly high rate of 4.2×, although its significance is lessened by the high uncertainty in the duration and start date of the event. Interestingly, both CBM fitting approaches revealed the exact starting date of the event.

Estimation of the ca. 660 BCE ME production rate calculated with the parametric fitting of the CBM8 via Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for a Altai larch and b Yamal larch from this study, c, d Choukai cedar-EW and cedar-LW22, and e German oak10. Top: Δ14C tree-ring series overlaid with green curves of random MCMC posteriors. Bottom14:C production rate predicted from the MCMC posterior iterations for a super-Gaussian spike (sharp rise) with a sinusoidal 11-year solar cycle24. The ME spike signal is expressed as a sharp increase in Δ14C over a short time interval. Most cases indicate a 2–4-year enhancement in the production rate, except for the event first discovered in the German oak series. The Altai, Yamal, and Choukai-LW data have the best fits of the 14C profiles. The event signature most likely starts at 664–663 BCE.

Marginal posterior probability distribution (PDFs) of the start date (a) and radiocarbon production rate (b) for the 664–663 BCE ME (former ca. 660 BCE) simulated with different Δ14C tree-ring series as denoted with different colors. Parametric Bayesian inference of the production rate PDF is shown in the equivalent of years with a steady state of 14C production. The settings of CBM are similar to those of Büntgen et al.8.

Figure 4 shows that the event pulse began at 664–663 BCE. The event’s radiocarbon variation arose from a double pulse. Overall, the coniferous tree rings define the spike signal better in both parametric and nonparametric fittings of CBM, although our modeling failed to pinpoint the position of the spike within the solar cycle phase (Supplementary Fig. 1). The calculation of this parameter is highly sensitive to the length of the Δ14C series and requires a time series 3–4 times longer than the solar cycle length. Modeling with the 20-year common distance series (669—650 BCE) yields inconsistent results due to the insufficient replication of the cycle (Fig. 3 bottom panels and Supplementary Fig. 1 third vertical panels). Another drawback may lie in the carbon box model conditioning, which operates on an 11-year solar cycle, while the Schwabe solar cycle can vary between 5 and 14 years before and during grand solar minima32.

Discussion

Our new 14C data defined the two-pulse duration, considerable magnitude, and the precise date of what was previously described as the event “around 660 BCE”. We showed that the double pulse of cosmic radiation during 664—663 BCE produced a nontypical pattern of ME cosmogenic isotope production recorded at multiple locations in northern Eurasia. The impact appears as a 2–3 year rise of 14C concentrations tailed by a 2–3-year peak (or plateau) before the signal decays. The magnitude of 14C production in 664 BCE was 3.5 and 4.8 times greater than the 11-yr average Δ14C production driven by the Schwabe solar cycle. The great magnitude of the event is evidence of the massive ejection of solar protons into the atmosphere. Sakurai et al.22 estimated the 14C production at a rate of 1.4 × 108 atoms cm−2 y−1, or ca. 3 times the annual GCR production rate. The new data show the rate of 14C production to be much greater than that found in previous studies and closer to the 774–775 CE ME magnitude. Large SEP events are rare and highly unpredictable phenomena33. Usoskin and Kovaltsov34 estimated a very weak dependence of the probability of SEP occurrence on its strength. Extreme proton events that are hundreds or thousands of times stronger than those of modern instrumental observations may recur on the timescale of hundreds of years21. In the Younger Dryas-Holocene interval, six large but infrequent solar proton events have been identified with 14C in tree rings, separated from one another by hundreds to thousands of years. The closest ME (774–775 CE) to our studied event was 1436 years later. Although an unconfirmed possible proton event was reported at ca. 810 BCE16, which is about 140 years earlier, this is more likely the part of a grand solar minimum that begins at ca. 820 BCE.

Earlier studies of the 664–663 BCE ME pointed to a possibly different type of SEP that had an extreme influx of solar protons over three consecutive years with a magnitude comparable to the 774–775 CE ME10,22, which we consider highly unlikely. With the modeling and the new data, we estimate the duration of the event as only one year with the onset at 664.5 BCE or late 664 BCE. The alpine larch tree-ring proxy (Altai) places the onset at 663 BCE. The master tree-ring width chronology for this dataset has a relatively low sample depth in this interval and is combined with the archeological tree rings over the first millennia BCE (see Methods), which may introduce a possible 1-year offset in the cross-dating. Yet, the tardy Δ14C proxy supports both the onset date and pronounced duration of the event. We contemplate that perhaps the differences in fixation of carbon among tree-ring records are affected by different site conditions influencing gas exchange between the ambient atmospheric CO2 and internal leaf CO2 concentrations, a signal that may be transferred to the composition of structural carbon (cellulose). Plants assimilate carbon by photosynthesis, regulated in part by diffusion of CO2 (including 14CO2) via gas exchange through stomata openings between foliage and the ambient atmosphere. If transpiration (water loss by evaporation) is low, the stomata may stay wide open and the atmospheric CO2 can freely enter so that photosynthesis can more readily discriminate against 14C in favor of 12C35,36,37,38. Conversely, when stomata are more frequently closed, the pool of CO2 in the leaf is reduced and the plant discriminates less against heavy isotopes (14C and 13C). Ultimately, both rates of stomatal conductance and photosynthesis determine how effective the trees will be in reducing the amount of 14C (and 13C) used to manufacture photosynthates, and both reduced stomatal conductance and increased rates of photosynthesis could favor the incorporation of more 14C in photosynthates and hence tree rings.

Trees use different physiological strategies to balance the gas exchange necessary for photosynthesis and limit water loss39,40,41. The environmental dependency of stomata conductance (a measure of the gas exchange rate due to changes in light, CO2 concentration, temperature, and humidity) affirms lower stomatal conductance rates for boreal forest biomes in cold climates than those in temperate forests42. Additionally, gymnosperm trees have been shown to have significantly lower (20%) stomata conductance than angiosperm trees41. Considering the species and environmental differences of our studied 14C tree-ring proxies, we expect the larch 14C series from the cold sites to have water-conserving physiological strategies to reduce gas exchange, leading to less discrimination against 14C, and, therefore, less noisy and better-defined signature of 14C spikes. In contrast, trees from milder climates, especially angiosperms such as oaks, exhibit greater variance in the Δ14C series. Low rates of tree photosynthesis due to weather is chronicled by narrow rings. A reduced photosynthesis rate alone could lead to increased discrimination against 14C and therefore, weaken the signal of SEP 14C in tree rings. The growth of the Altai and Yamal larch trees is strongly limited by summer temperature43,44. Figure 5 shows unfavorable overall growth conditions during the interval 664–661 BCE at these two locations, whereas Northern Europe experienced warm summers, indicating possibly contrasting conditions for gas exchange and 14C fractionation during the SEP event. However, the higher 14C contents in the larch trees during the 664–663 BCE ME may relate to a reduction in stomatal conductance that had a greater effect than low temperature on leaf gas exchange and 14C uptake in the arctic-alpine environments.

Summer temperature variations near the 664–663 BCE ME. The blue line is the temperature anomaly reconstructed from Finnish tree rings62 and orange from Yamal tree rings44. The red line is the tree-ring width index of the Altai larch chronology sensitive to summer temperature43. Z-scores are calculated for the interval −1000 to 0 with a + 12.3 °C mean of the Yamal summer (Jun 16–Aug 4) temperature and a +14.2 °C mean of the Finnish Lapland Jun–Aug temperature.

We conclude that all trees are not equally able to track the sudden increase in the level of production of 14C associated with the extreme solar radiation because of these eco-physiological effects. Therefore, coniferous trees from cold climates and high elevations could be more sensitive proxies for detecting the signal of increases in atmospheric 14CO2. The first-order assumption that there is no difference among tree species and tree habitats in terms of 14C fixation is likely more nuanced. The physiological ability of trees to regulate the effective photosynthesis and gas exchange rates varies according to temperature, moisture conditions, and altitude. More experimental studies are needed to assess the dependencies of stomatal gas exchange between leaves and the ambient atmosphere, with a specific focus on the functional detection of ME spike 14C production by tree rings.

Another possible explanation for the prolonged duration of the high Δ14C values after the initial SEP impact (Fig. 1) could be an increased residence time of 14C in the troposphere. Global fallout 14C depends on stratospheric-tropospheric exchange and is constrained seasonally by changes in the tropopause height. The maximum 14C variations in the atmosphere are observed in summer and the minimum variations in winter45. Newborn 14C atoms instantaneously oxidize to 14CO, except for 14C, which enters the global carbon cycle and gas exchange fluxes in the ocean and biosphere in the form of 14CO2. On average, the cosmogenic 14C takes several months to completely oxidize from 14CO to 14CO229. 14CO, as the incompletely oxidized form of 14C, resides in the atmosphere, where the secondary chemical conversion takes place. Tropospheric air near the surface has only 5–25 14CO molecules in 1 cm3 compared to 104 14CO2 molecules45.

The soft energy spectrum of the 664–663 BCE proton event estimated by O’Hare et al.14 implies that the 14C production maximum was shifted higher into the stratosphere and reaches 70–80% whereas under regular conditions this ratio will be 50% stratosphere /50% troposphere 14C production46,47. O’Hare et al.14 emphasized that the spike signatures of cosmogenic radionuclides (14C, 10Be, 36Cl) from three Greenland ice cores had slightly different patterns in the peak and duration of the event ranging from 2 to 6 years because the SEP-derived radionuclide production originated exclusively in the stratosphere. The mean residence time in the stratosphere is about 2 years. This slow downward atmospheric transport of radiocarbon before entering to the global carbon cycle played an important role in the pulsing temporal progression of the event structure documented by the tree rings. This temporal pattern in the 14C tree rings is sometimes called prolonged production and prolonged response8,10,11,24.

Thus, there is the time-lag of 2–3 months for 14CO to be converted to 14CO2 in the atmosphere30. Further mixing between the stratosphere and the lower troposphere occurs during the “spring breakthrough” that is also important for the onset of the signature of studied event. The length of the growing season (photosynthesis window) in the studied locations varies between 6 months for Choukai cedar and German oak (March–October), and three months (June–August) for Yamal and Altai larch (see Methods). It is possible that the enriched 14CO2 entered the carbon cycle only in late summer of 664 BCE, suggesting the pronounced manifestation of the proton event in the next spring. Both the residence time and time lag in the atmospheric 14C coincide well with the signatures of the event described earlier. If the strong burst of protons occurred in 664 BCE, the 14C abundance would be captured in the latewood of tree rings formed later in the growing season and in the ring of the following year and earlywood of 663 BCE (Fig. 1a, Fig. 4a).

Studies of the 14C bomb spike reported the highly dynamic nature of nonstructural carbohydrates in temperate forests that form a reserve of sugars and starches cycling carbon in the tree stem and roots on very different timescales from months to decades48,49. Trees may recycle the excess of 14C over the number of years especially in angiosperm species supporting growth respiration by a mixture of stored (ca. 75%) and recent (ca. 25%) carbon in the tree trunk50,51. In part, the prolonged response of 14C content in the tree-ring spike signature could be a consequence of the seasonal and longer-term dynamics of carbon storage in tree stems.

More complete characterization of the global signature of this strong ME will probably require more replication and locations than the previous investigations of the 774–775 CE and 993–994 CE MEs8. We recommend designing the test using both angiosperm and gymnosperm species from various elevations of the same location, where possible. Since the estimate of the average 14C production rate is sensitive to the phase and duration of solar cycle, having a 35–40-year time series of 14C content from tree rings is also more desirable. Finally, the double pulse of the 664–663 BCE ME onset and the prolonged waning of the 14C spike signal implies possible uncertainties complicating the use of this spike signal for single-year dating of archeological timbers and occurrences.

Methods

Data: tree rings, 14C measurements and Δ14C calculation

In this study, radiocarbon production during the SEP ca. 660 BCE was simulated with five 14C high-precision datasets from four locations in Eurasia. Two 14C series were developed specifically for this paper and three others were previously published by Park et al.10 and Sakurai et al.22. The geography of the locations and the variations of Δ14C datasets are given in Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 1b, respectively. Individual rings of known age determined with cross-dating were separated with a scalpel, their cellulose was extracted, and carbon was graphitized following standard protocols of the AMS facilities where the 14C content was measured. The specific procedures applied to develop each time series are briefly described below and referenced.

Altai larch

This 48-year 14C series (685–638 BCE) was developed from Larix sibirica conifer rings of Scythian archeological timbers excavated at the Ulandryk IV cemetery52. The Ulandryk IV is located in the upper tree-line ecotone of the Chuysky Range, Altai Mountains, Russia. Specimen # 19116 was collected from Kurgan-1 and cross-dated with the Mongun Taiga tree-ring chronology43. The growth season in the Altai’s extremely continental climate rounds a little over 3 months between late May and early September. The cellulose was pretreated with the acid-base-acid bleaching, and 14C was measured at the ICER AMS facility of the Hertelendi Laboratory of Environmental Studies (HEKAL) in Debrecen, Hungary, following the standard protocols of this laboratory53.

Yamal larch

This 21-year series spans from 671 to 651 BCE. The rings of Larix sibirica subfossil wood (specimen #1902) from fluvial deposits of the Yamal Peninsula, Russia, were dated with the Yamal multimillennial tree-ring chronology54. The site location is the taiga-tundra ecotone in a cold, semi-arid climate with less than 3-month growing season from June to August. The 14C of the prepared rings was measured at ICER AMS Laboratory in Debrecen following the same procedure used for the Altai larch series.

Choukai cedar

Two annual series from earlywood and latewood of Cryptomeria japonica were developed from a wood specimen buried in the Choukai volcanic deposits in northern Japan. Japanese native cedar, also called Japanese redwood, favors warm and moist conditions and grows between March and October, while the earlywood is produced in spring and early summer, and the latewood is formed in late summer. The calendar age of the specimen was determined with 14C wiggle matching22. Ring wood was converted to α-cellulose using the acid–alkali–acid treatment, and 14C measured by the compact AMS system of the Kaminoyama Research Institute at Yamagata University (YU-AMS), as reported by Sakurai et al.22.

German oak

14C series from the ring-porous angiosperm Quercus species from Oberhaid in Bavaria, Germany, was published in the original paper by Park et al.10 defining the ca. 660 BCE spike. Climate at the location is temperate oceanic, the growth season spans over 6 months from April to late October. The tree rings were cross-dated against the Hohenheim oak tree-ring chronology of the Holocene55. The acid-base-acid method was used for the cellulose pretreatment, and 14C was measured at the Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometer Facility at the University of California (UCI KCCAMS), Irvine, USA10.

Δ14C calculation

Radiocarbon analysis was performed on annually resolved time series of Δ14C in astronomical year numbering (Astro years) then converted to BCE. Δ14C is calculated as:

where λ is the true decay constant of 14C (1.209 × 10−4) based on the half-life of 5730 y, and t is the known age of the ring sample by dendrochronology. The fraction of modern carbon, F, is defined as the 14C/12C ratio relative to the “modern” 14C activity set to 1950 AD, which is defined as 0.95 of the 14C/12C ratio of the oxalic-I standard56 or 0.7459 of the international oxalic-II standard (SRM-4990C), see Donahue et al.57.

Modeling the 14C production rate

Radiocarbon modeling was performed using a python package called TickTack58 that can be downloaded from https://github.com/SharmaLlama/ticktack/. The code was deployed in Jupyter Notebook, a web-based interactive computing platform. The TickTack program is an open-access tool that employs various carbon cycle box models paired with a Bayesian statistical interface for modeling and analyzing cosmic radiation imprints in tree-ring radiocarbon series24. Variation in the 14C production rate was estimated using a 22-box carbon model (CBM) from Büntgen et al.8. The model includes 11 reservoirs of carbon exchange fluxes for each hemisphere, which are described in detail by Güttler et al.59 and Brehm et al.11. The CBM implements carbon partitioning among reservoirs and carbon exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean in both hemispheres and accounts the seasonal variations of net mass transport at the tropopause. The total annual exchange rate between the reservoirs is calculated with 1-month step related to the short-term lifetime of atmospheric 14CO45. 14C response to the event is calculated over the stratosphere and troposphere exchange time of 1.5 years at a shared rate of 70%/30%, respectively.

The production rate is estimated with two fitting approaches called in the TickTack package parametric and non-parametric. In the case of parametric Bayesian inference, TickTack code uses CBM loadings in the SingleFitter class object and calculates posterior probability distributions for four parameters: start date of the event, duration, amplitude, and phase of the solar cycle using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) fitting averaged from 1000 iterations24,60. The parametric inference estimates production rate Q(t), given steady state q0, including three components:

where the solar cycle has an amplitude \(A\) and phase \(\varphi \); there is a long-term trend with gradient m24.

Alternatively, a nonparametric Bayesian inference of the 14C production rate was done directly from the Δ14C time series using InverseSolver class object of the Ticktack24. This performs linear interpolation (reconstruction) from the initial steady state of production rate (1.75 atoms per m−3 s−1) via a Matérn–3/2 Gaussian process61. The box plot visualizes the mean and the standard deviation of the chain. This fitting better defines the structure of the short-lived (pulse) event since our data compiling seasonal tree-ring growth or its early and late parts. The non-parametric Bayesian inference uses a differential equation of the radiocarbon production rate

where the flow term My depends linearly on the radiocarbon state in all boxes simultaneously24.

Data availability

The original radiocarbon data used in the study is available in the papers cited here. The new radiocarbon datasets from the Altai and Yamal tree rings are accessible from the Supplementary Data and the University of Arizona Research Data Repository (ReDATA) https://doi.org/10.25422/azu.data.26392048.

References

Stuiver, M. & Quay, P. D. Changes in atmospheric carbon-14 attributed to a variable sun. Science 207, 11–19 (1980).

Lingenfelter, R. E. & Ramaty, R. Astrophysical and geophysical variations in C-14 production. Radiocarbon variations and absolute chronology, Nobel symposium 12th Proceedings (ed I. Olsson), New York Wiley, 513–537 (1970).

Damon, P. E., Cheng, S. & Linick, T. W. Fine and hyperfine structure in the spectrum of secular variations of atmospheric 14C. Radiocarbon 31, 704–718 (1989).

Miyake, F., Nagaya, K., Masuda, K. & Nakamura, T. A. signature of cosmic-ray increase in AD 774-775 from tree rings in Japan. Nature 486, 240–242 (2012).

Miyake, F., Masuda, K. & Nakamura, T. Another rapid event in the carbon-14 record of tree rings. Nat. Commun. 4, 1748 (2013).

Usoskin, I. G. et al. The AD775 cosmic event revisited: the Sun is to blame. Astron. Astrophys. 552, L3 (2013).

Jull, A. J. T. et al. Excursions in the 14C record at AD 774-775 from tree rings from Russia and America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3004–3010 (2014).

Büntgen, U. et al. Tree rings reveal globally coherent signature of cosmogenic radiocarbon events in 774 and 993 CE. Nat. Commun. 9, 3605 (2018).

Usoskin, I. G. et al. Solar cyclic activity over the last millennium reconstructed from annual 14C data. Astron. Astrophys. 649, A141 (2021).

Park, J., Southon, J., Fahrni, S., Creasman, P. P. & Mewaldt, R. Relationship between solar activity and Δ14C peaks in AD 775, AD 994, and 660 BC. Radiocarbon 59, 1147–1156 (2017).

Brehm, N. et al. Tree-rings reveal two strong solar proton events in 7176 and 5259 BCE. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–8 (2022).

Bard, E. et al. A radiocarbon spike at 14,300 cal yr BP in subfossil trees provides the impulse response function of the global carbon cycle during the Late Glacial. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 2261 (2023).

Mekhaldi, F. et al. Multiradionuclide evidence for the solar origin of the cosmic-ray events of AD 774/5 and 993/4. Nat. Commun. 6, 8611 (2015).

O’Hare, P. et al. Multiradionuclide evidence for an extreme solar proton event around 2,610 BP (∼660BC). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5961–5966 (2019).

Paleari, C. I. et al. Cosmogenic radionuclides reveal an extreme solar particle storm near a solar minimum 9125 years BP. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Jull, A. J. T. et al. More rapid carbon-14 excursions in the tree-ring record: a record of different kind of solar activity at about 800 BC? Radiocarbon 60, 1237–1248 (2018).

Menjo, H. et al. Possibility of the detection of past supernova explosion by radiocarbon measurement. Tata Inst. Fund. Res. 2, 357–360 (eds B. S. Acharya et al.) 29th Int. Cosmic Ray Conference Proceedings (Pune, India, 2005).

Brehm, N. et al. Eleven-year solar cycles over the last millennium revealed by radiocarbon in tree rings. Nat. Geosci. 14, 10–15 (2021)

Miyahara, H. et al. Recurrent large-scale solar proton events before the onset of the Wolf grand solar minimum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 (2022).

Terrasi, F. et al. Can the 14C anomaly in 1054 CE be due to SN1054? Radiocarbon (2020).

Miroshnichenko, L. I. & Nymmik, R. A. Extreme fluxes in solar energetic particle events: methodological and physical limitations. Radiat. Meas. 61, 6–15 (2014).

Sakurai, H. et al. Prolonged production of 14C during the ∼660BCE solar proton event from Japanese tree rings. Sci. Rep. 10, 660 (2020).

Rakowski, A. Z. et al. Radiocarbon concentration in sub-annual tree rings from Poland around 660 BCE. Radiocarbon https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2023.79 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Modelling cosmic radiation events in the tree-ring radiocarbon record. Proc. R. Soc. A 478, 2266 (2022).

Körner, C., Farquhar, G. & Wong, S. Carbon isotope discrimination by plants follows latitudinal and altitudinal trends. Oecologia 88, 30–40 (1991).

Shi, Z., Liu, S., Liu, X. & Centritto, M. Altitudinal variation in photosynthetic capacity, diffusional conductance and δ13C of butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii) plants growing at high elevations. Physiol. Plant 128, 722–731 (2006).

Wang, H. et al. Photosynthetic responses to altitude: an explanation based on optimality principles. N. Phytol. 213, 976–982 (2017).

Pearson, C. et al. Annual variations of atmospheric 14C between 1700 BC and 1480 BC. Radiocarbon 62, 939–952 (2020).

MacKay, C., Pandow, M. & Wolfgang, R. On the chemistry of natural radiocarbon. J. Geophys. Res. 68, 3929–3931 (1963). 1963.

Jőckel, P., Lawrence, M. G. & Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M. Simulations of cosmogenic 14CO using the three-dimensional atmospheric model MATCH: effects of 14C production distribution and the solar cycle. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 11733–11743 (1999).

Castagnoli, G. & Lal, D. Solar modulation effects in terrestrial production of carbon-14. Radiocarbon 22, 133–158 (1980).

Miyahara, H. et al. Gradual onset of the Maunder Minimum revealed by high‑precision carbon‑14 analyses. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84830-5 (2021).

Usoskin, I. G. et al. Extreme solar events: setting up a paradigm. Space Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-023-01018-1 (2023).

Usoskin, I. G. & Kovaltsov, G. A. Mind the gap: new precise 14C data indicate the nature of extreme solar particle events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e94848 (2021).

Diefendorf, A. F., Mueller, K. E., Wing, S. L., Koch, P. L. & Freeman, K. H. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5738–5743 (2010).

Prentice, I. C., Dong, N., Gleason, S. M., Maire, V. & Wright, I. J. Balancing the costs of carbon gain and water transport: Testing a new theoretical framework for plant functional ecology. Ecol. Lett. 17, 82–91 (2014).

Sperry, J. S. et al. Predicting stomatal responses to the environment from the optimization of photosynthetic gain and hydraulic cost. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 816–830 (2017).

Walker, A. P. et al. Integrating the evidence for a terrestrial carbon sink caused by increasing atmospheric CO2. N. Phytol. 229, 2413–2445 (2021).

Lin, Y.-S. et al. Optimal stomatal behavior around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 459–464 (2015).

Zhenzhu, X., Yanling, J., Bingrui, J. & Guangsheng, Z. Elevated-CO2 response of stomata and its dependence on environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00657 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Towards a universal model for carbon dioxide uptake by plants. Nat. Plants 9, 734–741 (2017).

Frank, D. et al. Water-use efficiency and transpiration across European forests during the Anthropocene. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 579–583 (2015).

Myglan, V. C., Oydupaa, O. C. & Vaganov, E. A. Development of 2,367-year tree-ring chronology for the Altai-Sayan region (Mongun-Taiga mountain range). Archeol. Ethnogr. Anthropol. Eurasia 3, 51 (2012).

Hantemirov, R. M. et al. Current Siberian heating is unprecedented during the past seven millennia. Nat. Commun. 13, 4968 (2022).

Jöckel, P. & Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M. The seasonal cycle of cosmogenic 14CO at the surface level: A solar cycle adjusted, zonal-average climatology based on observations. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 4656 (2002).

Nydal, R. Further investigation on the transfer of radiocarbon in nature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 73, 3617–3635 (1968).

Damon, P. E., Lerman, J. C. & Long, A. Temporal fluctuations of atmospheric 14C: causal factors and implications. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 6, 457–494 (1978).

Richardson, A. D. et al. Seasonal dynamics and age of stem wood nonstructural carbohydrates in temperate forest trees. N. Phytol. 197, 850–861 (2013).

Martínez-Vilalta, J. et al. Dynamics of non-structural carbohydrates in terrestrial plants: a global synthesis. Ecol. Monogr. 86, 495–516 (2016).

Kuptz, D., Fleischmann, F., Matyssek, R. & Grams, T. E. Seasonal patterns of carbon allocation to respiratory pools in 60-yr-old deciduous (Fagus sylvatica) and evergreen (Picea abies) trees assessed via whole-tree stable carbon isotope labeling. N. Phytol. 191, 160–172 (2011).

Furze, M. E. et al. Whole-tree nonstructural carbohydrate budgets in five species. N. Phytol. 221, 1466–1477 (2018).

Panyushkina, I. P., Sljusarenko, I. Y., Bikov, N. I. & Bogdanov, E. Floating larch tree-ring chronologies from archaeological timbers in the Russian Altai between 800 BC and 800 AD. Radiocarbon 49, 693–702 (2007).

Molnár, M. et al. Status report of the new AMS 14C sample preparation lab of the Hertelendi Laboratory of Environmental Studies (Debrecen, Hungary). Radiocarbon 55, 665–676 (2013).

Hantemirov, R. M. et al. An 8768-year Yamal Tree-ring Chronology as a tool for paleoecological reconstructions. Russ. J. Ecol. 52, 419–427 (2021).

Friedrich, M. The 12,460-year Hohenheim oak and pine tree-ring chronology from Central Europe; a unique annual record for radiocarbon calibration and paleoenvironment reconstructions. Radiocarbon 46, 1111–1122 (2004).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion: reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Donahue, D. J., Linick, T. W. & Jull, A. J. T. Isotope ratio and background corrections for accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon measurements. Radiocarbon 32, 135–142 (1990).

Sharma, U., Zhang, Q., Dennis, J. & Poppe, B. J. S. Ticktack: a Python package for carbon box modelling. J. Open Source Softw. 8, 5084 (2023).

Güttler, D. et al. Rapid increase in cosmogenic 14C in AD 775 measured in New Zealand kauri trees indicates short-lived increase in 14C production spanning both hemispheres. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 290–297 (2015).

Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman J. mcee: The MCMC Hammer. Astron. Soc. Pac. https://doi.org/10.1086/670067 (2013).

Williams, C. K. & Rasmussen, C. E. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2006).

Helama, S. et al. Disentangling the evidence of Milankovitch forcing from tree-ting and sedimentary records. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 871641 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank many dendrochronologists who created the long-term chronologies used in the cross-dating and AMS facility staff for help running the radiocarbon measurements. This study was funded by NASA grant 80NSSC21K1426. A.J.T.J. acknowledges partial support from the European Union and the State of Hungary, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund in the project of GINOP-2.3.4-15-2020-00007 “INTERACT” project. I.K. acknowledges Europlanet 2024 RI from the EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program grant # 871149. V.N.L. was funded by the National Measurement System Program supported by the UK Government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Heaton, University of Leeds, UK, for his unbiased review of the paper and expertise in applied statistics and radiocarbon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.T.J. and I.P. designed the study. Tree-ring samples were cross-dated and provided by I.S., V.M., R.H., and V.K. Radiocarbon content was measured by M.M., T.V., and I.K. These authors contributed equally. Radiocarbon modeling was done by I.P. and V.L. The paper was written by I.P. together with A.J.T.J. and VL. All the authors approved the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Jull has disclosed an outside interest in Hungarian and Czech Academies of Sciences to the University of Arizona. Conflicts of interest resulting from this interest are being managed by The University of Arizona in accordance with its policies. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Timothy Heaton and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alireza Bahadori and Aliénor Lavergne. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panyushkina, I.P., Jull, A.J.T., Molnár, M. et al. The timing of the ca-660 BCE Miyake solar-proton event constrained to between 664 and 663 BCE. Commun Earth Environ 5, 454 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01618-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01618-x