Abstract

Global prevalence of microplastics underscores the urgent need to investigate the ecology and biogeochemistry of the plastisphere. However, plastisphere mycobiome, particularly in terrestrial environments, remains largely unexplored. We conducted a comparative analysis of soil and plastisphere fungal communities using 125 experimental microcosms. Our results revealed distinct taxonomic structures between these two environments, with the genera Penicillium and pathogenic Alternaria being specifically enriched in the plastisphere. In comparison with soil communities, plastisphere communities exhibited weaker associations with environmental variables. Stochastic processes were found to be primary drivers of plastisphere fungal community assembly. Limited dispersal of fungal communities on soil microplastics was obtained, suggesting potential implications for taxa isolation or even diversity loss. The expanding plastisphere would pose critical planetary ecology challenges. Our findings highlight plastisphere act as unique niches for fungal communities that are less influenced by environmental variables, providing new insights into the ecology of the soil plastisphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of human society, agriculture, and industry, excessive use and consumption of plastic products have resulted in the wide distribution of plastic waste in the environment1. It is estimated that approximately 12,000 million metric tons of plastic waste will be accumulated globally by 20502. Under the actions of mechanical abrasion, thermal/photo-aging, and biological erosion, the large plastic debris can be fragmented into microplastics (diameter < 5 mm)3,4,5. Microplastics are emerging as a new type of crucial global change factor due to their ubiquities in various environments, including marine, freshwater, atmospheric, and soil ecosystems, even in the isolated and sparsely inhabited areas of this planet6,7,8,9. Given the adverse effects of microplastics on subcellular and organismic levels in the community and, eventually, on the ecological level, microplastics have raised significant concerns10,11,12,13.

Microorganisms are increasingly being studied for cascading impacts of microplastic pollution at the community level that could affect entire ecosystems. As artificially long-lived substrates, microplastic surfaces can provide a unique niche for diverse microorganisms, constituting a distinct ecological habitat called the “plastisphere”14,15,16. Recent studies have reported that the plastisphere harbored diverse microbial communities with significant differences from those in the surrounding environmental matrices17,18. Additionally, plastisphere microbial communities could concentrate antibiotic resistance genes and potential pathogenic bacteria, indicating the serious ecological implications of plastisphere19,20. Despite the scientific consensus about plastisphere, the increasing number of studies have mainly focused on the bacterial communities, with only a handful of studies on the fungal communities21. Fungi are widely distributed in the terrestrial ecosystems. They are taxonomically diverse, with 2.2 to 3.8 million species22. As mutualists, pathogens, and saprotrophs, fungi are functionally versatile and play fundamental ecological roles in driving soil carbon cycling and mediating plant mineral nutrition23,24. For instance, saprotrophic fungi are the primary decomposers of plant litters and soil organic matter due to their relatively higher capability to degrade cellulose and lignin25, and mycorrhizal fungi may contribute to the nutrient uptake of plants and increase the abiotic and biotic stress resistance of the hosts26. Additionally, fungal pathogens may jeopardize food security and reduce the productivity and health of terrestrial plant communities27. Given the vital roles of fungal communities, it is crucial and necessary to elucidate the role of the plastisphere fungal communities in terrestrial ecosystems.

Currently, plastisphere fungal communities, especially in the soil environments, are almost entirely omitted. By sampling plastisphere near human dwellings, Gkoutselis et al. have reported that soil microplastics could serve as selective artificial microhabitats that accumulate certain opportunistic human pathogenic fungi28. Similarly, Li et al. also found that the relative abundance of plant and animal fungal pathogens was higher in mulching film-derived plastisphere than in the soil samples29. However, limited soil types were used in most previous studies, so it is challenging to extrapolate or scale up this observation to broader contexts. We still lack a predictive understanding of the ecological attribution and the underlying ecological processes of fungal communities on the terrestrial plastisphere.

In this study, we collected 125 distinct soils along a large geographic and edaphic gradient across China, and explored the plastisphere and soil fungal communities by using soil microcosm experiments. We compared the taxonomic diversity of soil and plastisphere communities using high-throughput sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer 1 region and estimated patterns of compositional differences to examine the following questions: (i) whether the diversity and composition of fungal communities differ between soils and plastispheres and (ii) what underlying mechanisms shape the characteristics of plastisphere fungal communities.

Results

Composition of soil and plastisphere communities

In comparison with the soil samples, no significant difference was observed for the Shannon diversity of the fungal communities at the genus level in the plastisphere, whereas the Chao1 richness was statistically lower for the plastisphere (Fig. 1). For instance, the average richness values of the fungal communities in soil and plastisphere were 127 and 102, respectively. The fungal communities in the plastisphere and soil shared the most dominant phyla, including Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Rozellomycota (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the relative abundance of Basidiomycota was significantly greater in the plastisphere (mean 14.9%) than in the soil (mean 10.9%). Other species-rich phyla accounted for similar proportions in the plastisphere and soil communities. At the class level, the relative abundances of Sordariomycetes, Pezizomycetes, and Agaricomycetes were significantly greater in the soil, while the class Tremellomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Dothideomycetes, and Saccharomycetes were more abundant in the plastisphere samples (Supplementary Fig. 2). Assignment to guilds results in three main guilds, of which saprotrophs were the most abundant and diverse, followed by pathogens and saprotrophs (Fig. 2B). The relative abundances of the three guilds in the plastisphere were 24.8%, 8.1%, and 1.1% for saprotrophs, pathogens, and saprotrophs, respectively, while the abundances in the soil were 29.2%, 7.2%, and 0.8%, respectively. To further characterize the potential microplastic-specific fungal species, we applied the random forest method and the LEfSe analysis (Fig. 3). The random forest indicated that the genus Penicillium and Alternaria were the potential biomarker species in the plastisphere fungal communities (Fig. 3A). The LEfSe results confirmed that the genus Penicillium and Alternaria were specifically enriched in the plastisphere (Fig. 3B). In addition, the class Tremellomyctes, Eurotiomycetes, and the family Aspergillaceae were also enriched in the plastisphere.

The differentiation between plastisphere and soil communities was visualized by PCoA based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (Fig. 4). Although the distribution of samples was generally discrete, the plastisphere and soil communities were separated along the primary principal coordinate. Additionally, the three complementary non-parametric multivariate statistical tests (Adonis, ANOSIM, and MRPP) indicated the separation was statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2). To further estimate the dissimilarity in species composition between distinct locations, the species turnover and nestedness were calculated. Species turnover usually occurs among communities with high speciation rates, dispersal limitation, ecological drift, or habitat heterogeneity, whereas species nestedness often occurs in communities with nested habitat conditions and selective extinction or selective recolonization across environmental gradients30. In the current study, species turnover was a greater contributor to the beta diversity across soil and plastisphere communities. Additionally, the relative contribution of species nestedness to the total beta diversity was greater for the plastisphere fungal communities than for the soil fungal communities. The results potentially suggested that the microplastics might form nested habitats for the fungal communities.

Relationship between environmental variables and fungal communities

Canonical correspondence analysis was adopted to explore the relationship between environmental variables and the fungal communities in soil and microplastics, respectively (Fig. 5). The results showed that six variables were significantly related to the changes in the plastisphere fungal communities and eight variables for the soil fungal communities. Additionally, the weather conditions of the sampling sites (precipitation and temperature), the latitude, and the soil pH were the top four critical factors influencing the variation of the soil and plastisphere fungal communities. Partial Mantel correlations (Fig. 5) between fungal communities and each of the variables also indicated that the precipitation of the sampling site was significantly associated with the compositional variation in both the plastisphere and soil communities. The correlation results also suggested that the soil nutrients (DOC and nitrate nitrogen) were statistically associated with both the plastisphere and soil communities. To confirm the contribution of variables to the fungal communities, we carried out the MRM analysis (Supplementary Table 3-4). The overall MRM model for the soil fungal communities was significant (p < 0.001) and explained 15.2% of the variation (i.e., R2 0.152). The total nitrogen and DOC had the largest and most significant regression coefficients. For the plastisphere fungal communities, the overall MRM model explained 7.4% of the variation with a p-value of 0.044. These observations potentially suggested that in comparison with the soil fungal communities, the plastisphere fungal communities were less influenced by the environmental variables.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) between environmental variables and the plastisphere fungal communities (A). Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) between environmental variables and the soil fungal communities (B). The importance of environmental variables to the plastisphere fungal communities (C). The importance of environmental variables to the soil fungal communities (D). Correlations of the plastisphere and soil community structure (Bray–Curtis distance) with the soil and climate variables. Edge width corresponds to Mantel’s r value, and the edge color denotes the statistical significance. Pairwise correlations of the variables are shown with a color gradient denoting Pearson’s correlation coefficients. E MPs, plastisphere fungal communities; Soil, soil fungal communities.

The assembly and coexistence of soil and plastisphere fungal communities

To further explore the ecological mechanism driving the assembly processes of the communities, we parameterized the Sloan neutral model (Figs. 6A, B). Both soil and plastisphere fungal communities fitted the neutral community model, but the degree of fit was relatively higher in microplastic samples (R2 = 0.651) than in the soil communities (R2 = 0.564). Estimates of the migration parameter (m) were very low for both communities. The neutral partitions accounted for the majority of fungal genera for soil (64.1%) and plastisphere (67.1%) communities. However, the fitting proportions of abundance differed markedly between soil and microplastics, with neutral partitions accounting for 43.8% of soil fungal genera but 14.0% of plastisphere genera. The observation potentially suggested the prevalence of dominant taxa within the non-neutral plastisphere (Supplementary Fig. 3). We calculated the normalized stochasticity ratio (NST) to quantify the contribution of deterministic versus neutral assembly to the soil and plastisphere fungal communities (Fig. 6C). The NST values indicated that the plastisphere fungal communities were predominately governed by stochastic processes, with an average NST value of 58.1%, whereas the soil fungal communities were predominately governed by the deterministic assembly, with an average NST value of 40.7%.

The neutral model results of the plastisphere (A) and the soil fungal communities (B). The normalized stochastic ratios of the plastisphere and soil fungal communities (C). MPs, plastisphere fungal communities; Soil, soil fungal communities. Statistical significance is based on Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum tests; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The co-occurrence networks for soil and plastisphere fungal communities were generated (Fig. 7). The numbers of nodes and edges in the plastisphere network were 103 and 202, respectively, while the soil network had more nodes (136) and edges (369). The overall topological properties also suggested that the fungal network on microplastics showed a lower level in size and complexity according to the consistently smaller values in average degree, average clustering coefficient, average path distance, geodesic efficiency, and modularity (Supplementary Table 5). Two nodes (the genus Mrakis and Funneliformis) in the soil network were identified as the network hubs, and 51 genera were identified as the connectors. For the plastisphere fungal network, only 27 nodes were identified as the connectors. The fewer keystone nodes in the plastisphere network also suggested that the fungal network on microplastics was less complex than the soil network. Additionally, several keystone taxa of the plastisphere were pathogenic, such as the genus Coniosporium, Alternaria, and Coniosporium.

A visualization of constructed molecular ecological network for plastisphere fungal communities; different modules are shown in different colors. B visualization of constructed molecular ecological network for soil fungal communities; different modules are shown in different colors. C the within-module connectivity (Zi) and among-module connectivity (Pi) of each node in the networks. Module hubs (Zi ≥ 2.5, Pi < 0.62), connectors (Zi < 2.5, Pi ≥ 0.62), and network hubs (Zi ≥ 2.5, Pi ≥ 0.62) are identified as the keystone nodes; the vertical dashed line marks the position of 2.5, and the horizontal dashed line marks the position of 0.62.

Discussion

The definition of the plastisphere in soil is still a controversial issue. Many authors directly adopted the original definition of aquatic plastisphere in their work on soil, wherein the plastisphere was the community growing on plastic particles15,19,31,32. Several authors defined the soil plastisphere as the environment immediately under the influence of plastics, which included not only microorganisms attached to the plastic surface but also microorganisms in the soil under the influence of plastics33. However, there is a key question about the second definition: How far did the plastic effects radiate into the bulk soil? Given the slow release of leachates from plastics, the radiating effects of plastics may be negligible in a short time. Therefore, in the current study, we used the original definition of plastisphere and investigated the fungal communities growing on microplastics. Simultaneously, considering the fact that the fungal hyphae could spread across the soil and microplastic particles, the fungal communities in the soil impacted by microplastics should be involved in the plastisphere for long-term studies.

In comparison with the plastisphere bacterial communities, only a handful of studies have estimated the fungal communities on the microplastics. For the plastisphere bacterial communities, relatively lower alpha diversity was dominantly observed in comparison with the surrounding environmental matrices34,35. However, this observation was not universal for the fungi. For instance, Xiang et al.36 investigated the soil plastisphere community, including bacteria, fungi, and protists, impacted by soil mesofauna and observed that the Shannon diversity index values for fungi in the plastisphere were significantly lower than in the surrounding soil. Although the richness and diversity of fungal communities in the plastisphere were relatively lower than those in the surrounding soil, Pang et al.37 did not observe significant differences. In the current study, the diversity of plastisphere fungal communities was similar to that in the soil samples. These observations suggested that the selection mechanisms for fungal colonizing on microplastics may differ from those for the bacteria. The majority members of fungi are filamentous, such as those from Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, and can secret highly surface-active proteins and favor the attachment to microplastic surfaces38, whereas only a few bacterial members have a similar function. Thus, bacterial communities on microplastics could be specifically recruited because of the hydrophobic surfaces, low-molecular-weight additives, or other physicochemical properties of plastic particles33. Most fungal species grow vegetatively as filamentous hyphae, which may form interconnected networks between soil and microplastic particles37. This may also be why no clear separation was observed between the soil and plastisphere fungal communities in this study.

The genera Penicillium and Alternaria were identified as the indicator species for the plastisphere by both random forest and LEfSe analysis. Previous studies demonstrated that Penicillium had the ability to degrade PE. For instance, Ojha et al. (2017) isolated two fungal strains, namely Penicillium oxalicum NS4 and Penicillium chrysogenum NS10, and estimated their PE degrading abilities39. The weight loss of the PE films can be up to approximately 50% for these two strains. Similarly, Sowmya et al. (2015) isolated Penicillium simplicissimun from a local dumpsite and found this strain could produce laccase and manganese peroxidase to degradable PE40. In the current study, Penicillium was specifically enriched in the plastisphere communities, potentially confirming their ability to perform PE biodegradation. In addition, some members of Penicillium are known for their production of fungal secondary metabolites, including the eponymous antibiotic penicillin, which can kill or stop the growth of certain bacteria41. Therefore, the specific enrichment of Penicillium in the plastisphere communities may create a more favorable environment for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This may be the reason why plastisphere microbial communities could concentrate antibiotic resistance genes. The members of the genus Alternaria are a group of ubiquitous pathogenic fungi on host plants. For example, brown spot disease caused by Alternaria is one of the most destructive leaf spot diseases in a wide range of plants42. Additionally, Alternaria has been clinically associated with asthma, allergic rhinosinusitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, oculomycosis, onychomycosis, and skin infections43. This genus was identified as the indicator for the plastisphere, indicating that microplastics might be arguably the more suitable habitat for fungal pathogens compared to the soil. Similarly, Gkoutselis et al. (2024) also reported that plastics could be the more suitable habitat for fungal pathogens in their investigated systems compared to soil, and they have found numerous opportunistic human pathogens with cosmopolitan distribution and high ecological adaptability in plastisphere fungal communities, including allergenic, toxigenic, and pathogenic black fungi like Alternaria, Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Epococcum44. Furthermore, our co-occurrence network analysis also revealed that plastisphere keystone taxa were fungal pathogens, suggesting exclusive selection of the health-relevant human pathogens by microplastics. Considering the relative transferability and excellent stability of microplastics, this unique niche may act as the pathogen vectors.

Elucidating the ecological drivers controlling the community assembly is a longstanding central topic. In the current study, the dissimilarity among soil or plastisphere communities was partitioned into nestedness and turnover, and taxon turnover dominantly explained the fungal beta diversity rather than the nestedness resultant. The results suggested that the beta diversity of both the soil and plastisphere fungal communities mainly arose from variations in genus composition rather than differences in genus richness. The contribution of nestedness to the dissimilarity of the plastisphere fungal communities was relatively higher than those for the soil communities, suggesting that parts of the plastisphere communities (fewer species) were nested in other plastisphere communities (more species). This may potentially be attributed to the fact that the microplastics selectively recruit the fungal communities. Soil fungal communities exhibited higher taxon turnover across the large-scale sampling sites, potentially suggesting a possible dominance of deterministic processes.

The relationships between the environmental variables and the fungal communities also implied the contribution of deterministic processes. In the MRM analysis, the explanation of the entire MRM model was relatively higher for the variation in the soil fungal communities compared to the plastisphere communities. Less associations were also observed for the plastisphere communities and the environmental variables via the mantel analysis. The MST value of plastisphere fungal communities was significantly higher than that of soil fungal communities, suggesting that stochastic processes contributed more to the plastisphere communities.

The NCM models indicated both soil and plastisphere communities were strongly explained by neutral stochastic processes, with 65.1% and 56.4% of the community variation explained by the NCM models for the soil and plastisphere fungal communities, respectively. The results also suggested that other community assembly mechanisms, such as environmental selection and species interactions, might exist at the same time. Additionally, the NCM separated fungal taxa into neutral and non-neutral partitions. Previous studies indicated that non-neutral taxa may have different dispersal rates45. The taxa of the above partitions are found more frequently than expected, suggesting that they have higher migration ability and can disperse to more locations, whereas the taxa below the prediction represent taxa found less frequently than expected, suggesting their lower dispersal ability. Another possible reason is that the taxa are specifically recruited by the local conditions. In the current study, the abundance of the taxa below the prediction was relatively great for the plastisphere communities, which may suggest that the fungi on microplastics prefer to stay in local environments and have a low migration rate. We further calculated the niche width of the soil and plastisphere fungal communities, and the results also confirmed that the fungal communities on the microplastics had a narrower niche width in comparison with the soil communities (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, the findings in this study suggested less dispersal of fungal communities on soil microplastics. Given that the contamination is persistent, whether the microplastics would lead to taxa isolation or even diversity loss should be considered in the future.

In summary, we here revealed the composition, the co-occurrence interactions, and the assembly of plastisphere fungal communities from diverse soil environments, which extends the knowledge of the ecology of plastisphere fungal communities. The plastisphere fungal communities were mainly determined by stochastic processes, whereas soil pH and available carbon still play important roles in shaping the characteristics of plastisphere fungal communities. The specific enrichment of antibiotic-producing taxa (Penicillium) and fungal pathogens (Alternaria) by plastisphere assemblage may critically challenge the achievement of One Health. Considering the widespread microplastic contamination in different compartments of the Earth, our findings potentially highlight that there is an urgent need to classify microplastics as a global health factor.

Methods

Soil sampling and physicochemical characteristics

Soil samples were collected from each of the 125 sites (Supplementary Fig. 1), which included seminatural forests, grasslands, or unreclaimed lands. The latitude and longitude of each site were given in the Supporting Information. At each site, a 10 × 10 m plot was established, and five soil cores (0-20 cm depth and 10 cm diameter) were sampled and combined. The soils were air-died at room temperature for 3 weeks and sieved through a 2-mm mesh to remove plant litter and rocks.

The mean annual temperature and precipitation of each site were obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center [https://www.geodata.cn/]. The soil texture was measured by the laser diffraction method (Topsizer Plus, China). The total nitrogen (TN) and total carbon (TC) were determined by using an elemental analyzer (Vario Macro Cube, Elementar, Germany). The soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in the soil suspension in deionized water with a soil/water ratio of 1:5 (weight/volume). The soil available phosphorus (AP) was determined using the molybdenum-blue method after extraction with 0.5 mol/L NaHCO3 solution (w/v, 1:5)46. The soil ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3-) concentrations were colorimetrically measured in soil extracts (w/v, 1:5, 2 mol/L KCl solution) using the salicylic acid method and VCl3 procedure, respectively47,48. The soil-dissolved organic carbon content was measured using a total organic carbon analyzer (Vario TOC, Elementar, Germany) with the extraction in deionized water at a soil/water ratio of 1:10 (w/v).

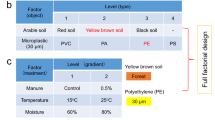

Plastisphere microcosm experiment

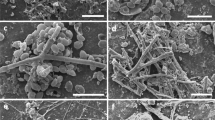

Polyethylene was used as the plastisphere substrate for the microcosm experiment because of its heavy use and frequent detection49. PE film (10 μm thickness) was purchased from the local market, cut into 5 × 5 mm square fragments, and immersed in methanol for 7 days to clean the sorbed chemicals. The micro-fragments were then dried in a fume hood and sterilized in a UV Clean Bench for 15 min prior to incubation. Approximately 500 g of soil and 1000 micro-fragments were added in a 1-L sterilized glass jar, and the microcosms were incubated at 25 °C for 180 days with 60% water holding capacity. The microplastic concentration was used on the basis of our previous investigation50,51. After the incubation, these micro-fragments from each jar were picked out by sterilized tweezers, transferred into a centrifuge tube, freeze-dried, and oscillated at 2500 rpm to remove the surface-attached soil particles. The micro-fragments without visible particles were used to estimate the plastisphere fungal communities. The soil in each jar was divided into two subsamples. One subsample was used for the analysis of soil properties (Supplementary Data 1), and the other subsample was stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and ITS amplicon sequencing

Soil DNA was extracted from each soil sample (approximately 300 mg) using the Mo Bio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Shanghai, China). For the plastisphere DNA extraction, approximately 400–500 pieces of micro-fragments were used with the Mo Bio PowerWater DNA isolation Kit. For fungal community composition, the DNA was PCR amplified, targeting the first nuclear ribosomal ITS using the primer ITS1f/ITS2 and sequenced by the Illumina MiSeq platform in a 2 × 300-bp paired-end format at Majorbio BioPharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The raw sequence data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive of China National Genomics Data Center under accession number PRJCA020199.

The Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (version 2020.2) with the DADA2 plugin was used to process the raw sequences52. The sequences were merged, denoised, and clustered into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). For the taxonomic assignment, each representative ASV was assigned using the UNITE database (version 8.3)53. Given the resolution of amplicon sequencing and the great heterogeneity among samples, the data at the genus level was used for the following analysis.

Statistical analysis

The ecological guilds of fungal ASVs were assigned using FUNGuild54. Following the FUNGuild creator, only the “highly probable” or “probable” assignments were used to avoid the possible overinterpretation, and any ASVs classified as multiple guilds were discarded. The alpha diversity, including Chao1 richness, Shannon diversity, and Pielou’s evenness of soil and plastisphere fungal communities, were estimated using QIIME255, and Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum tests were used to evaluate the difference between soil and plastisphere communities with a P value of <0.05 as statistically significant. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis distance was used to assess the broad differences between fungal communities56. Three different non-parametric multivariate statistical tests, including non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance (Adonis), analysis of similarity (ANOSIM), and multi-response permutation procedure (MRPP), were used to evaluate the magnitude of dissimilarity between soil and plastisphere fungal communities57. The biomarker genera in fungal communities associated with soil or plastisphere were estimated using the random forest method and Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe).

To estimate the relationship between environmental variables and fungal communities in the soil and plastisphere, canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was used58. A partial Mantel test was further used to assess the relationship between community structure and each environmental variable. To evaluate the relative importance of multiple factors contributing to the plastisphere microbial composition, we used the multiple regression on matrices (MRM) method, which gives a measure of the rate of change in microbial community similar for variables when other variables were held constant59.

A null model-based analysis of beta-diversity, the normalized stochasticity ratio (NST), was used to estimate the potential contribution of stochastic processes to the community assembly60. The relative importance of deterministic and stochastic processes was quantified by the index NST with 50% as the boundary point. A value of NST < 50% indicates more deterministic, and a value of NST > 50% indicates more stochastic. In addition, we used the Sloan neutral community model (NCM) to predict the relationship between the frequency with which taxa occur in a set of local communities (in this case, fungal communities of individual soil or plastisphere sample) and their abundance across the wider metacommunity (fungal communities of all plastisphere or soil samples)61. In this model, a single free parameter, m (the migration rate), represented the probability that a random loss of an individual in a local community would be replaced by dispersal from the metacommunity, as opposed to reproduction within the local community. The parameter R2 indicated the overall fit to the neutral model, which was assessed by comparing the sum of squares of residuals with the total sum of squares. We used the R package “MicEco” to estimate the calculation.

A correlation-based network analysis was performed to investigate the differences in fungal co-occurrence patterns between soil and plastisphere samples via the Molecular Ecology Network Analysis pipeline (MENA, http://ieg4.rccc.ou.edu/mena)62. The networks were conducted on the basis of Pearson correlations among all species observed in soil or plastisphere samples, followed by a random matrix theory-based approach that determines the correlation cut-off threshold in an automatic fashion. To ensure the reliability of correlation calculation, genera with > 20% occurrence frequency across the soil or plastisphere were included for calculation. The same cut-off value (0.62) was used to construct the soil and plastisphere networks. The topological indexes of the soil and plastisphere networks, including the node, the link, the modularity, the average degree, the average path length, the graph diameter, the graph density, and the clustering coefficient, were estimated63. Furthermore, we classified the network nodes into four categories based on inter-module connectivity (Pi) and intra-module connectivity (Zi): (1) peripheral nodes (Zi ≤ 2.5, Pi ≤ 0.62); (2) connectors (Zi ≤ 2.5, Pi > 0.62); (3) module hubs (Zi > 2.5, Pi ≤ 0.62); and (4) network hubs (Zi > 2.5, Pi > 0.62)64. Nodes in connectors, module hubs, and network hubs were identified as the keystone taxa65,66.

Data availability

The raw sequence data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive of China National Genomics Data Center under accession number PRJCA020199 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/s/1W5vR2Zk). The Supplementary Data 1 can be found in the data repository FigShare under the accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26763871.

Code availability

The code in this manuscript can be found in https://github.com/watertimes/plastisphere-fungal-communities.

References

Andrady, A. L. & Neal, M. A. Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. B: Biol Sci 364, 1977–1984 (2009).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Law, K. L. & Thompson, R. C. Microplastics in the seas. Science 345, 144–145 (2014).

Thompson, R. C. et al. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science 304, 838–838 (2004).

Foekema, E. M. et al. Plastic in north sea fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 8818–8824 (2013).

Hurley, R., Woodward, J. & Rothwell, J. J. Microplastic contamination of river beds significantly reduced by catchment-wide flooding. Nat. Geosci. 11, 251–257 (2018).

Evangeliou, N. et al. Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Nizzetto, L., Langaas, S. & Futter, M. Pollution: do microplastics spill on to farm soils? Nature 537, 488–488 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Effects of environmental and anthropogenic factors on the distribution and abundance of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159030 (2023).

de Souza Machado, A. A. et al. Impacts of microplastics on the soil biophysical environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 9656–9665 (2018).

Xu, S., Ma, J., Ji, R., Pan, K. & Miao, A.-J. Microplastics in aquatic environments: occurrence, accumulation, and biological effects. Sci. Total Environ. 703, 134699 (2020).

Carbery, M., O’Connor, W. & Palanisami, T. Trophic transfer of microplastics and mixed contaminants in the marine food web and implications for human health. Environ. Int. 115, 400–409 (2018).

Zhu, D. et al. Exposure of soil collembolans to microplastics perturbs their gut microbiota and alters their isotopic composition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 116, 302–310 (2018).

Koelmans, A. A. et al. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 138–152 (2022).

Zettler, E. R., Mincer, T. J. & Amaral-Zettler, L. A. Life in the “plastisphere”: microbial communities on plastic marine debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 7137–7146 (2013).

McCormick, A., Hoellein, T. J., Mason, S. A., Schluep, J. & Kelly, J. J. Microplastic is an abundant and distinct microbial habitat in an urban river. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 11863–11871 (2014).

Zhang, M. et al. Microplastics from mulching film is a distinct habitat for bacteria in farmland soil. Sci. Total Environ. 688, 470–478 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Evidence of selective enrichment of bacterial assemblages and antibiotic resistant genes by microplastics in urban rivers. Water Res. 183, 116113 (2020).

Zhu, D., Ma, J., Li, G., Rillig, M. C. & Zhu, Y.-G. Soil plastispheres as hotspots of antibiotic resistance genes and potential pathogens. ISME J 16, 521–532 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Selective enrichment of virulence factor genes in the plastisphere under antibiotic and heavy metal pressures. J Hazard Mater. 465, 133319 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Plastisphere microbiome: Methodology, diversity, and functionality. iMeta 2, e101 (2023).

Hawksworth D. L., Lücking R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol. Spectrum 5: https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0052-2016.

Bahram, M. et al. Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies drive topsoil microbiome structure and function. New Phytol. 227, 1189–1199 (2020).

Pellegrin, C., Morin, E., Martin, F. M. & Veneault-Fourrey, C. Comparative analysis of secretomes from ectomycorrhizal fungi with an emphasis on small-secreted proteins. Front Microbiol 6, 1278 (2015).

Deacon, L. J. et al. Diversity and function of decomposer fungi from a grassland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 7–20 (2006).

van der Heijden, M. G. A. et al. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature 396, 69–72 (1998).

Avery, S. V., Singleton, I., Magan, N. & Goldman, G. H. The fungal threat to global food security. Fungal Biol. 123, 555–557 (2019).

Gkoutselis, G. et al. Microplastics accumulate fungal pathogens in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 11, 13214 (2021).

Li, K. et al. Differential fungal assemblages and functions between the plastisphere of biodegradable and conventional microplastics in farmland. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167478 (2024).

Zhong, Y. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal trees influence the latitudinal beta-diversity gradient of tree communities in forests worldwide. Nat. Commun. 12, 3137 (2021).

Amaral-Zettler, L. A., Zettler, E. R. & Mincer, T. J. Ecology of the plastisphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 139–151 (2020).

Li, K., Jia, W., Xu, L., Zhang, M. & Huang, Y. The plastisphere of biodegradable and conventional microplastics from residues exhibit distinct microbial structure, network and function in plastic-mulching farmland. J. Hazard Mater. 442, 130011 (2023).

Rillig, M. C., Kim, S. W. & Zhu, Y.-G. The soil plastisphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 64–74 (2024).

Nguyen, H. T., Choi, W., Kim, E.-J. & Cho, K. Microbial community niches on microplastics and prioritized environmental factors under various urban riverine conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 849, 157781 (2022).

Mughini-Gras, L., van der Plaats, R. Q. J., van der Wielen, P. W. J. J., Bauerlein, P. S. & de Roda Husman, A. M. Riverine microplastic and microbial community compositions: a field study in the Netherlands. Water Res. 192, 116852 (2021).

Xiang, Q., Chen, Q.-L., Yang, X.-R., Li, G. & Zhu, D. Soil mesofauna alter the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes in the plastisphere during microbial succession. Sci. Total Environ. 849, 157820 (2022).

Pang, G. et al. The distinct plastisphere microbiome in the terrestrial-marine ecotone is a reservoir for putative degraders of petroleum-based polymers. J. Hazard Mater. 453, 131399 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. At least three families of hyphosphere small secreted cysteine-rich proteins can optimize surface properties to a moderately hydrophilic state suitable for fungal attachment. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 5750–5768 (2021).

Ojha, N. et al. Evaluation of HDPE and LDPE degradation by fungus, implemented by statistical optimization. Sci. Rep. 7, 39515 (2017).

Sowmya, H. V., Ramalingappa, Krishnappa, M. & Thippeswamy, B. Degradation of polyethylene by Penicillium simplicissimum isolated from local dumpsite of Shivamogga district. Environ. Dev. Sustainability 17, 731–745 (2015).

Keller, N. P., Turner, G. & Bennett, J. W. Fungal secondary metabolism—from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 937–947 (2005).

Lagopodi, A. L. & Thanassoulopoulos, C. C. Effect of a leaf spot disease caused by alternaria alternata on yield of sunflower in Greece. Plant Dis. 82, 41–44 (1998).

Pastor, F. J. & Guarro, J. Alternaria infections: laboratory diagnosis and relevant clinical features. Clin. Microbiol. Infection 14, 734–746 (2008).

Gkoutselis, G. et al. Plastiphily is linked to generic virulence traits of important human pathogenic fungi. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 51 (2024).

Burns, A. R. et al. Contribution of neutral processes to the assembly of gut microbial communities in the zebrafish over host development. ISME J. 10, 655–664 (2016).

Crouch, S. R. & Malmstadt, H. Mechanistic investigation of molybdenum blue method for determination of phosphate. Anal. Chem. 39, 1084–1089 (1967).

Miranda, K. M., Espey, M. G. & Wink, D. A. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 5, 62–71 (2001).

Rhine, E. D., Mulvaney, R. L., Pratt, E. J. & Sims, G. K. Improving the Berthelot reaction for determining ammonium in soil extracts and water. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 62, 473–480 (1998).

Xu, C. et al. Are we underestimating the sources of microplastic pollution in terrestrial environment? J. Hazard Mater. 400, 123228 (2020).

Huang, Y., Liu, Q., Jia, W., Yan, C. & Wang, J. Agricultural plastic mulching as a source of microplastics in the terrestrial environment. Environ. Pollut. 260, 114096 (2020).

Jia, W. et al. Automated identification and quantification of invisible microplastics in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 844, 156853 (2022).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Nilsson, R. H. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D259–D264 (2018).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 20, 241–248 (2016).

Webb, C. O., Ackerly, D. D., McPeek, M. A. & Donoghue, M. J. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systematics 33, 475–505 (2002).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Vegetation Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Guo, X. et al. Climate warming leads to divergent succession of grassland microbial communities. Nat. Clim. Chang 8, 813–818 (2018).

ter Braak, C. J. F. & Verdonschot, P. F. M. Canonical correspondence analysis and related multivariate methods in aquatic ecology. Aquat Sci. 57, 255–289 (1995).

Lichstein, J. W. Multiple regression on distance matrices: a multivariate spatial analysis tool. Plant Ecol. 188, 117–131 (2007).

Ning, D. et al. A quantitative framework reveals ecological drivers of grassland microbial community assembly in response to warming. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2020).

Sloan, W. T. et al. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 732–740 (2006).

Deng, Y. et al. Molecular ecological network analyses. BMC Bioinform. 13, 1–20 (2012).

Yuan, M. M. et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Chang 11, 343–348 (2021).

Guimerà, R. & Nunes Amaral, L. A. Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433, 895–900 (2005).

Röttjers, L. & Faust, K. Can we predict keystones? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 193–193 (2019).

Banerjee, S., Schlaeppi, K. & van der Heijden, M. G. Reply to ‘Can we predict microbial keystones?’. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 194–194 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42377381), the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2024TC028), and the Shanghai Sailing Program (21YF1416900).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuanze Sun, the acquisition, analysis; the experiment Siyuan Xie, the experiment Jingxi Zang, the experiment Mochen Wu, interpretation of data Jianguo Tao, interpretation of data Si Li, the writing Xinyu Du, the revision Jie Wang, the revision All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Xie, S., Zang, J. et al. Terrestrial plastisphere as unique niches for fungal communities. Commun Earth Environ 5, 483 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01645-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01645-8

This article is cited by

-

Leguminous and gramineous plant silages display unique characteristics of bacterial community ecology

Environmental Microbiome (2025)

-

Microplastics and soil microbiomes

BMC Biology (2025)

-

Biodegradable plastic exposure enhances microbial functional diversity while reducing taxonomic diversity across multi-kingdom soil microbiota in cherry tomato fields

Communications Biology (2025)