Abstract

Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas. Anthropogenically enhanced nitrogen deposition causes natural forest soils to release more nitrous oxide, exacerbating global warming. We used data from nitrogen addition experiments conducted in forests worldwide to quantify the spatially varying sensitivity of soil nitrous oxide emission to nitrogen deposition, thereby inferring soil nitrous oxide emission dynamics from nitrogen deposition data. From 1985 to 2015, nitrous oxide emitted from global forest soils increased from 3.55 to 3.85 teragrams of nitrogen per year. Nitrogen deposition contributed directly to 9.0% of global forest soil nitrous oxide emissions. The derived country-specific sensitivities of soil nitrous oxide emission to nitrogen deposition could be employed as localized emission factors for forestland nitrous oxide emission inventories. This study sheds light on a process-augmented data-driven approach to estimating global nitrous oxide emissions by synthesizing experimental and observational data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a greenhouse gas (GHG) that is 265 times more powerful than carbon dioxide (CO2) in terms of its global warming potential1. Also, N2O is an ozone-depleting substance unregulated by the Montreal Protocol2. Globally, the largest sources of N2O are natural processes in soils such as nitrification and denitrification, which are stimulated by mineral N supply3,4 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Estimating global forest soil N2O emission dynamics is an important and urgent issue, especially when forestland-related practices such as reforestation have the highest potential among the natural solutions to global climate change5.

In the 20th century, an increase in reactive nitrogen (N) caused by fertilizer use, industrial emissions, and car exhausts, enhanced N deposition in terrestrial ecosystems6 and eventually stimulated soil N2O emissions7. During the past three decades, some regions (e.g., Western Europe) have witnessed a reduction in N deposition, while that in some other areas (especially developing countries) has increased8,9,10. Soil N2O emissions resulting from the spatially and temporally varying N deposition are therefore difficult to quantify, which leads to uncertainties in the nitrogen-climate interactions in the Earth system11.

The importance of N for plant productivity was shown by Liebig in the first half of the 19th century12. In the 1850s, scientists began adding N fertilizers to grasslands at Rothamsted in England to study their effect on productivity and species richness13. N addition experiments that simulate the effect of atmospheric N deposition have been conducted across the world since the 1980s14,15,16, revealing the N-induced changes in soil GHG fluxes, shedding light on the underlying N transformation processes, and providing references for model construction and calibration17,18. Previously, global N2O emissions were extrapolated from site-level observations19,20,21, or inferred from the nitrification and denitrification processes22,23, or estimated using N isotope ratios for partitioning among N loss pathways24, or estimated from atmospheric inversions25. N addition experiments may allow for quantifying the sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N deposition change. Therefore, the global N addition experiment data accumulated over the last four decades may connect the atmospheric N deposition rate (which is relatively easy to observe from the ground or using satellites) with the varying soil N2O emissions, facilitating the estimations of regional or global N2O emission dynamics (Fig. 1).

a N addition experiment sites and natural N2O emission rate (RN2O) observation sites in global forests. b Global mean annual N deposition rate during 1985–2015. c Depiction of N addition experiment plots. C Control plot, L Low N addition plot, H High N addition plot. d Depiction of the linear model on soil N2O emission and low N input. N1 and N2 represent different N input rates, RN1 and RN2 are the corresponding N2O emission rates; sN is the sensitivity of N2O emission to N deposition; R0 is the background N2O emission rate. See “Methods” section Eq. 2 and Supplementary Note S1 for how the linear model was derived.

Estimating GHG emissions is a requirement stipulated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). According to the guidelines of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), inventories of GHG emissions are based on emission factors (EF). Specifically, the IPCC has proposed an EF4 (N2O emission per unit of N deposition) to quantify soil N2O emissions caused by atmospheric N deposition26,27. For more accurate inventories, using country-specific EF values instead of the IPCC default values is deemed good practice26. The sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N input change (sN) derived from N addition experiments coincides with EF4. However, the spatial variability of sN has resulted in a gap between site-level experiments and the global demand for country-specific EF4.

In this study, synthesizing data from N addition experiments in global forests, we first calculated the sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N deposition (sN) and the background N2O emission rate (R0) at site level. Constructed regression models on sN and R0 allowed us to estimate the two parameters on a global level. On this basis, global forest soil N2O emissions during 1985–2015 were inferred from the N deposition of the corresponding years10. Additionally, this study was intended to provide country-specific EF4 for national inventories on N2O, and also to pave an alternative way to study GHG dynamics in response to global environmental changes using experimental and observational data.

Results

Spatiotemporal variations of soil nitrous oxide emissions in global forests

Building on previous findings28,29, we inferred that a linear model could be used to describe the relationship between soil N2O emission and N deposition (see Supplementary Note S1 for inference of the linear model), although exponential or hyperbola responses may occur under high N input29. Using data from N addition experiments conducted in forests worldwide (N2O_exp dataset; Fig. 1), we calculated two key parameters for experimental sites where the N input levels are within the linear response range (≤150 kgN ha–1 yr–1; a segmented regression analysis was conducted to detect the critical level of N input, within which a linear model could be used to describe the relationship between N input and soil N2O emission; see Supplementary Note S2 for details), namely sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N deposition change (sN) and background RN2O (R0; Supplementary Table S1). Generalized linear models were built to model sN and R0 from climate, soil, and N deposition (Ndepo) variables (Supplementary Table S2). On this basis, RN2O of global forests was modeled from the N deposition rate (hereafter referred to as modeled RN2O; Fig. 1).

Modeled RN2O values were validated with natural N2O observations (from forest sites where no experiment was conducted; N2O_obs dataset). The modeled RN2O generally agree with the observed values at site level (R2 = 0.65; Supplementary Fig. S2), which proves the accuracy of our estimation. Additionally, natural N2O observations compiled by Kesik et al. 30 were used to independently test the performance of our models; the modeled RN2O also agreed with the observed values (R2 = 0.70; Supplementary Fig. S3). On the grid level, the modeled RN2O of global forest soils was crosschecked with RN2O extrapolated from natural RN2O observations (using the random forest regression method; see Supplementary Note S3 for details). The good agreement of RN2O values estimated from the two independent datasets using two different approaches further confirmed the reliability of the modeled RN2O (R2 = 0.90, Supplementary Fig. S4).

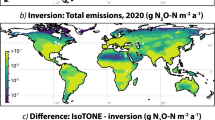

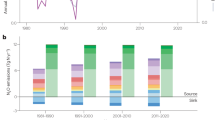

Global forest soil N2O emissions were estimated to have first increased from 3.55 TgN2O-N yr–1 in 1985 to 3.96 TgN2O-N yr–1 in 2005, and then slightly decreased to 3.85 TgN2O-N yr–1 in 2015 (Fig. 2a). The average emission was 3.76 ± 0.74 TgN2O-N yr–1. Biome-mean RN2O significantly increased from 0.71 ± 0.14 kgN2O-N ha–1 yr–1 in boreal forests to 1.24 ± 0.24 kgN2O-N ha–1 yr–1 in tropical forests (p < 0.001; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S5). Random forest regression method also revealed the same gradient in biome-mean RN2O (Fig. 2b). Countries/regions with high RN2O values, including Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Southeast Asia, Amazon and Congo rainforests, and Chilean temperate rainforest were identified as hotspots for forest soil N2O emissions (confidence level > 0.95; Fig. 3). Two of the identified countries, India and China, contributed to 35.8% of the increase in forest soil N2O emissions from 1985 to 2015.

a Temporal variation of N2O emissions from global forests. Different colors represent emissions from different biomes. b Statistical distribution of RN2O estimated using models derived from nitrogen (N) addition experiments. c Statistical distribution of RN2O estimated using natural RN2O observations using random forest method. Black dots represent the estimated mean RN2O of each biome, and error bars represent the standard errors of the estimates. Significance levels of the differences between biome-mean RN2O values: *** p < 0.001.

a Mean soil N2O emission rate (RN2O) of global forests during 1985–2015. b Latitudinal gradient of RN2O, where the black line represents the latitudinal mean RN2O, and the gray shading indicates the standard error of the mean value. c Hotspots of mean RN2O during 1985–2015, where different colors indicate different confidence levels. d–f Show the change in RN2O (∆RN2O) during different periods.

Sensitivity of soil nitrous oxide emissions to nitrogen deposition

In this study, RN2O was modeled from the sensitivity of RN2O to Ndepo (sN). The validated accuracy of the modeled RN2O could indirectly support the reliability of the intermediate parameter sN (which was modeled from environmental factors; Supplementary Table S2). Moreover, we calculated sN from the total N loss rate and N loss pathway parameters (derived from another N addition experiment dataset; Ncycle_exp dataset) to validate the modeled sN (see Supplementary Note S4 for details). The biome-mean sN agreed well with the calculated values (r = 0.998), further supporting the accuracy of the modeled sN (Fig. 4).

a Latitudinal gradient of sN, where the black line represents the latitudinal mean sN, and gray shading represents the standard error of the mean value. b Map of global forest soil sN. c Hotspots of sN in global forests, where different colors indicate different confidence levels. d Biome-mean sensitivity of total N loss to N deposition (c1). e Biome-mean sensitivity of N leaching to N deposition (c2). f Comparison of biome-mean sN calculated from N loss pathway parameters (Eq. 3) and sN estimated with generalized linear model. O: Tropical forest; T: Temperate forest; B: Boreal forest. Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

The global mean sN in forest ecosystems was estimated to be 0.013 ± 0.005 kgN2O-N kgN–1 (Table 1). Across biomes, sN increased significantly from 0.010 kgN2O-N kgN–1 in boreal forests to 0.015 kgN2O-N kgN–1 in tropical forests (p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition to the Congo rainforest and some developing countries (China, India, Brazil, Mexico), Southeastern United States, Western Europe, Northwestern Canada, and Eastern Siberia were detected as the global hotspots of sN (confidence level > 0.95; Fig. 4). Also, we found a significant positive correlation between Ndepo.cv and sN (p = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S6).

Environmental factors underlying forest soil nitrous oxide emissions

Soil texture was the most important factor in explaining the spatial variation of RN2O. Across biomes, soil clay content alone contributed to 38–47% of the explainable variation in RN2O. In temperate and boreal forests, the coefficient of interannual variation in N deposition (Ndepo.cv) explained 28–38% of the variation in RN2O. During the time of research (1985–2015), N deposition rate and its variation (Ndepo and Ndepo.cv) dominantly controlled the temporal change of RN2O, wherein N deposition contributed more than 54% of the explainable variation in all biomes (Fig. 5).

a Relative importance (%) of environmental factors for the spatial variation of global forest soil N2O emission rates. b Relative importance (%) of environmental factors for the temporal variation of global forest soil N2O emission rates. MAP mean annual precipitation, MAT mean annual temperature, Ndepo mean annual N deposition rate. MAP.cv, MAT.cv, and Ndepo.cv are the coefficients of interannual variation. Sand soil sand content, Clay soil clay content.

Globally, N deposition in forests directly induced N2O emissions of 0.3 ± 0.09 TgN2O-N yr–1, accounting for 9.0 ± 3.8% of the total emissions from global forest soils (Fig. 6). The direct contribution of N deposition to soil N2O emissions was the highest in temperate forests (15.4%; Fig. 6).

Discussion

Global hotspots of forest soil nitrous oxide emission and underlying environmental factors

From 1985 to 2015, accompanying the increase in N deposition10, annual N2O emission from global forest soils increased by ~9% (i.e., 0.3 TgN2O-N yr–1). In addition to the rainforests of the Amazon and Congo, where RN2O was high throughout the studied period, some developing countries such as India, China, and Mexico experienced a noticeable increase in forest soil RN2O (Fig. 3). This implies a risk of developing countries becoming new N2O emission hotspots. We present country-specific RN2O to highlight the change in RN2O during 1985–2015 (Supplementary Table S3).

Soil N2O emission rates are influenced by climate, soil type, and N deposition factors4. Higher temperatures accelerate N turnover31, and thereby increase N loss from soil. In addition, highly weathered soils with more clay content favor the formation of an anoxic microenvironment, facilitating denitrification and enhancing soil N2O production32,33. The high magnitudes of precipitation and its variations (e.g., wetting-drying) may alter the nitrogen and oxygen availabilities in the soil, accelerating nitrifier and denitrifier activities and enhancing RN2O34. These factors may explain the high soil RN2O in tropical rainforests as well as the general trend for soil RN2O to decrease from lower to higher latitudes. Besides, soil chemical properties such as pH and organic carbon content were found to influence the nitrification and denitrification pathways, which may also explain the spatial gradient of soil RN2O35,36,37. The soil chemical properties were not used in our models because of weak correlation with the target variables such as sN (see Supplementary Fig. S7; this is probably because the soil chemical properties are highly variable and the available data could hardly match with the observed N2O emissions in terms of temporal coverage), more accurate predictions of soil N2O emissions may be obtained in the future when dynamic global datasets of soil variables become available.

In this study, we created a process-augmented data-driven approach to analyze global forest N2O emission dynamics using N addition experiments and N deposition data (Supplementary Fig. S8). This approach applies ecosystem processes quantified by manipulative experiments to augment the predictive capability of data-driven models. Traditional data-driven methods (such as regression models and machine learning algorithms) for regional estimation are limited by the spatial and temporal coverage of observations38. Soil N2O emission, which is notable for high spatial and temporal variation, is difficult to estimate at large spatial and temporal scales using a data-driven approach. In contrast, our approach augmented the predictive capability of data-driven regression models with a generic and quantifiable process wherein N deposition drives soil N2O emissions24. Thus, the limited spatial and temporal coverage of experimental data was relieved, permitting reliable estimates of regional and global forest soil RN2O dynamics to be obtained (Table 2).

Recent trends indicate that the boundary between data-driven and process-based approaches is increasingly becoming indistinct39,40. For example, the application of machine learning methods in the parameterization of process-based models41, or the integration of process-based knowledge into machine learning modeling42, manifests the power of big data in Earth and environmental studies. Our study combined data-driven linear regression models with a process-based mathematical model (Supplementary Fig. S8), showing that relatively small datasets could also be applied to derive global estimations through the integration of data-driven and process-based approaches.

Our study provides a prototype for a method that would potentially bridge the gap between the site-level experimental data (which are relatively scarce, but inherently process-related) and the demand for global GHG budgets. Other manipulative experiments (such as warming, precipitation manipulation, and CO2 enrichment experiments) could also be used to estimate regional GHG emissions, as long as the relationship between the target variable and its driving factor can be described by a mathematical model (such as Eq. 2 in the “Methods” section), and the relevant parameters are quantified. For instance, the exponential relationship between soil temperature and soil respiration rate, and the temperature sensitivity (Q10) derived from warming experiments may be applied to estimate global soil CO2 emissions.

Spatially varying sensitivity of soil nitrous oxide emission to nitrogen deposition and its implications

In this study, we quantified the sensitivity (sN) of RN2O to Ndepo in global forests on a grid level. The country-specific sN values were derived for 145 countries, which can be used as localized emission factors (EF4) for estimating atmospheric N deposition-induced N2O emissions (Supplementary Table S3).

According to IPCC guidelines, the default value of EF4 is 1%26. However, the syntheses of field research on the emission factors in forests usually lead to higher values43,44, indicating that soil N2O emissions from forests may be underestimated if the default value is used. In this study, the mean sN of global forests was estimated to be 0.013 kgN2O-N kgN–1 (equivalently 1.3%). Previously, the response of soil N2O emission to N deposition has been analyzed on a regional or global scale using data from N addition experiments (where simulated N deposition caused the change in soil N2O emission)43,45,46 or using N isotope model (which could partition among N loss pathways and link N2O emissions to N input sources)24; our result is within the range of previous estimates (0.9–6%). In addition, the high spatial variation of sN (Fig. 4) indicates the necessity to use localized rather than default EF4 values in national inventories.

sN was found to decrease from lower to higher latitudes (Fig. 4), indicating that soil N2O emissions from tropical forests are more responsive to N deposition. Because sN is dependent on the total N loss (as indicated by the sensitivity of total N loss to Ndepo; c1) and the N loss pathways (as indicated by the sensitivity of N leaching to Ndepo (c2) and the nitrification and denitrification end-product ratio; Supplementary Note S4), their spatial gradients can help explain the gradient of sN. In low- and mid-latitude regions, excessive N deposition causes a higher proportion of N to be lost overall (i.e., higher c1; Fig. 4d). Meanwhile, c2 is higher at mid- and high-latitudes probably because of the high water-permeability of the sandy soil47 (Fig. 4e), which suggests a higher proportion of N being lost via the leaching pathway. Combined, they lead to a higher proportion of N loss in gaseous form in the lower latitudes. Moreover, the nitrification and denitrification end-product ratio (the ratio of RN2O to the total emission rate of gaseous N) tends to be lower in high-latitude forests48 where the high soil organic C content may support complete denitrification to N249. It also contributes to the gradient in sN.

Similar to Q10 indicating the sensitivity of soil respiration to temperature change50,51, sN indicating the sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N deposition may be a relatively stable parameter owing to resource constraints52 and stability of microbial community functions53, which means sN may serve as an important parameter in global change studies. For instance, sN may be used as an indicator of N status because a higher fraction of deposited N would be lost from a N-saturated forest than from a N-limited forest54,55. Thus, forests with lower sN may be more N-limited. Moreover, combining the sensitivity parameters (e.g., Q10, sN) may allow for modeling the responses of terrestrial ecosystems to multiple environmental forcing factors such as increased temperature and N deposition56. From this perspective, manipulative experiments probing the varying responses of ecosystems to environmental changes may be integrated (Eq. 1 as a conceptual framework), providing an alternative way to predict the ecosystem dynamics.

where sT, sW, sN are the sensitivities of the target variable to the changes in temperature (∆T), precipitation (∆P), and N deposition (∆Ndepo). f1, f2, f3 are functions describing the relationships between the target variable and the environmental variables and sensitivities (like Eq. 2 in the “Methods” section).

Significant influence of nitrogen deposition on soil nitrous oxide emission dynamics, and limitations

N deposition could influence soil N2O emission both directly (through the input-output relationship) and indirectly (by changing sN and R0). The positive relationship between Ndepo.cv and sN (Supplementary Fig. S6) implies that increasing N deposition may increase sN and further enhance soil N2O emission. For example, the gradually elevated N deposition caused by biomass burning in Northwestern Canada and Eastern Siberia10 may have led to higher sN in these regions (as compared to other forests at the same latitude; Fig. 4). This also suggests that the effect of N deposition on soil N2O emissions may be magnified in regions with an increasing loads of deposited N. Similarly, deposited N could gradually accumulate in the ecosystem and increase the local N pool, thus increasing the background N2O emission (R0) from locally mineralized N.

It is worth noting that the quantified contribution rate of N deposition to global forest soil N2O emission (9.0%) should be interpreted as the direct contribution of N deposition (i.e., not considering the gradually elevated sN or R0 by N deposition over time). This value falls within the range of the direct contribution rate estimated using the 15N tracing technique (6–13%)57. Considering both the direct and indirect effects of N deposition, however, the overall contribution rate could be even higher; for instance, N deposition may have contributed to 9–35% of the global soil N2O emission (direct and indirect effects combined) during 1850–2020 according to the estimates by Harris et al. 24.

In this study, the linear relationship between RN2O and Ndepo was based on the assumption of a stable ecosystem (Supplementary Note S1), which may result in estimation limitations. We used only experimental data with N addition rates no higher than 150 kgN ha–1 yr–1, because the ecosystem’s capability to transform and retain N may be significantly changed by exceedingly high rates of N addition29,55. However, there is also a probability of long-term high N deposition changing ecosystem properties, resulting in altered sN or R0. RN2O values estimated for some tropical forests were lower than the observed values (Supplementary Fig. S2; points in the lower-right corner). One possible explanation is that high Ndepo may have gradually enhanced sN, leading to an exponential response of RN2O to Ndepo. In this case, RN2O calculated using a linear model may lead to underestimation. Different N forms (including ammonium, nitrate, urea, etc.) were used in N addition experiments (Supplementary Fig. S9) to simulate the effects of deposited inorganic and organic N. Although N form may not be a dominant factor of soil N2O emission58, future research could explore the responses of N2O emissions to different forms of N input and better connect with realistic N deposition. Additionally, climate and land use change may affect sN and R0, adding to the uncertainties in our estimates.

From another perspective, the stable state assumption, and hence the static parameters used (i.e., sN and R0), are concessions that have to be made when long-term N addition experiments are scarce. In the future, we may be able to predict the temporal changes in sN and R0 under a changing environment with accumulated long-term experimental data. In this way, the capability of our approach may be further extended to allow estimation of soil N2O dynamics over past centuries, and prediction of N2O emissions in future scenarios of climate and N deposition change6.

Therefore, we call for long-term N addition experiments worldwide with holistic observations of N pools and fluxes and microbial community changes (especially nitrifiers and denitrifiers). The studies can provide a comprehensive and quantitative view of the N cycling processes, and may also extend the capability of the process-augmented data-driven approach to predict global N2O emission dynamics in future climate scenarios, thereby allowing manipulative experiments to play an important role in global change research.

Methods

Compiled N experiment data from global forests were used to estimate the two key parameters connecting soil N2O emission (RN2O) with N deposition, namely the sensitivity of soil N2O emission to N deposition (sN) and the background soil N2O emission rate (R0). In combination with the N deposition data, we modeled RN2O in global forests on a grid level. Modeled RN2O was validated using the observed RN2O compiled from non-experimental sites. We also used the random forest regression method (with natural soil N2O observations from non-experimental forests as input) to estimate RN2O and cross-validate the modeled RN2O on the grid level. Additionally, an independent dataset was compiled from global N addition experiments to quantify the total N loss rate and N loss pathways, which was then used to validate the estimated sN. The data analysis processes were illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S10.

Data compilation

We systematically compiled data from N addition experiments performed worldwide. First, we searched for literature published before 01/01/2022 in the Web of Science Core Collection and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) Theses and Dissertations Database using the following keywords: “forest” and “greenhouse gas” or “nitrous oxide” or “N2O”. We retrieved 7416 papers and theses, which were then manually refined based on the following criteria: (i) literature was relevant to N addition experiments conducted in forests with records of the location, time, and N addition dose; (ii) RN2O was investigated at the N addition experiment site and measured using the gas chromatography technique59. The gas chromatography technique is a classic and widely used method to measure soil N2O emissions; we used data measured with this method for the consistency and comparability of data. A total of 553 observations from 102 sites (referred to as experiment sites hereafter) were compiled to form N2O_exp dataset (Fig. 1; Supplementary Data S1). Concurrently, we extracted auxiliary information on environmental factors from the studies, including the mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), mean annual N deposition rate (Ndepo), soil clay content (Clay), soil sand content (Sand), and Ndepo corresponding to the year(s) of the experiment. For sites that did not provide all auxiliary information, we filled in the missing data using spatial datasets based on coordinates. Data provided in the figures were extracted using the GetData software60.

To validate the estimated RN2O, we compiled natural RN2O observation data to form N2O_obs dataset (Supplementary Data S2). The retrieved papers and theses were refined based on the following criteria: (i) RN2O was investigated in the field59, and (ii) neither N nor any form of fertilizer was artificially added to the site. A total of 291 observations from 152 sites (referred to as natural observation sites hereafter) were compiled (Fig. 1). Auxiliary information on the sites was extracted from the literature or supplemented by using the aforementioned spatial datasets.

In addition, we compiled a Ncycle_exp dataset (Supplementary Data S3) to validate the model-estimated sN. The data were extracted from 42 papers retrieved using the following criteria: (i) N addition experiments were conducted in forests with records of the location, time, and dose of N addition; (ii) the total N loss rate (Nloss, including the gaseous and leaching loss of N), the N leaching rate (Nleach), or the rate of change of the N pool (∆Npool) for the sites were observed or derived. This dataset contained 169 observations from 37 sites (Supplementary Fig. S11). Please refer to Supplementary Data S3 for detailed information about inferring the total N loss rate from the annual change of soil N pool, and the quantification of N loss and N leaching parameters for each site.

Linear model on soil nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen input

Nitrogen (N) deposited to a certain ecosystem will either be retained or lost through leaching and gaseous N emissions (N2O, NO, N2, and NH3)61. The capability of an ecosystem to transform and retain N is constrained by various resources56 and is relatively stable while the ecosystem is in a stable state62,63. Also, N leaching loss was found to increase nearly linearly with Ndepo at watershed or regional scales64,65. Moreover, the proportion of N emitted as N2O is dependent on abiotic conditions66,67,68, which stabilizes on large scales69. Therefore, we assembled these findings and inferred a linear relationship between Ndepo and RN2O on large scales under the framework of a Gray Box conceptual model28(see Supplementary Note S1 for equational inference of the linear model).

Previous studies also found that soil N2O emission responds nearly linearly within a certain level of N input, while exponential or hyperbola responses may occur under high N input rates29,55. Based on a segmented regression analysis using N2O_exp dataset (Supplementary Note S2), and also with reference to previous studies70,71,72,73,74, we determined that the critical level for N addition rates was 150 kgN ha–1 yr–1. This level is higher than the Ndepo in global forests during 1985–2015 (under 50 kgN ha–1 yr–1), but the response of soil N2O emission to N input may not significantly change below this level (Supplementary Fig. S12).

Therefore, we used a linear model in this study to describe the relationship between Ndepo and RN2O (Eq. 2) in forest ecosystems and to quantify RN2O in the following sections.

where RN2O is soil N2O emission rate (unit: kgN2O-N ha–1 yr–1); Ndepo is atmospheric N deposition rate (unit: kgN ha–1 yr–1); sN is the change in RN2O per unit of change in Ndepo (unit: kgN2O-N kgN–1), which is referred to as the sensitivity of RN2O to Ndepo. R0 is the background N2O emission without exogenous N input (derived from locally mineralized N; unit: kgN2O-N ha–1 yr–1).

Generalized linear model on the sensitivity of soil nitrous oxide emission to nitrogen deposition, and validation

To derive the sN and R0 of experiment sites, a linear model was constructed for each 0.5° × 0.5° grid that contains N input data within the linear response range (≤150 kgN ha–1 yr–1), to match with the spatial resolution of Ndepo and environmental factors. The slope and intercept of the linear model are the sN and R0 of the grid, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Then, we modeled sN and R0 with environmental factors. Because neither sN nor R0 followed a normal distribution (Supplementary Fig. S13), we used generalized linear models. In the initial models, we used a set of explanatory variables, including Clay, Sand, MAT, MAP, Ndepo, and coefficients of interannual variation (MAT.cv, MAP.cv, Ndepo.cv). In the refined models, Ndepo, Ndepo.cv, Sand, Clay, and their interactions explained 91.1% of the deviance in sN; and MAT, MAP, MAP.cv, Ndepo, Ndepo.cv, Sand, Clay, and their interactions explained 43.2% of the deviance in R0 (Supplementary Table S2).

N2O_obs dataset contains natural RN2O observations from forests worldwide (Fig. 1). Outliers outside 3 times the interquartile range were excluded from further analysis; the observations of the same year were aggregated to 0.5° × 0.5° grids (n = 208). We estimated the sN and R0 for each grid-year that has observational data using the constructed generalized linear models. RN2O values were then estimated from Ndepo data of the corresponding grid-years using Eq. 2. The estimated and observed RN2O were compared to test the reliability of our approach.

In addition, sN could be calculated from the total N loss (as indicated by the sensitivity of total N loss to Ndepo; c1) and the N loss pathways (as indicated by the sensitivity of N leaching to Ndepo (c2) and the nitrification and denitrification end-product ratio (c3)). We used Eq. 3 for the calculation (see Supplementary Note S4 for how the equation was derived). The calculated and modeled biome-mean sN values were compared to validate the model-estimated sN.

where c1 is the sensitivity of total N loss (Nloss) to N input (\({c}_{1}=\frac{\Delta {N}_{{loss}}}{\Delta {N}_{{depo}}}\); unit: kgN kgN–1), c2 is the sensitivity of N leaching (Nleach) to N input (\(\left(\right.{c}_{2}=\frac{\Delta {N}_{{leach}}}{\Delta {N}_{{depo}}}\); unit: kgN kgN–1), c3 is the nitrification and denitrification end-product ratio (\({c}_{3}=\frac{{R}_{N2O}}{{R}_{N2}+{R}_{{NO}}+{R}_{N2O}}\); unit: kgN2O-N kgN–1).

Calculating global forest soil nitrous oxide emissions, and analyzing the underlying environmental factors

Using the generalized linear models, we estimated the sN and R0 of global forests with environmental factors. In combination with global Ndepo data during 1985–201510, RN2O of all grid-years were modeled using Eq. 2. Summing up the products of modeled RN2O and forest area in the corresponding year, we obtained global N2O emission budgets (Eq. 4). The biome-mean and country-specific RN2O and sN values were calculated as the arithmetic mean of the grids in the same category. The standard error of modeled RN2O was calculated as the propagated error from the estimated sN and R0.

where RN2O-i,j is the RN2O of grid i in year j (unit: kgN2O-N ha–1 yr–1); Areai,j is the forest area of grid i in year j (unit: ha).

In parallel, RN2O of global forests was estimated with natural RN2O observations from non-experimental sites using the random forest regression method (see Supplementary Note S3 for details), which was to compare with and verify the reliability of the modeled RN2O on grid level.

To test if the mean RN2O of different biomes or years were significantly different, we used bootstrap method75. Pearson’s r was used to indicate the correlation between normally distributed variables; Spearman’s rho was used to indicate the correlation between variables that were not normally distributed. In addition, we used “relaimpo” package76 to analyze the relative effects exerted by different environmental factors on the spatial and temporal variations of RN2O. The relaimpo package attributes the explained variation of RN2O to multiple environmental factors, thereby indicating the relative importance of the factors. Specifically, we used RN2O and the coefficient of temporal variation (RN2O.cv) as response variables in the relative importance analyses of spatial and temporal variations of RN2O, respectively.

Furthermore, the linear model on RN2O and Ndepo (Eq. 2) distinguishes between N-deposition-induced N2O emission (i.e., the product of Ndepo and sN) and N2O from mineralized native N (i.e., background emission rate R0), which enabled quantification of the direct contribution (%) of N deposition to soil N2O emissions using Eq. 5.

The data analysis processes were conducted in R77 (Supplementary Code S1). A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for all tests. ArcGIS software78 was used for mapping. Hotspots of sN and RN2O were detected using Getis-Ord Gi* method in ArcGIS79.

Data availability

Compiled soil N2O emissions from experimental N addition forests (N2O_exp dataset; Supplementary Data S1), soil N2O emissions from non-experimental forests (N2O_obs dataset; Supplementary Data S2), nitrogen cycle parameters from experimental N addition forests (Ncycle_exp dataset; Supplementary Data S3), and the global forest environmental factors dataset (Supplementary Data S4) have been archived in Zenodo for public accessibility (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11077130)80. Global temperature and precipitation data were obtained from the Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/cru_ts_4.03/), soil texture data were obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/), N deposition data were derived from a global N deposition product modeled with meteorological data and data from anthropogenic emission inventories10 (https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/197613), forest cover and change data were from a global land cover product81, and biome boundary information was obtained from the Global Forest Monitoring Project82.

Code availability

R code used for data analysis in this study (Supplementary Code S1) have been archived in Zenodo for public accessibility (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11077130)80.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1535 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Ravishankara, A., Daniel, J. S. & Portmann, R. W. Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326, 123–125 (2009).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Butterbach-Bahl, K., Baggs, E. M., Dannenmann, M., Kiese, R. & Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: how well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130122 (2013).

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11645–11650 (2017).

Galloway, J. N. & Cowling, E. B. Reactive nitrogen and the world: 200 years of change. Ambio 31, 64–71 (2002).

Vitousek, P. M. et al. Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: sources and consequences. Ecol. Appl. 7, 737–750 (1997).

Yu, G. et al. Stabilization of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in China over the past decade. Nat. Geosci. 12, 424–429 (2019).

BassiriRad, H. Consequences of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in terrestrial ecosystems: old questions, new perspectives. Oecologia 177, 1–3 (2015).

Ackerman, D., Millet, D. B. & Chen, X. Global estimates of inorganic nitrogen deposition across four decades. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 33, 100–107 (2019).

Gruber, N. & Galloway, J. N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451, 293–296 (2008).

Liebig, J. Die organische Chemie in ihrer Anwendung auf Agricultur und Physiologie (Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, 1840).

Silvertown, J. et al. The Park Grass Experiment 1856–2006: its contribution to ecology. J. Ecol. 94, 801–814 (2006).

Wright, R. F. & Rasmussen, L. Introduction to the NITREX and EXMAN projects. For. Ecol. Manag. 101, 1–7 (1998).

Aber, J. D. & Magill, A. H. Chronic nitrogen additions at the Harvard Forest (USA): the first 15 years of a nitrogen saturation experiment. For. Ecol. Manag. 196, 1–5 (2004).

Du, E. et al. NEECF: a project of nutrient enrichment experiments in China’s forests. J. Plant Ecol. 6, 428–435 (2013).

Gordon, B. B. Connecting mathematical ecosystems, real-world ecosystems, and climate science. New Phytol. 202, 731–733 (2014).

Jeffrey, S. D. et al. Using results from global change experiments to inform land model development and calibration. New Phytol. 204, 744–746 (2014).

Matson, P. A. & Vitousek, P. M. Ecosystem approach to a global nitrous oxide budget. Bioscience 40, 667–672 (1990).

Yin, Y. et al. Evaluation of variation in background nitrous oxide emissions: a new global synthesis integrating the impacts of climate, soil, and management conditions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 480–492 (2021).

Stehfest, E. & Bouwman, L. N2O and NO emission from agricultural fields and soils under natural vegetation: summarizing available measurement data and modeling of global annual emissions. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 74, 207–228 (2006).

Bouwman, A. F. et al. Global trends and uncertainties in terrestrial denitrification and N2O emissions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. Biol. Sci. 368, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0112 (2013).

Li, C., Aber, J., Stange, F., Butterbach-Bahl, K. & Papen, H. A process-oriented model of N2O and NO emissions from forest soils: 1. Model development. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 4369–4384 (2000).

Harris, E. et al. Warming and redistribution of nitrogen inputs drive an increase in terrestrial nitrous oxide emission factor. Nat. Commun. 13, 4310 (2022).

Thompson, R. L. et al. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 993–998 (2019).

IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, 2006).

IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2019).

Cen, X., Li, M., Xu, L., Zhu, J. & He, N. Atmospheric N deposition significantly enhanced soil N2O emission from eastern China forests. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy 36, e2021GB007289 (2022).

Kim, D.-G., Hernandez-Ramirez, G. & Giltrap, D. Linear and nonlinear dependency of direct nitrous oxide emissions on fertilizer nitrogen input: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 168, 53–65 (2013).

Kesik, M. et al. Inventories of N2O and NO emissions from European forest soils. Biogeosciences 2, 353–375 (2005).

Li, Z. et al. Global variations and controlling factors of soil nitrogen turnover rate. Earth Sci. Rev. 207, 103250 (2020).

Smith, C. J. & Patrick, W. H. Nitrous oxide emission as affected by alternate anaerobic and aerobic conditions from soil suspensions enriched with ammonium sulfate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 15, 693–697 (1983).

Jayarathne, J. et al. Effect of aggregate size distribution on soil moisture, soil-gas diffusivity, and N2O emissions from a pasture soil. Geoderma 383, 114737 (2021).

Kiese, R., Papen, H., Zumbusch, E. & Butterbach-Bahl, K. Nitrification activity in tropical rain forest soils of the Coastal Lowlands and Atherton Tablelands, Queensland, Australia. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 165, 682–685 (2002).

Zhang, Y., Zhao, W., Cai, Z., Muller, C. & Zhang, J. Heterotrophic nitrification is responsible for large rates of N2O emission from subtropical acid forest soil in China. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69, 646–654 (2018).

Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Zhu, T. & Cai, Z. The mechanisms governing low denitrification capacity and high nitrogen oxide gas emissions in subtropical forest soils in China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 1670–1683 (2014).

Stange, F. et al. A process-oriented model of N2O and NO emissions from forest soils 2. Sensitivity analysis and validation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 4385–4398 (2000).

Karpatne, A. et al. Theory-guided data science: a new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 29, 2318–2331 (2017).

Reichstein, M. et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 566, 195–204 (2019).

Razavi, S. et al. Coevolution of machine learning and process-based modelling to revolutionize Earth and environmental sciences: a perspective. Hydrol. Process 36, e14596 (2022).

Bennett, A. & Nijssen, B. Deep learned process parameterizations provide better representations of turbulent heat fluxes in hydrologic models. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029328 (2021).

Xie, W. et al. Interpretable framework of physics-guided neural network with attention mechanism: simulating paddy field water temperature variations. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR030493 (2022).

Van der Gon, H. D. & Bleeker, A. Indirect N2O emission due to atmospheric N deposition for the Netherlands. Atmos. Environ. 39, 5827–5838 (2005).

Butterbach-Bahl, K., Nemitz, E. & Zaehle, S. Nitrogen as a threat to the European greenhouse balance. The European Nitrogen Assessment: Sources, Effects and Policy Perspectives Ch. 19 (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Liu, L. & Greaver, T. L. A review of nitrogen enrichment effects on three biogenic GHGs: the CO2 sink may be largely offset by stimulated N2O and CH4 emission. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1103–1117 (2009).

Deng, L. et al. Soil GHG fluxes are altered by N deposition: new data indicate lower N stimulation of the N2O flux and greater stimulation of the calculated C pools. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 2613–2629 (2020).

Huscroft, J., Gleeson, T., Hartmann, J. & Börker, J. Compiling and mapping global permeability of the unconsolidated and consolidated Earth: GLobal HYdrogeology MaPS 2.0 (GLHYMPS 2.0). Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1897–1904 (2018).

Bai, E., Houlton, B. Z. & Wang, Y. P. Isotopic identification of nitrogen hotspots across natural terrestrial ecosystems. Biogeosciences 9, 3287–3304 (2012).

Zhang, J., Müller, C. & Cai, Z. Heterotrophic nitrification of organic N and its contribution to nitrous oxide emissions in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 84, 199–209 (2015).

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006).

Mahecha, M. D. et al. Global convergence in the temperature sensitivity of respiration at ecosystem level. Science 329, 838–840 (2010).

Morgan Ernest, S. K. & Brown, J. H. Homeostasis and compensation: the role of species and resources in ecosystem stability. Ecology 82, 2118–2132 (2001).

Briones, A. & Raskin, L. Diversity and dynamics of microbial communities in engineered environments and their implications for process stability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14, 270–276 (2003).

Ågren, G. I. & Bosatta, E. Nitrogen saturation of terrestrial ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 54, 185–197 (1988).

Aber, J. D. et al. Nitrogen saturation in temperate forest ecosystems: hypotheses revisited. BioScience 48, 921–934 (1998).

Field, C. B., Chapin, F. S., Matson, P. A. & Mooney, H. A. Responses of terrestrial ecosystems to the changing atmosphere: a resource-based approach. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23, 201–235 (1992).

Eickenscheidt, N., Brumme, R. & Veldkamp, E. Direct contribution of nitrogen deposition to nitrous oxide emissions in a temperate beech and spruce forest—a 15N tracer study. Biogeosciences 8, 621–635 (2011).

Vermoesen, A., de Groot, C.-J., Nollet, L., Boeckx, P. & Van Cleemput, O. Effect of ammonium and nitrate application on the NO and N2O emission out of different soils. Plant Soil 181, 153–162 (1996).

Holland, E. et al. in Standard Soil Methods for Long-Term Ecological Research (eds Robertson, G. P., Coleman, D. C., Bledsoe, C. S. & Sollins, P.) 185–201 (Oxford University Press, 1999).

GetData Graph digitizer version 2.26. Available at: www.getdata-graph-digitizer.com (2013).

Lovett, G. M. & Goodale, C. L. A new conceptual model of nitrogen saturation based on experimental nitrogen addition to an oak forest. Ecosystems 14, 615–631 (2011).

Wessel, W. W., Boxman, A. W., Cerli, C., van Loon, E. E. & Tietema, A. Long-term stabilization of 15N-labeled experimental NH4+ deposition in a temperate forest under high N deposition. Sci. Total Environ. 768, 144356 (2021).

Corre, M. D., Beese, F. O. & Brumme, R. Soil nitrogen cycle in high nitrogen deposition forest: changes under nitrogen saturation and liming. Ecol. Appl 13, 287–298 (2003).

Van Breemen, N. V. et al. Where did all the nitrogen go? Fate of nitrogen inputs to large watersheds in the northeastern USA. Biogeochemistry 57, 267–293 (2002).

Dise, N. & Wright, R. Nitrogen leaching from European forests in relation to nitrogen deposition. For. Ecol. Manag. 71, 153–161 (1995).

Davidson, E. A., Keller, M., Erickson, H. E., Verchot, L. V. & Veldkamp, E. Testing a conceptual model of soil emissions of nitrous and nitric oxides. Bioscience 50, 667–680 (2000).

ŠImek, M. & Cooper, J. The influence of soil pH on denitrification: progress towards the understanding of this interaction over the last 50 years. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 53, 345–354 (2002).

Saggar, S. et al. Denitrification and N2O: N2 production in temperate grasslands: Processes, measurements, modelling and mitigating negative impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 465, 173–195 (2013).

Levin, S. A. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology: the Robert H. MacArthur award lecture. Ecology 73, 1943–1967 (1992).

Bouwman, A. F., Boumans, L. J. M. & Batjes, N. H. Emissions of N2O and NO from fertilized fields: Summary of available measurement data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 6-1–6-13 (2002).

McSwiney, C. P. & Robertson, G. P. Nonlinear response of N2O flux to incremental fertilizer addition in a continuous maize (Zea mays L.) cropping system. Glob. Chang. Biol. 11, 1712–1719 (2005).

Hoben, J., Gehl, R., Millar, N., Grace, P. & Robertson, G. Nonlinear nitrous oxide (N2O) response to nitrogen fertilizer in on-farm corn crops of the US Midwest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 17, 1140–1152 (2011).

Lu, M. et al. Contrasting response of soil N2O release to ammonium, nitrate, and urea addition rates is determined by substrate availability and microbial community abundance and composition. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 109, 103393 (2022).

Shcherbak, I., Millar, N. & Robertson, G. P. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 9199–9204 (2014).

Davison, A. C. & Hinkley, D. V. in Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics Ch. 4, (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Grömping, U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: the package relaimpo. J. Stat. Softw. 17, 1–27 (2006).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020).

ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10 (Redlands, CA, 2011).

Ord, J. K. & Getis, A. Local spatial autocorrelation statistics: distributional issues and an application. Geogr. Anal. 27, 286–306 (1995).

Cen, X. et al. Data and Code for: nitrogen deposition contributed to a global increase in nitrous oxide emissions from forest soils. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11077130 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Annual dynamics of global land cover and its long-term changes from 1982 to 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1217–1243 (2020).

Hansen, M. C., Stehman, S. V. & Potapov, P. V. Quantification of global gross forest cover loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8650–8655 (2010).

Xu, X. F., Tian, H. Q. & Hui, D. F. Convergence in the relationship of CO2 and N2O exchanges between soil and atmosphere within terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 14, 1651–1660 (2008).

Zhuang, Q. L., Lu, Y. Y. & Chen, M. An inventory of global N2O emissions from the soils of natural terrestrial ecosystems. Atmos. Environ. 47, 66–75 (2012).

Potter, C. S., Matson, P. A., Vitousek, P. M. & Davidson, E. A. Process modeling of controls on nitrogen trace gas emissions from soils worldwide. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 101, 1361–1377 (1996).

Tian, H. et al. Global methane and nitrous oxide emissions from terrestrial ecosystems due to multiple environmental changes. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 1, 1–20 (2015).

Zhang, K. R. et al. Spatial and temporal variations of N2O emissions from global forest and grassland ecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 266, 129–139 (2019).

Werner, C., Butterbach-Bahl, K., Haas, E., Hickler, T. & Kiese, R. A global inventory of N2O emissions from tropical rainforest soils using a detailed biogeochemical model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB3010 (2007).

Tian, H. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of CH4 and N2O fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems of North America during 1979-2008: application of a global biogeochemistry model. Biogeosciences 7, 2673–2694 (2010).

Lu, C. et al. Century-long changes and drivers of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions across the contiguous United States. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 2505–2524 (2022).

Cai, Z. C. Greenhouse gas budget for terrestrial ecosystems in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 55, 173–182 (2012).

Xu-Ri et al. Estimating N2O emissions from soils under natural vegetation in China. Plant Soil 434, 271–287 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all the researchers who spent time and efforts on manipulative experiments and observations, and made the data available to others. This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFF080210102, 2023YFF1305900), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32301362, 42141004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.H. and X.K. designed the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript; X.C. carried out formal analysis, wrote the initial draft, reviewed and edited the manuscript; C.M., X.Z., J.Z., and G.Y. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rossella Guerrieri, Clare Davis and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cen, X., Müller, C., Kang, X. et al. Nitrogen deposition contributed to a global increase in nitrous oxide emissions from forest soils. Commun Earth Environ 5, 532 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01647-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01647-6

This article is cited by

-

Both biotic and abiotic soil N₂O productions are lower under organic N than inorganic N deposition in a Moso bamboo forest

Biology and Fertility of Soils (2025)