Abstract

Some communities endure environmental hazards from abandoned mines and job loss from the energy transition away from coal. Recent US legislation provides a historic appropriation for abandoned mine hazards like the acidic water that often drains from them. Who the investment will benefit and what it will accomplish is unclear. Here we provide answers for the case of abandoned mine drainage in Pennsylvania. We find that communities most exposed to mine drainage have incomes 30 percent below that of unaffected communities and are twice as vulnerable to the energy transition. Within affected communities, exposure is associated with a greater urban, non-white, renter population. Analytical modeling using data from past treatment efforts shows that they have been relatively cost effective, protecting streams for about $5700 per kilometer per year. Federal appropriations for Pennsylvania could address all impaired streams for 25 years but would leave insufficient funding for other abandoned mine hazards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States is one of several countries transitioning away from coal1, a transition that will reduce employment and tax revenue in producing communities despite hopes that so-called green industries and jobs will fill the gap2,3,4. Some have argued for compensating producing communities for policy-driven industry decline, both to make the energy transition just and to garner political support to make it happen at all5,6,7. Proposals describe diverse forms of compensation, including retraining displaced workers, providing economic development grants, and funding cleanup of legacy pollution8,9. The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) makes addressing legacy pollution the largest US federal investment directed towards fossil fuel communities in decades, appropriating $16 billion to cleanup abandoned wells and mines10, whose hazards can stymie local economies11,12,13.

At face value, investment in cleanup in fossil fuel communities rights the wrongs of the past and prepares vulnerable communities for a greener and more prosperous 21st century despite energy transition headwinds. Who the investment will benefit and what it will accomplish, however, is unclear. Are the communities who suffer most of the legacy cost of fossil fuel extraction actually more vulnerable to the energy transition? And does evidence from similar past investments suggest that the IIJA appropriation is likely to address most remaining legacy problems?

We answer these questions in the case of abandoned mine drainage (AMD), arguably the most far-reaching effect of abandoned mines. It is often acidic and metal-laden and can turn a stream orange, kill its fish, and sicken people if they ingest it. AMD exposure in humans has been associated with skin lesions, cancer, and multiple organ failure. In addition, heavy metals can bioaccumulate in organisms and biomagnify as they work their way up the food chain14.

Estimates suggest that drainage from coal mines impairs at least 10,000 km of streams in Appalachian states alone15,16. Much of the problem reflects the inadequacy of prior policy, though mining under current regulations can still affect stream health17. Roughly 200 years of coal mining occurred in Appalachia before passage of the 1977 federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, which established standards for operating and reclaiming active mines and also attempted to address hazards from the many mines abandoned before the Act18.

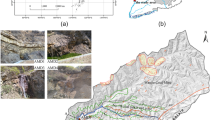

Our study focuses on Pennsylvania, which has the most abandoned mine liabilities in the U.S. and is also estimated to receive one-third of all the abandoned mine land funding from the IIJA19,20. The state also has a long history of addressing abandoned mine drainage and rich data on the efforts and their effects. Despite the work, more than 8800 kilometers of impaired streams remain scattered across much of the state as Fig. 1 shows21. The most common approach to addressing mine drainage is to build systems of shallow ponds or wetlands designed to reduce the acidity of drainage and capture metals as they precipitate out22. More than 300 such systems have been built in the state using a mix of state and federal money. Their construction, monitoring, and maintenance reflects past and ongoing work by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and organizations such as local watershed groups21. As a result of the monitoring, data on inflow and outflow water quality exists for most of them. In addition, the DEP has identified stream segments impaired by abandoned mine drainage.

Calculating the proportion of streams impaired by abandoned mine drainage and merging with other data allows us to characterize communities most burdened by the drainage and who would therefore benefit from investments in cleanup. To assess the likely effect of new investments, we study the effects of existing treatment systems. Inflow and outflow water quality readings for each system and the National Hydrography Dataset allow us to calculate whether a given stream segment would likely be impaired in scenarios with and without the treatment provided by upstream systems. Thus, our conclusions about downstream impairment status do not presume that upstream systems actually work but are based on empirically observed water quality at system inflow and outflow points. We then combine the kilometers of stream protected from impairment because of upstream treatment with actual costs of system construction, permitting calculation of the cost per kilometer protected. The per kilometer cost, in turn, permits calculating the total cost of protecting all of the state’s impaired streams and whether currently appropriated federal funds meet the need.

Results and Discussion

AMD communities

About 2.4 million people in Pennsylvania live in a community (Census tract) with a stream impaired by abandoned mine drainage (AMD)23. Among affected communities, those in the top quartile for AMD exposure have at least half of their streams impaired and are home to more than half a million people. As AMD exposure increases, income and housing values fall (Fig. 2). As a result, the differences between unaffected communities and those most affected are large: communities in the top quartile for exposure have an average median income nearly 30 percent below that of unaffected communities, and housing values about 50 percent lower.

Source: Median household income, housing value, percent renters, and percent non-white: 2018–2022 American Community Survey (Census Bureau), AMD-impaired stream designations: PA Department of Environmental Protection. The values presented for median income and housing value are from averaging across the tracts in each group. Dots represent means; the spread of the vertical bars represent the 95 percent confidence interval.

The income and housing value differences between unaffected and affected communities may primarily reflect regional economic differences. The southeastern part of the state, which accounts for many of the unaffected communities, lacks a history of mining or fossil fuel production and has a larger and more diversified economy that is integrated with coastal cities. Within affected communities, the lower incomes and housing values could reflect the effects of AMD on local economies, including depression of local housing values, which in turn draw lower-income residents looking for more affordable housing.

The broad regional differences mentioned above help explain the relationship between AMD exposure and vulnerability to the energy transition (Fig. 3, top right), where unaffected communities have the lowest vulnerability to the energy transition, and all affected communities have a similar vulnerability. The pattern is expected because abandoned mine drainage and fossil fuel production occurs outside the population dense Southeastern part of the state.

Source: Percent renters: 2018–2022 American Community Survey (Census Bureau); Vulnerability score36; Environmental justice index: Environmental Protection Agency & Center for Disease Control. Dots represent means; the spread of the vertical bars represent the 95 percent confidence interval.

The five other characteristics show a U-shaped relationship with AMD exposure, with both unaffected and high-exposure communities having high characteristic values and those in between having lower values. The high percent of the population in urban areas among unaffected communities reflects, in part, the regional differences mentioned above. Among AMD-affected communities, the positive relationships between urbanization and AMD-exposure might reflect the smaller area covered by urbanized Census tracts. Because tracts are delineated to contain roughly the same population, urban tracts encompass less area than rural tracts. Because urban tracts may have only one river or stream flowing through them, it is easier for them to have a high exposure metric since impairment of that one stream would give it 100 percent exposure.

The U-shaped relationship with urbanization helps explain the U-shaped relationship between AMD exposure and the percent of renters, the percent non-white, and environmental justice scores. In general, urban areas tend to have a greater percentage of renters and non-whites24. It is also unsurprising that urban areas would have higher values for both environmental justice variables since these incorporate characteristics like proximity to traffic and air pollution. The relationships could also reflect causal links, such as AMD-exposure depressing housing values, which draws low-income residents who tend to be renters.

Cost-effectiveness and funding needed

For the 265 systems studied, observed outflow water quality is substantially better than inflow water quality, indicating that the systems are on average improving the quality of mine drainage before it enters nearby streams23. Inflow water has an average pH of 4.3, roughly the acidity of tomato juice (Table 1). In contrast, outflow pH is near 6, a difference that is both practically and statistically significant. Likewise, the concentrations of manganese (Mn), aluminum (Al), and total iron (Fe) all fall considerably. For example, the concentration of iron falls from about 24 mg/L to 5 mg/L, which is consistent with the expected effectiveness of a common passive system (anaerobic wetland)25. The average values mask some heterogeneity of treatment effectiveness across systems. The system at the 25th percentile of pH treatment effectiveness increases it by 0.5 while the system at the 75th percentile increases it by 2.7.

Turning to effects downstream, we estimate the kilometers of stream protected using two methods described in “Kilometers protected”. The first estimation method gives an estimate slightly higher than the second method (1601 km vs 1486 km). The average of the two, which is our main estimate, indicates that the systems protect 1543 kilometers of stream from impairment by AMD (90% CI 1456−1627). The present value lifetime cost of the systems, including operation and maintenance costs, implies a cost per year of $5720 per kilometer (90% CI $5368–$6168).

Our estimates indicate that a total of 10,381 kilometers of streams need protection from AMD. This includes 1543 kilometers of stream protected by existing (and increasingly old) systems and 8838 kilometers of streams still impaired. The cost-effectiveness of prior systems therefore suggests that 25 years of protecting all streams requires about $1.5 billion (=10,381 km ⋅ 5720/km/year ⋅ 25 years). In addition, Pennsylvania has about $3.9 billion in non-AMD abandoned mine liabilities19, giving a total financial need of about $5.4 billion.

We estimate that the present value of federal funds coming to Pennsylvania through the Abandoned Mine Land Fund and the IIJA appropriation is $2.5 billion. Already-approved federal funds are therefore sufficient to protect all streams from AMD impairment for 25 years but not to also cover other abandoned mine hazards. In this case, the funds are less than half of the amount needed.

Well-targeted and effective compensation?

Funding from the IIJA for addressing abandoned mine drainage targets communities that already lag economically and, looking forward, are more vulnerable to the country’s transition away from coal. Their considerably lower income and housing values indicate small tax bases from which schools and local governments can fund public services. Additional mine or power plant closures would further shrink the tax base and exacerbate already large economic disparities. More generally, various levels of government in Pennsylvania take in $4.4 billion in fossil fuel revenues annually, the third highest of any state3. This highlights the value of the federal government’s role in leveling the distribution of transition costs across states with varied dependence on fossil fuels.

Some argue that countries with corporatist institutions or strong welfare states are more likely to adopt enduring compensatory policies in the face of the energy transition. As such, the US is unlikely to pursue a just transition despite calls for compensation26. The IIJA funding for environmental remediation can easily be framed as compensation, and similar initiatives are part of transition policies in Germany and Spain27,28.The US, however, does appear unique in that remediation is such a large part of the federal funding directed towards coal communities, which likely reflects the scale of mining in the US prior to modern regulations that limited environmental damage.

Although not typically framed as labor or economic development policy, remediation can further similar goals. It can plausibly employ former miners and bolster regional economies by making more land available for alternative uses and by increasing environmental amenities that help regions attract and retain workers. In that sense, it can spur economic activity in the short term and create conditions for broader growth in the long term. The employment and growth effects of remediation merit empirical study, which can exploit the burst of funding from IIJA that began in 2022 and will continue for more than a decade. Such research could help quantify how much the investments offset the economic headwinds that receiving communities are likely to face in coming years relative to other areas of the state.

AMD cleanup as cost-effective environmental policy

In addition to making the energy transition more just, our findings indicate that investments to treat abandoned mine drainage in Pennsylvania over thirty years have generally been cost-effective and have likely created more benefits than costs. A recent study of Clean Water Act grants to municipal wastewater treatment plants highlights a lack of ex-post estimates of the cost of making a river-kilometer fishable29. In 2020 dollars and on a per kilometer basis, the study finds an annual cost of about $1 million per kilometer made fishable. The fishable concept is similar to the biological impairment concept used by the PA Department of Environmental Protection when designating a stream’s impairment status. The waterways in the Clean Water Act study are likely larger on average than those in our data. That said, their waterways would have to be 175 times larger to have the same cost effectiveness ($1,000,000/$5700), suggesting that AMD treatment systems are relatively cost-effective investments in surface water quality.

Estimates of the value of surface water quality improvement also suggest that the treatment systems create benefits that exceed their costs. The same study used housing values to measure benefits and estimated about $5 million in benefits per kilometer of river made fishable29. By comparison, we estimate the 25 year cost of protection from impairment to be about $143,000 per kilometer. A more dated but arguably more applicable estimate of benefits comes from asking residents of Western Pennsylvania how much they would be willing to pay to restore rivers affected by abandoned mine drainage30. The findings suggest that households within 70 kilometers of the Conemaugh River would be willing to pay about $700 to take it from being severly polluted, where fish are unable to survive, to being unpolluted, where fish can thrive. Taking the population of Cambria County alone, which is in the relevant distance range, gives a total benefit of around $39 million. By comparison, the estimated cost of restoring the 112 kilometers of the Conemaugh River for 25 years is about $16 million (=5700 per km ⋅ 112 km ⋅ 25 years).

Heterogeneity and generalizability

Our findings reflect each system’s average treatment effectiveness, which varies as shown in Table 1. A detailed accounting of heterogeneity is outside the scope of our study, but one study examined 18 systems that the PA Department of Environmental Protection had deemed to be failing. It found that the reason for poor performance varied, including improper design, problems during construction, and insufficient maintenance31. Our analysis relies on ex-post data; a fruitful avenue of future research may be to document how design estimates relate to actual system performance.

The heterogeneity in effectiveness raises the broader question of whether systems built elsewhere or in coming years would have a similar cost-effectiveness. We first note that our analysis covers passive systems. Active systems are more costly to build and maintain but also treat more drainage and therefore have greater effects downstream. As a result, their cost effectiveness could be lower or higher. Because passive treatment systems often require considerable space for ponds and wetlands32, they may cost more to build in areas with limited flat land as in parts of West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky.

Looking forward, cost effectiveness could improve with future systems. The funding available for AMD treatment in Pennsylvania and other historic coal-producing states far exceeds amounts from prior years. The steady and large funding provided by IIJA will enable greater economies of scale and learning by doing and innovation. As more organizations design and build more systems, the opportunity for learning by doing grows, with learning shared through events like Pennsylvania’s annual Abandoned Mine Reclamation Conference. The scale of funding also increases incentives to innovate in system design and construction because the innovator can expect to apply the innovation to a larger number of future projects. We also note that the Stream Act, passed at the end of 2022, allows states to put up to 30 percent of IIJA funding in a set-aside account for long-term AMD treatment33. Set-aside funds allow states to shift funding over time, for example, setting aside money when organizational capacity cannot absorb it and using it when capacity has grown.

Methods

Identifying and characterizing AMD-affected communities

We measure AMD exposure by calculating the percentage of a community’s streams that are impaired by abandoned mine drainage according to the most recent integrated water quality report by the PA Department of Environmental Protection. See Supplementary Notes 4 and 5 and Fig. 2 for details. We create five groupings of communities (Census tracts), grouping those without AMD-impaired streams and then breaking all other communities into quartiles based on the percent of streams impaired. The bottom quartile has less than 7 percent of its streams impaired, and the top quartile has 51 percent or more impaired.

We use tract-level demographic and economic variables from the five-year estimate (2018-2022) from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (see SI Notes 1). To capture other sources of environmental burden, we use tract-level environmental justice (EJ) indices from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Center for Disease Control (CDC). The EPA calculates its indices as the product of a demographic index and an environmental indicator. Since we look at the non-white population separately, we use the EPA demographic index that is the average of numerous percentages: low-income, limited English, less than high school education, unemployed, and low life expectancy. To have one EPA EJ index, we average the 13 different indicators provided by the EPA, which covers wastewater discharge, underground storage tanks, hazardous waste proximity, risk-management-plan (RMP) facility proximity, superfund proximity, lead paint indicator, traffic proximity, toxic releases to air, air toxics respiratory hazard index, air toxics cancer risk, diesel PM, ozone, and PM 2.534.

As a complementary environmental justice measure, we use the CDC index that corresponds to environmental burden35. It is the sum of 17 different indicators: impaired watersheds, airport proximity, road proximity, railway proximity, walkability, proximity to parks, pre-1960 houses, lead mines, risk-management-plan (RMP) facility proximity, treatment-storage-and-disposal (TSD) site proximity, toxic-realease-inventory proximity, national-priority-list proximity, cancer risk, ambient concentrations of diesel particulate matter (PM) per m3, mean days above regulatory PM 2.5 exposure, ozone exposure, and coal mine proximity.

Lastly, we measure vulnerability to the energy transition using an index calculated based on county-level scores using indicators such as natural gas production in the county, employment in the energy sectors, energy production facilities, and other variables36. We use the weighted vulnerability index, which is adjusted based on the carbon intensity of the county’s energy production (coal, oil, and natural gas).

Kilometers protected

We use two complementary methods to estimate the kilometers of stream protected by treatment systems in our data. Both methods consider all stream segments with at least one treatment system within 80 kilometers (50 miles) upstream. The range accomodates the potentially far reaching effects of drainage. The most relevant empirical study of downstream effects found water quality improvements at the furthest distance measured, which was about 40 km37. We double this distance and note that expanding it further cannot decrease our estimate of cost effectiveness. At worst, doing so would add no new kilometers of stream protected.

Both methods rely on basic hydrological modeling concepts to estimate how solutes from upstream mine drainage affect solute concentrations in the receiving stream segment and ones further downstream. Constant mine drainage entering a stream brings solutes that the current carries downstream (advection) and that disperse as they move. Moving downstream, new inflows with lower concentrations of the solute cause further dilution38. Opportunities for solutes to become trapped (storage) would also reduce the overall solute concentration, which we do not model. This makes our estimates less conservative for alluvial streams where some storage might occur. Our calculations also implicitly assume conservative transport of solutes, with negligible reductions from geochemical reactions. Although our data contain measures of suspended solids, we do not include it in our downstream impairment analysis because it is not a solute and would therefore settle with transport.

Method 1 calculates downstream values of four water quality measures for each stream segment with and without mine drainage treatment by upstream systems (see Supplementary Note 3). Calculating water quality with and without treatment is possible because of measurements at each system’s inflow and outflow points, with the outflow measurement reflecting the treatment scenario and the inflow measurement reflecting the no-treatment scenario. For each water quality measure (e.g. pH), we use the average inflow or outflow pollutant concentrations based on all measurements over the life of the system (see Supplementary Note 2). Our analysis is therefore based on the average performance of each system. System performance can differ in extremely dry or wet conditions.

For a given stream segment i, we calculate the load of a particular pollutant from upstream mine drainage with systems, multiplying the drainage (liters per minute) by the outflow pollution concentration (milligrams per liter) and summing across all upstream systems.

where s ∈ S(i) refers to a drainage treated by systems upstream of segment i and \(Co{n}_{s(i)}^{T = 1}\)) indicates the treatment scenario concentration, meaning a concentration at a system’s outflow instead of its inflow. We calculate the pollutant load without treatment in the same way but using each system’s inflow pollutant concentration (\(Co{n}_{s(i)}^{T = 0}\)).

The load from system outflows (or inflows in the case of no treatment) are then added to the stream segment’s baseload apart from the drainage associated with upstream systems: Baseloadi = Flowi ⋅ Coni. The two loads are then added and divided by the segment’s total flow (baseline flow plus drainage) to give the concentration of the particular pollutant in segment i in the treatment and no-treatment scenarios:

and

We focus upon the resulting concentrations in the mixture of the baseline flow and the drainage because our goal is to estimate the effect of systems on streams, not on whether the system outflow itself is meeting water quality standards. Related, calculating concentrations for each segment does not duplicate loadings. Instead, the per segment calculation allows the same upstream drainage and associated load to have different effects on pollution concentrations in downstream segments with different flows.

We consider the four water pollutants routinely measured for each treatment system and for which there are state or national effluent standards: pH, total iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and aluminium (Al). For each pollutant, we determine if the segment is impaired in each scenario by comparing the segment’s estimated concentration with the threshold used by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection for biological restoration39. These are available for three of the four pollutants. For manganese, we use the federal EPA effluent limitations for coal mining operations40. If the concentration violates the threshold for any pollutant, we label the segment as impaired. The thresholds are below 6 for pH, above 1.5 mg/L for Fe, above 2.0 mg/L for Mn, and above 0.5 mg/L for Al.

The kilometers of stream impaired under the no-treatment scenario is therefore calculated as:

where I is the set of all stream segments with at least one treatment system within 80 kilometers upstream, and \({\mathbb{1}}\) is an indicator function that equals one if the condition is true and zero if it is false. Note, for pH we use the log of the hydrogen ion concentration and compare it to the pH threshold. The difference in kilometers impaired in the no-treatment and treatment scenarios, KmT=0 − KmT=1, gives the kilometers protected from impairment by the systems.

Method 2 draws from observation of a segment’s actual water quality as captured by assessments by the PA Department of Environmental Protection and published in its 2022 Water Quality Report. The Report summarizes the DEP’s ongoing attempts to identify all impaired segments in the state and the causes of impairment. We take all segments impaired according to our calculation in the no-treatment scenario and compare them to the impaired segments in the Report. Method 2 defines the kilometers protected by treatment systems as the total length of segments impaired in the no-treatment scenario of Method 1 but not listed as impaired by abandoned mine drainage in the Water Quality Report. See Supplementary Note 4 for details on construction of the impaired list.

An advantage of Method 2 is that it incorporates information about a segment’s actual water quality. This is because the DEP assessments involve direct measurement of pH and other aspects of water chemistry, and it incorporates biological indicators of water quality. Yet, it also is imperfect. It would overstate the kilometers impaired with treatment if the DEP’s assessment of the segment is too dated to reflect the effect of the systems. On the other hand, it would understate impaired kilometers with treatment if the DEP has never assessed whether a particular segment is impaired, thereby ommitting it from the impaired list even though it is in fact impaired.

Because Methods 1 and 2 likely have different errors that are not necessarily in the same direction, our preferred estimate of the kilometers protected from AMD by treatment systems is the average of the two. To be clear, this estimate is how many kilometers are kept from impairment due specifically to abandoned mine drainage, not from any cause. Because of other impairment sources such as agricultural runoff, some streams will be impaired regardless of treatment.

To measure uncertainty around our estimate of kilometers protected, we calculate a bootstrapped percentile confidence interval using the adjusted version of the Efron percentile method41. The approach involves randomly selecting with replacement a large number of samples of stream segments (1000 samples in our case). For each sample of segments, we calculate the kilometers protected and subtract from it the original sample estimate. After sorting the differences across all samples and taking the 95th and 5th percentiles, we calculate the 90 percent confidence interval as the original estimate less the 95th percentile (the lower bound) and the original estimate less the 5th percentile (the upper bound).

Cost

Project documents available through Datashed provide the initial cost of all but thirteen systems. For the thirteen systems missing cost values, we impute initial cost by multiplying the sample average initial cost per liter with the flow treated by each system. Our interest is in the present value of the total cost of treatment over the life of the system, which can vary but is often assumed to be roughly 25 years25,42,43. We draw from a report of the findings of a working group of watershed restoration experts in Pennsylvania regarding long-term system costs43. The group estimated that annual operation, maintenance, and reconstruction costs are about 4 percent of the intial system cost. We therefore calculate the cost of 25 years of treatment as the sum of the inital costs and the present value of 25 years of additional annual costs equal to four percent of initial costs. For the discount rate, we use the standard consumption-based discount rate of 3 percent44.

The estimated cost per year per kilometer protected from abandoned mine drainage is then the lifetime cost across all sample systems divided by the product of the total kilometers protected and the average system lifetime (assumed to be 25 years). We calculate confidence intervals for cost in the same was as for kilometers of stream protected. This is made possible by allocating each system’s cost equally among all sample segments within 80 km downstream. When randomly drawing samples of segments, we then calculate the total cost by summing the allocated cost across all sampled segments.

Funding needed and available

To estimate the funding needed to address all impaired streams, we multiply our estimated cost per kilometer by the kilometers currently impaired as reported by the PA Department of Environmental Protection in its 2022 Integrated Water Quality Report and the kilometers protected from impairment by current systems. We include currently protected kilometers because the average existing system was built in 2003 and therefore approaching the end of its expected life. Our cost estimate is too high to the extent that system life is longer than expected or that reconstruction is less costly than initial construction.

Our estimate of funding needed assumes that past costs and system performance apply to remaining untreated drainage. We might expect real costs to change over time with changes in the broader economy or treatment technology. Likewise, the effect of treatment might change if remaining drainage is more or less polluted than drainage already under treatment. In Supplementary Discussion 1, we explore both possibilities by looking for a trend in system initial costs per gallon or in inflow pollution concentrations (SI Figs. 2 and 3). In both cases, we find no clear trend over time, thereby increasing our confidence that our cost per kilometer protected is informative for the funding needed to address remaining drainage. We note, however, that studies have found that mine drainage acidity and concentrations of Fe can fall over time45,46. All else equal, a trend of improving inflow water quality would lower long-term treatment costs as fewer inputs (e.g. limestone) or maintenance (e.g. dredging of ponds) is needed.

For the money available to address mine drainage, we sum money from the state’s existing set-aside fund and the expected disbursements from the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) fund and from the Treasury appropriation from the IIJA. The annual evaluation of the state’s abandoned mine land program reports $55.1 million in the state’s set-aside account47. The IIJA reauthorized the fee on coal, which funds the AML fund, until 203448. We assume that annual disbursements decline over time in line with coal production as projected by the U.S. Energy Information Administration in its 2023 Annual Energy Outlook. Specifically, we look at the change in production from 2021 to 2034 and assume that AML fund disbursements fall by the same percentage and then interpolate values in between. For the Treasury appropriation, we assume that the 2022 disbursement to Pennsylvania is constant over the appropriation’s 15 year life. Because the appropriation is not adjusted for inflation, we use nominal discount rate of 5 percent instead of the 3 percent real discount rate previously used. We do the same for disbursements from the AML fund, which are based on a fee applied to the volume, not the value, of coal production49.

Data availability

All of the raw data used in this study are publicly available: Treatment system data(www.datashed.org/projects), American Community Survey data (www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html), EPA environmental justice data (www.epa.gov/ejscreen/download-ejscreen-data), CDC environmental justice data (www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/eji/index.html), PA DEP impaired streams list (https://gis.dep.pa.gov/IRViewer2022/). The compiled datasets for the tables, figures, and results are also publicly available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/DI47EN23.

Code availability

All code used to generate the tables, figures, and estimates are publicly available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/DI47EN23.

References

Steckel, J. C. & Jakob, M. To end coal, adapt to regional realities. Nature 607, 29–31 (2022).

Weber, J. G. How should we think about environmental policy and jobs? An analogy with trade policy and an illustration from us coal mining. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 14, 44–66 (2020).

Raimi, D. et al. The fiscal implications of the us transition away from fossil fuels. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 17, 295–315 (2023).

Lim, J., Aklin, M. & Frank, M. R. Location is a major barrier for transferring us fossil fuel employment to green jobs. Nat. Commun. 14, 5711 (2023).

Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 5, 569–577 (2020).

Jakob, M. et al. The future of coal in a carbon-constrained climate. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 704–707 (2020).

Konisky, D. M. & Carley, S. What we can learn from the green new deal about the importance of equity in national climate policy. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 40, 996–1002 (2021).

Morris, A. Build a better future for coal workers and their communities. Clim. Energ. Econ. Discuss. Paper, Brookings Institution, Washington DC (2016).

Lawhorn, J. M. The power initiative: energy transition as economic development. Congressional Res. Serv. (2022).

U.S. Department of the Interior. Bipartisan infrastructure deal will clean up legacy pollution, protect public health. www.doi.gov/pressreleases/bipartisan-infrastructure-deal-will-clean-legacy-pollution-protect-public-health (2022).

Williamson, J. M., Thurston, H. W. & Heberling, M. T. Valuing acid mine drainage remediation in west virginia: a hedonic modeling approach. Ann. Reg. Sci. 42, 987–999 (2008).

Fitzpatrick, L. G. & Parmeter, C. F. Data-driven estimation of treatment buffers in hedonic analysis: An examination of surface coal mines. Land Econ. 97, 528–547 (2021).

Harleman, M., Weber, J. G. & Berkowitz, D. Environmental hazards and local investment: a half-century of evidence from abandoned oil and gas wells. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Economists 9, 721–753 (2022).

Masindi, V. et al. Challenges and avenues for acid mine drainage treatment, beneficiation, and valorisation in circular economy: A review. Ecol. Eng. 183, 106740 (2022).

Herlihy, A. T., Kaufmann, P. R., Mitch, M. E. & Brown, D. D. Regional estimates of acid mine drainage impact on streams in the mid-atlantic and southeastern united states. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 50, 91–107 (1990).

Kruse Daniels, N., LaBar, J. A. & McDonald, L. M. Acid mine drainage in appalachia: sources, legacy, and treatment. In Appalachia’s Coal-Mined Landscapes, 193–216 (Springer, 2021).

Giam, X., Olden, J. D. & Simberloff, D. Impact of coal mining on stream biodiversity in the us and its regulatory implications. Nat. Sustain. 1, 176–183 (2018).

Zipper, C. E., Adams, M. B. & Skousen, J. The appalachian coalfield in historical context. In Appalachia’s Coal-Mined Landscapes, 1–26 (Springer, 2021).

Larson, L. N. The abandoned mine reclamation fund: Reauthorization issues in the 116th congress. Congress. Res. Serv. (2020).

Dixon, E. Coal mine cleanup in the bipartisan infrastructure law, explained ohiorivervalleyinstitute.org/iija-aml-explainer (2022).

Lenahan, G. Acid mine drainage treatment facilities reversing hundreds of years of pollution to bring pennsylvania’s streams and rivers back to life www.dep.pa.gov/OurCommonWealth/pages/Article.aspx?post=92 (2022).

US Department of the Interior. Technical note 409: Passive treatment systems for acid mine drainage www.blm.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Library_BLMTechnicalNote409.pdf (2003).

Weber, J. G. & Black, K. J. Replication Data for: Treating abandoned mine drainage can protect streams cost effectively and benefit vulnerable communities https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DI47EN (2024).

Hawk, W. Expenditures of urban and rural households in 2011 www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-2/expenditures-of-urban-and-rural-households-in-2011.htm (2013).

Skousen, J. & Ziemkiewicz, P. Performance of 116 passive treatment systems for acid mine drainage. In National meeting of the American society of mining and reclamation, Breckenridge, CO (Citeseer, 2005).

Meckling, J., Lipscy, P. Y., Finnegan, J. J. & Metz, F. Why nations lead or lag in energy transitions. Science 378, 31–33 (2022).

Furnaro, A. et al. German just transition: A review of public policies to assist german coal communities in transition. https://media.rff.org/documents/21-13-Nov-22.pdf (2021).

Bolet, D., Green, F. & González-Eguino, M. How to get coal country to vote for climate policy: The effect of a “just transition agreement” on spanish election results. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 118, 1344–1359 (2023).

Keiser, D. A. & Shapiro, J. S. Consequences of the clean water act and the demand for water quality. Q. J. Econ. 134, 349–396 (2019).

Farber, S. & Griner, B. Valuing watershed quality improvements using conjoint analysis. Ecol. Econ. 34, 63–76 (2000).

Rose, A. W. An evaluation of passive treatment systems receiving oxic net acidic mine drainage. Report to PA Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation, Harrisburg, PA. 27 (2013).

Skousen, J. et al. Review of passive systems for acid mine drainage treatment. Mine Water Environ. 36, 133–153 (2017).

US Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation. Final guidance for implementation of the stream act’s long term aml reclamation fund. Tech. Rep. www.osmre.gov/sites/default/files/inline-files/FINAL-Stream-Act-Guidance.pdf. (2024).

US Environmental Protection Agency. Ejscreen technical documentation for version 2.2. www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-06/ejscreen-tech-doc-version-2-2.pdf (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry. 2022 environmental justice index. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/eji/index.html (2022).

Raimi, D., Carley, S. & Konisky, D. Mapping county-level vulnerability to the energy transition in us fossil fuel communities. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–10 (2022).

Underwood, B. E., Kruse, N. A. & Bowman, J. R. Long-term chemical and biological improvement in an acid mine drainage-impacted watershed. Environ. Monit. Assess. 186, 7539–7553 (2014).

Baker, M. A. & Webster, J. R. Conservative and reactive solute dynamics. In Methods in Stream Ecology, (eds. Lamberti, G. A. & Hauer, F. R.) 129–145 (Academic Press, 2017).

Pennsylvania DEP. (department of environmental protection) acid mine drainage set-aside program program implementation guidelines. www.depgreenport.state.pa.us/elibrary/GetDocument?docId=8133&DocName=ACID%20MINE%20DRAINAGE%20SET-ASIDE%20PROGRAM%20IMPLEMENTATION%20GUIDELINES.PDF%20 (2016).

US Environmental Protection Agency. Effluent limitations guidelines and standards (elg) database. owapps.epa.gov/elg/ (2023).

Hansen, B.Econometrics (Princeton University Press, 2022).

Ziemkiewicz, P., Skousen, J. & Simmons, J. Cost benefit analysis of passive treatment systems. In Proceedings, 22 nd West Virginia Surface Mine Drainage Task Force Symposium, 3–4 (2001).

Milavec, P. & Seibert, D. Pennsylvania’s efforts to address operations, maintenance and replacement of amd passive treatment systems. In Proceedings, National Assoc. Abandoned Mine Land Program: Reclamation 2002 in Park City, Utah (Utah Division of Oil, Gas, & Mining, 2002).

Newell, R. G., Pizer, W. A. & Prest, B. C. The shadow price of capital: Accounting for capital displacement in benefit–cost analysis. Issue Brief 22-08 22–08. https://media.rff.org/documents/IB_22-08_5B89TmJ.pdf (2023).

Burrows, J. E., Peters, S. C. & Cravotta III, C. A. Temporal geochemical variations in above-and below-drainage coal mine discharge. Appl. Geochem. 62, 84–95 (2015).

Merritt, P. & Power, C. Assessing the long-term evolution of mine water quality in abandoned underground mine workings using first-flush based models. Sci. Total Environ. 846, 157390 (2022).

US Office of Surface Mining Reclamation. 2022 Annual Evaluation Report for Pennsylvania. Tech. Rep. (2023).

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fee. Federal Registrar 87, 51904–51908 (2022).

Pennsylvania DEP. Abandoned mine land funding. www.dep.pa.gov/Business/Land/Mining/AbandonedMineReclamation/AMLProgramInformation/Pages/AMLFunding.aspx (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to John Gardner for help with NHD data and comments on the manuscript and to Camille Sicker and Ben Hedin for help with understanding abandoned mine drainage. We also thank the Center for Governance and Markets for supporting a September 2022 workshop on restoring mine-impaired watersheds, which helped inform this work. We are grateful to Madi Hamilton who performed initial data collection for Datashed systems. No sampling permissions were needed for any data used. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments that have made the manuscript clearer and better supported. Any errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Black collected and cleaned the Datashed water quality data, conducted the analysis of community characteristics, collected and organized NHD stream characteristic data, and spatially integrated Datashed systems with NHD stream characteristics. Weber performed much of the conceptualization and writing of the paper and developed and implemented methods for estimating costs per km protected and related estimates. Both authors performed background research and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Somaparna Ghosh and Martina Grecequet. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Black, K.J., Weber, J.G. Treating abandoned mine drainage can protect streams cost effectively and benefit vulnerable communities. Commun Earth Environ 5, 508 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01669-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01669-0