Abstract

Sedimentary records of Early Pleistocene (~2.6–0.8 Ma) glaciations are sparse on shelves, yet trough mouth fans on adjacent continental slopes provide a continuous record of ice-sheet and climate development throughout the Quaternary. Here, we interpret high-quality 3D seismic reflection data combined with borehole and chronostratigraphic information from a shelf-slope setting in the southwestern Barents Sea to study meltwater and sediment inputs to the deep ocean, focusing on the onset of Pleistocene glaciations. Sandy deposits were brought to the slopes of the high-latitude Bear Island Fan by a preglacial contourite-turbidite system from ⁓2.6–2.4 Ma. Muddy glacigenic debris flows document the first shelf-edge glaciation at ⁓2.4 Ma. From 1.78–0.78 Ma, muddy turbidity-current- and debris-flow-derived sediments were delivered from shelf to slope via six tunnel valleys measuring up to 12 km in width and 200 m in depth. These tunnel valleys and associated downslope deposits formed during the 41-kyr climate cycles of the Early Pleistocene, and evidence abundant channelized, meltwater discharges from these glaciations. Following the mid-Pleistocene transition to 100-kyr cycles, a change in the style of glaciation is suggested by a change in landform and facies associations consistent with a reduced meltwater contribution. This study shows that the Norwegian-Barents shelf was extensively glaciated in the Early Pleistocene, with a first shelf-edge glaciation from ~2.4 Ma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A key driver of Pleistocene climate was astronomical configuration, with obliquity (41-kyr cycles) dominating in the Early Pleistocene, and eccentricity (100-kyr cycles) and precession (23- and 19-kyr cycles) dominating in the Middle and Late Pleistocene1,2. The shift from obliquity-dominated to eccentricity-dominated cycles occurred during the mid-Pleistocene transition (1.2–0.7 Ma). Orbital forcing affected Pleistocene sedimentation3,4, in particular via extensive ice sheets that covered and eroded mid- and high-latitude shelves of both hemispheres5,6. Glaciomarine sediments have been deposited to near 30° north and south in full glacials7,8.

Similar to contemporary ice masses, the majority of ice, meltwater, and sediment discharged by these vast Pleistocene ice sheets was transported in narrow zones of increased ice flow velocity, called ice streams. Ice streams reshape subglacial surfaces through extensive deformation and erosion, often carving shelf-crossing troughs such as Bjørnøyrenna in the Barents Sea9 (Fig. 1a). Depending on their tectonic and glacial development, glaciated shelves are repeatedly eroded through glacial cycles, making them suboptimal locations for the preservation of sedimentary archives for climate and ice sheet reconstruction10. The erosional products from the shelves are, however, deposited along the adjacent slopes, together with contourites (the deposition of which is most active during deglacial and interglacial periods11). On slopes beyond ice stream grounding lines, mass flows, and megaslides build up through mouth fans12,13, such as the Bear Island Fan (Fig. 1a). As a result of this focused sediment and meltwater delivery, glaciated margins host the largest submarine slides on Earth14,15, for which contourites can act as weak layers16,17. The failed sediments forming these mass movements are mainly provided by ice streams and accumulate predominantly during glacial periods12,18.

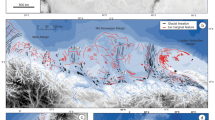

a Modeled ice-flow lines at the Last Glacial Maximum (black lines; modified after Patton et al.28). Black box shows the study area and location of (b). Borehole 7316/6-U-1 has Pleistocene glacio-fluvial channel infill52. Bs: Bellsund fan, Hs: Hornsund fan, If: Isfjorden fan, Sb: Sjubrebanken trough mouth fan, Sf: Storfjorden fan. b Study area with relevant borehole locations (white dots). The Senja Ridge (golden polygon), the extent of the 3D seismic survey (black envelope), regional seismic section (red line), seismic profiles (black lines and black numbers, with white numbers associated with the white envelope, indicate figure locations), and areal extents of Figs. 5, 6, and 7 (white stippled line) are indicated. Slope channels and glacial lineations on the present seafloor are shown as insets. Shaded relief maps from mareano.no. c Uninterpreted and interpreted seismic section across the study area, highlighting the Bear Island Fan and the shelf edge on a regional scale. The Quaternary sediments of the SW Barents Sea are thin on the shelf and thicken in the Bear Island Fan. Modified from Lasabuda et al.20. Seismic data courtesy of TGS/Spectrum.

The Arctic plays a crucial role in the Quaternary climate system, and the effects of ongoing global warming are documented and predicted to be most pronounced in the Arctic19. However, the origin and nature of the initial glacial period are not yet well studied, partly due to the hostile and remote Arctic research environment, insufficient data, and the poor preservation of glacial deposits. The aim of this contribution is, therefore, to document the initiation and style of Early Pleistocene shelf-edge glaciations in the Arctic based on integrated interpretation of extensive 3D seismic and borehole data. The study is based on a new and unique dataset, including four boreholes and 5754 km2 of high-quality 3D seismic reflection data (Fig. 1b), allowing us to reconstruct sedimentary processes from the Pliocene into the Pleistocene in high temporal and spatial resolution. Our results provide detailed observations of the natural climatic and environmental variability in the Barents Sea, focusing on meltwater and sediment input to the deep Atlantic Ocean during the onset of glaciation on the Barents Sea margin. The new paleoenvironmental reconstruction spans from the Pliocene-Pleistocene transition to the mid-Pleistocene transition and contributes to the overall understanding of the evolution of the Arctic cryosphere.

Southwestern Barents Sea and Bear Island Fan—Stratigraphy and processes

The Barents Sea was a terrestrial platform during most of the Cenozoic, with spatiotemporal changes in its paleogeography20,21, including current basement highs such as the Senja Ridge enclosing sediment traps (Fig. 1b, c). The region was probably uplifted during the late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene, leading to fluvial-glacifluvial erosion and subsidence of ~300–400 m in the SW Barents Sea22, with final submergence occurring as late as the Early Pleistocene23,24,25.

The shelf of the Barents Sea was repeatedly eroded by ice sheets during Pleistocene glaciations, and a large volume of the erosive products of these glaciations was deposited in the Bear Island Fan at the mouth of the Bjørnøyrenna Trough, located in the southwestern part of the Barents Sea in modern water depths from >400 to >3000 m14,26,27 (Fig. 1a). The fan has an extent of 215,000 km2 and is thus the largest submarine fan of glacial origin on Earth. It was fed by paleo-ice streams with a drainage basin area estimated at 576,000 km2,13 and with modeled ice-flow velocities estimated to be ~400 m/yr during the last glaciation28 (Fig. 1a).

The Quaternary stratigraphy of the SW Barents Sea margin can be divided into three units and seven regionally correlatable reflections, TeC–TeE/GI–GIII and R7–R1, respectively22,29,30 (Figs. 2, 3). The units form thick prograding accumulations on the slopes (Figs. 1c, 4), while sediment thicknesses decrease drastically on the shelf (Figs. 1c, 3, 4), where pre-Quaternary sediments subcrop locally. The Bear Island Fan contains deposits from megaslides and glacigenic debris flows14,27, and the fan is underlain by contouritic deposits of the Bjørnøya Drift31. The drift covers an area of ~1.8 × 104 km2, contains a sediment volume of ~5000 km3, and is inferred to have accumulated from the early Neogene to the early Quaternary due to intensified paleo-ocean-circulation controlled by tectonic events31. Shelf-edge glaciations in the Barents Sea during the Middle and Late Pleistocene are well documented by glacigenic debris flows on the upper slope and mega-scale glacial lineations on the shelf32,33. In contrast, relatively little is known about the extent and dynamics of ice sheets in the earliest Pleistocene, and thus their deposits contain important information about these early Quaternary glacials and their climatic drivers.

Seismic profile across the valleys on the shelf. Profile location is shown as Profile 2 in Fig. 1b. Indicated are Early Pleistocene tunnel valley infill (orange), Late Pleistocene tunnel valley infill (green), and R6 (red line). MPT: mid-Pleistocene transition. Seismic data courtesy of TGS.

Sedimentation rate plot from the margin30 and two wells located within the study area. Lithology from TGS Facies Map Browser42. Shown are R1–R7 reflections (black), reflections interpreted in this study (red), top and base of the Bjørnøya Drift (blue stippled lines31), mid-Eocene reflection (gold), and Top Paleocene reflection (pink). Profile location is shown as black line (Profile 4) in Fig. 1b. The plot “Sedimentation margin” shows the result from the compilation of Alexandropoulou et al.30. Blue bar shows the Bjørnøya Contourite Drift mapped by Rydningen et al.31, and the stippled line associated to R7 indicates from what time the contourite gets weakened by turbidites. Con: Contourite, GDF: Deposits of glacigenic debris flows, Int: Intraglacial reflection, MPT: mid-Pleistocene transition, Serra: Serravallian, Tur: Turbidite. Seismic and borehole data courtesy of TGS.

Intensification of sedimentation from Pliocene to Early Pleistocene (5.3–2.4 Ma)

The interpretation of high-quality three-dimensional (3D) seismic reflection data offers new insights into landform assemblages of the Quaternary paleoenvironments, and allows for detailed studies of the glacial processes prevailing at different stages of the Quaternary18,25,27,34. High-amplitude continuous seismic reflections of both polarities are observed within the ~650 m (650 ms) thick GI unit of the lower stratigraphy of the Bear Island Fan (Fig. 4), including the R7 reflection with an assigned age of 2.7 Ma, which marks its base30. The lowermost part of the GI unit belongs to the Bjørnøya Drift31, whilst the top of the contourite package is truncated by an unconformity (R6, with an assigned age of 1.78 Ma30) and as such, its internal reflections cannot be tracked onto the paleo-shelf (Fig. 4). Based on well 7216/11-1S located on the paleo-slope of the study area, the Neogene contourites (pre-R7) mainly consist of sand (63%), some silt (33%), and minor amounts of clay (4%) (Fig. 5a). These contourite sands, built up of sheets with a draping geometry and therefore lacking any characteristic contourite mound signature, were deposited at rates of 0.01–0.1 m/kyr from the middle Miocene to the onset of the Quaternary (Fig. 6a), matching the rates of 0.02–0.31 m/kyr estimated for the complete Bjørnøya Drift31. Contourites are still present in early Quaternary units (e.g., 2.6 Ma reflection), and the Bjørnøya Drift continued to grow under the influence of Early Pleistocene glacimarine sedimentation. Similar sandy along-slope deposition in colder climates is reported from the Falkland contourite sand sheet, which might be a modern analog to the Bjørnøya Drift35.

Paleoenvironments are shown as 3D chair views with RMS amplitude information blended over mapped seismic surfaces. a Contourite sedimentation (Pliocene). b Turbidite sedimentation (2.6 Ma). Black arrows indicate turbidites. c Debrite sedimentation (2.4 Ma). Black arrows indicate debrites. d Tunnel valley formation on a prograding shelf edge and downslope sedimentation (1.78 Ma). Black arrows show tunnel valleys and white arrows show gullies. The grain-size distribution for the tunnel-valley sedimentation is taken for the time interval 1.78–1.5 Ma. Grain size plot from the TGS Facies Map Browser is representative of the interval between the surface shown and the overlying surface. Stratigraphic level of surfaces is shown as red lines in Fig. 4. Seismic data courtesy of TGS.

Structure maps (left) and isopach maps (right) are shown for the different time periods. Isopach map represents package from the surface shown to the left to the overlying surface, and numbers on isopach maps represent average sedimentation rates for that time period. a Pliocene surface dominated by contouritic sedimentation. Contourites have here a draping geometry forming contourite sheets, and contourite sedimentation trends are not clearly visible. b 2.6 Ma surface, characterized by a contourite-turbidite bi-partite system. c 2.4 Ma surface, characterized by a debrite–turbidite bi-partite system.

On the surface defined by the second phase-reversed reflection above R7 (which has an assigned age of 2.6 Ma30), we identify low-sinuosity channels originating from the shelf edge and continuing down the slope (Figs. 5b, 6b). The channels are 200–900 m in width, traceable for up to 60 km (constrained downslope by the dataset), and characterized by low root mean square (RMS) amplitude values compared to the surrounding slope. Sedimentation rates within these channels are calculated to have been up to 1.5 m/kyr (Fig. 5b), while rates are much lower in areas where channels are lacking (Fig. 5b). Growing salt structures and the Senja Ridge basement high controlled sediment deposition on the paleo-slope (Fig. 1b, c), with highest infill rates in salt corridors and salt basins (Fig. 5b). Turbidites detected on glacial fans are used as a proxy for meltwater delivery18,36,37,38, and we interpret these channels to have been eroded by meltwater-fed turbidity currents. As the 2.6 Ma reflection is within the Bjørnøya Drift31, these channels evidence that a contourite-turbidite system prevailed after the onset of the Pleistocene. The muddy component within the Quaternary deposits (post-R7) of the Bjørnøya Drift increased (sand: 30%, silt: 20%, clay: 49%) compared to the pre-R7 levels (sand: 63%, silt: 33%, clay: 4%). Such a lithology is characteristic of channels along glaciated margins39,40. The meltwater for the identified channels is hypothesized to have originated from a proglacial fluvial system sourced from a terrestrial Barents Sea ice sheet located some distance from the shelf edge, a paleogeographic configuration also suggested by Knies et al.41. From 2.6 to 2.4 Ma, the sediments are thus likely delivered by glacifluvial systems from the terrestrial platform, forming silty to sandy turbidites on the slope, while alongslope sedimentation from contour currents also occurred. Such glaciomarine sedimentation from channelized meltwater discharge for the Early to Middle Pleistocene deposits of the Bear Island Fan is also hypothesized by Laberg et al.27 based on 3D seismic reflection data.

Our 3D seismic interpretation is consistent with previous studies on the lithology and origin of the sandy contourites of the Bjørnøya Drift31. However, we additionally document channels in the uppermost part of the drift, suggesting downslope sediment transport from the Barents Sea shelf during the latest period of the Bjørnøya Drift deposition. The 3D seismic reflection data interpretation reveals that the slope channels originate from the terrestrial/marine continuation of a possible glacifluvial system from a subaerial southwestern Barents Sea from 2.6 to 2.4 Ma. The slope channels identified here, therefore, indicate glacimarine conditions, which is also supported by the findings of Laberg et al.27, thus marking the onset of glacial intensification on the SW Barents Sea shelf in the Early Pleistocene. However, our data do not reveal any evidence of shelf-edge glaciation at this time.

First shelf-edge glaciation from ⁓2.4 to 1.8 Ma

Debris-flow deposits represented by high-amplitude seismic reflections (Fig. 4) with less continuity compared to the contourites and low RMS amplitude values (Fig. 5c) are mapped in the package above the Bjørnøya Drift (from 2.4 Ma reflection) to the R6 (1.78 Ma) reflection. The stacked debris-flow deposits originate along the mapped length of the paleo-shelf break (Fig. 6c), and reach sedimentation rates of up to 0.8 m/kyr at ~20 km distance from the shelf break. Their lithology is dominated by clay (86%), while both silt (2%) and sand (5%) contents are much lower than in the contourite-turbidite system from 2.6–2.4 Ma. These debrite intervals additionally include volcaniclastic rock fragments (7%; TGS Facies Map Browser42), unique for the Neogene and Quaternary sequences of the fan (Fig. 4). The increase in fine-grained material is consistent with an increase in debris-flow activity, indicating a shift to a downslope dominated sediment supply, in contrast to the along-slope sedimentation that comprise the Bjørnøya Drift. Debris flows on trough mouth fans are commonly interpreted to indicate a glacial origin with reduced meltwater contribution, and an ice sheet at or close to the shelf edge12,38,43,44,45. With an estimated age of ⁓2.4 Ma, we therefore propose that these debris flows indicate an Early Pleistocene shelf-edge glaciation in the southwestern Barents Sea.

Glacially-influenced downslope deposits of Early Pleistocene to even Miocene age in our study area have been suggested based on seismostratigraphic and borehole analyses in previous studies25,46. Full glacial conditions with grounded ice reaching the shelf edge have been suggested at R5 time (1.5 Ma) based on seismic facies analysis29,32,33. Forsberg et al.47 and Butt et al.48 concluded that the Barents-Svalbard Ice Sheet reached the shelf break during full glacial conditions from 1.7–1.6 Ma onwards. Based on widespread mega-scale glacial lineations, Harishidayat et al.25 suggested extensive Early Pleistocene glaciations in the SW Barents Sea. Our findings suggest grounded ice at the shelf edge somewhere between 2.6 and 1.78 Ma, likely as early as ⁓2.4 Ma.

A first shelf-edge glaciation at ⁓2.4 Ma is consistent with polar Arctic paleoenvironmental studies that show a shift into summers cooler than today after ~2.2 Ma49. There is also evidence of North American continental-scale ice sheets extending southwards from Canada at 2.4 Ma50. However, major glaciations of the Laurentide Ice Sheet did not occur before ca. 1.3 Ma50. In addition, analysis of sediment cores from the central Arctic Ocean (Lomonosov Ridge) suggests four major glaciations since 0.7 Ma and concludes large-scale northern Siberian glaciations began much later than other Northern Hemisphere ice sheets51.

Large valleys on the shelf and muddy downslope deposition on the fan (1.78–0.78 Ma)

The Early Pleistocene stratigraphy of the paleo-shelf is characterized by transparent sediment packages crosscut by several high-amplitude seismic reflections with overall U-shaped morphologies, forming reverse-sloping incised valleys (Figs. 2, 8). Six such valleys up to 12 km in width and 200 m in depth are expressed on the shelf of the R6 surface, laterally limited by walls dipping with 2°–20° (~7° in average) (Figs. 7a, 8; Supplementary Fig. 1). The lengths of the valleys vary from 10 to 30 km, which are the minimum lengths as the valleys extend beyond the edge of the dataset. The valleys are straight and parallel with an E–W to ENE–WSW orientation and are all stratigraphically located above the R6 reflection (~1.78 Ma) (Fig. 2). Their bases are characterized by continuous, high-amplitude reflections that follow the morphology of the oldest (first) valley expressed in the seismic data. Streamlined landforms dominate the beds of the valleys, having the same orientation as mega-scale glacial lineations outside of the valleys (Fig. 7a), but with different geometries, with the landforms in the valleys having a positive relief, forming ridges with heights of 10–30 m and widths of 500–2000 m (Fig. 8e). The reflections defining the bases of the valleys can be tied to the R6, R5, and R4 reflections (Fig. 4), and their age can be constrained to 1.78–0.99 Ma30. An additional set of valleys is observed between R4 and R3 (ages 0.99–0.78 Ma) in our dataset. All these valleys terminate on the shelf before the paleo-shelf break, and such valleys have also been identified in 2D seismic reflection profiles by Sættem et al.52 (Fig. 1a). The geomorphology in the area from the end of the valleys to the shelf break is dominated by curvilinear grooves (5–30 m in depth; Fig. 8e) roughly following the valley orientation for the last 30–40 km towards the shelf break (Figs. 7a, 8). These curvilinear grooves differ from the glacial lineations, as the elongated landforms have depths of <10 m (Fig. 8e).

Structure maps (left) and isopach maps (right) are shown for the different time periods. Isopach map represents package from the surface shown to the left to the overlying surface, and numbers on isopach maps represent average sedimentation rates for that time period. a R6 surface (1.78 Ma) with tunnel valley infill on the shelf and downslope deposition on the slope. v: tunnel valleys expressed on R6 surface. b IntG surface, characterized by streamlined landforms on the shelf and down-slope-dominated sedimentation on the slope.

a Structure map of seismic horizon R6. Shelf is dominated by large valleys, lineations, and grooves, whereas gullies are identified on the uppermost slope. b Slope profiles along three tunnel valleys. Numbers on x-axes are in km, on y-axes in m. Profile locations are shown in (a). c Structure map with 3D view into the shelf–slope transition of reflection R6 with maximum widths of the six tunnel valleys. d Structure map showing the morphology of tunnel valleys, grooves, and lineations. e Profiles of lineations, grooves, and ridges within valleys. Numbers on x-axes are in km, on y-axes in m. Profile locations are shown in (d).

On the shelf, the seismic unit between R6 and R5 has a high-amplitude chaotic to homogenous seismic facies (Fig. 2) with sedimentation rates of 0.1–0.2 m/kyr (Fig. 4), whilst the packages from R5 to R3 are characterized by a low-amplitude homogenous seismic facies (Fig. 2), with sedimentation rates of 0.3–0.7 m/kyr (Fig. 4). Tying these reflections (R5, R4, and R3) to the slope, they each form ~100 m-thick prograding units that consist of high-amplitude seismic reflections (Fig. 4). The lithology of these deposits is dominated by mud with some sandy interlayers. The grain-size distribution in borehole 7216/11-1S is comparable for R6–R5 (sand: 6%, silt: 12%, clay: 82%), R5–R4 (sand: 9%, silt: 12%, clay: 79%), and R4–R3 (sand: 16%, silt: 16%, clay: 67%). On the uppermost slope, gullies with widths of 200–500 m and depths of up to 50 m characterize the beginning of this time interval (R6; Figs. 5d, 7a). These gullies have negative impedance contrasts and high RMS amplitude values with sand contents from 6% to 16%, unlike the earliest-Pleistocene channels (associated with phase-reversed reflection above R7) that are characterized by positive impedance contrasts and low RMS amplitude values with sand contents of 30%.

Subglacial origin of the large valleys

The valleys identified in the southwestern Barents Sea erode into Neogene and Oligocene sedimentary bedrock (Figs. 2–4) and are characterized by straight, sub-parallel profiles (Fig. 8a). The valleys have similar depths to a broad compilation of tunnel valleys and meltwater channels on other formerly glaciated margins around the world prepared by Kirkham et al.53, yet have widths far in excess (up to 12 km compared to a maximum of ~7.5 km in the Kirkham et al.53 compilation). Those with widths most similar to the Barents Sea examples are Antarctic channels54, Canadian tunnel valleys55, or specific tunnel valleys in the North Sea56,57. The Barents Sea valleys also have a specific geometry; they are sub-parallel to each other with crosscutting relationships not observed, which differs from many other reported tunnel valleys and meltwater channels (e.g., Kirkham et al.53). However, tunnel valleys with similar geometries have been identified offshore Nova Scotia58 and in Northern Germany59, with depths extending to >400 m below present sea level and widths of 2–3 km in average for the valleys offshore Nova Scotia58. Similar to the infill of the tunnel valleys in our study, the sediment infills of the valleys identified in Nova Scotia have chaotic and transparent to reflection-free seismic facies58.

In addition, geometries (elongated and sub-parallel landforms) and erosion into underlying bedrock are similar to tunnel valleys forming the New York Finger Lakes, which were subglacially cut into undeformed Devonian sedimentary bedrock, mainly consisting of shale60. Thus, the valleys identified in our study area are wider than most tunnel valleys identified on Earth and are sub-parallel to each other (crosscutting relationships are not observed). The geomorphology, geometry, and orientation of the Early Pleistocene valleys of the Barents Sea also differ from Late Pleistocene valleys observed in the region61,62 (Fig. 2). The straight extents and parallel conformity of the valleys are comparable to the grooves within bundle structures observed on the Antarctic continental shelf, interpreted to have formed by accumulation and sculpting of basal deformation till under their parent ice streams63. However, the valley axes show no consistent trend of deepening in any direction (with undulating thalwegs, Fig. 8b), which is the definitive characteristic of tunnel valleys.

The valleys identified in this study are associated with turbidites on the slope and curvilinear grooves on the shelf (outside the valleys), an observation that is consistent with a subglacial meltwater origin (Figs. 5d, 7a). We thus interpret them to be tunnel valleys. We argue that these tunnel valleys were formed by enhanced meltwater discharge below a grounded, warm-based ice sheet, similar to tunnel valleys documented from other glaciated shelves57,64,65,66. As such, the sediments constrained by reflections forming R6–R3 on the slope are interpreted as the product of glacigenic debris flows and meltwater-fed turbidity currents, as also described by Laberg et al.27. Large volumes of meltwater, the persistency of focused subglacial meltwater discharge, or the structural control related to the Senja Ridge could be reasons for the exceptional width of these tunnel valleys.

Large volumes of glacial meltwater seem to have been discharged to the paleo-slope below an extensive Barents Sea Ice Sheet during at least four pulses between 1.78 and 0.78 Ma, when the Barents Sea was partly a terrestrial platform19,20,23,24. The curvilinear grooves at the transition between tunnel valleys and shelf break are interpreted as iceberg ploughmarks (Fig. 8d, e), indicating a transition from channelized subglacial meltwater discharge in tunnel valleys into ice mass loss via iceberg calving. This interpretation is supported by the geometries of ploughmarks identified both at the seafloor and at paleo-surfaces of the SW Barents Sea67,68. This study highlights that subglacial-valley sediment supply to the Bear Island Fan has existed after the Early Pleistocene (~1.78 Ma), with at least four shelf-edge glaciations occurring from 1.78 to 0.78 Ma. Meltwater might have actively been discharging beneath a larger, warm-based, potentially streaming grounded ice sheet, as indicated by lineations in the terrains outside the valleys. The 500–2000 m wide ridges inside the valleys are interpreted as eskers, a landform also identified in tunnel valleys of the North Sea66 (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, the eskers of this study do not show the winding-ridge geomorphology typical for many eskers66. Severe and extensive glaciations on the continents surrounding the Norwegian-Greenland Sea from ⁓1.78 Ma have been proposed based on far-field evidence such as ice-rafted debris69 and the clay mineralogy41. The timing of these extensive glaciations is in agreement with the full establishment of glacial-interglacial cycles by ~1.8 Ma at Lake El’gygytgyn in the Russian Arctic70.

Increased meltwater discharge related to stronger seasonality in the Early Pleistocene could have contributed to the pronounced shape of these tunnel valleys. The ages of the reflections defining these tunnel valleys correlate with the three most pronounced super-interglacials70, with R5 correlating with MIS49 and MIS55, and R4 correlating with MIS31. This observation strengthens our suggestion that these tunnel valleys have formed by over-pressurized subglacial meltwater and that they indicate massive ice sheet collapses of the Barents Sea Ice Sheet. Such conclusions have also been drawn for the Laurentide Ice Sheet58,60. The tunnel valleys are all of Early Pleistocene age and thus all formed during the 41-kyr climate cycles. Due to sparse sediment preservation from the time period 2.7–1.78 Ma on the shelf, we cannot exclude that these valleys formed earlier during 41-kyr cycles, however, we see no evidence to support tunnel-valley formation in this earlier time period.

Glacial lineations and glacigenic debris flows after the mid-Pleistocene transition (<0.78 Ma)

The paleogeography of the study area changes from a slope-dominated area at the beginning of the Pleistocene into a shelf-dominated area from <0.78 Ma (Figs. 6, 7), presumably as a result of shelf progradation due to extensive glaciations. The sediments above the valleys (above R3, <0.78 Ma) mainly consist of subglacial till accumulated at an estimated rate of 0.1–1.5 m/kyr (Fig. 7b). We observe glacial lineations along surfaces characterized by horizontal high-amplitude seismic reflections (Fig. 2). Glacigenic debris flows are deposited on the paleo-slope with rates of 0.4–2.1 m/kyr (rate from well; Fig. 2). Subglacial valleys, however, are not identified until horizon IntA (Figs. 2, 9), which most likely represent tunnel valleys formed during the Weichselian glaciation. These Late Pleistocene tunnel valleys have smaller widths and are less elongated compared to the Early Pleistocene tunnel valleys. In contrast, there is no evidence for large subglacial meltwater discharges in units above R3, the mid-Pleistocene transition. Thus, we suggest a Barents Sea ice sheet with less abundant channelized subglacial meltwater following the mid-Pleistocene transition. Such a change in thermal regime has also been suggested for GIII (<0.2 Ma) in a previous study27. The reported observation from meltwater-driven subglacial conditions before the mid-Pleistocene transition into a subglacial regime with lower meltwater contribution shows that the transition includes major ice dynamical and climatic changes. At Lake El’gygytgyn, more than 17 super-interglacials were identified in the 41-kyr world, compared to only 2 of these super-interglacials in the 100-kyr world70.

a Magnetostratigraphy for Pliocene and Pleistocene. b Oxygen isotope curve for the Plio-Pleistocene84. c Landforms mapped out in different stratigraphic levels of this study. R1–R7 reflections as marker horizons. d 3D view into Quaternary stratigraphy of the Bear Island Fan with Base Quaternary surface (2.6 Ma reflection). Con: Contourite, Int: Intraglacial. MPT: mid-Pleistocene transition. Seismic data courtesy of TGS.

Formation of the largest glacial fan on Earth

Seismic interpretation shows changes in landform assemblages and sedimentation patterns both along the SW Barents Sea shelf and on the slope of the proximal Bear Island Fan over the Pliocene–Pleistocene (Fig. 5). Sandy contourites from the NE Atlantic current were deposited on the slopes offshore the southwestern Barents Sea prior to trough-mouth-fan growth, which started building out from glacial meltwater-sourced flows at the onset of the Quaternary (⁓2.6 Ma). Strong ocean currents may have redistributed the fine-grained sediments delivered by the turbidites originating from the paleo-shelf break at the Plio-Pleistocene transition, resulting in an exclusively sandy sediment record for that period.

Sediment supply to the Bear Island Fan is controlled by tectonic processes throughout the Neogene, and climatic developments in the Plio-Pleistocene. The supply to the shelf strongly increased at the onset of the Quaternary, as a result of glacial intensification and ice-sheet build-up. From 2.6 to 2.4 Ma, a contourite–turbidite system formed the base of the Bear Island Fan (Fig. 10a). In this bi-partite system, sedimentation rates increased to 1.5 m/kyr on the uppermost slope to 0.7 m/kyr downslope within the study area. The enhanced supply of mud-dominated sediments in the Early Pleistocene likely resulted in the drowning of contourite deposits by downslope input and the formation of the largest trough mouth fan on Earth. Meltwater for the Early Pleistocene turbidites might have been delivered by a shelf-edge glaciation or, more likely, by glacio-fluvial erosion during relative sea-level lowstands, as documented by proglacial river systems in the SW Barents Sea71. Braided rivers discharging mountain ice caps could have discharged exceptionally large volumes of meltwater to the slopes of the Bear Island Fan and triggered turbidity currents. Muddy glacigenic debris flows, accumulating with rates of 0.8 m/kyr, overlie the sandy deposits of the contourite–turbidite system. We suggest that grounded ice-streams extended to the shelf break from 2.4 Ma onwards, and provided icebergs, enhanced quantities of subglacial debris, and large volumes of glacial meltwater (Fig. 10b; Supplementary Fig. 2). A weakening of the contour current and the enhanced sedimentation related to the shelf-edge glaciation resulted in the absence of contouritic deposition. Weakening of contour current systems during glaciations has also been reported further south along the NE Atlantic margin11.

a Braided rivers feeding the Bear Island Fan with large quantities of meltwater and sediments. The Barents Sea was a terrestrial platform at that time, with growing Svalbard-Barents Sea Ice Sheet (SBIS) and Fennoscandian Ice Sheet (FIS). Sandy turbidites on the fan. b First shelf-edge glaciation at ⁓2.4 Ma. Muddy debris flows on the fan. c 1.78–0.78 Ma: Tunnel valleys (TVs) and mega-scale glacial lineations (MSGLs) identified on the shelf. Gullies and muddy debris flows dominate the slope sedimentation. d Middle and Late Pleistocene: Polar conditions with MSGLs on the shelf, and muddy debris flows on the slope. No large amount of glacial meltwater. Sedimentation on fan predominantly sandy (golden), or predominantly muddy (green). BRIS: Bjørnøyrenna Ice Stream, IDIS: Ingøydjupet Ice Stream.

Subglacial valleys formed in the Early Pleistocene (1.78–0.78 Ma), and acted as focused sediment-routing and freshwater-discharge systems to the Bear Island Fan (Fig. 10c), with likely source areas across mainland Arctic Norway (Northern Fennoscandia). These tunnel valleys formed exclusively to the east of the Senja Ridge basement high in the study area, where weaker Paleogene and Neogene sediments were presumably more easily eroded. Therefore, this study also highlights the role of subsurface geology in subglacial valley formation. A shift from along-slope to down-slope sedimentation resulted in a change in sediment provenance. Thus, the mid-Pleistocene transition was associated with a shift in sediment source, reflecting changes in ice-sheet geometry consistent with increasing ice volumes across the central Barents Sea from the Early to the Middle Pleistocene.

Channels related to the Weichselian glaciation have been reported on continental slopes along the Norwegian margin18,34,72. Similarly, the gullies on the Bear Island Fan in the Early Pleistocene could indicate a warm-based Barents Sea Ice Sheet until 0.78 Ma, with large volumes of glacial meltwater discharged to the slope. On the shelf, tunnel valleys, iceberg ploughmarks, and mega-scale glacial lineations have been identified in the period from 1.78 to 0.78 Ma (Figs. 7a, 9), with glacial lineations also reported by Harishidayat et al.25. We thus suggest that meltwater contribution to the Bear Island Fan was a more dominant process before the mid-Pleistocene transition.

The deposits of glacigenic debris flows dominate the post-0.78 Ma stratigraphy and likely document a transition into an ice sheet with less channelized meltwater related to the mid-Pleistocene transition (Fig. 10d). The tunnel valleys, observed from 1.78 to 0.78 Ma, are predominantly formed during the obliquity-dominated 41-kyr cycles, before the mid-Pleistocene transition. For the full-glacial conditions during the precession- and eccentricity-dominated cycles, downslope sediment transfer as glacigenic debris flows from more extensive shelf-edge glaciations overtook meltwater delivery (Fig. 9).

The mid-Pleistocene transition in other glacial fans

This study shows that the mid-Pleistocene transition left a distinct signal in the Arctic Bear Island Fan (71–73°N). In the mid-latitude North Sea Fan (67–69°N) located along the same margin, this transition is less distinctive: Here, Early Pleistocene sedimentation is dominated by contourite and debrite sedimentation, and switched into turbidite-, debrite-, and megaslide sedimentation in the Late Pleistocene12,73,74. The North Atlantic current deposited contourites likely throughout the Early Pleistocene in the North Sea Fan area, whereas the contouritic sedimentation of this ocean current was weakened in the very Early Pleistocene in the Bear Island Fan. The downslope sediment input to the North Sea Fan mainly originates from the Northern North Sea, an area characterized by multiple generations of tunnel valleys. These valleys formed during the Elsterian, Saalian, and Weichselian glaciations, with no valleys documented from the Early Pleistocene53,57,66. This might reflect a different glaciological configuration, with Early-Pleistocene ice sheets in the North Sea not being developed to the shelf edge compared to the ice sheets on the high-latitude shelves. However, Early Pleistocene meltwater channels are documented in several studies of the southwestern Barents Sea52,71, which is consistent with more extensive glaciations in this region.

For the Lancaster Sound trough mouth fan in the NW Baffin Bay, preglacial slope sedimentation and slope aggradation related to ice streaming characterize the Early Pleistocene75. The sedimentation switched into major ice streams supplying larger glacigenic debris flows in the Middle and Late Pleistocene75, an observation that is similar to glacigenic debris flows as the dominating sediment process in the Bear Island Fan. Sediments of the eastern Prydz Bay and the Prydz Fan in Eastern Antarctica record major Pliocene–Pleistocene expansions and retreats of the Lambert Glacier-Amery ice shelf system prior to 0.78 Ma, with repeated advances and retreats to the shelf break76. The groundling line of the Lambert Glacier did, however, not extend to the shelf break after 0.78 Ma76, which is different from the extensive shelf-edge glaciations in the Middle and Late Pleistocene of the SW Barents Sea. Interestingly, studies on deep-ocean foraminiferal oxygen isotopic ratios suggest that the mid-Pleistocene transition was initiated by an abrupt increase of Antarctic ice volume around 0.9 Ma ago77, which is a similarity between the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Barents-Svalbard Ice Sheet. A transition similar to Prydz Bay has also been observed in five other key sectors of East and West Antarctica and has been suggested to represent a change from polythermal to present polar cold, dry-based conditions78. However, that change dates to the Late Pliocene (ca. 3 Ma), which is considered an antecedent of the Arctic counterpart78.

Implications for ice-sheet evolution and paleogeographic reconstruction

The paleoenvironments of the Arctic SW Barents Sea underwent two major transitions in the Pleistocene. Firstly, the transition from the Pliocene into the Pleistocene resulted in dynamic and complex changes in the paleogeographic setting from a terrestrial platform in the Pliocene into a fully glaciated shelf by ~2.4 Ma. Secondly, the mid-Pleistocene transition was associated with a shift from stacked subglacial tunnel valleys with high meltwater delivery predating the transition to stacked glacigenic debris flows without valleys and, therefore, lower meltwater delivery to the Bear Island Fan postdating the transition.

High-latitude trough mouth fans are often dominated by low-water-content glacigenic debris flows79. In contrast, meltwater turbidites are more commonly documented from mid-latitude fans13,18,38,45,80, and the relative importance of meltwater appears greater at lower than at higher latitudes81. Here, we show that the meltwater signal at high-latitude Bear Island Fan in the Early Pleistocene (41-kyr world) was comparable to the meltwater discharge in Late Pleistocene mid-latitude trough mouth fans. Meltwater input is thus important for both mid-latitude and high-latitude trough mouth fans.

In addition to changes in the slope sedimentation, there are new findings in the mode of sediment delivery along the continental shelves. Our interpretations show that tunnel valleys formed in the Arctic in the Early Pleistocene (41-kyr world), while these valleys predominantly occur in the Middle and Late Pleistocene at mid-latitude shelves (100-kyr world), such as the North Sea and the Baltic Sea57,66. For the Barents Sea, the shift into more polar ice conditions with little meltwater production occurred sometime around the mid-Pleistocene transition. The formation of the Early Pleistocene tunnel valleys in the SW Barents Sea can likely be associated with outburst floods, which is one of the dominant formation mechanisms for such valleys66. In addition, we show that tunnel valleys do not exclusively occur in central parts of glaciated shelves57,64,65, but that they can also be located close to (paleo-)shelf edges.

Spatio-temporal evolution of the SW Barents Sea: comparison with previous studies

We document an extensive Early Pleistocene shelf-edge glaciation in the SW Barents Sea as early as 2.4 Ma. These conclusions are drawn based on high-quality 3D seismic data from the shelf edge and borehole data, allowing integrated interpretation of buried geomorphologies such as glacigenic debris flows, meltwater turbidites, and tunnel valleys that could previously not been imaged at all or not in that detail. By integrated interpretation of the seismic and sedimentary records of this Arctic margin, we provide new observation models for the Early and Middle Pleistocene glaciations and conclude that the large glaciations in the Barents Sea occurred earlier than most studies previously reported.

Our suggested age of the first shelf-edge glaciation is in line with the results of Harishidayat et al.25, who propose such an ice-sheet configuration at around 2.58 Ma based on the first appearance of mega-scale glacial lineations in lower-resolution 3D seismic reflection data. In the glacial model of Knies et al.41, the mountainous regions of the Barents Sea region are covered by ice masses from 3.6 to 2.4 Ma with glacio-fluvial drainage as the main sediment transport mechanism, which fits well with our suggestions for that time period. A continental slope with sediment predominantly deposited from meltwater overflows and underflows during the late Pliocene-Early Pleistocene is also suggested by Laberg et al.27 and correlates with the sandy turbidites identified until 2.4 Ma in our study. All this evidence supports our interpretation for a shelf-edge glaciation at ca. 2.4 Ma.

Glacial expansion across Svalbard between 2.7 and 2.58 Ma, recorded by glacigenic debris-flows deposits in the Sjubrebanken trough mouth fan (Fig. 1a), is suggested in a recent study30. That study suggest a glacial intensification for the whole Barents Sea-Svalbard region at around 1.5 Ma, while we here show that extensive shelf-edge glaciations have occurred already at 2.4 Ma in the SW Barents Sea.

The transitional growth phase of the Barents Sea Ice Sheet from 2.4 to 1.0 Ma41 correlates with shelf-edge glaciations and subglacial channels documented in our study, and we show that the Early Pleistocene glaciations were associated with abundant subglacial meltwater that was discharged in major tunnel valleys. However, Knies et al.41 document repeated advances to the shelf edge after 1 Ma, whereas we see evidence for fully developed ice sheets delivering sediment to the shelf edge already from 2.4 Ma. Andreassen et al.33 defined the first documented shelf-edge glaciation around 1.5 Ma based on channelized meltwater discharge on the slopes and glacigenic debris flows, whereas we observe meltwater-discharge channels using high-quality 3D seismic data already in the beginning of the Pleistocene. The glacial intensification for the whole Barents Sea-Svalbard region suggested from around 1.7 to 1.5 Ma30,47,48 correlates with the tunnel valleys observed in our study. A time-transgressive development of the Barents Sea/Svalbard Ice Sheet was suggested based on the onset and growth of trough mouth fans on the north-western Barents Sea margin (Isfjorden fan, Bellsund fan, Hornsund fan, Storfjorden fan; Fig. 1a) at around 1.3 Ma82. In that study, 1.3 Ma indicates the change from not fully developed ice streams within the glacial troughs into fully developed ice streams feeding the glacial fans82.

At a similar paleogeographic location, Sættem et al.52 observed channel infill in the lower part of a Pleistocene succession that could possibly consist of glacio-fluvial gravelly sand intercalated with subglacial till (Fig. 1a; borehole 7316/06-U-01). These channels could indicate grounded ice to the shelf break, and may have formed at the margin of a Late Pliocene ice cap or ice sheet covering large parts of the Barents Sea area52. The location close to the shelf edge, and channel widths of 2–10 km and depths of ca. 150 m are comparable with the tunnel valleys observed farther south in this study. Therefore, tunnel valleys could have been formed in the Early Pleistocene along the complete shelf of the SW Barents Sea.

In agreement with other studies, our results indicate full glaciations following the mid-Pleistocene transition, characterized by colder periods with less meltwater production in the last 0.7 Ma and a switch into glacigenic debris flows27,33,41. The surfaces of the Late Pleistocene are mainly dominated by mega-scale glacial lineations (Fig. 7b).

Methods

Seismic data

We use 5754 km2 of high-quality, industry-standard processed 3D seismic reflection data of the Bear Island Fan region in the SW Barents Sea to establish the stratigraphy and geological processes forming the largest glacial fan on Earth from Neogene to present-day, with a focus on the Early Pleistocene. The 3D multi-client seismic data (cube called Carlsen 3D) were acquired in 2017 with a triple source (flip/flop/flap; airgun volumes of 2965 in3) and a shot point interval of 12.5 m. The acquisition consisted of twelve, 8100 m long streamers with 75 m separation. The data was high-quality seismic processed by TGS using Clari-FiTM broadband technology. The data have a vertical resolution of ~2 m in the near subsurface, and a bin size of 20 m (processing output grid of 12.5 m × 12.5 m). The acquisition included ties to four borehole locations (7216-11-1S, 7117/9-1, 7117/9-2, and 7218/11-1). Interpreted horizons are not available for free since this is a commercial survey which has to be licensed.

Seismic interpretation

Seven seismic horizons have been picked with an inline spacing of 200 m, followed by gridding to 12 m, seismic horizon attribute extraction, and seismic geomorphological interpretation. In particular, the root mean square (RMS) amplitude attribute resulted in enhanced geomorphological visualization (Supplementary Fig. 2). Isopach maps were generated to study sediment transport and deposition. P-wave velocities of 1500 m/s were used for time-to-depth conversion of the water column, and P-wave velocities of 2000 m/s for time-to-depth conversion of the Neogene and Quaternary stratigraphy. The dataset has American polarity, and in the illustrations in this paper, reflections caused by an increase in acoustic impedance (positive-amplitude reflections), are shown as black in profiles, while reflections caused by a decrease in acoustic impedance (negative-amplitude reflections) are shown as white. This means that the hard seabed is shown in black, whereas the soft beds are shown in white. Horizons interpreted site-wide are Middle Eocene, Base Pleistocene (R7), 2.6 Ma, 2.4 Ma, R6, IntraG (Intraglacial G), and Seabed (Figs. 3, 4). The age of the two early Quaternary reflections, 2.6 and 2.4 Ma reflections, was calculated assuming a constant sedimentation rate on the paleo-slope for the sequence of R7 (2.7 Ma) to R6 (1.78 Ma). The chronostratigraphic information from Alexandropoulou et al.30 is tied to the four exploration boreholes and seismic horizons located within the 3D seismic cube (7216-11-1S, 7117/9-1, 7117/9-2, and 7218/11-1; Fig. 3). IntA (Intraglacial A), and R1–R5 are horizons shown in seismic profiles of the publication. The sedimentation rates are estimated based on the thickness maps created by the high-quality 3D seismic data.

Chronostratigraphy

We follow the subdivision of the glacigenic Quaternary interval in three units GI to GIII/TeC-TeE by Vorren et al.22 and Faleide et al.29. The regional horizon R7 marks the base of the subunit GI and therefore the base of the Quaternary deposits22,29,83. The stratigraphy of the Pleistocene in the southwestern Barents Sea is defined by seven key horizons (R1–R729,30). Regional correlation gives ages of 0.2 Ma for R1, 0.42 Ma for R2, 0.78 Ma for R3, 0.99 Ma for R4, 1.5 Ma for R5, 1.78 Ma for R6, and 2.7 Ma for R730. The chronostratigraphic information is not taken from the four boreholes of this study, but taken from seismic surfaces covering the study area30. Uncertainties related to the establishment of the chronology of these seven reflections are discussed in that study30.

Well information

The lithologies of borehole 7216-11-1S are based on analysis of core cuttings as processed and shown within the TGS Facies Map Browser, which uses the input of the lithology log from the Norsk Hydro report42. In addition, there are no cuttings available from the uppermost stratigraphy; core cuttings stratigraphically-higher than reflection R2, and thus younger than 0.42 Ma, do not exist in the report (see gap in Fig. 4).

Sedimentation rates are averages for the different sedimentary deposits, and calculated by dividing the thickness of the sequences by their chronostratigraphic age difference. Sequences of downslope deposits, such as debrites and turbidites, are packages consisting of stacked individual events, and deposited episodically. In order to compare the different sediment packages, averages have also been calculated for the deposits of these episodic events using the key reflections of the chronostratigraphy of a recent publication30.

Data availability

The 3D multiclient seismic data (Carlsen3D) were acquired in 2017 under license from the Norwegian Authorities. The data were provided courtesy of TGS., and the availability is regulated by the licensing terms. Borehole data are available from www.sodir.no42.

References

Maslin, M. A. & Ridgwell, A. J. Mid-Pleistocene revolution and the ‘eccentricity myth’. Geol. Soc. Lond. Special Publ. 247, 19–34 (2005).

Maslin, M. A. & Brierley, C. M. The role of orbital forcing in the Early Middle Pleistocene Transition. Quat. Int. 389, 47–55 (2015).

Bush, M. B., Miller, M. C., De Oliveira, P. E. & Colinvaux, P. A. Orbital forcing signal in sediments of two Amazonian lakes. J. Paleolimnol. 27, 341–352 (2002).

Prokopenko, A. A., Hinnov, L. A., Williams, D. F. & Kuzmin, M. I. Orbital forcing of continental climate during the Pleistocene: a complete astronomically tuned climatic record from Lake Baikal, SE Siberia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 3431–3457 (2006).

Denton, G. H., Prentice, M. L., Kellogg, D. E. & Kellogg, T. B. Late Tertiary history of the Antarctic ice sheet: evidence from the Dry Valleys. Geology 12, 263–267 (1984).

Svendsen, J. I. et al. Late Quaternary ice sheet history of northern Eurasia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 1229–1271 (2004).

Dowdeswell, J. A. et al. The variety and distribution of submarine glacial landforms and implications for ice-sheet reconstruction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 46, 519–552 (2016).

Dowdeswell, J. A., Hogan, K. A. & Le Heron, D. P. The glacier-influenced marine record on high-latitude continental margins: synergies between modern, Quaternary and ancient evidence. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 475, 261–279 (2019).

Batchelor, C. L. & Dowdeswell, J. A. The physiography of high Arctic cross-shelf troughs. Quat. Sci. Rev. 92, 68–96 (2014).

Hjelstuen, B. O. & Sejrup, H. P. Latitudinal variability in the Quaternary development of the Eurasian ice sheets—evidence from the marine domain. Geology 49, 346–351 (2021).

Batchelor, C. L. et al. Glacial, fluvial and contour-current-derived sedimentation along the northern North Sea margin through the Quaternary. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 566, 116966 (2021).

Nygård, A., Sejrup, H. P., Haflidason, H. & Bryn, P. The glacial North Sea Fan, southern Norwegian Margin: architecture and evolution from the upper continental slope to the deep-sea basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 22, 71–84 (2005).

Gales, J. et al. Processes influencing differences in Arctic and Antarctic trough mouth fan sedimentology. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 475, 203–221 (2019).

Hjelstuen, B. O., Eldholm, O. & Faleide, J. I. Recurrent Pleistocene mega-failures on the SW Barents Sea margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 258, 605–618 (2007).

Leynaud, D., Mienert, J. & Vanneste, M. Submarine mass movements on glaciated and non-glaciated European continental margins: a review of triggering mechanisms and preconditions to failure. Mar. Pet. Geol. 26, 618–632 (2009).

Laberg, J. S. & Camerlenghi, A. The significance of contourites for submarine slope stability. Dev. Sedimentol. 60, 537–556 (2008).

Gatter, R., Clare, M. A., Kuhlmann, J. & Huhn, K. Characterisation of weak layers, physical controls on their global distribution and their role in submarine landslide formation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 223, 103845 (2021).

Bellwald, B., Planke, S., Becker, L. W. & Myklebust, R. Meltwater sediment transport as the dominating process in mid-latitude trough mouth fan formation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Lasabuda, A., Laberg, J. S., Knutsen, S. M. & Høgseth, G. Early to middle Cenozoic paleoenvironment and erosion estimates of the southwestern Barents Sea: insights from a regional mass-balance approach. Mar. Pet. Geol. 96, 501–521 (2018).

Lasabuda, A. P. et al. Cenozoic uplift and erosion of the Norwegian Barents Shelf—a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 217, 103609 (2021).

Vorren, T. O., Richardsen, G., Knutsen, S. M. & Henriksen, E. Cenozoic erosion and sedimentation in the western Barents Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 8, 317–340 (1991).

Dimakis, P., Braathen, B. I., Faleide, J. I., Elverhøi, A. & Gudlaugsson, S. T. Cenozoic erosion and the preglacial uplift of the Svalbard–Barents Sea region. Tectonophysics 300, 311–327 (1998).

Butt, F. A., Drange, H., Elverhøi, A., Otterå, O. H. & Solheim, A. Modelling Late Cenozoic isostatic elevation changes in the Barents Sea and their implications for oceanic and climatic regimes: preliminary results. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 1643–1660 (2002).

Harishidayat, D., Johansen, S. E., Batchelor, C., Omosanya, K. O. & Ottaviani, L. Pliocene–Pleistocene glacimarine shelf to slope processes in the south‐western Barents Sea. Basin Res. 33, 1315–1336 (2021).

Laberg, J. S. & Vorren, T. O. The middle and late Pleistocence evolution and the Bear Island trough mouth fan. Glob. Planet. Change 12, 309–330 (1996).

Laberg, J. S., Andreassen, K., Knies, J., Vorren, T. O. & Winsborrow, M. Late Pliocene–Pleistocene development of the Barents Sea ice sheet. Geology 38, 107–110 (2010).

Patton, H. et al. Geophysical constraints on the dynamics and retreat of the Barents Sea ice sheet as a paleobenchmark for models of marine ice sheet deglaciation. Rev. Geophys. 53, 1051–1098 (2015).

Faleide, J. I. et al. Late Cenozoic evolution of the western Barents Sea–Svalbard continental margin. Glob. Planet. Change 12, 53–74 (1996).

Alexandropoulou, N. et al. A continuous seismostratigraphic framework for the Western Svalbard–Barents Sea margin over the Last 2.7 Ma: implications for the Late Cenozoic glacial history of the Svalbard–Barents Sea Ice Sheet. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 656732 (2021).

Rydningen, T. A. et al. An early Neogene—Early Quaternary contourite drift system on the SW Barents Sea continental margin, Norwegian Arctic. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2020GC009142 (2020).

Andreassen, K., Nilssen, L. C., Rafaelsen, B. & Kuilman, L. Three-dimensional seismic data from the Barents Sea margin reveal evidence of past ice streams and their dynamics. Geology 32, 729–732 (2004).

Andreassen, K., Nilssen, E. G. & Ødegaard, C. M. Analysis of shallow gas and fluid migration within the Plio-Pleistocene sedimentary succession of the SW Barents Sea continental margin using 3D seismic data. Geo-Mar. Lett. 27, 155–171 (2007).

Waage, M., Bünz, S., Bøe, R. & Mienert, J. High-resolution 3D seismic exhibits new insights into the middle-late Pleistocene stratigraphic evolution and sedimentary processes of the Bear Island trough mouth fan. Mar. Geol. 403, 139–149 (2018).

Nicholson, U. & Stow, D. Erosion and deposition beneath the Subantarctic Front since the Early Oligocene. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Tripsanas, E. K., Piper, D. J., Jenner, K. A. & Bryant, W. R. Submarine mass‐transport facies: new perspectives on flow processes from cores on the eastern North American margin. Sedimentology 55, 97–136 (2008).

Roger, J., Saint-Ange, F., Lajeunesse, P., Duchesne, M. J. & St-Onge, G. Late Quaternary glacial history and meltwater discharges along the Northeastern Newfoundland Shelf. Can. J. Earth Sci. 50, 1178–1194 (2013).

Cofaigh, C. Ó. et al. The role of meltwater in high-latitude trough-mouth fan development: the Disko Trough-Mouth Fan, West Greenland. Mar. Geol. 402, 17–32 (2018).

Hesse, R., Khodabakhsh, S., Klaucke, I. & Ryan, W. B. Asymmetrical turbid surface-plume deposition near ice-outlets of the Pleistocene Laurentide ice sheet in the Labrador Sea. Geo-Mar. Lett. 17, 179–187 (1997).

Hage, S. et al. How to recognize crescentic bedforms formed by supercritical turbidity currents in the geologic record: Insights from active submarine channels. Geology 46, 563–566 (2018).

Knies, J. et al. The Plio-Pleistocene glaciation of the Barents Sea–Svalbard region: a new model based on revised chronostratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 812–829 (2009).

sodir.no; https://factmaps.sodir.no/factmaps/3_0/ (Norwegian Offshore Directorate (Sokkeldirektoratet), Stavanger, Norway, 2024).

King, E. L., Haflidason, H., Sejrup, H. P. & Løvlie, R. Glacigenic debris flows on the North Sea Trough Mouth Fan during ice stream maxima. Mar. Geol. 152, 217–246 (1998).

Dowdeswell, J. A. et al. A major trough-mouth fan on the continental margin of the Bellingshausen Sea, West Antarctica: the Belgica Fan. Mar. Geol. 252, 129–140 (2008).

Cofaigh, Ó. et al. An extensive and dynamic ice sheet on the West Greenland shelf during the last glacial cycle. Geology 41, 219–222 (2013).

Sættem, J. et al. Cenozoic margin development and erosion of the Barents Sea: core evidence from southwest of Bjørnøya. Mar. Geol. 118, 257–281 (1994).

Forsberg, C. F. et al. 17. The depositional environment of the western Svalbard margin during the late Pliocene and the Pleistocene: sedimentary facies changes at Site 986. In Proc. Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results (Raymo, M. E., Jansen, E., Blum, P. & Herbert T. D.) Vol. 162, 233–246 (ODP, 1999).

Butt, F. A., Elverhøi, A., Solheim, A. & Forsberg, C. F. Deciphering Late Cenozoic development of the western Svalbard Margin from ODP Site 986 results. Mar. Geol. 169, 373–390 (2000).

Brigham-Grette, J. et al. Pliocene warmth, polar amplification, and stepped Pleistocene cooling recorded in NE Arctic Russia. Science 340, 1421–1427 (2013).

Balco, G. & Rovey, C. W. Absolute chronology for major Pleistocene advances of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Geology 38, 795–798 (2010).

Spielhagen, R. F. et al. Arctic Ocean evidence for late Quaternary initiation of northern Eurasian ice sheets. Geology 25, 783–786 (1997).

Sættem, J. et al. Glacial geology of outer Bjørnøyrenna, southwestern Barents Sea. Mar. Geol. 103, 15–51 (1992).

Kirkham, J. D. et al. Morphometry of bedrock meltwater channels on Antarctic inner continental shelves: implications for channel development and subglacial hydrology. Geomorphology 370, 107369 (2020).

Jordan, T. A. et al. Hypothesis for mega‐outburst flooding from a palaeo‐subglacial lake beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Terra Nova 22, 283–289 (2010).

MacRae, R. A. & Christians, A. R. A reexamination of Pleistocene tunnel valley distribution on the central Scotian Shelf. Can. J. Earth Sci. 50, 535–544 (2013).

Huuse, M. & Lykke-Andersen, H. Overdeepened Quaternary valleys in the eastern Danish North Sea: morphology and origin. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 1233–1253 (2000).

Stewart, M. A., Lonergan, L. & Hampson, G. 3D seismic analysis of buried tunnel valleys in the central North Sea: morphology, cross-cutting generations and glacial history. Quat. Sci. Rev. 72, 1–17 (2013).

Boyd, R., Scott, D. B. & Douma, M. Glacial tunnel valleys and Quaternary history of the outer Scotian shelf. Nature 333, 61–64 (1988).

Ehlers, J. Some aspects of glacial erosion and deposition in north Germany. Ann. Glaciol. 2, 143–146 (1981).

Mullins, H. T. & Hinchey, E. J. Erosion and infill of New York Finger Lakes: Implications for Laurentide ice sheet deglaciation. Geology 17, 622–625 (1989).

Bjarnadóttir, L. R., Winsborrow, M. C. & Andreassen, K. Deglaciation of the central Barents Sea. Quat. Sci. Rev. 92, 208–226 (2014).

Bjarnadóttir, L. R., Winsborrow, M. C. M. & Andreassen, K. Large subglacial meltwater features in the central Barents Sea. Geology 45, 159–162 (2017).

Canals, M., Urgeles, R. & Calafat, A. M. Deep sea-floor evidence of past ice streams off the Antarctic Peninsula. Geology 28, 31–34 (2000).

Piotrowski, J. A. Tunnel-valley formation in northwest Germany—geology, mechanisms of formation and subglacial bed conditions for the Bornhöved tunnel valley. Sediment. Geol. 89, 107–141 (1994).

Van der Vegt, P. A. A. M., Janszen, A. & Moscariello, A. Tunnel valleys: current knowledge and future perspectives. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 368, 75–97 (2012).

Kirkham, J. D. et al. Tunnel valley infill and genesis revealed by high-resolution 3-D seismic data. Geology 49, 1516–1520 (2021).

Bellec, V. et al. Bottom currents interpreted from iceberg ploughmarks revealed by multibeam data at Tromsøflaket, Barents Sea. Mar. Geol. 249, 257–270 (2008).

Bellwald, B., Planke, S., Piasecka, E. D., Matar, M. A. & Andreassen, K. Ice-stream dynamics of the SW Barents Sea revealed by high-resolution 3D seismic imaging of glacial deposits in the Hoop area. Mar. Geol. 402, 165–183 (2018).

Jansen, E., Fronval, T., Rack, F. & Channell, J. E. Pliocene‐Pleistocene ice rafting history and cyclicity in the Nordic Seas during the last 3.5 Myr. Paleoceanography 15, 709–721 (2000).

Melles, M. et al. 2.8 million years of Arctic climate change from Lake El’gygytgyn. NE Russ. Sci. 337, 315–320 (2012).

Bellwald, B. et al. Characterization of a glacial paleo-outburst flood using high-resolution 3-D seismic data: Bjørnelva River Valley, SW Barents Sea. J. Glaciol. 67, 404–420 (2021).

Rydningen, T. A., Laberg, J. S. & Kolstad, V. Seabed morphology and sedimentary processes on high-gradient trough mouth fans offshore Troms, northern Norway. Geomorphology 246, 205–219 (2015).

Batchelor, C. L., Ottesen, D. & Dowdeswell, J. A. Quaternary evolution of the northern North Sea margin through glacigenic debris‐flow and contourite deposition. J. Quat. Sci. 32, 416–426 (2017).

Bellwald, B. et al. Contourites of the Northern North Sea, North Sea Fan, and Mid-Norwegian Margin. In 83rd EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition Vol 2022, 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers, 2022).

Li, G., Piper, D. J. & Calvin Campbell, D. The Quaternary Lancaster sound trough‐mouth fan, NW Baffin Bay. J. Quat. Sci. 26, 511–522 (2011).

Passchier, S. et al. Pliocene–Pleistocene glaciomarine sedimentation in eastern Prydz Bay and development of the Prydz trough-mouth fan, ODP Sites 1166 and 1167, East Antarctica. Mar. Geol. 199, 279–305 (2003).

Elderfield, H. et al. Evolution of ocean temperature and ice volume through the mid-Pleistocene climate transition. Science 337, 704–709 (2012).

Rebesco, M. & Camerlenghi, A. Late Pliocene margin development and mega debris flow deposits on the Antarctic continental margins: evidence of the onset of the modern Antarctic Ice Sheet? Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 260, 149–167 (2008).

Laberg, J. S. & Vorren, T. O. Late Weichselian submarine debris flow deposits on the Bear Island Trough mouth fan. Mar. Geol. 127, 45–72 (1995).

Piper, D. J., Shaw, J. & Skene, K. I. Stratigraphic and sedimentological evidence for late Wisconsinan sub-glacial outburst floods to Laurentian Fan. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 246, 101–119 (2007).

Piper, D. J., Shaw, J., & Skene, K. I. Stratigraphic and sedimentological evidence for late Wisconsinan sub-glacial outburst floods to Laurentian Fan. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol, 246, 101–119 (2007).

Rebesco, M. et al. Onset and growth of trough-mouth fans on the north-western Barents Sea margin—implications for the evolution of the Barents Sea/Svalbard ice sheet. Quat. Sci. Rev. 92, 227–234 (2014).

Laberg, J. S., Andreassen, K. & Vorren, T. O. Late Cenozoic erosion of the high-latitude southwestern Barents Sea shelf revisited. Bulletin 124, 77–88 (2012).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene–Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, 1 (2005).

Acknowledgements

TGS is acknowledged for providing access to seismic 3D data, for using their Facies Map Browser (FMB) and for permission to publish the examples shown in this study. More details about the seismic and well data: https://www.tgs.com/. This work has been supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 860383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. is the main author of the paper and led the analysis and interpretation of the seismic data, integrated the data, produced the figures with input from all authors, developed the core concepts of this study and wrote the manuscript. D.M. conducted analysis and interpretation of the 3D reflection seismic data, and supported work with the well ties. S.P. helped in seismic data analysis and contributed toward the development of the core concepts of this study. M.W., T.A.R., and N.A. contributed to the interpretation of ice-sheet dynamics, sedimentary deposits, and chronology. R.M. was involved in data collection and provided access to the 3D seismic data. All authors contributed to writing the paper and suggested figure improvements.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Michele Rebesco, Aleksandr Montelli, and Kelly Hogan for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joe Aslin. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bellwald, B., Maharjan, D., Planke, S. et al. Major tunnel valleys and sedimentation changes document extensive Early Pleistocene glaciations of the Barents Sea. Commun Earth Environ 5, 551 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01688-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01688-x