Abstract

Low atmospheric oxygen levels during the mid-Proterozoic were occasionally interrupted by transient high oxygen levels. The cause of mid-Proterozoic ocean redox variability remains unclear. Here we investigate mercury chemostratigraphy across the Jixian section of North China Craton through two oxygenation intervals. Abnormal spikes in mercury concentration and excursions of mercury isotopes are observed in the Dahongyu and Hongshuizhuang formations, which occur just below the two oxygenation intervals, respectively. These mercury anomalies suggest that the two oxygenation events were preceded by subaerial volcanism. Furthermore, the two oxygenation intervals show increased nutrient concentrations and negative shifts in mercury isotopes, indicating that enhanced weathering and terrestrial nutrient influx occurred during oxygenation intervals. We infer that in the breakup setting of the Columbia supercontinent, large igneous province volcanism and its efficient low-latitude weathering could rapidly increase terrestrial nutrient influx into the ocean, promoting oceanic productivity and a pulsed rise in oxygen levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

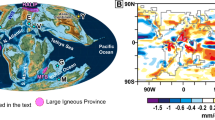

The mid-Proterozoic interval (1.8 to 0.8 billion years ago [Ga]) has long been recognized as a phase of environmental and biological stasis. Geochemical studies have suggested a generally low atmosphere oxygen partial pressure (pO2) during the mid-Proterozoic, perhaps <0.1% present atmospheric level (PAL; ref. 1). However, growing evidence supports that the redox state of the mid-Proterozoic was likely dynamic, with several intervals of high oxygen levels that punctuated overall low background levels2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The earliest evidence comes from geochemical records of redox-sensitive trace metals (Mo, U, V) in the ca. 1.4 Ga Xiamaling Formation on the North China Craton (NCC)3. Subsequently, ocean-atmosphere oxygenation during the earlier depositional periods of both the Gaoyuzhuang (1.60–1.55 Ga) and Tieling (1.45–1.42 Ga) formations also in NCC have been suggested based on the carbonate I/(Ca+Mg) value proxy, which is one of the few available indicators that can semi-quantitatively trace the redox state of carbonate sedimentary environments4,5. Recent results on Ce anomalies and δ53Cr isotopes of Tieling and Gaoyuzhuang formations have been broadly consistent with previous results for carbonate I/(Ca + Mg), providing more independent evidence of atmospheric oxygenation6,7. According to the Raman spectroscopic analysis of organic matter in black shales from the Gaoyuzhuang and Xiamaling formations, as well as the Shennongjia Group, the recycled graphite carbon was very rare, further constraining atmospheric oxygen contents to be 2–24% PAL from 1.73 to 0.74 Ga (ref. 8). Although these oxygenation events are currently only documented from the Yanliao Basin, northeast NCC (Fig. 1), the high I/(Ca + Mg) values up to 3.5 μmol/mol from multiple sections7 and positive δ53Cr values up to 0.66‰ (ref. 5), as well as the open-basin setting of the Yanliao Basin strongly suggest an increase of atmospheric O2 of global, not merely local, significance2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Therefore, emerging diverse geochemical indicators suggest that at least three oxygenation intervals occurred at 1.59–1.56, 1.44–1.43, and 1.40–1.36 Ga (refs. 2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9), which may have been sufficient to fuel the respiration of multicellular eukaryotes during the mid-Proterozoic3.

a Distribution of 1.6–1.3 Ga and 1.3–1.2 Ga LIP and 1.8–1.0 Ga extensional basins in a paleogeographic reconstruction map of supercontinent Columbia (Nuna)43, red box marks the North China craton. b Distribution of the mid-Proterozoic extensional basins in North China Craton5,6. c Regional map of the Proterozoic outcrop within the Yanliao Basin, showing the position of the Jixian section.

Although enhancing organic carbon/pyrite burial has generally been recognized as the most effective way to increase oxygen in the Earth’s surface environment11, the causes of these pulsed oxygenation events are still controversial. Existing views include increasing oceanic productivity due to elevated nutrient (including P, and micronutrients Cu, Zn, and Ni) flux from upwelling12 or continental erosion due to strong weathering9 or regional climate dynamics13. A root cause for these environmental perturbations may be large igneous province (LIP) eruptions, which could trigger changes in biogeochemical dynamics and evolutionary pathways14. Abundant greenhouse gases and mafic magma can be released at the surface during LIP eruptions, which would increase global temperature, resulting in a cascade of events including increased silicate weathering, terrestrial nutrient supply into the ocean, oceanic productivity, organic matter burial, and oxygenation15,16. Recent research has suggested a close relationship between mid-Proterozoic LIP events and environmental disturbance through Hg isotopic analyses of 1.4 Ga tropical offshore sediments of the Xiamaling Formation17. However, the details and strength of the potential causal relationship between mid-Proterozoic LIP events and environmental disturbances remains enigmatic.

Mercury (Hg) is a useful proxy for Earth’s surface environment evolution and LIP eruptions, because volcanic emissions are the primary source of Hg in the environment besides wildfire combustion of vegetation18. Volcanic Hg can be transported globally in the atmosphere prior to deposition, thus anomalously high Hg concentrations in sedimentary records are typically linked to environmental perturbations driven by LIP eruptions9,17,18,19. In addition, Hg isotopes undergo both mass-dependent fractionation (MDF, expressed as δ202Hg) and mass-independent fractionation (MIF; usually expressed as Δ199Hg), which provide useful constraints on Hg sources and geochemical processes20. Hg(II) photoreduction results in negative Δ199Hg values in the product Hg(0), leaving the residual Hg(II) with positive Δ199Hg values21. Modern marine reservoirs (e.g., marine sediments and seawater) mainly exhibit positive Δ199Hg values derived from the deposition of atmospheric Hg(II) species22. Modern terrestrial reservoirs (e.g., vegetation and soil) predominately show negative Δ199Hg values, due to vegetation uptake of gaseous Hg(0) followed by deposition of vegetation-derived Hg through litterfall23. Excursions of Δ199Hg in sediments have often occurred during LIP eruptions due to changes in Hg transport pathways to the ocean from LIP-driven environmental perturbations17,18,24.

The biogeochemical cycling of Hg in the Precambrian is still poorly constrained. Only a few studies have reported anomalous Hg concentrations and isotopic ratios in limited stratigraphic sections corresponding to Gaoyuzhuang and Xiamaling oxygenation intervals9,17, highlighting the potential role of large volcanism in triggering the oxygenation events. A lack of research on Hg in sedimentary sequences covering the full extent of the mid-Proterozoic currently limits our understanding of the connection between volcanism and oxygenation events. Here, we present Hg concentration and isotopic composition data across the mid-Proterozoic Jixian Section in the Yanliao Basin, North China Craton (Fig. 1), to gain insights into the geochemical cycle of Hg in the mid-Proterozoic and the potential link between oxygenation events and volcanism.

Results

In the Jixian section (Supplementary Table 1), the micronutrients Cu, Zn, and Ni exhibit concentrations (enrichment factors) of 0.7–357 ppm (0.03–12.4), 0–361 ppm (0–7.9), and 0–114 ppm (0–5.7), respectively. P concentrations range from <10 to 4620 ppm, yielding P/Al from 15–1413 ppm/wt.% (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Table 2). The Cu, Zn, and Ni enrichment factors, along with P and P/Al, are relatively high across the oxygenation intervals marked by high I/(Ca + Mg) (Fig. 2a–c).

a I/(Ca + Mg) (data sources in refs. 6,7); (b) enrichment factors of Cu, Zn, and Ni; (c) P concentration (ppm) and ratio of P/Al (ppm/wt%); (d) Hg content (ppb); (e) TOC (wt%) and ratio of Hg to TOC (ppb/wt%); (f) Al content (wt%) and Hg to Al (ppb/wt%); (g) Fe content (wt%) and Hg to Fe (ppb/wt%); (h) Mn content (ppm) and Hg to Mn (ppb/wt%). The rock lithology, thickness, and age data are cited from refs. 30,32.

Hg concentrations are highly variable throughout the Jixian section (0.84–192 ppb, mean 11 ppb; Fig. 2d). Most of the samples show low Hg concentrations around a baseline of ~3 ppb (ref. 14). However, two Hg spikes, with Hg concentrations up to 31.2 ppb and 192 ppb, were observed in the Dahongyu and Hongshuizhuang formations, just prior to the onset of the Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals, respectively. Also, total organic carbon (TOC) content in the Jixian section varies greatly (0.36–8.15 wt.%, Fig. 2e), and generally shows elevated levels in the oxygenation intervals. As Hg has a strong affinity to organic matter, Hg/TOC ratios are used to assess the validity of true Hg anomalies18. In this study, two Hg/TOC spikes, corresponding to the locations of two Hg concentration spikes, were observed just prior to the onset of Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals, respectively (Fig. 2e). Similarly, Hg/Al (Al > 0.3 wt%), Hg/Fe, and Hg/Mn show clear peaks just prior to the onset of oxygenation intervals (Fig. 2f-h). Moreover, the intervals with high I/(Ca + Mg) have higher Rb/Al values (up to 33 ppm/wt%) (Fig. 3a), suggesting an incongruent dissolution of biotite and other mica minerals from fresh volcanic rocks25.

a ratio of Rb/Al (ppm/wt%), (b) Δ199Hg (‰), (c) Δ200Hg (‰), (d) δ202Hg (‰). Lithologic legend as in Fig. 2.

The overall variation of Δ199Hg for the samples is 0.43‰ (–0.34 to 0.09‰; Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 3), ~7 times the analytical uncertainty of ±0.06‰ (2 SD) for Δ199Hg. Δ200Hg values range from –0.11 to 0.09‰ (Fig. 3c), yielding a variation of 0.20‰, ~3 times the analytical uncertainty of ±0.06‰ (2 SD) for Δ200Hg. A large variation of 0.36‰ in Δ201Hg (–0.32 to 0.04‰; Fig. 4a) is also observed in the samples studied, which is ~5 times the analytical uncertainties for Δ201Hg (±0.08‰; 2 SD). The overall variation of δ202Hg for the samples is 2.65‰ (–2.48 to 0.17‰; Fig. 3d), ~16 times the analytical uncertainty of ±0.16‰ (2 SD) for δ202Hg. Despite 5 samples that display Δ199Hg values of close to 0.05‰, most of the samples studied show strongly negative Δ199Hg values (–0.34 to –0.02; Fig. 3b). A strong positive correlation between Δ199Hg and Δ201Hg (r2 = 0.75), with a Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratio of ~1, is observed for our samples (Fig. 4a).

a Δ199Hg vs Δ201Hg, and (b) Δ199Hg vs Δ200Hg for Jixian Section samples. Experimental studies of aqueous solutions with natural organic matter have demonstrated that photochemical reduction of Hg(II) yields residual Hg(II) with a Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratio of 1 (ref. 21), whereas measured natural samples plot within analytical uncertainty of the bounding Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratios of 1.00 and 1.36 (ref. 20). Data of Hongshuizhuang Formation are from ref. 19. Analytical uncertainties (2 SD) for the data are 0.08‰ for Δ201Hg and 0.06‰ for Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg.

Discussion

Aqueous Hg(II) photoreduction as a major cause of Hg-MIF in the mid-Proterozoic

Research into Hg isotopes has demonstrated Hg-MIF in the modern atmosphere-land-ocean system, with a Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratio of ~1, arguing for a vital role for aqueous Hg(II) photoreduction in governing the global Hg biogeochemical cycle20. The consistency of Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg for our samples (Fig. 4a) and aqueous Hg(II) photoreduction experiments21 confirms aqueous Hg(II) photoreduction as a potentially leading cause of Hg-MIF in the mid-Proterozoic. Therefore, the variation of Δ199Hg values in our samples may be partially explained by analogy to modern examples. Positive Δ199Hg values, with Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg of ~1, have been observed in Precambrian marine/offshore sediments (e.g., shale), which have been explained by the deposition of atmospheric Hg(II) (refs. 17,19,26,27). From a mass-balance point of view, an unrecognized Hg pool characterized by negative Δ199Hg values should exist in the Precambrian. The overall negative Δ199Hg values observed in the Jixian samples provide a clue to this missing pool. A recent study attributed negative Δ199Hg values of Precambrian sedimentary rocks to be caused by sulfur-bound Hg(II) photoreduction under euxinic conditions in the photic zone28. However, this process may be difficult to explain the oxygenation and volcanism intervals, and even the overall negative Δ199Hg values observed in the Jixian section require the existence of a long-term photic zone euxinia. Instead, according to the carbonate δ238U isotopes from the Gaoyuzhuang, Wumishan, and other formations, the estimated extent of the global euxinic seafloor from 1.8–0.8 Ga is <7% (ref. 29). Although oxidation of atmospheric Hg(0) by low-molecular-weight organic compounds may explain negative Δ199Hg in late Archean sediments26, the presence of organic compounds or organic haze could have limited further Hg-MIF formation in the Proterozoic by limiting the penetration of ultraviolet radiation and inhibiting the photochemical reactions of Hg.

The Jixian samples (conglomerate, sandstone, shale, dolomite, and limestone) mainly reflect shallow water depositional environments that received a large amount of terrigenous clastic material via continental erosion30,31,32. In modern oceans, coastal sediments mostly show negative Δ199Hg values due to riverine input of terrestrial Hg, as terrestrial materials have negative Δ199Hg (refs. 18,23,24). Hence, the results of this study could suggest a terrestrial Hg pool characterized by negative Δ199Hg values existed during the mid-Proterozoic. Although studies have demonstrated a few lichen records in the mid-Proterozoic33, there was a lack of abundant vascular plants on land during the Precambrian34. Therefore, gaseous Hg(0) with negative Δ199Hg taken up by vegetation in the limited mid-Proterozoic terrestrial biosphere is an unlikely explanation for the negative Δ199Hg values observed in our samples.

An alternative explanation for negative Δ199Hg values is that the Precambrian Hg cycle was largely controlled by abiotic transformations in the atmosphere-land-ocean system. One analogy is the modern polar environment, where vegetation is scarce and atmospheric mercury depletion events (AMDEs) occur during spring ice melting35,36. During AMDEs, melting of sea ice results in extensive emission of halides (e.g., Br and Cl) from seawater to the atmosphere, which efficiently oxidizes gaseous Hg(0) to Hg(II), causing accumulation of Hg in polar snow with negative Δ199Hg (down to –5.50‰; ref. 35). Negative Δ199Hg (i.e., –0.50‰) has also been measured in Antarctica aerosols containing mainly Hg(II) species36, supporting the oxidation of gaseous Hg(0) during AMDEs. The Precambrian land may have served as a net sink of atmospheric Hg(0) due to the oxidation of gaseous Hg(0) by atmospheric oxidants (such as OH-, halides, and potentially low-molecular-weight organic compounds) emitted from the ocean or volcanism26,37. Such oxidation processes can reduce the lifetime of atmospheric Hg, as the product Hg(II) has a residence time of ~10 days in the atmosphere, being readily adsorbed on atmospheric particles and deposited onto the terrestrial surface35.

Overall, the negative Δ199Hg values we observe in nearshore sedimentary rocks imply that the Precambrian land was a net sink of atmospheric Hg(0), even without vegetation. The magnitude of negative Δ199Hg values in nearshore sedimentary rocks can thus serve as a useful proxy for the influx of terrestrial material into Precambrian oceans.

Host phase of Hg enrichment intervals on the eve of two oxygenation intervals

Although most of Hg concentrations at the Jixian section are lower than the average for Phanerozoic sedimentary rocks18, they all show a distinctive increasing trend through the intervals just prior to Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals. Two main Hg peaks occur, peak1 in the Dahongyu Formation (from 4 to 31 ppb) right before the onset of the Gaoyuzhuang oxygenation interval and peak2 in the Hongshuizhuang Formation (from 3 to 192 ppb) right before the onset of the Tieling oxygenation interval (Fig. 2d). A positive correlation between Hg and TOC can be observed in most marine sediments, due to the adsorption of Hg by organic-rich particles18. Reduced sulfur compounds18,38 and, more rarely, clay minerals39 or Mn-Fe-oxides40 can also be important Hg host phases, making it essential to determine formation-specific Hg host phases when using Hg as a volcanic proxy. The correlations between Hg and TOC, TS, Al contents, and Mn-Fe-ox values were used to assess the main host phase of Hg in previous studies17,18,19,38.

In the Dahongyu Formation (Hg peak 1), a positive correlation (r2 = 0.65) is observed between Hg and Al concentrations (one exception; Fig. 5a). In contrast, we did not observe correlations between TOC and Hg contents (Fig. 5b) and between Hg and Mn-Fe-ox (Fig. 5c, d). This suggests that clay minerals are likely the dominant host of Hg in the Dahongyu Formation. In the Hongshuizhuang Formation (Hg peak 2), we observed a negative correlation (Fig. 5e) between Hg and Al contents, but positive correlations between Hg and TOC (r2 = 0.53) and TS (r2 = 0.47) contents (Fig. 5e, f). These results indicate that Hg in the Hongshuizhuang Formation was mainly scavenged from seawater by organic matter, followed by sulfide19. Changes in redox conditions can also affect Hg accumulation in sediments41. Samples from the Hongshuizhuang Formation show a very strong positive correlation (r2 = 0.89) between Hg and Mo (Fig. 5h), suggesting that increased Hg levels were possibly driven by enhanced anoxic conditions19,38. Under anoxic conditions, organic matter burial is promoted, and therefore greater amounts of Hg can be removed from the water column18, although this would not change the Hg/TOC ratios, and without increased Hg availability, this would lead to eventual Hg depletion in the water column.

a, e Hg concentrations (ppb) versus Al concentrations (wt%); (b) and (f) Hg concentrations (ppb) versus TOC concentrations (wt%); (c) Hg concentrations (ppb) versus Fe-ox; (d) Hg concentrations (ppb) versus Mn-ox; (g) Hg concentrations (ppb) versus TS concentrations (wt%); (h) Hg concentrations (ppb) versus Mo concentrations (ppm). Other data: Hongshuizhuang Formation19.

Large volcanism on the eve of the two oxygenation intervals

Several factors can contribute to sedimentary Hg enrichments. However, changes in lithology cannot explain the Dahongyu and Hongshuizhuang Hg concentration peaks, as most of the samples studied show varying lithology but consistently low Hg concentrations (<10 ppb). It has also been estimated that a ~ 5- to 10-fold reduction in deposition rate may generate a measurable Hg enrichment42. Based on the high-resolution stratigraphic framework of the Jixian Group (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 1), the average deposition rate during the Hongshuizhuang Formation (~10 Myr and ~131 m) is estimated to be ~ 13 m/Myr. This deposition rate is just ~3-fold lower than ~42 m/Myr in the Wumishan Formation (~80 Myr and ~3,336 m), suggesting that changes in the deposition rates may not explain the temporal variations in Hg concentration. Although we cannot estimate changes in deposition rates between the Gaoyuzhuang and Dahongyu formations, due to the lack of accurate thickness and age data, the difference must be minor compared to that between the Dahongyu dolostone and the Tuanshanzi dolostone.

Hg enrichment in marine sediments is generally related to either excessive Hg inputs to the basin (e.g., volcanism, hydrothermal venting, and terrestrial erosion) or increased burial efficiency of Hg into the sediments17,18,19,22,23,43. The positive correlation between Hg and Al concentrations (r2 = 0.65; Fig. 5a) suggests that clay minerals are the main host of Hg in the Dahongyu Formation. After normalizing Hg contents with Al contents, the Hg/Al (ppb/wt%) show a clear increase (0.6–6.1 ppb/wt%) during the Hg enrichment interval, suggesting that Hg enrichment is not solely caused by enhanced burial of clay minerals, but is also linked to an increased Hg flux to the ocean. Hg in the Hongshuizhuang Formation was mainly scavenged from seawater by organic matter, followed by sulfide (Fig. 5f, g). After normalizing Hg contents with TOC contents, the Hg/TOC (ppb/wt%) show a remarkable increase (214–27,400 ppb/wt%) during the Hg enrichment interval, suggesting that Hg enrichment is linked to an excessive Hg flux to the ocean.

Volcanoes are a primary source of Hg to the global atmosphere, and large-scale volcanic activity has caused important Hg deposition events in the world’s oceans with subsequent sequestration in marine sediments17,18,24,37. Lithologically, there are volcanic rocks in the Dahongyu Formation, providing direct evidence of volcanism throughout that interval (Fig. 2). A similar increase in Hg concentrations (from 3.7 to 10.5 ppb) has been observed in the Tuanshanzi Formation also containing volcanic layers (Fig. 2d). The broad stratigraphic correspondence of Hg enrichment to volcanic activity suggests that volcanism may have played a major role in Hg enrichment in both the Dahongyu and Tuanshanzi formations.

Hg isotopes (Hg-MIF and Hg-MDF) can provide more clear constraints on the Hg sources26,27,36,37,38. Previous studies have shown that Hg isotopic excursions in sediments often occur during LIP eruptions17. Although δ202Hg is subject to multiple mass-dependent influences related to physical, chemical, and biological processes20, positive δ202Hg excursions can be observed in each of the Hg enrichment intervals in the Tuanshanzi, Dahongyu, and Hongshuizhuang formations, respectively (Fig. 3f). This is similar to that observed in the ca. 2.5 Ga lower Mt. McRae Shale, which received abundant subaerial volcanic Hg (ref. 27).

Hg-MIF is caused primarily via photochemical reactions without interference from other processes20, therefore, it can provide more direct constraints on the Hg sources. Throughout the Hg enrichment intervals of the Tuanshanzi, Dahongyu and Hongshuizhuang formations, Δ199Hg shows a shift toward more positive values consistent with a volcanic contribution18,27 (Fig. 3d). Hg chemistry studies suggest that the isotopic signature of large-scale subaerial volcanism has a slightly positive Δ199Hg resulting from the photoreaction of fresh volcanogenic Hg(0) leading to atmospheric deposition of Hg(II) carrying a positive Δ199Hg signature18,20. Although the maximum Δ199Hg value does not correspond to the maximum Hg value, it is obvious that during the Hg spike intervals, the Δ199Hg value shows a steadily increasing trend (Fig. 3b). The increase of Δ199Hg during the Hg spike interval may be linked to one or both of the following processes: (1) a dominant contribution of direct atmospheric deposition of volcanically derived Hg (II), and/or (2) increases in organic matter content which effectively captures Hg (II) with positive Δ199Hg signals. The first process seems the most reasonable in our study, as the second process is not supported by the strong correlations between Hg and TOC concentrations (Fig. 5b, f). This is further supported by the presence of an obvious variation of Δ200Hg for the samples in Hg enrichment intervals of the Dahongyu and Tuanshanzi formations (from –0.11‰ to 0.04‰), as well as those of the Hongshuizhuang Formation (this study: from –0.10‰ to 0.06‰; previous study19: from –0.12‰ to 0.11‰; Figs. 3e and 4b). Since Δ200Hg anomalies are exclusively produced via photochemical oxidation processes in the stratosphere20,44, the obvious variation of Δ200Hg observed in these samples (Fig. 4b) also implies that Hg-MIF signals were mainly formed in the upper atmosphere. Moreover, we note that obvious Δ200Hg anomalies and positive Δ199Hg are found in Archean and Phanerozoic strata with Hg that has a volcanic origin (Supplementary Fig. S1a, c). Instead, temporally equivalent strata with Hg of terrestrial origin generally lack these features (Supplementary Fig. S1b, d). Given this, we suggest that LIP volcanism is the source of excess Hg on the eve of Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals, providing a clue to the cause of the oxygenation events.

Linkage between LIPs and dynamic redox

In the Precambrian, atmospheric pO2 and oceanic productivity were coupled through photosynthesis, with P being a major limiting nutrient45. In addition, primary productivity in the euphotic zone was significantly controlled by the availability of other micronutrients (e.g., Cu, Zn, and Ni) in seawater46, which are ultimately buried in sediments with sinking organic matter; therefore, their sedimentary enrichments can be used to infer original productivity12,17. Nutrient enrichment factors in the studied samples show a good coupling relationship with oxidation intervals calibrated by the I/(Ca+Mg) as shown in Fig. 2a–c. This coupling is evident during the Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals, indicating the crucial role of nutrients in Proterozoic oxygenic photosynthesis. Notably, nutrient enrichment factors are high during the volcanism of the Tuanshanzi, Dahongyu, and Hongshuizhuang formations, which record low atmospheric oxygen levels. This correspondence provides further evidence of a causal relationship between volcanism and oxygenation, because initial volcanism may have not only supplied nutrient flux from ash loading47, but also may have released reducing gases, such as CO or H2S (Fig. 6b), that act as O2 sinks27,48. Such gas emissions and ash fall fertilization mechanisms are short-lived compared to the much longer effect of the weathering of fresh volcanic rock. The cessation of intense volcanism would thus have switched off this kinetically rapid O2 sink, thereby promoting O2 accumulation27.

a pre-LIP eruptions, (b) syn-LIP eruptions, and (c) post-LIP eruptions. Photoreduction of Hg(II) produces gaseous Hg(0) with negative Δ199Hg values and gaseous Hg(II) with positive Δ199Hg values. Gaseous Hg(II) is readily deposited into the marine reservoir (light blue area), whereas gaseous Hg (0) is preferentially oxidized to Hg(II) species by the reactive halogen compounds and low-molecular-weight organic compounds (purple dotted arrow). In the Proterozoic, the absence of vegetation would have led to frequent dust storms on land, increasing the possibility to trap gaseous Hg(II) and deliver this Hg onto the terrestrial surface, and thus the settled atmospheric Hg(II) with negative Δ199Hg was mostly preserved on terrestrial systems. Although some of this Hg(II) can enter the ocean, the negative Δ199Hg signals would be diluted by the abundant Hg with positive Δ199Hg in oceanic reservoirs. The red color represents LIP volcanic emissions, including ash, Hg(0), reducing gases and greenhouse gases. This LIP volcanic Hg (Δ199Hg ~ 0‰ and Δ200Hg ~ 0‰) has been the primary source of Hg to the Earth’s surface over geologic history and can yield Δ200Hg anomalies via photochemical processes at the stratosphere (blue dotted arrow). The huge scale of basaltic fissure eruptions of the LIP was capable of injecting ash into the stratosphere. Such basaltic ash is more reactive than silicic ash, ensuring a short-lived and substantial nutrient flux from ash loading which may promote oceanic productivity and O2 release. However, the O2 was quickly consumed by the reducing gases released by LIP volcanoes, resulting in no rise in atmospheric O2 levels. The cessation of LIP volcanism would thus have switched off this ash fall fertilization mechanism and the kinetically rapid O2 sink. Abundant greenhouse gases released from the mid-Proterozoic LIP volcanism would lead to greenhouse climates and abundant acid rain, further accelerating the chemical weathering of mid-Proterozoic LIP, and may facilitate an unprecedented flux of bioavailable nutrients to the ocean, thus triggering oxidation of the ocean-atmosphere system. Note: atmospheric pO2 < 0.1% is cited from ref. 1; atmospheric pO2 > 4% is cited from refs. 3,6,7.

Nutrients (such as P, Cu, Zn, Ni) are mainly derived from terrestrial runoff over geological timescales and have a profound impact on the redox state of Earth’s surface14,15,16,17,49. However, intense open-marine upwelling events may similarly drive high productivity by importing excess nutrients to the photic zone12,50. As discussed above, similar to the present day, continental reservoirs mainly show negative Δ199Hg values, while marine reservoirs mainly exhibit positive Δ199Hg values, which provides a clear constraint on the source region of abundant nutrients. A recent investigation revealed that open ocean upwelling of nutrient-rich waters shows positive Δ199Hg values of 0.13–0.24‰ and positive Δ200Hg values of 0.05–0.10‰ (ref. 50). Our data from the Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals show relatively weak Hg enrichment paired with significant negative Δ199Hg (–0.33 to 0.03‰), consistently suggestive of a terrestrial origin.

Factors potentially increasing terrestrial nutrient influx into the ocean include climate, high continental surface topography, land colonization, and the composition of exposed continental crust13,16,17. Previous studies showed that the total length of Mesoproterozoic orogenic belts was short51, and crustal thickness was at a minimum52. Therefore, orogenic activity was unlikely strong enough to cause enhanced nutrient influx to the ocean during the mid-Proterozoic. Colonization of vegetation on land may have facilitated continental weathering, causing fertilization of the ocean and promoting O2 production, such as proposed for the Neoproterzoic53. However, carbon isotope studies on carbonates suggest that large-scale land colonization propagated sometime after 850 Ma (ref. 54), thus, this mechanism cannot be a leading driver of the sharp increase in nutrient flux and transient oxygen production observed. Given these constraints, we propose that changes in climate and continental surface composition are responsible for increasing terrestrial nutrient influx into the ocean during the mid-Proterozoic. Although the Changcheng Group deposited before volcanism initiated received large amounts of continental material, Cu, Zn, and Ni enrichment factors and P/Al ratios were relatively low (Fig. 2b, c). This observation indicates that the continental surface contributed limited nutrients to the oceans prior to the volcanism, limiting as well marine primary productivity at that prior time17.

Throughout geological history, LIP volcanism not only released abundant greenhouse gases (CO2, SO2, etc.) and massive Hg to the atmosphere17,18,27,37, but also produced abnormally large volumes of basaltic magma, which repeatedly covered the continental surface and changed the surface composition14,15,16 (Fig. 6b). The two Hg concentration spikes we identify are coeval with multiple LIPs in neighboring Australia, Siberia, and Laurentia14 (e.g., the 1.63 Ga Melville–Bugt and 1.59 Ga Gawler Range LIPs, and the 1.47 Ga Moyie and 1.46 Ga Lake Ladoga LIP). Thus, we suggest that the intensified weathering of LIP basalts was the critical constraint of the dynamic redox in the mid-Proterozoic oceans, based on the following facts: (1) they occur after our Hg evidence for a LIP event, and (2) Most mid-Proterozoic LIPs were positioned close to the equator13,43,55 where chemical weathering would be most intense. Thus, the abundant basalt erupted by LIP volcanism provides a material basis for contributing nutrients to the ocean through strong chemical weathering under the warm and wet tropical paleoclimate9,17. (3) Abundant greenhouse gases (CO2, SO2, etc.) released from the mid-Proterozoic LIP volcanism would lead to greenhouse climates and abundant acid rain, further accelerating the chemical weathering of LIP basalts24,56, thus increasing nutrient flux to the ocean (Fig. 6c). Intensified weathering during the Gaoyuzhuang and Tieling oxygenation intervals is further supported by high Rb/Al ratios of fine-grained sediments (Fig. 4a), which are seen as a reliable proxy for chemical weathering intensity9,25.

Conclusions

Long-term Hg chemostratigraphic variations in the Jixian section may reveal the dynamic redox history in the mid-Proterozoic oceans. Our data from the Jixian section documented two seemingly compelling cases of the causal link: pulses of LIP volcanism, followed by pulses of atmospheric oxygen. Therefore, it is proposed that LIP played a major role in oceanic oxygenation events during the mid-Proterozoic. We admit that there is an intricate web in the causal relationship between LIP volcanism and oxygenation events; that is, not every LIP eruption will lead to a change in Earth’s surface redox state, and even if LIP volcanic activity triggered oxygenation events, the lag time may be short17 or slightly longer (this study). These differences may be related to the scale of LIP volcanism or its paleogeographic location and geodynamic background, thus, more data and future studies are needed to quantify them.

Methods

Study section

Thick Meso-Neoproterozoic sedimentary sequences were developed in the Yanliao Basin, North China Craton, in response to the breakup event of the Columbia (Nuna) supercontinent30,31,32,57 (Fig. 1a and b). Among them, the Jixian section in the middle of the Yanliao Basin contains the well-preserved sedimentary record of the mid-Proterozoic, which, from bottom to top, can be divided into 4 groups and 12 formations2,30,31,32 (Fig. 2): Changcheng Group (Changzhougou, Chuanlinggou, Tuanshanzi and Dahongyu formations), Jixian Group (Gaoyuzhuang, Yangzhuang, Wumishan, Hongshuizhuang and Tieling formations), undetermined Group (Xiamaling Formation and missing stratum), and Qingbaikou Group (Luotuoling and Jingeryu formations). The sedimentary sequence of the Jixian section was deposited in shallow subtidal to intertidal environments of the epicontinental sea, which consists of essentially undeformed sedimentary rocks30,31,32. Based on zircon U-Pb ages from tuffs, flows, and dykes, the age of the bottom boundary of the Jixian section has been redefined, and most stratigraphic groups/formations have obtained accurate chronological constraints30,31,32, thus establishing a high-resolution stratigraphic framework. Meanwhile, geochemical evidence (e.g., I/(Ca+Mg); Fig. 2a) showing notable atmosphere-ocean oxygenation has been widely observed in the Gaoyuzhuang, Tieling and Xiamaling formations2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

A total of 56 fresh rock samples (conglomerate, sandstone, shale, dolomite and limestone; Supplementary Table 1) were collected from all 4 groups and 12 formations in the Jixian Section for major elements, trace elements (Supplementary Table 2), total organic carbon (TOC), Hg concentrations analysis. Based on TOC and total Hg concentrations, 29 samples were further chosen for Hg isotope composition analyses (Supplementary Table 3).

Elemental analyses

Major element (Fe, Al, Si, Mn, P) analyses of these samples were conducted at ALS Chemex Co., Ltd., China, using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF), with an analytical uncertainty of better than 3% for the elements >1 wt% and 10% for elements <1 wt%. Trace element (Mo, U, V, Cu, Zn, Ni, Rb, and Th) analyses of these samples were based on Agilent 7900 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGCAS), with analytical uncertainty of better than 5% for the trace elements reported.

To eliminate potential influences from changes in lithology or the detrital fraction, P/Al (ppm/wt%) ratios and Cu-Zn-Ni enrichment factors (EFs), rather than the absolute concentrations, were used to assess paleoproductivity. Comparatively immobile elements such as Al and Th are rarely influenced by diagenetic or biogenic processes and, thus, are good proxies for the detrital siliciclastic fraction of the sediment58. Trace-metal enrichment factors (EFs) are calculated as:

where X and Al represent the concentrations of elements X and Al, respectively, and PAAS is Post-Archean Average Shale58.

Detrital and authigenic Fe-Mn oxyhydroxides (Mn-ox and Fe-ox) that accumulate in oxic sediment layers can also be important scavengers of Hg59. Mn-ox and Fe-ox were calculated as:

where the Mn-ox and Mntotal represent the oxide fraction and total Mn in each sample (Fe-ox was calculated in a similar manner). (Mn/Al)PAAS represents the ratio of Mn to Al in PAAS.

TOC content was determined using an Elemental analyzer (Elementar vario MACRO cube, Germany), after the samples were treated with 2 mol/L HCl for carbonate removal. The precision of TOC measurements is <0.3% absolute error. generally better than 0.3% based on standard and duplicate samples. Total Hg concentrations of the samples were measured using a DMA-80 Hg analyzer, with Hg detection limit of 0.01 ng/g. Measurements of standard reference material (GSS-4 and GSS-5) showed recoveries of 90 to 110%. The coefficients of variation for triplicate analyses were <10%.

Hg isotope analysis

For Hg isotope analysis, the samples were prepared using double-stage thermal combustion and pre-concentration protocol26. Standard reference material (GSS-4) and method blanks were prepared in the same way as the samples. The former yielded Hg recoveries of 90–100% and the latter showed Hg concentrations lower than the detection limit (0.05 ng Hg), precluding laboratory contamination. The preconcentrated solutions were diluted to 1 ng/mL Hg and measured by a Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS)60.

Hg-MDF is expressed in δ202Hg notation in units of ‰ referenced to the NIST-3133 Hg standard (analyzed before and after each sample):

MIF is reported in Δ notation, which describes the difference between the measured δXXXHg and the theoretically predicted δXXXHg value, in units of ‰:

β is 0.2520 for 199Hg, 0.5024 for 200Hg, and 0.7520 for 201Hg61. Analytical uncertainty was estimated based on the replication of the NIST-3177 standard solution. The overall average and uncertainty of NIST-3177 (δ202Hg: −0.59 ± 0. 16‰; Δ199Hg: 0.01 ± 0.06‰; Δ200Hg: 0.00 ± 0.07‰; Δ201Hg: −0.03 ± 0.07‰, 2 SD, n = 11) and GSS-4 (δ202Hg: −1.57 ± 0.17‰; Δ199Hg: −0.44 ± 0.05‰; Δ200Hg: 0.01 ± 0.08‰; Δ201Hg: −0.43 ± 0.06‰, 2 SD, n = 6) (Supplementary Table 4) agrees well with previous studies9,37,61. The larger values of 2 SD for NIST-3177 and GSS-4 represent the analytical uncertainties of our samples.

Data availability

All data is available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Low Mid-Proterozoic atmospheric oxygen levels and the delayed rise of animals. Science 346, 635–638 (2014).

Zhang, S. et al. The mesoproterozoic oxygenation event. Sci. China Earth Sci. 64, 2043–2068 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Sufficient oxygen for animal respiration 1,400 million years ago. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1731–1736 (2016).

Hardisty, D. S. et al. Perspectives on Proterozoic surface ocean redox from iodine contents in ancient and recent carbonate. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 463, 159–170 (2017).

Shang, M. et al. A pulse of oxygen increase in the early Mesoproterozoic ocean at ca. 1.57–1.56 Ga. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 527, 115797 (2019).

Wei, W. et al. A transient swing to higher oxygen levels in the atmosphere and oceans at ~1.4 Ga. Precambr. Res. 354, 106058 (2021).

Xie, B. et al. Mesoproterozoic oxygenation event: From shallow marine to atmosphere. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135, 753–766 (2023).

Canfield, D. E. et al. Petrographic carbon in ancient sediments constrains Proterozoic Era atmospheric oxygen levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101544118 (2021).

Tang, D. et al. Enhanced weathering triggered the transient oxygenation event at ~1.57 Ga. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099018 (2022).

Zhu, S. et al. Decimetre-scale multicellular eukaryotes from the 1.56-billion-year-old Gaoyuzhuang Formation in North China. Nat. Communi. 7, 11500 (2016).

Berner, R. A. The long-term carbon cycle, fossil fuels and atmospheric composition. Nature 426, 323–326 (2003).

Wang, H. et al. Spatiotemporal redox heterogeneity and transient marine shelf oxygenation in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 270, 201–217 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. Dynamic redox and nutrient cycling response to climate forcing in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Nat. Commun. 14, 6640 (2023).

Ernst, R. E. & Youbi, N. How large igneous provinces affect global climate, sometimes cause mass extinctions, and represent natural markers in the geological record. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 478, 30–52 (2017).

Diamond, W. et al. Breaking the Boring Billion: a case for solid-Earth processes as drivers of system-scale environmental variability during the mid-Proterozoic in Large Igneous Provinces: A Driver of Global Environmental and Biotic Changes, R. Ernst, A. J. Dickson, A. Bekker, pp. 487–501, Eds. (Wiley, 2021).

Horton, F. Did phosphorus derived from the weathering of large igneous provinces fertilize the Neoproterozoic ocean? Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 1723–1738 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Subaerial volcanism broke mid-Proterozoic environmental stasis. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk5991 (2024).

Grasby, S. E., Them, T. R. I. I., Chen, Z., Yin, R. & Ardakani, O. H. Mercury as a proxy for volcanic emmisions in the geologic record. Earth-Sci. Rev. 196, 102880 (2019).

Wu, Y. W. et al. Highly fractionated Hg isotope evidence for dynamic euxinia in shallow waters of the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 616, 118211 (2023).

Blum, J. D., Sherman, L. S. & Johnson, M. W. Mercury isotopes in earth and environmental sciences. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 249–269 (2014).

Bergquist, B. A. & Blum, J. D. Mass-dependent and-independent fractionation of Hg isotopes by photoreduction in aquatic systems. Science 318, 417–420 (2007).

Štrok, M., Baya, P. A. & Hintelmann, H. The mercury isotope composition of Arctic coastal seawater. C. R. Geosci. 347, 368–376 (2015).

Demers, J. D., Blum, J. D. & Zak, D. R. Mercury isotopes in a forested ecosystem: implications for air‐surface exchange dynamics and the global mercury cycle. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 222–238 (2013).

Shen, J. et al. Intensified continental chemical weathering and carbon-cycle perturbations linked to volcanism during the Triassic–Jurassic transition. Nat. Commun. 13, 299 (2022).

Bayon, G., Bindeman, I. N., Trinquier, A., Retallack, G. J. & Bekker, A. Long-term evolution of terrestrial weathering and its link to Earth’s oxygenation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117490 (2022).

Zerkle, A. L. et al. Anomalous fractionation of mercury isotopes in the Late Archean atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 11, 1709 (2020).

Meixnerová, J. et al. Mercury abundance and isotopic composition indicate subaerial volcanism prior to the end–Archean “whiff” of oxygen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2107511118 (2021).

Zheng, W., Gilleaudeau, G. J., Kah, L. C. & Anbar, A. D. Mercury isotope signatures record photic zone euxinia in the Mesoproterozoic ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10594–10599 (2018).

Gilleaudeau, G. J. et al. Uranium isotope evidence for limited euxinia in mid-Proterozoic oceans. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 521, 150–157 (2019).

Tang, D. et al. Ferruginous seawater facilitates the transformation of glauconite to chamosite: an example from the Mesoproterozoic Xiamaling Formation of North China. Am. Mineral. 102, 2317–2332 (2017).

Meng et al. Stratigraphic and sedimentary records of the rift to drift evolution of the northern north china craton at the Paleo- to Mesoproterozoic transition. Gondwana Res 20, 205–218 (2011).

Lyu, D. et al. Using cyclostratigraphic evidence to define the unconformity caused by the Mesoproterozoic Qinyu Uplift in the North China Craton. J. Asian Earth Sci. 206, 104608 (2021).

Retallack, G. J. Precambrian life on land. The Palaeobotanist 63, 1–15 (2014).

Yuan, W. et al. Mercury isotopes show vascular plants had colonized land extensively by the early Silurian. Sci. Adv. 9, eade9510 (2023).

Sherman, L. S. et al. TAMass-independent fractionation of mercury isotopes in Arctic snow driven by sunlight. Nat. Geosci. 3, 173–177 (2010).

Auyang, D. et al. South-hemispheric marine aerosol Hg and S isotope compositions reveal different oxidation pathways. Natl Sci. Open 1, 47–64 (2022).

Sun, R. et al. Volcanism-triggered climatic control on Late Cretaceous oceans. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 23, e2021GC010292 (2022).

Shen, J. et al. Mercury in marine Ordovician/Silurian boundary sections of South China is sulfide hosted and non-volcanic in origin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 511, 130–140 (2019).

Kongchum, M., Hudnall, W. H. & Delaune, R. Relationship between sediment clay minerals and total mercury. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 46, 534–539 (2011).

Quémerais, B., Cossa, D., Rondeau, B., Pham, T. T. & Fortin, B. Mercury distribution in relation to iron and manganese in the waters of the St. Lawrence river. Sci. Total Environ. 213, 193–201 (1998).

Gehrke, G. E., Blum, J. D. & Meyers, P. A. The geochemical behavior and isotopic composition of Hg in a mid-Pleistocene western Mediterranean sapropel. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 1651–1665 (2009).

Percival, L. M. E. et al. Globally enhanced mercury deposition during the end-Pliensbachian extinction and Toarcian OAE: A link to the Karoo–Ferrar Large Igneous Province. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 428, 267–280 (2015).

Zhang, S. H. et al. Pre-Rodinia supercontinent Nuna shaping up: a global synthesis with new paleomagnetic results from North China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 353–354, 145–155 (2012).

Chen, J., Hintelmann, H., Feng, X. & Dimock, B. Unusual fractionation of both odd and even mercury isotopes in precipitation from Peterborough, ON, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 90, 33–46 (2012).

Tyrrell, T. The relative influences of nitrogen and phosphorus on oceanic primary production. Nature 400, 525–531 (1999).

Tribovillard, N. et al. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleoproductivity proxies: an update. Chem. Geol. 232, 12–32 (2006).

Grasby, S. E. et al. Marine snowstorm during the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Geology https://doi.org/10.1130/G51497.1 (2023).

Holland, H. D. Volcanic gases, black smokers, and the Great Oxidation Event. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 3811–3826 (2002).

Cox, G. M., Lyons, T. W., Mitchell, R. N., Hasterok, D. & Gard, M. Linking the rise of atmospheric oxygen to growth in the continental phosphorus inventory. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 489, 28–36 (2018).

Yin, R. et al. Anomalous mercury enrichment in Early Cambrian black shales of South China: mercury isotopes indicate a seawater source. Chem. Geol. 467, 159–167 (2017).

Li, Z. X. et al. Decoding Earth’s rhythms: modulation of supercontinent cycles by longer superocean episodes. Precambr. Res. 323, 1–5 (2019).

Tang, M., Chu, X., Hao, J. & Shen, B. Orogenic quiescence in Earth’s middle age. Science 371, 728–731 (2021).

Lenton, T. M. & Watson, A. J. Biotic enhancement of weathering, atmospheric oxygen and carbon dioxide in the Neoproterozoic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L05202 (2004).

Knauth, L. P. & Kennedy, M. J. The late Precambrian greening of the Earth. Nature 460, 728–732 (2009).

Evans, D. A. D. & Mitchell, R. N. Assembly and breakup of the core of Paleoproterozoic–Mesoproterozoic supercontinent Nuna. Geology 39, 443–446 (2011).

Bond, D. P. G. & Grasby, S. E. On the causes of mass extinctions. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 478, 3–29 (2017).

Zhao, G., Sun, M., Wilde, S. & Li, S. Assembly, accretion and breakup of the Paleo-Mesoproterozoic Columbia supercontinent: records in the North China Craton. Gondwana Res. 6, 417–434 (2003).

Taylor, S. R. & McLennan, S. M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution (Blackwell, 1985).

Sánchez, D. et al. Mercury and trace element fractionation in Almaden soils by application of different sequential extraction procedures. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 381, 1507–1513 (2005).

Yin, R. et al. Effects of mercury and thallium concentrations on high precision determination of mercury isotopic composition by Neptune Plus multiple collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 31, 2060–2068 (2016).

Blum, J. D. & Bergquist, B. A. Reporting of variations in the natural isotopic composition of mercury. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 388, 353–359 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences through the Hundred Talent Plan to R.Y. We thank Associate Editor Carolina Ortiz Guerrero for handling the manuscript. We appreciate Ross N. Mitchell and other anonymous reviewers for providing insightful comments on the manuscript. We declare no permissions were required for samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Y. designed research; A.L. and G.S. performed research; G.S. measured samples; A.L. and R.Y. interpreted the results; A.L. and R.Y. wrote the paper, with edits from S.E.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Ross Mitchell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, A., Sun, G., Grasby, S.E. et al. Large igneous provinces played a major role in oceanic oxygenation events during the mid-Proterozoic. Commun Earth Environ 5, 609 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01780-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01780-2

This article is cited by

-

An expansive global oxygenation of Earth’s surface environments 1.4 billion years ago

Nature Communications (2025)