Abstract

The most prominent abrupt climate event during the Holocene, the ‘8.2 ka event’, was characterized by severe cooling at high northern latitudes causing diverse hydroclimate shifts globally. A precise understanding of the hydroclimate response of the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool (IPWP) region to the 8.2 ka cooling, remains elusive. Here we present sub-centennial stable carbon isotope record on benthic foraminifera Asterorotalia pulchella and X-ray fluorescence elemental data of a marine sediment core from the Kallang River Basin, Singapore. We show that the rainfall in the western IPWP weakened for ~200 years at ~8.15 ± 0.03 ka BP, consistent with other regional and Southern Hemispheric records, however there is a lag of ~100 years from the North Atlantic cooling. A north-south signal propagation from the North Atlantic possibly via oceanic along with atmospheric routes operating on centennial scales led to southward location of Intertropical convergence zone causing droughts in Southeast Asia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abrupt short-term climate anomalies that punctuated the otherwise stable Holocene climate have drawn considerable attention from the paleoclimate community in the past few decades1,2,3. Abrupt climate events during the Holocene also had associated cultural impacts4,5,6,7,8 and are therefore crucial to examine as they may provide essential information about the climate system’s sensitivity to future perturbations9. The most prominent of the abrupt climate anomalies during the Holocene occurred around 8.2 calendar kiloyears before present (present is 1950; ka BP) from the perspective of Greenland temperature change1,10. Greenland temperature dropped by 3 °C and methane concentrations declined by 80 ppbv, suggesting a substantial change in the hydrologic cycle11. It is now widely accepted that the drainage of meltwater from the proglacial Laurentide lakes (lakes Agassiz and Ojibway) and icesheets around 8.5 ka BP into the Hudson Bay probably caused perturbations in the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation12,13 and slowed the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)14. Now several climate model experiments demonstrate the linkage between freshwater forcing and ensuing climate change globally15,16,17. The impacts of AMOC slowing was observed in the proxy records globally, for example, cave speleothems from Oman, Yemen, China and Brazil18,19; marine records from the Arabian Sea8,20; lake sequences from northwestern India21,22 and tropical Africa23(Gasse, 2000) and the Tibetan Plateau24; pollen records from the Mediterranean and east Asia25,26; ice cores from eastern Africa27. Owing to its widespread evidence28,29, it is suggested that for the Early–Middle Holocene Boundary, the ‘8.2 ka event’ constitutes a stratigraphic marker of near global significance, now formally known as the Northgrippian30.

The ‘8.2 ka event’ globally is well-documented by consistent evidence from multiple sites which are robust enough for the model simulations to reproduce them29. Although the ‘8.2 ka event’ involved smaller, shorter-lived, and less areally extensive climatic anomalies than those associated with older events such as the Younger Dryas cold interval or Heinrich stadials, nonetheless, this event punctuated early Holocene conditions that are inferred to be similar to or even warmer than today and therefore such events can serve as a useful benchmark to understand the processes involved by anthropogenic forcing in the future, and may provide useful estimates of limits on the magnitude of climate changes possible in the future29. However, there is a lot of ambiguity surrounding the occurrence and nature of 8.2 ka climate anomaly in the northern hemisphere tropics with some studies supporting drying in specific regions, some regions recording a double plunging structure19 of climate drying and others arguing that the duration of these anomalies were too long or started earlier than the North Atlantic cooling, to be attributed simply to the actual ‘8.2 ka event’29,31. In particular, the effect of 8.2 ka North Atlantic cooling on the hydroclimatic variability in the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool (IPWP) region remains ambiguous32.

The IPWP is known as the largest area of warm sea surface temperatures with the highest rainfall on Earth. It is also the largest source of atmospheric water vapor and latent heat and therefore drives the global atmospheric and hydrologic circulation33. The complex climatic system of the IPWP is controlled by large-scale phenomena such as the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) which causes the northwest and southeast monsoon circulation in the region as well as the tropical Pacific climate phenomena, the Indian Ocean Dipole in the west and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation operating to the east. In addition to interactions of these climate phenomena, their influence varies across the region due to island topography and ocean–atmosphere fluxes, which are mainly imposed by sea-surface temperature (SST) variability34. Because the IPWP lies at the intersection of such complex zonal and meridional hydrological processes, it is important to have a clearer understanding of how this region responded to abrupt climate changes such as the ‘8.2 ka event’ in the past.

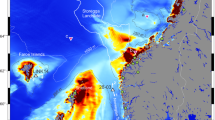

Here we present high-resolution (sub-centennial) stable carbon isotope record of carbonate shells of benthic foraminifer species Asterorotalia pulchella (Fig. S1) and sediment element analyses using X-ray fluorescence data from a shallow marine sediment core retrieved from Kallang River Basin, Singapore (Fig. 1; Fig. S2). We compare this data with a suite of regional records to examine the similarities/dissimilarities in the nature of hydroclimate variability documented in the IPWP region between 7.0 and 8.5 ka BP. We also analyze the timing of 8.2 ka-climate anomaly in the IPWP region in comparison with the evidence from the North Atlantic and the Asian- Indian monsoon regions. We compare the onset and termination of the 8.2 ka records in the northern and southern hemisphere with the aim to discuss the possible controls associated with the propagation of the ‘8.2 ka event’. Our results shed light on the possible causes to which the regional climate variability be attributed to and also the lead/lags observed in proxy records.

A Map of Singapore showing approximate extent of the Kallang River Basin (yellow shading); B Mean monthly precipitation (1981–2010) for Singapore from Changi climate station (1981–2010). Source: weather.gov.sg (accessed 10 October 2019); C Topographic map of the Maritime Continent with prominent published paleoclimate work used in this study marked. Red circle denotes location of the sediment core MSBH01B. Note that the current coastline is reclaimed and further seaward than during the early Holocene.

Kallang River Basin, Singapore

The Kallang River Basin (KRB) is located on the southern coast in Singapore (Fig. 1). This fluvio-deltaic system is predominantly made of late Quaternary sediments deposited during periods of relatively high sea levels during the present and last interglacials35. The coring site at Marina South, is reclaimed land that was previously a zone of shallow marine sedimentation. A continuous sediment core MS-BH01B (1.27266° N, 103.8653° E, ~38.5 m length) obtained through geotechnical rotary drilling and hydraulic piston coring, which allowed for >90% of sediment recovery35. The upper ~12 m was identified during wash-boring as modern fill material and discarded. The Holocene stratigraphy comprise early Holocene transgressive peats ( ~ 9.5 ka BP) which is succeeded by marine muds and eventually littoral/tidal silty sand deposited by ~7.2 ka BP. The period between 8.6 and 7.0 ka BP is well constrained by 9 AMS 14C ages measured on various wood and shell materials ranging from 7.19 ± 0.24 ka BP to 8.68 ± 0.57 ka BP36. Table S1 shows details of the AMS 14C dating of nine samples from core MSBH01B (Fig. S3). Recent sea-level reconstruction study indicate 8.4–7.6 ka BP as a period of fluvial influence at this marine site. The Kallang river basin during this period was characterised by fresh water conditions influenced by the river runoff providing a unique opportunity to explore the changes in runoff between 8.4 and 7.6 ka BP. Well-preserved benthic foraminifera shells appear following the deposition of transgressive peats at ~8.5 ka BP37. We focus on this Holocene unit from 8.6 to 7.0 ka BP to study the ‘8.2 ka event’ in the region.

Singapore experiences an equatorial type climate with rains throughout the year, with a relative minimum in June–July–August and maximum during the northern hemisphere winter from November- January with an average precipitation of ~250 mm (Fig. 1). Rainfall, temperature, and humidity are typically high year-round, and is shaped by alternating north-easterly winds (associated with circulation patterns of the austral summer monsoon from November to March), southeasterly trades (that form during the boreal summer southwest monsoon from June to September), and local convective systems.

Results

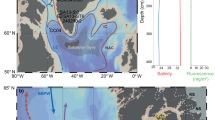

The KRB’s MSBH01B sediment core provides a high-resolution paleoclimate history from 8.5 to 7.0 ka BP. The resolution for 8.5 to 8.10 ka BP and from 7.96 to 7.50 ka BP is on average one δ13C measurement per 40 years and 33 years for the respective interval—this was undertaken to obtain a sub-centennial scale resolution of climate variability with replicate analysis where enough shells were extracted for isotopic measurements (Fig. S4; S5). For the interval between 8.15 ± 0.03 ka and 7.96 ka BP, foraminfera shell δ13C were analysed at approximately decadal scale resolution (Fig. 2). The δ13C values generally show a linear increasing trend across the entire period between 8.5 and 7.0 ka BP with an average of -2.63 ‰ between 8.5 and 8.1 ka BP and peak values of ~-1.77 ‰ between 8.2 ± 0.1 and 7.96 ka BP and ~1.5 ‰ between 7.96 and 7.0 ka BP. The K/Al ratios, measured at <50 years resolution (every 2 cm), have average values of 5.31 before and 3.16 after the δ13C minimum. The corresponding peak to the δ13C minimum has an average value of 11.5 value for K/Al between 8.1 and 7.96 ka BP.

a K/Al (blue) XRF elemental ratios on the sediment core; (b) stable carbon isotopes on benthic foraminifera A. pulchella (red). Also shown in. c is the BChron age model; Age vs depth in Mean Sea Level (MSL) and the radiocarbon dates in the 8.5-7.2 ka interval37.

Interpretation of proxy indicators

Salinity is a major governing factor on A. pulchella occurrence, with optimum salinity range from ~31 to 33 psu38. Rao et al. 39 reported high total abundances (live+fossil) of A. pulchella throughout the year, though the species was most abundant in January when the salinity was lowest (31–32 psu) and least abundant in April when the salinity was highest (34–35 psu). Stable isotopes of modern surface and subsurface samples of A. pulchella demonstrate that it can be used as a good candidate for paleoclimate reconstructions for the Indo–Pacific region38.

Assuming there is no temporal variability in the vital effect for A. pulchella living in the Kallang basin, the oxygen isotopes of foraminifer shells is controlled by the regional temperatures and the isotopic composition of the water in which the shell calcified. The isotopic composition of water in the case of marginal-marine/subtidal environments waters is influenced by the mixing of isotopically heavy marine water with isotopically light freshwater from regional precipitation and freshwater discharge. In addition to the freshwater and marine sources, the oxygen isotope signal is also influenced by high rates of evaporation in tropics, hence making the interpretation of oxygen isotopes of foraminifera carbonate as a precipitation proxy complex.

Unlike in deep-marine settings, in case of marginal-marine or sub-tidal estuarine settings, carbon isotope composition δ13C of benthic foraminifera as a proxy of paleoproductivity is suggested to be more reliable than oxygen isotopes for paleoclimatic inferences40. Mackensen and Schmeidl41 in a review on the application of stable carbon isotopes in paleoceanography demonstrated the use of carbon isotopes in determining the paleoproductivity and in turn changes in the freshwater flux at the study site in coastal regions. The carbon isotopes in marginal marine waters are influenced by the source of the organic carbon, which is influenced largely from the mixing of lighter (~ −26‰) terrestrially-derived organic matter and heavier ( ~ 20‰) marine organic matter42. These carbon sources influence the δ13C of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) which is taken up by foraminifera to form carbonate shells, such that the δ13C of shells reflect the carbon sources in the coastal region i.e. relative input from terrestrial (through precipitation/river runoff) and marine (primary productivity) derived carbon.

While the carbon derived from different types of terrestrial plants can also be a source of variability such that C3 plants (trees shrubs) preferentially incorporates 12C and C4 plants (agricultural plants and grasses) have heavier (more 13C incorporated) organic carbon isotopic values. Similarly, marsh plants and submerged aquatic grasses living along the margins of Kallang basin have relatively heavy carbon isotopic values. However, bulk sediment carbon isotopes from MSBH01B core for the period between 7.6 and 8 ka BP has more terrestrially derived carbon at the study site. This is the timing of Kallang delta formation with sustained high freshwater input at the study site, this is also the interval when the freshwater from Kallang river made the environment conducive for marginal marine foraminifera species to appear such as Elphidium sp., Ammonia sp., Asterotalia pulchella36. A. pulchella survives in relatively fresher water salinities of 31–33 psu38, therefore we interpret variation in foraminifera shell δ13C as the variation of terrestrial carbon brought that high (low) δ13C values in foraminifera shells indicate decreased (increased) input of terrestrially-derived carbon via Kallang river runoff at the study site.

Selection of weathering proxies for this study was based on the understanding of the palaeohydrology and source rock mineralogy of Singapore. A previous attempt at paleochannel mapping suggest several tributaries originating predominantly from the granitic exposures and hills in central Singapore35. Field observations reveal rapid weathering and decomposition of surficial granite forming a deep residual soil profile in the region43,44. The primary product of chemical weathering of granite in hot and humid tropical climates is kaolinite (Al2Si2O5(OH)4), a high-alumina clay which is readily remobilized45 and flushed into fluvial channels during periods of high rainfall.

Both potassium (K) and aluminium (Al) occur in the clay minerals as weathering products. Potassium occurs chiefly in illite while aluminium is abundant in all clay minerals46. Illite is generally a weathering product in temperate to arid climatic conditions that support strong physical weathering and weak chemical weathering and kaolinite is typically a product of chemical weathering in tropical, humid climates46,47. Therefore K/Al is a physical to chemical weathering proxy reflecting the abundance of illite relative to kaolinite respectively. Since the bulk sediment is primarily made of clay minerals, a decrease (increase) in K/Al of the bulk sediment would indicate a decrease (increase) in illite content and an increase (decrease) in kaolinite content which in turn indicates strengthened (weak) chemical weathering owing to high (low) rainfall. Therefore high K/Al indicate decreased chemical weathering and in turn drying.

Discussion

Hydroclimate changes in the western tropical warm pool

The general long term Kallang basin δ13C record follows the summer insolation at equator48 suggesting a relative decrease in productivity across 8.5–7.2 ka BP owing to the lower terrestrially-derived carbon brought by Kallang river runoff. This is consistent with the long term decreasing rainfall pattern in the region from the early Holocene (Fig. 3). For the interval under consideration in this study, the peak productivity suggesting higher rainfall occurs between 8.5 to ~8.2 ka BP (Fig. 2). This is in line with most tropical palaeo-precipitation records from north of the Equator that contain maxima in the range 10.0–8.0 ka BP49,50. In Southeast Asia, early Holocene was marked by submersion of large parts of the shallow landscapes in the Sunda Shelf and northern South China Sea51, as well as the incised channels on the continental shelves including those near Singapore. During the early Holocene, the Singapore Strait opened and ocean circulation patterns altered52,53. Flooding of the Sunda Shelf during the early Holocene also contributed to increasing the quantity and intensity of moisture transport from the oceans to continents54,55 strengtheining the hydrolocal cycle in southeast Asia56.

From top to bottom: speleothem δ18O from Klang Cave, Thailand58; δ13C of benthic foraminifera A. pulchella from MSBH01B core Singapore (this study); Speleothem δ18O from Tangga Cave, Sumatra32; δ18O of foraminifera G. ruber from marine sediment cores off northwestern Sumatra76, Liang Luar cave speleothem δ18O, Flores56. Map on top shows locations of respective proxy records.

An abrupt peak in δ13C of foraminifera beginning at ~8.15 ± 0.03 ka suggest decreased contribution of the terrestrial organic matter via the Kallang River runoff at the study site implying weakened convective activity in the region. This is followed closely by a period of diminished chemical weathering beginning at ~8.05 ka BP, inferred from high K/Al values suggesting weak chemical weathering and beginning of climate drying (less humid conditions) in the region. The century scale lag in timing of the productivity/ rainfall changes (inferred from δ13C) and the chemical weathering (inferred from K/Al) presumably stems from the time taken for the silicate rocks to weather into clays and the vegetation proxies are generally believed to have responded promptly to abrupt climate events26. Our δ13C and sediment proxy records suggest that an abrupt drying event began at ~8.2 ± 0.1 and ended at ~7.96 ka BP, lasting for about 180 years.

Regional evidence of the ‘8.2 ka event’

Owing to the high sedimentation rate ( ~ 4.4 mm/yr) in MSBH01B cores, it is possible to examine the timing and nature of the ‘8.2 ka event’ in detail in this region making this an invaluable and unique archive to study up to sub-centennial changes when sampled every centimeter. This is rare in marine sediment cores which are typically characterized by lower sedimentation rates, contributing to difficulties in collating results from other regional high-resolution archives (e.g. speleothems). In the IPWP region, the discordance between the type and resolution of marine and terrestrial (speleothem, corals and lacustrine) records is one of the several reasons that climate inferences are often contradictory32. The ‘8.2 ka event’ in the IPWP region is rather poorly documented and the differences in timing of drying between paleoclimate records in the IPWP region mainly stems from (1) different monsoon systems/ moisture sources affecting the region; (2) inadequate age control and differing sampling resolution; and (3) complex topography of the region. We discuss the prominent relatively high-resolution records from the IPWP region that have documented an 8.2 ka signal with respect to the KRB records in this section.

The timing of drying between 8.15 ± 0.03 ka and 7.96 ka BP recorded in the MSBH01B cores is coincident with the drying peak recorded in Gunung Buda cave in Borneo57. Both these records document changes in the local convective rainfall as compared to the variability in zonal and meridional processes such as the monsoon systems plying to the west (Indian monsoon), north (Asian monsoon), or south (Indonesian-Australian monsoon) of the region. Mohtadi et al., (2014) used surface-dwelling planktonic foraminifer Globigerinoides ruber δ18O to reconstruct variations in salinity from three marine sedimentary records off Sumatra spanning 45ka and identified ‘8.2 ka event’ along with past Heinrich events as dry periods in the northern Indian Ocean realm linked with the North Atlantic cold spells. A close inspection of these Sumatra marine records reveal a difference in timing of the 8.2 drying: 8.4-8.2 ka BP (in SO189-39KL), 8.3–8.1 ka (in SO189-144KL) and the northernmost core SO-189-119KL showing no drying at all across 8.5- 7.0 ka BP interval (Fig. 3). The inconsistency in the timing of drying between these three northern Sumatra cores can probably be attributed to the inadequate age control and sampling resolution for each of the cores (see Fig. 3). Another prominent study from the Sumatran island is from Tangga Cave speleothems which document a drying peak between 8.4 to 8.1 ka BP, centered at ~8.25 ka BP32. Both of the marine cores off Sumatra as well as the Tangga cave speleothems seem to have a fairly similar timing of drying centered at ~8.25 ka BP, which is also coincident with the drying in the Indian monsoon regions (Fig. 4d). Similarly, peak drying event in Klang Cave, Thailand is also reported to be centred at ~8.25 ka BP58. However, the timing of drying in the marine cores off Sumatra and Tannga Cave speleothems leads the drying in the Kallang core and Borneo speleothem records by about 100 years. Together, Sumatran marine and speleothem records portray a broad reduction in the hydrological activity around 8.25 ka BP in western Sumatra mostly influenced by the equatorial Indian Ocean dynamics, which also plays a crucial role in the Indian summer monsoon variability. On the other hand, Liang Luar cave speleothems from Flores, Indonesia which record the Australian-Indonesian monsoon variability, document no distinct drying around 8.2 ka BP and instead just follows the austral summer insolation with increasing rainfall from early to middle Holocene56.

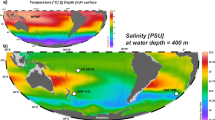

a Map showing various archives (Supplementary Table S2) documenting the 8.2 ka event; b Onset-termination bar (grey) graph of Northern and Southern hemispheric records with our record (MSBH01B*). Dry climatic conditions are represented in red, while wetter conditions are highlighted in blue. Site with no distinct hydroclimate change reported is marked in black.

Overall, the KRB proxy records provide an unequivocal evidence for weakening in the local convective rainfall in the western IPWP between 8.2 ± 0.1 and 7.96 ka BP which has been associated with the 8.2 ka cooling in the North Atlantic.

Comparison with 8.2 ka events recorded globally

It is clear that the 8.2 ka cold event in the North Atlantic was rapidly communicated through the ocean by an AMOC slowdown and through changes in atmospheric circulation that caused climate anomalies worldwide12,59. The exact timing of the early Holocene meltwater pulse has been dated to 8.47 ± 0.3 kyr BP (1σ)12, with the onset of the sharp cooling in the Greenland ice cores at ~8.25 ka BP (Fig. 4)60,61. The timing of cooling centered at ~8.2 ka BP in Greenland ice cores is synchronous to weakening of the Indian and Asian monsoon in well dated prominent speleothem records from Oman and China (Fig. 4). Oxygen isotopic evidence from paleolake Riwasa bulk sediments shows an abrupt drying that formed a hardground through dessication of the lake at ~8.2 ka BP62. Timing of drying is also coincident abrupt shifts in rainfall observed in Klang cave speleothems and Tangga Cave in the tropical Pacific56,58. In contrast, δ18O records from South America reveal a strong summer monsoon event ca. 8.2 ka BP documenting an anti-phased relationship19,63,64,65.

To evaluate the relationship between datasets recording 8.2 ka event from the northern and southern hemisphere Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out on selected datasets (Supplementary Table S3), antiphase relationship is clearly demonstrated in the PCA such that the PC1 score vs Age shows inverse trends (Fig. S6). Loading of individual records on the first principal componenets for each MC-PCA analysis with 1σ standard deviation error bar show that that NGRIP record lies in the same quadrant as our record suggesting similar behaviour (Fig. S6; S7). Another interesting observation in all the proxy records plotted meridonally from northern to southern hemisphere shows that the timing of onset of the 8.2 ka event in the southern hemisphere records lags the records in the northern hemisphere by about 100 years (Fig. 4). While this could be an attribute of the dating uncertainities in the records, a pattern of lag from northern to southern hemisphere is a domain that require further investigation (Fig. 4).

The Indian and Asian monsoon is antiphased with the South American summer monsoon for major events during the last glacial period, including the Younger Dryas, Dansgaard Oeschger and Heinrich events66,67,68. As compared to the Younger Drayas event, the 8.2 ka BP event was observed as half the amplitude in the Greenland ice core and monsoon records, documented as a double-plunging structure between ~8.2 and ~8.0 ka BP19. Isotopic records from the tropical pacific, lack a clear double-plunging structure in the 8.2 ka event, however this could be attributed to relatively fewer decadal-annual resolution records from the region. The timing of the onset of the ‘8.2 ka event’ in MSBH01B cores at ~8.15 ± 0.03 ka BP is synchronous with other regional tropical pacific records and other records from the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 4).

Teleconnection mechanism between North Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Warm Pool climate

The widely accepted mechanism for the coincident timing of the climate anomalies in the North Atlantic and the monsoon regions is the signal propagation both via ocean and atmospheric energy transport1,69. Decreased heat transport through oceans tend to shift the ITCZ southwards19. Model simulations demonstrate that the ocean meridional overturning circulation contributes significantly to the hemispheric asymmetry in tropical rainfall by transporting heat from the Southern to the Northern Hemisphere, and thereby positioning the ITCZ northward, regardless of whether continents are present or not70. Therefore a consequence of North Atlantic cooling related to the reduced strength of the meridional overturning circulation is more southwardly located ITCZ and a decline of monsoon rainfall70. The role of cross equatorial energy transport via atmosphere controlling the ITCZ position is also suggested such that the position of ITCZ tends to shift southward as the northward atmospheric energy transport across the equator strengthens in response to a northern high-latitude cooling71,72,73. Furthermore, the impact of change in Eurasian ice cover on the position of ITCZ is suggested via reinforcement of boreal cooling74. Thus a combination of atmospheric and oceanic processes linked to the North Atlantic cooling displaced the mean latitudinal position of the ITCZ to the south in phase with the Northern Hemisphere cooling. This north to south directionality, via the atmosphere and oceanic route, of signal propagation also corroborates with the hypothesis proposed for the Younger Dryas and older cold periods of the Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles67,75.

Within the uncertainty of 14C dated age model, the timing of the onset of drying at ~8.15 ± 0.03 ka BP observed in MSBH01B core, however, lags the timing of the onset of the North Atlantic cooling and monsoon weakening by ~100 years. The termination of the ‘8.2 ka event’ at ~7.96 ka BP in Kallang records, however is synchronous with the North Atlantic and the monsoon regions (Fig. 5).

Hydroclimate records from top to bottom of the panel are: Greenland NGRIP δ18O61; Kaite Cave, Paleolake Riwasa (NW India), Dongge Cave δ18O, China79; Qunf Cave speleothem δ18O18; %G. bulloides from Arabian Sea20; Klang Cave (Thailand), KRB core MSBH01B, Tangga Cave; Lapa Grande δ18O in South America; Botuvera cave δ18O. Grey bar denotes the extent of the 8.2 ka cooling event based on the Grrenland ice core δ18O record.

A variety of mechanisms have been proposed for such cold events, for the signal propagation from the North Atlantic to the tropical Indo-Pacific hydroclimates for past cold events primarily via oceanic route: (1) a weakening of the rainfall system in response to regional sea surface cooling; and (2) changes in the monsoon intensity associated with a southward shift in the mean or winter position of the ITCZ or in the position of oceanic fronts76. Owing to the location of Singapore in the western Indo-Pacific warm ocean region, its complex climatic system is controlled by the combined influence of ITCZ migration, IOD, ENSO, all of which are mainly imposed by SST variability34. We hypothesize that the northern high-latitude to low latitude directionality of cooling signal was possibly communicated to the tropical IPWP primarily through the oceanic route (on centennial scale), along with atmospheric processes, which could be responsible for about a century scale lag. The role of oceanic processes (mainly via changes in Southern Ocean temperature) in response to the abrupt change in the AMOC strength via the bipolar seesaw has previously been proposed77,78. This mechanism is consistent with the notion that convectional rainfall in the tropical warm pool region is fundamentally driven by oceanic dynamics and especially SST changes34. Proxy reconstructions from the southern hemisphere also demonstrate a century-long lag in the timing of onset of 8.2 ka event (Fig. 4). While a part of the lag in climate signal propsagation can be attributed to the difference in age models and dating uncertainities, consistent lag recorded in a number of absolute-dated speleothem records from the southern Hmeisphere warrants investigation from a mechanistic point of view.

A similar hypothesis has been proposed for the Younger Dryas period, although the magnitude of cooling was much higher when compared with the ‘8.2 ka event’67. Mohtadi et al.76 suggested that the response of tropical Indian ocean involved similar mechanisms for the Heinrich stadials, the Younger Dryas and the ‘8.2 ka event’, irrespective of glacial background climate states. Unlike the Younger Dryas termination which is believed to have initiated in the tropical Pacific region and propagated to high latitudes, suggesting a tropics to North Atlantic–Asian Monsoon-Westerlies directionality of climatic recovery67, the termination of the ‘8.2 ka event’ have a synchronous timing across the tropical Pacific- Indian/Asian monsoon—North Atlantic18,20,79. Modeling simulations provide a possible explanation for the centennial scale duration and synchronous termination of the ‘8.2 ka event’. The 8.2 ka event demonstrated the existence of an additional equilibrium climate state primarily controlled by the freshwater pulse causing reduced North Atlantic Deep Water formation, following which when the meltwater runoff eventually waned, the initial circulation pattern was rapidly restored near synchronously as the cold phase ended as seen in anomalies worldwide synchronously17,80.

Summary and conclusions

It is imperative to analyse the cold event such as the ‘8.2 ka event’ to understand the impacts of future freshening of the North Atlantic forced by anthropogenic global warming. Most 8.2 ka climate anomalies documented in the existing paleoclimate records in mid-low-latitude systems suggest the downstream impacts of a meltwater pulse into the North Atlantic and its associated sharp cooling event. Rohling et al.81 suggested that such a mechanism cannot be held responsible for the climate anomaly of longer duration and/or early onset of climate deterioration well before the North Atlantic cold event and careful consideration needs to be given while evaluating climate anomalies around ‘8.2 ka event’ and establishing their causal mechanism.

Our high resolution KRB record provides an unequivocal evidence of the 8.2 ka event in the tropical IPWP region and adds to a growing body of evidence of the response of regional hydroclimate changes globally to the North Atlantic forcing at 8.2 ka. Owing to the location of the sediment core, the KRB provide independent records of local convective rainfall of the western IPWP and a clear evidence of a drying event that lasted for about 200 years from ~8.15 ± 0.03 ka-7.96 ka BP. We suggest that this drying event was the tropical ocean response to the ‘8.2 ka cold event’ in the North Atlantic. The timing of the onset of drying in our record lags the North Atlantic cooling and concomitant drying in monsoon regions by about a century, this is in close correspondence with the proxy reconstructions from the southern hemisphere (Fig. 4). This lag in the impact of 8.2 ka cooling could be possibly due to the time taken for the redistribution of heat via atmospheric and oceanic processes.

The atmospheric-oceanic mechanism explaining the timing and mechanism of 8.2 ka signal propagation from the North Atlantic to the IPWP region in KRB proxy records is in line with previously published modeling and proxy studies. Nonetheless the causal sequence, mechanism causing lag in response between tropics and the North Atlantic still remains a challenging issue for modeling approaches and therefore more proxy records with precise chronology and spatial distribution spanning the entire complex IPWP are valuable for future model simulations.

Methods

Stable isotope ratios of Asterorotalia pulchella

We used benthic foraminifer species Asterorotalia pulchella for stable carbon and oxygen isotopic analysis. A. pulchella is a benthic epifaunal foraminifera found to be endemic in South Asia. Previous studies conducted along other inner shelves environment such as Moutama Bay, Muthupet Lagoon and Pahang River estuary show that it is a dominant species found in marginal marine environments82,83,84,85. This species is generally found in areas where water depth is low with fine-grained silty to muddy substrate. A. pulchella is also able to tolerate a wider range of salinity, from 34 to as low as 29 psu, making it more euryhaline than other marine species38,86. Its ability to tolerate a wider range of salinity makes it a suitable candidate to ensure that this species is present throughout the period of interest where freshwater influx is expected to vary. Previously, Panchang & Nigam (2012) also demonstrated that stable isotopes of A. pulchella carbonate shells can be used for paleoclimate reconstructions for the Indo-Pacific region where this species is found to be prevalent in marginal marine environments.

Approximately 5-15 individual tests were picked for each measurement and analysed using a Thermo Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled with GasBench housed at the Asian School of Environment, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The isotopic composition of the carbonate sample was measured on the CO2 gas evolved by treatment with phosphoric acid at a constant temperature of 75 °C. For all stable isotope measurements an internal working standard was used, which has been calibrated against VPDB (Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite) by using the NBS 18 and 19 standards. Consequently, all isotopic data given here are relative to the VPDB standard. Analytical standard deviation is about ± 0.06‰ for δ13C. Replicate analysis ( >2) were carried out on all the samples where >10 number foraminifera shells could be extracted (Fig. S4; S5).

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) scanning

We measured the relative elemental composition of the core segments using an Avaatech micro- X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Core Scanner II (AVAATECH Serial No. 2) housed at the Asian School of the Environment, Nanyang Technological University. Each core surface was carefully covered with 4 µm SPEXCerti Prep Ultralene® film to avoid sample contamination and carefully smoothed using sterile plastic scrappers. All core segments were scanned at 1 cm resolution with measurement slit size at 1 × 1 cm. Generator settings of 10 kV and 30 kV settings, coupled with exposure times of 15 s and 25 s respectively, were used to measure elemental abundance counts from Aluminium (Al) to Iron (Fe). All element counts were normalized to the total count numbers to correct for drift of the XRF Core Scanner.

Age model

The age model is based on 16 accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) 14C ages ranging from 9.5 to 7.2 ka BP37. AMS 14C dating was carried out at the Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory at GNS Science, New Zealand. Radiocarbon ages were converted to calibrated calendar years before present (ka BP) using the calibration software CALIB 8.2 (Stuiver, et al., 2020) and the IntCal20 and Marine20 calibration curves87. ΔR was calculated using the deltar application88 from a paired in situ bivalve-wood sample in core MSBH01B37.

The age-depth model was89 produced using BChron90, an open source R package utilising a Bayesian statistical approach, which provides uncertainties and increases robustness of the age model, for chronological reconstruction. Here, 1050 age-depth realizations were obtained to estimate the median age and 95% confidence intervals at 1 cm resolution.

Principal Component Analysis

The MC-PCA (Monte Carlo-Principal Component Analysis) technique was used to assess the coherency and patterns of the 8.2 ka anomaly in the records globally. We conducted analyses on 13 paleoclimate records from the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, selected based on data resolution and continuity between the interval from 8400 BP to 7800 BP. The isotopic records were non-uniformly spaced in time. Following Deininger et al.91, a linearly spaced age range was created for consistent temporal resolution, and 2000 age models were generated with Gaussian-distributed variations within one standard deviation. Linear interpolation was applied to δ18O values, yielding age models with varying temporal resolutions. Upscaling the age models to 12-year-long bins using a Gaussian kernel ensured consistent PCA across various locations. Climate records were normalized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. To enhance robustness, 1000 MC-PCA were performed. Each simulation randomly selected 10 age models from a pool of 2000, allowing for comprehensive exploration and reliable results. A flipping procedure corrected any flipped Principal Components (PCs) caused by age uncertainties. The final PCA time series was calculated by determining the mean and standard deviation for each bin. Significantly meaningful principal components were selected using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test at a 95% confidence level.

Data availability

The dataset of air temperature used in this study is available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27126270.

References

Alley, R. B. & Ágústsdóttir, A. M. The 8k event: cause and consequences of a major Holocene abrupt climate change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1123–1149 (2005).

Wanner, H., Solomina, O., Grosjean, M., Ritz, S. P. & Jetel, M. Structure and origin of Holocene cold events. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 3109–3123 (2011).

Mayewski, P. A. et al. Holocene climate variability. Quat. Res. 62, 243–255 (2004).

Dixit, Y., Hodell, D. A. & Petrie, C. A. Abrupt weakening of the summer monsoon in northwest India ~4100 yr ago. Geology 42, 339–342 (2014).

Dixit, Y. et al. Intensified summer monsoon and the urbanization of Indus Civilization in northwest India. Sci. Rep. 8, (2018).

Petrie, C. A. et al. Adaptation to Variable Environments, Resilience to Climate Change: Investigating Land, Water and Settlement in Indus Northwest India. Curr. Anthropol. 58, 0 (2017).

Roffet-Salque, M. et al. Evidence for the impact of the 8.2-kyBP climate event on Near Eastern early farmers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8705 LP–8708709 (2018).

Staubwasser, M. & Weiss, H. Holocene Climate and Cultural Evolution in Late Prehistoric–Early Historic West Asia. Quat. Res. 66, 372–387 (2006).

Curry, R., Dickson, B. & Yashayaev, I. A change in the freshwater balance of the Atlantic Ocean over the past four decades. Nature 426, 826–829 (2003).

Thomas, E. R. et al. The 8.2 ka event from Greenland ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 70–81 (2007).

Kobashi, T., Severinghaus, J. P., Brook, E. J., Barnola, J.-M. & Grachev, A. M. Precise timing and characterization of abrupt climate change 8200 years ago from air trapped in polar ice. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 1212–1222 (2007).

Barber, D. C. et al. Forcing of the cold event of 8,200 years ago by catastrophic drainage of Laurentide lakes. Nature 400, 344–348 (1999).

Wagner, A. J., Morrill, C., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Rosenbloom, N. & Watkins, K. R. Model support for forcing of the 8.2 ka event by meltwater from the Hudson Bay ice dome. Clim. Dyn. 41, 2855–2873 (2013).

Kleiven, H. K. F. et al. Reduced North Atlantic deep water coeval with the glacial Lake Agassiz freshwater outburst. Science (1979) 319, 60–64 (2008).

LeGrande, A. N. et al. Consistent simulations of multiple proxy responses to an abrupt climate change event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 103, 837–842 (2006).

Wiersma, A. P. & Renssen, H. Model–data comparison for the 8.2 ka BP event: confirmation of a forcing mechanism by catastrophic drainage of Laurentide Lakes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 63–88 (2006).

Matero, I. S. O., Gregoire, L. J., Ivanovic, R. F., Tindall, J. C. & Haywood, A. M. The 8.2 ka cooling event caused by Laurentide ice saddle collapse. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 473, 205–214 (2017).

Fleitmann, D. et al. Holocene Forcing of the Indian Monsoon Recorded in a Stalagmite from Southern Oman. Science (1979) 300, 1737 (2003).

Cheng, H. et al. Timing and structure of the 8.2 kyr BP event inferred from δ18O records of stalagmites from China, Oman, and Brazil. Geology 37, 1007–1010 (2009).

Gupta, A. K., Anderson, D. M. & Overpeck, J. T. Abrupt changes in the Asian southwest monsoon during the Holocene and their links to the North Atlantic Ocean. Nature 421, 354–357 (2003).

Dixit, Y. Regional character of the “global monsoon”:Paleoclimate insights from Northwest Indian lacustrine sediments. Oceanography 33, (2020).

Dixit, Y., Hodell, D. A., Sinha, R. & Petrie, C. A. Abrupt weakening of the Indian summer monsoon at 8.2 kyr B.P. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 391, 16–23 (2014).

Gasse, F. Hydrological changes in the African tropics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 189–211 (2000).

Mischke, S. & Zhang, C. Holocene cold events on the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Planet Change 72, 155–163 (2010).

Peyron, O. et al. Precipitation changes in the Mediterranean basin during the Holocene from terrestrial and marine pollen records: a model–data comparison. Climate 13, 249–265 (2017).

Park, J. et al. The 8.2 ka cooling event in coastal East Asia: High-resolution pollen evidence from southwestern Korea. Sci. Rep. 8, 12423 (2018).

Thompson, L. G. et al. Kilimanjaro ice core records: evidence of Holocene climate change in tropical Africa. Science (1979) 298, 589–593 (2002).

Morrill, C. & Jacobsen, R. How widespread were climate anomalies 8200 years ago? Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, (2005).

Morrill, C. et al. Proxy benchmarks for intercomparison of 8.2 ka simulations. Clim. Past 9, (2013).

Walker, M. et al. Subdividing the Holocene Series/Epoch: formalization of stages/ages and subseries/subepochs, and designation of GSSPs and auxiliary stratotypes. J. Quat. Sci. 34, 173–186 (2019).

Voarintsoa, N. R. G. et al. Investigating the 8.2 ka event in northwestern Madagascar: Insight from data–model comparisons. Quat. Sci. Rev. 204, 172–186 (2019).

Wurtzel, J. B. et al. Tropical Indo-Pacific hydroclimate response to North Atlantic forcing during the last deglaciation as recorded by a speleothem from Sumatra, Indonesia. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 492, 264–278 (2018).

De Deckker, P. The Indo-Pacific Warm Pool: critical to world oceanography and world climate. Geosci. Lett. 3, 20 (2016).

Aldrian, E. & Dwi Susanto, R. Identification of three dominant rainfall regions within Indonesia and their relationship to sea surface temperature. Int J. Climatol. 23, 1435–1452 (2003).

Chua, S. et al. A new Quaternary Stratigraphy of the Kallang River Basin, Singapore: Implications for Urban Development and Geotechnical Engineering in Singapore. J Asian Earth Sci 104430 (2020).

Chua, S. et al. A new Holocene sea-level record for Singapore. Holocene 31, 1376–1390 (2021).

Chua, S. et al. Coastal response to Holocene Sea-level change: A case study from Singapore. Mar. Geol. 465, 107146 (2023).

Panchang, R. & Nigam, R. High resolution climatic records of the past~ 489 years from Central Asia as derived from benthic foraminiferal species, Asterorotalia trispinosa. Mar. Geol. 307, 88–104 (2012).

Rao, P. S., Ramaswamy, V. & Thwin, S. Sediment texture, distribution and transport on the Ayeyarwady continental shelf, Andaman Sea. Mar. Geol. 216, 239–247 (2005).

Saltzman, M. R., Thomas, E. & Gradstein, F. M. Carbon isotope stratigraphy. geologic time scale 1, 207–232 (2012).

Mackensen, A. & Schmiedl, G. Stable carbon isotopes in paleoceanography: atmosphere, oceans, and sediments. Earth Sci. Rev. 197, 102893 (2019).

Bouillon, S., Connolly, R. M. & Lee, S. Y. Organic matter exchange and cycling in mangrove ecosystems: recent insights from stable isotope studies. J. Sea Res. 59, 44–58 (2008).

Zhao, J., Broms, B. B., Zhou, Y. & Choa, V. A study of the weathering of the Bukit Timah granite Part B: field and laboratory investigations. Bull. Int. Assoc. Eng. Geol.-Bull. de. l’Assoc. Int. de. Géologie de. l’Ing.énieur 50, 105–111 (1994).

Rahardjo, H., Aung, K. K., Leong, E. C. & Rezaur, R. B. Characteristics of residual soils in Singapore as formed by weathering. Eng. Geol. 73, 157–169 (2004).

Rothwell, R. G. Twenty years of XRF core scanning marine sediments: what do geochemical proxies tell us? in Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores 25–102 (Springer, 2015).

Boyle, E. A. Chemical accumulation variations under the Peru Current during the past 130,000 years. J. Geophys Res. Oceans 88, 7667–7680 (1983).

Yarincik, K. M., Murray, R. W. & Peterson, L. C. Climatically sensitive eolian and hemipelagic deposition in the Cariaco Basin, Venezuela, over the past 578,000 years: Results from Al/Ti and K/Al. Paleoceanography 15, 210–228 (2000).

Berger AndréL. Long-Term Variations of Daily Insolation and Quaternary Climatic Changes. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 2362–2367 (1978).

Stott, L. et al. Decline of surface temperature and salinity in the western tropical Pacific Ocean in the Holocene epoch. Nature 431, 56–59 (2004).

Haug, G. H., Hughen, K. A., Sigman, D. M., Peterson, L. C. & Röhl, U. Southward Migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone Through the Holocene. Science 293, 1304 LP–1301308 (2001).

Hanebuth, T., Stattegger, K. & Grootes, P. M. Rapid flooding of the Sunda Shelf: a late-glacial sea-level record. Science 288, 1033–1035 (2000).

Smith, D. E., Harrison, S., Firth, C. R. & Jordan, J. T. The early Holocene sea level rise. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 1846–1860 (2011).

Bird, M. I., Pang, W. C. & Lambeck, K. The age and origin of the Straits of Singapore. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 241, 531–538 (2006).

Cook, C. G. & Jones, R. T. Palaeoclimate dynamics in continental Southeast Asia over the last ~30,000Calyrs BP. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 339–341, 1–11 (2012).

Liew, P.-M., Huang, S.-Y. & Kuo, C.-M. Pollen stratigraphy, vegetation and environment of the last glacial and Holocene—A record from Toushe Basin, central Taiwan. Quat. Int. 147, 16–33 (2006).

Griffiths, M. L. et al. Increasing Australian–Indonesian monsoon rainfall linked to early Holocene sea-level rise. Nat. Geosci. 2, 636–639 (2009).

Partin, J. W., Cobb, K. M., Adkins, J. F., Clark, B. & Fernandez, D. P. Millennial-scale trends in west Pacific warm pool hydrology since the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature 449, 452–455 (2007).

Chawchai, S. et al. Hydroclimate variability of central Indo-Pacific region during the Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 253, 106779 (2021).

Alley, R. B. et al. Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago. Geology 25, 483–486 (1997).

Svensson, A. et al. A 60 000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Climate 4, 47–57 (2008).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A new Greenland ice core chronology for the last glacial termination. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosp. 111, (2006).

Dixit, Y., Hodell, D. A., Sinha, R. & Petrie, C. A. Abrupt weakening of the Indian summer monsoon at 8.2 kyr BP. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 391, 16–23 (2014).

Stríkis, N. M. et al. Abrupt variations in South American monsoon rainfall during the Holocene based on a speleothem record from central-eastern Brazil. Geology 39, 1075–1078 (2011).

Parker, S. E. & Harrison, S. P. The timing, duration and magnitude of the 8.2 ka event in global speleothem records. Sci. Rep. 12, 10542 (2022).

Bernal, J. P. et al. A speleothem record of Holocene climate variability from southwestern Mexico. Quat. Res. 75, 104–113 (2011).

Cruz, F. W. Jr et al. A stalagmite record of changes in atmospheric circulation and soil processes in the Brazilian subtropics during the Late Pleistocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 2749–2761 (2006).

Cheng, H. et al. Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 23408–23417 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Meltwater pulse1A triggered an extreme cooling event: evidence from Southern China. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 37, e2022PA004426 (2022).

Cheng, H., Sinha, A., Wang, X., Cruz, F. W. & Edwards, R. L. The Global Paleomonsoon as seen through speleothem records from Asia and the Americas. Clim. Dyn. 39, 1045–1062 (2012).

Frierson, D. M. W. et al. Contribution of ocean overturning circulation to tropical rainfall peak in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Geosci. 6, 940–944 (2013).

Bischoff, T. & Schneider, T. The equatorial energy balance, ITCZ position, and double-ITCZ bifurcations. J. Clim. 29, 2997–3013 (2016).

Kang, S. M., Frierson, D. M. W. & Held, I. M. The tropical response to extratropical thermal forcing in an idealized GCM: The importance of radiative feedbacks and convective parameterization. J. Atmos. Sci. 66, 2812–2827 (2009).

Donohoe, A., Marshall, J., Ferreira, D., Armour, K. & McGee, D. The interannual variability of tropical precipitation and interhemispheric energy transport. J. Clim. 27, 3377–3392 (2014).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. Links between the East Asian monsoon and North Atlantic climate during the 8,200 year event. Nat. Geosci. 6, 117–120 (2013).

Markle, B. R. et al. Global atmospheric teleconnections during Dansgaard–Oeschger events. Nat. Geosci. 10, 36–40 (2017).

Mohtadi, M. et al. North Atlantic forcing of tropical Indian Ocean climate. Nature 509, 76–80 (2014).

Broecker, W. S. Paleocean circulation during the last deglaciation: a bipolar seesaw? Paleoceanography 13, 119–121 (1998).

Shakun, J. D. & Carlson, A. E. A global perspective on Last Glacial Maximum to Holocene climate change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1801–1816 (2010).

Wang, Y. et al. The Holocene Asian monsoon: links to solar changes and North Atlantic climate. Science (1979) 308, 854–857 (2005).

Bauer, E., Ganopolski, A. & Montoya, M. Simulation of the cold climate event 8200 years ago by meltwater outburst from Lake Agassiz. Paleoceanography 19, (2004).

Rohling, E. Centennial-scale climate cooling with a sudden cold event around 8,200 years ago. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 172–186 (2005).

Ramlan, O. & Noraswana, N. F. Distribution of benthic Foraminifera in Pahang River estuary, Malaysia. Malays. Appl. Biol. 44, 1–5 (2015).

Saidova, K. M. Benthic foraminifera communities of the Andaman Sea (Indian Ocean). Oceanol. (Wash. D. C.) 48, 517–523 (2008).

Anbuselvan, N. Benthic foraminiferal distribution and biofacies in the shelf part of Bay of Bengal, east coast of India. Mar. Biodivers. 49, 691–706 (2019).

Szarek, R., Kuhnt, W., Kawamura, H. & Kitazato, H. Distribution of recent benthic foraminifera on the Sunda Shelf (South China Sea). Mar. Micropaleontol. 61, 171–195 (2006).

Solai, A., Gandhi, M. S. & Rao, N. R. Recent benthic foraminifera and their distribution between Tuticorin and Tiruchendur, Gulf of Mannar, south-east coast of India. Arab. J. Geosci. 6, 2409–2417 (2013).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20—the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Reimer, R. W. & Reimer, P. J. An online application for […] R calculation. Radiocarbon 59, 1623 (2017).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Haslett, J. & Parnell, A. C. A simple monotone process with application to radiocarbon‐dated depth chronologies. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 57, 399–418 (2008).

Deininger, M. et al. Coherency of late Holocene European speleothem δ18O records linked to North Atlantic Ocean circulation. Clim. Dyn. 49, 595–618 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its MOE Academic Research Fund Tier 3, Award MOE-MOET32022-0006 and the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) grants M4430132.B50-2014 (Singapore Quaternary Geology), M4430139.B50-2015 (Singapore Holocene Sea Level), M4430188.B50-2016 (Singapore Drilling Project), M4430245.B50-2017 and M4430245.B50-2018 (Kallang Basin Project) and 04MNS001985A620OOE01 (Maritime Continent Project). This research was supported by the EOS via its funding from the National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Education under the Research Centres of Excellence initiative. This work comprises EOS contribution number 340. We thank the Director of the Earth Observatory of Singapore, Prof. Ben Horton for his support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. conceived the ideas, designed the work, did isotopic measurements, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. S.C. did the field investigation, did XRF analysis and helped analyze the results. Y.T. contributed to replicate stable isotope analysis and figure visualization. A.K. did the Principal Component Analysis and contributed to figure visualisation. A.S. was involved in funding acquisition, field investigation conceived the ideas and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Yama Dixit and Adam Switzer are Editorial Board Members for Communications Earth & Environment, but were not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Kelly Gibson and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dixit, Y., Chua, S., Yan, Y.T. et al. Hydroclimatic impacts of the abrupt cooling event 8200 years ago in the western Indo-Pacific Warm Pool. Commun Earth Environ 5, 690 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01825-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01825-6