Abstract

Multi-millennial records of great megathrust earthquakes have highlighted differences in periodicity and recurrence behavior. Understanding tectonic processes responsible for these differences is relevant for fault mechanics and hazard models. Here, we present a paleoseismic record inferred from raised beach ridges in the 2010 Maule earthquake (Mw 8.8) segment in south-central Chile that includes 24 interseismic intervals over 4.5 kyr suggesting a weakly-periodic recurrence behavior. In turn, great earthquakes in the adjacent 1960 Valdivia earthquake (Mw 9.5) segment occurred with periodic recurrence over the same time span. Both segments have similar trench sediments thicknesses as well as rheological and geometrical boundary conditions, but Maule has a wider frontal accretionary wedge and several splay faults rooted in the seismogenic zone whereas Valdivia lacks splay faults and trench sediments are mostly subducted and underplated. These differences may have an impact on upper-plate compliance and megathrust friction, affecting earthquake size and recurrence periodicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The unexpected 2004 Sumatra-Andaman (Mw 9.2) and 2011 Tohoku-oki (Mw 9.2) giant earthquakes demonstrate the need to include paleoseismic archives for quantifying recurrence behavior and improving forecast accuracy1,2. Paleoseismic records of great megathrust earthquakes, including at least ten events, show variable recurrence behaviors, adding a degree of complexity to the assessment of future earthquake probabilities3,4,5. It has been proposed that several tectonic processes may influence the recurrence behavior of great megathrust earthquakes, such as changes in megathrust geometry6; thickness and nature of incoming trench sediments7; fault-zone permeability and fluid pressure8; variations in upper-plate geologic structure9; and lithospheric rheology10,11. The few megathrust segments that have generated the largest measured (Mw >8.5) earthquakes are characterized by a time-dependent, periodic recurrence behavior5, whereas most other segments by a weakly periodic pattern that include temporal clusters of variable-size earthquakes separated by less active intervals in long-term clusters, i.e. “supercycles”2,12,13. The tectonic processes that control these differences have not been fully understood and are important to gain insight into fault mechanics and its implications on seismic-cycle models with emphasis on hazard forecasts.

The earthquake recurrence behavior of geologic faults may be expressed in terms of the coefficient of variation (CoV), burstiness (B), and memory coefficient (M) of recurrence intervals14,15. A perfectly periodic sequence has CoV = 0 and B = −1, while aperiodic behavior has CoV = 1 and B = 0. In subduction zones, CoV ranges between 0.3 and 1 and B < 0, i.e., between quasi-periodic and weakly periodic supercycle behavior5,15. The M coefficient ranges between −1 and 1, positive if short (or long) periods tend to follow short (or long) periods, and negative if short (or long) periods tend to follow long (or short) periods. Long records (>10 megathrust events) reveal features not evident in shorter records, such as clusters of large earthquakes separated by long interseismic periods in Cascadia12 and Sumatra13,16, and frequent smaller earthquakes within the rupture area of occasional giant events in Tohoku17. Such variability challenges the application of simple, time-independent earthquake recurrence models for hazard assessment. Although the factors responsible for these differences are not fully understood, it has been suggested that recurrence behavior is controlled by seismogenic zone width18 and superimposed cycles between adjacent megathrust asperities19,20. Here, we present a 4.5-kyr-long record including 24 paleoseismic and recurrence intervals of great megathrust earthquakes from the Maule segment in south-central Chile. We integrate our data with a paleoseismic record of great earthquakes from the adjacent Valdivia segment21 and discuss the role of tectonic boundary conditions on earthquake recurrence behavior.

Seismotectonic setting of the south-central Chile margin

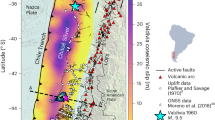

South-central Chile includes the Valdivia and Maule seismotectonic segments, which last ruptured during the 1960 (Mw 9.5) and 2010 (Mw 8.8) megathrust earthquakes (Fig. 1a), respectively22,23. Both segments are separated by a persistent barrier, as suggested by historical and paleoseismic data19,24,25, as well as numerical modeling experiments26. Long paleoseismic records (~5 kyr) from the Valdivia segment suggest giant Mw >8.6 megathrust earthquakes have occurred on average every 292 ± 93 yrs, while great Mw >7.7 earthquakes every 139 ± 69 yrs; both follow a quasi-periodic recurrence behavior with a CoV of 0.32 and 0.5 respectively21,27. In the Maule segment, great historical megathrust earthquakes occurred in 1570, 1657, 1751, 1835, and 201028, with recurrence intervals consistent with a geologic record of coseismic coastal land-level changes and tsunami inundation every 84–175 yr over the past 6 centuries25. Deformation in the Maule and Valdivia segments has the following differences: the former includes several active splay faults along the offshore forearc29,30 and bivergent thrust systems bounding the Main Cordillera, whereas the latter lacks major active forearc splay faults and the Main Cordillera is dominated by strike-slip deformation along its axis31 (Fig. 1a). The Chile trench along the Valdivia and Maule segments contains similar amounts of sediments32; however, these sediments are mostly underplated within a thick subduction channel and accreted beneath the continental shelf along the Valdivia segment33, while at Maule are mostly incorporated to the frontal accretionary wedge. These differences in accretion mode have led to variations in taper angles, interpreted to reflect higher basal friction along the interplate megathrust at Valdivia34,35.

a Location of the south-central Chile margin. Red and yellow contours denote coseismic slip during the 2010 Maule and 1960 Valdivia earthquakes, respectively22,23. Nazca (NA)–South America (SAM) margin, WATF Western Andean Trust Front, LOFS Liquiñe-Ofqui Fault System, PIF Pichilemu Fault30,60. b Map of Santa María Fault System (SMFS) around Isla Santa María (ISM)50,53. RF reverse fault and AN anticline. c Deformation at ISM during the 2010 earthquake from unwrapped advanced land observing satellite interferogram50. d ISM coastal plain topography with mapped ridges and absolute age (yrs BP ± 1σ) determinations of beach ridges model used in Fig. 3. Maps: Bathymetry and topography from GEBCO202271 and GMTED201072 data, d topography data authors’ own.

Isla Santa María (ISM, Fig. 1) is located 75 km from the trench and associated with the Santa Maria splay-fault system, which is rooted in the plate boundary at ~15 km36. During the 2010 earthquake, ISM was uplifted between 1.6 and 2.2 m, tilted parallel to the margin (Fig. 1c), and secondary faults broke the surface, suggesting a slip on the megathrust as well as along the splay fault37. The 1835 earthquake (Mw >8.5), the immediate predecessor of the 2010 event, uplifted the island by 2.4 to 3 m38. Between the 1835 and 2010 earthquakes, ISM subsided by about 1.6 m at a rate of 11.3 ± 4 mm/yr39. This centennial rate is similar to the interseismic rate measured by GPS between 2004 and 2010, and about half the average 2010-2023 postseismic subsidence rate of 25 mm/yr40. These observations suggest that the seismic cycle at ISM includes metric-scale coseismic uplifts followed by rapid post and interseismic subsidence. A recurrence interval of 180 ± 65 yrs for great earthquakes at ISM was estimated from a sequence of parallel ridges in a coastal plain interpreted as fossil beach berms abandoned as a result of coseismic uplift41. However, a survey of coastal evolution between 1941 and 2021, including the great 2010 earthquake, revealed that ridge formation rather occurred throughout post and interseismic periods, and thus that each ridge represents the time between earthquakes40. Here, we build upon observations of the 2010 cycle as a modern analog to construct a long-term paleoseismic record of megathrust earthquake cycles from the ISM coastal plain.

Results

Coastal plain geomorphology and stratigraphy

The ISM coastal plain consists of a series of parallel pairs of raised beach ridges and swales forming a geomorphic barcode (Fig. 1c, d). Using topographic curvature calculated from a 0.15-m DEM (methods), we mapped 24 ridge-swale pairs (Fig. 2 and Figs. S1, S2) oriented at an average strike of 134° and reaching 6.5 ± 0.2 m elevation (all elevations reported with respect to mean sea level). The ridges and swales are tilted along strike to the NW at an average of 0.025 ± 0.023° and 0.021 ± 0.016°, respectively (Figs. S3–S5). Along the modern coast, the beach berm and runnel (active swale) are basically flat (Fig. S6) and located at 2.2 ± 0.1 m and 1.3 ± 0.08 m, respectively. We use these elevations as the indicative meaning42 of the ridges and swales reference water level. Using the 24 ridge crest elevations, we fitted a plane oriented at the average strike of the ridges obtaining a NW tilt of 0.0344 ± 0.0006° (Fig. 2a, residuals in Fig. S7). During the 2010 earthquake, the coastal plain was tilted 0.0015 ± 0.0001° (Fig. 2b), and if we assume this tilt as characteristic of great earthquakes, 23 ± 2 similar events would be required to equal the coastal plain tilt (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the number of events predicted by this simple relation is equal within uncertainty to the number of ridges mapped in the coastal plain. This equality suggests a causal relation and that the coseismic component expressed as along-strike plain tilt is preserved over many cycles as permanent deformation; in turn, the vertical component of coseismic deformation is partly recovered by post- and interseismic subsidence39.

a Map of fitted plane to ridge crest points (topography data authors’ own). Note dip toward the northwest. Boxes indicate surveyed areas used for the composite topographic profile shown in (d). The inset shows a histogram of plane-fit residuals with a normal distribution curve. b Tilt during the 2010 earthquake and along the coastal plain. c Number of 2010-like tilt events required to achieve the plain tilt. Note the similarity with a number of beach ridges. d Composite topographic profile across the coastal plain indicating ridge numbers and width measurements (with 1 SD uncertainties).

We constructed a 2.2 km long composite topographic profile across the coastal plain for geomorphic analysis (see Methods, Fig. 2d and Fig. S8). The profile shows the sequence of 24 ridge-swale pairs with crests ranging in elevation from 2.6 ± 0.1 to 6.5 ± 0.2 m. The average ridge width is 66.4 ± 28.3 m, with marked changes throughout the sequence (Fig. 2d). Cross-sections of individual ridges show a mean relief of 0.92 ± 0.41 m and average seaward skewness of −0.45 ± 0.27 (Fig. S9). The seaward and landward slopes of the ridges are within the same order, with 0.031 ± 0.017° and 0.037 ± 0.025°, respectively (Fig. S9). These results show some variability within a relatively homogeneous beach ridge sequence.

Sub-surface imaging using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) profiles across the entire coastal plain shows a relatively homogeneous sequence of seaward-dipping reflectors, which we relate to beach faces formed by progressive coastal aggradation (Fig. S10). Beach-face reflectors, as well as along-strike ridge topography, are more discontinuous towards the youngest part of the sequence (300–800 m in Fig. 2d). We associate these changes with increased sedimentary activity by long-shore drift as the coast migrated seawards, reaching beyond the SW wind-shadow effect of the back cliff. Excavations revealed that the multiple 1 to 4 m long seaward-dipping high-amplitude reflectors observed in GPR images throughout the sequence consist of 1 to 5 cm thick layers of fine-grained black sand including heavy minerals (magnetite and titanite) (Figs. S11–S14) likely deposited during winter storms. The continuous occurrence of heavy-mineral layers throughout the sequence interbedded in the 4 to 8° dipping reflectors supports the notion of continuous beach progradation forming the coastal plain. Periods of protracted erosion may be discarded as no signs of truncations are observed in GPR or topographic profiles.

We excavated 29 pits to survey stratigraphy and collect samples for age determinations. The stratigraphy is monotonous across the plain and consists of an upper loamy soil horizon with signs of oxidation superposed to clean gray fine to medium volcanic sand (Figs. S12–S15). Layers of dark brown sand and heavy minerals were found in six pits (Figs. S13–S15). Transitions between these layers are usually gradual, except at heavy minerals layers, where contacts are sharp (Fig. S15). The similarity in sediment composition of these pits highlights the uniformity of sedimentary processes across the coastal plain.

Beach-ridge chronology

We collected 14 IRSL and three radiocarbon ages across the coastal plain (Fig. 1d) and tested the IRSL accuracy to date beach ridge abandonment by verifying that four ages collected from the front, crest, and back of ridge number 11 overlap within analytical uncertainties down to <1.3 m depth (Fig. S16). Two calibration IRSL samples from the modern beach suggest nearly complete bleaching of the marine sand (Table S2). The three radiocarbon ages were made from empty chitin tubes of polychaetes worms, and two of them are consistent with IRSL ages (Fig. S7). We discarded a radiocarbon age that was much younger than expected from its sequential position and, therefore, may have been contaminated during sampling. To estimate the ages of the 24 ridges, we constructed a Bayesian age model of coastal plain progradation combining ten IRSL (Excluding the four calibration samples) and two radiocarbon ages (see Methods), which extends between 4399 ± 154 yrs BP (the oldest dated ridge) and 1570 CE (date of first earthquake in the historical record). The agreement index of our model (a measure of the agreement between the prior model and observational data expressed in terms of likelihood) is 106.4% suggesting it reproduces the ages well (Fig. 3a, b and Fig. S18).

a Mean ridge ages from OxCal age model (see methods) with 1 SD uncertainties. Timing of historical earthquakes indicated by vertical lines. b Time interval between ridges and historical earthquakes (with interquartile range uncertainties). c Shoreline change rates for individual ridges (with upper and lower quartiles). Stippled lines show the interseismic rate between 1941 and 2010, and the postseismic rate between 2010 and 202140. d Evolution of along-strike ridge tilt (with 1 SD uncertainties), red and green lines show linear regressions with and without ridge-length weighting.

The modeled time intervals between successive beach ridges have a bimodal population reproduced by a mixed normal distribution (p value = 0.49) (Fig. 4), and we can reject the hypothesis of a time-independent Poisson distribution (Fig. S19a). We identify three distinct stages of coastal plain evolution (Fig. 3a–c): Stage I, between 4.4 and 3.0 kyr with a 214 ± 75 yr average interval and progradation rates of 0.1–0.8 m/yr; Stage II, between 2.9–1.8 kyr with a 65 ± 22 yr average interval and progradation rates of 0.3–2.1 m/yr; and Stage III, between 1.7–0.6 kyr with an average 243 ± 55 yr interval and progradation rates of 0.1 − 1.0 m/yr. The CoV of stages I, II, and III is 0.35, 0.33, and 0.23; and the burstiness is −0.48, −0.50, and −0.63, respectively. The average interval of the entire ridge plain sequence intervals is 139 ± 94 yrs, with a CoV, burstiness, and memory of 0.68, −0.19, and 0.73, respectively. By combining the ridge intervals with those of the historical earthquakes, the average recurrence time is 135 ± 89 yrs resulting in a CoV, burstiness, and memory of 0.66, −0.21, and 0.84, respectively (Fig. 4). CoV and skewness values of recurrence intervals are consistent with estimates from other subduction zones (Fig. S19b).

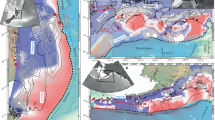

a Maule segment. b Valdivia segments. Accretionary wedge and subduction channel geometries30,32,33,50,53,60. RIN2 paleoseismic record from ref. 21. Differences in frontal accretionary wedge size, subduction channel thickness, and the presence of splay faults may influence megathrust friction and upper-plate compliance, respectively, affecting great earthquake recurrence periodicity.

The relative sea-level change estimated from the elevation of the oldest ridge formed at 4.5 kyrs accounting for coastal plain tilt, indicative meaning, and sea level predicted from 24 different glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) models43,44,45, (Fig. S20) suggest that 44–74% (range dependent on choice of GIA model) is the result of local tectonic uplift at a. maximum rate of 0.44 ± 0.15 m/kyr (Table S6). Our estimate is much lower than a previous study41 because we considered the indicative meaning and absolute sea level. The mean progressive tilt rate of the beach ridge sequence is 0.0083 ± 0.0038°/kyr (or 0.0066 ± 0.0038°/kyr using linear regression weighted by ridge length) (Fig. 3d). Our tilt rate is lower than the previous estimate of 0.022 ± 0.002°/kyr41, possibly due to the better accuracy of our topographic data. Swales, in turn, do not show a congruent tilt progression (Fig. S21), probably because of flooding during rainy periods and associated fine-grained sedimentation that smoothed the topography. Average progressive tilt rates for Stages I, II, and III are 0.023 ± 0.015, 0.0046 ± 0.01, and 0.0069 ± 0.002, respectively, suggesting a similar underlying process with higher variability during Stage II (Fig. S22).

Discussion

Great earthquake recurrence record from the ISM coastal plain

We interpret the continuous topographic, stratigraphic, and geochronologic signature of the ISM coastal plain geomorphic barcode as a record of seismic cycles over the past 4.5 kyr, based on the 2010 earthquake cycle modern analog40. We propose that each ridge-swale pair records an interseismic period between two consecutive great earthquakes, and therefore we interpret the time interval between adjacent ridge-swale pairs as a proxy for the earthquake recurrence interval. Land-level changes estimated between 1804 and 202139,40 show subsidence between and after the 1835 and 2010 earthquakes and uplift during these events, therefore discarding aseismic uplift as a possible mechanism for the emergence of the ISM coastal plain. GPR profiles showed that the most recent ridges have been buried below the wide frontal dune40, and IRSL ages collected from the dune (Table S1) suggest these buried ridges are likely associated with historical earthquakes. These interpretation is also supported by dune migration patterns revealed by aerial images back to 1941 showing progressive exhumation of older ridges40. The modern beachfront was not largely affected by the 2010 tsunami, which was associated with runups of only 2.9 m46, and therefore, we infer that the beach ridge plain was not affected by earlier tsunamis. Because of the unique setting of this island away from major sources of terrestrial sediment supply such as Andean rivers, relative sea-level changes associated with the seismic cycle and local sand supply from marine depth and sea-cliff erosion have controlled the progressive construction of the ridge-swale plain.

The four historical earthquakes in the Maule segment between 1570 and 1835 occurred periodically every 88 ± 5 yrs. Interestingly, this range of recurrence is similar to the interval between paleoearthquakes of Stage II (65 ± 22 yrs). However, Stage II includes 8 intervals with a shorter average recurrence of 43–62 yrs between 2.3–2.9 kyr. These short intervals are characterized by narrow ridges associated with high progradation rates (Figs. 2d, 3c). Between the 1835 and 2010 events, the recurrence time doubled to 175 years, similar to the intervals of Stage I (214 ± 75 yrs) and Stage III (243 ± 55 yrs). These stages are characterized by wider ridges and lower progradation rates (Figs. 2d, 3c), similar to Holocene beach ridge plains in Australia that have been associated with long, multi-centennial build-up times47,48. Therefore, changes in recurrence intervals are consistent with variations in beach ridge morphometry, suggesting both are controlled by the same underlying process – the seismic cycle. The similarities between recurrence times estimated from our geomorphic barcode record with those from historical events and from a 600-yr-long geologic record25, together with the progressive and continuous changes in measured recurrence intervals (rather than stochastic) suggest that these changes are robust. Interestingly, both the historical and paleoseismic recurrence intervals alternate between short (<100 yr) and long (~200 yr) values, likely associated with tectonic processes.

The ISM paleoseismic record suggests weakly periodic earthquake recurrence intervals, consistent with records from most subduction zones5. In terms of recurrence intervals of great megathrust earthquakes, the Maule segment exhibits a supercycle behavior, similar to the multi-millennial record of great earthquakes in Cascadia12, as well as in the subduction zones off Sumatra and Tohoku2,5,13,16,17. Clustered earthquakes, as observed during late Stage II, are not common but have been inferred from tsunami and turbidite records in Cascadia2,12, as well as from corals in Sumatra49. Progradation of the ISM coastal plain has occurred at an average rate of 0.6 m/yr (Fig. 3c), similar to the interseismic rate measured between 1941 and the 2010 earthquake40. In turn, between 2.9 and 2.3 kyr (Stage II), progradation rates reached 2.1 m/yr (Fig. 3c), similar to the postseismic rate measured during the decade after the 2010 earthquake40. These high rates may reflect the protracted effect of the last over-imposed postseismic progradation during a cluster of earthquakes separated by very short time intervals, as opposed to the long interseismic intervals observed during Stage I and III (Fig. 3a, b).

Possible link between megathrust earthquakes and splay faulting at millennial scale

Slip along the Santa María splay fault was inferred during the 2010 earthquake based on fresh surface ruptures along previously mapped faults50. Slip on upper-plate faults was triggered after the Maule earthquake including a Mw 7.0 earthquake29,51. Although splay faulting has been triggered during only a few great megathrust earthquakes, several lines of evidence suggest such secondary faults may commonly accompany great interplate events52,53,54,55,56,57.

InSAR data showed that ISM was tilted parallel to the margin during the 2010 earthquake (Fig. 1c), and we found that the number of beach ridges multiplied by the 2010 coseismic tilt angle equals the total coastal plain tilt (Fig. 2b, c). This suggests a similar underlying mechanism over the past 4.5 kyr. ISM tilt has been related to the growth of a reverse fault-cored anticline rooted in the megathrust31, and therefore the relation between coseismic tilt during the 2010 earthquake and coastal plain tilt (Fig. 2b) suggests that splay faulting may have accompanied previous earthquakes (Fig. S21). Modeling of uplift rates across the Santa María splay fault system over the past 50 kyr suggests it played a major role in deformation at ISM and across the surrounding Arauco Bay53. These changes may also explain the large variability in tilt rates estimated during Stage II in contrast to rather constant tilt rates during Stage I and III, by activation of different branches of the splay fault system. Our results support the notion that splay fault slip has commonly accompanied past great megathrust earthquakes along the Maule segments.

Tectonic control on megathrust earthquake periodicity in the Maule and Valdivia segments

With a CoV of 0.66 and B of −0.21, the Maule segment is less periodic than its south-neighboring Valdivia segment, characterized by a CoV between 0.32 and 0.5 and B between −0.52 and −0.34 (Fig. 4)21. However, the positive M of 0.73 at Maule indicates that consecutive recurrence intervals tend to be more similar than at Valdivia, where M ~ 0 (estimated from the CAL1 and RIN2 records21) suggesting different successive intervals. The lower CoV (0.35, 0.33, and 0.23) and B (−0.48, −0.50, and −0.63) values for the three stages at ISM confirm a very periodic recurrence interval within each stage in contrast to the overall weakly periodic behavior for the entire sequence. Therefore, changes in the tectonic boundary conditions of the Maule segment at the timescale of 1 to 2 kyr are apparently responsible for its less periodic recurrence behavior with respect to Valdivia.

While most of the geometric (convergence rate, megathrust dip, and strike, incoming plate relief) and rheologic (thermal regime, lithospheric thickness, forearc density, and composition) boundary conditions are relatively similar in both segments, they do exhibit some tectonic differences. Although the trench along both segments is filled with about 2 km of sediments, these are mostly underplated along a thick subduction channel and basally accreted below the continental shelf at Valdivia33, while mostly frontally accreted at Maule32. These accretionary differences result in different taper angles, which because the continental framework is similar at both segments, have been interpreted as higher effective basal friction at Valdivia34,35. Higher friction implies that the megathrust may sustain higher stresses58 allowing for the longer interseismic periods and larger earthquake magnitudes at Valdivia with respect to Maule. However, differences in basal friction are expected to act over >105 yr timescales and, therefore, not responsible for the 1–2 kyr change in earthquake recurrence behavior observed at ISM.

Upper-plate deformation is another difference between the Maule and Valdivia segments. The Maule forearc is characterized by widespread active splay faulting below the shelf-slope transition30, within the continental shelf53,59, and along the coastline51,60. In turn, faults along the Valdivia offshore forearc are sealed by Plio-Quaternary sediments and thus no longer active61. The differences in upper-plain strain between these segments are further underscored by the deformation style along the Main Cordillera, which is characterized by bivergent foothill thrust fronts along Maule, while at Valdivia deformation is localized along a strike-slip fault system that straddles the axial volcanic arc (Figs. 1a, 4b). Margin-normal upper-plate strain is higher at Maule and accounted for by several contractional structures extending across the offshore forearc60. At Valdivia, in turn, margin-normal strain is lower, and plate convergence is mostly accounted for by great earthquakes, which may, therefore, reach larger magnitudes than at Maule.

Widespread splay faulting results in a less compliant upper plate, and if splay faulting frequently accompanies megathrust earthquakes at Maule, then interseismic strain is released both by megathrust and splay fault slip. Therefore, we propose that differences in upper-plate strain and megathrust friction between the Maule and Valdivia segments may explain the variation in recurrence rate and periodicity. Because splay faults have complex geometries, their activation may interfere with the megathrust seismic cycle, ultimately conditioning the centennial-scale changes in recurrence intervals observed at ISM over the past 4.5 kyr. Our study highlights the possible influence of margin-scale tectonic features on the recurrence behavior of great earthquakes as revealed by comparisons of long (>10 events) paleoseismic records, with implications on their use for estimating the probability of forthcoming earthquakes.

Methods

Ground-penetrating radar surveys

We surveyed three 1650, 2110, and 2578 m long GPR profiles across the ISM coastal plain using a MALA Pro-Ex control unit with a 250-MHz antenna (Fig. S10). To search for suitable sites for excavations and sample collection, we used a GSSI UtilityScan instrument with a 350-MHz antenna (Figs. S12–S14). We surveyed topography with a Trimble R8S RTK GNSS instrument and calculated point coordinates in the SIRGAS datum using the Trimble Business Center v5.2 software, which is referred to mean sea level (MSL), using the permanent GNSS station STAM (location in Fig. 1c). We verified the MSL reference level by surveying a SHOA benchmark at Puerto Sur pier, which had been referred to MSL using a tide gauge station installed during a previous study39,50. We processed GPR data and visualized the results using the GSSI RADAN 7 software and the MatGPR R3.1 package for Matlab®62. We followed a standard processing routine63, including dewow filtering, zero-time correction, horizontal background removal, gain adjustments, bandpass filtering, and topographic corrections. The interpretation of GPR images was validated with detailed stratigraphic leveling in five 1.2 to 1.8 m-deep pits (Figs. S12–S14; pits 11C and 24 in Fig. S15). Responder Internal Notes: The author contacted

Morphometric analysis using high-resolution topography

We collected 474 vertical aerial photos using a Sensefly Ebee drone in February 2016 and used the Pix4Dmapper v.4 software to obtain an orthophoto mosaic and point cloud with an average density of 43.3 points/m2. Using the Lastools software, we produced a gridded DEM with 0.15 m resolution, which we referenced to MSL (SIRGAS datum) using ground control points collected with a Trimble R8 RTK GNSS instrument (Fig. S23a). The difference between DEM and RTK elevations follows a normal distribution with no artificial trends or distortions (Fig. S23b–d). We calculated the contour curvature of the DEM (a second numerical derivative of elevation) to automatically delimitate crests and valleys of ridges and swales using the TopoToolbox 2 curvature function64,65, which we classified to obtain 5139 equidistant points at 10-m spacing. Using the elevation of these points, we calculated for each ridge and swale the strike and along-strike tilt with 95% confidence intervals. Using the elevation of all ridges and swales, we fitted a 17 km2 planar surface and compared its tilt and strike with those of the ridges and swales. We evaluated the fit agreement by determining that residuals are not significantly different from a Gaussian distribution using the X2 criteria at 95% confidence. We compared the coastal plain tilt with the coseismic tilt during the 2010 Maule earthquake obtained from an ALOS (Advanced Land Observing Satellite) interferogram50. Finally, we calculated the number of 2010 earthquake-like events necessary for the difference between the total plain tilt and the 2010 tilt to be zero. We also calculated the along-strike topography of the modern beach to search for tilt and calculated the Indicative Meaning (IM) of modern ridges and swales reference water level42.

Because ridges are locally covered by dune fields and eroded by a single stream that drains the island’s highlands (Fig. S11). We analyzed the across-strike topography using a composite profile that integrates the three long profiles surveyed with GPR and RTK (Fig. 2a, d). These three profiles were merged by fitting their topography using a dynamic time-warping function66. Using the composite profile, we calculated the morphometric parameters of each ridge, including relief, width, skewness, and seaward and landward slopes (Fig. S9).

Bayesian age modeling

We collected a total of 18 sediment samples for luminescence dating (14 from the ridges, 2 from the modern beach, and 2 from the frontal dune) and three samples of empty chitin tubes of polychaetes worms from ridges 11, 17, and 24 for radiocarbon dating (details in Supplementary Text). The two samples from the modern beach corroborated the nearly complete resetting of the luminescence signal, while the two dune samples support the burial of ridges associated with the historical earthquakes. We used ten IRSL and two radiocarbon ages in a Bayesian model of coastal plain progradation (Fig. 1d), which considered a Sequence where each of the 24 ridges corresponds to a different Phase (interseismic time) separated by a Boundary (coseismic time) obtaining the time Interval (recurrence) of these 24 Phases67. We excluded the radiocarbon date of the ridge 17, because the calibrated value is 221 ± 200 years younger than the preceding ridges, an effect that may have resulted from contamination, and that is not consistent with the sequential order from the other 12 ages (Fig. S17 and Table S5). We considered the 68.3% (1-sigma) range for the modeled ages (OxCal code may be found in the Supplementary Text) and the median with the interquartile range for the intervals. We evaluated the time-independence of recurrence intervals using a Poissonian recurrence model and calculated the best distribution of recurrence times5,68,69. We also calculated the coefficient of variation (CoV), burstiness (B), and memory coefficient (M)14. We used these values to compare our paleoseismological record from the Maule segment with a record from the neighboring Valdivia segment21. Both include the largest magnitude earthquakes of each segment based on comparisons with modern analogs.

We used the modeled ages to analyze the tilt variation of each ridge over time by fitting a linear regression and a linear regression weighted by ridge length to the data. The same calculation was performed for each of the three Stage separately, excluding the oldest ridges that are shorter than 500 m. We then calculated the shoreline change rate under the assumption that each ridge approximates a paleo shoreline and compared it with modern pre- and post-2010 progradation rates40. Finally, we calculate the percentage of the coastal plain elevation attributed to tectonic uplift and mean uplift rates for ridges with absolute ages. We accounted for ridge elevation, coastal plain tilt, indicative meaning (using the modern berm elevation with respect to MSL as sea-level marker), and absolute sea level from 24 GIA models (ICE-5G44 and ICE-6G45) with different values of mantle viscosity (5 × 1019 Pa s, 8 × 1019 Pa s, 1 × 1020 Pa s, and 2 × 1020 Pa s) and lithospheric thickness (71, 96, and 120 km)43 (Fig. S20 and Table S6).

Data availability

Digital elevation model and ground-penetrating radar data, as well as the morphometric, OxCal model and recurrence intervals data presented in this article are available at the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/1397247770, in the article itself and in the Supplementary Information in text, graph, table and code format. For more information, please contact the corresponding author.

Code availability

All the morphometric analysis was made with TopoToolbox 2 - MATLAB-based software64. The OxCal code for Bayesian age modeling is provided in the Supplementary Information. For more information, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Salditch, L. et al. Earthquake supercycles and long-term fault memory. Tectonophysics 774, 228289 (2020).

Goldfinger, C., Ikeda, Y., Yeats, R. S. & Ren, J. Superquakes and supercycles. Seismol. Res. Lett. 84, 24–32 (2013).

Satake, K. & Atwater, B. F. Long-term perspectives on giant earthquakes and tsunamis at subduction zones. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 35, 349–374 (2007).

Stein, S., Geller, R. J. & Liu, M. Why earthquake hazard maps often fail and what to do about it. Tectonophysics 562-563, 1–25 (2012).

Moernaut, J. Time-dependent recurrence of strong earthquake shaking near plate boundaries: a lake sediment perspective. Earth Sci. Rev. 210, 103344 (2020).

Kopp, H. Invited review paper: the control of subduction zone structural complexity and geometry on margin segmentation and seismicity. Tectonophysics 589, 1–16 (2013).

Olsen, K. M. et al. Thick, strong sediment subduction along south-central Chile and its role in great earthquakes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 538, 116195 (2020).

Moreno, M. et al. Chilean megathrust earthquake recurrence linked to frictional contrast at depth. Nat. Geosci. 11, 285–290 (2018).

Bassett, D., Sandwell, D. T., Fialko, Y. & Watts, A. B. Upper-plate controls on co-seismic slip in the 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Nature 531, 92–96 (2016).

Gao, X. & Wang, K. Rheological separation of the megathrust seismogenic zone and episodic tremor and slip. Nature 543, 416–419 (2017).

Julve, J. et al. Recurrence time and size of Chilean earthquakes influenced by geological structure. Nat. Geosci. 17, 79–87 (2024)

Kelsey, H. M., Nelson, A. R., Hemphill-Haley, E. & Witter, R. C. Tsunami history of an Oregon coastal lake reveals a 4600 yr record of great earthquakes on the Cascadia subduction zone. GSA Bull. 117, 1009–1032 (2005).

Sieh, K. et al. Earthquake supercycles inferred from sea-level changes recorded in the corals of West Sumatra. Science 322, 1674–1678 (2008).

Goh, K. I. & Barabási, A. L. Burstiness and memory in complex systems. Europhys. Lett. 81, 48002 (2008).

Kempf, P. & Moernaut, J. Age uncertainty in recurrence analysis of Paleoseismic records. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB021996 (2021).

Rubin, C. M. et al. Highly variable recurrence of tsunamis in the 7,400 years before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Nat. Commun. 8, 16019 (2017).

Satake, K. Geological and historical evidence of irregular recurrent earthquakes in Japan. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 373, 20140375 (2015).

Herrendörfer, R., van Dinther, Y., Gerya, T. & Dalguer, L. A. Earthquake supercycle in subduction zones controlled by the width of the seismogenic zone. Nat. Geosci. 8, 471–474 (2015).

Philibosian, B. & Meltzner, A. J. Segmentation and supercycles: a catalog of earthquake rupture patterns from the Sumatran Sunda Megathrust and other well-studied faults worldwide. Quat. Sci. Rev. 241, 106390 (2020).

Rosenau, M. & Oncken, O. Fore-arc deformation controls frequency-size distribution of megathrust earthquakes in subduction zones. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 114 (2009).

Moernaut, J. et al. Larger earthquakes recur more periodically: new insights in the megathrust earthquake cycle from lacustrine turbidite records in south-central Chile. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 481, 9–19 (2018).

Moreno, M. et al. Toward understanding tectonic control on the Mw 8.8 2010 Maule Chile earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 321-322, 152–165 (2012).

Moreno, M. S., Bolte, J., Klotz, J. & Melnick, D. Impact of megathrust geometry on inversion of coseismic slip from geodetic data: application to the 1960 Chile earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

Ely, L. L., Cisternas, M., Wesson, R. L. & Dura, T. Five centuries of tsunamis and land-level changes in the overlapping rupture area of the 1960 and 2010 Chilean earthquakes. Geology 42, 995–998 (2014).

Dura, T. et al. Subduction zone slip variability during the last millennium, south-central Chile. Quat. Sci. Rev. 175, 112–137 (2017).

Molina, D., Tassara, A., Abarca-del-Rio, R., Melnick, D. & Madella, A. Frictional segmentation of the Chilean megathrust from a multivariate analysis of geophysical, geological, and geodetic data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126 (2021).

Kempf, P. et al. Coastal lake sediments reveal 5500 years of tsunami history in south central Chile. Quat. Sci. Rev. 161, 99–116 (2017).

Lomnitz, C. Major earthquakes and tsunamis in Chile during the period 1535 to 1955. Geol. Rundsch. 59, 938–960 (1970).

Lieser, K. et al. Splay fault activity revealed by aftershocks of the 2010 Mw 8.8 Maule earthquake, central Chile. Geology 42, 823–826 (2014).

Geersen, J. et al. Active tectonics of the South Chilean marine fore arc (35°S–40°S). Tectonics https://doi.org/10.1029/2010TC002777 (2011).

Melnick, D., Bookhagen, B., Strecker, M. R. & Echtler, H. P. Segmentation of megathrust rupture zones from fore-arc deformation patterns over hundreds to millions of years, Arauco peninsula, Chile. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005788 (2009).

Contreras-Reyes, E., Flueh, E. R. & Grevemeyer, I. Tectonic control on sediment accretion and subduction off south central Chile: Implications for coseismic rupture processes of the 1960 and 2010 megathrust earthquakes. Tectonics https://doi.org/10.1029/2010TC002734 (2010).

Bangs, N. L. et al. Basal accretion along the South Central Chilean margin and its relationship to great earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB019861 (2020).

Maksymowicz, A. The geometry of the Chilean continental wedge: tectonic segmentation of subduction processes off Chile. Tectonophysics 659, 183–196 (2015).

Maksymowicz, A. et al. Deep structure of the continental plate in the South-Central Chilean margin: metamorphic wedge and implications for megathrust earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB021879 (2021).

Melnick, D., Bookhagen, B., Echtler, H. & Strecker, M. Coastal deformation and great subduction earthquakes, Isla Santa Mar??a, Chile (37 S). Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 118, 1463–1480 (2006).

Melnick, D., Moreno, M., Motagh, M., Cisternas, M. & Wesson, R. L. Splay fault slip during the Mw 8.8 2010 Maule Chile earthquake. Geology 40, 251–254 (2012).

Darwin, C. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle, Between the Years 1826 and 1836: Journal and Remarks Vol. 3 (Henry Colburn, 1839).

Wesson, R. L., Melnick, D., Cisternas, M., Moreno, M. & Ely, L. L. Vertical deformation through a complete seismic cycle at Isla Santa María, Chile. Nat. Geosci. 8, 547–551 (2015).

Aedo, D. et al. Decadal coastal evolution spanning the 2010 Maule earthquake at Isla Santa Maria, Chile: framing Darwin’s accounts of uplift over a seismic cycle. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 48, 2319–2333 (2023).

Bookhagen, B., Echtler, H. P., Melnick, D., Strecker, M. R. & Spencer, J. Q. G. Using uplifted Holocene beach berms for paleoseismic analysis on the Santa María Island, south-central Chile. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026734 (2006).

Shennan, I. Handbook of Sea‐Level Research (Wiley, 2015).

Garrett, E. et al. Holocene relative sea-level change along the tectonically active Chilean coast. Quat. Sci. Rev. 236, 106281 (2020).

Peltier, W. R. Global glacial isostasy and the surface of the ice-age earth: the ice-5G (VM2) model and GRACE. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 32, 111–149 (2004).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: the global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Fritz, H. et al. The Chile tsunami of 27 February 2010: field survey and modeling. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts 03 (2011).

Bristow, C. S. & Pucillo, K. Quantifying rates of coastal progradation from sediment volume using GPR and OSL: the Holocene fill of Guichen Bay, south-east South Australia. Sedimentology 53, 769–788 (2006).

Brooke, B. et al. Influence of climate fluctuations and changes in catchment land use on Late Holocene and modern beach-ridge sedimentation on a tropical macrotidal coast: Keppel Bay, Queensland, Australia. Mar. Geol. 251, 195–208 (2008).

Philibosian, B. et al. Earthquake supercycles on the Mentawai segment of the Sunda megathrust in the seventeenth century and earlier. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 642–676 (2017).

Melnick, D., Moreno, M., Motagh, M., Cisternas, M. & Wesson, R. Splay fault slip during the Mw 8.8 2010 Maule Chile earthquake: reply. Geology 40, 251–254 (2012).

Jara-Muñoz, J. et al. The cryptic seismic potential of the Pichilemu blind fault in Chile revealed by off-fault geomorphology. Nat. Commun. 13, 3371 (2022).

Li, S., Moreno, M., Rosenau, M., Melnick, D. & Oncken, O. Splay fault triggering by great subduction earthquakes inferred from finite element models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 385–391 (2014).

Jara-Muñoz, J. et al. Quantifying offshore fore-arc deformation and splay-fault slip using drowned Pleistocene shorelines, Arauco Bay, Chile. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 4529–4558 (2017).

Plafter, G. Surface Faults on Montague Island Associated with the 1964 Alaska Earthquake. Report No. 543G, 50 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967).

Hollingsworth, J., Ye, L. & Avouac, J.-P. Dynamically triggered slip on a splay fault in the Mw 7.8, 2016 Kaikoura (New Zealand) earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3517–3525 (2017).

Shyu, J. B. H. et al. Upper-plate splay fault earthquakes along the Arakan subduction belt recorded by uplifted coral microatolls on northern Ramree Island, western Myanmar (Burma). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 484, 241–252 (2018).

DePaolis, J. M. et al. Repeated coseismic uplift of coastal lagoons above the Patton Bay Splay Fault System, Montague Island, Alaska, USA. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 129, e2023JB028552 (2024).

Sallarès, V. & Ranero, C. R. Upper-plate rigidity determines depth-varying rupture behaviour of megathrust earthquakes. Nature 576, 96–101 (2019).

Bernhardt, A. et al. Controls on submarine canyon activity during sea-level highstands: the Biobío canyon system offshore Chile. Geosphere 11, 1226–1255 (2015).

Maldonado, V., Contreras, M. & Melnick, D. A comprehensive database of active and potentially-active continental faults in Chile at 1:25,000 scale. Sci. Data 8, 20 (2021).

Echaurren, A. et al. Fore-to-retroarc crustal structure of the north Patagonian margin: How is shortening distributed in Andean-type orogens? Glob. Planet. Change 209, 103734 (2022).

Tzanis, A. matGPR Release 2: a freeware MATLAB® package for the analysis & interpretation of common and single offset GPR data. FastTimes 15, 17–43 (2010).

GSSI. RADAN 7 manual. https://www.geophysical.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/2010/GSSI-RADAN-2017-Manual.pdf (2017).

Schwanghart, W. & Scherler, D. Short communication: TopoToolbox 2 – MATLAB-based software for topographic analysis and modeling in Earth surface sciences. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2, 1–7 (2014).

Schmidt, J., Evans, I. S. & Brinkmann, J. Comparison of polynomial models for land surface curvature calculation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 17, 797–814 (2003).

Wang, Q. Dynamic time warping (DTW). https://github.com/wq2012/dynamic_time_warping/releases/tag/v2.2 (2023).

Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Williams, R. T., Goodwin, L. B., Sharp, W. D. & Mozley, P. S. Reading a 400,000-year record of earthquake frequency for an intraplate fault. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4893–4898 (2017).

Novack-Gottshall, P. & Wang, S. C. KScorrect: Lilliefors-corrected Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit tests. R package version 1.4.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=KScorrect (2019).

Aedo, D., Melnick, D., Cisternas, M. & Brill, D. “Tectonic control on great earthquake periodicity in south-central Chile” data. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13972477 (2024).

GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group 2022. The GEBCO_2022 Grid - a continuous terrain model of the global oceans and land. (NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC, 2022).

Danielson, J. J. & Gesch, D. B. Global Multi-Resolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010 (GMTED2010). Report No. 2011-1073 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research project was funded by the Millennium Scientific Initiative (ICM) of the Chilean government through grant NC160025, “Millennium Nucleus CYCLO The Seismic Cycle Along Subduction Zones”, Chilean National Fund for Development of Science and Technology Fondecyt grant 1240681 and the National Research and Development Agency (ANID) grant 21190535. We thank Bladimir Saldaña, Vicente Sepúlveda, Cristian Araya, and Diego Cárdenas for their help in the field; Laboratorio Geotsunami PUCV team for useful discussions during the paper preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A., M.C., and D.M. led the preparation of the manuscript and conceptualized the research. D.M. and M.C. obtained the main source of funding for this project. D.A., M.C., D.M., and D.B. collected field data, GPR surveys and assisted in logistics. D.A., D.M., and M.C. performed the photogrammetric reconstruction, morphometric analysis, and age modeling. D.B. performed the luminescence analysis. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Andrew Green and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aedo, D., Melnick, D., Cisternas, M. et al. Tectonic control on great earthquake periodicity in south-central Chile. Commun Earth Environ 5, 703 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01834-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01834-5