Abstract

Anthropogenic nitrogen inputs from the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin have caused substantial environmental challenges in the northern Gulf of Mexico, such as coastal eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, and seasonal hypoxia. Addressing these issues requires a better understanding of the complex sources of nitrogen, which include fertilizers, groundwater, manure, and sewage. In this study, we analyzed the nitrogen isotopic composition of dissolved nitrate and particulate nitrogen from the Wax Lake Delta, a major distributary of the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin that flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Our findings revealed that during the wet season, δ15N values of both nitrate and particulate nitrogen were consistently 2-3‰ lower compared to the dry season. This suggests that fertilizer-derived nitrogen, which has lower δ15N, is predominantly exported to the Gulf of Mexico during periods of high water discharge. These findings imply that adjusting fertilizer application timing could help reduce nitrogen loading and mitigate its environmental impact on the Gulf of Mexico.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB) is the largest river basin in North America, accounting for approximately 80% of freshwater discharge and around 90% of total riverine nitrogen (N) input to the northern Gulf of Mexico (GoM)1,2. This region is a major agricultural hub, characterized by intensive cultivation and large amount of N fertilizer application3,4,5. Since 1950, the total N load from the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River system into the GoM has increased substantially, peaking in 1993, with fluctuating trends thereafter6. This escalation in N input has negatively impacted phytoplankton community composition and the extent of hypoxic zones in the northern GoM7,8,9. Despite decades of efforts to mitigate N loading, hypoxia areas in the northern GoM continue to exceed the target set by the Hypoxia Task Force, which aims to reduce the 5-year average size of hypoxic zone to less than 5000 km2 by 2035. Current observations indicate that the size of these zones is roughly three times the target10,11,12, significantly affecting marine ecosystems, coastal communities and economies dependent on the northern GoM.

Numerous studies indicate that anthropogenic N sources such as synthetic N fertilizers, groundwater, manure and human sewage are the primary contributors to the N load in the MARB5,6. Over the past decades, extensive use of N fertilizers in the MARB has significantly elevated N content in soil13,14,15. It is estimated that approximately 50% of the current dissolved nitrate (NO3-) load from the MARB to the northern GoM originated from ‘legacy N’ that has accumulated within the watershed for more than 30 years14,15,16,17. This ‘legacy N’ can also leach from soil into groundwater, contaminating water resources in the MARB12,15,16,17,18. Despite the pressing need to decrease N inputs, research on the transport mechanisms and timing of these anthropogenic N sources reaching the northern GoM remains scarce3,4,19.

Tracing and quantifying the transport of anthropogenic N to the northern GoM remains challenging due to the complexity of these sources. Although the U.S. Geological Survey provides long-term data on riverine N loads2, reliance solely on N concentrations and water discharge data is insufficient to distinguish between different anthropogenic N sources. This limitation restricts our understanding of how and when these N sources are transported to the GoM. Empirical modeling approaches have attempted to separate the different N sources using bottom-up methods3,20; however, these models are constrained by inherent uncertainties, including inadequately captured N biogeochemical processes and ecosystem interactions.

N isotopes are valuable tools for tracing N sources in natural environments21,22,23,24. Typically, synthetic N fertilizer and atmospheric deposition are characterized by lower 15N/14N values (or δ15N, where δ15N = [(15N/14N)sample/(15N/14N)atm N2 − 1] × 1000‰). In contrast, groundwater, human sewage and manure exhibit higher 15N/14N values due to biological processes such as denitrification and trophic enrichment23, which preferential consumes 14N relative to 15N23,25. For example, during denitrification where NO3− is consumed, 14N-NO3− is preferentially utilized over 15N-NO3−, resulting in the residual NO3- progressively enriched in 15N. Consequently, δ15N can help distinguish between low-δ15N N sources and high-δ15N endmember23,26.

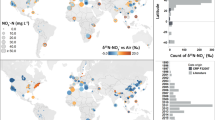

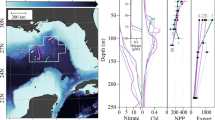

Despite its efficacy in identifying N sources, the use of natural-abundance NO3− isotopes was only briefly employed in the MARB during the 2000s. These studies suggested similar N sources and N-cycling processes in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers27,28. However, since 2010, there has been a lack of NO3− isotope data that can be compared with recent modeling results. This gap highlights the need for updated isotope data to corroborate these models. In addition, recent technological advancements have improved the sensitivity and precision of NO3− isotope measurements, offering the potential for more comprehensive studies29. In this study, we report the isotopic composition of NO3− and particulate nitrogen (PN) collected during two hydrological seasons from the Wax Lake Delta (WLD), a major distributary of the MARB (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Map of the study area in the Wax Lake Delta (WLD), Louisiana, USA. The blue symbols indicate the water and particle isotope sampling locations in the wet season, while the red symbols indicate the dry season. b Daily water discharge in 2021 (m3 s−1), with the arrows indicating the sampling time for this study. c Monthly dissolved inorganic nitrogen (NO3−, NH4+, NO2−) in the Wax Lake Delta. Note that NH4+ concentrations are consistently lower than 1 μM throughout the year, indicating quantitative nitrification in the WLD watershed. Daily water discharge and nutrient data were obtained from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The locations can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

Seasonal changes in anthropogenic nitrogen inputs to the WLD and GoM

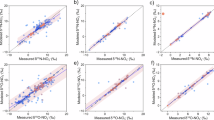

NO3− concentrations in the WLD peak during the wet season when water discharge is high, and decrease during the dry season when discharge is low (Fig. 1). This observation indicates a strong relationship between NO3− yield in the upstream MARB and hydrological conditions. To quantify how NO3− flux responds to hydrological variations, we examined the concentration-discharge relationships of our samples. In various watersheds, these relationships for different solutes exhibit substantial variations due to hydrological and biogeochemical processes30,31,32,33. A ‘dilution’ scenario is characterized by decreasing ion concentrations with increasing water discharge, yielding a power-law exponent of −131. In contrast, in a ‘chemostatic’ scenario, ion concentrations remain relatively constant despite changes in water discharge, resulting in a near-zero power-law exponent34. Notably, our data show that NO3− concentrations increase with water discharge (power-law exponent = 0.118, Fig. 2a). This pattern suggests that NO3− becomes enriched under high discharge conditions in the Atchafalaya River, and a greater flow of NO3−-concentrated water is exported to the northern GoM during the wet season (Fig. 2a). This is consistent with the observations in other rivers influenced by anthropogenic N, such as the Seine, Potomac, Connecticut and Mississippi rivers32,35,36,37,38.

Relationship between (a) log nitrate (NO3−) concentrations (µM) and log water discharge (m−3 s−1) during the sampling period, (b) NO3− load (Gg d−1) and water discharge (m−3 s−1) during the sampling period, (c) δ15N-NO3− and log water discharge in the Wax Lake Delta during the wet and dry seasons and (d) seasonal δ15N values of suspended particle, water and concentration weighted nitrate + PN samples. Solid lines indicate linear correlations. Gray shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

The most important finding from the isotope data is the clear distinction between the wet and dry seasons (Figs. 2d, 3). The δ15N of both NO3− and PN are approximately 3‰ lower during the wet season compared to the dry season, suggesting a strong influence of hydrology on the N load to the GoM. Additionally, a statistically significant negative correlation was observed between δ15N-NO3− and water discharge (r2 = 0.33, p < 0.01; Fig. 2c). These observations mostly likely indicate that during periods of high water discharge, anthropogenic N with low δ15N values was preferentially introduced into the WLD River. However, as biogeochemical processes might also alter the δ15N values in the river, we first discuss the potential impact of river biogeochemical processes below.

Relationship between (a) δ15N-NO3− and the inverse of nitrate concentrations (1/NO3−) and (b) δ15N-NO3− and the natural log of NO3− concentrations (Ln[NO3−]). The δ15N endmembers (fertilizer, atmospheric deposition, and groundwater)67 were also plotted in a. Solid lines indicate linear regressions. Gray shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Nitrogen biogeochemical processes in the Wax Lake Delta catchment

When utilizing isotopes to trace the sources of anthropogenic N in a river, it is essential to account for the biogeochemical processes within the river system that may alter the isotopic composition of N sources. As various forms of N, such as NO3−, NH4+, and organic N, enters the catchment, they undergo a series of N transformation processes influenced by environmental conditions39,40. Nitrification and NO3− consumption are the primary N transformation processes affecting NO3− dynamics in the river. Nitrification involves the oxidation of NH4+ to NO3−, while NO3− assimilation and denitrification consume NO3− 41,42,43. In the case of the MARB, previous data suggests that NO3- is the dominant form of N in the river, which is consistent with our new data from the WLD river and observations from the U.S. Geological Survey in the lower Atchafalaya River at Morgan City (Fig. 1b)8,14,44. The water column of WLD is well oxygenated and NH4+ concentrations are two orders of magnitude lower than NO3− concentrations, suggesting near-complete nitrification and minimal alteration of the isotopic composition of the source N by nitrification or denitrification in the river (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Phytoplankton NO3- assimilation may influence the isotopic composition of source N in the river, as this process preferentially consumes 14N relative to 15N with an isotope effect of ~5‰45. This process is expected to cause a negative correlation between δ15N-NO3− and the natural log of [NO3−] due to Rayleigh-style fractionation23,25. Indeed, during the wet season, we observed this negative correlation observed between δ15N-NO3− and the natural log of [NO3−], indicative of NO3− assimilation in the river (Fig. 2b). However, the change in δ15N-NO3− observed along the river is only ~1‰, suggesting that NO3− assimilation has a limited impact on altering δ15N-NO3− (Fig. 3). Similarly, δ18O-NO3− also showed little change along the river within each season (Supplementary Fig. 3).

In addition, we calculated the concentration-weighted δ15N of NO3− plus particulate nitrogen (PN). Since phytoplankton NO3− assimilation solely converts NO3− into PN, the concentration-weighted δ15N of the PN + NO3− should remain unaffected by phytoplankton NO3− consumption. Therefore, this parameter predominantly reflects the δ15N of the N sources to the WLD. The average concentration-weighted δ15N-(PN + NO3−) values were 6.4 ± 0.4‰ during the wet season and 9.2 ± 0.2‰ during the dry season, similar to those of 15N-PN and δ15N-NO3− in the dry and wet seasons, respectively (Fig. 2; Table 1). These results corroborate remarkable seasonal change in the δ15N of the N sources to the WLD (Table 1).

Thus, we conclude that although NO3− assimilation occurs in the WLD, its impact on the δ15N of both NO3− and PN appears to be limited. The concentration-weighted δ15N-(PN + NO3−) is insensitive to NO3− assimilation and should therefore reflect the δ15N of N sources. Consequently, the lower δ15N values observed during wet season most likely indicate additional inputs of anthropogenic N with low δ15N values. Synthetic N fertilizer is the most probable candidate for this low-δ15N anthropogenic N source23, as its application and transformation produce low-δ15N values in both NO3− and PN. In the following section, we provide a detailed discussion of anthropogenic N sources in the WLD.

Identification and quantification of nitrogen sources to the WLD and GoM

Our δ15N-NO3− values align with those reported in previous N isotopic studies conducted in the MARB27,46,47. This study further reveals distinctive δ15N patterns between the wet and dry seasons in the WLD. During the dry season, the WLD exhibits low N concentrations and high δ15N values, suggesting that reduced surface runoff decreased NO3− loading from soil to river, and groundwater becomes the dominant N source in the study area. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that groundwater can be the primary source of NO3− during low-flow periods across the United States18.

In the MARB, groundwater N is likely derived from “legacy” fertilizer N, as a portion of applied fertilizer N is infiltrated into the groundwater through the floodplain soils16,48. However, the δ15N of groundwater N is altered by denitrification under low-oxygen conditions, which preferentially removes 14N relative to 15N. As a result, although “legacy” fertilizer N may be the ultimate source of groundwater N, its original δ15N signature is modified. Consequently, the high δ15N values observed in the WLD during the dry season can be attributed to groundwater N23. Consistent with this interpretation, the relatively higher δ18O-NO3− values during the dry season, compared to the δ18O of the water in the MARB, likely result from denitrification in the groundwater49,50,51.

In contrast, during the wet season, WLD is characterized by high N concentrations with lower δ15N values, suggesting an influx of low-δ15N N associated with high water discharge. There are two possible contributors of this low-δ15N N source: fertilizer N and atmospheric deposition. However, the rates of atmospheric N deposition in the MARB region are estimated to be at least one order of magnitude lower than the riverine N flux, suggesting that the atmospheric N deposition should minimally impact the WLD δ15N values52. Thus, fertilizer N is the most likely candidate for the low-δ15N N source in the WLD during the wet season. Once applied, fertilizer N, can be integrated into the soil and vegetation (Fig. 4). Intense precipitation during the wet season can flush soil fertilizer N and organic matter into the river, leading to increased N load and decreased in δ15N values of both δ15N-NO3- and δ15N-PN. Moreover, while manure and sewage are known sources of anthropogenic N in the region, their δ15N values are generally high (i.e., >9–10‰) and do not explain the low δ15N values observed during the wet season20,53. Consequently, we conclude that N sourced from surface fertilizers, rather than from manure/sewage (high δ15N), is preferentially exported to the northern GoM during periods of high water discharge.

Based on discussions above, we used a simple isotope mixing model to quantify the contributions of N sources to the WLD (Methods). As manure/sewage N cannot be the cause of low δ15N signature in the WLD during the wet season, we consider fertilizer and groundwater as the two primary sources to the N to the WLD in the model. Those sources carry distinct δ15N values, allowing us to quantify their relative contributions to total N load in the WLD (Supplementary Fig. 4). This simple model calculation shows that in the wet season, the contributions from fertilizer (~45%) are slight lower than groundwater (~55%). In the dry season, groundwater (~91%) becomes the dominant N source and fertilizer contributed about (~9%) to the MARB.

A recent modeling study used a bottom-up, spatially explicit distributed model to describe N flow and processes in landscapes in 4 large river basins including the MARB17. It was estimated that, groundwater is the dominant source of nitrogen (>50%) in the Mississippi River due to the “legacy N” leached from historical fertilizer application in soils, consistent with our isotope-based top-down estimation in the WLD. One challenge acknowledged by the bottom-up modeling studies is that their sole method of validation is comparing their model outputs with N concentrations and discharge data in rivers. In this context, our isotope data provides new information to validate these model results. In addition, our data revealed that, compared to manure or sewage, fertilizer-derived N is preferentially transported to the WLD during periods of high water discharge. This may be attributed to the relative ease of fertilizer leaching compared to manure or sewage, a factor not yet considered in modeling studies. Future modeling efforts should incorporate different transport mechanisms for various anthropogenic N sources.

Potential applications to historical variations of N sources to the GoM

The δ15N-water discharge relationship observed in the WLD in this study, combined with the isotope mixing model, may enable the estimation of historical anthropogenic N sources in the northern GoM. To demonstrate this approach, we utilized historical N load data from 2010 to 2022 from Atchafalaya River and calculated the contributions of fertilizer and groundwater to the N load entering the GoM (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Data). The results show that during the wet season, the contribution of N from fertilizer source significantly increased to the overall N load (Supplementary Fig. 6). These findings collectively demonstrate that the N input from various sources are strongly influenced by hydrological conditions in the MARB.

While this approach show promise for quantifying N sources in the MARB, we acknowledge two limitations. First, although our sample set covers multiple sites and water depths in the WLD, it represents only two sampling campaigns and does not capture the full intra-annual variability of δ15N in the MARB. We recommend future studies to focus on long-term isotope monitoring in the MARB to corroborate and extend the findings of this study. Second, the observed δ15N-discharge relationship might vary across the sub-watersheds and over time in the MARB. Collecting more N isotope data over longer periods would better quantify the spatiotemporal pattern of δ15N-discharge relationship across the MARB.

Implication for nitrogen management in the MARB

The expansion of the eutrophication and hypoxia zones in the northern GoM has been primarily attributed to substantial anthropogenic N loads originating from the MARB6,8,44. Despite the growing urgency to reduce N inputs, there remains a lack of adequate research on the transport mechanisms and timing of different anthropogenic N sources reaching the northern GoM. Although our study was limited to two hydrologic seasons within one year, our results provide evidence that fertilizer-derived N is preferentially transported into the GoM during periods of high water discharge, rather than N from manure or sewage N. Future studies should continue to monitor the isotopic composition in the MARB to further constrain the contribution of these anthropogenic N sources to the northern MARB.

Given that climate models project an increase in extreme precipitation events in the MARB under global warming11,54,55, it is expected that more fertilizer N will be transported from the catchment into the northern GoM. To effectively mitigate and reduce N loading into the northern GoM, it is imperative to improve current N management strategies, and our study provides crucial information towards this goal. For instance, implementing measures such as avoiding N fertilizer application during periods of heavy precipitation, addressing groundwater NO3− contamination, and transitioning from monoculture practices (e.g., corn-soybean) to diversified crop systems that rely on N-fixation and require less fertilizer (e.g., incorporating cover crops) should be considered12,17,56. Previous work has shown that applied N fertilizer is not fully taken up by plants, with a notable portion being stored in the soil57. Therefore, optimizing the timing and efficiency of fertilizer application through strategic management necessary. Implementing these practices is expected to effectively reduce the N load into the northern GoM. Furthermore, conducting comprehensive studies at various temporal and spatial scales, using N isotopes, is crucial for a better understanding of the impact of fertilizer-derived N on N loading in the MARB and to inform future management efforts.

Methods

Study sites

This study was carried out in the Wax Lake Delta (WLD), Louisiana, United States (29.51033°N, 91.4449°W) (Fig. 1a), a relatively modern river-dominated subdelta of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya river systems28,58. The Wax Lake Outlet was dredged in 1941 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood protection purposes, supplied the WLD with fluvial water and sediment from Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin59. Annual water discharge was about 3605 m3 s−1 in the WLD and as measured at USGS Calumet, LA, with high water discharge from January to July (wet season) and low water discharge from August to December (dry season) (Fig. 1b)60,61. The MARB has been heavily influenced by anthropogenic activities over the last century, which leads to the export a substantial amount of N to the northern Gulf of Mexico6,54. To test the whether the water column is well-mixed, we collected water samples from multiple sites and multiple depth during each sampling trip, and no significant differences were observed. This indicates the water column was well-mixed with no significant depth variation, as indicated by the δ15N results (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Sample collection

Samples and flow data were collected by the NASA Delta-X project. Field sampling in WLD was carried out from March 24–31 (wet season) and August 17–24 (dry season), in 2021. Water discharge and temperature data were collected using a Teledyne RiverPro acoustic Doppler current profiler that was calibrated before the cruise62. River water and rainwater samples for nutrient and isotope analysis were collected with a syringe and filtered through a Millipore polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter (0.2 µm) into a high-density polyethylene bottle (40 ml). The bottles were acid washed in 10% HCl, rinsed, and dried prior to each use. All water samples were stored frozen at −20 °C until analysis. For collecting suspended particulate samples, 8 L of river water was collected using a Van Dorn sampler63. Within 24 h after collection, each water sample was filtered through 0.22 µm PES (Polyethersulfone) membrane filters at the field lodging station. The PES filters with suspended particulate samples on them were kept frozen and transported back to the California Institute of Technology. In the laboratory, the suspended particles were separated from the filter by sonicating in MilliQ water and scratching gently using a spatula. The separated sediment samples were oven-dried at 60 °C. The dried samples were ground and homogenized using a mortar and pestle. Splits of each sample were taken for total N and δ15N-PN analysis. In addition to field sampling, the water discharge (daily-monthly resolutions) and nutrients data (monthly resolution) from the Morgan City gaging station (USGS gage 07381600) located downstream of the Atchafalaya River, were used in this study.

Sample analyses

NO3− concentrations in the water samples were measured by the chemiluminescence method64. Briefly, NO3- was reduced to nitric oxide using a vanadium (V3+) solution at 95 °C. The nitric oxide was then quantified with a Teledyne 200 EU chemiluminescence analyzer. The precision of this method is better than 5%. Measurements of δ15N-NO3− and δ18O-NO3− in WLD water samples were performed in the Stable Isotope Biogeochemistry Lab at Boston College, using the “denitrified method” described by Sigman et al.65,66. The denitrified method uses cultured denitrifying bacteria (P. aureofaciens) that lack the nitrous oxide reductase activity, which quantitively converts NO3− to N2O gas analyte. The N2O produced from each sample were extracted, concentrated, and purified using a customized Gas Bench and analyzed on a Thermo Delta V plus continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). The international reference materials IAEA (δ15N = 4.7‰; δ18O = 25.6‰) and USGS 34 (δ15N = −1.8‰; δ18O = −27.9‰) were analyzed in each batch of samples and used for isotope data correction29. All stable isotope compositions are expressed as δ values, representing deviations in per mil (‰) from standards for δ15N-NO3− and δ18O-NO3−.

Where Rsample and Rstandard represent the measured isotopic ratios (e.g., 15N/14N or 18O/16O) for the sample and standard, respectively. The ratio of 15N/14N reference is N2 in the air and the 18O/16O reference is Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW). Analytical precision for international reference materials for δ15N-NO3− was better than 0.2 ‰, and for δ18O-NO3− was better than 0.3 ‰.

For PN and δ15N-PN measurements, splits of suspended sediment samples were analyzed using an Elemental Analyser Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry at the Marine Science Institute at the University of California Santa Barbara. Analytical uncertainties were within 0.17‰ for δ15N and 2% (relative percentage error) for the weight percentage of PN from repeated measurements of USGS-40 reference materials.

Isotope mixing model calculations

We employed a simple two end-member isotope mixing model to quantify the contributions of nitrate from fertilizer and groundwater sources in the WLD. During the dry season, low N concentrations and high δ15N values suggest that reduced surface runoff decreased NO3− loading from soil to river, and groundwater becomes the dominant N source in the study area. In contrast, during the wet season, lower nitrate and PN δ15N values indicate that fertilizer-derived N (characterized by low δ15N) is preferentially transported into the WLD during periods of high water discharge, rather than N from manure or sewage (which have high δ15N). Therefore, our isotopic mixing model considers only fertilizer and groundwater as primary N sources in the WLD. Manure and sewage were excluded from this model because they cannot account for the lower δ15N observed during the wet season. This is consistent with previous studies that suggest manure and sewage contribute minimally to the total nitrogen load compared to fertilizer and groundwater in the MARB6,20. Consequently, the mixing model is described by the following equations:

where f is defined as the proportional contribution to N from the respective sources. Subscripts e and g represent the NO3- sources from fertilizer (e) and groundwater (g), respectively. δ15N represent the isotope values. Fertilizer δ15N values were obtained from the literature (0 ± 2.1‰). Recent studies suggest that groundwater contributes significantly to NO3− flux during winter low-flow conditions in the United States18. Therefore, we used dry season δ15N values as the groundwater endmember in the mixing model. These values are comparable to previously analyzed groundwater δ15N values in the MARB, which averaged 9.8 ± 4.9‰, as well as to global nitrate isotope composition in groundwater67. To estimate the uncertainty of this two end-member isotope mixing model, we incorporated the variability of δ15N values measuring during the dry and wet seasons, along with those obtained from the literature and their associated errors.

Calculation of historical variations in N sources in the Atchafalaya River

The δ15N-water discharge relationship obtained from WLD may enable the estimation of historical anthropogenic N sources in the northern GoM. As an example, we applied this relationship to historical N load and discharge data from 2010 to 2022 from Atchafalaya River to calculate the contributions of fertilizer and groundwater to the N load entering the GoM (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Data). First, the historical N load was calculated by multiplying the historical water discharge by NO3− concentrations. obtained from USGS. Second, we used the correlation between water discharge and δ15N values to estimate the historical δ15N values. Next, we applied the isotope two end-member mixing model to determine the N load originating from fertilizer and groundwater sources (Supplementary Fig. 6). While this exercise has inherent uncertainty due to our limited data set, this approach can be extrapolated to more accurately quantify different N sources from the MARB to the GoM as more isotope data becomes available, especially when integrated with more complex biogeochemical models5,6.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data sets are available within the Supplementary Data and https://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dataset_lister.pl?p=41.

References

Dunn, D. E. Trends in nutrient inflows to the Gulf of Mexico from streams draining the conterminous United States, 1972-93. U.S. Geol. Surv. Water-Resources Investig. Rep. 96, 4113 (1996).

Battaglin, W. A., Aulenbach, B. T., Vecchia, A. & Buxton, H. T. Changes in Streamflow and the Flux of Nutrients in the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin, USA, 1980–2007 (2010); U.S. Geological Survey Scientiic Investigations Report 2009–164. USGS, Reston, VA.

Robertson, D. M. & Saad, D. A. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Sources and Delivery from the Mississippi/Atchafalaya River Basin: An Update Using 2012 SPARROW Models. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 57, 406–429 (2021).

Alexander, R. B. et al. Differences in phosphorus and nitrogen delivery to the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi River Basin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 822–830 (2008).

Tian, H. et al. History of anthropogenic Nitrogen inputs (HaNi) to the terrestrial biosphere: a 5 arcmin resolution annual dataset from 1860 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4551–4568 (2022).

Tian, H. et al. Long‐term trajectory of nitrogen loading and delivery from Mississippi River Basin to the Gulf of Mexico. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2019GB006475 (2020).

Chakraborty, S. & Lohrenz, S. E. Phytoplankton community structure in the river-influenced continental margin of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 521, 31–47 (2015).

Rabalais, N. N. & Turner, R. E. Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia: Past, Present, and Future. Limnol. Oceanogr. Bull. 28, 117–124 (2019).

Bargu, S. et al. Mississippi River diversions and phytoplankton dynamics in deltaic Gulf of Mexico estuaries: A review. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 221, 39–52 (2019).

Rabotyagov, S. S. et al. Cost-effective targeting of conservation investments to reduce the northern Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 18530–18535 (2014).

Sinha, E., Michalak, A. M. & Balaji, V. Eutrophication will increase during the 21st century as a result of precipitation changes. Science 357, 1–5 (2017).

Basu, N. B. et al. Managing nitrogen legacies to accelerate water quality improvement. Nat. Geosci. 15, 97–105 (2022).

Van Meter, K. J., Basu, N. B., Veenstra, J. J. & Burras, C. L. The nitrogen legacy: Emerging evidence of nitrogen accumulation in anthropogenic landscapes. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 035014 (2016).

Van Meter, K. J., Van Cappellen, P. & Basu, N. B. Legacy nitrogen may prevent achievement of water quality goals in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 360, 427–430 (2018).

Van Meter, K. J., Basu, N. B. & Van Cappellen, P. Two centuries of nitrogen dynamics: Legacy sources and sinks in the Mississippi and Susquehanna River Basins. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 2–23 (2017).

Van Meter, K. J., Schultz, V. O. & Chang, S. Y. Data-driven approaches demonstrate legacy N accumulation in Upper Mississippi River Basin groundwater. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094016 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Impact of groundwater nitrogen legacy on water quality. Nat. Sustain. 7, 891–900 (2024).

Johnson, H. M. & Stets, E. G. Nitrate in Streams During Winter Low-Flow Conditions as an Indicator of Legacy Nitrate. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026996 (2020).

Goolsby, D. A., Battaglin, W. A., Aulenbach, B. T. & Hooper, R. P. Nitrogen flux and sources in the Mississippi River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 248, 75–86 (2000).

Booth, M. S. & Campbell, C. Spring nitrate flux in the Mississippi River Basin: A landscape model with conservation applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 5410–5418 (2007).

Wang, X. T. et al. Influence of open ocean nitrogen supply on the skeletal δ15N of modern shallow-water scleractinian corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 441, 125–132 (2016).

Sims, Z. C., Cohen, A. L., Luu, V. H., Wang, X. T. & Sigman, D. M. Uptake of groundwater nitrogen by a near-shore coral reef community on Bermuda. Coral Reefs 39, 215–228 (2020).

Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M. & Wankel, S. D. Tracing Anthropogenic Inputs of Nitrogen to Ecosystems. In Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science, 2nd ed., 375–449, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470691854.ch12 (2007).

Wang, X. T. et al. Natural forcing of the North Atlantic nitrogen cycle in the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 10606–10611 (2018).

Granger, J., Sigman, D. M., Lehmann, M. F. & Tortell, P. D. Nitrogen and oxygen isotope fractionation during dissimilatory nitrate reduction by denitrifying bacteria. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 2533–2545 (2008).

Zhang, Y., Shi, P., Song, J. & Li, Q. Application of nitrogen and oxygen isotopes for source and fate identification of nitrate pollution in surfacewater: A review. Appl. Sci. 9, 18 (2018).

BryantMason, A., Xu, Y. J. & Altabet, M. Isotopic signature of nitrate in river waters of the lower Mississippi and its distributary, the Atchafalaya. Hydrol. Process. 27, 2840–2850 (2013).

BryantMason, A., Xu, Y. J. & Altabet, M. A. Limited capacity of river corridor wetlands to remove nitrate: A case study on the Atchafalaya River Basin during the 2011 Mississippi River Flooding. Water Resour. Res. 49, 283–290 (2013).

Weigand, M. A., Foriel, J., Barnett, B., Oleynik, S. & Sigman, D. M. Updates to instrumentation and protocols for isotopic analysis of nitrate by the denitrifier method. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 1365–1383 (2016).

Zhi, W. et al. Distinct source water chemistry shapes contrasting concentration‐discharge patterns. Water Resour. Res. 55, 4233–4251 (2019).

Cooper, M. Concentration–discharge relationships reflect chemostatic characteristics of US catchments. Hydrol. Process. An Int. J. 23, 1844–1864 (2009).

Zimmer, M. A., Pellerin, B., Burns, D. A. & Petrochenkov, G. Temporal variability in nitrate-discharge relationships in large rivers as revealed by high-frequency data. Water Resour. Res. 55, 973–989 (2019).

Crawford, J. T., Stets, E. G. & Sprague, L. A. Network Controls on Mean and Variance of Nitrate Loads from the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. J. Environ. Qual. 48, 1789–1799 (2019).

Torres, M., Joshua West, A. & Clark, K. E. Geomorphic regime modulates hydrologic control of chemical weathering in the Andes-Amazon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 166, 105–128 (2015).

Marinos, R. E., Van Meter, K. J. & Basu, N. B. Is the River a Chemostat?: Scale Versus Land Use Controls on Nitrate Concentration-Discharge Dynamics in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–11 (2020).

Hunsaker, C. T. & Johnson, D. W. Concentration-discharge relationships in headwater streams of the Sierra Nevada, California. Water Resour. Res. 53, 7869–7884 (2017).

Moatar, F., Abbott, B. W., Minaudo, C., Curie, F. & Pinay, G. Elemental properties, hydrology, and biology interact to shape concentration-discharge curves for carbon, nutrients, sediment, and major ions. Water Resour. Res. Resour. Res. 53, 1270–1287 (2017).

Turner, R. E. Water quality at the end of the Mississippi River for 120 years: the agricultural imperative. Hydrobiologia 851, 1219–1239 (2024).

Damashek, J. & Francis, C. A. Microbial nitrogen cycling in estuaries: from genes to ecosystem processes. Estuaries and Coasts 41, 626–660 (2018).

Kuypers, M. M. M., Marchant, H. K. & Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 263–276 (2018).

Sanz-Luque, E., Chamizo-Ampudia, A., Llamas, A., Galvan, A. & Fernandez, E. Understanding nitrate assimilation and its regulation in microalgae. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 899 (2015).

Chen, J.-J. et al. Denitrification, anammox, and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium across a mosaic of estuarine benthic habitats. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11681 (2020).

Sigman, D. M. et al. Coupled nitrogen and oxygen isotope measurements of nitrate along the eastern North Pacific margin. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19, 1–14 (2005).

McIsaac, G. F., David, M. B., Gertner, G. Z. & Goolsby, D. A. Nitrate flux in the Mississippi River. Nature 414, 166–167 (2001).

Sigman, D. M. et al. The dual isotopes of deep nitrate as a constraint on the cycle and budget of oceanic fixed nitrogen. Deep. Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 56, 1419–1439 (2009).

Panno, S. V., Hackley, K. C., Kelly, W. R. & Hwang, H.-H. Isotopic Evidence of Nitrate Sources and Denitrification in the Mississippi River, Illinois. J. Environ. Qual. 35, 495–504 (2006).

Chang, C. C. Y., Kendall, C., Silva, S. R., Battaglin, W. A. & Campbell, D. H. Nitrate stable isotopes: Tools for determining nitrate sources among different land uses in the Mississippi River Basin. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 59, 1874–1885 (2002).

Santos, I. R. et al. Submarine groundwater discharge impacts on coastal nutrient biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 307–323 (2021).

Granger, J. & Wankel, S. D. Isotopic overprinting of nitrification on denitrification as a ubiquitous and unifying feature of environmental nitrogen cycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, E6391–E6400 (2016).

Rollinson, V. R. et al. Seasonality of nitrogen sources, cycling, and loading in a New England river discerned from nitrate isotope ratios. Biogeosciences 18, 3421–3444 (2021).

Boshers, D. S., Granger, J., Tobias, C. R., Böhlke, J. K. & Smith, R. L. Constraining the Oxygen Isotopic Composition of Nitrate Produced by Nitrification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1206–1216 (2019).

Redalje, D. G. et al. Nutrients in the Gulf of Mexico: Distributions, cycles, sources, sinks and processes. Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota (Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2019).

David, M. B., Drinkwater, L. E. & McIsaac, G. F. Sources of nitrate yields in the Mississippi River Basin. J. Environ. Qual. 39, 1657–1667 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Heavy Precipitation Impacts on Nitrogen Loading to the Gulf of Mexico in the 21st Century: Model Projections Under Future Climate Scenarios. Earth’s Futur. 10, 1–17 (2022).

Lu, C. et al. Increased extreme precipitation challenges nitrogen load management to the Gulf of Mexico. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, (2020).

Blesh, J. & Drinkwater, L. E. The impact of nitrogen source and crop rotation on nitrogen mass balances in the Mississippi River Basin. Ecol. Appl. 23, 1017–1035 (2013).

Sebilo, M., Mayer, B., Nicolardot, B., Pinay, G. & Mariotti, A. Long-term fate of nitrate fertilizer in agricultural soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 18185–18189 (2013).

Zhang, X., Xu, K., Yang, Z., Tan, X. & Wu, C. Decreasing land growth and unique seasonal area fluctuations of two newborn Mississippi subdeltas. Geomorphology 378, 107617 (2021).

Shaw, J. B., Mohrig, D. & Whitman, S. K. The morphology and evolution of channels on the Wax Lake Delta, Louisiana, USA. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 118, 1562–1584 (2013).

Reiman, J. H. & Xu, Y. J. Dissolved carbon export and CO2 outgassing from the lower Mississippi River – Implications of future river carbon fluxes. J. Hydrol. 578, 124093 (2019).

Cai, Y., Guo, L., Wang, X. & Aiken, G. Abundance, stable isotopic composition, and export fluxes of DOC, POC, and DIC from the Lower Mississippi River during 2006-2008. J. Geophys. Res. G Biogeosciences 120, 2273–2288 (2015).

Christensen, A. L. et al. Delta-X: Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler Channel Surveys. Oak Ridge https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/2081 (2022).

Nghiem, J., Salter, G. & Lamb, M. P. Delta-X: Bed and Suspended Sediment Grain Size. Oak Ridge https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/2135 (2023).

Braman, R. S. & Hendrix, S. A. Nanogram nitrite and nitrate determination in environmental and biological materials by vanadium (III) reduction with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chem. 61, 2715–2718 (1989).

Sigman, D. M. et al. A Bacterial Method for the Nitrogen Isotopic Analysis of Nitrate in Seawater and Freshwater. Anal. Chem. 73, 4145–4153 (2001).

Casciotti, K. L., Sigman, D. M., Hastings, M. G., Bo, J. K. & Hilkert, A. Measurement of the Oxygen Isotopic Composition of Nitrate in Seawater and Freshwater Using the Denitrifier Method. Anal. Chem. 74, 4905–4912 (2002).

Matiatos, I. et al. Global patterns of nitrate isotope composition in rivers and adjacent aquifers reveal reactive nitrogen cascading. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1–10 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Engineer Research and Development Center of US Army Corps of Engineers. Sample splits were kindly provided by the NASA Delta-X project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.T.W. and G.K.L designed the study. G.K.L, J.A.N. and M.P.L. collected the samples used in the study. J.J.C., M.L., T.K. and H.D. analyzed the nitrate isotopes in the Stable Isotope Biogeochemistry Lab at Boston College. G.K.L. and Z.Y. analyzed the particulate nitrogen content isotopes at University of California, Santa Barbara. J.J.C. and X.T.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and provided input to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Annie Bourbonnais and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, JJ., Li, G.K., Lin, M. et al. Isotopic evidence for preferential transport of fertilizer nitrogen into the northern Gulf of Mexico during high water discharge. Commun Earth Environ 5, 745 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01873-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01873-y