Abstract

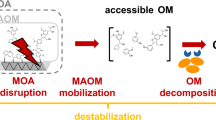

Organic compounds exuded by plant roots can form organo-mineral associations through physico-chemical interactions with soil minerals but can disrupt existing organo-mineral associations by increasing their microbial decomposition and dissolution. The controls on these opposing processes are poorly understood, as are the chemical and spatial characteristics of these associations which may explain gain or loss of organic matter at the root-soil interface termed the rhizosphere. By pulse-labeling with 13C-carbon dioxide, we found that maize root exudates increased organic matter in the rhizosphere clay size fraction and decreased organic matter in the silt size fraction, and that organic matter loss was mitigated by dry conditions. Organic matter associated with rhizosphere clay particles was linked to microbial metabolism of exudates and was more spatially and chemically heterogeneous than non-rhizosphere clay particles. Our findings show that root exudates can simultaneously form and disrupt organo-mineral associations, mediated by mineral size and composition, and soil moisture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil organic matter (SOM), sustained by above- and below-ground plant inputs, contains more organic carbon (C) than the atmosphere and terrestrial plants combined, making soils a critical pool in the global C cycle1. Efforts to sequester SOC to improve soil health and mitigate climate change increasingly focus on enhancing and retaining below-ground plant inputs through practices such as cover cropping, cultivation of perennial and deep-rooted crops, and improved forest management2,3,4,5. The emphasis on below-ground inputs stems from the large proportion, 21–33%, of photosynthate C allocated belowground6, and because below-ground inputs have been shown to contribute more to SOC than above-ground inputs7,8,9,10. These findings are consistent with generally higher SOC concentrations observed in the rhizosphere, the root–soil interface, compared to non-rhizosphere soil11, and, more generally, with high SOC in grassland-dominated ecosystems where a greater proportion of plant C is allocated belowground compared to croplands and forests6,12,13.

Root exudates, small organic molecules exuded by roots, are considered especially important below-ground precursors for SOM formation14. Exudates can be quickly mineralized and emitted as CO2 because they are mostly water soluble and may be rapidly consumed by microbes15. However, exudates, and microbial byproducts and necromass synthesized from exudates, can subsequently associate with minerals, forming persistent organo-mineral associations (OMAs)14,16,17,18,19. The importance of water availability on microbial activity20 suggests that OMA formation, but also disruption, may be enhanced when water is not limited. A recent study has shown that microbial uptake of exudates was correlated with the formation of OMAs in the silt and clay size fraction (<53 µm), often referred to as mineral-associated organic matter21. But exudation also has the potential to disrupt existing OMAs through several mechanisms22 which can lead to a net loss of C and N. Root-driven loss of C is often tied to rhizosphere priming, where an input of exudate-C drives greater decomposition of native SOC than in an absence of exudates. This process is often associated with nitrogen (N) solubilization23,24 and is thought to be a strategy used by plants to increase N availability25. Disruption of OMAs can also occur through abiotic mechanisms including (1) exudate-induced localized pH shifts which can affect sorption/desorption processes26,27, (2) dissolution of redox-sensitive iron (Fe) phases, and the OM that is bound to them, driven by ligands and reductants that are present in exudates28,29,30, and (3) due to increased respiration11, which depletes O2 in the rhizosphere. Furthermore, plants may alter their exudation rate and composition in response to changing root zone conditions such as nutrient31 or water availability32,33, which can directly affect the OMA formation and disruption mechanisms described above34. Lastly, mineral composition has also been shown to impact the formation and disruption of OMAs in the rhizosphere, with some minerals more likely to form OMAs with exudates, and others tend to release existing OMAs in the presence of exudates28,35,36. However, the relative importance of the proposed OMA cycling mechanisms in the rhizosphere under varying soil and plant conditions is not clear.

Much of our knowledge on the dynamics of exudate-derived OMAs is based on model compounds23,28,29,37 that do not represent the chemical complexity and biological variability of exudates38,39. This limits our ability to predict how changes in plant cover and composition impact SOM dynamics. In addition, the chemical composition and spatial arrangement of OMAs is highly complex at the submicron scale40, but how these properties vary between rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere OMAs is unknown. Identification of rhizosphere OMA properties and formation and disruption pathways is essential for understanding ecosystem SOM cycling, since the rhizosphere constitutes a major biogeochemical hotspot11. Our main objective was to uncover the mechanisms of exudate-driven OMA formation and disruption in the rhizosphere under dry and moist soil moisture conditions. We hypothesized that (i) rhizosphere OMA formation and disruption is tightly linked with microbial consumption and association with mineral surfaces, and therefore are enhanced when water is not limited and mediated by particle surface area and mineral composition, (ii) continuous input and microbial transformation of exudate C promotes functional group heterogeneity in rhizosphere OMAs, and (iii) varying rhizosphere redox state drives Fe cycling which leads to the disruption of Fe–C OMAs. To investigate these processes at the spatial scales at which they occur, we pulse-labeled maize plants grown under dry and moist soil moisture conditions with 13CO2 to enrich their root exudates with 13C (Fig. 1). We then conducted isotopic analysis of soil particles size fractions and paired them with whole-sample and spatially resolved spectromicroscopy analyses of OMAs. Our study shows that exudates rapidly (within 24 h) formed new rhizosphere OMAs with clay-sized particles, containing chemically and spatially heterogeneous C functional groups, and simultaneously disrupted existing OMAs on silt-sized particles.

Results

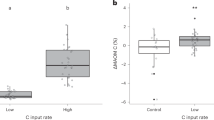

Root exudates stimulate net gain of C and N in the clay fraction and net loss in the silt fraction

We calculated the difference in root-derived 13C, 12C, total C, and total N contents in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil to understand how root activity impacted C and N cycling in the rhizosphere (Fig. 2). Root-derived 13C content was greater in the rhizosphere than non-rhizosphere (Fig. 2a) (p < 0.0001 for all size fractions) and was not affected by moisture treatment (Supplementary Table 3). The 13C content in the rhizosphere clay fraction (1812 and 2180 µg 13C g−1 in moist and dry treatment, respectively) was significantly greater than in the silt fraction (79 and 86 µg 13C g−1 in moist and dry treatment, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2), indicating that exudate-C was preferentially stored in the clay fraction. The difference in 13C content between rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere in the whole soil was greater than in the clay and silt fractions (Fig. 2a), likely because the whole soil also contained 13C which originated from fine root fragments in the >53 µm size fraction (which we did not collect). The amount of 12C in the clay fraction was greater in the rhizosphere than non-rhizosphere by 0.44 g C kg−1 soil, regardless of moisture treatment (p = 0.037), likely originating from exudate-derived C entering the rhizosphere prior to plant labeling (Fig. 2b). In comparison, the amount of 12C in the silt fraction was smaller in the rhizosphere than non-rhizosphere by 4.47 g kg−1 soil in the moist treatment (p = 0.002) and 1.99 g kg−1 soil in the dry treatment (p = 0.12). Overall, the combined silt+clay fraction in the rhizosphere contained 2.79 g kg−1 less 12C than the non-rhizosphere soil (p = 0.013), regardless of moisture. We found a net gain in total C regardless of soil moisture (0.77 g C kg−1 soil, p = 0.0008) in the rhizosphere clay fraction and a net loss in the silt fraction, but statistically different only in the moist treatment (4.42 g C kg−1 soil, p = 0.002 in moist; 1.94 g C kg−1 soil, p = 0.13 in dry) (Fig. 2c). But, despite the rhizosphere silt + clay fractions containing less total C than non-rhizosphere silt + clay fractions, the whole soil in the rhizosphere contained more total C in was than the non-rhizosphere soil (5.68 g C kg−1 soil, p = 0.008) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 3). This was likely a contribution of particulate C from fine roots. Similarly to total C, rhizosphere total N increased in the clay fraction by 0.11 g N kg−1 soil (p = 0.0014) regardless of moisture but decreased in the silt fraction by 0.36 g N kg−1 soil under the moist treatment (p = 0.004). Unlike total C, whole soil N content was not different between the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil (Supplementary Table 3).

Difference between rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil in a content of root-derived 13C content, b 12C, c total C, and d total N. Data are presented for the clay, silt, and combined silt + clay size fractions, and whole (non-fractionated) soils in maize microcosms grown under dry or moist moisture treatments. Box plots represent n = 6 independent biological replicates. Boxplot center line represents median, box limits the first and third quartiles, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values no further than 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR). Symbols above the boxplot indicate statistical significance between the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere for each size fraction and moisture treatment combination (ns = p ≥ 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Statistical significance was tested using two-sided comparisons of estimated marginal means. A horizontal line beneath the symbols indicates no interactions with the moisture treatment.

Changes in rhizosphere C and N concentrations are associated with SOM compositional changes in each size fraction

To understand the SOM gain vs. loss in the clay and silt size fractions, respectively, we characterized their mineral and chemical composition using surface area analysis, X-ray diffraction, and bulk (i.e., not spatially resolved) C K-edge and Fe L-edge near edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS). The clay size fraction was primarily comprised of primary and secondary minerals such as illite, chlorite, kaolinite, and K-feldspar, and had a specific surface area of 19.1 m2 g−1 according to N2 sorption (Supplementary Tables 1, 4). In comparison, the silt size fraction was primarily comprised of quartz (79%, compared to 35% in the clay size fraction) and had a specific surface area of 3.5 m2 g−1. The composition of clay minerals within the silt and clay size fractions was similar (Supplementary Table 5).

We found different C functional group compositions across size fractions of the rhizosphere (Fig. 3). Specifically, the relative abundances of quinone (284.3 eV), aromatic (285.1 eV), and phenolic C (286.6 eV) were lower in the clay than the silt fraction (whole soil is an intermediate), while the relative abundance of carboxylic C (288.7 eV) was highest in the clay fraction (Supplementary Table 6). This resulted in higher carboxylic/quinone, carboxylic/aromatic, and carboxylic/phenolic ratios in the rhizosphere clay fraction than in the silt fraction, suggesting that changes in rhizosphere C and N concentrations in the two size fractions (Fig. 2c, d) were accompanied by SOM compositional changes. However, in the non-rhizosphere soil, the composition of C functional groups was more similar across size fractions (Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, the composition of C functional groups in the rhizosphere varied more across size fractions than across moisture treatment, suggesting that size fraction was a more dominant driver of C composition than soil water content. Differences in Fe oxidation state between the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soils, as reflected in the Fe L3 edge split ratio, were not detectable in Fe L-edge NEXAFS measurements (Supplementary Fig. 7).

C K-edge NEXAFS spectra of the whole soil, silt fraction, and clay fraction collected from a rhizosphere and b non-rhizosphere soil in microcosms grown with maize under dry and moist moisture treatments. Graphs show normalized modeled spectra following deconvolution of raw spectra. Spectral features identified by the vertical dashed lines correspond to C in a quinonic (284.3 eV), b aromatic (285.2 eV), c phenolic (286.4 eV), d aliphatic (287.3 eV), e carboxylic (288.5 eV), and f O-alkyl (289.5 eV) functional groups.

OMAs facilitated by calcium drive C accrual in the rhizosphere

Analysis of scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM)–NEXAFS images of clay-sized particles revealed greater co-localization of C with calcium (Ca) in the rhizosphere compared to non-rhizosphere soil, as shown qualitatively in RGB maps (Fig. 4a, b) and in semi-quantitative correlation plots (Fig. 4c, d) of moist and dry soils. In addition, the C–Ca co-localization was higher under moist than dry conditions. The spectral NEXAFS features of the Ca in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere samples suggested that it was bound to organic compounds and clay minerals, as we previously reported for this soil41 (Supplementary Fig. 10, see further information in the SI section). In the rhizosphere, we identified regions with C–Ca, C–Fe, and C–Ca–Fe co-localization, as well as Fe-rich regions that were not co-localized with C. For example, evenly colored green–yellow regions indicate homogeneous particle coating with C (co-localized with Ca) in the rhizosphere (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the distribution of C in the non-rhizosphere soil samples was patchier and co-localization of C with mineral elements was less apparent (Fig. 4b). Overall, spatial correlations of C with Fe, Al, and Si were lower than with Ca, but consistently higher in the rhizosphere than the non-rhizosphere soil (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b), a result confirmed by spatial correlation analysis of nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) images from the rhizosphere (Supplementary Fig. 8c).

Color-coded composite RGB optical density maps for a rhizosphere and b non-rhizosphere soils. See color triangle for color coding. Elemental spatial correlation plots between carbon and calcium for two c rhizosphere and d non-rhizosphere samples. Pearson correlation coefficients and lines are shown for elemental correlation. White bars: 5 µm.

NanoSIMS analysis also provided further evidence for the key role of Ca in the formation of OMAs from exudate-derived 13C (Fig. 5). We identified two hotspots in the rhizosphere samples with high 13C enrichment (4.84 and 8.14 atom%) and an additional hotspot with lower 13C enrichment (1.67 atom%), while the mean 13C of the three samples was 1.3, 1.2, 1.13 atom%, respectively (Fig. 5a). The ovoid-shaped 13C hotspots were characterized by relatively low C:N values (which are quantified by NanoSIMS as high N:C) (Fig. 5b) and were co-localized with Ca (Fig. 5c), elements that make up clay minerals (K, Mg, and Al) (Fig. 5c, d), and with P (Fig. 5e).

Spatial distribution of a 13C enrichment on mineral surfaces, b N:C on mineral surfaces, c Fe, Ca, and Al, d Na, Mg, K, and e P. Red boundary outlines the hotspots with 13C enrichment in each sample. Values next to red outlines indicate mean 13C enrichment (atom%) in each hotspot. White bars: 10 µm.

Oxidized forms of Fe and C are co-localized in the rhizosphere

Based on principal component and cluster analysis, we found five distinctly discernible C NEXAFS spectral features in the rhizosphere, revealing patterns in fine-scale distribution of C and Fe chemical composition (Fig. 6a–c). Overall, we detected spatial gradients in C–Fe associations ranging from strong spatial associations between oxidized Fe and C forms (e.g., C and Fe region 1) to weaker spatial associations between reduced Fe and C forms (e.g., C region 5 and Fe region 4). The C K-edge NEXAFS region 1 showed a prominent peak at 288.5 eV attributed to carboxylic C, while the spectra representing regions 2–5 showed increasingly greater absorbance at 285.1 eV (aromatic C structure), 286.2 eV (phenolic C), 287.3 eV (aliphatic C), 288.2 eV (amides), and 289.3 eV (O-alkyl C) (Fig. 6a–c). Region 5 had the highest contribution of reduced C groups (quinone C, 284.5 eV; aromatic C, 285.1 eV; phenolic C, 286.2 eV, and aliphatic C, 287.3 eV) (Fig. 6a–c). We also found five distinct spectral Fe L-edge NEXAFS features representing varied and spatially distributed Fe valence states in the rhizosphere (Fig. 6d–f). Fe L3 edge signals at 709.5 and 707.8 eV reflect Fe speciation, with the relative absorbance intensity indicating the proportion of Fe(III) vs. Fe(II) valence states, respectively. Regions 1–3 had spectra with the dominant peak at 709.5 eV, indicating mostly Fe(III) phases, while the spectra of regions 4 and 5 had equal absorbance at 709.5/707.8 eV or a dominant 707.8 eV peak, indicating mineral phases composed of mixed-valence Fe(II/III) or mostly Fe(II). Upon closer inspection, we also found evidence of chemical co-variation between C and Fe. Fe regions 1–3 (Fe(III)) were spatially associated with C regions 1–3, which were characterized by absorbance at the carboxylic-C and aromatic-C regions (285.1 and 288.5 eV). Fe region 4 (Fe(II/III)) was associated with C region 5, which had a greater abundance of reduced C groups. The particles within Fe region 5, composed of Fe(II) phases, were C-poor, based on the C elemental map (Fig. 6a). These results suggest that Fe(II) and Fe(II/III) tended to interact with reduced C forms or lack C altogether. In comparison, in the non-rhizosphere soil we found only two regions of distinct C NEXAFS spectra (Fig. 6g–i). The spectrum representing C region 1 had prominent peaks at 285.1 and 288.5 eV (carboxylic and aromatic C), while the spectrum representing C region 2 had a prominent peak at 288.5 eV. In both C regions the peaks assigned to phenolic, aliphatic, amide, and O-alkyl C were less pronounced than in the rhizosphere (Fig. 6c, i). Likewise, only three Fe regions were found, which were represented by spectra indicating a similar Fe(III) dominant composition (Fig. 6j–l) as reflected by a small range of Fe L3 peak area ratios (Supplementary Fig. 9). The spectral features of Al and Si K-edge NEXAFS were similar in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere samples and suggested a mineral composition consistent with the X-ray diffraction results (further details in the SI section).

Elemental maps of C (a, g), and Fe (d, j), cluster maps of C (b, h) and Fe (e, k), and cluster spectra of C (c, i), and Fe (f, l) collected from moist rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere samples. Colors in cluster maps correspond to colors in cluster spectra. For C K-edge, spectral features identified by the vertical dashed lines correspond to C in quinonic (284.3 eV) (a), aromatic (285.2 eV) (b), phenolic (286.4 eV) (c), aliphatic (287.3 eV) (d), carboxylic (288.5 eV) (e), and O-alkyl (289.5 eV) (f) functional groups. For Fe L-edge, spectral features identified by vertical dashed lines correspond to Fe(II) (707.8 eV) (i), and Fe(III) (709.5 eV) (ii). White bars: 5 µm.

Discussion

It is widely assumed that SOM associated with silt and clay size fractions is relatively persistent and has a slower turnover time than particulate SOM (>53 µm)42. Our results demonstrate how root exudation can alter the amount and composition of C and N stored in different soil particle size fractions, and that this process is mediated by both soil moisture and mineral composition. We found that the clay fraction in the rhizosphere preferentially formed OMAs from exudates, indicated by greater C and N content and 13C enrichment (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, C and N decreased in the rhizosphere silt fraction in moist conditions only, resulting in net native C loss in the silt + clay fraction of the rhizosphere (3.75 g kg−1 soil), i.e., exudates caused rhizosphere priming. Since exudate-derived C preferentially adsorbed on the clay size fraction but C was lost from the silt size fraction, a plausible mechanism for this loss may have involved exudate-driven desorption or dissolution of minerals and mobilization of C and N, priming microbial decomposition of C in the silt size fraction, which may have included small particulate C in addition to C in OMAs. Our findings of diverse Fe valence states in the rhizosphere clay fraction, and absence of C in Fe(II) regions indicating possible C mobilization from those surfaces, are consistent with this hypothesis. It is also possible that microbes mineralized native C and N in the clay size fraction. However, net C change in the clay fraction was positive, indicating that exudate C gain was greater than potential native C loss.

The abundant primary and secondary clay minerals with greater specific surface area in the clay size fraction likely have more capacity to retain and protect C inputs than the quartz minerals that dominated the silt fraction (Supplementary Table 4)43,44,45,46. In addition, C decomposition by microbes and extracellular enzymes tends to occur more in pores 30–150 µm in size47,48, which are more likely to be found between silt size particles than clay size particles49. These size-related processes can explain the differences in net C and N change in the two size fractions. Our findings expand on a recent study which showed that root exudation can cause C loss in sand mixed with low-reactivity clays but C gain in sand mixed with high-reactivity clays35 by showing that gain and loss can occur simultaneously in soil, emphasizing the important role of mineral composition and soil moisture in controlling the direction and magnitude of rhizosphere net SOM change. However, despite net C loss in the silt + clay fraction in the rhizosphere, we found that whole soil C in the rhizosphere was higher than non-rhizosphere soil (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3), indicating that, in our experiment, plant roots caused a net increase in C. Given the low C content of minerals in size fractions >53 µm50, this net C gain was likely derived from particulate root debris, though this was not directly measured. This may suggest that under certain conditions root activity can potentially increase the relative proportion of particulate SOM in the short term, though a portion of this root debris may persist as particulate SOM51.

Our results show that rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere OMAs differed in their chemical composition, spatial distribution, and functional group heterogeneity. While the composition and diversity of soluble organic molecules in the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil may be different52, there is very little information on the differences in the chemical distribution and composition of OMAs from rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil. Evidence gathered from whole-sample and spatially resolved elemental, isotopic, and spectromicroscopic subsamples indicates these differences resulted from continuous organic inputs in the form of root exudates in combination with their microbial transformation. First, the clay size fraction in the rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere had equally low C:N values, indicative of microbial decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3). Second, the rhizosphere clay fraction had lower δ15N values than the non-rhizosphere clay fraction (Supplementary Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 2), which suggests that it contained more plant root exudates which are typically depleted in 15N53,54. This is consistent with the accumulation of carboxylic groups on the clay rhizosphere particles (Fig. 3a). Carboxylic acids, such as malic, oxalic, and succinic acids, can constitute a substantial proportion of root exudates (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 6)55. Accumulation of carboxylic groups can also suggest a microbial nature to OMAs in the clay fraction, as microbial transformation tends to enrich compounds with carboxylic-C groups56. In contrast to the rhizosphere, there were fewer differences in C functional group composition across non-rhizosphere soil size fractions (Fig. 3b).

We also found that compositional differences between non-rhizosphere and rhizosphere OMAs were reflected in their spatial distribution (Fig. 4) and functional group heterogeneity (Fig. 6). Non-rhizosphere soil C composition was characterized by two similar spectral types consisting of aromatic, phenolic, and carboxylic C functional groups, pointing to the presence of plant- and microbial-derived phenolic, aromatic and other carboxylic acids, and degradation products of plant-derived lignin which are rich in phenolic groups57 (Fig. 6i). In comparison, rhizosphere C functional group composition was more diverse, consisting of five spectral types, distributed across regions of OMAs that contained different proportions of aromatic, phenolic, aliphatic, amide, carboxyl, and O-alkyl groups (Fig. 6c). These additional functionalities may reflect greater chemical diversity introduced by root exudates, their microbial transformation products, and microbial biomass. For example, the amide peak at 288.2 eV (C 1 s-π*C=O or C 1 s-π*C–N) indicates the presence of peptide bonds arising from proteins58,59, typically attributed to microbial cells, while aliphatic C (287.3 eV) is often attributed to phospholipid fatty acids from microbial or root cell walls40,60. Some rhizosphere OMAs contained O-alkyl groups (289.2 and 289.7 eV), likely from polysaccharides40, a significant part of maize root exudates61 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Exuded polysaccharide compounds have been shown to undergo rapid and irreversible adsorption to soil minerals through van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding62. Similar polysaccharide C-rich spectra are reported for fungal cells isolated from soil63 and microbial extracellular polymeric substances64, suggesting that microbial colonization is an additional potential source of polysaccharide in OMAs in the rhizosphere. The role of microbes in rhizosphere OMA formation is also supported by the NanoSIMS images of rhizosphere samples (Fig. 5). We identified several ovoid-shaped 13C-enriched features which were strongly co-localized with N and P. These features may be interpreted as microbial cells or cell envelopes of non-living bacteria65.

Taken together, root exudation and microbial uptake and transformation of exudates increased the chemical heterogeneity of rhizosphere OMAs (Fig. 6c). Conversely, the absence of new C inputs in the non-rhizosphere soil17, which is an important driver of compositional changes and cycling between C and N pools66,67,68, may have resulted in less chemically diverse non-rhizosphere OMAs (Fig. 6i).

Rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil OMAs differed in the co-localization of organic compounds and mineral surfaces, which may indicate different OMA formation mechanisms. We found that C was most highly co-localized with Ca, and that this correlation was higher in the rhizosphere than non-rhizosphere soil (Fig. 4). C–Ca correlation was also higher under moist than dry treatment, suggesting that water availability may have increased OMA formation at the submicron scale. This may be explained, among others, by the effects of water availability on microbial activity which drives OMA formation (Figs. 5 and 6), and its effects on exudate amount and composition32, which may affect their interactions with mineral elements. However, the data collected here does not allow us to test these relationships. Regardless, the greater C–Ca spatial correlation under moist treatment did not correspond to the greater amount of SOM on the clay fraction (Fig. 2). Co-localization of C with Ca is consistent with our previous findings on these soils which showed high correlation between C and extractable Ca contents, but does not agree with the high correlations we previously found between C and extractable Al contents50,69, perhaps because only a small proportion of surface areas containing Al interact with C. A recent study also showed greater organo-mineral spatial correlation (albeit with Fe not Ca) in rhizosphere compared to non-rhizosphere soils which was linked to root-induced mineral weathering over pedogenic scales70. The short-term effects found in this study suggest that other processes drove differences between non-rhizosphere and rhizosphere. For example, higher C–Ca associations may have resulted from strong interactions known to occur between Ca and carboxylate groups in exudates71,72,73. In addition, we have recently shown that Ca may increase deposition and stabilization of microbial exudates and transformation products on mineral surfaces41, which is consistent with the co-localization of microbial cells, lipids, and proteins in Ca-rich regions of the rhizosphere (Figs. 5 and 6). These findings indicate that, in some soils, interactions with Ca-clays could be a more dominant OMA formation mechanism than direct sorption to oxides74. In contrast to the rhizosphere, lower organic inputs in the non-rhizosphere soil, and therefore greater turnover of existing organics, may have reduced their spatial associations with minerals, resulting in patchier distribution (Fig. 4). Soil pH may also be a strong driver of OMAs since higher pH can deprotonate organic compounds and mineral surface functional groups, thus increasing their negative charge and promoting Ca-organic electric interactions75. However, non-rhizosphere soil had higher pH (Supplementary Fig. 5) and lesser Ca–C co-localization, indicating that differences in pH did not play a key role.

We did not find strong spatial correlation between C and Fe (Supplementary Fig. 8), which is expected given the low correlation between C and extractable Fe contents which we found in a previous study50. However, the different Fe speciation in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere and corresponding C composition suggests that Fe had a role in rhizosphere C turnover. In the non-rhizosphere soil, Fe-bearing aluminosilicates predominantly contained oxidized Fe(III) species, as found in several other studies on highland soils40,57,58, while the rhizosphere contained a combination of oxidized Fe(III), reduced Fe(II), and mixed-valence Fe(II/III) species, as reported for soils that experience reducing conditions such wetland and permafrost soils57,76. Furthermore, we found that regions with reduced or mixed-valence Fe did not contain C or contained relatively hydrophobic C (i.e., aromatic and aliphatic functional groups). The co-occurrence of reduced C or lack of C with Fe(II) and oxidized C with Fe(II) has been recently reported in several studies of the spatial distribution of C–Fe associations60,77. Root exudates may underlie several mechanisms involved in changes to rhizosphere Fe speciation, including heightened autotrophic and heterotrophic respiration leading to reduced localized redox potential, exudation of ligands and reductants that can dissolve Fe from oxide phases and aluminosilicates28,29,75,78,79,80, and increased secretion of Fe-reducing chelators by some fungi, as part of a mechanism to degrade lignocellulose81. These results provide clear evidence at the submicron scale of exudation-driven reductive dissolution of Fe in aluminosilicates and oxides which can lead to the release of bound organics into solution. This abiotic mechanism of OMA disruption is emerging as an important and intensively studied aspect of biogeochemical cycling of nutrients and OM in the rhizosphere.

Our study closely examined OMA dynamics in the rhizosphere and demonstrated rapid cycling driven by root exudates. While the magnitude and direction of net change in OMAs is likely variable and dependent upon soil and root properties, our results indicate that OMA formation is fundamentally coupled with OMA disruption, suggesting a limit to OMA accrual reliant on root exudation. OMA dynamics were dependent on mineralogy which differed with particle size, thus an analysis of fractions more detailed than the common 53-µm threshold may improve our understanding of the formation–disruption tradeoff. Furthermore, while most studies on OMA formation–disruption processes focus on Fe and Al oxides, we suggest that the role of Ca in these processes and the potential of Ca-containing amendments to foster OMA formation should be investigated further. Nonetheless, the net gain in total rhizosphere SOC suggested that root inputs are an important component of SOC management. An interesting observation was the greater chemical and spatial heterogeneity in the rhizosphere OMAs. Chemical heterogeneity, or diversity, is emerging as a trait which can increase SOC persistence. Although our findings are based on short-term dynamics, greater chemical diversity inferred by long-term root activity may play a role in plant-based C sequestration. A greater understanding of OMA dynamics in the rhizosphere, and persistence inferred through chemical complexity and enhanced mineral associations, is needed to better leverage exudate-focused strategies for C sequestration.

Methods

Plant labeling with 13 CO2

We constructed microcosms from acrylic tubes (150 mm length, 69 mm o.d.) and polycarbonate caps (Supplementary Fig. 1) and packed them with air-dry soil sieved to <4 mm at a bulk density of 1.1 g cm−3. The soil used was a Madalin series, a fine, illitic, mesic Mollic Endoaqualf (Supplementary Table 1) which was collected from a fallow field located near Ithaca, NY, USA (42N28.20′, 76W25.94′). The top cap of the microcosm was fixed to the tube using high-vacuum grease and heavy-duty duct tape. The holes in the top cap (designed to hold septa to allow gas sampling, not used in this study) were plugged with rubber stoppers. Preliminary tests demonstrated that these measures achieved a gas-tight seal that ensured that 13C–CO2 could enter the soil only via plant roots. Maize plants (Zea mays, L. cultivar ‘B73’) were pre-germinated and transferred to the microcosm. The plants were grown under artificial lighting (BR30, GE Lighting, Savant Technologies LLC., Cleveland, OH, USA) providing 650 lumens at an 18/6 light/dark cycle. During plant growth, the microcosms were wrapped in aluminum foil to prevent light penetrating to the soil and roots. Soil gravimetric water content was kept at 20% by weighing and watering daily. After 11 days of growth, the soil moisture treatment was applied. Half of the microcosms (n = 6) were kept at 10% gravimetric water content (Dry treatment) and half (n = 6) at 23% (Moist treatment). These water contents are equivalent to approximately 30% and 60% of the water holding capacity. Non-planted microcosms were prepared as above.

The plants were labeled with 13CO2 26 days after the soil moisture treatment was initiated. The gap around the stems was sealed using a removable mounting putty (LOCTITE, Henkel, Duesseldorf, Germany) to ensure that 13CO2 did not enter the soil through this gap. Subsequently, microcosms were placed in a gas-tight chamber constructed from acrylic sheets (Supplementary Fig. 1). The chamber air was circulated through a soda lime trap to scrub ambient CO2 (monitored using a LICOR LI-850 H2O/CO2 analyzer), followed by injection of 13CO2 (99 atom%; Sigma Aldrich) via a small port installed in the chamber (target concentration of ~500 ppm). Small fans were installed in the chamber to improve circulation. Plants were kept in the chamber for 24 h to track freshly fixed 13C in plant root soluble C (a proxy for exudate C) and soil particle size fractions (see below). CO2 concentrations slowly increased throughout the labeling phase, indicating possible entry of lab air into the chamber. After 24 h, the chamber air was scrubbed through the soda lime column to remove any remaining 13CO2. The plants were removed from the chamber and gas exchange was measured under ambient light conditions (~200 µmol m−2 s−1) with a CIRAS-2 portable photosynthesis system (PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) at 400 ppm CO2 and a chamber flow rate of 200 ml min−1. Transpiration rates of plants in the dry and moist treatments were 0.65 ± 0.33 and 1.22 ± 0.35 mmol m−2 s−1, respectively.

Soil and plant sampling and analysis

After labeling, microcosms were disassembled, and the root mass was gently shaken until a fine coating of soil was left on the roots. We define this soil as the rhizosphere and the soil that did not adhere to the roots as non-rhizosphere soil. Rhizosphere soil was collected by further gentle shaking of the roots. Fresh non-rhizosphere and rhizosphere soils were passed through a 2 mm sieve; these non-fractionated soils are referred to as whole soils. We then conducted a size fractionation protocol (see below) on the whole soils, isolating the silt (2–53 µm) and clay (<2 µm) particle size fractions, to study root-induced OMA cycling in these minerals. The SOM in these fractions is often collectively referred to as the mineral-associated organic matter42, however, the size fractions within can differ in their mineral composition and surface area, potentially affecting the extent of OMA formation and disruption in these size fractions. The >53 µm size fraction, made up of sand-size particles and particulate organic matter, constituted 24.10% ± 1.23% of the soil by mass. This fraction was discarded and not analyzed because the minerals in the >53 µm fraction contain insignificant amounts of C, and because our objectives did not focus on particulate organic matter50. We also analyzed the whole soil to determine changes to total SOM from root exudates.

The two-step fractionation protocol used was adapted from Amelung et al.82. Briefly, soil samples (1 g dry weight equivalent in 10 mL ultrapure water) were shaken with four glass beads (3 mm) for 2 h at 180 rpm and wet sieved (53 µm). This step minimizes the transfer of C and N from particulate organic matter (consisting of, e.g., root fragments and decomposing plant matter) to the silt and clay size fractions which may occur during the next step which separates the <53 µm fraction into silt and clay. The <53 µm suspension (1:25 solid to liquid ratio) was ultrasonicated (Q500, QSonica) at 450 J/mL and centrifuged at 500 rpm for 9 min at 20 °C. The suspension consisting of the clay fraction was decanted and the pellet, consisting of the silt fraction was vortexed, centrifuged, and decanted as above twice more to ensure complete separation. The clay and silt fractions were freeze-dried and finely ground. Based on the two-step fractionation protocol, we assume that 13C recovered from the silt and clay fractions was primarily derived from root exudates and not from root particles, while whole soils may have contained both exudate- and root-matter derived 13C. This assumption is supported by the similarly low C:N values of clay and silt fractions in the rhizosphere compared to non-rhizosphere, and high C:N ratio of whole soil in the rhizosphere compared to non-rhizosphere (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3), since roots typically have higher C:N values than soil (further discussed below). However, it is possible that the silt fraction may also contain small amounts of particulate C and N forms. Furthermore, the suspension containing the clay-sized particles may have contained some dissolved organic C which would have been lyophilized along with the clay particles. The above and belowground plant biomass was separated, and water-soluble C was extracted from roots in hot water83. We used water-soluble root C as the proxy for root exudates in the isotopic calculations (see below). We assume that the 13C enrichment of soluble root C reasonably represents exudate enrichment because most exudates in young plants tend to be soluble sugars84,85, and newly assimilated C is typically the primary C source of exudates, as has been shown for trees and grasses86,87. In a later experiment, maize was grown in identical conditions and root exudates were collected using reported protocols88. Briefly, maize plants were grown in sand and transferred to beakers containing ultrapure water for 8 h. The exudate collecting solution was filter sterilized (0.2 µm) and freeze-dried.

The silt and clay fractions, along with whole soils and root sugar extracts, were analyzed for total C and N contents and δ13C and δ15N using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta V, Thermo Scientific, Germany) coupled to an elemental analyzer (NC2500, Carlo Erba, Italy). The C and N content of the combined silt + clay fractions were calculated (not measured) based on the individually measured C and N content of the silt and clay fractions, and their proportional mass in the soil (Table S1). We did not calculate the δ13C, δ15N, or C:N ratio of the combined silt + clay fractions. Since inorganic C was not present in the soil and inorganic N constitutes ~1% of total N, we interpreted total C and N as organic C and N41. Finally, since non-rhizosphere soil in planted microcosms had similar C and N contents to unplanted soil (Supplementary Fig. 4), we interpret the difference in C and N between rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil as gains and losses due to root activity.

A mixing model was used to quantify the proportion of 13C in whole soils and size fractions, using the formula:

where \({{{\rm{at.}}} \% }_{{{\rm{sample}}}}\) is the atom% 13C value of a labeled sample, \({{{\rm{at.}}} \% }_{{{\rm{non}}}-{labeled}}\) is the atom% 13C value of a non-labeled sample, and \({{{\rm{at.}}} \% }_{{{\rm{label}}}}\) is the atom% 13C of the soluble root C extracted from each plant grown in the corresponding microcosm (9.15 ± 2.07 atom%). \({f}_{{13}_{{C}}}\) was multiplied by the C content in each fraction to calculate the amount of 13C (μg 13C g−1 fraction) and by the mass proportion of each fraction to calculate its relative amount in the soil (μg 13C g−1 soil). Negative \({f}_{{13}_{{C}}}\) values were assumed to be zero. The proportion of 12C, which consists of native SOC and root-C that entered the soil prior to plant labeling, was calculated as the difference between total C and 13C.

Soil pH was measured on 1:5 soil to water extracts. Non-rhizosphere soil pH was 6.07 ± 0.12 and rhizosphere pH was 5.76 ± 0.09 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The specific surface area of the clay and silt fractions was determined by multi-point BET (autosorb iQ, Anton Paar) with N2 at 77 K. Prior to analysis, the samples were outgassed for 24 h using helium at 40 °C. We report the mean values of duplicate measurements.

Mineralogical characterization of total mineral phase and the composition of clay minerals in the clay and silt size fractions was carried out by the Illinois State Geological Survey using established protocols89. Samples for randomly oriented powder X-ray diffraction analysis are ground in an agate dish before installation in the sample tray. Step-scanned data is collected from 5° to 70° 2θ with a fixed rate of 1° min−1 with a step size of 0.02° 2θ. Qualitative mineral phase identification is done based on the location and intensity of peaks of the 2θ scale compared with the PDF2 database using Materials Data Inc. (MDI) known as JADE. Semi-quantitative analysis of the randomly oriented samples is based on the Rietveld refinement. Samples for preferentially oriented X-ray diffraction analysis are deposited on a glass slide which is then air-dried, glycolated, scanned by XRD, heated to 300 °C, and scanned again. Step-scanned data is collected from 2° to 34° 2θ with a fixed rate of 1° min−1 with a step size of 0.02° 2θ. Semi-quantitative analysis of the clay minerals was based on the extent of change in d-spacing following glycol and heat treatments.

C K-edge and Fe L-edge near edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS)

The chemical composition of C and Fe in soil samples and C in root exudates was determined by NEXAFS90 acquired at the C K-edge (270–320 eV) and Fe L-edge (690–750 eV) at the spherical grating monochromator (SGM) beamline of the Canadian Light Source (Saskatoon, SK). For this high-resolution chemical characterization approach, we analyzed composited (n = 3) soils and soil fractions from each treatment and did not separately analyze individual replicates. Samples were prepared by pressing pellets into the SGM Beamline sample holders. No binder was used in the process. Carbon partial fluorescence yield (PFY) spectra were collected using a silicon drift detector (Amptek FastSDD) placed in the plane of polarization at 90° to the incident beam to minimize the contribution of scattering in the measurement. Multiple (between 10 and 30) 60-s-long slew scans were acquired on different spots on the samples and averaged to obtain the raw PFY measurement. To accurately measure the I0 (incident flux) at the C K-edge, a measurement of the boron fluorescence from highly pure boron nitride is used. The normalized C PFY is produced by dividing the raw PFY by this boron PFY. Energy calibration of the C spectra was checked using the C1s (C=O) to π* transition at 288.7 eV of a citric acid standard. For C spectra, the background was corrected by a linear regression fit through the pre-edge region (270–280 eV) followed by normalization to an edge step of unity done by fitting a second-order polynomial through the post-edge (303–320 eV), using ~288.0 eV as E0, respectively. All procedures were done in Athena ver. 0.9.2691. The C composition was assessed by deconvoluting the spectra (280–305 eV) using a Gaussian function fitting algorithm in Fityk ver. 1.3.192. Arctangent functions were used to model the ionization step at 290 eV, with full width at half maximum (FWHM) set at 0.5 eV, and Gaussian peaks (FWHM 0.6 eV, floated amplitude), constituting contributions from C functional groups aromatic-C, substituted aromatic-C, alkyl-C, carboxyl-C, and O-alkyl C90,93. Additionally, two C1s σ* transitions at 290.2 and 291.5 eV were simulated using Gaussian curves. Peak assignments used in deconvolution are shown in Supplementary Table 6.

Energy calibration of the Fe spectra was done using the 709.5 eV peak of an α-Fe2O3 standard. The background of Fe spectra was corrected by fitting a linear regression through the pre-edge region (690–700 eV) in Athena Ver. 0.9.2691 and normalization of the Fe L-edge PFY was done by dividing the raw PFY by the I0. We determined relative fluorescence intensity in higher and lower regions of the L3-edge using an area under the curve (AUC) approach. An edge-step correction for bulk (i.e., not spatially resolved) Fe L-edge NEXAFS spectra was conducted by fitting an arctangent function to the pre- and post-edge regions in Fityk v. 1.3.192. The arctangent center energy position was fixed to 715.0 eV, and the inflection was set to 1, with variable vertical and pre- and post-edge position. For Fe L-edge STXM–NEXAFS cluster spectra, the edge step was negligible, and no edge-step correction was required. Prior to AUC estimation, corrected spectra were further processed using R v4.3.194. Spectra were rescaled (max = 1), and points below the baseline were excluded to avoid bias in AUC estimation. An Fe(III) oxide (Fe2O3) standard measurement was used to calibrate energy position, based on the energy of the peak split in the L3-edge (709 eV). The AUC was estimated for lower (705.0–709.0 eV) and higher (709.0–715.0 eV) regions of the L3-edge using the trapezoid method (100 subdivisions) within the ‘AUC’ function in the DescTools R package95.

Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM)–NEXAFS

Suspensions of clay particles in ultrapure water (1 µg/mL) were deposited on Si3N4 windows and air-dried57,96. STXM–NEXAFS was performed at the Canadian Light Source on the SM beamline. Samples were analyzed at a 1/6 atm of helium and measured using a 25 nm Fresnel zone plate. From each window, images of large areas (1000, 600, and 250 µm2) were taken to select representative regions and to identify them in subsequent NanoSIMS analysis (see below). Preliminary C maps (~50 µm2) were made by subtracting the C K pre-edge from the post-edge (Supplementary Table 7) to identify C-containing regions. Samples were raster scanned at a spatial resolution of 250 nm using a dwell time of 1 ms across an eV range capturing C K-edge, Ca L-edge, Fe L-edge, Al K-edge, and Si K-edge NEXAFS data. We chose to analyze larger images at the expense of reduced spatial resolution to collect data from a more representative subset of particles. Image sequences were aligned and converted to optical density (OD = ln(I0/I)) according to methods previously reported71,97 using the aXis2000 software package98. Elemental maps for C, Ca, Fe, Al, and Si were generated by subtracting the pre-edge image from the post-edge image (Supplementary Table 7). Spatial correlations between elements were determined based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient using the ScatterJ plugin in ImageJ99. Principal component analysis was performed with the PCA GUI 1.1.1 software for each individual element. Based on the principal components, cluster analysis was used to group similar spectra in the stack data set and produce cluster maps and spectra100. Spectra were then normalized as described for NEXAFS. We interpret the number of unique cluster spectra as a measure of the spatial and chemical heterogeneity of C functional groups within a sample.

Nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS)

Following STXM–NEXAFS analysis, the Si3N4 windows holding the clay samples were measured at the NanoSIMS facility at the Technical University of Munich. A NanoSIMS 50L (Cameca, Gennevilliers, France) was used to analyze the spatial distribution of exudate-derived 13C (as 13C12N− ions) and soil minerals, which was calculated according to the formula:

The Cs+ source was used to conduct a total of 17 measurements on non-rhizosphere and rhizosphere samples, including regions previously analyzed by STXM–NEXAFS, to measure the spatial distribution of 16O−, 12C2−, 13C12C−, 12C14N−, 31P−, 27Al16O−, and 56Fe16O−. Samples with regions of 13C enrichment or samples previously analyzed with STXM–NEXAFS (11 samples in total) were then scanned with the O− RF plasma source to measure the spatial distribution of 23Na+, 24Mg+, 27Al+, 39K+, 40Ca+, and 56Fe+. Both primary Cs+ and O− ion sources were tuned to match an imaging resolution of ~120 nm with a field of view of 30 µm × 30 µm at 256 pixels with 30–40 consecutive planes. The dwell time was 1 ms pixel−1 at a primary current of 2 pA.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R v4.3.194. The effects of soil moisture treatment (dry vs. moist), soil location (rhizosphere vs. non-rhizosphere), and size fraction, and their interactions, on total C, total N, C:N, δ15N, and amount of 13C and 12C, were evaluated with a three-way ANOVA using the aov function from the stats package, where variable selection in the final models was done based on the Akaike’s Information Criteria using the step function. Differences were then evaluated using two-sided tests with the emmeans function in emmeans package101 with a Tukey HSD correction for multiple comparisons.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data required to reproduce the manuscript results, including tabular data and images, are available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12608811.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1783–1838 (2019).

Saleem, M. et al. Cover crop diversity improves multiple soil properties via altering root architectural traits. Rhizosphere 16, 100248 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Kaye, J. P., Bradley, B. A., Amsili, J. P. & Suseela, V. Cover crop functional types differentially alter the content and composition of soil organic carbon in particulate and mineral-associated fractions. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5831–5848 (2022).

Kell, D. B. Breeding crop plants with deep roots: their role in sustainable carbon, nutrient and water sequestration. 407–418 https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcr175 (2011).

Panchal, P., Preece, C., Peñuelas, J. & Giri, J. Soil carbon sequestration by root exudates. Trends Plant Sci .27, 749–757 (2022).

Pausch, J. & Kuzyakov, Y. Carbon input by roots into the soil: quantification of rhizodeposition from root to ecosystem scale. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 1–12 (2018).

Heckman, K. A. et al. Soil organic matter is principally root derived in an Ultisol under oak forest. Geoderma 403, 115385 (2021).

Rasse, D. P., Rumpel, C. & Dignac, M. F. Is soil carbon mostly root carbon? Mechanisms for a specific stabilisation. Plant Soil 269, 341–356 (2005).

Austin, E. E., Wickings, K., McDaniel, M. D., Robertson, G. P. & Grandy, A. S. Cover crop root contributions to soil carbon in a no-till corn bioenergy cropping system. GCB Bioenergy 9, 1252–1263 (2017).

Mazzilli, S. R., Kemanian, A. R., Ernst, O. R., Jackson, R. B. & Piñeiro, G. Greater humification of belowground than aboveground biomass carbon into particulate soil organic matter in no-till corn and soybean crops. Soil Biol. Biochem. 85, 22–30 (2015).

Kuzyakov, Y. & Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: concept & review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 83, 184–199 (2015).

Bai, Y. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603–608 (2022).

Jackson, R. B. et al. The ecology of soil carbon: pools, vulnerabilities, and biotic and abiotic controls. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 48, 419–445 (2017).

Villarino, S. H., Pinto, P., Jackson, R. B. & Piñeiro, G. Plant rhizodeposition: a key factor for soil organic matter formation in stable fractions. Sci. Adv. 7, 3176–3190 (2021).

Kuijken, R. C. P., Snel, J. F. H., Heddes, M. M., Bouwmeester, H. J. & Marcelis, L. F. M. The importance of a sterile rhizosphere when phenotyping for root exudation. Plant Soil 387, 131–142 (2015).

Angst, G., Kögel-Knabner, I., Kirfel, K., Hertel, D. & Mueller, C. W. Spatial distribution and chemical composition of soil organic matter fractions in rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil under European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Geoderma 264, 179–187 (2016).

Sokol, N. W., Sanderman, J. & Bradford, M. A. Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 12–24 (2019).

Poirier, V., Roumet, C. & Munson, A. D. The root of the matter: linking root traits and soil organic matter stabilization processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 120, 246–259 (2018).

Fossum, C. et al. Belowground allocation and dynamics of recently fixed plant carbon in a California annual grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 165, 108519 (2022).

Ghezzehei, T. A., Sulman, B., Arnold, C. L., Bogie, N. A. & Asefaw Berhe, A. On the role of soil water retention characteristic on aerobic microbial respiration. Biogeosciences 16, 1187–1209 (2019).

Sokol, N. W. & Bradford, M. A. Microbial formation of stable soil carbon is more efficient from belowground than aboveground input. Nat. Geosci. 12, 46–53 (2019).

Dijkstra, F. A., Zhu, B. & Cheng, W. Root effects on soil organic carbon: a double-edged sword. New Phytol. 230, 60–65 (2021).

Jilling, A., Keiluweit, M., Gutknecht, J. L. M. M. & Grandy, A. S. Priming mechanisms providing plants and microbes access to mineral-associated organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 158, 108265 (2021).

Ridgeway, J., Kane, J., Morrissey, E., Starcher, H. & Brzostek, E. Roots selectively decompose litter to mine nitrogen and build new soil carbon. Ecol. Lett. 00, 1–11 (2023).

Dijkstra, F. A., Carrillo, Y., Pendall, E. & Morgan, J. A. Rhizosphere priming: a nutrient perspective. Front. Microbiol. 4, 216 (2013).

Walter, M., Kraemer, S. M. & Schenkeveld, W. D. C. The effect of pH, electrolytes and temperature on the rhizosphere geochemistry of phytosiderophores. Plant Soil 418, 5–23 (2017).

Kreuzeder, A. et al. In situ observation of localized, sub-mm scale changes of phosphorus biogeochemistry in the rhizosphere. Plant Soil 424, 573–589 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Simple plant and microbial exudates destabilize mineral-Associated organic matter via multiple pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3389–3398 (2021).

Keiluweit, M. et al. Mineral protection of soil carbon counteracted by root exudates. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 588–595 (2015).

Georges Martial, N., Yao, S., Hamer, U., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, B. Positive and negative priming effects induced by freshly added mineral-associated oxalic acid in a Mollisol. Rhizosphere 26, 100708 (2023).

Carvalhais, L. C. et al. Root exudation of sugars, amino acids, and organic acids by maize as affected by nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and iron deficiency. 3–11 https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201000085 (2011).

Gargallo-garriga, A. et al. Root exudate metabolomes change under drought and show limited capacity for recovery. 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30150-0 (2018).

Preece, C. & Peñuelas, J. Rhizodeposition under drought and consequences for soil communities and ecosystem resilience. Plant Soil 409, 1–17 (2016).

de Vries, F. T. et al. Changes in root-exudate-induced respiration reveal a novel mechanism through which drought affects ecosystem carbon cycling. New Phytol. 224, 132–145 (2019).

Liang, G., Stark, J. & Waring, B. G. Mineral reactivity determines root effects on soil organic carbon. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–10 (2023).

Neurath, R. A. et al. Root carbon interaction with soil minerals is dynamic, leaving a legacy of microbially derived residues. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 13345–13355 (2021).

Chari, N. R. & Taylor, B. N. Soil organic matter formation and loss are mediated by root exudates in a temperate forest. Nat. Geosci. 15, 1011–1016 (2022).

Steinauer, K., Chatzinotas, A. & Eisenhauer, N. Root exudate cocktails: the link between plant diversity and soil microorganisms? Ecol. Evol. 6, 7387–7396 (2016).

Shinano, T., Cheng, W., Saito, K. & Oikawa, A. Metabolomic analysis of night-released soybean root exudates under highand low-K conditions. Plant Soil 456, 259–276 (2020).

Solomon, D. et al. Micro- and nano-environments of carbon sequestration: multi-element STXM-NEXAFS spectromicroscopy assessment of microbial carbon and mineral associations. Chem. Geol. 329, 53–73 (2012).

Shabtai, I. A. et al. Calcium promotes persistent soil organic matter by altering microbial transformation of plant litter. Nat. Commun. 14, 6609 (2023).

Cotrufo, M. F. & Lavallee, J. M. Soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: a synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration. in Advances in Agronomy Vol. 172, 1–66 (Academic Press, 2022).

Singh, M., Sarkar, B., Biswas, B., Bolan, N. S. & Churchman, G. J. Relationship between soil clay mineralogy and carbon protection capacity as influenced by temperature and moisture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 109, 95–106 (2017).

Schrumpf, M. et al. Storage and stability of organic carbon in soils as related to depth, occlusion within aggregates, and attachment to minerals. Biogeosciences 10, 1675–1691 (2013).

Stoner, S. et al. Relating mineral-organic matter stabilization mechanisms to carbon quality and age distributions using ramped thermal analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 381, 20230139 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Formation efficiency of soil organic matter from plant litter is governed by clay mineral type more than plant litter quality. Geoderma 412, 115727 (2022).

Kravchenko, A. N. et al. Microbial spatial footprint as a driver of soil carbon stabilization. 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11057-4 (2019).

Eickhorst, T. & Mueller, C. W. Correlative imaging reveals holistic view of soil microenvironments. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05245. (2019).

Ding, D., Zhao, Y., Feng, H., Peng, X. & Si, B. Using the double-exponential water retention equation to determine how soil pore-size distribution is linked to soil texture. Soil Tillage Res. 156, 119–130 (2016).

Shabtai, I. A. et al. Soil organic carbon accrual due to more efficient microbial utilization of plant inputs at greater long-term soil moisture. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 327, 170–185 (2022).

Cotrufo, M. F. et al. Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nat. Geosci. 8, 776–779 (2015).

Williams, A., Cotton, A., Mcfarlane, A. E., Rolfe, S. A. & Pierre, P. Metabolite profiling of non-sterile rhizosphere soil. 147–162 https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13639 (2017).

Moni, C., Derrien, D., Hatton, P. J., Zeller, B. & Kleber, M. Density fractions versus size separates: Does physical fractionation isolate functional soil compartments? Biogeosciences 9, 5181–5197 (2012).

Yu, W., Huang, W., Weintraub-Leff, S. R. & Hall, S. J. Where and why do particulate organic matter (POM) and mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) differ among diverse soils? Soil Biol. Biochem. 172, 108756 (2022).

Lohse, M. et al. The effect of root hairs on exudate composition: a comparative non-targeted metabolomics approach. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 415, 823–840 (2023).

Kleber, M. & Johnson, M. G. Advances in understanding the molecular structure of soil organic matter. in Advances in Agronomy Vol. 106, 77–142 (Elsevier Inc., 2010).

Chen, C., Dynes, J. J., Wang, J., Karunakaran, C. & Sparks, D. L. Soft X-ray spectromicroscopy study of mineral-organic matter associations in pasture soil clay fractions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6678–6686 (2014).

Keiluweit, M. et al. Nano-scale investigation of the association of microbial nitrogen residues with iron (hydr)oxides in a forest soil O-horizon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 95, 213–226 (2012).

Chan, C. S., Fakra, S. C., Edwards, D. C., Emerson, D. & Banfield, J. F. Iron oxyhydroxide mineralization on microbial extracellular polysaccharides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 3807–3818 (2009).

Chen, C & Sparks, D. L. Multi-elemental scanning transmission X-ray microscopy–near edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy assessment of organo-mineral associations in soils from reduced environments. Environ. Chem. 12, 64–73 (2015).

Nazari, M. et al. Mucilage polysaccharide composition and exudation in maize from contrasting climatic regions. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 587610 (2020).

Chenu, C. In Environmental Impacts of Soil Component Interactions: Land Quality, Natural and Anthropogenic Organics (eds. Huang, P. M., Berthelin, J., Bollag, J.-M. & McGill, W. B) Ch. 17 (CRC Press, 1995).

Liang, B. et al. Black carbon increases cation exchange capacity in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 70, 1719–1730 (2006).

Liu, X. et al. STXM and NanoSIMS investigations on EPS fractions before and after adsorption to goethite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 3158–3166 (2013).

Rumpel, C. et al. Nanoscale evidence of contrasted processes for root-derived organic matter stabilization by mineral interactions depending on soil depth. Soil Biol. Biochem. 85, 82–88 (2015).

Coskun, D., Britto, D. T., Shi, W. & Kronzucker, H. J. How plant root exudates shape the nitrogen cycle. Trends Plant Sci. 22 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2017.05.004 (2017).

Angst, G. et al. Soil organic carbon stocks in topsoil and subsoil controlled by parent material, carbon input in the rhizosphere, and microbial-derived compounds. Soil Biol. Biochem. 122, 19–30 (2018).

Davenport, R. et al. Decomposition decreases molecular diversity and ecosystem similarity of soil organic matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, 1–11 (2023).

Das, S. et al. Lower mineralizability of soil carbon with higher legacy soil moisture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 130, 94–104 (2019).

Garcia Arredondo, M. et al. Root-driven weathering impacts on mineral-organic associations in deep soils over pedogenic time scales. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 263, 68–84 (2019).

Sowers, T. D., Adhikari, D., Wang, J., Yang, Y. & Sparks, D. L. Spatial associations and chemical composition of organic carbon sequestered in Fe, Ca, and organic carbon ternary systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 6936–6944 (2018).

Rowley, M. C., Grand, S. & Verrecchia, É. P. Calcium-mediated stabilisation of soil organic carbon. Biogeochemistry 137, 27–49 (2018).

Barreto, M. S. C., Elzinga, E. J., Ramlogan, M., Rouff, A. A. & Alleoni, L. R. F. L. R. F. Calcium enhances adsorption and thermal stability of organic compounds on soil minerals. Chem. Geol. 559, 119804 (2021).

Rasmussen, C. et al. Beyond clay: towards an improved set of variables for predicting soil organic matter content. Biogeochemistry 137, 297–306 (2018).

Clarholm, M., Skyllberg, U. & Rosling, A. Organic acid induced release of nutrients from metal-stabilized soil organic matter - the unbutton model. Soil Biol. Biochem. 84, 168–176 (2015).

Sowers, T. D. et al. Spatially resolved organomineral interactions across a permafrost chronosequence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 2951–2960 (2020).

Possinger, A. R. et al. Co-precipitation induces changes to iron and carbon chemistry and spatial distribution at the nanometer scale. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 314, 1–15 (2021).

LaLind, J. S. & Stone, A. T. Reductive dissolution of goethite by phenolic reductants. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 961–971 (1989).

Fimmen, R. L., Cory, R. M., Chin, Y. P., Trouts, T. D. & McKnight, D. M. Probing the oxidation-reduction properties of terrestrially and microbially derived dissolved organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 3003–3015 (2007).

Chen, C., Dynes, J. J., Wang, J. & Sparks, D. L. Properties of Fe-organic matter associations via coprecipitation versus adsorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 13751–13759 (2014).

Rineau, F. et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus converts organic matter in plant litter using a trimmed brown-rot mechanism involving Fenton chemistry. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 1477–1487 (2012).

Amelung, W. et al. Carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur pools in particle-size fractions as influenced by climate. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 62, 172–181 (1998).

Hartmann, H., Ziegler, W. & Trumbore, S. Lethal drought leads to reduction in nonstructural carbohydrates in Norway spruce tree roots but not in the canopy. Funct. Ecol. 27, 413–427 (2013).

Zhalnina, K. et al. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 470–480 (2018).

Chaparro, J. M. et al. Root exudation of phytochemicals in arabidopsis follows specific patterns that are developmentally programmed and correlate with soil microbial functions. PLoS ONE 8, 1–10 (2013).

Hikino, K. et al. Dynamics of initial carbon allocation after drought release in mature Norway spruce—increased belowground allocation of current photoassimilates covers only half of the carbon used for fine-root growth. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 6889–6905 (2022).

Paterson, E., Thornton, B., Midwood, A. J. & Sim, A. Defoliation alters the relative contributions of recent and non-recent assimilate to root exudation from Festuca rubra. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 1525–1533 (2005).

Williams, A. et al. Comparing root exudate collection techniques: an improved hybrid method. Soil Biol. Biochem. 161, 108391 (2021).

Moore, D. M. & Reynolds, Jr. R.C. X-ray Diffraction and the Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals (Oxford University Press, 1989).

Solomon, D., Lehmann, J., Kinyangi, J., Liang, B. & Schäfer, T. Carbon K‐edge NEXAFS and FTIR‐ATR spectroscopic investigation of organic carbon speciation in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 69, 107–119 (2005).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Wojdyr, M. Fityk: a general-purpose peak fitting program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 1126–1128 (2010).

Heymann, K. et al. C 1s K-edge near edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) spectroscopy for characterizing functional group chemistry of black carbon. Org. Geochem. 42, 1055–1064 (2011).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing https://www.r-project.org/ (2023).

Signorell, A. et al. DescTools: tools for descriptive statistics. R Package. version 0.99.58. https://github.com/AndriSignorell/DescTools/ (2019).

Seyfferth, A. L. et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of geochemical controls on carbon cycling in a tidal salt marsh. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 282, 1–18 (2020).

Solomon, D. et al. Micro- and nano-environments of C sequestration in soil: a multi-elemental STXM-NEXAFS assessment of black C and organomineral associations. Chem. Geol. 438, 372–388 (2012).

Hitchcock, A. P. Analysis of X-ray images and spectra (aXis2000): a toolkit for the analysis of X-ray spectromicroscopy data. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 266, 147360 (2023).

Zeitvogel, F., Schmid, G., Hao, L., Ingino, P. & Obst, M. ScatterJ: an ImageJ plugin for the evaluation of analytical microscopy datasets. J. Microsc. 261, 148–156 (2016).

Lerotic, M. et al. Cluster analysis in soft X-ray spectromicroscopy: finding the patterns in complex specimens. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 144–147 1137–1143 (Elsevier, 2005).

Lenth, R. V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation (SitS 2034351). Funding of the NanoSIMS was by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation – 119111086, 451271024). Part of the research described in this paper was performed at the Canadian Light Source, a national research facility of the University of Saskatchewan, which is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the National Research Council (NRC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Government of Saskatchewan, and the University of Saskatchewan. We thank Kim Sparks of Cornell University for guidance on isotope labeling and analysis and Jacob Scharfetter for assistance in designing and building the plant labeling chamber.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.A.S. drafted and wrote the manuscript, designed and conducted experiments, and collected and analyzed data; B.H. designed and conducted experiments, collected and analyzed data, and provided critical revision of the article; S.A.S. collected and analyzed data, and provided critical revision of the article; C.H. collected and analyzed data; A.P. collected and analyzed data, and provided critical revision of the article; J.L. provided critical revision of the article; T.B. provided critical revision of the article. All authors have approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shabtai, I.A., Hafner, B.D., Schweizer, S.A. et al. Root exudates simultaneously form and disrupt soil organo-mineral associations. Commun Earth Environ 5, 699 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01879-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01879-6

This article is cited by

-

Vulnerability of mineral-organic associations in the rhizosphere

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Evidence for the existence and ecological relevance of fast-cycling mineral-associated organic matter

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

A state of art review on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling and efficient utilization in paddy fields

Plant and Soil (2025)

-

Potassium release from K-bearing minerals treated with organic acids under laboratory conditions

Discover Soil (2025)

-

Targeting the untargeted: Uncovering the chemical complexity of root exudates

Plant and Soil (2025)