Abstract

It is still unclear whether emissions reductions from electric vehicles can be achieved across different regions from a lifecycle perspective. Here we use the life cycle assessment model and Quasi Input-Output model to evaluate the carbon dioxide emissions and air pollutants of internal combustion engine vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, and battery electric vehicles in different provinces of China, with the provincial electricity consumption data and the sales data of electric vehicles. We find that battery electric vehicles have achieved 11.8% and 1.1% reduction in carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions, respectively, compared to internal combustion engine vehicles. In contrast, the emissions of sulfur dioxide and particulate matter 2.5 increased by 10% and 20%, respectively. Due to the coal-based power generation structure and the cold weather, the emission intensity of battery electric vehicles in most northern provinces is higher than that in southern provinces. From 2020 to 2030, improving technological progress and optimizing electricity mix will greatly assist in achieving emissions reduction. The results can help policy-makers better understand the emission characteristics and reasonably plan future emission reduction strategies in transportation.

Similar content being viewed by others

The transport sector is a significant contributor of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in China due to the combustion of fossil fuels, and therefore plays a crucial role in mitigating climate change1,2. Considering economic development and accelerated urbanization, the demand for transport activities is expected to grow in the coming decades, which will lead to an increase in transport-related GHG emissions and corresponding pressure on the environment3,4,5. In this case, transportation electrification is seen as an effective way to reduce emissions6,7,8. According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers report, the production and sales of electric vehicles (EVs) in China reached a record high of 1.366 million and 1.367 million respectively in 20209. China is now the largest EV market in the world. However, from a lifecycle perspective, the role of EVs in reducing environmental pollution has been questioned10,11,12. Promoting EVs, including battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), as an alternative to internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) can reduce on-road emissions, but their life cycle emissions also depend on the electricity mix, interprovincial electricity transmission, and local climatic conditions13,14,15,16,17. These factors vary greatly across different regions in China, resulting in different emissions from EVs and varied pathways of emissions reduction for different regions. Therefore, evaluating the life cycle emissions of EVs in different regions and identifying key steps for emission reduction will greatly assist the automobile industry itself as well as its upstream and downstream supply chains in their efforts to reduce emissions.

Many recent studies have evaluated the positive impacts of EVs, compared to ICEVs, on emissions reduction in the use stage18,19,20. However, when extended to the full life cycle, the findings are not the same21,22,23 (see Supplementary Table 1). This discrepancy arises from the fact that the emission reduction benefits of EVs cannot be solely attributed to the energy consumption during the use stage24. The production of EVs, especially the manufacturing of batteries, typically emits more emissions than ICEVs25,26,27,28. Furthermore, there is often an overlooked fact that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and air pollutants from EV use occur during the power generation and transmission processes29. EVs have zero emissions during the use stage, as no emissions are directly generated during electricity consumption. And the indirect emissions generated by the electricity demand of EV use largely depend on local power grids. Emissions from EVs exhibit regional variation30, with higher levels observed in regions characterized by high energy intensity31,32. Electricity transmission can impact EV emissions because when a portion of the consumed electricity is imported from other regional power grids, emissions are transferred to the generating regions through interconnected grid network33,34,35,36. Only a few studies compiled provincial electricity consumption portfolios from a variety of data sources to assess the life cycle GHG emissions of EVs37,38. However, these studies inaccurately characterize electricity emission intensity due to the oversimplification of equating the electricity consumption mix with the power generation mix.

Although many existing studies have explored the environmental impacts of EVs from various perspectives, the following problems remain unsolved. First, the previous studies that estimated EV emissions from a life cycle perspective base their parameter settings on the national average, but did not distinguish their geographic location. Second, the lack of a comprehensive understanding of emissions generated from the manufacturing stage of lithium batteries and vehicle itself under current production conditions may result in incomplete conclusions39. Third, some studies have overlooked the impacts of interprovincial electricity transmission on emissions by EVs during the use phase, resulting in lower accuracy of the calculated results.

In this study, we quantify the CO2 emissions and air pollutants of EVs by life cycle assessment and explore the emission reduction potential of EVs through cross-vehicle comparisons. Compared with existing studies, the contributions of this study are summarized as follows. First, we calculate the spatial distribution of life cycle emissions of EVs by using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change inventory method, thereby facilitating an examination of regional inequalities in environmental impacts of transportation electrification in China based on provincial-level data. Second, we improve the accuracy of estimating the emission intensity of EVs by tracking emissions flows caused by EVs through interprovincial electricity transmission and analyzing the geographic destinations of these flows using Quasi-Input-Output (QIO) model. We also perform scenario analyses to explore how the results are affected by different assumptions and comparison benchmarks. The findings can facilitate more precise estimations of regional emission reduction potentials by promoting EVs, thereby contributing to the rational planning of future development and policy support for EVs in different regions.

Results

The specific vehicle types investigated in this study include conventional ICEVs and two types of EVs (BEVs and PHEVs). This study employs the life cycle assessment model to estimate CO2 emissions and pollutants from different vehicle types (see Methods). This model encompasses a comprehensive cycle system, including material production, component manufacturing, vehicle assembly, and vehicle end-of-life (EOL) processes. We chose standard medium-sized vehicles as research objects because they have similar common components and different propulsion technologies, providing the most representative results for both current and future scenarios. The base year of the study is 2020.

Regional inequality of life-cycle emissions

The life-cycle emissions of BEVs in China vary greatly across provinces (Fig. 1). Overall, the provinces with higher emissions in 2020 are mainly located in the eastern region. Some provinces in the central and western regions, such as Hunan, Henan, Shaanxi, and Sichuan, also have higher emissions. This largely depends on the local sales volume of BEVs and aligns with the national strategy to promote BEVs. Guangzhou is an example whose emissions are significantly higher than those of other provinces in 2020. Although Guangdong has a lower emission intensity of BEVs, its BEV sales are much higher than those of other provinces. Local emissions from BEVs do not necessarily show a positive correlation with BEV sales. For example, the volume of emissions in Sichuan is lower than those of Shandong and Jiangsu, but annual EV sales are higher than in those provinces.

Environmental impact of different vehicles

Compared with ICEVs, BEVs generate lower CO2 emissions in most provinces, with higher emissions occurring in only a few provinces such as Hebei, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia. The nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) emissions of BEVs are slightly higher than those of ICEVs in northern regions, such as Heilongjiang, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia; whereas they are slightly higher than those of ICEVs in southern regions, such as Sichuan, Yunnan, and Tibet. However, sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions of BEVs in all provinces are noticeably higher than those of ICEVs (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 2b, the difference in life cycle CO2 emissions and air pollutants between PHEVs and ICEVs is relatively small.

CO2 emissions and pollutants of each stage of the selected vehicles in different provinces can be found in Supplementary Figs. 1–3. CO2 emissions from BEVs, PHEVs, and ICEVs in the whole vehicle use stage account for the highest proportion in the life cycle, reaching 51.41%, 60.17%, and 64.17%, respectively (Fig. 2c). CO2 emissions associated with material production for BEVs contribute approximately 40% to their life cycle emissions, whereas for ICEVs, emissions from this stage account for only 30%. The increased emissions from upstream material and energy production may limit the overall CO2 emission reduction benefits throughout the lifecycle. BEVs emit 6.67% more than ICEVs in material production stage. The share of NOx and PM2.5 emissions at each stage of the life cycle of the three vehicles is similar to those of CO2.

SO2 emissions from material production account for 53.59%, 55.81%, and 80.15% of the total life cycle emissions for BEVs, PHEVs, and ICEVs, respectively. These emissions primarily arise from the exploitation of mineral resources and the procurement of materials associated with lithium iron phosphate and other lithium battery components. The SO2 emissions from ICEVs during the use stage only account for 0.83%, significantly lower than those of BEVs and PHEVs, which are 28.83% and 31.81%, respectively. The main reason is that, compared to current electricity generation mix, gasoline has a lower SO2 emission intensity.

Overall, from the perspective of life cycle emissions, BEVs exhibit significant CO2 and NOx emission reduction benefits during the use stage. In addition to sales volume, regional differences in the emissions during the usage stage of BEVs are primarily attributed to the impacts of electricity mix and temperature (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The provincial temperature adjustment coefficient for BEV use is 1 to 1.24. Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang have mild climates, with an annual average temperature of 16–23 °C. BEVs have the lowest temperature adjustment coefficient, which is 1. In contrast, northern provinces are generally affected by the cold in winter, resulting in higher temperature adjustment coefficients. Here, the impact of the electricity mix is measured by comparing consumption-based electricity emissions with the national average level. The emissions of vehicle use from BEVs are higher than the national average in 23 out of 31 provinces, due to the large proportion of coal power in their electricity mix. Finally, after comprehensively considering the impacts of temperature and electricity, we obtained the emissions of CO2 and pollutants per kilometer driven by BEVs in each province (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Provincial CO2 emissions range from 7.09 g/km in Tibet to 158.68 g/km in Heilongjiang. The electricity dominates the interprovincial variation in emissions at the use stage in most provinces. For provinces characterized by low annual average temperatures (such as Heilongjiang, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, and Gansu) or high temperatures (such as Hainan), temperature is identified as a critical determinant contributing to variations in BEV operation emissions. Previous studies have calculated BEV emission intensities for various countries using different methods (Supplementary Table 2). The comparisons show that differences in grid emissions are the primary cause of the large variations in BEV emissions, further supporting the results of this study.

a presents the impact of electricity mix and temperature on emission of BEVs at the use stage. b presents electricity flow among different provinces. c presents emission flow among different provinces based on QIO due to the electricity consumption of BEVs. The names of provinces have been abbreviated, which is shown in Supplementary Table 3.

The provinces with higher exported emissions are geographically situated in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta. The provinces with large imported emissions are Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Shanxi, Guizhou, and Shaanxi. All these provinces have abundant electricity generation, and their imported emissions are generated to meet the electricity demand of other provinces. It can be seen emissions are generally shifted from the eastern to the western China, which is the opposite direction of electricity transmission (Fig. 3b, c). In other words, the transferred emissions from the large-scale application of BEVs show an east-to-west trend in China. Among them, the transferred emissions generated by BEVs at the use stage is most prominent in the route from Anhui to Xinjiang, with the amount of transferred emissions for CO2, SO2, NOx, and PM2.5 is 27.65 thousand tons (kt), 16.24 t, 13.64 t, and 1.65 t, respectively. To better present the important role of interprovincial electricity transmission in the emissions generated by EV at the use stage, Supplementary Fig. 7 presents the proportion of emissions shifted as a percentage of total emissions. It can be seen that ignoring the emission transfer caused by interprovincial electricity transmission may lead to errors in the calculation of the emissions of EVs. For example, the emission transfer from electricity consumption for BEVs at the use stage in Beijing accounts for more than 70% of the total emissions. It is important to note that CO2 emissions and pollutants are not always correlated and need to be tracked separately. For example, CO2 emissions flowing into Beijing account for 72.76% of the total emissions from BEVs at the use stage, while SO2, NOx, and PM2.5 emissions account for 86.89%, 58.66%, and 83.37% respectively. In general, higher SO2 transfers are usually the result of imported electricity being primarily coal-based, while water-dominated imported electricity generates relatively low transfer emissions.

The transfer of emissions within the regional power grid should not be ignored. Beijing and Hebei, both part of the North China Power Grid, have transferred large amounts of CO2 emissions and air pollutants to Inner Mongolia. Similar situations have also occurred in other regions, with some provinces acting as trade routes for electricity, importing and exporting CO2 emissions and air pollutants at the same time. For example, BEVs in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Chongqing, Guizhou, Tibet, and Shaanxi generated a total of 6.10 kt of CO2 transferred to Sichuan, while a total of 6.85 kt of CO2 were transferred from Sichuan to Chongqing, Yunnan, Tibet, Gansu, and Shaanxi. In addition, transferred emissions from provinces that import large amounts of electricity may not be high. For example, Guangdong has the highest electricity demand for BEVs and imported electricity among all provinces, but its exported emissions are lower than those of Beijing. This is because more than half of Guangdong’s imported electricity comes from Yunnan, where hydropower accounts for more than 80% of total electricity generation. This significantly reduces the emissions transfer effect of Guangdong. Emissions from BEVs in Guangdong are mainly shifted to Guizhou, which accounts for a larger share of coal generation, but the exported electricity of Guizhou is not the largest. Therefore, the expansion of BEV electricity consumption does not necessarily lead to an increase in emissions transfer. Similarly, although some provinces (such as Yunnan, Sichuan, and Qinghai) export large amounts of electricity to other provinces, they imported emissions are low. Qinghai sends 22.67 billion kWh of electricity to Gansu, accounting for more than half of local imports, but its specific emissions are only 2.26 kt of CO2, 1.46 t of SO2, 1.18 t of NOx and 0.15 t of PM2.5, accounting for about 30% of the exported emissions. The main reason for this is that the regional electricity mix is dominated by non-fossil energy sources.

The emission intensities of electricity consumption in each province can be divided into local and transferred components, resulting in varying degrees of differences between the consumption-based and generation-based emission intensities of electricity across provinces (see Supplementary Fig. 8). These differences can be summarized in the following three aspects: (1) When a province with a polluted electricity mix imports cleaner electricity from other province, the generation-based emission intensity is higher than the consumption-based emission intensity. For example, Shanghai produces electricity mainly from coal produced but imports it primarily from Hubei and Sichuan, which rely heavily on hydroelectricity. (2) When a province imports electricity with higher emission intensity than locally generated electricity, its consumption-based emission intensity exceeds the generation-based emission intensity. Beijing is exemplary of this, as its imported electricity mainly comes from Inner Mongolia and Shanxi, where power generation is dominated by fossil fuels, contributing to higher pollution levels and deteriorating its electricity mix. Interprovincial electricity transmission leads to a more than threefold increase in its consumption-based SO2 emission intensity compared to its generation-based emission intensity. Similar situations also occurred in Sichuan, Tibet, and Qinghai. (3) When the emission intensity of imported electricity is similar to that of local electricity generation, the consumption-based and generation-based emission intensities of the province can be considered to be the same. This is the case for most provinces in China, where imports of electricity from other provinces do not change the generation-based emission factor by more than 5%.

Emission reduction potential and pathways

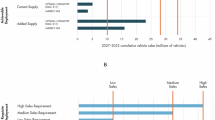

Emissions from the use stage of EVs are more susceptible to exogenous factors, especially the local electricity mix and interprovincial electricity transmission than with other phases. Therefore, we developed eight emission scenarios in this subsection to predict the emission reduction potentials of the future promotion of EVs in the use stage. These scenarios are S40%, S60%, S80%, and S100% BEVs and PHEVs, respectively. The “40%” rate level in the 40%-BEV% scenario indicates that BEV sales account for 40% and ICEV sales account for 60%. The future pathways to promote EVs are further analyzed by combining the provincial electricity mix in 2020 with the low-cost renewable energy scenario in 203040. Supplementary Table 4 shows the provincial-level electricity mix in the low-cost renewable energy scenario in 2030. Figure 4a shows the emission trends of vehicle use from 2020 to 2030. With the optimization of electricity mixes across provinces, emission intensities of BEVs and PHEVs continue to decline. CO2 emission intensity of BEVs in 2030 would be half of those of 2020. In contrast, the emission intensity of ICEVs is only affected by energy efficiency, with insignificant changes. The advantage of ICEVs over BEVs and PHEVs is low SO2 emissions.

As shown in Fig. 4e, CO2 emissions in 2020 range from 23.6 million tons (mt) in the S40%-BEV scenario to 22.3, 21.0, and 19.6 mt under the scenarios of 60%-BEV%, 80%-BEV%, and 100%-BEV%, respectively. Meanwhile, due to the improvement of energy efficiency and the use of clean energy, CO2 emissions are projected to decrease to 15.8, 12.8, 9.7, and 6.7 mt by 2030, respectively. Compared to the promotion of BEV, there has been a significant increase in the trajectory of CO2 emissions when promoting PHEV, ranging from 26.4 mt (100%-PHEV% scenario in 2020) to 15.9 mt (100%-PHEV% scenario in 2030).

The SO2 reduction benefit of promoting BEVs is significantly lower than that of PHEV and ICEV in 2020, and the SO2 emissions increase with BEV penetration levels. As expected, the advantages of BEVs come to the fore as renewable energy generation continues to increase. By 2030, the SO2 emissions of PHEVs and BEVs will be nearly identical, as is shown in Fig. 4b. Regarding the emission trajectory, it is found that BEV performs better than PHEV in terms of CO2, NOx, and PM2.5 emission reduction benefits with the same level of sale (Fig. 4e, g, h). Moreover, the advantages of BEVs in reducing PM2.5 emissions compared to ICEVs only become evident after 2022.

Discussion

Transportation electrification is an important step in promoting the decarbonization of China’s transportation sector and achieving emission reduction targets. This study quantifies the life cycle CO2 emissions and air pollutants of three types of vehicles. Additionally, we analyzed the heterogeneity in emission intensity of electricity across provinces in terms of interprovincial electricity transmission. The results show that the differences in vehicle life cycle emissions primarily stem from vehicle use. At the national level, the promotion of BEVs can reduce CO2 and NOx emissions, but increase SO2 and PM2.5 emissions. However, in northern provinces of China, where coal-based electricity generation structure and cold weather are prevalent, replacing ICEVs with BEVs may not reduce CO2 emissions and air pollutants over their lifecycle. It is also found that adoption of BEVs has undoubtedly exacerbated the problem of interprovincial emissions transfers. The main pathway is the transfer of emissions from the developed regions in the east to the less developed regions in the central and western regions, and there are also emission transfers within regional power grid.

Other studies have supported the results of this study to some extent. In the use stage, electricity transmission alters the spatial distribution of BEV emissions from an inter-provincial perspective. Emissions generated by BEVs not only impact the local environment but also affect electricity-exporting regions. For example, Wang et al.13 demonstrated that the life cycle GHG emissions of BEVs in Beijing are lower than those of ICEVs. Nevertheless, because of the “neighbor effect”, achieving overall emission reductions remains challenging. This is consistent with the concept of transferred emissions mentioned in this study. Emissions associated with electricity consumption account for a significant portion of BEV life cycle emissions, and a cleaner electricity production structure can significantly reduce GHG emissions. Reductions in CO2 and emissions and air pollutants from BEVs in regions dominated by fossil energy sources are still difficult to achieve. BEV emissions from the southern China grid in 2015 were 47% lower than those from BEVs charging on the northern China grid, as suggested by Shen et al.31.

As EVs enter the large-scale marketing phase, the life cycle assessment model developed in this study will help systematically explore the environmental impacts of EVs and support the development of promotion strategies in various regions. Based on our findings, we proposed several policy recommendations for promoting BEVs to reduce CO2 and air pollutants.

In the life cycle of BEVs, CO2 emissions and air pollutants from material production, parts manufacturing, assembly and distribution, vehicle maintenance and EOL stages cannot be ignored. For automakers and downstream supply chain practitioners, some policy suggestions are offered. First, the material production and parts manufacturing facilities should be located in areas with high utilization of renewable energy because of large energy consumption and emissions of production and manufacturing process. Efficient utilization of renewable energy can effectively reduce emissions at this step. Additionally, the use of advanced lightweight materials enables the reduction of vehicle weight, which further mitigates environmental stress41,42. Second, power plants that emit high air pollutants such as PM2.5 and SO2 should be upgraded to reduce indirect emissions from BEVs. Specific retrofitting measures include the use of advanced environmental protection equipment, such as dust collectors and desulfurizers, to reduce emissions from the combustion process.

This study finds that emissions caused by the promotion of BEVs may be transferred to other provinces due to interprovincial electricity transmission. In particular, a large portion of emissions in provinces such as Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Shanxi is generated to meet the electricity demand of other provinces43. Therefore, the interprovincial mobility of emissions and the resulting liability for environmental damage should be reflected in BEV promotion policies. The government should consider strengthening emission control in provinces with large electricity exports and refining the division of provincial responsibility for emissions reduction when allocating emission reduction tasks. Meanwhile, it is necessary to explore a compensation mechanism for emissions resulting from provincial electricity production and consumption, so as to facilitate the coordinated mobilization of funds and technologies to control emissions in provinces with high adoption rates of EVs or large amounts of electricity generation44. For example, provinces with more BEVs and imported electricity could invest in cleaner technologies in resource-rich provinces to ensure that electricity consumers share the responsibility for controlling transferred emissions43. In addition, economic instruments such as environmental taxes and a unified national transportation carbon market can be used to provide safeguards for environmental governance in power supply provinces. The external costs of emissions transfers could also be internalized by incorporating the cost of environmental damage in setting prices for vehicle purchases and charging, thereby financing pollution management in these provinces.

As BEV ownership continues to rise, the consumption of electricity to secure BEV use will also increase. From the perspective of electricity consumption characteristics, we propose the following recommendations for promoting the use of BEVs. Some southern provinces (such as Guangdong and Shanghai) are expected to remain leaders in BEV sales in the future, which will not only increase local emissions but also affect other provinces due to electricity transmission. Therefore, these provinces should improve the efficiency of their energy use to reduce overall emissions. Upgrading grid infrastructure and integrating smart grid technologies can optimize power distribution and utilization. Currently, northern provinces have high emission intensities of electricity attributed to their reliance on coal-dominated electricity generation. In these provinces, investing in renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, can significantly reduce reliance on coal. Implementing policies that incentivize the adoption of clean energy can drive energy structure transition45. For example, providing subsidies for renewable energy projects or imposing stricter emissions regulations on coal power plants can encourage a shift to cleaner energy sources.

The main limitation of this study is that the QIO model used is just a possible way to simulate electricity flows of the power grid, which does not reflect the reality of power distribution by the grid. As a result, the actual emissions embodied in the EV electricity consumption are theoretically different from the annual average, thus affecting the assessment of the emission footprint. Emissions transfer is only considered in the vehicle use phase, which is ignored in other phases involving electricity consumption. In addition, transportation electrification focuses not only on passenger cars, but also on other modes such as buses, subways, and urban light rail. In view of the above limitations, a detailed vehicle energy consumption analysis is needed to assess the emission footprint in future studies, and energy structure adjustments and additional vehicle types should also be considered in scenario design.

Methods

Life cycle assessment model

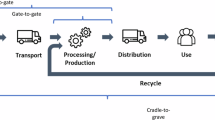

The vehicle life cycle emissions are estimated using the Tsinghua life cycle assessment model, which is a compilation of the inputs and outputs of vehicle systems over their life cycle to obtain potential environmental impacts, thereby avoiding partial comprehension that may result from limitations in scope46. The framework of this study includes the vehicle cycle and fuel cycle for both ICEVs, PHEVs, and BEVs (Fig. 5). The vehicle cycle mainly includes material production, vehicle manufacturing, vehicle use, and scrap recycling. The fuel cycle, which includes the production of fuel (i.e., Well to Pump) and the use of energy (i.e., Pump to Wheels), refers to WTW (i.e., Well to Wheels). As a result, the aim of this study is to effectively and quantifiably analyze and assess energy and environmental issues encompassed by the “cradle to grave” life cycle, considering not only the direct impacts arising from vehicle production, usage, and scrappage, but also the indirect impacts from material and energy inputs.

The details of vehicle specifications are given in Supplementary Information. Supplementary Table 5 lists the detailed material composition of selected ICEV, PHEV and BEV, according to their bill of materials47,48. The curb weight of BEV and PHEV exceeds that of ICEV by 24% and 10% respectively, owing to the fact that the electric powertrain components including the battery pack are heavier than the internal combustion engine and fuel tank. In terms of major component materials, steel is the most common material, accounting for 62.3%, 65.2%, and 59.1% of the mass of major components of ICEV, PHEV, and BEV, respectively. Technical parameters for all vehicle types are given in Supplementary Table 6. In the driving phase of the PHEV, the ratio of electricity and gasoline consumption is set as 50%, respectively49. This study assumed that the lifetime and life cycle driving kilometer of vehicles are 10 years and 150,000 km, respectively. These technical details have been used in the estimation of the CO2 emissions and air pollutants at the vehicle model level.

Calculation of CO2 emissions and pollutants

The life-cycle CO2 emissions and air pollutants of ICEV, PHEV, and BEV can be summarized as follows: material production, parts manufacturing, vehicle assembly, vehicle distribution, vehicle use, vehicle maintenance, and vehicle EOL. Based on this, we have established a mathematical model representing vehicle emissions. The total emissions \({E}_{n}\) generated by promoting BEVs in province \(n\) are equal to the sales volume of BEVs \({sal}{e}_{n}\) multiplied by the sum of the emissions generated in each stage mentioned above.

The material production stage encompasses mineral extraction, ore beneficiation, ore smelting, and metal refining. In addition, it also includes polymer production such as petroleum and natural gas recovery, and raw material synthesis. The CO2 emissions and air pollutants in this stage consist of direct (non-combustion) emissions from the production of raw materials and indirect (combustion) emissions from energy consumption. Emission caused by material production is described in Eq. (2).

where \(C{E}_{{VP}}\) denotes the emissions from the production of raw materials (kg); \({m}_{k}\) denotes the weight of material \(k\) (t); \(G{E}_{k}\) denotes the non-combustion carbon emissions associated with material \(k\) (kg/t); \(E{C}_{j,k}\) denotes the emission factor of energy \(j\) related to the material \(k\) (MJ/t); \(E{F}_{j}\) denotes the carbon emission factor of the energy \(j\) (kg/kJ).

As outlined in Supplementary Table 5, ICEVs, PHEVs, or BEVs are manufactured from a variety of materials, each with different emission factors and energy consumption. The emission factors of different materials and the energy consumption required for production in China are shown in Supplementary Table 7 and Table 848,50,51. Supplementary Table 9 complements Supplementary Table 7 by highlighting the life cycle emission factors for CO2 and air pollutants for different energy types.

The stage of parts manufacturing involves various mechanical and chemical procedures, including casting, rolling, stamping, and wire drawing, among others52. The CO2 emissions and air pollutants during this process arise from indirect emissions generated by the energy consumption intrinsic to the manufacturing process. Emission caused by parts manufacturing can be calculated as Eq. (3):

where \(C{E}_{{VM}}\) denotes the emissions from component manufacturing (kg); \(E{C}_{{PM},j}\) denotes the energy consumption of energy \(j\) per vehicle during the stage of part manufacturing (MJ).

For this stage of energy consumption, we only considered the consumption of primary fuels such as natural gas, coal, and electricity53 (see Supplementary Table 10).

The stage of vehicle assembly encompasses a range of activities, including painting, heating, material handling, welding, workshop compressed air, and battery assembly54. Supplementary Table 11 shows the detailed energy consumption for each activity in this stage. The CO2 emissions and air pollutants during this stage derive from the energy consumption involved in the assembly process of the vehicle. Emissions caused by vehicle assembly can be expressed by Eq. (4).

where \(C{E}_{{VA}}\) denotes the emissions from vehicle assembly (kg); \({W}_{{ve}h}\) denotes the total weights of the ICEV/BEV (kg); \(E{C}_{{VA},j}\) denotes the consumption of energy \(j\) during the vehicle assembly stage (MJ/kg).

The vehicle distribution stage refers to the transportation of vehicles from the production base to the location of the dealers. CO2 emissions and air pollutants in this stage come from the fuel consumed in the distribution process, determined by the distribution distance as well as the fuel consumption of the chosen mode of transport. Then the vehicle emission is calculated by Eq. (5).

where \(G{E}_{{VD}}\) denotes fuel consumption emissions from vehicle distribution (kg); \({\alpha }_{j}\) denotes the coefficient of energy consumption (in kJ kg−1 km−1); \({d}_{n}\) denotes distance of intra-provincial transportation (km); \(d{t}_{n}\) denotes for the distance between province \(m\) and closest production base (km); \({d}_{{nq}}\) denotes for the distance between two provinces (km).

To assess the major influences of vehicle distribution, this study assumes that manufacturers use the standard 20 t-load trucks, which can transport approximately eight cars at a time. The diesel consumption of this truck is 39.5 L/100 km55. We have calculated the emission intensities of all pollutants according to the China V standard. Detailed information is shown in Supplementary Table 1256,57.

The largest manufacturing base in each region is selected as the delivery point. Each province selects the nearest manufacturing base as its delivery point to reduce the transportation cost. If a province has its own manufacturing base, the set distribution distance is ~100 km. The province in which the selected delivery point (marked with an asterisk) is situated for each region is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 9. The distances between the two provinces are shown in Supplementary Table 13.

In the vehicle use stage, CO2 emissions and air pollutants are determined by the vehicle kilometer traveled, and fuel consumption. Different types of vehicles use different fuels, including gasoline and electricity. Emission caused by vehicle use can be expressed by Eq. (8).

where \(C{E}_{{VU}}\) represents the emission of vehicle use (kg); \({VKT}\) and \(N\) represent the annual mileage (km) and service life (years), respectively; \(R{T}_{i,n}\) represents energy consumption ratio of vehicle \(i\) in province \(n\); \(f\) represents the type of transportation fuel, including gasoline and electricity, \(E{C}_{f}\) represents the unit mileage fuel consumption of transportation fuel \(f\) in province \(n\) (L/km; kWh/km); \(E{F}_{f,u}\) represents the emission of substance \(u\) of transportation fuel \(f\) (kg/L; kg/kWh).

During the vehicle maintenance stage, CO2 emissions and air pollutants are primarily determined by the frequency of replacement of parts and their carbon emission factors. Emission caused by vehicle maintenance can be expressed by Eq. (9).

where \(G{E}_{{VR}}\) represents the emissions of vehicle maintenance (kg); \({T}_{p}\) represents the replacement frequency of part \(p\); \(G{E}_{p}\) represents the emission factor of part \(p\) (kg/time).

The frequency of replacement for various components should comply with the guidelines outlined in the automobile use handbook. The fluids include brake fluid, transmission fluid, windshield fluid, and powertrain coolant. As the vehicle’s mileage gradually increases, these fluids need to be replaced at the right time due to aging and contamination. In addition to the fluids, the tire and lead-acid battery are also essential components requiring attention during vehicle maintenance. Regular professional check-ups and necessary replacements are needed for these two components as well, to maintain regular operation of the vehicle. During the entire lifetime, the replacing times and emission factors of different components are listed in Supplementary Table 1448.

In the vehicle end-of-life stage, considering the differences in production processes and complexities between the vehicle body and power battery, this study calculates their CO2 emissions and air pollutants separately. The emissions in this stage are determined by the disposal energy consumption factor (including both the vehicle body and the power battery), the vehicle mass (including both the vehicle body and the power battery), and the carbon emission factor of the energy. The primary source of energy consumed during this phase is electricity52. Emission in this step can be calculated as Eq. (10).

where \(G{E}_{{EOL}}\) represents the emissions of vehicle scrapping (kg); \({\alpha }_{m}\) and \({\alpha }_{b}\) respectively represent the disposal energy consumption factors of the vehicle body and power battery (MJ/kg); \({M}_{m}\) and \({M}_{b}\) respectively represent the mass of the vehicle body and the power battery (kg). \({\alpha }_{m}\) and \({\alpha }_{b}\) are set as 0.37 and 31, respectively.

Impact of temperature on vehicle use

China is a vast country with vast variations in regional weather and climate, so considering temperature influence is important for provincial-level analysis58. In this study, the temperature of each province is represented by the temperature of its capital city. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the average temperature of each province in the year 2020. Data is obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics59.

To represent the impact of temperature on vehicle use across different provinces in China, we employed Eq. (11) to estimate the correlation between energy consumption and ambient temperature.

where \(R{T}_{i,n}\) is the temperature adjustment coefficient; \({t}_{n}\) is the temperature that vehicle faces in province \(n\) (°C); the values of the coefficient \({\alpha }_{1}\) are 0.0129, 0.0183, and 0.0210 for ICEV, PHEV, and BEV, respectively; the values of coefficient \({\alpha }_{2}\) are 0.0064, 0.0154, and 0.0242 for ICEV, PHEV, and BEV, respectively15.

Impact of electricity on vehicle use

In China, there are significant differences in electricity generation mix of different provinces (see Supplementary Fig. 4). The North and Northeast provinces have the highest proportion of the coal electricity. Renewable electricity in the central provinces comes mainly from hydropower plants along the Yangtze River. For the Eastern power grid, nuclear electricity constitutes a significant component of the non-fossil energy supply. The Northwest power grid has a higher proportion of electricity generation from wind and solar than the other grids. The proportion of fossil-fueled thermal electricity generation is low throughout the South, with hydroelectricity standing as a crucial electricity source. Emission rates of electricity generation are provided in Supplementary Table 15.

It is important to note that the electricity consumed by a certain province in the real interconnected power grid not only originates from the province itself but also from other provinces that are directly or indirectly interconnected through the network60. In this case, the emission factor of electricity consumption in Eq. (8) needs to be improved to capture the impact of interprovincial electricity exchanges. We implemented the QIO model, proposed by ref. 34 to emulate interprovincial electricity transmission and then quantified CO2 emissions and air pollutants resulting from electricity utilization within the province. Each provincial grid is modeled as a node, and interprovincial electricity flows are considered as links in the model. At the electricity supply-demand equilibrium, the aggregate of local electricity generation and the electricity imported from other provinces equates to local electricity consumption plus the electricity exported. Consequently, the balance of interprovincial electricity flow can be expressed as:

where \({y}_{n}\) represents the electricity flow of province \(n\); \({p}_{n}\) and \({c}_{n}\) represent the electricity generation and consumption of province \(n\), respectively; \({T}_{{mn}}\) and \({T}_{{nm}}\) represent the amount of electricity transferred from province \(m\) to \(n\) and from province \(n\) to \(m\). Thus, the relationship of interprovincial electricity transmission can be expressed by the matrix \(T\).

To obtain the share of interprovincial transmission in the total electricity flow, the matrix \(\beta\) is used to represent the interprovincial transmission coefficients.

where \(\hat{y}\) is the diagonal matrix of the electricity flow vector \(y\). Based on Eqs. (12), (14), we can derive the following equation:

where \(p\) is 1 by \(n\) vector that represent the electricity generation. According to Eq. (15), \(y\) is further derived as follows:

Similarly, emissions in electricity flows can be calculated as the emissions embodied in the local electricity generation and the electricity imported from other provinces, that is

where \({e}_{n}^{y}\) and \({e}_{n}^{p}\) represent the emissions in electricity flow and generation of province \(n\), respectively; \({\beta }_{{mn}}\) represents the ratio of electricity flowing from province \(m\) to \(n\). Similar to \({e}_{n}^{y}\) and \({e}_{n}^{p}\), \({e}^{y}\) and \({e}^{p}\) are 1 by \(n\) vectors that represent the emissions in electricity flows and generation, respectively.

According to Eqs. (12)–(18), the emission vector for consumed electricity can be derived as follows:

where \({e}^{c}\) is 1 by \(n\) vector that represent the emissions in consumed electricity; \(\hat{c}\) is the diagonal matrix of the electricity consumption vector \(c\).

Finally, the emission factors of electricity consumption in each province are the 1 by \(n\) vector \(\frac{{e}^{c}}{c}\).

Data sources and assumption

This study divided China into 31 provincial electricity grids according to administrative boundaries. The provincial grid of Taiwan was not considered owing to a lack of relevant data. The first category is provincial power structure dataset in 2020. Data on electricity generation and electricity consumption by each province were sourced from the China Electricity Yearbook61. The electricity exported by provinces and inter-provincial power flow relationships were sourced from the Compilation of Statistical Data of Power Industry62 and the Annual Development Report of China’s Electric Power Industry63, respectively. We aggregated the data at the provincial level, assuming that electricity consumed in each province is derived from a mix of locally generated and purchased electricity. Hence, the emission intensity of electricity consumption in each province is calculated based on the electricity consumption mix and emission factors of power generation types.

The second category is vehicle information. The provincial BEV sales for 2020 were collected from the China Automobile Industry Yearbook64 and available public statistics on BEVs, which provided a comprehensive overview of the number of new BEVs sold in 31 provinces of China for that year.

The last category of data is the vehicle life cycle inventory data. These data include vehicle type, curb weight, battery weight, and fuel consumption, with detailed information provided in the Supplementary Information. We assumed these data to be homogeneous across the provinces.

Data availability

The database that supports the findings of this study is available from https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9XMRE65. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code implementation is done in the R programming language version 4.1.0. The codes are available from https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9XMRE.

References

Xue, X. et al. Transportation decarbonization requires lifecycle-based regulations: evidence from China’s passenger vehicle sector. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 118, 103725 (2023).

Zhang, R. & Hanaoka, T. Cross-cutting scenarios and strategies for designing decarbonization pathways in the transport sector toward carbon neutrality. Nat. Commun. 13, 3629 (2022).

Huang, Y., Zhu, H. & Zhang, Z. The heterogeneous effect of driving factors on carbon emission intensity in the Chinese transport sector: evidence from dynamic panel quantile regression. Sci. Total Environ. 727, 138578 (2020).

Wang, H., Ou, X. & Zhang, X. Mode, technology, energy consumption, and resulting CO2 emissions in China’s transport sector up to 2050. Energy Policy 109, 719–733 (2017).

Duan, S., Qiu, Z., Liu, Z. & Liu, L. Impact assessment of vehicle electrification pathways on emissions of CO2 and air pollution in Xi’an, China. Sci. Total Environ. 893, 164856 (2023).

Woody, M., Keoleian, G. A. & Vaishnav, P. Decarbonization potential of electrifying 50% of US light-duty vehicle sales by 2030. Nat. Commun. 14, 7077 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Hidden delays of climate mitigation benefits in the race for electric vehicle deployment. Nat. Commun. 14, 3164 (2023).

Qiu, X., Zhao, J., Yu, Y. & Ma, T. Levelized costs of the energy chains of new energy vehicles targeted at carbon neutrality in China. Front. Eng. Manag. 9, 392–408 (2022).

China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM). Economic Performance of the Auto Industry in. http://www.caam.org.cn/chn/4/cate_39/con_5232916.html (2020).

Yu, A., Wei, Y., Chen, W., Peng, N. & Peng, L. Life cycle environmental impacts and carbon emissions: a case study of electric and gasoline vehicles in China. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 65, 409–420 (2018).

Ke, W., Zhang, S., He, X., Wu, Y. & Hao, J. Well-to-wheels energy consumption and emissions of electric vehicles: mid-term implications from real-world features and air pollution control progress. Appl. Energy 188, 367–377 (2017).

Lai, X. et al. Critical review of life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: a lifespan perspective. eTransportation 12, 100169 (2022).

Wang, L., Yu, Y., Huang, K., Zhang, Z. & Li, X. The inharmonious mechanism of CO2, NOx, SO2, and PM2. 5 electric vehicle emission reductions in Northern China. J. Environ. Manag. 274, 111236 (2020).

Yuksel, T. & Michalek, J. J. Effects of regional temperature on electric vehicle efficiency, range, and emissions in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 3974–3980 (2015).

Wu, D. et al. Regional heterogeneity in the emissions benefits of electrified and lightweighted light-duty vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10560–10570 (2019).

Choi, H., Shin, J. & Woo, J. Effect of electricity generation mix on battery electric vehicle adoption and its environmental impact. Energy Policy 121, 13–24 (2018).

Gan, Y. et al. Provincial greenhouse gas emissions of gasoline and plug-in electric vehicles in China: comparison from the consumption-based electricity perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6944–6956 (2021).

Andress, D., Nguyen, T. D. & Das, S. Reducing GHG emissions in the United States’ transportation sector. Energy Sustain. Dev. 15, 117–136 (2011).

Nimesh, V., Sharma, D., Reddy, V. M. & Goswami, A. K. Implication viability assessment of shift to electric vehicles for present power generation scenario of India. Energy 195, 116976 (2020).

García-Olivares, A., Solé, J. & Osychenko, O. Transportation in a 100% renewable energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 158, 266–285 (2018).

Li, F. et al. Regional comparison of electric vehicle adoption and emission reduction effects in China. Resour., Conserv. Recycling 149, 714–726 (2019).

Shafique, M. & Luo, X. Environmental life cycle assessment of battery electric vehicles from the current and future energy mix perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 303, 114050 (2022).

Xia, X., Li, P., Xia, Z., Wu, R. & Cheng, Y. Life cycle carbon footprint of electric vehicles in different countries: a review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 301, 122063 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Skerlos, S., Xu, M. & Cooper, D. R. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from US light-duty transport in line with the 2 °C target. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9326–9338 (2021).

Xia, X. & Li, P. A review of the life cycle assessment of electric vehicles: considering the influence of batteries. Sci. Total Environ. 814, 152870 (2022).

Shafique, M., Azam, A., Rafiq, M. & Luo, X. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles and internal combustion engine vehicles: a case study of Hong Kong. Res. Transp. Econ. 91, 101112 (2022).

Safarian, S. Environmental and energy impacts of battery electric and conventional vehicles: a study in Sweden under recycling scenarios. Fuel Commun. 14, 100083 (2023).

Franzò, S. & Nasca, A. The environmental impact of electric vehicles: a novel life cycle-based evaluation framework and its applications to multi-country scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 315, 128005 (2021).

Winkler, S. et al. Vehicle criteria pollutant (PM, NOx, CO, HCs) emissions: How low should we go? NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 1–5 (2018).

Shen, W., Han, W. & Wallington, T. J. Current and future greenhouse gas emissions associated with electricity generation in China: implications for electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7069–7075 (2014).

Shen, W., Han, W., Wallington, T. J. & Winkler, S. L. China electricity generation greenhouse gas emission intensity in 2030: implications for electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6063–6072 (2019).

Requia, W. J., Adams, M. D., Arain, A., Koutrakis, P. & Ferguson, M. Carbon dioxide emissions of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles: a life-cycle analysis in eight Canadian cities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 78, 1390–1396 (2017).

Shang, H., Sun, Y., Huang, D. & Meng, F. Life cycle assessment of atmospheric environmental impact on the large-scale promotion of electric vehicles in China. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 15, 100148 (2024).

Qu, S., Liang, S. & Xu, M. J. E. S. CO2 emissions embodied in interprovincial electricity transmissions in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 10893–10902 (2017). & technology.

Moro, A. & Lonza, L. Electricity carbon intensity in European Member States: Impacts on GHG emissions of electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 64, 5–14 (2018).

Yi, B. W., Zhang, S. & Wang, Y. Estimating air pollution and health loss embodied in electricity transfers: an inter-provincial analysis in China. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134705 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. Assessing electric vehicle policy with region-specific carbon footprints. Appl. Energy 256, 113923 (2019).

Huo, H., Zhang, Q., Liu, F. & He, K. Climate and environmental effects of electric vehicles versus compressed natural gas vehicles in China: a life-cycle analysis at provincial level. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 1711–1718 (2013).

Kallitsis, E. et al. Environmental life cycle assessment of the production in China of lithium-ion batteries with nickel-cobalt-manganese cathodes utilising novel electrode chemistries. J. Clean. Prod. 254, 120067 (2020).

He, G. et al. Rapid cost decrease of renewables and storage accelerates the decarbonization of China’s power system. Nat. Commun. 11, 1 (2020).

Raugei, M., Morrey, D., Hutchinson, A. & Winfield, P. A coherent life cycle assessment of a range of lightweighting strategies for compact vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 108, 1168–1176 (2015).

Luk, J. M., Kim, H. C., De Kleine, R., Wallington, T. J. & MacLean, H. L. Review of the fuel saving, life cycle GHG emission, and ownership cost impacts of lightweighting vehicles with different powertrains. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 8215–8228 (2017).

Zhai, M., Huang, G., Liu, L., Zheng, B. & Guan, Y. Inter-regional carbon flows embodied in electricity transmission: network simulation for energy-carbon nexus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 118, 109511 (2020).

Li, W. et al. Inter-provincial emissions transfer embodied in electric vehicles in China. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 119, 103756 (2023).

Li, W. et al. How the uptake of electric vehicles in China leads to emissions transfer: an Analysis from the perspective of inter-provincial electricity trading. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 28, 1006–1017 (2021).

Qiao, Q., Zhao, F., Liu, Z., He, X. & Hao, H. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of electric vehicles in China: combining the vehicle cycle and fuel cycle. Energy 177, 222–233 (2019).

Burnham, A. Updated vehicle specifications in the GREET vehicle-cycle model. Argonne National Laboratory (2012).

Qiao, Q., Zhao, F., Liu, Z., Jiang, S. & Hao, H. Cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas emissions of battery electric and internal combustion engine vehicles in China. Appl. Energy 204, 1399–1411 (2017).

Wu, Y. & Zhang, L. Can the development of electric vehicles reduce the emission of air pollutants and greenhouse gases in developing countries? Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 51, 129–145 (2017).

Laboratory, A. N. The Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation Model, https://greet.es.anl.gov/greet.models (2023).

Keoleian, G., Miller, S., De Kleine, R., Fang, A. & Mosley, J. Life cycle material data update for GREET model. Report No. CSS12-12 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. Life cycle water use of gasoline and electric light-duty vehicles in China. Resour., Conserv. Recycling 154, 104628 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Life cycle environmental assessment of electric and internal combustion engine vehicles in China. J. Clean. Prod. 285, 124899 (2021).

Sullivan, J. L., Burnham, A. & Wang, M. Q. Model for the part manufacturing and vehicle assembly component of the vehicle life cycle inventory. J. Ind. Ecol. 17, 143–153 (2013).

Song, H., Ou, X., Yuan, J., Yu, M. & Wang, C. Energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions of diesel/LNG heavy-duty vehicle fleets in China based on a bottom-up model analysis. Energy 140, 966–978 (2017).

Wei, F., Walls, W., Zheng, X. & Li, G. Evaluating environmental benefits from driving electric vehicles: the case of Shanghai, China. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 119, 103749 (2023).

Shi, S., Zhang, H., Yang, W., Zhang, Q. & Wang, X. A life-cycle assessment of battery electric and internal combustion engine vehicles: a case in Hebei Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 228, 606–618 (2019).

Li, J. & Yang, B. J. A. P. R. Analysis of greenhouse gas emissions from electric vehicle considering electric energy structure, climate and power economy of EV: a China case. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 11, 1–11 (2020).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook (China Statistics Press, Beijing, 2021).

Qu, S. et al. A Quasi-Input-Output model to improve the estimation of emission factors for purchased electricity from interconnected grids. Appl. Energy 200, 249–259 (2017).

China Power Yearbook Editorial Board. China Electric Power Yearbook. (China Statistics Press, Beijing, 2021).

China Electricity Council. Annual Development Report of China’s Electric Power Industry. (China Market Press, Beijing, 2021).

China Electricity Council. Compilation of Statistical Data of Power Industry. (China Electric Power Press, Beijing, 2021).

China Association of Automobile Manufacturers and China Automotive Technology and Research Center. China Automobile Industry Yearbook (China Automotive Industry Association Press, Beijing, 2021).

Hu, D., Zhou, K., Hu, R. & Yang, J. Regional inequalities in life cycle environmental impacts of transportation electrification in China. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9XMRE (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 72242103 and 72188101), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. JZ2022HGPB0305).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. H. and K. Z. designed the study and performed the analysis. D. H. wrote the draft, and plotted all figures. K. Z. supervised this study and revised this paper. R. H. and J. Y. helped the results interpretation in part. All co-authors reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Xiaoning Xia and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet, Heike Langenberg [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, D., Zhou, K., Hu, R. et al. Provincial inequalities in life cycle carbon dioxide emissions and air pollutants from electric vehicles in China. Commun Earth Environ 5, 726 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01906-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01906-6