Abstract

Plastic pollution transported in rivers remains poorly understood due to the diversity of shapes, sizes, and densities of plastics, as well as their complex interactions with biofilms. While previous studies have explored the settling velocities of plastics and their interactions with biofilms, they often overlook how biofouling alters plastic dynamics and settling behaviour. To address this, over 800 settling experiments were conducted to demonstrate that the dynamics and falling velocities of isotropic (spheres) and anisotropic (square and rectangle plates) macroplastics of different densities (1050 to 2200 kg/m3) are significantly impacted by biofouling. Three-dimensional tracking of plastic trajectories revealed that biofilm colonisation on the surface of anisotropic plastic plates triggered them to exhibit more chaotic trajectories, larger horizontal dispersion and higher oscillatory frequencies. These dynamics reduced the average vertical settling velocity of anisotropic biofouled plates by up to 12%—despite greater plastic densities and considering the multimodal distribution of a plate’s fall velocity—compared to their pristine counterparts. Results highlight the necessity of accounting for the intricate multimodal settling dynamics of plastics, including their interactions with biofilms, to provide more reliable predictions of plastic transport and fate in aquatic environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastic is overflowing in rivers, endangering biodiversity, food security and freshwater resources1,2,3. However, our current understanding of how plastic pollution is transported in the riverine environment is not well understood4. This is due to the spatial and temporal variability of turbulent flows in rivers, along with the diverse physical properties of plastic pollution—such as differences in shape, density, size, and age—and the interactions between plastics, sediments, and biota, which can alter a plastic’s physical characteristics5,6,7. These dynamic physical characteristics of plastic pollution complicate the description of plastic transport8. A lack of this knowledge limits our ability to conduct reliable plastic monitoring campaigns in rivers to accurately quantify plastic budgets and to identify pollution hotspots7. This hinders the implementation of effective environmental policies to prevent plastics from entering aquatic systems and the execution of efficient plastic clean-up strategies.

The vertical settling (or rising) velocity of a plastic particle (\(w\)) is a key parameter in describing its transport in rivers9,10,11. This parameter characterises how piece of plastic is vertically transported through a fluid under gravitational, buoyancy, lift and drag forces, and is dependent on the plastic’s physical properties such as density, size and shape12,13,14. Recent research has shown that turbulent transport models designed for natural sediments, such as the Rouse profile15, can describe the vertical profile of suspended plastics and predict their concentrations in rivers with an uncertainty of within ±10%7,8,16. These models are derived from the ratio of the river’s shear velocity to the plastic’s settling velocity, which can be variable over time and with differing plastic physical properties12,15. If the probability density function of a plastics’ settling velocity is known, as well as the river’s hydrodynamics, turbulent transport models can be used to quantify plastic concentration in the river water column from a single sampling point at a given depth17.

When plastic enters the aquatic environment, their stable and durable surface is a good medium for attachment and colonisation of microorganisms18,19. The success of colonisation by microorganisms on a plastic particle is partially determined by the plastic’s hydrophilicity, which facilitates the adsorption of organic material onto the surface of the plastic, and surface roughness, which enhances microbial attachment and rate of colonisation20. These factors are dependent on the type of plastic polymer and are dynamic with the amount of time the plastic has been exposed to the environment, which leads to changes in the hydrophilicity and surface roughness of a plastic5,21.

Once attached to the plastic’s surface, microorganisms can secrete a sticky extracellular polymeric substance (e.g. EPS) that promotes the formation of biofilms, which are successive accumulations of organic matter and microorganisms on the plastic’s surface and within the plastic’s structure22. EPS also promotes the attachment of sediments and other pollutants, such as heavy metals on the plastic to form an aggregate23,24. This accumulation of biofilms on a piece of plastic can alter its physical and material properties in terms of size, density, mass distribution, surface roughness and hydrophilicity, which leads to changes in how the biofouled plastic behaves in a river environment when compared to the equivalent pristine plastic18,25,26. For example, biofouling has been observed to increase the vertical settling velocity of negatively buoyant fibres27 and fragments28,29. However, negligible changes in vertical settling velocity were observed for anisotropic square plastic plates, due to greater horizontal oscillatory amplitudes of the settling biofouled plastic27.

To date, several studies have quantified the settling velocity for pristine and biofouled microplastics (plastics ≤5 mm in size) and macroplastics (plastics ≥5 mm in size) for a range of material densities and shapes8,9,10. Measurements of settling velocities are usually derived from quiescent settling experiments of solitary plastics, where the settling velocity is determined as a monomodal average based on a number of repeat tests. However, recent research has shown that the vertical transport of anisotropic pristine plastics can be more accurately described by a statistical multimodal function, rather than a singular average value8. This multimodality is due to the plastic’s shape, mass distribution and geometric anisotropy, which drives the plastic’s dynamics into stable and metastable settling orientations during its vertical descent, with observed velocities varying three-fold for the same plastic particle8. Therefore, characterising the diversity of a plastic’s settling behaviour in quiescent conditions is crucial for understanding plastic transport in turbulent river-like flows, where turbulent structures and shear forces in unsteady flows can alter a plastic’s orientation leading to significant uncertainties if a single settling velocity value is assumed.

The dynamics and statistical distributions of the vertical settling velocity of geometrically-anisotropic particles have been characterised for two-dimensional disks13,30,31, rectangular plates32,33,34 and three-dimensional cylinders35,36,37, but not in the context of describing plastic pollution transport in rivers. The dynamical settling behaviour of different geometrical shapes, especially flat two-dimensional plates, can be described by seven-dimensional parameters: the maximum (\({L}_{1}\)), intermediate (\({L}_{2}\)) and smallest (\({L}_{3}\)) dimensions of the plate, density of the plate (\({\rho }_{p}\)), density of the fluid (\({\rho }_{w}\)), kinematic viscosity of the fluid (\(v\)), and the ensembled average vertical settling velocity of a particle (\(\bar{w}\)). These parameters can be used to determine two dimensionless parameters which characterise the settling behaviour of two-dimensional plates: the particle Reynolds number \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}=\bar{w}{L}_{1}/v\) that represents the ratio of inertial to viscous forces, as well as the flow regime over a particle, and dimensionless moment of inertia \({I}_{* }\) = \(\frac{8\varepsilon \beta (1+{\beta }^{2})}{3\pi }\), which accounts for a plate’s resistance to rotational motion in a fluid, where \(\varepsilon ={\rho }_{p}/{\rho }_{w}\) is the density ratio and \(\beta ={L}_{1}/{L}_{3}\) is the plate’s thickness-to-width ratio38. A \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) – \({I}_{* }\) phase diagram can be used to describe the dynamics and settling patterns of individual plates39. For two-dimensional plates, when \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) < 100, plates descend steadily without horizontal motions, and transition to an oscillatory settling motion when \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) > 100. A chaotic, tumbling regime was also observed when \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) > 100 and \({I}_{* }\) > 0.239, whereas others have found the transition value to be at \({I}_{* }\) = 0.440. A qualitatively similar \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) – \({I}_{* }\) phase diagram for circular two-dimensional disks has also been described30,31.

To our knowledge, only one study to date has described the dynamics of two-dimensional microplastic pollution particles (where \({L}_{1}\) is in the range 1.5–5 mm) in quiescent conditions and the resulting effect on a particle’s vertical settling velocity41. However, this study did not investigate the three-dimensional trajectories of plastics, which is required to inform a complete description of the particle’s lateral (\(x\) and \(y\) directions) and vertical (\(z\) direction) motion, that is not captured by using two-dimensional particle tracking systems, leading to a gap in the characterisation of plastic pollution motion. This study also did not examine plastics that were colonised with biofilms, which may influence the dynamical behaviour of the settling plates. Previous studies have shown that two-dimensional plates, with a gravity centre that was shifted by less than 1 % of their width, can change a plate’s settling behaviour and vertical velocities42. Given that the heterogenous colonisation of biofilms may cause changes in a plate’s mass distribution and the relocation of the plate’s gravity centre, the impact of biofouling on a plastic plate’s vertical transport needs to be investigated.

The aim of this study is to characterise and compare the three-dimensional settling dynamics of pristine and biofouled isotropic (spheres) and anisotropic (rectangular and square plates) plastics (PS, POM, PTFE), with densities ranging from 1050 to 2200 kg/m³, to describe their settling behaviour and vertical and horizontal velocity distributions. This is achieved by (i) recording and reconstructing the three-dimensional settling dynamics of the pristine and biofouled plastics by a tracking and reconstruction algorithm, (ii) characterising their modes of vertical transport, (iii) comparing their lateral dispersion, oscillatory frequencies and amplitude, and (iv) calculating their settling velocity probability distribution function. Describing these dynamics enables the evaluation of the impact of plastic’s geometric shape and the uneven mass distribution caused by biofouling on plastic behaviour and vertical transport.

Results and discussion

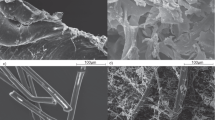

Changes to plastic properties due to biofouling

Biofouling changed the material and surface properties of anisotropic rectangular (20\(\times\)10\(\times\)1 mm3), square (10\(\times\)10\(\times\)1 mm3) and isotropic spherical (\(d\) = 5 mm) macroplastics employed in this experiment, that were composed of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), polyoxymethylene (POM) and polystyrene (PS) polymers (see Methods for full description of plastics and biofouling procedures). Figure 1A displays images of both pristine and biofouled plastics stained with crystal violet dye to highlight areas that were colonised by biofilms, while Fig. 1B–D presents boxplots that quantify the changes in plastic density (Fig. 1B–D), biofilm area coverage (Fig. 1E), spatial variation of biofilm growth (Fig. 1F), as well as changes in surface contact angle (Fig. 1G) and areal surface roughness (\({Sa}\)) (Fig. 1H).

A Images of pristine and biofouled rectangle, square and spherical plastics employed in experiments, stained with crystal violet to highlight areas of biofouling. PS biofouled spherical plastics could not be stained with crystal violet as plastics were red in colour. Boxplots detailing differences in material and surface properties of biofouled and pristine plastics used in experiments, considering a repeat of 10 samples, in terms of B–D plastic density, E biofilm area coverage, F biofilm spatial variation, G contact angle, and H areal surface roughness. Biofilm area coverage and spatial variation for PS spherical plastics could not be measured because of their red colour. The contact angle for spherical plastics could not be measured due to their shape. Statistical significances between plastics are derived from \(p\)-values from a non-parametric Mann–Whitney \(U\) test (\(N\) = 10 for both groups).

Biofouling significantly increased density for the majority of plastics (Fig. 1B–D) (Mann–Whitney \(U\) test: \(p\) < 0.05), except for PTFE rectangular plates, although an overall increase was still observed (see Supplementary Table 1 for specific values and statistical significance for each material property). Of the tested polymers, PS biofouled plastics (considering rectangular, square, and spherical plastics) had the largest increase in density (2.2% on average) and the greatest biofilm area coverage (72.2% on average) (Fig. 1E), indicating that PS plastics promoted the most biofilm colonisation. Conversely, POM and PTFE biofouled plastics experienced average density increases of 1.5% and 1.1%, respectively. Of the different shapes tested, spheres had the most biofilm coverage on their surface, with averages between 98–100% coverage for all polymers, compared to rectangles (22–88%) and square plates (9–44%), due to the sphere’s smaller surface area available to promote biofilm growth.

Using a photogrammetry technique to analyse surface biofilm spatial variation (described in Methods), all biofouled plastics had a value larger than zero (Fig. 1F), indicating heterogeneous growth of biofilms over the plastics’ surface, resulting in areas of the plastic’s surface with varying biofilm thickness and density. PS plastics had the largest spatial variation of biofouling of the polymers used, due to the greater biofilm growth on the plastic’s surfaces (Fig. 1F). A higher biofilm spatial variation may cause larger biofilm loading on one side of the plastic, resulting in an offset of the plastic’s gravity centre42.

Biofouling also caused the contact angle, which is a measure of a plastic’s hydrophilic polarity, to significantly decrease for all plastics (Fig. 1G), (Mann–Whitney \(U\) test: \(p\) < 0.05), meaning all plastics became more hydrophilic (i.e., their contact angle decreased) with biofilm colonisation. Biofouled plastics had average contact angles between 30–70°, which is similar to results for other biofouled microplastics43,44. The greatest decrease in contact angle between pristine and biofouled plastics was observed for POM plastics (37% considering both rectangle and square plates) compared to PS (31%) and PTFE (20%). Biofouling also significantly increased the plastic’s surface roughness (Fig. 1H) (Mann–Whitney \(U\) test: \(p\) < 0.05). PS plastics had the greatest average increase in areal surface roughness (221%), while POM (95%) and PTFE (93%) had lower increases in surface roughness due to less biofilm growth.

The greater biofilm growth exhibited on the PS plastics may be attributed to PS having a greater hydrophilic polarity (Fig. 1). Plastics that are more hydrophilic allow for easier adsorption of organic material, which provides a ‘conditioning film’, which facilitates the colonisation of bacteria and microorganisms on the plastic’s surface18,20. The surface roughness can also enhance microbial attachment and accelerate colonisation45. However, in our analysis, pristine PS plastics, despite being the smoothest in terms of areal surface roughness among the plastics tested, exhibited the greatest hydrophilicity and promoted the most biofilm colonisation (Fig. 1E). This may indicate that hydrophilicity is potentially a more influential factor in biofilm colonisation than surface roughness for the plastics tested in this study.

Characterisation of settling dynamics

Both pristine and biofouled plastics were released into the settling tank one by one, and their trajectories were tracked and recorded. Figure 2 presents three-dimensional reconstructions of typical pristine and biofouled plastic trajectories for rectangular plates (Fig. 2A–G), square plates (Fig. 2H–K), and spherical plastics (Fig. 2L) (see Supplementary Movie 1 for animations of each trajectory). Their instantaneous vertical velocities (\({w}_{i}\)) are shown in a colour scale to highlight variations in vertical velocity during the plastic’s motion. Three different release positions were used to capture the full variability of settling dynamics for the anisotropic rectangular and square plates (Fig. 2M), which correspond to a forced slow orientation (position 1), forced fast orientation (position 2) and a transitional orientation (position 3), where plastics were equally susceptible of evolving into either fast or slow orientations of transport (full description of experimental setup and plate release conditions provided in Methods).

Vertical trajectories were observed for rectangular (A–G), square (H-K) and spherical (L) plastics, with their instantaneous vertical velocities (\({w}_{i}\)) shown in a colour scale. A–C and H–J Rectangular and square plates settling in an oscillating mode 1 type of settling. D A PTFE plate settling in a fast mode 2 type of trajectory. E, K PTFE rectangular and POM square plates travelling initially in mode 2 and transitioning to mode 1. F, G Biofouled PTFE plates settling in a mode 3 chaotic type of trajectory. L A PTFE spherical plastic settling in a straight vertical trajectory. M Diagrams of the three different release positions adopted to release the anisotropic plastics into the settling tank at a distance of 2 cm below the water surface. Animations of each trajectory are available in Supplementary Movie 1.

Through visual observation of the plastic’s dynamics and trajectories, the pristine and biofouled rectangular and square plates settled in distinct orientations, which affected their vertical transport, resulting in a settling velocity distribution that is multimodal for all anisotropic plates. Hence, a characterisation of each mode of transport is required to determine a suitable settling probability distribution function for each plastic. Three main modes of transport are observed for the anisotropic plates, which contrasts with the isotropic spherical plastics where only one settling orientation was observed (Fig. 2L), resulting in a settling velocity distribution that is monomodal. For the anisotropic plates, the three observed modes of vertical transport correspond to:

-

Mode 1, where plates settled in a slow, stable oscillating motion, with plastics oscillating in regular and repeatable periods. Plates were observed to oscillate in the horizontal plane with their largest exposed area normal to the vertical line of motion. Examples of this type of trajectory are provided in Fig. 2A–C for pristine rectangular PTFE, POM and PS plates and in Fig. 2H–J for pristine square PTFE, POM and PS plates.

-

Mode 2, where plates settled in an orientation that promoted a fast vertical velocity, with their longest dimension (\({L}_{1}\)) parallel to the vertical line of motion. Examples of this type of trajectory are shown in Fig. 2D for a pristine rectangular PTFE plate settling in mode 2 for the entirety of the settling distance, while Fig. 2E, K provide an example of a PTFE rectangular and POM square plates initially travelling in mode 2 and transitioning into mode 1.

-

Mode 3, where plates settled in an unsteady, chaotic motion, with plates alternating between a gliding motion with a low angle of attack (at approximately 45°) and rapid changes in plate orientation and horizontal direction. This is distinctly different from modes 1 and 2, as motion is unpredictable with irregular, non-repeatable periods. Examples of this type of trajectory are shown in Fig. 2F, G for a biofouled PTFE plate.

Table 1 presents the percentage of the anisotropic plates settling for each mode of transport, at a vertical depth (\(z\)) of \(z\) = 5 cm (initial) and \(z\) = 20 cm (end) to indicate the probability of plates settling in each mode at different vertical depths.

Mode 1 (slow) dynamics

Mode 1 was the most common mode of transport for all pristine and biofouled anisotropic plates at the initial and end positions of the settling trajectory (Table 1). All anisotropic plates featured a mode 1 type of settling, which is consistent with the oscillatory phase of the \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\)–\({I}_{* }\) diagram (\({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) > 100, \({I}_{* }\) < 0.2), as defined by Smith (1971) and presented in Fig. 3. \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) and \({I}_{* }\) values are reported in Supplementary Table 2.

Phase diagram for square and rectangular plastic plates as a function of the particle Reynolds number \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) and dimensionless moment of inertia \({I}_{* }\). Dashed lines denote the boundaries between different plastic dynamics, which correspond to stable, oscillatory and chaotic trajectories, as proposed by Smith (1971).

For square plates, regardless of biofouling, 57–97% settled in mode 1 at the initial position (\(z\) = 5 cm), and by the final position (\(z\) = 20 cm), nearly all had transitioned to mode 1 (98–100%) (Table 1). In contrast, rectangular plates were less frequently observed in mode 1 at the initial position (\(z\) = \(5\) cm), with only 56–75% in this mode. This indicated that rectangular plates were more often observed in modes 2 and 3 compared to square plates at the initial settling stages after their release. However, by the end position (\(z\) = 20 cm), the majority of rectangular plates had transitioned to mode 1 (82–99%). Once plates transitioned into mode 1, from either mode 2 or mode 3, they remained stable in mode 1 and did not transition into any other mode of transport. This is because wake-induced permutations from the settling plastic were not large enough to cause a change in the plate’s orientation once they had transitioned to mode 18,38.

Mode 1 oscillatory horizontal drift

Anisotropic plastic plates settling in mode 1 drifted in the horizontal plane from their initial release point during their downward transport. Figure 4 shows all trajectories of biofouled and pristine anisotropic plates in mode 1 type of transport from the \(x{{\rm{\hbox{-}}}}y\) plane, together with histograms of the horizontal drift for each plate, calculated by differences between the release (\(z\) = 0 cm) and end points (\(z\) = 20 cm) radial distance coordinates (\(r=\sqrt{{x}_{p}^{2}+{y}_{p}^{2}}\)), where \({x}_{p}\) and \({y}_{p}\) represent the plate’s position in the \(x\) and \(y\) direction.

Trajectories and histograms of the horizontal drift for each anisotropic plate from the x–y plane, calculated by differences between the release point (\(z\) = 0 cm) and end (\(z\) = 20 cm) radial distance coordinates (\(r\)) for rectangular (A, B) and square (C, D) plates. Biofouled plate trajectories are shown in green, while pristine plate trajectories are shown in grey. Histograms represent the horizontal drift of all the trajectories, while vertical lines represent the average horizontal drift for both pristine and biofouled plates.

Results show that horizontal drift for biofouled rectangular and square PTFE and PS plates settling mode 1 are, on average, between 15–127% larger than pristine plates (Mann–Whitney \(U\) test: \(p\) < 0.05) (see Supplementary Table 3 for the average horizontal drift for each plate and statistical significances). No significant differences are observed between pristine and biofouled rectangular and square POM plates, however, average horizontal drift still increased by between 8–14%. For biofouled PS plates, horizontal dispersion was up to twice as large compared to their pristine equivalent, indicating significant horizontal displacements over a large vertical distance when settling in quiescent conditions (Fig. 4).

The driver for the differences in horizontal drift between the pristine and biofouled plates is the heterogeneous colonisation of biofilms on the surface of the anisotropic plastic plates, which shifts the plate’s gravity centre due to the unbalanced mass loading (Fig. 1A). The heterogeneous mass distribution caused settling plates to transition from a symmetric oscillation to an asymmetric pattern, hence inducing the plate to drift laterally every oscillatory period42. This causes the plate to move laterally away from the initial release position (see Supplementary Movie 2 for example trajectories).

The enhanced dispersion observed by the PS square and rectangular plates (Fig. 4) may be attributed to their greater level of biofilm colonisation (Fig. 1), which may lead to a greater mass imbalance and a shift in the plate’s centre of gravity, causing larger asymmetric oscillation amplitudes compared to the other plastics tested. These findings are consistent to controlled asymmetric mass distributed rectangular plates settling in an oscillatory motion (\({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}} \sim 1500,{I}_{* } \sim 0.13\)), which showed that plates with a centre of gravity that was shifted by less than 1 % of their width can cause large horizontal drift, with a settling displacement of 20 cm over a vertical distance of 35 cm42.

Mode 1 oscillatory characteristics

As plates settling in mode 1 showed a sinusoidal oscillatory pattern (Fig. 2A–C and Fig. 2H–J) their oscillatory amplitude (\(\alpha\)) and frequency (\(f\)) can be characterised, as well as the Strouhal number (\({St}\) = \(fd/w\)) to be calculated. The Strouhal number describes the ratio between the frequency of oscillation, relative to the plate’s size and the settling velocity, where \(d\) is the characteristic length of the plate, taken as the intermediate dimension (\({d=L}_{2}\)), in which plates oscillate against. Figure 5 shows the Fast Fourier Transform of the radial position (\(r\)) time series for all pristine and biofouled anisotropic plastics while travelling in mode 1, with the ensembled average spectra shown in a bold colour. Supplementary Table 4 presents the average oscillatory characteristics in terms of oscillatory amplitude \(\alpha\) and frequency \(f\), based on the energetic spectral peak, and Strouhal number \({St}\) for all plates.

Anisotropic plates had different oscillatory characteristics, depending on their physical properties (Fig. 5). Regardless of biofilm colonisation, the Strouhal number tends to decrease with \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\), while oscillation amplitude increases with \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2 for comparisons between \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\), the Strouhal number and oscillation amplitude). This is attributed to a reduction in viscous drag forces acting on the plate with increasing \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) leading to the plate’s horizontal motion to become more prominent compared to the plate’s vertical settling velocity, as oscillation amplitude and frequency increase. For rectangular plates, PTFE plastics present spectra with a singular distinct peak, while those from POM and PS have two distinct peaks for both biofouled and pristine plates (Fig. 5). The appearance of two peaks may be due to plates not always oscillating in the same transversal direction, similar to findings for microplastic plates41 and disks31, for comparable \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) and \({I}_{* }\) values. For square plates, spectra from PTFE plastics show a broad singular peak, while POM and PS plates spectra show a distinct singular peak (Fig. 5).

Differences between the mode 1 oscillatory characteristics between pristine and biofouled anisotropic plates are also observed with some statistical significance (Mann–Whitney \(U\) test: \(p\) < 0.05) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 4). Biofouling increased oscillatory amplitude, frequencies and Strouhal numbers for the majority of plates (except PS rectangular plates due to the appearance of two peaks), relative to the pristine plates (Fig. 5). For instance, biofouling increased oscillatory amplitude for PTFE and POM rectangular plates by between 1–14% on average, and oscillatory frequencies by between 6–10% on average (Supplementary Table 4). The differences in oscillatory characteristics between the biofouled and pristine plates are attributed to the heterogeneous mass distribution of the biofouled plates and their asymmetrical settling pattern (see Section 2.4 Mode 1 oscillatory horizontal drift). Asymmetrical settling motion can result in plates having larger oscillatory frequencies and amplitudes, as the plate drifts laterally after each oscillatory period (see Supplementary Movie 2 for example trajectories)42.

Mode 2 (fast) dynamics

The fast mode 2 was the second most commonly observed settling mode (Table 1). Plates that were released into the settling tank in positions 2 (forced fast orientation) or 3 (transitional orientation) (Fig. 2M) either settled in a mode 2 type trajectory for the entirety of the recorded settling distance (Fig. 2D) or, more frequently, travelled in mode 2 for a certain distance before transitioning into the stable mode 1 orientation (Fig. 2E, K). At the initial position (\(z\) = 5 cm), approximately 30% of rectangular plates settled in mode 2, while by the end of the measured window (\(z\) = 20 cm), the majority of plates had transitioned to mode 1 (Table 1). Similarly, for square plates, at \(z\) = 20 cm, almost all plates settling in fast mode 2 at the initial position eventually transitioned to slow mode 1. Negligible differences in plastic dynamics were observed between pristine and biofouled rectangular and square plates travelling in mode 2. Anisotropic plates settling in fast mode 2 typically become unstable during vertical descent as a result of uneven pressure distribution over their surface, e.g. caused by a non-laminar wake downstream of the plate. This changes a plate’s orientation and hence its angle of descent, which accelerates the plate’s transition from the fast mode 2 to the slow oscillating mode 1 of transport.

Mode 3 (chaotic) dynamics

Mode 3 is characterised as a chaotic motion, similar to the regime described for plates when \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) > 100 and \({I}_{* }\) > 0.2 (Fig. 3)33,39. Mode 3 was only observed for the PTFE rectangle plates when released in positions 2 and 3 (Fig. 2M) and was enhanced by biofouling (Table 1). For instance, 12% of biofouled PTFE rectangular plastics settled in a mode 3 type of trajectory compared to only 1% of pristine PTFE rectangular plastics (Table 1). The heterogeneous mass distribution of biofouled plates increases the susceptibility of plastics to be destabilised and to exhibit a chaotic settling pattern. PTFE rectangular plates exhibited the largest \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) of all the plastics tested in experiments (Supplementary Table 2), which relates to a more unsteady plastic wake dynamics that induce uneven pressure distribution over the plastic. Hence, any slight change in the plate’s gravity centre enhanced the likelihood of the plate not finding an equilibrium settling state to settle in mode 1 or 2, causing the plate to settle in a chaotic trajectory, i.e. mode 3.

Mode 3 was not observed for square plates, although these were closer to the chaotic \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) – \({I}_{* }\) regime of transport (Fig. 3). Considering the moment of inertia \(I\) of a rectangular plate shape scales with the cube of the longest planer dimension (\({L}_{1}\)) and linearly with the shortest planer dimension (\({L}_{2}\)), i.e. \(I\) = \({L}_{2}{L}_{1}^{3}/12\), any small change in mass distribution away from the centre of mass over \({L}_{1}\) direction can trigger large differences in its vertical transport. This may make the rectangular plates more prone to tipping compared to square plates employed in this experiment due to the latter having a lower moment of inertia and more evenly distribution of mass across its main \({L}_{1}\) and \({L}_{2}\) dimensions, making square plates more stable while settling.

Average vertical and horizontal velocities of biofouled plastics

To determine the impact different settling dynamics have on the vertical and horizontal settling velocities of plates, Fig. 6A–C presents all the instantaneous vertical (\({w}_{i}\)) velocities of biofouled (coloured green) and pristine (coloured grey) rectangular plates, against the vertical distance travelled from the point of release at z = 0 cm. Figure 7A–C is analogous to Fig. 6A–C but for square plates. The probability distributions of the vertical settling velocities for each mode of transport (modes 1, 2 and 3) are presented in Fig. 6D–F for rectangle plates and Fig. 7D–F, for square plates, omitting periods of transition between the different modes of vertical transport. Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 present the instantaneous horizontal velocities (\({V}_{i}\)) and their probability distributions for each mode of transport. Table 2 summarises the ensembled average vertical \((\bar{w})\) and absolute horizontal (\(\bar{V}\)) velocities of all plastics, between a vertical distance 5–20 cm, as well as average transport mode velocities in for plastics settling in mode 1 (\({\bar{w}}_{m1},{\bar{V}}_{m1}\)), mode 2 (\({\bar{w}}_{m2},{\bar{V}}_{m2}\)) and mode 3 (\({\bar{w}}_{m3},{\bar{V}}_{m3}\)).

A–C The instantaneous vertical velocity of all biofouled and pristine rectangular plastics against the vertical distance travelled, considering 90 repeat tests. Biofouled plates are shown in shades of green, while pristine plates are shown in shades of grey. Solid vertical lines represent the calculated average vertical (\(\bar{w}\)) velocity of biofouled and pristine rectangular plates, while dashed and dotted vertical lines represent the calculated average vertical velocity of plastics settling in mode 1 (\({\bar{w}}_{m1}\)), mode 2 (\({\bar{w}}_{m2}\)) and mode 3 (\({\bar{w}}_{m3}\)), taken between a vertical depth of 5–20 cm. Transition periods were ignored during calculations of \({\bar{w}}_{m1}\), \({\bar{w}}_{m2}\), \({\bar{w}}_{m3}\). D–F Probability distribution functions of plastic settling velocity the various modes of vertical transport (modes 1, 2 or 3) for both pristine and biofouled plastics. Periods, where the plates were in transition between modes, were omitted from probability distribution functions.

A–C The instantaneous vertical velocity of all biofouled and pristine square plates against the vertical distance travelled, considering 90 repeat tests. Biofouled plates are shown in shades of green, while pristine plates are shown in shades of grey. Solid vertical lines represent the calculated average vertical (\(\bar{w}\)) velocity of biofouled and pristine rectangular plates, while dashed and dotted vertical lines represent the calculated average vertical velocity of plastics settling in mode 1 (\({\bar{w}}_{m1}\)), mode 2 (\({\bar{w}}_{m2}\)) and mode 3 (\({\bar{w}}_{m3}\)), taken between a vertical depth of 5–20 cm. Transition periods were ignored during calculations of \({\bar{w}}_{m1}\), \({\bar{w}}_{m2}\), \({\bar{w}}_{m3}\). D–F Probability distribution functions of plastic settling velocity the various modes of vertical transport (modes 1, 2 or 3) for both pristine and biofouled plastics. Periods where the plates were in transition between modes were also omitted from probability distribution functions.

Results of vertical velocities for anisotropic plates indicate these are multimodal and the vertical settling velocity of a plastic is largely dependent on its settling mode (modes 1, 2 or 3), shape and biofilm growth (Figs. 6–7 and Table 2). The effect of surface roughness caused by biofouling on the settling velocity of plastics is negligible for plastics examined in these experiments, with particle Reynolds numbers \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) between 200–1800 and areal surface roughness (Sa) to particle thickness (L_3) ratios (\({Sa}/{L}_{3}\)) between 0.1–0.13, because the flow regime is deemed to be laminar over the plastic surface, resulting in a thin boundary layer where small roughness elements do not largely impact the flow field (similar conclusions were made for settling disks with Reynolds numbers \({{\rm{R}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) between 230–10,000 and \({Sa}/{L}_{3}\) between 0.08–0.1946).

Anisotropic plates settling in mode 1 had the slowest vertical settling velocity as they settled in an orientation with their largest exposed projected area normal to the vertical line of motion (Fig. 2A–C), which led to larger drag forces (Supplementary Fig. 5 outlines changes in the estimated drag coefficient depending on settling orientation). For plates settling in mode 1, larger horizontal velocities are observed compared to vertical velocities, as the plate oscillates rapidly from side to side while settling (Table 2). Plates that settled in mode 2 had a reduced projected area (Fig. 2D, E), resulting in lower drag forces and faster vertical settling velocities compared to mode 1 (Figs. 6–7 and Table 2). Plates settling in mode 2 have faster vertical velocities relative to their horizontal velocities, as the plates descend in a relatively straight vertical trajectory with negligible lateral motion.

Anisotropic plates settling in the chaotic mode 3 (only observed for PTFE rectangle plates) had an orientation that changed greatly over the settling distance (Fig. 2F, G). The most frequent orientation for plates in mode 3 was a transitional orientation between modes 1 and 2, with a projected area that resembled an angled gliding motion of the plate at approximately 45° (Fig. 2F, G). As a result, the average settling velocity for plates in mode 3 was between the slower mode 1 and the faster mode 2 of transport (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Mode 3 featured the highest horizontal velocities of all the modes observed due to the rapid changes in direction and orientation during vertical transport.

Spherical plastics exhibited the fastest average vertical settling velocities of all the plastics tested (Table 2), attributed to their reduced projected area and smaller drag forces (Supplementary Fig. 5), while rectangular plates, featured faster average vertical settling velocities in comparison to square plates, owing to their tendency to settle more frequently in the faster mode 2 of transport (Table 1). Regardless of shape and biofilm growth, denser plastics had larger vertical and horizontal settling velocities due to a larger gravitational force acting upon the plastic in the vertical direction (Table 2). For example, the densest pristine PTFE rectangle plates had average vertical settling that was 188% faster on average than pristine PS plates with the same shape.

The average vertical settling velocity (\(\bar{w}\)) for anisotropic plates (Fig. 6) represented a velocity that was not often observed during experiments. This is due to the multimodal settling distribution of anisotropic plates, with plates either settling in modes 1, 2 or 3. Results show that the average vertical settling velocity for the majority of anisotropic plates represents a transitional velocity, with plates settling with an ensembled average vertical velocity that is between modes 1 and modes 2 or 3 velocities. On the other hand, for isotropic plastics, the average settling velocity is representative a commonly observed velocity, due to their monomodal settling distribution.

The vertical and horizontal settling velocities of the plastics is also dependent on biofilm colonisation (Figs. 6–7 and Table 2). For isotropic spherical plastics, the denser biofouled plastics had average vertical velocities which were faster than the pristine plastics (Table 2), due to a larger submerged weight (Fig. 1B, C, D), which increased gravitational force. For anisotropic plates, biofouling did not increase vertical settling velocities compared to the pristine plastics, despite an increase in plastic density (Fig. 1). Instead, the average vertical settling velocities for anisotropic biofouled plates were reduced by between 1–12%, compared to their pristine counterparts (Table 2). The findings here contrast with those for biofouled fibres27 and fragments28,29, where biofouling increased settling velocities compared to pristine plastics; however, they are consistent with biofouled two-dimensional square plates, where negligible differences between pristine and biofouled equivalents were observed27.

Biofouled anisotropic plastics exhibited slower average vertical velocities and faster average horizontal velocities compared to their pristine counterparts because biofouling induced changes in the dominate mode 1 settling dynamics. Biofilm colonisation caused a heterogeneous mass distribution on the plate’s surface, triggering greater horizontal dispersion (Fig. 4), resulting in faster horizontal velocities, as well as larger oscillatory frequencies, amplitudes and Strouhal number (Fig. 5), which increase drag forces acting on the plate in the vertical direction. The combination of these larger horizontal velocities and greater drag forces acting on biofouled plates leads to reduced settling velocities compared to pristine plates.

The results presented here are crucial for advancing our understanding of plastic pollution transport and fate, as well as improving our ability to predict plastic transport rates and quantify their concentration. This study highlights the importance of considering plastic settling dynamics into predictive settling velocity formulae9,10,47, which will enhance their environmental relevance, particularly regarding larger macroplastic fragments and their interactions with biota. Additionally, the effects of biofouling may need to be integrated into physics-based models designed to predict plastic transport and vertical concentration profiles, derived from the settling velocity distribution of sampled plastics7,8. By refining our predictions of plastic behaviour in aquatic systems and understanding their interactions with biofilms, we can better inform plastic monitoring programs, implement targeted clean-up strategies, and ultimately prevent long-term environmental damage caused by plastic pollution.

Methods

The plastic samples

Nine negatively buoyant macroplastics (plastics >5 mm in size48), were considered for experiments, which are described in Supplementary Table 5. Samples were composed of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), polyoxymethylene (POM) and polystyrene (PS) polymers. Negatively buoyant plastics were used in this experiment as they represent up to 50% of the microplastic and macroplastic pollution that we observed in aquatic environments49,50,51,52. These polymers were also chosen because they cover a wide range of the diversity of negatively buoyant plastic densities observed in the environment (1050 to 2000 kg/m3) (Fig. 1B, C), which allows us to examine the settling dynamics and velocities for a wide spectrum of negatively buoyancy plastics and the impact biofouling has on their settling dynamics.

For each polymer, three shapes were considered, namely rectangular plates (20\(\times\)10\(\times\)1 mm3), square plates (10\(\times\)10\(\times\)1 mm3), and spheres (\(d\) = 5 mm) (Fig. 1A). Fragments, such as the rectangular and square plates used in these experiments, represent one of the top 10 of the most commonly found plastic shapes reported in the Rhine-Meuse delta (the Netherlands)53 and on Saigon River Riverbanks (Vietnam)54. The plastics were also chosen because they represent different levels of geometric anisotropy and are characterised by their maximum (\({L}_{1}\)), intermediate (\({L}_{2}\)) and smallest (\({L}_{3}\)) dimensions. The spherical plastics are isotropic with a homogenous mass distribution. The square plates are anisotropic in two dimensions (i.e. \({L}_{1}\) = \({L}_{2}{{\rm{\ne }}}\) \({L}_{3}\)), while the rectangular plates are anisotropic in all three dimensions (i.e. \({L}_{1}\) ≠ \({L}_{2}\) ≠ \({L}_{3}\)). Both pristine rectangular and square plates have a centred gravity centre with uniform distribution across their area. However, the rectangular plates have uneven axes length and a larger distance away from the centre of mass along the plastic’s longest side (\({L}_{1}\)) compared to square plastics.

Biofouling colonisation procedure and characterisation

To describe the impact of biofouling on the settling dynamics of a plastics, half of the plastics were subjected to biofilm colonisation in laboratory conditions. Plastics were incubated in 500 ml beakers with 50 ml of river sediment and 200 ml of river water, collected from the lower reaches of the River Avon (Bristol, UK). The collected river sediment was mostly composed of clay and silt particles. The plastics were agitated on a shaking table for 14 days at 150 rpm to encourage biofilm attachment and left in sunlight at room temperature (18–22 °C) for three months to promote biofilm growth on the plastic’s surface28,55. After the incubation period, the biofouled plastics were removed from the beakers and dried in an oven at 50 °C for 24 hours. This was in order for plastics to be weighted accurately and their density to be calculated without any wet water content.

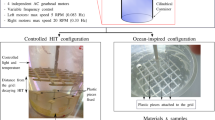

To quantify the biofilm growth on the plastics, a subset of 10 biofouled and pristine plastics were weighted, and their volume and density measured through immersion, according to DIN 53479 standards56. Biofilm growth was quantified as a change in mass and density, compared to the pristine plastics. Biofilm area coverage and biofilm growth spatial distribution were also measured using a photogrammetry technique, designed using the Python library OpenCV57 (Fig. 8A). A subset of 10 plastics was stained with a crystal violet dye, which is a technique commonly used to stain and identify bacteria, to highlight areas of the plastic which were colonised by biofilm58,59. Unstained areas of the plastic indicated an absence of biofilm growth, while areas that were stained purple indicated biofilm colonisation. Photographs were then taken of one face of each plastic under the same lighting conditions and camera settings, and an automated colour threshold routine was used to detect and mask areas of the plastic which were stained purple by the crystal violet dye. This allowed calculation of the biofouled area coverage by determining the percentage of pixels stained purple, relative to the total area of the plastic’s face.

A The automated colour threshold routine used to calculate biofouled area coverage and biofilm spatial variation on the plastic surface using the standard deviation of the pixel colour values. B Photographs of the sessile drop test for contact angle for a PTFE pristine and biofouled plate. C The three-dimensional images of areal surface roughness for a pristine and biofouled PS square plate, using the Keyence VHX-7000 digital microscope. D The settling experimental setup including the bounding box plastic detection output, using a synchronous multi-camera detection routine.

The spatial variation in biofilm colonisation was quantified by calculating the standard deviation of relative pixel colour values across the plastic’s surface (Fig. 8A). If the plastic’s colour does not spatially vary across its surface, meaning pixel values remain relatively constant, the standard deviation of pixel values is zero, indicating uniform biofilm colonisation. A standard deviation greater than zero suggests varying colours across the plastic’s surface—from white (indicating no biofouling) to purple (indicating biofilm colonisation)—highlighting heterogeneous biofouling colonisation across the plastic’s surface. Figure 8A shows a flow diagram of the photogrammetry technique followed, and an exemplary routine provided in ref. 60.

The contact angle (Fig. 8B) and areal surface roughness (Fig. 8C) was also characterised for a subset of 10 rectangular and square biofouled and pristine plastic. Contact angle measurements were performed for the anisotropic pristine and biofouled plastics by employing the sessile drop method, using distilled water with a droplet volume of 10–20 μl61. The droplet was allowed to settle on the surface for 10 seconds before measurements. A Leica DMS 1000 digital microscope, at 40\(\times\) magnification, was used to photograph the droplet and the contact angle was then measured using the angle measurement tools in Fiji (ImageJ) software. The average contact angle was then calculated as average from the 10 repeat samples (Fig. 8B). Note that a contact angle for spheres could not be measured using this method because of their spherical shape.

Areal surface roughness (\({Sa}\)), defined here as the absolute arithmetic mean of the roughness height deviations of the plastic’s surface over a measured area, was characterised for each plastic using a Keyence VHX-7000 digital microscope Fig. 8C. Three-dimensional images of a 500\(\times\)500 μm2 section in the centre of each anisotropic pristine and biofouled plate surfaces were taken to calculate the average areal surface roughness. For spherical plastics, a smaller 100\(\times\)100 μm2 section was imaged for analysis. An example three-dimensional image showing differences in surface roughness between a pristine and biofouled PS square plate is shown in Fig. 8C. The average areal surface roughness for each plastic type was calculated as an average from the 10 repeat samples.

Experimental setup and settling tests

Settling experiments were undertaken in a rectangular settling column water tank 1 m in height (\(z\)), 0.3 m in width (\(x\)), and 0.3 m in length (\(y\)) (Fig. 8D). The settling tank was filled with tap water (salinity 0.01 PSU) to a depth of 0.9 m and kept at room temperature (18–22 °C) during the settling tests. Two small LED spotlights (lighting panel 23 × 20 cm2) were used to illuminate the tank and were positioned away from the settling tank and did not have any influence on heating the setting tank.

To capture the settling plastics and their trajectories, two Logitech C920 cameras (1080p Full HD, 30 frames per second) were positioned using tripods to face the \(z-x\) and \(z-y\) planes of the settling tank (Fig. 8D). The two cameras were set at the same height at a 90° angle away from each other and at a 0.41 m horizontal distance from the outer face of the settling tank. To capture the immediate settling dynamics of the plastics, from their initial release position into equilibrium settling, the cameras were positioned to record the top 0.3 m of the settling tank. This was to ensure the different plastic modes of vertical transport (mode 1, 2 or 3), the transitions and reorientations between these modes, as well as their lateral motion, were captured by the cameras. The cameras were initiated analogously using OBS screen casting software, which allowed for accurate cross-camera time-synchronisation within ±1 frame. Cross-camera time-synchronisation of OBS was validated by using an external flashlight7

Both biofouled and pristine plastics were released into the settling tank one at a time using tweezers at a distance of 2 cm below the water’s surface one at a time. The plastics were dry when released into the tank and were inspected for air bubbles while being held with the tweezers under the water. If air bubbles were observed, the plastics was either taken out of the tank and wiped by hand (for pristine plastics) or shaken in the water (for the biofouled plastics in order not to wipe off the biofilms), to clear the bubbles from the plastic. The water in the tank was allowed to settle again before plastics were dropped into the tank.

Three different release positions were used to capture the full variability of settling dynamics for the rectangular and square plates (Fig. 2M). The first orientation (position 1) forced a slow mode of transport, with the longest edge of the plates normal to the direction of vertical motion. The second release orientation (position 2) intentionally promoted a faster mode of transport, with the longest edge of the plates positioned in the direction of vertical motion. The third release orientation (position 3) corresponded to a transitional orientation, where the plates was released with the longest edge of the plastic at a 45° angle to the direction of motion, thus the plastic was equally susceptible of evolving into either fast or slow orientations of transport. Particle-wall interactions occurred in less than 5% of repeat experiments. Experiments in which particle-wall interactions occurred and hence affected the settling velocity were discarded and repeated.

To capture the different modes of settling for each plastic sample and to decrease statistical uncertainty, 30 repeat settling tests were conducted per release position, resulting in a total number of 90 repeats per sample type. Once the plastic was released into the settling tank, a bounding box detection routine designed using the Python library OpenCV57, was used to capture the plastic’s contours and centre of mass position per frame from each of the two camera’s video sequence. The full particle detection routine, image prepossessing and particle labelling algorithm is described in ref. 8 and an exemplary routine is provided in ref. 60. The coordinates obtained from both cameras were used to determine the plastic’s three-dimensional position (\({x}_{p}\), \({y}_{p}\) and \({z}_{p}\)), where \({z}_{p}\) was calculated as the average vertical \(z\) coordinate from each of the two camera’s video sequence (Fig. 8D). This procedure enabled a three-dimensional reconstruction of the plastic trajectories. In the calculation of the plastics’ settling velocities, camera distortion and calibration was considered as well as refraction correction, which was referenced to the central axis of the tank. Transformation from pixel coordinates to real distance was performed with a multi-point linear transformation. For each plastic, the instantaneous vertical (\({w}_{i}\)) and absolute horizontal \(({V}_{i}=\sqrt{{v}_{{xi}}^{2}+{v}_{{yi}}^{2}})\) velocities were calculated, where \({v}_{{xi}}\) and \({v}_{{yi}}\) are the horizontal velocities in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, and the subscript \(i\) represents instantaneous velocity. The ensembled average vertical settling velocity (\(\bar{w}\)) and absolute horizontal velocity \((\bar{V})\) are calculated as the average velocity of all plastics settling between a vertical depth of 5–20 cm.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Python library Scipy62. All data distributions were first analysed with a set of normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk) to test for normality, in which no distributions satisfied the tests and normality could not be assumed. Therefore, to assess statistically significant differences between groups, a non-parametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney \(U\) was conducted, with a significant level of \(\alpha\) = 0.05.

Data availability

All data for particle trajectories and velocities, as well as codes for particle detection and photogrammetry are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11655959.

Code availability

All codes for particle detection and photogrammetry are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11655959.

References

Clark, B. L. et al. Global assessment of marine plastic exposure risk for oceanic birds. Nat. Commun. 14, 3665 (2023).

De-la-Torre, G. E. Microplastics: an emerging threat to food security and human health. J. Food Sci. Technol. 57, 1601–1608 (2020).

MacLeod, M., Arp, H. P. H., Tekman, M. B. & Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 373, 61–65 (2021).

Talbot, R. & Chang, H. Microplastics in freshwater: a global review of factors affecting spatial and temporal variations. Environ. Pollut. 292, 118393 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Aquatic plastisphere: interactions between plastics and biofilms. Environ. Pollut. 322, 121196 (2023).

Waldschläger, K. et al. Learning from natural sediments to tackle microplastics challenges: a multidisciplinary perspective. Earth Sci. Rev. 228, 104021 (2022).

Valero, D., Belay, B. S., Moreno-Rodenas, A., Kramer, M. & Franca, M. J. The key role of surface tension in the transport and quantification of plastic pollution in rivers. Water Res. 226, 119078 (2022).

Lofty, J. et al. On the vertical structure of non-buoyant plastics in turbulent transport. Water Res. 254, 121306 (2024).

Waldschläger, K. & Schüttrumpf, H. Effects of particle properties on the settling and rise velocities of microplastics in freshwater under laboratory conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1958–1966 (2019).

Goral, K. D. et al. Settling velocity of microplastic particles having regular and irregular shapes. Environ. Res. 228, 115783 (2023).

Khatmullina, L. & Isachenko, I. Settling velocity of microplastic particles of regular shapes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 114, 871–880 (2017).

Voth, G. A. & Soldati, A. Anisotropic particles in turbulence. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 49, 249–276 (2017).

Auguste, F., Magnaudet, J. & Fabre, D. Falling styles of disks. J. Fluid Mech. 719, 388–405 (2013).

Corey, A. T. et al. Influence of shape on the fall velocity of sand grains. https://doi.org/10.17616/R31NJMSY (1949).

Rouse, H. An Analysis of Sediment Transportation in the Light of Fluid Turbulence. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/records/9we10-nep55 (United States Department of Agriculture, 1939).

Lofty, J., Valero, D., Wilson, C. A. M. E., Franca, M. J. & Ouro, P. Microplastic and natural sediment in bed load saltation: material does not dictate the fate. Water Res. 243, 120329 (2023).

Cowger, W., Gray, A. B., Guilinger, J. J., Fong, B. & Waldschläger, K. Concentration depth profiles of microplastic particles in river flow and implications for surface sampling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6032–6041 (2021).

Bhagwat, G., O’Connor, W., Grainge, I. & Palanisami, T. Understanding the fundamental basis for biofilm formation on plastic surfaces: role of conditioning films. Front. Microbiol. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.687118 (2021).

Rummel, C. D., Jahnke, A., Gorokhova, E., Kühnel, D. & Schmitt-Jansen, M. Impacts of biofilm formation on the fate and potential effects of microplastic in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 258–267 (2017).

Zheng, S. et al. Implication of Surface Properties, Bacterial Motility, and Hydrodynamic Conditions on Bacterial Surface Sensing and Their Initial Adhesion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.643722 (2021).

Zettler, E. R., Mincer, T. J. & Amaral-Zettler, L. A. Life in the ‘plastisphere’: microbial communities on plastic marine debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 7137–7146 (2013).

Kaiser, D., Kowalski, N. & Waniek, J. J. Effects of biofouling on the sinking behavior of microplastics. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 124003 (2017).

Lee, S. Y., An, J., Kim, J. & Kwon, J. H. Enhanced settling of microplastics after biofilm development: a laboratory column study mimicking wastewater clarifiers. Environ. Pollut. 311, 119909 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Biofilm influenced metal accumulation onto plastic debris in different freshwaters. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117646 (2021).

Meng, D. & Li, Y. Assessing the settling velocity of biofilm-encrusted microplastics: accounting for biofilms as an equivalent to surface roughness. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.EST.3C07147 (2024).

Kooi, M., Nes, E. H., van, Scheffer, M. & Koelmans, A. A. Ups and downs in the ocean: effects of biofouling on vertical transport of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7963–7971 (2017).

Jalón-Rojas, I. et al. Effects of biofilms and particle physical properties on the rising and settling velocities of microplastic fibers and sheets. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.EST.2C01302 (2022).

Mendrik, F., Fernández, R., Hackney, C. R., Waller, C. & Parsons, D. R. Non-buoyant microplastic settling velocity varies with biofilm growth and ambient water salinity. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–9 (2023).

Parrella, F., Brizzolara, S., Holzner, M. & Mitrano, D. M. Impact of heteroaggregation between microplastics and algae on particle vertical transport. Nat. Water 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00248-z (2024).

Field, S. B., Klaus, M., Moore, M. G. & Nori, F. Chaotic dynamics of falling disks. Nature 388, 252–254 (1997).

Zhong, H., Chen, S. & Lee, C. Experimental study of freely falling thin disks: transition from planar zigzag to spiral. Phys. Fluids 23, 11702 (2011).

Wang, W. B., Hu, R. F., Xu, S. J. & Wu, Z. N. Influence of aspect ratio on tumbling plates. J. Fluid Mech. 733, 650–679 (2013).

Anderson, A., Pesavento, U. & Wang, Z. J. Unsteady aerodynamics of fluttering and tumbling plates. J. Fluid Mech. 541, 65 (2005).

Xiang, Y., Qin, S., Huang, W., Wang, F. & Liu, H. Trajectory modes and wake patterns of freely falling plates. J. Vis. 21, 433–441 (2018).

Jayaweera, K. O. L. F. & Mason, B. J. The behaviour of freely falling cylinders and cones in a viscous fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 22, 709 (1965).

Horowitz, M. & Williamson, C. H. K. Dynamics of a rising and falling cylinder. J. Fluids Struct. 22, 837–843 (2006).

Angle, B. R., Rau, M. J. & Byron, M. L. Settling of nonuniform cylinders at intermediate Reynolds numbers. Phys. Rev. Fluids 9, 070501 (2024).

Ern, P., Risso, F., Fabre, D. & Magnaudet, J. Wake-induced oscillatory paths of bodies freely rising or falling in fluids. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 44, 97–121 (2012).

Smith, E. H. Autorotating wings: an experimental investigation. J. Fluid Mech. 50, 513–534 (1971).

Belmonte, A., Eisenberg, H. & Moses, E. From flutter to tumble: inertial drag and froude similarity in falling paper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 345–348 (1998).

Yang, G. et al. Settling behaviors of microplastic disks in water. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114657 (2023).

Huang, W., Liu, H., Wang, F., Wu, J. & Zhang, H. P. Experimental study of a freely falling plate with an inhomogeneous mass distribution. Phys. Rev. E 88, 053008 (2013).

Van Melkebeke, M., Janssen, C. & De Meester, S. Characteristics and sinking behavior of typical microplastics including the potential effect of biofouling: implications for remediation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 8668–8680 (2020).

Binda, G. et al. Physicochemical and biological ageing processes of (micro)plastics in the environment: a multi-tiered study on polyethylene. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 6298–6312 (2023).

Kerr, A. & Cowling, M. J. The effects of surface topography on the accumulation of biofouling. Philos. Mag. 83, 2779–2795 (2003).

Williams, G. P. Particle roundness and surface texture effects on fall velocity. J. Sediment. Res. 36, 255–259 (1966).

Yu, Z., Yang, G. & Zhang, W. A new model for the terminal settling velocity of microplastics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113449 (2022).

Hartmann, N. B. et al. Are we speaking the same language? Recommendations for a definition and categorization framework for plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1039–1047 (2019).

Moses, S. R., Löder, M. G. J., Herrmann, F. & Laforsch, C. Seasonal variations of microplastic pollution in the German River Weser. Sci. Total Environ. 902, 166463 (2023).

Lofty, J., Ouro, P. & Wilson, C. A. M. E. Microplastics in the riverine environment: meta-analysis and quality criteria for developing robust field sampling procedures. Sci. Total Environ. 863, 160893 (2023).

Blondel, E. & Buschman, F. A. Vertical and horizontal plastic litter distribution in a bend of a tidal river. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.861457 (2022).

McGoran, A. R., Clark, P. F., Smith, B. D. & Morritt, D. Macrolitter and mesolitter in the Thames Estuary: a temporal litter assessment and brand audit of submerged and riverbed debris. Environ. Pollut. 337, 122484 (2023).

van Emmerik, T. et al. Riverbank macrolitter in the Dutch Rhine-Meuse delta. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104087 (2020).

Nguyen, K. L. P. & Bui, T.-K. L. Riverbank macro-litters monitoring in downstream of Saigon river, Ho Chi Minh City. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 7, 100306 (2023).

Hoellein, T. J., Shogren, A. J., Tank, J. L., Risteca, P. & Kelly, J. J. Microplastic deposition velocity in streams follows patterns for naturally occurring allochthonous particles. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

ISO. ISO-ISO 1183-1:2019-Plastics—Methods for Determining the Density of Non-cellular Plastics—Part 1: Immersion Method, Liquid Pycnometer Method and Titration Method. https://www.iso.org/standard/74990.html (ISO, 2019).

Bradski, G. The openCV library. Dr. Dobb’s. J. Softw. Tools Profess. Program. 25, 120–123 (2000).

Feoktistova, M., Geserick, P. & Leverkus, M. Crystal violet assay for determining viability of cultured cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, pdb.prot087379 (2016).

Wilson, C. et al. Quantitative and qualitative assessment methods for biofilm growth: a mini-review. Res. Rev. J. Eng. Technol. 6, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30214915/ (2017).

Lofty, J. JamesLofty/Biofilm_settling_plastic: biofouled plastic settling codes. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.11655959 (2024).

Sturm, M. T., Schuhen, K. & Horn, H. Method for rapid biofilm cultivation on microplastics and investigation of its effect on the agglomeration and removal of microplastics using organosilanes. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151388 (2022).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Erasmus+ and the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) grant number EP/T517951/1 (J.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

James Lofty conceptualised, conducted, and wrote the original draft of the investigation. Catherine Wilson and Pablo Ouro conceptualised and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lofty, J., Wilson, C. & Ouro, P. Biofouling changes the settling dynamics of macroplastic plates. Commun Earth Environ 5, 750 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01922-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01922-6