Abstract

China, the largest carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter in the world, is committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. However, the characteristics and driving factors of the CO2 emissions from industrial processes and product use (IPPU) in China have been unclear. Here, using the most comprehensive statistics of 18 industrial productions and 2 product uses during 2000–2020, we find China’s IPPU CO2 emissions reached 1628 million metric tons (Mt) in 2020, which were 3.0%–6.5% higher than estimates from other studies. Compared to previous studies identifying main driving factors of combined CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel and IPPU, we show that the main indicators of China’s IPPU emissions growth was the per capita construction area during 2000–2020 (94%). We construct a comprehensive provincial IPPU emission inventory based on the up-to-date provincial-level statistics, identifying the key mitigation regions in China. This study reveals China’s IPPU emissions are the non-ignorable factor in China’s carbon mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to decades of rapid economic development, China has become the largest contributor to global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (accounting for 31.9% of the global emissions in 20201). In addition to fossil-fuel combustion emissions that have attracted widespread attention, CO2 emissions from industrial processes and product use (IPPU) are also an anthropogenic source of carbon emissions in China that deserves attention2. CO2 emissions from IPPU include emissions generated from chemically or physically transform materials (e.g. cement production) and emissions as the byproducts of various non-energy-related industrial activities (e.g. methanol production)3. Based on China’s national inventory reported to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), China’s CO2 emissions from IPPU were 1466 million metric tons (Mt) in 20184, accounting for ~15% of the total anthropogenic CO2 emissions in China. To mitigate global climate change, China pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Numerous studies have estimated China’s CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion at the city level, provincial level, and national level, and analyzed the driving factors of fossil fuel emissions, and pointed out that the realization of carbon neutrality of fossil fuel emissions is highly correlated with the adjustment of energy structure5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Based on the above studies, China proposed policies focusing on reducing the consumption of fossil-fuel energy and transforming the energy structure towards renewable energy12, which could minimize China’s CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion. However, these strategies cannot help China achieve its carbon neutrality goal, as the strategy does not consider the CO2 emissions from IPPU13. For promoting the development of policies aimed at reducing IPPU emissions, it is necessary to understand the characteristics and driving forces of IPPU emissions. A comprehensive understanding of China’s IPPU emissions is important for achieving China’s commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

There are a few studies estimating long-term (over 20 years) IPPU emissions in China from more than 10 sectors14,15. The 2 studies neither cover the emissions from all sectors nor point out what drove the changes of China’s IPPU emission during 2000–2020, leaving us with little information about the mechanism or the indicators of China’s IPPU emissions. Some studies have analyzed the indicators of China’s IPPU emissions from cement industry11,16. However, the indicators they selected were either specific to the cement industry16 e.g. carbon emissions per unit of cement product, or were the same as the indicators of fossil fuel combustion emissions11, e.g. energy consumption and energy efficiency, which were not specifically suitable for analyzing the indicators of China’s IPPU emissions.

The main purpose of this study is to improve the estimates of China’s CO2 emissions from IPPU over the past two decades from national level and provincial level and identify what drove the variations of China’s IPPU emissions. Here, we explore the largest number of IPPU sectors (18 industrial production processes and 2 product uses) in China during 2000–2020 and establish the most comprehensive national IPPU emission inventory, based on official national statistics. For digging out the indicators behind the changes, we then focus on the driving forces of the changes in the CO2 emissions from IPPU, as controlling these emissions is crucial for meeting China’s carbon mitigation goals. For identifying the key regions for China’s CO2 emissions reduction, we improve the provincial IPPU emission inventory during 2000–2020 based on the up-to-date provincial-level statistics. The dynamics in China’s IPPU emissions during 2000–2020 are analyzed by sector and by the province to identify key targets for IPPU emissions reduction in China. Notably, we emphasize the significance of IPPU emissions at both the national and global scales.

Results

Fast-growing CO2 emissions from IPPU during 2000–2020

Based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories3, this study estimates the largest number of IPPU sectors (18 industrial production processes and 2 product uses in China, compared to 11 sectors by National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)17,18,19,20,21 and 13 sectors by Yu et al15. shown in Table S1). The total CO2 emissions from IPPU increased from 459 ± 10 Mt in 2000 to 1628 ± 31 Mt in 2020, with the mean annual growth rate of 6.5% yr−1 (58 Mt yr−1). The formula for calculating the mean annual growth rate in this paper can be found in the Methods. The emission uncertainty results for each year are listed in Table S2. During 2000–2014, the CO2 emissions from IPPU portrayed rapid growth, with the mean annual growth rate of 8.4% yr−1 (69 Mt yr−1). After the rapid growth during 2000–2014, China’s IPPU CO2 emissions decreased by 1.2% yr−1 (16 Mt yr−1) during 2014–2015, increased slightly by 1.5% yr−1 (22 Mt yr−1) during 2015–2018, and increased rapidly again during 2018 − 2020 by 5.3% yr−1 (80 Mt yr−1) (Fig. 1a).

a A stacked graph of IPPU emissions in China from 2000–2020. The area of color represents the emissions of the corresponding sector. b Comparison of China’s CO2 emissions from IPPU estimated in this study and from fossil fuels based on the global carbon budget (GCB)24. c The growth contribution to China’s CO2 emissions from IPPU by sectors during 2000–2020. d The proportions of emissions from each sector to total IPPU emissions from 2000 to 2020. The proportion of sectors with a proportion of less than 1% is not indicated in the figure.

We compile China’s IPPU emissions from different estimates between 2000 and 202014,15, including ourselves (Fig. 1a). Our estimates (on average 1087 Mt during 2000–2020) were 5.9% and 3.0% higher than those presented by Yu et al15. and Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) v8.022, respectively, and our estimates (on average 1153 Mt in 2005, 2010, 2012, and 2014) were 6.5% higher than those in China’s national inventories reported to the UNFCCC estimated by NDRC17,18,19,20,21. One of the reasons why our results are higher than Yu et al.’s is the cement clinker emission factors adopted in our study (0.54 tCO2/t) are higher than Yu et al.’s (0.50 tCO2/t). The cement clinker emission factor used by Yu et al. only considers calcium oxide and ignores that China’s cement clinker contains about 0.7% to 4% magnesium oxide, and thus is 10% lower than the clinker emission factor we use23. Another main reason for our higher estimates is that this study covers more emission sources. According to the IPCC Guidelines3, the CO2 emissions from IPPU involve four categories: mineral industry, chemical industry, metal industry, and the non-energy products from fuels and solvent use, including the sectors of 23 industrial productions and two product uses in detail (Table S1). Yu et al. and NDRC neither estimated the CO2 emissions from titanium dioxide production whose emissions in 2020 were nearly 19 times higher than those in 2000 in our results (Fig. 2a)15,17,18,19,20,21, CO2 emissions from ethylene, ethylene oxide, acrylonitrile, and carbon black production which is an important part of IPPU emissions (6.4%) in our results, nor CO2 emissions from lubricant use and paraffin wax use, which are also included in this study. EDGAR classifies China’s IPPU emissions broadly, and therefore it is not clear whether EDGAR covered all IPPU sectors in China22. Meanwhile, EDGAR has not yet published the emission factors and activity data used in IPPU sectors, so the reason for the gap between the estimates of this study and of EDGAR cannot be figured out.

a Emissions from 18 industrial processes and 2 product use (4 industries). b Emissions from the mineral industry. c Emissions from the chemical industry. d Emissions from the metal industry. e Emissions from the non-energy products and solvent use. Please note that the ranges of the y-axis are different in each subplot. The serial number on the right side of each line in the figures is consistent with the serial number in the legend, representing the sector corresponding to each line. The dotted lines in Fig. 2a, c, d are used to connect serial numbers and lines. Data points marked with “田” indicate that the data for that year are extrapolated or interpolated. Please note that there are breakpoints on the y-axis in Fig. 2a, c.

The rapid growth rate of the CO2 emissions from IPPU is worthy of attention. Our estimates show that China’s IPPU emissions increase by 255% from 2000 to 2020, greater than the 233% increase of emissions from fossil-fuel combustion estimated by global carbon budget (GCB)24. As Fig. 1b shows, the proportion of CO2 emissions from IPPU to the CO2 emissions from fossil fuels has increased from 15% in 2012 to 17% in 2020. Meanwhile, the mean annual growth rates of China’s IPPU emissions (6.5% yr−1) were also higher than those of China’s fossil fuel combustion emissions (5.8% yr−1) during 2000–2020. This indicates that during 2000–2020, China’s IPPU emissions increased at a faster relative rate than the emissions from fossil fuels, implying that the contribution of IPPU CO2 emissions to the total CO2 emissions of China may increase in the future. Thus, it is urgent to investigate the driving factors behind the non-ignorable increasing China’s IPPU emissions during 2000–2020 by details.

Contributions to the growth of IPPU emissions by each sector

Shown in Fig. 1c, the top five sectors that contributed the most to the rapid growth of IPPU emissions in China during 2000–2020 were cement (52%), lime (16%), iron and steel (7.3%), aluminum (4.7%), and ammonia (4.3%), which contributed more than 85% of the increase of China’s IPPU emissions in 2020.

Cement production is also the largest contributor to China’s IPPU emissions, which, on average, contributed more than 50% of the total CO2 emissions from IPPU and dominated the decrease in the IPPU emissions during 2014–2015 (Fig. 1d). Minus 1% for exports, 99% of cement has been consumed as construction materials in the construction industry during 2000–202016,25. CO2 emissions from cement production increased from 232 Mt in 2000 to 763 Mt in 2014 due to the rising cement production, mostly driven by the rapid development of construction industry. The falling house prices cut the demand for construction area and for cement production16, causing a drop in CO2 emissions from cement production (−36 Mt) during 2014–2015. While emissions from other sectors increased (20 Mt), the drop in cement emissions drove the decline in the total IPPU emissions (−16 Mt) during 2014–2015. After 2015, the cement clinker production kept increasing and the contribution of cement production to the total CO2 emissions from IPPU entered a relatively stable period, which stabilized at 52–53% during 2015–2020.

The second-largest contributor to the rapid growth of CO2 emissions from IPPU during 2000–2020 was lime production (16%), contributing 16% of the total CO2 emissions from IPPU in 2020. The CO2 emissions from lime production kept increasing from 76 Mt in 2000 to 267 Mt in 2020 (Fig. 1d). The third-largest contributor to the rapid growth of CO2 emissions from IPPU during 2000–2020 was the iron and steel production (7.3%), accounting for 6.1% of the total emissions from IPPU in 2020 (Fig. 1c). China’s CO2 emissions from iron and steel production increased from 14 Mt in 2000 to 100 Mt in 2013, declined to 82 Mt in 2016, and then reversed to 99 Mt in 2020. This variation was consistent with the changing demand for iron and steel productions in the construction industry, which consumed more than 52% of iron and steel products26.

The combined CO2 emissions from other 17 sectors increased from 137 Mt in 2000 to 419 Mt in 2020, contributing 24% to the increase in China’s IPPU emissions during 2000–2020. The proportions of CO2 emissions from each sector of aluminum, ferroalloys, ethylene, methanol, and carbide production to the total IPPU CO2 emissions in China were similar, ranging from 2–4% in 2020, whereas the combined CO2 emissions from the production of paraffin wax, lubricant, zinc, lead, magnesium, and titanium dioxide were 1.4% of the total IPPU emissions in the country in 2020.

As shown in Fig. 2a, the ratios of emissions from titanium dioxide production in 2020 relative to 2000 (1933%) are higher than the ratios of emissions from other sectors, which could be explained by two reasons. One is that its absolute emissions were small in 2000, increasing from 0.00255 Mt in 2000 to 0.04930 Mt in 2020. The second is that titanium dioxide is mainly used as a coating. With the rapid development of the construction industry after 2000, the consumption of coatings increased rapidly, and the demand for titanium dioxide rose rapidly.

Among the top five sectors with a large contribution to the increase in China’s IPPU emissions, the emissions from ammonia and iron and steel production have shown the peak points, but the emissions from cement, lime, and aluminum production are still rising and have not yet presented the peak points (Figs. 2b–e, S1a–f). To achieve carbon neutrality of China’s IPPU emissions, we should focus on sectors such as cement and lime production, whose emissions account for a large proportion of IPPU emissions, contribute greatly to growth, and have not yet seen the peak points.

In this study, we also compare the CO2 emissions from individual IPPU sectors estimated in this study to those reported in previous studies (Fig. S1). The changing trends of CO2 emissions from the cement production estimated in this study were consistent with those estimated in other studies conducted from 2000 to 201618, 24,27,28,29,30 (Fig. S1b). Our estimates were average 2.3% and 7.1% higher than those of EDGAR and Yu et al. during 2000–2020 in CO2 emissions from cement production15,22, while we adopt the updated and local emission factor measured by NDRC23. The reasons for our higher results have been explained above. While there were divergences in estimates of CO2 emissions from the ammonia, iron and steel, and ferroalloy production between this study and other studies (Fig. S1), we made a point-by-point comparison which was detailed in Section 3 of SI. By comparing the differences in emission factors, activity data, and accounting methods point by point, and understanding the economic development status of each sector during 2000–2020, we believe that the estimates of China’s IPPU CO2 emissions calculated in this study were improved by including the most relevant IPPU sectors, as well as adopting reasonable production data and the up-to-date emission factors.

Indicators of increasing IPPU emissions

To further understand and quantify the driving indicators of IPPU emissions in China from 2000 to 2020, we adopt the logarithmic mean Divisia index (LMDI) method (see Methods). The indicators used in the previous studies were not the optimal to identify the indicators of changes of IPPU emissions, e.g., energy consumption and energy efficiency11,16. We choose indicators that cover all industries as much as possible to explore which industry and corresponding factors contribute the most to changes in China’s IPPU emissions. In this study, we consider the indicators for driving analysis according to the downstream consumption and demand of industrial products (Fig. S3). This study found that the construction, industry and agriculture stimulated 1106, 122 and 102 Mt of IPPU emissions in China respectively, correspondingly stimulating 68%, 7.5% and 6.3% of China’s IPPU emissions in 2020 (see data and calculation methods in detail in Supplementary Note 1 in Supplementary Information). Therefore, we choose three indexes that can reflect the development of the construction, industry, and many other sectors to formulate the decomposition indicators of LMDI method, including construction area, secondary industry’s GDP (secondary industry equals to construction and industry), and population. Construction area can reflect the actual development of the construction industry31. Secondary industry’s GDP can reflect the economic conditions of construction and industry. In addition, population, which has impacts to all industries (including agriculture), is widely used as the decomposition indicators for digging out the drivers of fossil fuel carbon emissions11,32,33,34. Combined with IPPU emissions estimated in this study, these indexes constituted four indicators in the Eq. (2), including carbon intensity (\({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{int}}}}\), calculated as the IPPU emissions per unit of value added by the secondary industry), population (\({{{\rm{POP}}}}\)), per capita construction area (\({{{{\rm{CA}}}}}_{{{{\rm{pop}}}}}\)), and changes in the secondary industry’s value leveraged per unit of construction area (\({{{{\rm{ECO}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ca}}}}}\)). Per capita construction area is the ratio of construction area to population, and secondary industry’s value leveraged per unit of construction area is the ratio of secondary industry’s GDP to construction area.

The results indicated that the growth of IPPU emissions in China from 2000 to 2020 was driven by per capita construction area (94%), and population (5.0%). As shown in Fig. 3a, the decrease in the IPPU emissions was mainly driven by the changes in the secondary industry’s value leveraged per unit of construction area (−33%), and the carbon intensity (−15%).

a Boxplots of decomposition factors of IPPU in China during 2000–2020. “Cint” refers to carbon intensity (CO2 emissions per unit of value added by the secondary industry); “CApop” denotes per capita construction area; “ECOca” stands for the changes in the secondary industry’s value leveraged per unit of construction area; and “POP” denotes the population. b The decomposition factor of emission changes over 2000–2020.

The changes in carbon intensity are worthy of attention (Fig. 3b). The increase in carbon intensity occurred five times during 2000–2020. In 2002–2003, 2008–2009, 2012–2013, and 2018–2019, 2019–2020, the increase in the carbon intensity increased the carbon emissions from IPPU by 25, 25, 32, 56 and 58 Mt, respectively. Interestingly, these five periods coincided with the SARS outbreak, the global financial crisis, China’s economic structure adjustment, China’s economic growth slowing down, and the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively35. China’s economy was in shock during these events, however, the CO2 emissions from IPPU increased instead of dropping during these periods (Fig. 3b). When China’s economy was hit during 2002–2003, 2008–2009, 2012–2013, and 2018–2019, 2019–2020, the construction area, especially residential construction area, increased, which was probably related to China’s national policy of stimulating housing consumption to promote economic growth. For example, when China’s economy was deeply affected by global financial crisis in 2008, the demand for exports dropped sharply36. In order to boost national economic growth, the country could only stimulate domestic demand36. As the pillar of China’s economy, the real estate market is one of China’s main goals to boost economic growth37. Therefore, China implemented a proactive fiscal policy and a moderately loose monetary policy38, which stimulated domestic residential housing consumption and the development of the real estate market38, and then increased the demand for the production of related products (such as cement, lime, iron and steel), resulting in an increase in IPPU emissions dominated by cement, lime, steel and other products.

During 2000–2020, the only period in which IPPU emissions decreased was in 2014–2015, which was also the only period when the per capita construction area decreased. As shown in Fig. 3b, the carbon intensity and the per capita construction area dropped in 2014–2015, driving a drop of 16 Mt of IPPU emissions, resulting in an overall downward trend in the IPPU CO2 emissions in 2014–2015. In 2015, the growth rate of China’s real estate development investment slowed down, and the national residential construction area decreased by 0.7% compared with 201439, which led to an overall decline in the national construction area and per capita construction area. This may lead to a decline in demand for products such as cement, lime, and steel, and ultimately lead to a decline in IPPU emissions. Additionally, the population drove only 5% of IPPU emissions’ increase during 2000–2020, indicating that population is not optimal when choosing a proxy to allocate national emissions to provincial emissions.

Regional differences in IPPU emissions

For identifying the key regions in China for mitigating of the country’s CO2 emissions from IPPU, we calculate the CO2 emissions from data-available sectors (cement, lime, calcium carbide, aluminum, ethylene, flat glass, and soda ash) in 31 provinces across China, based on available provincial-level statistics (see “Methods”). In 2020, the total provincial carbon emissions from IPPU from the seven sectors were 1313 Mt, which was relatively consistent with the national total IPPU emissions from the same sectors estimated by this study (1258 Mt).

As shown in Fig. 4, the main contributors to China’s IPPU emissions are concentrated in the coastal and eastern regions. In 2020, the Jiangsu (104 Mt), Anhui (98 Mt), Shandong (97 Mt), Henan (90 Mt), Guangdong (89 Mt), and Zhejiang (70 Mt) provinces were the top six contributors to China’s CO2 emissions from these seven sectors, accounting for 42% of the China’s total CO2 emissions from the sectors (1313 Mt). From 2000 to 2020, the growth in the CO2 emissions from IPPU was mainly driven by the Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong, Guangdong, Henan, and Zhejiang provinces, with an average annual growth of 4.6, 4.3, 3.6, 3.4, 3.3, and 2.7 Mt yr−1, respectively (Fig. 4e). The pillar industries in these provinces are the cement and lime industries, which are the concentrations of China’s cement and lime production capacity. From 2000 to 2020, Anhui, Jiangsu, Shandong, Guangdong, Henan and Zhejiang produced the most cement and lime products, and contributed 6.8%, 5.9%, 5.2%, 4.4% and 5.0% of the national cement production growth, and 18.0%, 17.7%, 7.3%, 5.1%, 13.8% and 6.4% of the national lime production growth, respectively40,41,42. To achieve China’s carbon mitigation goal, it is necessary to control the carbon emissions from IPPU in these provinces.

a Provincial emission patterns in 2020 (based on this study). b Provincial emission patterns based on the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) in 2020. c Annual growth of IPPU emissions in each province during 2000–2020 (based on this study). d Annual growth of IPPU emissions in each province during 2000–2020 (based on EDGAR). e Average annual increase in IPPU emission from 2000 to 2020 by province, based on this study. The different colors of the columns represent different growth rates, and their specific meanings are consistent with the legends in Fig. 4c and d.

Tibet (3.7 Mt), Beijing (5.1 Mt), Shanghai (7.9 Mt), Qinghai (8.7 Mt), Hainan (9.1 Mt), and Tianjin (9.2 Mt) contributed less CO2 emission from these sectors in 2020 (Fig. 4a). Note that the growth rates of Beijing, Tibet, Shanghai, Tianjin, Qinghai, and Hainan were also provinces with slower growth rate during this period, with the average annual growth rates being −0.025, 0.18, 0.23, 0.36, 0.39, and 0.40 Mt yr−1, respectively (Fig. 4e). The emissions in developed regions in China (provinces with high GDP per capita), such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin, were lower than those in the underdeveloped regions, such as Xinjiang, Gansu, and Guangxi, indicating that the underdeveloped regions relied more extensively on heavy and manufacturing industries. This implies that underdeveloped regions, with lower technology efficiencies, may have more difficulties mitigating the CO2 emissions from IPPU than developed regions.

The provincial IPPU emission characteristics and key emission units estimated by EDGAR are quite different from this study. As shown in Fig. 4b shows, the EDGAR estimates indicate that the main contributors to China’s IPPU emissions in 2020 were the Shandong (134 Mt), Jiangsu (113 Mt), and Henan (99 Mt) provinces22, while this study highlights Jiangsu, Anhui, and Shandong. In 2020, Zhejiang was the sixth largest contributor to IPPU emissions in this study (70 Mt), however, it ranked 17th (51 Mt) and contributed lower IPPU emissions than Hubei (92 Mt), Hebei (88 Mt), and Liaoning (86 Mt) in the estimates of EDGAR. According to China’s official statistics42, in 2020, the industrial production of Hubei, Hebei, and Liaoning was much less than that of Zhejiang, which was contrary to the estimates of EDGAR. Moreover, there was a difference in the distribution of provinces with the fastest growth rates in our study and in the EDGAR study. As Fig. 4d shows, the estimates of EDGAR showed that Shandong (4.4 Mt yr−1), Jiangsu (4.0 Mt yr−1), Hubei (3.4 Mt yr−1), Liaoning (3.2 Mt yr−1), and Henan (3.2 Mt yr−1) were the top five contributors to the growth of IPPU emissions during 2000–2020, which is highly consistent with the growth of provincial population42. This study presented that Anhui (4.6 Mt yr−1), Jiangsu (4.3 Mt yr−1), Shandong (3.6 Mt yr−1), Guangdong (3.4 Mt yr−1), and Henan (3.3 Mt yr−1) were the top five contributors to the growth of IPPU emissions during 2000–2020.

EDGAR used population as the main proxy data when producing the gridded map of CO2 emissions from IPPU sectors, including cement, lime, ammonia, iron and steel, aluminum, magnesium, zinc, lead production, and non-energy use of fuels43. Janssens-Maenhout et al. mentioned that they developed specific proxy data for the world’s leading cement producers (such as Brazil, the United States, China and India) based on population, the plant location and annual facility throughout of the plants. However, the incomplete list of cement plants (especially those with smaller throughout) could result in the country’s total cement emissions being allocated to the single point source43. Instead, they estimated the annual emissions of each cement facility, and then allocated the part of cement facility emissions that does not match the country total emissions based on the population43. This could mainly explain why the provincial emissions results derived from EDGAR gridded maps does not match the provincial emissions estimated in this study based on provincial-level industrial production. Based on the above analysis, we suggest that the population is not a good choice for allocating national emissions to provincial emissions.

Significance of CO2 emissions from IPPU in China

Combined with the analysis made above in this study, the ignorable increasing trend of China’s IPPU emissions is reflected in the fact that China’s total IPPU emissions currently maintains a growth rate higher than that of fossil fuel combustion carbon emissions, IPPU emissions from key sectors (cement, lime, aluminum, etc.) have not yet reached their peak, and key IPPU emissions regions (Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, etc.) have maintained high emission growth rate, which means that controlling China’s IPPU emissions is very necessary for global climate mitigation.

The rapid increasing China’s IPPU CO2 emissions are a non-ignorable challenge to global IPPU emissions abatement, while the IPPU emissions of other major carbon-emitting countries have peaked and stabilized. We collect the CO2 emissions data of Annex I countries (mainly developed countries) during 1990–2020 reported to the UNFCCC, including the United States of America, the Russian Federation (Russia), Japan, Germany, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) of Great Britain, and northern Ireland (in the UK)44. As shown in Fig. 5a, since 2000, China has been the largest contributor of CO2 emissions from IPPU at the global scale; its emissions from IPPU (959 Mt) have exceeded the total IPPU emissions from the Annex I countries (930 Mt) since 2008. Since 2000, the IPPU CO2 emissions of the Annex I countries have stabilized, and since 2009, the emissions have decreased rapidly to 765 Mt. During 2000–2020, China’s IPPU emissions increased by 255%, while IPPU emissions in Annex I countries decreased by 11%. The growth rate of China’s IPPU emissions far exceeded the growth rate of IPPU emissions in other countries. During 2000–2020, the CO2 emissions from IPPU in China portrayed an increasing trend from 2000 to 2020, amounting to approximately twice the IPPU emissions from the Annex I countries in 2020 (Fig. 5a). In 2020, China’s CO2 emissions from IPPU (1628 Mt) were 4 Mt more than the total CO2 emissions (from both IPPU and fossil-fuel combustion) of Russia (1624 Mt), 56% larger than the emissions of Japan (1042 Mt), 2.5 times the emissions of Germany (639 Mt), and five times the emissions of the UK (327 Mt) (Fig. 5b).

a Comparison of CO2 emissions from IPPU in China with those in other countries. b Comparison of CO2 emissions from IPPU in China with the total CO2 emissions in other countries in 2020, namely, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States of American (USA). The data of CO2 emissions from IPPU in China were derived in this study, and those of other countries were derived from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)45. LULUCF means CO2 emission from land use, land-use change and forestry.

If it continues not to be controlled or mitigated in the future, IPPU emissions are likely to continue to rise, which will make it difficult for China to achieve its carbon neutrality goal. According to this study, the growth of China’s IPPU emissions is highly related to the growth of per capita construction area, which was projected to rise in the future45, indicating that China’s IPPU emissions will continue to grow from the source. At present, China has proposed a carbon neutrality goal, with energy reform as the main body12. Under energy reform, fossil fuel combustion emissions will decline in the future. However, there is no relevant policies or measures specifically aimed at reducing IPPU emissions. Without being controlled, IPPU emissions linked to market demand and economic development will continue to grow in the future, posing challenges to China’s carbon neutrality achievement. In the future, policymakers should consider regulating China’s IPPU emissions.

In addition, China’s IPPU emission accounting can promote the openness and transparency of statistical data in more than 20 sectors, and can provide data for the unknown reduction potential and cost of China’s IPPU emissions. We tried our best to collect the latest and most complete official data in this study. It’s not easy when collecting data and selecting it. Production data for less valued sectors (e.g., titanium dioxide, magnesium, etc.) were not continuously counted or published. Also, we found that different statistical calibers made the production data of the same sector (e.g., cement, etc.) very different. In the methods section, we mentioned that four sets of cement and cement clinker production data were collected in the initial stage of this study. Although these four sets of data all come from official statistics, they belong to four different statistical calibers. There are large differences between these four sets of data in the same year. For example, China’s cement clinker production in 2003 from the China Industry Statistical Yearbook was 543 Mt46, while the data from the China Statistical Yearbook for the same year was 657 Mt42, with a difference of 21%. This shows that data from more than 20 sectors need to be made public urgently, and the statistical caliber of these data needs to be unified. In addition, the reduction potential and costs of China’s IPPU emissions have not yet been quantified and need to be further understood for developing policies towards carbon neutrality goals. The results and data provided by this study can provide a basis for subsequent research on reduction potential and costs.

Methods

Emissions estimates and data sources

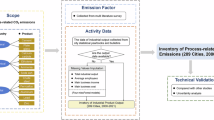

In this study, we consider the CO2 emissions from 18 industrial productions and 2 product uses in China: the production of (1) cement, (2) lime, (3) glass, (4) ammonia, (5) carbide, (6) titanium dioxide, (7) soda ash, (8) methanol, (9) ethylene, (10) ethylene oxide, (11) acrylonitrile, (12) carbon black, (13) iron and steel, (14) ferroalloys, (15) aluminum, (16) magnesium, (17) lead, (18) zinc and (19) lubricant use and (20) paraffin wax. Based on the national-level data availability of the IPPU sectors in China, we adopt the Tier 2 method to analyze the carbon emissions from cement and iron and steel production, based on the 2006 and 2019 IPCC guidelines3,47. Tier 1 is based on national production data and default emission factors. Tier 2 uses process-related production data and localized emission factors. More specifically, when calculating emissions from cement production, Tier 2 is based directly on clinker production rather than inferring clinker production from cement production like Tier 1, and Tier 2 is based on China’s localized emission factor (0.538 tCO2/t)48 rather than the default emission factor (0.52 tCO2/t)3. When calculating emissions from iron and steel production, Tier 2 is based on the different types of crude steel production data and localized emission factors classified by melting processes, while Tier 1 is based on total crude steel production data and the global average emission factors from World Steel Association and other European institutions3. We use the Tier 1 method for estimating the carbon emissions from other sectors. Furthermore, we calculate the provincial CO2 emissions from the IPPU sectors based on the updated provincial-level statistics.

The detailed methodology for calculating the CO2 emissions from each IPPU sector is presented in Supplementary Method in the Supplementary Information file. The CO2 emissions from the IPPU were calculated, using the following equation:

where \({{Emissions}}_{{IPPU}}\) represents the CO2 emissions from IPPU in China, \({{AD}}_{i}\) is the production of i industrial process, and \({{EF}}_{i}\) is the emission factor of each industrial process.

Notably, we use the activity data from the national and provincial statistical yearbooks, as detailed in Table S2. We collected data from several sets of official statistical yearbooks, including China Industry Statistical Yearbook46, Almanac of China Building Materials Industry40,49,50,51, National Bureau of Statistics42,52, China Mining Yearbook53, China Chemical Industry Yearbook54, China Steel Yearbook55, and China Lime Association’s public reports. We did our best to collect multiple data sets from various sectors, and selected the data sets which are the most continuous, complete, and consistent with sectors’ development as the basis for estimation. For example, we collected four data sets of cement and cement clinker production from China Cement Yearbook56, National Bureau of Statistics42,52, Almanac of China Building Materials Industry40,49,50,51, and China Industrial Statistical Yearbook46, respectively. Among them, the cement-related data from Almanac of China Building Materials Industry have the highest temporal continuity and are most consistent with the development of the cement industry. Therefore, this study selected data from Almanac of China Building Materials Industry when estimating IPPU emissions from cement production. All activity data are shown in Tables S11–S13. Table S8 lists all data sources. Tables S9 and S10 contain information on the emission factors considered in this study and the parameters used for uncertainty analysis in this study, respectively. The results of uncertainty analysis are shown in Tables S2−S7.

We do not include the minor emissions from the process uses of carbonates, ethylene dichloride, vinyl chloride monomer, hydrogen production, and rare earth, due to the lack of data. Based on the EDGAR estimates, the emissions from the carbonate processes accounted for less than 2% of the CO2 emissions from IPPU in 201814. Based on the data available in the yearbook for 2000, 2005, and 201152 and the IPCC guidelines, the total emissions from the production of ethylene dichloride and vinyl chloride monomer, which were indistinguishable from those from ethylene production, accounted for less than 1% of the CO2 emissions from IPPU in 2020; the CO2 emissions from the production of hydrogen and rare earth metals were less than 1% of the CO2 emissions from IPPU in the same year.

To quantify the uncertainties of our estimates, we conduct an uncertainty analysis of the CO2 emissions from the 18 industrial processes and 2 product uses, using the Monte Carlo approach. The distribution range of the emissions was assessed by applying the normal distribution to the activity data and the emission factors of 100,000 times. The available emission factors and uncertainties of the activity data were acquired from the 2006 and 2019 IPCC guidelines3,47, detailed in Tables S3–S4. The distribution ranges of the estimated emissions from each sector are presented in Tables S1.1–S1.6.

The mean annual growth rate in this paper refers to the compound annual growth rate (CAGR), and the formula is as follows:

where t1 represents the end year, and t0 represents the begin year.

Index decomposition analysis (IDA)

In this study, we employ index decomposition analysis (IDA) to quantify the driving forces of the emission changes from IPPU in China. Among specific IDA methodologies, the LMDI has been widely used because of its path independence, consistency in aggregation, and ability to handle zero values57,58. In the LMDI analysis, we compare a set of indexes between the base and final years of a given period and quantified the contribution of each indicator to the CO2 emissions from IPPU.

Notably, we decompose the CO2 emissions from the IPPU in China (C), using the following equation:

where \(C\) represents the CO2 emissions from IPPU in China; \({{GDP}}_{\sec }\) represents the GDP value added by the secondary industry which includes construction and industry; \({CA}\) represents the construction area, and the construction area refers to the total construction area constructed during the study period, including newly started construction area and completed area; \({POP}\) represents the population; \({C}_{{{\mathrm{int}}}}\) represents the carbon intensity (calculated as the IPPU emissions per unit of value added by the secondary industry); \({{CA}}_{{pop}}\) represents per capita construction area; \({{ECO}}_{{ca}}\) stands for the secondary industry’s value leveraged per unit of construction area. Thus, the change in the CO2 emissions from IPPU in year t compared with year t-1 was calculated, using the following equation:

The added values of the secondary industries and the data of the GDP and population were acquired from the China Statistical Yearbook52. GDP is adjusted to 2015 constant prices.

The decomposition factors used in this study to decompose the total IPPU emission, including CApop, ECOca, Cint and POP, have certain limitations, although the above indicators could represent the development of the construction and industry, which stimulated around 76% IPPU emissions (see data and calculation methods in detail in Supplementary Note 1 in Supplementary Information). The first limitation lies in the limitations of the LMDI method itself. Previous studies have extensively used the LMDI method based on the Kaya Identity to extend more decomposition factors to reveal the driving factors of greenhouse gas emissions32,33,34,45,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. However, here we believe that the LMDI decomposition method can only explain the correlation between the decomposition factors and carbon emissions, and cannot truly reveal the driving factors of carbon emissions. Our study is the same. Although we extended the LMDI decomposition factors based on the Kaya identity and tried to choose factors highly related to IPPU emissions, we can currently only show the correlation between each decomposition factor and IPPU emissions, but cannot explain their causal relationship. Secondly, the selection of decomposition factors has certain limitations. Although this study tried to choose factors highly related to IPPU emissions before selecting decomposition factors, there may still be some highly related decomposition factors that have not yet been discovered and need further exploration. There may be potential decomposition factors that have not yet been discovered, and their changes may be hidden in the factors we selected, such as CApop, ECOca, Cint or POP. Here, we call on more studies to begin to further explore the deep-seated reasons behind changing China’s IPPU emissions.

Data availability

All data sources and products that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information. The source data are available in the Figshare data repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27645762.v1.

References

Liu, Z. et al. Global patterns of daily CO2 emissions reductions in the first year of COVID-19. Nat. Geosci. 15, 615–620 (2022).

Liu, Z. National carbon emissions from the industry process: production of glass, soda ash, ammonia, calcium carbide and alumina. Appl. Energ. 166, 239–244 (2016).

IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Industrial Process and Product Use Vol. 3 (Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), 2006).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Third biennial update report on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/636696 (2023).

Guan, D., Hubacek, K., Weber, C. L., Peters, G. P. & Reiner, D. M. The drivers of Chinese CO2 emissions from 1980 to 2030. Glob. Environ. Chang. 18, 626–634 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. Reduced carbon emission estimates from fossil fuel combustion and cement production in China. Nature 524, 335 (2015).

Mi, Z. F. et al. Socioeconomic impact assessment of China’s CO2 emissions peak prior to 2030. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 2227–2236 (2017).

Ding, S., Xu, N., Ye, J., Zhou, W. & Zhang, X. Estimating Chinese energy-related CO2 emissions by employing a novel discrete grey prediction model. J. Clean. Prod. 259, 120793 (2020).

Guan, D. et al. Structural decline in China’s CO2 emissions through transitions in industry and energy systems. Nat. Geosci. 11, 551 (2018).

Guan, Y. et al. Assessment to China’s recent emission pattern shifts. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002241 (2021).

Shan, Y. et al. City-level emission peak and drivers in China. Sci. Bull. 67, 1910–1920 (2022).

MEPC. Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on the complete, accurate and comprehensive implementation of the new development concept to do a good job in carbon peak and carbon neutrality (in Chinese). Xinhuanet. https://www.mee.gov.cn/zcwj/zyygwj/202110/t20211024_957580.shtml (2021).

Cai, B. F. et al. Annual Report of China’s CO2 Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) (2021)—China CCUS Path Study (in Chinese) (Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Administrative Center for China’s Agenda 21, 2021).

Crippa, M. et al. EDGAR v8.0 greenhouse gas emissions. European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC) [Dataset]. http://data.europa.eu/89h/b54d8149-2864-4fb9-96b9-5fd3a020c224 (2023).

Yu, X. & Tan, C. China’s process-related greenhouse gas emission dataset 1990–2020. Sci. Data 10, 55 (2023).

Shan, Y. L. et al. Peak cement-related CO2 emissions and the changes in drivers in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 959–971 (2019).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Initial national communication on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/636695 (2004).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Second national communication on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/71515 (2012).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). First biennial update report on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/180618 (2016).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Second biennial update report on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/197666 (2018).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Third national communication on climate change. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. https://unfccc.int/documents/197660 (2018).

Crippa, M. et al. GHG Emissions of All World Countries (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Teng, F. S., Z. Which estimation is more accurate? A technical comments on Nature Paper by Liu et al on overestimation of China’s emission. Sci. Technol. Rev. 33, 112–116 (2015).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1917–2005 (2022).

Hu, H. (ed) China Building Materials Industry Yearbook (2021 Edition) (China Building Materials Industry Yearbook Editorial Department, 2021).

Pan, Z., Zhang, L. & Yang, W. Research on the supply and demand status and development trends of the domestic steel market from January to June 2020. China Acad. J. Electron. Publ. House 2020, 15–19 (2020).

Ding, T., Ning, Y. & Zhang, Y. Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions in China 1990–2013. Greenh. Gases: Sci. Technol. 7, 1097–1115 (2017).

Ke, J. Estimation of CO2 emissions from China’s cement production methodologies and uncertainties. Energ. Policy 57, 172–181 (2013).

Du, T. et al. CO2 emissions from the Chinese cement sector: analysis from both the supply and demand sides. J. Ind. Ecol. 24, 923–934 (2020).

Gilfillan, D. & Marland, G. CDIAC-FF: global and national CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement manufacture: 1751–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 1667–1680 (2021).

Huo, T. et al. Timetable and roadmap for achieving carbon peak and carbon neutrality of China’s building sector. Energy 274, 127330 (2023).

Jiang, P. et al. Research on spatial and temporal differences of carbon emissions and influencing factors in eight economic regions of China based on LMDI model. Sci. Rep. 13, 7965 (2023).

Luo, X., Liu, C. & Zhao, H. Driving factors and emission reduction scenarios analysis of CO2 emissions in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and surrounding cities based on LMDI and system dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 870, 161966 (2023).

Zhang, C., Su, B., Zhou, K. & Yang, S. Decomposition analysis of China’s CO2 emissions (2000–2016) and scenario analysis of its carbon intensity targets in 2020 and 2030. Sci. Total Environ. 668, 432–442 (2019).

National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). China Energy Statistical Yearbook (China Statistics Press, 2000–2020).

Mei, D. & Wang, J. Land finance, high housing prices, and China’s economic transition (in Chinese). World Econ. Rev. 3, 18–38 (2023).

Zhou, C., Huang, C. & Wang, J. Analysis of the reasons for rising housing prices in China from the perspective of stakeholders (in Chinese). China Collective Econ 32, 32–33 (2018).

He, S. Study on policy risks of real estate enterprises’ development under the background of economic crisis. Master’s thesis, Chongqing University of Technology (2013).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2015 National real estate development and sales situation. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1899021.html (2023).

Lei, Q. Almanac of China Building Materials Industry (China Architecture Publishing, 1997–2001).

Hou, L. Almanac of China Building Materials Industry (China Architecture Publishing, 2021).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. National data. https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (2024).

Janssens-Maenhout, G. et al. EDGAR v4.3.2 Global Atlas of the three major greenhouse gas emissions for the period 1970–2012. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 959–1002 (2019).

UNFCCC. Comparison by category. https://di.unfccc.int/comparison_by_category (2024).

Gong, T., Zhang, W., Liang, J., Lin, C. & Mao, K. Forecast and analysis of the total amount of civil buildings in China in the future based on population driven. Sustainability 24, 14051 (2021).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Industrial Statistical Yearbook (China Statistics Press, 2001–2020).

Calvo Buendia, E. et al. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC, 2019).

National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Guidelines for provincial greenhouse gas inventories. http://www.cbcsd.org.cn/sjk/nengyuan/standard/home/20140113/download/shengjiwenshiqiti.pdf (2011).

Lei, Q. Almanac of China Building Materials Industry (China Architecture Publishing, 2009).

Lei, Q. Almanac of China Building Materials Industry (China Architecture Publishing, 2011).

Lei, Q. Almanac of China Building Materials Industry (China Architecture Publishing, 2017–2019).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2020 (China Statistics Press, 2021).

China Mining Yearbook Editorial Department. China Mining Yearbook (Seismological Press, 2001–2017).

China Chemical Industry Information Association. China Chemical Industry Yearbook (China Chemical Industry Information Association, 2001–2020).

The Editorial Board of China Steel Yearbook. China Steel Yearbook. (Metallurgical Industry Press, 2001–2020).

China Cement Association (CCA). China Cement Almanac (China Building Materials Press, 2001–2015).

Ma, C. & Stern, D. I. China’s changing energy intensity trend: a decomposition analysis. Energ. Econ. 30, 1037–1053 (2008).

Wang, Z., Feng, C., Chen, J. & Huang, J. The driving forces of material use in China: an index decomposition analysis. Resour. Policy 52, 336–348 (2017).

Kopidou, D., Tsakanikas, A. & Diakoulaki, D. Common trends and drivers of CO2 emissions and employment: a decomposition analysis in the industrial sector of selected European Union countries. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 4159–4172 (2016).

Ma, M. & Cai, W. What drives the carbon mitigation in Chinese commercial building sector? Evidence from decomposing an extended Kaya identity. Sci. Total Environ. 634, 884–899 (2018).

Ortega-Ruiz, G., Mena-Nieto, A. & García-Ramos, J. E. Is India on the right pathway to reduce CO2 emissions? Decomposing an enlarged Kaya identity using the LMDI method for the period 1990–2016. Sci. Total Environ. 737, 139638 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Driving forces of China’s CO2 emissions from energy consumption based on Kaya-LMDI methods. Sci. Total Environ. 711, 134569 (2020).

Duan, Y. et al. Agricultural methane emissions in China: inventories, driving forces and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 13292–13303 (2023).

Abam, F. I., Inah, O. I. & Nwankwojike, B. N. Impact of asset intensity and other energy-associated CO2 emissions drivers in the Nigerian manufacturing sector: a firm-level decomposition (LMDI) analysis. Heliyon 10, e28197 (2024).

Yao, L., Qian, W. & Jiang, H. Spatial-temporal distribution and multiple driving mechanisms of energy-related CH4 emissions in China. Environ. Impact Asses 106, 107463 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yahui Sun, Qianna Du and Di Chen for their help in checking the data and ensuring its accuracy at the final stage of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Zhu Deng for his oral suggestions on the manuscript. The authors are grateful for the support of the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2022C03154), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFE0209100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xuekun Fang designed this study; Liting Hu performed the data calculations, analyzed the data, created the graphs, and wrote the manuscript; Liting Hu, Xiaoyi Hu, Bowei Li, Liya Guo, Di Chen, Yang Yang, Mengyue Ma, Xinhe Li, Rui Feng, Xuekun Fang contributed to manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Jan Ivar Korsbakken, Yuli Shan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Pallav Purohit and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, L., Hu, X., Li, B. et al. Carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes and product use are a non-ignorable factor in China’ s mitigation. Commun Earth Environ 5, 800 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01951-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01951-1

This article is cited by

-

Boosted mass transfer and water tolerance in CO2 cycloaddition via hierarchically porous PVMDMS@PVP aerogel containing in-situ grown UiO-66-NH2

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2026)

-

City-level process-related CO2 emissions in China 2000–2021

Scientific Data (2025)