Abstract

In the subtropical monsoon region of China, the climate differs from that of most northern peatlands, where many peatlands have developed in mountainous areas. However, it remains unclear how the carbon dynamics of these subtropical peatlands respond to climate change. Here, we reconstructed the net carbon fluxes of a typical mountainous peatland in Tianmu Mountain, eastern China, over the past thousand years. Humidity and winter temperature are two important climatic factors influencing carbon accumulation (Deviance explained 77.2%) and drought promotes Qianmutian peatland initial development. Despite the decline in carbon accumulation over the last millennium, the peatland’s net carbon balance remains in a ‘carbon sink’ state. This suggests that the risk of carbon release from the peatland carbon pool under natural climate change conditions is not substantial in the subtropical monsoon area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peatlands account for only 3 to 4% of the global land area, but their carbon pool accounts for one-third of the global soil carbon pool, storing about 400–600 Gt carbon1,2,3,4. The formation of carbon pools in peatlands is intricately governed by the interplay of vegetation production and decomposition processes. Peat accumulation occurs when the rate of production exceeds the rate of decomposition5. Climate profoundly influences the thermal and humidity conditions experienced by peatlands, consequently shaping the dynamics of plant organisms6,7and microbial communities within these ecosystems, which have an impact on the carbon accumulation in peatlands. The response of peatland’s carbon accumulation to temperature and precipitation patterns is linked to the future trajectory of carbon pools within these environments.

On a millennial scale, the most notable carbon accumulation in northern peatlands occurred during the early Holocene, a period characterized by gradually rising temperatures8,9. On a centennial scale, temperature has had a stronger promoting effect on primary productivity compared to peat decomposition over the past millennium10. This is evidenced by higher carbon accumulation rates during the Medieval Warm Period compared to the Little Ice Age11. These findings indicate that historical warm periods generally enhanced the rate of carbon accumulation in northern peatlands. In contrast, the climatic conditions for peatland formation and development in the low-medium elevation mountains of the subtropical monsoon region of China are very different from those in northern peatlands. This region experiences high temperatures and abundant precipitation12. The increase in carbon accumulation rates observed in the Dahu, Lantianyan, and Zhaogongting peatlands in eastern China’s subtropical region correlates positively with gradually arid climatic conditions12,13,14,15. During the mid-Holocene, carbon accumulation rates peaked in Dahu peatland due to arid climatic conditions, which inhibited peatland development. Terrestrial and nearshore aquatic vegetation encroached upon central areas, resulting in an increase in organic matter content16. Similarly, the Zhaogongting peatland experienced notable increases in carbon accumulation during the mid-Holocene due to declining water levels under dry conditions, and it is thought that the arid environment enhanced organic matter accumulation15. Research in Dajiuhu suggested that short-term rapid hydrological fluctuations promote carbon accumulation, whereas long-term drought leads to intensified peat decomposition and decreased carbon accumulation17. Synthesized data from peatland resource surveys conducted in the 1980s found that peaks of carbon accumulation in subtropical peatlands were predominantly observed during the Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3) and the Bølling-Allerød warm period, characterized by high solar radiation and intensified summer monsoons18. Thus, it is evident that there are varying perspectives among different studies regarding carbon accumulation variations and their mechanisms in subtropical peatlands. The influence of climatic factors, such as temperature and precipitation, on peat carbon accumulation in subtropical regions remains incompletely understood.

Over the past 1000 years, the fundamental boundary conditions of Earth’s climate, including factors such as land-sea distribution, topography, and orbital parameters, have remained relatively stable, providing a suitable backdrop for elucidating contemporary climate change trends. A large number of paleoclimate reconstruction and climate modeling studies have been carried out in the subtropical monsoon region of China. Historical and instrumental reconstructions of the climate of the Jianghuai region of China over the past millennium suggest an increasingly humid climate19. Additionally, a significant increase in precipitation in central-eastern China20, a trend supported by a*/L* based on sediments from Nanyi Lake21. This trend has also been confirmed by diatom-based analyses22, grain size analyses23and magnetic analyses24. Regarding the temperature variations, ref. 25 discovered through an analysis of the ECHO-G model that the temperature in the East Asian monsoon region of China exhibited fluctuations of “warmth-coldness-warmth” over the last millennium, which is consistent with the reconstruction results26. There is a basic consensus pattern of gradually humid climate in the subtropical monsoon region over the last millennium. Therefore, understanding the historical relationships between carbon accumulation and climate factors over the past millennium is feasible, and will be instrumental in predicting the dynamics of carbon pools in peatlands under various climate change scenarios in the future.

Here, we utilized two meticulously dated and high-resolution net carbon accumulation records obtained from a mountain peatland, Qianmutian (QMT) peatland (Fig. 1), to investigate the response of carbon accumulation to climatic fluctuations over the past millennium within the subtropical monsoon region. The study aims to achieve two primary objectives: (1) reconstructing the peatland’s evolutionary history and (2) establishing correlations between observed shifts in carbon dynamics and variations in temperature and precipitation patterns over the last millennium in the subtropical monsoon region. Through the examination of the nexus between carbon accumulation and climatic factors, we hope our study can contribute to the assessment of the scale and direction of future global carbon cycle feedback.

a Elevation map of the subtropical monsoon zone of China showing the location of the study sites, black differently shaped points are the locations of the study sites for the collected climate background data, and this study is marked with a red star. The colors represent elevations (m a.s.l.) as shown in the color bars right. The black arrow in the upper right corner indicates the direction of the East Asian monsoon, while the red dashed line represents the northern boundary of the East Asian monsoon48. b Satellite image of the QMT peatland (source from Google Earth), the white line is counter. c Close-up view of the QMT peatland.

Results

Lithostratigraphy and chronology

The surface layer of core QMT22-1 from QMT peatland, spanning 1–25 cm, constitutes the acrotelm and supports living fresh moss. From 25 to 117 cm, the core transitions into the catotelm, characterized by distinct layers: 25–35 cm consists of plant roots and humus, exhibiting weak decay; 35–55 cm comprises high humic sediments; and 55–117 cm is filled with yellow-brown mud, culminating in rock at the bottom (Fig. 2a). Similarly, in core QMT22-2, the acrotelm extends from the surface to a depth of 35 cm, cohabited by fresh moss. The subsequent 35–93 cm constitutes the catotelm, featuring distinctive layers: 35–50 cm comprises high humic sediments, while 51–93 cm is filled with yellow-brown mud exhibiting lower decomposition, ultimately concluding with rock at the base (Fig. 2b).

Based on the observed variations in dry bulk densities (DBD) and loss on ignition (LOI) observed in the sediment cores QMT22-1 and QMT22-2, four distinct sedimentary sections can be identified (Supplementary Fig. 3). The first segment, spanning depths of 13–39 cm in QMT22-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) and corresponding to 13–40 cm in QMT22-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), displays the highest DBD and LOI values within the entire catotelm layer, with a rapid decrease observed around 39 and 40 cm, respectively. The second segment covers depths of 39–73 cm in QMT22-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) and 40–56 cm in QMT22-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). In this segment, DBD variations remain relatively stable, while LOI values consistently increase with depth, abruptly decreasing around 73 and 56 cm. The third segment encompasses depths of 73–93 cm in QMT22-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) and 57–71 cm in QMT22-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), showing a declining trend in both DBD and LOI with increasing depth. The fourth segment, spanning depths of 93–117 cm in QMT22-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) and 71–93 cm in QMT22-2 (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), exhibits significant fluctuations in DBD without a clear increasing or decreasing trend, while LOI remains stable within this sedimentary segment. Consequently, we can establish the age depths of core QMT22-1 through core QMT22-2. Supplementary Fig. 3 illustrates that for core QMT22-2, samples from depths of 24, 45, 67, and 93 cm were selected to determine ages. For QMT22-1, we determined the relative positions of age depths based on lithological characteristics. The first age-depth is estimated at 23 cm, the second at 49 cm, the third at 86 cm, and the basal age-depth at 117 cm (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). The basal ages of cores QMT22-1 and QMT22-2 are both estimated at 1160 ± 20 yr 14C BP (Table 1). Subsequently, using the R language, we established the chronology.

Plant macrofossils

Figure 3 presents the plant macrofossil identifications within the sedimentary sequence of the QMT peatland over the past millennium. Cluster analysis of the plant macrofossils identified three primary zones.

Zone 1 (~117 BP) is characterized primarily by Sphagnum Palustre and Scirpus triqueter, Drepanocladus aduncus also present but concentrated near the surface rather than throughout the zone. In addition, small amounts of Polytrichum juniperinum, Eriophorum vaginatum, and Calamagrostis epigejos are found at specific depths.

Zone 2 (117–315 BP) is predominantly characterized by Scirpus triqueter, while Sphagnum Palustre and Drepanocladus aduncus nearly disappear from this layer. Eriophorum vaginatum begins to increase in abundance, and Juncus effusus seeds also occur in abundance in certain locations within the zone.

Zone 3 (315–1006 BP) is primarily dominated by Scirpus triqueter, followed by Sphagnum Palustre, Eriophorum vaginatum, and Aulacomnium palustre. Additionally, Polytrichum juniperinum and Drepanocladus aduncus are distributed in specific locations within this zone. Furthermore, Myrica gale, Ericaceae, and Vaccinium also appear at particular sites throughout the region.

Carbon accumulation dynamics

As the acrotelm is inhabited by fresh moss, this study solely focuses on the catotelm. In the catotelm of core QMT22-1, the peat-addition rate is determined to be 123.5 g OM m-2 yr-1, with a peat-decomposition rate of 0.0008 yr-1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Meanwhile, in core QMT22-2, the peat-addition rate is 67.8 g OM m-2 yr-1, with a peat-decomposition rate of 0.0005 yr-1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Upon determining the peat decomposition rate (α), further calculations of the net carbon uptake (NCU), net carbon release (NCR), and net carbon balance (NCB) were conducted using the “super-peatland” approach. For core QMT22-1, the calculated NCU ranges from 40.79 to 82.82 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 62.19 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4). The observed carbon pool (NCP) ranges from 25.51 to 59.45 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 41.57 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4). Additionally, NCR ranges from 1.38 to 35.11 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 20.63 g C m-2 yr-1, resulting in NCB ranging from 5.68 to 81.44 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4). Notably, these values are substantially higher compared to those of core QMT22-2. Specifically, the NCU of core QMT22-2 ranges from 26.20 to 52.51 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 34.55 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4). The NCP ranges from 18.40 to 35.17 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 27.35 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4). Moreover, NCR varies from 0.51 to 12.80 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 7.21 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4), leading to NCB ranging from 13.41 to 51.99 g C m-2 yr-1, with an average of 27.35 g C m-2 yr-1 (Fig. 4).

The net carbon uptake (NCU) represents the average annual peat carbon flux over the past 1000 years, the net carbon pool (NCP) represents apparent peat stock as observed from the peatland core, the net carbon release (NCR) represents the summed carbon release of all peat cohorts over time. The net carbon balance (NCB, black dots) was calculated as the difference between NCU and NCR. The smoothed lines are five-point moving averages (green line).

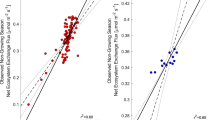

Models of net carbon accumulation rate and climate factors

The Akaike information criterion (AIC) of generalized additive models (GAM): NCB = s(SO) (Supplementary Fig. 3a), NCB = s(NT) (Supplementary Fig. 3b), NCB = s(ET) (supplementary Fig. 3c), NCB = s(WT) (Supplementary Fig. 3d), NCB = s(ST) (Supplementary Fig. 3e), NCB = s(MO) (Supplementary Fig. 3f), NCB = s(SO) + s(MO) (Supplementary Fig. 4), NCB = s(ET) + s(MO) (Supplementary Fig. 5), NCB = s(WT) + s(MO) (Fig. 5) and NCB = s(ST) + s(MO) (Supplementary Fig. 6) was 321, 304, 314, 314, 306, 282, 277, 279, 273, and 282. Thus, the final GAM is NCB = s(WT) + s(MO), and this model explained 77.2% of the variance of the NCB. The winter temperature and humidity were important meteorological parameters for NCB.

Discussions

Characteristics of solar radiation, temperature, humidity, and pant macrofossils

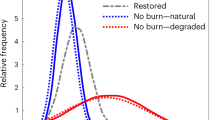

Solar radiation at 30°N latitude has shown a fluctuating decline since the last millennium until ~600 years BP, after which it began a fluctuating upward trend (Fig. 6a). However, the overall changes remain minimal. Annual mean temperature anomalies in the Northern Hemisphere have undergone notable shifts, with a decreasing trend from the last millennium up until around 400 years BP, followed by an increasing trend from 400 years BP to the present (Fig. 6b, c). In the subtropical monsoon region of China, annual mean temperature anomalies, as well as summer and winter temperature anomalies, exhibited an upward trend until ~700 years BP, after which they showed a fluctuating decline (Fig. 6d, e). Notably, both winter and summer temperatures increased sharply around 1000 to 900 years BP (Fig. 6d, e). Regarding humidity index changes from 1200 to 800 years BP, some records suggest a gradual decline in humidity, while others indicate an increase (Fig. 6f). However, from 800 years BP to the present, all indicators consistently suggest a gradual rise in humidity, with levels around 600 years BP exceeding those around 1000 years BP (Fig. 6f). Z-score calculations across various humidity indicators reveal a clear trend of increasing humidity in the subtropical monsoon region of China over the past millennium (Fig. 6f).

a 30°N solar irradiance33. b North hemisphere annual temperature anomaly35. c Central East China annual temperature anomaly26. d Winter annual temperature anomaly of east China49. e Summer annual temperature anomaly of east China36. f The dark blue line is the composite z-score of the data for different humidity indicators in eastern China, and the sky-blue shading is the margin of error. g this study, the NCB is average for the core QMT22-1 and QMT22-2, short-term error bars.

Plant macrofossil identifications from QMT peatland over the past millennium indicate that Polytrichum juniperinum steadily declined since the initial development of QMT peatland, disappearing around 630 BP (Fig.3). Aulacomnium palustre showed a gradually increasing trend up until approximately 570 BP (Fig. 3). The relative abundances of herbaceous species Scirpus triqueter and Eriophorum vaginatum continued to increase until around 315 BP (Fig. 3). Additionally, woody species Vaccinium appeared and showed a slight increase before approximately 550 BP (Fig. 3), suggesting that early QMT development coincided with a progressively drying environment.

Peatland development in the subtropical monsoon region over the past millennium

The QMT peatland was initially formed at ~1063 yr BP, Given that the QMT peatland in Tianmu Mountain is located in a low-lying area, it acts as a catchment area. QMT has runoff input, their water source is ultimately precipitation or the small watersheds to the peatland, the water level in peatland likely reflects regional humidity balance and regional climate because of a very small watershed. GAMs (Generalized Additive Models) analysis indicates that winter temperature and humidity are the primary climatic factors influencing carbon accumulation in the QMT peatland. Less early precipitation resulted in less standing water in the QMT depression. At the same time, higher winter temperatures extended the growing season for vegetation and produced more litter, causing the terrestrialization of the water area and the initiation of peatland. Therefore, it is mainly the lower level of humidity and higher winter temperature that triggered the initiation of the QMT peatland in the subtropical monsoon region.

The QMT22-1 core is 24 cm deeper than the QMT22-2 core, indicating potential variations associated with the microtopography of peatland development. Peatland development typically progresses through three distinct stages27: the initial phase, characterized by various water sources and rapid peat accumulation, is termed “lowmoor”, the final stage where the peat layer thickens and peat accumulation decreases is known as “highmoor”, with rainfall being a major source of recharge. The transitional stage between lowmoor and highmoor is termed “mesomoor”. Although both QMT22-1 and QMT22-2 cores were collected from the same peatland, due to the higher landform, the QMT22-2 core can transition to the highmoor stage earlier than QMT22-1 in the stages of peatland development (Fig. 2). When QMT22-2 reaches the highmoor stage, surface vegetation primarily relies on rainfall for replenishment, inhibiting peat accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 8). Meanwhile, the QMT22-1 core was still in the mesomoor stage, receiving recharge not only from rainfall but also influenced by peatland water levels, maintaining a high rate of peat accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 8). The different sediment thicknesses caused by the different micro-geomorphic heights in the same peatland prove the role of water in the development of peatland over the last millennium.

Impacts of climate factors on QMT peatland carbon fluxes over the past millennium

The GAMs model shows that Winter temperature and humidity significantly impact the NCB of the QMT peatland (Fig. 5). If the winter temperature anomaly is greater than −0.2, winter temperature is negatively correlated with NCB (Fig. 5). If the winter temperature index is less than −0.2, winter temperature is positively correlated with NCB (Fig. 5). Humidity indexes and NCB are negatively correlated when the humidity indicator is greater than −0.5, and positively correlated when the humidity indicator is less than −0.5 (Fig. 5). As each plant has its own suitable ecological niche28, vegetation growth in peatlands above this ecological niche is inhibited. Over the last thousand years, NCB has been positively correlated with the winter temperature anomaly (<−0.2) and negatively correlated with the humidity index (>−0.5) for most of the period (700 BP~) in QMT peatlands (Fig. 6f, g). When the winter temperature decreases, the length of the growing season for vegetation is shortened, resulting in reduced litter production and lower carbon accumulation. As humidity continues to increase, it leads to higher water levels in peatlands, which tends to accumulate more water on the surface, and peatland vegetation is flooded for a long period of time, inhibiting the production of vegetation, which produces less litter and leads to less carbon accumulation.

Since the annual average temperature, summer temperature, and winter temperature are basically similar in their changing trends, these parameters also have a strong correlation with NCB. However, the structure of the GAMs proves that the combination of winter temperature anomaly and humidity index has the strongest impact on NCB. Other climate parameters, such as solar radiation, have no correlation with NCB. It can be seen from this that winter temperature and humidity were the main climatic factors controlling the carbon accumulation in peatlands during the last thousand years.

Over the last millennium, the humidity index in the eastern subtropical monsoon zone of China has generally increased, while the winter temperature anomaly has tended to decrease, resulting in a general decline in the NCB of the QMT peatlands (Fig. 6d, f, g). Although the responses of NCB to different ranges of winter temperature and humidity indices were not consistent, NCB was positively correlated with the winter temperature anomaly and negatively correlated with the humidity index for most of the period since 1000 BP (Fig. 6d, f, g). As winter temperatures decreased, the growing season for peatland vegetation shortened, suppressing litter production and leading to a lower carbon accumulation rate (Fig. 7, and Supplementary Fig. 9). Increased humidity raised water levels in the peatlands, causing more surface water accumulation and prolonged flooding of peatland vegetation, which hindered vegetation growth and reduced litter production, further decreasing the carbon accumulation rate (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Thus, a cold and humid climate has been the primary factor influencing the decrease in carbon accumulation in the QMT peatland.

After the formation of the QMT peatland, it has consistently presented as a carbon sink. However, the net carbon balance of the peatland shows a downward trend since 1063 cal yr BP, yet still in the state of a carbon sink (Fig. 6g). Therefore, the carbon release risk of the mountainous peatland carbon pool in the subtropical monsoon area is not large under the change of the natural environment.

Different climate-carbon accumulation patterns in subtropical monsoon regions compared to other peatlands globally

From a global perspective, carbon accumulation in northern peatlands is primarily driven by temperature, with higher temperatures promoting carbon accumulation9,10. In contrast to northern peatlands, tropical peatlands are affected by summer monsoon intensity, sea-level change, and El Niño intensity3. Meanwhile, carbon accumulation in southern peatlands, primarily located in Patagonia, South America, is predominantly regulated by water balance29. It is clear that the factors that control the accumulation of carbon in peatlands vary considerably from region to region.

Peatlands in the subtropical monsoon region belong to a subset of northern peatlands in terms of classification. However, the climatic mechanisms driving variations in carbon accumulation in subtropical peatlands differ from those in northern peatlands. In the early stage, less precipitation in the subtropical monsoon region led to a reduction in water levels in the depressions of low and medium mountains. At the same time, the higher winter temperature during that period prolonged the growing season of vegetation and increased the amount of litter. This was conducive to the terrestrialization of the water area and thereby promoted the development of peatland in this area.

Analyses of carbon fluxes in the peatland showed that changes in winter temperature anomaly and humidity index have primarily controlled carbon accumulation in the peatlands over the past millennium. The gradual cooling and increase in humid over the past thousand years have reduced the rate of carbon accumulation. Lower winter temperatures shorten the length of the growing season of peatland vegetation, leading to a decrease in litter and a lower rate of carbon accumulation. A gradual increase in humidity led to the accumulation of more water in the surface layer of peatlands, which is detrimental to the growth of surface vegetation. This reduces net primary productivity, decreases litter, and consequently reduces net carbon accumulation.

Conclusions

In the subtropical monsoon region, drought and higher winter temperatures are conducive to the development and carbon accumulation of peatlands (The AIC value is 273, explaining 77.2% of the variance). Reduced precipitation lowers water levels in depressions of the mountains. Meanwhile, higher winter temperatures extend the vegetation growing season, increasing litter production and facilitating the terrestrialization of water areas, thereby promoting peatland development and carbon accumulation in this region. Over the past thousand years, carbon accumulation in the QMT peatland has declined due to gradual decreases in winter temperatures and increases in humidity. Reduced winter temperatures have shortened the vegetation growing season, leading to decreased litter production and carbon accumulation. Increased humidity has raised peatland water levels, reducing vegetation productivity and causing a decline in carbon accumulation. Despite the decline in carbon accumulation over the last millennium, the peatland’s net carbon balance remains in a ‘carbon sink’ state. This suggests that the risk of carbon release from the peatland carbon pool under natural climate change conditions is not substantial in the subtropical monsoon area.

Material and methods

Study site and fieldwork

The QMT peatland is situated in the eastern region of China (30.4994°N, 119.4408°E), at an altitude of approximately 1300 m above sea level (m a.s.l.) (Fig. 1a). It is located within a typical warm and humid monsoon climate zone characterized by abundant insolation relative to higher latitudes, elevated mean annual temperatures, and notable summertime warmth. Winter temperatures typically remain above 0 °C, with monsoon precipitation concentrated primarily in the summer season, often accompanied by frequent thunderstorms and other extreme meteorological phenomena. Specifically, the mean annual temperature in this region averages around 9.5 °C, annual precipitation is 1500 mm.

The QMT peatland, covering approximately 0.7 km2, is situated in a depression atop Tianmu Mountain (Fig. 1b). The surface vegetation is dominated by Sphagnum junghuhnianum and Sphagnum palustre (Fig. 1c). Accompanying with other plant species, such as Idesia polycarpa, Ligularia fischeri, Rubus trianthus, Rubus peltatus, Calamagrostis epigejos, Scirpus lushanensis, and Miscanthus sacchariflorus. In the surrounding upland vegetation, Cornus officinalis, Idesia polycarpa, and Viburnum opulus subsp. Calvescens are the dominant tree and shrub species.

In November 2022, we retrieved two peat cores, QMT22-1 (117 cm) and QMT22-2 (93 cm), using both box corer and Russian peat corer methods. For QMT22-1, we initially hand-excavated the surface layer from 0–47 cm before employing a box corer to extract a peat core spanning 0–97 cm. Subsequently, we attempted a second drilling session using the Russian peat core method to target depths of 64–117 cm; however, drilling was halted upon encountering gravel at the bottom. Similarly, for QMT22-2, we hand-excavated the surface layer from 0 to 38 cm and then employed a Russian peat core to extract the first core from 20–70 cm in depth. A subsequent drilling session aiming at depths of 43–93 cm was attempted, but drilling was again halted due to encountering gravel at the bottom. Following collection, the peat cores were placed into polyvinylchloride (PVC) pipes and transported back to the laboratory, where they were stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

14C dating

We collected samples from the QMT peatland using a Box peat corer and a Russian peat corer, resulting in QMT22-1 (117 cm) and QMT22-2 (93 cm). Samples from QMT22-2 at depths of 24 cm (stem and leaf), 45 cm (stem), 67 cm (stem), and 93 cm (stem) underwent accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon (14C) dating at the 14C Chronology Laboratory of Lanzhou University. Considering the close proximity and similar climatic context of the QMT22-1 and QMT22-2 cores, their stratigraphic positioning can be readily discerned based on their DBD and LOI values. Based on the depth of the dating points in the QMT22-2 core, the corresponding locations of the dating points in the QMT22-1 core can be inferred accordingly. Then, we used the R software (v 4.3.2) with the package rbacon (v 1.9-0) constructed an age-depth model30. The results were given in years before the present (BP), where “present” is defined as the year 1950 Common Era (CE).

Acrotelm/catotelm boundary detection

The peatland sediment layers comprise the acrotelm and catotelm. The acrotelm is rich in fresh litter and has a high organic matter content. However, due to the rapid decomposition of organic matter in this layer, the surface carbon accumulation rate, based on LOI, is higher than the earlier carbon accumulation rate. Therefore, this study will focus exclusively on the catotelm sedimentary layer. The catotelm and acrotelm represent two distinct layers distinguished by their physical properties and functions31. In QMT22-1 and QMT22-2, the differentiation between the acrotelm and catotelm is evident from lithological variations observed in the cores (Fig. 2). In QMT22-1, the upper layer spanning 1–25 cm exhibits brown-yellow sediment with low decomposition levels, abundant plant roots, and a relatively loose structure (Fig. 2a). Water content and LOI remain stable within this layer. Beyond 25 cm, the color gradually darkens to dark brown, accompanied by increased decomposition levels, rapid declines in water content and LOI, and the presence of underlying rocks (Fig. 2a). Consequently, the upper layer (1–25 cm) is identified as the acrotelm, comprising living fresh moss, while the subsequent layer (25–117 cm) is recognized as the catotelm (Fig. 2a). Similar changes are observed in the QMT22-2 core at a depth of 35 cm, where the upper layer (1–35 cm) exhibits brown-yellow sediment, dense plant root systems, and a loose structure, with stable water content and LOI levels (Fig. 2b). Below 35 cm, the color transitions from brown-yellow to black-brown, accompanied by rapid decreases in water content and LOI, increased decomposition levels, and the presence of underlying rocks (Fig. 2b). Hence, the upper layer (1–35 cm) in QMT22-2 is identified as the acrotelm, comprising living fresh moss, while the subsequent layer (35–93 cm) is classified as the catotelm (Fig. 2b).

Plant macrofossils analysis

The analysis of plant macrofossils employed quadrat and leaf count methods32 to determine the succession of plant communities within sediment layers. Fresh peat samples of 5 cm³ were taken at 1 cm intervals from core QMT22-1. Each sample was treated with a 5% NaOH solution for 12 h to remove humic and fulvic acids, then sieved through a 125-μm mesh and rinsed with distilled water until the rinse water was colorless. The washed plant remains were transferred to a petri dish, where a 10 × 10 counting grid was placed under a stereomicroscope. The petri dish was randomly moved to different fields of view, recording the percentage of each plant species within each view. The average percentage across all views was then calculated for each species to represent its overall proportion in the sample. The plant macrofossil diagram was generated using R software (v 4.3.2) with the rojia (v 1.0-6) and vegan (v 2.6–4) packages.

Climate data integration

In investigating past climate changes over the last millennium in the subtropical monsoon region, researchers have leveraged various archives and proxies. These include solar radiation33, temperature26,34,35,36, To indicate humidity changes, we collected several indicators, including a*/L*20, Rb/Sr21, mean size23, TOC37, and DPC-122 from lake sediments; SIRM24 and precipitation38 from peatland sediments; Total organic carbon (TOC)39 and freshwater species40 from offshore sediments; and a humidity index19 based on instrumental stations and historical records in southern China (Supplementary Table 1). The climate data used in this paper are published and peer-reviewed. When analyzing the correlation between humidity data and the NCB, we integrated the z-score values of these humidity records (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Carbon measurements and modeling

The cores QMT22-1 and QMT22-2 were sliced into contiguous sections, each 1 cm thick, and subsequently measured. These samples underwent drying at 105 °C for 12 h to ascertain their DBD, defined as the ratio of dry weight to volume. A subset of the dried subsamples underwent combustion at 550 °C in a muffle furnace for 4 h to determine the LOI, serving as an indicator of organic matter content (OM)41. To calculate the organic carbon content42, the OM was multiplied by 50%43. Based on the chronologies and the measured DBD (g cm−3) and organic carbon (OC)44, the peat aCAR was calculated as:

where t (yr) is the time experienced by peat thickness h (cm).

Upon obtaining the LOI data from the QMT peatland, we apply the decomposition model45 to derive the peat-addition rate (ρ) and peat-decomposition rate (α), where M represents the organic matter, and t signifies time.

Subsequently, employing the “super-peatland” methodology, we determine the net carbon fluxes of the QMT22-1 and QMT22-2 cores, encompassing NCU, NCR, and NCB, with α derived from the modeled decomposition46. The NCP enables the calculation of NCU for each 20-year interval, treating NCU as the initial mass and NCP as the remaining mass after time t. This equation is formulated as follows:

At a specific 20-year interval (k), the NCR is calculated. Therefore, the NCR at time t comprises the cumulative carbon release during that period from all peat cohorts older than time t. The carbon release during the 20-year period at time t can be determined by subtracting the potential NCU at time t from that at time t − 1. The equation can be expressed as follows:

NCB was calculated as the difference between NCU and NCR as derived above

Regression models

GAMs is a type of regression model that utilizes smoothing splines instead of linear coefficients for covariates47. The aim of using GAMs is to establish the connection between NCB and climate factors in the QMT peatland. The ultimate model was selected based on the lowest AIC. The GAMs analysis was generated using R software (v 4.3.2) with the package mgcv (v 1.9-0).

Data availability

All carbon flux and 14C data from QMT peatland are available in the online database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27908988.v2) and on request.

Code availability

The R packages covered in this article are free and open source and do not contain custom code.

References

Davidson, E. A. & Janssens, I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006).

Page, S. E., Rieley, J. O. & Banks, C. J. Global and regional importance of the tropical peatland carbon pool. Glob. Chang. Bio. 17, 798–818 (2011).

Yu, Z., Loisel, J., Brosseau, D. P., Beilman, D. W. & Hunt, S. J. Global peatland dynamics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 1–5 (2010).

Programme, U. N. E. Global Peatlands Assessment- The State of the World’s Peatlands: Evidence for action toward the consevation, restoration, and sustainable management of peatlands. United Nations Environment Programme (2022).

Gorham, E. The development of peat lands. Quart. Rev. Biol. 32, 145–166 (1957).

Cong, J. et al. Historical chemical stability of carbon pool in permafrost peatlands in northern Great Khingan Mountains (China) during the last millennium, and its paleoenvironmental implications. CATENA 209, 105853 (2022).

Cong, J. et al. Changes in organic matter properties and carbon chemical stability in surface soils associated with changing vegetation communities in permafrost peatlands. Biogeochemistry 163, 139–153 (2023).

Chaudhary, N. et al. Modelling past and future peatland carbon dynamics across the pan-Arctic. Glob. Chan. Bio. 26, 4119–4133 (2020).

Loisel, J. et al. A database and synthesis of northern peatland soil properties and Holocene carbon and nitrogen accumulation. Holocene 24, 1028–1042 (2014).

Charman, D. J. et al. Climate-related changes in peatland carbon accumulation during the last millennium. Biogeosciences 10, 929–944 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Anthropogenic warming reduces the carbon accumulation of Tibetan Plateau peatlands. Quat. Sci. Rev. 281, 107449 (2022).

Zhou, W. et al. High-resolution evidence from southern China of an early Holocene optimum and a mid-Holocene dry event during the past 18,000 years. Quat. Res. 62, 39–48 (2004).

Yu, X. et al. Anti-phase variation of hydrology and in-phase carbon accumulations in two wetlands in Southern and Northern China since the last deglaciation. Front. Earth Sci. 8 (2020).

Ma, T., Tarasov, P. E., Zheng, Z., Han, A. & Huang, K. Pollen- and charcoal-based evidence for climatic and human impact on vegetation in the northern edge of Wuyi Mountains, China, during the last 8200 years. Holocene 26, 1616–1626 (2016).

Huang, X. et al. Holocene forcing of East Asian hydroclimate recorded in a subtropical peatland from southeastern China. Clim. Dynam. 60, 981–993 (2023).

Wei, Z. et al. Carbon accumulation in Dahu Swamp in the eastern Nanling Mountains (south China) and its implications for hydroclimatic variability over the past 47 000 years. Boreas 47, 469–480 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. The response of the Dajiuhu Peatland ecosystem to hydrological variations: Implications for carbon sequestration and peatlands conservation. J. Hydrol. 612, 128307 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Peatland initiation and carbon accumulation in China over the last 50,000 years. Earth Sci. Rev. 128, 139–146 (2014).

Zheng, J., Wang, W. C., Ge, Q.-s, Man, Z. & Zhang, P. Precipitation variability and extreme events in eastern China during the past 1500 years. Terr. Atoms. Ocean. Sci. 17, 579–592 (2006).

Jiang, S. et al. Central eastern China hydrological changes and ENSO-like variability over the past 1800 yr. Geology 49, 1386–1390 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Dipolar mode of precipitation changes between north China and the Yangtze River Valley existed over the entire Holocene: evidence from the sediment record of Nanyi Lake. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 1667–1681 (2020).

Wang, L.-C. et al. Increased precipitation during the Little Ice Age in northern Taiwan inferred from diatoms and geochemistry in a sediment core from a subalpine lake. J. Paleolimnol. 49, 619–631 (2013).

Li, S., Guo, W., Yin, Y., Jin, X. & Tang, W. Environmental changes inferred from lacustrine sediments and historical literature: a record from Gaoyou Lake, eastern China. Quat. Int. 380-381, 350–357 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Magnetic properties of the Wangdongyang subalpine peatland in Zhejiang province, Eastern China and ITS paleoenvironmental implications. Quat. Sci. 37, 1348–1356 (2017).

Wang, H., Liu, J., Wang, Z., Wang, S. & Kuang, X. Simulated analysis of summer climate on centennial time scale in eastern China during the last millenniu. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 1562–1567 (2011). (In Chinese).

Ge, Q.-S. et al. Temperature variation through 2000 years in China: an uncertainty analysis of reconstruction and regional difference. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (2010).

Weber, C. A. Über die Vegetation und Entstehung des Hochmoors von Augstumal im Memeldelta mit vergleichenden Ausblicken auf andere Hochmoore der Erde (1902).

Sullivan, P. F., Arens, S. J. T., Chimner, R. A. & Welker, J. M. Temperature and microtopography interact to control carbon cycling in a high arctic fen. Ecosystems 11, 61–76 (2008).

Loisel, J. & Yu, Z. Holocene peatland carbon dynamics in Patagonia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 69, 125–141 (2013).

Blaauw, M. & Christen, J. A. Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process. Bayesian Anal. 6, 457–474 (2011).

Ingram, H. A. P. Size and shape in raised mire ecosystems: a geophysical model. Nature 297, 300–303 (1982).

Barber, K., Chambers, F., Maddy, D., Stoneman, R. & Brew, J. A sensitive high-resolution record of late Holocene climatic change from a raised bog in northern England. Holocene 4, 198–205 (1994).

Steinhilber, F. et al. 9,400 years of cosmic radiation and solar activity from ice cores and tree rings. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5967–5971 (2012).

Ge, Q. et al. Winter half-year temperature reconstruction for the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River and Yangtze River, China, during the past 2000 years. Holocene 13, 933–940 (2003).

Moberg, A. et al. Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 433, 613–617 (2005).

Wang, J. et al. Causes of East Asian temperature multidecadal variability since 850 CE. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 13,485–13,494 (2018).

Selvaraj, K., Wei, K.-Y., Liu, K.-K. & Kao, S.-J. Late Holocene monsoon climate of northeastern Taiwan inferred from elemental (C, N) and isotopic (δ13C, δ15N) data in lake sediments. Quat. Sci. Rev. 37, 48–60 (2012).

He, B., Zhang, H. & Cai, S. Climatic changes recorded in peat from the Dajiu lake basin in Shennongjia since the last 2600 years. Marine Geol. Quat. Geol. 23, 109–115 (2003).

Wang, Y., Song, J., Li, X. & Wang, Q. Sedimentary records of sea-derived carbon and records of paleoproductivity and climate change in the Kuroshio mainstream over the past millennium. Haiyang Xuebao 40, 131–142 (2018).

Li, D., Jiang, H., Li, T. & Zhao, M. Late Holocene paleoenvironmental changes in the southern Okinawa Trough inferred from a diatom record. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 1131–1138 (2011).

Craft, C. B., Seneca, E. D. & Broome, S. W. Loss on ignition and kjeldahl digestion for estimating organic carbon and total nitrogen in estuarine marsh soils: calibration with dry combustion. Estuar. Coast. 14, 175–179 (1991).

Gallego-Sala, A. V. et al. Latitudinal limits to the predicted increase of the peatland carbon sink with warming. Nat. Clim. Change. 8, 907–913 (2018).

Chambers, F. M., Beilman, D. & Yu, Z. Methods for determining peat humification and for quantifying peat bulk density, organic matter and carbon content for palaeostudies of climate and peatland carbon dynamics. Mires Peat 7, 1–10 (2011).

Yang, X., Wang, S. & Tong, G. Character of a nology and changes of monsoon climate over the last 10000 years in gucheng lake, Jiangsu province. Acta Botan. Sin. 38 (1996).

Clymo, R. The limits to peat bog growth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 303, 605–654 (1984).

Yu, Z. Holocene carbon flux histories of the world’s peatlands: global carbon-cycle implications. Holocene 21, 761–774 (2011).

Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Generalized additive models. Stat. Sci. 1, 297–318 (1986).

Chen, F. et al. Moisture changes over the last millennium in arid central Asia: a review, synthesis and comparison with monsoon region. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1055–1068 (2010).

Ge, Q., Wang, S., Wen, X., Shen, C. & Hao, Z. Temperature and precipitation changes in China during the Holocene. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 24, 1024–1036 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42494821, NO. 42471178, and No. 42001081) and the Open Fund Project of Key Laboratory of Watershed Surface Processes and Ecological Security of Jinhua City (KF-2022-13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. conceived the ideas; B.L., H.L., and Z.X. collected field samples; B.L. did the LOI measurement, and reconstructed the carbon flux history; B.L. and H.L. wrote the manuscript; Y.W. Completed the identification of plant macrofossils; C.M. completed the illustration of plant macrofossils; Z.Y., Y.F., Z.X., and J.J. discussed results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Huai Chen and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Liu, H., Wang, Y. et al. A millennium of cold and humid climate decreased carbon accumulation in the subtropical monsoon peatland. Commun Earth Environ 6, 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01993-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01993-z