Abstract

The greening of previously barren landscapes in the Arctic is one of the most relevant responses of terrestrial ecosystem to climate change. Analyses of satellite data (available since ~1980) have revealed a widespread tundra advance consistent with recent global warming, but the length is insufficient to resolve the long-term variability and the precise timing of the greening onset. Here, we measured plant-derived biomarkers from an Arctic fjord sediment core as proxies for reconstructing past changes in tundra vegetation during the transition from the Little Ice Age to modern warming. Our findings revealed a rapid expansion of the tundra since the beginning of the twentieth century, largely coinciding with the decline of summer sea ice extent and glacier retreat. The greening trend inferred from biomarker analysis peaked significantly in the late 1990s, along with a shift in the tundra community towards a more mature successional stage. Most of these signals were consistent with the biomolecular fingerprints of vascular plant species that are more adapted to warmer conditions and have widely expanded in proglacial areas during recent decades. Our results suggest that the greening of Arctic fjords may have occurred earlier than previously thought, improving our mechanistic understanding of vegetation-climate-cryosphere interactions that will shape tundra vegetation under future warming projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decades, anthropogenic climate change has led to rapid warming of the Arctic region1. One important consequence is the perturbation of terrestrial organic carbon (OC) reservoirs (vegetation and soils)2, which in turn may produce multiple carbon-climate feedbacks. Although the final fate of the permafrost is still debated, permafrost thaw induced by temperature increase is expected to reactivate freeze‐locked carbon stocks3, allowing microbial degradation and emission of large quantities of CO2 and CH4 to the atmosphere4. On the other hand, rapid temperature increase is driving changes in tundra productivity and composition5, enhancing “greening” or “browning” processes at high northern latitudes6, which may, in turn, affect photosynthetic carbon uptake7,8 and potentially offset the CO2 outgassing from thawing permafrost. Thus, the projection of climate warming is highly uncertain, as future pathways of organic matter (OM) build-up and loss in soils are insufficiently understood9,10. While modern observations suffer from evident limitations in providing long-term time series, past episodes of climate change from environmental archives may provide an opportunity to reveal the response of terrestrial OC during the 21st century and beyond.

The transition between the Little Ice Age (LIA) and modern warming represents the fastest and most abrupt climate anomaly of the late Holocene11. Despite the relatively coherent pattern of this transition in global temperature reconstructions over the last two millennia12, the timing, climate triggers, and environmental responses differ among regions. In the northernmost Atlantic Ocean, marine sedimentary proxies and ice core data indicate a generalized, although highly variable, increase in sea ice extent during the LIA13. The eastern Fram Strait was characterized by ice advance, whereas the East Greenland Shelf experienced stable marginal ice zone (probably polynya-like) conditions13,14,15. Cold air and ocean temperature also favored glacier growth in high-latitude lands, including Svalbard, Iceland, and Greenland16,17,18. At the beginning of the 20th century, a sharp decrease in sea ice cover in the Nordic Seas corresponded to the termination of the LIA19,20, and glaciers started to retreat from fjords and lowland areas17. As glaciers retreat, new land surfaces are potentially exposed to rapid modification, high erosion rates, soil evolution, and plant community succession, determining in the northern hemisphere a generally more active carbon cycle and faster mobilization pathways between different reservoirs21,22.

Western Svalbard is highly sensitive to modern warming and paraglacial conditions have rapidly expanded since LIA termination23,24,25. Previous studies have largely focused on how climate and sea ice variability are intrinsically tied to the northward advection of warm Atlantic Water (AW) along the continental margin of West Spitsbergen26,27, without considering the effects on landscape evolution and associated terrestrial environmental change. In particular, there is limited knowledge of the coupling between tundra vegetation growth and the modern cryospheric decline, which cannot be assessed from classical land-based investigations, which are usually performed at small temporal/spatial scales and considering specific geomorphological and hydrological alterations separately from vegetation development.

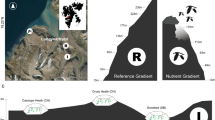

Arctic fjords are sites of high sediment accumulation that receive large amounts of terrigenous input from proglacial streams/rivers and erosional products by glaciers28, making them hotspots of global OC burial29 and high-resolution archives30. Kongsfjorden, a fjord in northwestern Svalbard (Fig. 1), is directly influenced by AW and represents a key site for investigating past climatic and oceanographic changes and their impacts on terrestrial ecosystems. Recently, a marine sediment core (NYA 17–154) with a sub-decadal resolution was used to reveal rapid Atlantification along the eastern Fram Strait in the early 20th century, reconstructing with high precision the advance of warm AW within the Kongsfjorden several decades before the documented instrumental records31. This resulted in rapid sea ice loss19, glacier retreat32, and permafrost warming33, with unknown consequences for terrestrial biospheric carbon reorganization and plant development.

a Dashed lines show the median sea ice extent from 1981 to 2010 for March (maximum sea ice extents) and September (minimum sea ice extents) National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), https://nsidc.org/. Red and blue arrows display the Atlantic-sourced West Spitsbergen Current (WSC) and the Arctic Ocean-sourced Spitsbergen Polar Current (SPC), respectively. The Arctic Ocean base map is based on IBCAOv4153. b Location of the sediment core NYA 17–154 at the edge of the Kongsfjorden. Satellite image from TopoSvalbard (Norwegian Polar Institute, https://toposvalbard.npolar.no/).

The main objectives of this study are (i) to reconstruct the response of the terrestrial environment in NW Svalbard during the LIA-modern era climate anomaly, (ii) to go beyond the limitations of remote sensing observations to estimate when the greening of the High Arctic started, and (iii) to provide a long-term understanding of the vegetation-climate-cryosphere interactions, which is crucial for predicting how tundra ecosystems will respond to anthropogenic warming in high-latitude regions. To achieve these goals, we analyzed the same NYA 17–154 sediment core previously used by Tesi et al.31 to describe the modern Atlantification of the Kongsfjorden. The 112 cm long archive holds an accurate chronology of the last ~780 years, and it is uniquely located in a region suitable to record terrestrial carbon inputs from a broad periglacial area that includes both land- and marine-terminating glaciers with rapid recession rates34. In our study, bulk OC isotopes (∆14C and δ13C) and a suite of land-derived biomarkers (n-alkanes, fatty acids, glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers, cutin acids, and lignin phenols) were used as proxies of terrestrial input and vegetation changes on land. Biomarker data were further interpreted by comparison with vegetation tissues from representative vascular plants and mosses collected in the study region. Furthermore, we compared the past oscillation of sea ice extent with plant-specific proxies (lignin phenols and cutin acids) of our record, in order to investigate the long-term co-variability between greening and sea ice extent. The temporal variability of each proxy was further elaborated with an advanced statistical approach based on generalized additive models (GAM)35, in order to obtain a more accurate temporal trend, adapted to be compared with high-resolution climate and environmental reconstructions, and to objectively identify any climate change–induced perturbations in the terrestrial OC pool.

Results

Features of sedimentary OC pool and terrestrial input contributions

The chronology of the NYA 17–154 core was developed by Tesi et al.31 using radiocarbon dates from benthic foraminifera and 210Pb data. The authors also used a sharp peak of the molecular biomarker retene—a sign of the beginning of coal mining in 1916 in Kongsfjorden—to corroborate the 210Pb data and assess the local marine radiocarbon reservoir effect. The resulting chronology indicated that the sedimentary record spans the last 780 years with a resolution of 5–10 years cm−1 (Fig. 2). In our study, bulk carbon data and terrestrial biomarkers were compared with the most accurate reconstructions of atmospheric temperature anomalies at both regional and local scales: the PAGES Arctic 2k database36 and δ18O data from the Austfonna ice core37, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). The historical variability of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index over the last centuries38 (Fig. 2c) was also considered, in order to provide an accurate ensemble of past climatic fluctuations in the Svalbard region, which ultimately helped us to clearly identify the LIA cooling phase (between 1650 and 1900 AD) and the abrupt anthropogenic warming of the 20th century.

The lines show a the PAGES Arctic 2k annual temperature reconstruction (averaged to decadal values)36, b the δ18O of Austfonna ice core (Svalbard)37, and c the reconstructed North Atlantic Oscillation index (NAO)38. It further shows NYA 17–154 data for d total organic carbon (TOC), e Δ14C of bulk OC (corrected for year of deposition), f δ13C of bulk OC. The solid curves correspond to the generalized additive mode (GAM) trend, with light bands representing 95% across-the-function confidence intervals. The gray columns highlight the Little Ice Age (LIA) and its coldest phase (dark gray)154.

The downcore TOC distribution followed the general climate variability, with low values observed during the LIA (Fig. 2d). However, the dynamics driving OC input into the fjord were not easily deductible based on bulk TOC due to the intrinsic complexity of the sedimentary pool and early diagenesis, which is particularly important at the sediment-water interface39. Based on δ13C range defined for Kongsfjorden sediments (outer fjord = ~–24 δ13C‰; inner fjord = ~–22 δ13C‰, river sediments = ~–21 δ13C‰)28,40,41,42,43, downcore bulk δ13C suggested a mixture of terrestrial and marine OC (Fig. 2f), with the latter being relatively more important toward the top. However, the Δ14C signature of bulk OC was significantly lower throughout the core (Fig. 2e). The predepositional bulk Δ14C was approximately—375.1 ± 2.00 ‰ during the LIA and increased in the modern layers up to—262.0 ± 1.93 ‰. Thus, besides the relatively low land-derived contribution based on δ13C fingerprint, it is evident that this fraction carries an ancient signal, probably reflecting the input of coal, IRD, and permafrost OC. The decrease in radiocarbon ages toward the top can be interpreted as a sign of either an increase of marine OC—in turn, reflecting downcore loss of reactive marine OC in line with δ13C data44—or input of fresh plant debris in response to the changing climate and greening of the fjord. However, we cannot exclude that the two processes operated together combined with the possible 1950 radiocarbon bomb spike influence which was then incorporated into the biospheric marine and terrestrial carbon, at least for the samples after 1950. In addition, the Suess effect can also potentially explain the relatively more depleted values during recent times.

Terrestrial biomarkers can provide further information on changes that occurred in the terrestrial pools and, in particular, on the response of terrestrial ecosystems to climate change45. Yet, plant wax lipids confirm the highly heterogeneous composition of the sedimentary OC pool supplied from land42. For instance, the carbon preference index (CPI) and average chain length (ACL) of n-alkanoic acids revealed mixed contributions from different sources (Fig. 3a), whereas n-alkanes were dominated by a mature OC pool (Fig. 3b), likely in the form of coal which is highly abundant in the region46. In addition, a recent study has shown that n-alkanoic acids from sediments collected in the fjord are pre-aged, probably reflecting a noteworthy permafrost input from ancient soils around the fjord43. Altogether, these findings suggest that temporal trends of high molecular weight (HMW) n-alkanes (n-C25 to n-C31) and HMW n-alkanoic acids (n-C24 to n-C32), although representing large constituents of epicuticular wax layers of higher land plants, in our study are not suitable for detecting tundra vegetation expansion (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b) because they can also carry an ancient signal.

The figure shows the relative influence of five distinct end members for n–alkanoic acids and n–alkanes in the Kongsfjorden: marine sediments42,43, soil42,43, coal42,43, ice-rafted detritus (IRD)42, and sediments affected by proglacial river discharge (Bayelva sediment)43. Carbon Preference Index (CPI) and Average Chain Length (ACL) of a n–alkanoic acids and b n–alkanes for the different end members are compared with NYA 17–154 sediment core. Symbols and bars display mean, and s.d. of NYA 17–154 results and each source is derived from literature data.

We also evaluated brGDGTs as proxies for soil development and their potential relationship with the greening on the fjord. Specifically, changes in the terrestrial OC reservoir have also been investigated in different marine settings based on the ratio of brGDGTs to crenarchaeol [i.e., the branched and isoprenoid tetraether (BIT) index]47 (Supplementary Fig. 1c), that traces input of soil material in marine environments. However, previous studies have questioned the applicability of brGDGTs and related proxies as tracers of soil material input in Svalbard fjords due to the production of brGDGTs by bacteria dwelling within marine sediments48,49. Values of the #ringstetra index > 0.7 (Supplementary Fig. 1d) indeed denote in situ marine brGDGTs production50, suggesting that, in this case, the BIT index cannot provide reliable evidence for soil development and Arctic greening.

In summary, our results indicate that tundra vegetation changes cannot be unambiguously identified with a simple mass balance approach using δ13C or considering all molecular proxies. This is particularly true for wax lipids whose Δ14C fingerprint often reflects protracted storage on the continent prior to erosion, transportation, and redeposition in marine sediments51. In contrast, lignin phenols and cutin acids usually have higher ∆14C values in Arctic watersheds, suggesting the incorporation of young carbon supplied from recent vegetation debris and a faster mobilization pathway (i.e., surface runoff processes)52. In the next section, we will discuss the distributions of these other plant-specific biomarkers and evaluate their potential to reconstruct changes in terrestrial vegetation dynamics in the Arctic.

Greening signal from cutin and lignin monomers

Cutin and lignin are naturally occurring and widely abundant biopolymers found almost exclusively in terrestrial plants53,54, and their monomers (i.e., cutin acids and lignin phenols) have proven to be useful chemical biomarkers for reconstructing past vegetation change in different sedimentary archives55,56,57,58,59,60. Given their resistance to degradation in marine sediments, especially in oxygen-free conditions61, these biopolymers persist over long periods, allowing them to accumulate and serve as indicators of plant-derived OC in the ocean62,63. In the NYA 17–154 core, cutin concentration (Fig. 4b) rapidly increased from 1927 AD onward, reaching the highest level of the entire record in 1998 AD. After this maximum, however, the reconstruction of the cutin trend in the upper part of the core concluded with a slight decrease. Thus, the last century emerged as a period of drastic change, highly significant also in the model trend parameterization (Supplementary Fig. 2b, first derivate of the GAM fitted trends for cutin), and led us to consider the contribution of terrestrial vegetation growth as one of the main processes potentially involved. The diagnostic proxy for soil OM input based on cutin acids (ω-C16/∑C16) suggested the deposition of relatively fresh cutin likely released from surface soil horizons during the 20th century (low ratio), while underneath the root influence increases (high ratio) (Fig. 4c)64,65,66,67. Consistently, for lignin biomarkers, the p-coumaric acid to ferulic acid ratio (pCd/Fd) (Fig. 4d) was relatively high in the upper record, suggesting a large contribution of fresh terrestrial OM from upper soils, while root-derived material appeared to be relatively more important only before the 20th century65,68,69.

The lines show a the 40-year smoothed late-summer Arctic sea ice extent reconstructed from high-resolution terrestrial proxies20, b sum of cutin acids concentration, c ratio of C16 ω-hydroxy alkanoic acids to the sum of C16 ω-hydroxy alkanoic acids, DAs, and mid-chain hydroxy and epoxy acids (ω-C16/∑C16). d ratio of p-coumaric acid (pCd) to ferulic acid (Fd), e Lignin Phenol Vegetation Index (LPVI), and f proximal glacier foraminifera (C. reniforme and E. excavatum f. clavatum)31. The solid curves correspond to the generalized additive mode (GAM) trend, with light bands representing 95% across-the-function confidence intervals. The gray columns highlight the Little Ice Age (LIA) and its coldest phase (dark gray)154. The yellow areas display periods with low sea ice extent20.

It is worth mentioning that early diagenesis might affect the applicability of these proxies. However, lignin-based proxies (i.e., acid/aldehyde ratios of vanillyl and syringyl phenols) commonly used to infer degradation70, in our record do not provide direct evidence for extensive diagenesis. Specifically, high acid/aldehyde ratios were instead measured in fresh plant tissues collected in the study region (e.g., the polar willow, Salix polaris; Supplementary Table 2) and the values were consistent with those observed in the core (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, while indeed the ω-C16/∑C16 ratio, that increases with increasing degradation70, could potentially reflect the aging of terrestrial material during accumulation, the pCd/Fd ratio, that similarly increases with the extent of diagenesis70, exhibit an opposite trend and thus it does not support the fact that the downcore trend reflects diagenesis. Instead, ω-C16/∑C16 and pCd/Fd exhibit similar distributions as those observed in the Great Arctic Rivers65, where they were used to infer soil dynamics (surface vs deep pools) in Arctic terrestrial ecosystems, suggesting a common pan-Arctic dynamics across large to small watersheds. Given such observations, ω-C16/∑C16 and pCd/Fd combined may thus represent specific vegetation proxies suitable for reconstructing significant change in the terrestrial plant cover and, accordingly, the rapid cutin accumulation observed in the recent decades can be interpreted as a widespread signal of “greening” actively advancing in the mainland area. Indeed, compared to other wax lipids, cutin acids are usually much younger based on compound-specific radiocarbon analyses52, further supporting their use as tracers for young, near-surface carbon pools.

The Lignin Phenol Vegetation Index (LPVI) (Fig. 4e), an indicator of changes in vegetation composition for historical environmental reconstruction71,72, further suggested a significant contribution from vascular plants. In particular, the LPVI values were substantially within the range of non-woody angiosperms (reported to be approximately between 500 and 2800)72, which is consistent with the “shrub moss tundra” vegetation that dominates the Kongsfjorden landscape73,74. In addition, as shown by previous plant-specific proxies, the modeled trend for the LPVI index also revealed a significant increase after the LIA termination (Supplementary Fig. 3b). We interpreted this common pattern as a general response of the terrestrial biosphere to the massive cryospheric recession registered for modern Kongsfjorden. Indeed, as Tesi et al.31 showed in the same sediment core, the abundance of proximal glacier foramminifera rapidly decreased during the 20th century (Fig. 4f) as a consequence of the rapid retreat of tidewater glaciers driven by progressive Atlantification of the Fjord. Therefore, our proxy data collectively point toward a strong coupling between the modern signal of greening and the general glacier mass loss registered in the early twenty-first century in the Svalbard region.

Co-variability with sea ice extent

Remote sensing studies have documented an overall greening trend in Svalbard during the last 30 years similar to that found at lower latitudes in the pan-Arctic region75,76, where since the 1980s a rapid increase in tundra vegetation77,78,79,80 and seasonal peak greenness81,82,83 have been observed. Arctic greening is believed to be influenced by different driving factors, such as warmer summer temperatures5,84, longer growing seasons85, increased precipitation86, deeper and earlier seasonal permafrost thaw87, and increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations88. Among these, the loss of Arctic sea ice observed in recent decades has received great attention and has been linked to shrub growth and tundra productivity increase89,90,91,92,93,94,95. Specifically, in the Svalbard archipelago a large increase in tundra shrub productivity was observed with the recent onset of dramatic sea ice decline94. It was inferred that local and regional reductions in sea ice may promote warmer conditions in adjacent terrestrial ecosystems, due to the associated decreases in surface albedo96 and in cold air advection from the ice-covered ocean (sea breeze)97. In addition, on a Pan-Arctic scale, a co-variability pattern between sea ice and tundra productivity has been identified and documented in areas where sea ice is distant from vegetated land masses95. In this latter case, sea ice variability was found to indirectly affect vegetation growth through coupling with large-scale atmospheric forcing and sea surface dynamics, which in turn may control plant phenology in a more complex way91,94.

In light of these observations, we compared our plant-specific biomarker records from the NYA 17–154 core with the reconstructed changes in Arctic summer sea ice over the past ~780 years20 in order to evaluate the influence of sea ice forcing on tundra growth over a broad temporal and spatial scale (Fig. 4a). The selected summer sea ice extent was estimated from a compilation of terrestrial proxies across the Arctic. However, its temporal variability resulted very similar to the local sea ice reconstructions from the eastern Fram Strait (Supplementary Fig. 5), thereby confirming the strategic position of our record able to capture small-scale processes but with a strong analogy with global Pan-Arctic changes. Thus, cutin concentration and its fingerprint (ω-C16/∑C16) showed a tight and inverse relationship with the variability of summer sea ice extent throughout the entire record (Fig. 4a, c). In particular, the sea ice reduction observed from 1450 to 1620 AD and during the 20th century was associated with a change in cutin-derived proxies, suggesting an increase in land vegetation coming from surface OM-rich soil pools. Overall, our findings suggest a sea ice control on greening. The ecological implications for the tundra biome, both in terms of species composition and plant successional stage, are poorly known today, and our reconstruction can provide important insights into the greening of Arctic fjords.

Tundra vegetation shift

Svalbard glaciers are retreating at unprecedented rates since the end of the LIA23 and with a considerably faster mass loss than for many other glacier regions of the world98, making the foreland domain and the surrounding non-glaciated areas a unique natural system where terrestrial biospheric carbon evolve rapidly99. As glaciers retreat, new terrains are exposed to plant colonization and ecological succession, with a large effect on vegetation change (both in terms of plant cover and species composition) and soil development100,101,102,103. Moss colonization is achieved at the initial successional stage and within a few years of glacier retreat, thanks to their extreme pioneering abilities104,105,106. Vascular plants, instead, usually occur at a later stage of succession, favored by a well-developed biological soil crust103,107; as terrestrial vegetation increases, more OC is transferred from vegetation debris into the substrate, which is finally exported by proglacial rivers to the ocean and buried in marine sediments.

Plant-specific biomarkers in our sedimentary record can thus provide an integrated signal of tundra vegetation change and soil development. Starting from the greening signal registered from total cutin concentration, we derived additional information about the plant's successional stage by further interpreting the cutin and lignin fingerprints. Specifically, the ratio of ω-C16/∑C16 has been used to differentiate between inputs from lower plants (0.8 ± 0.1; bryophytes) and vascular plants (0.1–0.2)64,66,108. Similarly, for lignin-derived phenols, a high ratio of pCd/Fd has been reported for moss and peat inputs68,109. A large proportion of the two source proxies, therefore, may independently indicate early plant successional stage in the terrestrial domain. In our record, this was particularly evident in the pCd/Fd increasing trend registered after the termination of the LIA (Fig. 4d), which could be interpreted as consistent with the onset of extensive glacier retreat, followed by soil development and rapid colonization by pioneer plants like mosses65,68,109. Conversely, the ω-C16/∑C16 ratio revealed a downward trend (Fig. 4c), reflecting contrasting inputs from vascular plants and mature successional stages of tundra vegetation. These apparently divergent results could instead provide new insights into the successional changes in tundra community composition. By comparing the molecular fingerprint of pCd/Fd and ω-C16/∑C16 obtained from tundra species of the Brøgger peninsula collected near the coring site (Supplementary Table 2), we identified a clear separation between vascular plant (low pCd/Fd and ω-C16/∑C16 ratios) and mosses (high pCd/Fd and ω-C16/∑C16 ratios) (Fig. 5a). Our analyses on potential sources indicate that Salix polaris and Dryas octopetala were the only two vascular plant species that presented a significantly greater proportion of pCd/Fd. Since these two dwarf shrubs have been reported to occur preferentially in advanced stages of plant succession101,110 and to increase their coverage/growth under milder climate conditions111,112,113,114, our reconstruction likely indicates a rapid development of tundra vegetation toward mature successional stages. Salix and Dryas are among the most common vascular plants in Svalbard113, and their debris (pollens, seeds, and leaves) are naturally adapted for wind and water dispersal, even over long distances112,115. This suggests that the sediment organic matter composition is strongly affected by catchment vegetation dynamics. This is also supported by the historical photosynthetic biomass record of the Svalbard soil between 9400 and 2200 BP, which follows the Holocene temperature changes with an increase of the photosynthetic biomass production during warmer periods, and vice versa116.

a Biomarker fingerprint of pCd/Fd against ω-C16/∑C16 for different species of vascular plants and mosses. Symbols and bars display mean and s.d., respectively. b Evidence of a near-simultaneous increase of both proxies, S. polaris growth-ring chronology119 and cutin trend (NYA 17–154), provides a clear greening signal for the Svalbard region.

Both palynological and dendrochronological studies on polar willows from the Svalbard further corroborate our findings. The pollen of S. polaris was frequently observed to predominate in soil samples117. Furthermore, a significant increase in Salix type pollen after the LIA termination was recently documented in a lacustrine sediment archive (Lake Tenndammen, Colesdalen)118. Radial growth chronology of S. polaris also revealed wide growth rings starting from 1950 in response to a rapid increase in air temperature119. Such radial growth increase was very similar to our cutin trend reconstruction for the twentieth century (Fig. 5b), even beyond 2005, when the growth-ring dimension rapidly decreased, probably due to the high sensitivity of S. polaris to moister conditions and more frequent rainfall events occurred in recent decades119. Overall, these independent works provide empirical, common evidence of the response of vascular plants, particularly S. polaris, to ongoing climate change and how this may have been reflected in the temporal trend of lignin and cutin proxies analyzed in our sedimentary record.

Discussion

Our results on plant-specific proxies combined with modeling trend estimations demonstrate a rapid greening of western Svalbard at the beginning of the 20th century. In particular, we found the following signs of tundra expansion and vegetation composition change: (i) rapid increase of plant-specific proxies, (ii) marked association with glacier retreat in the region, (iii) shift of tundra community toward mature successional stages, and (iv) progressive dominance of vascular species adapted to milder climatic conditions (likely S. polaris and D. octopetala).

Moreover, a comparison of our data with an independent paleoreconstruction of Arctic sea ice extent suggested a strong influence of sea ice on the greening trend. This finding was strongly supported by both remote sensing94,120 and field observations95. However, the mutual relationship between the last two approaches is poorly understood121 and, when considered separately, they are unable to reveal the exact mechanisms by which sea ice decline may enhance tundra vegetation productivity and greening. Satellite data can only document vegetation change for the last few decades122 and do not provide a deep-historical perspective, which is extremely important for estimating the impact of climate change. In contrast, in situ data do not represent the spatial heterogeneity of the link between sea ice and tundra95. Our record goes beyond such limits, providing a space-integrated signal of tundra vegetation change throughout the historical extent of the past 780 years. We suggest that the greening process likely started in the early twentieth century (i.e., around 1930) and rapidly increased until the end of the 1990s, matching the extremely low sea ice extent observed in the same period. This event was well above the natural variability inferred by the reconstruction. However, going back to our record, another episode of reduced sea ice cover associated with vegetation increase occurred in the early seventeenth century, suggesting a long historical relationship and possible common drivers.

It could be argued that the strong correlation between greening and sea ice reduction may represent a simple co-variability process associated with the general increase of the Arctic atmospheric temperature. To elucidate this aspect, we further compared our proxy-based vegetation reconstruction with the Arctic 2k temperature and the historical NAO index for the detection of anomalous warming events (Fig. 2a, c). Considering the small increase in tundra vegetation inferred by our record between AD 1450 and 1620, this was in contrast with the general cooling trend observed since the beginning of the LIA. Moreover, for the same time period, the possible advection of warm air masses into the Arctic was excluded by the NAO index, which was unstable and varied between positive and negative phases (Fig. 2c). Instead, the intrusion of warm and saline water from the North Atlantic into the Fram Strait was supposed to be the main driver of sea ice decrease during the early seventeenth century123. This finding reinforces our hypothesis that sea ice extent reconstruction is not just another surrogate of Arctic temperature history but has the potential to capture an ensemble of favorable climate conditions for the widespread tundra growth82. As a consequence, we can suppose that the unprecedented sea ice loss observed over recent decades was mainly driven by strong advection of warm AW into the Arctic. This event likely acted together with global warming and the persistent positive NAO mode to synergistically enhance the modern greening signal. However, to the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first proxy-based greening reconstruction and further evidence from sedimentary records across diverse Arctic regions is needed to better interpret and validate our greening trend associated with sea ice dynamics.

Finally, we found a first signal of tundra vegetation change toward the mature successional stage that agrees with general plant evolution observed in Svalbard104. Generally, moss colonization occurs after rapid glacier retreat and if environmental conditions are suitable for plant settlement. Then, progressive accumulation of organic matter over decades/centuries can provide substrate for colonization by vascular plants. Such advanced tundra succession was supported by our results, which revealed a predominant contribution from vascular plants over moss input. Moreover, S. polaris was likely the most representative species, reflecting the ongoing shift of tundra plant communities toward species better adapted to milder climatic conditions. Different in situ field-observed vegetation evidences114,124,125, palynological reconstructions117,118, and other ecological signals, including shrub cover increase110,126 and dendrochronological studies119,125,127,128, agree with our findings. However, a clear knowledge gap remains due to the patchy distribution of our record and the considerable variation in vegetation productivity and plant species across the Arctic tundra biome. Thus, we envision that biomarkers could represent a useful diagnostic tool for reconstructing tundra vegetation systems in future investigations.

In summary, our study demonstrates how the greening of a previously barren Arctic landscape can be effectively detected using marine sediment archives, complementing and extending modern time series data and satellite observations. Throughout the twentieth century, we demonstrated how sea ice reduction and glacier retreat were well-coupled with a widespread growth of Svalbard’s tundra vegetation, revealing also a signal of plant community shift towards vascular species better adapted to a warming climate. Collectively, our long-term greening reconstruction provides a critical benchmark for future research into vegetation-climate-cryosphere interactions, which will likely shape the Arctic environment in the face of ongoing climate change.

Methods

Sampling

In June 2017, a 112 cm long core (NYA 17–154) was obtained from Kongsfjorden (78°59′52.2′ N, 11°39′24′′ E, 297 m water depth) using a 100 kg light gravity corer on the MS Teisten vessel operated by Kings Bay AS. The core was split into two halves and then sub-sampled at 1 cm intervals. A total of 112 samples were collected over the entire core length. Sediments were freeze-dried, ground for homogenization, and stored in glass vials prior to geochemical analysis. Bulk and biomarker data were measured in all 112 samples. Only bulk OC 14C analysis was performed on 5 samples properly selected starting from the top and throughout the most informative core intervals. For the molecular structure of the biomarkers, the work of Bianchi and Canuel129 provides a detailed and comprehensive description. In addition, in the Supplementary Table 3 we report a summary of the primary source of each analyzed biomarker and the information that can be inferred from each proxy.

Age-depth model

To be consistent with previous studies, our study relies on the age-depth model developed by Tesi et al.31 for the sediment core NYA 17–154. Briefly, the model was developed by combining 210Pb data with five radiocarbon dates measured on N. labradorica (benthic foraminfera) picked from specific intervals. The 210Pb activity was derived from its daughter nuclide, 210Po, via alpha spectrometry. Radiocarbon dates were determined by accelerator mass spectrometry and calibrated using the Marine13 curve130. The local reservoir effect (∆R) was estimated using foraminiferal species (N. labradorica) collected at the base of the retene excess interval (coal proxy), which is a time marker (1916) linked to the onset of coal mining activities in Ny-Alesund131. The final ∆R correction of 350 ± 75 years significantly updated the previously reported values for the region132. The final age-depth model was developed with OxCal together with an Outlier_Model analysis. No outliers were detected, and a robust chronological framework was generated with a high agreement index.

Bulk OC

TOC content and stable carbon isotope were measured on freeze-dried homogenized subsamples after CaCO3 removal with an acid treatment (HCl, 1.5 M). Samples were subsequently neutralized and dried over NaOH pellets (60° C, 72 h) and wrapped in Sn capsules to aid combustion. TOC was analyzed in parallel with stable carbon isotopes on a Thermo Fisher Elemental Analyser (FLASH 2000 CHNS/O) coupled with a Thermo Finnigan Delta plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the National Research Council, Institute of Polar Sciences in Bologna (Italy)133. TOC amounts are reported in weight percent (%). Stable carbon isotope data are reported as δ13C values (‰) relative to the international reference material Vienna PeeDee Belemnite (V-PDB), with an instrumental uncertainty lower than 0.05‰. Radiocarbon analyses of TOC were conducted on subsamples after decarbonation, using a coupled elemental analyser-accelerator mass spectrometer system (EA: Elementar vario Isotope; AMS: Mini Carbon Dating System MICADAS, Ionplus) at the Laboratory of Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Bremerhaven (Germany)134. Radiocarbon data are reported as ∆14C values (‰)135 after correcting for the calibrated depositional age.

Lipids

Freeze-dried sediment samples were placed in pre-combusted vials to extract lipids using a 9:1 (v/v) dichloromethane:methanol (DCM:MeOH) solvent mixture. The vials were sonicated for 15 minutes at 60 °C and centrifuged, with the supernatant being transferred to new pre-combusted vials. This extraction process was repeated three times in total. The extract was then dried and saponified with 0.5 M methanol solution of KOH at 70 °C for 1 hour. Then, MilliQ water with 2% NaCl was added. The neutral fraction was extracted three times with hexane. The samples were then acidified to pH 1 using concentrated HCl. The acid fraction was extracted with a 3:2 mixture of hexane and DCM. Column chromatography (SiO2, water-deactivated) was used to remove impurities by eluting first with hexane, then a 4:1 mixture of DCM and hexane (containing n-alkanoic acids), and finally DCM. The neutral fraction was further separated into a polar and a non-polar fraction via silica gel column chromatography. The apolar fraction, containing n-alkanes, was separated using a 3:1 (v/v) hexane:DCM solution, while the polar fraction containing GDGT was eluted using a 1:1 (v/v) MeOH:DCM solution. Before extraction, a specific amount of the internal standard was added to the sediment samples for each of the three compound classes: n-alkanes (C22), n-alkanoic acids (C21), and GDGT (C46-GDGT) respectively. The n-alkanes and n-alkanoic acids were then analyzed at the National Research Council Institute of Polar Sciences (Bologna, Italy) with a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system (Agilent 7820 A GC, 5977B MSD) with splitless injection on a DB-5 column (30 m × 250 μm; 0.25 μm film thickness), an initial temperature of 60 °C, a ramp of 10 °C per minute until 310 °C, and a hold time of 16 min. Before the injection, the n-alkanoic acids were derivatized with trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) + 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) at 60 °C for 30 min. Quantification was performed in full scan mode (50–650 m/z) and using a five-point calibration curve with commercially available standards for n-alkanoic acids (C16–C32; Sigma-Aldrich) and n-alkanes (C21–C40; Sigma-Aldrich). Here, we only report data for HMW n-alkanes and n-alkanoic acids in the supplementary section, where HMW refers to carbon chain lengths of ≥25 carbon atoms for n-alkanes and ≥24 for n-alkanoic acids. In order to compare our results with different end members of the study area available from the literature, the carbon preference index (CPI) and average chain length (ACL) of the n-alkanes and n-alkanoic acids were calculated as reported by Kim et al.42 and Kusch et al.43, respectively:

The polar GDGT fractions were filtered to remove particles and then analyzed using an Agilent 1200 high-performance liquid chromatography system connected to an Agilent 6120 APCI-MS at the laboratory of the AWI, Ger. The method was slightly modified from a previous one to fit our equipment136. The separation of GDGTs, including 5-/6-methyl isomers of branched- GDGTs, was achieved using two ultraperformance liquid chromatography silica columns in series (Waters Acquity BEH HILIC, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm) and a precolumn, all maintained at 30 °C. Mobile phases A and B consisted of n-hexane/chloroform (99:1 v/v) and n-hexane/2-propanol/chloroform (89:10:1, v/v/v), respectively. After 20 µL sample injection and 25 min of isocratic elution with 18% mobile phase B, the proportion of B was gradually increased to 100% in 55 min. The flow rate was 0.22 ml/min with a max back pressure of 220 bar and a total run time of 100 min. GDGTs were detected using positive ion APCI-MS and SIM of their (M + H)+ ions137. APCI conditions were 50 psi nebulizer pressure, 350 °C vaporizer temperature, N2 drying gas, 5 L/min at 350 °C, −4 kV capillary voltage, and +5 µA corona current. The MS was set to SIM of the following (M + H)+ ions: m/z 1302.3 (GDGT-0), 1300.3 (GDGT-1), 1298.3 (GDGT-2), 1296.3 (GDGT-3), 1292.3 (GDGT-4 + 4′/Crenarchaeol+regio-isomer), 1050 (GDGT-IIIa/IIIa′), 1048 (GDGT-IIIb/IIIb′), 1046 (GDGT-IIIc/IIIc′), 1036 (GDGT- IIa/IIa′), 1034 (GDGT-IIb/IIb′), 1032 (GDGT-IIc/IIc′), 1022 (GDGT-Ia), 1020 (GDGT-Ib), 1018 (GDGT-Ic), and 744 (C46 standard) with a 57 ms dwell time per ion. Due to the lack of appropriate standards138, quantification of the individual GDGTs was achieved by using the response factor obtained from the C46–GDGT internal standard. According to the literature47, BIT index was calculated as follow:

where I, II, and III are concentrations of branched GDGTs and IV the concentration of isoprenoid GDGT, crenarchaeol. The analytical error in the determination of the BIT index is, on average, 0.01. Additionally, we quantified the #ringstetra as an indicator of in situ branched GDGTs production in the marine environment, which is based on the relative proportion of 5-methyl branched GDGTs50:

Lignin phenols and cutin acids

The alkaline CuO oxidation was performed at the laboratory of the Joint Research Center—ENI-CNR Aldo Pontremoli Lecce using a CEM MARS 5 microwave139. Briefly, 2 N degassed NaOH was used to oxidize 2 mg of OC in teflon tubes under oxygen-free conditions at 150 °C for 90 minutes. After the oxidation, a known amount of ethylvanillin was added to the solution as internal recovery standards. The aqueous solution was then acidified to pH 1 with concentrated HCl, extracted with ethyl acetate, dried, and redissolved in pyridine. Before analysis on GC-MS system (Agilent 7890 GC, 5975 MSD), the samples were derivatized with BSTFA + 1% TMCS at 60 °C for 30 min. The CuO oxidation products were analyzed with splitless injection on a DB1-MS column (60 m × 250 μm; 0.25 μm film thickness), with 1.2 ml min−1 helium as carrier, an initial temperature of 100 °C for 5 min, a ramp of 4 °C min−1 to 300 °C, and constant temperature for 8 min. The analysis was carried out in full scan mode (range m/z 50–650) and SIM mode. Lignin-derived reaction products included vanillyl phenols (V = vanillin, acetovanillone, vanillic acid), syringyl phenols (S = syringealdehyde, acetosyringone, syringic acid) and cinnamyl phenols (C = p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid). Individual lignin phenol contents were calculated using a six-point calibration of known concentrations of commercially available external standards for each considered lignin phenol product (Sigma-Aldrich). The quantification of cutin acids was performed using the response factor of ethylvanillin and focused on the most abundant C16 to C18 hydroxy fatty acids: 16-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid, hexadecan-1,16-dioic acid, 18-hydroxyoctadec-9-enoic acid, 7 or 8-dihydroxy C16 α,ω-dioic acid and 8 or 9, or 10,16-dihydroxy C16 acids53,64. Ratio of ω-C16 to total hexadecanoic acid (ω-C16/∑C16) was estimated as described by Goñi et al.66.

Finally, the LPVI was calculated as follow:

where V, S, and C were expressed in % of the total lignin phenols. The index was used to further identify the source of lignin phenols and general taxonomic classification71.

Trend analysis

GAMs were used to estimate the temporal trends of the different proxies. GAMs can model the non-linear relationship between a response variable and time, managing irregular spacing in paleoecological time series35. Thin-plate regression splines were utilized to parametrize the smoothed functions of time140, and automatic restricted maximum likelihood was employed to select optimal smoothness parameters141. No significant residual autocorrelation was detected in any of the time series after being checked (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the main text and/or in the Supplementary Materials. The dataset used in this study is freely available in the open-access repository Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13913336). Any further information regarding this paper can be obtained upon request from the authors.

Code availability

All analyses were conducted in the R environment (version 4.4.1)142. The packages used include mgcv143 (version 1.9.1), scam144 (version 1.2.17), dplyr145 (version 1.1.4), tidyr146 (version 1.3.1), gratia147 (version 0.9.2), zoo148 (version 1.8.12), ggplot2149 (version 3.5.1), cowplot150 (version 1.1.3), scales151 (version 1.3.0), and ggsci152 (version 3.2.0). Codes generated for analyses and figures are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Meredith, M., Sommerkorn, M., Cassotta, S. & Derksen, C. Polar Regions. Chapter 3, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. (2019).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1783–1838 (2019).

Vonk, J. E. et al. Activation of old carbon by erosion of coastal and subsea permafrost in Arctic Siberia. Nature 489, 137–140 (2012).

Schuur, E. A. G. et al. Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature 520, 171–179 (2015).

Elmendorf, S. C. et al. Plot-scale evidence of tundra vegetation change and links to recent summer warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 453–457 (2012).

Berner, L. T. et al. Summer warming explains widespread but not uniform greening in the Arctic tundra biome. Nat. Commun. 11, 4621 (2020).

Forkel, M. et al. Enhanced seasonal CO2 exchange caused by amplified plant productivity in northern ecosystems. Science 351, 696–699 (2016).

Myneni, R. B., Keeling, C. D., Tucker, C. J., Asrar, G. & Nemani, R. R. Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes from 1981 to 1991. Nature 386, 698–702 (1997).

Trumbore, S. E. & Czimczik, C. I. An uncertain future for soil carbon. Science 321, 1455–1456 (2008).

Sulman, B. N. et al. Multiple models and experiments underscore large uncertainty in soil carbon dynamics. Biogeochemistry 141, 109–123 (2018).

Osman, M. B., Tierney, J. E., Zhu, J., Tardif, R. & Hakim, G. J. Globally resolved surface temperatures since the last glacial maximum https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03984-4 (2021).

Consortium, P. et al. Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the common Era. Nat. Geosci. 12, 643–649 (2019).

Maffezzoli, N. et al. Sea ice in the northern North Atlantic through the Holocene: evidence from ice cores and marine sediment records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 273, 107249 (2021).

Kolling, H. M., Stein, R., Fahl, K., Perner, K. & Moros, M. Short-term variability in late Holocene sea ice cover on the East Greenland Shelf and its driving mechanisms. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 485, 336–350 (2017).

Müller, J. et al. Holocene cooling culminates in sea ice oscillations in Fram Strait. Quat. Sci. Rev. 47, 1–14 (2012).

Kelly, M. A. & Lowell, T. V. Fluctuations of local glaciers in Greenland during latest Pleistocene and Holocene time. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 2088–2106 (2009).

Solomina, O. N. et al. Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 149, 61–90 (2016).

Farnsworth, W. R. et al. Holocene glacial history of Svalbard_ Status, perspectives and challenges. Earth Sci. Rev. 208, 103249 (2020).

Fauria, M. M., Grinsted, A. & Helama, S. Unprecedented low twentieth century winter sea ice extent in the Western Nordic Seas since AD 1200. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-009-0610-z (2010).

Kinnard, C. et al. Reconstructed changes in Arctic sea ice over the past 1,450 years. Nat. Publ. Group 479, 509–512 (2011).

Bruhwiler, L., Parmentier, F.-J. W., Crill, P., Leonard, M. & Palmer, P. I. The arctic carbon cycle and its response to changing climate. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 7, 14–34 (2021).

Yoshitake, S. et al. Vegetation development and carbon storage on a glacier foreland in the High Arctic, Ny-Ålesund,. Svalbard Polar Sci. 5, 391–397 (2011).

Martín-Moreno, R., Álvarez, F. A. & Hagen, J. O. ‘Little Ice Age’ glacier extent and subsequent retreat in Svalbard archipelago. Holocene 27, 1379–1390 (2017).

Berthling, I. et al. Analysis of the paraglacial landscape in the Ny-Ålesund area and Blomstrandøya (Kongsfjorden, Svalbard, Norway). J. Maps 16, 818–833 (2020).

Strzelecki, M. C. et al. New fjords, new coasts, new landscapes: the geomorphology of paraglacial coasts formed after recent glacier retreat in Brepollen (Hornsund, southern Svalbard). Earth Surf. Process. 45, 1325–1334 (2020).

Spielhagen, R. F. et al. Enhanced modern heat transfer to the Arctic by warm atlantic water. Science 331, 450–453 (2011).

Wang, Q. et al. Intensification of the Atlantic water supply to the arctic ocean through fram strait induced by Arctic Sea Ice decline. Geophys. Res Lett. 47, e2019GL086682 (2020).

Winkelmann, D. & Knies, J. Recent distribution and accumulation of organic carbon on the continental margin west off Spitsbergen. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6 (2005).

Smith, R. W., Bianchi, T. S., Allison, M., Savage, C. & Galy, V. High rates of organic carbon burial in fjord sediments globally. Nat. Geosci. 8, 450–453 (2015).

Bianchi, T. S. et al. Fjords as aquatic critical zones (ACZs). Earth Sci. Rev. 203, 103145–25 (2020).

Tesi, T. et al. Rapid Atlantification along the Fram Strait at the beginning of the 20th century. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj2946 (2021).

Bourriquen, M. et al. Paraglacial coasts responses to glacier retreat and associated shifts in river floodplains over decadal timescales (1966-2016), Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 4173–4185 (2018).

Boike, J. et al. A 20-year record (1998–2017) of permafrost, active layer and meteorological conditions at a high Arctic permafrost research site (Bayelva, Spitsbergen). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 355–390 (2018).

Schuler, T. V. et al. Reconciling Svalbard glacier mass balance. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 156 (2020).

Simpson, G. L. Modelling palaeoecological time series using generalised additive models. Front. Ecol. Evol. 0, 1–21 (2018).

McKay, N. P. & Kaufman, D. S. An extended Arctic proxy temperature database for the past 2,000 years. Sci. Data 1, 1–10 (2014).

Isaksson, E. et al. Ice cores from Svalbard–useful archives of past climate and pollution history. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A B C. 28, 1217–1228 (2003).

Trouet, V. et al. Persistent positive North Atlantic oscillation mode dominated the medieval climate anomaly. Science 324, 78–80 (2009).

Jørgensen, B. B., Laufer, K., Michaud, A. B. & Wehrmann, L. M. Biogeochemistry and microbiology of high Arctic marine sediment ecosystems—case study of Svalbard fjords. Limnol. Oceanogr. 30, 85–20 (2020).

Faust, J. C. & Knies, J. Organic Matter Sources in North Atlantic Fjord Sediments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 2872–2885 (2019).

Kumar, V., Tiwari, M., Nagoji, S. & Tripathi, S. Evidence of anomalously low δ13C of marine organic matter in an Arctic Fjord. Sci. Rep. 6, 36192 (2016).

Kim, J. H. et al. Large ancient organic matter contributions to Arctic marine sediments (Svalbard). Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1463–1474 (2011).

Kusch, S., Rethemeyer, J., Ransby, D. & Mollenhauer, G. Permafrost organic carbon turnover and export into a High‐Arctic Fjord: a case study from svalbard using compound‐specific 14c analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2020JG006008 (2021).

Ruben, M. et al. Fossil organic carbon utilization in marine Arctic fjord sediments by subsurface micro-organisms. Nat. Geosci. 16, 625–630 (2023).

Inglis, G. N. et al. Biomarker approaches for reconstructing terrestrial environmental change. Annu Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 50, 369–394 (2022).

Dallmann, W. K. Geoscience Atlas of Svalbard. Rapport 148, Norsk Polarinstitutt (2015).

Hopmans, E. C. et al. A novel proxy for terrestrial organic matter in sediments based on branched and isoprenoid tetraether lipids. Earth Planet Sc. Lett. 224, 107–116 (2004).

Crampton-Flood, E. D., Peterse, F. & Damsté, J. S. S. Production of branched tetraethers in the marine realm: Svalbard fjord sediments revisited. Org. Geochem. 138, 103907 (2019).

Peterse, F. et al. Constraints on the application of the MBT/CBT palaeothermometer at high latitude environments (Svalbard, Norway). Org. Geochem. 40, 692–699 (2009).

Damsté, J. S. S. Spatial heterogeneity of sources of branched tetraethers in shelf systems: the geochemistry of tetraethers in the Berau River delta (Kalimantan, Indonesia). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 186, 13–31 (2016).

Eglinton, T. I. et al. Climate control on terrestrial biospheric carbon turnover. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2011585118 (2021).

Feng, X. et al. Multimolecular tracers of terrestrial carbon transfer across the pan‐Arctic: 14C characteristics of sedimentary carbon components and their environmental controls. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1855–1873 (2015).

Hedges, J. I. & Mann, D. C. The characterization of plant tissues by their lignin oxidation products. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43, 1803–1807 (1979).

Ertel, J. R. & Hedges, J. I. The lignin component of humic substances: distribution among soil and sedimentary humic, fulvic, and base-insoluble fractions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 2065–2074 (1984).

Kastner, T. P. & Goñi, M. A. Constancy in the vegetation of the Amazon Basin during the late Pleistocene: evidence from the organic matter composition of Amazon deep sea fan sediments. Geology 31, 291–294 (2003).

Pancost, R. D. & Boot, C. S. The palaeoclimatic utility of terrestrial biomarkers in marine sediments. Mar. Chem. 92, 239–261 (2004).

Visser, K., Thunell, R. & Goñi, M. A. Glacial–interglacial organic carbon record from the Makassar Strait, Indonesia: implications for regional changes in continental vegetation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 17–27 (2004).

Sun, D. et al. Late quaternary environmental change of Yellow river basin: an organic geochemical record in Bohai Sea (North China). Org. Geochem. 42, 575–585 (2011).

Hu, J., Loh, P. S., Chang, Y.-P. & Yang, C.-W. Multi-proxy records of paleoclimatic changes in sediment core ST2 from the southern Zhejiang-Fujian muddy coastal area since 1650 yr BP. Cont. Shelf Res. 239, 104717 (2022).

Yang, B., Ljung, K., Nielsen, A. B., Fahlgren, E. & Hammarlund, D. Impacts of long-term land use on terrestrial organic matter input to lakes based on lignin phenols in sediment records from a Swedish forest lake. Sci. Total Environ. 774, 145517 (2021).

Arndt, S. et al. Quantifying the degradation of organic matter in marine sediments: a review and synthesis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 123, 53–86 (2013).

Gough, M. A., Fauzi, R., Mantoura, C. & Preston, M. Terrestrial plant biopolymers in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 57, 945–964 (1993).

Feng, X. et al. 14C and 13C characteristics of higher plant biomarkers in Washington margin surface sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 105, 14–30 (2013).

Goñi, M. A. & Hedges, J. I. Cutin-derived CuO reaction products from purified cuticles and tree leaves. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 3065–3072 (1990).

Feng, X. et al. Multi-molecular tracers of terrestrial carbon transfer across the pan-Arctic: comparison of hydrolyzable components with plant wax lipids and lignin phenols. Biogeosciences 12, 4841–4860 (2015).

Goñi, M. A. & Hedges, J. I. Potential applications of cutin-derived CuO reaction products for discriminating vascular plant sources in natural environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 3073–3081 (1990).

Goñi, M. A. & Hedges, J. I. The diagenetic behavior of cutin acids in buried conifer needles and sediments from a coastal marine environment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 3083–3093 (1990).

Amon, R. M. W. et al. Dissolved organic matter sources in large Arctic rivers. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 94, 217–237 (2012).

Houel, S., Louchouarn, P., Lucotte, M., Canuel, R. & Ghaleb, B. Translocation of soil organic matter following reservoir impoundment in boreal systems: Implications for in situ productivity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1497–1513 (2006).

Opsahl, S. & Acta, R. B. Early diagenesis of vascular plant tissues: lignin and cutin decomposition and biogeochemical implications. Chem. Geol. 59, 4889–4904 (1995).

Tareq, S. M., Tanaka, N. & Ohta, K. Biomarker signature in tropical wetland: lignin phenol vegetation index (LPVI) and its implications for reconstructing the paleoenvironment. Sci. Total Environ. 324, 91–103 (2004).

Tareq, S. M., Kitagawa, H. & Ohta, K. Lignin biomarker and isotopic records of paleovegetation and climate changes from Lake Erhai, southwest China, since 18.5kaBP. Quatern Int 229, 47–56 (2011).

Jónsdóttir, I. S. Terrestrial ecosystems on svalbard: heterogeneity, complexity and fragility from an Arctic Island perspective. Biol. Environ. Proc. R. Ir. Acad. 105, 155–165 (2005).

Walker, D. A. et al. The circumpolar Arctic vegetation map. J. Veg. Sci. 16, 267–282 (2005).

Vickers, H. et al. Changes in greening in the high Arctic: insights from a 30 year AVHRR max NDVI dataset for Svalbard. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 105004 (2016).

Karlsen, S. R., Elvebakk, A., Stendardi, L., Høgda, K. A. & Macias-Fauria, M. Greening of Svalbard. Sci. Total Environ. 945, 174130 (2024).

Zhou, L. et al. Variations in northern vegetation activity inferred from satellite data of vegetation index during 1981 to 1999. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 20069–20083 (2001).

Ju, J. & Masek, J. G. The vegetation greenness trend in Canada and US Alaska from 1984–2012 Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 176, 1–16 (2016).

Park, T. et al. Changes in growing season duration and productivity of northern vegetation inferred from long-term remote sensing data. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 084001 (2016).

Karlsen, S. R., Elvebakk, A., Tømmervik, H., Belda, S. & Stendardi, L. Changes in onset of vegetation growth on Svalbard, 2000–2020. Remote Sens. 14, 6346 (2022).

Park, T. et al. Changes in timing of seasonal peak photosynthetic activity in northern ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2382–2395 (2019).

Bhatt, U. S. et al. Changing seasonality of panarctic tundra vegetation in relationship to climatic variables. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 055003 (2017).

Piao, S. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Climate sensitivity of shrub growth across the tundra biome. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 887–891 (2015).

McGuire, A. D. et al. Sensitivity of the carbon cycle in the Arctic to climate change. Ecol. Monogr. 79, 523–555 (2009).

van der Kolk, H.-J., Heijmans, M. M. P. D., van Huissteden, J., Pullens, J. W. M. & Berendse, F. Potential Arctic tundra vegetation shifts in response to changing temperature, precipitation and permafrost thaw. Biogeosciences 13, 6229–6245 (2016).

Heijmans, M. M. P. D. et al. Tundra vegetation change and impacts on permafrost. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 68–84 (2022).

McGuire, A. D. et al. Dependence of the evolution of carbon dynamics in the northern permafrost region on the trajectory of climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 3882–3887 (2018).

Bhatt, U. S. et al. Circumpolar arctic tundra vegetation change is linked to sea ice decline. Earth Interact. 14, 1–20 (2010).

Bhatt, U. S. et al. Implications of Arctic Sea ice decline for the earth system. Annu. Rev. Env Resour. 39, 1–33 (2014).

Post, E., Bhatt, U. S., Bitz, C. M., Brodie, J. F. & Fulton, T. L. Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science 341, 519–524 (2013).

Kerby, J. T. & Post, E. Advancing plant phenology and reduced herbivore production in a terrestrial system associated with sea ice decline. Nat. Commun. 4, 2514 (2013).

Dutrieux, L. P., Bartholomeus, H., Herold, M. & Verbesselt, J. Relationships between declining summer sea ice, increasing temperatures and changing vegetation in the Siberian Arctic tundra from MODIS time series (2000–11). Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 044028 (2012).

Macias-Fauria, M., Karlsen, S. R. & Forbes, B. C. Disentangling the coupling between sea ice and tundra productivity in Svalbard. Sci. Rep. 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06218-8 (2017).

Buchwal, A., the, P. S. P. of & 2020. Divergence of Arctic shrub growth associated with sea ice decline. Natl. Acad. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013311117 (2020).

Thackeray, C. W. & Hall, A. An emergent constraint on future Arctic sea-ice albedo feedback. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 972–978 (2019).

Haugen, R. K. & Brown, J. Coastal-inland distributions of summer air temperature and precipitation in Northern Alaska. Arct. Alp. Res. 12, 403–412 (1980).

Hugonnet, R. et al. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 592, 726–731 (2021).

Juselius, T. et al. Newly initiated carbon stock, organic soil accumulation patterns and main driving factors in the High Arctic Svalbard, Norway. Sci. Rep. 12, 4679 (2022).

Elberling, B., Jakobsen, B. H., Berg, P., Sndergaard, J. & Sigsgaard, C. Influence of vegetation, temperature, and water content on soil carbon distribution and mineralization in four High Arctic soils. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 36, 528–538 (2004).

Nakatsubo, T., Bekku, Y. S., Uchida, M., plant, H. M. J. of & 2005. Ecosystem development and carbon cycle on a glacier foreland in the High Arctic, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. J. Plant Res. 118, 173–179 (2005).

Kabala, C. & Zapart, J. Initial soil development and carbon accumulation on moraines of the rapidly retreating Werenskiold Glacier, SW Spitsbergen, Svalbard archipelago. Geoderma 175, 9–20 (2012).

Wietrzyk-Pełka, P., Rola, K., Szymański, W. & Węgrzyn, M. H. Organic carbon accumulation in the glacier forelands with regard to variability of environmental conditions in different ecogenesis stages of High Arctic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 135151 (2020).

Moreau, M., Laffly, D. & Brossard, T. Recent spatial development of Svalbard strandflat vegetation over a period of 31 years. Polar Res. 28, 364–375 (2009).

Wietrzyk, P. et al. The relationships between soil chemical properties and vegetation succession in the aspect of changes of distance from the glacier forehead and time elapsed after glacier retreat in the Irenebreen foreland (NW Svalbard). Plant Soil 428, 195–211 (2018).

Wietrzyk-Pełka, P., Cykowska-Marzencka, B., Maruo, F., Szymański, W. & Węgrzyn, M. H. Mosses and liverworts in the glacier forelands and mature tundra of Svalbard (High Arctic): diversity, ecology, and community composition. Pol. Polar Res. 151–186 https://doi.org/10.24425/ppr.2020.133011 (2020).

Breen, K. & Lévesque, E. Proglacial succession of biological soil crusts and vascular plants: biotic interactions in the High. Arct. Can. J. Bot. 84, 1714–1731 (2006).

Dembitsky, V. M. Lipids of bryophytes. Prog. Lipid Res. 32, 281–356 (1993).

Williams, C. J., Yavitt, J. B., Wieder, R. K. & Cleavitt, N. L. Cupric oxide oxidation products of northern peat and peat-forming plants. Can. J. Bot. 76, 51–62 (1998).

Nakatsubo, T., Fujiyoshi, M., Yoshitake, S., Koizumi, H. & Uchida, M. Colonization of the polar willow Salix polaris on the early stage of succession after glacier retreat in the High Arctic, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. Polar Res. 29, 285–390 (2017).

van der Knaap, W. O. Relations between present-day pollen deposition and vegetation in Spitsbergen. Grana 29, 63–78 (1990).

Birks, H. H. Holocene vegetational history and climatic change in west Spitsbergen—plant macrofossils from Skardtjørna, an Arctic lake. Holocene 1, 209–218 (1991).

Rønning, O. I. The Flora of Svalbard. (1996).

Rozema, J. et al. A vegetation, climate and environment reconstruction based on palynological analyses of high Arctic Tundra Peat Cores (5000–6000 years BP) from Svalbard. Plant Ecol. 182, 155–173 (2006).

Glaser, P. H. Transport and Deposition of Leaves and Seeds on Tundra: A Late-Glacial Analog. Arct. Alp. Res. 13, 173 (1981).

Yang, Z. et al. Total photosynthetic biomass record between 9400 and 2200 BP and its link to temperature changes at a High Arctic site near Ny‐Ålesund, Svalbard. Polar Biol. 1–13 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02493-5 (2019).

Jankovská, V. Pollen- and non pollen palynomorphs- analyses from Svalbard. Czech Polar Rep. 7, 123–132 (2017).

Poliakova, A., Brown, A. G. & Alsos, I. G. Exotic pollen in sediments from the high Arctic Lake Tenndammen, Svalbard archipelago: diversity, sources, and transport pathways. Palynology 48, 2287005 (2024).

Owczarek, P., Opała-Owczarek, M. & Migała, K. Post−1980s shift in the sensitivity of tundra vegetation to climate revealed by the first dendrochronological record from Bear Island (Bjørnøya), western Barents Sea. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 014031 (2020).

Ji, L. & Fan, K. Regime shift of the interannual linkage between NDVI in the Arctic vegetation biome and Arctic sea ice concentration. Atmos. Res. 299, 107184 (2024).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Complexity revealed in the greening of the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 106–117 (2020).

Grimes, M., Carrivick, J. L., Smith, M. W. & Comber, A. J. Land cover changes across Greenland dominated by a doubling of vegetation in three decades. Sci. Rep. 14, 3120 (2024).

Bonnet, S., de Vernal, A., Hillaire-Marcel, C., Radi, T. & Husum, K. Variability of sea-surface temperature and sea-ice cover in the Fram Strait over the last two millennia. Mar. Micropaleontol. 74, 59–74 (2010).

Muraoka, H. et al. Photosynthetic characteristics and biomass distribution of the dominant vascular plant species in a high Arctic tundra ecosystem, Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard: implications for their role in ecosystem carbon gain. J. Plant Res. 121, 137 (2008).

Buchwal, A., Rachlewicz, G., Fonti, P., Cherubini, P. & Gärtner, H. Temperature modulates intra-plant growth of Salix polaris from a high Arctic site (Svalbard). Polar Biol. 36, 1305–1318 (2013).

Wojcik, R., Palmtag, J., Hugelius, G., Weiss, N. & Kuhry, P. Land cover and landform-based upscaling of soil organic carbon stocks on the Brøgger Peninsula, Svalbard. Arctic,. Antarct. Alp. Res. 51, 40–57 (2019).

Opała-Owczarek, M. et al. The influence of abiotic factors on the growth of two vascular plant species (Saxifraga oppositifolia and Salix polaris) in the High Arctic. CATENA 163, 219–232 (2018).

Owczarek, P. & Opała, M. Dendrochronology and extreme pointer years in the tree-ring record (AD 1951–2011) of polar willow from southwestern Spitsbergen (Svalbard, Norway). Geochronometria 43, 84–95 (2016).

Bianchi, T. S. & Canuel, E. A. Chemical biomarkers in aquatic ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400839100 (2011).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20—The Marine Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Paglia, E. A higher level of civilisation? The transformation of Ny-Ålesund from Arctic coalmining settlement in Svalbard to global environmental knowledge center at 79° North. Polar Rec. 56, e15 (2020).

Mangerud, J., Bondevik, S., Gulliksen, S., Hufthammer, A. K. & Høisæter, T. Marine 14C reservoir ages for 19th century whales and molluscs from the North Atlantic. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 3228–3245 (2006).

D'Angelo, A. Multi-year particle fluxes in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Biogeosciences 15, 5343–5363 (2018).

Mollenhauer, G., Grotheer, H., Gentz, T., Bonk, E. & Hefter, J. Standard operation procedures and performance of the MICADAS radiocarbon laboratory at Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Germany. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 496, 45–51 (2021).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. Discussion: reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S. & Damsté, J. S. S. The effect of improved chromatography on GDGT-based palaeoproxies. Org. Geochem. 93, 1–6 (2016).

Schouten, S., Forster, A., Panoto, F. E. & Damsté, J. S. S. Towards calibration of the TEX86 palaeothermometer for tropical sea surface temperatures in ancient greenhouse worlds. Org. Geochem 38, 1537–1546 (2007).

Wei, B. et al. Comparison of the U37K′, LDI, TEX86H, and RI-OH temperature proxies in sediments from the northern shelf of the South China Sea. Biogeosciences 17, 4489–4508 (2020).

Goñi, M. A. & Montgomery, S. Alkaline CuO Oxidation with a microwave digestion system: lignin analyses of geochemical samples. Anal. Chem. 72, 3116–3121 (2000).

Wood, S. N. Thin plate regression splines. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 65, 95–114 (2003).

Wood, S. N., Pya, N. & Säfken, B. Smoothing parameter and model selection for general smooth models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 111, 1548–1563 (2016).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation For Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2024).

Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 73, 3–36 (2011).

Pya, N. scam: shape constrained additive models. R package version 1.2–17. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scam (2024).

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K. & Vaughan, D. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R package version 1.1.4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (2023).

Wickham, H., Vaughan, D. & Girlich, M. tidyr: tidy messy data. R package version 1.3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr (2024).

Simpson, G. gratia: graceful ggplot-based graphics and other functions for GAMs fitted using mgcv. R package version 0.9.2. (2024).

Zeileis, A. & Grothendieck, G. Zoo: S3 infrastructure for regular and irregular time series. J. Stat. Softw. 14 (2005).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2, elegant graphics for data analysis. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4. (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2016).

Wilke, C. cowplot: streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for “ggplot2”. R package version 1.1.3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cowplot (2024).

Wickham, H., Pedersen, T. & Seidel, D. scales: scale functions for visualization. R package version 1.3.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scales (2023).

Xiao, N. ggsci: scientific journal and sci-fi themed color palettes for “ggplot2”. R package version 3.2.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggsci (2024).

Jakobsson, M. et al. The international bathymetric chart of the arctic ocean version 4.0. Sci. Data 7, 176 (2020).

Werner, K. et al. Atlantic Water advection to the eastern Fram Strait — multiproxy evidence for late Holocene variability. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 308, 264–276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work has been principally funded and conducted in the framework of the Joint Research Center ENI–CNR “Aldo Pontremoli” of Lecce, within the ENI‐CNR Joint Research Agreement. We also thank “Premio Dirigibile Italia” and “Fondazione Carisbo” (2017/0334) for their financial contribution. The Italian Artic Station “Dirigibile Italia” is kindly acknowledged for the logistic support. Olga Gavrichkova is acknowledged for providing samples of plant species from the study area, which allowed a first exploratory investigation of plant-specific biomarkers to be considered and which tundra vegetation to be sampled in detail. We further thank Piotr Owczarek and Magdalena Opała-Owczarek for providing us with the dendrochronological data of S. polaris from Svalbard. G.I., T.T., and G.M. acknowledge the Italian-German partnership on “Chronologies for Polar Paleoclimate Archives (PAIGE)” and the funding from the Helmholtz European Partnering. Finally, we thank David Naafs and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that helped to improve the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. planned the research project and activities. G.I. conceptualized the initial idea of the historical greening reconstruction from a sedimentary archive by using plant-derived biomarkers and their link with the summer sea ice decline. G.I. handled the initial structuring of the article. G.I. and T.T. wrote the article. G.I. managed the statistical modeling of the trend and all figures. G.I., A.N., M.S., and C.C. carried out the biogeochemical analysis of all samples. G.M. and J.H. contributed to the GDGT analysis, radiocarbon analysis, and interpretation of the results. S.M. and T.T. carried out the sampling activities. L.L., P.G., and F.G. participated in the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Deepak Jha, Masanobu Yamamoto, David Naafs, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kyung-Sook Yun and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ingrosso, G., Ceccarelli, C., Giglio, F. et al. Greening of Svalbard in the twentieth century driven by sea ice loss and glaciers retreat. Commun Earth Environ 6, 30 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01994-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01994-y

This article is cited by

-

Glaciers give way to new coasts

Nature Climate Change (2025)