Abstract

The Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy) is among the most productive volcanoes of the Mediterranean area. However, the volcanic history preceding the VEI 7 Campanian Ignimbrite eruption (~40 ka) is still poorly constrained. Here, we use a tephra dispersal model to reconstruct the eruption source parameters of the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption (~109 ka), one of the most widespread Late Pleistocene Mediterranean marker tephra from Campi Flegrei. Our results suggest that the eruption was characterized by an early Plinian phase involving ~6 cubic kilometers (within the range of 3–21 cubic kilometers) of magma, followed by a co-ignimbrite phase erupting ~148 cubic kilometers (range of 60–300 cubic kilometers). This ranks the Maddaloni/X-6 as a high-magnitude (M7.6) eruption, resulting at least as the second largest known event from Campi Flegrei. This study provides insights into the capability of the Campi Flegrei magmatic system to repeatedly generate large explosive eruptions, which has broad implications for hazard assessment in the central Mediterranean area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Constraining the temporal distribution and dynamics of large explosive eruptions is pivotal for assessing long-term volcanic hazards, especially in densely populated areas1, due to their potential impact on a wide regional scale.

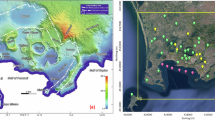

The Campi Flegrei caldera is a partially submerged volcanic field hosting a nested caldera structure2,3 (Fig. 1b), located west of the densely populated area of Naples (Italy). Its eruptive history (last 60 kyr4) has been characterized by a wide spectrum of eruptive styles and magnitudes5. The caldera-forming eruptions include the M7.7–7.8 (VEI 7) Campanian Ignimbrite6 (CI 39.9 ± 0.1 ka7), the M6.6 (VEI 6) Masseria del Monte (MdM, 29.3 ± 0.7 ka8) and the M6.8 (magnitude estimated using the volume provided in Albert et al.8, following Mason et al.9) (VEI 6) Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (NYT, 14.9 ± 0.4 ka10) eruptions.

a Simplified scheme showing the volcanic history of Campi Flegrei. b Simplified geological map of Campi Flegrei, showing the distribution of pyroclastic deposits, the outer caldera boundary and crater rims (modified with permission after Natale et al.3, co-author). c Map showing the sampling location of the deposits ascribed to the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption (yellow circles and squares). The satellite imagery was provided by Bing Maps, licensed by Microsoft, accessed on the 5th of June 2024 via QGIS open-access software 3.36.0. Yellow squares indicate the samples for which thickess data is not available. Circles are sized by their thickness in cm (Supplementary Table 1).

The presence of widely dispersed Middle-Late Pleistocene Campi Flegrei tephra in the central-eastern Mediterranean region suggests the occurrence of large explosive eruptions, with tephra markers dated at ~160 ka and between ~109 and ~93 ka11,12 and potentially dating back to ~250–290 ka (Fig. 1a).

Quantifying the eruption source parameters of these large explosive eruptions is crucial to understand the magmato-tectonic processes driving the long-term volcanic evolution, although the main ones (e.g., magnitude and intensity) are yet to be assessed.

Here, we focus on the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption from Campi Flegrei, which generated the oldest and most widespread ash layer of the eruptive cluster between ~109 and ~93 ka11 (Fig. 1a). Based on a critical review of the available stratigraphic, geochemical, and geochronological data, we used the PARFIT code13, which is based on the semi-analytical HAZMAP model14,15, to simulate the dispersion and deposition of ash and lapilli produced by sustained eruption columns16, in order to solve an inverse problem to assess the eruption source parameters and dispersal area of the eruption. This approach has been also successfully applied to a wide spectrum of eruptive styles and magnitudes15,17. Our results suggest that high-magnitude (M7) eruptions, arguably caldera-forming, occurred at Campi Flegrei before the Campanian Ignimbrite (~40 ka), and that the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption is at least the second-largest explosive event occurred in the Campi Flegrei area since ~109 ka.

The Maddaloni/X-6 tephra: stratigraphy, geochemistry and geochronology

The X-6 tephra was described for the first time by Keller et al.18 in the Ionian Sea (Fig. 1c). Later on, based on stratigraphic, geochemical and geochronological data, the X-6 tephra was recognized in several mid-proximal to distal locations within the Tyrrhenian, Adriatic and Ionian Seas12,19,20,21,22, Sulmona and Fucino basins23,24, San Gregorio Magno25,26, Lake Ohrid27,28 and Tenaghi Philippon29. These correlations considerably enlarged the dispersal area of this tephra (Fig. 1c), enhancing its potential as a relevant marker for the Mediterranean MIS 5 palaeoclimatic-environmental and archaeological records23,24.

The occurrence of the younger major Campanian Ignimbrite and Neapolitan Yellow Tuff eruptions deeply re-shaped the morphology of the Campi Flegrei caldera and surrounding areas2, burying the old deposits. For this reason, it was only recently that some mid-proximal occurrences of the X-6 tephra were found11,30. The eruption was named after the discovery of mid-proximal deposits of the X-6 tephra at Maddaloni, located ~40 km from Campi Flegrei11. The mid-proximal tephra layers occur as Plinian pumice fallout deposits, with alternating fine-grained, grey pumice lapilli and brown coarse ash, with accidental lithics and lava fragments (Monaco et al.11, original data in Di Vito et al.30). The glass from the fallout unit displays a homogeneous trachytic-phonolitic composition, with a SiO2 content of 61.6 ± 0.3 wt% (Fig. 2a), an alkali sum (K2O + Na2O) of 13.3 ± 0.3 wt%, and an alkali ratio (K2O/Na2O) of 0.9 ± 0.05 (Fig. 2a). The CaO/FeO ratio ranges between ~0.4 and 0.7, and the Cl content varies between 0.3 and 1.1 wt%, which, in addition to Sr-Nd isotope, provided evidence for a geochemical affinity with Campi Flegrei11 (Fig. 2a).

a Major element composition of the samples ascribed to the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption, including (i) TAS (Total Alkali vs Silica) diagram; (ii) CaO vs K2O/Na2O diagram, showing the HAR (high alkali ratio) and LAR (low alkali ratio) components; (iii) CaO/FeO vs Cl; (iv) SiO2 vs MgO. b Comparison between the Maddaloni/X-6 and the CI major element composition. LGdM: Lago Grande di Monticchio, GdC: Grotta del Cavallo, TP: Tenaghi Philippon. For more detailed information on the data source, the reader is referred to Supplementary Table 1.

South of the Campi Flegrei area, the mid-distal products of the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption occur as massive ash layers, up to 1 m-thick, in the Cilento area (Fig. 1c), ~120–130 km southeast of Campi Flegrei23,31. In these intermediate localities, the Maddaloni/X-6 tephra displays a wider compositional variability (e.g., SiO2 = 62.2 ± 0.8 wt%; Na2O+K2O = 12.8 ± 0.4 wt%). Particularly, the alkali ratio (K2O/Na2O) shows the most remarkable geochemical variability among the deposits, ranging from the typical low alkali ratio (LAR) values of the homogeneous Plinian fall (~ 0.9–1.0), to high alkali ratio (HAR) values, which can be as high as ~2.723,32,33 (Fig. 2a).

As also documented for the CI eruption34, the notable textural and geochemical difference among the most proximal occurrences of the Maddaloni/X-6 tephra (Fig. 2b) can be interpreted as two sub-units deriving from two eruption phases, i.e., an early Plinian phase, mainly dispersed northward, and a co-ignimbrite phase, mainly dispersed to the South and East. In this regard, the tephra found in Lago Grande di Monticchio (southern Italy) is crucial, as it reveals the key depositional features of the two main phases of the X-6 eruption in distal settings. In fact, the basal coarse-grained pumice fallout layer is overlain by a thick, fine-grained, vitric ash layer. Thus, according to their textural features, they have been interpreted as Plinian and co-ignimbrite layers, respectively32. The occurrence of a co-ignimbrite associated to a pyroclastic flow phase is also suggested by the presence of an ignimbrite deposit found at Durazzano and Maddaloni (ca. 30 km NE from Campi Flegrei) and dated at 116.1 ± 8.8 ka35, which, within the uncertainties, is consistent with the age of the Maddaloni/X-6 tephra. With this regard, further and decisive evidence is provided by the recent discovery of a > 17 m-thick, pyroclastic flow deposit (PU-1 sample) found in the subsoil (96-113 m depth) of the metropolitan area of Naples, at a drilling site located only 7 km from the eastern Campi Flegrei caldera rim36 (Ponti Rossi borehole, Fig. 1b). In fact, despite the lack of geochemical data for PU-1 does not allow a robust correlation, the 40Ar/39Ar age of this unit at 110.00 ± 0.35 ka36, which is statistically indistinguishable from the Maddaloni/X-6 age (109.3 ± 1.0 ka11), makes it the best candidate for representing the most proximal ignimbrite occurrence of the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption recognised so far36.

Therefore, the wide compositional spectrum of the X-6 tephra may reflect the compositional variability of the feeder magma during the two main eruption phases, thus providing an indirect but reliable proxy of the whole Maddaloni/X-6 magmatic system. Noteworthy, the geochemical variability of the Maddaloni/X-6 juvenile glasses display a remarkable analogy with the Campanian Ignimbrite caldera-forming event (Fig. 2b), which shows a relatively homogenous composition of the Plinian fallout horizon, and a more heterogeneous one, recorded in pyroclastic flows and breccia deposits generated during caldera collapse34,37,38 (Fig. 2b).

From a geochronological point of view, in the Mediterranean high-resolution paleoclimate records, the Maddaloni/X-6 tephra marks the onset of a stadial event of the early Marine Isotope Stage 5d, correlated to the Greenland Stadial 2511,23 which, according to the NorthGRIP GIC005 timescale, is dated to ~110.6 ka (GCC05 chronology39). The three 40Ar/39Ar ages available for the Maddaloni/X-6 tephra yield consistent ages of 108.9 ± 1.8 ka33 (Tyrrhenian Sea), 109.1 ± 0.8 ka40 (Sulmona basin) and 109.3 ± 1.0 ka11 (Campania Plain).

Results and discussion

Assessing the tephra dispersal, magnitude, and dynamics of the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption

The tephra dispersal was modelled using the PARFIT code (http://datasim.ov.ingv.it/download/parfit/download-parfit-2.3.1.html), and solving an inverse problem to calculate the input parameters with HAZMAP14,16, a semi-analytical 2D model that solves the equations for advection, diffusion, and sedimentation of particles. To constrain the inverse problem, we used tephra thickness and grain-size data from mid-proximal and distal locations (Supplementary Table 1). The calculated input parameters include the total erupted mass, column height, Suzuki coefficient (described as the mass distribution along the column16,41), total grain-size distribution (TGSD), wind profile, effective horizontal diffusion coefficient, and density of ash aggregates. A more detailed description of the methods employed in this study is provided in the “Methods” section.

The analysis of the grain-size distributions and the first set of simulations were provided considering all the data points. However, the tephra layer in Lago Grande di Monticchio, ascribed to the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption, consists of a 1.6 cm thick basal pumice layer, representing a Plinian fallout, overlain by 2 m of fine-grained vitric ash, interpreted as a co-ignimbrite32. Moreover, in agreement with the above-discussed geochemical-textural hints, the dispersal and the grain-size distribution of some deposits highlighted the presence of two different overlapping dispersal lobes, the first one towards E-NE and the second one towards E-SE. This corroborates the notion that the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption was characterized by an early Plinian phase followed by a very-large ignimbrite/co-ignimbrite phase, whose deposits can be found as far as ~850 km from the vent (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, based on all the pieces of evidence, the dispersal area was modelled using two different datasets (Supplementary Table 1). The modelling results are provided in Supplementary Table 2, along with a synthesis of the ranges of the eruption source parameters for the two phases (Table 1).

Black values on the isopachs represent the thickness in cm. The results were obtained solving an inversion problem for (a) the Plinian phase and (b) the co-ignimbrite phase. For the choice of the optimal solutions, the statistical index has been minimized (Chi2 in Supplementary Table 2) and we have accounted for performance on single sites to have the best on each location; model extrapolations have been provided on areas where observations are not available. In b, the contour of the co-ignimbrite easternmost distribution is dashed, as it falls in areas not covered by observed data points. The main eruption source parameters obtained from the model are provided in the tables at the top of each figure. The rose diagrams (top-right corners) show the variation of the wind field pattern and speed (in m/s) with elevation above sea level. On the bottom-right corners, the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption dynamics is illustrated: the first phase produces a Plinian column, with a maximum height of ~30 km and transporting materials to E-NE; the second phase produces a co-ignimbrite, associated with a potential caldera collapse, reaching ~55 km in height and transporting volcanic products to E-SE. The topographic map was obtained from Global Multi-Resolution Topography Data Synthesis (GMRT MapTool). The isopach maps showing the combination of the two phases can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The Plinian phase transported and deposited tephra fallout products towards E-NE (Fig. 3a); this phase produced a column that rose to ~30–50 km, with a best estimate of 33 km, a Suzuki coefficient (A) of 7, and a magma volume in the range of 3–21 km3 Dense Rock Equivalent (DRE), with a best estimate of 5.6 km3 DRE (Table 1).

For the co-ignimbrite phase, the calculated magma volume is ~148 km3 DRE (with the most likely range of 60–300 km3 DRE) of magma, and the plume column height was estimated at ~55 km, with a Suzuki coefficient (A) of 4. The co-ignimbrite products were dispersed predominantly towards SE (Fig. 3b). Considering the very high column heights, the mass eruption rates (MER) estimated for the Plinian and the co-ignimbrite phases exceed ~108–109 kg/s42, respectively, implying short-lived eruptive phases whose explosivity could have been enhanced by the interaction with sea water (e.g., Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai eruption43).

The calculated total volume, without considering the ignimbrite, is ~154 km3 DRE (Table 1), which corresponds to a bulk tephra volume of ~385 km3 (for a vesicularity of 60 vol% and a rock density of 2500 kg/m3), resulting into VEI 7 (Volcanic Explosivity Index44) and magnitude M7.69.

These estimations show higher values than the empirical ones recently provided by Sulpizio et al.45 (i.e., 0.5–2 km3 DRE for the Plinian phase and 4–14 km3 DRE for the co-ignimbrite phase), who assessed the minimum values for eruptions’ magnitude estimations in data scarcity cases. The recent recognition of a > 17 m-thick pyroclastic flow deposit at Ponti Rossi (north of Naples), likely originated from the continental part of Campi Flegrei36, gives reasonable ground to consider it as the ignimbrite phase of Maddaloni/X-6. In this regard, considering the above-mentioned geochemical and textural analogies with the CI eruption (Fig. 2b), and assuming the same vitric loss value of the CI (i.e., 0.656,46), within the considered uncertainties, we can speculate that the volume of the ignimbrite deposits could be as large as ~70 km3 DRE. Overall, by integrating the volumes of the Plinian, ignimbrite, and co-ignimbrite deposits, an estimated value of 223 km³ DRE can be tentatively proposed, which falls within the confidence range of the Campanian Ignimbrite volume6.

Thereby, this study provides a simulation constrained by available observations of the eruption products, and a realistic magnitude estimation for the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption. This estimate can be improved in the future by additional stratigraphic occurrences, including regions where the X-6 tephra has not been recorded yet (e.g., Anatolia and proximal settings).

Furthermore, the withdrawal of such a large amount of magma from shallow crustal levels (first 10 km of depth) is undoubtedly capable of driving a caldera collapse47,48, with surface radius up to 10 km.

However, since the oldest volcanic successions outcropping in the Campi Flegrei area date back to ~78 ka49, any volcano-tectonic evidence of a Maddaloni/X-6 caldera at the surface, or from potential field data (e.g., gravity data), is hindered. Moreover, due to the even larger CI event, it would be unlikely to see its physical structure preserved. A similar argument has been claimed for the “missing” caldera of the Masseria del Monte eruption8, which was likely obliterated by the younger and relatively large NYT eruption, along with the young volcanism. Nonetheless, the discovery of a pre-CI large-magnitude (~M7.6) eruption in the Late Pleistocene volcanic history of Campi Flegrei highlights the importance of assessing the recurrence times, the dynamics of large explosive eruptions, and the structural mechanisms promoting formation and/or reactivation of caldera structures. These are all needed to understand the magmato-tectonic processes driving the long-term volcanic and volcano-tectonic evolution, potentially posing strong impacts over a wide regional scale.

Conclusions

Previous studies highlighted the occurrence of at least two caldera-forming eruptions at Campi Flegrei, i.e., the Campanian Ignimbrite (~40 ka) and the Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (~15 ka), in addition to the large-magnitude Masseria del Monte Tuff eruption (~29 ka). In this study, we assessed the dispersal of the ~109 ka Maddaloni/X-6 eruption, which allowed us to recognize the oldest known VEI 7 eruption of the Campi Flegrei volcanic history, erupting more than ~150 km3 of magma. Despite the relatively large uncertainty, the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption may be, by a wide margin, at least the second-largest explosive event occurred in the Campi Flegrei area since 109 ka. Our results show that the eruption started with a Plinian phase that erupted ~5.6 km3 DRE and was dispersed mainly towards E-NE. A co-ignimbrite phase, as large as ~148 km3 DRE, associated with large pyroclastic currents (up to ~70 km3 DRE, likely related to a caldera collapse event), was dispersed over a wider area of the central and eastern Mediterranean region. The information we provided for the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption sheds new light on the occurrence of large eruptions at Campi Flegrei, indicating that the caldera history extends back in time well beyond the previously assumed limit of the ~40 ka Campanian Ignimbrite. The occurrence of numerous pre-CI and pre-Maddaloni/X-6 tephra ascribed to the Campi Flegrei lays the groundwork for encouraging and deepening the knowledge on the ancient history of this restless volcano and to keep pursuing the assessment of the long-term volcanic hazard by fostering research in the sub-surface geology of this volcanic region.

Methods

Tephra dispersal for the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption deposits was simulated using HAZMAP, a semi-analytical 2D model which solves the equations for advection, diffusion, and sedimentation of particles14,16. The input parameters were obtained by best fitting both meteorological conditions and volcanological parameters. To constrain the inverse problem, we used tephra thickness and grain-size data from mid-proximal and distal locations (Supplementary Table 1). The dataset includes the grain-size data provided by Fernandez et al.12 and by Di Vito et al.30. After a critical review of the available data, thickness values from some localities were not included in the model, either because of their unavailability (i.e., only the geochemical and geochronological data is available), or because of the unsuitability of the sedimentary settings, such as caves, steep slopes, shallow-water ponds (e.g., San Gregorio Magno26 and Cavallo Cave50), in reliably preserving the primary thickness and grain-size, due to the common secondary surface processes like remobilization, redeposition and/or erosion. Additional sources of uncertainty related to the reconstruction of the bulk granulometries need to be considered as well, such as the different tephra lithologies or the paucity of grain-size data15,51. For this reason, different estimations of the Total Grain Size Distribution (TGSD) were obtained through the Voronoi tessellation method52, following the empirical method of Costa et al.53, who relates TGSD to magma composition and eruption intensity, or through the inversion the local grain size data15,54.

The thickness and grain-size data from the available sites were used to obtain, through the solution of an inverse problem using the code PARFIT, the input parameters for the semi-analytical model HAZMAP14. Since the model is based on simplified assumptions, such as a spatially uniform, constant wind profile and turbulent diffusion, the inferred parameters must be intended as effective values related to the two eruption phases. The results provided here were obtained by best fitting the available measurements (Supplementary Table 2), following the method of Costa et al.17, Bonasia et al.15, and Albert et al.8.

The model assumes that the dispersion and deposition of particles is only governed by gravitational settling, horizontal eddy diffusion, and wind advection, to assess the magnitude and dynamics of a given eruption14,16. Like in Matthews et al.55, we aim to estimate an effective source term valid far from the vent (i.e., at distances larger than the column height), determining the mass distribution within the column using an empirical parameterization16,41, which considers the column shape parameter (A) and the column height (H) determined by the inversion. The model gave isopach maps that account for tephra deposition in terms of mass loading (kg m-2), that were converted into thickness. A constant bulk deposit density of 1000 kg m-3 was assumed to convert mass loading to thickness and vice versa17. The particle density we considered is a typical value for old Campi Flegrei deposits43 and does not represent a large source of uncertainty in the final estimations17.

The volcanological input parameters (i.e., eruption source parameters) required for the semi-analytical tephra dispersal model include total erupted mass, column height, mass distribution along the column (described through the Suzuki distribution16,41), total grain-size distribution (TGSD), wind profile, effective horizontal diffusion coefficient (the vertical components of wind and turbulent diffusion are neglected), and density of ash aggregates. They are all calculated through the best fit of the observed deposit thickness and granulometry. The modelling results demonstrated that if all ash fell as individual particles, most of it would settle beyond the investigated area and hence. Indeed, the deposition of most fine ash occurs by fallout as aggregates56,57,58.

Concerning particles finer than 63 microns, they were modelled as aggregates following Cornell et al.56, originally proposed for the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption. The best results for the aggregate class were obtained considering a value of 400 kg m-3 for the Plinian deposits and 200 kg m-3 for the co-ignimbrite ones (Supplementary Table 2). To reconstruct all the eruption source parameters at the time of the eruption, they were estimated by minimizing the difference between observed and modelled thickness17,55 (Supplementary Fig. 2) minimizing the function (1):

Where wi is a weighting factor, N is the number of data points, and Ti (obs) and Ti (mod) are observed and calculated thickness values, respectively. Weighting factors wi depend on the distribution of errors on the dependent variable. When wi = 1 is used, all values have the same weight (i.e., absolute squared error), when wi = 1/T 2 (obs) is used the relative squared errors are minimised (i.e., proportional weight), and when wi = 1/T(obs) a statistical weight, which assumes a Poissonian distribution, is considered.

The wind field at the time of the eruption is unknown and, with our approach, it can only be tentatively reconstructed from field data in terms of an effective average profile. For a large domain like the one affected by the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption, the modelling is based on an average wind profile over the domain, instead of the actual wind field. The settling velocity model by Ganser59 was chosen for the modelling. The computational domain extends from 35° N to 44° N and from 10° E to 26° E, spanning from the central Tyrrhenian Sea, where ~cm-thick ash layers were found, to Tenaghi Philippon (Greece), where a cryptotephra was identified29.

For the meteorological conditions we considered a dataset of daily wind profiles from 1971 to 2020 (50 years) taken from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5. We assume that this collection of modern wind fields may statistically approximate those at the time of the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption.

The TGSD was estimated using different methods, and the results were compared (Supplementary Fig. 3) to check the outcomes of the different approaches. The first method was the Voronoi tessellation method of Bonadonna and Houghton52. For each phase, a dataset including the grain-size distribution of each sample and an estimation of the zero line (defined as the isopach where tephra thickness can be assumed negligible) was created. Two different TGSD, one for the Plinian phase and the other one for the co-ignimbrite were calculated (Supplementary Fig. 3) using the TOTGS code60. However, since for a Late Pleistocene eruption like Maddaloni/X-6 proximal data are missing, either because they were eroded or they were obliterated by subsequent eruptions, the reconstructed TGSD may not be representative of the coarse components of the distribution.

The second method used for TGSD calculation was the one proposed by Costa et al.53, whose estimations are based on the magma viscosity and intensity of the eruption. As input parameters we consider an estimation of the reference column height, and the magma viscosity estimated for the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption. Magma viscosity was calculated using the method of Giordano et al.61, based on the average glass composition available in the literature for the Maddaloni eruption11,12,62. The average glass compositions (volatile-free) were separated considering the samples ascribable to one phase or another. Since water content (wt %), T (°C) and crystal fraction for the Maddaloni/X-6 eruption are not available in the literature, the values provided by Forni et al.63 for the CI eruption were considered as reference values. Specifically, Forni et al.63 calculated melt-H2O contents ranging from 4 to 6 wt% and temperatures of ~880–972 °C for crystal-poor units, melt-H2O contents of 3–5 wt% and temperatures of ~945–1070 °C for crystal-rich units. Using the average glass composition for the Maddaloni eruption, 4 wt% of melt-H2O content and a T of ~880 °C, the Giordano et al.61 method gives a viscosity of ~106 Pa s for both phases. The effects of crystals on magma viscosity17,64 were neglected. Considering such a magma viscosity and reference column heights obtained through the modelling, we can calculate the TGSD following Costa et al.53.

Finally, the reconstruction obtained by solving the inverse problem constrained by available local GSD through PARFIT15 was also considered.

The TGSD estimations are quite similar (Supplementary Fig. 3), even though there are some differences in the mode (within the error range) and noticeable differences in the distribution of the coarse fraction, due to the lack of proximal samples in the dataset. The volume estimation has a large uncertainty and was estimated through several sensitivity tests. Among the models we obtained, we chose the one that shows the best-fit in terms of dispersal and correlation between the simulated and the observed data (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). It is important to stress that the intrinsic inter-dependency of the tephra model input parameters implies that the best-fit solution is not unique, and we need to account for large uncertainties15,65,66. For further information on the modelling approach and its limitations the reader is referred to Costa et al.17, Bonasia et al.15, and Matthews et al.55.

The results are provided in Supplementary Table 2 and a synthesis of the ranges of eruption source parameters for the two phases is in Table 1. For the choice of the optimal solutions, beside the statistical index to be minimized (Chi2 in Supplementary Table 2) we have also accounted for performance on the single sites, to have the best on each location, and volcanological arguments (e.g., model extrapolations on areas where observations are not available).

The horizontal diffusion coefficient, K, was approximated by fitting to the observed thickness data, and represents an empirical parameter accounting for the physical effects that dispersed the volcanic particles (atmospheric turbulence, eruption column turbulence, wind shear14,16). The settling velocity model by Ganser59 was chosen for modelling particle terminal velocities.

Data availability

The data used in this study are all published data and all the sources of information are reported and cited in the Supplementary Information. Data sharing not applicable to this article as no original datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. The input files used for the Maddaloni/X-6 modelling is also provided in the OSF repository: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KHX4P.

Change history

05 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02069-8

References

Rougier, J., Sparks, R. S. J., Cashman, K. V. & Brown, S. K. The global magnitude–frequency relationship for large explosive volcanic eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 621–629 (2018).

Vitale, S. & Isaia, R. Fractures and faults in volcanic rocks (Campi Flegrei, southern Italy): insight into volcano-tectonic processes. Int. J. Earth Sci. 103, 801–819 (2014).

Natale, J., Vitale, S., Repola, L., Monti, L. & Isaia, R. Geomorphic analysis of digital elevation model generated from vintage aerial photographs: A glance at the pre-urbanization morphology of the active Campi Flegrei caldera. Geomorphology 460, 109267 (2024).

Orsi, G., De Vita, S. & Di Vito, M. The restless, resurgent Campi Flegrei nested caldera (Italy): constraints on its evolution and configuration. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 74, 179–214 (1996).

Vineberg, S. O., Isaia, R., Albert, P. G., Brown, R. J. & Smith, V. C. Insights into the explosive eruption history of Campanian volcanoes prior to the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 443, 107915 (2023).

Silleni, A., Giordano, G., Isaia, R. & Ort, M. H. The magnitude of the 39.8 ka Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, Italy: method, uncertainties and errors. Front. Earth Sci. 8, 543399 (2020).

Giaccio, B., Hajdas, I., Isaia, R., Deino, A. & Nomade, S. High-precision 14C and 40Ar/39Ar dating of the Campanian Ignimbrite (Y-5) reconciles the time-scales of climatic-cultural processes at 40 ka. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017a).

Albert, P. G. et al. Evidence for a large-magnitude eruption from Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy) at 29 ka. Geol 47, 595–599 (2019).

Mason, B. G., Pyle, D. M. & Oppenheimer, C. The size and frequency of the largest explosive eruptions on Earth. Bull. Volcanol. 66, 735–748 (2004).

Deino, A. L., Orsi, G., de Vita, S. & Piochi, M. The age of the Neapolitan Yellow Tuff caldera-forming eruption (Campi Flegrei caldera–Italy) assessed by 40Ar/39Ar dating method. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 133, 157–170 (2004).

Monaco, L. et al. Linking the Mediterranean MIS 5 tephra markers to Campi Flegrei (southern Italy) 109–92 ka explosive activity and refining the chronology of MIS 5c-d millennial-scale climate variability. Global Planet. Change. 211, 103785 (2022).

Fernandez, G. et al. New constraints on the Middle-Late Pleistocene Campi Flegrei explosive activity and Mediterranean tephrostratigraphy (∼ 160 ka and 110–90 ka). Quat. Sci. Rev. 331, 108623 (2024).

Macedonio, G., & Costa, A. PARFIT-2.1 (2014).

Macedonio, G., Costa, A. & Longo, A. A computer model for volcanic ash fallout and assessment of subsequent hazard. Comput. Geosci. 31, 837–845 (2005).

Bonasia, R., Macedonio, G., Costa, A., Mele, D. & Sulpizio, R. Numerical inversion and analysis of tephra fallout deposits from the 472 AD sub-Plinian eruption at Vesuvius (Italy) through a new best-fit procedure. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 189, 238–246 (2010).

Pfeiffer, T., Costa, A. & Macedonio, G. A model for the numerical simulation of tephra fall deposits. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 140, 273–294 (2005).

Costa, A. et al. Tephra fallout hazard assessment at the Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 71, 259–273 (2009).

Keller, J., Ryan, W. B. F., Ninkovich, D. & Altherr, R. Explosive volcanic activity in the Mediterranean over the past 200,000 yr as recorded in deep-sea sediments. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 89, 591–604 (1978).

Paterne, M. et al. A 90,000–200,000 yrs marine tephra record of Italian volcanic activity in the Central Mediterranean Sea. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 177, 187–196 (2008).

Bourne, A. J. et al. Tephrochronology of core PRAD 1-2 from the Adriatic Sea: insights into Italian explosive volcanism for the period 200–80 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 116, 28–43 (2015).

Insinga, D. D. et al. Tephrochronology of the astronomically-tuned KC01B deep-sea core, Ionian Sea: insights into the explosive activity of the Central Mediterranean area during the last 200 ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 85, 63–84 (2014).

Vakhrameeva, P. et al. Land-sea correlations in the Eastern Mediterranean region over the past c. 800 kyr based on macro-and cryptotephras from ODP Site 964 (Ionian Basin). Quat. Sci. Rev. 255, 106811 (2021).

Giaccio, B. et al. The late MIS 5 Mediterranean tephra markers: a reappraisal from peninsular Italy terrestrial records. Quat. Sci. Rev. 56, 31–45 (2012).

Regattieri, E. et al. Hydrological variability over the Apennines during the Early Last Glacial precession minimum, as revealed by a stable isotope record from Sulmona basin, Central Italy. J. Quat. Sci. 30, 19–31 (2015).

Munno, R. & Petrosino, P. The late Quaternary tephrostratigraphical record of the San Gregorio Magno basin (southern Italy). J. Quat. Sci. 22, 247–266 (2007).

Petrosino, P. et al. The San Gregorio Magno lacustrine basin (Campania, southern Italy): improved characterization of the tephrostratigraphic markers based on trace elements and isotopic data. Journal of Quaternary Science 34, 393–404 (2019).

Sulpizio, R., Zanchetta, G., D’Orazio, M., Vogel, H. & Wagner, B. Tephrostratigraphy and tephrochronology of lakes Ohrid and Prespa, Balkans. BG 7, 3273–3288 (2010).

Leicher, N. et al. First tephrostratigraphic results of the DEEP site record from Lake Ohrid (Macedonia and Albania). Biogeosciences 13, 2151–2178 (2016).

Wulf, S. et al. The marine isotope stage 1–5 cryptotephra record of Tenaghi Philippon, Greece: Towards a detailed tephrostratigraphic framework for the Eastern Mediterranean region. Quat. Sci. Rev. 186, 236–262 (2018).

Di Vito, M. A., Sulpizio, R., Zanchetta, G. & D’Orazio, M. The late Pleistocene pyroclastic deposits of the Campanian Plain: new insights into the explosive activity of Neapolitan volcanoes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 177, 19–48 (2008).

Donato, P., Albert, P. G., Crocitti, M., De Rosa, R. & Menzies, M. A. Tephra layers along the southern Tyrrhenian coast of Italy: links to the X-5 & X-6 using volcanic glass geochemistry. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 317, 30–41 (2016).

Wulf, S. et al. The 100–133 ka record of Italian explosive volcanism and revised tephrochronology of Lago Grande di Monticchio. Quat. Sci. Rev. 58, 104–123 (2012).

Iorio, M. et al. Combined palaeomagnetic secular variation and petrophysical records to time-constrain geological and hazardous events: An example from the eastern Tyrrhenian Sea over the last 120 ka. Global planet. change. 113, 91–109 (2014).

Smith, V. C., Isaia, R., Engwell, S. L. & Albert, P. G. Tephra dispersal during the Campanian Ignimbrite (Italy) eruption: implications for ultra-distal ash transport during the large caldera-forming eruption. Bull. Volcanol. 78, 1–15 (2016).

Rolandi, G., Bellucci, F., Heizler, M. T., Belkin, H. E. & De Vivo, B. Tectonic controls on the genesis of ignimbrites from the Campanian Volcanic Zone, southern Italy. Mineral. Petrol. 79, 3–31 (2003).

Sparice, D. et al. The pre-Campi Flegrei caldera (> 40 ka) explosive volcanic record in the Neapolitan Volcanic Area: New insights from a scientific drilling north of Naples, southern Italy. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 455, 108209 (2024).

Pappalardo, L., Ottolini, L. & Mastrolorenzo, G. The Campanian Ignimbrite (southern Italy) geochemical zoning: insight on the generation of a super-eruption from catastrophic differentiation and fast withdrawal. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 156, 1–26 (2008).

Gallo, R. I. et al. Reconciling complex stratigraphic frameworks reveals temporally and geographically variable depositional patterns of the Campanian Ignimbrite. Geosphere 20, 1–22 (2024).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. rev. 106, 14–28 (2014).

Regattieri, E. et al. A Last Interglacial record of environmental changes from the Sulmona Basin (central Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 472, 51–66 (2017).

Suzuki, T. A theoretical model for dispersion of tephra. Arc volcanism: physics and tectonics 113, 95–113 (1983).

Mastin, L. G. Testing the accuracy of a 1‐D volcanic plume model in estimating mass eruption rate. J. Geophys. Res: Atm. 119, 2474–2495 (2014).

Alvarez, R. & Camacho, M. Plumbing System of Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai Volcano. J. Earth Sci. 34, 706–716 (2023).

Newhall, C. G. & Self, S. The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) an estimate of explosive magnitude for historical volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 1231–1238 (1982).

Sulpizio, R., Costa, A., Massaro, S., Selva, J. & Billotta, E. Assessing volumes of tephra fallout deposits: a simplified method for data scarcity cases. Bull. Volcanol. 86, 62 (2024).

Scarpati, C., Sparice, D. & Perrotta, A. A crystal concentration method for calculating ignimbrite volume from distal ash-fall deposits and a reappraisal of the magnitude of the Campanian Ignimbrite. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 280, 67–75 (2014).

Roche, O. & Druitt, T. H. Onset of caldera collapse during ignimbrite eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 191, 191–202 (2001).

Geshi, N., Ruch, J. & Acocella, V. Evaluating volumes for magma chambers and magma withdrawn for caldera collapse. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 396, 107–115 (2014).

Scarpati, C., Perrotta, A., Lepore, S. & Calvert, A. Eruptive history of Neapolitan volcanoes: constraints from 40Ar–39Ar dating. Geol. Mag. 150, 412–425 (2013).

Zanchetta, G., Giaccio, B., Bini, M. & Sarti, L. Tephrostratigraphy of Grotta del Cavallo, Southern Italy: Insights on the chronology of Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition in the Mediterranean. Quat. Sci. Rev. 182, 65–77 (2018).

Mele, D. et al. Total grain size distribution of components of fallout deposits and implications for magma fragmentation mechanisms: examples from Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 82, 1–12 (2020).

Bonadonna, C. & Houghton, B. F. Total grain-size distribution and volume of tephra-fall deposits. Bull. Volcanol. 67, 441–456 (2005).

Costa, A., Pioli, L. & Bonadonna, C. Assessing tephra total grain-size distribution: Insights from field data analysis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 443, 90–107 (2016).

Volentik, A. C., Bonadonna, C., Connor, C. B., Connor, L. J. & Rosi, M. Modeling tephra dispersal in absence of wind: Insights from the climactic phase of the 2450 BP Plinian eruption of Pululagua volcano (Ecuador). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 193, 117–136 (2010).

Matthews, N. E. et al. Ultra-distal tephra deposits from super-eruptions: examples from Toba, Indonesia and Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand. Quat. Int. 258, 54–79 (2012).

Cornell, W., Carey, S. & Sigurdsson, H. Computer simulation of transport and deposition of the Campanian Y-5 ash. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 17, 89–109 (1983).

Costa, A., Folch, A., & Macedonio, G. A model for wet aggregation of ash particles in volcanic plumes and clouds: 1. Theoretical formulation. J. Geophys. Res: Solid Earth. 115 (2010).

Folch, A., Costa, A., Durant, A., & Macedonio, G. A model for wet aggregation of ash particles in volcanic plumes and clouds: 2. Model application. J. Geophys. Res: Solid Earth. 115 (2010).

Ganser, G. H. A rational approach to drag prediction of spherical and nonspherical particles. Powder technol 77, 143–152 (1993).

Biass, S., & Bonadonna, C. TOTGS: total grainsize distribution of tephra fallout. URL https://vhub.org/resources/3297 (2014).

Giordano, D., Russell, J. K. & Dingwell, D. B. Viscosity of magmatic liquids: a model. Eart Planet. Sci. Lett. 271, 123–134 (2008).

Tomlinson, E. L., Albert, P. G., & Menzies, M. A. Tephrochronology and Geochemistry of Tephra from the Campi Flegrei Volcanic Field, Italy, in Campi Flegrei: A Restless Caldera in a Densely Populated Area. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 151-174 (2022).

Forni, F., Degruyter, W., Bachmann, O., De Astis, G. & Mollo, S. Long-term magmatic evolution reveals the beginning of a new caldera cycle at Campi Flegrei. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat9401 (2018).

Frontoni, A., Costa, A., Vona, A. & Romano, C. A comprehensive database of crystal-bearing magmas for the calibration of a rheological model. Sci. Data. 9, 247 (2022).

Connor, L. J. & Connor, C. B. Inversion is the key to dispersion: understanding eruption dynamics by inverting tephra fallout, in Statistics in Volcanology. Geol. Soc., London, Special Publications of IAVCEI. 1, 231–242 (2006).

Marti, A., Folch, A., Costa, A. & Engwell, S. Reconstructing the plinian and co-ignimbrite sources of large volcanic eruptions: A novel approach for the Campanian Ignimbrite. Sci. Rep. 6, 21220 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The research was partially supported by “Sapienza” University of Rome, and by the COMET project (PRIN 2022; grant 2022MS9KWR) financed by the MUR. This research was financially supported by the project “The onset of alkaline-potassium magmatism in central Italy: how, when and why?” (PI: G. S.), funded by “Sapienza” University of Rome (Year 2020; prot. RM120172B9B69EB0). AC thanks the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Italy, grant “Progetto INGV Pianeta Dinamico” (code CUP D53J19000170001) funded by Italian Ministry MIUR (“Fondo Finalizzato al rilancio degli investimenti delle amministrazioni centrali dello Stato e allo sviluppo del Paese,” legge 145/2018) and the PRIN INSIGHT Project (CP 2022/9MH9AA, CUP: H53D23001490006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.F. led the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation and writing. A.C. led the modelling, assisted in choosing the methodology, writing and editing the manuscript. B.G. helped with the conceptualization, writing and editing, and improved figure drafting. J. N. assisted with writing and discussing the data, editing and improving the figures. D.M.P. helped to write and review the manuscript. G.S. helped with the conceptualization, writing and editing. All authors gave the final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks David Pyle and Gert Lube for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Candice Bedford and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandez, G., Costa, A., Giaccio, B. et al. The Maddaloni/X-6 eruption stands out as one of the major events during the Late Pleistocene at Campi Flegrei. Commun Earth Environ 6, 27 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01998-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-01998-8

This article is cited by

-

Magma chamber failure and dyke injection threshold for magma-driven unrest at Campi Flegrei caldera

Nature Communications (2025)