Abstract

Understanding river water quality trajectories and drivers is crucial for effective environmental management. Here we present a comprehensive nation-wide water quality trend assessment across Australia with 287 catchments from 2000 to 2019. About half of the catchments show significant trends in the flow-normalised concentration for each parameter analysed. Most of these significant trends are due to changes in concentration-flow relationships rather than long-term trends in flow. Two of Australia’s major river basins show opposing regional patterns in their significant trends. The North East Coast, which largely flows into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, has increasing phosphorus and sediments. This potentially reflects lagged effects of increasing land clearing and fertilisation since 1960s, while land improvement in the region has not yet demonstrated improvement on water quality. The Murray-Darling Basin has decreasing salinity, phosphorus, and sediment, likely driven by effects of a region-scale salinity management interventions and a prolonged drought on catchment processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inland water quality varies both spatially and temporally due to the interaction of hydro-climatic conditions (e.g., streamflow, rainfall, groundwater inputs, air and water temperature1,2,3), catchment properties (e.g., topography, soils, and land cover properties4) and disturbances (e.g., land management and wildfire5,6). The analysis of long-term variations of water quality in rivers and streams enables us to quantitatively assess how riverine water quality responds to these natural and anthropogenic stressors over time. Furthermore, establishing links between water quality variations and local, regional, and global changes is crucial to improve understanding of how natural stressors and management decisions affect water quality. This understanding is vital for effective planning to ensure future water security and ecosystem health7,8. To date, there are emerging efforts to study long-term trends in water quality at large spatial scales, such as across the United States, Europe, China, New Zealand, and Japan7,8,9,10,11. In Australia, there are some regional-scale studies on water quality trends focusing on the southeastern part of the country12,13,14. However, a comprehensive, nation-wide assessment of water quality trends is still lacking.

Australia encompasses a wide range of climates, with most of the world’s climate zones present15. There is a large variability in the hydrology of Australian rivers, along with the contrasting features of river networks and landscape conditions of Australian catchments16,17. This offers a large sample of contrasting water quality and catchment conditions18,19,20 and high scientific value for understanding water quality trends across the nation and their potential drivers. A number of Australia’s major river basins (as mapped in Fig. S1, Supplementary Information) are of key significance for water security, the economy and environment. For example, the Murray-Darling Basin is home to more than 2.3 million people, and supports about a third of the Australian food production. Another region, the North East Coast, has most of its area (except for a very small region along its south-eastern border) flowing into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, a World Heritage-listed area which sustains the largest coral reef ecosystem on Earth.

Since European colonisation, Australia’s rivers and catchments have undergone substantial changes caused by anthropogenic activities, such as clearing of native vegetation for agriculture and urbanisation, which have led to increases in agricultural runoff, soil erosion, and salinity in soils and rivers21. In addition, Australia’s catchments are also heavily influenced by climate change and substantial natural variability in their hydro-climatic conditions, demonstrated by evident responses to droughts, floods, and other climate extremes14,22,23,24. All of these drivers are expected to impact riverine water quality, and the effort required in managing deteriorating water quality is never trivial. For example, the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem is challenged by climate change and pollutants discharged from inland catchments., with an estimated cost of A$5–10 billion per annum between 2016 and 2025 to achieve the targeted reduction in pollutant load25. In the Murray-Darling Basin, increasing soil and river salinity have caused substantial environmental and economic issues, which led to implementation of various salinity management programmes for over 30 years26. The complexity and significance of various water quality issues in Australia highlight several scientific and management questions, including: Is water quality improving or deteriorating in major river basins in Australia? Are these changes linked to changes in land use and land cover over time? Have management interventions led to improving water quality, or are the effects of new management practices yet to be realised?

These questions can be informed by investigating the long-term trends of water quality across Australia. Conventional approaches for assessing trends in pollutant concentrations are often based on models that assume a monotonic trend over the full record of analysis. Examples include the Mann-Kendall and Sen’s slope approaches, which are useful in summarising water quality patterns and trajectories at large spatial scales9,10,11. However, water quality dynamics are often complex and non-linear; therefore, the underlying assumptions of these statistical approaches are often not met27. Further, the relationship between concentration and its predominant driver, streamflow, is often variable between flow events and across seasons and years, due to changes in streamflow magnitude and the partition between surface and subsurface flow28,29,30,31,32. Accounting for such time-varying trends and impacts of streamflow are beyond the capability of conventional, monotonic trend tests10,30,32.

To this end, the Weighted Regressions on Time, Discharge, and Season (WRTDS) model has emerged as a powerful tool to incorporate non-monotonic temporal trend in pollutant concentrations while allowing time-varying relationships between concentration and flow33,34. WRTDS has been applied in many large-scale trend studies, including regional and continental-scale studies for rivers across the United States. These studies revealed regional and nation-wide patterns in water quality trends and their drivers, supporting and guiding further management decisions7,33,35. A particularly attractive feature of WRTDS is the ability to identify the underlying water quality signals by removing the influence of inter-annual streamflow variability on pollutant concentration (or load). This is via calculating the trend of the flow-normalised concentration (or load) rather than the so-called ‘true-condition’ of concentration (or load)33. This flow-normalisation approach means that the estimated trends reflect the ‘underlying long-term signal’ in water quality, which is not sensitive to the inter-annual variation of hydrological conditions over the analysis period33.

A major challenge in interpreting water quality trends has been the detection of management-relevant signals under non-stationary climatic and hydrologic conditions. The recent advancement of WRTDS also provides an effective way to tackle this challenge using the so-called, generalised flow-normalisation approach, which allows us to partition the total flow-normalised trend in concentration (or load) into two components that are driven by long-term changes in streamflow and long-term changes in the relationship between concentration and flow. The latter can be attributed to management interventions, changes in catchment conditions (e.g., land use) and/or other human activities36. Although this partitioning of trends cannot identify more specific drivers of the trends other than suggesting the relative importance of the two broader categories (changes in streamflow or changes in the concentration-flow relationship), this is a first step towards narrowing down the potential causes of water quality changes and pinpointing potential management priorities7,37.

To date, studies on water quality trends in Australia are largely limited to local, basin or regional scales6,12,13,14,30,38,39, which can be in part due to the general lack of easily accessible long-term river water quality monitoring data across the nation. A nation-wide large-scale assessment of water quality trends is in pressing need to address the abovementioned scientific and management questions and guide Australia’s future water security and ecosystem health management. This study presents the first assessment of river water quality trends across the entire Australia to the best of our knowledge. Specifically, we utilise the WRTDS model as the most advanced approach to date for analysing and water quality trends, and focus on three questions about Australian water quality trends in the recent two decades (2000–2019):

-

1.

What are the long-term water quality trends across Australia?

-

2.

How do water quality trends vary across regions and if so, what explains these differences?

-

3.

How did water quality trends vary year-to-year?

We addressed these research questions by compiling a nationwide long-term water quality and streamflow dataset, and estimating the flow-normalised trends, for the concentrations/values of electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP) and total suspended solid (TSS). The trends were estimated between 2000 and 2019 for a total of 287 catchments across Australia (see a map in Fig. S2), using the WRTDS model, as detailed in the Methods.

Results

What are the long-term water quality trends across Australia?

Up to half of Australia’s catchments analysed for each water quality parameter have statistically significant trends in the flow-normalised concentration, between 2000 and 2019 (Fig. 1a). Within the catchments with significant trends, there is a similar number of catchments with increasing and decreasing trends for DO, EC, and TP. For TN, there are more catchments with significant increases (60%) than significant decreases. For TSS, the majority of catchments with significant trends were decreasing (86%).

Each panel contains the summary of site-level trend types for the five water quality parameters across Australia (a) and within each of the eight major river basins where long-term water quality data is present (b–i). The river basins are ordered by the total number of sites analysed. The total number of catchments analysed are shown as labels on the top for each region/parameter.

When grouping the significant trends by parameters and major river basins, the dominant type of trend for each parameter and each region can inform the improvement or deterioration of waterway conditions. Specifically, improving conditions of water quality are characterised by increasing DO, and decreasing EC, TN, TP and TSS, while deteriorating conditions are characterised by opposite trends to the former. Here we summarise the dominant type of significant trends for each region in Table 1.

Briefly, the significant trends within the South East Coast (Victoria (VIC)) and North East Coast (which largely flows into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon) highlight an overall deterioration in water quality. In contrast, the significant trends within the Murray-Darling Basin generally suggest an improvement in water quality. The highest number of catchments having statistically significant trends are found in the South East Coast (VIC), Murray-Darling Basin and the North East Coast, with each region having at least 10 catchments with significant trends detected for multiple parameters (Fig. 2). This reflects the geographical bias of water quality monitoring in Australia, with substantially greater coverage and higher density of water quality monitoring stations in wetter regions18, which is partly due to the higher density of perennial rivers in these regions17. In contrast, for the remaining five regions, namely South West Coast, South East Coast (New South Wales (NSW)), Tasmania, Carpentaria Coast and Lake Eyre Basin, there is generally a substantial lack of long-term monitoring sites which largely limits our conclusion on large-scale patterns of water quality deterioration or improvement. Considering this, instead of all eight major regions, we focus on the three regions which have the most sites with significant trends for the subsequent discussion of regional trend patterns, namely, South East Coast (VIC), Murray-Darling Basin and the North East Coast.

The panel titles denote the total number of catchments analysed and the number of catchments with significantly increasing/decreasing trends. The background colours highlight the major river basins in Australia (data Source: Bureau of Meteorology54) where data presents for each parameter, where white indicate basins with no catchment having sufficient data available for trend analysis.

The subsequent section presents detailed results for the three major regions.

How do water quality trends vary across regions and if so, what explains these differences?

For each water quality parameter, 90% of the catchments with significant trends have changed within ±8% per year between 2000 and 2019 relative to the first year of analysis, i.e. the year 2000 (Fig. 3). However, within this we see statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences in the magnitude of trends of DO, EC, TP, and TSS across the three major regions analysed, as suggested by the Kruskal-Wallis test. The previous results on trend direction highlight contrasting regional patterns especially between the North East Coast and the Murray–Darling Basin (Figs. 1, 2), and such regional contrasts are again seen in the trend magnitudes. Specifically, the North East Coast has substantially higher increases in TP and TSS, and slightly higher increasing trends in EC, compared to the other two regions. The Murray-Darling Basin has the greatest decreases in EC, TP and TSS, although TN has been trending up in general. The water quality trends generally are smaller in magnitudes within the South East Coast region compared to the other two regions.

Each panel summaries the significant trends in each water quality parameter as percentage changes per year relative to the level of year 2000, which are grouped in three boxes by the three key regions analysed. Each panel title denotes the parameter and total number of catchments analysed across the three regions, along with the results of Kruskal-Wallis test (p-values) to identify statistically significant variability in the trend magnitudes. The number of catchments with significant trends included each region is shown in annotation above the x-axes for each parameter. The centre line and whiskers of each box indicate the median and 1.5 times the interquartile ranges of values.

The above trends estimated focused on the flow-normalised concentrations, by which we eliminated the effect of the inter-annual variability in streamflow. As such, the estimated water quality trends can be driven by either (a) non-stationarity in streamflow (i.e., long-term trends in streamflow); and (b) changes in the concentration-flow relationship, over the two decades7,37, which allows further attribution of the trends to their potential drivers. Following a WRTDS-based trend decomposition36 (see details in Methods), we found that for most water quality parameters and catchments within the three key regions (i.e., Murray–Darling Basin, South East Coast VIC and North East Coast), the impacts of long-term streamflow trends generally only account for a small proportion of the water quality trends (Fig. 4). Specifically, for most (80%) of catchments analysed for any parameter, long-term changes in streamflow explain only up to 20.5% of water quality trends, highlighting that the majority (i.e., over 79.5%) of the water quality trends can be attributed to changes in the concentration-flow relationship. This reflects the potential effects of changes in catchment conditions and processes, as well as human activities and management. Even for the North East Coast where we see the strongest flow effects on the TSS trends, the median impact of long-term streamflow trends across all catchments makes only 15% of the water quality trends. There are only two catchments (one for TP and one for EC) where the changes in flow are more important in controlling water quality trends than the changes in the concentration-flow relationship.

The two trend components sum to 100% for each catchment. Results are grouped by parameters in panels, while the x-axis shows the three key regions analysed in three boxes (SE Coast (VIC) – South East Coast (Victoria); MDB – Murray–Darling Basin; NE Coast – North East Coast). The boxes show the range of each trend component across catchments. Note that a trend component may exceed 100% of the water quality trend when some of its effect is cancelled out by the other trend component which has the opposite direction of effect on the water quality trends i.e., the two trend components are counteracting the effect of each other. The centre line and whiskers of each box indicate the median and 1.5 times the interquartile ranges of values.

These results highlight that the majority of significant water quality trends between 2000 and 2019 are attributed to changes in the relationship between flow and concentration, which can be due to changes in the sources, mobilisation, and transport processes of individual water-quality parameters. In turn, these changes can be related to changes in land use, anthropogenic disturbances, and/or management practices. This finding is consistent with previous studies on water quality trend attribution in Europe and the continental United States across a multiple climate zones. Specifically, studies which also employed the WRTDS model over the continental United States (which is dominated by temperate and continental climates) found that, the majority of the long-term concentration trends in sediments (1992–2012), salinity (1982–2012) and nutrients (1982–2012) were attributed to changes in the concentration-flow relationship rather than long-term trends in streamflow7,40. Another study evaluated three large European basins representing alpine, Mediterranean and continental climate; although through a different approach (Mann–Kendall trend test combined with principal component analysis and correlation analyses), the study highlighted agricultural and population density as the most important drivers for the trends in phosphate over 1990–20159. Our findings confirm the dominant impact of non-streamflow driven changes on water quality trends with a large sample of temperate catchments. Moreover, we also expanded this finding to arid and subtropical climates, which are well represented in the three key regions we studied (i.e., Murray-Darling Basin, South East Coast VIC and North East Coast, see the individual catchments’ climate classification in Fig. S2a, Supplementary Information). One plausible reason for the lack of flow impact in driving water quality trends in our study is that almost all catchments analysed did not have significant monotonic trends in flow during our study period (Fig. S3, Supplementary Information).

Following the above finding that the change in concentration-flow relationships explains the majority of the significant water quality trends, we further explored whether the substantial regional differences in the significant water quality trends (Fig. 3) are linked to the long-term changes in land use/land cover of the catchments analysed within each major region, as these are important catchment changes that could be linked to changing concentration-flow relationships. Although different subsets of catchments were analysed for different water quality parameters, the comparison of changes in land use and land cover across the three regions generally follows similar patterns – so we present only the catchments analysed for TSS trends here as a representative example (Fig. 5), with Fig. S4 (Supplementary Information) showing the results for all five parameters. Common changes to the three regions include increases in percentage cover of natural land and intensively-used land (including urban and industrial uses), and decreases in percentage cover of production natural land (see Table S1 for a full definition of each category of land use and land cover). There is no statistically significant difference between the three regions (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05) in the change of the proportional catchment coverage of any major land use/land cover category, despite some visual differences across regions. This means that regional differences in water quality trends cannot be explained by regional differences in the changes to the catchment-averaged coverage of the main land use and land cover categories over time. For example, the Murray–Darling Basin, which showed the greatest water quality improvements compared to the other two regions, generally has greater or similar increases in the proportional catchment areas used for dryland agriculture and less or similar increases in the proportional catchment areas as natural/conservation land. These results suggest that other factors than catchment average land use and land cover changes may have contributed to the significant regional differences of water quality trends over the two decades shown in Fig. 3; the potential influencing factors are elaborated in the Discussion.

Each panel summarised catchment-level changes in a specific land use/land cover type, grouped by the three key regions with three boxes. The panel title denotes each major land use/land cover category analysed, along with the results of Kruskal-Wallis test (p-values) to identify statistically significant difference across the three regions in the long-term change of each land use/land cover category. The centre line and whiskers of each box indicate the median and 1.5 times the interquartile ranges of values. Table S1 (Supplementary Information) details the definition of individual land use and land cover categories and their corresponding data sources. The full summary of changes in the land use and land cover for catchments analysed for each water quality parameter is shown in Fig. S4, Supplementary Information.

How did water quality vary year-to-year?

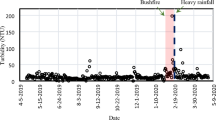

This section further explores how the flow-normalised concentrations of individual catchments vary from year to year over the two decades analysed. Due to the contrasting trends across regions shown previously, we investigated the temporal variation of trends separately for each of the three major regions analysed – South East Coast (Victoria), Murray–Darling Basin and North East Coast. Here, we present the variation of flow-normalised concentrations between consecutive years between 2000 and 2019; for each catchment, all these year-to-year variations are expressed as percentages of the corresponding flow-normalised concentration of 2000 (Fig. 6). These normalised inter-annual variations enable us to assess any non-linearity in the change of water quality over time for each region. Specifically, negative and positive values correspond to decreases and increases from one year to the next year, respectively, while the magnitudes of values over time indicate whether the increases and decreases are at stable rates.

Each row summarised one water quality parameter, with three key regions analysed in columns: South East Coast (VIC; left), Murray-Darling Basin (middle) and the North East Coast (right). Catchments for each region/parameter are grouped for each year over 2000–2019 and presented with a pair of boxes showing the significant/non-significant trends. All changes are expressed as percentages relative to the catchment-level flow-normalised concentration of year 2000. The x-axis marks the end years of all inter-annual variations. The centre line and whiskers of each box indicate the median and 1.5 times the interquartile ranges of values.

Within catchments with statistically significant trends over 2000–2019, the inter-annual variations in four of the five parameters, DO, EC, TN, and TP, are mostly within ±10% (as shown by the interquartile range) relative to the baseline concentration at year 2000, where the median inter-annual change within each region is largely within ±5% (Fig. 5).

Although there is clear between-catchment variation, the inter-annual variations follow somehow similar systematic patterns across the South East Coast (Victoria) and Murray–Darling Basin. Specifically, both regions experienced an initial decline in DO, following which the DO levels largely remained stable since 2012 for the South East Coast (Victoria), and switched to increasing trends around 2006 for the Murray-Darling Basin. The two regions also share common patterns in TSS and TP which both started decreasing since the second decade analysed. The most distinct pattern of non-linear change is for TSS in the Murray-Darling Basin, which has been relatively stable with minimal changes until around 2007, followed by a large-scale decline at an increasing rate between 2007 and 2012 and then a slower decline between 2012 and 2019. The potential causes of the distinct non-linear pattern of TSS for the Murray-Darling Basin are further explored in the Discussion.

For the North East Coast, TSS substantially fluctuates until 2010 followed by faster increase in each year after 2010. However, the low sample size (i.e., with only 5 catchments having significant trends) might limit the representativeness of a regional pattern. TP follows a rather steady increase from 2010 onwards.

Catchments with non-significant trends over 2000–2019 generally have similar patterns of inter-annual variation over the two decades compared to the catchments with significant trends. For example, the large-scale non-linear changes in DO and TSS discussed above are also seen in the non-significant catchments.

Discussion

This study presents the first national-scale water quality trend assessment across Australia to the best of our knowledge. The trends were estimated using the flow-normalised concentration, which removes the effect of the inter-annual variability in streamflow on water quality trends, allowing us to focus on the long-term underlying signals in water quality as opposed to noises40. This flow-normalisation process seems to have resulted in less significant trends in our study compared with earlier water quality trend studies. A previous water quality trend analysis for Victoria over 1995–2021 overlaps with our study period and also covers the South East Coast (VIC) region and parts of the Murray-Darling Basin12. The Victorian study used a linear trend model for each site and water quality parameter, accounting for flow, water temperature, and seasonality. The dominant trend types found in the early study are: non-significant trends for DO (48.1% of sites) and TP (46.5% of sites), increasing trends for TN (49.2% of sites), and decreasing trends for EC (45.9% of sites). Another study assessed the water quality trend over the recent 40 years along the River Murray since 197814, however, since the study only presented trends for five representative sites instead of any regional trend pattern, we focus on the Victorian trend study instead to compare the regional trend patterns suggested. Compared with the two relevant regions in our analyses (South East Coast (VIC) region and Murray-Darling Basin), findings of the Victorian trend study align with our results for DO and TP but contrast for EC – all of which are dominated by non-significant trends within the two regions (Fig. 1). The start of the analysis periods of the earlier trend study and the current study (1995 and 2000, respectively) are both within the Millennium Drought, with evident streamflow reductions in the Murray Darling Basin since the 1990s41. When estimating the EC trends with no flow normalisation, drought conditions at the start of the analysis period are expected to limit dilution and thus lead to higher EC levels23 compared to the latter two decades which have been recovering from drought. As such, without flow normalisation we are likely to see an overall decreasing trend in EC over the two decades of analysis – as was the case for the earlier Victorian trend study. In our study, in contrast, it is likely that flow normalisation has dampened the effects of the drought-induced reduction in dilution by removing the effect of inter-annual variability in streamflow, which is consistent with the more non-significant EC trends found in this study. Following this point, it should be noted that our study focuses on describing the long-term water quality trends over two decades, instead of understanding short-term variability of water quality in responses to the variability of hydro-climatic conditions; and the latter is also beyond the capacity of the WRTDS model by its design. Therefore, while short-term variability of streamflow, such as droughts and floods, are important drivers of water quality, with demonstrated links to severe water quality events17,24,42, our results do not intend to capture such short-term water quality responses. Furthermore, due to the focus on long-term trends and relative changes of water quality over time, our results should also not be interpreted as an assessment of the status of the ecological health, such as the occurrence of hypoxic events43.

Another study on 28 Murray River sites estimated water quality trends over both the 2003–2012 and 2012–2021 periods with a General linear model (GLM) that included a linear trend component13. The study concluded contrasting dominant trends across the sites analysed, for the two decades analysed: decreasing and increasing (2012–2021) for DO, increasing (2003–2012) and decreasing (2012–2021) for TP, while the sites analysed for EC lacked consistent trends for both decades. It is difficult to compare the overall trend directions between our study and the River Murray trend study since we analysed the trends over an entire 20-year period (2000–2019), while the River Murray trend study analysed two 10-year segments. However, we see similar patterns of shifting trend directions for DO and TP over the Murray-Darling Basin, with the year-to-year variation during our analyses period (Fig. 6).

Within the significant trends we identified over the two decades, the greatest contrast in the region-scale patterns of water quality trends is between two major river basins analysed, where the North East Coast – which largely flows into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon – has substantially higher increases in TP and TSS, while the Murray–Darling Basin has the greatest declines in EC, TP, and TSS. This shows an overall improving water quality condition for the Murray–Darling Basin and deteriorating condition for the North East Coast, over the two decades analysed. The South-East Coast (VIC) region shows more median-ranged trends. Here we focus on the two regions with the most extreme contrasting trends (i.e., North East Coast and Murray-Darling Basin) and discuss some potential drivers of the contrasting trends where further investigations are warranted.

Typically, long-term water quality trends arise from the combined effects of systematic changes in the streamflow and changes in the concentration-flow relationship. We demonstrated that in Australia, the majority of the estimated water quality trends are not due to long-term trends in streamflow (Fig. 4). Instead, the water quality trends are largely attributable to changes in catchment processes and conditions, due to factors such as land use/land cover changes, human activities and management interventions. As such, our study provides the first step towards supporting river and catchment management to identify key regions where water quality deterioration is likely due to external disturbance of catchments and waterways – which should be further investigated and prioritised for water quality management. We acknowledge that such external disturbances can be due to a wide range of driving factors, such as land use and land cover changes and management intervention, and we recommend further studies with specific regional focus to provide in-depth investigation on the potential factors driving water quality trends.

Given that the majority of water quality trends are attributed to changes in catchment processes and conditions, what might account for the significant differences in water quality trends across regions? We looked into the changes in catchment coverage by main land use and land cover categories across the two decades, and found that these changes did not differ significantly across the three regions. Furthermore, over the two decades, catchments in the Murray–Darling Basin are generally changing towards less natural/conservation and more agricultural land uses compared to the other two regions, despite that this region experienced the greatest improvement in water quality conditions. These results suggest that changes in catchment average land use and land cover alone have limited power in explaining the regional differences in the observed water quality trends. Other potential causes of the contrasting water quality trends across regions include regional land management practices (e.g., fertilisation and soil conservation strategies), water quality management interventions and/or changes in the source, mobilisation and transport processes at regional scales – some plausible drivers are discussed below.

Within the Murray–Darling Basin, most significant trends in EC (as a proxy for salinity) are decreases over 2000–2019, which is likely a result of the various salinity management schemes being in place since the late 1980s. This includes a combination of different intervention strategies such as improving irrigation efficiency, reducing drainage, installing salt interception, and drainage diversion schemes to divert saline groundwater away from entering the River Murray, the major river in the Basin. These salinity management schemes have been successful in lowering the salt levels in many locations along the Murray River26. In catchments within the North East Coast, there has been historically high land clearance rate at exceeding levels than other Australian states, especially in the past 50 years44. For example, within the North East Coast, the largest river basin, the Fitzroy Basin (156,000 km2), has had nearly 70% of its land being cleared for development during the 1960s to 1970s45. On the other hand, since the 1960s, there has also been a substantial increase in the application of nitrogen- and phosphorus-based fertiliser in the North East Coast region44. The intensive land use and agricultural practices in this region led to elevated concentrations of sediment and nutrient in streams which discharge into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Concerned by the detrimental effects of pollutants on the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem, the State and Federal governments have initiated large-scale programmes in the early 2000s to improve water quality, yet most programmes implemented have used voluntary approaches (e.g., via grants, education, extension) to improve land use and agricultural practices46. The overall deteriorating water quality we observed across the North East Coast catchments over 2000–2019 might be a delayed effect of the large land clearing and high fertiliser use that occurred prior to the implementation of water quality improvement programmes in the region45. Our results suggest that these new management interventions have likely not yet yielded tangible outcomes, highlighting the potentially long lag time between land management interventions and water quality responses. Such lag times are a common challenge when addressing water quality issues driven by diffuse pollutant sources at large spatial scales47,48. Alternatively, it is possible that the scale of adoption of these management practices may have been insufficient to yield noticeable improvements in water quality responses shown in the long-term trends. Our results also emphasise the need for detailed assessments and attribution of water quality trends in the North East Coast region, as well as the need of maintaining long-term monitoring networks to track the effectiveness of water quality management programmes into the future.

The overall decline in TSS in the Murray–Darling Basin demonstrates substantial non-monotonic changes over time, with most catchments in the region experiencing reduced TSS concentration at an accelerated rate between 2007 and 2012, which then slowed down between 2012 and 2019. What processes may be causing such regional-scale non-linear decreases in TSS, given that there has been no known region-scale sediment management programme in place? The first decade of the analysis period (2000–2009) in this region was dominated by the Millennium Drought41 which substantially affected catchments, with markedly low streamflow levels the Murray–Darling Basin; the drought broke when wetter conditions returned at the start of the second decade analysed via two successive La Niña events (2010–2012). However, except for the wetter conditions between 2010 and 2012, streamflow over the second decade analysed has not substantially increased compared to the first decade (Fig. S3, Supplementary Information). By focusing on the flow-normalised concentration, we have eliminated the effects of inter-annual flow variability on the water quality changes estimated in this study, thus, the systematic non-linear changes in TSS are likely not simply a result of the enhanced dilution during wet years between 2010 and 2012. The evident regional-scale non-linear changes in TSS pre- and post-2012 suggest potential shifts in the relationship between TSS and streamflow, which may be linked to drought-induced changes in catchment processes49. For example, there is some evidence in previous studies that catchments became less connected due to reduced streamflow during the drought, which may in turn led to reduced mobilisation of non-point sediments sources and increased sedimentation13,23,42,50,51, and shift in the dominant erosion pathways (e.g., from hillslope erosion to streambank erosion52,53). Linking to our results, the rapid decline of flow-normalised TSS between 2007 and 2012 may highlight the process of declining erosion pathways (such as via hillslope53) at the end of the prolonged drought around 2010, when dry conditions have persisted for nearly a decade. The declining rate of decreases in TSS after 2012 may be linked to the retrieval of some of these erosion pathways following the wetter years during 2010–2012, but the continuous decreases in TSS highlight that the drought impact on sediment transport processes might have (i) persisted longer beyond the actual drought, and/or (ii) depleted sediment sources to a large extent after the two wet years (2010–2012).

Conclusion

This study reveals the nation-wide patterns of trends in five key water quality parameters, DO, EC, TP, TN, and TSS, across Australia, for the first time. We analysed the nation’s long-term water quality trends in the flow-normalised concentration independent of the influence of inter-annual flow variations. As such, our results highlight large-scale patterns of water quality changes that are potentially due to non-stationary streamflow, as well as changes in catchment conditions, processes, and pollutant sources, and management interventions. The study not only provides a nation-wide summary of water quality trends, trajectories,s and region-specific trend patterns for the past two decades, but also highlights some potential causes of the contrasting water quality trends across key water resources regions. Our key findings are:

-

About half of Australia’s catchments have significant trends in each water quality parameter analysed, over the period of 2000–2019.

-

Within the catchments with significant trends across the nation, DO, EC, and TP generally have similar numbers of catchments showing increasing and decreasing trends; TN is dominated by increases (60% of catchments with significant trends) whereas TSS is dominated by decreases (86% of catchments with significant trends).

-

Most of the significant water quality trends are within ±8% per annum relative to year 2000, but there are substantial differences across regions.

-

Australia’s largest river system, the Murray–Darling Basin, has generally experienced an improvement in water quality conditions over the period of 2000–2019, with most significant trends as increases in DO, and decreases in EC, TP and TSS. In contrast, the North East Coast, which largely flows into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, is dominated by deteriorating conditions with most significant trends as increases in TP and TSS.

We found the contrasting water quality trends across regions cannot be explained by regional differences in the changes in catchment average land use and land cover conditions over the two decades. These results highlight the potential roles of other drivers for these trends, such as land and water management programmes and changes in catchment processes. Specifically, we discussed the potential role of the salinity management programmes in the Murray–Darling Basin in controlling river salinity over the two decades. The deteriorating condition of the North East Coast catchments might be the result of a lagged effect of the intensifying land-clearing and fertilisation since the 1960s. While both the state and federal governments have invested in improved management practices to reduce the pollutant loads being discharged into the Great Barrier Reef lagoon, these management interventions have not yet resulted in clear regional improvement on riverine water quality. Therefore, we recommend future studies to address more detailed trend assessment and attribution for this region, which will facilitate ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of water quality management programmes implemented in that region. We also highlight a large-scale non-linear change in TSS for the Murray-Darling Basin, which coincide with the Millennium Drought which affected the region in the 1990s and early 2000s. Based on this, we recommend further studies to assess potential impacts of that prolonged drought on catchment processes and explore their links with catchment erosion and sediment transport processes.

This work also highlights an overall geographical imbalance of catchment monitoring in Australia, which calls for monitoring initiatives in the underrepresented regions, even for non-perennial rivers, in order to better understand water quality trends, trajectories, and drivers. This will become increasingly important as we expect a greater proportion of Australia will show changes to streamflow characteristics, e.g. a shift from perennial rivers to non-perennial states under climate change17.

Methods

Data compilation and pre-processing

The water quality data analysed were extracted from a national water quality dataset complied at the end of 2019, by combining data requested from individual state government agencies (as detailed in our preceding study18). The national dataset includes a total of 578 water quality monitoring sites and seven water quality parameters. For each site and parameter, the record length varies between 4 and 47 years with 51–7623 pairs of concentration-flow data points. Together, there are a total of 14,912,771 samples in the data set.

Our trend analysis in this study focused on five water quality parameters that are of key interest for the management of Australian catchments and waterways, namely, electrical conductivity (EC), dissolved oxygen (DO), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP) and total suspended solid (TSS). Our study focused on the period between 2000 and 2019, which was based on a preliminary analysis that examined the number of sites retained when using different start and end dates of analysis with minimum record periods of above 10 years. We found the 2000–2019 period as the optimal period balancing the available record length at each site and the number of monitoring sites for trend analyses. For each of the five water quality parameters, we retained sites that passed the following criteria for minimum data availability:

-

1)

The data have maintained at least 10 years of record.

-

2)

The data have no major gap (exceeding 2 years) over either the start (2000) or end year (2019) of the trend analysis period.

-

3)

The longest data gap is less than 50% of the full record.

-

4)

If any data is below the detection limit, the total number of records below the detection limit is less than 50% of the total number of samples.

Consequently, 287 monitoring sites across the five water quality parameters were deemed suitable for trend analyses. Based on our preceding study which used a simplified Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification to assess the climate of the contributing catchment of each site18, the 287 sites analysed in this study span across the five major climate classes of Australia, namely, temperate (129 sites), subtropical (94 sites), arid (27 sites), tropical (22 sites), and Mediterranean (15 sites). The sites span eight of the 13 major river basins within Australia54, namely, the Murray-Darling Basin, North East Coast, South East Coast (VIC), South West Coast, South East Coast (NSW), Tasmania, Carpentaria Coast and Lake Eyre. The regions of individual river basins and climate zones may overlap meaning one river basin may cover areas within multiple climate zones, and vice versa (Fig. S2a, Supplementary Information).

For each monitoring site, flow data for the period between 2000 and 2019 were obtained from the streamflow simulations from the Australian Landscape Water Balance model (AWRA-L v7). This step was necessary because the raw monitored streamflow data consists of many gaps, while a continuous flow record is required for the statistical model used to estimating water quality trend (see subsequent section). AWRA-L v7 is the state-of-art rainfall-runoff model for Australia55, which runs on a 0.05° grid (approximately 5 km) and simulates Australia’s landscape water balance on a daily scale from 1911 till current. We extract the daily areal-average runoff over the contributing catchment area for each site, which was then multiplied by the catchment area as an approximate of the daily flow volume at the monitoring site (i.e., catchment outlet). The boundary of the upstream contributing catchment for each monitoring site was delineated using ArcMap based on the site coordinates, along with the Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s Geofabric dataset56 which details topography and streamlines across the nation.

Estimation of water quality trends

Trends were estimated of each water quality parameter for each monitoring site with the Weighted Regressions on Time, Discharge, and Season method (WRTDS33). WRTDS has been applied in studies of water quality trends, including regional and continental-scale studies for rivers across the United States7,35,36. WRTDS models water quality constituent concentration as combined effects of time, discharge and seasonality, i.e.:

For this study, for each day within the time series i, t is the time since the first record in year 2000 as decimal years, C is the concentration (for DO, TSS, TP, and TN) or the measured value (for EC), Q is the daily flow, β1 is the temporal effect, β2 is the flow effect, β3 and β4 are parameters of a sinusoidal function representing the seasonality effect, β0 is the intercept, and ε is the model residual. For each day within the record, a unique set of model coefficients is calibrated with a weighted regression, where all observations in the time series were used in the fitting with different weights that are determined by the difference in time, discharge, and season between each observation and the day of estimation. As such, the calibrated WRTDS model yields a time series of each model coefficient, which then allows the estimation of flow-normalised concentration for each day within the record period. This flow-normalisation process can effectively remove the influence of inter-annual variability in streamflow on concentration and thus identify long-term systematic changes in water quality as opposed to noises caused by inter-annual flow variability. It is noted that although water temperature has been shown to be a key predictor for DO3, we have not implemented water temperature as a predictor for DO, because the availability of water temperature data might be a further limitation to the number of sites with sufficient DO data for this analysis (which is already limited).

Before running the WRTDS model, further data pre-processing was performed for each time series analysed. For each monitoring site and parameter, we removed outliers which were defined as values further than plus and minus three standard deviations from the log mean value of the site and water quality parameter35. Further, long gaps (>2 years) within the trend analysis period (2000–2019) were first flagged for further assessments of the WRTDS model results after the model run.

The model was implemented to each time series (i.e., record of each site for each water quality parameter) using the R packages EGRET36 and EGRETci57 – the former enabled calibration of all model coefficients while the latter used a bootstrapping approach to estimate the confidence interval of each estimated trend. All the configurations in implementing EGRET and EGRETci were kept as the default values of the package, except for the minimum sample size required to run the model. The user manual of these packages suggested that a minimum of 100 samples (minNumObs = 100) should be used to achieve reliable trend estimation, and using less than about 50 samples can affect the reliability of the model58. Considering the general scarcity of water quality data in Australia, in this study WRTDS was first fit to catchments with a minimum number of 100 samples; if this minimum sample size was not met at any catchment, the threshold was adjusted to 50 and the model fitting was further assessed with diagnostic plots. The start of each year analysed was set to the start of hydrological year as July 1st (paStart = 7), as per defined in Australian Bureau of Meteorology59. For any site with water quality data gaps longer than two years, after model calibration the function blankTime (within the EGRET package) was run to exclude the results during the gap period so that the gap period is disregarded from trend estimation. Note that sites with any gap longer than two years have already been removed during the site screening by criterion 2) in Section Data complication and pre-processing.

It is noted that censored values are present in the water quality data analysed, which the WRTDS model is capable of handling. Specifically, when fitting the functional form of the model (Eq. 1), a weighted Tobit regression was used which accommodates censored data. The Tobit regression is widely recognised as a better alternative to the conventional weighted least squares regression approach in the presence of censored data57,60. Further to the use of Tobit regression, we also followed the default convention in WRTDS and specified that the calibration of the weighted regression model within WRTDS for each site analysed should be performed with a minimum of 50 uncensored data, thus ensuring the robustness of the fitted model in the presence of censored data36. An example R script to perform the abovementioned preliminary data filtering, quality control and run the WRTDS model is presented in Fig. S5, Supplementary Information.

Calculation of the overall water quality trends

To assess the overall trends of water quality between 2000 and 2019, we extracted the change in the annual flow-normalised concentrations between the two end years, 2000 and 2019 from WRTDS and categorised the trends with their significances and directions (i.e., increasing or decreasing). For each time series the bootstrapping approach implemented in EGRETci informed the 90% confidence interval of the estimated change, on which a two-sided p-value was estimated. A p-value lower than the critical value of 0.1 indicates rejection of the null hypothesis (i.e., there is no trend in the data), which thus identifies a significant trend over the period 2000–201935.

For each significant trend, the magnitude of trend was estimated from WRTDS outputs as:

estChange is the estimated change in flow-normalised concentration from the first year to the last year of the analysis period (i.e., 2000 to 2019). baseConc is the mean flow-normalised concentration for first year (i.e., 2000 for this study). Both estChange and baseConc are in mg L-1 for DO, TN, TP and TSS and in µg cm-1 for EC. As such, the Trend Magnitude estimated in Eq. 2 represents the percentage change in flow-normalised concentrations per year from 2000 to 2019, relative to the 2000 level. Due to the flow-normalised nature of the trends we estimated, our trend results are expected to be minimally affected by the hydrological conditions in the start and end year of the analysis. The overall trends for each water quality parameter were summarised across all catchments analysed for each water quality parameter.

Regional differences in water quality trends

To understand how water quality trends vary across different regions across Australia, we also summarised the trends within major river basins in Australia54. Regional patterns were synthesised on the direction, significance and magnitude of the trends for each water quality parameter. A nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to assess the differences in the distributions of water quality trend magnitudes across regions61.

The water quality trends within each region were further attributed by decomposing the trend for each catchment into two components, i.e., long-term changes in streamflow and long-term changes in the concentration-flow relationship. These two components were referred to as the streamflow trend component and the management trend component, respectively, following the convention in earlier studies7,37. The streamflow trend component quantifies the water quality changes due to systematic changes in the streamflow regime, whereas the management trend component estimates the water quality changes due to changes in the concentration-flow relationship, which can include a broad range of drivers such as human activities, management and land use changes. The management trend component was estimated using WRTDS with a stationary streamflow regime specified in the flow-normalisation process within the fitted WRTDS model. The streamflow trend component was then calculated by subtracting the management trend component from the overall flow-normalised trend (estChange). In other words, if the streamflow trend component was zero, the overall flow-normalised trend (estChange) would be fully attributed to the management trend component. The detailed methodology of trend decomposition between the two components is included in Choquette et al.37. The percentage of water quality trends as streamflow trend component were summarised by regions to conclude regional patterns on how much streamflow changes contributed to the water quality trends over the two decades. A Mann–Kendall test62 for monotonic flow trends for individual sites within each basin was performed to assist interpretation of the results on the streamflow trend component.

To further explain the variation of water quality trends across regions, we examined the changes in the percentage of individual catchments covered by each major land use and land cover category from 2000 to 2019 for each region. Nation-wide gridded land use categorisation data were obtained for years 2000 and 2016, as the latter was the latest year when data was available for63,64, from which the percentage area coverage of each catchment by each major land use category was estimated using catchment boundary delineated previously. The difference in the percentage coverage by each category was used to approximate the land use change over the two decades. The land cover change for each catchment was estimated following a similar approach, except that the source data used was the nation-wide grided land cover data for years 2000 and 201965. The key land use and land cover categories were extracted from the major categorisation of each dataset, which are listed and explained in Table S163,64,65. The changes in catchment average land use and land cover over the two decades were compared between regions.

Inter-annual changes in water quality

To understand the inter-annual variation of water quality within the analysis period, we extracted the annual flow-normalised concentration from the WRTDS model using function tableResult within the EGRET package. All the inter-annual changes were then summarised as percentage changes relative to the first year, 2000, for each site and parameter. These results were grouped by catchments with significant/non-significant trends over the full analysis period and compared between key regions analysed.

Data availability

Water quality data used in this study was compiled in our preceding study which detailed the collation process18. These data were obtained from public domain resources. for this study are obtained from public domain resources. They include the following: WaterNSW – Water Insights (https://waterinsights.waternsw.com.au/); Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action Victoria – Water Measurement Information System (https://data.water.vic.gov.au/WMIS); Department for Environment and Water South Australia - Water Data SA; Queensland Government – Water Monitoring Information Portal (https://water-monitoring.information.qld.gov.au/); Department of Water and Environmental Regulation Western Australia – Water Information Reporting (http://wir.water.wa.gov.au/); Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania – Water Information Tasmania Web Portal (https://portal.wrt.tas.gov.au/Data); Northern Territory Government – Water Data Portal (https://water.nt.gov.au/Data).

Code availability

The R Script for data cleaning, site screening and fitting the WRTDS model, following the approach detailed in Methods, can be found in Figure S5, Supplementary Information.

Change history

02 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02148-w

References

Guo, D. et al. Key factors affecting temporal variability in stream water quality. Water Resour. Res. 55, 112–129 (2019).

Zhang, Q. & Ball, W. P. Improving riverine constituent concentration and flux estimation by accounting for antecedent discharge conditions. J. Hydrol. 547, 387–402 (2017).

Zhi, W., Ouyang, W., Shen, C. & Li, L. Temperature outweighs light and flow as the predominant driver of dissolved oxygen in US rivers. Nat. Water 1, 249–260 (2023).

Ouyang, W., Hao, F., Skidmore, A. K. & Toxopeus, A. G. Soil erosion and sediment yield and their relationships with vegetation cover in upper stream of the Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 396–403 (2010).

Smith, H. G., Sheridan, G. J., Lane, P. N. J., Nyman, P. & Haydon, S. Wildfire effects on water quality in forest catchments: a review with implications for water supply. J. Hydrol. 396, 170–192 (2011).

Smith, A. P., Western, A. W. & Hannah, M. C. Linking water quality trends with land use intensification in dairy farming catchments. J. Hydrol. 476, 1–12 (2013).

Murphy, J. & Sprague, L. Water-quality trends in US rivers: exploring effects from streamflow trends and changes in watershed management. Sci. Total Environ. 656, 645–658 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Chesapeake Bay’s water quality condition has been recovering: insights from a multimetric indicator assessment of thirty years of tidal monitoring data. Sci. Total Environ. 637-638, 1617–1625 (2018).

Diamantini, E. et al. Driver detection of water quality trends in three large European river basins. Sci. Total Environ. 612, 49–62 (2018).

Julian, J. P., de Beurs, K. M., Owsley, B., Davies-Colley, R. J. & Ausseil, A. G. E. River water quality changes in New Zealand over 26 years: response to land use intensity. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 1149–1171 (2017).

Luo, P. et al. Spatiotemporal trend analysis of recent river water quality conditions in Japan. J. Environ. Monit. 13, 2819–2829 (2011).

Guo, D. et al. Victorian Water Quality Analysis 2022. Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action - State Government of Victoria. https://www.water.vic.gov.au/our-programs/water-monitoring-and-reporting/water-quality-trends (2023).

Silvester, E. et al. River Murray Water Quality Monitoring Program (RMWQMP) Data Trends Analysis 2021, CFE Publication No. 276. https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/river-murray-water-quality-data-trends-analysis-2022.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2024] (2022).

Biswas, T. K. & Mosley, L. M. From mountain ranges to sweeping plains, in droughts and flooding rains; river Murray water quality over the last four decades. Water Resour. Manag. 33, 1087–1101 (2019).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1633–1644 (2007).

Wasko, C. & Guo, D. Understanding event runoff coefficient variability across Australia using the hydroEvents R package. Hydrol. Process. 36, e14563 (2022).

Shanafield, M. et al. Australian non-perennial rivers: Global lessons and research opportunities. J. Hydrol. 634, 130939 (2024).

Lintern, A. et al. The influence of climate on water chemistry states and dynamics in rivers across Australia. Hydrol. Process. 35, e14423 (2021).

Guo, D. et al. Synthesizing the impacts of baseflow contribution on concentration–discharge (C–Q) relationships across Australia using a Bayesian hierarchical model. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 1–16 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Controls on spatial variability in mean concentrations and export patterns of river chemistry across the Australian Continent. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2022WR032365 (2022).

Green, J. & Moggridge, B. Australia state of the environment 2021: inland water, independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 10.26194/0P6K-MS94. https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-07/soe2021-inland-water.pdf. [Accessed 05 May 2024] (2021).

Lawrence, J. et al. Australasia. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds.H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría et al.). Cambridge University Press. 1581–1688, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.013 (2022).

Mosley, L. M. Drought impacts on the water quality of freshwater systems; review and integration. Earth-Sci. Rev. 140, 203–214 (2015).

Murphy, S. F., McCleskey, R. B., Martin, D. A., Writer, J. H. & Ebel, B. A. Fire, flood, and drought: extreme climate events alter flow paths and stream chemistry. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci.123, 2513–2526 (2018).

Brodie, J. & Pearson, R. G. Ecosystem health of the Great Barrier Reef: time for effective management action based on evidence. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 183, 438–451 (2016).

Hart, B., Walker, G., Katupitiya, A. & Doolan, J. Salinity Management in the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia. Water 12, 1829 (2020).

Dupas, R., Minaudo, C., Gruau, G., Ruiz, L. & Gascuel-Odoux, C. Multidecadal trajectory of riverine nitrogen and phosphorus dynamics in rural catchments. Water Resour. Res. 54, 5327–5340 (2018).

Huntington, T. G. & Shanley, J. B. A systematic increase in the slope of the concentration discharge relation for dissolved organic carbon in a forested catchment in Vermont, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 844, 156954 (2022).

Minaudo, C. et al. Seasonal and event-based concentration-discharge relationships to identify catchment controls on nutrient export regimes. Adv. Water Resour. 131, 103379 (2019).

He, Z., Yao, J., Lu, Y. & Guo, D. Detecting and explaining long-term changes in river water quality in south-eastern Australia. Hydrol. Process. 36, e14741 (2022).

Knapp, J. L. A., von Freyberg, J., Studer, B., Kiewiet, L. & Kirchner, J. W. Concentration–discharge relationships vary among hydrological events, reflecting differences in event characteristics. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 2561–2576 (2020).

Sattari, M. T., Mirabbasi, R., Jarhan, S., Shaker Sureh, F. & Ahmad, S. Trend and abrupt change analysis in water quality of Urmia Lake in comparison with changes in lake water level. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192, 623 (2020).

Hirsch, R. M., Moyer, D. L. & Archfield, S. A. Weighted Regressions on Time, Discharge, and Season (WRTDS), with an Application to Chesapeake Bay River Inputs. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 46, 857–880 (2010).

Zhang, Q., Harman, C. J. & Ball, W. P. An improved method for interpretation of riverine concentration-discharge relationships indicates long-term shifts in reservoir sediment trapping. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10,215–210,224 (2016).

Oelsner, G. P. et al. Water-quality trends in the nation’s rivers and streams, 1972–2012—Data preparation, statistical methods, and trend results [Report] (2017-5006). (Scientific Investigations Report, Issue. U. S. G. Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/sir20175006 (2017).

Hirsch, R., De Cicco, L., Watkins, D., Carr, L. & Murphy, J., EGRET: exploration and Graphics for RivEr Trends, version 3.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=EGRET (2018a).

Choquette, A. F., Hirsch, R. M., Murphy, J. C., Johnson, L. T. & Confesor, R. B. Jr. Tracking changes in nutrient delivery to western Lake Erie: approaches to compensate for variability and trends in streamflow. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 45, 21–39 (2019).

Eccles, R., Zhang, H., Hamilton, D. & Maxwell, P. Trends in water quality in a subtropical Australian river-estuary system: responses to damming, climate variability and wastewater discharges. J. Environ. Manag. 269, 110796 (2020).

Liu, S., Guo, D., Webb, J. A., Wilson, P. J. & Western, A. W. A simulation-based approach to assess the power of trend detection in high- and low-frequency water quality records. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192, 628 (2020).

Murphy, J. C. Changing suspended sediment in United States rivers and streams: linking sediment trends to changes in land use/cover, hydrology and climate. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 991–1010 (2020).

Bureau of Meteorology. Trends and historical conditions in the Murray-Darling Basin: A report prepared for the Murray-Darling Basin Authority by the Bureau of Meteorology. https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/bp-eval-2020-bom-trends-and-historical-conditions-report.pdf [Accessed 28 Oct 2024] (2020).

Mosley, L. M. et al. The impact of extreme low flows on the water quality of the lower Murray River and Lakes (South Australia). Water Resour. Manag. 26, 3923–3946 (2012).

Whitworth, K. L., Baldwin, D. S. & Kerr, J. L. Drought, floods and water quality: Drivers of a severe hypoxic blackwater event in a major river system (the southern Murray–Darling Basin, Australia). J. Hydrol. 450-451, 190–198 (2012).

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Population and major land use in the Great Barrier Reef catchment area spatial and temporal trends. ISBN 1 876945 10 9. https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/bitstream/11017/385/1/Population-and-major-land-use-in-the-Great-Barrier-Reef-catchment-area-spatial-and-temporal-trends.pdf [Accessed 08 June 2024] (2001).

Yu, B., Joo, M. & Caroll, C. Land use and water quality trends of the Fitzroy River, Australia. Understanding Freshwater Quality Problems in a Changing World Conference Proceedings of H04, IAHS-IAPSO-IASPEI Assembly, Gothenburg, Sweden, July 2013 (IAHS Publ. 361, 2013). https://iahs.info/uploads/dms/15601.44-313-320-361-39-H04_YU_Water-quality-trends---Fitzroy-for-IAHS-20-Feb-2013-proof-readCORR.pdf (2013).

Taylor, B. M. & Eberhard, R. Practice change, participation and policy settings: a review of social and institutional conditions influencing water quality outcomes in the Great Barrier Reef. Ocean Coast. Manag. 190, 105156 (2020).

Creighton, C., Waterhouse, J., Day, J. C. & Brodie, J. Criteria for effective regional scale catchment to reef management: a case study of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 173, 112882 (2021).

Lintern, A., McPhillips, L., Winfrey, B., Duncan, J. & Grady, C. Best management practices for diffuse nutrient pollution: wicked problems across urban and agricultural watersheds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 9159–9174 (2020).

Peterson, T. J., Saft, M., Peel, M. C. & John, A. Watersheds may not recover from drought. Science 372, 745–749 (2021).

Caruso, B. S. Temporal and spatial patterns of extreme low flows and effects on stream ecosystems in Otago, New Zealand. J. Hydrol. 257, 115–133 (2002).

Guo, D. et al. A data-based predictive model for spatiotemporal variability in stream water quality. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 827–847 (2020).

Stackpoole, S. M. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of dissolved organic matter quantity and quality in the Mississippi River Basin, 1997–2013. Hydrol. Process. 31, 902–915 (2017).

Vigiak, O. et al. Detecting changes in sediment sources in drought periods: the Latrobe River case study. Environ. Model. Softw. 85, 42–55 (2016).

Bureau of Meteorology. Topographic Drainage Divisions and River Regions. https://www.bom.gov.au/water/about/riverBasinAuxNav.shtml Accessed 01/08/2023 (2012).

Frost, A. J. & Shokri, A. The Australian Landscape Water Balance model (AWRA-L v7). Technical Description of the Australian Water Resources Assessment Landscape model version 7. Bureau of Meteorology Technical Report. https://awo.bom.gov.au/assets/notes/publications/AWRA-Lv7_Model_Description_Report.pdf [Accessed 01 May 2023] (2021).

Bureau of Meteorology, Geofabric V2 [WWW Document]. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.bom.gov.au/anon/home/geofabric/ [Accessed 21 June 2016] (2012).

Hirsch, R. M., Archfield, S. A., De Cicco, L. A., A bootstrap method for estimating uncertainty of water quality trends, Environmental Modelling & Software, 73, 148–166 (2015).

Hirsch, R. M. & De Cicco, L. A. User guide to Exploration and Graphics for RivEr Trends (EGRET) and dataRetrieval—R packages for hydrologic data (version 2.0, February 2015): U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods book 4, chap. A10, 93 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/tm4A10 (2015).

Bureau of Meteorology Water Year. in: Australian Water Information Dictionary. https://www.bom.gov.au/water/awid/id-644.shtml#:~:text=1%20July%20to%2030%20June,Water%20status%3A%20Water%20Market%20Reports. [Accessed 01 Aug 2023] (2024).

Helsel, D. R., Hirsch, R. M., Ryberg, K. R., Archfield, S. A. & Gilroy, E. J., Statistical methods in water resources: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods, book 4, chap. A3, 458 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/tm4a310.3133/tm4a3. [Supersedes USGS Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, book 4, chap. A3, version 1.1.] (2020).

Kruskal, W. H. & Wallis, W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 47, 583–621 (1952).

Hipel, K. W. and McLeod, A. I. Time Series Modelling of Water Resources and Environmental Systems. New York: Elsevier Science (1994).

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences. Land Use of Australia, Version 3 – 2001/2002 data.gov.au. https://data.gov.au/dataset/5e08b738-bde9-44a4-aaa4-12af5a536a01 (2023).

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences Land use of Australia 2010–11 to 2015–16, 250 m, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra, September, CC BY 4.0. https://doi.org/10.25814/7ygw-4d64 (2022).

Tissott, B., Mueller, N. DEA Land Cover 25m. Geoscience Australia, Canberra. https://doi.org/10.26186/146090 [Accessed 23 April 2024] (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G., A.L., and C.D. conceived the idea. D.G., A.L., C.D., S.L., C.M., R.D. and K.Z. carried out the data retrieval. AL carried out preliminary analyses. D.G. carried out model development and validation. Q.Z. helped with the technical issues related to model simulations. D.G. developed the first draft, upon which A.L., C.M., R.D., C.D., S.L., Q.Z., K.Z., and U.B.M. iterated multiple versions for figure design, content structure and key message development. D.G. finalised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, D., Zhang, Q., Minaudo, C. et al. Australian water quality trends over two decades show deterioration in the Great Barrier Reef region and recovery in the Murray-Darling Basin. Commun Earth Environ 6, 67 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02044-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02044-3

This article is cited by

-

Phosphorus mining and bioavailability for plant acquisition: environmental sustainability perspectives

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)