Abstract

In recent decades, relative humidity over land has declined, driving increases in droughts and wildfires. Previous explanations attribute this trend to insufficient moisture advection from the ocean to sustain the current level, but this ignores atmospheric moisture supplied from terrestrial evapotranspiration. Importantly, current state-of-the-art climate models continue to underestimate the observed relative humidity trend over land. Here, we show that changes in specific humidity over land relative to a given baseline, unaccounted for by ocean advection, are quantitatively equivalent to relative changes in evapotranspiration on a global scale. This finding is consistent across climate models and climate reanalysis datasets, despite discrepancies in evapotranspiration trends among them. Differences in evapotranspiration trends are identified as a prominent cause of the bias in relative humidity trend expressed in climate models. These results suggest that current climate models may overestimate evapotranspiration intensifications, leading to an underestimation of atmospheric drying, with critical implications for accurately predicting droughts, wildfires, and climate adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human-induced climate change is expected to have substantial impacts on Earth’s water cycle1. Reliable predictions of future water resources require a comprehensive understanding of how climate change affects land evapotranspiration (ET)2,3,4, which represents the sum of evaporation from soil, intercepted water, and plant transpiration. While many studies have investigated the effects of climate change on actual ET, the complex interactions between the atmosphere, land surface, soil moisture, and vegetation make it challenging to accurately predict changes in ET.

The complexity of discerning the influence of anthropogenic climate change on ET is further complicated by the reciprocal relationship between ET and the atmospheric state. Atmospheric conditions not only serve as drivers of ET but also are influenced by ET, given that ET acts as a major pathway for moisture from land to the air, particularly in inland regions5,6,7,8,9,10. Consequently, the uncertainty in ET predictions has been identified as a key contributor to uncertainty in atmospheric state predictions11,12. Paradoxically, however, the impacts of ET on the near-surface atmosphere are frequently overlooked under the prevailing assumption that the atmospheric state acts primarily as a demand-side driver of ET13.

Near-surface atmospheric observations in recent decades demonstrate an emergent decline in relative humidity over land (RHL)14,15. This decline in observed RHL is commonly explained using an ocean advection theory16,17,18. This theory suggests that specific humidity over land (i.e., water vapor content of the near-surface atmosphere) does not increase rapidly enough to maintain RHL under global warming because of insufficient increases in moisture advection from the ocean to the land. Consequently, warmer and drier atmospheric conditions over land are widely considered to drive a rapid increase in the atmospheric evaporative demand that could intensify ET19. However, this perspective ignores the reciprocal influences of ET and the atmospheric state20,21,22. For example, recent studies suggest that soil moisture constrains moisture supplied to the air through ET, making it crucial to represent soil moisture in relation to changes in RHL over land in climate simulations23,24. Particularly, Zhou, et al.24 demonstrated that RHL decreases even in the absence of the changes in ocean advection, as soil moisture naturally decreases under global warming, leading to a decline in RHL.

Therefore, it is essential to theoretically harmonize the influences on the atmospheric moisture budget over land resulting from (i) advected moisture from the ocean and (ii) moisture supplied via ET. This is particularly important as recent studies suggest that state-of-the-art climate models currently underestimate the observed RHL decline trend25,26,27. However, the fundamental reason for this bias remains unclear28. More importantly, this RHL bias in climate models implies an underestimation of future drying and warming trends in model projections29. Therefore, a nuanced understanding of the influences of ET on near-surface humidity trends over land is essential for accurately projecting future atmospheric conditions, water availability, and impacts of anthropogenic climate change on future droughts and wildfires.

Here, we aim to investigate the influence of terrestrial ET on the declining trend in RHL. To this end, we first reevaluate the ocean advection theory by using the ERA530 and JRA-3Q31 reanalysis datasets, and 27 general circulation models (GCMs) contained in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6)32. We then propose an alternative explanation, based on an empirical analysis of the data, that considers both ocean advection and ET in a parsimonious way. By partitioning the decline in RHL to these two factors, we examine the underlying causes for the discrepancies in RHL decline between climate models and reanalysis datasets.

Results

Ocean advection theory

We begin by considering the ocean advection theory, which hypothesizes that horizontal advection from the ocean is the primary source of water vapor over land16,17. Byrne and O’Gorman17 proposed a parsimonious steady-state moisture budget for an atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) box over land (Supplementary Fig. 1) to derive a simple moisture constraint assuming negligible ET, as expressed by Eq. 1:

where δ indicates the temporal change in specific humidity (q) over land (qL) and ocean (qO) between two periods. The derivation of Eq. 1 involved assumptions of constant values for the ratio between horizontal and vertical mixing velocities, ABL heights, and the specific humidity jump rate at the top of the ABL (detailed in “Methods” section).

It should be noted that Eq. 1 was derived not only by Byrne and O’Gorman17 but also by Chadwick, et al.16 based on the Lagrangian path-integral. Two independent derivations further support the robust theoretical concept despite the simplicity of the resulting equation. It should also be noted that a subsequent study by Byrne and O’Gorman18 combined Eq. 1 with additional constraints, such as the assumption of identical changes in moist static energy over land and ocean and constant relative humidity over ocean. In this study, however, we focus solely on Eq. 1 to avoid uncertainty potentially introduced by additional constraints.

Since qL is smaller than qO at a global scale, Eq. 1 implies that \(\delta {q}_{L} < \delta {q}_{O}\), leading to a decline in RHL under global warming. By partitioning δqL into relative humidity and temperature components and rearranging for δRHL, we can write as follows.

where \({{RH}}_{L}(=\frac{{q}_{L}}{{q}^{* }\left({T}_{L}\right)})\) is the near-surface relative humidity over land, \({q}^{* }\left({T}_{L}\right)\) is saturation specific humidity at the near-surface air temperature \(({T}_{L}),\alpha (=\frac{{L}_{v}}{{R}_{v}{{T}_{L}}^{2}})\) is the sensitivity of saturation specific humidity to temperature. Here, Lv is latent heat of vaporization and Rv is the gas constant for water vapor. In this derivation, we approximate relative humidity using specific humidity instead of water vapor pressure and linearize the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship.

We first test the ocean advection theory summarized in Eq. 2 by using two latest-generation reanalysis datasets. We focus on non-Polar regions located 66.5°S to 66.5°N in order to exclude the Artic and Antarctica since the ocean advection theory is better justified at lower latitudes18. Our analysis revealed that Eq. 2 closely captures RHL trends in ERA5 reanalysis (Fig. 1a). Although there is a relatively large bias in RHL for JRA3Q compared to ERA5, Eq. 2 still reasonably represents RHL trends in JRA-3Q considering the overlapped confidence intervals of the trends (Fig. 1b). Since reanalysis RHL trends closely match observed RHL trends26,27, our results suggest the robustness of the ocean advection theory in reproducing and understanding observed RHL trends on a global scale, consistent with previous studies18.

Comparison of (a-c) ocean advection theory vs. (d-f) proposed advection & ET scaling using ERA5 (a, d), JRA-3Q (b, e), and CMIP6 (c, f) datasets. The black lines represent direct output from reanalysis or climate model. The blue lines in (a–c) represent the ocean advection theory (Eq. 2), while the orange lines in (d–f) represent the proposed scaling (Eq. 4). The right panels show RHL trends per decade for each dataset and the theoretical predictions, with error bars for reanalysis (95% confidence intervals of linear regression) and box plots for CMIP6 (median, interquartile range, and full data spread). In (c) and (f), shaded areas indicate the range of all tested climate models, while the solid line indicates the ensemble mean. Here, Artic (>66.5°N) and Antarctic regions (<66.5°S) are masked.

However, the ocean advection theory fails to accurately reproduce RHL trends in climate simulations (Fig. 1c). We found that declining trends in RHL for CMIP6 are noticeably smaller than the theory expected. While the ocean advection theory’s expected RHL trend is consistent across reanalysis and CMIP6, the actual trends in RHL in CMIP6 are smaller than those in reanalysis datasets (Fig. 1a-c). Furthermore, we applied the ocean advection theory to the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (AMIP6) models, which prescribe sea surface temperatures (SST). We found that the ocean advection theory is still biased relative to the models even with SST-prescribed AMIP6 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). This result suggests that additional factors influencing RHL trends in climate simulations might not be adequately captured by the ocean advection theory alone. This discrepancy highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach, such as incorporating ET, to understand the fundamental differences between climate simulations and reanalysis.

Incorporating ET into the ocean advection theory

Originally, Byrne and O’Gorman17 considered both moisture advection from the ocean and terrestrial ET as sources of water vapor in their parsimonious ABL box model. They tested scenarios with negligible ET and with ET included, using idealized GCM simulations and regression approaches. They found that water vapor advection from the ocean plays a primary role in changes in specific humidity over land, while changes in both ocean advection and ET considerably contribute to the decline in RHL. This finding aligns with other studies that additionally highlight the substantial role of changes in soil moisture as a control in RHL trends23,24. We note that ET represents the flux by which changes in soil moisture impact trends in RHL.

Nevertheless, subsequent studies on this topic have primarily focused on the ocean advection theory18,33,34, often acknowledging the limitations of neglecting ET. This focus is partly due to the simplicity of the ocean advection theory, as there has been no comparable simple scaling that includes ET, given the added complexity that it introduces into the moisture budget equation. To overcome this limitation, we propose to extend the simple ocean advection scaling to include ET in a parsimonious way. We hypothesize that changes in specific humidity, which are not explained by Eq. 1, should be related to ET. Specifically, we empirically found that the difference between relative changes in specific humidity over land and over the ocean is equivalent to relative changes in ET:

We tested Eq. 3 based on interannual variability of ET and specific humidities and found it to be reasonably accurate across the tested models on a global scale (Fig. 2). The median correlation coefficient between \(\frac{\delta {ET}}{{ET}}\;{{\rm{and}}}\;\frac{\delta {q}_{L}}{{q}_{L}}-\frac{\delta {q}_{O}}{{q}_{O}}\) was about 0.8, although it is not accurate in some models, including the JRA-3Q reanalysis.

a Scatter plot showing the relationship between \(\frac{\Delta {ET}}{{ET}}{{\rm{and}}}\frac{\Delta {q}_{L}}{{q}_{L}}-\frac{\Delta {q}_{O}}{{q}_{O}}\) across different models and reanalysis datasets. Here, Δ denotes interannual variability (i.e., anomaly). The blue line represents fits across CMIP6 models and reanalysis products using the proposed scaling, and the dashed line indicates a one-on-one line. b Correlation coefficients between \(\frac{\Delta {ET}}{{ET}}{{\rm{and}}}\frac{\Delta {q}_{L}}{{q}_{L}}-\frac{\Delta {q}_{O}}{{q}_{O}}\) for each model and reanalysis datasets. The dotted line represents the median correlation coefficient across CMIP6 models and reanalysis dataset. The points are color-coded for both panels representing reanalysis and CMIP6. The Arctic (>66.5°N) and Antarctic (<66.5°S) regions are masked.

While we do not have a concrete explanation for the empirical success of Eq. 3, we can speculate using the steady-state moisture budget used in Byrne and O’Gorman17, as detailed in the Methods section. We found that deriving Eq. 3 from this budget requires the relative increase in qO to be offset by a relative decrease in horizontal mixing velocity (v in Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, if the horizontal mixing timescale \({\tau }_{1}=\frac{l}{v}\) (where l is the length of the land from the ocean) is much longer than the vertical mixing timescale \({\tau }_{2}=\frac{{h}_{L}}{w}\) (where hL is the boundary layer height over land and w is the vertical mixing velocity), then Eq. 3 can be derived directly from the moisture budget equation.

Under global warming, qO increases at a rate of ~6–7% K−1, following the Clausius-Clapeyron relation35,36,37. In contrast, large-scale atmospheric circulation tends to slow down, reducing v at a rate of about 3–5% K−1 37,38,39. As a result, the relative increase in qO is largely canceled out by a relative decrease in v. Also, the second condition \(({\tau }_{1}\gg {\tau }_{2})\) is reasonable on a global scale, which helps explain why the proposed Eq. 3 holds approximately across reanalysis datasets and CMIP6 models. It should be noted, however, that we have not explicitly demonstrated that the relative decrease in v is precisely balanced by the relative increase in qO. The first assumption is speculative and requires further investigation, but it suggests that a plausible physical foundation for Eq. 3 may exist.

Similar to the derivation of Eq. 2, we rearrange Eq. 3 for RHL by partitioning qL into relative humidity and temperature components as follows:

This proposed scaling is comparable with Eq. 2, with the last term of Eq. 4 being the only difference between the two. In the remainder of this paper, we will refer to Eq. 4 as the “ocean advection & ET scaling” which explains relative humidity changes over land.

In Fig. 1d-f, we test our ocean advection & ET scaling against ocean advection theory on its own (Fig. 1a-c) using the same datasets. The results show that the proposed scaling accurately captures the RHL trends across different datasets. Specifically, estimated RHL trends estimated for reanalysis products using Eq. 4 become even closer to the direct reanalysis output of RHL. For GCMs, this improvement is more apparent for both CMIP6 and AMIP6 models, as Eq. 2 failed to capture the RHL trend, while Eq. 4 well approximates the RHL trends (Fig. 1f for CMIP6 and Supplementary Fig. 2b for AMIP6). Furthermore, interannual variability of RHL in ERA5 and CMIP6 were well matched with Eq. 4. These results suggest that the proposed ocean advection & ET scaling is better suited than the ocean advection theory for constraining relative humidity trends over land by explicitly considering ET as a source of water vapor.

An attribution analysis of changes in RH L

To better understand the reasons underlying the differences in RHL trends between reanalysis products and CMIP6 models, we attribute the RHL trend based on the proposed ocean advection & ET scaling. Specifically, sum of the first two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 4 is denoted as “Adv,” while the last term is denoted as “ET” in Fig. 3.

The bars represent the contributions of different factors to the RHL trends: the ocean advection theory (Adv), terrestrial ET (ET), and the combined ocean advection & ET scaling (Adv&ET). The black bars on the right side of each panel represent the RHL trends from reanalysis or CMIP6 models. Panels show results for (a) ERA5, (b) JRA3Q, (c) CMIP6. The Arctic (>66.5°N) and Antarctica (<66.5°S) are masked.

For the two reanalysis datasets, the ET contribution is of secondary importance in magnitude (Fig. 3a, b). Changes in ET contribute to a decrease in RHL in ERA5 but contribute to an increase in RHL in JRA-3Q. However, this contribution is small relative to the effects of ocean advection theory. On the other hand, for CMIP6 models, the ET contribution plays a substantial role (Fig. 3c). An increase in ET largely cancels out the effects of ocean advection theory, resulting in a smaller decline in RHL for CMIP6 models compared to reanalysis. This indicates that the differences in RHL trends between reanalysis and CMIP6 models can be largely attributed to the varying influence of ET.

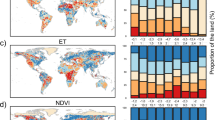

Indeed, we found differences in global ET trends between the reanalysis and CMIP6 models (Fig. 4). The reanalysis datasets, ERA5 and JRA-3Q, show relatively low ET intensifications compared to the CMIP6 models. Most CMIP6 models exhibit higher ET trends than reanalysis, with a median trend of about 0.35 mm year−2. This discrepancy suggests that CMIP6 models may overestimate ET trends compared to reanalysis, contributing to the bias in RHL trends in climate simulations.

Discussion

In this study, we present simple empirical scaling to better understand the coupled behavior between humidity over land, ocean advection, and terrestrial ET. We employed this approach to evaluate trends in atmospheric humidity and ET over past decades on a global scale. One of the key findings is that the difference in RHL trends between reanalysis data and climate models can largely be attributed to the divergence in ET trends between the two.

These results are consistent with recent studies investigating RHL trend in climate models. For example, Simpson et al.27 showed that discrepancies in δRHL between observations and CMIP6 models are substantial, particularly in arid regions such as the Southwestern US. While they discussed several hypothetical mechanisms to explain this discrepancy, they cautiously suggest that water vapor supplied by ET, rather than ocean advection, plays a critical role, based on various lines of evidence in their analysis. Jacobson et al.40 further investigated the observed humidity trends over Southwestern US and concluded that a decline in ET, driven by reduced spring precipitation, is a major contributor to the drying of atmospheric humidity. In another recent study, Douville and Willett29 identified certain plausible climate models within CMIP6 that exhibit a drier δRHL based on observed constraints and Bayesian statistics. Notably, these plausible models generally show a weaker increase in ET compared to the CMIP6 ensemble mean, implying ET intensification may be overestimated in most other CMIP6 models. These findings are consistent with our analysis, as our results suggest that the RHL bias in CMIP6 may be due to an overestimation of ET intensification compared to reanalysis.

It should be noted that ET trends in ERA5 and JRA-3Q are not equivalent to direct observations, as they are also generated using land surface models. Importantly, and in contrast to near-surface temperature and humidity, which incorporate in situ measurements, there are limited long-term ET observations available. This forces the reanalysis datasets to rely heavily on model-based predictions for ET. Nevertheless, if both reanalysis and GCMs maintain physical consistency between land surface fluxes and the atmospheric state41, then models that closely align with observed atmospheric conditions should produce more accurate land surface fluxes. The proposed simple scaling highlights the internal consistency of these models, supporting greater confidence in reanalysis ET trends, despite their reliance on model predictions.

If ET intensification is indeed overestimated in state-of-the-art GCMs, what could this mean for soil moisture trends? Since ET depletes water from the soil, an overestimated ET increase in GCMs might suggest an overestimated reduction in soil moisture. On the other hand, if soil moisture reduction serves as the main constraint to increasing ET, then the overestimated ET in GCMs could stem from an underestimated reduction in soil moisture. Although our analysis doesn’t directly answer this question, recent studies exploring the role of soil moisture in declining RHL support the latter view23,24,40. These studies suggest that as soil moisture decreases under global warming, it contributes to reduced RHL. While these previous studies have directly linked soil moisture and RHL, our study bridges this gap by examining the role of ET in RHL decline. Thus, while further research is needed, our framework aligns more with the second idea that soil moisture, as sources of atmospheric water vapor, plays a crucial role in this dynamic.

While our empirical scaling aligns consistently with reanalysis and climate models, certain limitations in our methodology should be acknowledged. Firstly, the model relies on several simplified assumptions which may not be plausible at certain spatiotemporal scales. For example, there is no obvious reason to expect an exact balance between relative changes in qO and v, as implicitly assumed by our proposed scaling. Also, our proposed equations may not be applicable at regional scales. Furthermore, while Eq. 3 generally agrees well across tested models at a global scale, its performance was relatively low in explaining the interannual variability of ET in JRA-3Q. The underlying reason for why the proposed scaling does not work well in JRA-3Q remains unclear. Nevertheless, in terms of long-term trends, the proposed theory performed better compared to the ocean advection theory on its own, even in the JRA-3Q reanalysis.

Secondly, our ABL box model assumes that ET and water vapor advection from the ocean are independent processes, which overlooks the more complex relationships between the two. In reality, a large portion of land precipitation originates from oceanic water vapor, meaning that ET is indirectly influenced by ocean advection40. Additionally, the difference between precipitation and ET, known as moisture flux convergence, suggests a connection between ocean advection and ET37. Therefore, while our analysis attributes the sources of qL to ocean advection and ET, it cannot fully disentangle the role of ocean advection that is embedded within ET trends. It should be noted that, however, ET trends are also influenced by other factors such as radiation energy, temperature, and physiological factors (e.g., CO2 fertilization effect) that may be independent of ocean advection. For instance, Simpson et al.27 demonstrated that decreases in humidity in reanalysis over the Southwestern US cannot be explained by rainfall alone, suggesting a critical role for other processes including land surface processes.

Thirdly, our approach is not a process-based model, and as such, it cannot explain why ET remained relatively steady in reanalysis but intensified in CMIP6 climate simulations. This discrepancy could be related to surface parameterizations, considering factors such as stomatal closure due to the CO2 fertilization effect34. The limitations on ET due to soil moisture are another potential mechanism23,24. To better grasp the origin of this issue, future studies may explore the relationships between precipitation, soil moisture, ET, and atmospheric humidity.

Methods

ERA5 and JRA-3Q reanalysis

We employed ERA5, the latest reanalysis product from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)30, and JRA-3Q, the latest reanalysis product from the Japan Meteorological Agency31. It is worth noting that, in this study, we deliberately excluded MERRA2 reanalysis, another widely used reanalysis product by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). This decision was based on MERRA2’s limitation of not assimilating in situ humidity observations and its documented tendency to overestimate specific humidity trends27.

We obtained ERA5 single level (near-surface) output from the Climate Data Store (CDS) of ECMWF (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7)42, and JRA-3Q single level (near-surface: 2 m height) output at 1.25 degree spatial resolution from the Data Integration and Analysis System (DIAS) (https://doi.org/10.20783/DIAS.645)43. We obtained monthly records of latent heat flux, air pressure, air temperature, and dewpoint temperature for the period of 1980–2022. We then calculated ET from latent heat flux, α from temperature, and RH from temperature, air pressure, and dewpoint temperature using the bigleaf R package44.

Climate models

We incorporated data from 27 of the climate models within CMIP632. The complete list of the utilized climate models is detailed in Supplementary Table 1. For the analysis, we employed the Historical simulation covering the period from 1980 to 2014. Given that the historical simulation ended in 2014, we augmented our dataset with Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5) simulations for the subsequent period from 2015 to 2022 to ensure temporal comparability with the reanalysis datasets. We obtained monthly scale output for climate models from the CDS of ECMWF (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.c866074c)45. Latent heat flux, near-surface air temperature, near-surface air specific humidity, and surface air pressure were retrieved. We then calculated ET from latent heat flux, α from temperature, and RH from temperature, air pressure, and specific humidity.

In addition to CMIP6 models, we incorporated data from 20 climate models from AMIP6 to produce Supplementary Fig. 2. The complete list of the utilized AMIP6 climate models is detailed in Supplementary Table 2. We obtained monthly scale output for AMIP6 climate models from Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) (https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/). We utilized all AMIP6 models available in CEDA archive, which provide all required variables listed above. It should be noted that the AMIP6 simulation ended in 2014, and the period of the AMIP6 simulation used in this study was from 1979 to 2014.

Derivation of the ocean advection theory

Byrne and O’Gorman17 introduced an idealized ABL box model to elucidate the relationship among horizontal moisture advection from the ocean, terrestrial ET, and the vertical relaxation flux of moisture at the top of the ABL (Supplementary Fig. 1). This idealized box model assumes a fixed ABL height and can be conceptualized as a diel-averaged ABL, similar to another ABL box model introduced elsewhere6,8. The moisture budget within the ABL box over land can be expressed as follows under the steady-state conditions \(({{\rm{i}}}.{{\rm{e}}}.,\frac{d{q}_{L}}{{dt}}=0)\):

where h is the boundary layer height, l is the length of the land inland from the coast, q is specific humidity, v is horizontal mixing velocity, w is vertical mixing velocity, and ρ is the air density. The subscripts O and L respectively denote ocean and land, while the subscript FT indicates the free troposphere immediately above the land and ocean boundary layers. Byrne and O’Gorman17 further simplified Eq. 5 by assuming that the free-tropospheric specific humidity is directly proportional to the ABL specific humidity, denoted as \({q}_{{FT},L}={\lambda }_{L}{q}_{L}\;{{{{\rm{and}}}}}\;{q}_{{FT},O}={\lambda }_{O}{q}_{O}\), where λL and λO are time constants. Also, they respectively defined \({\tau }_{1}=\frac{l}{v}\;{{{{\rm{and}}}}}\;{\tau }_{2}=\frac{{h}_{l}}{w}\) as horizontal and vertical mixing time scales, which results in following expression:

If treating ET as relatively negligible or proportional to qL, all terms in Eq. 6 include qO or qL. By assuming the ratio between τ1 and τ2 remains stable \(({{\rm{i}}}.{{\rm{e}}}.,\frac{{\tau }_{2}}{{\tau }_{1}}={constant})\), Byrne and O’Gorman17 derived a proportional relationship between qO and qL (\({{\rm{i}}}.{{\rm{e}}}.,{q}_{L}=\gamma {q}_{O}\), where γ is constant). Differentiating the proportional relationship yields Eq. 1 in the main text.

Link between the ABL box model and the proposed scaling

Here, we adopt all the assumptions proposed by Byrne and O’Gorman17 except for the negligible ET assumption. Additionally, we define \(\beta =\frac{{q}_{L}}{{q}_{O}}\) as the specific humidity ratio. Unlike constant γ in Byrne and O’Gorman17, β is treated as a variable here.

Rearranging for ET yields:

or

where \({C}_{1}=\rho {h}_{L}(1+\frac{{\tau }_{1}}{{\tau }_{2}}-{\lambda }_{L}\frac{{\tau }_{1}}{{\tau }_{2}})\;{{{{\rm{and}}}}}\;{C}_{2}=\rho ({h}_{O}-{\lambda }_{O}{h}_{O}+{h}_{L}{\lambda }_{O})\), and they are positive integers. By definition, C1 and C2 can be considered constants. Differentiating Eq. 9 yields:

Since \({\tau }_{1}=\frac{l}{v}\), and l is constant with respect to time, we can write \(\frac{\delta {\tau }_{1}}{{\tau }_{1}}=-\frac{\delta v}{v}\). Substituting this into Eq. 10 yields:

To simplify Eq. 11 into Eq. 3, two conditions must be met. First, the first two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 11 must cancel out, meaning \(\frac{\delta {q}_{O}}{{q}_{O}}+\frac{\delta v}{v}\approx 0\). Second, the term \(\frac{{C}_{1}\beta }{{C}_{1}\beta -{C}_{2}}\) must be approximately equal to 1, which holds when \({\tau }_{1}\gg {\tau }_{2}\). When these conditions are satisfied, Eq. 11 simplifies to:

Since \(\beta =\frac{{q}_{L}}{{q}_{O}}\), Eq. 12 is equivalent to Eq. 3 in the main text.

Application of the proposed equations to reanalysis and GCMs

The proposed equations were applied to each land grid cell. Specifically, we first calculated the climatology and anomaly of ET, qL, TL, and RHL for each month and land grid. For the ocean advection term (qO), climatology and anomaly of qO were computed for each ocean grid cell and subsequently zonal averaged for each latitude. The zonal averaged ocean advection term was then introduced to each land grid cell for the application of the proposed equations. The resulting values for each land grid cell and month were spatially averaged with cosine-latitude weighting before computing annual averages.

A practical challenge of the proposed equation arose when attempting to calculate relative changes in ET. At some grid cells where ET climatology is close to zero such as dry or cold regions, relative changes in ET can increase (or decrease) infinitely. To resolve this issue, we added a small number (ε) to the denominator to stabilize the calculations:

where LE represents latent heat flux. We set ε as 5 W m−2.

Data availability

All data used in the main text and the supplementary information are publicly available. The ERA5 reanalysis data can be obtained from CDS of ECMWF (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7), the JRA-3Q reanalysis data can be obtained from DIAS (https://doi.org/10.20783/DIAS.645), the CMIP6 models outputs can be obtained from CDS of the ECMWF (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.c866), and the AMIP6 models outputs can be obtained from CEDA Archive (https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/).

Code availability

The code used for these analyses will be available on request.

References

Milly, P. C. D. et al. Stationarity is dead: whither water management? Science 319, 573–574 (2008).

Jung, M. et al. Recent decline in the global land evapotranspiration trend due to limited moisture supply. Nature 467, 951–954 (2010).

Fisher, J. B. et al. The future of evapotranspiration: global requirements for ecosystem functioning, carbon and climate feedbacks, agricultural management, and water resources. Water Resour. Res. 53, 2618–2626 (2017).

Milly, P. C. D. & Dunne, K. A. Colorado River flow dwindles as warming-driven loss of reflective snow energizes evaporation. Science 367, 1252–1255 (2020).

Gentine, P., Chhang, A., Rigden, A. & Salvucci, G. Evaporation estimates using weather station data and boundary layer theory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 11,661–611,670 (2016).

McColl, K. A., Salvucci, G. D. & Gentine, P. Surface flux equilibrium theory explains an empirical estimate of water-limited daily evapotranspiration. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2036–2049 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Relative humidity gradients as a key constraint on terrestrial water and energy fluxes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 5175–5191 (2021).

Vargas Zeppetello, L. R. et al. Apparent surface conductance sensitivity to vapour pressure deficit in the absence of plants. Nat. Water 1, 941–951 (2023).

Kim, Y., Garcia, M., Black, T. A. & Johnson, M. Assessing the complementary role of surface flux equilibrium (SFE) theory and maximum entropy production (MEP) principle in the estimation of actual evapotranspiration. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022MS003224 (2023).

McColl, K. A. & Tang, L. I. An analytic theory of near-surface relative humidity over land. J. Clim. 37, 1213–1230 (2024).

Ma, H.-Y. et al. CAUSES: On the role of surface energy budget errors to the warm surface air temperature error over the central United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 2888–2909 (2018).

Dong, J., Lei, F. & Crow, W. T. Land transpiration-evaporation partitioning errors responsible for modeled summertime warm bias in the central United States. Nat. Commun.13, 336 (2022).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., McVicar, T. R., Miralles, D. G., Yang, Y. & Tomas-Burguera, M. Unraveling the influence of atmospheric evaporative demand on drought and its response to climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 11, e632 (2020).

Willett, K. et al. HadISDH land surface multi-variable humidity and temperature record for climate monitoring. Clim. Past 10, 1983–2006 (2014).

Simmons, A. J., Willett, K. M., Jones, P. D., Thorne, P. W. & Dee, D. P. Low-frequency variations in surface atmospheric humidity, temperature, and precipitation: Inferences from reanalyses and monthly gridded observational data sets. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012442 (2010)

Chadwick, R., Good, P. & Willett, K. A Simple Moisture Advection Model of Specific Humidity Change over Land in Response to SST Warming. J. Clim. 29, 7613–7632 (2016).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Understanding decreases in land relative humidity with global warming: conceptual model and GCM simulations. J. Clim. 29, 9045–9061 (2016).

Byrne, M. P. & O’Gorman, P. A. Trends in continental temperature and humidity directly linked to ocean warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 4863–4868 (2018).

Sherwood, S. & Fu, Q. A drier future? Science 343, 737–739 (2014).

Berg, A. & Sheffield, J. Climate change and drought: the soil moisture perspective. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 4, 180–191 (2018).

Kim, Y., Garcia, M. & Johnson, M. Land-atmosphere coupling constrains increases to potential evaporation in a warming climate: Implications at local and global scales. Earth’s Future 11, e2022EF002886 (2023).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M. et al. Recent changes of relative humidity: regional connections with land and ocean processes. Earth Syst. Dynam. 9, 915–937 (2018).

Berg, A. et al. Land–atmosphere feedbacks amplify aridity increase over land under global warming. Nature Climate Change 6, 869–874 (2016).

Zhou, W., Leung, L. R. & Lu, J. The Role of Interactive Soil Moisture in Land Drying Under Anthropogenic Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105308 (2023).

Douville, H. & Plazzotta, M. Midlatitude Summer Drying: An Underestimated Threat in CMIP5 Models? Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 9967–9975 (2017).

Dunn, R. J. H., Willett, K. M., Ciavarella, A. & Stott, P. A. Comparison of land surface humidity between observations and CMIP5 models. Earth System Dyn. 8, 719–747 (2017).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Observed humidity trends in dry regions contradict climate models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2302480120 (2024).

Allan, R. P. et al. Advances in understanding large-scale responses of the water cycle to climate change. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1472, 49–75 (2020).

Douville, H. & Willett, K. M. A drier than expected future, supported by near-surface relative humidity observations. Sci. Adv. 9, eade6253 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kosaka, Y. et al. The JRA-3Q Reanalysis. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 102, 49–109 (2024).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Seltzer, A. M., Blard, P.-H., Sherwood, S. C. & Kageyama, M. Terrestrial amplification of past, present, and future climate change. Science Adv.9, eadf8119 (2023).

Douville, H. et al. Drivers of the enhanced decline of land near-surface relative humidity to abrupt 4xCO2 in CNRM-CM6-1. Clim. Dyn. 55, 1613–1629 (2020).

O’Gorman, P. A. & Muller, C. J. How closely do changes in surface and column water vapor follow Clausius–Clapeyron scaling in climate change simulations? Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 025207 (2010).

Willett, K. M., Dunn, R. J. H., Kennedy, J. J. & Berry, D. I. Development of the HadISDH.marine humidity climate monitoring dataset. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2853–2880 (2020).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. Weakening of tropical Pacific atmospheric circulation due to anthropogenic forcing. Nature 441, 73–76 (2006).

Shrestha, S. & Soden, B. J. Anthropogenic weakening of the atmospheric circulation during the satellite era. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104784 (2023).

Jacobson, T. W. P. et al. An unexpected decline in spring atmospheric humidity in the interior Southwestern United States and implications for forest fires. J. Hydrometeorol. 25, 373–390 (2024).

Milly, P. C. D. & Dunne, K. A. Potential evapotranspiration and continental drying. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 946–949 (2016).

Hersbach, H., et al ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present data sets. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7 (2023).

Numerical Prediction Division, I. I. D. The Japanese reanalysis for three-quarters of a century data sets. Data Integration and Analysis System (DIAS) https://doi.org/10.20783/DIAS.645 (2022).

Knauer, J., El-Madany, T. S., Zaehle, S. & Migliavacca, M. Bigleaf—an R package for the calculation of physical and physiological ecosystem properties from eddy covariance data. PLOS ONE 13, e0201114 (2018).

Copernicus Climate Change Service, C. D. S. CMIP6 climate projections data sets. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.c866074c (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) Grant 21SUESIELH. We are grateful for ERA5 and JRA-3Q reanalysis developer groups and the CMIP6 climate modeling group. We also appreciate the efforts of CDS of ECMWF, DIAS, and CEDA in producing and making available these datasets. We express our thanks to the development of the ocean advection theory (by M. Byrne, P. O’Gorman, R. Chadwick, P. Good, K. Willett, and others) that inspired our study. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which has substantially improved our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.K., M.S.J. Methodology: Y.K., M.S.J. Investigation: Y.K., M.S.J. Visualization: Y.K. Supervision: M.S.J. Writing—original draft: Y.K. Writing—review & editing: M.S.J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Isla Simpson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Johnson, M.S. Deciphering the role of evapotranspiration in declining relative humidity trends over land. Commun Earth Environ 6, 105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02076-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02076-9

This article is cited by

-

Actual evapotranspiration dynamics in Italy: trend detection and regional clustering analysis

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2026)

-

Climate change has increased global evaporative demand except in South Asia

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Investigating the Dependence Structure of Temperature and Precipitation Concentration with Evapotranspiration in Finland

Water Resources Management (2025)