Abstract

Volcanic supereruptions are considered among the few drivers of global and existential catastrophes, with recent hypotheses suggesting massive volcanic stratospheric sulfate injection could instigate major shifts in global climate. The absence of supereruptions during recent history as well as large uncertainties on eruption ages limits understanding of the climatic risk they impose. Polar ice cores have well-resolved continuous age models, record past temperature, and contain volcanic sulfate and cryptotephra deposits which can be geochemically fingerprinted to determine eruption timing and improve stratospheric sulfur loading estimates. Here, we provide an age of 79,500 years for the Atitlán Los Chocoyos supereruption, one of the largest Quaternary eruptions, by identifying tephra shards in ice cores from both Greenland and Antarctica. This ice core age is supported by a revised marine sediment core stratigraphy age for the Los Chocoyos ash layer. Through comparison with well-dated ice-core temperature proxy records, our study suggests that despite being one of the largest sulfur emissions recorded in ice cores, the Los Chocoyos supereruption did not trigger a millennial-scale cold period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supereruption-scale volcanic events pose a global catastrophic risk due to their climatic forcing by mass injection of sulfate aerosol into the stratosphere1,2. Once in the stratosphere, these aerosols have residence times of several years which can lead to surface cooling of up to several degrees.

Temperature proxy evidence coupled with ice core records of volcanism and historical observations provides key insights into how ≤VEI 7 (volcanic explosivity index3) eruptions impacted regional and global climates during the Common Era4,5. Paleoenvironmental records have also indicated that asymmetrical hemispheric cooling induced by volcanic sulfate injections can cause shifts in the position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) affecting tropical atmospheric circulation and rainfall patterns6,7. However, no supereruption-scale events (≥VEI 8) are known to have occurred in recorded history, therefore, we must look to paleoenvironmental archives to understand their impact on global climate.

The timing of some of the largest eruptions of the last glacial period, relative to abrupt climate transitions recorded in Greenland ice cores8 has led to hypotheses that volcanism may play a key role in initiating millennial-scale climate changes between warm interstadial periods and cold stadials9,10. It is widely accepted that these Northern Hemisphere temperature oscillations (e.g., Dansgaard-Oeschger events) are linked with changes in circulation and sea ice in the North Atlantic11,12. However, the exact sequence of events that culminates in Dansgaard-Oeschger (D-O) climate variability is not fully understood and is still debated13,14. Explosive volcanism has been suggested as a trigger of D-O cold events due to the potential amplification of Northern Hemisphere cooling initiated by volcanic aerosols, and prolonged by sea-ice expansion and slowing of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) in the years following sulfate injection9,15,16.

This hypothesized link between volcanism and major climate shifts is underpinned by the age of the Younger Toba Tuff (YTT) supereruption of Toba caldera, Sumatra (73.7 ± 0.6 ka, 2σ17,18), which is within age uncertainty of Greenland Stadial 20 (GS-20, 74.1 ka8), one of the more pronounced stadial events of the last glacial cycle19. More recently, a zircon rim (U-Th)/He age of 74.8 ± 3.4 ka (2σ)20 for the largest known eruption in Central America, the Los Chocoyos (LCY) supereruption of Atitlán caldera, present-day Guatemala, is significantly younger than previous eruption age estimates of ~84 ka21. This updated radioisotopic age for LCY is within the dating uncertainty of both YTT and GS-20, thus leading to the suggestion that the two eruptions occurred in a geologically short time interval and at the transition to stadial conditions22. This prompts further questions about whether back-to-back supereruption sulfur injections and associated climate system feedback could initiate or exacerbate transitions to millennial-scale cold periods22,23. To further understand this hypothesized link, we require both (1) precise ages for supereruptions by identification of volcanic evidence within continuous palaeostratigraphic records that also characterize millennial-scale climate transitions, and (2) better estimates of stratospheric sulfur injection from supereruptions.

Here, we address these needs by examining evidence of the LCY supereruption in marine sediment and ice core records with well-resolved age models to determine an eruption age of 79.5 ± 3.4 ka (2σ), compare timing relative to YTT, and evaluate the potential climatic impacts of the LCY supereruption.

Sediment core evidence

The Los Chocoyos supereruption is, by volume of erupted products (~1220 km3 20), the largest known Quaternary eruption in Central America. It provides a key tephrostratigraphic marker horizon in dozens of palaeorecords including marine sediment cores from the Equatorial Eastern Pacific (EEP), Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea21,24,25, lacustrine sediment cores from Lake Petén Itzá in Northern Guatemala26, and terrestrial sequences across the Guatemalan Highlands20,27. Due to this widespread deposition, benthic foraminifera oxygen isotope (δ18O) records from marine sediment cores containing prominent ash horizons can be used to investigate the timing of the LCY supereruption.

The marine δ18O curve records a combination of global ice volume and deep-sea temperatures, with warmer and colder periods defined as Marine Isotope Stages (MIS)28,29. The alignment of global marine δ18O records30 and availability of high precision ages for key MIS events of the last 240 ka years from U/Th coral dating31 allows for independent age estimations of tephra horizons identified in the marine realm.

Previously, a distinct, visible 2 cm LCY tephra horizon identified in Eastern Equatorial Pacific EEP sediment core V19-29 (see “Methods and materials” section) was used to determine an eruption age of ~84 ka using age models based on benthic δ18O records21,32. Based on the δ18O stratigraphic position of the confirmed LCY tephra horizon in V19-29, we visually identified a 3 cm tephra horizon in neighboring EEP sediment core V19-30 (see “Methods and materials” section) ~50 km northeast of V19-29 and ~2100 km southeast of Atitlán caldera (Supplementary Fig. 1), which has the highest temporal resolution benthic δ18O records in the region over this time period33 (Fig. 1). Using major oxide geochemistry (see “Methods and materials” section), we match the rhyolitic tephra present in V19-30 to proximal units of initial tephra fall, ignimbrite and surge deposits from the LCY eruption found in terrestrial, lacustrine and marine settings20 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Oxygen isotope (δ18O) benthic foraminifera records from marine sediment cores V19-3033 from the Eastern Equatorial Pacific (red) containing LCY tephra horizon identified in this study (red vertical bar), and MD97-215135 from the South China Sea (black) containing previously identified YTT tephra horizon34 (black vertical bar). Dashed lines show the inferred age of each tephra horizon for comparison. Sediment age model MIS transitions based on the global LR04 stack shown in the bar above the x-axis30.

Tephra shards analyzed in ice cores NEEM (red diamonds) and EDC (red squares), and marine sediment core V19-30 (red triangles), that correlate with LCY major and minor element geochemistry. A single LCY-correlating shard found in NEEM ice core ~16 years prior to the later group (n = 3) is indicated by a light-red diamond. All marine sediment and ice-core shards analyzed are compared to proximal terrestrial and lacustrine LCY ash geochemistry measured as part of this study (light blue circles) and previously published data (dark blue circles)20, including tephra fall, ignimbrite, and surge deposits. Error bars shown represent 2σ of replicate analysis of tephra secondary standards (Lipari ID3506 for marine sediment tephra and Old Crow for ice core tephra107), measured during the relevant analysis session under the same conditions. All wt.% totals are normalized to 100%. Details of analytical conditions can be found in the “Methods and materials” section.

The occurrence of LCY ash in core V19-30 is coincident with a minima in benthic δ18O known as MIS 5.1, carrying a high precision age of 80.5 ± 0.9 ka (2σ) from U/Th dating of surface corals31. This age precision cannot be mapped directly to the tephra deposit due to uncertainties in the relative timings of sea-level highstands and their benthic δ18O expression (which may vary on the order of 1000 years as a function of ocean circulation and sediment bioturbation). However, this radiometric age provides a useful independent check on the absolute age of the eruption. Furthermore, benthic δ18O stratigraphy can be used to compare the timing of LCY in the EEP to a YTT tephra horizon recorded in a South China Sea sediment core MD97-2151 during the MIS 5/4 transition (see “Methods and materials” section; Supplementary Fig. 1)34,35. This comparison reveals a substantial temporal separation between these two supereruptions of around 5000 years (Fig. 1).

Ice core evidence

Polar ice cores preserve evidence of both proximal and distal volcanic eruptions as deposits of sulfate aerosol and/or tephra shards (or cryptotephra) within a well-resolved age model, allowing for precise ages to be assigned to eruptions matched by tephra geochemical fingerprinting36,37,38,39. We identified and sampled a large volcanic sulfate peak at 79.5 ± 3.4 ka (2σ) (AICC2012; Antarctic Ice Core Chronology 201240) in Greenland ice cores NGRIP and NEEM, and Antarctic ice core EDC (see “Methods and materials” section), separated from YTT candidates by ~6000 years41,42,43 and consistent with the LCY inferred age based on δ18O marine sediment stratigraphy discussed above.

Previous work confirms the stratospheric and likely tropical origin of this eruption sulfate deposit, which is the second largest of the last 100 ka in the EDC core, by the presence of one of the largest mass-independent fractionation sulfur isotope signatures on record from a volcanic aerosol ice core deposit (Δ33S = +2.99 ± 0.14 ‰, 2σ44). In this case, the large positive Δ33S rules out a contribution of proximal, tropospheric sulfate which would result in a muted or 0 ‰ Δ33S value in the ice core45,46,47. This sulfur isotope evidence, as well as the exceptional magnitude of S deposition (Supplementary Fig. 2) mark this peak as the most likely candidate for LCY in the ice-core record in agreement with the sediment core age.

We sub-sampled NEEM, NGRIP, and EDC ice cores at high time resolution across the targeted peaks (see “Methods and materials” section), allowing us to examine the time evolution of sulfate deposition and assign a precise depth and age to identified tephra shards. This reveals the precise stratigraphic relationship between the tephra and sulfate deposition which helps constrain critical eruption source parameters for past eruptions48,49.

We identified and measured major oxide geochemistry of 15 tephra shards (<30 μm) in 6 samples of the EDC core, and 54 shards in 7 samples of the NEEM core. Previous studies have shown that for tropical eruptions, tephra shards in ice are deposited before or within the peak of sulfate37,38,50. Thus, focusing purely on samples that were immediately prior to, or associated with the large peak in sulfate concentration, we found 1 geochemically identical tephra population in NEEM and two populations in EDC. The NEEM population (n = 3) and one of the EDC populations (n = 2) geochemically correlate across all major oxides with the LCY tephra composition from proximal deposits (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). While this high-silica, rhyolitic composition tephra is common to many arc-system volcanoes49, there are no other candidates ≥VEI 4 (the minimum eruption size required for tephra to reach Greenland51) with this close a major and minor element geochemical match and within age uncertainty of the ice core peak, as listed by the LaMEVE (Large Magnitude Explosive Volcanic Eruptions) database52,53 (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Although trace element analysis of ice core tephra would strengthen our correlation, the extremely small glass area of identified LCY-correlating tephra (<10 μm2) did not allow for such analysis to take place and would have yielded data of insufficient quality to strengthen correlation (see “Methods and materials” section).

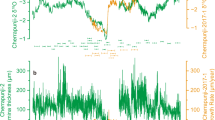

Sulfate (SO42−) concentration measured by ion chromatography of 1–3 cm subsamples taken from across the volcanic peak in ice cores (a) NEEM (Greenland) and (b) EDC (Antarctica). In both panels, dashed lines indicate samples where one or more tephra glass shards were found and analyzed for major oxide geochemistry. Subsamples containing tephra populations that match LCY geochemistry are indicated by red stars and red shading. Light-red shading and stars show single-shard occurrence before the main population that correlates with LCY in the NEEM ice core. Additional samples where tephra is correlated to a known source (see Supplementary Fig. 4) are indicated by black shapes: Circle = Grímsvötn, Iceland55; Cross = Eastern Aleutian Arc56; Triangle = Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica54. Bracketed numbers indicate how many shards of correlated composition were measured. Smaller peaks in NEEM SO42− concentration on either side of the largest peak (LCY) can be attributed to the events identified by these tephra populations.

The second EDC population is a group of phonolite-trachyte shards (n = 5) at the sulfate concentration maximum which show similarity to the geochemistry of Mount Berlin eruptions from Marie Byrd Land (Antarctica) (Supplementary Fig. 4)54. Although it cannot be ruled out that this eruption contributed a minor amount of sulfate to the peak, the large stratospheric sulfur isotope signal44 suggests minimal tropospheric input and dismisses a local eruption as the primary sulfate source.

Two other tephra populations in our sampled interval of the NEEM ice core coincide with minor increases in sulfate that substantially pre- and post-date the large sulfate deposit of interest (Fig. 3) and are therefore ruled out as potential sources of the targeted eruption. These populations geochemically correlate with previously reported cryptotephra horizons in Greenland ice cores that are consistent with our sample ages, originating from Grimsvötn (Iceland)55 and the Eastern Aleutian Arc56 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

A further 8 shards that do not belong to any geochemical populations are deposited prior to or during the sulfate peak in NEEM and EDC. Comparison to ≥VEI 4 eruptions within dating uncertainty of 79.5 ka reported by the LaMEVE database52,53 finds no volcanic source matches for 7 of these shards (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 5), which are likely the result of unknown background events that would have occurred across the sampled time period57. One of these individual shards also matches LCY geochemistry (Fig. 2), and it is deposited in a sample ~16 years prior to the LCY population in NEEM (Fig. 3). As high-silica end members are common in multiple volcanic provenances49, it is plausible that this shard is the product of a smaller, unknown eruption prior to LCY. Although this is a curious feature of our data, we focus our attention on samples where multiple shards of matching geochemical composition were identified in the same or neighboring subsamples.

The occurrences of LCY-correlating tephra populations at both poles, coincident with an exceptionally large sulfate deposit exceeding that of most of the largest known volcanic eruptions previously identified in ice cores58,59, strongly supports LCY as the source of this bipolar ice core volcanic deposit. This exceptional transport of tephra particles >7000 km to Greenland and >11,000 km to Antarctica allows us to assign an ice-core age of 79.5 ± 3.4 ka (2σ; AICC2012) to the LCY supereruption and creates the first confirmed bipolar supereruption stratigraphic tie between Greenland and Antarctic ice. This finding also demonstrates the potential for dual-hemisphere distribution of microscopic tephra from colossal tropical eruptions and we underscore that such bipolar tephra deposition has only been detected previously for the 1257 CE Samalas eruption60, which was the largest stratospheric S emission of the Common Era61.

Los Chocoyos age constraints

Our revised age for the Atitlán LCY supereruption as determined by the AICC2012 ice core chronology for the EDC core is 79.5 ± 3.4 ka (2σ) and is within error of the marine sediment core δ18O peak associated with MIS 5.1 (dated by U-Th in surface corals as a sea-level highstand at 80.5 ± 0.9 ka (2σ)31, Fig. 1). Although within joint 2σ uncertainty, it is ~5000 years older than the recently reported radioisotopic age estimate of 74.8 ± 3.4 ka (2σ)20.

This radioisotopic age estimate is a weighted mean of a disperse dataset (MSWD = 3.3) of several zircon rim (U-Th)/He ages weighted by their absolute uncertainty, which due to the correlation of uncertainty with age, introduces a bias towards younger weighted mean ages62. Based on the guidance of Flowers et al. 62, when a mean weighted by relative uncertainty is calculated using the same (U-Th)/He dataset (found in20), we find an age of 78.7 ± 3.6 ka (2σ), in agreement with our ice core and sediment stratigraphy ages. This excellent agreement between radioisotopic, marine sediment, and ice-core ages provides a key chronostratigraphic tie point linking terrestrial, marine, and polar environments with independent radiometric ages.

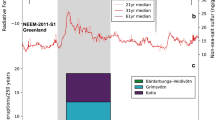

Additionally, the separation of the identified LCY sulfate peak and YTT candidates in the ice core records41,42,43 (Fig. 4), the δ18O stratigraphy separation of LCY and YTT ash in the marine realm (Fig. 1), and independent radioisotopic dating of LCY (78.7 ± 3.6 ka, 2σ) and YTT (73.7 ± 0.6 ka, 2σ17,18,63), provide evidence to rule out back-to-back supereruptions at the onset of GS-20.

a Continuous ice-core SO42− concentration records for Antarctic ice core EDC (blue)84 and Greenland ice core NGRIP (black) (this study; see “Methods and materials” section). LCY identified peak(s) and age of maximum SO42− point indicated (all AICC2012 age model40). Hypothesized YTT eruption candidates T1 and T241,42,43 also labeled to demonstrate the separation of the two events. b Continuous δ18O temperature proxy records for EDC (blue)123 and NGRIP (black)8,81 with measurements made at a time resolution of 10 and 20 years, respectively. Timing of LCY tephra occurrence in each hemisphere shown as dashed vertical lines. c Enlarged section of δ18O records for years between 80 and 79 ka. The timing of LCY in Antarctica (blue) and Greenland (black) shown by the dashed vertical line.

Sulfur loading and climate impact

A key factor in understanding the climatic impact of the LCY supereruption is estimating the volcanic stratospheric sulfur injection (VSSI). Petrologic estimates suggest a total erupted sulfur mass of 523 ± 94 Tg S26,64,65. However, this method relies on erupted volume estimates which carry large uncertainties due to reliance on sparse datasets of tephra layer thickness in distal sediment cores26. There are also well-known discrepancies between petrologic S emission estimates and measurements of S from remote sensing, which can reflect processes in the magmatic system (i.e., the accumulation of S in fluid and gas phases) or in their eruptive column and plume (i.e., volatile scrubbing and removal by water, ice, and ash66).

Following the identification of LCY tephra and synchronization of Greenland and Antarctic ice cores at the volcanic deposit depth, new and existing continuous sulfate and sulfur concentration data are used to make the first ice-core-based volcanic stratospheric sulfate injection (VSSI) estimate for LCY. We use established methods44,59,61 that take into account layer thinning, ice accumulation rates, and non-volcanic background sulfate concentrations (see “Methods and materials” section). In addition to NEEM, NGRIP and EDC, further high-resolution sulfate data from corresponding LCY candidate peaks identified in Greenland ice core GISP2 and Antarctic ice core EDML are used to improve our estimation of sulfur deposition at both poles. Deposit totals from each ice core are averaged to generate totals for Greenland (348 kg km−2) and Antarctica (328 kg km−2), before using the transfer function for tropical eruptions61 to estimate a total VSSI of 226 ± 48 Tg S (1σ) for LCY (see “Methods and materials” section).

This value is comparable with ice core estimates for YTT candidates (180 Tg S43 and 233 Tg S42) and the largest eruptions of the last 60 ka58,59, but is less than half of the petrologic estimate of 523 ± 94 Tg S for LCY. Uncertainties in the ice-core method that may contribute to this discrepancy include limitations of the transfer function used to convert sulfate deposited at the poles to a total stratospheric loading61, variability in volcanic plume transport (e.g., the influence of the polar vortex preventing high-latitude deposition67), and factors affecting sulfate deposition and preservation such as wind erosion at low snow accumulation sites68. An additional consideration is that for large-volume eruptions, stratospheric sulfur removal in the weeks following eruption is enhanced by uptake on volcanic ash and coagulation of concentrated sulfate aerosol in the initial phases of eruption69,70,71. The expedited fall-out of these larger particles reduces the amount of stratospheric sulfur being transported long distances, such as to the polar ice sheets. This reduction in transport to the poles may contribute to the difference in ice core and petrologic estimates of VSSI for LCY and other, large-volume eruptions42.

Even if we treat ice core estimations as a minimum, the 226 Tg S VSSI of LCY is several times greater than climatically significant tropical eruptions of the Common Era (e.g., 59 Tg S for Samalas 1257 CE, 28 Tg S for Tambora 1815 CE61) indicating substantial climate forcing potential following the eruption. Modeling that uses the larger petrologic estimates of sulfur loading predicts extreme surface cooling following the LCY eruption of >6 K, increasing sea ice by ~40% in the 3 years following eruption, but with recovery to pre-eruptive conditions within 20–30 years64. The 10–20-year resolution of δ18O polar temperature reconstructions from ice cores should record cooling of this magnitude as a negative perturbation in the δ18O record. Indeed, the timing of the eruption occurs in a local, short-term (10–20 years) δ18O minimum in NGRIP and an even more pronounced δ18O change in EDC (Fig. 4c), reflecting colder temperatures that could also favor enhanced sea-ice. However, more broadly, these short-term cool events occurred during a period of generally stable polar temperatures within the latter portion of a warm period, Greenland Interstadial 21 (GI-21), expressed as sustained, elevated δ18O (Fig. 4b)8. This centennial-scale stability of the δ18O records around the LCY eruption indicates that any volcanic-induced atmosphere-ocean-sea ice climate feedbacks were short-lived (decadal), which is consistent with recent models64. Records of the position of the ITCZ from speleothems and high-resolution marine sediment cores72,73 also do not show any clear change following this event (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

These lines of evidence lead us to conclude that LCY was not a driver of millennial-scale climate changes and did not initiate feedback mechanisms that prolonged cooling on greater-than-decadal timescales. Proxy-based reconstructions and modeling have demonstrated that centennial to millennial climate system responses following new volcanic eruptions are likely dependent on background conditions that are sensitive to change74,75, or occur after successive, decadal-paced eruptions15,76. It is possible that warm interstadial climate conditions with strong overturning circulation and reduced sea ice at the time of LCY were favorable for climate recovery within 20–30 years. The stratigraphic separation of LCY and YTT we have shown in this study (Fig. 1) also rules out the prospect of sustained climate response from two supereruptions separated by several thousand years.

An additional case study of potential climatic impacts from supereruptions is available from the Oruanui supereruption of Taupo in New Zealand. The 25.5 ka Oruanui supereruption, which occurred during glacial conditions, has been previously identified by major element tephra geochemistry in Antarctic ice77 and is associated with a bipolar sulfate deposit and estimated VSSI of 117 Tg S59. The long-term stability of δ18O at the poles following Oruanui78 suggests the aerosol forcing did not amplify the existing cold glacial conditions, nor initiate any centennial or millennial-scale cooling. Ice-core evidence of these two supereruptions alongside temperature proxy records, occurring during different background climate states, sea-ice extent, CO2 levels, and ocean circulation, suggests that multiple scenarios exist that are resilient to long-term climate changes from supereruption-scale stratospheric sulfate injections and their associated feedbacks.

Conclusions

High time resolution analyses of Antarctic and Greenland ice cores identify cryptotephra shards matching the LCY supereruption at 79.5 ± 3.4 ka (2σ). This precise timing is consistent with LCY eruption ages from marine sediment cores and radioisotopic evidence. While future development of trace element analyses for these exceptionally small (<10 µm) ice core tephra shards would strengthen this ice core correlation, it is important to underscore there are no other major sulfate peaks present in ice cores from both hemispheres that are consistent with the timing constraints from both sediment cores and radioisotopic dating.

While stratospheric sulfate injection of supereruption magnitude undoubtedly impacts climate and may be amplified by sea-ice feedbacks, we find no evidence for prolonged multi-decadal to centennial-scale cooling following LCY. These results underscore that the climate impact from supereruptions can be short-lived, even for stratospheric sulfate loadings of 226 ± 48 Tg S, with climate returning to pre-eruptive conditions within decades. Further efforts to both identify large-magnitude events in archives which are integrated with high-resolution palaeoclimate records, and investigate the diverse controls on VSSI79, are essential for improving our understanding of supereruption-climate interactions.

Methods and materials

Marine sediment core age models

Using the δ18O stratigraphic position of Los Chocoyos (LCY) ash previously identified in Eastern Equatorial Pacific core V19-29 (3.583° S, 83.933° W, 3157 m water depth)21,32 (Supplementary Fig. 1), we identified LCY ash at 610–613 cm depth in a nearby marine sediment core V19-30 (3.383° S, 83.517° W, 3091 m water depth), ~50 km NE of V19-29 and containing a higher-resolution benthic δ18O record33. These deep-marine cores are composed primarily of green-gray diatomaceous foraminiferal ooze with burrowing throughout. The sedimentation rate of ~7 cm/ka has provided valuable, detailed carbon and oxygen isotope records from the Pacific for past studies32,33.

We updated the published age model for V19-30, by tying the transitions between Marine Isotope Stages (MIS)28,29 in the high-resolution benthic δ18O record33 to the LR04 benthic oxygen isotope stack30, and linearly interpolating between ties. We adopt the same approach to update the age model of sediment core MD97-2151 from the South China Sea (8.728° N, 109.869° E, 1598 m water depth) which contains the YTT ash layer34. The MIS is easily identified in the high-resolution benthic δ18O record in both cores28,29,33,35,80 (Fig. 1) and our revised age-depth ties for both cores are identified in Supplementary Table 1. The depth of the base of the LCY ash horizon at 613 cm in V19-30 is coincident with the minimum δ18O value in MIS 5.1, which has a radiometric age of 80.5 ± 0.9 (2σ) ka from U/Th dating of surface corals31.

Ice core sulfate records

Published and unpublished records of sulfate and conductivity were collated and used to identify an exceptionally prominent volcanic sulfate horizon in volcanically synchronized81 Greenland ice cores NGRIP (North Greenland Ice Core Project82; 75.10° N; 42.32° W, 2,917 m elevation), NEEM (North Greenland Eemian Ice Drilling; 77.45° N; 51.07° W, 2479 m elevation) and GISP2 (Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2; 72.58° N, 38.47° W 3203 m elevation) dated 79.48 ± 1.53 ka BP AICC2012 (Antarctic Ice Core Chronology 201240;) (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 2). Equally prominent horizons synchronous within age uncertainty exist in the Antarctic ice core EDC (EPICA Dome C83; 75.1°S; 123.35° E, 3233 m elevation)84 dated 79.51 ± 1.65 ka BP AICC201240 and in EDML (EPICA Dronning Maud Land85; 75.00° S, 00.07° E, 2892 m elevation) dated 79.75 ± 1.51 ka BP AICC201240 (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 2).

NGRIP was analyzed using a photometric sulfate detection system coupled to a continuous flow analysis (CFA) system86,87. Relative errors are typically around 15%, with a detection limit for routine ice-core analyses of 40 ng g−1. The NGRIP sulfate record has been widely used to detect and quantify volcanic sulfate depositions over Central Greenland during the Glacial40,59,78,88,89,90,91,92. Sulfate in both EDML and EDC were continuously analyzed using Fast Ion Chromatography (FIC)93,94 coupled to a CFA system95. Both records have been widely used for volcanic ice-core synchronization41,58,78,93,96,97,98,99 and to detect and quantify volcanic sulfate depositions over Antarctica44,48,58,59,88,100.

New high-resolution continuous sulfur concentration measurements were made between 2635 m and 2638 m depth (encompassing 400 years) for the GISP2 ice core using an Element2 sector field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) coupled to a CFA system at the Desert Research Institute5,101 (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Ice core age models

Deep Greenland ice-core records (NEEM, NGRIP, GISP2) are volcanically synchronized to the GICC05modelext chronology for the past 100 ka (Greenland Ice Core Chronology 2005 model extension102), which is based on glacial flow modeling for ages >60 ka. Deep Antarctic ice cores are dated using the AICC2012 chronology, a Bayesian dating framework incorporating absolute and relative information from the ice phase (e.g., radionuclides, volcanic proxies) and gas-phase (e.g., CH4, air isotopes) from both hemispheres40.

Bipolar normalization between Greenland and Antarctica has been achieved continuously going back to 60 ka58,59,103. A floating volcanically normalized section exists from ~74 to 76 ka BP AICC2012 encompassing sulfate spikes considered candidates for the ~74 ka BP Younger Toba Tuff eruption41. No bipolar and very few volcanic stratigraphic links between Antarctica and Greenland exist beyond this, explaining the differences in age for the layer we target as the Atitlán LCY eruption candidate eruption (79.51 ka BP AICC2012 in EDC, 79.74 ka BP AICC2012 in EDML, 80.03 ka BP GICC05modelext and 79.48 ka BP AICC2012 in NEEM, NGRIP and GISP2).

The relative age difference between the oldest YTT candidate (i.e., the oldest bipolar volcanic stratigraphic marker) and our LCY candidate at about 80 ka BP is 4040 years (NGRIP, GICC05modelext), 4024 years (EDC, AICC2012) and 4257 years (EDML, AICC2012), respectively (Supplementary Table 3). The ice core chronology (AICC2012) age uncertainty at the depth of the LCY candidate peak analyzed is reported by ref. 40 as 1.5 ka (1STD) for EDML and NGRIP, and 1.7 ka (1STD) for EDC. To be as conservative as possible, we adopt the larger of these reported for EDC and report uncertainty as 2σ.

A recent update of the Antarctic Ice Core Chronology (AICC2023) has been published104, focused on improving the chronology in older ice sections. While this new chronology reduces age uncertainties over the full 800,000 years (Supplementary Table 3), the 60–100 ka section is sparse in age ties, with the new chronology strongly influenced by a total air content age constraint at 95 ka. Additional CH4 ties that exist across the 60–100 ka interval are more consistent in age with AICC2012 but do not appear to have a strong influence with the new age model. We therefore continue to use the AICC2012 throughout this work and supply AICC2023 peak ages in Supplementary Table 3.

Ice core sampling

For this study, Greenland ice cores NEEM (depth range 2049.02–2049.85 m) and NGRIP (depth range 2618.92–2619.50 m), and Antarctic ice core EDC (depth range 1140.40–1140.70 m) were sampled. We sampled across the identified volcanic sulfate peak at 1–3 cm resolution and approximately 4–6 cm2 cross-section for both sulfate concentration and tephra analysis, with additional background samples at lower resolution pre- and post-dating the sulfate peak. At this depth, 1 cm is approximately equal to 1 year (Supplementary Table 4 for details).

The sulfate concentration of each ice meltwater sample of NEEM, NGRIP, and EDC was measured in duplicate by ion chromatography using a Metrohm 980 Compact IC Flex at the University of St Andrews.

Tephra preparation and analysis conditions

Ice-core tephra samples were prepared following established procedure105, by mounting on disks of Epothin2 epoxy resin. Scanning Electron Microscope Electron Dispersive Spectrometry (SEM-EDS) was used to screen for tephra with a 1–5 nA current and 15 kV accelerating voltage setup. Mounts with multiple tephra shards suitable for analysis were found from NEEM and EDC, but not from NGRIP samples.

Samples containing tephra were polished using 6 μm, 3 μm, and 1 μm diamond suspension pastes, and 0.3 μm aluminum oxide slurry for variable times depending on the size and sparsity of shards. Tephra from sediment core V19-30, and proximal LCY ash samples (fall, ignimbrite, and surge phases) were prepared in a similar way, by mounting on adhesive tape before fixing in epoxy resin disks and polishing using 6 μm–1 μm diamond suspension pastes and 0.3 μm aluminum oxide slurry.

Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) took place at the University of St Andrews using a JEOL JXA-iSP100 electron probe microanalyzer. During analysis, shards of 20 μm or larger that were found as part of a large (n = 30) population in NEEM at depth 2049.27–2049.24 m, and in NEEM background sample 2049.65–2049.85 m were measured for major oxides with conditions of 5 nA current, 10 μm or 5 μm beam diameter and 15 kV accelerating voltage. For all of the remaining shards with measurable glass areas <5 μm identified in EDC and other NEEM samples, current and beam diameter were reduced to 1 nA and 3 μm. Peak counting times of 20 or 30 s were used apart from Na where counting time was between 10 and 7 s, with background counting time approximately half of the peak time. Lipari obsidian ID3506 (rhyolite), StHs6-80G (andesite/dacite), and ML3B (basalt)106,107 were used to monitor accuracy and precision. Secondary standards showed no evidence of Na migration under these conditions, and all oxide mean totals are within 2σ of accepted values. Data from EPMA sessions can be found in Supplementary Data 2.

Trace element analysis by Laser Ablation – Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) and Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) has been used in recent tephrochronology studies to support major and minor element correlations55,56,108,109,110. However, these studies require beam diameters of ≥10 μm for LA-ICP-MS and ≥5 μm for SIMS for data of sufficient quality to strengthen correlations and were therefore not appropriate for our tephra with available glass areas ≤5 μm (Supplementary Fig. 9). Due to beam size and data quality limitations, trace element analysis has only been used for ice core tephra of suitable size originating from high-latitude sources proximal to the ice sheets55,56,110. Distal correlations and ice core tephra identified from large magnitude, tropical source eruptions rely on major and minor element data from high-quality EPMA due to smaller glass areas and sparse shard numbers available37,38,77.

In some cases, a glass surface 3 μm in diameter did not exist for EPMA due to extremely small or irregularly shaped shards. In these cases, we used a beam diameter larger than the tephra shard, with a portion of the beam area overlapping onto the surrounding epoxy resin105,111. Previous work105 has demonstrated that this method is successful with 20 μm, 10 nA beam, with all elements statistically indistinguishable from analysis with no overlap at one standard deviation. We initially used this method on INTAV standards Old Crow and Mount Edziza (Sheep Track) that had been prepared and polished by an identical method to our ice core samples (above), reducing the beam current and size to 1 nA and 3 μm. Between 70 and 95% of the beam area was positioned on the shard during each analysis, producing totals ranging 63–98%. To facilitate comparisons between all EPMA data, all results were normalized to 100% on an anhydrous basis. The Epothin2 epoxy resin showed no interference with the major oxides measured in this study in agreement with108.

Using 3 μm, 1 nA beam conditions, our findings compare well with the 20 μm, 10 nA beam used by ref. 105 and demonstrate a high degree of accuracy but a decrease in precision when overlapping is used. The INTAV standards measured using both overlapping and non-overlapping methods are within 2σ of recommended values, with higher P2O5 throughout analysis likely a feature of normalization to 100% from low totals. We observed a noticeable decrease in precision with increasing beam overlap on the epoxy and found optimal results when >80% of the beam area was positioned on the shard. We therefore ensured at least 80% of the beam was on the shard for analysis of ice core samples.

Ice-core tephra analyses with totals ≥63% were cautiously included in interpretation, following the demonstration by the beam overlap method that accuracy was robust enough to make conclusions after normalization to 100%, with a compromise in precision. Low total analyses (~60%) have previously been used to correlate tropical tephra found in polar cores (e.g., Samalas 1257 CE37). Each session where ice-core tephra was analyzed using 3 μm beam conditions, we made replicate measurements of Old Crow tephra that had been prepared identically to the ice-core samples to understand the precision of this method as recommended111.

In addition, five shards in NEEM (2049.65–2049.85 m) which belong to an eruption of Grimsvötn, Iceland, that were analyzed using this 3 μm beam size, including two using the resin-beam overlap method. These are indistinguishable from two tephra shards analyzed using larger beam sizes in this study, and tephra previously identified from this eruption in NGRIP55 (Supplementary Fig. 4), demonstrating the success of this method in correlating ice-core tephra.

The accuracy of our results from both INTAV standards and the successful correlation of ice—core tephra demonstrate that our method is suitable for use on extremely fine-grain tephra shards. By preparing and analyzing INTAV standards in an identical way to our ice-core samples, we have a good understanding of the uncertainty associated with each ice-core tephra analysis performed and present this uncertainty with analyses completed.

Tephra correlation to volcanic sources

Major and minor oxides of tephra analyzed in this work were initially compared to results of previous studies that have identified shard populations in Greenland ice during the time period covered by our samples, with two correlations found. The first (as discussed above) is a basaltic group (n = 10) in background sample NEEM at depth 2049.65–2069.85 m, which correlates with an eruption of Grímsvötn reported in NGRIP core at 2620.05 m55 (Supplementary Fig. 4) creating a new tie between NGRIP and NEEM. The second trachydacitic population (n = 30) we analyzed at depth 2049.24–2049.27 m in the NEEM core is the same horizon identified as Eastern Aleutian Arc (EAA) in origin, also found in the NEEM core in a 15 cm section at depth 2049.15–2049.30 m56 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Our analysis at high-temporal resolution therefore allows us to improve the depth precision of this eruption. Our sampled section from the NGRIP core does not extend to the depth in which the Grimsvötn population was previously identified, explaining its absence in our analysis of the NGRIP core. In Antarctica, the phonolitic shard population (n = 5) found in EDC at depth 1140.59–1140.61 m geochemically resembles older Marie Byrd Land eruptions of Mount Berlin which are found as marker horizons across deep east Antarctic ice cores54 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The LaMEVE/Vogripa database52,53 provides a list of eruptions within the age uncertainty of the ice core peak at 79.5 ka (Supplementary Table 5). Where available, glass compositional data was found for the eruptions listed. All ice-core tephra deposited prior to or during the deposition of the largest sulfate aerosol peak was compared to the available geochemistry to determine if there were any correlations (Supplementary Fig. 3). This comparison also ruled out any alternative known source correlations for the LCY matches.

As noted previously, the origin of the single LCY-correlating shard deposited in the NEEM core ~16 years prior to the correlating population at the sulfate peak (Figs. 2 and 3) is possibly a smaller, unknown eruption. Alternatively, it is worth noting the subtle differences in geochemistry between this single shard and the later LCY population mirror changes in geochemistry through the stratigraphy of proximal LCY deposits, with more FeO variation and lower SiO2 in later ignimbrite and surge phases than the initial ash fall20 (Supplementary Fig. 10). This scenario would require a hiatus between at least 2 eruptive phases of LCY, something that is hypothesized at other large-volume eruptions112,113, but not visible in proximal or marine deposits of LCY20,114.

Volcanic sulfate deposition

Total sulfate deposition to each ice core is calculated using the available high-resolution ice-core sulfate (and sulfur) data, correcting for (1) non-volcanic background sulfate contributions, (2) changes in ice accumulation rates, (3) layer thinning with depth43,44,59,61. By considering multiple ice cores we provide a representative estimate for volcanic sulfate deposition, accounting for local scale variability in sulfate deposition and preservation at ice core sites68,115.

The detection of volcanic eruptions and the quantification of volcanic sulfuric acid deposition rates by means of sulfate concentrations in polar ice is an established method in paleoclimate research116,117,118,119 which increasingly is based on larger arrays of synchronized ice-core records58,59,120. Sporadic volcanic sulfate deposition at polar ice-core sites is superimposed on background variations of sulfate from other sources (e.g., from mineral dust, marine biogenic, or sea salt emissions). To distinguish volcanic sulfate from the non-volcanic sources we quantified the background and its variability using established outlier detection methods (based on a running median) described in detail elsewhere103,115,121,122. The specific detection parameters (filter lengths, detection thresholds, integration window lengths) are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. We slightly expanded the volcano detection to time periods before and after the LCY candidate signals, to improve the estimates of representative non-volcanic background sulfate concentrations for this time period. Because of the exceptionally large sulfate concentrations for the corresponding LCY ice-core signals, the volcanic sulfate deposition estimates are largely insensitive to the choice of the detection parameters. Centered around our candidate LCY event we detected large volcanic eruptions in the four continuous ice-core records (NGRIP, GISP2, EDML, and EDC) and in the shorter available ice-core sections (NGRIP, NEEM) used for tephra analyses (Supplementary Fig. 7). We used thinning-corrected accumulation rates to quantify sulfate mass deposition rates (or “fluxes”) at the five ice-core sites (Supplementary Table 4; for a detailed description of the methodology see ref. 59). Time-integrated sulfate deposition for LCY varies between 205 and 440 kg km−2 across the ice cores reflecting differences in the spatial variability of deposition (largely controlled by different snow accumulation rates) and variations in data-resolution and uncertainties in our estimates of accumulation rates, thinning functions and non-volcanic background estimation.

Stratospheric sulfur injection

We stacked and averaged the time-integrated cumulative volcanic sulfate deposition from the LCY candidate event in both Greenland and Antarctica to derive a mean Greenland and mean Antarctica composite record. Both records from Antarctica (EDML, EDC) are from low-accumulation ice-core sites which have consistently lower volcanic sulfate deposition rates than Antarctica overall103. Therefore, we linearly scale the average deposition rates obtained from these two ice cores to the ice-sheet-wide volcanic deposition rates obtained from a comprehensive array of ice cores (named AVS2k103) for 49 common volcanic eruptions recorded during the past 2000 years (slope of the regression a = 1.2474, R2 = 0.89; N = 49). The slope is similar if only very large eruptions (>Tambora 1815) are used (a = 1.2402, R2 = 0.61; N = 6). For Greenland, we do not apply any correction of the Greenland ice-sheet mean, as the three records used are from the same three ice cores employed in the Common Era with comparable deposition rates of volcanic sulfate5,61. Finally, using previously published methodology61, we estimated volcanic stratospheric sulfur injection (VSSI, in Tg of sulfur) from the ice-sheet wide fluxes of volcanic sulfate from Greenland and Antarctica using transfer functions115 accounting for the spatial distribution of the volcanic sulfate burden over each hemisphere (See Supplementary Data 1).

The mass of sulfur injection to the stratosphere is calculated based on established methods61 using expression (1):

Where f G and f A are the scaled sulfate flux to Greenland and Antarctica, and 1.0 × 109 km2 is appropriate to use for transfer functions LG and LA to account for hemisphere spatial distribution of sulfate, as the eruptive source is from a tropical latitude58,61,115. The uncertainty associated is calculated using expression (2) also provided in61:

Where the random error of the transfer functions for Greenland and Antarctica are estimated from model simulations as \({\sigma }_{{L}^{G}}\) = 16% and \({\sigma }_{{L}^{A}}\) = 9%, and uncertainties in the composite ice sheet fluxes are \({\sigma }_{{f}^{G}}\) = 32 % for NEEM and NGRIP combination, and \({\sigma }_{{f}^{{A}}}\) = 26% for Antarctica before 1 CE61.

Data availability

Ice core sulfate concentration and deposition data for the eruption peak analyzed in this work are available at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.962785 for EDML, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.960984 for NGRIP, and https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.962783 for GISP2. EDC sulfate concentration data is available at https://doi.org/10.25921/kgv8-cn3584. EDC oxygen isotope data is available at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.939445123. NGRIP oxygen isotope data is available at https://www.iceandclimate.nbi.ku.dk/data8,81. V19-30 marine sediment core oxygen isotope record is available at https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.5221133. MD97-2151 marine sediment core benthic oxygen isotope record is available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2006.08.00535. All ice core sulfate data used to calculate VSSI and tephra geochemical data are available at https://doi.org/10.17630/62b68476-ca09-4011-9ad5-c9d44b09d6a8 or Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2, respectively.

References

Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000).

Cassidy, M. & Mani, L. Prepare now for big eruptions. Nature 608, 469–471 (2022).

Newhall, C. G. & Self, S. The volcanic explosivity index (VEI): an estimate of explosive magnitude for historical volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 1231–1238 (1982).

Büntgen, U. et al. Prominent role of volcanism in Common Era climate variability and human history. Dendrochronologia 64, 125757 (2020).

Sigl, M. et al. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–549 (2015).

Ridley, H. E. et al. Aerosol forcing of the position of the intertropical convergence zone since AD 1550. Nat. Geosci. 8, 195–200 (2015).

Haywood, J. M., Jones, A., Bellouin, N. & Stephenson, D. Asymmetric forcing from stratospheric aerosols impacts Sahelian rainfall. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 660–665 (2013).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 14–28 (2014).

Baldini, J. U. L., Brown, R. J. & McElwaine, J. N. Was millennial scale climate change during the Last Glacial triggered by explosive volcanism? Sci. Rep. 5, 17442 (2015).

Lohmann, J. & Svensson, A. Ice core evidence for major volcanic eruptions at the onset of Dansgaard–Oeschger warming events. Clim 18, 2021–2043 (2022).

Thornalley, D. J. R., Barker, S., Becker, J., Hall, I. R. & Knorr, G. Abrupt changes in deep Atlantic circulation during the transition to full glacial conditions. Paleoceanography 28, 253–262 (2013).

Barker, S. et al. Icebergs not the trigger for North Atlantic cold events. Nat. Lett. 520, 333–336 (2015).

Li, C. & Born, A. Coupled atmosphere-ice-ocean dynamics in Dansgaard-Oeschger events. Quat. Sci. Rev. 203, 1–20 (2019).

Menviel, L. C., Skinner, L. C., Tarasov, L. & Tzedakis, P. C. An ice–climate oscillatory framework for Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 677–693 (2020).

Zhong, Y. et al. Centennial-scale climate change from decadally-paced explosive volcanism: a coupled sea ice-ocean mechanism. Clim. Dyn. 37, 2373–2387 (2011).

Zanchettin, D. et al. Inter-hemispheric asymmetry in the sea-ice response to volcanic forcing simulated by MPI-ESM (COSMOS-Mill). Earth Syst. Dyn. 5, 223–242 (2014).

Mark, D. F. et al. High-precision 40Ar/39Ar dating of pleistocene tuffs and temporal anchoring of the Matuyama-Brunhes boundary. Quat. Geochronol. 39, 1–23 (2017).

Storey, M., Roberts, R. G. & Saidin, M. Astronomically calibrated 40Ar/39Ar age for the Toba supereruption and global synchronization of late quaternary records. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18684–18688 (2012).

Carolin, S. A. et al. Varied response of Western Pacific hydrology to climate forcings over the Last Glacial Period. Science 340, 1564–1566 (2013).

Cisneros de León, A. et al. A history of violence: magma incubation, timing and tephra distribution of the Los Chocoyos supereruption (Atitlán Caldera, Guatemala). J. Quat. Sci. 36, 169–179 (2021).

Drexler, J. W., Rose, W. I., Sparks, R. S. J. & Ledbetter, M. T. The Los Chocoyos Ash, Guatemala: a major stratigraphic marker in Middle America and in Three Ocean Basins. Quat. Res. 13, 327–345 (1980).

Paine, A. R., Wadsworth, F. B. & Baldini, J. U. L. Supereruption doublet at a climate transition. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 219 (2021).

Cisneros de León, A. et al. On synchronous supereruptions. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 827252 (2022).

Kutterolf, S. et al. Pacific offshore record of plinian arc volcanism in Central America: 1. Along-arc correlations. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q02S01 (2008).

Schindlbeck, J. C. et al. Miocene to Holocene Marine Tephrostratigraphy Offshore Northern Central America and Southern Mexico: pulsed activity of known volcanic complexes. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 4143–4173 (2018).

Kutterolf, S. et al. A 400-ka tephrochronological framework for Central America from Lake Petén Itzá (Guatemala) sediments. Quat. Sci. Rev. 150, 200–220 (2016).

Hahn, G. A., Rose, W. I. & Meyers, T. Geochemical correlation of genetically related rhyolitic ash-flow and air-fall ashes, central and western Guatemala and the equatorial Pacific. In Ash-Flow Tuffs., Vol. 180, (eds Chapin, C. E. & Elston, W. E.) 101–112 (Geological Society of America, 1979).

Pisias, N. G. et al. High resolution stratigraphic correlation of benthic oxygen isotopic records spanning the last 300,000 years. Mar. Geol. 56, 119–136 (1984).

Martinson, D. G. et al. Age dating and the orbital theory of the ice ages: development high-resolution 0 to 300,000-year chronostratigraphy. Quat. Res. 27, 1–29 (1987).

Lisiecki, L. E. & Raymo, M. E. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography 20, PA1003 (2005).

Thompson, W. G. & Goldstein, S. L. A radiometric calibration of the SPECMAP timescale. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 3207–3215 (2006).

Ninkovich, D. & Shackleton, N. J. Distribution, stratigraphic position and age of ash layer ‘L’, in the Panama Basin region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 27, 20–34 (1975).

Shackleton, N. J., Imbrie, J. & Hall, M. A. Oxygen and carbon isotope record of East Pacific core V19-30: implications for the formation of deep water in the late Pleistocene North Atlantic. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 65, 233–244 (1983).

Song, S. R. et al. Newly discovered eastern dispersal of the youngest Toba Tuff. Mar. Geol. 167, 303–312 (2000).

Wei, G. J., Huang, C. Y., Wang, C. C., Lee, M. Y. & Wei, K. Y. High-resolution benthic foraminifer δ13C records in the South China Sea during the last 150 ka. Mar. Geol. 232, 227–235 (2006).

Abbott, P. M. & Davies, S. M. Volcanism and the Greenland ice-cores: the tephra record. Earth Sci. Rev. 115, 173–191 (2012).

Narcisi, B., Petit, J. R., Delmonte, B., Batanova, V. & Savarino, J. Multiple sources for tephra from AD 1259 volcanic signal in Antarctic ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 210, 164–174 (2019).

Smith, V. C. et al. The magnitude and impact of the 431 CE Tierra Blanca Joven eruption of Ilopango, El Salvador. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26061–26068 (2020).

Zielinski, G. A. et al. Volcanic aerosol records and tephrochronology of the Summit, Greenland, ice cores. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 102, 26625–26640 (1997).

Veres, D. et al. The Antarctic ice core chronology (AICC2012): an optimized multi-parameter and multi-site dating approach for the last 120 thousand years. Clim. Past 9, 1733–1748 (2013).

Svensson, A. et al. Direct linking of Greenland and Antarctic ice cores at the Toba eruption (74 ka BP). Clim. Past 9, 749–766 (2013).

Crick, L. et al. New insights into the ∼ 74 ka Toba eruption from sulfur isotopes of polar ice cores. Clim. Past 17, 2119–2137 (2021).

Lin, J. et al. Bipolar ice-core records constrain possible dates and global radiative forcing following the ~ 74 ka Toba eruption. Quat. Sci. Rev. 312, 108162 (2023).

Wolff, E. W. et al. Frequency of large volcanic eruptions over the past 200,000 years. Clim. Past 19, 23–33 (2023).

Burke, A. et al. Stratospheric eruptions from tropical and extra-tropical volcanoes constrained using high-resolution sulfur isotopes in ice cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 521, 113–119 (2019).

Savarino, J., Romero, A., Cole-Dai, J., Bekki, S. & Thiemens, M. H. UV induced mass-independent sulfur isotope fractionation in stratospheric volcanic sulfate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2131 (2003).

Gautier, E. et al. 2600-years of stratospheric volcanism through sulfate isotopes. Nat. Commun. 10, 466 (2019).

Pearson, C. et al. Geochemical ice-core constraints on the timing and climatic impact of Aniakchak II (1628 BCE) and Thera (Minoan) volcanic eruptions. PNAS Nexus 1, 1–12 (2022).

Plunkett, G., Sigl, M., McConnell, J. R., Pilcher, J. R. & Chellman, N. J. The significance of volcanic ash in Greenland ice cores during the Common Era. Quat. Sci. Rev. 301, 107936 (2023).

Koffman, B. G. et al. Rapid transport of ash and sulfate from the 2011 Puyehue-Cordón Caulle (Chile) eruption to West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 8908–8920 (2017).

Plunkett, G. et al. No evidence for tephra in Greenland from the historic eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE: Implications for geochronology and paleoclimatology. Clim. Past 18, 45–65 (2022).

Crosweller, H. S. et al. Global database on large magnitude explosive volcanic eruptions (LaMEVE). J. Appl. Volcanol. 1, 4 (2012).

Brown, S. K. et al. Characterisation of the quaternary eruption record: analysis of the Large Magnitude Explosive Volcanic Eruptions (LaMEVE) database. J. Appl. Volcanol. 3, 5 (2014).

Narcisi, B., Petit, J. R. & Tiepolo, M. A volcanic marker (92 ka) for dating deep east Antarctic ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25, 2682–2687 (2006).

Abbott, P. M. et al. A detailed framework of Marine Isotope Stages 4 and 5 volcanic events recorded in two Greenland ice-cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 36, 59–77 (2012).

Bourne, A. J. et al. Underestimated risks of recurrent long-range ash dispersal from northern Pacific Arc volcanoes. Sci. Rep. 6, 29837 (2016).

Rougier, J., Sparks, R. S. J., Cashman, K. V. & Brown, S. K. The global magnitude–frequency relationship for large explosive volcanic eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 621–629 (2018).

Sigl, M., Toohey, M., McConnell, J. R., Cole-Dai, J. & Severi, M. Volcanic stratospheric sulfur injections and aerosol optical depth during the Holocene (past 11 500 years) from a bipolar ice-core array. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 3167–3196 (2022).

Lin, J. et al. Magnitude, frequency and climate forcing of global volcanism during the last glacial period as seen in Greenland and Antarctic ice cores (60-9 ka). Clim. Past 18, 485–506 (2022).

Palais, J. M., Germani, M. & Zielinski, G. A. Inter-hemispheric transport of volcanic ash from a 1259 A.D. volcanic eruption to the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 19, 801–804 (1992).

Toohey, M. & Sigl, M. Volcanic stratospheric sulfur injections and aerosol optical depth from 500 BCE to 1900 CE. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 809–831 (2017).

Flowers, R. M. et al. (U-Th)/He chronology: Part 2. Considerations for evaluating, integrating, and interpreting conventional individual aliquot data. GSA Bull. 135, 137–161 (2022).

Mark, D. F. et al. A high-precision 40Ar/39Ar age for the Young Toba Tuff and dating of ultra-distal tephra: forcing of quaternary climate and implications for hominin occupation of India. Quat. Geochronol. 21, 90–103 (2014).

Brenna, H., Kutterolf, S., Mills, M. J. & Krüger, K. The potential impacts of a sulfur- and halogen-rich supereruption such as Los Chocoyos on the atmosphere and climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 6521–6539 (2020).

Metzner, D. et al. Radiative forcing and climate impact resulting from SO2 injections based on a 200,000-year record of Plinian eruptions along the Central American Volcanic Arc. Int. J. Earth Sci. 103, 2063–2079 (2014).

Shinohara, H. Excess degassing from volcanoes and its role on eruptive and intrusive activity. Rev. Geophys. 46, RG4005 (2008).

Toohey, M., Krüger, K. & Timmreck, C. Volcanic sulfate deposition to Greenland and Antarctica: a modeling sensitivity study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 4788–4800 (2013).

Gautier, E., Savarino, J., Erbland, J., Lanciki, A. & Possenti, P. Variability of sulfate signal in ice core records based on five replicate cores. Clim. Past 12, 103–113 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Persisting volcanic ash particles impact stratospheric SO2 lifetime and aerosol optical properties. Nat. Commun. 11, 4526 (2020).

Pinto, J. P., Turco, R. P. & Toon, O. B. Self-limiting physical and chemical effects in volcanic eruption clouds. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 11165–11174 (1989).

Timmreck, C. et al. Aerosol size confines climate response to volcanic super-eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L24705 (2010).

Deplazes, G. et al. Links between tropical rainfall and North Atlantic climate during the last glacial period. Nat. Geosci. 6, 213–217 (2013).

Corrick, E. C. et al. Synchronous timing of abrupt climate changes during the last glacial period. Science 369, 963–969 (2020).

Zanchettin, D. et al. Background conditions influence the decadal climate response to strong volcanic eruptions. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 4090–4106 (2013).

Raible, C. C. et al. Tambora 1815 as a test case for high impact volcanic eruptions: Earth system effects. Clim. Chang. 7, 569–589 (2016).

van Dijk, E. J. C., Jungclaus, J., Sigl, M., Timmreck, C. & Krüger, K. High-frequency climate forcing causes prolonged cold periods in the Holocene. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 242 (2024).

Dunbar, N. W. et al. New Zealand supereruption provides time marker for the Last Glacial Maximum in Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 7, 12238 (2017).

Svensson, A. et al. Bipolar volcanic synchronization of abrupt climate change in Greenland and Antarctic ice cores during the last glacial period. Clim. Past 16, 1565–1580 (2020).

Wilson, C. J. N. et al. No single model for supersized eruptions and their magma bodies. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 610–627 (2021).

Huang, C. Y., Wang, C. C. & Zhao, M. High-resolution carbonate stratigraphy of IMAGES core MD972151 from South China Sea. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 10, 225–238 (1999).

Seierstad, I. K. et al. Consistently dated records from the Greenland GRIP, GISP2 and NGRIP ice cores for the past 104 ka reveal regional millennial-scale δ18O gradients with possible Heinrich event imprint. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 29–46 (2014).

North Greenland Ice Core Project Members*. High-resolution record of Northern Hemisphere climate extending into the last interglacial period. Nature 431, 147–151 (2004).

EPICA Community Members*. Eight glacial cycles from an Antarctic ice core. Nature 429, 623–628 (2004).

Severi, M., Udisti, R., Castellano, E. & Wolff, E. W. EPICA Dome C 203,000 year high-resolution FIC sulfate data. https://doi.org/10.25921/kgv8-cn35 (NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, 2020).

EPICA Community Members* One-to-one coupling of glacial climate variability in Greenland and Antarctica. Nat. Lett. 444, 195–198 (2006).

Bigler, M. et al. Optimization of high-resolution continuous flow analysis for transient climate signals in ice cores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4483–4489 (2011).

Bigler, M. et al. Sulphate record from a northeast Greenland ice core over the last 1200 years based on continuous flow analysis. Ann. Glaciol. 35, 250–256 (2002).

Abbott, P. M. et al. Volcanic climate forcing preceding the inception of the Younger Dryas: implications for tracing the Laacher See eruption. Quat. Sci. Rev. 274, 107260 (2021).

Bourne, A. J. et al. A tephra lattice for Greenland and a reconstruction of volcanic events spanning 25-45 ka b2k. Quat. Sci. Rev. 118, 122–141 (2015).

Davies, S. M. et al. Tracing volcanic events in the NGRIP ice-core and synchronising North Atlantic marine records during the last glacial period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 294, 69–79 (2010).

Mortensen, A. K., Bigler, M., Grönvold, K., Steffensen, J. P. & Johnsen, S. J. Volcanic ash layers from the last glacial termination in the NGRIP ice core. J. Quat. Sci. 20, 209–219 (2005).

Reinig, F. et al. Precise date for the Laacher See eruption synchronizes the Younger Dryas. Nature 595, 66–69 (2021).

Severi, M. et al. Synchronisation of the EDML and EDC ice cores for the last 52 kyr by volcanic signature matching. Clim. Past 3, 367–374 (2007).

Traversi, R. et al. High-resolution fast ion chromatography (FIC) measurements of chloride, nitrate and sulphate along the EPICA Dome C ice core. Ann. Glaciol. 35, 291–298 (2002).

Röthlisberger, R. et al. Technique for continuous high-resolution analysis of trace substances in firn and ice cores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 338–342 (2000).

Buizert, C. et al. Abrupt ice-age shifts in southern westerly winds and Antarctic climate forced from the north. Nat. Lett. 563, 681–685 (2018).

Fujita, S., Parrenin, F., Severi, M., Motoyama, H. & Wolff, E. W. Volcanic synchronization of Dome Fuji and Dome C Antarctic deep ice cores over the past 216 kyr. Clim. Past 11, 1395–1416 (2015).

Parrenin, F. et al. Volcanic synchronisation between the EPICA Dome C and Vostok ice cores (Antarctica) 0-145 kyr BP. Clim. Past 8, 1031–1045 (2012).

Severi, M., Udisti, R., Becagli, S., Stenni, B. & Traversi, R. Volcanic synchronisation of the EPICA-DC and TALDICE ice cores for the last 42 kyr BP. Clim. Past 8, 509–517 (2012).

Castellano, E. et al. Volcanic eruption frequency over the last 45 ky as recorded in Epica-Dome C ice core (East Antarctica) and its relationship with climatic changes. Glob. Planet. Chang. 42, 195–205 (2004).

McConnell, J. R. et al. Synchronous volcanic eruptions and abrupt climate change ~17.7 ka plausibly linked by stratospheric ozone depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10035–10040 (2017).

Rasmussen, S. O. et al. A first chronology for the North Greenland Eemian Ice Drilling (NEEM) ice core. Clim. Past 9, 2713–2730 (2013).

Sigl, M. et al. Insights from Antarctica on volcanic forcing during the Common Era. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 693–697 (2014).

Bouchet, M. et al. The Antarctic Ice Core Chronology 2023 (AICC2023) chronological framework and associated timescale for the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) Dome C ice core. Clim. Past 19, 2257–2286 (2023).

Iverson, N. A., Kalteyer, D., Dunbar, N. W., Kurbatov, A. & Yates, M. Advancements and best practices for analysis and correlation of tephra and cryptotephra in ice. Quat. Geochronol. 40, 45–55 (2017).

Jochum, K. P. et al. MPI-DING reference glasses for in situ microanalysis: new reference values for element concentrations and isotope ratios. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, Q02008 (2006).

Kuehn, S. C., Froese, D. G., Shane, P. A. R. & Participants, I. I. The INTAV intercomparison of electron-beam microanalysis of glass by tephrochronology laboratories: results and recommendations. Quat. Int. 246, 19–47 (2011).

Portnyagin, M. V. et al. TephraKam: geochemical database of glass compositions in tephra and welded tuffs from the Kamchatka volcanic arc (northwestern Pacific). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 469–486 (2020).

Satow, C. et al. A new contribution to the late quaternary tephrostratigraphy of the Mediterranean: Aegean Sea core LC21. Quat. Sci. Rev. 117, 96–112 (2015).

Cook, E. et al. Volcanism and the Greenland ice cores: a new tephrochronological framework for the last glacial-interglacial transition (LGIT) based on cryptotephra deposits in three ice cores. Quat. Sci. Rev. 292, 107596 (2022).

Innes, H. M., Hutchison, W. & Burke, A. Geochemical analysis of extremely fine-grained cryptotephra: New developments and recommended practices. Quat. Geochron. 83, 101553 (2024).

Swallow, E. J., Wilson, C. J. N., Charlier, B. L. A. & Gamble, J. A. The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, Yellowstone: evacuation of multiple magmatic systems in a complex episodic eruption. J. Petrol. 60, 1371–1426 (2019).

Pearce, N. J. G., Westgate, J. A., Gualda, G. A. R., Gatti, E. & Muhammad, R. F. Tephra glass chemistry provides storage and discharge details of five magma reservoirs which fed the 75 ka Youngest Toba Tuff eruption, northern Sumatra. J. Quat. Sci. 35, 256–271 (2020).

Kutterolf, S., Freundt, A. & Peréz, W. Pacific offshore record of plinian arc volcanism in Central America: 2. Tephra volumes and erupted masses. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q02S02 (2008).

Gao, C., Oman, L., Robock, A. & Stenchikov, G. L. Atmospheric volcanic loading derived from bipolar ice cores: Accounting for the spatial distribution of volcanic deposition. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D09109 (2007).

Hammer, C. U., Clausen, H. B. & Dansgaard, W. Greenland ice sheet evidence of post-glacial volcanism and its climatic impact. Nature 288, 230–235 (1980).

Hammer, C. U., Clausen, H. B. & Langway, C. C. 50,000 years of recorded global volcanism. Clim. Chang. 35, 1–15 (1997).

Zielinski, G. A. Stratospheric loading and optical depth estimates of explosive volcanism over the last 2100 years derived from the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 ice core. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 20937–20955 (1995).

Zielinski, G. A., Mayewski, P. A., Meeker, L. D., Whitlow, S. & Twickler, M. S. A 110,000-Yr record of explosive volcanism from the GISP2 (Greenland) ice core. Quat. Res. 45, 109–118 (1996).

Gao, C., Robock, A. & Ammann, C. Volcanic forcing of climate over the past 1500 years: an improved ice core-based index for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D23111 (2008).

Cole-Dai, J. Volcanoes and climate. Clim. Chang. 1, 824–839 (2010).

Traufetter, F., Oerter, H., Fischer, H., Weller, R. & Miller, H. Spatio-temporal variability in volcanic sulphate deposition over the past 2 kyr in snow pits and firn cores from Amundsenisen, Antarctica. J. Glaciol. 50, 137–146 (2004).

Gkinis, V. et al. Oxygen-18 isotope ratios from the EPICA Dome C ice core at 11 cm resolution. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.939445 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by IAPETUS2 NERC Doctoral Training Program Studentship (HI), UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship MR/S-33505/1 (WH), ERC Horizon 2020 grant 820047 (MSi and PMA), Leverhulme Trust grant RPG-2015-246 and Fellowship EM-2018-050/4 (RSJS), Leverhulme Trust Prize PLP-2021-167 (AB). The EPMA facilities at the University of St Andrews are supported by the EPSRC Light Element Analysis Facility Grant EP/T019298/1 and the EPSRC Strategic Equipment Resource Grant EP/R023751/1. We thank the National Science Foundation-Ice Core Facility (NSF-2041950). M. Twickler and G. Hargreaves for providing access to GISP2 samples, ice-core sampling assistance, and curation; we thank the NGRIP and NEEM communities, J.P. Steffensen and I. Koldtoft for providing access to NGRIP and NEEM samples, and we thank I. Gabriel for ice-core sampling assistance. This research contributes to the NGRIP and NEEM ice-core projects, which are curated by Physics of Ice, Climate and Earth (PICE), Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen (KU). These projects were supported by funding agencies in Denmark (SNF, FI), Canada (NRCan/GSC), China (CAS), Belgium (FNRS-CFB, FWO), France (IPEV, IFRTP, INSU/CNRS, CEA and ANR), Germany (AWI), Iceland (RannIs), Japan (MEXT, NIPR), South Korea (KOPRI), Sweden (SPRS, VR), Switzerland (SNF), The Netherlands (NWO/ALW), United Kingdom (NERC) and the United States of America (NSF, Office of Polar Programs). This work is a contribution to the “European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica” (EPICA), a joint European Science Foundation–European Commission scientific program funded by the European Union and by national contributions from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Sediment core sample material used in this project was provided by the Lamont-Doherty Core Repository of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. We thank K. Krüger for discussions. This work benefitted greatly from the authors’ participation in the Past Global Changes (PAGES) Volcanic Impacts on Climate and Society (VICS) working group, which received support from the Swiss Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank 3 reviewers who provided valuable insights and suggestions which greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.I., W.H., M.Si., and A.B. contributed to writing the original manuscript. H.I. performed tephra preparation and geochemical analysis. M.Si. performed sulfur injection calculations. S.M.D., W.H., P.M.A. advised for tephra preparation, analysis methods, and data interpretation. M.Se., J.R.M., N.C., and M.B. provided ice core glaciochemical records. E.W.W., S.K., A.S., and L.C. provided ice core and proximal tephra samples for analysis. A.B., M.Si., P.M.A., R.S.J.S., and J.W.B.R. conceptualized the project. Funding for the project was provided by H.I., W.H., M.Si., R.S.J.S., and A.B. A.B., W.H. and J.W.B.R. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the reviewing, editing, and improvement of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Alice Paine, Brian Jicha, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Innes, H.M., Hutchison, W., Sigl, M. et al. Ice core evidence for the Los Chocoyos supereruption disputes millennial-scale climate impact. Commun Earth Environ 6, 137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02095-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02095-6