Abstract

The Mw 8.3 deep-focus earthquake beneath the Okhotsk Sea in 2013 provides an opportunity to study the source mechanism with regard to the specific geometry of the slab in the hypocentral region. It is also an opportunity to observe the impact of such a major event on the mechanical functioning of the subduction. Here we investigated the intricate rupture processes of the earthquake through back-projection using global stations. The earthquake can be divided into two stages, each consisting of multiple sub-events. Our teleseismic back-projection results suggest that the first stage of rupture occurred on multiple sub-horizontal planes and propagated to greater depths during the second stage. The main part of the rupture is consistent with transformational faulting within the metastable olivine wedge. The complex rupture process during the great earthquake can be put into perspective with the variations in the rate of plunge observed before and after the earthquake. While the earthquake was facilitated by a transient plunge a month before, it allowed a form of asperity to disappear through thermal runaway on a dipping plane and consequently led to an acceleration in the rate of subduction over the last 10 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subduction zones are highly seismically active regions, with the majority of earthquakes occurring at depths shallower than 70 km; as the depth increases, the number of earthquakes gradually decreases1. On 24 May 2013, at approximately 600 km beneath the Okhotsk Sea, a Mw 8.3 earthquake occurred at 05:44:48 UTC2. This earthquake was the largest deep-focus earthquake recorded to date. This is therefore a major event that it is important to consider in terms of its role in subduction mechanics. It occurred at the northwestern end of the Pacific Plate, where the Pacific Plate subducts beneath the Okhotsk Plate along the Kuril–Kamchatka subduction zone. Deep-focus earthquakes and shallow earthquakes exhibit distinct source mechanisms. Three widely accepted mechanisms have been proposed to explain deep-focus earthquakes3: transformational faulting, dehydration embrittlement, and thermal runaway. At the temperature and pressure conditions of the mantle transition zone, polymorphic olivine undergoes a phase change to spinel, and the shear instability resulting from this phase change is referred to as transformational faulting4. This mechanism can effectively explain the concentration of deep-focus earthquakes in the mantle transition zone. Dehydration embrittlement is more commonly invoked to explain the origins of intermediate-depth earthquakes; as the slab descends into the mantle, water gradually exudes from minerals in a high-temperature and high-pressure environment4. Thermal runaway results from the positive feedback between shear strain heating and rock softening3. Shear strain within the subducting slab leads to an increase in temperature, which reduces the rock viscosity; this decreased viscosity promotes deformation, and deformation continues to generate heat, thus forming a positive feedback loop5. Studies on the source mechanisms of the Okhotsk earthquake have involved techniques such as back-projection, source inversion, and directivity analysis. However, no consensus has been reached regarding the process(es) underlying the rupture among the three mechanisms mentioned above6,7,8,9,10. Previous back-projection imaging suggests that the earthquake ruptured on multiple sub-horizontal planes7,10,11, whereas multiphase and multiple-point source inversion has suggested a nearly vertical cascading rupture6.

The precise location of earthquakes is a crucial constraint on the slab geometry12. Deep-focus earthquakes also provide opportunities for investigating deep slab deformation and velocity structures. For instance, the 2018 Fiji doublet earthquake showed that the relic Fiji slab overlies the Tonga slab13. The Bonin earthquake of 2015, which reached depths of 680 km, suggests that the slab is folded at the 660 km discontinuity or has penetrated the lower mantle12,13,14,15,16. Through waveform inversion of earthquakes on both sides of the trench, Zhan et al.17 inferred that the P-wave velocity of the Okhotsk subducting slab was 5% higher than the background velocity. More recently, Chen et al.18 used a waveform modeling approach to analyze the high-frequency (up to 0.8 Hz) teleseismic records of the Okhotsk Mw 8.3 earthquake. They discovered a small-scale ultra-low P-wave velocity anomaly beneath the Pacific plate at the 660 km discontinuity. The buoyancy generated by the highly meltable volatiles of the abnormal body squeezes the plate, and the huge pressure triggers thermal runaway.

Back-projection is an array-based source imaging method that typically requires only teleseismic P-waveforms. It was first developed and used to study the Mw 9.2 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake19,20. Back-projection relies on limited assumptions and allows for a detailed examination of complex ruptures, such as the rupture velocity and fault dimensions20. Various modifications have been made to improve the accuracy of back-projection images21,22,23,24,25,26. In this study, we extended the multi-array method26,27,28,29 using globally distributed stations.

By re-examining teleseismic data recorded during the Mw 8.3 Okhotsk 2013 deep-focus earthquake, we analyzed the kinematics of the rupture. For this purpose, global stations were employed to perform three-dimensional back-projection, and the temporal evolution was analyzed to present a 4D perspective. Back-projection imaging reveals a widespread distribution of sub-events during the rupture process. Furthermore, by integrating rheological and thermodynamic models, we inferred that the slab folded once at a depth of approximately 600 km. The earthquake occurred mainly within the metastable olivine wedge (MOW) of the bending slab, with faults induced by phase transformation initially propagating nearly horizontally, then transitioning to a near-vertical downward propagation, potentially triggering shear melting.

Results

Depth versus time amplitude matrix

Our methodology utilized global seismic stations (Fig. 1a) to enhance azimuthal coverage, and spatial resolution was improved through deconvolution. We consider two frequency bands, HF1 (0.5–2 Hz) and HF2 (0.33–1 Hz). Initially, we present the Depth-only versus Time Amplitude matrices from the back-projection (hereinafter referred to as the DTA matrix). From the DTA plots (Fig. 2), the mainshock can be decomposed into several well-separated sub-events, that form the entire earthquake process. To test the ability of global array 4D back-projection to resolve multiple sub-events at short intervals, we conducted bootstrap tests and a back-projection test with regional/local arrays only.

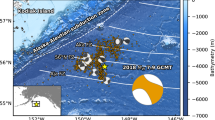

a Seismic stations used for the mainshock back-projection. Red and blue stations correspond to positive and negative polarities, respectively. Their size corresponds to correlation coefficients from 0.7 to 1. b The light blue cube is the back-projection target. The grey contours denote the Slab model 2.012. The red point indicates the mainshock hypocentre. c Triangulation of the stations; one colour is one group. The array response function at 0.5 Hz for global stations in the Okhotsk back-projection target region. d Depth slice with longitude at 153°E; e horizontal slice at a depth of 600 km; f depth slice with latitude at 55°N.

a Normalized energy curve of HF1; b Normalised energy curve of HF2; c DTA of HF1; d DTA of HF2. Isosurfaces at a threshold of 0.25 at each moment of the back-projection energy at HF1 (e) and HF2 (f). S1 and S2 denote stages 1 and 2. The value of the contour line is 0.25. The gray contours are the isosurfaces of the plate model 2.012, the light pink surfaces are the isosurfaces of the tomography model32 with dVp/Vp = 1%, and the red circles are the Okhotsk earthquake catalog33.

We conducted two types of bootstrap tests to evaluate the stability of global array back-projection. Test 1 examined the impact of station coverage or the number of stations. For this test, we randomly selected 70%, 80%, and 90% of the subarrays to perform back-projection calculations30. Test 2 assessed the effect of subarray weights by randomly assigning weights ranging from 0.1 to 1 to the subarrays29,31. Both tests were conducted using a grid spacing of 0.1°N × 0.1°E × 10 km. For each test, we performed 10 iterations and averaged the results. Comparing the DTA matrices obtained from these tests with the complete initial DTA matrix, we observed minimal differences (Supplementary Fig. 1). Whether subarrays were randomly excluded or subarray weights were varied, the back-projection results remained highly stable. These tests underscore the importance of global seismic array coverage. As long as the seismic data coverage is sufficiently comprehensive, randomly excluding a certain proportion of subarrays or altering the weights of some subarrays does not significantly affect the final back-projection results.

The results of the back-projection of the North American and European arrays are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. At HF1, four sub-events can be distinguished as local maxima in the DTA plots of both the American and European arrays; however, the energy of each sub-event is significantly different. In HF2, the American array is capable of discerning only three sub-events because the first two sub-events observed in HF1 coalesce into one event. The European array can distinguish four sub-events. In addition, good depth resolution cannot be obtained with a single regional array, which also makes it impossible for them to distinguish simultaneous sub-events at different depths, which emphasizes the importance of global array coverage.

Both tests demonstrate that global array 4D back-projection can resolve multiple earthquake sub-events and depth variations during the mainshock sequence.

The 3D distribution of multiple sub-events in back-projection imaging

Isosurfaces are drawn at a threshold of 0.25 at each moment after normalization as a proxy for the energy distribution of the earthquake at that moment, as shown in Fig. 2e, f. Compared to back-projection maps, isosurfaces provide a clearer representation of the earthquake energy distribution in 3D space (see Supplementary Movies 1, 2). We divide the mainshock into two stages based on the energy distribution in DTA and the location and propagation direction determined by back-projection. Each stage contains multiple sub-events and sub-events with similar depths often occur simultaneously. Therefore, sub-event classification cannot rely solely on energy clusters in the DTA but also requires consideration of the imaging in the 3D back-projection. In fact, it is possible to further divide into 4 stages according to the energy changes (Supplementary Fig. 3). The fixed threshold misses weak events in the early time of the earthquake. However, the location of the earthquake did not change significantly in the first few seconds (Supplementary Fig. 4), which had no impact on subsequent analysis.

Here, we provide an overview of back-projection kinematics and demonstrate the distance some of the sub-events extend from the slab model. Given the large number of sub-events identified in the two frequency bands (Supplementary Fig. 3), we focus on the earthquake kinematics across different stages. During the first stage, the earthquake first propagated along the slab strike in a north-easterly direction, stopping at the edge of the slab (Fig. 3b). Based on the DTA energy distribution and back-projection maps, HF1 revealed five sub-events in NE propagation, while HF2 identified three sub-events. Notably, HF1 showed two simultaneous sub-events at approximately 586 km depth between 3 and 9 s (Supplementary Fig. 6). For the NE propagation, HF2 exhibited limited radiation with a rupture propagation speed of about 1.8 km/s, whereas HF1 almost reached the slab edge with a rupture velocity of approximately 3.5 km/s (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Subsequently, the earthquake rupture occurred to the south. HF1 recorded two sub-events, while HF2 observed four sub-events, including three simultaneous sub-events at approximately 580 km depth between 13 and 16 s (Supplementary Fig. 7). HF1 propagated southward at a speed of approximately 2.7 km/s, while HF2 reached as high as 5.3 km/s (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Stages 1 was primarily confined to the 580–600 km depth range, with a few deeper sub-events detected in HF1. In general, it shows the propagation along the strike of the slab in the sub-horizontal plane, and the high frequency is more north-east (Supplementary Fig. 4), which Meng et al. 7 also reported.

a Seismicity in Okhotsk. Red line AA’ and BB’ represent the position of the cross-section in (c) and (d). The colored contours are projections of the back-projected normalized energy at a threshold of 0.25. The grey and white dots (50 km away from line AA’ or line BB’) are from Kamchatka catalog33. The light blue contours are slab model 2.012. The thick blue line is the plate boundary70. b Zoom of (a). Blue arrows indicate the direction of rupture propagation, and ☉ denotes vertical downward propagation. c, d Cross-section view of Okhotsk along line AA’ and line BB’ in (a). The white dots are earthquakes 50 km from line AA’ or line BB’. The colored contours are projections of the back-projected normalized energy stage 1 and stage 2 on the cross-section AA’ and BB’, respectively. The basemap is the tomography model32. The dark red line is the contour of dVp/Vp = 1%. The brown dotted lines are the modified slab model boundary (The white hollow part below indicates that the boundary is not very certain). The grey shaded areas are the MOW inferred based on seismicity.

During the second stage, the earthquake began to propagate nearly vertically into deeper regions. HF1 and HF2 were observed to contain 8 and 6 sub-events, respectively, with two simultaneous sub-events at ~610 km observed in both bands at 23–27 s (Supplementary Fig. 8). From ~610 km, HF1 sub-events extended down to ~670 km, while HF2 sub-events reached ~680 km. Spatially, two nearly parallel vertical propagation paths were observed. In the last 5 s, HF2 included two simultaneous sub-events at different depths, with one extending as deep as 680 km and propagating in a direction almost opposite to the initial rupture propagation. A number of simultaneous sub-events during this stage resulted in two nearly parallel downward propagation ruptures (Figs. 2e, f, and 3d). The estimated apparent rupture velocity between events during the second stage exceeded 10 km/s for both HF1 and HF2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). These very high values could indicate that the rupture actually started with a low amplitude that is not represented in our event detection, but compatible with the energy release (Fig. 2a, b). Overall all events occur within a velocity of about 3.3 km/s when measured from the hypocenter (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). The division into two stages here is primarily based on the propagation direction of the earthquake.

Using slab model 2.012 (here, the depth value is used as the upper bound of the slab) and the P-wave tomography model32 (here, dVp/Vp = 1% is used as the slab boundary) as reference slab models, back-projection imaging indicates that the first 10 s occurred outside the slab model boundaries, with a maximum distance of ~40 km from slab model 2.012. The other periods were located within the slab models. In terms of depth, stage 1 occurred near 600 km, and stage 2 propagated from ~610 km to ~670 km. The mainshock locations determined by back-projection and the earthquakes around a depth of 600 km in the Kamchatka catalog33 resemble an en-echelon arrangement (Fig. 3c, d). Overall, the Mw 8.3 Okhotsk earthquake occurred across multiple parallel sub-horizontal planes, with the main rupture concentrated at a depth of ~600 km and propagating deeper in the latest stage. The total extent of the earthquake rupture was 145 km in the north–south direction and 71 km in the east–west direction, with a depth range of 80 km. The spatial distribution range exceeded the predictions of existing slab models12,32.

Discussion

The 4D back-projection from the global array reveals a sequence with multiple stages and the complex geometry of the Okhotsk earthquake. The spatial extension of the different stages shows that the rupture rises at the front (nearly 40 km ahead) of the known slab surface12, indicating the need for appropriate modifications to the current model.

We show that the mainshock of the Okhotsk earthquake can be divided into two stages, multiple sub-events can be identified in both HF1 and HF2. Chen et al.6 identified six sub-events based on multiple-point source inversion. The sub-event and finite-fault inversion methods8,9 also determined four sub-events. For our back-projection results, it is also feasible to divide into 4 stages (Supplementary Fig. 3). In these studies, the first two sub-events exhibited higher amplitudes than the latter two parts of the rupture, contrary to our results (Fig. 2). We attributed this discrepancy to the narrower frequency range in our case. In other words, we missed the high-frequency components, which are not sufficiently coherent at the global scale. The source positions at different times in this study are generally consistent with those of previous back-projection studies7,10,11. However, because we performed the back-projection in three-dimensional space, we can provide precise information on the depth at different times. The first 20 s of slip revealed by the back-projection is consistent with a series of sub-horizontal ruptures, which can still be considered sub-horizontal rupture in 20–30 s, but we consider it to be the beginning of subsequent vertical propagation. Finally, 30–36 s is a near-vertical propagation, in which a sub-event is also observed in HF2 to propagate downward along the previously modeled subduction plane (Figs. 2e, f and 4c, d). However, it is still unclear whether the deep expansion spanned a series of sub-horizontal planes or followed a vertical plane. Overall, our slipping surface geometry is close to the one evaluated by Chen et al.6 through multipoint source inversion.

The subducted slab forms folds at about 600 km, and the folds curvature diminishing progressively toward the south. The earthquake primarily occurred within the folded MOW, propagating horizontally first and then vertically downward (blue arrow). The thick blue line is the plate boundary70. Dark red arrows show the viscous drag reduction of the upper mantle, that induces a transient slab plunge acceleration 1 month before the mainshock53. The bold blue arrow shows the accelerated slab plunge since the great deep earthquake58. The cyan dots are Kamchatka catalog33. The insert shows the study area. The insert panel (a) shows the cumulative energy of the back-projection matrix over a 36-s time window projected onto the horizontal and vertical planes.

The back-projection imaging results combined with background earthquake information can facilitate the analysis of processes responsible for the mainshock’s. Among the three classical proposed deep-focus earthquake source mechanisms, we consider the dehydration embrittlement can be excluded, at least in the version commonly referred to in the literature. As the slab subducts into the high-temperature, high-pressure mantle, hydrous minerals are gradually consumed with increasing depth, ultimately depleting at a depth of approximately 300 km34. Below the Kamchatka Peninsula, the intermediate-depth earthquake activity is consistent with the pattern of dehydration (Supplementary Fig. 9). Although some researchers have used dehydration embrittlement to explain deep-focus earthquakes10,35, in Okhotsk (Supplementary Fig. 9), dehydration cannot explain how the seismicity below 400 km does not decrease with increasing depth36.

Subsequently, we analyzed the possibility of source processes associated with olivine phase transitions and thermal runaway. The key to the transformational faulting is the metastable olivine wedge (MOW)3 within the mantle transition zone. The MOW is expected to gradually narrow from shallower to deeper regions to accommodate increasing temperature and pressure37. The existence of the MOW beneath Japan has been confirmed through seismological measurements38,39. The slab thermal model proposed by Jia et al.40 indicates that below the Okhotsk Sea, the MOW extends to depths below 600 km, reaching the depth of the Mw 8.3 earthquake. Based on the mainshock rupture imaging in our study, background seismic activity33, and the tomography model32, we delineate the possible slab geometries and corresponding MOW configurations (Fig. 3a, c, d). Based on these observations, the slab morphology in the lowermost transition zone likely exhibits at least one folding or a more complex deformation structure around 600 km depth, with the internal MOW deforming in response to the slab’s shape. Strong slab deformation has also been observed seismically in other subduction zones41, and numerical simulations have also demonstrated the possibility of bending and folding42,43. For the mainshock, we focus on the MOW morphology along the profile AA’ and BB’. Apart from the sub-event observed outside the MOW by HF2 (Fig. 3d, an event outside the shadow area), all other sub-events can occur within the highly deformed MOW, indicating that the earthquakes are primarily faults triggered by transformations. The exceptionally high apparent rupture velocity and clear separation between sub-events in the second stage suggest that this is not a continuous supershear rupture44. Note that the apparent velocity is of the order of the P-wave velocity at this depth. We interpret the rupture in the second stage to be related to dynamic triggering45. At a depth of 600 km, the folded and deformed slab is rich in stress concentrations that are easily triggered, allowing stress perturbations from one sub-event to rapidly trigger the next9. Additionally, thermal runaway is insufficiently sensitive to dynamic stress perturbations and cannot adequately explain the dynamic triggering of deep-focus earthquakes45. However, the downward propagation of sub-events during stage 2 suggests that the physical processes may differ from the sub-horizontal sub-events in stage 1. In fact, the exothermic nature of transformational faults also incorporates thermal weakening effects3. The high energy release during stage 2 also suggests the possibility of thermal runaway. At the very least, the sub-event observed outside the MOW by HF2 might involve a thermal runaway.

In addition, it is not impossible that all sub-events are caused by thermal runaway. As discussed by Chen and Wen46, shear thermal instability occurs in pre-existing weak regions. Previous studies have rejected thermal runaway based on the inferred higher rupture velocity10,11. Similarly, our imaging results show an abnormally high rupture speed in the vertical stage. Notably, when referenced to the hypocenter, the rupture velocity is not high (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, the difficulty of thermal runaway as a mechanism of deep-focus earthquakes lies in the fact that its trigger conditions are not spontaneously reached47. Meng et al.7 highlighted the critical rupture length required to trigger thermal runaway. Therefore, we preliminarily infer that the earthquakes primarily occur within the deformed MOW and are caused by transformational faults. In the second stage, there may be a mutual reinforcement between transformational faults and thermal instability. This interpretation is consistent with those of Meng et al.7 which discussed the impossibility of initiating thermal runaway near the northern end of the slab. The slice AA’ is located at the corner in contact with the high-temperature mantle46, and from the perspective of heat conduction40, the MOW would vanish when approaching the northern boundary of the slab. Due to the influence of mantle flow, the northern edge of the slab would be warmer and thinner48. Consequently, the lateral extent of stage 1 is limited. In regions farther from the edge, favorable deformation conditions persist, and the cooler slab allows the MOW to extend downward, enabling stage 2 to deepen through dynamic triggering.

Based on the above analysis, we propose a subduction slab model beneath the Okhotsk Sea (Fig. 4). In a simple first-order model, the slab exhibits one folding at a depth of approximately 600 km near the mainshock, with the curvature diminishing progressively toward the south. The folding can account for the observed earthquake distribution and is consistent with the results of tomographic imaging. Numerical simulations also indicate the possibility of deep slab folding: as the slab crosses the 660 km discontinuity and enters the lower mantle, it experiences an increased resistance and is bent to form folds42,43. Moreover, warmer and thinner slabs are more prone to this type of deformation48. Rheological simulations43 and studies of earthquake locations and source mechanisms41 support high seismic productivity associated with high strain rates. An increase in strain rate can lead to an increase in temperature49 and the destabilization of olivine50. The high strain rate in the folded region promotes both transformation faulting and thermal shear instability43,51,52, which also explains the higher seismicity at a depth of 600 km in the Okhotsk region and the rapid triggering observed in the second stage of the mainshock.

The GNSS time series from the Kamchatka Peninsula showed approximately 18 days of landward movement one month prior to the mainshock, indicating an acceleration of the slab sinking53. Plunge is the sinking motion of the subducting slab, and this temporary acceleration caused by changes in external forces is called transient plunge. The deep folds are then further compressed and sheared, preparing for the occurrence of the mainshock. Additionally, a low-density, ultra-low P-wave velocity anomaly is present near the 660 km discontinuity beneath the subducting slab18. The buoyancy from the low-density anomaly and the resistance from the lower mantle provide a squeezing force from below, which, in conjunction with the pressure generated by the slab’s own subduction, acts on the fold and promotes the occurrence of large deep earthquakes. The strain accumulation at a depth of 600 km facilitated phase transformational faulting within the MOW, and the subsequent high-temperature generated by the rupture triggered thermal runaway, causing the rupture to propagate beyond the MOW.

Our study provides supplementary information regarding the detailed structure of the slab. The results of tomography imaging suggest that the Pacific Plate beneath the Okhotsk Sea subducts into the lower mantle32,54,55,56. We confirm this supposition, with the additional element that a folded slab should exist at 600 km to further explain the distribution range of earthquakes, based on the constraints from the mainshock imaging and background seismic activity. The shape of the Kuril–Kamchatka subduction zone changes noticeably from south to north54,55,56. The southern segment (for latitude <50°N) of the subduction zone does not penetrate the mantle transition zone, with the plate’s limit extending horizontally at the 660 km discontinuity. The central segment (for 50°N <latitude <54°N) penetrates the 660 km discontinuity and enters the lower mantle. The northern segment (for latitude >54°N), however, bends and forms folds prior to entering the lower mantle. The Okhotsk earthquake was located at the deep northern edge of the slab, and even when examining the intermediate depths of the slab, the seismic activity at the slab’s north edge is less than that within the slab (Fig. 3a). At the northern edge of the slab, the presence of a lateral discontinuity implies different temperature and pressure conditions compared to ones in the continuous slab and could have promoted the folding above the 660 km phase transition.

The geodetic changes before and after the great deep event illustrate the non-stationary nature of the subduction movement. At shallower depths, it is widely observed that the slab’s motion is influenced primarily by slow-slip events, which release accumulated strain over a prolonged period, causing incremental subduction57. Before and after the Mw 8.3 Okhotsk Sea earthquake we observe a deeper counterpart. The transient acceleration of the slab resulting from a viscous drag reduction at intermediate depths described in Rousset et al.53 can be linked to the triggering of the great earthquake in the largely deformed deep zone, which was affected by the increase in stress that was caused by the transient. At depths where deep-focus earthquakes occur, increased stress and deformation within the slab induce phase changes or thermal anomalies, which may also promote further movement of the slab sinking. Chronologically, these mechanisms interact to govern the slab’s plunge dynamics from surface to mantle transition zones. The great earthquake was initiated in the folded MOW and also activated slip by thermal runaway on a dipping plane parallel to the subduction. This weakened plane facilitates the penetration of the slab in the mantle, this is what is suggested by the increase of the subduction rate at depth for at least a decade after the Mw 8.3 event as evidenced by the increase in GNSS velocities at the regional scale observed by Shestakov et al.58.

Method

Using the hypocentre location provided by the USGS as an a priori location (54.892°N, 153.221°E, depth 598 km), a 3D target grid was constructed with a range of 52°N–57°N, 150°E–155°E, and a depth of 400–800 km (the depth difference given by different institutions2,59,60,61 was approximately 30 km). The grid cells had a resolution of 0.1°N × 0.1°E × 10 km. To ensure optimal P-wave illumination of the target area, we selected all global stations at epicentral distances of 30°–95° from the hypocentre. Seismic data were downloaded, and instrumental responses were removed. We then obtained displacement waveforms in the frequency range of 0.02–5 Hz. The ak135 radial velocity model for the Earth62 was used to estimate the arrival time of the first P-wave. The waveforms were truncated 10 s before and 40 s after the theoretical P-wave arrival at each station. Recordings from both the Southern California Seismic Network (CI) and the Transportable Array (USArray, TA) were stacked to generate a reference waveform. The correlation coefficient between all waveforms and this reference was calculated, and only waveforms with absolute correlation coefficients greater than 0.7 were retained. Ultimately, 2992 stations were retained (3380 in total; 388 stations were discarded), as shown in Fig. 1. The red stations in Fig. 1 refer to the observed positive polarity of the direct P-wave.

The first 10 s P-waves of all stations were cross-correlated to align the waveforms and correct for travel time anomalies due to the complex structure of the earth along the path between the source and the station63. The time-correction terms for the stations were less than 3 s (Supplementary Fig. 10a). We did not use aftershock correction because the only high-quality aftershock was far from the mainshock (approximately 320 km southwest44).

Owing to the uneven distribution of stations, weighting by the group of stations64 was applied. We used equal-area triangulation on the Earth’s surface65, and the stations within each triangle were regarded as one group. The stations were finally divided into 317 groups (Fig. 1a, where one color is one group; the equivalent stations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10b). The image of the equivalent array response function at 0.5 Hz after group weighting is shown in Fig. 1d–f. The vertical resolution is relatively poor owing to the steep take-off angle of the teleseismic P-wave. However, reasonable depth determination can still be achieved (The 95% main lobe width of the array response function at 0.5 Hz in the depth direction is approximately 20 km). Considering the signal-to-noise ratio and resolution, we used fourth root stacking66,67. Two frequency bands, HF1 (0.5–2 Hz) and HF2 (0.33–1 Hz), were considered, and the corresponding waveforms are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. It shows aligned waveforms of all stations we use based on USGS, and polarity correction on the initial impulse. The good coherence supports our back-projection approach.

Back-projection was applied every second for each point of our grid (Fig. 1b, blue cube), and we used a smoothing time window of 4 s. Then, to explore the 4D volume and identify a sequence of sub-events, we first calculated the depth-only versus time amplitude matrix (hereinafter referred to as the DTA matrix) of the back-projection. It was defined as the maximum value of the back-projection energy at each time step and at a specified depth, i.e.

where \(E(x,y,z,t)\) is the stacked energy at grid point \((x,y,z)\) and time t (x is the longitude, \(x\in [150,155]\), y is the latitude, \(y\in [52,57]\), z is the depth, and t is the time), which is a 4D matrix representing the energy distribution of the back-projected earthquake in 3D space and time. Supplementary Fig. 12 shows the DTA results for HF1 and HF2. Based on this preliminary imaging result, we refined the target volume for back-projection, narrowing the range to 53.5°N–55.5°N, 151.5°E–154.5°E, and 550–700 km, with a grid spacing of 0.02°N × 0.03°E × 2 km. Deconvolution was then used to improve the back-projection resolution. Two-dimensional deconvolution was used to improve the resolution of the back-projections24,68. We applied a three-dimensional Richardson–Lucy deconvolution at each time step of \(E(x,y,z,t)\) to remove the array response. The deconvolution of \(E(x,y,z,t)\) resulted in a higher resolution (Supplementary Fig. 13), and correspondingly, the resolution of the DTAs was also improved.

The back-projection beam energy in the DTA results exhibits a slanted distribution (Supplementary Fig. 12), and this smearing in the depth–time domain is similar to that in the spatial domain, which is related to the array configuration21,69. In such cases, using the maximum value of DTA at each time step to determine earthquake depth would be erroneous, leading to inaccurate rupture velocities (Supplementary Fig. 14, examples of synthetic data). Recognizing the slanted distribution of back-projection energy, we take the maximum energy point (or center point) of a sub-event as its time and position (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then, the rupture propagation velocity is calculated (Supplementary Fig. 5).

We further analyzed the depth resolution of global station back-projection by conducting comprehensive synthetic data tests and back-projection imaging of a major aftershock (Mw 6.7). The results (see supplementary information, Figs. 15–18, Tables 1–3) indicate that global station direct P-wave back-projection can constrain earthquake depth, with depth resolution depending on magnitude and frequency. The back-projection of the Mw 6.7 aftershock demonstrated that in HF1 could achieve a depth resolution of 5–10 km. In our method, depth constraints rely on wide azimuthal coverage and a broad range of epicentral distances, which correspond to a wide range of take-off angles.

Data availability

The global seismic data were downloaded through the International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks (FDSN) web services. The P-wave tomography model is available at: https://ds.iris.edu/ds/products/emc-tx2019slab/. The Okhotsk seismicity catalog is available from the website of the Kamchatkan Branch of the Geophysical Survey of the Russian Academy of Sciences: http://sdis.emsd.ru/info/earthquakes/catalogue.php.L.

Code availability

All calculations made in this article are either described in the “Methods” section or based on the codes or software cited in the reference list.

References

Benz, H. M. Global catalog of calibrated earthquake locations, U.S. Geol. Surv. Data Release https://doi.org/10.5066/P95R8K8G (2021).

U.S. Geological Survey, https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usb000h4jh/executive#summary (2025).

Zhan, Z. Mechanisms and implications of deep earthquakes. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 147–174 (2020).

Green, H. W. & Houston, H. The mechanics of deep earthquakes. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 23, 169–213 (1995).

John, T. et al. Generation of intermediate-depth earthquakes by self-localizing thermal runaway. Nat. Geosci. 2, 137–140 (2009).

Chen, Y., Wen, L. & Ji, C. A cascading failure during the 24 May 2013 great Okhotsk deep earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 119, 3035–3049 (2014).

Meng, L., Ampuero, J. P. & Bürgmann, R. The 2013 Okhotsk deep‐focus earthquake: rupture beyond the metastable olivine wedge and thermally controlled rise time near the edge of a slab. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3779–3785 (2014).

Zhan, Z., Kanamori, H., Tsai, V. C., Helmberger, D. V. & Wei, S. Rupture complexity of the 1994 Bolivia and 2013 Sea of Okhotsk deep earthquakes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 385, 89–96 (2014a).

Wei, S., Helmberger, D., Zhan, Z. & Graves, R. Rupture complexity of the Mw 8.3 Sea of Okhotsk earthquake: rapid triggering of complementary earthquakes? Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5034–5039 (2013).

Zhang, H., van der Lee, S., Bina, C. R. & Ge, Z. Deep dehydration as a plausible mechanism of the 2013 Mw 8.3 Sea of Okhotsk deep-focus earthquake. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 521220 (2021).

Ye, L., Lay, T., Kanamori, H. & Koper, K. D. Energy release of the 2013 M w 8.3 Sea of Okhotsk earthquake and deep slab stress heterogeneity. Science 341, 1380–1384 (2013).

Hayes, G. P. et al. Slab2, a comprehensive subduction zone geometry model. Science 362, 58–61 (2018).

Jia, Z. et al. The 2018 Fiji Mw 8.2 and 7.9 deep earthquakes: one doublet in two slabs. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 531, 115997 (2020).

Ye, L., Lay, T., Zhan, Z., Kanamori, H. & Hao, J. L. The isolated∼ 680 km deep 30 May 2015 Mw 7.9 Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 433, 169–179 (2016).

Obayashi, M., Fukao, Y. & Yoshimitsu, J. Unusually deep Bonin earthquake of 30 May 2015: a precursory signal to slab penetration? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 459, 221–226 (2017).

Zhang, H., Wang, F., Myhill, R. & Guo, H. Slab morphology and deformation beneath Izu-Bonin. Nat. Commun. 10, 1310 (2019).

Zhan, Z., Helmberger, D. V. & Li, D. Imaging subducted slab structure beneath the Sea of Okhotsk with teleseismic waveforms. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 232, 30–35 (2014b).

Chen, W., Wei, S. & Wang, W. Subslab ultra low velocity anomaly uncovered by and facilitating the largest deep earthquake. Nat. Commun. 15, 2754 (2024).

Ishii, M., Shearer, P. M., Houston, H. & Vidale, J. E. Extent, duration and speed of the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake imaged by the Hi-Net array. Nature 435, 933–936 (2005).

Krüger, F. & Ohrnberger, M. Tracking the rupture of the Mw = 9.3 Sumatra earthquake over 1,150 km at teleseismic distance. Nature 435, 937–939 (2005).

Kiser, E. & Ishii, M. Back-projection imaging of earthquakes. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 45, 271–299 (2017).

Meng, L., Ampuero, J. P., Sladen, A., & Rendon, H. High‐resolution backprojection at regional distance: Application to the Haiti M7. 0 earthquake and comparisons with finite source studies. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008702 (2012).

Yagi, Y., Nakao, A. & Kasahara, A. Smooth and rapid slip near the Japan Trench during the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake revealed by a hybrid back-projection method. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 355, 94–101 (2012).

Wang, D., Takeuchi, N., Kawakatsu, H. & Mori, J. Estimating high frequency energy radiation of large earthquakes by image deconvolution back-projection. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 449, 155–163 (2016).

Kehoe, H. L., Kiser, E. D. & Okubo, P. G. The rupture process of the 2018 Mw 6.9 Hawaiʻi earthquake as imaged by a genetic algorithm‐based back‐projection technique. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 2467–2474 (2019).

Walker, K. T. & Shearer, P. M. Illuminating the near‐sonic rupture velocities of the intracontinental Kokoxili Mw 7.8 and Denali fault Mw 7.9 strike‐slip earthquakes with global P wave back projection imaging. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jb005738 (2009).

Xie, Y. et al. The 2021 Mw 7.3 East Cape earthquake: triggered rupture in complex faulting revealed by multi‐array back‐projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099643 (2022).

Rößler, D., Krueger, F., Ohrnberger, M. & Ehlert, L. Rapid characterisation of large earthquakes by multiple seismic broadband arrays. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 923–932 (2010).

Steinberg, A., Sudhaus, H. & Krüger, F. Using teleseismic backprojection and InSAR to obtain segmentation information for large earthquakes: a case study of the 2016 M w 6.6 Muji earthquake. Geophys. J. Int. 232, 1482–1502 (2023).

Yao, H., Shearer, P. M. & Gerstoft, P. Sub-event location and rupture imaging using iterative backprojection for the 2011 Tohoku M w 9.0 earthquake. Geophys. J. Int. 190, 1152–1168 (2012).

Palo, M., Tilmann, F., Krüger, F., Ehlert, L. & Lange, D. High-frequency seismic radiation from Maule earthquake (M w 8.8, 2010 February 27) inferred from high-resolution backprojection analysis. Geophys. J. Int. 199, 1058–1077 (2014).

Lu, C., Grand, S. P., Lai, H. & Garnero, E. J. TX2019slab: a new P and S tomography model incorporating subducting slabs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 11549–11567 (2019).

Chebrov, V. N. et al. The system of detailed seismological observations in Kamchatka in 2011. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 7, 16–36 (2013).

Jung, H., Green Ii, H. W. & Dobrzhinetskaya, L. F. Intermediate-depth earthquake faulting by dehydration embrittlement with negative volume change. Nature 428, 545–549 (2004).

Zahradník, J. et al. A recent deep earthquake doublet in light of long-term evolution of Nazca subduction. Sci. Rep. 7, 45153 (2017).

Green II, H. W., Chen, W. P. & Brudzinski, M. R. Seismic evidence of negligible water carried below 400-km depth in subducting lithosphere. Nature 467, 828–831 (2010).

Kirby, S. H., Durham, W. B. & Stern, L. A. Mantle phase changes and deep-earthquake faulting in subducting lithosphere. Science 252, 216–225 (1991).

Jiang, G. & Zhao, D. Metastable olivine wedge in the subducting Pacific slab and its relation to deep earthquakes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 42, 1411–1423 (2011).

Shen, Z. & Zhan, Z. Metastable olivine wedge beneath the Japan Sea imaged by seismic interferometry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085665 (2020).

Jia, Z., Fan, W., Mao, W. & Shearer, P. M. Dual mechanism transition controls rupture development of large deep earthquakes, submitted to Sci. Adv. (2024).

Myhill, R. Slab buckling and its effect on the distributions and focal mechanisms of deep-focus earthquakes. Geophys. J. Int. 192, 837–853 (2013).

Suchoy, L., Goes, S., Maunder, B., Garel, F. & Davies, R. Effects of basal drag on subduction dynamics from 2D numerical models. Solid Earth 12, 79–93 (2021).

Billen, M. I. Deep slab seismicity limited by rate of deformation in the transition zone. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz7692 (2020).

Zhan, Z., Helmberger, D. V., Kanamori, H. & Shearer, P. M. Supershear rupture in a Mw 6.7 aftershock of the 2013 Sea of Okhotsk earthquake. Science 345, 204–207 (2014c).

Tibi, R., Wiens, D. & Inoue, H. Remote triggering of deep earthquakes in the 2002 Tonga sequences. Nature 424, 921–925 (2003).

Chen, Y. & Wen, L. Global large deep-focus earthquakes: source process and cascading failure of shear instability as a unified physical mechanism. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 423, 134–144 (2015).

Kelemen, P. B. & Hirth, G. A periodic shear-heating mechanism for intermediate-depth earthquakes in the mantle. Nature 446, 787–790 (2007).

Levin, V., Shapiro, N., Park, J. & Ritzwoller, M. Seismic evidence for catastrophic slab loss beneath Kamchatka. Nature 418, 763–767 (2002).

Ogawa, M. Shear instability in a viscoelastic material as the cause of deep focus earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 92, 13801–13810 (1987).

Marone, C. & Liu, M. Transformation shear instability and the seismogenic zone for deep earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 24, 1887–1890 (1997).

Burnley, P. C., Green, H. W. & Prior, D. J. Faulting associated with the olivine to spinel transformation in Mg2GeO4 and its implications for deep‐focus earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 96, 425–443 (1991).

Ohuchi, T. et al. Intermediate-depth earthquakes linked to localized heating in dunite and harzburgite. Nat. Geosci. 10, 771–776 (2017).

Rousset, B. et al. The 2013 slab‐wide Kamchatka earthquake sequence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101856 (2023).

Fukao, Y. & Obayashi, M. Subducted slabs stagnant above, penetrating through, and trapped below the 660 km discontinuity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 5920–5938 (2013).

Koulakov, I. Y., Dobretsov, N. L., Bushenkova, N. A. & Yakovlev, A. V. Slab shape in subduction zones beneath the Kurile–Kamchatka and Aleutian arcs based on regional tomography results. Russian Geol. Geophys. 52, 650–667 (2011).

Cui, Q. et al. The topography of the 660-km discontinuity beneath the Kuril-Kamchatka: implication for morphology and dynamics of the northwestern Pacific slab. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 602, 117967 (2023).

Bürgmann, R. The geophysics, geology and mechanics of slow fault slip. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 495, 112–134 (2018).

Shestakov, N. V. et al. GNSS-based modeling and study of postseismic crustal movement of the May 24, 2013, MW 8.3 Sea of Okhotsk deep-focus earthquake. Geodyn. Tectonophys. 15, 0761 (2024).

Dziewonski, A. M., Chou, T.-A. & Woodhouse, J. H. Determination of earthquake source parameters from waveform data for studies of global and regional seismicity. J. Geophys. Res. 86, 2825–2852 (1981).

Ekström, G., Nettles, M. & Dziewonski, A. M. The global CMT project 2004-2010: centroid-moment tensors for 13,017 earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 200–201, 1–9 (2012).

Chebrova A.Y., Chemarev, A. S., Matveenko, E. A. & Chebrov, D. V. Seismological data information system in Kamchatka branch of GS RAS: organization principles, main elements and key functions. Geophys. Res. 21, 66–91 (2020).

Kennett, B. L., Engdahl, E. R. & Buland, R. Constraints on seismic velocities in the Earth from traveltimes. Geophys. J. Int. 122, 108–124 (1995).

Ishii, M., Shearer, P. M., Houston, H. & Vidale, J. E. Teleseismic P wave imaging of the 26 December 2004 Sumatra‐Andaman and 28 March 2005 Sumatra earthquake ruptures using the Hi‐net array. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004700 (2007).

Zhang, R., Boué, P., Campillo, M. & Ma, J. Quantifying P‐wave secondary microseisms events: a comparison of observed and modelled backprojection. Geophys. J. Int. 234, 933–947 (2023).

Moresi, L. & Mather, B. R. Stripy: a Python module for (constrained) triangulation in Cartesian coordinates and on a sphere. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1410 (2019).

Rost, S. & Thomas, C. Array seismology: methods and applications. Rev. Geophys. 40, 2–1 (2002).

Xu, Y., Koper, K. D., Sufri, O., Zhu, L. & Hutko, A. R. Rupture imaging of the Mw 7.9 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake from back projection of teleseismic P waves. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GC002335 (2009).

Haney, M. M. Backprojection of volcanic tremor. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1923–1928 (2014).

Kiser, E., Ishii, M., Langmuir, C. H., Shearer, P. M. & Hirose, H. Insights into the mechanism of intermediate‐depth earthquakes from source properties as imaged by back projection of multiple seismic phases. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JB007831 (2011).

Bird, P. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000252 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for helping improve the quality of the manuscript. We acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42230806, U23B6010) and China National Petroleum Corporation-Peking University Strategic Cooperation Project of Fundamental Research, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 742335, F-IMAGE), and from the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the project TERRACORR (ANR-20-CE49-0003), and China Scholarship Council. Most of the computations presented in this paper were performed using the GRICAD infrastructure (https://gricad.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr), which is supported by Grenoble research communities. The seismicity catalog used in our analysis is available from the website of the Kamchatkan Branch of Geophysical Survey of the Russian Academy of Sciences: http://sdis.emsd.ru/info/earthquakes/catalogue.php. We used data from numerous seismic networks, and we thank all of the people involved in the data acquisition, station maintenance, QC, and distribution. All networks’ citations are in supplementary information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. P.B. & M.C.: Supervision, Quality Control, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. J.M.: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Luca Dal Zilio and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, R., Boué, P., Campillo, M. et al. Two-stage rupture during the Mw 8.3 Okhotsk 2013 deep-focus earthquake constrains slab geometry. Commun Earth Environ 6, 139 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02116-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02116-4