Abstract

Deep water masses of the North Atlantic Ocean are formed in the subpolar regions through ocean-atmosphere interactions, imprinting unique climate signals like anomalous temperature and salinity on the deep waters that are exported to the Subtropical North Atlantic. Sustained hydrographic, mooring, and seafloor temperature surveys off Abaco Island, Bahamas at 26.5°N have illuminated significant cooling and freshening of the deep ocean (>2000 m) over the past four decades, challenging the paradigm of anticipated deep ocean warming in the Subtropical North Atlantic. Here, we discuss a linkage between the deep Subtropics and Subpolar North Atlantic, finding synchronicity between the observed freshening at 26.5°N and a multi-decadal freshening event in the subpolar basins occurring more than two decades prior. Findings hint at the likely onset of subtropical deep ocean warming and salinification in the near future, which could have notable impacts on deep ocean Atlantic heat content, circulation, and sea level changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ocean heat uptake is one of the leading consequences of human-induced warming of the global atmosphere. Amidst a rapidly changing climate, it is critical to observe discrete oceanic changes and accurately predict forthcoming societal impacts. In the Atlantic, large scale ocean circulation is responsible for moving heat, freshwater, nutrients, and carbon from the poles to the tropics. Changes in these transports can yield basin-wide impacts in ocean warming, as well as sea level changes and ecosystem imbalance. Hydrographic evidence has documented wide-spread heat uptake and resultant ocean warming in both the upper (<2000 m) and deep (>2000 m) Atlantic Ocean since the turn of the century1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Ocean warming directly impacts coastal sea-level through the process of thermal expansion, and coastal observing systems along the western Atlantic have already seen levels climb past +10 mm per year9,10,11. As global temperatures continue to rise, heat uptake in the regions of deep water formation that in-part drive large-scale ocean circulation is anticipated to significantly warm the deep ocean; observations have shown that this has already begun6.

While property changes (e.g. temperature, salinity) of the surface ocean reflect local heat and freshwater exchanges across the air-sea interface, property changes of the deep ocean are instead reflective of the region of deep water formation and subsequent circulation. These property changes at depth often reflect surface conditions from the past, providing memory to the deep ocean. Through ocean-atmosphere interactions, northward flowing tropical Atlantic surface waters cool, become dense and sink upon arrival in the Subpolar North Atlantic. The Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) serves as one of the main equatorward pathways that exports these deep waters to the subtropics at depths below 1000 m. The Abaco 26.5°N hydrographic line (Fig. 1A) is situated at a strategic location within the Subtropical North Atlantic, capturing both the poleward flowing upper-ocean subtropical gyre waters and the deep-ocean equatorward return flows of the DWBC. Over the past 40 years (1985-present), the 26.5°N hydrographic line has been surveyed quasi-annually through collaborative efforts between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Western Boundary Time Series (WBTS) project, the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science’s Meridional Overturning Circulation and Heat-flux Array (MOCHA) project, and the National Oceanographic Centre’s Rapid Climate Change (RAPID) program. Sustained monitoring at 26.5°N has been achieved through repeat hydrographic surveys12,13, the use of Pressure-Inverted Echo Sounders14,15 (PIES) and continuous mooring installations dating back to 200416. Nearly four decades of sustained observations along this latitude make this hydrographic line part of the longest-running trans basin meridional overturning observation program on the planet16,17,18.

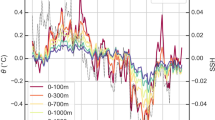

A The Abaco 26.5°N hydrographic line off the coast of Abaco Island, Bahamas. Stations are shown as black dots; bathymetric contours in 1000 m intervals. Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) flow is indicated by the gray arrow, with the 140 km DWBC throughflow region highlighted in blue (congruent with Zone 1). B Mean neutral density (γn, kg m-3) structure of the four water masses investigated in this study showing the three partitioned zones of the 26.5°N hydrographic line: Zone 1 captures the equatorward-flowing DWBC, Zone 2 captures the middle region of the transect and the opposing northward return flow of the deep Abaco gyre, and Zone 3 captures the weaker flow regime offshore of the western boundary and into the ocean interior. The four water masses of investigation are shown colored (Intermediate, teal; Deep, light blue; Abyssal, dark blue; AABW (Antarctic Bottom Water), indigo) distinguished by constant neutral density layer boundaries (γn, shown). Hydrographic profiles are gridded with 10 km spacing, indicated by the black triangles. C 26.5°N hydrographic trends of salinity (left) and potential temperature (right) of the four defined water masses across each respective zone (Zone 1, circles; Zone 2, crosses; Zone 3, stars) with mean trend per decade shown. Uncertainty represents the 95% confidence interval.

Elsewhere in the North Atlantic, observing systems across the advective path of the DWBC have monitored circulation and variability of the deep water mass properties therein. These deep water masses (e.g. Labrador Sea Water, Iceland Scotland Overflow Water, Northeast Atlantic Deep Water, Denmark Strait Overflow Water), collectively known as North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), are formed through the transformation of warm and salty subtropical waters into cold and dense deep waters, each specific to its region of formation and local environmental conditions. Studies in recent decades have highlighted the advection of a notable component of NADW, Labrador Sea Water (LSW), along the path of the DWBC by documenting the onset of an anomalously-low temperature and salinity signature characteristic to convectively-formed LSW masses19. At 26.5°N, four decades of hydrographic data have revealed the arrival of this subpolar convective signal within the LSW layer (approximately between 1000 and 2000 m) in the late 1990s by the onset of a temperature and salinity minimum20, continued persistence over a decade later21, and the complete passage and return to warmer and saline conditions in the 2010s22. The onset of cooling and freshening followed by warming and salinification at 26.5°N mimicked deep water formation conditions that occurred in the LSW source region in the Subpolar North Atlantic 10-15 years earlier21,22, providing a climatic link between these two Atlantic regions. Upstream of 26.5°N, connectivity between the source of LSW and locations elsewhere in the North Atlantic have further affirmed the linkage of the Subpolar North Atlantic to the intermediate layers of the Subtropical North Atlantic via the DWBC and interior spreading pathways19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The environmental imprints within the exported NADW aid in the understanding of deep ocean circulation pathways and time scales, but more importantly, can serve as predictors for forthcoming deep ocean conditions in the Subtropical Atlantic given what is known about preexisting conditions in the Subpolar formation region.

With a greater understanding of the interplay between the Subpolar and the Subtropical North Atlantic at intermediate depths (1000–2000 m depth range occupied by LSW), we focus here on the deep ocean (>2000 m) at 26.5°N where nearly four decades of ship-based, tall-mooring, and seafloor hydrographic observations begin to unveil a surprising new take on the matter of ocean warming. For the first time at this location, to the best of our knowledge, we find nearly 40 years of significant cooling and freshening of the deep ocean at 26.5°N, challenging the paradigm of anticipated deep ocean warming in the Subtropical North Atlantic.

Results

Deep Cooling and Freshening at 26.5°N

The Abaco 26.5°N hydrographic line off Abaco Island, Bahamas (hereafter 26.5°N) is divided into three longitudinal zones encapsulating the varying dynamics of this subtropical region (Fig. 1B; refer to Methods). Across all zones, we identify four deep-ocean water mass layers (Intermediate constraining LSW, Deep (note, this italicized name is separate from the descriptor ‘deep’ in reference to all water masses exceeding 2000 m) constraining Northeast Atlantic Deep Water (NEADW) and Iceland Scotland Overflow Water (ISOW), Abyssal constraining Denmark Strait Overflow Water (DSOW), and AABW constraining Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW); Fig. 1B) bounded by constant neutral density isopycnals characterized by historical water mass classification22,32 and seawater property identification using the existing hydrographic dataset.

Hydrographic trends indicate significant freshening and cooling of the deep ocean (>2000 m) in the defined Deep (approximately 2000–3000 m), Abyssal (~3000–4500 m), and AABW (>4500 m) layers across all three zones since the beginning of observations in 1985 (Fig. 1C). The reported mean decadal trends (Fig. 1C) are significant at a 95% confidence level. Relatively steady and synchronous freshening of the Deep (-0.0047 ± 0.0007 practical salinity units (PSU) per decade), Abyssal (-0.0051 ± 0.0009 PSU per decade), and AABW (-0.0051 ± 0.0008 PSU per decade) layers are contrasted, however, by varying cooling rates, with the Abyssal layer showing the largest decline in layer temperature of -0.0433 ± 0.0148 °C per decade (Deep, -0.0352 ± 0.0062 °C per decade; AABW, -0.0291 ± 0.0070 °C per decade). Across all deep ocean masses (>2000 m) along the entire 26.5°N time series record, we observe continual deep ocean freshening and cooling on the order of -0.0250 ± 0.0051 PSU and -0.2523 ± 0.0866 °C, respectively.

To compare with deep trends below 2000 m, we look above 2000 m in the Intermediate layer where an initial cooling and freshening trend reached a minimum in 2008, followed by a warming and salinification trend into present day. The advection of this anomalous signal within the Intermediate layer is studied extensively in prior studies20,21,22, and is attributed to the LSW mass that convectively formed in the Labrador Sea in the 1990s which advected through 26.5°N via the DWBC and interior Atlantic pathways27. The most recent hydrographic conditions within the Intermediate layer are nearly comparable to those at the start of the surveying program in 1985, suggesting the complete passage of an anomalous climate signal. This complete passage is further elaborated using salinity anomalies across all three spatial zones in Fig. 2, whereas the Deep, Abyssal, and AABW layers instead show gradual freshening apparent across all zones through time. A rebound to more saline conditions, as observed in the Intermediate layer, is not evident with the current hydrographic data in these deeper layers.

Salinity anomalies across longitudinal zones 1-3 along the 26.5°N hydrographic line in time for the Intermediate, Deep, Abyssal, and AABW (Antarctic Bottom Water) layers defined in neutral density (γn; kg m-3). Anomalies of each grid point are computed temporally relative to the time mean over a climatological period of 2001-2020. Negative salinity anomalies are denoted in blue shading, indicative of overall freshening. The positions of actual hydrographic observations are overlaid with the black points. Note, not all hydrographic observations are used for the temporal and spatial gridding scheme (refer to Methods).

To enhance the temporal resolution of the 26.5°N hydrographic time series, the existing quasi-annually sampled shipboard hydrographic transect data is supplemented with the hydrographic time series of four fixed tall moorings and bottom-temperature measurements across the 26.5°N transect, providing continuous measurements dating back to initial deployments in 2004 (Fig. 3). Locally at each fixed mooring location (Fig. 3A–D), significant cooling and freshening of the Deep, Abyssal, and AABW layers persists, while the Intermediate layer shows the onset and recovery of a temperature and salinity minimum concurrent with the zonal hydrographic trends. 12-hour continuous and 1-month smoothed sampling of temperature and salinity measurements from the moorings reveal the high-frequency variability (periods from days to a few months) not captured with quasi-annual shipboard hydrographic data. Further assessment reveals differences between some mooring trends and co-located hydrographic trends in density space (refer to trends in Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Tables 3-6). As hydrographic measurements fall within the ranges of the mooring observations over the same time periods, these differences could suggest influence of sampling resolution which is indeed worthy of a follow up investigation. We find depth-averaged decadal layer trends of the 26.5°N hydrographic data to be congruent with the density-averaged layer trends highlighted across this study (and others7), highlighting significant cooling and freshening across the deep ocean locally at 26.5°N.

Four tall-mooring and bottom-temperature locations across the 26.5°N hydrographic line (center) with potential temperature and salinity time series of (A) WB2 and PIES A2 at -76.74°W, (B) WB3 and PIES B at -76.5°W, (C) WB4 and PIES D at -75.7°W, (D) and WB5 and PIES E at -72°W. 12-hour (thin gray line) and 1 month smoothed (black line) continuous tall-mooring hydrographic data is partitioned by water mass layer classifications and supplemented with shipboard collected mean hydrographic data (via a CTD: Conductivity, Temperature, Depth profiling instrument) sampled ±0.2° of the mooring location (circles). Similarly, continuous hourly PIES (Pressure Inverted Echo Sounder) bottom temperature data (thin gray line) and 1 month smoothed (black line) is supplemented with near-bottom shipboard collected mean hydrographic data sampled ±0.2° of the PIES location (circles). Temperature and salinity trends (thick black line) are shown in degrees per decade and practical salinity units per decade, respectively, with uncertainties representative of the 95% confidence interval.

Bottom temperature is measured by temperature sensors located inside Pressure Inverted Echo Sounders (PIES) deployed next to the tall-moorings along the seafloor33. Significant cooling of the bottom-most shipboard hydrographic measurement is observed at the inshore PIES sites of A2, B, and D. Bottom temperature of the continuous PIES time series shows little variability along the aforementioned inshore locations, however, observations at sites PIES D (Fig. 3C) and offshore at site PIES E (Fig. 3D) may hint at decadal variability. While the continuous PIES bottom temperature may suggest decadal variability at Site E, linear tendencies in the bottom-most shipboard hydrographic measurement at the PIES location do not show a significant decline in temperature (−0.0036 ± 0.0092 °C per decade; Fig. 3D). Further continuous sampling is needed across all four bottom temperature locations to discern any significant pattern or decadal-interdecadal variability.

It is shown herein that our western-boundary defined AABW layer presents an overall cooling and freshening trend, contrary to the estimates of AABW warming along 24.5°/26.5°N west of the Mid Atlantic Ridge by prior studies34,35. However, we note that our defined AABW layer likely only captures a small presence of AABW in the Subtropical North Atlantic due to the zonal extent of the hydrographic line (west of -69°W), likely only the western extension of the core. We cannot, therefore, rightfully contrast our observed localized cooling and freshening to the overall Atlantic AABW warming trends5,7,8,35,36,37. Site E, being the furthest offshore at -72°W has the largest likelihood of AABW presence compared to what is likely modified AABW (diluted or mixed with near-bottom NADW) or a lack thereof closer to the western boundary. One of these studies35 also found localized AABW cooling at -72°W (Site E)- and even decadal variability farther south at 16°N- but showed that a warming trend at 26.5°N could be observed farther offshore closer to the AABW core, away from the western boundary and NADW influence. As a standalone finding, the observed freshening and cooling of the AABW layer along the confines of the 26.5°N hydrographic line may suggest a large influence of overlying cold and fresh NADW on AABW property modification in the western Subtropical North Atlantic, or alternatively, a limited presence of AABW in the region.

Upstream Connections

Given the compounding evidence highlighting four decades of significant cooling and freshening of the deep ocean along the Atlantic western boundary at 26.5°N, it now questions whether this signal can be traced back to the source region of these deep waters in the Subpolar North Atlantic. The properties of these deep subpolar waters (LSW from the western Subpolar North Atlantic, and NEADW, ISOW, and DSOW from the eastern Subpolar North Atlantic) are heavily influenced by surrounding environmental conditions within their discrete regions of formation32,38, leaving distinguishable marking characteristics that aid in the identification of these deep masses throughout the global ocean. Further investigation of the salinity anomalies associated with each water mass at 26.5°N is accomplished by looking upstream at several locations along the DWBC, ocean interior, and source regions (Fig. 4), discovering a linkage between the Subpolar and Subtropical North Atlantic.

Salinity anomalies over depth and time across Subpolar source region locations (Labrador Sea, Irminger Sea, Iceland Basin) and downstream Subtropical locations (Cape Cod, Bermuda, and Abaco). Intermediate, Deep, Abyssal, and AABW (Antarctic Bottom Water) neutral density layer boundaries are shown in black contours, where applicable. Labrador Sea, Irminger Sea, and Iceland Basin anomalies are shown using EN4 hydrographic data from the UK Met Office relative to a 1990–2020 climatological mean. Cape Cod anomalies use shipboard hydrographic profiles from the Line W hydrographic section within the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC), Bermuda anomalies use shipboard hydrographic profiles from the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series program, and Abaco anomalies use shipboard hydrographic profiles from the 26.5°N hydrographic line (from the NOAA Western Boundary Time Series Program) within the DWBC (see methods in Ref. 22). Mean salinities of the deep ocean at each location greater than 2000 m (denser than γn = 28.01 kg m-3, constraining all deep ocean water masses) are shown in the figure insert, with declining salinity trends indicated by the colored trend line. Decadal trends are shown with uncertainties given by a 95% confidence interval. Decadal wintertime North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) inverted indices are shown relative to >2000 m subpolar salinity trends.

In the source region of these deep water masses - the Labrador Sea, Irminger Sea, and Iceland Basin—it is evident that an unprecedented multi-decadal salinity anomaly (i.e. freshening event) reached a minimum in the mid-1990s to mid-2000s in the Labrador and Irminger Seas, and mid-2000s in the Iceland Basin in the layers deeper than 2000 m (denser than γn = 28.01 kg m-3; Fig. 4). This subpolar period, from the 1990s to mid-2000s, is characterized by increased freshwater supply from the Nordic overflows, and enhanced surface heat loss due to atmospheric forcing induced by an extreme positive state of the North Atlantic Oscillation39,40,41 (NAO). Across all upstream subpolar locations, substantial anomalous freshening is followed by salinification after 2000, more notably so in the Labrador and Irminger Seas (Fig. 4). Numerous studies have observed and cataloged this multi-decadal subpolar freshening reversal in both the surface and deep ocean farther upstream in the GIN (Greenland, Iceland, and Nordic) seas, highlighting an end to the termed ‘Great-Salinity Anomaly of the 1960s-1990s’39,42,43,44,45,46,47. This deep fresh signal originating from these subpolar locations becomes evident in the deep anomalies farther downstream in the path of the DWBC as this anomaly is imprinted via deepwater formation, exported out of the subpolar region, and advected equatorward in the Atlantic.

Within the DWBC throughflow offshore of Cape Cod at the Line W hydrographic section29,31, the onset of this deep freshening anomaly (salinity minimum, Fig. 4) appears by the mid-2000s and farther downstream at 26.5°N by the late-2000s. Within the Atlantic interior using the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series (BATS), the same deep anomaly appears by the late-2000s and early-2010s. As Ref. 39,42 also highlighted with four decades of observed freshening in the Subpolar North Atlantic, mean salinities across locations at depths greater than 2000 m (denser than γn = 28.01 kg m-3 constraining all deep ocean water masses; Fig. 4, inset) show consistent and significant freshening of the source region basins dating back to the early 1970s with maximum freshening occurring in the early to mid-2000s, followed by a rebound in salinification. A recent reversal and decline in deep ocean temperature beginning in the mid-2010s across both the western and eastern Subpolar North Atlantic40,48 could explain the secondary upstream freshening event simultaneously occurring from the mid-2010s until 2021 following the salinification period (Fig. 4, upper inset). Outside of the subpolar source region, persistent freshening is observed at all locations greater than 2000 m. As Ref. 22 investigated with the passage of the LSW anomalies within the Intermediate layer (γn = 27.87–28.01 kg m-3, approximately 1200–2000 m) from the source region to 26.5°N, a rebound to saline conditions was shown after the full propagation of the anomaly. Whether or not a salinity rebound in the deeper layers greater than 2000 m can be expected in the Subtropical North Atlantic remains the question of interest. Based upon the mean salinity trends of the deep ocean (Fig. 4, inset), the steepest decline in salinity in the Labrador and Irminger Seas from the early 1990s reaches Cape Cod between 2003 and 2004, Bermuda between 2010 and 2013, and Abaco (26.5°N) between 2006 and 2009. The discrepancy in arrival time of the signal to the subtropics may suggest that deeper NADW (>2000 m; denser than γn = 28.01 kg m-3) advects along a faster route via the DWBC to 26.5°N and a slower interior route to Bermuda, if we speculate similarly based upon conclusions of known Intermediate layer (LSW) advective pathways21,22,27. An increase in salinity is shown in the mean trend at 26.5°N near the end of the record (2019) which may possibly be the leading edge of the expected subpolar salinification signal from 2000. This uptick is not yet clearly evident in the discrete 26.5°N hydrographic record (Figs. 1–3), however, given the upstream evidence of a multi-decadal salinity anomaly in the Subpolar North Atlantic, we anticipate a salinity and temperature increase of the subtropical deep ocean within the coming decade.

Discussion

Nearly four decades of deep ocean observations along the Abaco 26.5°N hydrographic line have shown evidence of cooling and freshening in the water mass layers below 2000 m. These findings present an anomaly in deep ocean warming, which has already been observed elsewhere across the Atlantic since the turn of the century1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. We suggest a climatic link between the deep Subpolar North Atlantic and the deep Subtropical North Atlantic through salinity anomalies, where the continuous deep cooling and freshening at 26.5°N is attributed to a multi-decadal freshening event (1970s–2000s) in the subpolar source regions that reached a salinity minimum in the late-1990s to early-2000s, imprinting this anomaly to the deep ocean (>2000 m) through deep-layer convection and water mass formation. The exact forcing mechanisms responsible for the 30+ years of persistent deep subpolar freshening are still uncertain, although many studies attribute this salinity anomaly to NAO surface heat flux-forcing in an extreme positive state40,49 (see Fig. 4 inset) and anomalously large ice (and thus, freshwater) exports from the Beaufort Gyre in the Arctic Ocean into the Subpolar North Atlantic50,51,52. Continued investigation is necessary to positively identify the driving mechanism(s) for sustained freshening in the Subpolar North Atlantic given the limited observational record present to detect multi-decadal variability. More recently, surface freshening across the eastern Subpolar North Atlantic beginning in the mid-2010s was proposed to be driven by strong atmospheric forcing, pronounced surface heat loss across the basins, and increased Arctic-sourced freshwater inflows53,54, which has now subsequently imprinted a new salinity anomaly upon the deep waters formed in this region55,56,57. Nonetheless, the deep-ocean salinity imprint from the multi-decadal subpolar anomaly discussed herein, and likely future anomalies, will help predict downstream ocean conditions given continued knowledge of NADW export, equatorward circulation patterns, and advective time scales. Based on the upstream observations in the Subpolar North Atlantic, a significant increase in deep ocean salinity and temperature in the western Subtropical North Atlantic is anticipated in the near future following the passage of this subpolar salinity anomaly.

The arrival of this postulated forthcoming deep ocean warming and salinification signal in the near future could have ramifications to ocean heat and freshwater content and therefore impact large scale sea level and ocean circulation in the Subtropical North Atlantic. The tendencies observed herein of the deep ocean at 26.5°N are likely attributed to interdecadal variability observed upstream in the Subpolar North Atlantic as aforementioned, however the observational record is still too short to fully resolve and separate it from any anthropogenic forcing. Future work based on longer observational records and/or sufficiently long ocean and climate model simulations will help to test the hypothesized mechanisms discussed herein. Continued hydrographic monitoring of 26.5°N and upstream locations across the North Atlantic is necessary to discern this variability and to predict the societal and ecosystem impacts in the coming decade.

Methods

Hydrographic Data

Hydrographic data along the 26.5°N hydrographic line are compiled from the NOAA Western Boundary Time Series program (https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/wbts/data.php; https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/ftp/phod/WBTS/Global_Class/GC_calibrated_data_archive/). Full-depth, continuous shipboard hydrographic measurements of pressure, salinity, and temperature via a CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, Depth profiling instrument) are captured quasi-annually from 1985-2023 along the transect due east of Abaco Island, Bahamas spanning -77°W to -69°W (Fig. 5). Hydrographic profiles are pre-processed, calibrated, and quality-controlled via the methods described in Ref. 12 A secondary round of processing and quality control is performed to limit the impact of short-term (<1 year) variability associated with eddies, planetary waves, and/or Gulf Stream or Subtropical Gyre intrusion22. Hydrographic profiles for each occupation are gridded with 10 km zonal and 1db vertical spacing. Gridded time series of temperature and salinity for the 26.5°N tall mooring array (WB2, -76.74°W; WB3, -76.5°W; WB4, -75.7°W; WB5, -72°W) spanning years 2004-2022 are sourced from the RAPID program (https://rapid.ac.uk/rapidmoc/rapid_data/datadl.php). 12-hour, 20 m gridded profiles are produced via the methods in Ref. 58 Time series data from mooring WB5 is extended past 5000 m using available MicroCAT time series records along the WB5 mooring sourced from the British Oceanographic Data Centre (www.bodc.ac.uk), vertically and zonally extended with spline interpolation58.

Original shipboard hydrographic stations (via a CTD; Conductivity, Temperature, Depth profiling instrument) are shown as dots, the 10 km-gridded shipboard hydrographic profiles are shown as an X. Zone 1 (blue shading) captures the start of the transect at -77°W to -75.5°W, covering the extent of the Deep Western Boundary Current (DWBC) throughflow spanning years 1985–2023. Zone 2 (orange shading) captures the middle of the transect from -75.5°W to -72°W spanning years 1990–2023. Zone 3 (green shading) captures the offshore component of the section from -72°W to -69°W, spanning years 2001–2020. Mooring coverage (and subsequent Pressure Inverted Echo Sounder (PIES) bottom-temperature locations) are shown in blue (orange).

Bottom temperature time series are generated from the WBTS bottom-mounted Pressure Inverted Echo Sounders (PIES; sites A2, B, D, and E; https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/ftp/phod/WBTS/IES/calibrated_bottom_temperature/) located adjacent to the WB2, WB3, WB4, and WB5 moorings, respectively, from 2004 to 2023. Bottom-temperature measurements are precise to 0.0002 °C and are computed and calibrated similarly to the methods used in Refs. 33,35,59 for assessment in the South Atlantic using near-bottom shipboard hydrographic measurements within 5 km of the site to correct the continuous hourly sampled time series.

Salinity anomalies relative to the time-series mean of Cape Cod, Bermuda, and Abaco downstream locations are sourced from the hydrographic datasets of the Line W (https://scienceweb.whoi.edu/linew/index.php), Bermuda Atlantic Time Series (http://bats.bios.edu/data/), and 26.5°N Western Boundary Time Series surveying programs. Hydrographic data from Line W and 26.5°N are geographically constrained (shown in Fig. 4), representing stations within the throughflow of the DWBC22. Salinity anomalies of the Subpolar North Atlantic source region use 1° EN4.2.2 monthly gridded salinity profiles60,61 from 1970 to 2021 (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/en4/) for the central locations of the Labrador Sea (58°N, -50°W), Irminger Sea (60°N, -35°W), and Iceland Basin (58°N, -25°W). Anomalies are computed relative to a 30-year climatological mean of monthly profiles between years 1990 and 2020 based on observation weights. Subpolar EN4 salinity records are validated for accuracy against World Ocean Database high-resolution hydrographic profiles of the deep ocean between years 1970 and 2023 (WOD2362) obtained from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database; refer to Supplementary Note 3: Subpolar EN4 Validation).

Wintertime (December-February) North Atlantic Oscillation indices63 (NAO) are used to compare atmospheric drivers to local salinity changes in the subpolar North Atlantic. Monthly NAO indices were obtained from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/pna/nao.shtml). Monthly NAO indices are decadally averaged (e.g. 1990-2000 represents the 1990s, 2000-2010 represents the 2000s).

26.5°N Zonal Partitioning and Water Mass Definition

The 26.5°N hydrographic line is zonally subdivided into three sections to account for spatial and temporal sampling irregularity (Fig. 5). The NOAA AOML Western Boundary Time Series program (WBTS) began in 2001, taking over from the historical sampling of the NOAA AOML Straits of Florida project beginning in 1985. Early cruises were focused on sampling the core of the DWBC, whereas occupations in recent decades have covered the total extent of the DWBC and extended as far east as -69°W. To achieve a multi-decadal, climatological assessment of the entire hydrographic line, a zonal breakdown and spatial gridding is necessary.

For mean water mass layer assessments across each zone, gridded shipboard hydrographic data are first zonally constrained by the longitudinal range of each defined zone and temporally by the maximum zonal sampling coverage (Zone 1: -77°W to -75.5°W, 1985–2023; Zone 2: -75.5°W to -72°W, 1990-2023; Zone 3: -72°W to -69°W, 2001-2020). Zone 1 captures the equatorward-flowing DWBC64,65,66, spanning 140 km from the continental shelf (20–140 km offshore). Zone 2 captures the middle region of the transect and the opposing northward deep return flow of the Abaco gyre66 (140-490 km offshore), while Zone 3 captures the weaker flow regime offshore of the western boundary and into the ocean interior (490-750 km offshore). Mean zonal (Fig. 6A) and meridional (Fig. 6B) velocity structure show 10 km gridded lowered acoustic doppler current profiler (LADCP) profiles of 10 m-bins collected on WBTS cruises 2002–2018 (https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/ftp/phod/WBTS/Global_Class/) used to divide the line into three zones.

A Zonal (u) and (B) meridional (v) velocity map of the 26.5°N hydrographic line across the three defined zones in a distance coordinate. Distance is shown in kilometers as a distance away from Abaco Island, Bahamas at -77°W. Mean velocities are computed from 10 m-binned, 10 km zonally gridded LADCP (lowered acoustic doppler current profiler) data collected on NOAA Western Boundary Time Series cruises spanning 2002–2018. 10 km gridded shipboard hydrographic stations are shown as black triangles. Neutral density isopycnals (kg m-3; black contours) represent the defined water mass layers across the transect.

Water masses across the 26.5°N section are defined using deep water (>2000 m) mass criteria22, Atlantic historical water mass classifications32, and through an in-depth analysis of 26.5°N shipboard hydrographic profiles throughout the water column (refer to Supplementary Note 1). Water mass layers from the surface ocean to the seafloor are defined based on uniform temperature and salinity changes in neutral density67 (γn, kg m-3) space consistent across all three zones along the hydrographic transect. The defined deep water mass layers of Intermediate, Deep, Abyssal, and AABW are used in this study, refer to Supplementary Note 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1, 2; Supplementary Table 1) for further upper-ocean water mass definition criteria.

The Intermediate layer, defined with constant neutral density isopycnal bounds of γn = 27.87–28.01 kg m-3, resides approximately between 1200–2000 m, and constrains the water masses of Labrador Sea Water (LSW) and Mediterranean Overflow Water (MOW). Prior studies have studied temperature and salinity changes to this layer20,21,22,27, linking the temperature and salinity minima in the late 2000s (~2008, Fig. 1C) to direct changes in water mass formation upstream in the Subpolar North Atlantic 10-15 years prior (i.e. convective formation in the Labrador Sea) based on the propagation of this climate signal to the subtropics at 26.5°N. Although this study focuses on the deep ocean >2000 m, we include this Intermediate layer time series as comparison to the deep ocean observations below 2000 m and to aid in the understanding of propagating subpolar climate signals through this location.

Below the Intermediate layer resides the Deep layer, defined with constant neutral density isopycnal bounds of γn = 28.01–28.10 kg m-3 approximately between 2000–3000 m. The water masses of Northeast Atlantic Deep Water (NEADW) and Iceland-Scotland Overflow Water (ISOW) are constrained within this density layer. The Abyssal layer, defined with the constant neutral density isopycnal bounds of γn = 28.10–28.18 kg m-3, lies approximately between 3000–4500 m and constrains Denmark Strait Overflow Water (DSOW). Between the Abyssal layer and the seafloor lies the AABW layer, constraining Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW, or modified nearshore water masses thereof) at densities greater than γn = 28.18 kg m-3 and >4500 m. AABW has been previously defined near 26.5°N at isotherms lower than 1.8 °C34,35, which coincides with the density definition herein of γn > 28.18 kg m-3.

The gridded shipboard hydrographic profiles across all zones and the continuous 12-hr mooring time series from each mooring location are then isopycnally constrained by the Intermediate, Deep, Abyssal, and AABW layers defined by neutral density (Intermediate: γn = 27.87–28.01 kg m-3; Deep: γn = 28.01–28.10 kg m-3; Abyssal: γn = 28.10–28.18 kg m-3; AABW: γn > 28.18 kg m-3). Constrained shipboard hydrographic profiles are averaged vertically across the respective density layer and longitudinally across each zone to generate mean zone layer averages for all 26.5°N occupations (N = 52). The continuous 12-hour sampled mooring time series from the four mooring locations are averaged vertically across the respective density layer. The continuous 12-hour sampled mooring time series of each water mass layer and the PIES hourly sampled continuous bottom temperature time series are smoothed with a 1-month low-pass filter and compared with water mass layer [near-bottom] mean shipboard hydrographic measurements within ±0.2° of the mooring [PIES] location. Mean hydrographic data are reported in °C per decade (potential temperature) or practical salinity units (PSU, unitless) per decade (salinity) with uncertainties representing the 95% confidence interval. Calibrated hydrographic data fall within the World Ocean Circulation Experiment standard accuracy limits12, ±0.002 °C and ±0.002 PSU, where the statistically significant cooling and freshening observed at 26.5°N are above the shipboard hydrographic sensor (SBE3plus temperature sensor, SBE4 conductivity sensor) detection accuracies. The observed cooling and freshening of the tall mooring temperature and salinity records are statistically significant (at the 95% confidence interval, refer to Supplementary Note 2) and above the tall mooring temperature and salinity (SBE37 MicroCAT) sensor detection accuracies of ±0.002 °C and ±0.002 PSU. Refer to Supplementary Note 2 for the reported trends of the mooring and PIES time series.

Data availability

The 26.5°N hydrographic data used in this study are made available by NOAA AOML at https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/ftp/phod/WBTS/Global_Class/GC_calibrated_data_archive/. Gridded time series of temperature and salinity for the 26.5°N tall mooring array (WB2, -76.74°W; WB3, -76.5°W; WB4, -75.7°W; WB5, -72°W) are sourced from the UK RAPID program (https://rapid.ac.uk/rapidmoc/rapid_data/datadl.php, www.bodc.ac.uk). Bottom temperature time series generated from bottom-mounted Pressure Inverted Echo Sounders (PIES) are made available by NOAA AOML at https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/ftp/phod/WBTS/IES/calibrated_bottom_temperature. Hydrographic datasets of upstream locations used in this study are comprised of the Line W hydrographic program (https://scienceweb.whoi.edu/linew/index.php), the Bermuda Atlantic Time Series program (http://bats.bios.edu/data/), and EN4.2.2 monthly gridded salinity profiles (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/en4/) for the central locations of the Labrador Sea, Irminger Sea, and Iceland Basin. EN.4.2.2 data are © British Crown Copyright, Met Office, 2024, provided under a Non-Commercial Government License http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/non-commercial-government-licence/version/2/. World Ocean Database (WOD23) subpolar salinity profiles were sourced from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database). Monthly NAO indices were obtained from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/pna/nao.shtml).

Code availability

MATLAB was used to process and plot all data, including use of the publicly available Gibbs-SeaWater (GSW) TEOS-10 oceanographic toolbox and the PreTEOS-10 legacy function for computing neutral density (https://www.teos-10.org/preteos10_software/neutral_density.html).

References

Bagnell, A. & DeVries, T. 20th century cooling of the deep ocean contributed to delayed acceleration of Earth’s energy imbalance. Nat. Commun. 12, 4604 (2021).

Bates, N. R. & Johnson, R. J. Acceleration of ocean warming, salinification, deoxygenation and acidification in the surface subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 33 (2020).

Cheng, L. et al. Upper Ocean Temperatures Hit Record High in 2020. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 523–530 (2021).

Cheng, L. et al. Past and future ocean warming. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 776–794 (2022).

Desbruyères, D., McDonagh, E. L., King, B. A. & Thierry, V. Global and Full-Depth Ocean Temperature Trends during the Early Twenty-First Century from Argo and Repeat Hydrography. J. Clim. 30, 1985–1997 (2017).

IPCC, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, et al (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 755. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964 (2019).

Johnson, G. C. & Purkey, S. G. Refined Estimates of Global Ocean Deep and Abyssal Decadal Warming Trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111229 (2024).

Purkey, S. G. & Johnson, G. C. Warming of Global Abyssal and Deep Southern Ocean Waters between the 1990s and 2000s: Contributions to Global Heat and Sea Level Rise Budgets. J. Clim. 23, 6336–6351 (2010).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Acceleration of U.S. Southeast and Gulf coast sea-level rise amplified by internal climate variability. Nat. Commun. 14, 1935 (2023).

Domingues, R., Goni, G., Baringer, M. & Volkov, D. What Caused the Accelerated Sea Level Changes Along the U.S. East Coast During 2010–2015? Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 13367–13376 (2018)

Volkov, D. L. et al. Atlantic meridional overturning circulation increases flood risk along the United States southeast coast. Nat. Commun. 14, 5095 (2023a).

Hooper, J. A., Baringer, M. O. & Smith, R. H. Hydrographic measurements collected aboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown, 3 December-18 December: Western Boundary Time Series cruise AB1912 (RB1907). NOAA Data Rep., OAR-AOML 86, 215 (2023).

Vaughan, S. L. & Molinari, R. L. Temperature and salinity variability in the Deep Western Boundary Current. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 749–761 (1997).

Meinen, C. S., Baringer, M. O. & Garzoli, S. L. Variability in Deep Western Boundary Current transports: Preliminary results from 26.5°N in the Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L17610 (2006).

Meinen, C. S. et al. Variability of the Deep Western Boundary Current at 26.5°N during 2004-2009. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 85, 154–168 (2013).

Johns, W. E. et al. Towards two decades of Atlantic Ocean mass and heat transport at 26.5°N. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 20220188 (2023).

Frajka-William, E. et al. Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: Observed transports and variability. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 260 (2019).

Volkov, D. L. et al. The state of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 104, S173–S176 (2023b).

Le Bras, I. & A-A Labrador sea water spreading and the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 20220189 (2023).

Molinari, R. L. et al. The arrival of recently formed Labrador Sea Water in the Deep Western Boundary Current at 26.5°N. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 2249–2252 (1998).

van Sebille, E. et al. Propagation pathways of classical Labrador Sea water from its source region to 26°N. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C12027 (2011).

Chomiak, L. N., Yashayaev, I., Volkov, D. L., Schmid, C. & Hooper, J. A. Inferring Advective Timescales and Overturning Pathways of the Deep Western Boundary Current in the North Atlantic through Labrador Sea Water Advection. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2022JC018892 (2022).

Andres, M., Muglia, M., Bahr, F. & Bane, J. Continuous flow of upper Labrador Sea Water around Cape Hatteras. Sci. Rep. 8, 4494 (2018).

Biló, T. C. & Johns, W. E. Interior pathways of Labrador Sea Water in the North Atlantic from the Argo perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 3340–3348 (2019).

Bower, A. S., Lozier, S. M., Gary, S. F. & Boning, C. W. Interior pathways of the North Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Nature 459, 243 (2009).

Bower, A., Lozier, S. & Gary, S. Export of Labrador Sea Water from the Subpolar North Atlantic: A Lagrangian perspective. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 58, 1798–1818 (2011).

Chomiak, L., Volkov, D. & Schmid, C. The interior spreading story of Labrador Sea Water. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1270463 (2023).

Curry, R., McCartney, M. & Joyce, T. Oceanic transport of subpolar climate signals to mid-depth subtropical waters. Nature 391, 575–577 (1998).

Le Bras, I. A., Yashayaev, I. & Toole, J. M. Tracking Labrador Sea Water property signals along the Deep Western Boundary Current. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 5348–5366 (2017).

Petit, T., Lozier, M. S., Rühs, S., Handmann, P. & Biastoch, A. Propagation and transformation of upper North Atlantic Deep Water from the subpolar gyre to 26.5°N. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 128, e2023JC019726 (2023).

Toole, J. M. et al. Transport of the North Atlantic deep western boundary current about 39°N, 70°W: 2004–2008. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 58, 1768–1780 (2011).

Talley, L. D., Pickard, G. L., Emery, W. J. & Swift, J. H. Descriptive Physical Oceanography: An Introduction. Academic Press. (2011).

Meinen, C. S., Perez, R. C., Dong, S., Piola, A. R. & Campos, E. Observed ocean bottom temperature variability at four sites in the Northwestern Argentine basin: Evidence of decadal deep/abyssal warming amidst hourly to interannual variability during 2009–2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089093 (2020).

Frajka‐Williams, E., Cunningham, S. A., Bryden, H. & King, B. A. Variability of Antarctic bottom water at 24.5°N in the Atlantic. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007168 (2011).

Biló, T. C., Perez, R. C., Dong, S., Johns, W. & Kanzow, T. Weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation abyssal limb in the North Atlantic. Nat. Geosci. 17, 419–425 (2024).

Johnson, G. C., Purkey, S. G. & Toole, J. M. Reduced Antarctic meridional overturning circulation reaches the North Atlantic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L22601 (2008).

Purkey, S. G. & Johnson, G. C. Global Contraction of Antarctic Bottom Water between the 1980s and 2000s. J. Clim. 25, 5830–5844 (2012).

Yashayaev, I. Hydrographic changes in the Labrador Sea, 1960–2005. Prog. Oceanogr. 73, 242–276 (2007).

Dickson, B. et al. Rapid freshening of the deep North Atlantic Ocean over the past four decades. Nature 416, 832–837 (2002).

Yashayaev, I. Intensification and shutdown of deep convection in the Labrador Sea were caused by changes in atmospheric and freshwater dynamics. Nat. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 156 (2024).

Yashayaev, I., van Aken, H. M., Holliday, N. P. & Bersch, M. Transformation of the Labrador Sea water in the subpolar North Atlantic. Geophysical Research Letters, 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031812 (2007).

Curry, R., Dickson, B. & Yashayaev, I. A change in the freshwater balance of the Atlantic Ocean over the past four decades. Nature 426, 826–829 (2003).

Dickson, R. R., Meincke, J., Malmberg, S.-A. & Lee, A. J. The “Great Salinity Anomaly” in the Northern North Atlantic 1968-1982. Prog. Oceanogr. 20, 103–151 (1988).

Holliday, N. P. et al. Reversal of the 1960s to 1990s Freshening Trend in the Northeast North Atlantic and Nordic Seas. Geophysical Research Letters, 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL032675 (2008).

Sarafanov, A., Mercier, H., Falina, A. & Sokov, A. Cessation and Partial Reversal of Deep Water Freshening in the Northern North Atlantic: Observation-Based Estimates and Attribution. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 62, 80–90 (2009).

van Aken, H. M. & de Jong, M. F. Hydrographic Variability of Denmark Strait Overflow Water Near Cape Farewell with Multi-Decadal to Weekly Time Scales. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Pap. 66, 41–50 (2012).

Yashayaev, I. & Seidov, D. The Role of the Atlantic Water in Multidecadal Ocean Variability in the Nordic and Barents Seas. Prog. Oceanogr. 132, 68–127 (2015).

Desbruyères, D. G. et al. Warming-to-Cooling Reversal of Overflow-Derived Water Masses in the Irminger Sea During 2002–2021. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098057 (2022).

Wu, P. & Wood, R. Convection Induced Long Term Freshening of the Subpolar North Atlantic Ocean. Clim. Dyn. 31, 941–956 (2008).

Häkkinen, S. An Arctic Source for the Great Salinity Anomaly: A Simulation of the Arctic Ice-Ocean System for 1955–1975. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 98, 16397–16410 (1993).

Houssais, M.-N., Herbaut, C., Schlichtholz, P. & Rousset, C. Arctic Salinity Anomalies and Their Link to the North Atlantic During a Positive Phase of the Arctic Oscillation. Prog. Oceanogr. 73, 160–189 (2007).

Li, H. & Fedorov, A. V. Persistent Freshening of the Arctic Ocean and Changes in the North Atlantic Salinity Caused by Arctic Sea Ice Decline. Clim. Dyn. 57, 2995–3013 (2021).

Fox, A. D. et al. Exceptional Freshening and Cooling in the Eastern Subpolar North Atlantic Caused by Reduced Labrador Sea Surface Heat Loss. Ocean Sci. 18, 1507–1533 (2022).

Holliday, N. P. et al. Ocean Circulation Causes the Largest Freshening Event for 120 Years in Eastern Subpolar North Atlantic. Nat. Commun. 11, 585 (2020).

Biló, T. C., Straneo, F., Holte, J. & Le Bras, I. A.-A. Arrival of New Great Salinity Anomaly Weakens Convection in the Irminger Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098857 (2022).

Devana, M. S., Johns, W. E., Houk, A. & Zou, S. Rapid Freshening of Iceland Scotland Overflow Water Driven by Entrainment of a Major Upper Ocean Salinity Anomaly. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094396 (2021).

Fried, N. et al. Recent Freshening of the Subpolar North Atlantic Increased the Transport of Lighter Waters of the Irminger Current from 2014 to 2022. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 129, e2024JC021184 (2024).

Cunningham, S. A. et al. Temporal variability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation at 26.5°N. Science 317, 935–938 (2007).

Tracey, K. L., Donohue, K. A. & Watts, D. R. Bottom Temperatures in Drake Passage. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 47, 101–122 (2017).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Gouretski, V. & Reseghetti, F. On depth and temperature biases in bathythermograph data: Development of a new correction scheme based on analysis of a global ocean database. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Pap. 57, 812–833 (2010).

Mishonov, A. V. et al. World Ocean Database 2023. C. Bouchard, Technical Ed. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 97. https://doi.org/10.25923/z885-h264 (2024).

Hurrell, J. W., Kushnir, Y., Ottersen, G. & Visbeck, M. An overview of the North Atlantic Oscillation. The North Atlantic Oscillation: Climate Significance and Environmental Impact. Geophys. Monogr., Am. Geophys. Union 134, 1–35 (2003).

Johns, W. E. et al. Variability of Shallow and Deep Western Boundary Currents off the Bahamas during 2004–05: Results from the 26°N RAPID–MOC Array. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 38, 605–623 (2008).

Johns, W. E. et al. Continuous, Array-Based Estimates of Atlantic Ocean Heat Transport at 26.5°N. J. Clim. 24, 2429–2449 (2011).

Biló, T. C. & Johns, W. E. The Deep Western Boundary Current and Adjacent Interior Circulation at 24°–30°N: Mean Structure and Mesoscale Variability. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 50, 2735–2758 (2020).

Jackett, D. R. & McDougall, T. J. A Neutral Density Variable for the World’s Oceans. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 237–263 (1997).

Acknowledgements

We gladly acknowledge and thank all members of the ship, technical, science, and collaborating parties that were involved in the collection and processing of the hydrographic data presented in this study. We thank T. Biló for his efforts generating the 26.5°N PIES bottom temperature record used in this study. The WBTS Project is supported by the NOAA Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing (GOMO) Program (FundRef #100007298) and by NOAA AOML. Data from the RAPID-MOCHA program are funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant OCE-2148723 and by the U.K. Natural Environment Research Council. L. Chomiak was supported by the U.S. Global Oceans Shipboard Investigations Program (U.S. GO-SHIP) research fellowship under NSF grant OCE-2023545. D. Volkov was supported through the NOAA AOML Deep Temperature (DeepT) project by the NOAA Climate Program Office, Climate Observations and Monitoring, and Climate Variability and Predictability programs (grant number NA20OAR4310407). This research was supported by the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science and by NOAA AOML, and it was carried out in part under the auspices of the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, a Cooperative Institute of the University of Miami and NOAA, cooperative agreement #NA20OAR4320472.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Chomiak conceptualized and designed the work, performed data analysis, interpretation, and visualization, and prepared the manuscript. D. Volkov contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revisions. W. Johns contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revisions. J. Hooper V contributed to acquisition and calibration of the 26.5°N hydrographic data and contributed to manuscript revisions. R. Smith contributed to acquisition and calibration of the 26.5°N hydrographic data and contributed to manuscript revisions. All authors have contributed to the sea-going collection of 26.5°N data and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Weiqing Han and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chomiak, L.N., Volkov, D.L., Johns, W.E. et al. Deep ocean cooling and freshening from Subpolar North Atlantic reaches Subtropics at 26.5°N. Commun Earth Environ 6, 235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02170-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02170-y