Abstract

Kinematic constraints on faults with slow slip rates often diverge, obscuring their neotectonic significance and seismic hazards. The Tuz Gölü Fault Zone (TGFZ) is a major slow-moving fault accommodating intraplate deformation within Central Anatolia, for which long-term geological and short-term geodetic deformation rates disagree. Here, the Pleistocene–Recent kinematic evolution of the TGFZ is determined by dating dissected lava flows of the Hasandağ stratocone. Combined zircon U-Th and (U-Th)/He ages indicate emplacement between 151 ± 6 ka and 38.8 ± 2.0 ka (2σ uncertainties). Restoring flow levees as tie points across fault scarps yields vertical displacement rates of 0.90 ± 0.06 to 1.23 ± 0.08 mm/a for the most reliable projections, whereas in contrast to previous notions only negligible dextral strike slip at 0.01 ± 0.08 to 0.06 ± 0.08 mm/a is permitted. Predominantly normal faulting without a major strike-slip component for the TGFZ supports ongoing east-west extension without the requirement for shearing due to north-south shortening of Central Anatolia between its bounding megashears as it gradually escapes westward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The kinematics of active faults are critical for assessing neotectonic deformation and forecasting the magnitude and recurrence of earthquakes1, but the sense of motion and rates derived from satellite observations over decadal timescales often disagree with those generated by restoring offset geological features2. Offset volcanic deposits formed by recurrent volcanic eruptions offer unique opportunities for determining fault displacement at high-temporal resolution if they can be reliably dated3,4,5,6,7. This, however, is often frustrated by a lack of suitable materials (e.g., charcoal for 14C dating) or inherent limitations of the chronometers (e.g., 40Ar/39Ar geochronology of low-K phases).

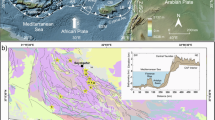

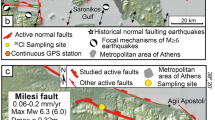

Crustal kinematics affecting the Anatolian plateau are controlled by the interaction of three major lithospheric plates (Africa, Arabia, and Eurasia), causing the Anatolian plate to escape westward from the Arabian-Eurasian collision towards a retreating megathrust where the African plate subducts underneath the Aegean Sea8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 (Fig. 1). Fast movement along the bounding North and East Anatolian megashears generates large-magnitude earthquakes, but also the interior of the Anatolian plateau experiences uplift and deformation that remains poorly understood because of slow deformation, protracted seismic recurrence intervals, and burial of fault structures by young sediments16,17. The Central Anatolian neotectonic region is transitional between N-S shortening and N-S stretching prevailing in the eastern and western Anatolian tectonic provinces, respectively (Şengör and Yazıcı14, and references therein). It is also the focus of widespread Neogene–Quaternary volcanism which correlates with an intracrustal (at ~15–20 km depth) low velocity zone interpreted as crustal magma reservoirs18. The ~200 km long NW-SE oriented Tuz Gölü Fault Zone (TGFZ) in Central Anatolia (Fig. 1) delimits these central and western tectonic provinces by separating the Tuz Gölü basin in the west, which has developed in an extensional regime possibly since the Pliocene19,20,21, from the exhumed Cretaceous metamorphic and plutonic rocks of the Central Anatolian Crystalline Complex (a.k.a. Kirşehir Block) with its Neogene–Quaternary cover in the east22. Reliably reconstructing displacement along the TGFZ is, therefore, pivotal for constraining the boundary conditions of continental crustal deformation in a lithosphere-scale tectonic escape structure.

A Tectonic overview map of Anatolia with major fault systems and B map of the investigated area and active Tuz Gölü Fault Zone (TGFZ) on a digital elevation model64,65. Active faults including North and East Anatolian Fault Zones (NAFZ and EAFZ, respectively) and the Ecemiş Fault Zone (EFZ) are from the Earth Sciences Map Portal (ESMP) of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (http://yerbilimleri.mta.gov.tr); trench location, and fault plane solution for the 2011 Ataköy earthquake from Kürçer and Gökten25.

Offset marker horizons across the TGFZ, including the c. 5.2 Ma Kızılkaya ignimbrite23, yield integrated vertical displacement rates along different fault segments (named after Emre et al.24) of 0.08–0.13 mm/a (Koçhisar and Acıpınar, northern), 0.05 mm/a (Helvadere, south-central), and 0.07–0.13 mm/a (Bor, southern25,26), with potentially along-strike variations in the long-term uplift history27,28. At the younger end of geological constraints, paleoearthquakes have been identified by trenching along the Helvadere segment (Fig. 1). With ages of ca. 10 and 5.3 ka, these paloseismic events suggest integrated vertical movement at ~0.04–0.053 mm/a25. The same authors suggested predominantly normal faulting with a right-lateral strike-slip component from striation analysis on exposed scarps of the TGFZ25, although displacement rates were not quantified (Supplementary Note 1).

In contrast to these geological indicators, some geodetic models predict predominantly right-lateral strike-slip at 1.8–4.7 mm/a along the TGFZ17,29,30, whereas others infer left-lateral motion at 7.2–7.6 mm/a, which, however, was deemed geologically unmeaningful31. Using similar approaches, normal slip rates of 1.2–2.0 mm/a were modeled by Aktuğ et al.29 and Gezgin et al.30, but disputed by Özbey et al.17, who proposed that an ancestral thrust fault kinematically transitioned into right-lateral strike-slip along the TGFZ during the Pliocene. Because of infrequent seismic activity along the TGFZ, focal mechanisms are rarely determined, but normal faulting with a right-lateral strike-slip component was inferred for the 13 June 2011 Ataköy earthquake25 (Fig. 1). Without new field data and high-temporal resolution geochronology, especially for previously unstudied offset markers dating from the critical interval between the Miocene and recent, this impasse between conflicting constraints from geological and geodetical observations remains unresolved.

Here, we investigate lava flows from Hasandağ volcano, Central Anatolia, which have been mapped as ponding against, overtopping, and later being dissected by the scarp of the TGFZ32,33,34,35. Previously, 120 m vertical offset36 and 3.5 km dextral displacement were postulated for these flows37, but limited and, in part, conflicting emplacement ages have thus far prevented quantification of any rates38,39. By combining zircon U-Th-Pb and (U-Th)/He geochronology (Zircon Double-Dating, ZDD) for four lava flows from eastern Hasandağ, where they erupted across the trace of the TGFZ, we overcome the lack of robust ages for these flows and reinterpret earlier kinematic assessments. Restoration of the lava flow topography across the fault yields internally consistent dip-slip and strike-slip rates for this segment of the TGFZ for the Pleistocene–Recent period, which challenges existing geodetic models for plateau deformation associated with the westward escape of the Anatolian plate.

Results and discussion

Lava flow correlations and dating

Four lava flows named F1 to F4 from N–S were sampled (Fig. 2). These are of calc-alkaline intermediate composition typical for Hasandağ with SiO2 abundances between 60.4 and 66.5 wt% for F1, 2, and 4 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 1–2 and Supplementary Data 1). Only F3 has comparatively lower SiO2 of 56.6–57.6 wt% and is more fine-grained (Fig. 3). This chemical similarity precludes correlation across the TGFZ except for F3, especially as mafic enclaves abundant in the lava matrix cause minor compositional variability within individual flows. Mineral components in these lavas include predominantly phenocrystic plagioclase, with lesser olivine (Fig. 4A), clinopyroxene, and Fe-Ti oxide (Supplementary Table 1). Amphibole and biotite phenocrysts are present in F1, 2, and 4, but generally display different degrees of breakdown, which is nearly complete in F3 (Fig. 4B, C). Quartz is rare, and where present, it is often embayed and displays ocellar textures, indicating disequilibrium and reaction with the melt (Fig. 4D). Apatite and zircon are ubiquitous accessory minerals. Minor chemical components in amphibole and biotite are often used for correlation in tephrochronology40, but as with the whole-rock compositions, no clear distinction between the lava flows based on amphibole and biotite compositions alone is possible because of a similar compositional range within individual samples compared to the entire population (Fig. 5). This is likely due to pre-eruptive magma mixing where amphibole and biotite were repeatedly recycled from a long-lived magma reservoir which became repeatedly activated by influx of hot, mafic recharge.

A Skeletal olivine in flow F4; B breakdown textures of amphibole in flow F2; C Breakdown texture of biotite in flow F1; D quartz with ocellar reaction rim in flow F3. Mineral abbreviations are based on Whitney and Evans68.

A, B MnO vs. TiO2 diagrams for amphibole and biotite from flow F1; C, D from flow F2; and E, F from flow F4. Amphibole and biotite are severely affected by the breakdown in F3, so they could not be analyzed. The gray field shows the compositional range for amphibole and biotite for all three samples.

Robust correlation is therefore only feasible using zircon crystallization and eruption ages inferred from U-Th and (U-Th)/He dates, respectively (Fig. 6). Zircon U-Th ages define characteristic spectra for which (1) similarity (Kolomogorov-Smirnov probability p, where the null hypothesis of identical populations is accepted when p > 0.05) and (2) the youngest zircon age populations41 are compared. For F1 sampled west of the TGFZ (previously analyzed by Friedrichs et al.42), zircon U-Th ages overlap at high probability (p = 1.0) with those of a sample from the eastern flank. Both also reveal identical youngest crystallization ages (\({58}_{-17}^{+21}\) and \({59}_{-22}^{+27}\) ka, respectively; all errors 2σ). The same holds for samples from F2 (p = 0.47–0.90; youngest ages \({131}_{-35}^{+51}\) and \({165}_{-60}^{+142}\) ka). F3, already standing out by its more mafic composition, also displays indistinguishable zircon U-Th ages on both sides of the fault (p = 1.0; youngest ages \({211}_{-49}^{+91}\) ka and \({246}_{-70}^{+246}\)), which is also the case for F4 (p = 0.88–0.93; youngest ages = \({243}_{-84}^{+\infty }\) and \({292}_{-105}^{+\infty }\) ka). In each flow, (U-Th)/He eruption ages are always younger than the youngest zircon U-Th ages, consistent with crystallization predating eruption (Fig. 6). (U-Th)/He ages also overlap across both sides of the fault, which, when combined, yield the following averages: 38.8 ± 2.0 ka (F1), 90.8 ± 3.2 ka (F2), 143 ± 8ka (F3), and 151 ± 6 ka (F4) (Supplementary Table 2).

This figure presents single grain (U-Th)/He cooling ages with average values (top panels) and U-Th crystallization ages with the youngest population indicated (bottom panels) for F1–F4. A, B show the data for lava flow F1, C, D present the data for lava flow F2, E, F illustrate the results for lava flow F3, and G, H display the results for lava flow F4, with corresponding eruption and crystallization ages; A, C, E, and G are for flows west of the TGFZ, and B, D, F, and H for corresponding lobes east of the TGFZ. Error bars represent 1σ uncertainties; average and youngest ages are shown with 2σ uncertainties. U-Th ages in secular equilibrium are plotted at 350 ka. Correlative U-Pb ages for secular equilibrium zircon crystals range between 204 and 476 ka (only analyses with >50% radiogenic 206Pb).

Available hornblende and biotite 40Ar/39Ar ages for F1, F2, and F438 are generally older than ZDD ages determined here (Supplementary Table 2). This likely reflects the presence of extraneous 40Ar within hydrous silicate minerals such as biotite, which is a well-known complication for dating young volcanic rocks in continental environments43. In the case of F4, the hornblende 40Ar/39Ar age of 1480 ± 80 ka38 violates stratigraphic constraints as F4 overlies pyroclastic deposits dated by zircon U-Pb geochronology at 339 ± 50 ka44. For F3, two comparatively imprecise whole-rock 40Ar/39Ar ages (integrated ages of 130 ± 50 ka and 180 ± 50 ka for ~90% of cumulative 39Ar released38) broadly agree with the ZDD age of 143 ± 8 ka reported here. A K-Ar age of 84 ± 4.4 ka attributed to F3 (sample CKUZ-DM-10 in Kuzucuoğlu et al.39), however, is inconsistent with these results, but this age is ambiguous as the sample is described as dacitic whereas F3 is a basaltic andesite. Similarly, the groundmass K-Ar age of 99 ± 4.4 ka for the eastern lobe of F4 could not be reproduced. This rock was described as a trachytic basalt (CKUZ 97/8-05 in Kuzucuoğlu et al.39), whereas our compositional data indicate that F4 is dacitic in composition.

Morphologic interpretation and offset quantification

Lava flow morphology was evaluated using a digital elevation model (DEM) and visible near infrared (VNIR) imagery for the area where the TGFZ cuts through explosive and effusive deposits on the northeast flank of Hasandağ (Figs. 2, 7, 8, and 9). Volcaniclastic deposits in the hanging wall generally slope down from the Hasandağ edifice towards the fault, although the average slope is interrupted by effusive deposits, creating highly irregular topography up to the colluvial wedge at the base of the fault. Past the southwest-facing TGFZ scarp, volcaniclastic and flow deposits37 continue to slope down to the northeast. Due to blocky fracturing of the dissected lava flows and talus cover, pristine fault features (e.g., striae) are generally absent. One exception is bleached F2 lava indicative of locally intense hydrothermal alteration35 where dip-parallel slickenlines were observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fault morphology is, therefore, the main observable, but this has been partly obscured by scarp-derived talus and fault-parallel sediment transport leading to variable colluvial wedge accumulation along the base of the scarp. Moreover, the footwall has retreated irregularly by block fall and gully erosion for parts of the TGFZ where the scarp contains or is topped by competent rocks, such as lava flows F1–4. The lateral extent of the lava flows was mapped using VNIR and morphological analysis of the DEM (i.e., surface curvature; Fig. 8); levees identified for F2–4 were used as tie points to reconstruct the original lava flow geometry and slope across the hanging wall and footwall blocks (Figs. 8 and 9). Tie point separation, local fault angle, and the bearing between tie points used for displacement calculations are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

A Southeast-directed view over lava flow F4 draining into the Ulukışla vent structure. Overtopping of the pre-existing fault scarp occurred in a gap between high points on the fault scarp. B Northwest directed view over subsequently emplaced flows F3, F2, and F1. Note the absence of a visible scarp on the youngest flow F1 (see text).

VNIR images (A, E, I), DEM curvature (2nd derivative of elevation) highlighting convex surface features such as lava flow levees, compression ridges, and fault scarp filtered to show values > 0.04 with isolated areas <25 m2 filtered out (B, F, J). Lava flow maps (including colluvium on the hanging wall, excluding erosion zones on the footwall) and piercing points on the hanging wall and footwall lobes (C, G, K). Restored (along a 60° fault plane) lava flows at the time of emplacement (inferred from ZDD ages; D, H, L). Source of DEM as in Fig. 2. Solid fault lines indicate the location of fault projected through colluvium. A dotted buried fault line indicates mass wasting or volcanic deformation of the fault, introducing additional ambiguity of fault location.

Surface profiles for F2–4 lava flows before (A, C, E) and after restoration (B, D, F). Elevation in meters above sea level (m a.s.l.) plotted against horizontal distance from fault. Cross-sections are shown for a 60° fault dip; an apparent dip due to the oblique intersection of levees and the fault in profiles in A and E is indicated; only for F3, which is cut perpendicular to the TGFZ, is a 30° fault plane close to the present-day morphology included. Point c corresponds to the boundary between the lava flow surface and the colluvial wedge at the base of the fault scarp. Point e represents the edge of the erosional scarp towards the fault. Midpoint m is halfway between c and e and is used to anchor the original fault plane on the surface profile. Offsets on minor scarps on F4 at +380 and +600 m distance from the fault were disregarded in the reconstruction. Source of DEM as in Fig. 2.

Specific aspects of the reconstruction and the role of pre-existing fault-controlled topography on lava effusion are discussed in chronological order from the oldest (F4) to the youngest lava flows (F1). Upon effusion, the southward flowing F4 lava was initially impounded by the pre-existing TGFZ scarp to the east and presumably the elevated rim of the Ulukışla structure downstream35 (Figs. 2 and 7A). This obstruction possibly caused F4 to pond and ultimately spill over through a low point in the scarp, feeding an eastward flowing lobe. Subsequent deflation left prominent levees on the outer perimeter of F4, but only the northern levee can be correlated across the fault. Fractures that extend from the scarp north of F4 into the footwall lobe are poorly defined and lack obvious offsets in the unconsolidated tephra immediately south. They may preserve early normal faulting or fracturing without through-going offset. An unbreached relay ramp transfers offset between the discontinuous Helvadere and Altunhisar segments of the TGFZ (Fig. 2). Altogether, fault segment termination, possible splaying, the absence of identifiable tie points for the southern levee, and possible post-emplacement doming deforming the northern levee and scarp face complicate F4 restoration. Dip-slip and dextral strike-slip estimates are 110 and 45 m, respectively, for the restoration of piercing points on a reconstructed 60° primary fault scarp (Fig. 9; see Method section for uncertainties). Restoration on a 15° scarp closer to the modern topography yields higher vertical and horizontal displacements at 269 m and 189 m, respectively, but after accounting for fault surface degradation, we deem the 60° estimates more reliable.

Subsequently to F4 emplacement, F3 erupted on top of a series of domes with stacked lava flows that ponded against a pre-existing scarp, and F3 flowed northeast through an established low in the fault scarp with little diversion or ponding (Fig. 7B). F3 levees are well defined on both sides of the flow on the hanging wall and footwall, except where covered by talus. This flow was subsequently offset by a singular fault plane. Restoration of piercing points on the well-defined southern levee crest with a reconstructed fault scarp dip of 60° yields an estimated 129 m dip slip and 1 m dextral strike slip (Fig. 9). The corresponding offsets for the restoration of piercing points projected along the present-day 30° dip of the fault plane are higher at 176 m and 8 m, but still indicate dominant dip slip. As with the F4 flow, rates determined from a reconstructed 60° fault dip are likely more reliable as this accounts for erosive material transfer along the fault plane, but in the absence of firm constraints on fault plane evolution, we consider this range of values as realistically reflecting geological uncertainties in the lava flow reconstruction.

The next youngest flow, F2, flowed towards, and similar to F4, ponded against a pre-existing fault scarp which it overtopped, leaving comparably sized lobes in the hanging and footwall blocks (Fig. 7B). Overlapping short fault splays or major slumping on a single fault trace separate the eastern lobe of F2 from the hanging wall portion. The southern levee on the footwall lobe of F2 is clearly identifiable. On the hanging wall, a marked southern levee in the upper part of the flow is partially buried by sediment fill that ponded against the scarp. However, field observations support that a low ridge emerging from the sediment is the continuation of the levee, and hence a correlative to the levee on the south side of the footwall lobe (Fig. 2). For a reconstructed 60° fault plane dip, we obtained a dip-slip displacement of 102 m, whereas the strike-slip component is sinistral with a displacement of 43 m (Figs. 8 and 9). For a 30° fault dip, retro-deforming F2 according to the time-adjusted movement of F3 restores the opposing ridgelines, supporting their identification as the original southern levee for F2.

No prominent scarps are identified in the youngest flow F1 (Fig. 7B). This apparent absence of fault scarps in the morphologically youngest flow that erupted over the trace of the TGFZ may indicate deceleration of normal faulting after emplacement of F1. However, the predicted ~47 m vertical offset projected into F1 could go undetected due to lack of coverage by high-resolution DEM data (Fig. 2), fault splaying or ramping, strong lava flow topography, or dense vegetation. In the absence of better kinematic indicators that cover fault evolution after emplacement of F1, we cannot resolve whether the TGFZ experienced spatially or temporally restricted episodes of variable dip slip along the studied segments.

Piercing point projections and offset calculations derived based on the current local fault dip for each lava flow (~15°–30°) are weighted less than the preferred reconstruction for a fault plane originally dipping at 60°. This is based on outcrop measurements with slip indicators elsewhere along the TGFZ25, acknowledging that direct fault plane measurements were impossible due to the blocky disintegration of the dissected flows. Combining the morphological restoration of Middle–Upper Pleistocene lava flows with the ZDD ages yields integrated dip-slip rates of 0.73–1.78 mm/a with a best-fit value of 0.90 ± 0.06 mm/a based on the reconstruction of the F3 southern levee for a fault dip of 60°(Fig. 8). Dextral strike-slip is as low as 0.01 ± 0.08 mm/a based on the F3 southern levee piercing points for a fault dip of 60°. Corresponding rates for 30° fault dip across F3 of 1.23 ± 0.08 and 0.06 ± 0.08 mm/a for dip-slip and dextral strike-slip motion, respectively, are only marginally different. The net slip direction is S 47° W. The higher and opposite sense reconstructions for F2 and F4 (Table 1) reflect uncertainties in piercing point projections to the fault plane, but vertical displacement rates overlap with those derived from F3. Net slip directions are S 12° W and N 76° W, respectively. Importantly, dip-slip rates derived from lava flow restorations always significantly exceed the corresponding strike-slip rates (Table 1).

Deformation of the Anatolian Plate along the Tuz Gölü Fault since the Pleistocene

The TGFZ and the associated Tuz Gölü basin, presently filled with a landmark dry lake, record a protracted tectonic history of this part of the Anatolian plateau throughout the Cenozoic45. Here, we discuss its neotectonic deformation in the realm of escape tectonics following Arabian plate indentation into Eurasia13,46. Neotectonic models for Central Anatolia based on geodetic data invoke lateral dissection along transform faults where the TGFZ and the adjacent Ecemis fault zone act as conjugated dextral and sinistral strike-slip fault systems in response to N-S compression47. In addition, geomorphological and fault structural studies emphasize normal faulting with a dextral strike-slip component for the active TGFZ in an extensional setting21,25,27,28. Field evidence supporting normal faulting (e.g., slickenline orientations), however, has been questioned as being unreliable, or only of local relevance17.

The first-order result of our displacement analysis of Hasandağ lava flows dissected by the TGFZ is that strike-slip deformation is minimal (cf.Aydar and Gourgaud37). This is most obvious for F3, where the flow direction was nearly perpendicular to the fault. The influence of the pre-existing fault morphology on channeling the F2 and F4 flows creates larger uncertainties for piercing point reconstructions, but even these less certain reconstructions are at odds with geodetic-based kinematic models for the TGFZ arguing for pure dextral strike slip at a rate of ~3 mm/a17. In all cases, applying a lateral displacement rate of 1–3 mm/a17 would retrodeform correlated lava flows on the footwall and hanging wall blocks of the TGFZ by ~40–120 m (F1) and up to 150–450 m (F4) into unreasonable configurations. Kinematic models for the TGFZ also estimated dip-slip rates of 1.2–2 mm/a that are consistent with those determined here, but these models also predict dextral strike slip at equivalent or even faster rates29,30 which again is not supported by any of the lava flow reconstructions presented here. Moreover, the apparent ~43 m sinistral offset of F2 should also affect F3, which is, however, not observed, supporting our assessment that lateral offsets for F2 and F4 are likely due to uncertainties in piercing point locations, which are obfuscated by the oblique direction of the flow lobes relative to the fault.

Before extrapolating the results from our displacement analysis, it is critical to address whether minimal or absent dextral strike-slip faulting at Hasandağ was a local phenomenon only. If horizontal motion prevailed elsewhere along the TGFZ, then the transition from dip slip at Hasandağ to strike slip elsewhere would require widening of the fault zone and block rotation to accommodate the change in principal motion vectors48. This, however, is nowhere observed in the vicinity of Hasandağ, or for that matter, elsewhere along the TGFZ, which instead displays remarkable linearity with a morphologically nearly continuous scarp over all segments17. Fault striation analysis on other segments also supports normal faulting along the entire TGFZ25, fully consistent with our findings. In consequence, attributing field indicators for normal faulting along the TGFZ to local diversion of the stress field17 falls short in explaining the absence of any major dextral displacement of the Hasandağ lava flows along the TGFZ.

The vertical displacement rates derived from offset Hasandağ lava flows exceed rates based on Pliocene marker horizons and paleoseismic trenching in the northern part of the Helvadere segments25. Accelerated uplift from the northern segments of the TGFZ towards Hasandağ has been previously inferred27, but not to the extent required to match fast vertical displacement rates determined here. This begs the question if TGFZ segments straddling Hasandağ are anomalous compared to other segments. Normal faults adjacent to a volcano can relocate toward the load of a volcanic edifice49. From north to south, the Helvadere segment of the TGFZ bends right towards Hasandağ, and steps left through a relay ramp towards the Altunhisar segment (Fig. 2). A strong impact of volcanic loading on fault slip, however, is dismissed because an ~500 m high scarp on a c. 530 ka rhyolite lava from Keciboyduran44 matches the dip slip reconstructed for the TGFZ adjacent to Hasandağ, whereas crustal loading by the Keciboyduran edifice on the opposite side of the TGFZ should have a diminishing effect. Other potential causes for anomalous fault behavior are magmatic inflation and uplift, but these would likely reduce normal faulting. Conversely, eruptive venting could result in caldera-style down-faulting towards Hasandağ, which is, however, inconsistent with the absence of voluminous pyroclastic deposits postdating F4, and the steady-state effusive activity during the Late Pleistocene where magma evacuation and recharge were largely balanced42.

Importantly, these conclusions are robust only for the Pleistocene–Holocene period that is covered by emplacement ages for the lava flows studied here. For the ancestral TGFZ, a transition from E-W compression and thrust faulting to extension and right-lateral strike-slip motion has been inferred17, although the timing for this transition is debated. Late Miocene surface uplift, a volcanic flare-up including the eruption of the widespread Kızılkaya ignimbrite, and beginning E-W extension within the Anatolian plate interior temporally coincide; this is possibly triggered by the removal of lithospheric mantle after the N-directed subduction of the African plate along the Cyprus Arc stalled50. Diminishing N-S compressive stresses within this plate segment are thus expected, but it remains unclear how much residual N-S contraction the Anatolian plate between its central and western tectonic provinces presently experiences47. The pure normal faulting along the Pleistocene–Holocene TGFZ documented here implies that extension normal to the trace of the fault now predominates. The TGFZ is thus interpreted here as a major structure that principally accommodates E-W extension that is associated with the formation of extended basins in Central Anatolia as the plate is pushed by the colliding Eurasian and Arabian plates further east, while also being pulled towards the extending Aegean Sea in the west46.

Conclusions

Upper Pleistocene lava flows erupted from the Hasandağ stratovolcano between 151 ± 6 ka and 38.8 ± 2.0 ka reveal a time-progressive diminishing of vertical offsets across the TGFZ. F3 lava flow restoration across the fault indicates integrated normal dip-slip rates at 0.90 ± 0.06 to 1.23 ± 0.08 mm/a; other flow reconstructions yield similar vertical displacement rates, always with a much smaller strike-slip component. The insignificance of strike-slip along the TGFZ transcends previous field-based and geodectic modeling studies17,29,30, which inferred normal faulting but lacked the sensitivity and rate constraints that result from our morphological restoration and dating of multiple lava flows dissected by the TGFZ. Unlike strain indicators on faults such as slickenlines that can be affected by local stress fields, the absence of lateral displacement of Hasandağ lava flows over distances of 5–10 km along the TGFZ cannot easily be attributed to localized anomalies (cf. Özbey et al.17). Because the TGFZ is highly linear along strike, these results can also be extrapolated, supporting fault scarp analysis data which indicate predominantly normal faulting elsewhere along the TGFZ, albeit at presently unconstrained rates. Collectively, these data argue against geodetic and tectonic models for modern Central Anatolian crustal deformation that interpret the TGFZ as a predominantly dextral strike-slip system and instead support accommodation of E-W extension without major N-S shortening (cf. Özbey et al.17). Additional research on displacement rates for other segments of the TGFZ is required to resolve potential spatial or temporal acceleration and deceleration in horizontal deformation in proximity to the evolving Hasandağ volcanic system34.

Methods

Mapping and geomorphological analysis

We mapped four lava flows (named F1 to F4 from N–S; Fig. 2), and analyzed the geomorphic expression of faulting in a DEM with 5 m horizontal spacing and 3.4 m vertical resolution (90% confidence interval) derived from airborne photogrammetry provided by the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Defense General Directorate of Mapping as projected geotiff files (WGS84 UTM zone 36 N). File ALAN1 covers part of the Helvedere segment of the TGFZ, a portion of the distal deposits on the north side of Hasandağ, and most of the distal lobe of flow F1, excluding the far eastern part of the lobe. With a small gap, file ALAN2 covers the southern Helvedere and northern Altunhisar segments of the TGFZ, the edifice of Küçük Hasandağ, and its distal southern and eastern deposits, including the source and proximal flow of F1, all but the terminal toes of flows F2 and F3, and the entirety of flow F4. Qualitative surface details and gross compositional variations in deposits were studied utilizing DigitalGlobe, Inc., World View 2 (WV02) panchromatic 50-cm-resolution, and four-band VNIR satellite ~2 m resolution imagery. We analyzed the DEM via topographical profiles and hillshaded topography as implemented in the open-source geographic information system software QGIS.

Fault perpendicular cross sections along the fault were analyzed to reconstruct the position of the tectonic scarp surface, projecting the extent of the capping lava flow on the footwall to the original fault surface, and the extension of the hanging wall surface to the original fault scarp under the colluvial wedge, anchored on the midpoint of high-angle sections half-way across the scarp profile. Because of uncertainties in scarp erosion and colluvial wedge accumulation, piercing point projections and offset calculations were derived both based on the current local fault line scarp dip for each lava flow (~15°–30°), and for a fault plane originally dipping at 60° based on outcrop measurements with slip indicators along the TGFZ25. However, the non-planar nature of the surfaces of the marker lava flows, the pre-existing volcanic topography surrounding and underlying the flows, and the irregular erosion of fault scarps composed of heterogenous layers of coherent lava flows overlying mixed lava flow and volcaniclastic deposits, contribute to the original surface intersections with the projected fault scarp being only approximately located.

Uncertainties in locating unique piercing points include the irregular nature of lava flow emplacement, including flow direction diversion (F2 and F4) and irregular flow surfaces (e.g., flow-perpendicular ogives). Moreover, antecedent fault scarp topography caused channeling and directing of the active lava flows differentially across the fault where the pre-flow surface morphology changed abruptly across the fault, leading to discontinuous lava flow and flow edge morphology across the fault. In addition, there is morphologic evidence for differential surface deflation of the lava flow across the fault during or shortly after emplacement, especially on multi-lobed flows (F2 and F4), causing fault-parallel surface profiles through the lava flows to vary across the fault. Preserved perimeter levees are the primary linear features in the DEM that can be extrapolated to piercing points on the fault plane. Where piercing points can be projected at the intersection of a levee and the fault surface, the direct distance between piercing points across the fault was measured and converted to X, Y, and Z (elevation) dimensions. Hanging wall fault blocks cropped from the DEM along the projected intersection between the hanging wall and the fault scarp, were translated in X, Y, and Z to restore piercing point geometry. The fit of the hanging wall and footwall blocks was analyzed with extracted profiles and visually examined as a hillshade image for obvious contraindications, taking into account erosion gaps and accumulated colluvium. Translation values ΔX, ΔY, and ΔZ were converted into strike-slip and dip-slip components based on the local strike of the fault. Slip rate uncertainties comprise uncertainties from the radiometric dating (<5% relative error) and the resolution of the DEM (5 m horizontal; 3.4 m vertical). In addition, there are systematic uncertainties that are difficult to quantify related to the horizontal accuracy of the DEM and geological ambiguities (e.g., selection of piercing points, mass wasting affecting scarp slope, possible post-faulting volcanic deformation, fault geometry, and orientation). Geological uncertainties are minimal for F3, but the apparent opposite sense of strike-slip motion for F2 and F4 likely results from such ambiguities in piercing point projection. Two fault splays were previously mapped at F4 (http://yerbilimleri.mta.gov.tr); however, the study of the VNIR image and the DEM indicates the strong possibility of coherent layers mid-fault plane causing differential erosion, and post F4 volcanic deformation of the fault plane deforming a single fault, rather than the existence of two short fault splays.

Major element and mineral analysis

For major element determinations, the rock powder was mixed with a melting agent (lithium tetraborate) in a ratio of 1:5, melted in a platinum crucible at ~1050 °C, and poured into a platinum mold to prepare fused tablets. The loss on ignition of the sample was determined in parallel. Trace element determinations were carried out on pressed powder pellets. All measurements were carried out at the Institute of Geosciences, University of Mainz, on a Pananlytical MagiXPro spectrometer with a Rh excitation tube operated at 4 kW (60 kV, 126 mA). Amphibole and biotite compositional data were acquired for selected phenocrysts with interiors away from marginal breakdown textures. Electron Probe Microanalysis (EPMA) was executed using a JEOL SuperProbe JXA-iSP100 equipped with five detectors for wavelength dispersive spectroscopy. Operating conditions include a 15 kV acceleration voltage and 20 nA beam current (which was defocused for biotite, and focused beam for amphibole). Natural and synthetic compounds were used for calibration (Supplementary Data 2 and 3).

Geochronology

Rock samples were processed for ZDD combining U-Th and (U-Th)/He geochronology51 on 17–41 and 9–10 individual crystals per sample, respectively (Supplementary Data 4–6). Zircon crystals were separated from aliquots of the same samples. Per sample, the collected rock samples, barring pieces retained for thin section preparation, were crushed and sieved to extract the fraction between 63 and 200 µm. From this fraction, heavy minerals were hydraulically enriched using a flat plastic pan. Approximately 50 zircon crystals were manually selected under a binocular microscope with polarization filters for each rock sample, preferentially targeting large, euhedral, unbroken, and inclusion-free crystals. Crystals were then pressed into metal holes within an Al disk prepared to contain polished crystals of reference zircon AS3. Unknown zircon crystals from each sample were placed onto the mounts, optically mapped, and an ~ 50 nm conductive Au coat was applied prior to analysis by SIMS. For zircon double-dating51, ion microprobe spots were placed onto pristine crystal faces using U-Th disequilibrium and, in some cases, also U-Pb dating methods. These measurements were conducted by SIMS using the CAMECA IMS 1300-HR3 at Curtin University equipped with a Hyperion H201 radio frequency plasma oxygen ion source. An aperture-delimited 16O- primary beam of ~40 nA was focused onto an ~ 30 µm diameter spot. Isotopes of Th and U were simultaneously detected as oxides in three electron multiplier (EM) detectors (L2, L1, and axial EM), with magnet jumps in the sequence: (1) 232ThO+ (axial EM), (2) 90Zr2O4+ (L2) and 90Zr92ZrO4+ (L1), (3) 244.03 background (L2), 230ThO+ (L1), and 238UO+ (axial EM), and (4) 244.3 background (L2), 246.3 background (L1), and 254.3 background (axial EM). Background-corrected intensities were ratioed, and atomic ratios were calculated using a relative sensitivity factor (RSF) for U-Th calibrated according to Reid et al.52. The 230Th decay constants of Cheng et al.53 were used, and two-point model ages calculated from zircon activity ratios paired with an equipoint composition of 0.797 from Friedrichs et al.54. Reference zircon sufficiently old to be in secular equilibrium (AS3, G3, M257, and OGC) were analyzed in replicate to monitor detector stability and accuracy of the RSF correction. The weighted average of (230Th)/(238U) = 1.011 ± 0.0010 (2σ, MSWD = 0.68, n = 30) agrees with the expected secular equilibrium value of unity. For a subset of zircon crystals dated by U-Th methods, rim analyses were carried out using an instrumental setup for U-Pb geochronology similar to Friedrichs et al.42. Secondary ions were generated using an ~15 nA 16O− primary beam with a spot diameter of ~20 µm and detected in the axial EM with sequential peak jumps from mass 203.5 to 254. Temora 2 reference zircon (n = 13) was used for the U-Pb RSF calibration, and accuracy was monitored by analyzing reference zircon 91500 for which a weighted average 206Pb/238U age of 1067 ± 38 Ma (2σ, MSWD = 0.17, n = 3) was obtained in close agreement with the reported age of 1065 Ma55. Zircon U-Th disequilibrium and, in some cases also U-Pb geochronology results are represented in Supplementary Data 4 and 5, respectively.

Subsequently, zircon crystals were extracted from the In metal, photographed, packed in Nb tubes, and (U-Th)/He ages determined in the John de Laeter Centre Western Australia ThermoChronology Hub (WATCH) Facility following previously described procedures56,57. First, the 4He content was measured by isotope dilution on the Alphachron II instrument. The instrument uses a diode laser to extract 4He together with other gases at ~1250 °C under ultra-high vacuum, which are then cleaned on Ti-Zr getters, and spiked with 99.9% pure 3He gas. The volume of 4He is determined by isotope dilution on a QMG 220 M1 Pfeiffer Prisma Plus mass spectrometer. A “re-extract” was run after each analysis to verify the complete outgassing of the crystal. Helium gas signals were corrected for blank, determined by analyzing empty Nb microtubes interspersed between the unknowns using the same gas extraction procedure. After the He measurements, Nb microtubes containing the crystals were spiked with 235U and 230Th, and dissolved in Parr acid digestion vessels in two cycles of HF, HNO3 (cycle 1), and HCl acids (cycle 2) following the procedures described in Evans et al.58. Sample, blank, and spiked standard solutions were then analyzed by isotope dilution for 238U and 232Th, and by external calibration for 147Sm on an Agilent 7700 ICP-MS. The total analytical uncertainty was calculated as a square root of the sum of squares of uncertainty on He and weighted uncertainties on U, Th, and Sm measurements. The “raw” zircon (U-Th)/He dates were corrected for alpha ejection (Ft correction) after Farley et al.59 whereby homogenous distributions of U, Th, and Sm were assumed for the crystals. The accuracy of the zircon (U-Th)/He dating procedure was monitored by replicate analyses of internal standard Fish Canyon Tuff zircon where crystals measured over the course of this study yielded a mean (U-Th)/He age of 29.1 ± 1.5 Ma (95% confidence interval; MSWD = 0.39; n = 5), in good agreement with the reference (U-Th)/He age of 28.3 ± 1.3 Ma60. The Ft-corrected (U-Th)/He dates were then corrected for U-series disequilibrium61,62 based on U-Th rim analyses of the same zircon. Disequilibrium corrected (U-Th)/He dates, and uncertainties were computed using the software MCHeCalc with goodness of fit parameter Q63 with data summarized in Supplementary Data 6.

Data availability

A preprint version of this manuscript and the data obtained from this study are available on Research Square under the link https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4860492/v1. All data used in this manuscript including whole-rock chemistry, mineral chemistry data, U-Th and (U-Th)/He zircon geochronology data are provided in Supplementary Data 1–6.

References

Youngs, R. & Coppersmith, K. Implications of fault slip rates and earthquake recurrence models to probabilistic seismic hazard estimates Bull Seismol Soc AmV75, N4, Aug 1985, P939–964. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 23, 125–125 (1985).

Rust, D., Korzhenkov, A. & Tibaldi, A. Geologic slip-rate determinations on the Talas-Fergana fault: mismatch with geodetic slip rate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3880–3888 (2018).

Blakeslee, M. W. & Kattenhorn, S. A. Revised earthquake hazard of the Hat Creek fault, northern California: a case example of a normal fault dissecting variable-age basaltic lavas. Geosphere 9, 1397–1409 (2013).

Amos, C. B. et al. Chronology of tectonic, geomorphic, and volcanic interactions and the tempo of fault slip near Little Lake, California. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull 125, 1187–1202 (2013).

Bacon, C. R., Lanphere, M. A. & Champion, D. E. Late quaternary slip rate and seismic hazards of the West Klamath Lake fault zone near Crater Lake, Oregon Cascades. Geology 27, 43–46 (1999).

D’Amato, D. et al. Holocene slip rate variability along the Pernicana fault system (Mt. Etna, Italy): evidence from offset lava flows. GSA Bull. 129, 304–317 (2017).

Oskin, M., Perg, L., Blumentritt, D., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Iriondo, A. Slip rate of the Calico fault: Implications for geologic versus geodetic rate discrepancy in the Eastern California Shear Zone. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, (2007).

Dewey, J. & Sengör, A. M. C. Aegean and surrounding regions: complex multiplate and continuum tectonics in a convergent zone. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 90, 84–92 (1979).

Burke, K. & Sengör, C. Tectonic escape in the evolution of the continental crust. Reflect. Seismol. Continent. Crust 14, 41–53 (1986).

Sançar, T. et al. Geodynamic importance of the strike-slip faults at the eastern part of the Anatolian Scholle: Inferences from the uplift and slip rate of the Malatya Fault (Malatya-Ovacık Fault Zone, eastern Turkey). J. Asian Earth Sci. 188, 104091 (2020).

Şaroğlu, F. & Yilmaz, Y. Doǧu Anadolu’da neotektonik dönemdeki jeolojik evrim ve havza modelleri. Maden Tetk. Ve Aram. Derg. 107, 73–94 (1986).

Şengör, A. C. Mid-Mesozoic closure of Permo–Triassic Tethys and its implications. Nature 279, 590–593 (1979).

Şengör A., Görür N. & Şaroğlu F. Strike-slip faulting and related basin formation in zones of tectonic escape: Turkey as a case study. In: Strike-Slip Deformation, Basin Formation, and Sedimentation 37, https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.85.37.0211 (1985).

Şengör, A. M. C. & Yazıcı, M. The aetiology of the neotectonic evolution of Turkey. Mediterranean Geosci. Rev. 2, 327–339 (2020).

Zabci, C. et al. Internal deformation of continental blocks within converging plates: insights from the Ovacık Fault (Anatolia, Türkiye). Turk. J. Earth Sci. 32, 351–379 (2023).

Okay, A. I. & Göncüoglu, M. C. The Karakaya Complex: a review of data and concepts. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 13, 75–95 (2004).

Özbey, V., Şengör, A. M. C. & Özeren, M. S. Tectonics in a very slowly deforming region in an orogenic belt. Tectonophysics 827, 229272 (2022).

Abgarmi, B. et al. Structure of the crust and African slab beneath the central Anatolian plateau from receiver functions: New insights on isostatic compensation and slab dynamics. Geosphere 13, 1774–1787 (2017).

Fernández-Blanco, D., Bertotti, G. & Ciner, A. Cenozoic tectonics of the Tuz Gölü Basin (Central Anatolian Plateau, Turkey) Turk. J. Earth Sci. 22, https://doi.org/10.3906/yer-1206-7 (2013).

Gürbüz, A. & Kazancı, N. Genetic framework of Neogene–Quaternary basin closure process in central Turkey. Lithosphere 7, 421–426 (2015).

Özsayın, E. et al. Plio-Quaternary extensional tectonics of the Central Anatolian Plateau: a case study from the Tuz Gölü Basin, Turkey. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 22, 5 (2013).

Toprak, V. & Göncüoğlu, M. C. Keçiboyduran-Melendiz fayı ve bölgesel anlamlı (Orta Anadolu). Yerbilimleri Derg. 15, 55–67 (1993).

Aydar, E. et al. Correlation of ignimbrites in the central Anatolian volcanic province using zircon and plagioclase ages and zircon compositions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 213, 83–97 (2012).

Emre, Ö. et al. Active fault database of Turkey. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 16, 3229–3275 (2018).

Kürçer, A. & Gökten, Y. E. Neotectonic-period characteristics, seismicity, geometry and segmentation of the Tuz Gölü fault zone. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 149, 19–68 (2014).

Öztürk, M. Z., Şener, M. F., Şener, M. & Şahiner, E. Tuzgölü Fay Zonu Bor Segmenti’nin Kuvaterner Atım Miktarı. NÖHÜ Müh. Bilim. Derg. 7, 1049–1053 (2018).

Krystopowicz, N. J., Schoenbohm, L. M., Rimando, J., Brocard, G. & Rojay, B. Tectonic geomorphology and Plio-Quaternary structural evolution of the Tuzgölü fault zone, Turkey: implications for deformation in the interior of the Central Anatolian Plateau. Geosphere 16, 1107–1124 (2020).

Yıldırım, C. Relative tectonic activity assessment of the Tuz Gölü Fault Zone; Central Anatolia, Turkey. Tectonophysics 630, 183–192 (2014).

Aktuğ, B. et al. Deformation of Central Anatolia: GPS implications. J. Geodyn. 67, 78–96 (2013).

Gezgin, C. et al. Determination of recent tectonic deformations along the Tuz Gölü Fault Zone in CentralAnatolia (Turkey) with GNSS observations. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 31, 20–33 (2022).

Seyitoğlu, G., Aktuğ, B., Esat, K. & Kaypak, B. Neotectonics of Turkey (Türkiye) and surrounding regions: a new perspective with block modelling. Geol. Acta 20, 1–21 (2022).

Beekman, P. The Pliocene and quaternary volcanism in the Hasan Dağ-Melendiz Dağ region. MTA Bull. 66, 90–105 (1966).

Dhont, D., Chorowicz, J., Yürür, T. & Köse, O. Polyphased block tectonics along the North Anatolian Fault in the Tosya basin area (Turkey). Tectonophysics 299, 213–227 (1998).

Gottsmann, J. & Hedger, E. Investigating stress transfer between the Tuz Gölü fault zone and Hasan Dağ volcano (Turkey). Front. Earth Sci. 9, 732696 (2022).

Ulusoy, İ. et al. Surface expressions of morphostructural features at Hasandağ stratovolcano on DEM datasets. Mediterranean Geosci. Rev. 3, 175–191 (2021).

Toprak, V. Tuzgölü Fay kuşağı Hasandağ kesiminin özellikleri. Türkiye Petrol Jeologları Derneği Özel sayi-Haymana-Tuzgölü-Ulukisla Basenleri Uygulamalari Calisma (Workshop) 71–84 (2000).

Aydar, E. & Gourgaud, A. The geology of Mount Hasan stratovolcano, central Anatolia, Turkey. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 85, 129–152 (1998).

Krystopowicz, N. J. Constraining deformation, uplift, and activity along the Tuz Gölü fault zone, Central Anatolia, Turkey. In: Graduate Department of Earth Sciences). University of Toronto (2015).

Kuzucuoğlu, C. et al. Geomorphology and tephrochronology review of the Hasandağ volcano (southern Cappadocia, Turkey). Mediterranean Geosci. Rev. 2, 185–215 (2020).

Lowe, D. J. Tephrochronology and its application: a review. Quat. Geochronol. 6, 107–153 (2011).

Vermeesch, P. Maximum depositional age estimation revisited. Geosci. Front. 12, 843–850 (2021).

Friedrichs, B. et al. Late Pleistocene eruptive recurrence in the post-collisional Mt. Hasan stratovolcanic complex (Central Anatolia) revealed by zircon double-dating. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 404, 107007 (2020).

Hora, J. M. et al. Volcanic biotite-sanidine 40Ar/39Ar age discordances reflect Ar partitioning and pre-eruption closure in biotite. Geology 38, 923–926 (2010).

Aydın, F. et al. Quaternary bimodal volcanism in the Niğde Volcanic Complex (Cappadocia, central Anatolia, Turkey): age, petrogenesis and geodynamic implications. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 168, 1078 (2014).

Cemen, I., Göncüoglu, M. C. & Dirik, K. Structural evolution of the Tuzgölü basin in Central Anatolia, Turkey. J. Geol. 107, 693–706 (1999).

Whitney, D. et al. Breaking plates: creation of the East Anatolian fault, the Anatolian plate, and a tectonic escape system. Geology 51, 673–677 (2023).

Barka, A. & Reilinger, R. Active tectonics of the Eastern Mediterranean region: deduced from GPS, neotectonic and seismicity data. Ann. Geophys.40, 3 (1997).

Mouslopoulou, V., Nicol, A., Little, T. & Walsh, J. Terminations of large strike-slip faults: an alternative model from New Zealand. Geol. Soc., Lond., Spec. Publ. 290, 387–415 (2007).

van Wyk de Vries, B. & Merle, O. The effect of volcanic constructs on rift fault patterns. Geology 24, 643–646 (1996).

Meijers, M. J. M. et al. Rapid late Miocene surface uplift of the Central Anatolian Plateau margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 497, 29–41 (2018).

Danišík, M. et al. Application of combined U-Th-disequilibrium/U-Pb and (U-Th)/He zircon dating to tephrochronology. Quat. Geochronol. 40, 23–32 (2017).

Reid, M. R., Coath, C. D., Harrison, T. M. & McKeegan, K. D. Prolonged residence times for the youngest rhyolites associated with Long Valley Caldera: 230Th—238U ion microprobe dating of young zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 150, 27–39 (1997).

Cheng, H. et al. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 371-372, 82–91 (2013).

Friedrichs, B., Schmitt, A. K., McGee, L. & Turner, S. U–Th whole rock data and high spatial resolution U–Th disequilibrium and U–Pb zircon ages of Mt. Erciyes and Mt. Hasan Quaternary stratovolcanic complexes (Central Anatolia). Data Brief. 29, 105113 (2020).

Wiedenbeck, M. et al. Three natural zircon standards for U-Th-Pb, Lu-Hf, trace element and REE analyses. Geostand. Newsl. 19, 1–23 (1995).

Danišík, M. et al. Seeing is believing: Visualization of He distribution in zircon and implications for thermal history reconstruction on single crystals. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601121 (2017).

Danišík, M. et al. Sub-millennial eruptive recurrence in the silicic Mangaone Subgroup tephra sequence, New Zealand, from Bayesian modelling of zircon double-dating and radiocarbon ages. Quat. Sci. Rev. 246, 106517 (2020).

Evans, N., Byrne, J., Keegan, J. & Dotter, L. Determination of uranium and thorium in zircon, apatite, and fluorite: application to laser (U-Th)/He thermochronology. J. Anal. Chem. 60, 1159–1165 (2005).

Farley, K., Wolf, R. & Silver, L. The effects of long alpha-stopping distances on (U-Th)/He ages. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 4223–4229 (1996).

Reiners, P. W. Zircon (U-Th)/he thermochronometry. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 58, 151–179 (2005).

Farley, K. A., Kohn, B. P. & Pillans, B. The effects of secular disequilibrium on (U–Th)/He systematics and dating of quaternary volcanic zircon and apatite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 201, 117–125 (2002).

Schmitt, A. K., Stockli, D. F. & Hausback, B. P. Eruption and magma crystallization ages of Las Tres Vírgenes (Baja California) constrained by combined 230Th/238U and (U–Th)/He dating of zircon. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 158, 281–295 (2006).

Schmitt, A. K., Stockli, D. F., Niedermann, S., Lovera, O. M. & Hausback, B. P. Eruption ages of Las Tres Vírgenes volcano (Baja California): a tale of two helium isotopes. Quat. Geochronol. 5, 503–511 (2010).

Danielson, J. J. & Gesch, D. B. Global multi-resolution terrain elevation data 2010 (GMTED2010).). US Geological Survey (2011).

NASA shuttle radar topography mission global 3 arc second [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS land processes distributed active archive center. http://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl3v003/ (2024).

Le Bas, M. J., Le Maitre, R. W., Streckeisen, A. & Zanettin, B. A. A Chemical classification of volcanic rocks based on the total alkali-silica diagram. J. Petrol. 127, 745–770 (1986).

Deniel, C., Aydar, E. & Gourgaud, A. The Hasan Dagi stratovolcano Central Anatolia, Turkey evolution from calc-alkaline to alkaline magmatism in a collision zone. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 87, 275–302 (1998).

Whitney, D. L. & Evans, B. W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 95, 185–187 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Technical support at Heidelberg University by Ilona Fin and Oliver Winand (thin section preparation), Katharina Cionoiu (EPMA), and Alexander Varychev (SEM) is acknowledged. We thank Nora Groschopf for assistance with XRF analyses at Mainz University. The authors are grateful to the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Defense General Directorate of Mapping for providing DEM data. This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBITAK post-doctoral scholarship 2219) to G.G.K. and the Australian National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS). Satellite imagery is copyrighted by DigitalGlobe, Inc., and provided through the Polar Geospatial Center (University of Minnesota–Twin Cities, Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA). The authors thank Neil Krystopowicz for their valuable contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.G.K.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing. J.C.H.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing. L.M.S.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing. M.D.: funding acquisition, geochronological analyses, investigation, methodology, validation, writing. A.K.S.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, geochronological analyses, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Maria Laura Balestrieri and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gençoğlu Korkmaz, G., Harvey, J.C., Danišík, M. et al. Pure dip-slip along the Tuz Gölü Fault Zone accommodates east-west extension of Central Anatolia. Commun Earth Environ 6, 333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02192-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02192-6