Abstract

Around the margins of Antarctica, dense waters formed on the continental shelf are exported to oceanic depths. This overflow of dense waters to the abyss ventilates the ocean, and is vital to the global overturning circulation. Accurately quantifying the variability in the transport of dense waters exported from the Antarctic continental shelf poses substantial challenges, due to the reliance on costly, carbon-emitting, and sparse observations or on models that do not capture complete dynamics. Here, we demonstrate that Antarctic dense water overflows can be monitored from space, using year-round sea surface height observations from satellite altimetry. We employ high-resolution simulations to characterize the sea surface height signature of the dense waters crossing the Ross Sea continental shelf break. This allows us to find a sea surface height proxy that captures the dense water transport variability, even when model outputs are subsampled to the sparse satellite observation coverage. When applied to the existing satellite record, this proxy reveals interannual variability that aligns with changes in dense water properties measured from hydrographic surveys. Our findings suggest that satellite-based monitoring can effectively complement and enhance existing in situ observing systems, by providing long-term and extensive spatial coverage of Antarctic dense water transports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Around the Antarctic margins, dense water formed in coastal polynyas floods the bottom layer of the Antarctic continental shelf1,2, and overflows at the shelf break, typically via glacially-scoured troughs3,4,5,6. The dense water then travels down the steep continental slope as a gravity current, mixing with other water masses on the way to becoming Antarctic Bottom Water7. The resulting abyssal overturning circulation ventilates the deepest layers of the global ocean, and has the potential to sequester heat and carbon from the atmosphere under climate change8,9,10. However, the projected increase in glacial melting and surface warming will likely diminish the formation of dense water around Antarctica11,12,13,14. As the formation of dense water weakens on the Antarctic continental shelf, a reduced volume of lighter dense water overflows, leading to weaker bottom water transport to the ocean abyss15. Long-term observations in East Antarctica16 and the Weddell Sea17 already suggest that a 30% decline of the abyssal overturning circulation may have occurred over the past three decades. Obtained in the deep ocean away from dense water sources, these observations highlight the challenges of monitoring source regions over climatically meaningful periods (years to decades)18. Similarly, modeling studies forecast a reduction in Antarctic Bottom Water transport, by up to 40% over the next 30 years19. Although recent climate conditions appear to have led to some recovery of bottom water properties15,20, the observational time series does not extend far enough back to quantify the full decadal variability in such properties.

Observing dense water formation and export around the Antarctic coast is extremely challenging. Current observations include a few long-term moorings20,21,22,23, sporadic ship-based measurements14,15,24,25, and the occasional use of instrumented marine mammals26 and tracers27,28. While moorings and hydrographic sections provide detailed local descriptions of water mass properties, they are expensive, logistically complex, and spatially localized. For the observation of cascading dense water, the narrowness of overflow troughs poses a risk of partial or complete omission in in situ observations3. There is currently no approach to measure the export of Antarctic Dense Shelf Waters (DSWs) at their sources, over any meaningfully extensive spatial domain, for sufficiently long to capture interannual variability or longer-term trends. Remote sensing-based methods for estimating Antarctic Bottom Water flow offer a promising solution to this challenge18, and could circumvent both the temporal and spatial limitations of other data sources. Here, we propose one such approach, by exploiting a new blend of satellite altimetric observations29 and recent model-generated advances in our dynamical understanding of DSW overflows6. A suite of new techniques in the processing of satellite altimetry data utilize fractures in the sea ice to retrieve accurate measurements of sea surface height (SSH) in regions predominately covered by sea ice29,30,31,32,33. This method is cheap, as it re-processes already existing observations, but provides new information on the ocean dynamics under sea ice, such as mesoscale eddies34 and large-scale ocean currents29,30,31. Here we exploit almost 9 years of along-track SSH observations from multiple satellite altimeters to propose a novel proof of concept, showcased in the Ross Sea, for detecting and monitoring DSW overflows based on their SSH signature in the altimetry data. Using the along track observations instead of the gridded data set allows us to retrieve information in the narrow overflow regions, and avoid being impacted by the smoothing of a mapping process. This allows us to potentially retrieve one observation every few hundred meters (depending on sea ice conditions) instead of using 25 km resolution maps. Unlike previous overflow studies in the North Atlantic in the 2000s35,36, which were limited by altimetry noise37, our approach does not seek to track day-to-day variations in overflow intensity, but rather to assess the potential for long-term monitoring of DSW export from the continental shelf.

In the Ross Sea, DSW flows along three major continental shelf troughs to reach the shelf break, whence it cascades down a steep, roughly 2500 m tall continental slope (Fig. 1a). Overflows take the form of localized, episodic pulses of DSW crossing the shelf break2,5,22. Simulations have shown that these DSW pulses have an imprint on the steric SSH6. Such sporadic plumes can generate cyclonic eddies38,39,40 and topographic Rossby waves41 that may enhance the SSH variability associated with the overflows, making them particularly suitable for altimeter-based monitoring. Prior observational studies in the Ross Sea have focused mainly on overflows from the Drygalski Trough, and utilized moorings to identify important density and volume reductions in the DSW exported from the Ross Sea since the 1990s, followed by a partial recovery in the 2010s, still going in 20203,15,16,22,23. However, these observations are inferred from moorings in single locations, or summer-biased ship transects. Our new method will complement and expand the scope of these in situ observations by offering a significantly expanded temporal and spatial distribution of the observation of DSW export, which will in principle be applicable to monitoring other DSW overflows around Antarctica.

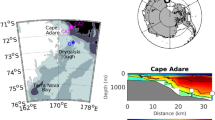

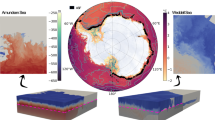

a 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model bathymetry of the western Ross Sea, based on the GEBCO product. Contours represent the 500 m and 1000 m isobaths. b Mean thickness of water with potential density σ1≥ 32.56 kg m−3 in the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model simulation, showing the location of the modeled dense water overflows in the Ross Sea and their pathways down the continental slope. c Standard deviation of ≤250 km scale, high-frequency SSH over 2 years of the PanAntarctic model simulation. The yellow contours denote the standard deviation of SSH from altimetry observations. Hatching represents areas with insufficient altimetry observations to compute a standard deviation (less than 15% of days with observations). d 10th percentile of the filtered SSH over 2 years in the PanAntarctic model simulation. The yellow contours are the 10th percentile of SSH from altimetry observations.

Surface signature of dense water overflows in the Ross Sea

The surface signature of the overflows is estimated using a MOM6-based, 0.05° resolution, ‘PanAntarctic’ regional ocean-sea ice model that realistically represents DSW formation and export from the Antarctic continental shelf to the abyss (see Methods). The model is forced with repeated year atmospheric forcing42. In the Ross Sea, DSW overflows are simulated along three troughs: the Drygalski, Joides and Glomar-Challenger troughs (Fig. 1a, b), consistent with observations43. Simulated DSW can be tracked leaving the continental shelf and descending the continental slope into the abyss, while being steered toward the west by the Coriolis force6.

Although the continental shelf acts as a dense water reservoir44, the simulated DSW transport immediately downstream of the shelf break is highly variable (Supplementary Fig. S1). This agrees with observations, which show localized, brief bursts of DSW crossing the shelf break once every few days at the trough location5,22,23. Such behavior results in localized, high-frequency SSH variability, which can be attributed to the steric signature of the dense water layer6,35 and the cyclonic eddies generated by vortex stretching in the water column above the dense plume38.

The standard deviation of the simulated filtered SSH fluctuations (see Methods) reveals a spatial pattern with the highest variability at the shelf break (Fig. 1c), reaching 2 cm of standard deviation, and diminishing downstream along pathways of overflowing DSW (Fig. 1a, b), as the dense water plumes widen and generate isobath-following cyclonic eddies38. The 10th percentile of simulated SSH at each grid point (Fig. 1d) shows that the distribution of low-SSH events coincides well with areas of high standard deviation. These patterns align with the steric height signature of DSW export pulses and the occurrence of cyclonic eddies, which are characterized by a depressed SSH. Overflow locations exhibit low-SSH events below -2.5 cm at least 10% of the time, compared to more modest SSH reductions of -1.6 to 0 cm in other areas.

The same metrics computed from 9 years of satellite altimetry data (yellow contours in Fig. 1c, d) match the simulated patterns. For the Joides and Glomar-Challenger overflows, the observed standard deviation of SSH and 10th percentile SSH values are higher than in the model, reaching up to 5 cm in standard deviation and -(6-8) cm in the 10th percentile. The stronger SSH variability in observations is likely due to the model’s incomplete representation of important dynamical processes, such as (sub-)mesoscale cyclonic eddies or topographic Rossby waves41,45. Due to the proximity of the Drygalski overflow to the coast, denser sea ice coverage diminishes the density of SSH observations. The spatial pattern represented in Fig. 1 is computed by aggregating all available observations in 25 km radii. In the Drygalski overflow region, days with observations represent less than 15% of the overall time series (see hatching in Fig. 1). In the next sections, for estimating temporal variability, the observations are aggregated within a region optimized to be localized at the overflow location area while being large enough to maximize the number of observations, making it possible to evaluate the Drygalski overflow temporal variability.

Monitoring long-term variability of Dense Shelf Water export

Both the model and observations demonstrate increased variability and occurrence of low-SSH events at the overflow sites (Fig. 1), which opens the possibility of using an SSH-based proxy to monitor DSW export variability from each trough. To test the utility of altimetry observations for this endeavor, we evaluate how the simulated DSW export from the Ross Sea overflow regions compares with an SSH-based proxy in a model. This longer-term analysis uses the 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2-01 model46 (see Methods), which provides an extended historical record of daily SSH and DSW export from the Ross Sea continental shelf. The analysis of a second model simulation with a coarser resolution than the PanAntarctic model is motivated by its interannually-varying forcing. ACCESS-OM2-01 accurately reproduces the formation of DSW on the continental shelf, and has been previously used to uncover the drivers of the interannual changes in Antarctic Bottom Water formation44.

Both Drygalski and Joides overflow sites exhibit similar interannual and longer-term variations in DSW export (Fig. 2, black lines), with enhanced transport during the 1980s relative to the pre-1975 period and early 2010s. The simulated DSW export variability is not expected to match the real historical variability, as the model does not include tides or changes in ice shelf meltwater. However, the simulation serves as a reference to assess the skill of a SSH-based proxy in detecting overflow variability.

Panels (a) and (b) respectively show time series for the Drygalski and Joides overflows. The black lines indicate the simulated annual DSW transport out of each overflow region in the 0.1° historical ACCESS-OM2-01 model. The red lines denote the SSH-based proxy (yearly 10th percentile of SSH) averaged in each overflow area from the same simulation, subsampled using the observational distribution of the three satellites available for 2017. Each overflow area and the 2017 observation coverage are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2). The blue lines show the observed SSH-based proxy (yearly 10th percentile) from the satellite data. Note that the observational proxy is scaled differently from the simulation-based proxy.

The performance of the SSH-based proxy is tested by subsampling the simulated SSH using the 2017 observation locations, which follow the tracks of three satellites (represented in Supplementary Fig. S2). Such subsampling is representative of the capacity of the current constellation of altimeters with data available in the ice-covered Southern Ocean29 (see Methods). Given the high-frequency variability of the overflows, we select the yearly 10th percentile of SSH as the proxy of annual DSW export. This choice of proxy is discussed in the next section. Several processes not fully represented in the models influence the surface signature of dense water overflows, and disentangling these mechanisms would require more idealized studies. Nevertheless, we expect a year with intensified DSW export to be associated with more pulses of overflowing DSW, pulses with thicker DSW layers, pulses with denser overflowing DSW, or a combination of the three. These scenarios are all associated with enhanced negative steric SSH, with the generation of more and stronger cyclonic eddies in the upper water column due to vortex stretching also expected to result in depressed SSH. Our SSH-based proxy (Fig. 2, red lines) captures most of the year-to-year and decadal-scale variations in simulated DSW export (Fig. 2, black lines). The proxy, calculated using simulated, subsampled SSH, correlates significantly (>99% significance) with the simulated DSW transport out of the overflow regions in the Drygalski (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.60, Fig. 2a) and Joides (r = 0.70, Fig. 2b) troughs. In contrast, the SSH-based proxy fails to reproduce the simulated variability in the Glomar-Challenger Trough (r = 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S3, not significant). When the SSH coverage is perfect (i.e. no subsampling), the correlations at the Drygalski and Joides overflows improve (r = 0.80, r = 0.88, respectively; Supplementary Fig. S4). At the Glomar challenger overflow, using the direct model SSH outputs (i.e. not subsampling) does not improve the correlation between simulated DSW transport and SSH proxy. The observation sampling is therefore not the main issue degrading the performance of the method for monitoring this overflow. Rather, the ACCESS-OM2-01 simulation representation of the Glomar-Challenger overflow seems to be the main issue, as the SSH variability is much weaker and DSW is thinner than in the higher resolution PanAntarctic simulation (Fig. 3).

Despite the model caveats, local maxima in DSW export simulated in 2016–2017 and 2020 (black lines in Fig. 2) are partially reflected in the observational proxy (blue lines). The variability of simulated and observed SSH proxies are similar in the Drygalski trough (r = 0.88), but not in the Joides or Glomar-Challenger. We do not explore this SSH relationship further: 9 years is too short for correlating with observations, and the model does not have ice shelf cavities nor interannual variability in meltwater, so it does not represent the ground truth. While the model serves as a test case on the method, we don’t expect the model to reproduce the true variability of dense water export. The yearly 10th percentile of SSH from satellite altimetry is computed from SSH data, presently available with two satellites from 2013 to mid-2016 and with three satellites from mid-2016 to 2021 (SARAL/AltiKa, Sentinel-3A, and Cryosat-2)29. The order of magnitude of the SSH proxy is higher than the estimated error of the SSH observation in ice-covered regions (3.7 cm, Auger et al. 2022). While there is uncertainty in the altimetry error in those regions, particularly due to sparse seafloor pressure observations it is hoped that SWOT will improve the accuracy of the observations. The positive trend in the time series of the observed SSH proxy in the three troughs suggests an intensification of the net DSW export from the Ross Sea continental shelf between the early 2010s and 2021.

In situ observations from hydrographic surveys and moorings on the Ross Sea continental shelf, specifically upstream the overflows in Terra Nova Bay and Ross Island show a salinity increase since 201424,25. While salinity on the shelf preconditions the overflow strength, other forcings such as the wind and tides can impact the year-to-year variability. Still, the salinity time series aligns well with the variability of the SSH proxy at the Drygalski overflow downstream (Supplementary Fig. S5). Changes in decadal tidal forcing also point toward an increase in DSW export23, meaning that both increased salinity and tidal forcing have resulted in intensified overflows at the shelf break and increased Antarctic Bottom Water formation after 201415,23, consistent with our findings. More direct observations of overflows include a historical multiyear velocity time series from moorings at the Drygalski shelf break, but it has a gap between 2011 and 201823. The remaining three-year matching period is too short for a comparison with the interannual variability of the SSH proxy. Future work may allow direct comparison with SWOT and longer-term mooring data. Our results also indicate that the observed proxy has a different variability for each trough, meaning that conventional in situ monitoring of a single trough only allows a partial view of the DSW export from the entire region.

Detectability of overflow events

The yearly 10th percentile of SSH captures the annual statistics of the varying intensity of the short low-SSH events that are dynamically associated with DSW overflows (Fig. 2). We now further investigate whether individual overflow events in the model can be detected from the simulated SSH, and give more insights into the choice of this percentile. The detectability of individual overflow events from SSH is evaluated at the Joides site (Fig. 4) in the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic simulation. Analogous analyses for the Drygalski and Glomar-Challenger troughs are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. In the shelf break areas with the highest SSH standard deviation (≥1.50 cm for Joides, Fig. 3c, red circle in Fig. 4a), potential temperature profiles averaged during low-SSH events ( < 10th percentile threshold of SSH) are found to be colder by more than one standard deviation in the deeper water column, compared with equivalent profiles averaged during higher-SSH periods (Fig. 4b). This provides evidence that low-SSH events are concurrent with the presence of especially cold waters – indicative of DSW – at depth.

a Same as Fig. 1a. The red circle shows the location of the Joides overflow area, defined as the area with a standard deviation of SSH ≥ 1.50 cm. The data shown in panels (b–d) are averaged over the area within the red circle. b Mean potential temperature profiles in the Joides overflow area, when SSH is lower than the 10th percentile over 4 years (blue), and for the 90% remaining times (red). The red shading indicates the standard deviation of the highest 90% of SSH. The depth of individual profiles has been normalized before averaging. c Time series of DSW thickness, defined by σ1 > 32.56 kg m−3 (gray line). The black line is the thickness threshold above which we define an overflow event, here 55 m, to which we add the 10-day running mean of the DSW thickness. d) ≤250km scale SSH anomaly in the Joides overflow area. The black line is the SSH threshold above which a possible overflow event is flagged, here the 11th percentile, to which we add the 10-day running mean of the SSH anomaly. The colored dots in (b) and (d) represent the performance of the detection approach, with green dots indicating successful detections, orange dots representing undetected overflow events, and black crosses denoting false detections.

This relationship is investigated further by comparing time series of area-mean SSH and DSW thickness, defined by the average thickness of the layer with σ1≥ 32.6 kg m−3 for the Joides and Drygalski troughs, σ1≥ 32.58 kg m−3 for the Glomar-Challenger trough. The DSW thickness at the overflow locations is shown here instead of the DSW transport due to computational constraints, but they are equivalent and show very similar variability (there is an r = 0.91 correlation between DSW thickness and transport when reproducing Fig. 2b). The Joides shelf break exhibits more frequent and intense overflow events between January and April (Fig. 4c). Most large-thickness (over 150 m) events are brief, lasting typically less than two days. The events appear as sudden increases in thickness followed by a return to the mean state, consistent with our knowledge of overflow processes5. SSH variability mirrors these patterns: the most prominent overflow events (with thickness ≥ 250 m) are linked to particularly reduced SSH, with average SSH anomalies of less than −4 cm that occasionally reach values below −5 cm (Fig. 4d). The simulated daily DSW thickness and SSH allow us to assess the detectability of individual overflow events using SSH data alone. To perform this test, we define a threshold for DSW thickness that indicates when an intense overflow event has occurred (black line in Fig. 4c). A corresponding threshold for a low-SSH event (black line in Fig. 4d) is adopted to gauge whether each overflow event could be successfully identified from SSH. The definition of these thresholds is detailed in the Methods. The best possible SSH threshold for the Joides, Drygalski, and Glomar-Challenger overflows corresponds to the 11th, 8th, and 11th percentiles, respectively. As we would like to take a common proxy and as it performs well for all the regions, the 10th percentile has been chosen as a proxy for the variability of DSW overflow in all the regions. The performance of the monitoring in Fig. 2 remains the same when using the 11th and 8th percentiles for the Joides and Drygalski overflows as when using the 10th percentile for both, with a correlation with simulated DSW export of r = 0.60 and r = 0.70 respectively.

The detection performance for each overflow event is represented by the colored dots in Fig. 4c, d: green dots indicate successful detections (large DSW thickness coinciding with low SSH); orange dots represent undetected overflow events (large DSW thickness, but negative SSH anomaly not sufficiently pronounced); and black crosses denote false detections (low SSH not corresponding with large DSW thickness). In the Joides region over four years, 62% of the most pronounced overflow events are detected using a simple low-SSH threshold. When this SSH threshold is reached, there is a 72% chance that an overflow event is happening. In the Drygalski and Glomar-Challenger sites, respectively, 78% and 53 % of the overflow events are detected, and an overflow occurs for 70% and 65% of the occasions in which the SSH threshold is attained (Supplementary Fig. S6). Although there is considerable uncertainty and a substantial number of overflow events go undetected, these results suggest that most overflow events are detectable in principle from their SSH signature alone, and that most of the low SSH events at these locations and scales are due to variability in the DSW layer thickness rather than layer variations of other water masses. Such an analysis is presently impossible using observations, due to the coarser spatial resolution of the data. At any rate, our model-based assessment of the detectability of overflow events demonstrates that our chosen SSH-based proxy (the yearly 10th percentile of the SSH) is physically justified for assessing the interannual variability of DSW export.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates the utility of satellite-observed SSH as a proxy for monitoring DSW export from the Antarctic continental shelf into the abyssal ocean – a climatically important phenomenon that has hitherto been unmeasurable over any expansive spatio-temporal domain. The statistics of overflow events, typically short-lived and characterized by reduced SSH at overflow locations, can be effectively captured using only SSH data. Both the spatial pattern (Fig. 1) and temporal variability of off-shelf DSW export (Figs. 2, 4) can be replicated from statistical metrics of SSH (standard deviation and yearly 10th percentile). Even when the limited observational distribution is accounted for, the SSH-based proxy remains skillful in reproducing interannual variations in DSW export (Fig. 2). Moreover, the observed SSH-based proxy (ranging from 4 to 8.5 cm, blue lines in Fig. 2) exceeds the altimetry error in the ice-covered regions of the Southern Ocean (estimated at 3.7 cm47). The observed SSH variability exceeds the simulated amplitude, likely due to unresolved smaller-scale processes in the models. Future high-resolution simulations could better capture overflow dynamics and enable the development of models for each of the troughs to estimate DSW transport from the SSH proxy, by drawing a relationship from the simulated transport and SSH and applying it to the altimetry observations. Similarly, improved in situ measurements within the satellite altimetry period would refine formulas for estimating overflow transport, extending their applicability to the full satellite altimetry record.

The applicability of our approach extends beyond the Ross Sea, with potential for monitoring DSW overflows in other Southern Ocean sectors. At the Weddell Sea continental shelf break, most DSW is exported via troughs and has a similar imprint on SSH as DSW in the Ross Sea6. Part of the western Weddell Sea is permanently sea ice-covered, and this results in satellite altimetry error being highest there47. However, this limitation does not affect some of the main DSW overflows in the Weddell region (e.g., the Filchner Trough), such that a substantial proportion of the DSW export from the Weddell Sea continental shelf is amenable to monitoring from space48. Together with the Ross sea, they export the major part of Antarctic Bottom Water. In the Adélie Land and Prydz Bay overflow areas, the narrowness of the shelf makes accurate satellite observations more challenging1,49, but remote monitoring may be possible through modest improvements in the processing of observational data. For those regions, the recently launched SWOT satellite50 will provide unprecedented spatial resolution, allowing a finer detection of the sea ice leads and better access to the coastal regions, and is expected to perform better than conventional altimetry. Conventional altimetry, however, remains the optimal data source to assess pre-2023 climatic variability in DSW overflows. Altimetric measurements exist from the 1990s that could be reprocessed for retrieval of SSH in ice-covered areas51, with data from multiple satellites having already been reprocessed in this manner for the 2010s and early 2020s52.

Our method investigates the variability of SSH, which reflects the variability of not only the DSW layer, but also the variability of the other water masses, such as the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), or the Antarctic Surface Water. While variability in those other layers could lead to false detections, our analysis shows that our proxy is statistically accurate to evaluate the interannual variability of the DSW layer (Fig. 2). Figure 4 shows that while some overflows are undetected or that there are false detections of overflows, the SSH predictor does a good job at estimating the number of overflows. The temperature profiles in Fig. 4b show this point further: The water column is significantly colder at depth when the SSH is low compared to average at the overflow location. Moreover, Morrison et al. (2020,6) show that at the shelf break, DSW variability is conjoined with CDW variability, which limits the risk of an independent CDW layer variability leading to false detections.

Our study underscores the potential of using satellite SSH as a proxy for monitoring DSW export from the Antarctic margins. This SSH proxy would complement the sparse and expensive existing in-situ observing system, and allow for a low carbon-emitting alternative to ship-based measurements. While acknowledging the current limitations in altimetry data and prospects for data quality and processing advances, our SSH-based proxy provides a novel and spatio-temporally wide-ranging approach to monitor the climatic evolution of DSW export. Developing the capability to detect changes in DSW transport presents an important and pressing challenge, at a time when the lower overturning cell may be undergoing a drastic slowdown16,17,19. To tackle this challenge, establishing a precise relationship between SSH variability and off-shelf DSW export through cross-comparison with in situ measurements or high-resolution models represents an exciting frontier for future research.

Methods

Datasets

SSH observations

The regional SSH product used in this paper is presented in detail in ref. 29, and is available on Aviso +. The gridded product consists of 9 years (2013–2021) of SSH anomalies and associated geostrophic current anomalies on a 25 km EASE2 grid53 every 3 days. Dataset validation and error estimation are described in29. Here, we focus on along-track satellite observations to capture the fine spatio-temporal variability associated with overflows in the Ross Sea. The level-3 dataset of along-track SSH anomalies for each satellite is available on the same time period on Aviso +. Both datasets are based on the processing and mapping of observations from three satellites: AltiKa54 and Sentinel-3A55 in the open and ice-covered oceans, and Cryosat-256 in the ice-covered regions.

Simulations

In this paper, we use two simulations to complement the satellite observations. The first one is the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model simulation, which is analyzed to evaluate the SSH signature of the overflows using high-resolution and high-frequency outputs. On the Ross Sea continental shelf, the resolution is about 2 km at the continental shelf break, which provides a good representation of mesoscale eddies57. This model is an ocean-sea ice coupled model driven by a prescribed atmosphere. The ocean model component is the Modular Ocean Model version 6 (MOM6) coupled to the NOAA-GFDL’s Sea Ice Simulator version 2 (SIS2)58. The model is forced at the surface by JRA-55-do Repeated Year Forcing, which cycles from May 1990 to April 199142. The PanAntarctic model is regional, with a single boundary at the northern edge at 37° S. It is forced at the open boundary by one repeated year of daily output from the 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2-01 simulation, which is forced by the same 1990-1991 JRA-55-do Repeated Year Forcing. The 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model vertical grid has z* vertical coordinates59 with partial cells60. The 75 levels are spaced from 1.1 m at the surface to 198 m at the bottom46.

The second simulation is the 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2-01 historical run, which simulates long-term changes in the transport of DSW overflowing from the Ross Sea region. This model allows us to evaluate the efficacy of the SSH-based proxy in monitoring interannual changes in DSW export using actual altimetry observations. ACCESS-OM2-01 is also an ocean-sea ice coupled model driven by prescribed JRA-55-do atmospheric forcing. The ocean model component is the Modular Ocean Model version 5.1 (MOM5.1), coupled to the Los Alamos sea-ice model version 5.1.2 (CICE5.1.2). The horizontal grid has a 0.1° resolution, which corresponds to about 4 km at the continental shelf break. It shares the same vertical grid as the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model. ACCESS-OM2-01 is described further in46.

Both simulations lack ice shelf cavities and tides. Tides are considered an important driver for the export of DSW from the Ross shelf to the bottom of the oceans22,23,61. However, this model limitation does not impact our results, which investigate the SSH response to overflowing DSW, rather than the precise causes of DSW overflows. The 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2 simulation, which has interannual variability driven by atmospheric forcing, has no temporal variability in ice shelf meltwater forcing, but still has a reasonable representation of DSW formation and export6,44,62. The 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model, which has no interannual variability in its forcing, exhibits DSW formation on the Antarctic continental shelf regions known to host such formation in reality (Supplementary Fig. S7). Supplementary Fig. S8 reproduces the diagnostic from Morrison et al. (2020)6 for the 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2 simulation, and shows the cumulative DSW transport across the continental shelf break (1000 m isobath) in the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic simulation. The DSW export rate and spatial distribution along the Antarctic shelf break are similar between the two model simulations.

The two simulations display some differences in the thickness of DSW formed in the Ross Sea, as well as in the SSH signature found at the overflow locations (Fig. 3). Overall, the bottom layer of the ocean in the 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic model simulation is denser than in the 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2-01 historical run, resulting in larger DSW thickness on most of the shelf, at the overflow locations and downstream on the slope, especially at the Joides and Glomar-Challenger overflow areas. In particular, DSW thickness is very close to zero at the Glomar-Challenger location for the ACCESS-OM2-01 historical run, which translates into a weak SSH signature at this same location (Fig. 3d), in contrast to the strong SSH signature at the Glomar-Challenger overflow in the PanAntarctic model simulation (Fig. 3c). This difference could explain the poor performance of the SSH-based proxy for monitoring the DSW export from the Glomar-Challenger trough using the ACCESS-OM2 historical run in Fig. 2.

SSH processing and filtering

In order to isolate the imprint of DSW overflows on SSH, we filter out large-scale and low-frequency SSH variations. Large-scale SSH variability primarily reflects the dynamics of the Antarctic Slope Current29,32 and the Ross Gyre31. In the simulations and observations, large-scale variations are eliminated by subtracting the average SSH within a 250 km radius around each grid point. This radius was determined to be the most effective based on our evaluation of 170, 250, and 330 km radii (detailed in the Methods section under ‘Individual Overflow Detection’). Reproducing the time series of Fig. 2 with the 170 km radius leads to correlations between overflow transport and SSH proxy of r = 0.49, r = 0.74, and r = 0.02 for the Drygalski, Joides, and Glomar-Challenger overflows, respectively. With the 330 km radius, these correlations are r = 0.60, r = 0.65, and r = −0.08. Both filters show correlations with more than 99% significance for the Drygalski and Joides troughs. For Fig. 1 and 4, we apply a 10-day running mean filter to remove low-frequency fluctuations. When this running mean is not removed for Fig. 4 thresholds, 58% of overflows are detected, and an overflow occurs for 77% of the times in which the SSH threshold is reached. When it is removed (as in the Fig. 4 example) 62% overflow are detected, with overflows occurring 72% of the times this threshold is reached. This shows that results are consistent even without the running mean, suggesting that large-scale removal also effectively mitigates much of the low-frequency variability.

The along-track observations are gridded and filtered to generate the contours in Fig. 1c, d. Within the area of interest, we use a 0.5°-resolution grid. We aggregate and average daily all observations within a 25 km radius of each grid point. Large-scale SSH is filtered using the L4 gridded dataset29 by subtracting the mean SSH within a 250 km radius.

Time series of simulated SSH at overflow locations (Fig. 2,4) are calculated by averaging grid points in the high-variability patches, when SSH is not subsampled. When SSH is subsampled or when direcly using the along-track observations (Fig. 2), daily averages of along-track data falling within the overflow regions are taken. Here too, we remove large-scale variability by subtracting the mean from the gridded datasets within 250 km radii around the patches.

Impact of observational sampling

The observational dataset used in this study consists of measurements from two satellites between 2013 and mid-2016, and from three satellites between mid-2016 and the end of 2021. The impact of the observational sampling on the performance of our SSH-based proxy is assessed by subsampling the simulated SSH using the 2017 observational distribution, which consists of a three-satellite configuration. The sensitivity of our SSH-based proxy to the transition from two to three satellites in mid-2016 is probed by examining the number of days with observations in each year for each overflow site (Supplementary Fig. S9). Figure 2 (red lines) uses the denser spatio-temporal distribution of the 2017 observations to subsample the simulated SSH. In 2017, the three satellites provided 82 and 91 days with observations in the Drygalski and Joides troughs, respectively. Removing one of the satellites when subsampling the model shows that the simulated SSH-based proxy performs similarly with either two or three satellites (Supplementary Fig. S10), such that the variability in the observed SSH-based proxy (blue lines in Fig. 2) is only weakly affected by the change in observing system.

On the other hand, the limited observational availability has an impact on the performance of the SSH-based proxy. Without this subsampling, the correlations are higher and have ≥ 99% significance, with r = 0.80 in the Drygaski Trough, r = 0.88 in the Joides Trough (Supplementary Fig. S4), showing that well-resolved SSH has an even better performance for the detection and monitoring of DSW export.

Individual overflow detection

The effectiveness of using SSH to identify specific simulated overflow events is assessed in Fig. 4. We focus on areas with a high standard deviation of SSH (≥1.31 cm for Drygalski overflow, ≥1.50 cm for Joides overflow, and ≥1.48 cm for Glomar-Challenger overflow), which are located at overflow regions at the shelf break (Fig. 1). These standard deviation values were found to be the best performing thresholds. A standard deviation too high leads to an overflow area too small, which won’t be sampled enough. On the opposite, a standard deviation too low leads to an overflow area too large, meaning that observations sampled in non-meaningful areas for that overflow will weight in the statistics. The choice of the areas has been systematically evaluated over many iterations, as shown for the Joides overflow example in Supplementary Fig. S11. After computing the time series of mean dense water thickness and mean SSH anomaly in each overflow region, this evaluation requires establishing two thresholds. The first threshold is the minimum DSW layer thickness necessary to classify an event as an overflow. The second threshold is the SSH value below which the overflow event is considered detected, which is computed as a percentile of the SSH variability. These thresholds are interdependent: lower DSW thickness thresholds improve detection sensitivity when SSH thresholds are near zero, allowing for more detections. Conversely, higher thickness thresholds limit detection to larger overflows, necessitating lowered SSH thresholds. Their definition is therefore based on a threshold-pair optimization through a scoring system. In Fig. 4, detection outcomes are color-coded: green for correct detections, orange for undetected overflow events, and black for false detections. The optimization goal is to maximize the number of green dots (correct detections) while minimizing the number of orange (missed events) and black (false positives) dots. The detection score is calculated as: \(score=\frac{No.(\,green)}{(No.(black)+No.(orange/2))}\). This emphasizes accurate detections and minimizes false detections. The thresholds are a combination of a fixed optimized value to which we add the time-dependent 10-day running mean. SSH and DSW thickness threshold pairs are tested by tuning the fixed part of the threshold to find the best possible pair of thresholds, leading to the highest detection score. An example of this optimization for the Joides overflow is shown in Supplementary Fig. S12. In this example, the optimization leads to best thresholds of 55 m of DSW thickness and a SSH anomaly corresponding to the 11th percentile of SSH. 10-day running means are added to these values to obtain the final threshold values.

In the Joides example (Fig. 4), we focus on the detection of pronounced overflow events. Focusing on larger overflow events is more relevant for observations, as these prominent events have SSH signatures exceeding the measurement error of the current satellite altimeters. However, more permissive thresholds, such as those chosen for the Drygalski or Glomar-Challenger troughs (Supplementary Fig. S6, ≥60 m DSW thickness and ≤13th SSH percentile for the Drygalski overflow, ≥30 m DSW thickness and ≤11th SSH percentile for the Glomar-Challenger overflow, to which we add the 10-days running means) have a similar performance in the simulation.

Adding a bathymetry criterion to the overflow region definition can also improve detection scores. Supplementary Fig. S13 illustrates the relationship between water column height and SSH detectability for each gridpoint in the Joides overflow region, displaying the optimal DSW thickness threshold for scoring and the best detection scores relative to bathymetry. Notably, higher scores are associated with larger water columns. Further analysis indicates that smaller water columns typically experience more frequent but less sizable overflows, leading to a weaker SSH response that is challenging to detect. In the Joides region, we focus on overflows at gridpoints in which water depth exceeds 700 m, as these areas tend to have larger overflows with clearer SSH signals. A similar approach in the Drygalski and Glomar-Challenger troughs yields comparable results, reinforcing the effectiveness of this method for gridpoints with water column heights greater than 700 and 650 m respectively in those regions. Analyzing the geographical distribution of this score also enables us to identify zones where the detection is particularly difficult. Specifically, an especially low score (≤0.8) was found in the southern part of the Drygalski region with high-SSH variability. Omitting the latitudes to the south of -72.1°S removes these low score points, as well as improves the performances of the monitoring of DSW export.

Data availability

Processed 0.05°-resolution PanAntarctic outputs used for the analyses of this paper are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15012743. 0.1°-resolution ACCESS-OM2 IAF model outputs are available in the COSIMA data collection, at https://doi.org/10.4225/41/5a2dc8543105a. The gridded SSH dataset and the along-track measurements obtained in the sea ice area are available on Aviso + from https://doi.org/10.24400/527896/a01-2022.010. Along-track measurements in the open ocean are obtained from the CMEMS portal https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L3_MY_008_062.

Code availability

The github repositories for the model configurations are available at https://github.com/COSIMA/mom6-panan/tree/panan-005and https://github.com/COSIMA/01deg_jra55_iaf. Analysis code is available at https://github.com/MatthisAuger/DSW_Overflows_Space.git.

Change history

03 December 2025

In this article the funding from ‘European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative funding (TipSOO project)’ was omitted. The article has been updated.

References

Williams, G. D. et al. Antarctic Bottom Water from the Adélie and George V Land coast, East Antarctica (140-149°E). J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 115 (2010).

Ohshima, K. I. et al. Antarctic Bottom Water production by intense sea-ice formation in the Cape Darnley polynya. Nat. Geosci. 6, 235–240 (2013).

Bergamasco, A., Defendi, V., Zambianchi, E. & Spezie, G. Evidence of dense water overflow on the Ross Sea shelf-break. Antarct. Sci. 14, 271–277 (2002).

Foldvik, A. et al. Ice shelf water overflow and bottom water formation in the southern Weddell Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 109 (2004).

Darelius, E., Smedsrud, L., Østerhus, S., Foldvik, A. & Gammelsrød, T. Structure and variability of the Filchner overflow plume. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 61, 446–464 (2009).

Morrison, A. K., Hogg, A. M., England, M. H. & Spence, P. Warm circumpolar deep water transport toward Antarctica driven by local dense water export in canyons. Sci. Adv. 6, eaav2516 (2020).

Gordon, A. L. et al. Western Ross Sea continental slope gravity currents. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 796–817 (2009).

Pellichero, V., Sallée, J.-B., Schmidtko, S., Roquet, F. & Charrassin, J.-B. The ocean mixed layer under Southern Ocean sea-ice: Seasonal cycle and forcing. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 122, 1608–1633 (2017).

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in anthropogenic carbon and heat uptake in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Xie, Y. et al. Euphotic zone residence time of Antarctic Bottom Water. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106342 (2024).

Jacobs, S. S. & Giulivi, C. F. Large multidecadal salinity trends near the Pacific-Antarctic continental margin. J. Clim. 23, 4508–4524 (2010).

Purkey, S. G. & Johnson, G. C. Global contraction of Antarctic Bottom Water between the 1980s and 2000s. J. Clim. 25, 5830–5844 (2012).

Snow, K., Hogg, A. M., Sloyan, B. M. & Downes, S. M. Sensitivity of Antarctic Bottom Water to changes in surface buoyancy fluxes. J. Clim. 29, 313–330 (2016).

Aoki, S. et al. Warm surface waters increase Antarctic ice shelf melt and delay dense water formation. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1–8 (2022).

Silvano, A. et al. Recent recovery of Antarctic Bottom Water formation in the Ross Sea driven by climate anomalies. Nat. Geosci. 13, 780–786 (2020).

Gunn, K. L., Rintoul, S. R., England, M. H. & Bowen, M. M. Recent reduced abyssal overturning and ventilation in the Australian Antarctic Basin. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 537–544 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. Slowdown of Antarctic Bottom Water export driven by climatic wind and sea-ice changes. Nat. Clim. Change 1–9 (2023).

Silvano, A. et al. Observing Antarctic Bottom Water in the Southern Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 10 (2023).

Li, Q., England, M. H., Hogg, A. M., Rintoul, S. R. & Morrison, A. K. Abyssal ocean overturning slowdown and warming driven by Antarctic meltwater. Nature 615, 841–847 (2023).

Abrahamsen, E. P. et al. Stabilization of dense Antarctic water supply to the Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 742–746 (2019).

Spingys, C. P. et al. Mixing and transformation in a deep western boundary current: a case study. J. Phys. Oceanogr. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/phoc/51/4/JPO-D-20-0132.1.xml (2021).

Bowen, M. M. et al. The role of tides in bottom water export from the western Ross Sea. Sci. Rep. 11, 2246 (2021).

Bowen, M. M. et al. Tides regulate the flow and density of Antarctic Bottom Water from the western Ross Sea. Sci. Rep. 13, 3873 (2023).

Castagno, P. et al. Rebound of shelf water salinity in the Ross Sea. Nat. Commun. 10, 5441 (2019).

Jacobs, S. S., Giulivi, C. F. & Dutrieux, P. Persistent Ross Sea freshening from imbalance West Antarctic Ice Shelf Melting. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2021JC017808 (2022).

McMahon, C. R. et al. Animal Borne Ocean Sensors—AniBOS—An essential component of the global ocean observing system. Front. Mar. Sci. 8 (2021).

Meredith, M. P., Jullion, L., Brown, P. J., Naveira Garabato, A. C. & Couldrey, M. P. Dense waters of the Weddell and Scotia Seas: recent changes in properties and circulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 372, 20130041 (2014).

Akhoudas, C. et al. Ice Shelf Basal Melt and influence on dense water outflow in the Southern Weddell Sea. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 125, e2019JC015710 (2020).

Auger, M., Prandi, P. & Sallée, J.-B. Southern ocean sea level anomaly in the sea ice-covered sector from multimission satellite observations. Sci. Data 9, 70 (2022).

Armitage, T. W. K., Kwok, R., Thompson, A. F. & Cunningham, G. Dynamic topography and sea level anomalies of the Southern Ocean: variability and teleconnections. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 123, 613–630 (2018).

Dotto, T. S. et al. Variability of the Ross Gyre, Southern Ocean: drivers and responses revealed by satellite altimetry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 6195–6204 (2018).

Garabato, A. C. N. et al. Phased response of the subpolar Southern Ocean to changes in circumpolar winds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6024–6033 (2019).

Quartly, G. D. et al. Retrieving sea level and freeboard in the Arctic: a review of current radar altimetry methodologies and future perspectives. Remote Sens. 11, 881 (2019).

Auger, M., Sallée, J.-B., Thompson, A. F., Pauthenet, E. & Prandi, P. Southern ocean ice-covered eddy properties from satellite altimetry. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 128, e2022JC019363 (2023).

Høyer, J. L. & Quadfasel, D. Detection of deep overflows with satellite altimetry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 1611–1614 (2001).

Lea, D. J., Haine, T. W. N. & Gasparovic, R. F. Observability of the Irminger Sea circulation using variational data assimilation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 132, 1545–1576 (2006).

Haine, T. W. N. High-frequency fluctuations in Denmark Strait transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (2010).

Jiang, L. & Garwood, R. W. Three-dimensional simulations of overflows on continental slopes. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 26, 1214–1233 (1996).

Krauss, W. & Käse, R. H. Eddy formation in the Denmark Strait overflow. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 103, 15525–15538 (1998).

von Appen, W.-J., Pickart, R. S., Brink, K. H. & Haine, T. W. N. Water column structure and statistics of Denmark Strait Overflow Water cyclones. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 84, 110–126 (2014).

Han, X. et al. Topographic Rossby wave-modulated oscillations of dense overflows. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2022JC018702 (2022).

Stewart, K. D. et al. JRA55-do-based repeat year forcing datasets for driving ocean-sea-ice models. Ocean Model. 147, 101557 (2020).

Orsi, A. H. & Wiederwohl, C. L. A recount of Ross Sea waters. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 778–795 (2009).

Schmidt, C., Morrison, A. K. & England, M. H. Wind- and sea-ice-driven interannual variability of Antarctic Bottom Water formation. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 128, e2023JC019774 (2023).

Han, X., Stewart, A. L., Chen, D., Liu, X. & Lian, T. Controls of topographic Rossby wave properties and downslope transport in dense overflows. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 53, 1805–1820 (2023).

Kiss, A. E. et al. ACCESS-OM2 v1.0: a global ocean-sea ice model at three resolutions. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 401–442 (2020).

Auger, M., Sallée, J.-B., Prandi, P. & Naveira Garabato, A. C. Subpolar southern ocean seasonal variability of the geostrophic circulation from multi-mission satellite altimetry. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 127, e2021JC018096 (2022).

Nissen, C., Timmermann, R., van Caspel, M. & Wekerle, C. Altered Weddell Sea warm- and dense-water pathways in response to 21st-century climate change. Ocean Sci. 20, 85–101 (2024).

Williams, G. D., Bindoff, N. L., Marsland, S. J. & Rintoul, S. R. Formation and export of dense shelf water from the Adélie Depression, East Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 113 (2008).

Morrow, R. et al. Global observations of fine-scale ocean surface topography with the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) Mission. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 232 (2019).

Dragomir, O. Dynamics of the subpolar Southern Ocean response to climate change. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/492038/ (2024).

Auger, M., Prandi, P. & Sallée, J.-B. Daily southern ocean sea level anomaly and geostrophic currents from multimission altimetry, 2013-2019. https://doi.org/10.17882/81032 (2021).

Brodzik, M. J. et al. EASE-Grid 2.0: incremental but significant improvements for earth-gridded data sets. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2012, 1, 32-45. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 3, 1154–1156 (2014).

Verron, J. et al. The SARAL/AltiKa Altimetry Satellite Mission. Mar. Geod. 38, 2–21 (2015).

S. Dinardo, B. Lucas and J. Benveniste, “Sentinel-3 STM SAR ocean retracking algorithm and SAMOSA model,” 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 2015, pp. 5320-5323, https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS.2015.7327036.

Wingham, D. J. et al. CryoSat: a mission to determine the fluctuations in Earth’s land and marine ice fields. Adv. Space Res. 37, 841–871 (2006).

Stewart, A. L. & Thompson, A. F. Eddy-mediated transport of warm Circumpolar Deep Water across the Antarctic Shelf Break. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 432–440 (2015).

Adcroft, A. et al. The GFDL Global Ocean and Sea Ice Model OM4.0: model description and simulation features. J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 11, 3167–3211 (2019).

Adcroft, A. & Campin, J.-M. Rescaled height coordinates for accurate representation of free-surface flows in ocean circulation models. Ocean Model. 7, 269–284 (2004).

Pacanowski, R. C. & Gnanadesikan, A. transient response in a Z-Level Ocean Model that resolves topography with partial cells. Mon. Weather Rev. 126, 3248–3270 (1998).

Padman, L., Howard, S. L., Orsi, A. H. & Muench, R. D. Tides of the northwestern Ross Sea and their impact on dense outflows of Antarctic Bottom Water. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 818–834 (2009).

Moorman, R., Morrison, A. K. & Hogg, A. M. Thermal responses to Antarctic Ice Shelf melt in an Eddy-rich global ocean-sea ice model. J. Clim. 33, 6599–6620 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Projects DP190100494 and DP250100759, and by the ARC Special Research Initiative, Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (SR200100008). The research was undertaken with the assistance of resources and services from the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian Government. The authors thank the Consortium for Ocean-Sea Ice Modeling in Australia (COSIMA; http://www.cosima.org.au) for making the ACCESS-OM2 and PanAntarctic model configurations available. We also acknowledge the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator National Research Infrastructure (ACCESS-NRI), funded by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy, for their maintenance of virtual environments, code and model support. P.S. is supported by Australian Research Council grants FT190100413, CE230100012, DP240102358, LP200100406. Thanks to Kathy Gunn for comments on an early manuscript version. AS and ACNG were supported by the European Space Agency (ESA) as part of the ESA CLIMATE-SPACE Tipping Elements Activity via the Tipping Point of the Southern Ocean Overturning (TIPSOO) project – climate.esa.int (ESA Contract No. 4000146528/24/I-LR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. conducted the analyses, prepared the figures and wrote the initial manuscript with contributions from P.S. and A.M.; M.A., P.S., A.M., A.N.G., and A.S. discussed the results and implications, and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Viviane Menezes and Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Auger, M., Spence, P., Morrison, A.K. et al. The variability of Antarctic dense water overflows can be observed from space. Commun Earth Environ 6, 286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02210-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02210-7

This article is cited by

-

Antarctic Bottom Water in a changing climate

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)